Submitted:

18 January 2025

Posted:

20 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Samples Collection and Ethical Consideration

Identification of A. baumannii

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test

DNA Extraction

Detection of MDR Genes

Agarose Gel Electrophoresis

Statistical Analysis

Results

Demographic Data Results

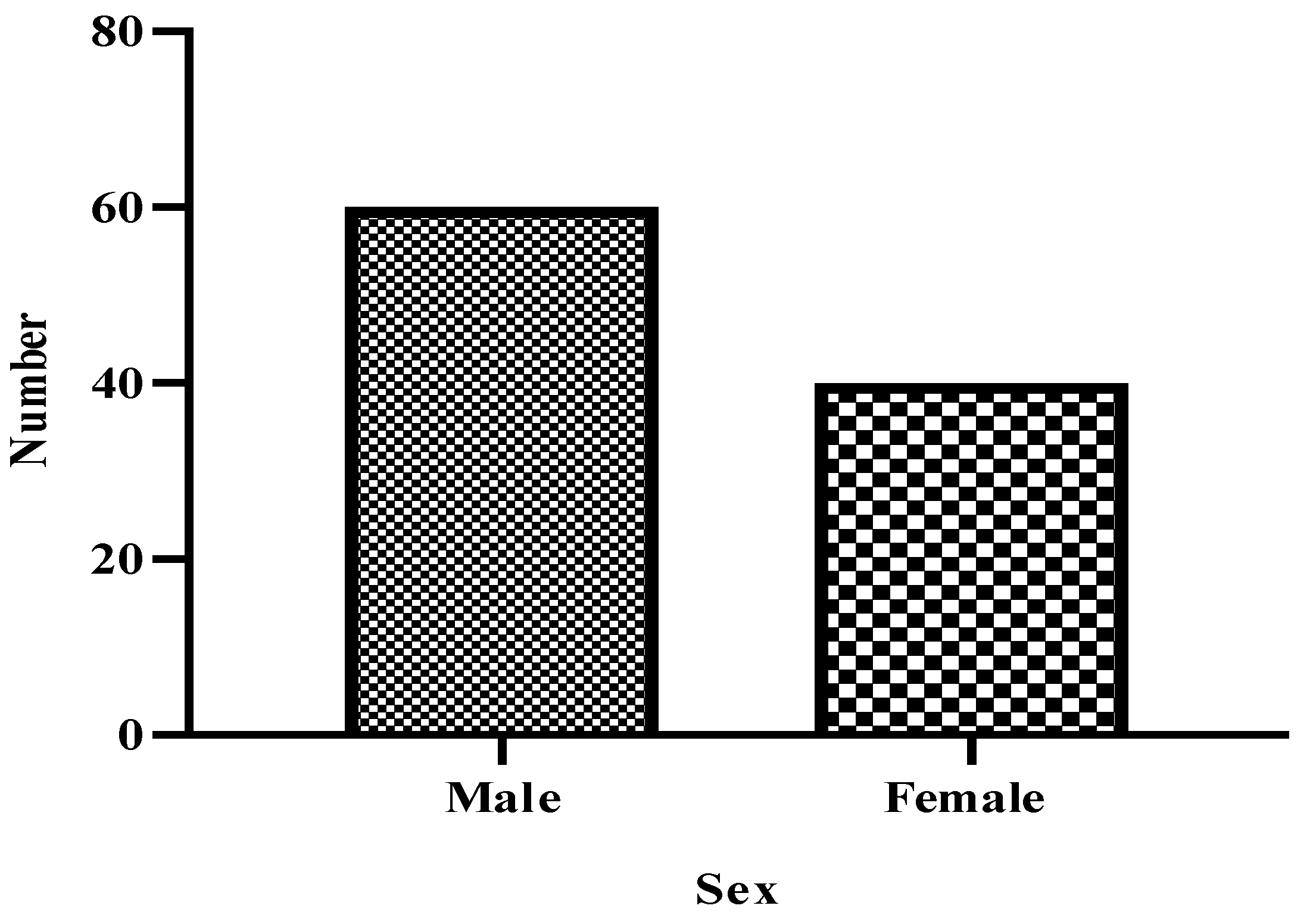

Sex and Age

Samples Characteristics

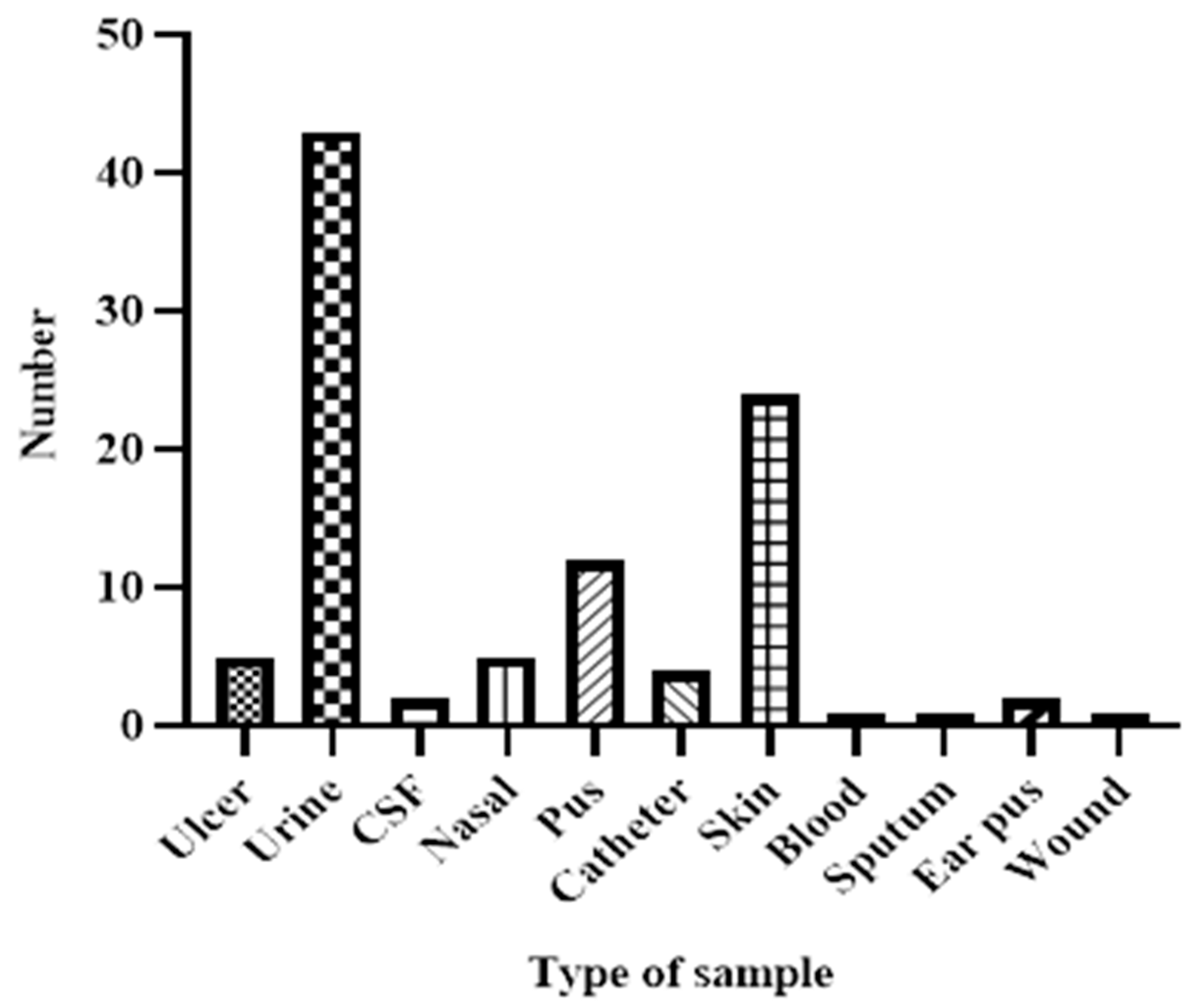

Sample Type

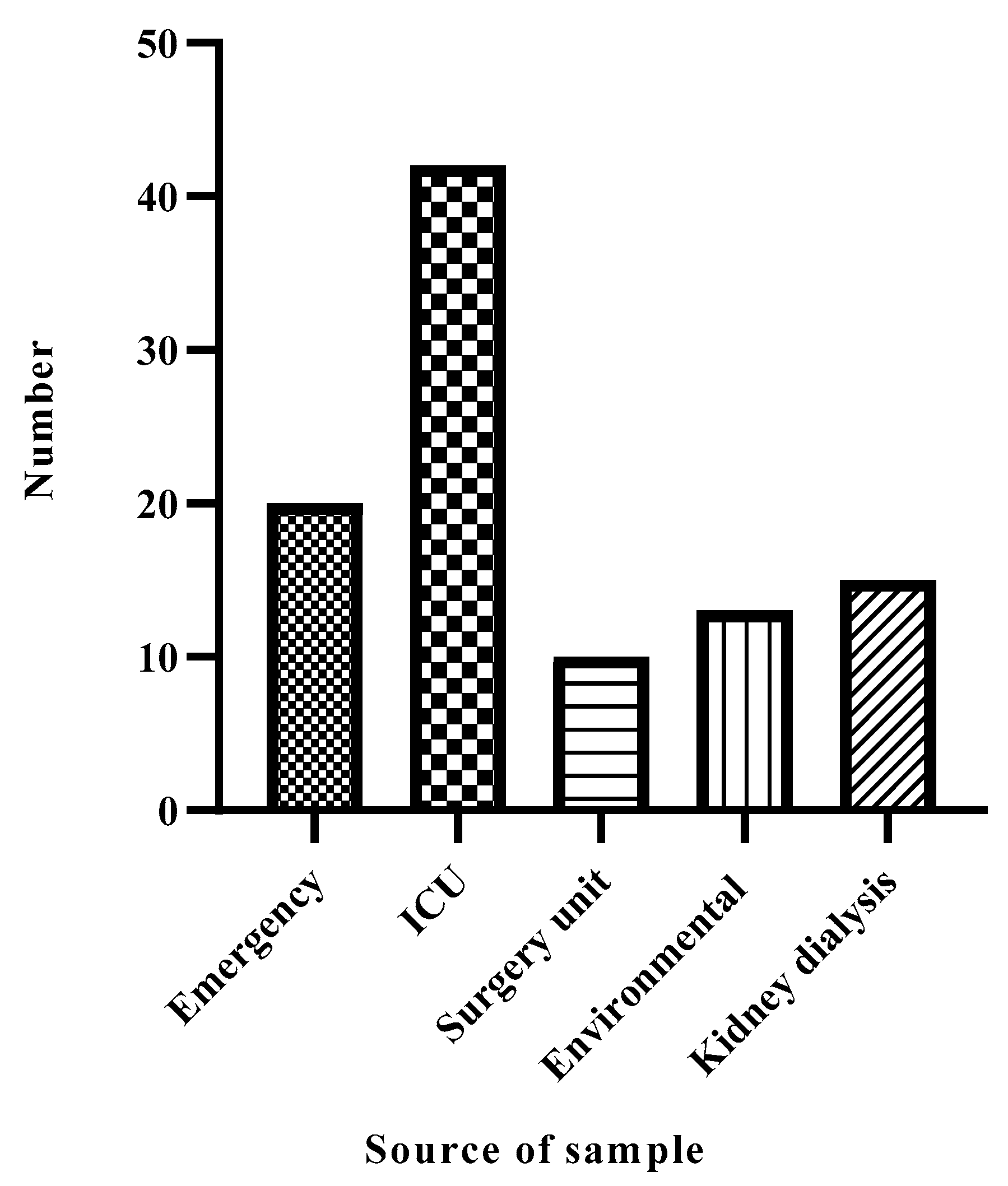

Prevalence of A. baumannii Among the Hospital Departments

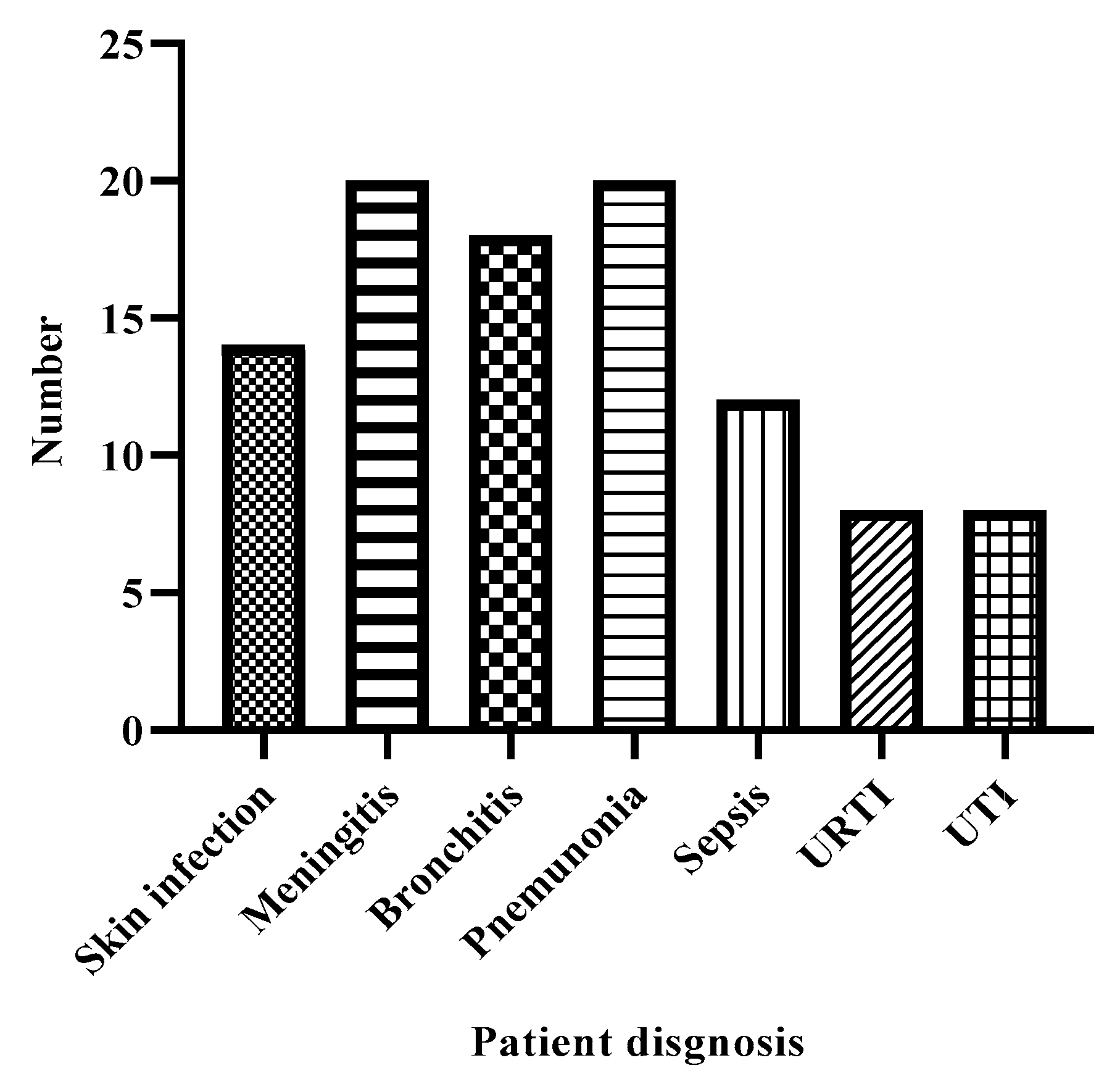

Patients Diagnosis

Correlations Coefficient Analysis

Gender and Sample Type

| Gender | Sample Type | ||

| Gender | Pearson Correlation | 1 | .206* |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .040 | ||

| N | 100 | 100 | |

| Sample Type | Pearson Correlation | .206* | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .040 | ||

| N | 100 | 100 | |

Age and Diagnosis

| Age | Diagnosis | ||

| Age | Pearson Correlation | 1 | .150 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .136 | ||

| N | 100 | 100 | |

| Diagnosis | Pearson Correlation | .150 | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .136 | ||

| N | 100 | 100 | |

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing for A. baumannii

| Antibiotic | Sensitivity | Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent |

| Vancomycin | R | 71 | 71.0 | 71.0 | 71.0 |

| S | 27 | 27.0 | 27.0 | 98.0 | |

| I | 2 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 100.0 | |

| Oxacillin | R | 66 | 66.0 | 66.0 | 66.0 |

| S | 34 | 34.0 | 34.0 | 100.0 | |

| I | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Tigecycline | R | 52 | 52.0 | 52.0 | 52.0 |

| S | 39 | 39.0 | 39.0 | 91.0 | |

| I | 9 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 100.0 | |

| Teicoplanin | R | 49 | 49.0 | 49.0 | 49.0 |

| S | 49 | 49.0 | 49.0 | 98.0 | |

| I | 2 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 100.0 | |

| Erythromycin | R | 48 | 48.0 | 48.0 | 48.0 |

| S | 52 | 52.0 | 52.0 | 100.0 | |

| I | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Amikacin | R | 47 | 47.0 | 47.0 | 47.0 |

| S | 49 | 49.0 | 49.0 | 96.0 | |

| I | 4 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 100.0 | |

| Linezolid | R | 45 | 45.0 | 45.0 | 45.0 |

| S | 49 | 49.0 | 49.0 | 94.0 | |

| I | 6 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 100.0 | |

| Gentamycin | R | 50 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 |

| S | 47 | 47.0 | 47.0 | 97.0 | |

| I | 3 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 100.0 | |

| Rifampin | R | 53 | 53.0 | 53.0 | 53.0 |

| S | 47 | 47.0 | 47.0 | 100.0 | |

| I | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Levofloxacin | R | 67 | 67.0 | 67.0 | 67.0 |

| S | 33 | 33.0 | 33.0 | 100.0 | |

| I | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

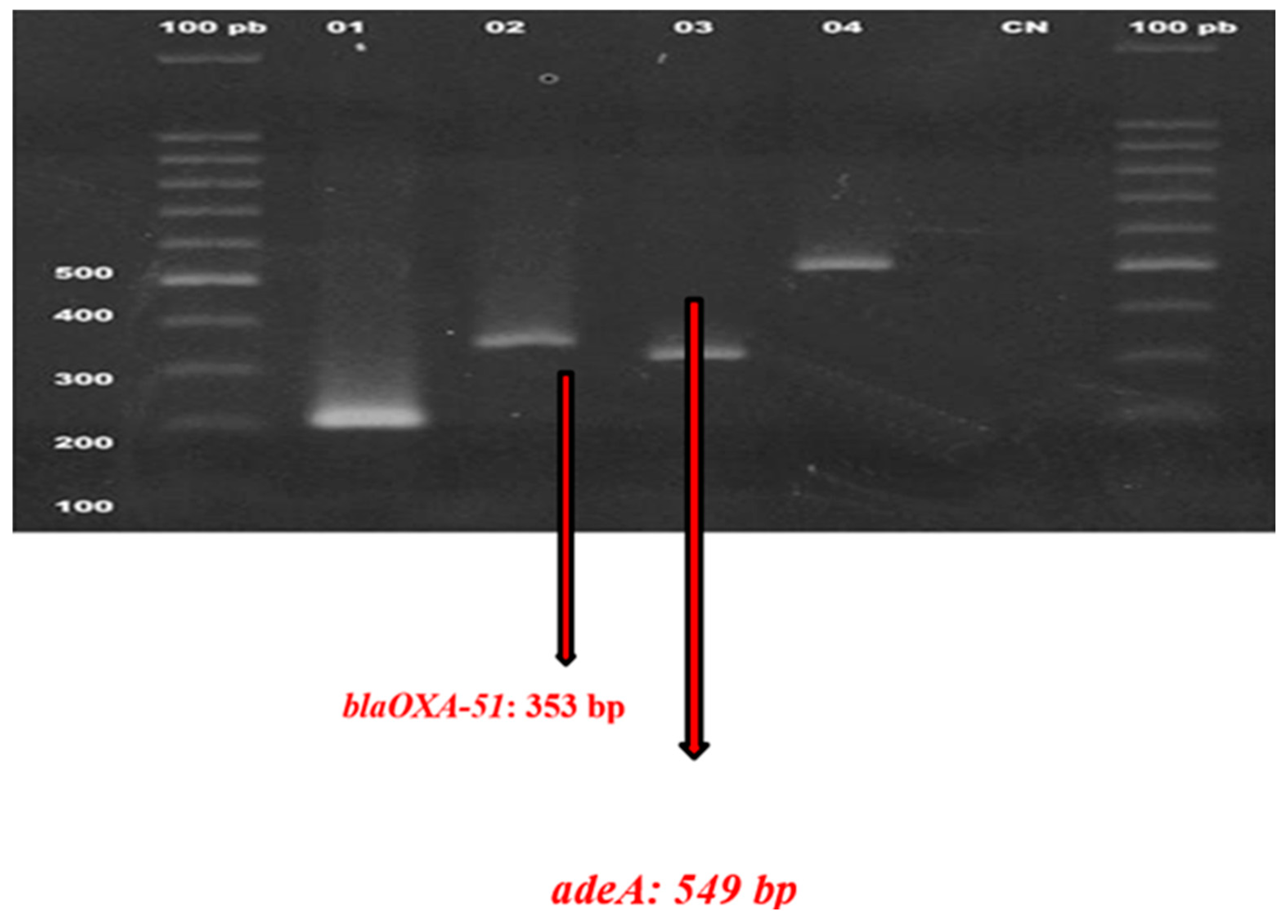

Detection of Oxa and Efflux Genes Among the Isolates

| Target genes | PrevalenceRate% | P-value |

| OXA genes | ||

| blaOXA-51 | 15% | 0.06 |

| blaOXA-23 | 80% | 0.005 |

| blaOXA-24 | 77% | 0.02 |

| Efflux genes | ||

| AdeA | 5% | 0.07 |

| AdeB | 8% | 0.75 |

| AdeC | 14% | 0.15 |

| AdeS | 7% | 0.75 |

Discussion

Limitations and Future Research

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peleg AY, Seifert H and Paterson DL. Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clinical microbiology reviews 2008, 21, 538–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antunes LC, Visca P and Towner KJ. Acinetobacter baumannii: evolution of a global pathogen. Pathogens and disease 2014, 71, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlFaris EaM, Al-Karablieh N, Odat NA, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii from Jordan: Complicated Carbapenemase Combinations. Jordan Journal of Biological Sciences 2024; 17.

- Perez F, Hujer AM, Hujer KM, et al. Global challenge of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2007, 51, 3471–3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan Z, Li X, Li S, et al. Nosocomial surveillance of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: a genomic epidemiological study. Microbiology Spectrum 2024, 12, e02207–02223. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Ding Y, Wei Y, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: A challenge in the intensive care unit. Frontiers in microbiology 2022, 13, 1045206. [Google Scholar]

- Torres HA, Vázquez EG, Yagüe G, et al. [Multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumanii:clinical update and new highlights]. Rev Esp Quimioter 2010, 23, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gedefie A, Demsis W, Ashagrie M, et al. Acinetobacter baumannii Biofilm Formation and Its Role in Disease Pathogenesis: A Review. Infect Drug Resist, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Jia W, Li C, Zhang H, et al. Prevalence of genes of OXA-23 carbapenemase and AdeABC efflux pump associated with multidrug resistance of Acinetobacter baumannii isolates in the ICU of a comprehensive hospital of Northwestern China. International journal of environmental research and public health 2015, 12, 10079–10092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou C and Yang F. Drug-resistant gene of blaOXA-23, blaOXA-24, blaOXA-51 and blaOXA-58 in Acinetobacter baumannii. International journal of clinical and experimental medicine 2015; 8: 13859.

- Tacconelli E, Carrara E, Savoldi A, et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. The Lancet infectious diseases 2018; 18: 318-327.

- Ayoub Moubareck C and Hammoudi Halat, D. Insights into Acinetobacter baumannii: A Review of Microbiological, Virulence, and Resistance Traits in a Threatening Nosocomial Pathogen. Antibiotics (Basel), 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyepong N, Fordjour F and Owusu-Ofori A. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in healthcare settings in Africa. Frontiers in Tropical Diseases 2023; 4: 1110125.

- Karampatakis T, Antachopoulos C, Tsakris A, et al. Molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in Greece: an extended review (2000–2015). Future Microbiology 2017; 12: 801-815.

- Al-Tamimi M, Albalawi H, Alkhawaldeh M, et al. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in Jordan. Microorganisms 2022; 10: 849.

- Kyriakidis I, Vasileiou E, Pana ZD, et al. Acinetobacter baumannii antibiotic resistance mechanisms. Pathogens 2021; 10: 373.

- Wong MH-y, Chan BK-w, Chan EW-c, et al. Over-expression of IS Aba1-Linked intrinsic and exogenously acquired OXA type carbapenem-hydrolyzing-class D-ß-Lactamase-encoding genes is key mechanism underlying Carbapenem Resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Frontiers in microbiology 2019; 10: 2809.

- Cecchini T, Yoon E-J, Charretier Y, et al. Deciphering multifactorial resistance phenotypes in Acinetobacter baumannii by genomics and targeted label-free proteomics. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 2018; 17: 442-456.

- Huang L, Sun L, Xu G, et al. Differential susceptibility to carbapenems due to the AdeABC efflux pump among nosocomial outbreak isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii in a Chinese hospital. Diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease 2008; 62: 326-332.

- Magnet S, Courvalin P and Lambert T. Resistance-nodulation-cell division-type efflux pump involved in aminoglycoside resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii strain BM4454. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2001; 45: 3375-3380.

- Diep DTH, Tuan HM, Ngoc KM, et al. The clinical features and genomic epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections at a tertiary hospital in Vietnam. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen M and Joshi S. Carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii, and their importance in hospital-acquired infections: a scientific review. Journal of applied microbiology 2021; 131: 2715-2738.

- Harding CM, Hennon SW and Feldman MF. Uncovering the mechanisms of Acinetobacter baumannii virulence. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2018; 16: 91-102.

- Capuozzo, M.; Zovi, A.; Langella, R.; Ottaiano, A.; Cascella, M.; Scognamiglio, M.; Ferrara, F. Optimizing Antibiotic Use: Addressing Resistance Through Effective Strategies and Health Policies. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sheboul, S.A.; Al-Moghrabi, S.Z.; Shboul, Y.; Atawneh, F.; Sharie, A.H.; Nimri, L.F. Molecular Characterization of Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Isolated from Intensive Care Unit Patients in Jordanian Hospitals. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkshoorn, L. , Nemec, A. & Seifert, H. An increasing threat in hospitals: multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Nat Rev Microbiol. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Baño J, Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez B, Machuca I, Pascual A. Treatment of Infections Caused by Extended-Spectrum-Beta-Lactamase-, AmpC-, and Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2018 Feb 14;31(2):e00079-17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajan V, Vijayan A, Puthiyottu Methal A, Lancy J, Sivaraman GK (2023) Genotyping of Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from a tertiary care hospital in Cochin, South India. Access Microbiol 5(000662):v4. [CrossRef]

- Owais D, Al-Groom RM, AlRamadneh TN, Alsawalha L, Khan MSA, Yousef OH, Burjaq SZ. Antibiotic susceptibility and biofilm forming ability of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from Jordanian patients with diabetic foot ulcer. Iran J Microbiol. 2024 Aug;16(4):450-458. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Genes | Primers sequences |

Amplicon size |

References |

| blaOXA-51 |

F:TAATGCTTTGATCGGCCTTG R: TGGATTGCACTTCATCTTGG |

760 | [3,10] |

| blaOXA-23 |

F: GATCGGATTGGAGAACCAGA R: ATTTCTGACCGCATTTCCAT |

774 | [3,10] |

| blaOXA-24 |

F: TTCCCCTAACATGAATTTGT R: GTACTAATCAAAGTTGTGAA |

828 | [3,10] |

| AdeA |

F: GGCGTATTGGGCAATCTTTTGT R: GTCACCGACTTTCAAGCCTTTG |

1157 | [3,9] |

| AdeB |

F: TGGCGGAATGAAGTATGT R: GCAGTGCGGCAGGTTAG |

1323 | [3,9] |

| AdeC |

F: GACAATCGTATCTCGTGGACTC R: AGCAATTTTCTGGTCAGTTTCC |

1331 | [3,9] |

| AdeS |

F:GTGGACGTTAGGTCAAGTTCTG R:TGTTATCTTTTGCGGCTGT ATT |

949 | [3,9] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).