Submitted:

04 December 2024

Posted:

05 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Case Selection and Species Identification

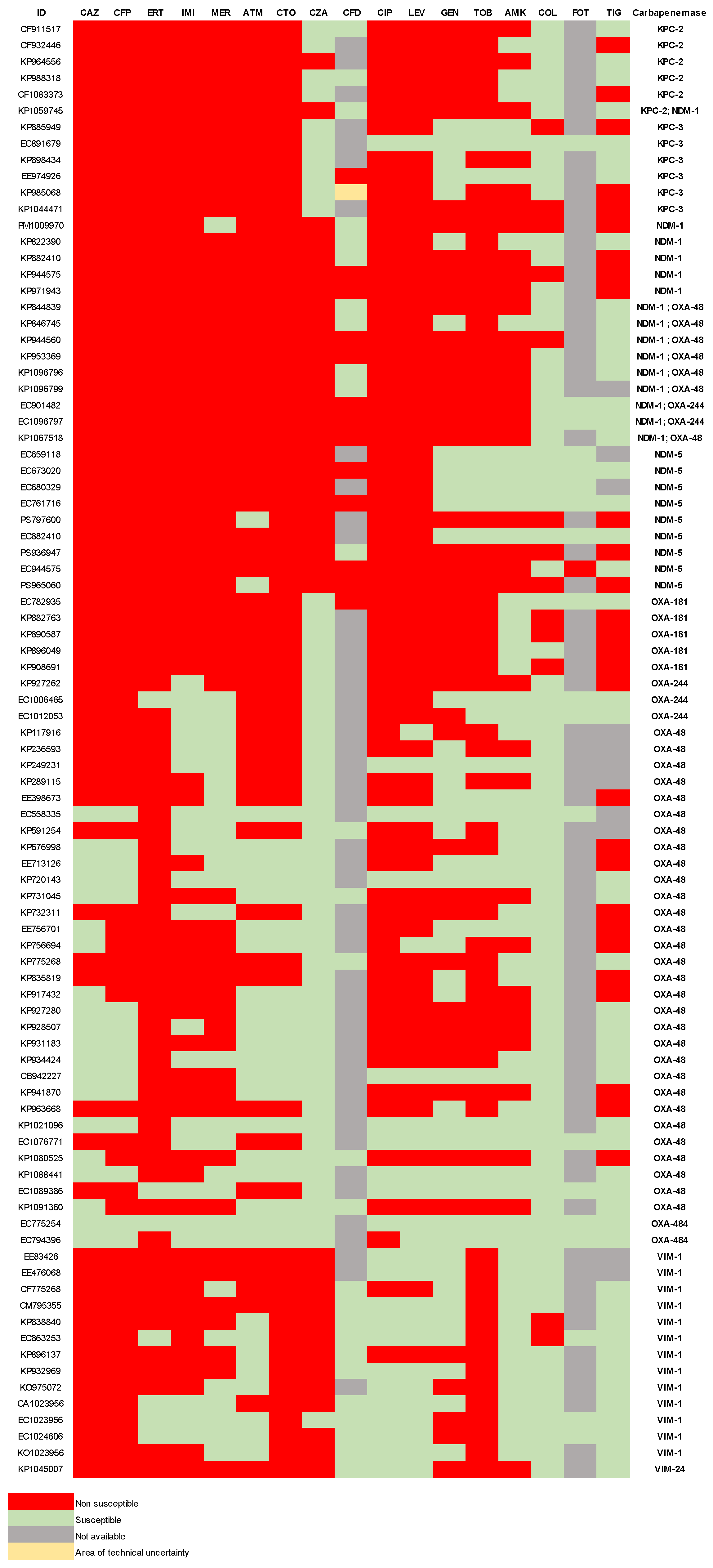

2.2. Antibiotic Susceptibility

2.3. Resistome

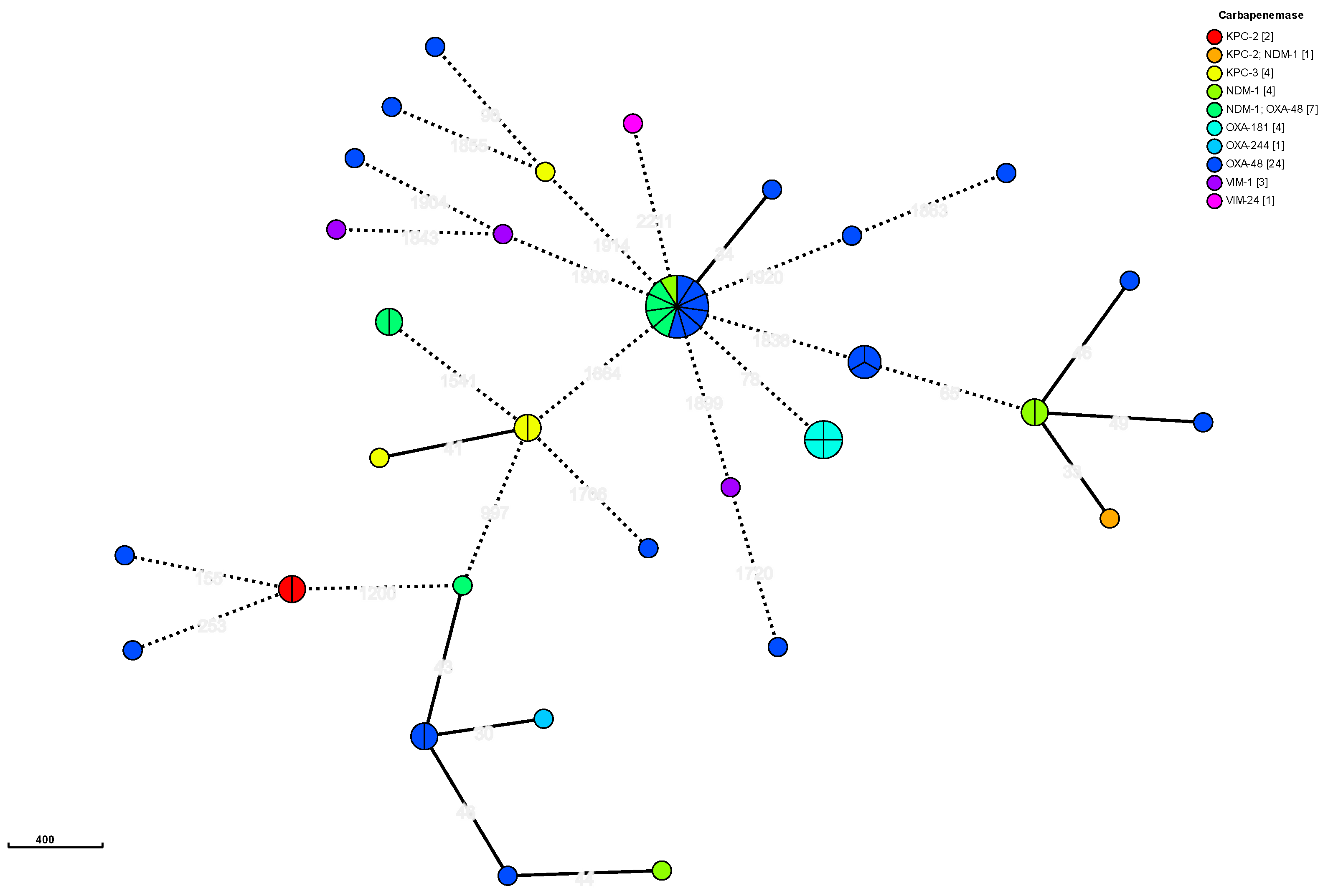

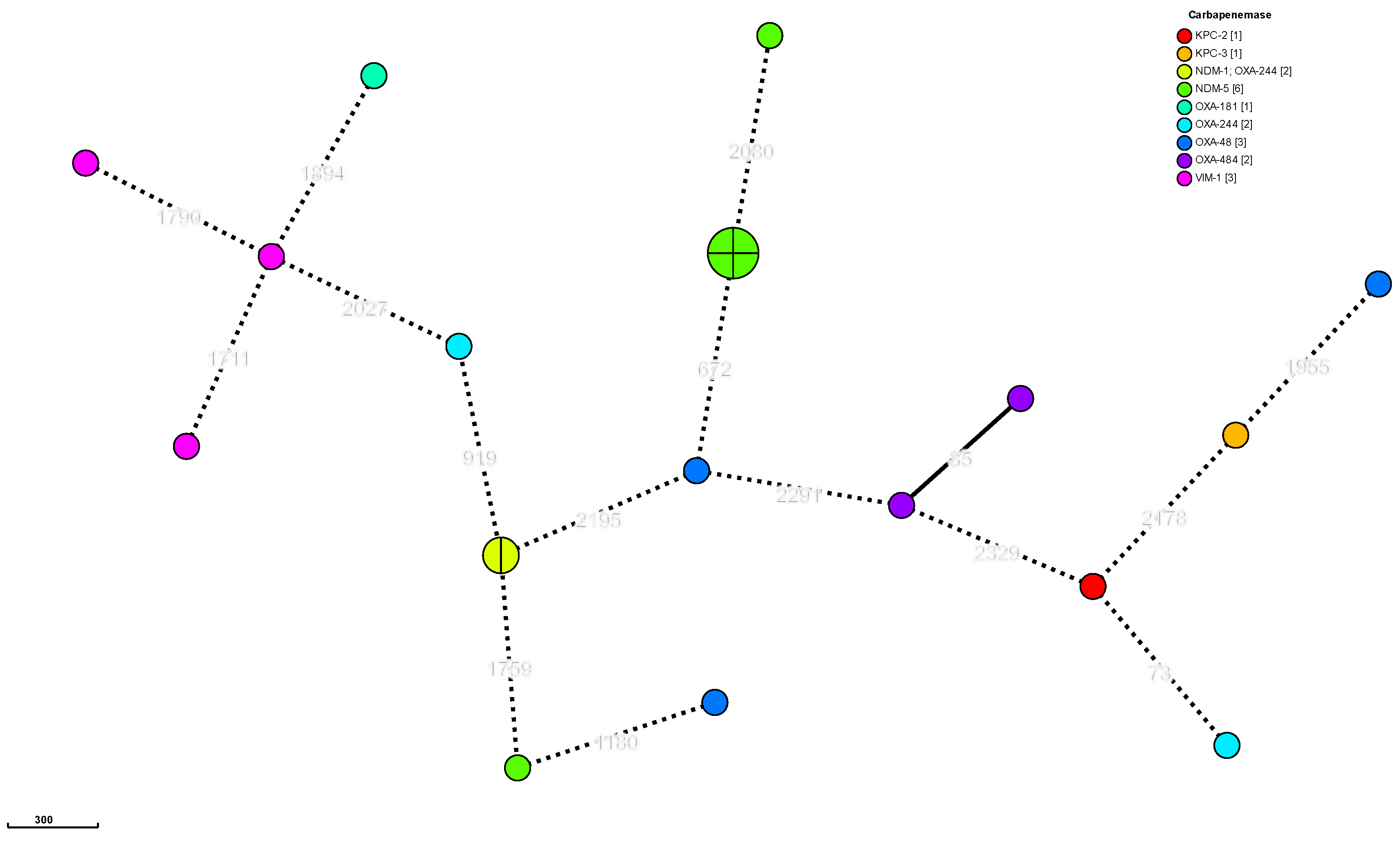

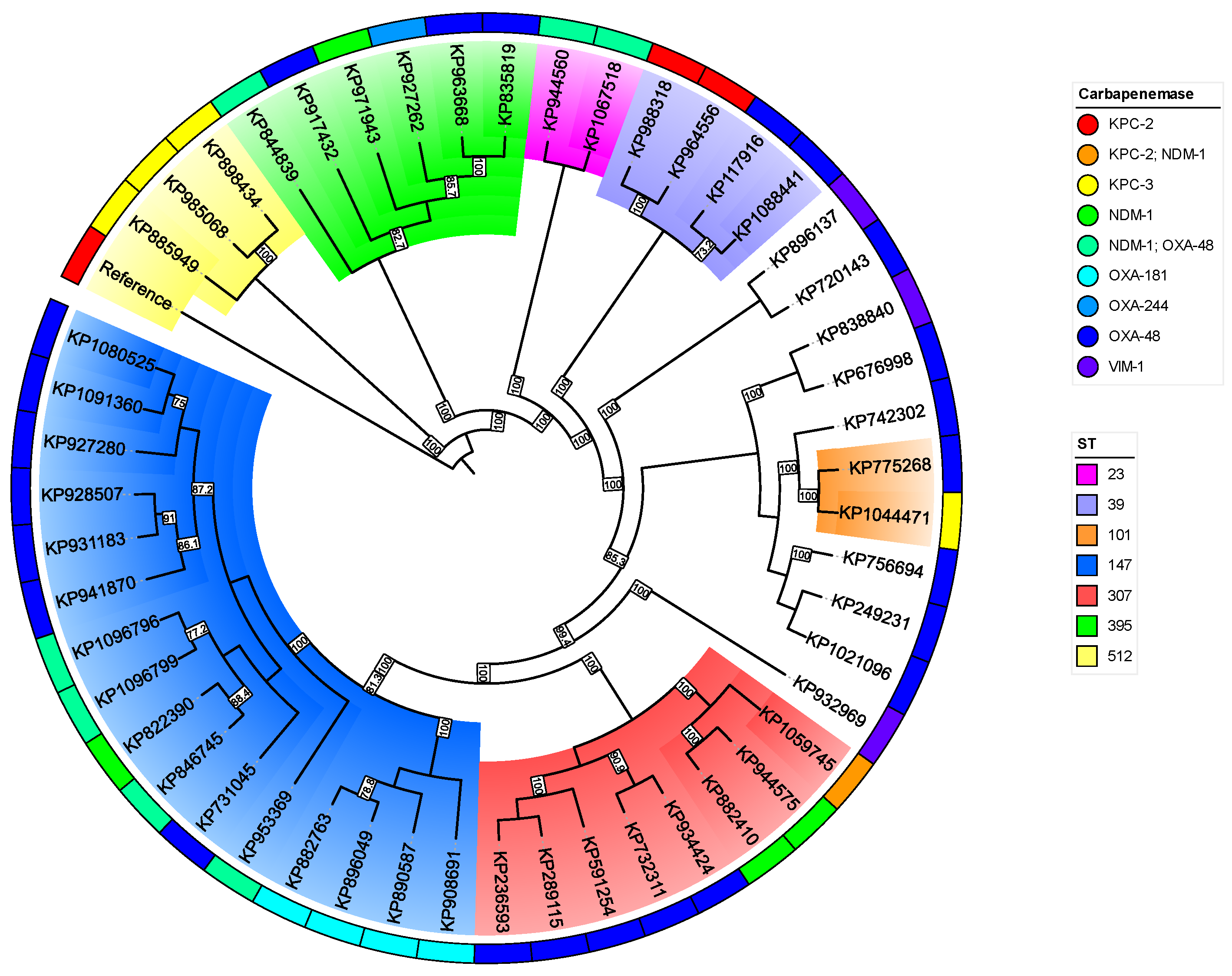

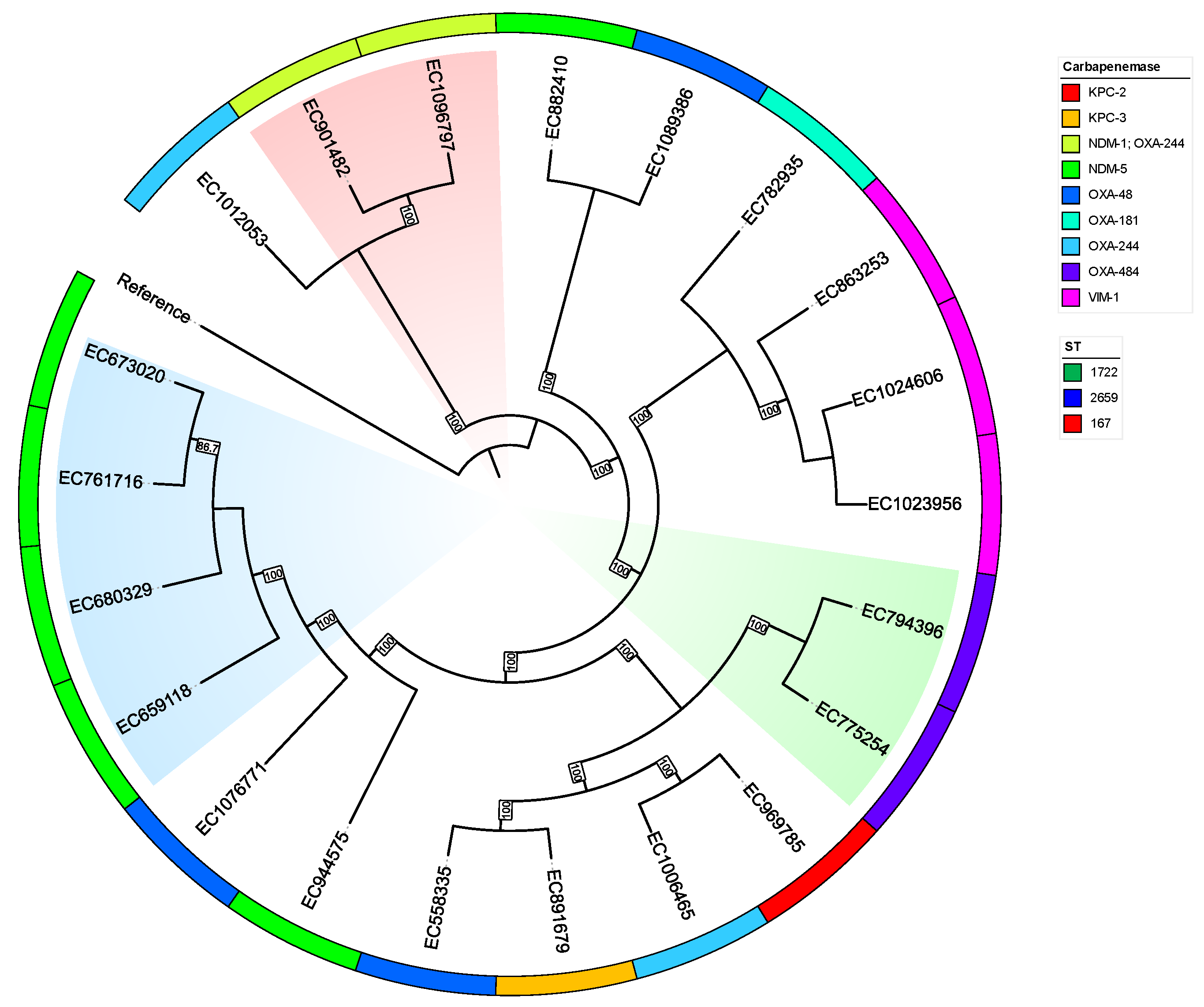

2.4. Typing

2.5. Plasmids

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Strains Included in the Study and Criteria of Selection of CPE

4.2. WGS of CPE Isolates

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Duin D, Doi Y. The global epidemiology of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Virulence. 2017 May 19;8(4):460–9.

- Bonomo RA, Burd EM, Conly J, Limbago BM, Poirel L, Segre JA, et al. Carbapenemase-Producing Organisms: A Global Scourge. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Apr 3;66(8):1290–7. [CrossRef]

- Kim D, Park BY, Choi MH, Yoon EJ, Lee H, Lee KJ, et al. Antimicrobial resistance and virulence factors of Klebsiella pneumoniae affecting 30 day mortality in patients with bloodstream infection. J Antimicrob Chemother [Internet]. 2018 Oct 5 [cited 2024 Nov 23]; Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jac/advance-article/doi/10.1093/jac/dky397/5116214. [CrossRef]

- Wielders CCH, Schouls LM, Woudt SHS, Notermans DW, Hendrickx APA, Bakker J, et al. Epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales in the Netherlands 2017–2019. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2022 Dec;11(1):57. [CrossRef]

- van Duin D, Paterson D. Multidrug Resistant Bacteria in the Community: Trends and Lessons Learned. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016 Jun;30(2):377–90. [CrossRef]

- Manageiro V, Cano M, Furtado C, Iglesias C, Reis L, Vieira P, et al. Genomic and epidemiological insight of an outbreak of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales in a Portuguese hospital with the emergence of the new KPC-124. J Infect Public Health. 2024 Mar;17(3):386–95. [CrossRef]

- Regad M, Lizon J, Alauzet C, Roth-Guepin G, Bonmati C, Pagliuca S, et al. Outbreak of carbapenemase-producing Citrobacter farmeri in an intensive care haematology department linked to a persistent wastewater reservoir in one hospital room, France, 2019 to 2022. Eurosurveillance [Internet]. 2024 Apr 4 [cited 2024 Nov 23];29(14). Available from: https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2024.29.14.2300386. [CrossRef]

- Prioritization of pathogens to guide discovery, research and development of new antibiotics for drug-resistant bacterial infections, including tuberculosis. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017(WHO/EMP/IAU/2017.12).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Risk assessment on the spread of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) : through patient transfer between healthcare facilities, with special emphasis on cross-border transfer [Internet]. LU: Publications Office; 2011 [cited 2024 Nov 23]. Available from: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2900/59034.

- Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios. Plan Nacional Resistencia Antibióticos PRAN [Internet]. PRAN. [cited 2024 Oct 31]. Available from: https://www.resistenciaantibioticos.es/es.

- Gómara M, López-Calleja AI, Iglesia BMPV, Cerón IF, López AR, Pinilla MJR. Detection of carbapenemases and other mechanisms of enzymatic resistance to β-lactams in Enterobacteriaceae with diminished susceptibility to carbapenems in a tertiary care hospital. Enfermedades Infecc Microbiol Clínica. 2018 May;36(5):296–301.

- Petrosillo N, Petersen E, Antoniak S. Ukraine war and antimicrobial resistance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023 Jun;23(6):653–4. [CrossRef]

- Pallett SJC, Boyd SE, O’Shea MK, Martin J, Jenkins DR, Hutley EJ. The contribution of human conflict to the development of antimicrobial resistance. Commun Med. 2023 Oct 25;3(1):153. [CrossRef]

- Watkins RR. Antibiotic stewardship in the era of precision medicine. JAC-Antimicrob Resist. 2022 Jun 21;4(3):dlac066. [CrossRef]

- Tsang KK, Lam MMC, Wick RR, Wyres KL, Bachman M, Baker S, et al. Diversity, functional classification and genotyping of SHV β-lactamases in Klebsiella pneumoniae [Internet]. Genomics; 2024 [cited 2024 Nov 24]. Available from: http://biorxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2024.04.05.587953.

- Ramirez MS, Tolmasky ME. Aminoglycoside modifying enzymes. Drug Resist Updat. 2010 Dec;13(6):151–71.

- Wang S, Ding Q, Zhang Y, Zhang A, Wang Q, Wang R, et al. Evolution of Virulence, Fitness, and Carbapenem Resistance Transmission in ST23 Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae with the Capsular Polysaccharide Synthesis Gene wcaJ Inserted via Insertion Sequence Elements. Garcia-Solache MA, editor. Microbiol Spectr. 2022 Dec 21;10(6):e02400-22.

- Laukkanen-Ninios R, Didelot X, Jolley KA, Morelli G, Sangal V, Kristo P, et al. Population structure of the Yersinia pseudotuberculosis complex according to multilocus sequence typing. Environ Microbiol. 2011 Dec;13(12):3114–27. [CrossRef]

- Herzog KAT, Schneditz G, Leitner E, Feierl G, Hoffmann KM, Zollner-Schwetz I, et al. Genotypes of Klebsiella oxytoca Isolates from Patients with Nosocomial Pneumonia Are Distinct from Those of Isolates from Patients with Antibiotic-Associated Hemorrhagic Colitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2014 May;52(5):1607–16. [CrossRef]

- Zhou H, Liu W, Qin T, Liu C, Ren H. Defining and Evaluating a Core Genome Multilocus Sequence Typing Scheme for Whole-Genome Sequence-Based Typing of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front Microbiol [Internet]. 2017 Mar 8 [cited 2024 Nov 24];8. Available from: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2017.00371/full. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura A, Takahashi H, Arai M, Tsuchiya T, Wada S, Fujimoto Y, et al. Molecular subtyping for source tracking of Escherichia coli using core genome multilocus sequence typing at a food manufacturing plant. Eppinger M, editor. PLOS ONE. 2021 Dec 23;16(12):e0261352. [CrossRef]

- Higgins PG, Prior K, Harmsen D, Seifert H. Development and evaluation of a core genome multilocus typing scheme for whole-genome sequence-based typing of Acinetobacter baumannii. Gao F, editor. PLOS ONE. 2017 Jun 8;12(6):e0179228.

- Gobierno de Aragón. IRAS-PROA Aragón [Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 31]. Available from: https://www.aragon.es/-/iras.

- Endale H, Mathewos M, Abdeta D. Potential Causes of Spread of Antimicrobial Resistance and Preventive Measures in One Health Perspective-A Review. Infect Drug Resist. 2023 Dec 8;16:7515–45. [CrossRef]

- Goryluk-Salmonowicz A, Popowska M. Factors promoting and limiting antimicrobial resistance in the environment – Existing knowledge gaps. Front Microbiol. 2022 Sep 20;13:992268. [CrossRef]

- Symochko L, Pereira P, Demyanyuk O, Pinheiro MNC, Barcelo D. Resistome in a changing environment: Hotspots and vectors of spreading with a focus on the Russian-Ukrainian War. Heliyon. 2024 Jun;10(12):e32716. [CrossRef]

- Logan LK, Weinstein RA. The Epidemiology of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae: The Impact and Evolution of a Global Menace. J Infect Dis. 2017 Feb 15;215(suppl_1):S28–36. [CrossRef]

- Yan JJ. Metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates in a university hospital in Taiwan: prevalence of IMP-8 in Enterobacter cloacae and first identification of VIM-2 in Citrobacter freundii. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002 Oct 1;50(4):503–11. [CrossRef]

- Da Silva G, Domingues S. Insights on the Horizontal Gene Transfer of Carbapenemase Determinants in the Opportunistic Pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii. Microorganisms. 2016 Aug 23;4(3):29. [CrossRef]

- Gottig S, Gruber TM, Stecher B, Wichelhaus TA, Kempf VAJ. In Vivo Horizontal Gene Transfer of the Carbapenemase OXA-48 During a Nosocomial Outbreak. Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Jun 15;60(12):1808–15. [CrossRef]

- Michaelis C, Grohmann E. Horizontal Gene Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Biofilms. Antibiotics. 2023 Feb 4;12(2):328. [CrossRef]

- Willems RPJ, Van Dijk K, Vehreschild MJGT, Biehl LM, Ket JCF, Remmelzwaal S, et al. Incidence of infection with multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria and vancomycin-resistant enterococci in carriers: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023 Jun;23(6):719–31. [CrossRef]

- Budhram DR, Mac S, Bielecki JM, Patel SN, Sander B. Health outcomes attributable to carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020 Jan;41(1):37–43. [CrossRef]

- Suay-García B, Pérez-Gracia MT. Present and Future of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) Infections. Antibiotics. 2019 Aug 19;8(3):122. [CrossRef]

- Sabtcheva S, Stoikov I, Ivanov IN, Donchev D, Lesseva M, Georgieva S, et al. Genomic Characterization of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacter hormaechei, Serratia marcescens, Citrobacter freundii, Providencia stuartii, and Morganella morganii Clinical Isolates from Bulgaria. Antibiotics. 2024 May 16;13(5):455.

- Dilagui I, Loqman S, Lamrani Hanchi A, Soraa N. Antibiotic resistance patterns of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales in Mohammed VI University Hospital of Marrakech, Morocco. Infect Dis Now. 2022 Sep;52(6):334–40. [CrossRef]

- Eshetie S, Unakal C, Gelaw A, Ayelign B, Endris M, Moges F. Multidrug resistant and carbapenemase producing Enterobacteriaceae among patients with urinary tract infection at referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2015 Dec;4(1):12. [CrossRef]

- Boueroy P, Chopjitt P, Hatrongjit R, Morita M, Sugawara Y, Akeda Y, et al. Fluoroquinolone resistance determinants in carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli isolated from urine clinical samples in Thailand. PeerJ. 2023 Nov 8;11:e16401. [CrossRef]

- Almaghrabi R, Clancy CJ, Doi Y, Hao B, Chen L, Shields RK, et al. Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Strains Exhibit Diversity in Aminoglycoside-Modifying Enzymes, Which Exert Differing Effects on Plazomicin and Other Agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014 Aug;58(8):4443–51. [CrossRef]

- Ching C, Orubu ESF, Sutradhar I, Wirtz VJ, Boucher HW, Zaman MH. Bacterial antibiotic resistance development and mutagenesis following exposure to subinhibitory concentrations of fluoroquinolones in vitro: a systematic review of the literature. JAC-Antimicrob Resist. 2020 Sep 30;2(3):dlaa068. [CrossRef]

- Oteo J, Ortega A, Bartolomé R, Bou G, Conejo C, Fernández-Martínez M, et al. Prospective Multicenter Study of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae from 83 Hospitals in Spain Reveals High In Vitro Susceptibility to Colistin and Meropenem. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015 Jun;59(6):3406–12. [CrossRef]

- Karlowsky JA, Lob SH, Siddiqui F, Akrich B, DeRyke CA, Young K, et al. In vitro activity of ceftolozane/tazobactam against multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa from patients in Western Europe: SMART 2017-2020. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2023 May;61(5):106772. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Castillo LC, Fandiño C, Ramos MP, Ramos-Castaneda JA, Rioseco ML, Juliet C. In vitro activity of ceftazidime-avibactam against Gram-negative strains in Chile 2015–2021. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2023 Dec;35:143–8. [CrossRef]

- Lasarte-Monterrubio C, Guijarro-Sánchez P, Vázquez-Ucha JC, Alonso-Garcia I, Alvarez-Fraga L, Outeda M, et al. Antimicrobial Activity of Cefiderocol against the Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacter cloacae Complex and Characterization of Reduced Susceptibility Associated with Metallo-β-Lactamase VIM-1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2023 Apr 13;67(5):e01505-22. [CrossRef]

- Spapen H, Jacobs R, Van Gorp V, Troubleyn J, Honoré PM. Renal and neurological side effects of colistin in critically ill patients. Ann Intensive Care. 2011 May 25;1:14. [CrossRef]

- Cañada-García JE, Moure Z, Sola-Campoy PJ, Delgado-Valverde M, Cano ME, Gijón D, et al. CARB-ES-19 Multicenter Study of Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli From All Spanish Provinces Reveals Interregional Spread of High-Risk Clones Such as ST307/OXA-48 and ST512/KPC-3. Front Microbiol. 2022 Jun 30;13:918362.

- Zou H, Shen Y, Li C, Li Q. Two Phenotypes of Klebsiella pneumoniae ST147 Outbreak from Neonatal Sepsis with a Slight Increase in Virulence. Infect Drug Resist. 2022 Jan;Volume 15:1–12. [CrossRef]

- Peirano G, Chen L, Kreiswirth BN, Pitout JDD. Emerging Antimicrobial-Resistant High-Risk Klebsiella pneumoniae Clones ST307 and ST147. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020 Sep 21;64(10):e01148-20.

- Lowe M, Kock MM, Coetzee J, Hoosien E, Peirano G, Strydom KA, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae ST307 with blaOXA-181, South Africa, 2014–2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019 Apr;25(4):739–47.

- Gálvez-Silva M, Arros P, Berríos-Pastén C, Villamil A, Rodas PI, Araya I, et al. Carbapenem-resistant hypervirulent ST23 Klebsiella pneumoniae with a highly transmissible dual-carbapenemase plasmid in Chile. Biol Res. 2024 Mar 12;57(1):7. [CrossRef]

- Biedrzycka M, Izdebski R, Urbanowicz P, Polańska M, Hryniewicz W, Gniadkowski M, et al. MDR carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae of the hypervirulence-associated ST23 clone in Poland, 2009–19. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2022 Nov 28;77(12):3367–75. [CrossRef]

- Heljanko V, Tyni O, Johansson V, Virtanen JP, Räisänen K, Lehto KM, et al. Clinically relevant sequence types of carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae detected in Finnish wastewater in 2021–2022. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2024 Jan 30;13(1):14. [CrossRef]

- Boutzoukas AE, Komarow L, Chen L, Hanson B, Kanj SS, Liu Z, et al. International Epidemiology of Carbapenemase-Producing Escherichia coli. Clin Infect Dis. 2023 Aug 22;77(4):499–509. [CrossRef]

- Yaici L, Haenni M, Saras E, Boudehouche W, Touati A, Madec JY. blaNDM-5 -carrying IncX3 plasmid in Escherichia coli ST1284 isolated from raw milk collected in a dairy farm in Algeria. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016 Sep;71(9):2671–2.

- Shrestha B, Tada T, Shimada K, Shrestha S, Ohara H, Pokhrel BM, et al. Emergence of Various NDM-Type-Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli Clinical Isolates in Nepal. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017 Dec;61(12):e01425-17. [CrossRef]

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://www.eucast.org/eucast_news/news_singleview?tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=518&cHash=2509b0db92646dffba041406dcc9f20c.

- EUCAST_detection_of_resistance_mechanisms_170711.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2024 Nov 27]. Available from: https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Resistance_mechanisms/EUCAST_detection_of_resistance_mechanisms_170711.pdf.

- Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, Holt KE. Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. Phillippy AM, editor. PLOS Comput Biol. 2017 Jun 8;13(6):e1005595. [CrossRef]

- Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2013 Apr 15;29(8):1072–5.

- Seppey M, Manni M, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: Assessing Genome Assembly and Annotation Completeness. In: Kollmar M, editor. Gene Prediction [Internet]. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2019 [cited 2024 Nov 24]. p. 227–45. (Methods in Molecular Biology; vol. 1962). Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-1-4939-9173-0_14. [CrossRef]

- Ondov BD, Starrett GJ, Sappington A, Kostic A, Koren S, Buck CB, et al. Mash Screen: high-throughput sequence containment estimation for genome discovery. Genome Biol. 2019 Dec;20(1):232. [CrossRef]

- Orakov A, Fullam A, Coelho LP, Khedkar S, Szklarczyk D, Mende DR, et al. GUNC: detection of chimerism and contamination in prokaryotic genomes. Genome Biol. 2021 Dec;22(1):178.

- Wick RR, Schultz MB, Zobel J, Holt KE. Bandage: interactive visualization of de novo genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2015 Oct 15;31(20):3350–2. [CrossRef]

- Lumpe J, Gumbleton L, Gorzalski A, Libuit K, Varghese V, Lloyd T, et al. GAMBIT (Genomic Approximation Method for Bacterial Identification and Tracking): A methodology to rapidly leverage whole genome sequencing of bacterial isolates for clinical identification. Chen CC, editor. PLOS ONE. 2023 Feb 16;18(2):e0277575. [CrossRef]

- Seemann T. mlst [Internet]. GitHub. 2022 [cited 2024 Oct 31]. Available from: https://github.com/tseemann/mlst.

- Lam MMC, Wick RR, Watts SC, Cerdeira LT, Wyres KL, Holt KE. A genomic surveillance framework and genotyping tool for Klebsiella pneumoniae and its related species complex. Nat Commun. 2021 Jul 7;12(1):4188. [CrossRef]

- Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014 Jul 15;30(14):2068–9.

- Casimiro-Soriguer CS, Muñoz-Mérida A, Pérez-Pulido AJ. Sma3s: A universal tool for easy functional annotation of proteomes and transcriptomes. PROTEOMICS. 2017 Jun;17(12):1700071. [CrossRef]

- Alcock BP, Huynh W, Chalil R, Smith KW, Raphenya AR, Wlodarski MA, et al. CARD 2023: expanded curation, support for machine learning, and resistome prediction at the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023 Jan 6;51(D1):D690–9. [CrossRef]

- Seemann T. ABRicate [Internet]. GitHub. 2020 [cited 2024 Oct 31]. Available from: https://github.com/tseemann/abricate.

- Zankari E, Hasman H, Cosentino S, Vestergaard M, Rasmussen S, Lund O, et al. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012 Nov 1;67(11):2640–4.

- Seemann T. Snippy [Internet]. GitHub. 2020 [cited 2024 Oct 31]. Available from: https://github.com/tseemann/snippy.

- Croucher NJ, Page AJ, Connor TR, Delaney AJ, Keane JA, Bentley SD, et al. Rapid phylogenetic analysis of large samples of recombinant bacterial whole genome sequences using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015 Feb 18;43(3):e15–e15.

- Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, Von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: A Fast and Effective Stochastic Algorithm for Estimating Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 2015 Jan;32(1):268–74.

- Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh BQ, Wong TKF, Von Haeseler A, Jermiin LS. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat Methods. 2017 Jun;14(6):587–9. [CrossRef]

- Hoang DT, Chernomor O, Von Haeseler A, Minh BQ, Vinh LS. UFBoot2: Improving the Ultrafast Bootstrap Approximation. Mol Biol Evol. 2018 Feb 1;35(2):518–22.

- Silva M, Machado MP, Silva DN, Rossi M, Moran-Gilad J, Santos S, et al. chewBBACA: A complete suite for gene-by-gene schema creation and strain identification. Microb Genomics [Internet]. 2018 Mar 1 [cited 2024 Nov 24];4(3). Available from: https://www.microbiologyresearch.org/content/journal/mgen/10.1099/mgen.0.000166.

- Hyatt D, Chen GL, LoCascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010 Dec;11(1):119. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Z, Alikhan NF, Sergeant MJ, Luhmann N, Vaz C, Francisco AP, et al. GrapeTree: visualization of core genomic relationships among 100,000 bacterial pathogens. Genome Res. 2018 Sep;28(9):1395–404. [CrossRef]

- Carattoli A, Zankari E, García-Fernández A, Voldby Larsen M, Lund O, Villa L, et al. In Silico Detection and Typing of Plasmids using PlasmidFinder and Plasmid Multilocus Sequence Typing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014 Jul;58(7):3895–903.

- Robertson J, Nash JHE. MOB-suite: software tools for clustering, reconstruction and typing of plasmids from draft assemblies. Microb Genomics [Internet]. 2018 Aug 1 [cited 2024 Nov 24];4(8). Available from: https://www.microbiologyresearch.org/content/journal/mgen/10.1099/mgen.0.000206. [CrossRef]

- Antipov D, Hartwick N, Shen M, Raiko M, Lapidus A, Pevzner PA. plasmidSPAdes: assembling plasmids from whole genome sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2016 Nov 15;32(22):3380–7. [CrossRef]

- Schwengers O, Jelonek L, Dieckmann MA, Beyvers S, Blom J, Goesmann A. Bakta: rapid and standardized annotation of bacterial genomes via alignment-free sequence identification: Find out more about Bakta, the motivation, challenges and applications, here. Microb Genomics [Internet]. 2021 Nov 30 [cited 2024 Nov 24];7(11). Available from: https://www.microbiologyresearch.org/content/journal/mgen/10.1099/mgen.0.000685. [CrossRef]

- Grant JR, Enns E, Marinier E, Mandal A, Herman EK, Chen C yu, et al. Proksee: in-depth characterization and visualization of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023 Jul 5;51(W1):W484–92.

- Jain C, Rodriguez-R LM, Phillippy AM, Konstantinidis KT, Aluru S. High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat Commun. 2018 Nov 30;9(1):5114. [CrossRef]

| Species | 2021 |

2021 carba |

2022 |

2022 carba |

2023 |

2023 carba |

Total |

| E. coli | 6629 | 0 | 7590 | 7 | 8870 | 14 | 23089 |

| K. pneumoniae | 1646 | 5 | 2102 | 14 | 2784 | 40 | 6532 |

| P. mirabilis | 649 | 0 | 741 | 0 | 891 | 1 | 2281 |

| E. cloacae | 424 | 3 | 542 | 2 | 579 | 3 | 1545 |

| K. oxytoca | 324 | 0 | 389 | 0 | 405 | 2 | 1118 |

| Citrobacter spp | 280 | 5 | 357 | 7 | 455 | 7 | 1092 |

| S. marcescens | 205 | 0 | 217 | 0 | 246 | 1 | 668 |

| M. morganii | 177 | 0 | 261 | 0 | 284 | 0 | 722 |

| K. aerogenes | 142 | 0 | 162 | 0 | 179 | 0 | 483 |

| P. stuartii | 42 | 0 | 60 | 1 | 70 | 2 | 172 |

| Others | 110 | 0 | 126 | 0 | 207 | 0 | 443 |

| Total | 10628 | 13 | 12547 | 31 | 14970 | 70 | 38189 |

| Carbapenemase/Species | K. pneumoniae complex | E. coli | E. cloacae complex | Citrobacter spp | P. stuartii | K. oxytoca | P. mirabilis | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KPC-2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| KPC-3 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| NDM-1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| NDM-5 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| VIM-1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 13 |

| VIM-24 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| OXA-48 | 24 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 31 |

| OXA-181 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| OXA-244 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| OXA-484 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| NDM-1 + OXA-48 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| NDM-1 + OXA-244 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| NDM-1 + KPC-2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 51 | 20 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 91 |

| CPE | Carbapenemases | ST | cgMLST cluster | BLEE | AmpC | gyrA mutation | parC mutation | Aminoglycosides modifing genes | Plasmid_replicons (carbapenemase) | Predicted_mobility | Mean plasmid size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K. pneumoniae | OXA-48 | 13,15,39,101, 147,307,346, 395,405,685,4872 |

Yes | CTX-M-15 | 0 | S83I,S83F,D87A | S80I | Several | IncL/M,IncR | Variable | 46443 |

| OXA-181 | 147 | Yes | CTX-M-15 | 0 | S83I | S80I | Several | rep_cluster_1195 | Mainly non-mobilizable | 40801 | |

| OXA-244 | 395 | No | CTX-M-15 | 0 | S83I | S80I | Several | IncL/M | Conjugative | 87763 | |

| KPC-2 | 39 | Yes | CTX-M-15 | 0 | S83I,D87N | S80I | Several | IncFIB,IncFII,IncX3,ColRNAI_rep_cluster_1857 | Mainly conjugative | 94778 | |

| KPC-3 | 101,512 | Yes | 0 | 0 | S83I,S83Y,D87N | S80I | Several | IncFIB,IncFII,IncHI1B,IncR | Conjugative | 63166 | |

| NDM-1 | 147,307,395 | Yes | CTX-M-15 | 0 | S83I | S80I | Several | IncFIB,IncFII,IncHI1B | Conjugative | 278576 | |

| VIM-1 | 2,685,844,387 | No | 0 | DHA-1 | 0 | 0 | Several | IncL/M | Conjugative | 71362 | |

| KPC-2 + NDM-1 | 307 | No | 0 | 0 | S83I | S80I | aph(3')-VI only | IncFIB,IncHI1B,rep_cluster_1254 | Conjugative | 332589 | |

| NDM-1 + OXA-48 | 23,147,395 | Yes | CTX-M-15 | 0 | S83I | S80I | Several | IncFIB,IncFII,IncHI1B | Variable | 101820 | |

| E. coli | OXA-48 | 38,127,1598 | No | CTX-M-15 | 0 | S83L | 0 | Several | IncFIA,IncFII | non-mobilizable | 21541 |

| OXA-181 | 410 | No | 0 | CMY-4 | S83L,D87N | S80I | Several | IncX3 | non-mobilizable | 27916 | |

| OXA-244 | 44,13730 | No | CTX-M-15 | CMY-132 | S83L,D87N | S80I | aadA5 only | ND | ND | ND | |

| OXA-484 | 1722 | No | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | aadA2 only | rep_cluster_1195 | non-mobilizable | 14615 | |

| KPC-2 | 131 | No | 0 | CMY-132 | S83L | 0 | Several | IncFIB,IncFII,rep_cluster_2183 | Conjugative | 84857 | |

| KPC-3 | 135 | No | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | APH(3') only | IncX3 | Conjugative | 58796 | |

| NDM-5 | 46,405,2659 | No | CTX-M-55 | CMY-42 | D87N, S83L | S80I | aadA2 only | IncFIA,IncFIC,IncFIB | Mainly conjugative | 105572 | |

| VIM-1 | 29,327,539 | No | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Several | IncL/M,IncL/M, IncI-gamma/K1 | Variable | 49209 | |

| NDM-1 + OXA-244 | 167 | Yes | CTX-M-15 | 0 | D87N, S83L | S80I | AAC(3)-Iid only | IncC,rep_cluster_1254 | Conjugative | 210764 | |

| Citrobacter spp | OXA-48 | 225 | ND | 0 | CYM-101 | 0 | 0 | 0 | IncL/M | Conjugative | 61961 |

| KPC-2 | 21259 | ND | CTX-M-15,CTX-M-9 | CMY-106,CYM-159 | S83I | S80I | Several | IncP,IncU | Monilizable | 29296 | |

| VIM-1 | 488493563 | ND | CTX-M-9 | CMY-2,CMY-48 | 0 | 0 | Several | IncL/M,IncY | Mainly conjugative | 57471 | |

| Enterobacer spp | OXA-48 | 13,24 | ND | CTX-M-15 | ACT-1,MIR-5 | S83I | 0 | 0 | IncL/M | Conjugative | 64843 |

| KPC-3 | 51 | ND | 0 | ACT-40 | 0 | 0 | Several | IncN | Conjugative | 50662 | |

| VIM-1 | 108198 | ND | CTX-M-9 | ACT-55 | 0 | 0 | Several | IncL/M,IncHI2A | Conjugative | 152182 | |

| Klebsiella spp | VIM-1 | 59 | ND | CTX-M-9 | 0 | S463A | 0 | Several | IncL/M,IncR | Conjugative | 174918 |

| VIM-24 | 4365 | ND | CTX-M-9 | 0 | S463A | 0 | Several | IncHI2A,rep_cluster_1088 | Conjugative | 289821 | |

| Providencia stuartii | NDM-5 | 11,23 | ND | 0 | CMY-16 | D87G | 0 | Several | IncC,rep_cluster_1254 | Variable | 78040 |

| Proteus mirabilis | NDM-1 | 446 | ND | VEB-6 | 0 | S463A | 0 | Several | ND | ND | ND |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).