1. Introduction

The most general formulation of quantum mechanics is given in terms of a density operator, a statistical mixture of state vectors. Furthermore, in an open or composite quantum system, the system of interest is described by the

reduced density operator which is obtained by tracing out the total density operator over the remaining degrees of freedom. Using the method of protective measurements, Anandan and Aharonov have proposed the observation of the density matrix of a

single system, thus presenting a new meaning of the density matrix in this context [

1]. In this regard, it has been shown that the density matrix can be consistently treated as a property of an individual system, not of an ensemble alone [

2]. In addition to the statistical (mixture) and reduced density matrices, the

conditional density matrix, conditional on the configuration of the environment, has been discussed [

3] and argued that the precise definition is possible only in Bohmian mechanics.

On the other hand, Bohmian mechanics [

4,

5,

6,

7] is clearly a complementary, alternative and new interpretive way of introducing quantum mechanics, providing a clear picture of quantum phenomena in terms of trajectories in configuration space. A gradual decoherence process could then be devised by using the so-called quantum-classical transition differential wave equation, originally proposed by Richardson et al. [

8] for conservative systems. Doing so, the corresponding dynamics are governed by a continuous parameter, the transition parameter, leading to a continuous description of any quantum phenomena in terms of trajectories, scaled trajectories [

9,

10]. In other words, one is thus able to describe any dynamical regime in-between the quantum and classical ones in a continuous way emphasizing how this decoherence process is established (a scaled Planck’s constant is defined in terms of the transition parameter covering the limit

). Scaled trajectories also display the well-known non-crossing property even in the classical regime. Chou applied this wave equation to analyze wave-packet interference [

11] and the dynamics of the harmonic and Morse oscillators with complex trajectories [

12]. Stochastic Bohmian and scaled trajectories have also been discussed in the literature for open quantum systems [

13]. Moreover, by assuming a time-dependent Gaussian ansatz for the probability density, Bohmian and scaled trajectories are expressed as a sum of a classical trajectory (a particle property) and a term containing the width of the corresponding wave packet (a wave property) within of what has been called the

dressing scheme [

7]. Analogously, this scheme is also observed in the context of nonlinear quantum mechanics [

14] where, for example, solitons also possess this wave-particle duality; their wave property appears in the form of a travelling solitary wave and their corpuscle feature is analogous to a classical particle.

The procedure of using a continuous parameter monitoring the different dynamical regimes in the theory reminds us to the well-known WKB approximation, widely used also for conservative systems. Several key differences are worth stressing here. First, the classical Hamilton-Jacobi equation for the classical action is obtained at zero order in this approximation whereas the so-called classical wave (nonlinear) equation [

15] is reached by construction. Second, the hierarchy of the differential equations for the action at different orders of the expansion in

ℏ is substituted by only a transition differential wave equation which can be solved in the linear and nonlinear domains. Third, the transition from quantum to classical trajectories is carried out in a continuous and gradual way, stressing the different dynamical regimes in-between the quantum and classical ones. And fourth, this continuous transition can also be seen as a gradual decoherence process (let us say, internal decoherence) due to the scaled Planck’s constant, allowing us to analyze what happens at intermediate regimes [

16]. However, decoherence effects have also been analyzed in interference phenomena using a class of quantum trajectories, based on the same grounds as Bohmian ones, associated with the system reduced density matrix [

17]. Such a study has been carried out for statistical mixtures and studied in the framework of Bohmian mechanics [

18], the minimal view i.e., without any reference to the quantum potential. Even more, by writing the density matrix in polar form, a Bohmian trajectory formulation for dissipative systems has been proposed where a

double quantum potential being a measure of the local curvature of the density amplitude is responsible for quantum effects [

19]. A different approach has been taken for the hydrodynamical formulation of mixed states [

20] where a local-in-space formulation has been adopted in the sense that a hierarchy of moments contains the non-local information associated with the off-diagonal elements of the density matrix.

In the present article, our purpose is to provide a clear formulation of pure and mixed ensembles in terms of the Bohmian mechanics by using the polar form of the density matrix within the von Neumann equation framework. In this way, the corresponding quantum potential is introduced, and a momentum vector field is defined for both forward and backward in time motions. Once this is carried out, within the quantum-classical transition equation framework, a scaled Schrödinger equation is easily derived leading to the so-called scaled von Neumann equation. Afterwards, Moyal’s procedure [

21] used to interpret quantum mechanics as a statistical theory is then applied to the scaled theory by considering a characteristic function which is a standard function in statistical mechanics [

22]. The expectation value of the so-called Heisenberg-Weyl operator [

23] is treated as the characteristic function. Then, the inverse Fourier transform of the characteristic function is considered as the probability distribution function and its time evolution was thus obtained. In this way, the classical Liouville equation is again derived within this scaled theory. The foundations of nonequilibrium statistical mechanics are based on the Liouville equation which is assocaited with a Hamiltonian dynamics (in general, in phase space). In other words, with this theoretical analysis, we have clearly shown that a scaled statistical mechanics is well established and ready to be applied. This new nonequilibrium statistical mechanics would be valid for any dynamical regime, going from the quantum to the classical ones. As a simple illustration of our new formulation, scattering of a statistical mixture of Gaussian wave packets from a hard wall is studied and compared to the corresponding superposed state. The application of the new scaled nonequilibrium statistical mechanics will be postponed for a future work.

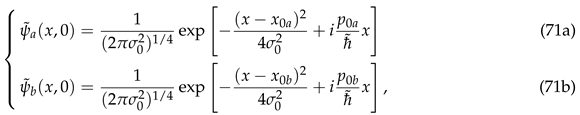

3. Results and Discussion

As a simple application of our theoretical formalism, let us consider scattering from a hard wall at the origin

and two scaled Gaussian wave packets

and

with the same width

but different centers

and

(initially localized in the left side of the wall) and kick momenta

and

i.e.,

and build the superposition state at any time as

and the corresponding mixture

where

is the step function and

the normalization constant. Note that the unitary evolution of the scaled wave functions under the corresponding von Neumann equation keeps purity of states which is quantified from

. By using now the propagator for the hard wall potential [

27]

one obtains that

where the sub-index “f" stands for “free" and the corresponding propagator is written as

Now, from Eq. (75), one reaches

where

being the complex width and the center of the freely propagating Gaussian wavepacket, respectively. The same holds for the

b component of the wave function replacing only

a by “

b".

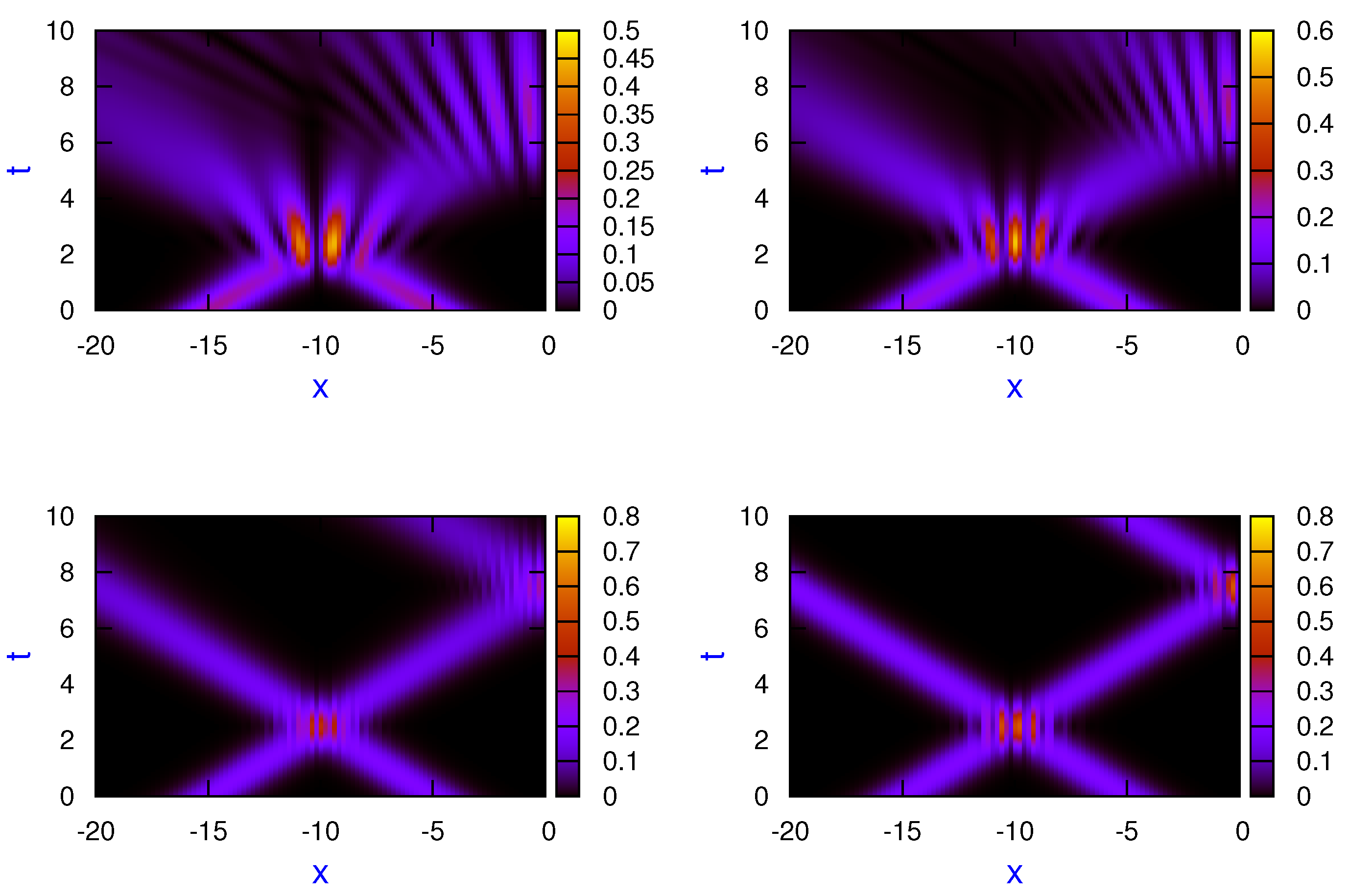

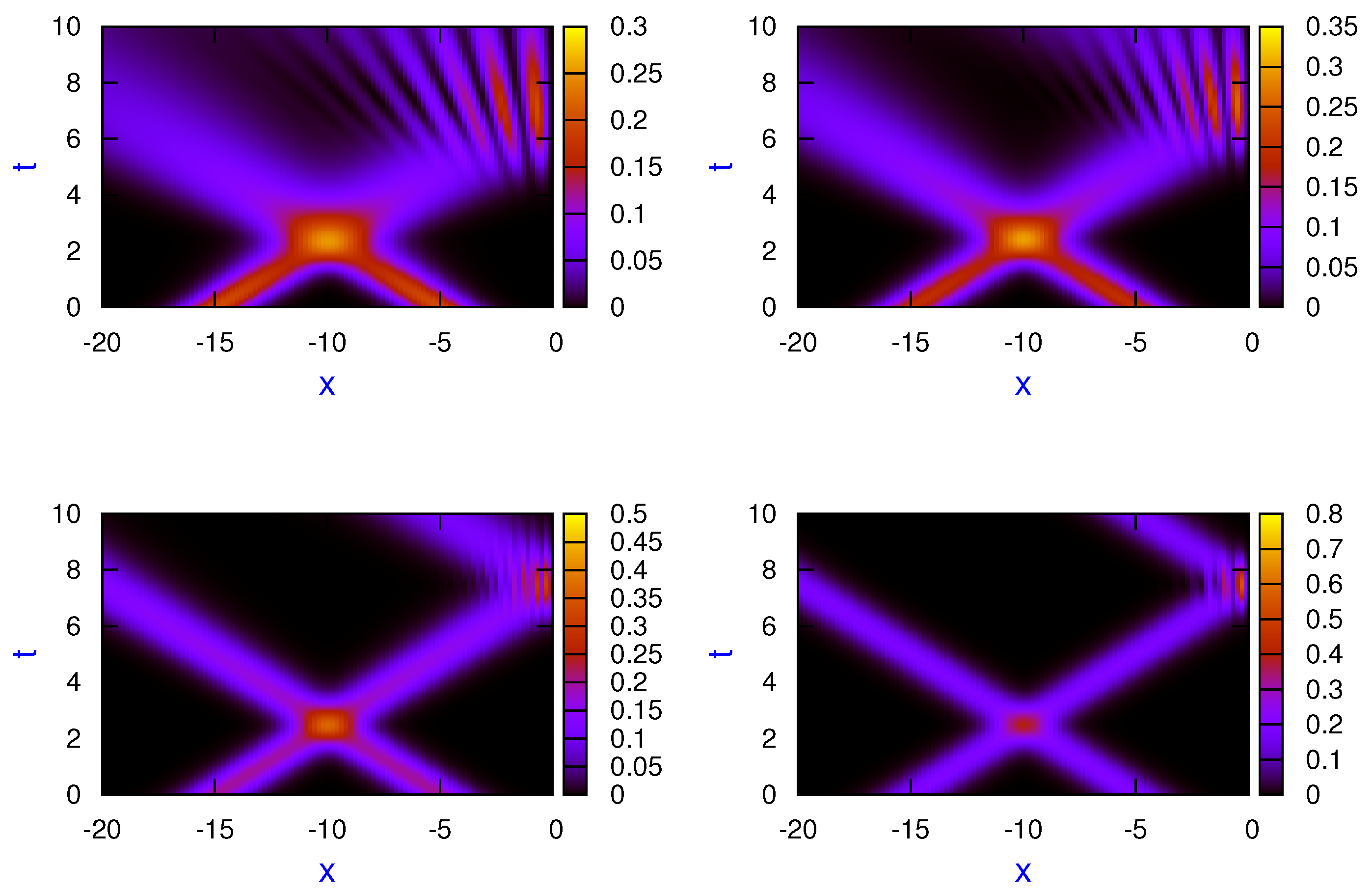

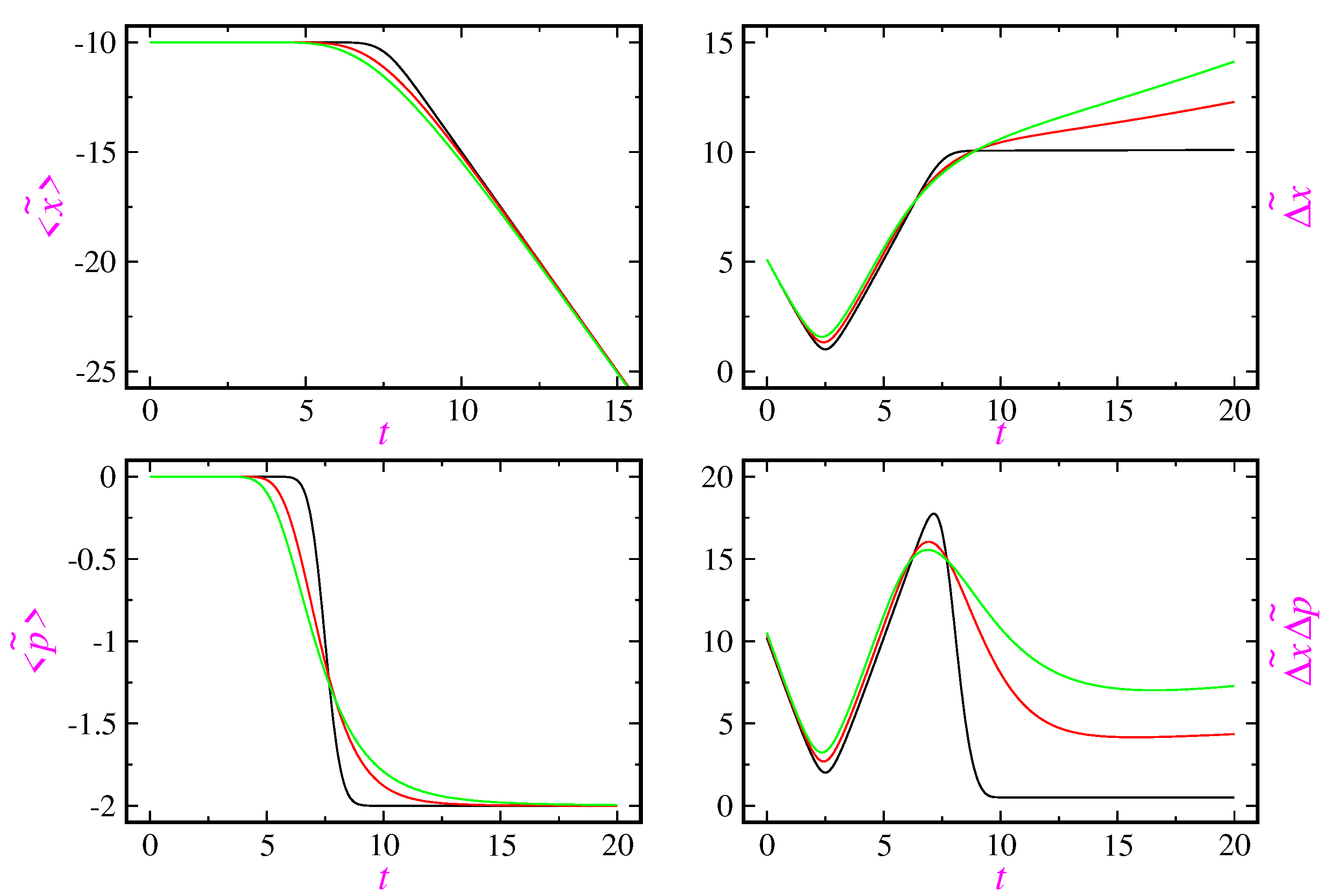

In

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 scaled probability density plots for the superposition of two Gaussian wave packets, Eq. (72), and for the mixed state, Eq. (73), for different dynamical regimes:

(left top panel),

(right top panel),

(left bottom panel) and

(right bottom panel). In both figures, the following initial parameters have been used for the calculations:

,

,

,

,

and

. As can clearly be seen in both cases, when the transition parameter is approaching zero (the classical dynamics regime), the interference pattern in collision between both states as well as in the scattering from the hard wall tends to be washed up in a continuous way. As one expects, when approaching the classical regime, results for the pure and the mixed states also become closer.

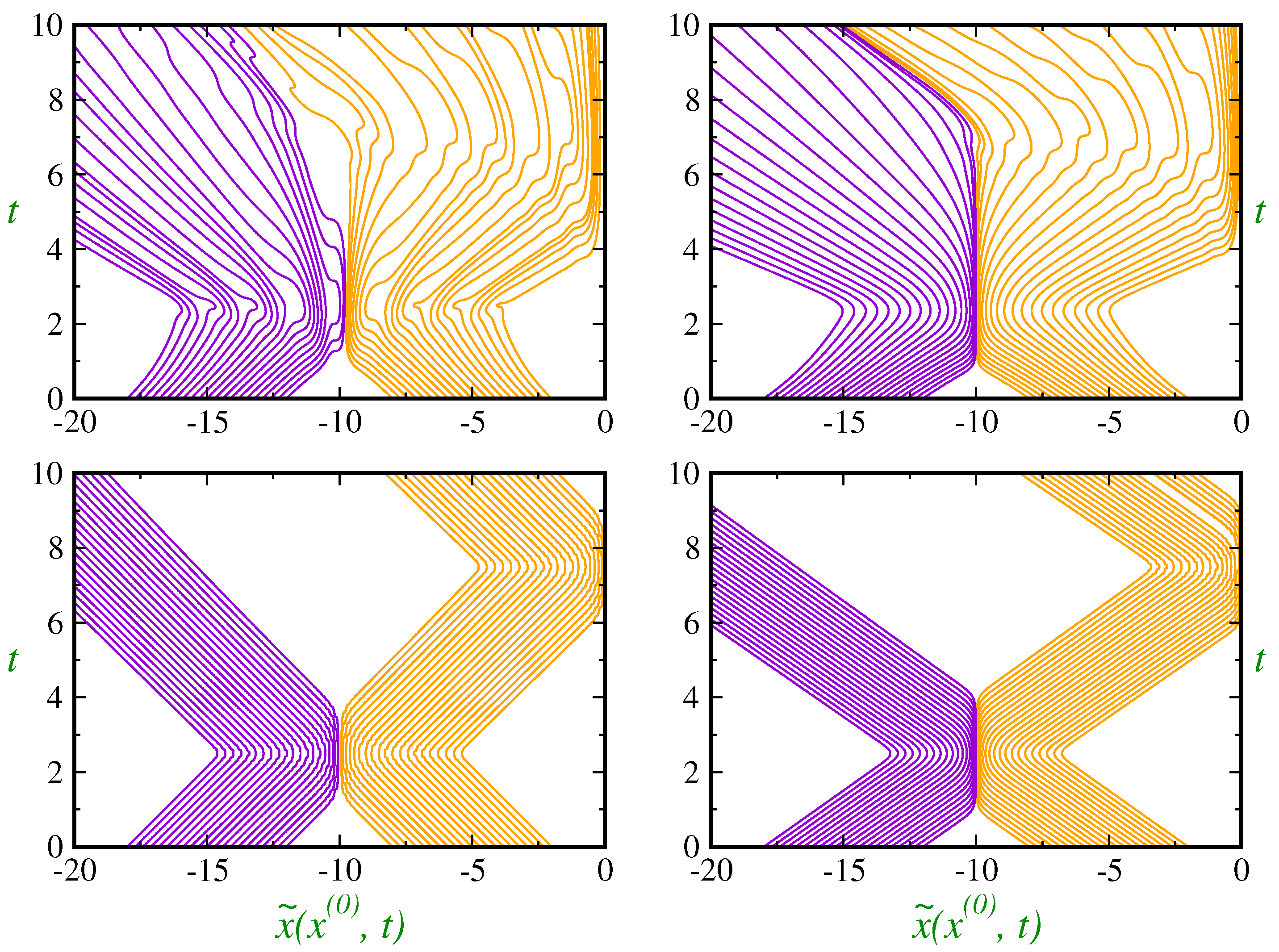

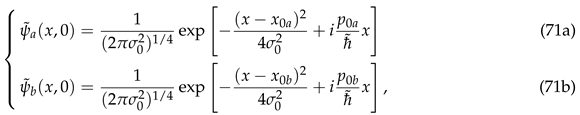

Let us discuss now how the

scaled trajectories behave in the different dynamical regimes, going from Bohmian trajectories (

) to pure classical ones (

). In

Figure 3, a selection of scaled trajectories is plotted for the scaled wave function

(left column) and the scaled density matrix

(right column) for the quantum regime (top panels) and the nearly classical dynamical regime

(bottom panels). The same units and initial parameters are used as previously. Comparison with the

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 reveals that trajectories follow the wave packets. In addition, although it is not apparent from our figure, but if one had selected the distribution of the initial positions according to the Born rule then he/she saw compact trajectories in regions with higher values of probability distribution. In other words, if trajectories obey the Born rule initially, they will do forever. The non-crossing rule of trajectories is still observed at nearly classical regime

and even in the classical regime which is a consequence of the

first order classical theory in contrast to the

true second order theory. As the classical regime is approaching, the corresponding trajectories become more localized simulating two classical collisions, the first one coming from the scattering between the two wave packets and the second from the wall. However, only the wave packet starting closer to the hard wall is reflected by the wall due to the second collision. As has also been discussed elsewhere [

28], wave packet interference can also be understood within the context of scattering off effective potential barriers. In classical mechanics, one can always substitute a particle-particle collision by that of an effective particle interacting with a potential. This fact is clearly observed in this context both for the superposition wave packet as well as for the density matrix.

From the non-crossing property of Bohmian trajectories, Leavens [

29] proved that the arrival time distribution is given by the modulus of the probability current density. Following the same procedure for the scaled trajectories, one has that the

scaled arrival time distribution at the detector place

X can be expressed as

Moreover, the mean arrival time at the detector location and the variance in the measurement of the arrival time which is also a measure of the width of the distribution are respectively given by

As a result of the previous analysis in terms of scaled trajectories, these quantities are easily calculated.

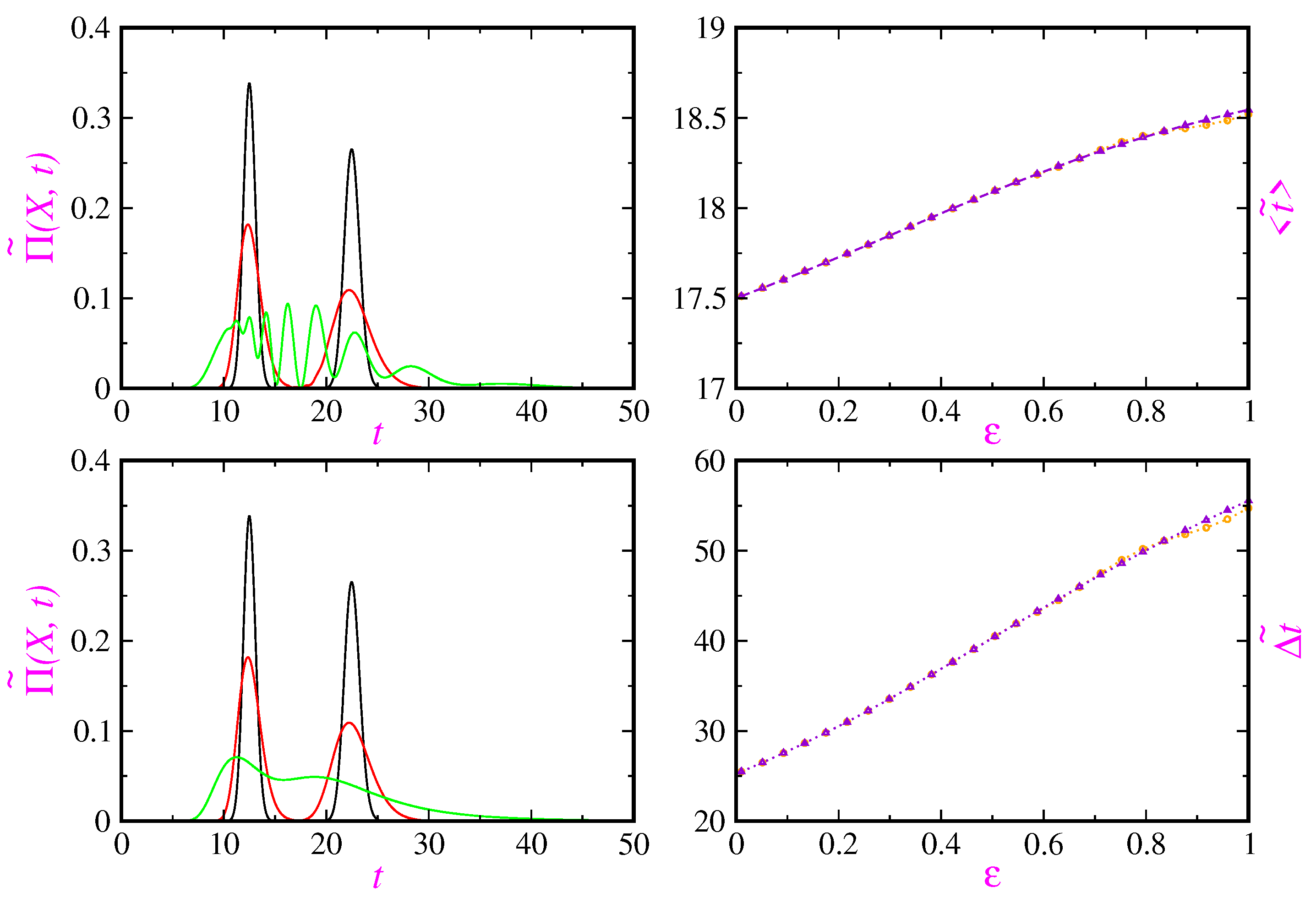

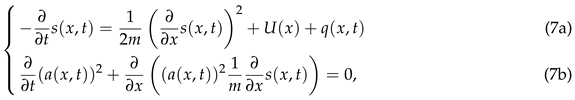

In

Figure 4, scaled arrival time distributions have been plotted at the detector location

for the pure state (

38) (left top panel) and the mixed state (

39) (left bottom panel) for three different dynamical regimes:

(green curve),

(red curve) and

(black curve). On the right top and bottom panels, the scaled mean arrival time and variance versus the transition parameter for the pure state (orange circled) and the mixed state (violet triangle up) have been also displayed. As clearly seen, the mean arrival time diminishes when going from the quantum to classical regime. This is related to the width of the probability distribution which is wider for the quantum regime than for the classical one. Furthermore, some differences between results coming from for the pure and mixed states seems to appear only around the quantum regime.

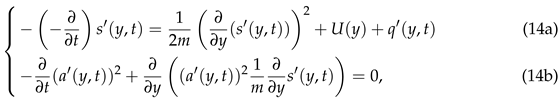

In

Figure 5 the expectation value of position operator (left top panel), uncertainty in position (right top panel), expectation value of momentum operator (left bottom panel) and the product of uncertainties for the scaled mixed state

for three different dynamical regimes:

(green curves),

(red curves) and

(black curves) are plotted. The same initial parameters are used as in previous figures. This figure shows that the continuous transition from the quantum to classical dynamical regime present several global and important features: (i) reflection from the wall is delayed on average; (ii) the average velocity in reflection decreases; (iii) the uncertainty in position which is also a measure of width of the state diminishes and (iv) the product of uncertainties also decreases at long times. Furthermore, the Heisenberg uncertainty relation

holds in any dynamical regime.

An interesting quantity is the

non-classical effective force defined via

From the mixture (73) one has that

where

is the expectation value of the momentum operator with respect to the component wavefunction

. From the scaled Schrödinger equation (42) and boundary conditions on the wavefunction and its space derivative one obtains

Finally, from Eqs. (83) and (84) one has that

Classically there is no force in the region

. In this regime, particles’ momentum reverses suddenly at the collision time with the hard wall, however this is not the non-classical case as the left-bottom panel of

Figure 5 shows. Only classical particles with initial positive momentum, (in our case, particles described by

) collide with the wall which, for our initial parameters, collision time is

.

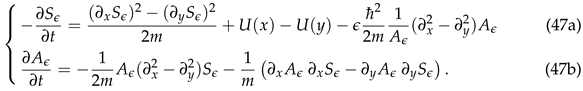

which are respectively the generalized Hamilton-Jacobi and the continuity equations where

which are respectively the generalized Hamilton-Jacobi and the continuity equations where

where

where

and, as one expects, .

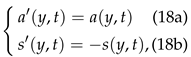

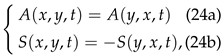

and, as one expects, . i.e., the amplitude (phase) of the density matrix is symmetric (antisymmetric) under the interchange. Now, by introducing Eq. (23) into the von Neumann equation (3) and splitting the resultant equation in real and imaginary parts, one again obtains the Hamilton-Jacobi equation for the phase

i.e., the amplitude (phase) of the density matrix is symmetric (antisymmetric) under the interchange. Now, by introducing Eq. (23) into the von Neumann equation (3) and splitting the resultant equation in real and imaginary parts, one again obtains the Hamilton-Jacobi equation for the phase

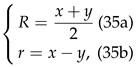

Eq. (29) is rewritten as

Eq. (29) is rewritten as

and build the superposition state at any time as

and build the superposition state at any time as

being the complex width and the center of the freely propagating Gaussian wavepacket, respectively. The same holds for the b component of the wave function replacing only a by “b".

being the complex width and the center of the freely propagating Gaussian wavepacket, respectively. The same holds for the b component of the wave function replacing only a by “b".