Submitted:

04 September 2025

Posted:

05 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

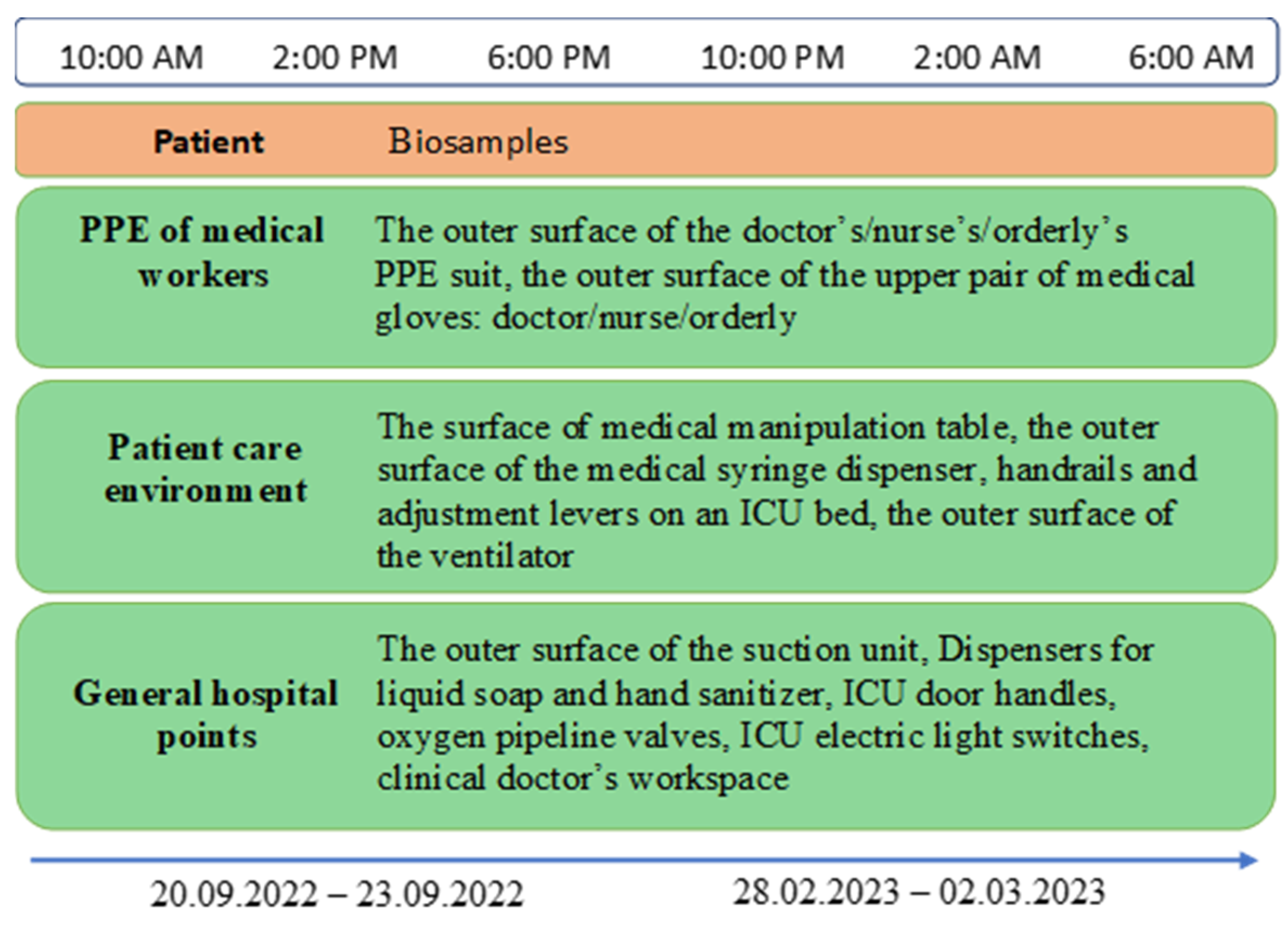

2.1. Sampling and Bacterial Isolation

2.2. DNA Extraction and Whole-Genome Sequencing

2.3. Bioinformatic Analysis

3. Results

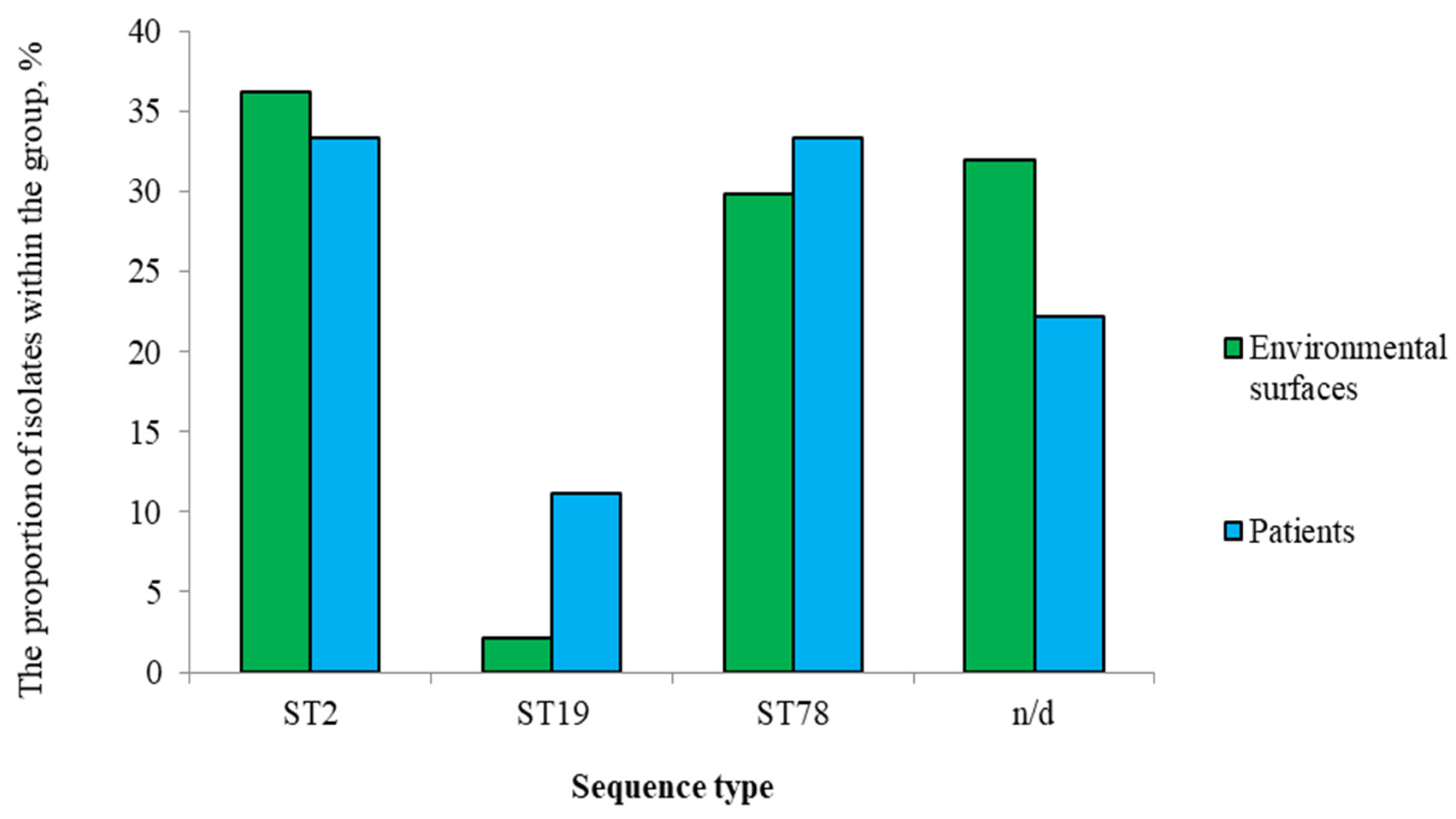

3.1. Isolate Collection and Sequence Types

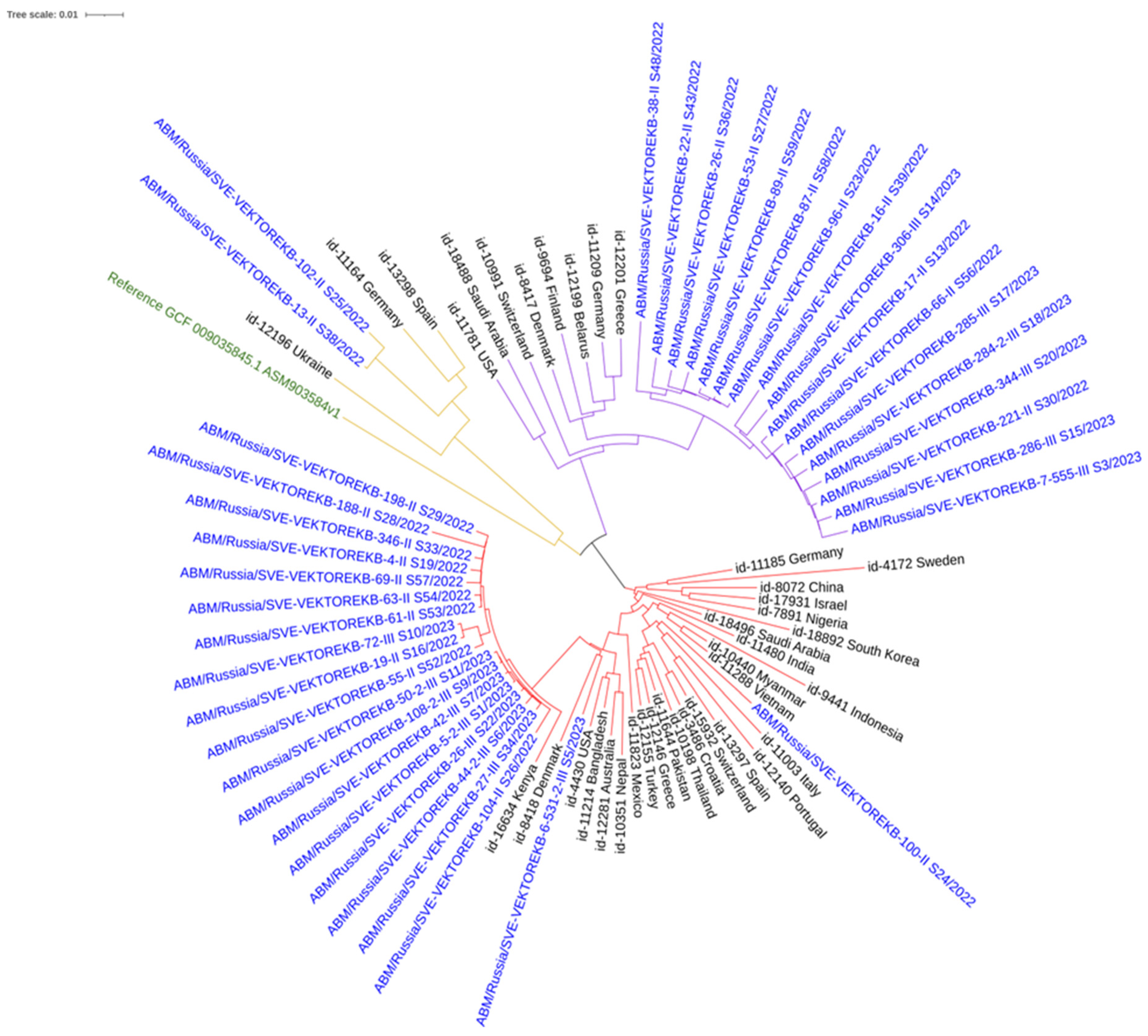

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

3.3. Antimicrobial Resistance Determinants

- ST2: Characteristic profile: armA, aph(6)-Id, aph(3')-Ia, aph(3'')-Ib, blaOXA-23, msr(E), mph(E). The blaOXA-23 carbapenemase was present in 100% of isolates.

- ST78: Characteristic profile: armA, blaOXA-72, blaOXA-90, msr(E), mph(E). blaOXA-23 was absent.

- ST19: Profile included aph(3')-VIa, blaOXA-69, blaADC-25, catA1, sul2, tet(B).

3.4. Microevolution and SNP Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| CRAB | Carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii |

| cgMLST | Core-genome MLST |

| ICUs | Intensive care units |

| HAIs | Healthcare-associated infections |

| OP | Opportunistic pathogen |

| MLST | Multi-locus sequence typing |

| PPE | Personal protective equipment |

| ST | Sequence type |

| WGS | Whole-genome sequencing |

| PCE | Patient care environment |

| GHP | General hospital point |

| AMI | Aminoglicoside |

| BL | Beta-lactam |

| MKL | Macrolide |

| SGB | Streptogramin b |

| AP | Amphenicol |

| RF | Rifamycin |

| AF | Antifolates |

| TET | Tetracycline |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Sample ID | Selection group | Selection point |

| 5-2-III_S1 | PPE | The outer surface of the upper pair of medical gloves (orderly) |

| 6-2-III_S35 | PPE | The outer surface of the orderly’s PPE suit |

| 7-II_S40 | PCE | The surface of medical manipulation table |

| 13-2-II_S41 | PCE | The outer surface of the medical syringe dispenser |

| 21-II_S42 | PPE | The outer surface of the upper pair of medical gloves (doctor) |

| 22-II_S43 | PPE | The outer surface of the upper pair of medical gloves (nurse) |

| 25-II_S45 | PPE | The outer surface of the orderly’s PPE suit |

| 26-II_S36 | PPE | The outer surface of the doctor’s PPE suit |

| 26-III_S22 | PPE | The outer surface of the orderly’s PPE suit |

| 27-III_S34 | PCE | The surface of medical manipulation table |

| 28-II_S46 | PCE | Handrails and adjustment levers on an ICU bed |

| 33-II_S47 | PCE | The outer surface of the medical syringe dispenser |

| 38-II_S48 | GHP | ICU door handles |

| 42-III_S7 | PPE | The outer surface of the doctor’s PPE suit |

| 44-2-III_S6 | PPE | The outer surface of the nurse’s PPE suit |

| 48-2-III_S4 | PCE | Handrails and adjustment levers on an ICU bed |

| 48-II_S49 | PCE | The surface of medical manipulation table |

| 49-II_S50 | PCE | Handrails and adjustment levers on an ICU bed |

| 50-2-III_S11 | PCE | The outer surface of the ventilator |

| 51-II_S51 | PCE | The outer surface of the ventilator |

| 53-II_S27 | PCE | Handrails and adjustment levers on an ICU bed |

| 55-II_S52 | PCE | The outer surface of the ventilator |

| 61-II_S53 | PPE | The outer surface of the upper pair of medical gloves (orderly) |

| 63-II_S54 | PPE | The outer surface of the upper pair of medical gloves (nurse) |

| 64-II_S55 | PPE | The outer surface of the nurse’s PPE suit |

| 66-II_S56 | PPE | The outer surface of the doctor’s PPE suit |

| 69-II_S57 | PCE | Handrails and adjustment levers on an ICU bed |

| 72-III_S10 | PCE | Handrails and adjustment levers on an ICU bed |

| 87-II_S58 | PCE | The surface of medical manipulation table |

| 89-II_S59 | PCE | Handrails and adjustment levers on an ICU bed |

| 96-II_S23 | GHP | The outer surface of the suction unit |

| 100-II_S24 | GHP | Dispensers for liquid soap and hand sanitizer |

| 102-II_S25 | PPE | The outer surface of the nurse’s PPE suit |

| 104-II_S26 | PPE | The outer surface of the orderly’s PPE suit |

| 108-2-III_S9 | PCE | Handrails and adjustment levers on an ICU bed |

| 188-II_S28 | PCE | Handrails and adjustment levers on an ICU bed |

| 198-II_S29 | GHP | ICU door handles |

| 221-II_S30 | PPE | The outer surface of the upper pair of medical gloves (doctor) |

| 284-2-III_S18 | PPE | The outer surface of the nurse’s PPE suit |

| 285-III_S17 | PPE | The outer surface of the upper pair of medical gloves (orderly) |

| 286-III_S15 | PPE | The outer surface of the orderly’s PPE suit |

| 306-III_S14 | PPE | The outer surface of the orderly’s PPE suit |

| 307-1-II_S32 | PCE | The surface of medical manipulation table |

| 331-II_S12 | PCE | The surface of medical manipulation table |

| 344-III_S20 | PPE | The outer surface of the nurse’s PPE suit |

| 346-II_S33 | PPE | The outer surface of the orderly’s PPE suit |

| 224-2_S15 | PPE | The outer surface of the doctor’s PPE suit |

| Notes: PPE – personal protective equipment, PCE – patient care environment, GHP – general hospital point. | ||

Appendix A.2

| Genetic determinants profiles of resistance of patient’s A. baumannii isolates | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sample ID | MLST | AMI | BL | MKL | SGB | AP | RF | AF | TET | |||||||||||||||||||

| armA | aph(6)-Id (strB) | aph(3')-Ia | aph(3')-VIa | aph(3'')-Ib | aph(3')-VIb | aadA1 | aac(6')-lb3 | blaOXA-23 | blaADC-25 | blaPER-7 | blaOXA-66 | blaCTX-M-124 | blaOXA-72 | blaOXA-90 | blaTEM-1D | blaCARB-14 | msr(E) | mph(E) | catB8 | cmlA1 | floR | catA1 | ARR-2 | sul1 | sul2 | tet(B) | ||

| 2-II_S37 | n/d | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 4-II_S19 | ST2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6-531-2-III_S5 | ST2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 7-555-III_S3 | ST78 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 13-II_S38 | ST19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 14-II_S21 | n/d | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 16-II_S39 | ST78 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 17-II_S13 | ST78 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 19-II_S16 | ST2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Notes: AMI – aminoglicoside; BL – beta-lactam; MKL – macrolide; SGB – streptogramin b; AP – amphenicol; RF – rifamycin; AF – antifolates; TET – tetracycline; 1 – is available; 0 – absent. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Appendix A.3

| Genetic determinants profiles of resistance of environmental objects’ A. baumannii isolates | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sample ID | MLST | AMI | BL | MKL | SGB | AP | RF | AF | TET | |||||||||||||||||||

| armA | aph(6)-Id (strB) | aph(3')-Ia | aph(3')-VIa | aph(3'')-Ib | aph(3')-Vib | aadA1 | aac(6')-lb3 | blaOXA-23 | blaADC-25 | blaPER-7 | blaOXA-66 | blaCTX-M-124 | blaOXA-72 | blaOXA-90 | blaTEM-1D | blaCARB-14 | msr(E) | mph(E) | catB8 | cmlA1 | floR | catA1 | ARR-2 | sul1 | sul2 | tet(B) | ||

| 5-2-III_S1 | ST2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 6-2-III_S35 | n/d | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 7-II_S40 | n/d | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 13-2-II_S41 | n/d | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 21-II_S42 | n/d | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 22-II_S43 | ST78 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 25-II_S45 | n/d | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 26-II_S36 | ST78 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 26-III_S22 | ST2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 27-III_S34 | ST2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 28-II_S46 | n/d | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 33-II_S47 | n/d | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 38-II_S48 | ST78 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 42-III_S7 | ST2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 44-2-III_S6 | ST2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 48-2-III_S4 | n/d | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 48-II_S49 | n/d | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 49-II_S50 | n/d | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 50-2-III_S11 | ST2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 51-II_S51 | n/d | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 53-II_S27 | ST78 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 55-II_S52 | ST2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 61-II_S53 | ST2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 63-II_S54 | ST2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 64-II_S55 | n/d | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 66-II_S56 | ST78 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 69-II_S57 | ST2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 72-III_S10 | ST2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 87-II_S58 | ST78 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 89-II_S59 | ST78 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 96-II_S23 | ST78 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 100-II_S24 | ST2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 102-II_S25 | ST19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 104-II_S26 | ST2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 108-2-III_S9 | ST2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 188-II_S28 | ST2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 198-II_S29 | ST2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 221-II_S30 | ST78 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 284-2-III_S18 | ST78 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 285-III_S17 | ST78 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 286-III_S15 | ST78 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 306-III_S14 | ST78 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 307-1-II_S32 | n/d | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 331-II_S12 | n/d | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 344-III_S20 | ST78 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 346-II_S33 | ST2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 224-2_S15 | n/d | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Notes: AMI – aminoglicoside; BL – beta-lactam; MKL – macrolide; SGB – streptogramin b; AP – amphenicol; RF – rifamycin; AF – antifolates; TET – tetracycline; 1 – is available; 0 – absent. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Ivanov, F.V.; Gumilyevsky, B.Y. Microbiological Monitoring of Healthcare-Associated Infections. Mezhdunarodnyj Nauchno-Issledovatel'skij Zhurnal 2023, *138*, 210. (In Russian). [CrossRef]

- Kutyrev, V.V.; Popova, A.Y.; Smolensky, V.Y.; et al. Epidemiological Features of the New Coronavirus Infection (COVID-19). Message 2. Probl Osobo Opasnykh Infektsii 2020, *2*, 6–12. (In Russian) . [CrossRef]

- Brusina, E.B.; Zueva, L.P.; Kovalishena, O.V.; et al. Infections Related To Medical Care: A Modern Prevention Doctrine. Epidemiol Vakcinoprofilaktika 2018, *17*, 4–10. (In Russian) . [CrossRef]

- O'Toole, R.F. The Interface Between COVID-19 and Bacterial Healthcare-Associated Infections. Clin Microbiol Infect 2021, *27*, 1772–1776. [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, M.M.; Srinivasa, V.R.; Griffith, M.P.; et al. Genomic Diversity of Hospital-Acquired Infections Revealed through Prospective Whole-Genome Sequencing-Based Surveillance. mSystems 2022, *7*, e0138421. [CrossRef]

- Larsson, D.G.J.; Flach, C.F. Antibiotic Resistance in the Environment. Nat Rev Microbiol 2022, *20*, 257–269. [CrossRef]

- Weimann, A.; Dinan, A.M.; Ruis, C.; et al. Evolution and Host-Specific Adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Science 2024, *385*, eadi0908. [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Wang, K.; Liu, Y.; et al. Population Dynamics of an Acinetobacter baumannii Clonal Complex during Colonization of Patients. J Clin Microbiol 2014, *52*, 3200–3208. [CrossRef]

- Roca, I.; Espinal, P.; Vila-Farrés, X.; Vila, J. The Acinetobacter baumannii Oxymoron: Commensal Hospital Dweller Turned Pan-Drug-Resistant Menace. Front Microbiol 2012, *3*, 148. [CrossRef]

- Antunes, L.C.; Visca, P.; Towner, K.J. Acinetobacter baumannii: Evolution of a Global Pathogen. Pathog Dis 2014, *71*, 292–301. [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Mutakabbir, J.C.; Griffith, N.C.; Shields, R.K.; et al. Contemporary Perspective on the Treatment of Acinetobacter baumannii Infections: Insights from the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Infect Dis Ther 2021, *10*, 2177–2202. [CrossRef]

- Boral, J.; Genç, Z.; Pınarlık, F.; et al. The Association Between Acinetobacter baumannii Infections and the COVID-19 Pandemic in an Intensive Care Unit. Sci Rep 2022, *12*, 20808. [CrossRef]

- Noskov, A.K.; Popova, A.Y.; Vodopyanov, A.S.; et al. Molecular Genetic Analysis of Bacterial Pneumonia Pathogens Associated with COVID-19 in Rostov-on-Don Hospitals. Zdorov'e Naselenija i Sreda Obitanija 2021, *29*, 64–71. (In Russian) . [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J.; et al. Bioaerosols in the Earth System: Climate, Health, and Ecosystem Interactions. Atmospheric Res 2016, *182*, 346–376. [CrossRef]

- Khan, B.A.; Roy, S.; Tahsin, N.; et al. Antibiotic Resistance of Bioaerosols in Particulate Matter from Indoor Environments of the Hospitals in Dhaka Bangladesh. Sci Rep 2024, *14*, 29884. [CrossRef]

- Bartual, S.G.; Seifert, H.; Hippler, C.; et al. Development of a Multilocus Sequence Typing Scheme for Characterization of Clinical Isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. J Clin Microbiol 2005, *43*, 4382–4390. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Ryoo, N. Comparative Analysis of IR-Biotyper, MLST, cgMLST, and WGS for Clustering of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus faecium in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Microbiol Spectr 2024, *12*, e0411923. [CrossRef]

- Heneghan, C.J.; Spencer, E.A.; Brassey, J.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 and the Role of Orofecal Transmission: A Systematic Review. F1000Research 2021, *10*, 231. [CrossRef]

- Poslova, L.Y.; Sergeeva, A.V.; Kovalishena, O.V. Assessment of Contamination of the Hospital Environment with Intestinal Viruses in the Framework of Epidemiological Surveillance of Acute Intestinal Infections of Viral Etiology. Epidemiologiya 2018, *4*, 42–46. (In Russian).

- Smirnova, S.S.; Zhuikov, N.N.; Egorov, I.A.; et al. Industrial Design Patent No. 132971 Russian Federation. Sampling Scheme of Flushes from Environmental Objects for Simultaneous Assessment of Viral and Bacterial Contamination: No. 2022501675. 2022. (In Russian).

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. J Comput Biol 2012, *19*, 455–477. [CrossRef]

- Astashyn, A.; Tvedte, E.S.; Sweeney, D.; et al. Rapid and Sensitive Detection of Genome Contamination at Scale with FCS-GX. Genome Biol 2024, *25*, 60. [CrossRef]

- Schloss, P.D.; Westcott, S.L.; Ryabin, T.; et al. Introducing Mothur: Open-Source, Platform-Independent, Community-Supported Software for Describing and Comparing Microbial Communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 2009, *75*, 7537–7541. [CrossRef]

- Darling, A.C.; Mau, B.; Blattner, F.R.; Perna, N.T. Mauve: Multiple Alignment of Conserved Genomic Sequence with Rearrangements. Genome Res 2004, *14*, 1394–1403. [CrossRef]

- Bortolaia, V.; Kaas, R.S.; Ruppe, E.; et al. ResFinder 4.0 for Predictions of Phenotypes from Genotypes. J Antimicrob Chemother 2020, *75*, 3491–3500. [CrossRef]

- Maure, A.; Robino, E.; Van der Henst, C. The Intracellular Life of Acinetobacter baumannii. Trends Microbiol 2023, *31*, 1238–1250. [CrossRef]

- Manfi Ahmed, S.; Hashim Yaseen, K.; Mohammed Mahmood, M. Immunological Evaluation of Individuals Infected with Acinetobacter baumannii. Arch Razi Inst 2022, *77*, 1813–1819. [CrossRef]

- Lescure, F.X.; Bouadma, L.; Nguyen, D.; et al. Clinical and Virological Data of the First Cases of COVID-19 in Europe: A Case Series. Lancet Infect Dis 2020, *20*, 697–706. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.; Al-Saryi, N.; Al-Kadmy, I.M.S.; Aziz, S.N. Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii as an Emerging Concern in Hospitals. Mol Biol Rep 2021, *48*, 6987–6998. [CrossRef]

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019: A Systematic Analysis. Lancet 2022, *399*, 629–655. [CrossRef]

- Lau, M.Y.; Ponnampalavanar, S.; Chong, C.W.; et al. The Characterisation of Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Teaching Hospital in Malaysia. Antibiotics 2024, *13*, 1107. [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Zeng, W.; Xu, Y.; et al. Bloodstream Infections Caused by ST2 Acinetobacter baumannii: Risk F actors, Antibiotic Regimens, and Virulence over 6 Years Period in China. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2021, *10*, 16. [CrossRef]

- Pustijanac, E.; Hrenović, J.; Vranić-Ladavac, M.; et al. Dissemination of Clinical Acinetobacter baumannii Isolate to Hospital Environment during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pathogens 2023, *12*, 410. [CrossRef]

- Bedenić, B.; Bratić, V.; Mihaljević, S.; et al. Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria in a COVID-19 Hospital in Zagreb. Pathogens 2023, *12*, 117. [CrossRef]

- Zingg, S.; Kuster, S.; von Rotz, M.; et al. Outbreak with OXA-23-producing Acinetobacter baumannii in a COVID-19 ICU cohort: unraveling routes of transmission. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2024, *13*, 127. [CrossRef]

- Cureño-Díaz, M.A.; Plascencia-Nieto, E.S.; Loyola-Cruz, M.Á.; et al. Gram-Negative ESKAPE Bacteria Surveillance in COVID-19 Pandemic Exposes High-Risk Sequence Types of Acinetobacter baumannii MDR in a Tertiary Care Hospital. Pathogens 2024, *13*, 50. [CrossRef]

| Sample ID | Closest cgST | Mismatches, n | Loci matched, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6-531-2-III_S5 | 1746 | 24 | 98,9 |

| 108-2-III_S9 | 1746 | 110 | 94,8 |

| 50-2-III_S11 | 1746 | 115 | 95,6 |

| 61-II_S53 | 1746 | 115 | 94,6 |

| 72-III_S10 | 1746 | 117 | 94,5 |

| 42-III_S7 | 1746 | 121 | 94,3 |

| 26-III_S22 | 1746 | 129 | 94,0 |

| 55-II_S52 | 1746 | 138 | 93,5 |

| 19-II_S16 | 1746 | 156 | 92,7 |

| 27-III_S34 | 1746 | 171 | 92,0 |

| 346-II_S33 | 1746 | 186 | 91,3 |

| 63-II_S54 | 1746 | 202 | 90,5 |

| 44-2-III_S6 | 1746 | 211 | 90,1 |

| 4-II_S19 | 1746 | 222 | 89,6 |

| 69-II_S57 | 1746 | 228 | 89,3 |

| 198-II_S29 | 1746 | 232 | 89,1 |

| 100-II_S24 | 1746 | 258 | 87,9 |

| 104-II_S26 | 1746, 11006 | 461 | 78,4 |

| 188-II_S28 | 1746 | 583 | 72,7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).