1. Introduction

Among the reproductive biotechnologies used in sheep farming, artificial insemination (AI) stands out for effectively contributing to genetic improvement. However, transcervical access to the uterus in ewes is a limiting factor for AI, as unlike cattle, rectal manipulation is not possible, and ewes have a narrow cervical ostium with rigid and tortuous structures, making the passage of the insemination pipette difficult and limiting the technique's application [

1,

2]. In sheep, video-assisted surgery is efficiently employed in repeated follicular aspirations via laparoscopy and as a diagnostic method for reproductive abnormalities and diseases through vaginoscopy [

3,

4].

The development of minimally invasive techniques in reproductive medicine has significantly transformed both human and veterinary gynecology, enabling procedures with greater accuracy, reduced trauma, and improved outcomes [

5]. In human medicine, hysteroscopic approaches to endometrial access and intervention such as directed biopsies and ablations have demonstrated superiority over blind procedures by increasing diagnostic precision and minimizing complications [

6]. These principles are equally applicable to veterinary medicine, where adapting and validating such techniques in small ruminants can improve fertility rates while ensuring animal welfare [

5,

6].

Furthermore, recent guidelines and systematic reviews emphasize the importance of tailoring endoscopic techniques to anatomical variability, using appropriate instrumentation and visualization systems to optimize diagnostic and therapeutic success [

7]. Transposing these recommendations to veterinary settings, particularly in species like sheep with complex cervical anatomy, underscores the relevance of studies aimed at refining transcervical procedures [

8]. Thus, exploring endoscopic-assisted insemination aligns with a broader scientific effort to enhance reproductive efficiency through precision, safety, and innovation [

7,

8].

To optimize reproduction in ruminants, new endoscopic techniques for vaginoscopy have been developed, allowing better vaginal evaluation and even transcervical passage without rectal palpation [

9]. Given these endoscopic possibilities and the need to improve AI in sheep, the present study aimed to develop endoscopic techniques for videovaginoscopy and hysteroscopy, as well as transcervical artificial insemination in sheep.

2. Materials and Methods

The animal study protocol number 6261300323 (ID 002208) was approved by the National Council for Control of Animal Experimentation and was approved by the Ethics Committee on Animal Use of the Federal University of Para. Thirty-five multiparous Santa Inês and crossbred Santa Inês ewes, aged 3 to 5 years, with a body condition score of approximately 3 on a 1-5 scale [

10], and an average body weight of 45 ± 4.6 kg were used. The animals were deemed healthy following clinical and ultrasonographic examination of their reproductive organs. The ewes were housed in pens with ad libitum access to water and mineral salt, and were fed a balanced diet (corn silage/commercial concentrate - 14% CP and 65% TDN) according to their experimental group.

Initially, a pilot study was conducted with five ewes not subjected to a fixed-time artificial insemination (FTAI) protocol, which underwent AI via endoscopy (Endoscopc Piloty Grup without protocol - GPen, n=5). The procedure was performed using a rigid endoscope of 2.7mm diameter and 17.5cm length, with a 10º viewing angle, coupled to a 3mm working sheath, connected to a video surgery system. The ewes were physically restrained with their hind limbs elevated. A vaginal speculum was used to visualize the cervix, followed by the instillation of 2 mL of 2% lidocaine hydrochloride into the vaginal fornix, with a one-minute wait before the procedure. The cervix was fixed using 25cm Allis forceps, and the endoscope was introduced through the ostium with the aim of passing through the cervix and entering the uterus. The endoscope was then withdrawn, leaving its sheath in place to allow the passage of the insemination pipette; however, insemination was not performed.

Subsequently, a second pilot study was conducted with ten additional multiparous ewes subjected to the same AI technique as GPen but now under a standard short FTAI protocol (Endoscopc Piloty Grup winth protocol - GPep n=10). The protocol consisted of six days of progesterone (0.33 g of progesterone - CIDR®, Pfizer, Brazil), associated with prostaglandin (37.5 μg of cloprostenol sodium - Sincrocio®, Ourofino, Brazil) and equine chorionic gonadotropin (300 IU of eCG - Novormon®, Zoetis, Brazil). Inseminations were performed 48 to 55 hours after progesterone device removal using thawed semen from a ram from a biotechnology center. If all cervical rings were passed or five minutes of manipulation elapsed, the endoscope was withdrawn, and semen was deposited using the protective sheath at the site of maximum progression. Pregnancy confirmation was conducted 21 days post-AI via transrectal ultrasonography using a MyLabTM 30VET device (Esaote S.p.A., Genoa, Liguria, Italy) with a 7.5 MHz linear transducer.

At the end of this phase, the frequency distribution of cervical passage, pregnancy rates, and relevant observations were recorded. Data were analyzed using the chi-square test, with absolute and percentage data processed using the Bioestat 5.3 statistical package. In this section, where applicable, authors are required to disclose details of how generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has been used in this paper (e.g., to generate text, data, or graphics, or to assist in study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation). The use of GenAI for superficial text editing (e.g., grammar, spelling, punctuation, and formatting) does not need to be declared.

2.1. Study After Adaptations of the Previous Phase

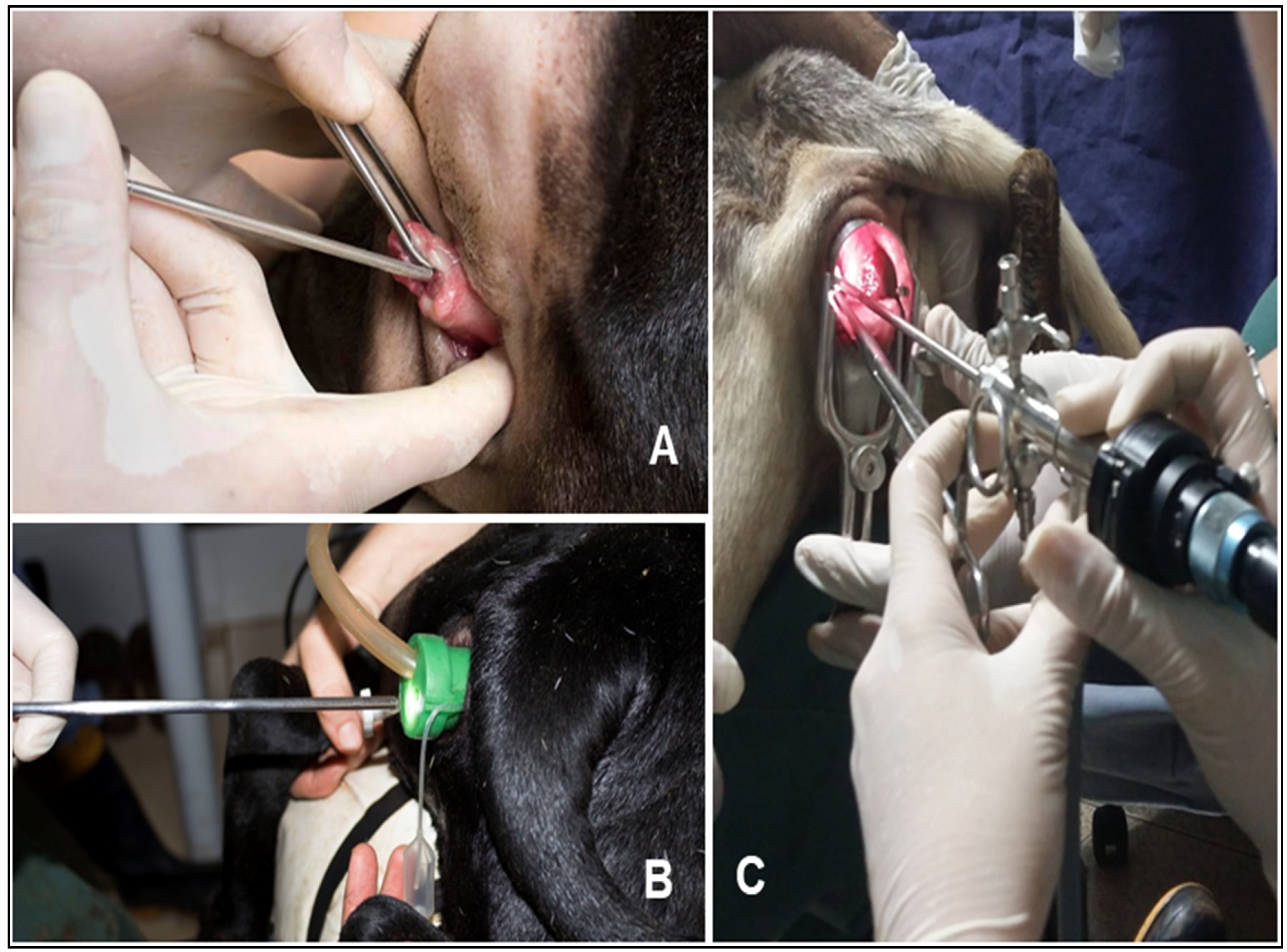

After evaluating the results of the pilot phase, two groups of ewes were used. These ewes underwent the same FTAI protocol as GPep. They were divided into two groups: conventional FTAI with cervical traction as the control group with cervical traction (GC, n=10) and endoscopic vaginoscopy with vaginal insufflation and no cervical fixation (Endoscopic Vaginoscopy Grup - GVe, n=10).

For GC, the hind limbs of the animal were elevated onto an 80 cm high stand, and the perineal region was cleaned beforehand. A 15 cm vaginal speculum was then used to open and visualize the cervix. Additionally, 2 mL of 2% lidocaine hydrochloride was instilled into the vaginal fornix, with a one-minute wait before the procedure. With the aid of an external light source, the cervix was visualized, classified, and grasped using a 25 cm Allis forceps. The cervix was then traction to the vaginal vestibule, and an ovine applicator (13 cm long and 2 mm in diameter) was used for cervical passage. When the uterine interior was reached or after three minutes of cervical manipulation, thawed semen was deposited using the semen applicator at the deepest accessible location.

For GVe, FTAI was performed with the animal in a quadrupedal position, following the same antisepsis procedure as in the other groups, but without local anesthesia. A multi-access portal (Multiport, Sitracc Less, Edlo) was inserted into the vaginal vestibule with the aid of a non-spermicidal lubricant. After positioning the multiport, it was connected to the video surgery insufflation system, promoting vaginal cavity insufflation with carbon dioxide (CO

2) at a flow rate of 6 L/min at a pressure of 10 mmHg. A rigid endoscope (5 mm in diameter, 17.5 cm in length, and 0º viewing angle) connected to the video surgery system was used to evaluate the vaginal cavity and cervical ostium. Subsequently, a commercial 31 cm caprine semen applicator was inserted into one of the working channels of the multiport trocar for cervical passage. Semen deposition was performed as soon as all cervical rings were passed or after three minutes of cervical manipulation (

Figure 1).

For this stage, cervical ostia were classified according to Kershaw et al. [

11] as: duckbill, flap, smooth, papilla, or rosette. The number of rings passed was measured according to the progression of the applicator or endoscope, and semen deposition location was classified based on the number of rings passed, categorized according to Taqueda et al [

12] as superficial cervical (up to the 3rd ring), deep cervical (beyond the 3rd ring), and intrauterine, thus determining the cervical passage rate.

Serum samples were also collected to evaluate inflammatory response at seven time points: 5 minutes before AI, and at 20 minutes, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 hours post-AI. Samples were obtained via jugular venipuncture using vacuum tubes containing EDTA (Vacutainer, BD, Brazil), immediately centrifuged at 1500g for 10 minutes. Plasma was collected and stored in microtubes at -80ºC until analysis. Plasma fibrinogen was analyzed using the method described by Millar et al. [

13] through heat precipitation at 56ºC and manual refractometer reading, with values expressed in mg/dL. Pregnancy diagnosis was performed using the same methodology as in the pilot phase.

Collected data were subjected to normality testing (Shapiro test) [

14]. The number of rings passed, semen deposition site, and plasma fibrinogen levels were compared between AI techniques using the Kruskal-Wallis test [

15] and Dunn's post-hoc test [

16]. Cervical manipulation time was compared using ANOVA and Tukey's post-hoc test [

17]. Pregnancy rate was compared using the chi-square test [

18], and fibrinogen variation was calculated as a percentage change from baseline (considered as 0). Analyses were performed using Bioestat 5.3, with significance set at p<0.05.

3. Results

During the initial study phase, cervical passage during insemination was successful in 100% of the GPen group (5/5 sheep) and only 10% of the GPep group (1/10 sheep). In the GPep group, 90% of inseminations (9/10) were superficial cervical, while only 10% (1/10) reached the uterus (intrauterine insemination). The only female that became pregnant in this group was the one that received intrauterine insemination, resulting in a pregnancy rate of 10%. Conversely, all sheep in the GPen group had visible cervical trajectories, allowing successful instrument passage. In the GPep group, this passage was hindered by whitish secretions within the cervical lumen characteristic of estrus, preventing uterine access in 90% of synchronized females. This finding led to the development of the GVe technique, which was compared to the conventional GC technique (Tab.1). The time required for insemination was significantly greater in the GPep group (249 ± 101 seconds) compared to the GC (158 ± 50) and GVe (129 ± 29) groups, which did not differ from each other (p = 0.0016), as shown in

Table 1.

The number of cervical rings traversed during artificial insemination was significantly greater in the GC group (3.5 ± 3.3) compared to the GVe group (1.6 ± 1.2; p = 0.0065). Regarding semen deposition location, 20% of inseminations were intrauterine and 80% deep cervical in the GC group. In the GVe group, the same percentages were observed for intrauterine (20%) and superficial cervical (80%) inseminations. Despite technical differences, the pregnancy rate was 20% in both groups, with no statistical difference (p = 1.0), as shown in

Table 2.

Plasma fibrinogen analysis revealed time-dependent dynamics. While all values remained within the species’ physiological range (100–500 mg/dL), GVe exhibited a transient fibrinogen increase at 24 hours post-insemination (p=0.0017), followed by a reduction across all groups thereafter (p=0.003). GC displayed the lowest fibrinogen levels at 72 hours (p=0.006), which remained stable until the study endpoint (

Table 3).

Evaluation of cervical os morphology identified the papilla type as the most prevalent (33%, 10/30), followed by smooth (23%, 7/30), rosette (20%, 6/30), flap (17%, 5/30), and duckbill (7%, 2/30) (

Table 4). It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

4. Discussion

The pilot study proved efficient for hysteroscopic evaluation in non-estrous ewes. The caliber of the endoscope and protective sheath was effective for the examination. The technique using vaginoscopy was also efficient, without complications for the health of the ewes. Studies on goats using hysteroscopy techniques with a 4mm rigid endoscope reported severe injuries, leading to adaptation with a 2mm endoscope, which showed no complications [

19]. Estrous mucus obstructed visualization; however, washing with solutions could be a simple option to improve visualization when accessing the uterus. However, solutions commonly used in mucus removal or lumen dilation, such as saline (NaCl 0.09%) or lactated Ringer's solution, are spermicidal [

20].

Even without intrauterine visualization, the AI technique via endoscopic vaginoscopy/hysteroscopy was promising, providing a more precise and higher-quality gynecological examination due to better animal restraint and potential cervical transposition, though not highly efficient in this study. In sheep, methods for better cervical visualization remain a challenge. A newly developed speculum specifically for ewes has demonstrated improved quality in gynecological examination [

21]. Studies on cows have shown that endoscopic techniques improve overall examination quality, including cervix evaluation [

9]. A major advantage of AI via endoscopic vaginoscopy is the absence of cervical traction, which has been reported as a factor that can cause reproductive tract injuries and raise concerns regarding animal welfare [

22].

Plasma fibrinogen values remained within normal limits for sheep [

23], demonstrating minimal invasiveness of the AI procedure overall. However, GVe exhibited higher fibrinogen values than the other two groups in the first two post-AI measurements, suggesting that vaginal insufflation with CO2 may have contributed to the increase. Nonetheless, this was not physiologically significant. According to Sabes et al. [

24], fibrinogen serves as a sensitive indicator of inflammatory response in ruminants. The decrease in values at 72 hours post-procedure in GVe was similar to observations in transcervical embryo collection, indicating that such procedures do not elevate fibrinogen levels beyond species-accepted limits [

25]. Other studies show that cervical traction for AI affects cortisol levels in ewes, even under sedation, reinforcing the potential benefits of AI via endoscopic vaginoscopy as an alternative [

26].

The procedure duration was longer in the pilot study's endoscopic technique with estrus synchronization protocol, as mucus impaired visualization and consequently extended the procedure time. The other techniques had similar durations, suggesting that AI duration was not significantly influenced, as times were comparable to those reported in other AI studies using cervical traction and fixation [

27]. Similar to the cervical traction AI technique, the ability to observe the cervical ostium, whether through cervical traction or post-insufflation, is a favorable factor for insemination. This technique has been successfully used for intravaginal biopsy [

28], although previous studies used lower CO

2 pressure and flow rates than the present study. Silva et al [

29] used a pressure of 10 mmHg for vaginoscopy in a vaginal tumor resection procedure in a dog, demonstrating that the procedure is viable at this pressure. During the current study, no discomfort was observed in the animals, confirming that anesthesia was unnecessary for this AI technique.

The frequency of cervical ostium types in this experiment differed from other literature reports, with papilla-type ostia being most common and duckbill-type least common. Franco et al. [

30], using the same breed as this study, found that the duckbill-type ostium was more prevalent (46%). This discrepancy may be due to the absence of animal selection based on cervical type, which exhibits significant variability. Due to the lack of repeatability, as demonstrated by Moura et al. [

31], cervical ostium transposition remains a challenge, making AI a highly complex procedure. The semen deposition site did not significantly influence pregnancy rates among the groups, but positive pregnancies were observed in ewes where cervical transposition was achieved. This result aligns with findings by Rekha et al. [

32] and Duarte et al. [

27], which demonstrated better efficiency for intrauterine AI, deep cervical AI, superficial cervical AI, and intravaginal AI, respectively. The semen deposition site did not significantly influence pregnancy rates among the groups, but positive pregnancies were observed in ewes where cervical transposition was achieved. This result aligns with findings by Rekha et al. [

32] and Duarte et al. [

27], which demonstrated better efficiency for intrauterine AI, deep cervical AI, superficial cervical AI, and intravaginal AI, respectively.

Overall, cervical transposition success and pregnancy rates may be influenced by several factors: inseminator skill, AI timing, and semen type. The practice and familiarity of the technician with the insemination method are directly related to pregnancy rates [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. Another potential factor influencing the low pregnancy rates was the semen volume and processing method used [

35]. The AI technique via endoscopic vaginoscopy showed good application, already allowing cervical passage without traction. This technique could yield better results if combined with cervical dilators, as demonstrated by Duarte et al. [

27].

Future investigations should explore strategies to improve cervical transposition rates, including the use of cervical dilators, pharmacological modulators of cervical relaxation, or new synchronization protocols tailored to endoscopic procedures. Comparative studies involving different breeds, cervical morphologies, and reproductive statuses may help identify key anatomical or physiological predictors of success. Additionally, further research is needed to assess the impact of these techniques on animal welfare, stress biomarkers, and long-term fertility outcomes. Refining instrumentation and standardizing training protocols for operators could also enhance reproducibility and field application. These efforts may contribute to consolidating endoscopic insemination as a viable tool in reproductive biotechnologies for small ruminants.

5. Conclusions

The use of transcervical endoscopic techniques in Santa Inês sheep proved to be feasible and safe for artificial insemination procedures. Videovaginoscopy enabled effective visualization of the cervix and intrauterine semen deposition in some animals without the need for cervical traction. Despite anatomical limitations, the pregnancy rates obtained were comparable between the evaluated methods, and the inflammatory markers remained within physiological limits, reinforcing the minimal invasiveness and clinical applicability of the technique. Although not yet highly efficient, endoscopic approaches already allow intrauterine access and represent a promising alternative for improving assisted reproduction in ruminants, particularly sheep.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R.T.; R.S.G.M; P.D.A.d.S.; C.J.C.S.; N.N.R.; D.P.V.; T.d.S.C.; R.L.A.; F.D.d.O.M.; R.d.S.A.; W.R.R.V. and P.P.M.T.; methodology, A.R.T.; R.S.G.M; P.D.A.d.S.; C.J.C.S.; N.N.R.; D.P.V.; T.d.S.C.; R.L.A.; F.D.d.O.M.; R.d.S.A. and P.P.M.T.; validation, A.R.T.; R.S.G.M; P.D.A.d.S.; C.J.C.S.; N.N.R.; D.P.V.; T.d.S.C.; R.L.A.; F.D.d.O.M.; R.d.S.A.; W.R.R.V. and P.P.M.T.; formal analysis, A.R.T.; R.S.G.M; P.D.A.d.S.; C.J.C.S.; N.N.R.; D.P.V.; T.d.S.C.; R.L.A.; F.D.d.O.M.; R.d.S.A.; W.R.R.V. and P.P.M.T.; investigation, A.R.T.; R.S.G.M; P.D.A.d.S.; C.J.C.S.; N.N.R.; D.P.V.; T.d.S.C.; R.L.A.; F.D.d.O.M.; R.d.S.A.; W.R.R.V. and P.P.M.T.; data curation, A.R.T.; R.S.G.M; P.D.A.d.S.; C.J.C.S.; N.N.R.; D.P.V.; T.d.S.C.; R.L.A.; F.D.d.O.M.; R.d.S.A.; W.R.R.V.; F.M.S. and P.P.M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R.T. and P.P.M.T.; writing—review and editing, F.M.S. and P.P.M.T.; supervision, W.R.R.V. and P.P.M.T.; project administration, F.M.S.; W.R.R.V and P.P.M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol number 6261300323 (ID 002208) was approved by the National Council for Control of Animal Experimentation (CONCEA) and was approved by the Ethics Committee on Animal Use of the Federal University of Para (CEUA/UFPA).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico), FAPESPA (Fundação Amazônia de Amparo a Estudos e Pesquisas do Estado do Pará) and CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Insemination |

| FTAI |

Fixed-time Artificial Insemination |

| CP |

Crude Protein |

| TDN |

Total Digestible Nutrients |

| GC |

Control Group with cervical traction |

| GPen |

Endoscopc Piloty Grup without protocol |

| GPep |

Endoscopc Piloty Grup winth protocol |

| GVe |

Endoscopic Vaginoscopy Grup |

| eCG |

equine Chorionic Gonadotropin |

References

- Casali, R.; Pinczak, A.; Cuadro, F.; Guillen-Munoz, J. M.; Mazzalira, A.; Menchaca, A. Semen deposition by cervical, transcervical and intrauterine route for fixed-time artificial insemination (FTAI) in the ewe. Theriogenology 2017, 103, 30-35. [CrossRef]

- El Amiri, B.; Rahim, A. Exploring Endogenous and Exogenous Factors for Successful Artificial Insemination in Sheep: A Global Overview. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 86. [CrossRef]

- Padilha, L. C.; Teixeira, P. P. M.; Pires-Buttler, E. A.; Apparicio, M.; Motheo, T. F.; Savi, P. A. P.; Vicente, W.R.R. In vitro maturation of oocytes from Santa Ines ewes subjected to consecutive sessions of follicular aspiration by laparoscopy. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2014, 49, 243-248. [CrossRef]

- Easley, J.; Shasa, D.; Hackett, E. Vaginoscopy in Ewes Utilizing a Laparoscopic Surgical Port Device. J. Vet. Med. 2017, 30, 290. [CrossRef]

- Vitale, S. G.; Riemma, G.; Alonso Pacheco, L.; Carugno, J.; Haimovich, S.; Tesarik, J.; De Franciscis, P. Hysteroscopic endometrial biopsy: from indications to instrumentation and techniques. A call to action. Minim. Invasive Ther. Allied Technol. 2021, 30, 251–262. [CrossRef]

- Di Spiezio Sardo, A.; Saccone, G.; Carugno, J.; Pacheco, L. A.; Zizolfi, B.; Haimovich, S.; Clark, T.J. Endometrial biopsy under direct hysteroscopic visualisation versus blind endometrial sampling for the diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Facts Views Vis. Obgyn. 2022, 14, 103-110. [CrossRef]

- Vitale, S. G.; Buzzaccarini, G.; Riemma, G.; Pacheco, L. A.; Di Spiezio Sardo, A.; Carugno, J.; Chiantera, V.; Török, P.; Noventa, M.; Haimovich, S.; De Franciscis, P.; Perez-Medina, T.; Angioni, S.; Laganà, A. S. Endometrial biopsy: Indications, techniques and recommendations. An evidence-based guideline for clinical practice. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2023, 52, 102588. [CrossRef]

- Vitale, S. G.; Della Corte, L.; Ciebiera, M.; Carugno, J.; Riemma, G.; Lasmar, R. B.; Lasmar, B. P.; Kahramanoglu, I.; Urman, B.; Mikuš, M.; De Angelis, C.; Török, P.; Angioni, S. Hysteroscopic Endometrial Ablation: From Indications to Instrumentation and Techniques-A Call to Action. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 339. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, G.J.; Monteiro, B.M.; Viana, R.B.; da Silva, A.O.A.; Monteiro, F. D. O.; Teixeira, P. P. M. New method of video-assisted vaginoscopy in Nellore heifers. Vet. Med. Sci. 2023, 9, 2781-2785. [CrossRef]

- Vall, E.; Blanchard, M.; Sib, O. et al. Standardized body condition scoring system for tropical farm animals (large ruminants, small ruminants, and equines). Trop. Anim. Health. Prod. 2025, 57, 106. [CrossRef]

- Kershaw, M.C.; Khalid, M.; McGowan, M.R.; Ingram, K.; Leethongdee, S.; Wax, G.; Scaramuzzi, R.J. The anatomy of the sheep cervix and its influence on the transcervical passage of an inseminating pipette into the uterine lumen. Theriogenology 2005, 64, 1225-1235. [CrossRef]

- Taqueda, G.S.; Azevedo, H.C.; Santos, E.M.; Matos, J.E.; Bittencourt, R.F.; Bicudo, S.D. Influence of anatomical and technical aspects on fertility rate based on sheep transcervical artificial insemination performance. ARS Vet. 2011, 27, 127-133. [CrossRef]

- Millar, H.R.; Simpson, J.G.; Stalker, A.L. An evaluation of the heat precipitation method for plasma fibrinogen estimation. J. Clin. Pathol. 1971, 24, 827-830. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591-611. [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, W.H.; Wallis, W.A. Use of Ranks in One-Criterion Variance Analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952, 47, 583-621. [CrossRef]

- Dunn, O.J. Multiple Comparisons Using Rank Sums. Technometrics 1964, 6, 241-252. [CrossRef]

- Tukey, J.W. Comparing Individual Means in the Analysis of Variance. Biometrics 1949, 5, 99-114. [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K. On the criterion that a given system of deviations from the probable in the case of a correlated system of variables is such that it can be reasonably supposed to have arisen from random sampling. Philos. Mag. 1900, 50, 157-175. [CrossRef]

- Colagross-Schouten, A.; Allison, D.; Brent, L.; Lissner, E. Successful Use of Endoscopy for Transcervical Cannulation Procedures in the Goat. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2014, 49, 909-912. [CrossRef]

- McCool, K.E.; Marks, S.L.; Hawkins, E.C. Endoscopy Training in Small Animal Internal Medicine: A Survey of Residency Training Programs in North America. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2022, 49, 515-523. [CrossRef]

- Önder, N.T.; Batı, Y.U.; Gökdemir, T.; Kılıç, M.C.; Şahin, O.; Öğün, M.; Öztürkler, Y. Oxidative response of sheep to transcervical applications. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2023, 58, 877-881. [CrossRef]

- Souza-Fabjan, J.M.G.; Oliveira, M.E.F.; Guimarães, M.P.P.; Brandão, F.Z.; Bartlewski, P.M.; Fonseca, J.F. Non-surgical artificial insemination and embryo recovery as safe tools for genetic preservation in small ruminants. Animal 2023, 17, 100787. [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.C. Essentials of veterinary hematology; Lea & Febiger: Philadelphia, USA, 1993; 417p.

- Sabes, A.F.; Girardi, A.M.; Fagliari, J.J.; de Oliveira, J.A.; Marques, L.C. Serum proteinogram in sheep with acute ruminal lactic acidosis. Int. J. Vet. Sci. Med. 2017, 5, 35-40. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.C.; Haas, C.S.; Ferreira, C.E.R.; Goularte, K.L.; Pegoraro, L.M.C.; Gasperin, B.G.; Vieira, A.D. Inflammatory markers in ewes submitted to surgical or transcervical embryo collection. Small Rumin. Res. 2018, 158, 15-18. [CrossRef]

- Önder, N.T.; Gökdemir, T.; Kilic, M.C.; Şahin, O.; Demir, M.C.; Yildiz, S.; Öztürkler, Y. A novel “Onder Speculum” to visualize and retract the cervix during transcervical procedures in small ruminants. Vet. Fak. Derg. 2024, 30, 101-106.

- Duarte, G.S.; Galindo, D.J.; Baldini, M.H.M.; da Fonseca, J.F.; Duarte, J.M.B.; Oliveira, M.E.F. Transcervical artificial insemination in the brown brocket deer (Subulo gouazoubira): a promising method for assisted reproduction in deer. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17369. [CrossRef]

- Masoudi, R.; Shahneh, A.Z.; Towhidi, A.; Kohram, H.; Akbarisharif, A.; Sharafi, M. Fertility response of artificial insemination methods in sheep with fresh and frozen-thawed semen. Cryobiology 2017, 74, 77-80. [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.A.M.; Teixeira, P.P.M.; Coutinho, L.N.; Gutierrez, R.R.; Macente, B.I.; Vicente, W.R.R.; Brun, M.V. Resection of vaginal neoplasms by video-vaginoscopy in bitches. Acta Sci. Vet. 2014, 42, 1-5.

- Franco, M.C.; dos Santos, J.F.; Maciel, T.A.; Duarte Neto, P.J.; Oliveira, D. Morphology of the cervix of Santa Ines adult sheep in luteal and folicular phases. Ciênc. Anim. Bras. 2014, 15, 495-501. [CrossRef]

- Moura, D.S.; Lourenço, T.T.; Moscardini, M.M.; Scott, C.; Fonseca, P.O.; Souza, F.F. Aspectos morfológicos da cérvice de ovelhas. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2011, 31, 33-38. [CrossRef]

- Rekha, A.; Zohara, B.F.; Bari, F.; Alam, M.G.S. Comparison of commercial Triladyl extender with a tris-fructose-egg-yolk extender on the quality of frozen semen and pregnancy rate after transcervical AI in Bangladeshi indigenous sheep (Ovis aries). Small Rumin. Res. 2016, 134, 39-43. [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.C.N.; Pereira, E.T.N.; Almeida, I.C.; Xavier, E.D.; Oliveira, D.C.F.; Almeida, A.C. Reproductive disorders and reconception of beef cows subjected to timed artificial insemination. Ciênc. Anim. Bras. 2022, 23, e70384. [CrossRef]

- Russi, L.S.; Costa-e-Silva, E.V.; Zúccari, C.E.S.N.; Recalde, C.S.; Cardoso, N.G. Impact of the quality of life of inseminators on the results of artificial insemination programs in beef cattle. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2010, 39, 1457-1463. [CrossRef]

- Purdy, P.H.; Spiller, S.F.; McGuire, E.; McGuire, K.; Koepke, K.; Lake, S.; Blackburn, H.D. Critical factors for non-surgical artificial insemination in sheep. Small Rumin. Res. 2020, 191, 106179.

- Teixeira, T.A.; da Fonseca, J.F.; de Souza-Fabjan, J.M.G.; de Rezende Carvalheira, L.; de Moura Fernandes, D.A.; Brandão, F.Z. Efficiency of different hormonal treatments for estrus synchronization in tropical Santa Inês sheep. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2016, 48, 545-551. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).