1. Introduction

In recent years, the use of endoscopy in the reproductive management of domestic carnivores has become more prevalent, with this technology now commonly found in veterinary clinics. Vaginal endoscopy is employed not only for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes but also for procedures such as artificial insemination. With advancements in technology, endoscopy capabilities are evolving, which requires ongoing evaluation of the field’s current status. Endoscopy presents numerous advantages over conventional surgical techniques, one of which is its non-invasive characteristic. To effectively incorporate endoscopy into small animal reproductive care, it is essential to have a thorough understanding of reproductive tract anatomy, proficiency in the procedure, and access to the proper equipment. [

11].

While pelvic examination, vaginal cytology, and transabdominal ultrasound are valuable tools for evaluating a female dog’s reproductive health, they are limited in their ability to assess the vaginal mucosa fully. Speculum examination, for example, typically only allows visualisation of the vaginal vault. In contrast, vaginal endoscopy provides a more comprehensive view, enabling a detailed evaluation of the entire vaginal canal. This method allows for the identification of various conditions and, in some cases, may offer additional treatment options. [

13]. Vaginoscopy is more sensitive than vaginal cytology for diagnosing clinical and subclinical post-partum endometritis.

Vaginoscopy is the preferred diagnostic method for a range of vaginal disorders and conditions, including congenital anomalies, neoplasia, and ectopic ureters [

12]. In cases of vulvar discharge or infertility, a vaginal examination may also reveal further information [

25]. In some species, such as dogs and sheep, vaginoscopy is also an effective tool for reproductive management, identifying oestrus stages, predicting other reproductive stages and facilitating transcervical insemination, which is recommended for insemination with frozen-thawed semen [

11]. Evaluating the vaginal mucosa during the oestrous cycle, in addition to utilising standardised tests, such as progesterone assay and vaginal cytology, can help determine the timing of ovulation and detect hormonal effects [

14]. Endoscopy offers a quick and comfortable means of examining a female dog’s vaginal tract. However, it is essential to thoroughly comprehend the reproductive system’s anatomy, the necessary equipment, and the ability to perform the technique to take advantage of the benefits of endoscopy in small animal reproduction. [

17]

2. Materials and Methods

The structure of the canine vagina is distinct and requires particular attention when doing endoscopic examinations. The urethral opening is situated on the underside, at the junction of the vestibule and vagina. To ensure optimal positioning, the endoscope should be inserted vertically along the dorsal vaginal wall while considering the anatomical constraints because it is essential to avoid any insertion into the fossa clitoris. The length of the vestibule, which can vary between species, typically ranges from 2 to 5 cm [

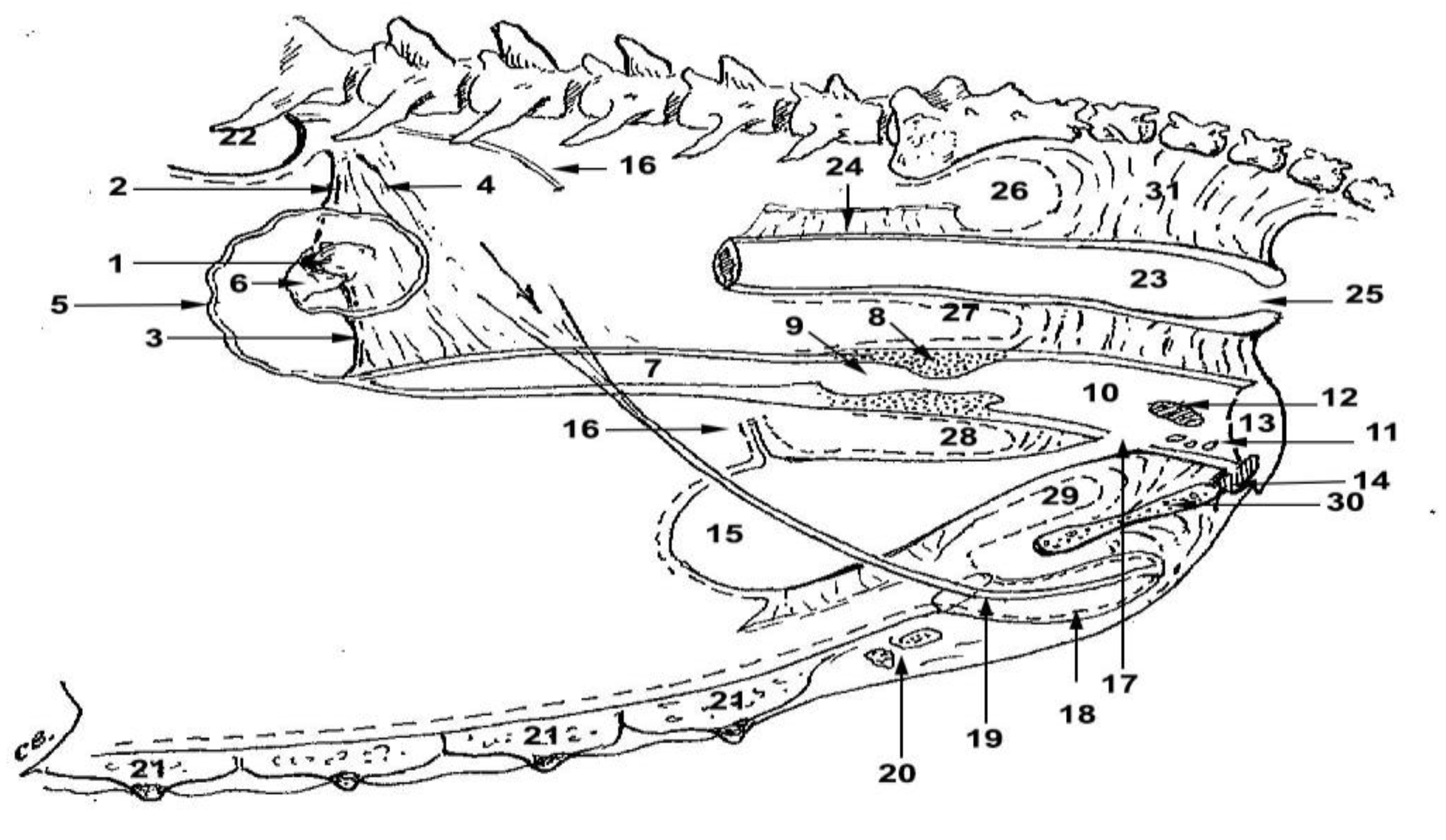

8]. Occasionally, a small portion of the hymen may be visible at the junction of the vestibule and vagina. The canine vagina is characterised by longitudinal mucosal folds, the appearance and prominence of which are heavily influenced by the hormonal status of the female dog. As the vagina approaches the abdominal cavity, its orientation shifts from vertical to horizontal. The entrance of the vagina is partially hidden by the labia minora, and its back ends in a cul-de-sac penetrated by the uterine cervix. The recess formed by the presence of the cervix is called the fornix. The diameter of the vaginal lumen in the cranial section is less than half that of the caudal region. At vaginoscopy, the caudal portion of the fold and the constrictions of the lateral and ventral vaginal walls give a distinct appearance, referred to as pseudocervix. The true vaginal portion of the cervix is cranial to the pseudocervix. This makes intrauterine cannulation difficult, also because the cervical canal is nearly perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the vagina and the uterine body. Also, the cervical fornix, located just above the tubercle, is the uppermost part of the vagina. The cervix is typically located at the third lumbar vertebra level. Endoscopy is initially performed using a vertical approach, transitioning to a horizontal approach once the pelvic floor is reached. To identify the opening, it is crucial to carefully examine the cervical tubercle from the anterior side, looking for any signs of blood or mucus discharge at the entrance, as shown in

Figure 1.

Legend: 1-ovary; 2-suspensory ligament of the ovary; 3-the ovary’s ligament (utero-ovarian); 4-mesoovary; 5-left oviduct; 6-infundibular; 7-left uterine horn; 8-cervix; 9-cervical canal; 10-vaginal vestibule; 11-minor vestibular glands; 12-vestibular bulbs; 13-vulva; 14-clitoris, 15-urinary bladder; 16-sectioned left ureter; 17-urethra; 18-external ostium of the urethra; 19-insertion on the bladder of the medial bladder ligament; 20-mammary lymph nodes (superficial inguinal); 21-mammary glands; 22-kidneys; 23-rectum; 24-insertion on the rectum of the mesorectum; 25-anus, 26-bottom of the sacrorectal sac; 27-bottom of rectogenital sac; 28-fundus of genitovesical sac; 29-fundus of the vesicopubic sac; 30-ischiopubic symphysis; 31-retroperitoneal connective tissue.

Performing vaginoscopy in dogs can be a straightforward and uncomplicated technique, typically including the use of a vaginal speculum or otoscope. Nevertheless, there are certain drawbacks associated with this particular approach, including the absence of vaginal distension and the restricted vision cranial to the cingulum. While the utilisation of pediatric proctoscopes enables the inflation of the distal reproductive tract using air, it presents challenges to sustaining distension during the biopsy procedure. Endoscopic vaginoscopy can be performed using either flexible or rigid endoscopes [

5]. Endoscopes with a camera at the tip of the scope provide better image quality than scopes with fiber optic viewing. Due to their relatively high cost and potential challenges in handling, video scopes may not be the most practical option. In this regard, rigid cystoscopes present a more cost-effective and manageable alternative. This technique provides veterinary practitioners with enhanced diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities for managing vestibulo-vaginal disorders in female canines. [

16].

In bitches, a rigid endoscope (Karl Storz Veterinary Endoscopy, Tuttlingen, Germany) with a cover and catheter port or working channel is more suitable for vaginal examination than a flexible endoscope. Rigid endoscopes can improve navigation within the vagina and allow flexible catheters and brushes to be inserted. Rigid endoscopes can be used for most dogs, regardless of size. In general, the endoscope needs to be 30 cm or longer to reach the cervix in medium to large dogs and small in diameter to pass through the cranial portion of the vagina in small and medium dogs. Most authors recommend an optical angle of 6° to 30° to better visualise the cervical opening [

27]. A 3.5 mm diameter extended urethra cystoscope is commonly used for the examination of vaginal and transcervical insemination (TCI- Karl Storz Extended Length Cysto-Urethroscope, Tuttlingen, Germany) [

22].

As a result, we recommend having accessible scopes of different sizes. The 18 cm long scope has a 2.7 mm diameter and a 14.5 Fr outer sheath. This scope is used to examine canines weighing less than 10 kg. If your budget permits only one scope, the authors suggest the 4 mm diameter cystoscope. It is 32 cm in length and has a 17 Fr outer sheath. A larger scope (3.5 mm 36.5 cm long with a 22 Fr sheath) is recommended for transcervical artificial insemination in large-breed dogs

Figure 2.

Rigid cystoscope viewing lenses are available in various camera angles. Most veterinary cystoscopes are equipped with a 30-degree upward-tilting lens. This angle offers an enhanced view of the lateral walls, but the tip may need to be lowered to gain a clearer perspective of structures directly in front of the scope. Typically, the procedures of vaginal examination and intrauterine insemination are generally well-tolerated by individuals without the need for anaesthesia. On average, these procedures may be conducted on female canines while positioned upright on a veterinary examination table. It may be appropriate to provide sedation under some circumstances, such as anestrus or limited lumen, an anxious female dog, or vestibulitis/vaginitis. An example of such protocol is DBK: Dexmetdetomidine1-2 μg/kg(Dexdomitor®, Orion Pharma, Espoo, Finland; Zoetis Inc) Butorphanol 0.2-0.3 mg/kg (Torbutrol®, Zoetis, USA) and Ketamine 1 mg/kg (Ketaset®, Zoetis, USA) administrated intramuscular. In some cases, general inhalation anaesthesia is required. For induction, the agent of choice is Propofol 1-3 mg/kg iv (PropoFlo®, Zoetis, USA), followed by endotracheal intubation and maintenance with Isoflurane (Isospire™, Dechra, Northwich, England), to reduce the risk of vaginal trauma or damage to equipment.

Vaginoscopy can be performed with the dog in either lateral or ventral recumbency; however, dorsal recumbency is also an effective positioning technique to prevent accidental faecal contamination from the rectum. This position allows the dog’s tail to rest below the clinician’s working field naturally. The dog’s pelvis is positioned at the distal end of the table, with the hind legs loosely secured in a frog-like posture (

Figure 3). A fenestrated drape covers the dog while exposing the vulva for the procedure.

Wearing sterile gloves, the veterinarian assembles the cystoscope and attaches the tubing for the irrigation fluid. To avoid the clitoris, the scope is initially guided with the tip pointing downward. Once inserted, the endoscope’s irrigation port or air valve is opened, allowing a sterile, warm, isotonic solution to distend the vestibule.

During catheterisation, the optics and light source size may limit the field of view. Additionally, mucus on the lens can obstruct visibility. A protective sleeve helps shield the lens from mucus and minimises potential damage to the optics from repeated use.

Urinary catheters can be used for transcervical insemination, mainly if the catheter tip is flexible. The catheter also facilitates exploration of the vagina during proestrus, when swollen vaginal folds may obstruct the view. The protruding catheter can then be used as a guide for the endoscope.

3. Results

Vaginoscopy in canines is a valuable procedure for the thorough evaluation of the vaginal tract, with numerous applications in both reproduction and therapeutic diagnostics.

By correlating the results from the literature with our findings, we have described the most commonly identified features in vaginoscopic examinations.

Vaginoscopic evaluation involves assessing the appearance of the vaginal wall, including the contours and profiles of the mucosal folds, the colour of the mucosa, and the presence of any fluids. Changes in these features are observed at different stages of the oestrous cycle.

The vestibular-vaginal junction is easily identified when the endoscope is inserted straight over the vulvar commissure. When the patient is in dorsal recumbency, the urethra is above the vestibular-vaginal junction [

1]. The urethra is evaluated for proliferative lesions, uroliths, ectopic ureters, inflammations, stenosis, and injuries to the mucous membrane.

The opening of the vestibular-vaginal junction is wider than the urethral opening. Before the insertion of the endoscope into the urinary tract, the area of the external opening of the urethra should be evaluated because the most frequent abnormalities that can be found in this area are inflammations and neoplasms. Endoscopic examination can reveal mucosal membrane irritation, bleeding, erosion, ulceration, and excessive tissue and adhesion proliferation, such as in granular inflammation of the urethra.

If the urinary tract is examined simultaneously, first, urethral and bladder examinations should be attempted. This order is recommended because the urinary tract has fewer pathogenic microbes than the vagina [

20].

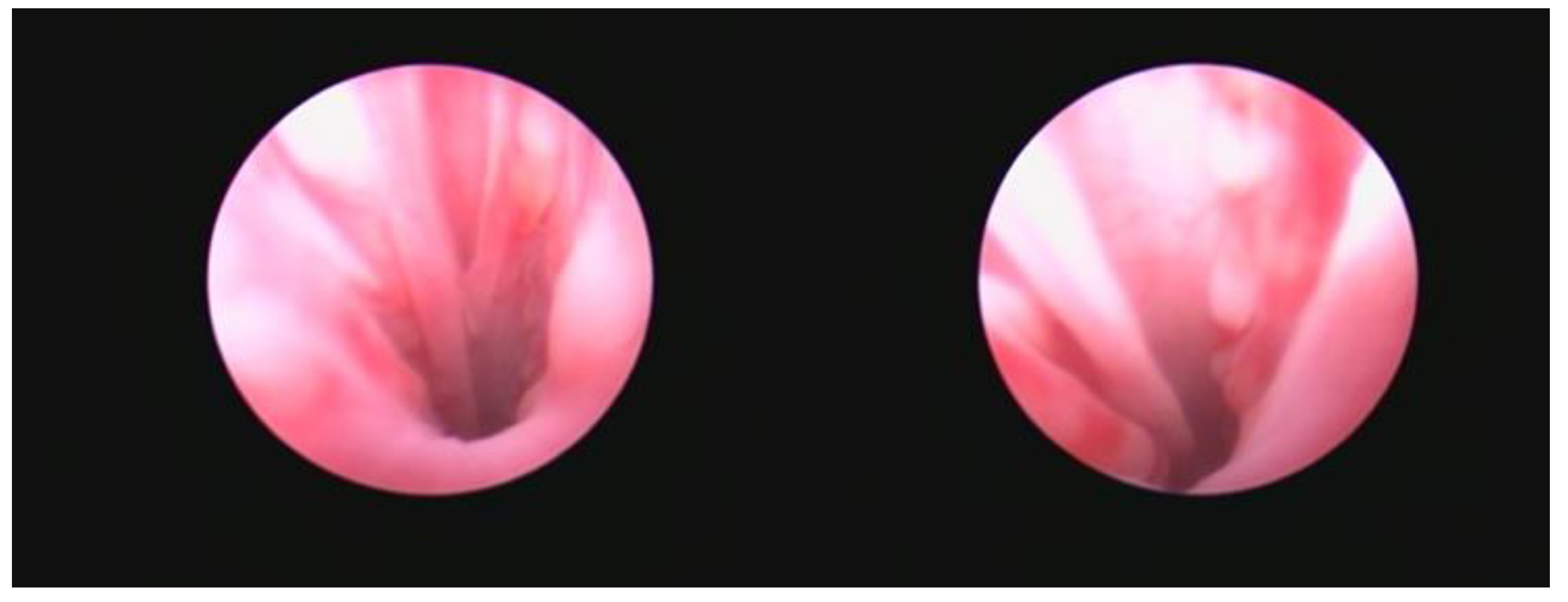

During urethrocystoscopy, attention should be directed to the appearance of the mucous membrane, its colour and surface characteristics, and the presence of erosion, lesions, and ulceration should be evaluated,

Figure 4 [

4]. Before inserting the endoscope into the urinary tract, the area of the external urethral orifice should be examined. Inflammation and neoplasms are the most frequent abnormalities observed in this region.

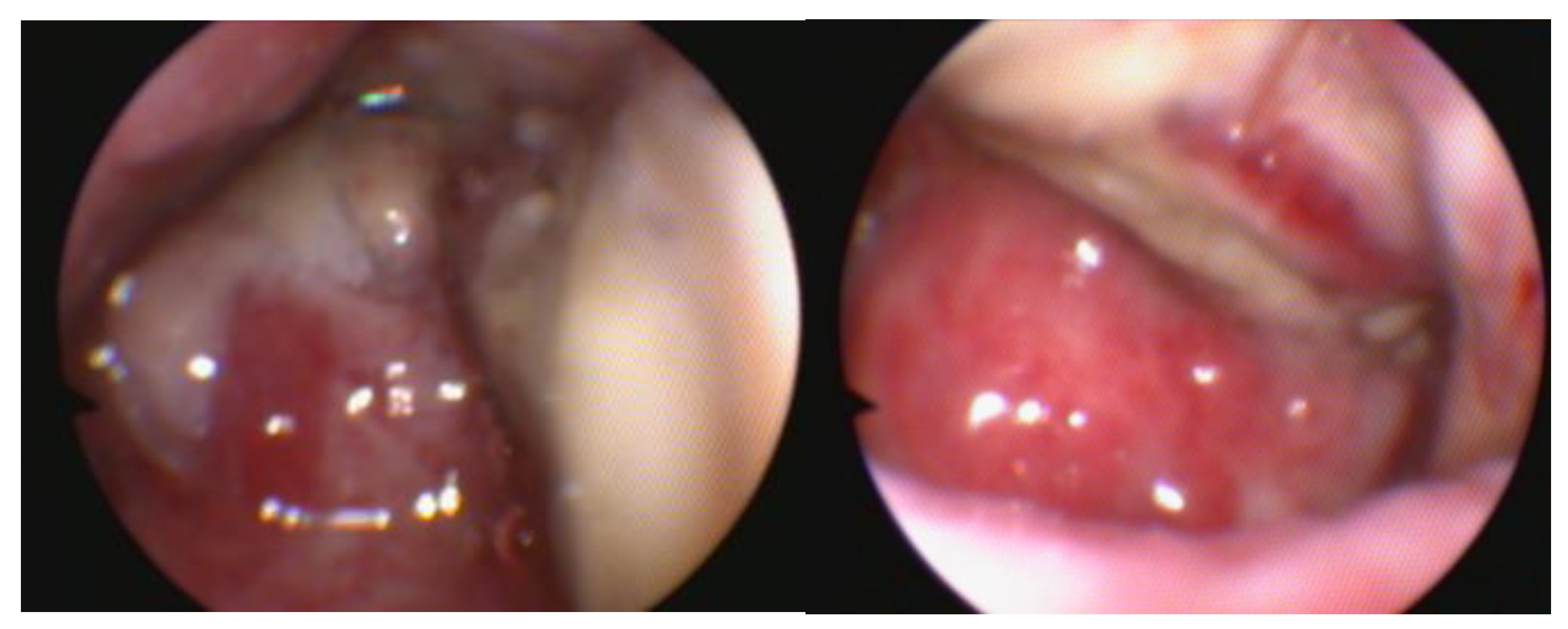

When examined, the vestibular-vaginal junction should be a single, smooth, continuous, symmetrical, and distensible opening. Asymmetry suggests the existence of tumours, infections, or injuries. A narrower, barely distensible aperture characterises a vestibular-vaginal stricture. A smaller, minimally extensible opening contains vestibular constriction. If the vestibular-vaginal junction divides into two or more openings, consider a diagnosis of vaginal septum or vaginal duplication

Figure 5 [

14].

The vestibule is examined for foreign bodies, mucosal lesions, hyperemia, blood, and anatomical abnormalities [

12]. Besides occasional foreign bodies and mucous follicles, abnormalities in the vestibule are rarely found; also, vaginal leakage may be seen in young dogs with urinary incontinence of ectopic ureters [

2]. Urinary incontinence is an increasing problem in young female dogs, sometimes caused by a congenital abnormality called ureteral ectopy. This condition occurs when one or both ureteral openings are located further down from the bladder’s trigone. In the case of ectopic ureters, a basin shape of the ureter and its extension can be observed. Urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence is the primary reported cause of urinary incontinence in adult bitches. Ectopic ureters in dogs are a congenital condition in which the ureters, the thin tubes meant for connecting the kidneys to the bladder, bypass the bladder and instead connect directly to the urethra or vagina. Endoscopy is considered a sensitive method for detecting these abnormal or atypical openings (

Figure 6). A cystoscopy is a valuable procedure for evaluating the image inside the bladder. It is beneficial to examine the vesical trigone, the ureteric orifices and the internal urethral orifice [

10].

Endoscopy allows the examination of vaginal tumours; although vaginal neoplasia is uncommon in the bitch and the majority of tumours are benign [

26], it can produce significant clinical symptoms [

3]. Diagnosing bladder cancer can be difficult and is based on history, physical exam findings, and diagnostic imaging; cytology or histology are generally utilised for confirmation [

12]. However, since endoscopy is the only method to distinguish between benign and malignant lesions, a biopsy should be obtained for histopathological analysis, and the nature of the modifications (the degree, appearance, and grade of urethral stenosis) should be assessed when a neoplastic process in the urethra is suspected [

9]. Safe and effective resection of pedunculated tumours is possible using a polypectomy snare and electric current [

23]. Studies have reported examples of adequate endoscopic excision of vaginal neoplasia, without performing an episiotomy or laparotomy, were resection of the vaginal tumours [

28]. Unfortunately, large tumours can make it impossible to enter a rigid endoscope, in which case a flexible 7.5 Fr/2.5-to 2.8-mm fiberoptic urethroscope is ideal to pass by the vaginal mass and examine it properly [

21],

Figure 7.

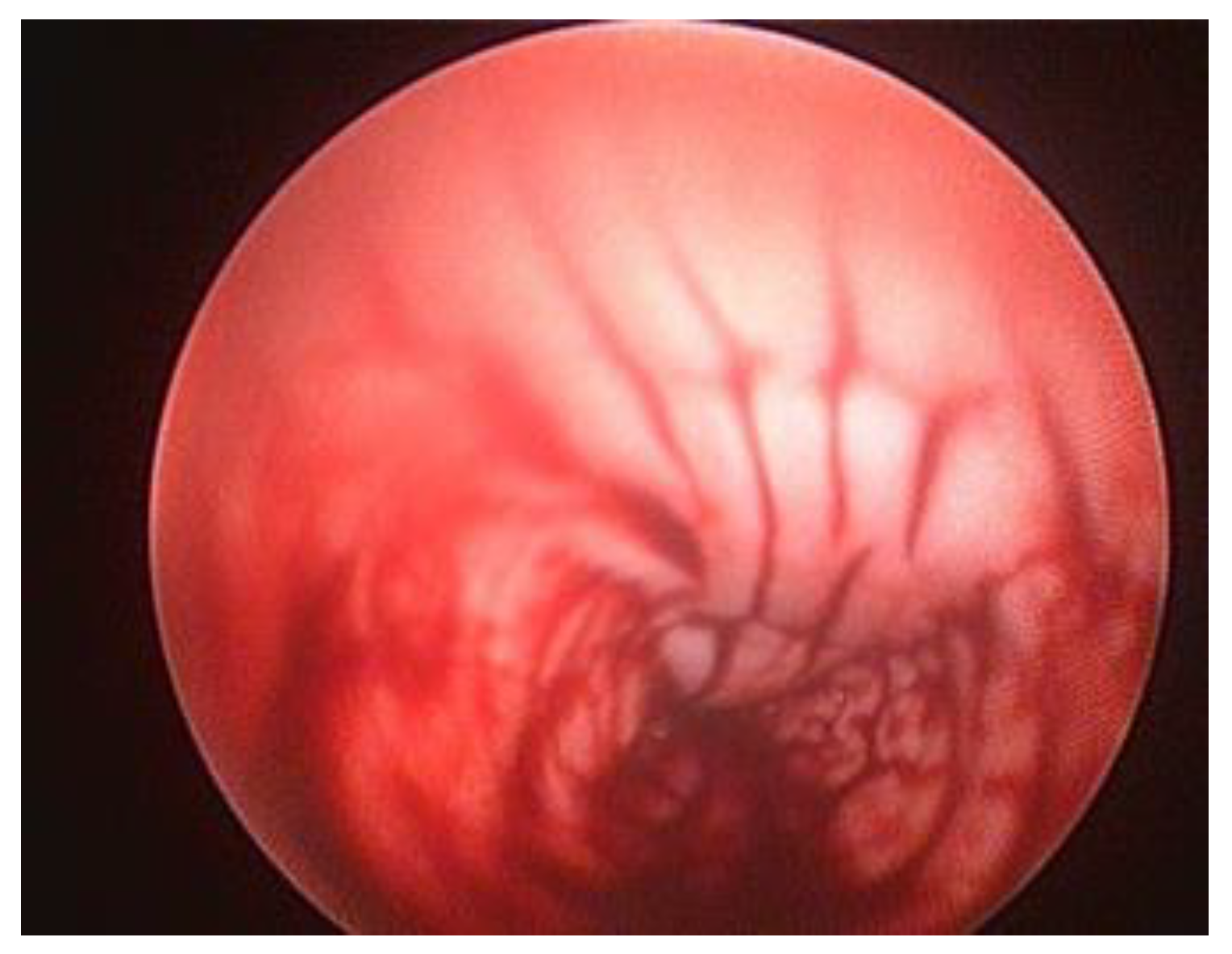

Regular evaluation of the bitch throughout the oestrous cycle is essential for determining the optimal days for mating or insemination with fresh, refrigerated, or frozen sperm. Vaginoscopy can aid in timing ovulation by assessing changes in the form, colour, and secretions of the mucosa, which correlate with hormonal variations, particularly during proestrus and estrus when the appearance of the vaginal mucosa and cervix changes (

Figure 8).

Transcervical Catheterisation

The utilisation of endoscopic-assisted TCI(Karl Storz Extended Length Cysto-Urethroscope, Tuttlingen, Germany) or transcervical catheterisation enables the facilitation of intrauterine insemination in canines of various sizes, a practice that is highly suggested mainly when using frozen semen [

17]. The Transcervical Insemination TCI method is used to deposit the semen through the cervix into the uterus using a catheter. The technique described presents a non-invasive alternative to surgical insemination, with the need for anaesthesia of the female dog being rare [

19].

In the author’s experiences, most endoscope-assisted TCIs are performed with the patient standing on an adjustable height table that effectively accommodates dogs of different sizes. While most endoscope-assisted TCI procedures are carried out with the operator standing, if TCI is challenging, the procedure may be more successful if it is performed while seated on an adjustable stool. It appears that, in certain instances, a subtle difference in orientation is beneficial.

The recommended approach is to strictly progress the scope’s range when its trajectory is observed on the video display, avoiding direct visual examination of the scope or the canine subject. This will prevent any unexpected trauma to the vagina. Transcervical insemination scope is occasionally difficult to navigate beyond the cranial vagina (approximately the level of the pubis). The authors have not yet developed a reliable method for advancing the scope. The only options available to increase the insufflation of the vagina are to increase the pressure on the endoscope and rotate the scope to adjust the field of view. Afterwards, pass the endoscope through the middle of the lumen without pushing or inserting it into the vaginal wall. Occasionally, it can be helpful to introduce an insemination catheter (TC Cannula, Minitube, Tiefenbach, Germany) to direct the tip of the endoscope [

15]. Catheters are more flexible than rigid endoscopes, making them easier to insert. The endoscope insertion demands a careful and deliberate approach, with the instrument being gently advanced under visual control, guided by the medial fold. If the neck opening is situated near the cervical tubercle, the endoscope must be withdrawn by a few centimeters before being reinserted on the appropriate side of the vaginal fold. This manoeuvre ensures the endoscope is adequately positioned close to the opening [

29]. Following this, a 4-5CH catheter is slowly, carefully advanced and inserted into the neck opening. The catheter must be slightly rotated and slowly advanced through the cervical canal to reach the uterine cavity [

13].

Lesions in the vaginal wall can be examined in more detail by rotating and changing the angle of the endoscope once the desired target is reached [

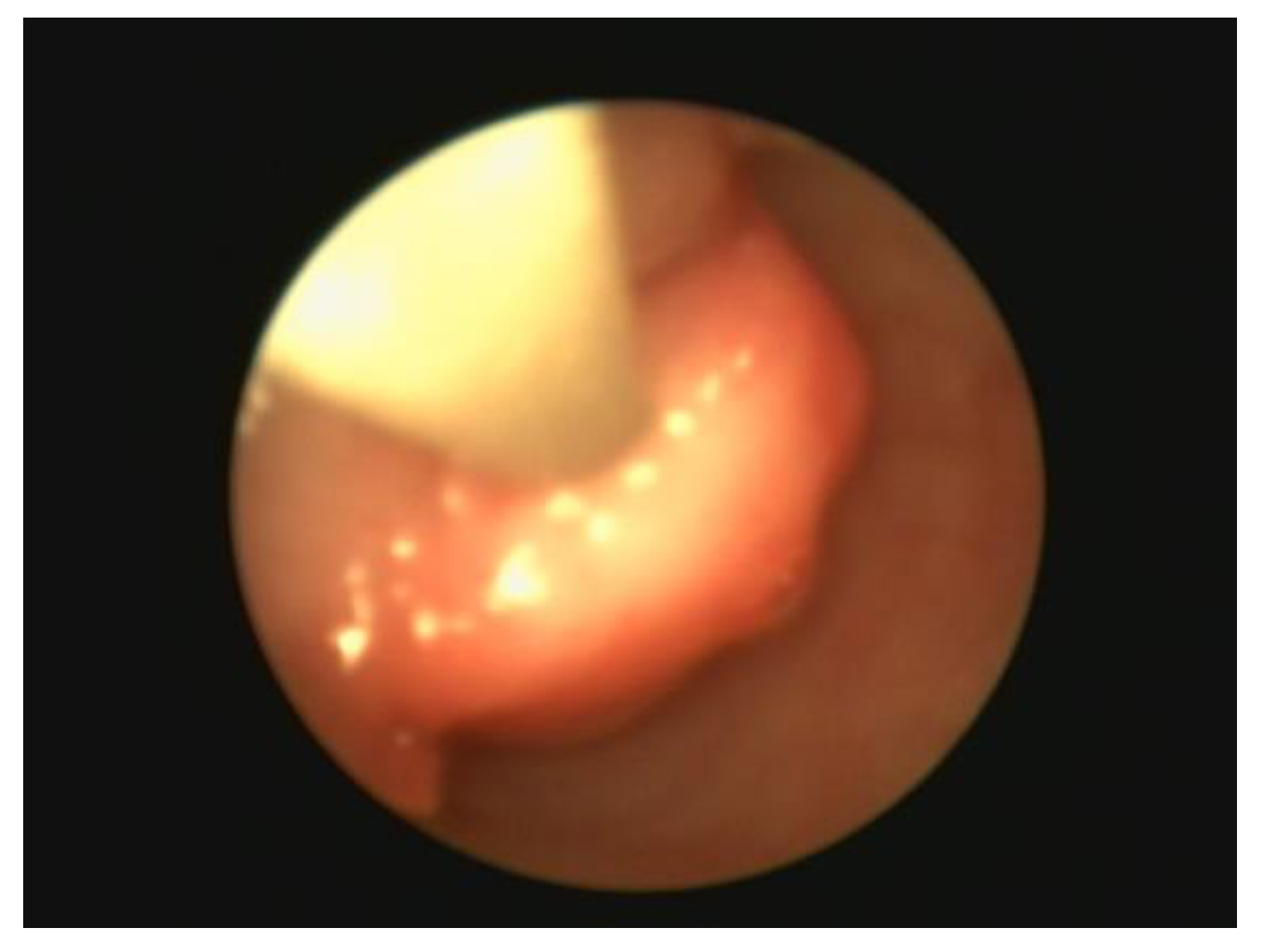

18]. Once the endoscope reaches the cervix, it cannot be advanced further (

Figure 9).

Upon completion of the examination, there is no requirement for the evacuation of fluid or air from the vaginal cavity as it will naturally disperse without external intervention. In cases when there is an accumulation of excessive fluid within the urinary tract, it is recommended to alleviate this condition by using either a cystoscope or manual expression of the bladder.

4. Conclusions

Endoscopic vaginal endoscopy is a highly effective and minimally invasive diagnostic technique that provides essential information about the stage of the estrus cycle, the source of vulvar discharge, the kind and size of vaginal tumours, the presence of polyps, and any abnormalities or deformities. Although this method offers advantages, it is limited by two significant constraints: the exorbitant expense of the required equipment and the necessity for specialised training.

Acquiring expertise in endoscopic transcervical procedures for the female dog may be considered a formidable challenge; however, this obstacle can be surmounted with perseverance and repetition. Despite the considerable financial investment necessary to acquire endoscopic instrumentation, it is ultimately justified through its numerous applications in various veterinary medicine sectors, making it a highly appealing proposition.

The occurrence and nature of complications following endoscopic examination of the reproductive system are influenced by the examined animal’s size, the equipment utilised, and the examiner’s expertise. Common complications include urethral or urinary bladder perforation, typically resulting from the use of inappropriately sized endoscopes; blood in urine due to damage inflicted on the inflamed urethral or urinary bladder mucosa; and urinary tract infections, which may occur as a result of inadequate disinfection of endoscopic equipment and subsequent bacterial transfer from the urethra to the urinary bladder. To avoid injury and damage to the vaginal wall, it is crucial to progress the endoscope carefully. If the dog displays defensive motions, it is recommended to delay the inspection until a more effective form of restraint is established. Moreover, an excessive amount of air and violent approaches can cause damage to the structure of the body and lead to rupture of the bladder or vagina. With skilled expertise and a thorough understanding of potential challenges, one can prevent numerous pitfalls and effectively handle others.

Vaginoscopy serves as a reliable and effective diagnostic method for identifying diseases of the urethra and urinary bladder. This technique allows for direct visualisation of these organs, enabling the detection of pathological changes in the mucous membrane. Furthermore, when urethrocystoscopy is conducted using an endoscope equipped with an instrument channel, obtaining samples for additional testing, such as histopathological analysis, becomes possible. This capability enhances the accuracy of diagnosis, subsequently influencing treatment strategies and prognosis.

After completing the treatment, it is important to thoroughly inspect the vaginal cavity for any indications of injury while delicately retracting the endoscope.

The endoscope should not be regarded as a procedure that is limited to specific cases, such as artificial insemination. Instead, it should be employed in all appropriate situations to enhance the experience and expertise.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, D.T and C.M..; endoscopic examinations, C.M. and D.T.; writing—original draft preparation C.M..; writing—review and editing C.M.and D.T.; visualisation C.M.; supervision D...; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

“This research received no external funding”.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of Dr Turcu Maria Roxana in providing anaesthesia for the endoscopic examinations.

Conflicts of Interest

state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”.

References

- Arlt, S.P., Rohne, J., Ebert, A.D., and Heuwieser, W. (2012). Endoscopic resection of a vaginal septum in a bitch and observation of septa in two related bitches. N Z Vet J 60: 258–260. [CrossRef]

- Brearley MJ, Cooper JE: The diagnosis of bladder disease in dogs by cystoscopy. J Small Anim Pract 28:75-85,.

- Christensen, B., Schlafer, D., Agnew, D. et al. (2012). Diagnostic value of transcervical endometrial biopsies in domestic dogs compared with full-thickness uterine sections. Reprod Domest Anim 47: 342–346. [CrossRef]

- Colaço, B., Dos Anjos Pires, M., and Payan-Carreira, R. (2012). Congenital aplasia of the uterine-vaginal segment in dogs. In: A Bird’s Eye View of Veterinary Medicine (ed. C.C. Perez-Marin), 165–178. Croatia: InTech.

- Davidson, A. and Eilts, B. (2006). Advanced small animal reproductive techniques. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 42: 10–17.

- Fontbonne, A. (2010). Approaching the endoscopic vaginal insemination. Why use this kind of diagnostic investigation? Proceedings of International SCIVAC Congress, Rimini, Italy (28–30 May 2010).

- Gregory, S.P., Holt, P.E., Parkinson, T.J., and Wathes, C.M. (1999). Vaginal position and length in the bitch: relationship to spaying and urinary incontinence. J. Small Anim. Pract. 40: 180–184. [CrossRef]

- Günzel-Apel, A.R., Wilke, M., Aupperle, H., and Schoon, H.A. (2001). Development of a technique for transcervical collection of uterine tissue in bitches. J. Reprod. Fertil. Suppl. (suppl. 57): 61–65.

- Hotston-Moore, A. and England, G.C.W. (2008). Rigid endoscopy: urethrocystoscopy and vaginoscopy. In: Manual of Canine and Feline Endoscopy and Endosurgery (eds. P. Lhermette and D. Sobel), 142–115. Cheltenham: British Small Animal Veterinary Association.

- Jody P. Lulich (2006). Endoscopic vaginoscopy in the dog, 66(3), 0–591. [CrossRef]

- 11. Kao S, Barger A, Garrett LD. Vaginal swab cytology as a diagnostic tool for neoplasia of the lower urinary tract in 5 dogs. Can Vet J. 2022 Dec;63(12):1221-1225. PMID: 36467378; PMCID: PMC9648476.

- 1, 12. Kassem Houshaimy, Dorin Țogoe, Tiberiu Constantin, Micșa Cătălin, Alexandru Șonea, „Preliminary Study Regarding the Additional Effect of Adding Antioxidants on Bull Frozen Semen” Agriculture for Life, Life for Agriculture” Conference Proceedings Vol 1, Issue 1, pages 440-444.

- Kustritz, M. R. (2011). Vaginoscopy. Nephrology and Urology of Small Animals, 188-191.

- Kustritz, M.V.R. (2006). Collection of tissue and culture samples from the canine reproductive tract. Theriogenology 66 (3): 567–574.

- Kyles, A. E., Vaden, S., Hardie, E. M., & Stone, E. A. (1996). Vestibulovaginal stenosis in dogs: 18 cases (1987–1995). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 209(11), 1889-1893.

- Lévy, X. (2016). Videovaginoscopy of the canine vagina. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 51: 31–36. [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, F.E.F. (1983). The normal endoscopic appearance of the caudal reproductive tract of the cyclic and non-cyclic bitch: post-uterine endoscopy. J. Small Anim. Pract. 24: 1–15.

- Lopate, C. (2012). Transcervical endoscopic procedures in the bitch. Clin. Theriogenol. 4: 213–224.

- Lulich, J.P. (2006). Endoscopic vaginoscopy in the dog. Theriogenology 66: 588–591.

- Maenhoudt C, N. R. dos Santos (2021). Veterinary Endoscopy for the Small Animal Practitioner 363–381. [CrossRef]

- 21. Mancuso G, Midiri A, Gerace E, Marra M, Zummo S, Biondo C. Urinary Tract Infections: The Current Scenario and Future Prospects. Pathogens. 2023 Apr 20;12(4):623. PMID: 37111509; PMCID: PMC10145414. [CrossRef]

- Mason, S. (2017). A retrospective clinical study of endoscopic-assisted transcervical insemination in the bitch with frozen–thawed dog semen. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 52: 275–280. [CrossRef]

- Micșa Cătălin, Dorin Țogoe, Gina Gîrdan, Maria Roxanaturcu, Cristina Preda, Andrei Tanase., Intravesical Administration Of Cytostatic In A Dog With Urinary Bladder Carcinoma - Case Study”. Scientific Works. Series C. Veterinary Medicine, Vol. LXVI, Issue 2 (2020), Issn 2067-3663 Pages 46-52.

- Moore, A. H., & England, G. (2008). Rigid endoscopy: urethrocystoscopy and vaginoscopy. In BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Endoscopy and Endosurgery (pp. 142-157). BSAVA Library.

- Silva, M. A. M., Teixeira, P. P. M., Coutinho, L. N., Gutierrez, R. R., Macente, B. I., Vicente, W. R. R., ... & Brun, M. V. (2014). Resection of vaginal neoplasms by video-vaginoscopy in bitches.

- Soderberg, S.F. (1986). Vaginal disorders. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 16 (3): 543–559.

- Verin R, Cian F, Stewart J, et al. Canine Clitoral Carcinoma: A Clinical, Cytologic, Histopathologic, Immunohistochemical, and Ultrastructural Study. Veterinary Pathology. 2018;55(4):501-509. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K. Y., Samii, V. F., Chew, D. J., McLoughlin, M. A., DiBartola, S. P., Masty, J., & Lehman, A. M. (2006). Vestibular, vaginal, and urethral relations in spayed dogs with and without lower urinary tract signs. Journal of veterinary internal medicine, 20(5), 1065-1073.

- Whitler, W. (2023). Canine transcervical insemination: history and technique. Clinical Theriogenology 15. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.S. (2001). Transcervical Insemination Techniques in the Bitch. Veterinary Clinics of North America Small Animal Practice 31(2):291-304. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.S. (2003). Endoscopic transcervical insemination in the bitch. In: Recent Advances in Small Animal Reproduction (eds. P.W. Concannon, G. England, J. Verstegen III and C. Linde-Forsberg). Ithaca, New York: International Veterinary Information Service [A1232.1203] www.ivis.org.

- Yamamoto, K., Kitai, M., Yamamoto, K., Sakuma, T., Nagao, S., & Yamaguchi, S. (2021). Successful endoscopic treatment for high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia with gross lesions of the vagina. Gynaecology and Minimally Invasive Therapy, 10(2), 124-126.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).