Submitted:

14 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

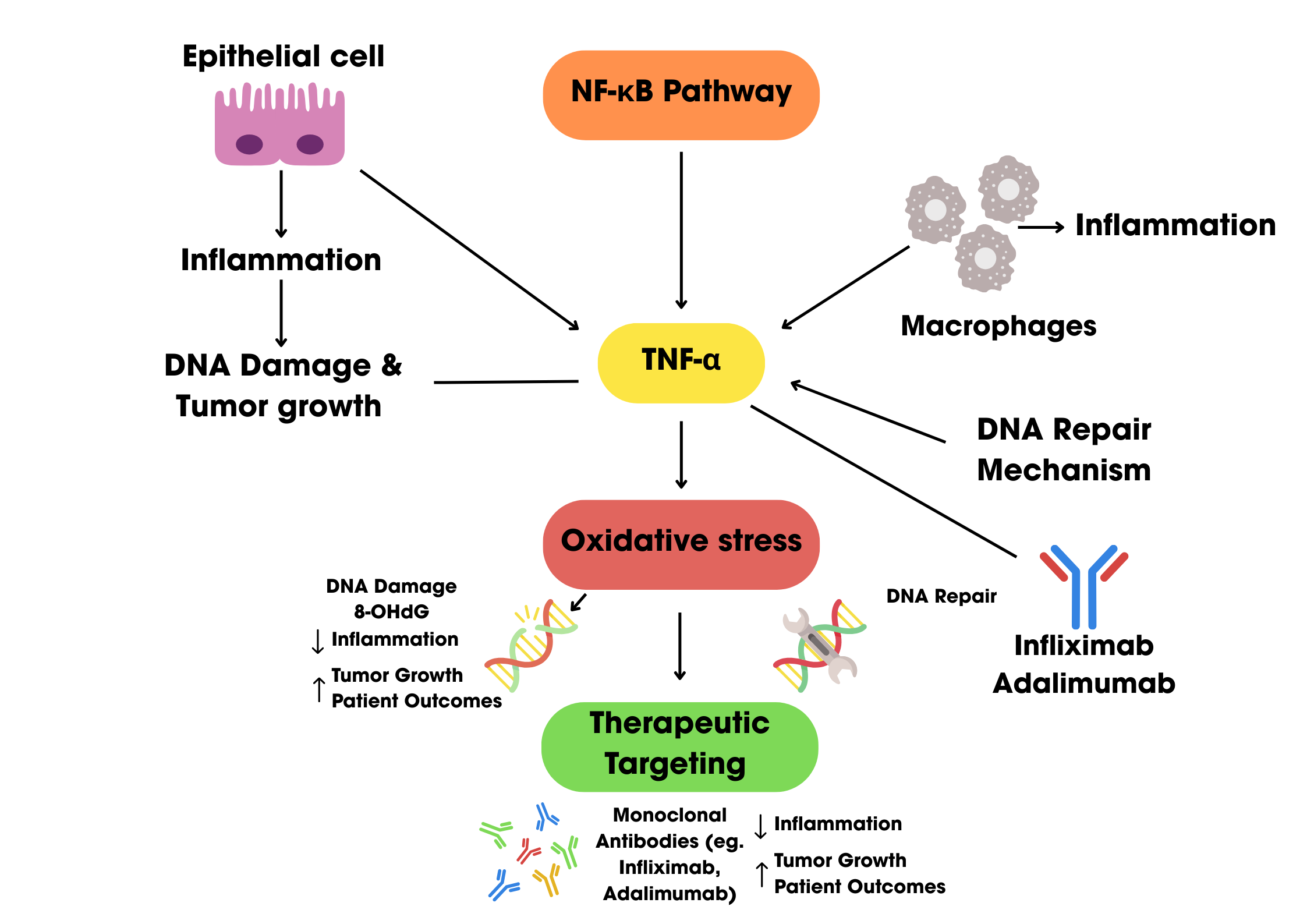

2. Role of Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha in colon cancer pathophysiology

2.1. Overview of Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-α)

2.1.1. Structure and Function of TNF-α

2.2. Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-α) and Colorectal Carcinoma

2.3. Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-α) and immune response

2.3.1. Pro-Inflammatory Role and Immune Activation

2.3.2. Immune Evasion

3. Mechanistic Insights of Pathways

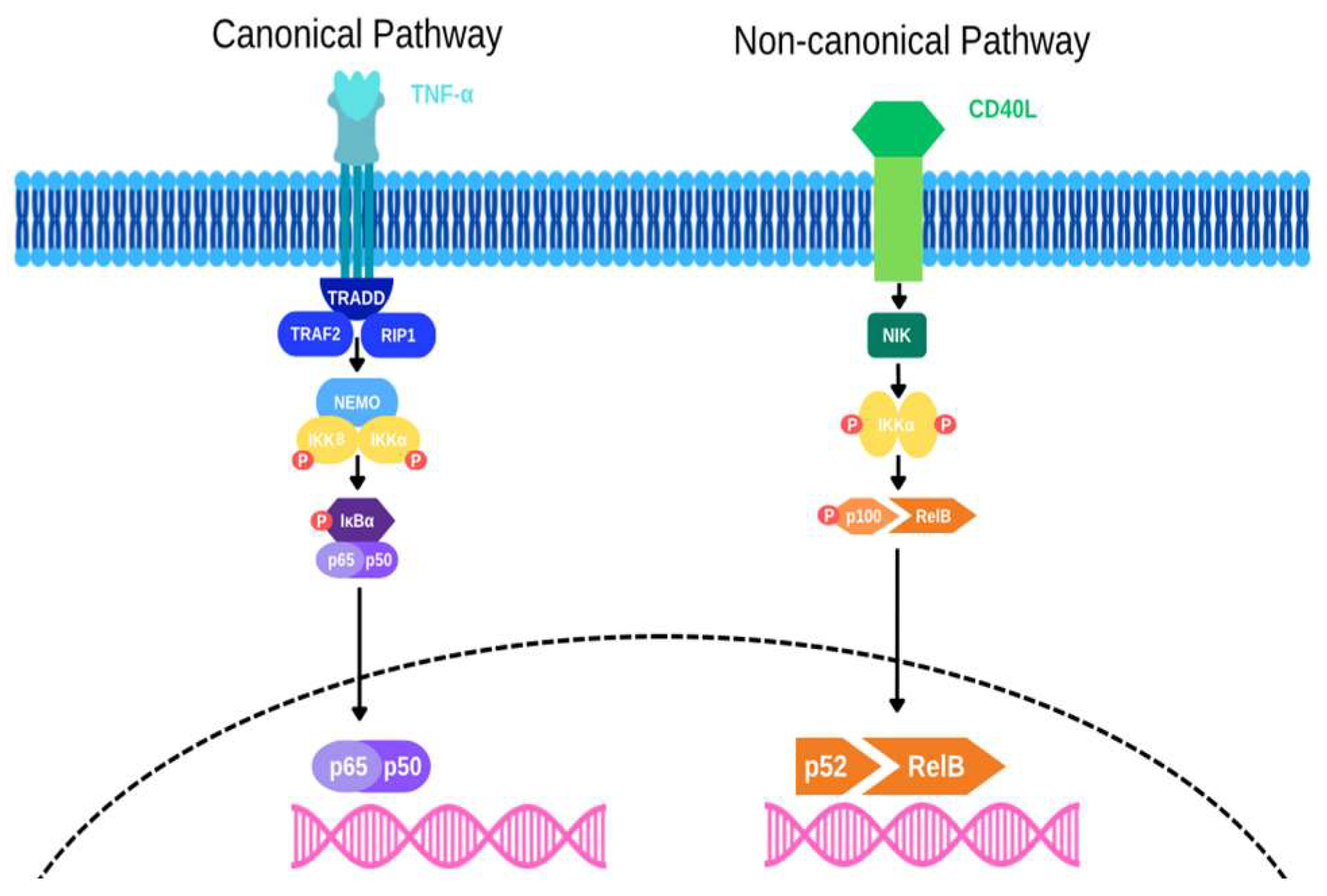

3.1. NF-κB Pathway Activation

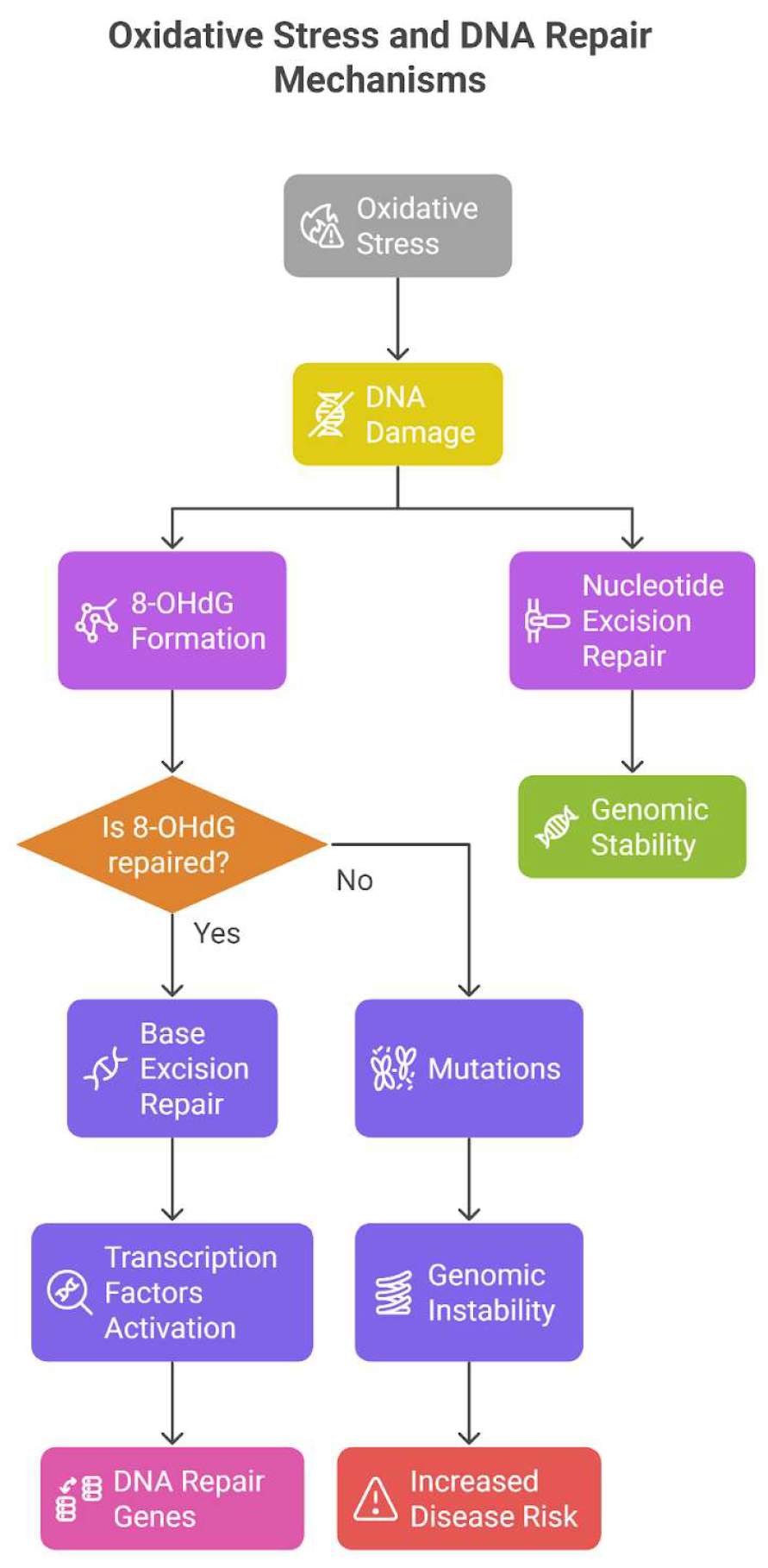

3.2. Induction of Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage

3.3. Crosstalk with Wnt/β-catenin and STAT3 signaling Pathways

4. TNF-α as a therapeutic Target in Colon cancer

5. Limitations and future direction

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| Stat3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| CRC | Colorectal Cancer |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| Wnt | Wingless-Type |

| EMT | Epithelial mesenchymal transition |

| TNFR1 | TNF-α type 1 receptor |

| TNFR2 | TNF-α type 2 receptor |

| HT-29 | Human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line |

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| IKK | IκB kinase |

| TRAF2 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 2 |

| RIP1 | Kinase receptor interacting protein 1 |

| NEMO | Nuclear factor-kappa B Essential Modulator |

| 8-OHdG | 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine |

| GG-NER | Global Genome NER |

| DNMTs | DNA methyltransferases |

| TROP-2 | Tumor-associated calcium signal transducer 2 |

References

- Farinha, P.; Pinho, J.O.; Matias, M.; Gaspar, M.M. Nanomedicines in the treatment of colon cancer: a focus on metallodrugs. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2022, 12, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrushaid, N.; Alam Khan, F.; Al-Suhaimi, E.; Elaissari, A. Progress and Perspectives in Colon Cancer Pathology, Diagnosis, and Treatments. Diseases 2023, 11, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, A.; Pathak, S.; Subramanium, V.D.; Dharanivasan, G.; Murugesan, R.; Verma, R.S. Strategies for targeted drug delivery in treatment of colon cancer: current trends and future perspectives. Drug Discov. Today 2017, 22, 1224–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, E.; Shi, Q.; Shields, A.F.; Nixon, A.B.; Shergill, A.P.; Ma, C.; Guthrie, K.A.; Couture, F.; Kuebler, P.; Kumar, P.; et al. Association of Inflammatory Biomarkers With Survival Among Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, D.-I.; Lee, A.-H.; Shin, H.-Y.; Song, H.-R.; Park, J.-H.; Kang, T.-B.; Lee, S.-R.; Yang, S.-H. The Role of Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-α) in Autoimmune Disease and Current TNF-α Inhibitors in Therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, K.; Gu, H.; Yuan, Z.; Xu, X. Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha Signaling and Organogenesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 727075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laha, D.; Grant, R.; Mishra, P.; Nilubol, N. The Role of Tumor Necrosis Factor in Manipulating the Immunological Response of Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakdemirli, A.; Kocal, G.C. TNF-alpha Induces Pro-Inflammatory Factors in Colorectal Cancer Microenvironment. Med Sci. Discov. 2020, 7, 466–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, A.G.; Li, J.V.; Gooderham, N.J. Tumour Necrosis Factor-Alpha (TNF-α)-Induced Metastatic Phenotype in Colorectal Cancer Epithelial Cells: Mechanistic Support for the Role of MicroRNA-21. Cancers 2023, 15, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, H.-S.; Zhou, B.-H.; Li, C.-L.; Zhang, F.; Wang, X.-F.; Zhang, G.; Bu, X.-Z.; Cai, S.-H.; Du, J. Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) Induced by TNF-α Requires AKT/GSK-3β-Mediated Stabilization of Snail in Colorectal Cancer. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e56664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanilov, N.; Miteva, L.; Dobreva, Z.; Stanilova, S. Colorectal cancer severity and survival in correlation with tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2014, 28, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, W.; Wang, J.; Huang, P.; Gou, S.; Yu, D.; Zong, L. Tumor necrosis factor-α induces proliferation and reduces apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells through STAT3 activation. Immunogenetics 2023, 75, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niture, S.; Dong, X.; Arthur, E.; Chimeh, U.; Niture, S.S.; Zheng, W.; Kumar, D. Oncogenic Role of Tumor Necrosis Factor α-Induced Protein 8 (TNFAIP8). Cells 2018, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-M.; Su, J.-R.; Yan, S.-P.; Cheng, Z.-L.; Yang, T.-T.; Zhu, Q. A novel inflammatory regulator TIPE2 inhibits TLR4-mediated development of colon cancer via caspase-8. Cancer Biomarkers 2014, 14, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Obeed, O.A.; Alkhayal, K.A.; Al Sheikh, A.; Zubaidi, A.M.; Vaali-Mohammed, M.-A.; Boushey, R.; McKerrow, J.H.; Abdulla, M.-H. Increased expression of tumor necrosis factor-α is associated with advanced colorectal cancer stages. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 18390–18396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgos-Molina, A.M.; Santana, T.T.; Redondo, M.; Romero, M.J.B. The Crucial Role of Inflammation and the Immune System in Colorectal Cancer Carcinogenesis: A Comprehensive Perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meckawy, G.R.; Mohamed, A.M.; Zaki, W.K.; Khattab, M.A.; Amin, M.M.; ElDeeb, M.A.; El-Najjar, M.R.; Safwat, N.A. Natural killer NKG2A and NKG2D in patients with colorectal cancer. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2019, 10, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; You, Q.; Wang, X. Association Between Polymorphism of the Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha-308 Gene Promoter and Colon Cancer in the Chinese Population. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomarkers 2011, 15, 743–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminska, J.; Nowacki, M.; Kowalska, M.; Rysinska, A.; Chwalinski, M.; Fuksiewicz, M.; Michalski, W.; Chechlinska, M. Clinical Significance of Serum Cytokine Measurements in Untreated Colorectal Cancer Patients: Soluble Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor Type I – An Independent Prognostic Factor. Tumor Biol. 2005, 26, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemik, O.; Sumer, A.; Kemik, A.S.; Hasirci, I.; Purisa, S.; Dulger, A.C.; Demiriz, B.; Tuzun, S. The relationship among acute-phase response proteins, cytokines and hormones in cachectic patients with colon cancer. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2010, 8, 85–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babic, A.; Shah, S.M.; Song, M.; Wu, K.; A Meyerhardt, J.; Ogino, S.; Yuan, C.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Chan, A.T.; Stampfer, M.J.; et al. Soluble tumour necrosis factor receptor type II and survival in colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 114, 995–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, A.T.; Ogino, S.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Fuchs, C.S. Inflammatory Markers Are Associated With Risk of Colorectal Cancer and Chemopreventive Response to Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Gastroenterology 2011, 140, 799–808.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapitanović, S.; Čačev, T.; Ivković, T.C.; Lončar, B.; Aralica, G. TNFα gene/protein in tumorigenesis of sporadic colon adenocarcinoma. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2014, 97, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, P.; Zhang, Z. TNF-α promotes colon cancer cell migration and invasion by upregulating TROP-2. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 3820–3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xu, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, R. Oxaliplatin and Infliximab Combination Synergizes in Inducing Colon Cancer Regression. Med Sci. Monit. 2017, 23, 780–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, M.; Lazariotou, M.; Kircher, S.; Höfelmayr, A.; Germer, C.T.; von Rahden, B.H.A.; Waaga-Gasser, A.M.; Gasser, M. Tumor necrosis factor-α is associated with positive lymph node status in patients with recurrence of colorectal cancer—indications for anti-TNF-α agents in cancer treatment. Cell. Oncol. 2011, 34, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Xie, F.; Liu, X.; Ke, S.; Chen, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, N.; Wang, Z.; Yi, G.; Shen, Y.; et al. Blockade of TNF-α/TNFR2 signalling suppresses colorectal cancer and enhances the efficacy of anti-PD1 immunotherapy by decreasing CCR8+T regulatory cells. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Bai, L.; Chen, W.; Xu, S. The NF-κB activation pathways, emerging molecular targets for cancer prevention and therapy. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2010, 14, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.; Vargas, J.; Hoffmann, A. Signaling via the NFκB system. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2016, 8, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Baeuerle, P.; Henkel, T. Function and Activation of NF-kappaB in the Immune System. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1994, 12, 141–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.A.; Nisar, S.; Singh, M.; Ashraf, B.; Masoodi, T.; Prasad, C.P.; Sharma, A.; Maacha, S.; Karedath, T.; Hashem, S.; et al. Cytokine- and chemokine-induced inflammatory colorectal tumor microenvironment: Emerging avenue for targeted therapy. Cancer Commun. 2022, 42, 689–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinatizadeh, M.R.; Schock, B.; Chalbatani, G.M.; Zarandi, P.K.; Jalali, S.A.; Miri, S.R. The Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NF-kB) signaling in cancer development and immune diseases. Genes Dis. 2020, 8, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Boiti, A.; Vallone, D.; Foulkes, N.S. Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling and Oxidative Stress: Transcriptional Regulation and Evolution. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaunig, J.E.; Kamendulis, L.M.; Hocevar, B.A. Oxidative Stress and Oxidative Damage in Carcinogenesis. Toxicol. Pathol. 2009, 38, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jridi, I.; Canté-Barrett, K.; Pike-Overzet, K.; Staal, F.J.T. Inflammation and Wnt Signaling: Target for Immunomodulatory Therapy? Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragoso, M.A.; Patel, A.K.; Nakamura, R.E.I.; Yi, H.; Surapaneni, K.; Hackam, A.S. The Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway Cross-Talks with STAT3 Signaling to Regulate Survival of Retinal Pigment Epithelium Cells. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e46892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-J.; Kang, H.-G.; Kim, K.; Kim, H.; Zetterberg, F.; Park, Y.S.; Cho, H.-S.; Hewitt, S.M.; Chung, J.-Y.; Nilsson, U.J.; et al. Crosstalk between WNT and STAT3 is mediated by galectin-3 in tumor progression. Gastric Cancer 2021, 24, 1050–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawada, M.; Seno, H.; Uenoyama, Y.; Sawabu, T.; Kanda, N.; Fukui, H.; Shimahara, Y.; Chiba, T. Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription 3 Activation Is Involved in Nuclear Accumulation of β-Catenin in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 2913–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Geng, S.; Luo, H.; Wang, W.; Mo, Y.-Q.; Luo, Q.; Wang, L.; Song, G.-B.; Sheng, J.-P.; Xu, B. Signaling pathways involved in colorectal cancer: pathogenesis and targeted therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Ai, F.; Tian, L.; Liu, S.; Zhao, L.; Wang, X. Infliximab enhances the therapeutic effects of 5-fluorouracil resulting in tumor regression in colon cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2016, ume 9, 5999–6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zins, K.; Abraham, D.; Sioud, M.; Aharinejad, S. Colon Cancer Cell–Derived Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Mediates the Tumor Growth–Promoting Response in Macrophages by Up-regulating the Colony-Stimulating Factor-1 Pathway. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 1038–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, R.C.; Mercurio, A.M. Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Stimulates the Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition of Human Colonic Organoids. Mol. Biol. Cell 2003, 14, 1790–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zidi, I.; Mestiri, S.; Bartegi, A.; Ben Amor, N. TNF-α and its inhibitors in cancer. Med Oncol. 2009, 27, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Totzke, J.; Gurbani, D.; Raphemot, R.; Hughes, P.F.; Bodoor, K.; Carlson, D.A.; Loiselle, D.R.; Bera, A.K.; Eibschutz, L.S.; Perkins, M.M.; et al. Takinib, a Selective TAK1 Inhibitor, Broadens the Therapeutic Efficacy of TNF-α Inhibition for Cancer and Autoimmune Disease. Cell Chem. Biol. 2017, 24, 1029–1039.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.M.; Smith, A.S.; Oslob, J.D.; Flanagan, W.M.; Braisted, A.C.; Whitty, A.; Cancilla, M.T.; Wang, J.; Lugovskoy, A.A.; Yoburn, J.C.; et al. Small-Molecule Inhibition of TNF-. Science 2005, 310, 1022–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornista, A.M.; Giolito, M.V.; Baker, K.; Hazime, H.; Dufait, I.; Datta, J.; Khumukcham, S.S.; De Ridder, M.; Roper, J.; Abreu, M.T.; et al. Colorectal Cancer Immunotherapy: State of the Art and Future Directions. Gastro Hep Adv. 2023, 2, 1103–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Chee, C.E.; Wong, W.; Lam, R.C.; Tan, I.B.H.; Ma, B.B. Current advances in targeted therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer – Clinical translation and future directions. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2024, 125, 102700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, K.-Y.; Huang, P.-S.; Chu, P.-Y.; Nguyen, T.N.A.; Hung, H.-Y.; Hsieh, C.-H.; Wu, M.-H. Current Applications and Future Directions of Circulating Tumor Cells in Colorectal Cancer Recurrence. Cancers 2024, 16, 2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Baruch, A. Tumor Necrosis Factor α: Taking a Personalized Road in Cancer Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 903679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Zhang, Z. TNF-α promotes colon cancer cell migration and invasion by upregulating TROP-2. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 3820–3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Study design | Sample size | Objective | Findings and results | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al Obeed et al. 2014 [15] | Retrospective cohort study |

30 |

To detect TNF-α expression in CRC cells among Saudi patients and correlate it with cancer stages. | TNF-α mRNA expression was higher in colorectal cancer than in normal tissue. High expression correlated with Stage III/IV neoplasms (P = 0.004). 83% of patients showed strong TNF-α staining, while 10% showed weak and 7% were negative. | High TNF-α expression may serve as a diagnostic marker and prognostic tool for advanced CRC stages. |

| Li et al,2011 [18] | Case-sontrol study | 180 colon cancer patients and 180 control subjects | To investigate association between TNF alpha 308G/A gene polymorphism and the risk of colon cancer. | Individuals with TNF-alpha-308AA genotype had a higher risk of developing colon cancer to those with other genotypes. | The TNF-alpha-308AA genotype is associated with an increased risk of colon cancer. |

| Kaminska et al.,2005 [19] | Observational study | 157 untreated colorectal cancer patients and 50 healthy volunteers | To evaluate clinical utility of measuring cytokines and their receptors in colorectal cancer patients and assess their correlation with clinicopathological features and prognosis. | Certain cytokines and their receptors were elevated in CRC patients compared to healthy controls.specifically, soluble tumor necrosis factor type 1 levels were identified as independent prognostic factors. | Measuring serum levels of specific cytokines,particularly sTNF RI, can provide valuable prognostic information in untreated colorectal cancer patients. |

| Kemik et al.,2010 [20] | Observational study | 126 colon cancer patients and 36 controls | To analyze the association between TNF-alpha and colon cancer related cachexia other inflammatory markers, cytokines, and hormones. | TNF-alpha levels were higher in patients with colon cancer patients compared to controls | In colon cancer-related cachexia, TNF-α is an essential cytokine that promotes weight loss, systemic inflammation, and the spread of the malignancy. |

| Babic et al.,2016 [21] | Prospective cohort study | 544 CRC patients (225 males from the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study and 319 women from the Nurses' Health Study). | To investigate into the association between colorectal cancer (CRC) patients' mortality and their levels of soluble tumour necrosis factor receptor type II (sTNF-RII). | Higher sTNF-RII levels were linked to higher overall and CRC-specific death rates. The study observed that sTNF-RII, a marker of inflammation, may contribute to the development of colorectal cancer. | TNF-alpha signaling may contribute to disease progression and resistance to treatment, as elevated sTNF-RII levels are associated with poorer survival outcomes in CRC patients. |

| Chan et al.,2011 [22] | Case-control study | from a group of 32,826 women, 280 cases of colorectal cancer and 555 matched controls. | This study looks at the association between colorectal cancer (CRC) risk and plasma inflammatory markers (CRP, IL-6, and sTNFR-2) and whether using aspirin or NSAIDs has a distinct impact on CRC risk depending on the levels of inflammatory markers. | An elevated risk of colorectal cancer was linked to higher plasma levels of sTNFR-2. Following blood collection, women with elevated sTNFR-2 levels who began taking aspirin or NSAIDs had a markedly decreased risk of colorectal cancer (CRC). Aspirin/NSAID use did not significantly lower the risk of colorectal cancer in women with low sTNFR-2 levels. |

CRC risk is linked to plasma sTNFR-2 levels (but not CRP or IL-6). Women with high sTNFR-2 levels are less likely to develop colorectal cancer (CRC) when taking aspirin or NSAIDs, but not those with low levels. This implies that anti-inflammatory medications may be more beneficial for preventing colorectal cancer in specific subgroups based on inflammation indicators. |

| Kapitanovic,2014 [23] | Case control study | 91 patients with sporadic colon adenocarcinoma and 100 healthy controls | Four TNF-α promoter SNPs were examined for allelic frequencies in patients with sporadic colon adenocarcinoma in order to look into their potential significance in sporadic colon cancer susceptibility. Furthermore, to evaluate the impact of these TNF-α SNPs on TNF-α mRNA and protein expression in colon tumours as well as their possible involvement in the initiation and spread of tumours. | TNF-α mRNA expression and tumor histological grade were shown to be significantly correlated, with grade 2 and grade 3 tumors exhibiting greater expression. A strong correlation was found between the TNF-α-857 C/T genotype and elevated TNF-α mRNA expression in tumor tissue. TNF-α protein expression was detected in 78.26% of tumors; however, neither TNF-α genotypes nor clinicopathological features were associated with this expression. Although it was not statistically significant, patients with malignancies that did not have TNF-α protein lived longer. |

Although TNF-α polymorphisms are not substantially linked to an increased risk of developing sporadic colon cancer, they may contribute to the disease's progression. Tumor behavior may be impacted by the TNF-α-857 C/T genotype's influence on TNF-α mRNA expression. |

| Zhao and Zhang, 2018 [24] | Experimental study Cell Culture: HCT-116 human colon cancer cells were used. |

Involved HCT-116 colon cancer cells treated with different TNF-α concentrations. | To investigate how TNF-α regulates TROP-2 expression and its impact on colon cancer cell migration and invasion in vitro. | -TROP-2 Expression: • Increased at low TNF-α concentrations |

Low concentrations of TNF-α promote colon cancer cell migration and invasion by upregulating TROP-2. |

| Li et al,2017 [25] | Tissue Sample Analysis Study | 108 human colon cancer tissue samples. |

To evaluate the expression and prognostic sig-nificance of TNF-α in colon cancer. | High TNF-α Expression: -Observed in colon cancer tissues and cell lines. Prognostic Significance: -High TNF-α levels were associated with poorer survival and identified as an independent adverse prognosticator in colon cancer. |

TNF-α is a poor prognostic marker in colon cancer. Blocking TNF-α may improve chemotherapy efficacy, potentially benefiting colon cancer patients. |

| M. Grimm et al., 2011 [26] | In Vitro Study | 104 patients | Association between TNF-α and lymph node status in CRC patients | 94% of the patients with CRC expressed TNF-α. High TNF-α expression was significantly associated with positive lymph node stage and recurrence of the tumor. | TNF-α expression by tumor cells may be an efficient immunological escape mechanism by inflammation enhanced metastases and probably by induction of apoptosis in tumor-infiltrating CD8+ immune cells resulting in a down reg-ulation of the tumoral immune re-sponse. |

| Guo et al., 2023 [27] | In vitro study | A total of 54 CRC and 60 gastric cancer samples were analysed with immunofluores-cence staining. | Association be-tween TNF-α sig-naling suppression and enhanced an-ti-PD1 immuno-therapy | Blocking TNF-α /TNFR2 signaling in colorectal cancer cells reduces CCR8+T regulatory cells, improving the efficacy of anti-PD1 immunotherapy and potentially improving prognosis in patients with CRC and gastric cancer. | Study findings provide insights into the regulatory mecha-nisms of CCR8+ Tregs, and we propose TNFR2 as a promising therapeutic target for the treatment of CRC. |

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Biological Role of TNF-α | Plays a critical role in colon cancer progression. High expression of TNF-α correlates with poor prognosis [25,40]. |

| Mechanisms of Action | Stimulates macrophages to produce pro-tumorigenic factors such as CSF-1, VEGF-A, and MMP-2 [41]. Enhances epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), increasing invasiveness [42]. |

| Therapeutic Targeting | TNF-α is a key target in colon cancer due to its involvement in tumor-stromal interactions and inflammatory pathways. |

| Monoclonal Antibody Therapy | Infliximab (anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibody) induces antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), promoting tumor cell apoptosis [40]. |

| Combination Therapy | Synergistic effects when combined with chemotherapy agents like oxaliplatin or 5-fluorouracil, resulting in tumor regression in preclinical models [25,40]. |

| Clinical Implications | TNF-α antagonists are currently being tested in clinical trials as a part of novel treatment strategies for colon cancer. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).