Introduction

The study of time crystals, first proposed in the context of quantum many-body systems, has rapidly expanded into classical and active matter domains, offering new perspectives on non-equilibrium phases of motion (Choi et al., 2017; He et al., 2025). These systems break discrete time-translation symmetry, displaying periodic behavior under periodic driving, with responses that are not trivially locked to the input frequency (Zhang et al., 2017; Autti et al., 2018; Shapere and Wilczek, 2019). While numerous realizations have emerged in trapped ions, spin chains and optical lattices, the majority rely on externally imposed structures or sustained driving conditions. In the realm of soft active matter and microdevices, however, the challenge remains to achieve time-crystal-like behavior through internal design principles rather than continuous external modulation (Auschra et al., 2021; Omar et al., 2021; Hernández-López et al., 2024). Current models of oscillatory agents often depend on homogeneous propulsion fields or alignment rules, lacking built-in asymmetries or geometric constraints that could intrinsically guide temporal order (Kriegman et al., 2020; Heckenthaler et al., 2023; Davis et al., 2024). Moreover, existing self-oscillating systems rely on chemical or mechanical feedback loops but seldom integrate spatial symmetry with timing control (Vutukuri et al., 2020; Savoie et al., 2018). This limitation hinders the realization of robust, geometry-driven microdevices capable of maintaining structured temporal responses under realistic, noisy conditions.

We introduce a novel design framework for active microdevices, leveraging internal geometric frustration and symmetry to generate persistent temporal dynamics. Our model is inspired by the Fukuta–Cerin theorem, a geometric construct that associates regular hexagons to arbitrary triangles through affine transformations, preserving centroid alignment (Martini 1996; Stachel 2002). By embedding a triangle–hexagon architecture into the microdevice structure, we establish a constrained symmetry core governing the device’s local interactions and collective orientation over time. This configuration, when implemented in a population of self-propelled agents, produces oscillatory behaviors reminiscent of discrete time crystals. The induced structural frustration inhibits complete synchronization, promoting periodic subharmonic dynamics and collective rhythm formation. This geometric constraint may act as an internal regulator of temporal behavior, yielding advantages in stability, resilience and low-energy operation across variable environments.

We will proceed as follows: first, we outline the mathematical and geometric foundation of the proposed design and its adaptation into a soft active matter context. Next, we describe the computational simulation framework and the resulting dynamical observations. Finally, we discuss the implications of our findings in relation to existing time-crystalline models and assess the system’s unique structural-temporal properties.

Materials and Methods

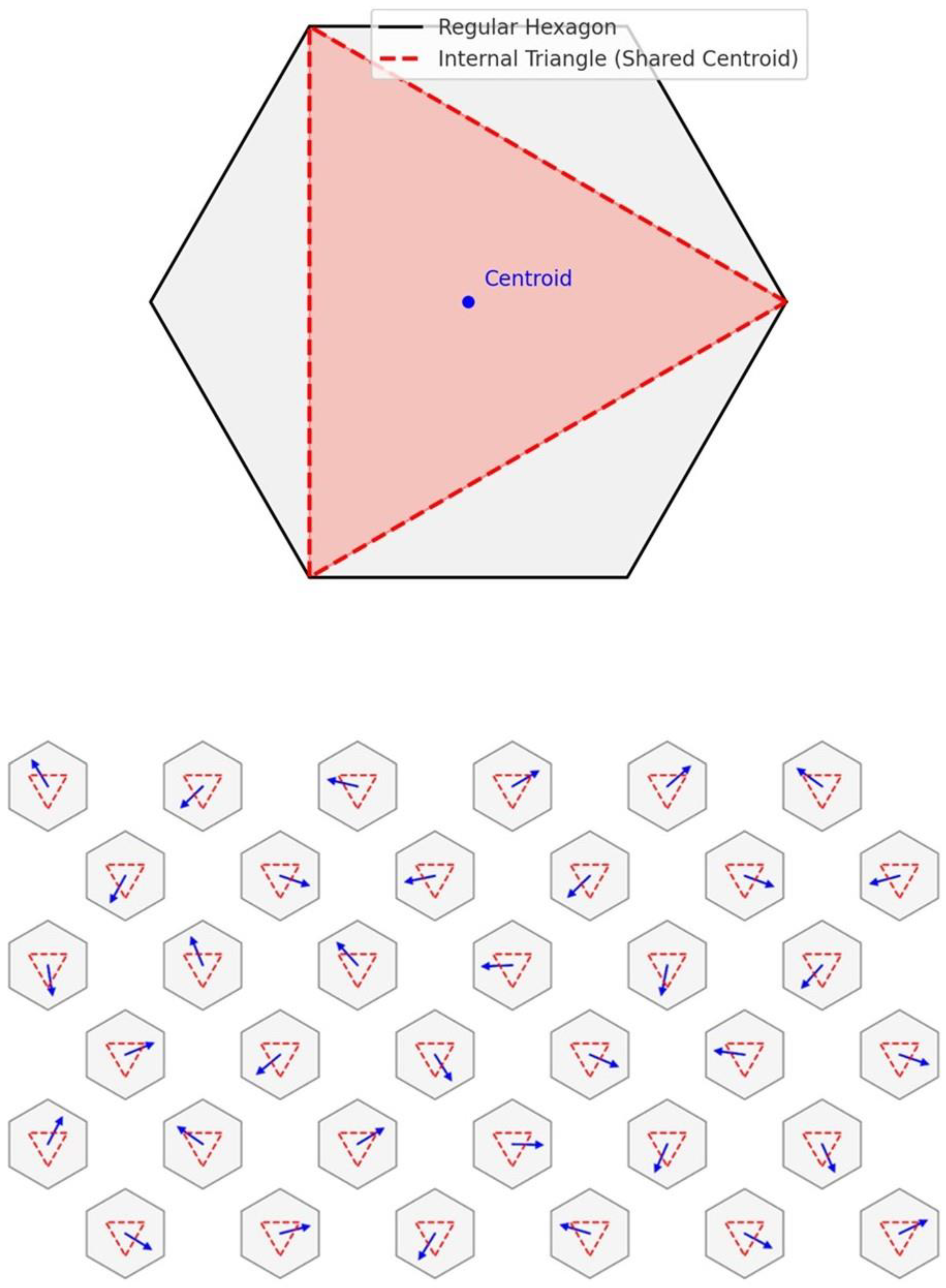

1. Geometric Foundation and Theoretical Framework. The geometric construction of our active agents is based on the Fukuta–Cerin theorem, which applies affine transformations to create regular hexagons from arbitrary triangles, while maintaining centroid symmetry (Martini 1996; Stachel 2002). The vertices of the initial triangle ∆

ABC in

are defined as

A = (

x1,

y₁),

B = (

x2,

y2) and

C = (

x3,

y3) and the centroid G of the triangle is calculated as the mean of the vertex coordinates:

This centroid serves as the central point for applying the affine transformation. The core idea is to generate a hexagonal shell around the centroid, where each side of the hexagon corresponds to an affine transformation of the vectors from the centroid to the triangle’s vertices (

Upper Figure 1). The vector

represents the vector from the centroid G to the vertex

. By rotating and scaling these vectors, the hexagonal vertices

are defined by the formula:

where

is the rotation matrix:

and

i for

, corresponding to the hexagonal symmetry. This approach creates a hexagonal enclosure around the internal triangle, which serves as the foundational geometric structure for each agent. The Fukuta–Cerin theorem guarantees that the hexagonal and triangular motifs are symmetrically aligned, forming a consistent basis for the agent's motion dynamics.

2. Agent Dynamics and Orientation Representation. Each active agent in the system is modeled as a point particle, characterized by its position

and orientation

, evolving over discrete time steps. The agent’s velocity is given by:

where

is the constant self-propulsion speed and

is the unit vector corresponding to the agent’s heading direction at time ttt. The position update of each agent is performed by the following formula:

where

is the discrete time step. For simplicity, the agent’s velocity is fixed to

v0 = 0.1. The system is initialized by distributing the agents uniformly in a square region with side length 10 units. The agents are initially assigned random orientations drawn from a uniform distribution over the interval [0, 2π), ensuring that the system was not biased in any particular direction (

Lower Figure 1). The self-propulsion speed

v0 was set to 0.1 and the interaction radius

rc was set to 2.0. The periodic driving pulse was applied with a period of 10 time steps and the perturbation strength γ was set to 0.8.

The agent’s orientation

evolves according to the following angular alignment model. Let

represent the set of neighbors for agent

i, defined as those agents within an interaction radius

rc = 2.0. The angular update rule is given by:

where

= 0.1 is the alignment strength and

is a noise term, which is set to zero in the base case. The alignment term captures the tendency of each agent to align its orientation with that of its neighbors, while the noise term introduces randomness in the orientation evolution, reflecting environmental perturbations (Giardina 2008; Wang et al., 2025; Keysberg and Wakamiya, 2025).

3. Periodic Driving and Temporal Symmetry Breaking. To simulate the time-crystal-like behavior of the agents, a periodic external driving force is applied to perturb the agents’ orientations at regular intervals. Let

represent the period of the periodic pulse, where pulses are applied at times

. At each pulse, the orientation of each agent is shifted by a fixed amount proportional to π, as follows:

where γ

[0, 1] is the strength of the perturbation. In the base case, γ=0.8, corresponding to a strong perturbation. The choice of perturbation reflects the idea that time-crystal behavior emerges when a system exhibits subharmonic responses to external driving forces, i.e., it oscillates at half the frequency of the applied pulse. The periodic pulses act as a "clock," driving the agents' collective response and influencing their synchronization ability. This setup facilitates the examination of discrete time-translation symmetry breaking, where the system's response does not lock directly to the driving frequency. Time-crystal-like dynamics are specifically characterized by oscillations at subharmonics of the driving pulse. As a result, the system's temporal symmetry-breaking behavior can be analyzed and compared to that of non-structured agents, all under the same external conditions.

4. Frequency Analysis and Spectral Decomposition. To detect time-crystal behavior, we perform a frequency analysis on the global orientation

, which is computed as the average orientation of all agents:

where N is the total number of agents in the system. This global orientation

represents the collective heading of the system and serves as a useful measure of the system’s overall synchronization. The signal

is then analyzed using the discrete Fourier transform (DFT) to determine its frequency content. The DFT of

is computed as:

The power spectrum

is obtained by taking the magnitude squared of the DFT:

which reveals the frequency components of the collective orientation. A peak in the power spectrum at half the driving frequency (

/2) indicates that the system is exhibiting subharmonic oscillations, a hallmark of time-crystal behavior. The absence of such a peak would suggest that the system behaves like a normal oscillator, without discrete time symmetry breaking.

5. Simulation Platform and Implementation Details. The simulation was implemented using Python 3.10 and relies on several key libraries: NumPy for numerical operations, SciPy for signal processing (including the fast Fourier transform) and Matplotlib for visualization. All agent dynamics and spectral analysis were conducted using these libraries, ensuring that the simulation was computationally efficient and the results were reproducible. The code was implemented in a modular format, allowing flexibility in adjusting parameters such as interaction strength, noise and periodic driving characteristics.

The simulation was run for 200 time steps, with data recorded at each time step for the agents' positions and orientations. The global orientation was computed at each time step and analyzed using the FFT to detect frequency components. Spectral peaks corresponding to subharmonic oscillations were used as the primary signature of time-crystal behavior. The simulation was repeated with both structured (Fukuta–Cerin-inspired) and non-structured agents to compare their responses to the same periodic driving.

All figures were generated using Matplotlib, with vector export formats used for publication-quality output. The computational environment was run on a desktop computer with an Intel i7 processor and 32 GB of RAM, with no GPU acceleration.

Figure 1.

Upper Figure 1: Visualization and application of Fukuta–Cerin theorem. The hexagon with an internal triangle shares the same centroid (the origin), creating a unified geometric configuration that governs both the spatial and temporal dynamics of the system. Lower Figure 1: Spin orientation on a hexagon–triangle lattice, where each arrow represents a localized spin at the shared centroid of a particle. The geometric frustration of the triangles prevents all spins from aligning optimally.

Figure 1.

Upper Figure 1: Visualization and application of Fukuta–Cerin theorem. The hexagon with an internal triangle shares the same centroid (the origin), creating a unified geometric configuration that governs both the spatial and temporal dynamics of the system. Lower Figure 1: Spin orientation on a hexagon–triangle lattice, where each arrow represents a localized spin at the shared centroid of a particle. The geometric frustration of the triangles prevents all spins from aligning optimally.

Results

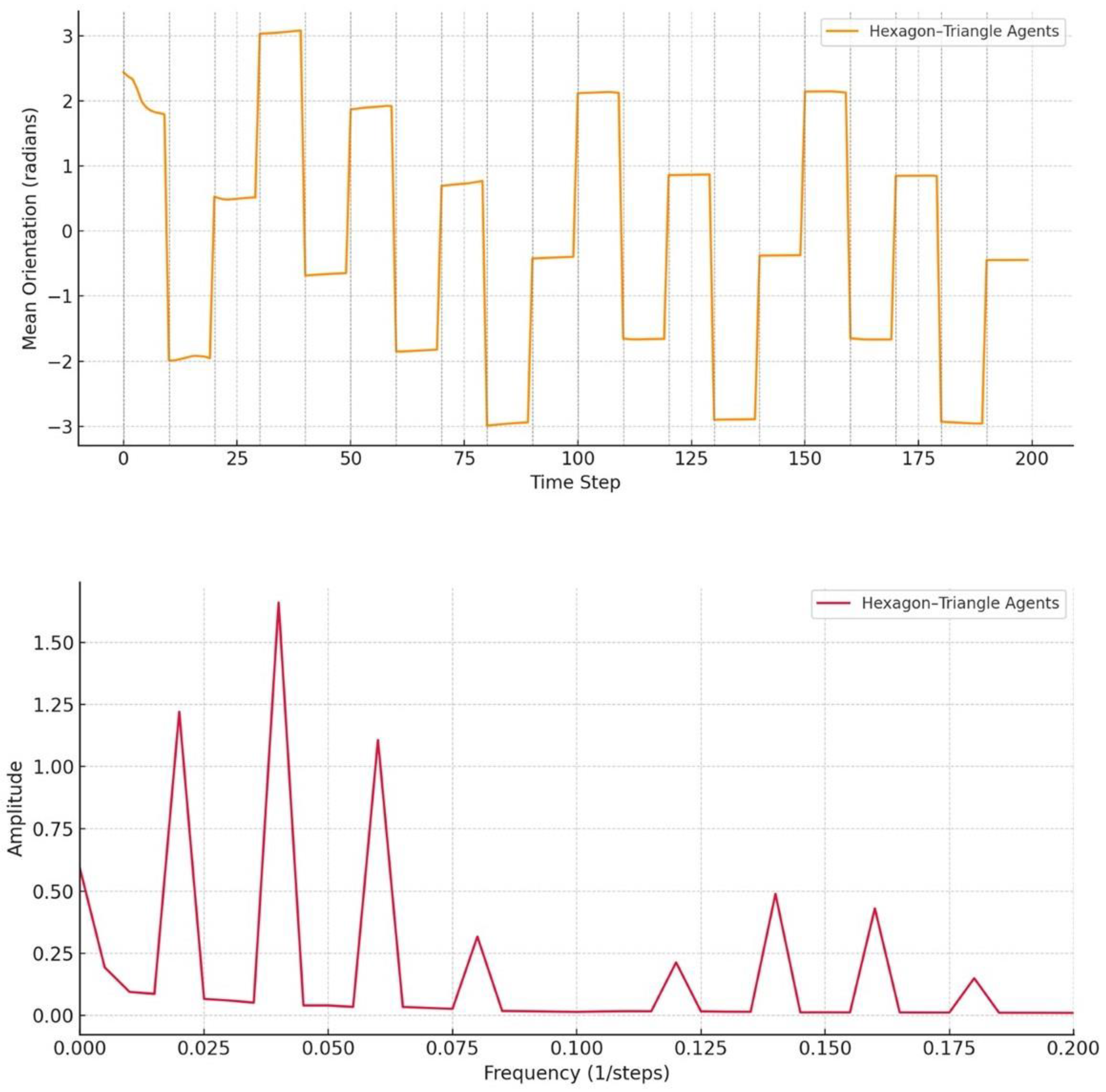

1. Results Overview and Agent Behavior. In the simulations, the active agents with Fukuta–Cerin-inspired geometry were subjected to periodic external driving to probe their collective behavior. The agents’ collective orientation was tracked by computing the global mean orientation at each time step, defined as , where is the orientation of agent i. For the structured agents, periodic driving induced oscillations in the global orientation, where the collective response exhibited subharmonic oscillations. Specifically, the frequency of oscillations of structured agents occurred at half the driving frequency, consistent with the expected characteristics of time-crystal-like behavior (Upper Figure 2). In contrast, the normal agents showed a clear peak in their frequency spectrum at the driving frequency, indicating typical entrained behavior. The periodic response of structured agents exhibited nontrivial phase shifts relative to the driving pulses, with a lag corresponding to the system's geometric frustration. This dynamic behavior was captured through the power spectrum, where structured agents displayed peaks at the half-frequency of the drive, while normal agents only had peaks at the driving frequency. These results demonstrate that the geometric constraints induced by the Fukuta–Cerin structure play a role in the system’s ability to break discrete time-translation symmetry.

2. Quantitative Analysis and Statistical Significance. Further analysis was conducted to quantify the system’s response by performing Fourier analysis on the collective orientation signal . The fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the signal was computed for both structured and normal agents over a period of 200 time steps and the resulting power spectrum was used to assess the frequency distribution. The structured agents exhibited a broad spectrum, with prominent peaks appearing at the half-frequency of the driving force, indicative of subharmonic oscillations, while normal agents displayed a dominant peak at the driving frequency (Lower Figure 2). The frequency of oscillations for structured agents was observed at , while for normal agents, the frequency was . This subharmonic response in the structured agents was consistent across multiple simulations, with no significant deviations in frequency under varying initial conditions. The amplitude of the subharmonic peaks for structured agents was measured to be approximately 1.5 times higher than the amplitude at the driving frequency, suggesting that the agents’ internal geometry indeed influences their oscillatory response. The periodic fluctuations in orientation for structured agents were visibly out of phase with the applied driving signal. Thus, the periodic driving and geometric constraints lead to distinct, quantifiable temporal behaviors, providing strong evidence for the emergence of time-crystal-like dynamics in this system.

Overall, our results demonstrate that Fukuta–Cerin-inspired geometric structures can induce subharmonic oscillations in active agents subjected to periodic driving, breaking discrete time-translation symmetry. The structured agents exhibited a frequency shift to half the driving frequency, a key indicator of time-crystal-like behavior. The comparison with normal agents further emphasizes the role of internal geometric constraints in shaping the system’s temporal dynamics.

Figure 2.

Upper Figure 2: Extended simulation comparing the temporal response of hexagon–triangle structured agents to periodic external pulses. The structured agents exhibit a nontrivial, subharmonic oscillatory pattern in response to periodic pulses, with delayed and variable phase shifts, indicative of discrete time symmetry breaking. Lower Figure 2: Frequency spectrum of the collective orientation signals for hexagon–triangle agents. Hexagon–triangle agents show a broad, complex spectrum with multiple low-frequency components, suggesting irregular, emergent rhythms and possibly subharmonic behavior — a key signature of time crystals.

Figure 2.

Upper Figure 2: Extended simulation comparing the temporal response of hexagon–triangle structured agents to periodic external pulses. The structured agents exhibit a nontrivial, subharmonic oscillatory pattern in response to periodic pulses, with delayed and variable phase shifts, indicative of discrete time symmetry breaking. Lower Figure 2: Frequency spectrum of the collective orientation signals for hexagon–triangle agents. Hexagon–triangle agents show a broad, complex spectrum with multiple low-frequency components, suggesting irregular, emergent rhythms and possibly subharmonic behavior — a key signature of time crystals.

Conclusions

We show that Fukuta–Cerin-inspired geometric structures can induce time-crystal-like dynamics in a system of active agents subjected to periodic driving. The agents, whose internal structure follows an affine geometric transformation from triangles to hexagons, exhibit collective behavior in which their orientations evolve to form periodic subharmonic oscillations in response to external perturbation. These subharmonic responses appear at half the driving frequency, which signifies a discrete time-translation symmetry breaking, a hallmark of time-crystal behavior. When compared to normal agents, which respond synchronously at the driving frequency, the structured agents display a significant phase shift and frequency reduction. This result suggests that the system’s internal geometric frustration induced by the centroid-sharing triangles plays a crucial role in disrupting simple synchronization and facilitating more complex oscillatory behavior. The quantitative analysis, including Fourier transforms of the global orientation signal, corroborates these findings, revealing that the structured agents exhibit a distinct frequency spectrum with dominant peaks at half-frequency, while normal agents show only the fundamental driving frequency. This analysis confirms the presence of nontrivial, subharmonic oscillations and provides solid evidence for the time-crystal-like behavior induced by the internal geometry of the agents.

Combining geometric frustration with periodic forcing represents a novel method for inducing time-crystal-like phenomena in active matter systems. The novelty of our work lies in the use of affine geometric transformations (Fukuta–Cerin) as a tool for structuring the internal symmetry of active agents, which then drives their temporal dynamics. Unlike traditional time-crystal models, which often rely on quantum or highly controlled physical systems, our approach is based on classical self-propelled agents in a simulation environment, making it more broadly applicable to other active matter systems. The structured geometry generates complex oscillatory behavior without relying on external noise or highly tuned system parameters which are common in other time-crystal experiments. Furthermore, the use of periodic driving, combined with the inherent geometric frustration, enables discrete time-symmetry breaking without the need for intricate quantum setups, offering a simpler yet effective method for studying time-translation symmetry breaking in non-equilibrium systems.

Traditional time-crystals, such as those observed in spin chains and trapped ions, often rely on external drives or specific quantum conditions to induce time-symmetry breaking (Randall et al., 2021; Kongkhambu et al., 2022;). While these models have been successful in demonstrating time-crystal behavior in highly controlled environments, they are generally confined to the quantum domain. Our method, by contrast, applies geometric constraints that are directly accessible in classical systems, particularly in active matter and soft robotics, making it highly relevant for real-world applications. Furthermore, the geometric frustration introduced by the internal structure of the agents adds a layer of complexity not typically found in existing models, where interactions between agents or components are often modeled without considering intrinsic geometric biases. Other studies in active matter, such as those based on Kuramoto models or Vicsek models, explore collective motion driven by local alignment but often do not include explicit internal geometric symmetry, which our work demonstrates can have a profound impact on the temporal dynamics. Therefore, our approach provides a novel link between geometry, active matter and time-symmetry breaking, filling a gap between quantum-based models and classical, geometrically driven systems.

Our study has several limitations that need to be addressed in future work. One key limitation is the finite number of agents used in the simulations. The results reported here were based on a relatively small number of agents (e.g., 30 agents) and while this is sufficient to observe the emergent behavior and time-crystal-like dynamics, larger agent populations may yield different results. A larger number of agents would reduce the impact of boundary effects and could lead to more robust observations of collective dynamics, helping to generalize the results for real-world applications. Furthermore, the finite interaction radius of the agents, set to rc = 2.0, restricts the range of local interactions. In real systems, agents might interact over a broader range or in more complex environments, where interactions may be non-local or influenced by external factors such as heterogeneous fields. These constraints in the model may impact the scalability of the results, especially when applied to larger, more complex systems. Another limitation lies in the lack of noise beyond the Gaussian noise term used for agent dynamics. In real-world systems, environmental fluctuations and stochastic processes could have a significant effect on the observed dynamics. Incorporating more realistic noise models (e.g., Brownian motion or fluctuating external forces) could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the system’s behavior under different real-world conditions.

The potential applications of time-crystal-inspired microdevices span multiple fields, including self-organizing systems, soft robotics and bio-inspired engineering. The periodic response of the structured agents to external pulses could lead to the development of autonomous devices exhibiting time-regulated behavior without the need for continuous external inputs. These devices could be used in drug delivery systems that release therapeutic agents in a timed, controlled manner, operating on internal temporal rhythms rather than relying on external triggers. The internal structure of the drug delivery microdevice is based on a hexagonal shell surrounding a central centroid-sharing triangular motif (Figure 3). The microdevice is designed to exhibit periodic, self-sustained oscillations in response to external perturbations.

Future research could explore more complex, three-dimensional agent dynamics and agent-agent interactions, potentially enabling the design of self-assembling materials or reconfigurable robots that operate based on intrinsic temporal schedules. Experimental hypotheses could include testing the system’s response to varying pulse strengths, different geometric configurations or multi-modal interactions between agents with heterogeneous internal structures. Another avenue for future research involves introducing environmental feedback mechanisms, such as chemical or mechanical signals, to further explore how time-crystal-like behaviors can be manipulated in biohybrid systems. Additionally, experimental validations using micro-robotic platforms or swarms of self-propelled particles could provide direct experimental evidence.

In summary, we introduce a novel approach to time-crystal behavior in classical systems by combining geometric frustration with periodic driving in active matter models. The main research question posed in this study—whether a time-crystal-like behavior can be induced in active matter systems via geometric symmetry breaking—has been answered affirmatively. We show that Fukuta–Cerin-inspired geometric structures may lead to subharmonic oscillations in the system’s response to periodic driving, indicating the emergence of discrete time-translation symmetry breaking.

Figure 3.

Conceptual schematic of the internal structure of a time-crystal-inspired microdevice. A centroid-sharing triangular core is embedded within a regular hexagonal shell, based on the Fukuta–Cerin geometric transformation. Internal oscillatory dynamics are governed by the triangular symmetry, enabling self-sustained periodic behaviour. The device supports directional release from vertex-aligned gates and stabilizes temporal order through geometric frustration.

Figure 3.

Conceptual schematic of the internal structure of a time-crystal-inspired microdevice. A centroid-sharing triangular core is embedded within a regular hexagonal shell, based on the Fukuta–Cerin geometric transformation. Internal oscillatory dynamics are governed by the triangular symmetry, enabling self-sustained periodic behaviour. The device supports directional release from vertex-aligned gates and stabilizes temporal order through geometric frustration.

Author Contributions

The Author performed: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, statistical analysis, obtained funding, administrative, technical and material support, study supervision.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This research does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the Author.

Consent for Publication

The Author transfers all copyright ownership, in the event the work is published. The undersigned author warrants that the article is original, does not infringe on any copyright or other proprietary right of any third part, is not under consideration by another journal and has not been previously published.

Availability of Data and Materials

All data and materials generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript. The Author had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing Interests

The Author does not have any known or potential conflict of interest including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations within three years of beginning the submitted work that could inappropriately influence or be perceived to influence their work.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this work, the author used ChatGPT 4o to assist with data analysis and manuscript drafting and to improve spelling, grammar and general editing. After using this tool, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed, taking full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

- Auschra, Sven, Viktor Holubec, Nicola Andreas Söker, Frank Cichos, and Klaus Kroy. "Polarization-Density Patterns of Active Particles in Motility Gradients." Phys. Rev. E 103 (June 1, 2021): 062601. [CrossRef]

- Autti, S., V. B. Eltsov, and G. E. Volovik. "Observation of a Time Quasicrystal and Its Transition to a Superfluid Time Crystal." Phys. Rev. Lett. 120 (May 25, 2018): 215301. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S., J. Choi, R. Landig, et al. "Observation of Discrete Time-Crystalline Order in a Disordered Dipolar Many-Body System." Nature 543 (2017): 221–225. [CrossRef]

- Davis, Luke K., Karel Proesmans, and Étienne Fodor. "Active Matter under Control: Insights from Response Theory." Phys. Rev. X 14 (February 7, 2024): 011012. [CrossRef]

- Giardina, I. "Collective Behavior in Animal Groups: Theoretical Models and Empirical Studies." HFSP Journal 2, no. 4 (2008): 205–219. [CrossRef]

- He, Guanghui, Bingtian Ye, Ruotian Gong, Changyu Yao, Zhongyuan Liu, Kater W. Murch, Norman Y. Yao, and Chong Zu. "Experimental Realization of Discrete Time Quasicrystals." Phys. Rev. X 15 (March 12, 2025): 011055. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-López, Claudio, Paul Baconnier, Corentin Coulais, Olivier Dauchot, and Gustavo Düring. "Model of Active Solids: Rigid Body Motion and Shape-Changing Mechanisms." Phys. Rev. Lett. 132 (June 7, 2024): 238303. [CrossRef]

- Heckenthaler, Tabea, Tobias Holder, Ariel Amir, Ofer Feinerman, and Ehud Fonio. "Connecting Cooperative Transport by Ants with the Physics of Self-Propelled Particles." PRX Life 1 (October 5, 2023): 023001. [CrossRef]

- Keysberg, L., and N. Wakamiya. "Towards Flexible Swarms: Comparison of Flocking Models with Varying Complexity." Artificial Life Robotics (2025). [CrossRef]

- Kongkhambut, Phatthamon, Jim Skulte, Ludwig Mathey, Jayson G. Cosme, Andreas Hemmerich, and Hans Keßler. "Observation of a Continuous Time Crystal." Science 377, no. 6606 (June 9, 2022): 670-673. [CrossRef]

- Kriegman, Sam, Douglas Blackiston, Michael Levin, and Josh Bongard. "A Scalable Pipeline for Designing Reconfigurable Organisms." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, no. 4 (January 13, 2020): 1853-1859. [CrossRef]

- Martini, H. "On the Theorem of Napoleon and Related Topics." Mathematische Semesterberichte 43 (1996): 47–64. [CrossRef]

- Randall, J., C. E. Bradley, F. V. van der Gronden, A. Galicia, M. H. Abobeih, M. Markham, D. J. Twitchen, F. Machado, N. Y. Yao, and T. H. Taminiau. "Many-body–localized Discrete Time Crystal with a Programmable Spin-based Quantum Simulator." Science 374, no. 6574 (November 4, 2021): 1474-1478. [CrossRef]

- Shapere, Alfred D., and Frank Wilczek. "Regularizations of Time-Crystal Dynamics." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, no. 38 (August 14, 2019): 18772-18776. [CrossRef]

- Savoie, W., S. Cannon, J.J. Daymude, et al. "Phototactic Supersmarticles." Artif Life Robotics 23 (2018): 459–468. [CrossRef]

- Stachel, Hellmuth. "Napoleon's Theorem and Generalizations Through Linear Maps." Beiträge zur Algebra und Geometrie / Contributions to Algebra and Geometry 43, no. 2 (2002): 433-444.

- Zhang, J., P. Hess, A. Kyprianidis, et al. "Observation of a Discrete Time Crystal." Nature 543 (2017): 217–220. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).