Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

17 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

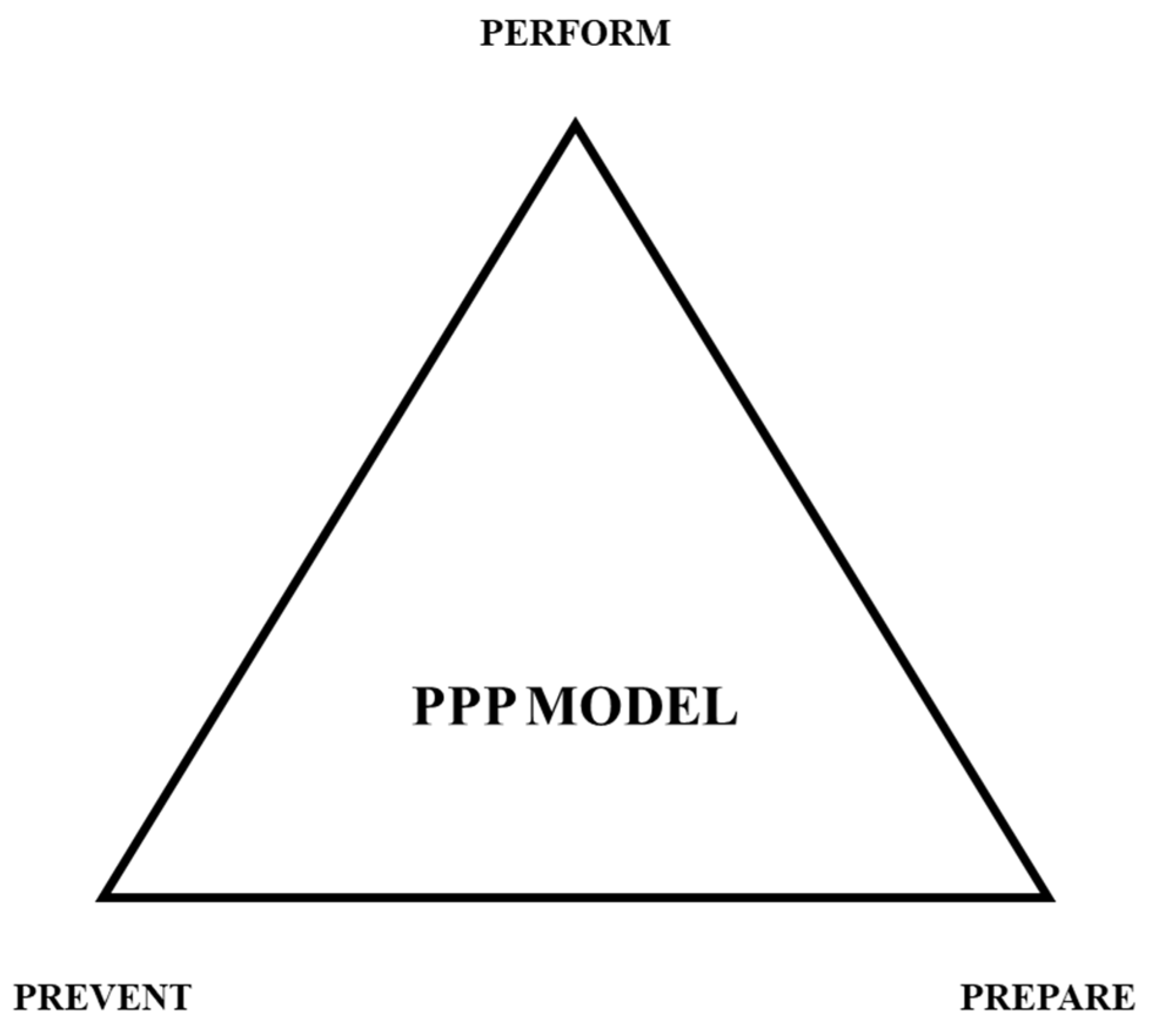

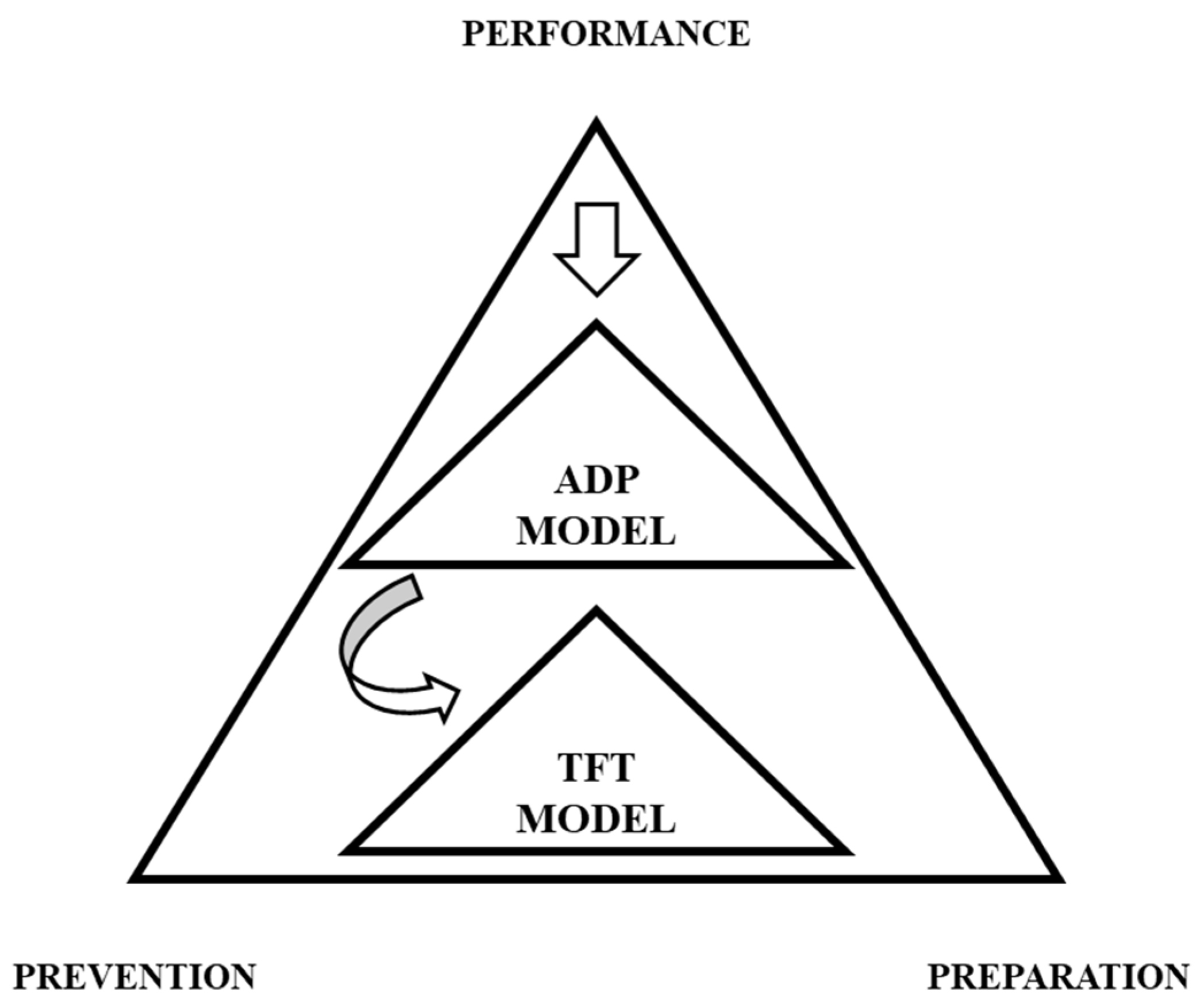

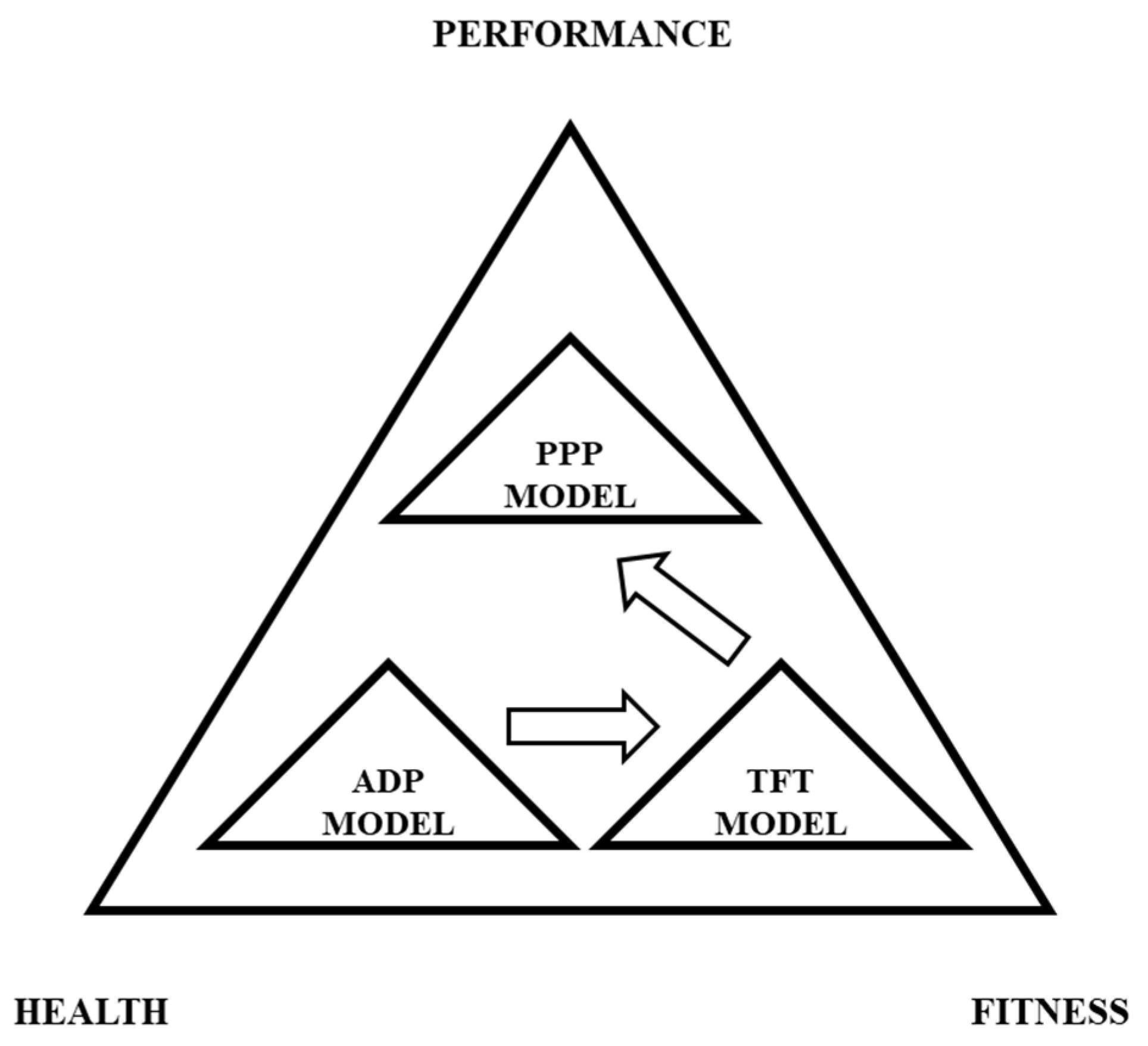

The Three Components of the PPP Model

Prevent

Prepare

Perform

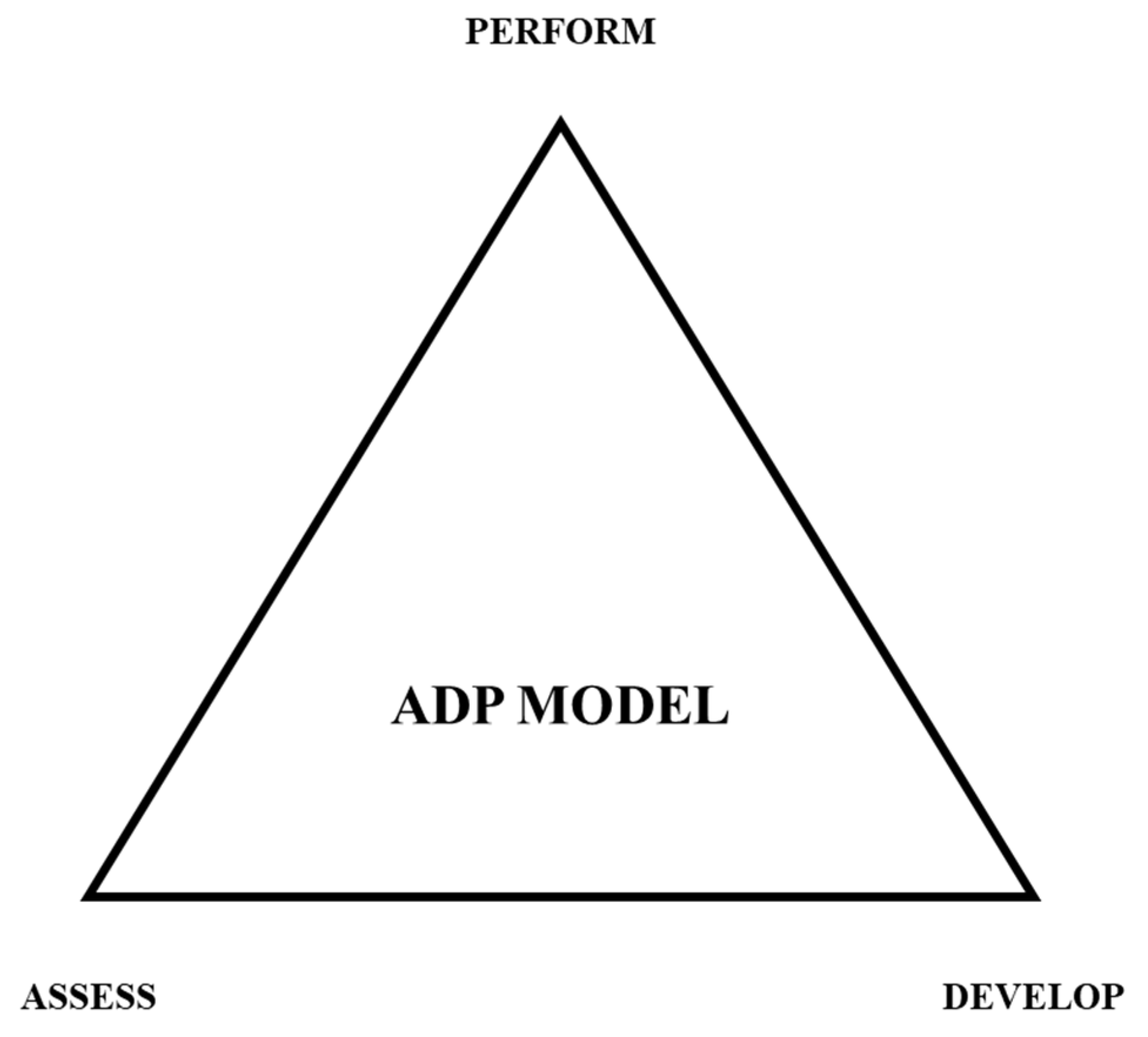

The Three Components of the ADP Model

Assess

Develop

Perform

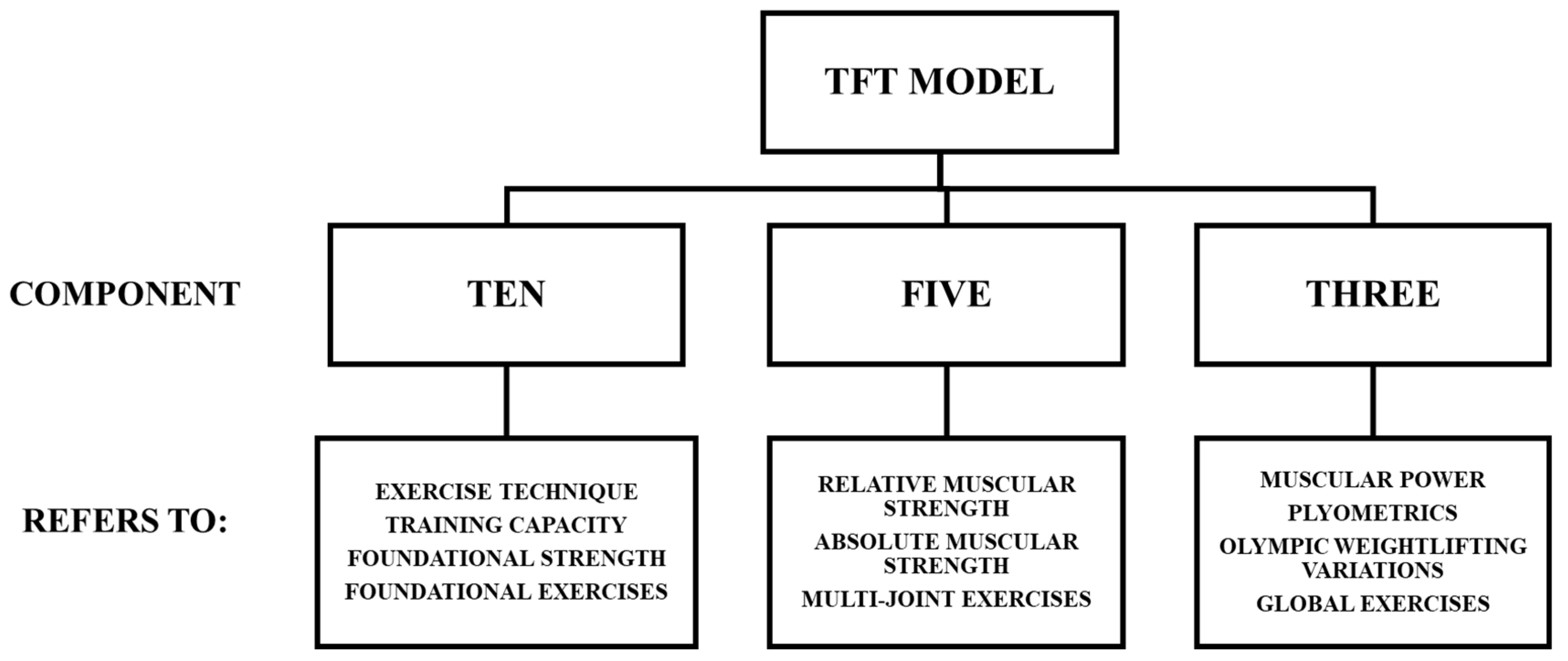

The Three Components of the TFT Model

Ten

- Decreased body fat

- Improved metabolic alterations

- Improvements in strength-endurance and power-endurance

- Substantial increases testosterone and growth hormone concentrations postexercise

- Increased resting testosterone-cortisol ratio

- Adequately develops a physiological foundation for further, more specific resistance training

- Squat

- Step

- Hinge

- Lunge

- Push

- Pull

- Carry

Five

- Barbell back squat

- Barbell front squat

- Barbell bench press

- Barbell incline bench press

- Barbell overhead press

- Barbell deadlift

- Trap bar deadlift

Three

- Landing

- Jumping

- Throwing

- Clean

- Jerk

- Snatch

Using the TFT Model to Guide Practice

| Emphasis | GPP | SPP | CP |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 10-repetition range | 5-repetition range | 3-repetition |

| 2. | 5-repetition range | 3-repetition | 5-repetition range |

| 3. | 3-repetition | 10-repetition range | 10-repetition range |

| Exercise Order | Ten | Five | Three |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Incline pushup | Barbell back squat | Jump landing technique |

| 2. | Kettlebell goblet squat | Incline dumbbell chest press | Depth drop |

| 3. | Inverted row | Dumbbell row | Box jump |

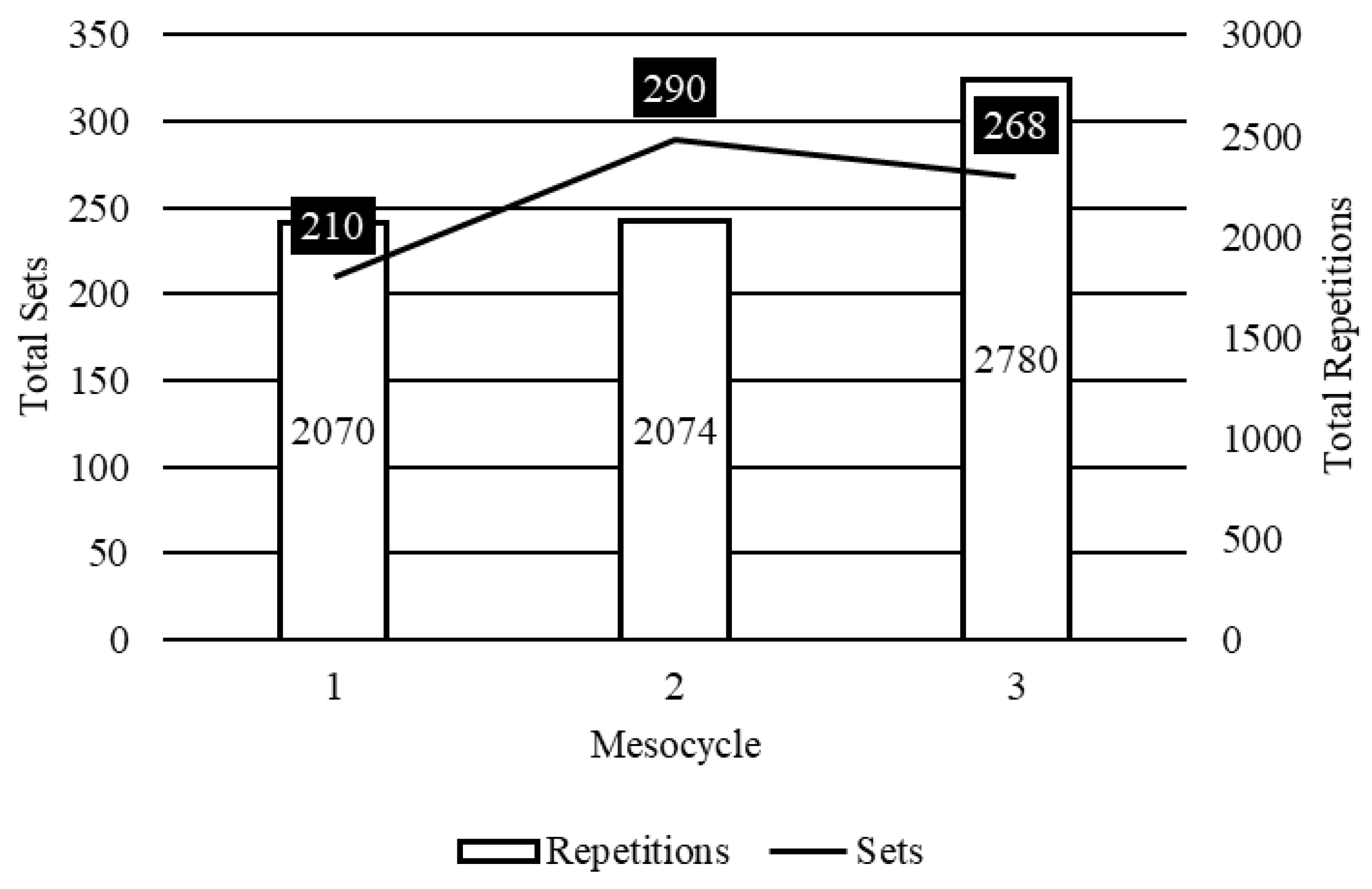

| Mesocycle | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sets | 210 | 290 | 268 |

| % change | 38.10% | -7.59% | |

| Repetitions | 2070 | 2074 | 2780 |

| %change | 0.19% | 34.04% | |

| Repetitions/Set | 9.86 | 7.15 | 10.37 |

| %change Sessions/Day |

-27.45% | 45.04% | |

| Sessions/Day | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Days/Week | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Intensity-cycle | 3/1 | 3/1 | 3/1 |

| Mesocycle | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Sets | 210 | 290 | 268 |

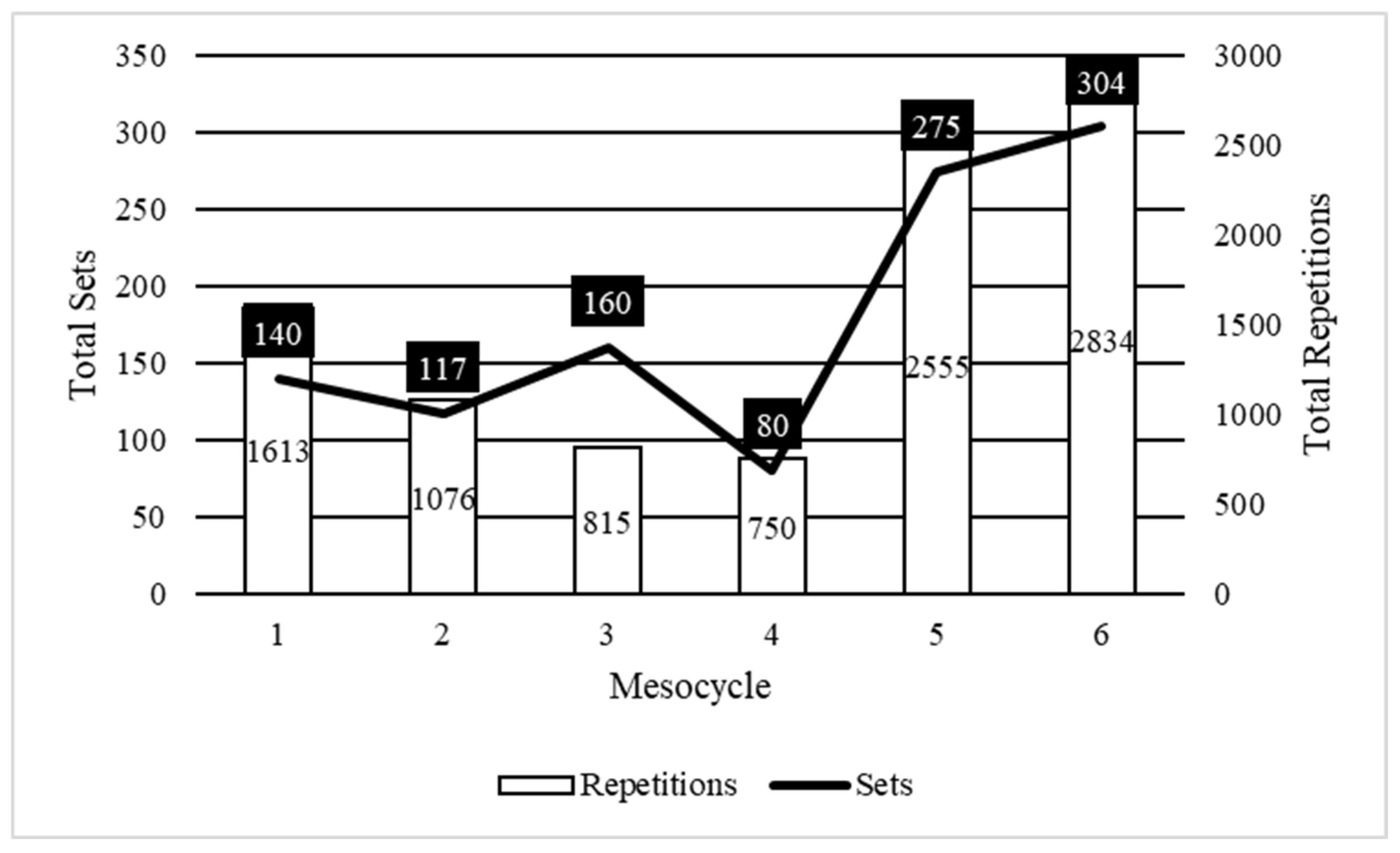

| Mesocycle | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4. | 5. | 6. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sets | 140 | 117 | 160 | 80 | 275 | 304 |

| % change | -16.43% | 36.75% | -50.00% | 243.75% | 10.55% | |

| Repetitions | 1613 | 1076 | 815 | 750 | 2555 | 2834 |

| %change | -33.29% | -24.26% | -7.98% | 240.67% | 10.92% | |

| Repetitions/Set | 11.52 | 9.20 | 5.09 | 9.38 | 9.29 | 9.32 |

| %change | -20.18% | -44.61% | 84.05% | -0.90% | 0.34% | |

| Sessions/Day | 1-2 | 1-2 | 1-2 | 1-2 | 1-2 | 1-2 |

| Days/Week | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Intensity-cycle | 2-3/1 | 2-3/1 | 2-3/1 | 2-3/1 | 2-3/1 | 2-3/1 |

| Mesocycle | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4. | 5. | 6. |

| Sets | 140 | 117 | 160 | 80 | 275 | 304 |

3. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stone, M.; Suchomel, T.; Hornsby, W.; Wagle, J.; Cunanan, A. (2022). Strength and conditioning in sports: from science to practice. Routledge.

- Stone, M.H.; Hornsby, W.G.; Suarez, D.G.; Duca, M.; Pierce, K.C. (2022). Training specificity for athletes: Emphasis on strength-power training: A narrative review. Journal of functional morphology and kinesiology, 7(4), 102. [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.H.; Hornsby, W.G.; Haff, G.G.; Fry, A.C.; Suarez, D.G.; Liu, J.S.; … & Pierce, K.C. (2021). Periodization and block periodization in sports: emphasis on strength-power training—a provocative and challenging narrative. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 35(8), 2351-2371. [CrossRef]

- Sands, W.A.; Wurth, J.J.; Hewit, J.K. (2012). Basics of strength and conditioning manual. Colorado Springs, CO: National Strength and Conditioning Association, 1, 100-104.

- National Academy of Sports Medicine. The Optimum Performance Training Model. https://www.nasm.org/certified-personal-trainer/the-opt-model?srsltid=AfmBOorZ0PunKb0Tws8ipgtXKux_ShSt3EbV-h_cJffExFYWrVp6SO0Z.

- Johnson, Q.R. (2025). The TFT Approach to Athlete Development: An Applied Model for Strength and Conditioning Professionals. Quincy Johnson Fitness. https://quincyjohnsonfitness.com/2025/03/30/the-tft-approach-to-athlete-development-an-applied-model-for-strength-and-conditioning-professionals/.

- Suchomel, T.J.; Nimphius, S.; Stone, M.H. (2016). The importance of muscular strength in athletic performance. Sports Medicine, 46(10), 1419-1449. [CrossRef]

- Suchomel, T.J.; Nimphius, S.; Bellon, C.R.; Stone, M.H. (2018). The importance of muscular strength: training considerations. Sports Medicine, 48(4), 765-785. [CrossRef]

- Suchomel, T.J.; Nimphius, S.; Bellon, C.R.; Stone, M.H. (2018). The importance of muscular strength: training considerations. Sports Medicine, 48(4), 765-785. [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, W.J.; Duncan, N.D.; Volek, J.S. (1998). Resistance training and elite athletes: adaptations and program considerations. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 28(2), 110-119. [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, W.J.; Deschenes, M.R.; Fleck, S.J. (1988). Physiological adaptations to resistance exercise: implications for athletic conditioning. Sports medicine, 6, 246-256.

- Bird, S.P.; Tarpenning, K.M.; Marino, F.E. (2005). Designing resistance training programmes to enhance muscular fitness: a review of the acute programme variables. Sports medicine, 35, 841-851.

- Weldon, A.; Duncan, M.J.; Turner, A.; Lockie, R.G.; Loturco, I. (2022). Practices of strength and conditioning coaches in professional sports: a systematic review. Biology of Sport, 39(3), 715-726. [CrossRef]

- Kukić, F.; Todorović, N.; Ćvorović, A.; Johnson, Q.; Dawes, J.J. (2020). Association of improvements in squat jump with improvements in countermovement jump without and with arm swing. Serbian Journal of Sports Sciences, 11(1), 29-35.

- Holloway, J.B.; Baechle, T.R. (1990). Strength training for female athletes: A review of selected aspects. Sports Medicine, 9, 216-228.

- McGuigan, M.R.; Wright, G.A.; Fleck, S.J. (2012). Strength training for athletes: does it really help sports performance?. International journal of sports physiology and performance, 7(1), 2-5. [CrossRef]

- Naclerio, F.; Chapman, M.; Larumbe-Zabala, E.; Massey, B.; Neil, A.; Triplett, T.N. (2015). Effects of three different conditioning activity volumes on the optimal recovery time for potentiation in college athletes. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 29(9), 2579-2585. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, R.S.; Faigenbaum, A.D.; Myer, G.D.; Stone, M.; Oliver, J.; Jeffreys, I.; Pierce, K.J.P.S.C. (2012). UKSCA position statement: Youth resistance training. Prof Strength Cond, 26, 26-39.

- Faigenbaum, A.D.; Kraemer, W.J.; Blimkie, C.J.; Jeffreys, I.; Micheli, L.J.; Nitka, M.; Rowland, T.W. (2009). Youth resistance training: updated position statement paper from the national strength and conditioning association. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 23, S60-S79. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D. (2008). An applied research model for the sport sciences. Sports medicine, 38, 253-263. [CrossRef]

- Tufano, J.J.; Brown, L.E.; Haff, G.G. (2017). Theoretical and practical aspects of different cluster set structures: a systematic review. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 31(3), 848-867. [CrossRef]

- Haff, G.G.; Burgess, S.; Stone, M.H. (2008). Cluster training: theoretical and practical applications for the strength and conditioning professional. Prof Strength Cond, 12, 12-17.

- Kawamori, N.; Haff, G.G. (2004). The optimal training load for the development of muscular power. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 18(3), 675-684. [CrossRef]

- Haff, G.G.; Jackson, J.R.; Kawamori, N.; Carlock, J.M.; Hartman, M.J.; Kilgore, J.L.; ... & Stone, M.H. (2008). Force-time curve characteristics and hormonal alterations during an eleven-week training period in elite women weightlifters. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 22(2), 433-446. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.; Bishop, C.; Turner, A.; Haff, G.G. (2021). Optimal training sequences to develop lower body force, velocity, power, and jump height: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 51, 1245-1271. [CrossRef]

- Haff, G.G.; Nimphius, S. (2012). Training principles for power. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 34(6), 2-12.

- Haff, G.G.; Hobbs, R.T.; Haff, E.E.; Sands, W.A.; Pierce, K.C.; Stone, M.H. (2008). Cluster training: A novel method for introducing training program variation. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 30(1), 67-76. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, R.S.; Oliver, J.L.; Faigenbaum, A.D.; Myer, G.D.; Croix, M.B.D.S. (2014). Chronological age vs. biological maturation: implications for exercise programming in youth. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 28(5), 1454-1464.

- Radnor, J.M.; Oliver, J.L.; Waugh, C.M.; Myer, G.D.; Moore, I.S.; Lloyd, R.S. (2018). The influence of growth and maturation on stretch-shortening cycle function in youth. Sports Medicine, 48, 57-71. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, R.S.; Radnor, J.M.; Croix, M.B.D.S.; Cronin, J.B.; Oliver, J.L. (2016). Changes in sprint and jump performances after traditional, plyometric, and combined resistance training in male youth pre-and post-peak height velocity. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 30(5), 1239-1247.

- Jeffreys, I. (2008). Quadrennial planning for the high school athlete. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 30(3), 74-83. [CrossRef]

- Eisenmann, J.C.; Hettler, J.; Till, K. (2024). The development of fast, fit, and fatigue resistant youth field and court sport athletes: a narrative review. Pediatric Exercise Science, 36(4), 211-223. [CrossRef]

- Gowtizke, B.; Milner, M. (1988). Scientific basis of human movement. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1988.

- MacIntosh, BR, Gardiner, P.F.; and McComas, AJ. (2006) Muscle Architecture and Muscle Fiber Anatomy. Champaing, IL: Human Kinetics.

- McComas, A.J. Skeletal Muscle. Champaing, IL: Human Kinetics, 1996.

- Roberts, M.D.; Haun, C.T.; Vann, C.G.; Osburn, S.C.; Young, K.C. (2020). Sarcoplasmic hypertrophy in skeletal muscle: a scientific “unicorn” or resistance training adaptation?. Frontiers in Physiology, 11, 816. [CrossRef]

- Deschenes, M.R. (2019). Adaptations of the neuromuscular junction to exercise training. Current opinion in physiology, 10, 10-16. [CrossRef]

- Collins, B.W.; Pearcey, G.E.; Buckle, N.C.; Power, K.E.; Button, D.C. (2018). Neuromuscular fatigue during repeated sprint exercise: underlying physiology and methodological considerations. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 43(11), 1166-1175. [CrossRef]

- Deschenes, M.R.; Maresh, C.M.; Crivello, J.F.; Armstrong, L.E.; Kraemer, W.J.; Covault, J. (1993). The effects of exercise training of different intensities on neuromuscular junction morphology. Journal of neurocytology, 22, 603-615. [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.H.; Stone, M.; Sands, W.A. (2007). Principles and practice of resistance training. Human Kinetics.

- Morton, J.P.; Close, G.L. (2016). The bioenergetics of sports performance. In Strength and Conditioning for Sports Performance (pp. 109-133). Routledge.

- Groennebaek, T.; Vissing, K. (2017). Impact of resistance training on skeletal muscle mitochondrial biogenesis, content, and function. Frontiers in physiology, 8, 713. [CrossRef]

- Reis, V.M.; Júnior, R.S.; Zajac, A.; Oliveira, D.R. (2011). Energy cost of resistance exercises: An uptade. Journal of human kinetics, 29, 33. [CrossRef]

- Jeukendrup, A.E.; Craig, N.P.; Hawley, J.A. (2000). The bioenergetics of world class cycling. Journal of science and medicine in sport, 3(4), 414-433. [CrossRef]

- Fatemeh, B.; Ramin, S.; Marzieh, N. (2016). Effect of high-intensity interval training on body composition and bioenergetic indices in boys–futsal players. Физическoе вoспитание студентoв, (5), 42-49. [CrossRef]

- Morton, J.P.; Close, G.L. (2016). The bioenergetics of sports performance. In Strength and Conditioning for Sports Performance (pp. 109-133). Routledge.

- Fry, A.C.; Kraemer, W.J.; Ramsey, L.T. (1998). Pituitary-adrenal-gonadal responses to high-intensity resistance exercise overtraining. Journal of applied physiology, 85(6), 2352-2359. [CrossRef]

- Fry, A.C.; Lohnes, C.A. (2010). Acute testosterone and cortisol responses to high power resistance exercise. Human physiology, 36, 457-461. [CrossRef]

- Fry, A.C.; Kraemer, W.J.; Gordon, S.E.; Stone, M.H.; Warren, B.J.; Fleck, S.J.; Kearney, J.T. (1994). Endocrine responses to overreaching before and after 1 year of weightlifting. Canadian journal of applied physiology, 19(4), 400-410. [CrossRef]

- Fry, A.C.; Kraemer, W.J.; Van Borselen, F.; Lynch, J.M.; Triplett, N.T.; Koziris, L.P.; Fleck, S.J. (1994). Catecholamine responses to short-term high-intensity resistance exercise overtraining. Journal of applied physiology, 77(2), 941-946. [CrossRef]

- Fry, A.C.; Kraemer, W.J.; Stone, M.H.; Warren, B.J.; Kearney, J.T.; Maresh, C.M.; ... & Fleck, S.J. (1993). Endocrine and performance responses to high volume training and amino acid supplementation in elite junior weightlifters. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 3(3), 306-322. [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, W.J.; Ratamess, N.A. (2003). Endocrine responses and adaptations to strength and power training. Strength and power in sport, 361-386.

- Kraemer, W.J. (1992). Exercise Physiology Corner: Influence of the endocrine system on resistance training adaptations. Strength & conditioning journal, 14(2), 47-54.

- Kraemer, W.J.; Rogol, A.D. (Eds.). (2008). The endocrine system in sports and exercise. John Wiley & Sons.

- Kraemer, W.J.; Ratamess, N.A. (2005). Hormonal responses and adaptations to resistance exercise and training. Sports medicine, 35, 339-361. [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, W.J.; Flanagan, S.D.; Volek, J.S.; Nindl, B.C.; Vingren, J.L.; Dunn-Lewis, C.; ... & Hymer, W.C. (2013). Resistance exercise induces region-specific adaptations in anterior pituitary gland structure and function in rats. Journal of Applied Physiology, 115(11), 1641-1647. [CrossRef]

- Haff, G.G.; Lehmkuhl, M.J.; McCoy, L.B.; Stone, M.H. (2003). Carbohydrate supplementation and resistance training. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 17(1), 187-196. [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, D.H.; Smith, A.E.; Kendall, K.L.; Stout, J.R. (2010). The possible combinatory effects of acute consumption of caffeine, creatine, and amino acids on the improvement of anaerobic running performance in humans. Nutrition research, 30(9), 607-614. [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, D.H.; Kendall, K.L.; Hetrick, R.P. (2013). Nutritional strategies to optimize youth development. In Strength and Conditioning for Young Athletes (pp. 207-221). Routledge.

- Volek, J.S. (2004). Influence of nutrition on responses to resistance training. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 36(4), 689-696. [CrossRef]

- Morton, R.W.; McGlory, C.; Phillips, S.M. (2015). Nutritional interventions to augment resistance training-induced skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Frontiers in physiology, 6, 245. [CrossRef]

- Jeukendrup, A.E. (2017). Periodized nutrition for athletes. Sports medicine, 47(Suppl 1), 51-63.

- Spriet, L.L.; Gibala, M.J. (2004). Nutritional strategies to influence adaptations to training. Food, Nutrition and Sports Performance II, 204-228.

- Volek, J.S.; Forsythe, C.E.; Kraemer, W.J. (2006). Nutritional aspects of women strength athletes. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 40(9), 742-748. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B.M.; Helms, E.R.; Trexler, E.T.; Fitschen, P.J. (2020). Nutritional recommendations for physique athletes. Journal of human kinetics, 71, 79. [CrossRef]

- Kreider, R.B.; Wilborn, C.D.; Taylor, L.; Campbell, B.; Almada, A.L.; Collins, R.; ... & Antonio, J. (2010). ISSN exercise & sport nutrition review: research & recommendations. Journal of the international society of sports nutrition, 7, 1-43. [CrossRef]

- Juhn, M.S. (2003). Popular sports supplements and ergogenic aids. Sports medicine, 33, 921-939. [CrossRef]

- Silver, M.D. (2001). Use of ergogenic aids by athletes. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 9(1), 61-70.

- Tokish, J.M.; Kocher, M.S.; Hawkins, R.J. (2004). Ergogenic aids: a review of basic science, performance, side effects, and status in sports. The American journal of sports medicine, 32(6), 1543-1553. [CrossRef]

- Applegate, E. (1999). Effective nutritional ergogenic aids. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 9(2), 229-239.

- Maughan, R.J. (1999). Nutritional ergogenic aids and exercise performance. Nutrition research reviews, 12(2), 255-280. [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M. (1996). Nutrition for improved sports performance: current issues on ergogenic aids. Sports Medicine, 21, 393-401.

- Ellender, L.; Linder, M.M. (2005). Sports pharmacology and ergogenic aids. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice, 32(1), 277-292.

- Frączek, B.; Warzecha, M.; Tyrała, F.; Pięta, A. (2016). Prevalence of the use of effective ergogenic aids among professional athletes.

- Williams, M.H.; Branch, J.D. (2000). Ergogenic aids for improved performance. Exercise and Sport Science. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 373-384.

- Adami, P.E.; Koutlianos, N.; Baggish, A.; Bermon, S.; Cavarretta, E.; Deligiannis, A.; ... & Papadakis, M. (2022). Cardiovascular effects of doping substances, commonly prescribed medications and ergogenic aids in relation to sports: a position statement of the sport cardiology and exercise nucleus of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 29(3), 559-575. [CrossRef]

- Fry, A.C. (2004). The role of resistance exercise intensity on muscle fibre adaptations. Sports medicine, 34, 663-679. [CrossRef]

- Fleck, S.J. (1988). Cardiovascular adaptations to resistance training. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 20(5 Suppl), S146-51. [CrossRef]

- Farup, J.; Kjølhede, T.; Sørensen, H.; Dalgas, U.; Møller, A.B.; Vestergaard, P.F. ;... & Vissing, K. (2012). Muscle morphological and strength adaptations to endurance vs. resistance training. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 26(2), 398-407. [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.H.; Sanborn, K.I.M.; O’bryant, H.S.; Hartman, M.; Stone, M.E.; Proulx, C.; ... & Hruby, J. (2003). Maximum strength-power-performance relationships in collegiate throwers. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 17(4), 739-745. [CrossRef]

- Häkkinen, K.; Newton, R.U.; Gordon, S.E.; McCormick, M.; Volek, J.S.; Nindl, B.C.; ... & Kraemer, W.J. (1998). Changes in muscle morphology, electromyographic activity, and force production characteristics during progressive strength training in young and older men. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 53(6), B415-B423. [CrossRef]

- Ploutz, L.L.; Tesch, P.A.; Biro, R.L.; Dudley, G.A. (1994). Effect of resistance training on muscle use during exercise. Journal of applied physiology, 76(4), 1675-1681. [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.H.; Potteiger, J.A.; Pierce, K.C.; Proulx, C.M.; O’bryant, H.S.; Johnson, R.L.; Stone, M.E. (2000). Comparison of the effects of three different weight-training programs on the one repetition maximum squat. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 14(3), 332-337. [CrossRef]

- Viitasalo, J.T.; Komi, P.V. (1981). Interrelationships between electromyographic, mechanical, muscle structure and reflex time measurements in man. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 111(1), 97-103. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.L.; Aagaard, P. (2006). Influence of maximal muscle strength and intrinsic muscle contractile properties on contractile rate of force development. European journal of applied physiology, 96, 46-52.

- Semmler, J.G.; Enoka, R.M. (2000). Neural contributions to changes in muscle strength. Biomechanics in sport: Performance enhancement and injury prevention, 2-20.

- Sale, D.G. (2003). Neural adaptation to strength training. Strength and power in sport, 281-314.

- Judge, L.; Moreau, C.; Burke, J. (2003). Neural adaptations with sport-specific resistance training in highly skilled athletes. Journal of sports sciences, 21(5), 419-427. [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.H.; Collins, D.; Plisk, S.; Haff, G.; Stone, M.E. (2000). Training principles: Evaluation of modes and methods of resistance training. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 22(3), 65.

- Boyd, J.M.; Andrews, A.M.; Wojcik, J.R.; Bowers, C.J. (2017). Perceptions of NCAA Division I athletes on strength training. Sport Journal, 1.

- Elder, C.; Elder, A.S.; Kelly, C. (2014). Collegiate athletes’ perceptions on the importance of strength and conditioning coaches and their contribution to increased athletic performance. J Athl Enhancement 3, 4(2).

- Bliss, A.; Langdown, B. (2023). Integrating strength and conditioning training and golf practice during the golf season: Approaches and perceptions of highly skilled golfers. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 18(5), 1605-1614. [CrossRef]

- Foulds, S.J.; Hoffmann, S.M.; Hinck, K.; Carson, F. (2019). The coach–athlete relationship in strength and conditioning: High performance athletes’ perceptions. Sports, 7(12), 244. [CrossRef]

- Biscardi, L.M.; Miller, A.D.; Andre, M.J.; Stroiney, D.A. (2024). Self-efficacy, Effort, and Performance Perceptions Enhance Psychological Responses to Strength Training in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I Athletes. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 38(5), 898-905. [CrossRef]

- Renshaw, I.; Chow, J.Y. (2019). A constraint-led approach to sport and physical education pedagogy. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 24(2), 103-116. [CrossRef]

- Renshaw, I.; Davids, K.; Newcombe, D.; Roberts, W. (2019). The constraints-led approach: Principles for sports coaching and practice design. Routledge.

- Glazier, P.S. (2017). Towards a grand unified theory of sports performance. Human movement science, 56, 139-156. [CrossRef]

- McGarry, T. (2009). Applied and theoretical perspectives of performance analysis in sport: Scientific issues and challenges. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 9(1), 128-140. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.J. (2014). The ecological approach to visual perception: classic edition. Psychology press.

- Renshaw, I.; Chow, J.Y.; Davids, K.; Hammond, J. (2010). A constraints-led perspective to understanding skill acquisition and game play: a basis for integration of motor learning theory and physical education praxis?. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 15(2), 117-137. [CrossRef]

- Renshaw, I.; Chow, J.Y.; Davids, K.; Hammond, J. (2010). A constraints-led perspective to understanding skill acquisition and game play: a basis for integration of motor learning theory and physical education praxis?. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 15(2), 117-137. [CrossRef]

- Fleck, S.J.; Falkel, J.E. (1986). Value of resistance training for the reduction of sports injuries. Sports medicine, 3, 61-68. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, I.; Shaw, B.; Brown, G.; Shariat, A. (2016). Review of the role of resistance training and musculoskeletal injury prevention and rehabilitation. J Orthop Res Ther, 2016, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Zwolski, C.; Quatman-Yates, C.; Paterno, M.V. (2017). Resistance training in youth: laying the foundation for injury prevention and physical literacy. Sports health, 9(5), 436-443. [CrossRef]

- Faigenbaum, A.D.; Myer, G.D. (2010). Resistance training among young athletes: safety, efficacy and injury prevention effects. British journal of sports medicine, 44(1), 56-63. [CrossRef]

- Lehman, G.J. (2006). Resistance training for performance and injury prevention in golf. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association, 50(1), 27.

- Saeterbakken, A.H.; Stien, N.; Pedersen, H.; Langer, K.; Scott, S.; Michailov, M.L.; ... & Andersen, V. (2024). The connection between resistance training, climbing performance, and injury prevention. Sports Medicine-Open, 10(1), 10.

- Junior, N.K.M. (2024). Structuring of the periodization in antiquity: the Roman military training. Tanjungpura Journal of Coaching Research, 2(1), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Morente Montero, Á. (2019). Sports training in Ancient Greece and its supposed modernity. [CrossRef]

- Issurin, V. (2008). Block periodization versus traditional training theory: a review. Journal of sports medicine and physical fitness, 48(1), 65.

- Bompa, T.O. (1996). Variations of periodization of strength. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 18(3), 58-61.

- Matveyev, L.P. Periodization of Sports Training. Moscow: Fiscuttura i Sport, 1996.

- Graham, J. (2002). Periodization research and an example application. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 24(6), 62-70.

- Comfort, P.; Jones, P.A.; McMahon, J.J. (Eds.). (2018). Performance assessment in strength and conditioning. Routledge.

- Carling, C.; Reilly, T.; Williams, A.M. (2008). Performance assessment for field sports. Routledge.

- O’donoghue, P. (2009). Research methods for sports performance analysis. Routledge.

- McGuigan, M. (2019). Testing and evaluation of strength and power. Routledge.

- Suchomel, T.J.; Nimphius, S.; Bellon, C.R.; Hornsby, W.G.; Stone, M.H. (2021). Training for muscular strength: Methods for monitoring and adjusting training intensity. Sports Medicine, 51(10), 2051-2066. [CrossRef]

- Vanrenterghem, J.; Nedergaard, N.J.; Robinson, M.A.; Drust, B. (2017). Training load monitoring in team sports: a novel framework separating physiological and biomechanical load-adaptation pathways. Sports medicine, 47, 2135-2142.

- Halson, S.L. (2014). Monitoring training load to understand fatigue in athletes. Sports medicine, 44(Suppl 2), 139-147.

- Cabarkapa, D.; Johnson, Q.R.; Cabarkapa, D.V.; Philipp, N.M.; Eserhaut, D.A.; Fry, A.C. (2024). Changes in Countermovement Vertical Jump Force-Time Metrics During a Game in Professional Male Basketball Players. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 38(7), 1326-1329. [CrossRef]

- Weakley, J.; Mann, B.; Banyard, H.; McLaren, S.; Scott, T.; Garcia-Ramos, A. (2021). Velocity-based training: From theory to application. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 43(2), 31-49. [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.B.; Ivey, P.A.; Sayers, S.P. (2015). Velocity-based training in football. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 37(6), 52-57. [CrossRef]

- Haff, G.G. (2010). Sport science. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 32(2), 33-45.

- Balagué, N.; Torrents, C.; Hristovski, R.; Kelso, J. (2017). Sport science integration: An evolutionary synthesis. European journal of sport science, 17(1), 51-62. [CrossRef]

- Pol, R.; Balagué, N.; Ric, A.; Torrents, C.; Kiely, J.; Hristovski, R. (2020). Training or synergizing? Complex systems principles change the understanding of sport processes. Sports Medicine-Open, 6, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, J.; Leite, N. (2013). Performance indicators in game sports. In Routledge handbook of sports performance analysis (pp. 115-126). Routledge.

- Wisbey, B.; Montgomery, P.G.; Pyne, D.B.; Rattray, B. (2010). Quantifying movement demands of AFL football using GPS tracking. Journal of science and Medicine in Sport, 13(5), 531-536. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Q.R.; Sealey, D.; Stock, S.; Gleason, D. (2023). Wins vs. Losses: Training Periodization Strategies Effect on Competition Outcomes within NCAA Division II Football. In Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise (Vol. 55, No. 9, pp. 725-725). Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins. [CrossRef]

- Cabarkapa, D.; Deane, M.A.; Fry, A.C.; Jones, G.T.; Cabarkapa, D.V.; Philipp, N.M.; Yu, D. (2022). Game statistics that discriminate winning and losing at the NBA level of basketball competition. Plos one, 17(8), e0273427. [CrossRef]

- Cabarkapa, D.; Fry, A.C.; Carlson, K.M.; Poggio, J.P.; Deane, M.A. (2021). Key kinematic components for optimal basketball free throw shooting performance. Central European Journal of Sport Sciences and Medicine, 36(04). [CrossRef]

- Zamparo, P.; Minetti, A.E.; Di Prampero, P. (2002). Interplay among the changes of muscle strength, cross-sectional area and maximal explosive power: theory and facts. European journal of applied physiology, 88(3), 193-202. [CrossRef]

- Bompa, T.O.; Buzzichelli, C. (2019). Periodization-: theory and methodology of training. Human kinetics.

- Stone, M.H.; O’Bryant, H.; Garhammer, J. (1981). A hypothetical model for strength training. The Journal of sports medicine and physical fitness, 21(4), 342-351.

- McMillan, J.L.; Stone, M.H.; Sartin, J.; Keith, R.; Marples, D.; Brown, C.; Lewis, R.D. (1993). 20-hour physiological responses to a single weight-training session. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 7(1), 9-21.

- Plisk, S.S.; Stone, M.H. (2003). Periodization strategies. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 25(6), 19-37.

- Stone, M.H.; Fry, A.C. (1998). Increased training volume in strength/power athletes. Overtraining in sport, 87-105.

- Kraemer, W.J. (1992). Endocrine responses and adaptations to strength training. Strength and power in sport, (s 292).

- Johnson, Q.R. (2025). The TFT Approach to MMA Athlete Development: Kearney Combat Sports Crowns Champions. Quincy Johnson Fitness. https://quincyjohnsonfitness.com/2025/03/30/the-tft-approach-to-mma-athlete-development-kearney-combat-sports-crowns-champions/.

- Johnson, Q.R. (2025). The TFT Approach to MMA Athlete Development: Jose Hernandez of Kearney Combat Sports Dominates. Quincy Johnson Fitness. https://quincyjohnsonfitness.com/2025/03/30/the-tft-approach-to-mma-athlete-development-jose-hernandez-of-kearney-combat-sports-dominates/.

- Johnson, Q.R. (2025). The TFT Approach to MMA Athlete Development: Delfino Benitez of Kearney Combat Sports Dominates. Quincy Johnson Fitness. https://quincyjohnsonfitness.com/2025/03/30/the-tft-approach-to-mma-athlete-development-delfino-benitez-of-kearney-combat-sports-dominates/.

- Johnson, Q.R. (2025). The TFT Approach to MMA Athlete Development: Vanessa Chavez of Kearney Combat Sports Dominates. Quincy Johnson Fitness. https://quincyjohnsonfitness.com/2025/03/30/the-tft-approach-to-mma-athlete-development-vanessa-chavez-of-kearney-combat-sports-dominates/.

- Johnson, Q.R. (2025). The TFT Approach to Powerlifting Athlete Development: Rylee Bentz of Kearney High School Dominates. Quincy Johnson Fitness. https://quincyjohnsonfitness.com/2025/03/30/the-tft-approach-to-powerlifting-athlete-development-rylee-bentz-of-kearney-high-school-dominates/.

- Johnson, Q.R. (2025). The TFT Approach to Powerlifting Athlete Development: Raeghann Mudloff-Behrens of St. Paul High School Dominates. Quincy Johnson Fitness. https://quincyjohnsonfitness.com/2025/03/30/the-tft-approach-to-powerlifting-athlete-development-raeghann-mudloff-behrens-of-st-paul-high-school-dominates/.

- Stone, M.H.; Pierce, K.C.; Sands, W.A.; Stone, M.E. (2006). Weightlifting: program design. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 28(2), 10-17.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).