2. Tomographic Representation of Common Quantum-Mechanical Wave Functions

In quantum mechanics and in classical mechanics developed during the last century, the basic notion of position and velocity (momentum) of systems like a sole particle was defined and extensively used; this notion is intuitively different for classical mechanics and for quantum mechanics, while the notion of time is common for both type of systems. The development of quantum mechanics during the last century provides the possibility to employ the basic notion of the particle state – the common idea of the probability distribution of a particle position and momentum. This idea looked very attractive, there were many attempts to find this probability, but there were difficulties like the Robertson–Schrödinger uncertainty relations of the position and momentum, which were considered as arguments to forbidden the possibility of such an idea.

We discuss some examples to realize this possibility and present a short review of probability distributions describing states of the particle moving in some potential wells. In the conventional formulation of quantum mechanics, the wave function satisfying the Schrödinger equation [

22,

23] and the density matrix introduced by Landau [

24] and von Neumann [

25]; Tombesi et al. showed that both the wave function and the density matrix can be invertible mapped [

26] onto conventional probability distributions (tomograms) describing the quantum states, density operators, and density matrices [

27]. The quasi-distributions, such as the Wigner function [

28] and the Husimi function [

29], are also used to determine quantum tomograms. The pure quantum spin-1/2 states can also be described by the probability distribution [

30]. The probability description of quantum states is useful for developing quantum technologies and quantum information processing.

The tomographic probability representation can be obtained from a standard wave function

as the following integral

where the variable

X is interpreted as a rotation and rescaling of the phase space variables

of a quantum system, i.e.,

, with

and

, where

are re-scaling and rotation factors respectively.

The tomographic distribution of a state is a normalized probability distribution, which provides information of a combination of the position and momentum variables. Additionally, the tomogram can be used to obtain or reconstruct any quantum system as, in general, the density matrix is represented by

Below, we use properties of this definition to study the tomographic representation of different standard quantum systems.

2.1. Free Motion

Now we discuss the probability representation of free motion of a particle with the wave function

, where its evolution is described by the Hamiltonian

; we assume the units with

and

. The wave function of the particle

satisfies the Schrödinger equation

where the time evolution of the wave function can be described by the Green function

, which is the matrix element of the evolution operator

; in the position representation, it reads [

31]

and one has

The initial value of the wave function can be taken as a normalized function satisfying the normalization condition

and since the evolution operator is a unitary one, the normalization equality is the same for any value of time

t. This means that the density operator

satisfies the normalization condition

; due to this, we can calculate the tomographic probability representation of the particle, in view of the following formula:

expressed in terms of the wave function as given by Eq. (

1). Taking into account equation (

7),

, and properties of the trace operator

, we arrive at the equality

which means that

where

and

are parameters determined by the Heisenberg operators

and

of the free particle motion

Thus, we obtain the equality for tomographic evolution; it is

allowing us to predict the tomographic probability distribution for any time

t, if we take the tomogram for the free particle

and replace the parameters

and

by

and

.

2.1.1. Free Evolution of a Wave Packet.

In this section, we obtain the tomographic representation of a wave packet freely evolving. As it is known, the unidimensional free particle has the following wave function

which can be used to define a normalizable wave packet of the form

with

and

is the initial envelopment of the wave packet. The tomographic representation of this wave packet can be obtained, using Eq. (

1) and the imaginary Gaussian integral [

32,

33]

Defining

and

, we arrive at the following general expression for the tomogram of any wave packet:

As an example, for a Gaussian wave packet with initial form

, one has the following

time-dependent wave function

which defines the following tomographic probability distribution:

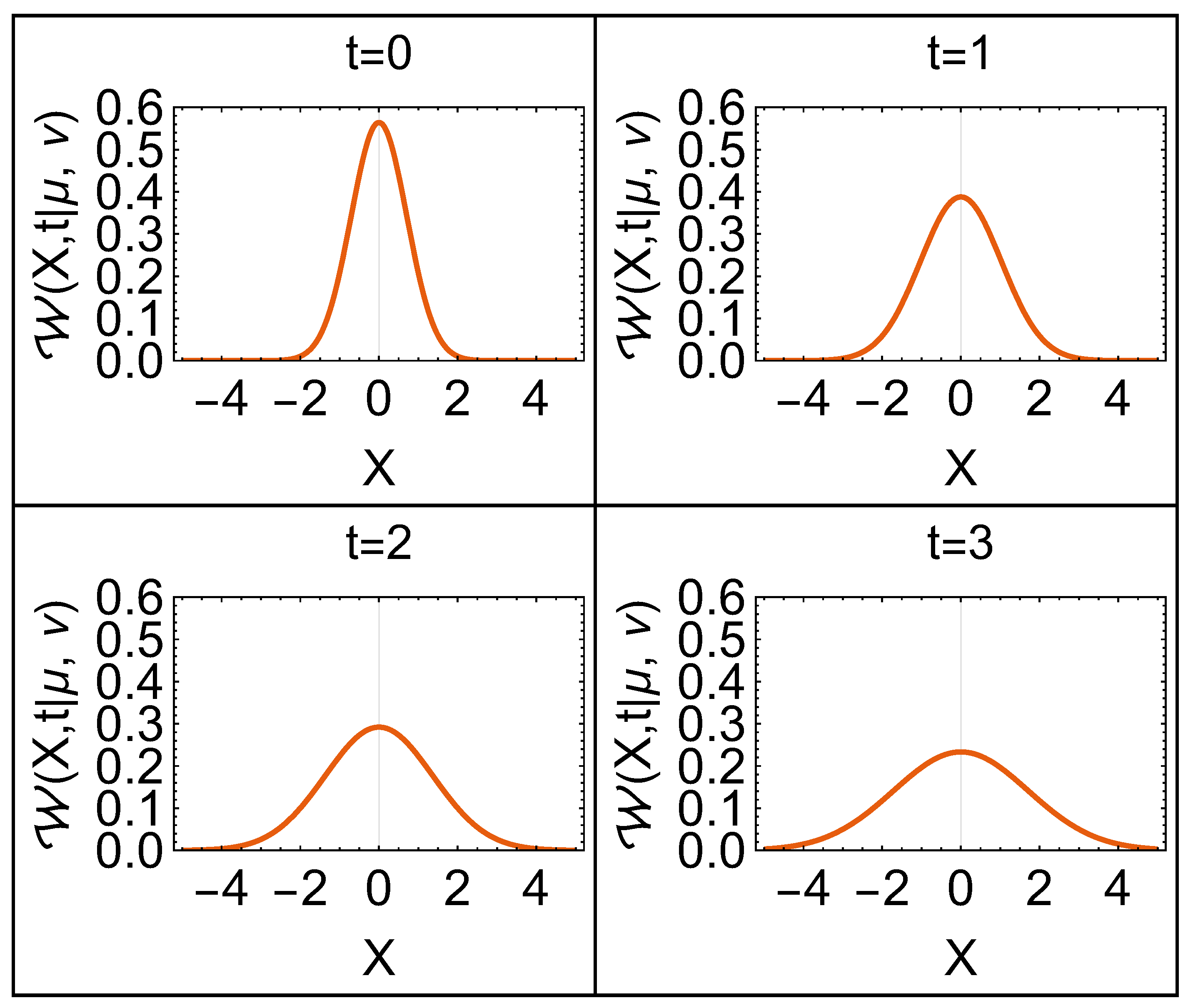

In

Figure 1, the evolution of a Gaussian wave packet at different times is shown. One can see the spreading of the packet along the space as time increases. One can notice that the time dependence of the variance

is quadratic, implying a linear standard deviation

for large

t. This is an interesting property, since it can help to evaluate time differences by measuring the standard deviations of the system at different times.

2.2. Finite Potential Well

Another example, where we can obtain the tomographic representation, is the finite potential well; it is a potential given by the function

with

being a positive constant. This problem allows one to obtain odd and even solutions given the symmetry of the potential well. The general solutions are usually obtained for three regions in the position space:

,

, and

; they read

For all the eigenfunctions, one has the relations

and

, while for odd (even) solutions, the parameters

(

). Additionally, the normalization constants

A,

, and

B are defined as

To obtain the tomographic representation of the wave functions, we separate the tomogram integral of Eq. (

1) in three regions:

,

, and

. For the odd wave functions, one obtains the following integrals:

and an analogous expression is found for the even states. The following integrals can be obtained for the regions outside of the barrier

while, inside the barrier, one has the following expressions for the even states:

and this integral for odd states, inside the barrier

Then, using Eqs. (

1), (

23), and (

24), one can plot the tomographic representation of the even and odd states of the finite potential well. In

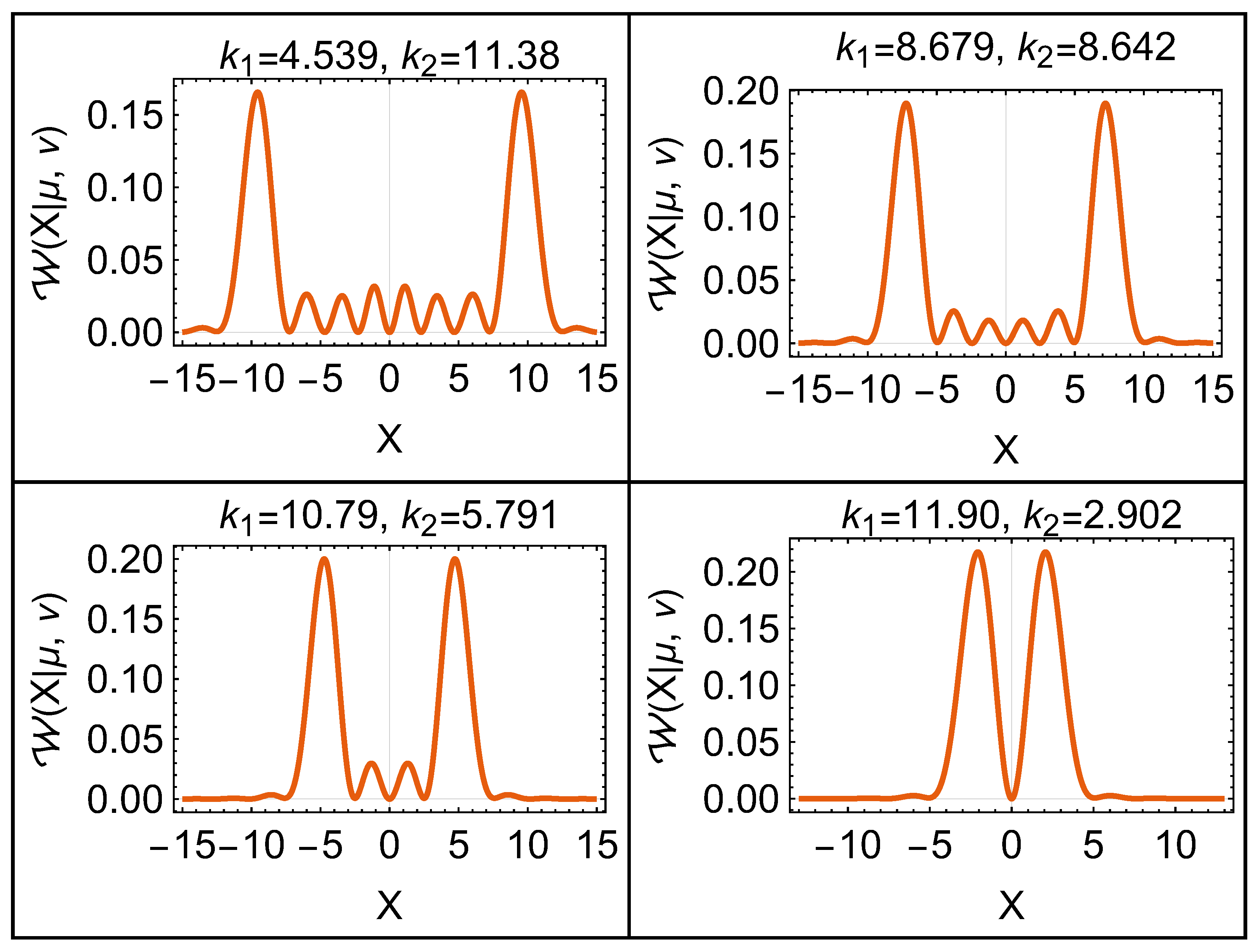

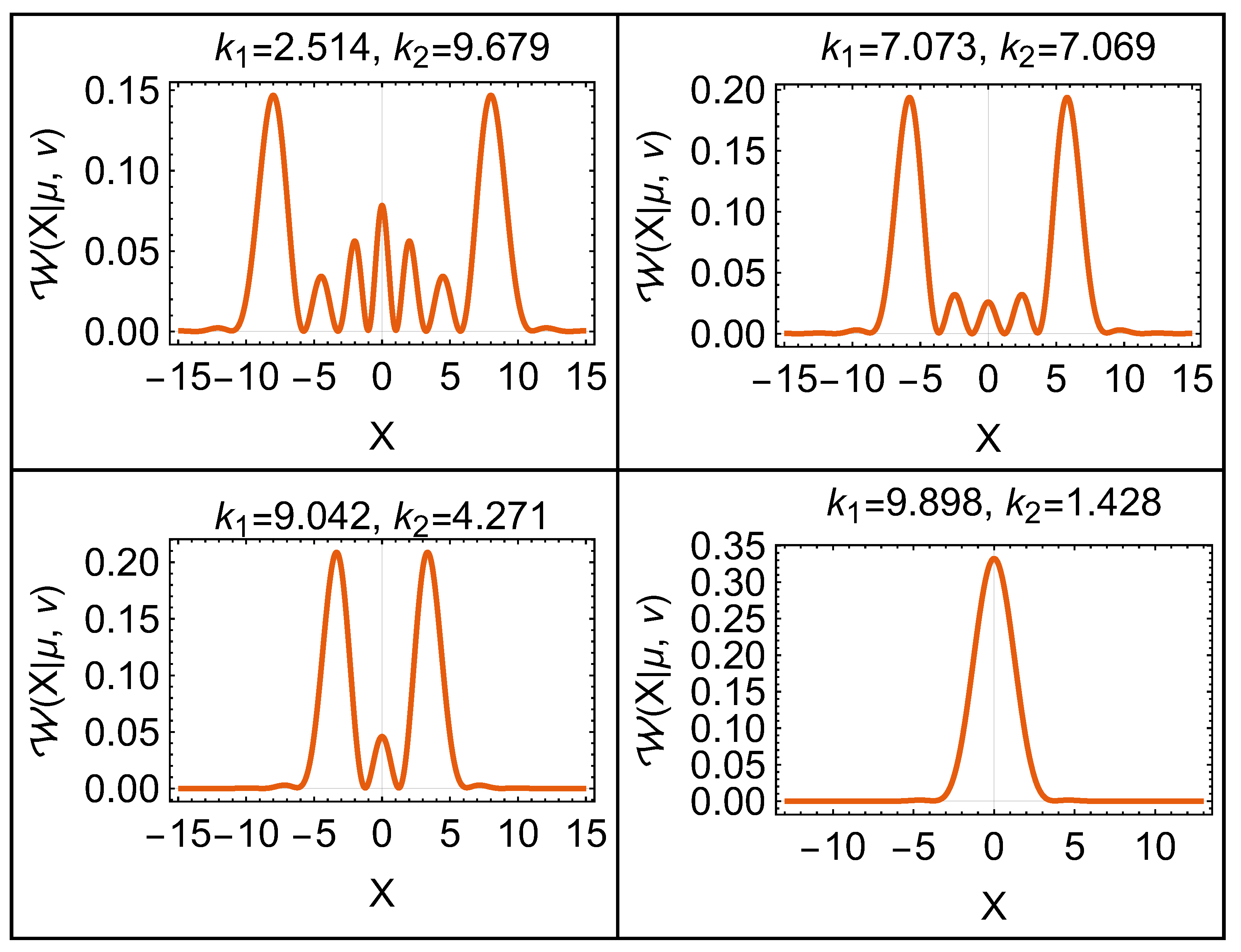

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, we show the behavior of tomograms for the even and odd solutions of the problem. In these figures, one can see the combination of the position and momentum probability distributions. These tomograms have maxima around the well borders as in the momentum probability distribution and local maxima at the origin and other localized points inside the well as in the position probability distribution.

2.3. Infinite Potential Well

Another interesting example is the non-symmetrical infinite potential well. In this case, the problem is defined by the potential

which defines the following asymmetrical eigenfunctions of the system:

In view of this expression, we obtain the tomographic representation which, in this case, can be determined using the following integral:

expressed in terms of the imaginary error function. Using Eqs. (

1), (

26), and (

27), the result is given by the following equation:

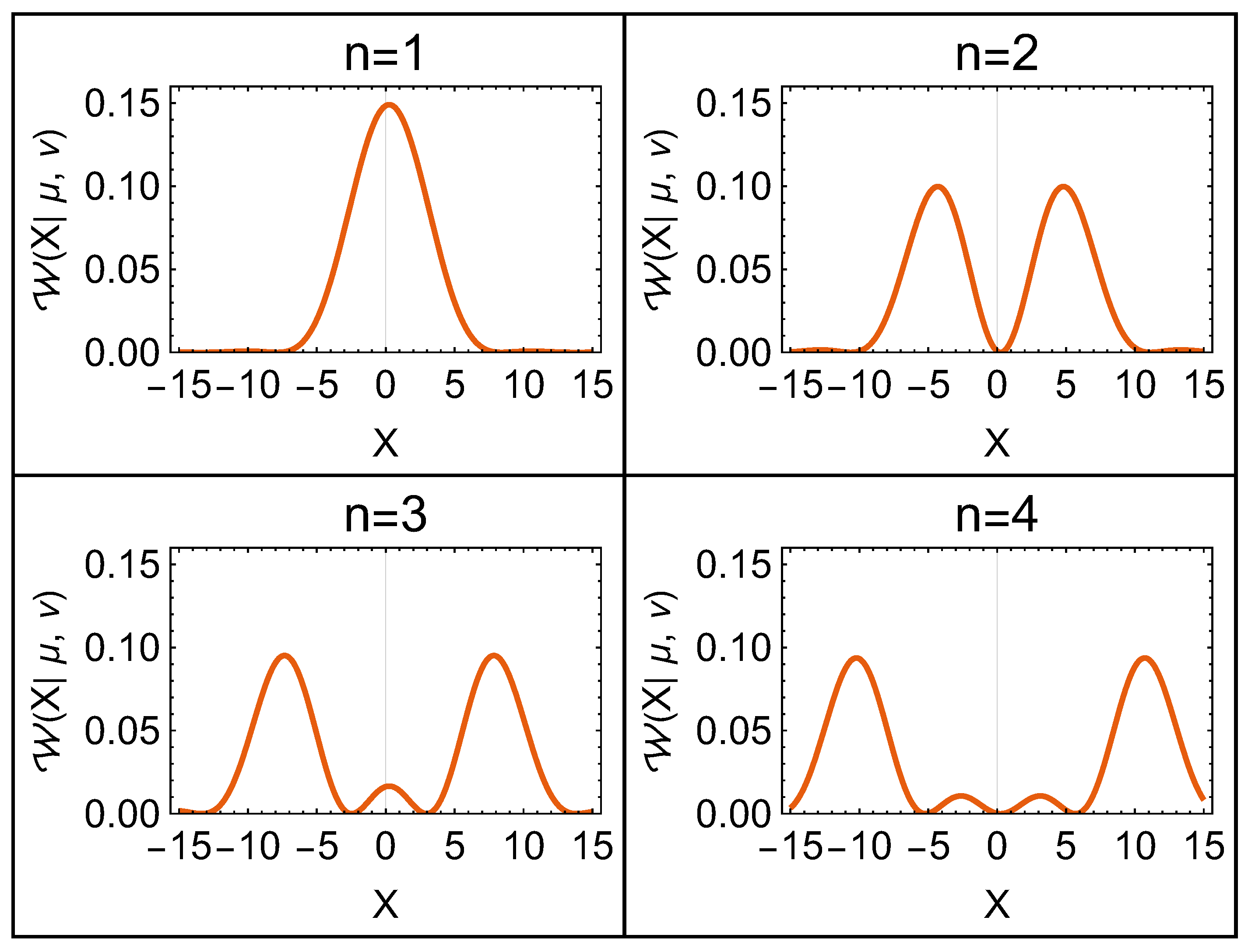

In

Figure 4, we show the tomographic representation of the first four wave functions for the infinite well. One can see that, in the finite potential well, a combination of the momentum and position probability distributions, where the momentum probability has maxima at the borders of the potential and the position probability has maxima at localized points related to the quantum number

n. In contrast with the solutions in the position representation which should be zero at

, the tomographic representation goes asymptotically to zero as the variable

X goes to plus or minus infinity. This behaviour is also due to the momentum contribution of the tomogram.

2.4. Morse Potential

Our last example is the phenomenological molecular potential given by the Morse potential. The Morse potential, which reads [

34,

35]

where

D is the depth of the potential, and

is associated to the range of the potential. The bound solutions of this potential are given by

where

is an nonnegative integer and

j is a positive real number; both numbers are related to the energy, depth, and range of the potential as follows:

with

m being the reduced mass of a molecule. The tomographic representation of the solutions of the Morse potential can be numerically found. As an example, we obtain the tomographic representation of the Morse potential solutions with

and

.

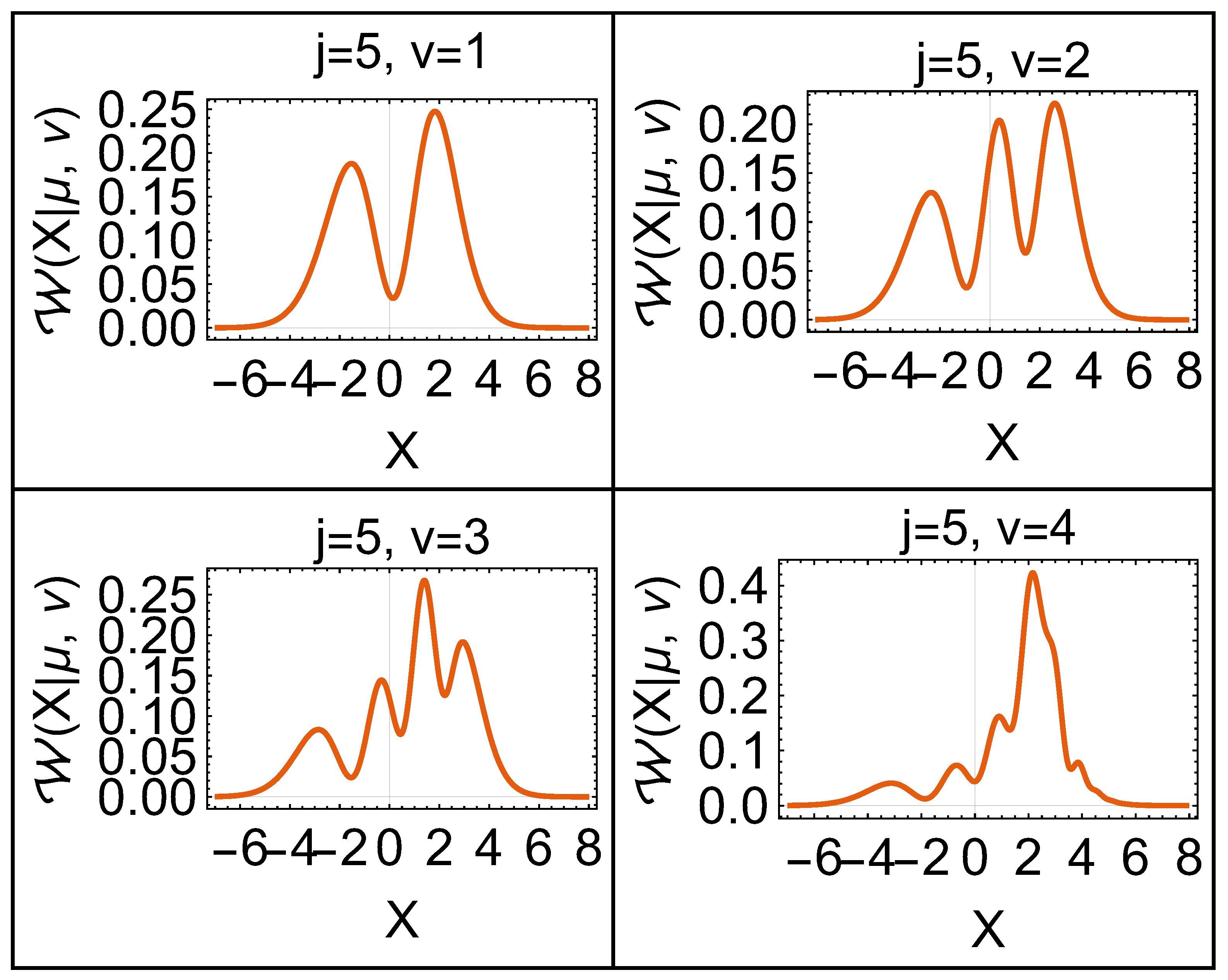

In

Figure 5, the numerical solutions for the tomographic representations of four eigenfunctions at

are shown. One can observe the complexity of the tomographic representation for the states. This complexity is bigger as the parameter

v increases. We point out that the maximum of the tomographic probability distribution is located around the potential minimum, which coincides with the position probability distribution.

3. Separability Criteria for Asymmetric Real States

The tomographic representation of quantum mechanics is useful to obtain information on the system, using probabilities. At the same time, other probability distributions for a quantum system give different information on its behavior. In this section, we study the momentum probability representation and its relation to the separability properties of specific bipartite systems.

Let us consider an arbitrary

n-partite wave function in the position representation

where the integers

;

characterize a particular state,

is a normalization constant, and the set of states

form an orthogonal basis of functions. It is known, that this state together with its conjugate must satisfy the probability conservation equation,

where we can express the gradient for a system of unidimensional particles as

. This probability conservation implies that, in the case of stationary states, the divergence of the probability current is equal to zero,

In particular, this stationary probability conservation equation can be satisfied for quantum systems, where the probability current is equal to zero,

For this type of systems, one can prove the following theorem for the total momentum probability distribution

and reduced momentum probability distributions

.

Theorem 1

For a stationary system, with and depicted by an asymmetric wave function , with momentum representation written as

in a momentum domain , the total momentum probability distribution and the reduced momentum probability distributions are even functions of the momentum variables. That is, and , .

Proof

To demonstrate the property for a unidimensional system, one first integrate Eq. (

35) in the position

x, that is,

where

j can be rewritten with the help of the Dirac notation, and the momentum operator properties

and

, namely,

which, along with the completeness condition

, allow us to write the integral of the probability current

since the mean value of the momentum operator can be written in integral form, using the momentum probability distribution

, as

where

p is an antisymmetric function; then,

must be a symmetric function. This shows the theorem for a unimodal and unidimensional system.

In the n-partite, multidimensional case, one can prove this theorem for each component of , which reduces to the unidimensional case □.

In particular, any asymmetric real wave function satisfies the previous theorem, and thereof this aspect can be written as the following corollary.

Corollary 1

Any asymmetric real wave function in the position domain has an even probability distribution in the momentum domain and even reduced momentum probability distributions.

This property can be extended for any real density matrix since, in general, any real

can be constructed by a convex sum of products of real wave functions as follows:

where

is a real function. Then, the density matrix of Eq. (

40) in the momentum representation reads

with every superposed momentum probability distribution

being even functions of the momentum, as given by theorem 1. Then the probability distribution

is a convex sum of even functions, which is also an even function. These arguments can be summarized in the following corollary.

Corollary 2

Any asymmetric (a state with at least one asymmetrical reduced probability distribution ) real density matrix: , has an even momentum probability distribution and even reduced momentum probability densities .

Stressing the importance of this corollary for our study, we give a more detailed proof in Appendix A.

Then, the theorem and corollaries above can be used to examine the entanglement of a bipartite system, which can be described by an asymmetric real density matrix. The idea behind this is to explore the symmetries in the momentum space of an asymmetric density matrix under the partial inversion of one of its momentum variables, either or . This property can be given as the following theorem.

Theorem 2

A necessary condition of separability for a bipartite asymmetric real density matrix is if the probability distribution of the system is symmetric under both partial momentum inversions and . In other words, .

Proof

Any real asymmetrical bipartite separable density matrix can be written as a convex sum

where

and

are real and define at least one asymmetrical reduced position probability distribution; thus, using the results of corollary 2, the reduced momentum probability distributions

and

are even functions. In other words, the transformations

map density matrices into density matrices.

On the other hand, to demonstrate that, if a real asymmetrical bipartite density matrix does not obey the Peres–Horodecki criterion [

36,

37,

38] for separability, then the bipartite momentum probability distribution

may not be symmetrical on at least one partial momentum inversion (either

or

), we can first take into account a general entangled state, using the harmonic oscillator basis

(without loss of generality),

This leads us to the following bipartite momentum probability distribution:

where the momentum eigenfunctions of the harmonic oscillator are

and they have the same symmetry properties as the position eigenfunctions:

. The Hermitian condition of Eq. (

45) implies

, and the normalization condition is represented by

. The nonseparability of the system can be summarized, using the Peres–Horodecki criteria: the partial transpose density matrices

and

may not represent a well-defined quantum system when the system is non-separable.

Given these properties, the symmetry under the partial inversions

and

of the bipartite momentum probability can be directly obtained from Eq. (

46) as follows:

which may be equal to the original probability distribution

, if both

this may be satisfied, if the pairs

and

are both even–even and/or odd–odd numbers always (the system has symmetrical position probability distributions) or when, for given the correspondence

, one has

which means that the partial transpose operations

and

are bona-fide density matrices and, thus, the system is separable (for more details; see Appendix B), contradicting our initial suppositions of asymmetry and non-separability. So we conclude that

is hold for a real density matrix, only when the system is separable or when it has a defined symmetry for both subsystems (

and

) □.

The necessary separability condition given in theorem 2 is also a sufficient criterion in the cases, where the Peres–Horodecki criterion is a sufficient condition for separability. These cases include both conditions – when the sums of the parameters have two contributions and have two or three elements.

This separability criterion may allow us to detect bipartite entanglement, directly using the momentum probability distribution of the system and, thus, may be more convenient when working with continuous variable systems. On the other hand, this criteria may have implications in the probabilistic representation given by the tomogram. As we have discussed, the tomogram contains information on both the position and momentum probability distributions.

3.1. Example

For a better understanding of our results, we present an specific example of our separability criteria. Let us suppose a two-mode harmonic oscillator state of the form

which is not a factorizable state but may be separable. One can obtain the reduced density matrices

these define a symmetric probability function for mode 1 and an asymmetrical probability function for mode 2, in the position representation. In other words, this density matrix is real and asymmetric as established by theorem 2.

The momentum probability distribution of the system is then given by the function

being a symmetric function of both

and

. From this result and theorem 2, one can conclude that the system is separable. This can be corroborated as the system can be expressed as the following convex sum of product states

with the states

. Similarly to this example, more complicated states can be taken into account and their separability information may be obtained by examining the symmetry of the momentum probability distribution.

Summary and Concluding Remarks

In the present study, we briefly reviewed our collaboration works between the Lebedev institute and the Mexican research group at UNAM. Different contributions related to the tomographic representation of quantum dynamics, dynamics of superposition of coherent states, and geometric representations of quantum systems were mentioned.

In this contribution, the construction of probability distributions describing quantum system states was considered. The states are formally described either by vectors or by density operators acting in a Hilbert space. It turned out that there exists an invertible map of the vectors and density operators onto probability representations which we used in our article for concrete systems using wave functions describing the state vectors. This idea can be used for any other quantum systems. In particular, we presented new results associated to the tomographic representation of wave functions for different potentials, such as the free particle, the finite and infinite potential wells, and the Morse potential. We discussed some of their properties and behaviour, since the tomographic representation has information on both position and momentum probability distributions. In most of the cases, we provided the explicit expressions for the tomogram of the system.

Finally, we presented the study for separability in a bipartite asymmetrical real system, which lead us to provide a new criterion, using the symmetry properties of the momentum probability distribution that may be used to distinguish separability in a continuous variable system. In particular, this new criterion tell us that a necessary condition for separability of a real, bipartite system is that the momentum probability distribution satisfy and can be applied in the cases where at least one of the reduced position probability distributions is not symmetrical ( or ). This criterion corresponds to the Peres–Horodecki criterion applied to the momentum probability distribution and it is a sufficient condition in different systems.

We plan to extend our analysis of the probability representation of quantum systems in the cases where the behaviour of wave functions is known. For example, since the quasiclassical approximation of wave functions is well developed, we hope to use the quasiclassical expressions for wave functions and obtain the relation of wave functions to tomograms and find the quasiclassical expression for symplectic tomogram in all known cases of quasiclassical solutions for quantum systems. It can provide a new approach for considering quasiclassical probability distributions known in the probability theory. Also, we will propose how to find corrections to the tomograms corresponding to approximated solutions to the Schrödinger equation connected with approximated solutions to the equations for quantum tomograms. We will present such results in the future publications.