Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Necropsies and Microscopic Examination

2.2. Anatomopathologival Study

2.3. Molecular Procedures

2.3.1. DNA Extraction

2.3.2. End-Point PCR and Primers

2.3.3. Sequencing, Alignment and Comparison Through Phylogenetic Networks

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of Dictyocaulosis in Deer at Sampling Location

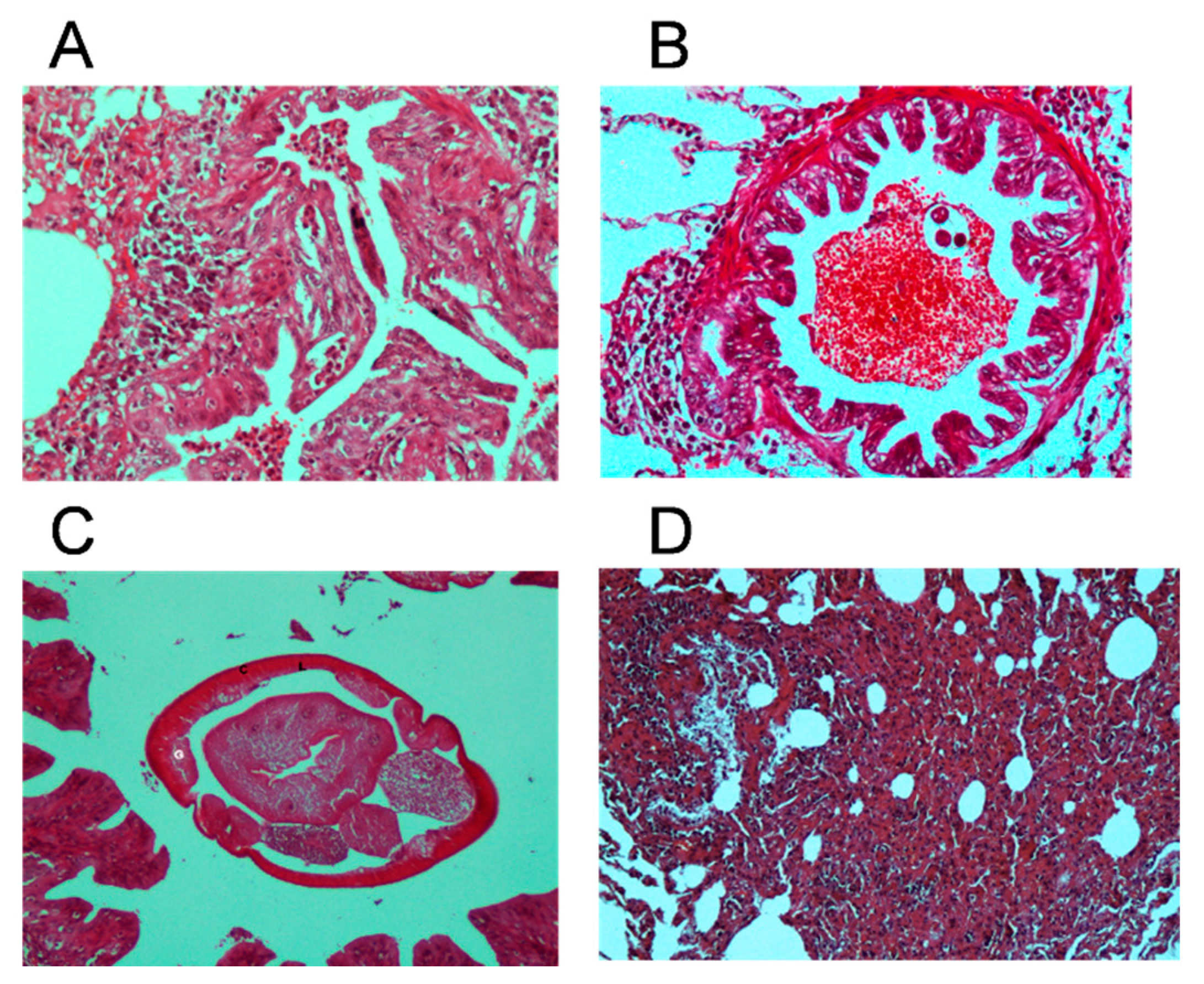

3.2. Morphological Identification and Anatomopathological Finding in Dictyocaulosis

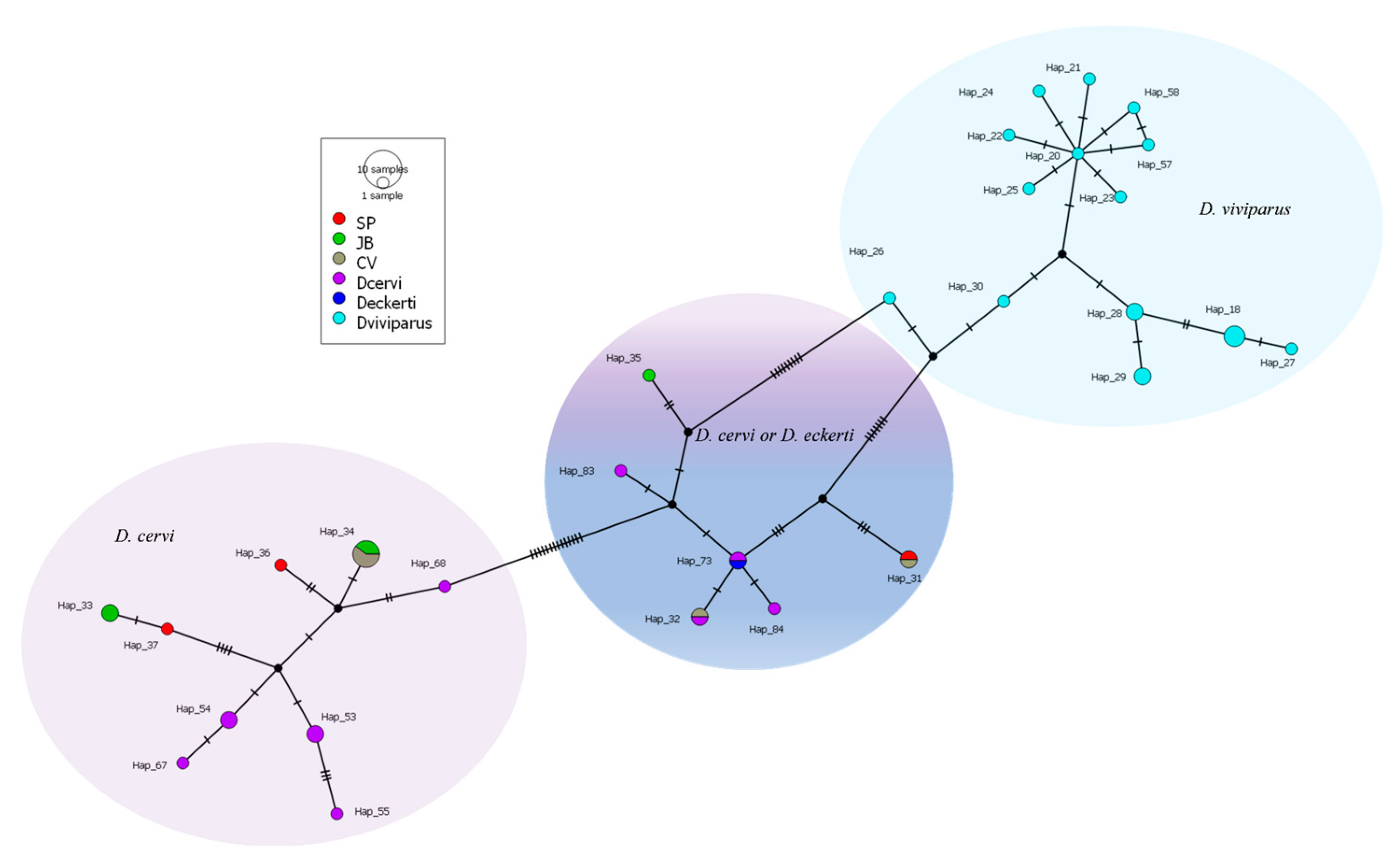

3.3. Barcoding Finding Through Sequencing COI Gene

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence of Dictyocaulosis in Deer in Extremadura

4.2. Findings After Anatomopathological Study

4.3. Molecular of Dictyocaulus spp. Assessment

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huaman, J.L., Helbig, K.J., Carvalho, T.G., Doyle, M., Hampton, J., Forsyth, D.M., Pople, A.R., Pacioni, C. A Review Of Viral And Parasitic Infections In Wild Deer In Australia With Relevance To Livestock And Human Health. Wildl. Res., 50 (2023), Pp. 593-602. [CrossRef]

- S. Shamsi, K. Brown, N. Francis, D.P. Barton, D.J. Jenkins. First Findings Of Sarcocystis Species In Game Deer And Feral Pigs In Australia.Int. J. Food Microbiol. (2024). [CrossRef]

- Vainutis, K.S., Voronova, A.N., Andreev, M.E. et al. Morphological and molecular description of Dictyocaulus xanthopygus sp. nov. (Nematoda: Trichostrongyloidea) from the Manchurian wapiti Cervus elaphus xanthopygus. Syst Parasitol 100, 557–570 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Pyziel, A. M., Laskowski, Z., Demiaszkiewicz, A. W., Y Höglund, J. (2017). Interrelationships of Dictyocaulus Spp. In Wild Ruminants With Morphological Description Of Dictyocaulus Cervi N. Sp. (Nematoda: Trichostrongyloidea) From Red Deer, Cervus Elaphus. Journal Of Parasitology, 103(5), 506-518. [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, L. M., Y Höglund, J. (2002). Dictyocaulus Capreolus N. Sp. (Nematoda: Trichostrongyloidea) From Roe Deer, Capreolus Capreolus And Moose, Alces Alces In Sweden. Journal Of Helminthology, 76(2), 119-124. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Carreno And S. A. Nadler . 2003. Phylogenetic Analysis Of The Metastrongyloidea (Nematoda: Strongylida) Inferred From Ribosomal Rna Gene Sequences. Journal Of Parasitology 89:965–973.

- Carreno, R. A., Diez-Baños, N., Hidalgo-Argüello, M. del R., & Nadler, S. A. (2009). Characterization of Dictyocaulus Species (Nematoda: Trichostrongyloidea) from Three Species of Wild Ruminants in Northwestern Spain. Journal of Parasitology, 95(4), 966-970. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Gibbons And L. F. Khalil . 1988. A Revision Of The Genus Dictyocaulus Railliet And Henry, 1907 (Nematoda: Trichostrongyloidea) With The Description Of D. Africanus N. Sp. From African Artiodactylids. Revue De Zoologie Africaine 102:151–175.

- J. Höglund, D. A. Morrison, B. P. Divina, E. Wilhelmsson, And J. G. Mattsson . 2003. Phylogeny Of Dictyocaulus (Lungworms) From Eight Species Of Ruminants Based On Analyses Of Ribosomal Rna Data. Parasitology 127:179–187. [CrossRef]

- R.B. Gasser, A. Jabbar, N. Mohandas, J. Höglund, R.S. Hall, D.T.J. Littlewood, A.R. Jex. Assessment Of The Genetic Relationship Between Dictyocaulus Species From Bos Taurus And Cervus Elaphus Using Complete Mitochondrial Genomic Datasets. Parasites Vectors, 5 (2012), P. 241. [CrossRef]

- Pyziel, A. M., Laskowski, Z., Klich, D., Demiaszkiewicz, A. W., Kaczor, S., Merta, D., Kobielski, J., Nowakowska, J., Anusz, K., & Höglund, J. (2023). Distribution of large lungworms (Nematoda: Dictyocaulidae) in free-roaming populations of red deer Cervus elaphus (L.) with the description of Dictyocaulus skrjabini n. sp. Parasitology, 150(10), 956-966. [CrossRef]

- Chilton, N. B., Huby-Chilton, F., Gasser, R. B., & Beveridge, I. (2006). The evolutionary origins of nematodes within the order Strongylida are related to predilection sites within hosts. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 40(1), 118-128. [CrossRef]

- Cafiso, M. Castelli, P. Tedesco, G. Poglayen, C. Buccheri-Pederzoli, S. Robetto, R. Orusa, L. Corlatti, C. Bazzocchi, C. Luzzago. Molecular Characterization Of Dictyocaulus Nematodes In Wild Red Deer Cervus Elaphus In Two Areas Of The Italian Alps. Parasitol. Res., 122 (2023), Pp. 881-887. [CrossRef]

- D. Jenkins, A. Baker, M. Porter, S. Shamsi, D.P. Barton. Wild Fallow Deer (Dama Dama) As Definitive Hosts Of Fasciola Hepatica (Liver Fluke) In Alpine New South Wales. Aust. Vet. J., 98 (2020), Pp. 546-549. [CrossRef]

- J. Lamb, E. Doyle, J. Barwick, M. Chambers, L. Kakhn. Prevalence And Pathology Of Liver Fluke (Fasciola Hepatica) In Fallow Deer (Dama Dama). Vet. Parasitol., 293 (2021), Article 109427. [CrossRef]

- Jarrett, W. F. H., Jennings, F. W., Mcintyre, W. I. M., Mulligan, W., Thomas, B. A. C., Y Urquhart, G. M. (1959). Immunological Studies On Dictyocaulus Viviparus Infection. Immunology, 2(3), 252-261.

- Jarrett, W. F. H., Y Sharp, N. C. C. (1963). Vaccination Against Parasitic Disease: Reactions In Vaccinated And Immune Hosts In Dictyocaulus Viviparus Infection. The Journal Of Parasitology, 49(2), 177-189. [CrossRef]

- Claerebout, E., Y Geldhof, P. (2020). Helminth Vaccines In Ruminants: From Development To Application. Veterinary Clinics: Food Animal Practice, 36(1), 159-171. [CrossRef]

- Molina, V. M., Arbeláez, J. M., Prada, J. A., Blanco, R. D., Y Oviedo, C. A. (2016). Posible Resistencia De Dictyocaulus Viviparus Al Fenbendazol En Un Bovino. Revista De La Facultad De Medicina Veterinaria Y De Zootecnia, 63(1), 54-63. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, P., Forbes, A., Mcintyre, J., Bartoschek, T., Devine, K., O’neill, K., Laing, R., Y Ellis, K. (2024). Inefficacy Of Ivermectin And Moxidectin Treatments Against Dictyocaulus Viviparus In Dairy Calves. Veterinary Record, E4265. [CrossRef]

- R.A. Mckenzie, P.E. Green, A.M. Thornton, Y.S. Chung, A.R. Mackenzie, D.H. Cybinski, T.D. St George. Diseases Of Deer In South Eastern Queensland Aust. Vet. J., 62 (1985), P. 424. G.E. Mylrea, R.C. Mulley, A.W. English Gastrointestinal Helminths In Fallow Deer (Dama Dama) And Their Response To Treatment With Anthelminthics. Aust. Vet. J., 68 (1991), Pp. 74-75.

- G.E. Mylrea, R.C. Mulley, A.W. English. Gastrointestinal Helminths In Fallow Deer (Dama Dama) And Their Response To Treatment With Anthelminthics. Aust. Vet. J., 68 (1991), Pp. 74-75.

- Habela Martínez-Estéllez, M. Á., Moreno Casero, A. M., Peña, J., Montes, G., Gómez Carmona, J. M., Y Hermoso De Mendoza Salcedo, J. (2006). Parásitos Asociados A Tuberculosis En Ciervos (Cervus Elaphus) De Extremadura. Xxxi Jornadas Científicas Y X Internacionales De La Sociedad Española De Ovinotecnia Y Caprinotecnia (Seoc): Zamora, 20-22 De Septiembre De 2006, 2006, Isbn 84-934535-8-7, Págs. 337-339, 337 339. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=8691504.

- A.M. Pyziel, Z. Laskowski, J. Höglund. Development Of Amultiplex Pcr For Identification Of Dictyocaulus Lungworms In Domestic And Wild Ruminants. Parasitol. Res., 114 (2015), Pp. 3923-3926. [CrossRef]

- P. Halvarsson, P. Baltrušis, P. Kjellander, J. Höglund.Parasitic Strongyle Nemabiome Communities In Wild Ruminants In Sweden. Parasites Vectors, 15 (2022), P. 341. [CrossRef]

- Bangoura, B., Brinegar, B., & Creekmore, T. E. (2020). DICTYOCAULUS CERVI-LIKE LUNGWORM INFECTION IN A ROCKY MOUNTAIN ELK (CERVUS CANADENSIS NELSONI) FROM WYOMING, USA. Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 57(1), 71-81. [CrossRef]

- Pato Rivero, F. J. (2012). Estudio Epidemiológico De Las Infecciones Que Afectan Al Aparato Respiratorio Y Gastrointestinal De Los Corzos En Galicia [Tesis Doctoral]. https://minerva.usc.es/xmlui/handle/10347/3700.

- Miller, S. A., Dykes, D. D., Y Polesky, H. F. (1988). A Simple Salting Out Procedure For Extracting Dna From Human Nucleated Cells. Nucleic Acids Research, 16(3), 1215.

- Bowles, J., Blair, D., Y Mcmanus, D. P. (1992). Genetic Variants Within The Genus Echinococcus Identified By Mitochondrial Dna Sequencing. Molecular And Biochemical Parasitology, 54(2), 165-173. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. X., Y Hewitt, G. M. (1997). Assessment Of The Universality And Utility Of A Set Of Conserved Mitochondrial Coi Primers In Insects. Insect Molecular Biology, 6(2), 143 150. [CrossRef]

- Wollan, G. T., & Quevedo, E. M. (2024). Molecular Methods Used to Identify a New Species of Dictyocaulus (Family Dictyocaulidae) in White-Tailed Deer.

- Rozas Liras, J. A., Librado Sanz, P., Sánchez Del Barrio, J. C., Messeguer Peypoch, X., Y Rozas, R. (2010). Dnasp Version 5. Dna Sequence Polymorphism. Programari (Genètica, Microbiologia I Estadística). https://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/handle/2445/53451.

- Bandelt, H. J., Forster, P., Y Röhl, A. (1999). Median-Joining Networks For Inferring Intraspecific Phylogenies. Molecular Biology And Evolution, 16(1), 37-48. [CrossRef]

- Leigh, J. W., Y Bryant, D. (2015). Popart: Full-Feature Software For Haplotype Network Construction. Methods In Ecology And Evolution, 6(9), 1110-1116. [CrossRef]

- Panadero, R., Carrillo, E. B., López, C., Dı́ez-Baños, N., Dı́ez-Baños, P., Y Morrondo, M. P. (2001). Bronchopulmonary Helminths Of Roe Deer (Capreolus Capreolus) In The 45 Northwest Of Spain. Veterinary Parasitology, 99(3), 221-229. [CrossRef]

- Borgsteede, F. H. M., Jansen, J., Van Nispen Tot Pannerden, H. P. M., Van Der Burg, W. P. J., Noorman, N., Poutsma, J., Y Kotter, J. F. (1990). Untersuchungen Über Die Helminthen-Fauna Beim Reh (Capreolus Capreolus L.) In Den Niederlanden. Zeitschrift Für Jagdwissenschaft, 36(2), 104-109. [CrossRef]

- Shimalov, V., Y Shimalov, V. (2002). Helminth Fauna Of Cervids In Belorussian Polesie. Parasitology Research, 89(1), 75-76. [CrossRef]

- Pyziel, A. M., Dolka, I., Werszko, J., Laskowski, Z., Steiner-Bogdaszewska, Ż., Wiśniewski, J., Demiaszkiewicz, A. W., Y Anusz, K. (2018). Pathological Lesions In The Lungs Of Red Deer Cervus Elaphus (L.) Induced By A Newly-Described Dictyocaulus Cervi (Nematoda: Trichostrongyloidea). Veterinary Parasitology, 261, 22-26. [CrossRef]

- Hugonnet, L., Y Cabaret, J. (1987). Infection Of Roe-Deer In France By The Lung Nematode, Dictyocaulus Eckerti Skrjabin, 1931 (Trichostrongyloidea): Influence Of Environmental Factors And Host Density. Journal Of Wildlife Diseases, 23(1), 109-112. [CrossRef]

- Dacal, V., Vázquez, L., Pato, F. J., Cienfuegos, S., Panadero-Fontán, R., López Sández, C., Y Morrondo, P. (2010). Cambios En La Capacidad Pulmonar En Corzos (Capreolus Capreolus) Del Noroeste De España Infectados Por Nematodos Broncopulmonares. Galemys 22, 22, 233-242. [CrossRef]

- Kuzmina, T., Kharchenko, V., Y Malega, A. (2010). Helminth Fauna Of Roe Deer (Capreolus Capreolus) In Ukraine: Biodiversity And Parasite Community. Vestnik Zoologii, 44(1), E-12-E-19. [CrossRef]

- Handeland, K., Davidson, R. K., Viljugrein, H., Mossing, A., Meisingset, E. L., Heum, M., Strand, O., Y Isaksen, K. (2019). Elaphostrongylus And Dictyocaulus Infections In Norwegian Wild Reindeer And Red Deer Populations In Relation To Summer Pasture Altitude And Climate. International Journal For Parasitology: Parasites And Wildlife, 10, 188-195. [CrossRef]

- Stoican, E.; Olteanu, G. (1959). Beitriige Zum Studium Der Helminthofauna Des Rehes (C. Capreolus) In Rumiinien. Probleme Der Parazitologie, 7: 38-46.

- Llada, I. M., Gianechini, L. S., Lloberas, M. M., Morrell, E. L., Odriozola, E. R., Y Cantón, G. J. (2020). Dictiocaulosis En Vacas De Cría En La Provincia De Buenos Aires, Argentina: Descripción De Dos Brotes. Analecta Veterinaria, 40(1). https://revistas.unlp.edu.ar/analecta/article/download/9495/9286?inline=1#redalyc_2 51357005_ref2.

- Mahmood, F., Khan, A., Hussain, R., Y Anjum, M. S. (2011). Prevalence And Pathology Of Dictyocaulus Viviparus Infection In Cattle And Buffaloes. Veterinary Record, 169(19), 494-494. [CrossRef]

- Keira Brown, David J. Jenkins, Alexander W. Gofton, Ina Smith, Nidhish Francis, Shokoofeh Shamsi, Diane P. Barton, The First Finding Of Dictyocaulus Cervi And Dictyocaulus Skrjabini (Nematoda) In Feral Fallow Deer (Dama Dama) In Australia, International Journal For Parasitology: Parasites And Wildlife, Volume 24, 2024, 100953. Issn 2213-2244. [CrossRef]

- Pyziel, A. M., Laskowski, Z., Dolka, I., Kołodziej-Sobocińska, M., Nowakowska, J., Klich, D., Bielecki, W., Żygowska, M., Moazzami, M., Anusz, K., & Höglund, J. (2020). Large lungworms (Nematoda: Dictyocaulidae) recovered from the European bison may represent a new nematode subspecies. International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife, 13, 213-220. [CrossRef]

- H.A. Danks, C. Sobotyk, M.N. Saleh, M. Kulpa, J.L. Luksovsky, L.C. Kones, G.G. Verocai. Opening A Can Of Lungworms: Molecular Characterization Of Dictyocaulus (Nematoda: Dictyocaulidae) Infecting North American Bison (Bison Bison). Int. J. Parasitol.: Parasites And Wildlife, 18 (2022), Pp. 128-134. [CrossRef]

- Molento, M. B., Depner, R. A., & Mello, M. H. A. (2006). Suppressive treatment of abamectin against Dictyocaulus viviparus and the occurrence of resistance in first-grazing-season calves. Veterinary Parasitology, 141(3), 373-376. [CrossRef]

- Blanc-Mathieu, R., Perfus-Barbeoch, L., Aury, J.-M., Rocha, M. D., Gouzy, J., Sallet, E., Martin-Jimenez, C., Bailly-Bechet, M., Castagnone-Sereno, P., Flot, J.-F., Kozlowski, D. K., Cazareth, J., Couloux, A., Silva, C. D., Guy, J., Kim-Jo, Y.-J., Rancurel, C., Schiex, T., Abad, P., … Danchin, E. G. J. (2017). Hybridization And Polyploidy Enable Genomic Plasticity Without Sex In The Most Devastating Plant-Parasitic Nematodes. Plos Genetics, 13(6), E1006777. [CrossRef]

| Name | Location | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Cuadrillas Bajas | Cedillo | 21/09/23 |

| San Fermín | Torrejón el Rubio | 03/12/23 |

| Sierra Palomares | Alía | 27/01/24 |

| Jabalina | Salorino | 02/02/24 |

| Valdelayegua | Aliseda | 09/02/24 |

| Cerro Verde | Carbajo | 11/02/24 |

| El Águila | Serradilla | 17/02/24 |

| Lungs | Location | Macroscopic | Microscopic | Adult number |

| Deer 1 | Carrillas | + | + | 4 |

| Deer 2 | Carrillas | - | + | |

| Deer 3 | Carrillas | - | - | |

| Deer 4 | Carrillas | - | - | |

| Deer 5 | Carrillas | - | - | |

| Deer 6 | San Fermín | - | - | |

| Deer 7 | San Fermín | - | - | |

| Deer 8 | San Fermín | - | - | |

| Deer 9 | San Fermín | - | + | |

| Deer 10 | San Fermín | - | - | |

| Deer 11 | San Fermín | - | - | |

| Deer 12 | Sierrra Paloma | - | - | |

| Deer 13 | Sierrra Paloma | - | - | |

| Deer 14 | Sierrra Paloma | - | - | |

| Deer 15 | Sierrra Paloma | - | + | |

| Deer 16 | Sierrra Paloma | + | + | 8 |

| Deer 17 | Jabalina | + | + | 17 |

| Deer 18 | Jabalina | + | + | 22 |

| Deer 19 | Jabalina | - | - | |

| Deer 20 | Jabalina | - | - | |

| Deer 21 | Jabalina | - | - | |

| Deer 22 | Valdelayegua | - | - | |

| Deer 23 | Valdelayegua | - | - | |

| Deer 24 | Valdelayegua | - | - | |

| Deer 25 | Valdelayegua | - | - | |

| Deer 26 | Valdelayegua | - | - | |

| Deer 27 | Cerro Verde | - | - | |

| Deer 28 | Cerro Verde | - | - | |

| Deer 29 | Cerro Verde | - | - | |

| Deer 30 | Cerro Verde | - | - | |

| Deer 31 | Cerro Verde | + | + | 13 |

| Deer 32 | El Águila | - | - | |

| Deer 33 | El Águila | - | - | |

| Deer 34 | El Águila | - | - | |

| Deer 35 | El Águila | - | - | |

| Deer 36 | El Águila | - | - | |

| TOTAL | 5 | 8 | 64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).