1. Sustainability in the European Context

The successive climate changes witnessed in our globe have made it clear how important it is to take measures to preserve our environment. Specialists tell us that climate change is a consequence of the destruction of the ozone layer, caused by humans through their production of greenhouse gases. (GHG)

Therefore, the strategy created by the European Union (EU), to slow the high degradation of the ozone layer is based on the implementation of several policies that aim for climate preservation. These policies focus on reducing emissions of greenhouse gases by promoting sustainable energy consumption supplied by renewable energy sources.

1.1. Buildings and Construction

Since the EU considers buildings to represent 40% of the world’s energy consumption, it stands to reason that they should be one of the sectors to comply with energy efficiency directives.

The first directive directly targeting the construction area for the benefit of the environment was the Directive 2010/31/EU which was written and published in May 2010 by the European Union. Its main intention were:

Emphasizes the need to preserve the environment.

Recommend the use of renewable energy sources.

Suggest that the public sector promote an energy efficiency culture.

Implement the need for all EU member states to comply with goals for reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and the reference values by 2018 and 2020.

Therefore, it was imposed that:

As of December 31st,2018 all municipal buildings or those occupied by municipal entities should be Nearly Zero energy Building (NZEB).

As of December 31st, 2020, all new buildings must be NZEB.

NZEB buildings have energy consumption close to zero, and the low amount of energy they require is supplied from renewable energy sources integrated into the building itself. They are buildings with reduced greenhouse gas emissions.

The concept of NZEB buildings highlights the importance of implementing passive building systems early on to reduce consumption, enabling the application of energy supply systems from renewable energies to make the buildings functional.

Table 1.

European union goals for buildings and construction area.

Table 1.

European union goals for buildings and construction area.

The European union sets as goals for 2020

1. A 20% reduction of the emissions of greenhouse gases.

2. Reduce energy consumption by 20%.

3. Guarantee that 20% of the energetic needs are met by renewable sources

20% reduction of emissions of greenhouses gases/ 20% of the energy quota from renewable

sources in gross final consumption/ 20% of reduction of primary energy consumption.

Furthermore, according to the European Directive 2012/27/EU, signatories of the protocol against climate change should make efforts to renovate public sector buildings, incorporating strategies for energy autonomy through renewable energies to serve as examples of good practice.

1.2. Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement, established on October 5th, 2016, sets a global framework endorsed by 196 Parties at COP 21 in Paris to mitigate dangerous climate change by limiting global warming to well below 2ºC preferably to 1.5ºC, compared to pre-industrial levels. Considered a landmark, it is the first agreement in history to bring all nations into a common cause, addressing climate change.

According to the agreement, all stakeholders in the buildings and construction sector, from design to construction, operations, and demolition in both the private and public sectors, should strive for zero emissions in order to reduce energy-related CO2 emissions by 39 per cent [

1]

2. Energetic Sustainability in the Context of Cascais

To comply with European policies, Cascais has developed the Programa Cascais 2030, founded upon the 17 sustainable development goals proposed by the United Nations. One of these goals is the precise reduction of GHG emissions in the county. The county has been implementing several actions to pursue these goals and reach the proposed values by 2030. To this end, it has published the Energetic Sustainability Action Plan, with the most recent document being the Plano de Ação para a Adaptação às Alterações Climáticas de Cascais [

2].

This plan serves as a strategic document with measures aimed at reducing GHG emissions by 20% before 2030. It includes directives for various sectors, including energy efficiency in buildings, transportation, public lighting and production of local renewable energies.

Emerging Science Journal | Vol. x, No. x

In specific numbers, it aims to achieve the following reductions:

The energy consumption per capita from 9.81MWh (80).

The electric energy consumption from 614.482 MWh (30).

Reduce CO2 emissions from 8-10kgCO2/m2y (2015) to 3-7kgCO2/m2y (2020).

To track the progress towards these goals, the energy consumption of various sectors was recorded and published in the Matriz Energética de Gases de Efeito de Estufa do Concelho de Cascais – Ano de Referência 2015 [

3].

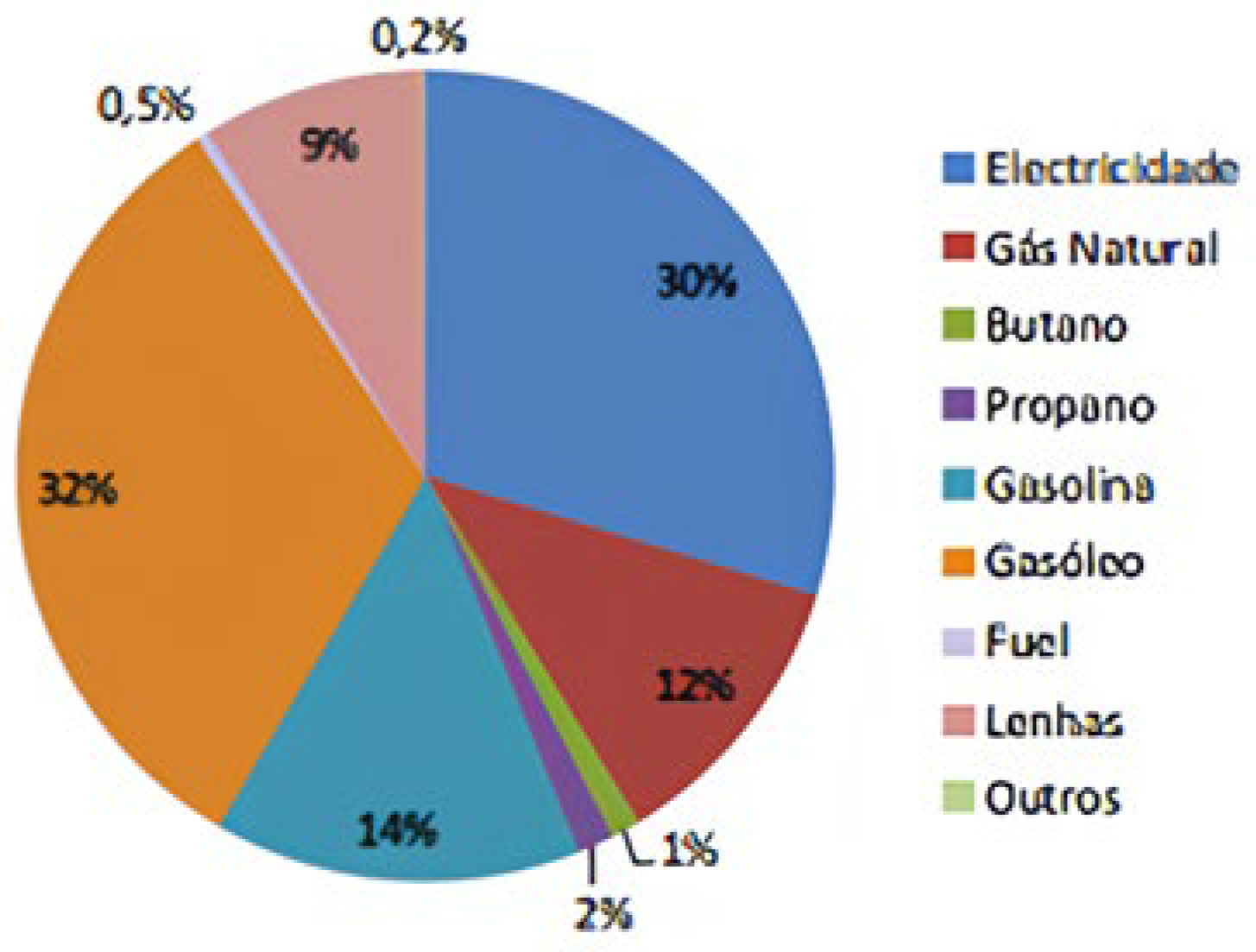

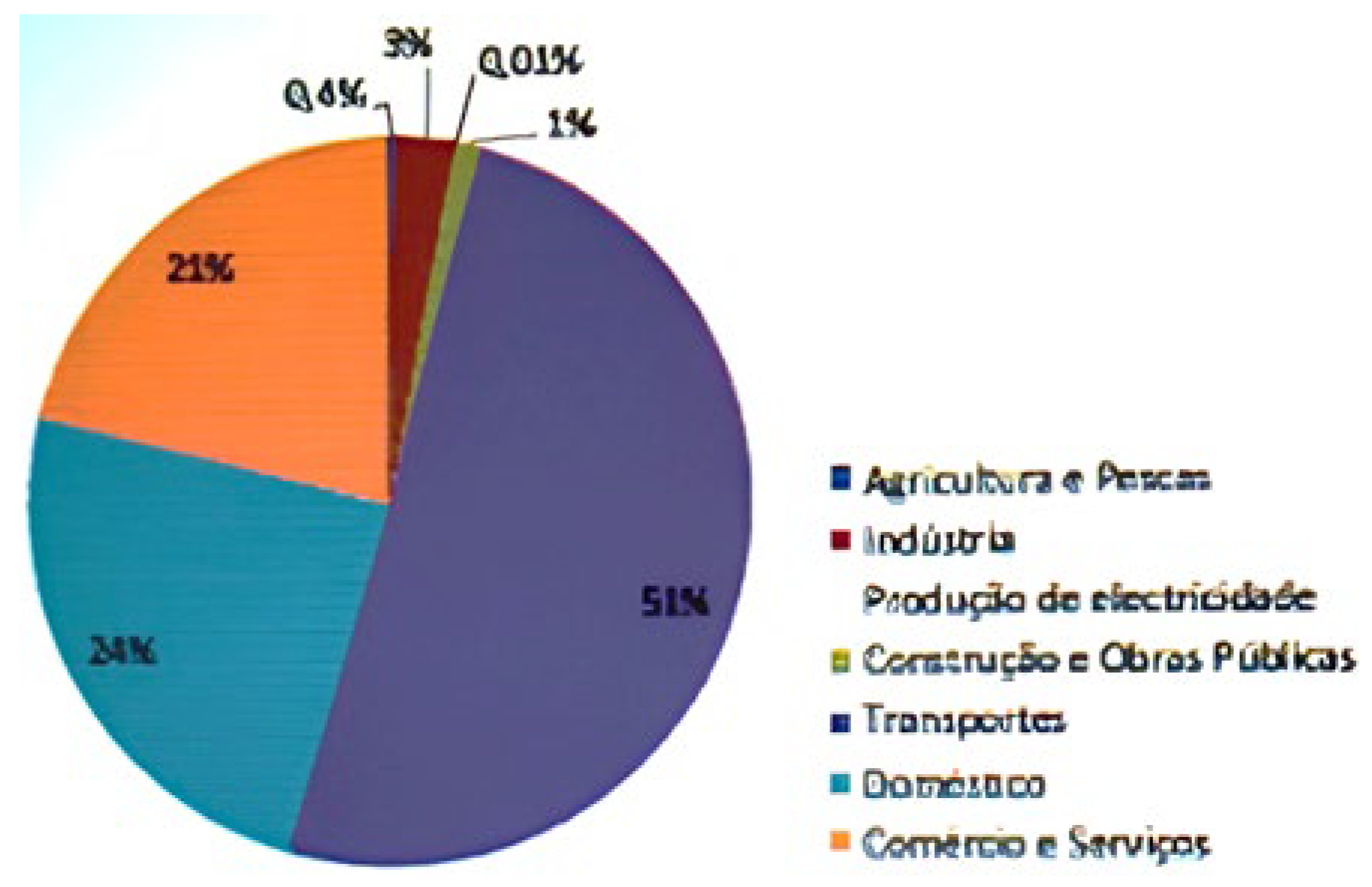

The document concludes that greenhouse gas emissions in the county of Cascais in 2015 amounted to 494 410 tons of CO2. Electricity was identified as the main source of energy, as shown in

Figure 1.

Analysing the sector that most significantly contributes to GHG emissions, it becomes evident that the county’s buildings (comprising both residential and commercial properties, including trade and services) are responsible for 45% of the greenhouse gas emissions in the county of Cascais, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

Table 2.

European union goals for 2030.

Table 2.

European union goals for 2030.

| Sector of activity |

GHG emissions (tonCO2) |

| Fishing and agriculture |

1 809 |

| Industries |

13 209 |

| Energy sector |

61 |

| Construction and public works |

5 231 |

| Transports |

249 735 |

| Domestic sector |

120 181 |

| Trade and services |

104 184 |

| Total |

494 410 |

The total energy consumption calculated in 2015 was 177 417 toe. When divided by the resident population of 210 361 and by the 109 816 family dwellings, we determined an energy consumption per capita of 0,84 toe/inhabitant and an energy consumption per dwelling of 0,51 toe/dwelling. These rates are higher than the national average of 0,43 toe/dwelling, indicating energy inefficiency in Cascais compared to the rest of the country. Analysing the energetic consumptions of the domestic sector, we can verify that the energies consumed are as follows:

The electricity consumption by the domestic sector during 2015 in Cascais, per accommodation, averaged 2,5 MWh/accommodation. In Portugal, the average electricity consumption per accommodation for the same year was 2,0 MWh/accommodation. This disparity highlights once again the thermal inefficiency of domestic buildings in the county of Cascais and underscores the urgency to implement measures to correct this inefficiency.

2.1. Contextualizing Municipal Housing in the County of Cascais

To eradicate unqualified urban areas lacking territorial planning, such as social, informal, or illegal settlements, the county of Cascais, like many others, has established mechanisms to relocate those in need. These efforts aim to provide dignified housing that facilitates the social and urban integration of marginalized and excluded populations. Despite substantial efforts to improve the quality of municipal housing in Cascais, it cannot be overlooked that the construction of these buildings was primarily cost-controlled, prioritizing low construction costs per square meter over construction quality. As a result, the lack of housing comfort and evident signs of degradation in these buildings are noticeable today, necessitating requalification and rehabilitation to enhance the well-being of residents. Until 1997, the municipality owned 923 municipal dwellings. Subsequently, through the Special Relocation Program (PER), aimed at eradicating shantytowns in Lisbon and Oporto metropolitan areas, Cascais constructed an additional 1192 accommodations by 2010. Currently, there are approximately 1298 municipal housing dwellings in the county (source: SigWebCascais) [

4]. This increase is attributed to the various options provided by PERCascais [

5], such as renting, purchasing, and housing at controlled costs.

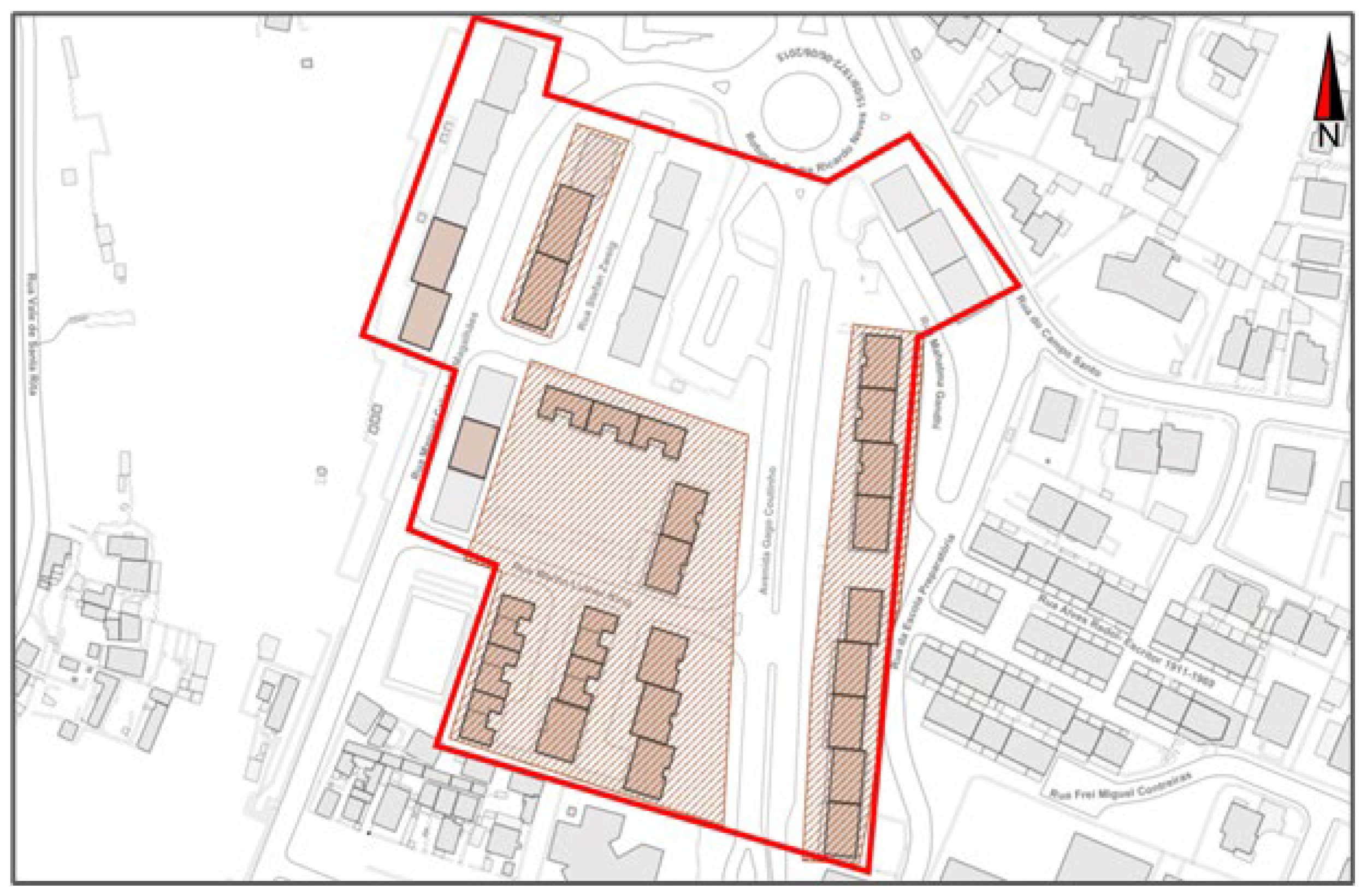

Figure 3.

depicts the buildings of municipal housing in the county of Cascais.

Figure 3.

depicts the buildings of municipal housing in the county of Cascais.

Combining the imperative of European policies aimed at reducing greenhouse gases with the necessity for Cascais to enhance energy efficiency in the domestic sector, and recognizing the need to renovate municipal housing buildings, we propose a study and calculation of the energy consumption of a municipal housing unit in the county. This endeavor serves to align the renovation of the municipal housing stock with the goal of reducing GHG emissions for the county.

2.2. District Fim do Mundo

Out of a total of 193 municipal housing buildings in the county of Cascais, we have chosen to focus on the case study of the district “Fim do Mundo” district in Galiza, São João do Estoril. This district is notable for having one of the highest concentrations of municipal housing buildings in the area. Constructed in the late 1970s it was designed to accommodate more than 600 people, albeit without offering reasonable health or living conditions. In 2009, the last shack-like constructions in the area were demolished. The district also features a project dating back to 1988, comprising 188 dwellings across 23 buildings, each with four floors. The buildings share similar architectural features, differing primarily in typology and solar orientation.

Figure 4.

depicts the district Fim do Mundo in Galiza, São João do Estoril.

Figure 4.

depicts the district Fim do Mundo in Galiza, São João do Estoril.

Figure 5.

display the case study.

Figure 5.

display the case study.

Address - Rua Martin Luther King, nº29, Bairro da Galiza, São Pedro do Estoril -Cascais

Construction Year: 1989

Construction Area: 474,16m2

Implantation Area: 118m2

Nº of units: 6 units

Nº of floors: 4 floors

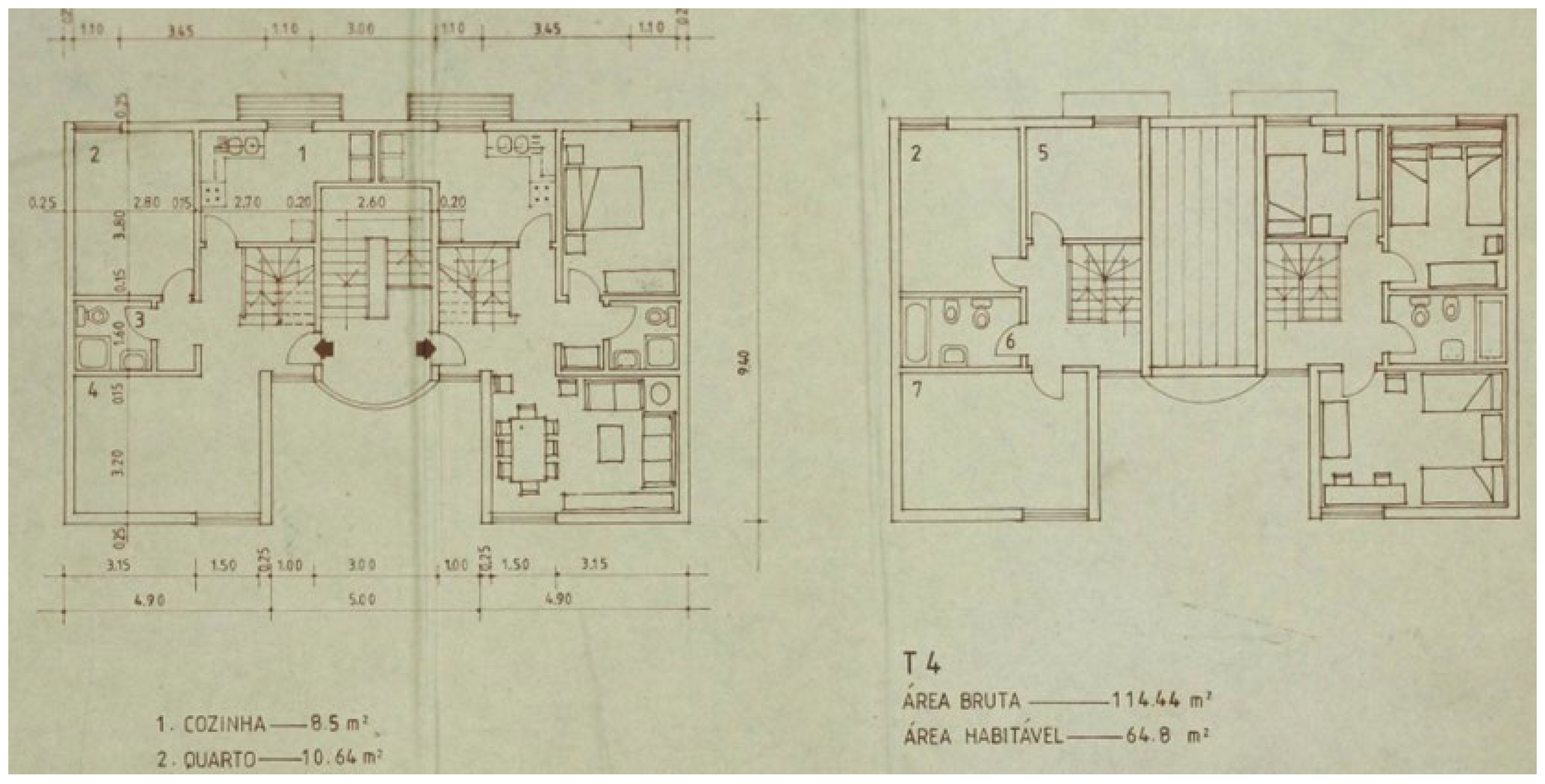

Typology: 4 T1 + 2 T4

Area per dwelling

T1: 61,30m2

T4: 114,44m2 (usable area 64,80m2)

Usable area T1: 39,42; T4: 64,80m2

Fraction T4 – Kitchen 8,5m2; Bedroom 10,64m2; Bathroom 2,88m2; Living room 14,08m2; Bedroom 6,88m2; I.S 4,48m2; Bedroom 14,08m2;

Fraction T1 – Living room 14,00m2; Kitchen 8,50m2; Bedroom 10,64m2; bathroom 1,80m2; Hall 4,48m2; / Construction – Building nº16, Construtora Reimidas / Project – Housing Division of CMCascais, date 12.05.1988 / Natural gas (aprox 18%) / Butane (aprox 7%) / Propane (aprox 5%);

Figure 6.

illustrates the East/West façade of building 29 in the district Fim do Mundo in Galiza, São João do Estoril.

Figure 6.

illustrates the East/West façade of building 29 in the district Fim do Mundo in Galiza, São João do Estoril.

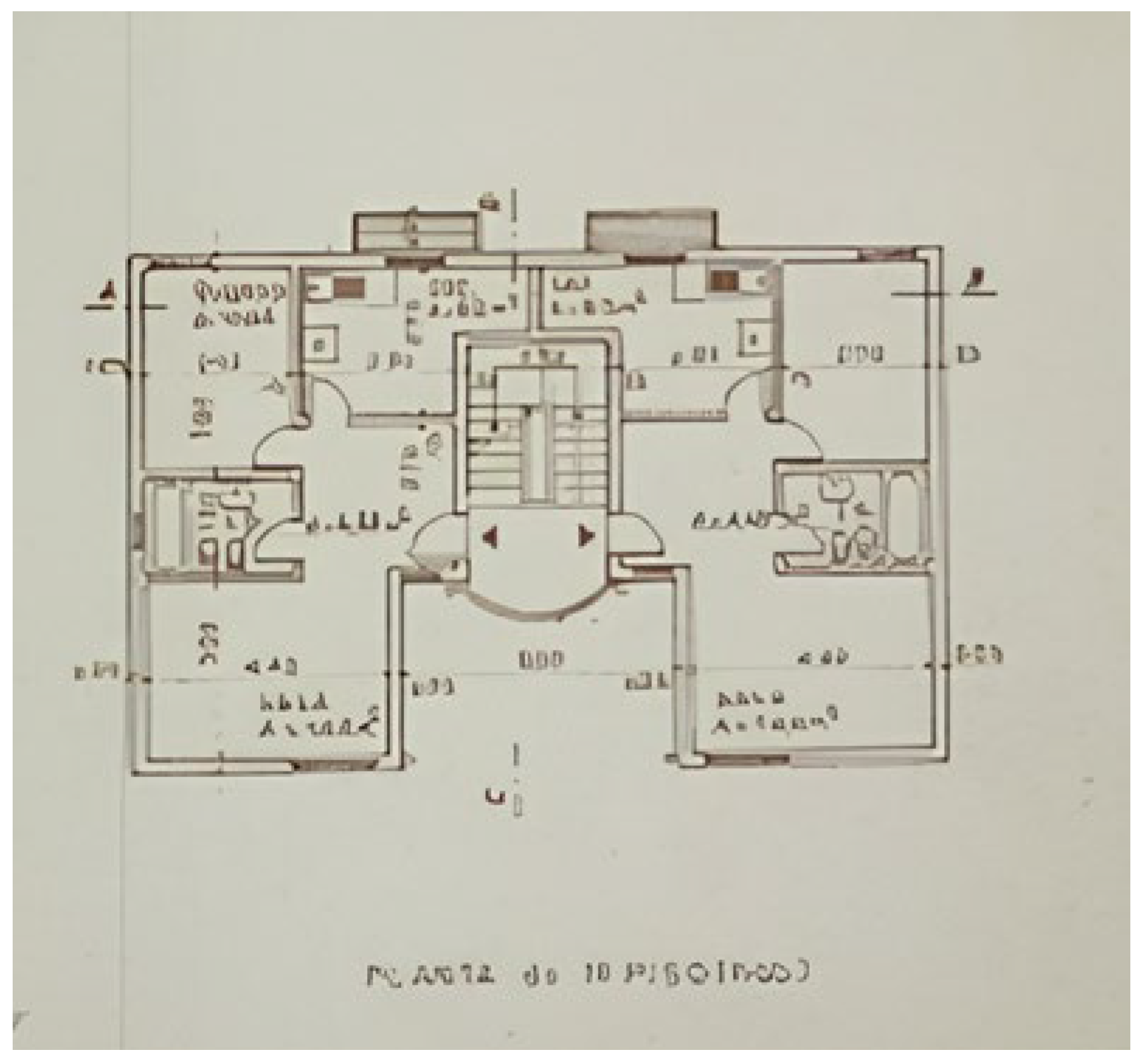

Figure 7.

presents the blueprint of the 1st floor, featuring the one-bedroom typology, of building 29 in the district Fim do Mundo in Galiza, São João do Estoril.

Figure 7.

presents the blueprint of the 1st floor, featuring the one-bedroom typology, of building 29 in the district Fim do Mundo in Galiza, São João do Estoril.

Figure 8.

displays the blueprint of the 2nd and 3rd floors, showcasing the four-bedroom typology, of building 29 in the district Fim do Mundo in Galiza, São João do Estoril.

Figure 8.

displays the blueprint of the 2nd and 3rd floors, showcasing the four-bedroom typology, of building 29 in the district Fim do Mundo in Galiza, São João do Estoril.

Materials used in the construction of the building include:

Roof – Corrugated asbestos cement waterproof roofing sheets.

Hall flooring – Ceramic Tiles in the style of S.Paulo and Vidraça stone.

Units flooring – Carpet; Bathroom and Kitchen flooring: hydraulic marble mosaic.

Exterior walls – Hollow brick masonry without thermal insulation, rendered on the outside with textured paint and plastered on the inside, with a total thickness of 30cm.

Interior Walls – Hollow brick masonry, without thermal insulation, plastered on both sides, with a total thickness of 15cm.

Walls of the main entrance and common stairs– Carapas Mass.

Entrance hall and common area ceilings: Rendered with textured paint.

Exterior span frame of the building (entrance door) - natural color anodized aluminium.

Exterior span frame of the unit - entrance door of the unit in tola wood or treated mahogany; kitchen windows; rooms/living room’s windows; bathroom windows - natural colour anodized aluminium.

Windows – Simple window with sliding window frames in natural color anodized aluminium, without thermal break, with single glazing.

Span protection – Plastic exterior roller shutter with interior pocket.

Frames of exterior spans – threshold or sill in vidraça stone.

Equipment – Bathtub of 1.60x0.70; Column washbasin; Toilet bowl; bidet; flushing water tank; kitchen ventilation, inox sink; thermolaminated kitchen cupboards.

Solar exposure – Main façade to the east and the back façade to the west.

2.3. Methodology and Values

As part of our analysis and methodology, we calculated the energy consumption of a dwelling, focusing on a T1 typology. After researching various methods available on the market, we opted for the most comprehensive software,

EnergyPlus Version 5 [

6].

This software, provided by the Department of Energy of the United States, allows for a simulation of the thermal balance of a building with more variables than alternative methods, including the one recommended in Portugal by the Energetic Efficiency Directive: Decreto-lei nº118/2013 [

6].

EnergyPlus was chosen because it simulates the thermal consumption of a building by considering factors such as its geometry, the climatic conditions of its location, the materials used, building solutions, and existing climatic systems within the building. This comprehensive approach provides a more accurate representation of the energy consumption of the dwelling.

Table 3.

Calculations of thermal comfort of an interval between 20° and 25º.

Table 3.

Calculations of thermal comfort of an interval between 20° and 25º.

| Needs (kWh) |

Bedroom (area) |

Living Room (area) |

Unit |

| Heating |

880,60 |

795,80 |

1676,40 |

| Cooling |

617,80 |

1876,50 |

2494,30 |

| Global |

1498,40 |

2672,30 |

4170,70 |

2.4. Deductions

If we analyse the obtained value of 4,1 MWh per accommodation unit and compare it to the average electric energy consumption values in the residential sector in Cascais during 2015 (2,5MWh per accommodation unit), we observe that the values are considerably higher, even when compared to the national average of 2,0MWh per accommodation unit in 2015.

From these results, we can infer that the municipal housing unit under study exhibits significantly lower energy performance and building systems efficiency, indicating room for improvement in becoming more energy efficient. Upon initial analysis, we can assume that the low levels of energy efficiency result not only from poor-quality materials and building systems but also from the solar orientation of the building:

Under-optimized exposure, with solar orientation of the façades east/west and nonexistent or deficient solar protections.

Incorrect orientation of the spans for natural ventilation through predominant winds.

These factors contribute to the higher energy consumption observed and highlight potential areas for improvement in enhancing the energy efficiency of the building.

2.5. Solutions and Optimization

The proposed optimization solutions are as follows:

Passive solutions for reduction of energy for heating:

Promote solar gains through adequate reflection and solar and/or Trombe walls.

Control thermal losses through exterior thermal insulation and/or more efficient glazed spans.

Enhance thermal inertia through pavement with solar exposure.

Adjust the size of spans depending on the thermal gains or losses they may imply.

Passive solutions for reduction of energy consumption for cooling:

Limit solar gains with effective shading solutions.

Control heat gains with more efficient glazed spans.

Promote natural ventilation by incorporating openings for predominant winds.

Implement double glazing (adding a new glaze outside the existing one) to improve thermal performance at a lower investment.

Promote thermal balance by correctly placing shading shutters.

Active solutions

Installation of solar panels for water heating.

Utilization of micro-generation devices with a capacity of 271.00kW.

Use of efficient electrical equipment certified with AA rating.

Implementation of efficient lighting, such as compact fluorescent lamps or LED technology.

Collection and treatment of rainwater for use in common areas and gardens.

The active solutions proposed should cover the heating and cooling needs of the dwelling/building, which should be low, through the passive solutions mentioned earlier [

7]. To achieve this, the solutions were chosen for their accessibility and availability in the market [

8], with some of them supplied by companies in the county of Cascais. Based on the Program Cascais 2030, the goal is to have buildings with a supply of 50kWh/m2y of renewable energy and 0-15 kWh/m2y of primary energy.

3. Conclusions

In conclusion, the case study illustrates a municipal housing building with low energetic efficiency, presenting significant potential for reducing energy consumption and aligning with the concept of Nearly Zero Energy Buildings. Expanding this case study to encompass all municipal buildings in the county could yield substantial reductions in energy consumption, aligning with the goals outlined in the Programa Cascais 2030.

It is evident that simple and accessible solutions can effectively reduce both passive and active energy consumption in the building. By integrating the necessity of renovation and maintenance of municipal housing buildings with rehabilitation efforts focused on promoting energy efficiency, numerous benefits can be realized: Direct benefits to residents through increased comfort, well-being, and reduced annual housing expenses. Improvement of the city’s image through the creation of well-conceived buildings.

Environmental benefits achieved by reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Fulfilment of municipal commitments and the establishment of an environmentally friendly reputation for the county. Establishment of a model for energetically efficient buildings, serving as a valuable case study for future projects.

Overall, this approach not only addresses the immediate energy consumption issues but also contributes positively to various aspects of community life, environmental sustainability, and the municipality’s long-term goals. Incorporating energy efficiency into the architectural design process from the outset not only leads to more integrated and cost-effective buildings but also promotes sustainability and enhances the overall quality of the built environment.

Indeed, if we prioritize energy efficiency from the initial stages of building design and planning, the architecture will inherently concern into the architectural design process from the outset, several benefits can be realized: 1. Integrated design: energy-efficient features can be seamlessly incorporated into the building’s design, rather than being retrofitted later.

2.Cost savings: Implementing energy-efficient technologies and practices during the initial construction phase can lead to lower construction and operational costs.

3.Optimized performance: Early consideration of energy efficiency allows for the selection of the most appropriate and cost-effective technologies and strategies.

4.Long-term benefits: investing in energy efficiency during the design and construction phase can result in long-term savings on energy bills and maintenance costs.

5.Environmental Impact: buildings contribute positively to environmental sustainability and help mitigate climate change.

References

- World Green Building Council, “Annual report 2020” (November 2020). Available online: https://worldgbc.org/sites/default/files/ WorldGBC%20Annual%20Report%202020_1.pdf.

- J.Dinis, G.Penha and I.Campos, “Plano de Ação para a Adaptação às Alterações Climáticas de Cascais” (September 2017), EMAC – Cascais Ambiente. ISBN 978-989-54806-0-9.

- R.Segurado and S.Pereira, “Matriz Energética de Gases de Efeito de Estufa do Concelho de Cascais – ano de referencia 2015” (July, 2017), Instituto de engenharia mecânica – polo instituto superior técnico. Available online: https://data.cascais.pt/ sites/default/files/2017-12/Matriz%20Cascais%202015 nova versão _1.pdf.

- Geographic System Information – SigWeb, Geo Cascais,(November 2020). Available online: https://geocascais.cascais.pt.

- M.Allegra, S.Tulumello, R.Falanga, R.Cachado, A.Ferreira, A.Colombo, S.Alves, “Um Novo PER? Realojamento e Políticas da Habitação em Portugal” (2017), Observatorio de Ambiete e Sociedade. ISBN 978-972-671-475-0.

- Veiga, “Metodologias para a classificação de edifícios de balanço de energia nulo (NZEB) aplicadas a um edifício residencial” (2015), Faculdade de Ciências, Ulisboa. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10451/22892.

- F.Ascione, B.Nicola, O.Bottcher, R.Kaltenbrunner and G.Vanoli “Net zero-energy buildings in Germany: Design, model calibration and lessons learned from a case-study in Berlin” (2016), ScienceDirect. [CrossRef]

- P.Chastas, T.Theodosiou, D.Bikas and K.Kontoleon, “Embodied energy and nearly zero energy buildings: a review in residential buildings” (2017), ScienceDirect. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).