Submitted:

14 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

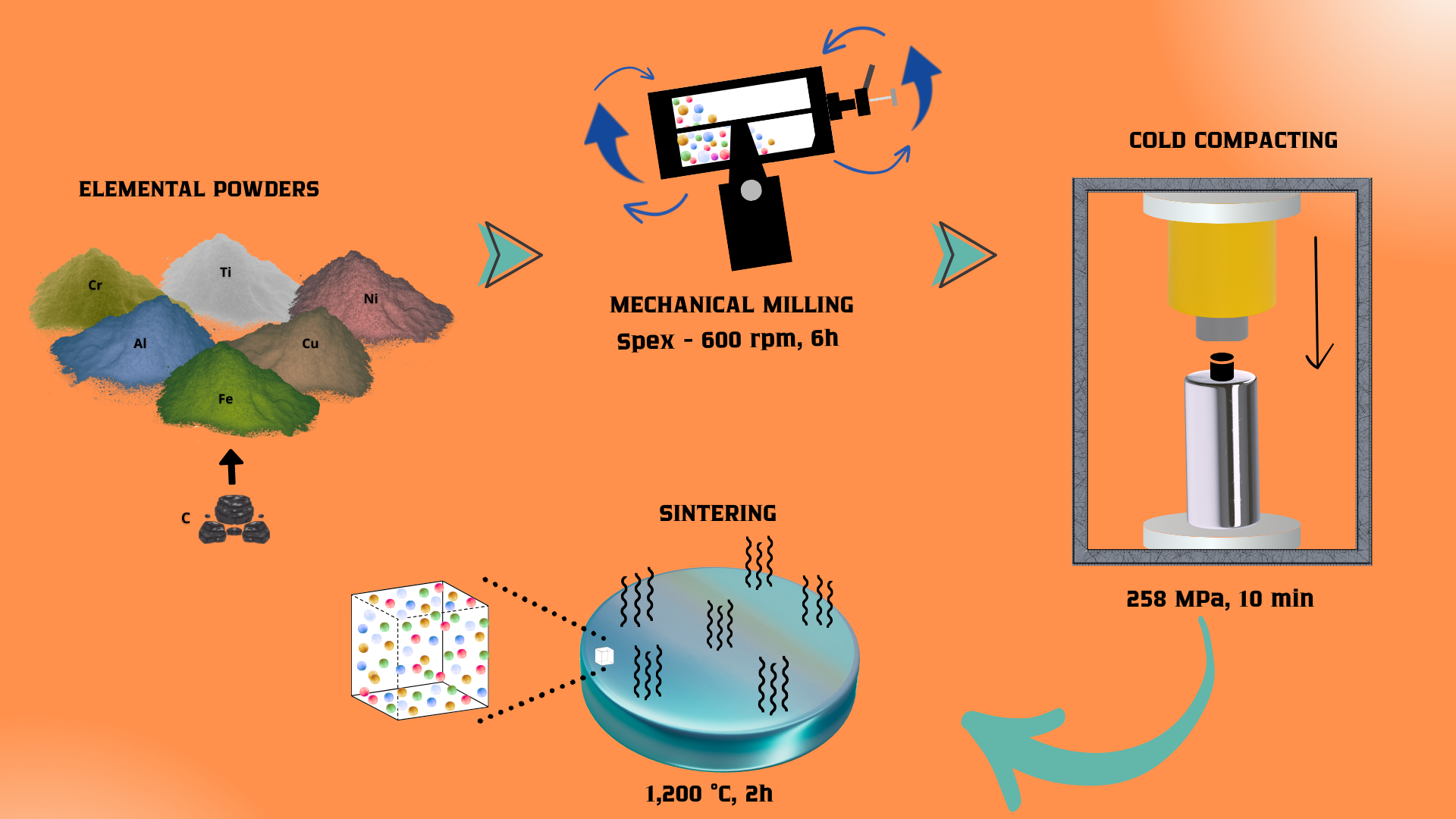

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

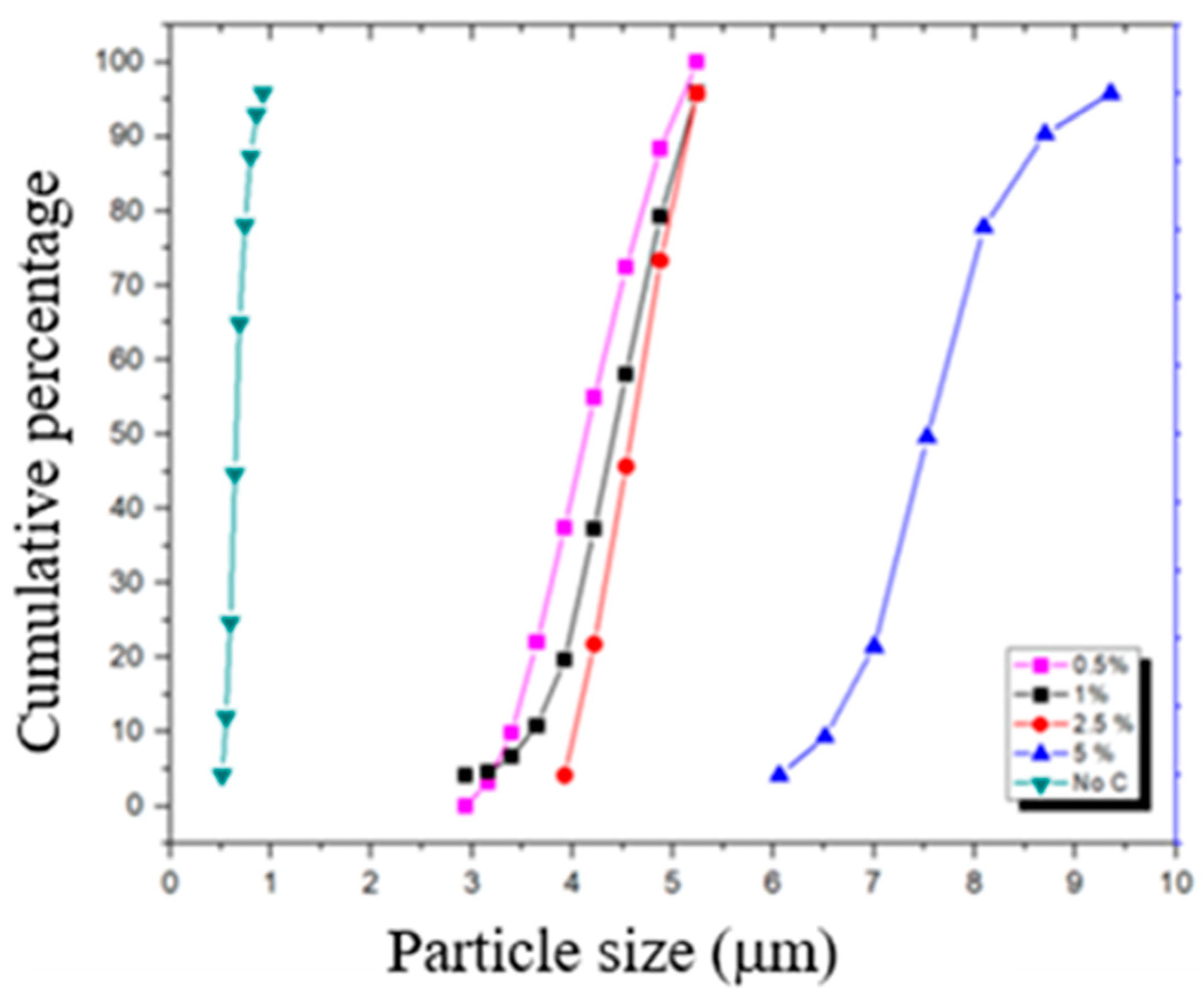

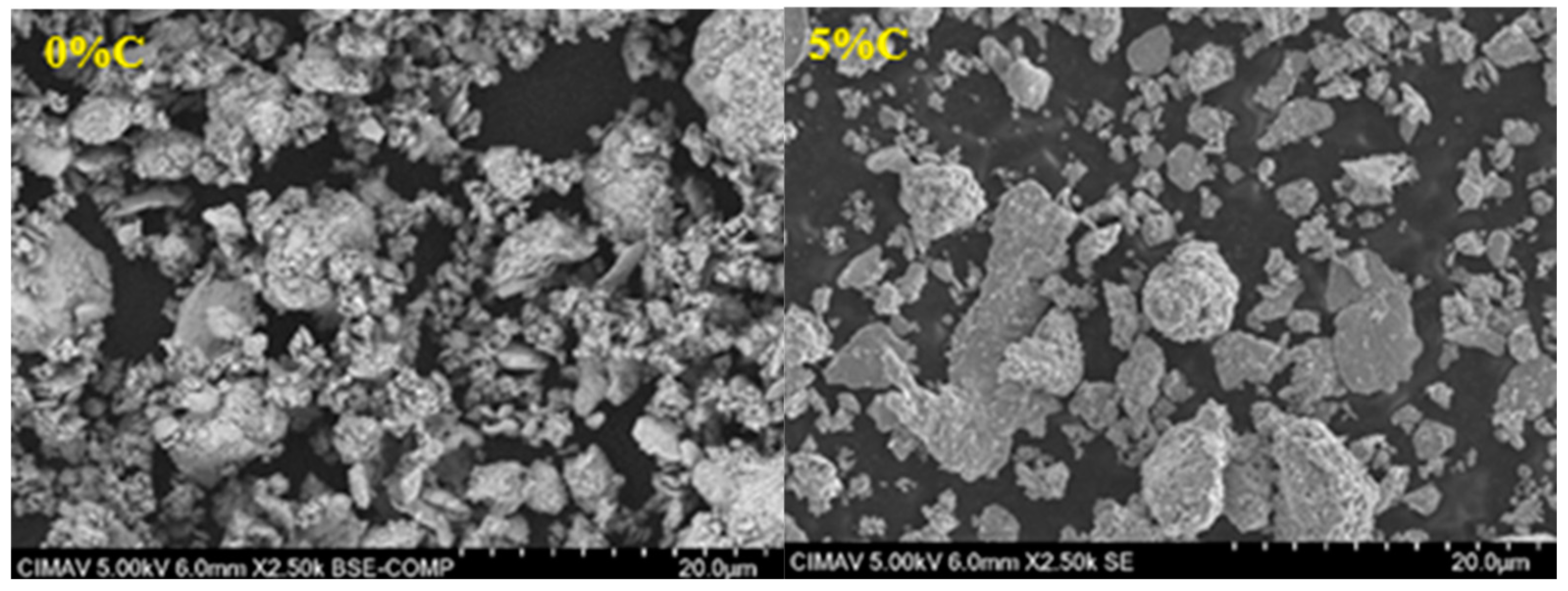

3.1. Particle Size Distribution

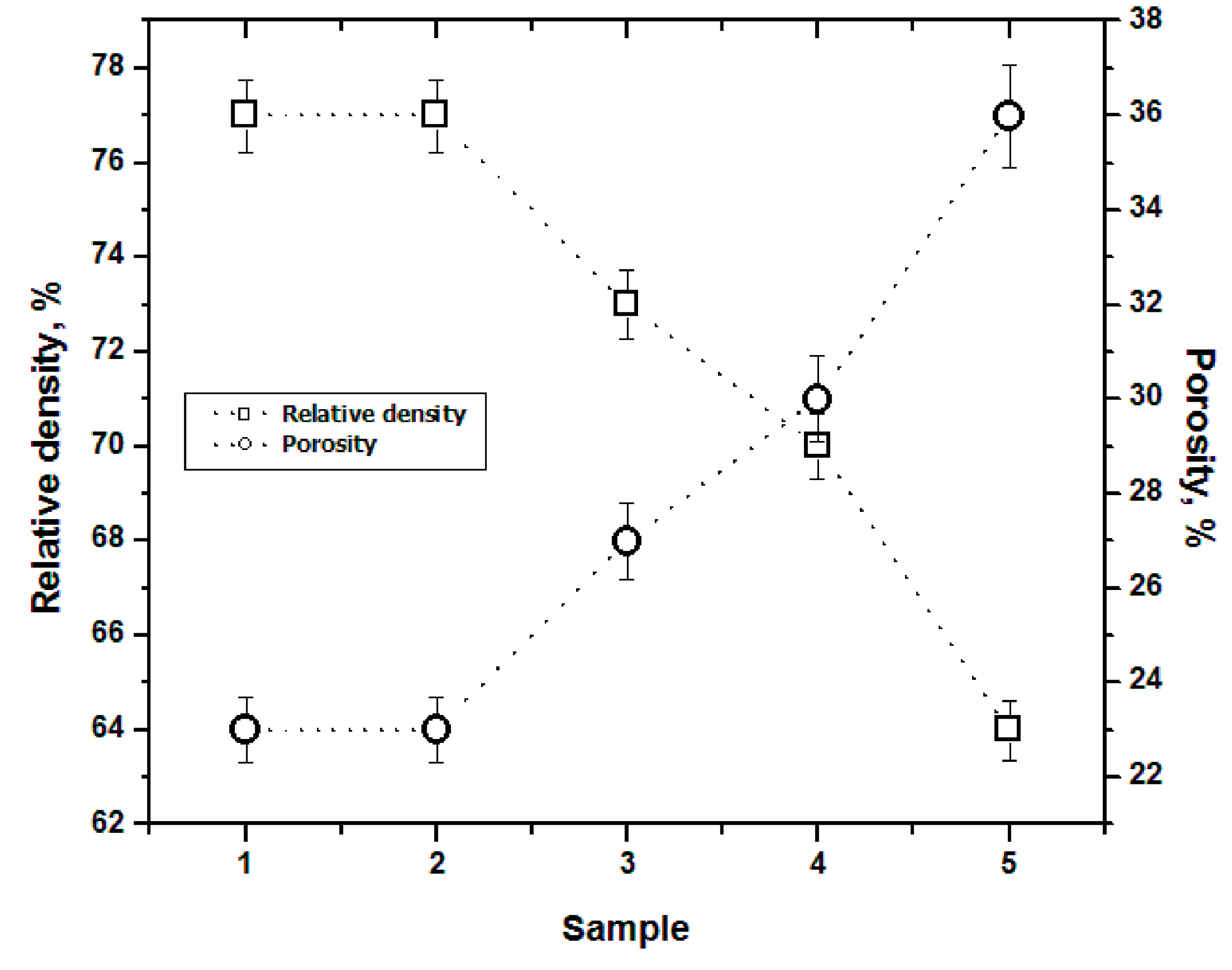

3.2. Density

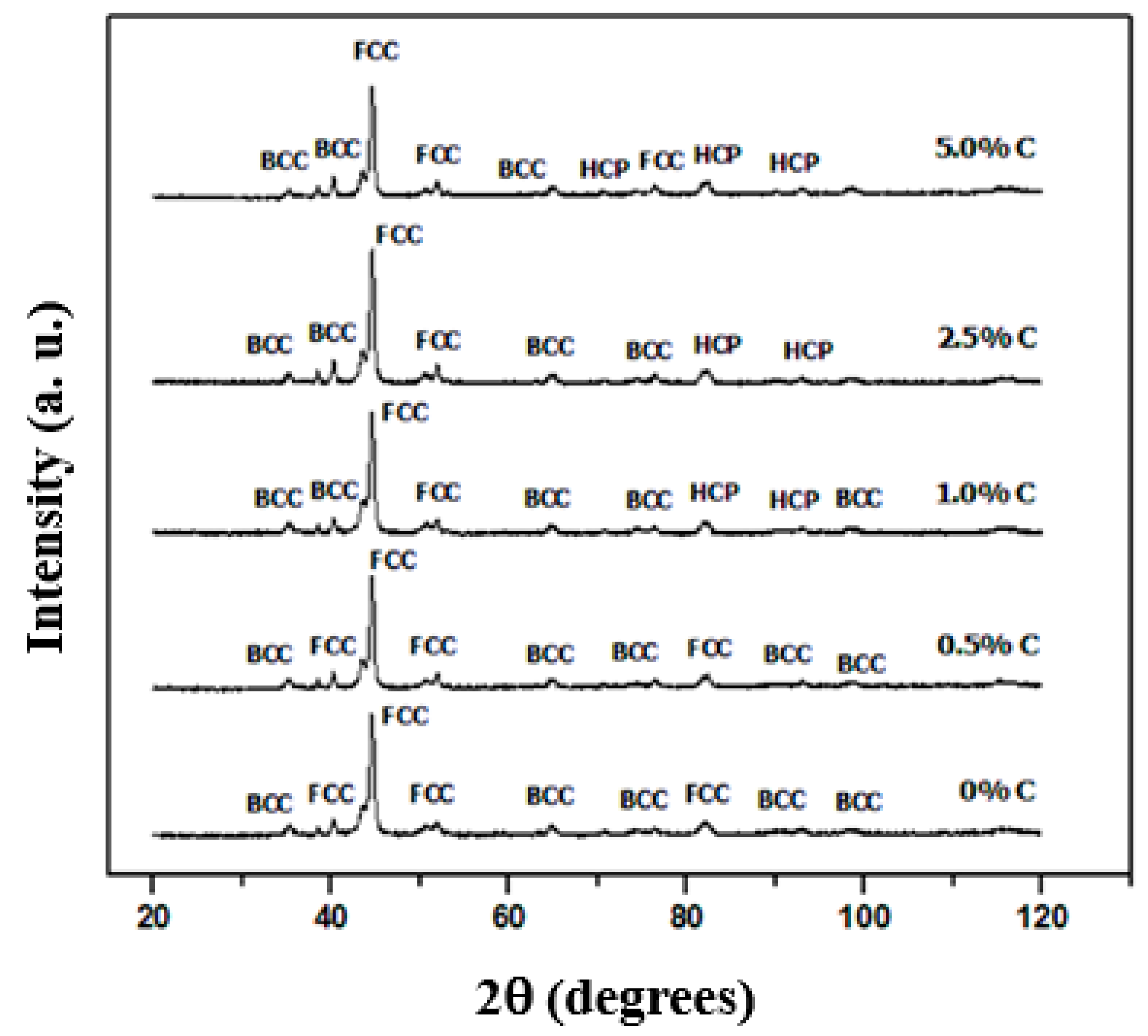

3.3. Structure

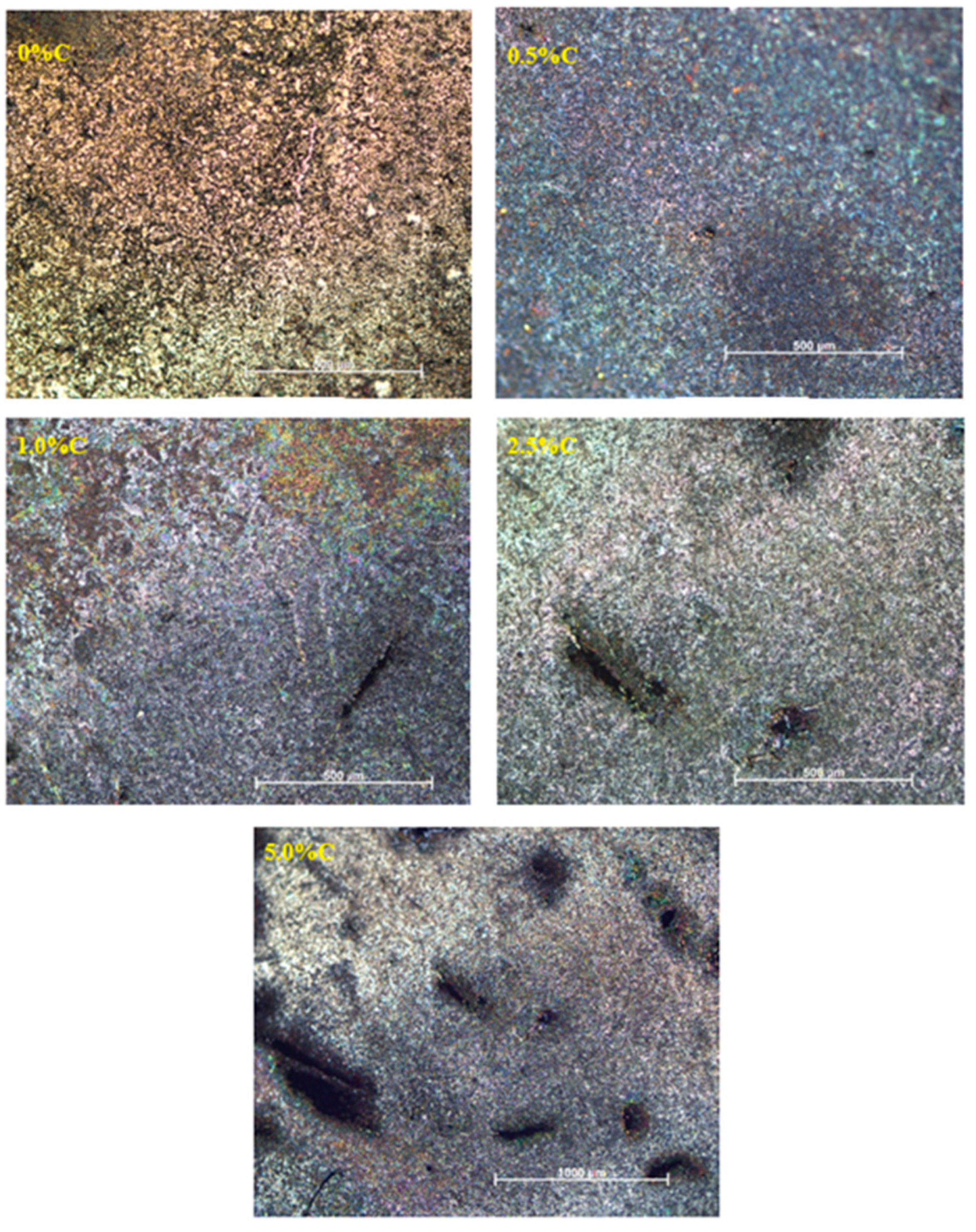

3.4. Microstructure

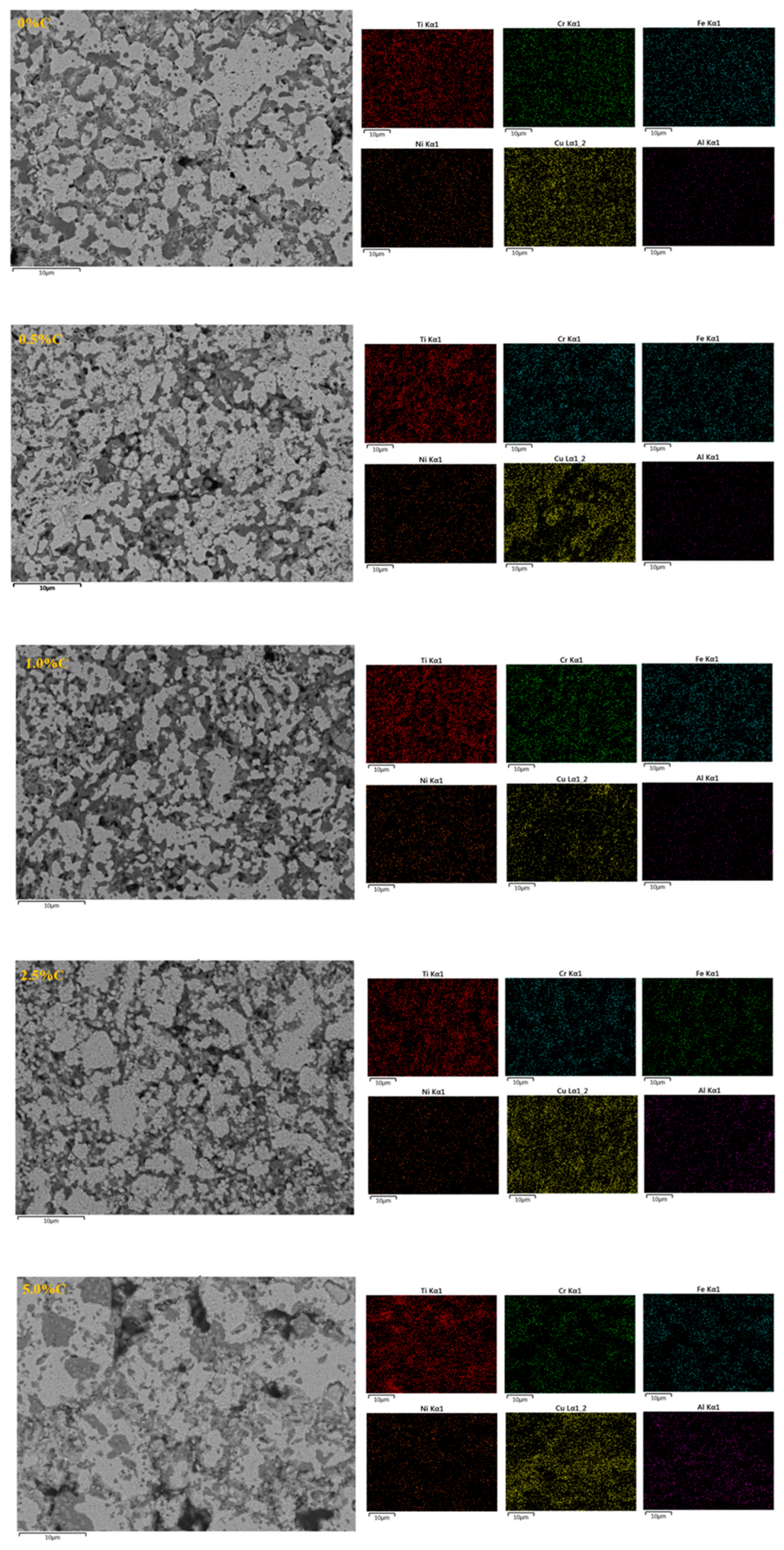

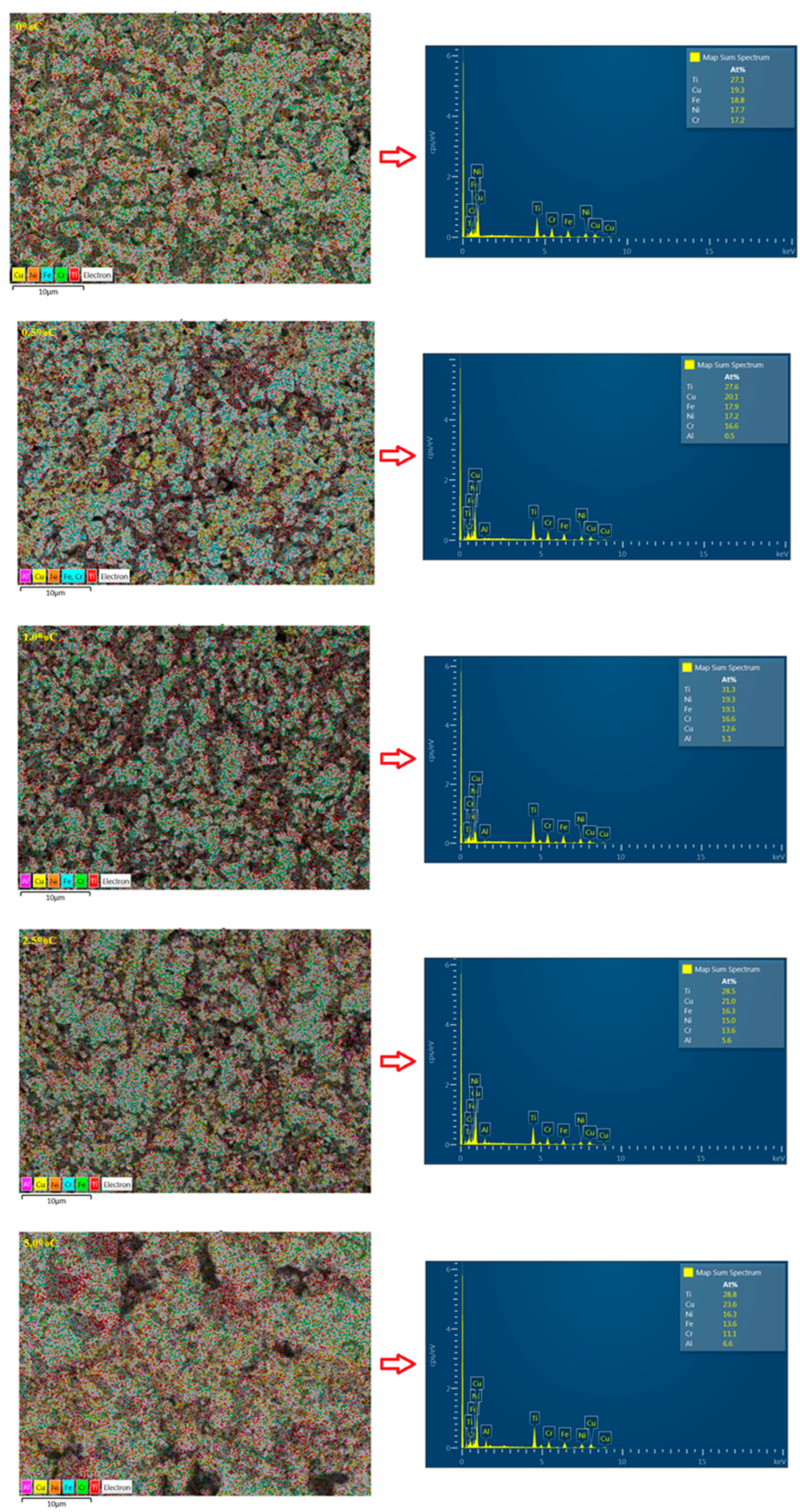

3.5. Mapping

3.6. Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDS)

3.7. Mechanical Properties

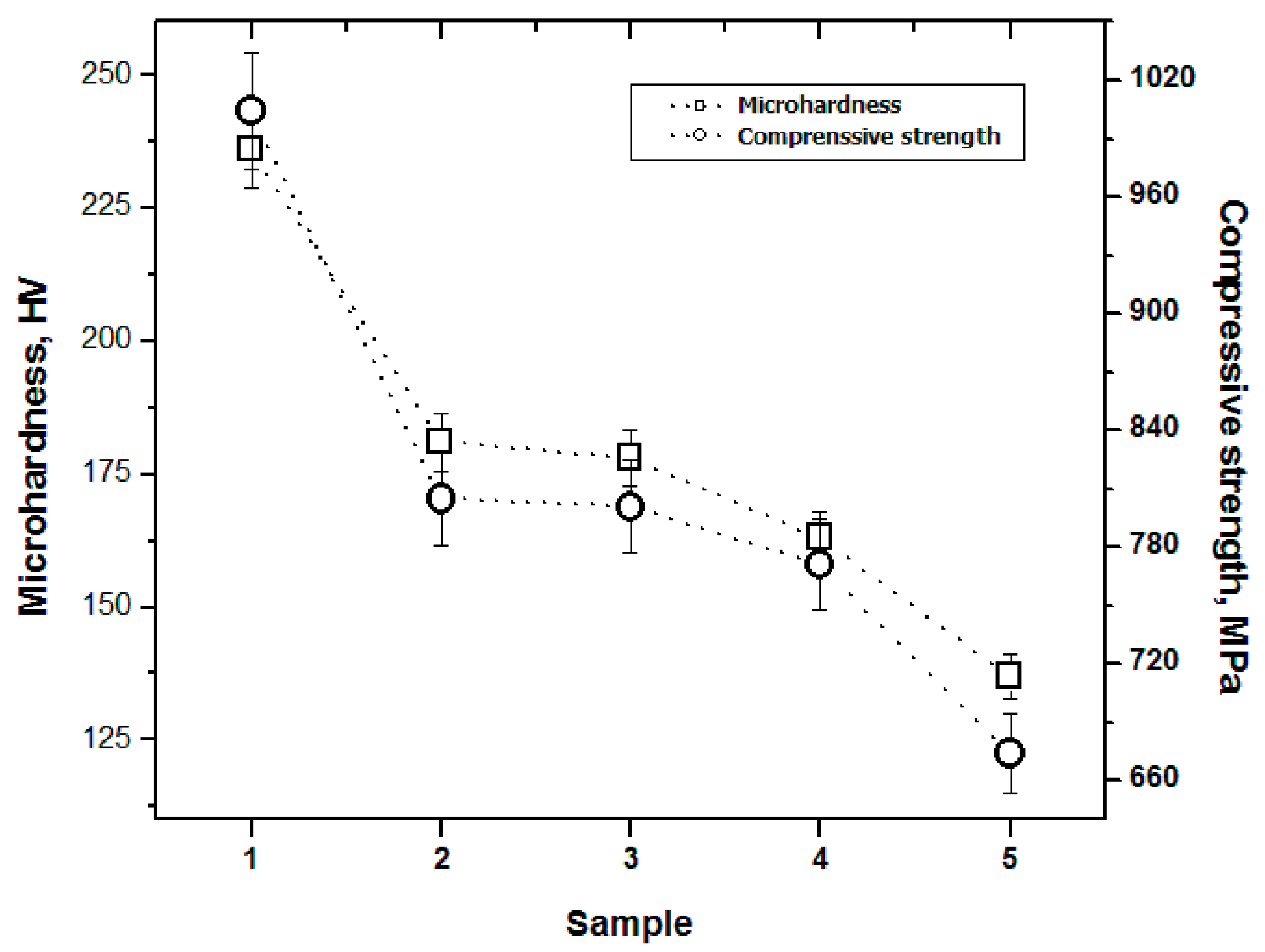

3.7.1. Microhardness

3.7.2. Compression Strength

4. Conclusions

- ○

- With increasing C, there is agglomeration of the metal particles, which causes the generation of large agglomerates and consequently abnormal grain growth during sintering.

- ○

- The structure consists of cubic phases centered on the body and faces for samples with 0 and 0.5% C, while for higher C contents the compact hexagonal structure appears due to the formation of carbides mainly of chromium (Cr7C3).

- ○

- The microstructure is characterized by the presence of grains with a similar size distribution that do not follow a specific pattern and are disordered due to the number of elements contained in the alloy. Also, increasing the amount of the dopant element causes cracking and pore formation.

- ○

- Elemental mapping indicated that the samples with sintered CrCuFeNiTiAl1CX alloys are formed by a multi-phase microstructure, as can be seen by the zones with different contrasts in the microstructure.

- ○

- The mechanical properties (microhardness and compressive strength) are negatively affected as the C content of the alloy increases.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| FCC | Face center cubic |

| BCC | Body center cubic |

| HCP | Hexagonal compact |

| EDS | Energy dispersive of X-ray spectroscopy |

| C | Carbon |

| μHV | Micro hardness Vickers |

| HEAs | High-entropy alloys |

References

- Zhang, Y.; Zuo, T.T.; Tang, Z.; Gao, M.C.; Dahmen, K.A.; Liaw, P.K.; Lu, Z.P. Microstructures and properties of high-entropy alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2014, 61, 1–93. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Liaw, P.K.; Zhang, Y. Recent Progress with BCC-Structured High-Entropy Alloys. Metals 2022, 12, 501. [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.-W.; Chen, S.K.; Lin, S.-J.; Gan, J.-Y.; Chin, T.-S.; Shun, T.-T.; Tsau, C.-H.; Chang, S.-Y. Nanostructured High-Entropy Alloys with Multiple Principal Elements: Novel Alloy Design Concepts and Outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2004, 6, 299–303. [CrossRef]

- H. H. Mao, H.L. Chen, Q. Chen, TCHEA1: A thermodynamic database not limited for “high entropy” alloys. J. Phase Equilibria Diffus. 2017, 38, 353–368.

- Otto, F.; Yang, Y.; Bei, H.; George, E. Relative effects of enthalpy and entropy on the phase stability of equiatomic high-entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 2628–2638. [CrossRef]

- Poletti, M.; Battezzati, L. Electronic and thermodynamic criteria for the occurrence of high entropy alloys in metallic systems. Acta Mater. 2014, 75, 297–306. [CrossRef]

- Cantor, B. Multicomponent high-entropy Cantor alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 120. [CrossRef]

- Mukarram, M.; Mujahid, M.; Yaqoob, K. Design and development of CoCrFeNiTa eutectic high entropy alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 10, 1243–1249. [CrossRef]

- Mukarram, M.; Mujahid, M.; Yaqoob, K. Design and development of CoCrFeNiTa eutectic high entropy alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 10, 1243–1249. [CrossRef]

- M. Manzonia, U. Glatzelb, New multiphase compositionally complex alloys driven by the high entropy alloy approach. Mater. Charact. 2019, 147, 512–532.

- MacDonald, B.E.; Fu, Z.; Zheng, B.; Chen, W.; Lin, Y.; Chen, F.; Zhang, L.; Ivanisenko, J.; Zhou, Y.; Hahn, H.; et al. Recent Progress in High Entropy Alloy Research. JOM 2017, 69, 2024–2031. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, H.; Wang, W.Y.; Kou, H.; Wang, J. Thermal–Mechanical Processing and Strengthen in AlxCoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloys. Front. Mater. 2021, 7. [CrossRef]

- R. Sriharitha, B. S. Murty, R. S. Kottada, Phase formation in mechanically alloyed AlxCoCrCuFeNi (x=0.45, 1, 2.5, 5 mol) high entropy alloys. Intermetallics, 2013, 32, 119–126.

- Ruiz-Jasso, G.E.; la Torre, S.D.-D.; Escalona-González, R.; Méndez-García, J.C.; Robles, J.A.C.; Refugio-García, E.; Rangel, E.R. Synthesis of CuCrFeNiTiAlx high entropy alloys by means of mechanical alloying and spark plasma sintering. Can. Met. Q. 2021, 60, 66–74. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.-H.; Yeh, J.-W. High-Entropy Alloys: A Critical Review. Mater. Res. Let. 2014, 2, 107–123. [CrossRef]

- Miracle, D.B.; Senkov, O.N. A critical review of high entropy alloys and related concepts. Acta Mater. 2017, 122, 448–511. [CrossRef]

- Zang, C.; Rivera-Díaz-Del-Castillo, P.E.J. High entropy alloy strengthening modelling. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 30, 063001. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Wang, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhao, X.; Feng, G. Digitalization and third-party logistics performance: Exploring the roles of customer collaboration and government. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 2023, 53, 467–488. https://doi org.dlsu.idm.oclc.org:9443/10.1108/IJPDLM-12-2021-0532.

- Wei, C.-B.; Du, X.-H.; Lu, Y.-P.; Jiang, H.; Li, T.-J.; Wang, T.-M. Novel as-cast AlCrFe2Ni2Ti05 high-entropy alloy with excellent mechanical properties. Int. J. Miner. Met. Mater. 2020, 27, 1312–1317. [CrossRef]

- Cantor, B.; Chang, I.T.H.; Knight, P.; Vincent, A.J.B. Microstructural development in equiatomic multicomponent alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 375–377, 213–218. [CrossRef]

- Gromov, V.E.; Rubannikova, Y.A.; Konovalov, S.V.; Osintsev, K.A.; Vorob’ev, S.V. Generation of increased mechanical properties of Cantor high entropy alloy. Izv. Ferr. Met. 2021, 64, 599-605. [CrossRef]

- ASTM E384–16; Standard Test Method for Microindentation Hardness of Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- The Chemistry of Carbon, Available online: https://chemed.chem.purdue.edu/genchem/topicreview/bp/ch10/carbon.php (accessed 8 March, 2025).

| Multicomponentsystem | Process | Reference |

| CuCrFeNiTiAlx | Mechanical alloying | [14] |

| CrCuFeNiTiAl1Cx | Powder metallurgy | [17] |

| Al2CoCrFeNiSi | Laser cladding | [17] |

| Al2CoCrCuFeNi1.5Ti | Laser cladding | [17] |

| AlCoCrCuFeNi1 | Laser surface alloying | [17] |

| AlCoCrCuFe | Laser surface alloying | [17] |

| CuCoFeNiTix | Electric arc melting | [18] |

| AlCrFeNi2Ti0.5 | Electric arc melting | [19] |

| Fe20Cr20Mn20Ni20Co20 | Induction melting | [20] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).