1. Introduction

Pandemics have had a strong influence on human history [

1]. The last pandemic, first in the 21st century, was COVID-19. It was due to SARS-CoV-2, a coronavirus which appeared in late 2019 possibly from a wild animal reservoir [

2] and that rapidly spread across the globe [

3]. This pandemic, which resulted in unparalleled tolls on health, economic and social life, reshaped public health strategies worldwide [

4]. It provided very strong arguments for the One Health concept, which stresses the importance of animals in the development of infectious threats to public health [

5]. Thus, although human-to-human transmission was the major driver of SARS-CoV-2 spread, the detection of infection in animals after the virus had spread through the human population [

6] raised strong concerns about the potential of non-monitored viral evolution in wild animal reservoirs [

7,

8].

Many domesticated animals (including cats, hamsters, ferrets, mink, raccoon dogs and rabbits) proved capable of SARS-CoV-2 infections, including in some cases viral transmission to other animals [

9]. Furthermore, wild animal species, whether living in captivity (largely great apes or zoo-held felines; [

10,

11] or in the wild (feral mink, otters, deer mice, woodrats, skunks, white-tailed deer)), also proved vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 infection [

7,

8,

9,

12]. Thus far thirty-six animal species from sixteen taxonomic groups have been reported across forty-four countries as susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 under field conditions [

5,

13].

Among animals, mustelids occupy a prominent position, given their susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection and ability to transmit the virus, to the point that [

14] suggested the possibility of panzootic spread of SARS-CoV-2 deriving from infected mustelids. After humans, this is the taxonomic group with the largest number of SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals declared (~16,000 reported in just eight countries; Fang et al., 2024), the majority of them (9,717 individuals) American mink (

Neovison vison) from fur farms, with eighty-four outbreaks reported across seven countries [

15]. In fur farms, mink COVID-19 infections initially derived from human caretakers, but then it spread by animal-to-animal transmission, in some cases with back infection to humans [

6,

9,

16]. Infected mink often exhibit clinical signs such as weight loss, respiratory tract manifestations and increased mortality [

17]. Adaptive viral evolution appears fast in infected mink [

9], and, in fact, the amino acid change mapping in the Receptor Binding Domain (RBD) of the S protein, S:Y453F, which increases the affinity for the ACE2 cellular receptor, emerged in a Danish mink farm, rapidly spreading through the human population [

18,

19].

Because of past escapes from farms, American mink has become an invasive self-sustained feral species in Spain [

16]. We [

7] pioneered detection of SARS-CoV-2 in feral mink by finding two infected animals in a pilot study among thirteen trapped invasive feral American mink living in the wild in the high courses of two rivers of the Valencian Community (East of Spain, Mediterranean coast,

Figure 1A). We now extend that study to sixty additional feral animals culled in the same river courses in three campaigns taking place from November 2020 till May 2022, finding four additional SARS-CoV-2 positive animals, three from the Palancia River (one per campaign) and one trapped early in the Mijares river. Our data on these seventy-three animals, although reassuring given the low prevalence of infection, allowed to make inferences from limited sequencing concerning viral evolution outside the eye of the health-monitoring system, highlighting the need for vigilance in these feral animals and the importance of the One Health approach.

In this article, we report the outcomes of this extended surveillance study, including prevalence data, virological characterization of positive cases, and ecological observations relevant to the zoonotic risk posed by feral mink.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area, and Procurement of the Samples

As described in our prior pilot study on thirteen feral mink [

7], the study area were the upper courses of the Mijares and Palancia rivers, two rivers of the Castellon province of the Valencian Community (East coast of Spain) (

Figure 1A) that have separate courses from origin to end, emptying in the Mediterranean at coastal points separated by about 30 km. Their upper courses are separated by mountain ranges with peaks reaching 1000 m of altitude. These rivers and tributary ravines sustain feral populations of American mink resulting from farm escapes and deliberate releases at the end of the 20th century. The sixty American mink (thirty-two males, twenty-eight females) studied here were culled by wildlife, as part of an invasive species management plan. The dates of the three culling campaigns (mid-November 2020, mid-March 2021 and early May 2022) and the location of the trapping sites (UTM coordinates and municipal districts hosting each given trapping site) are given in

Table 1.

The treatment of the animals, including humane sacrifice, conservation, examination, necropsy and collection of nasal and rectal swabs, of mediastinal lymph nodes and of lung tissue, were reported in our previous works [

7,

8]. Among the sixty animals reported in this paper, three pregnant females were identified at necropsy, and one fetus was collected at random from each pregnancy and placed in 1.5 ml of the guanidinium-based viral inactivating fluid used in smaller amounts (0.5 ml) for the swabs and tissue samples. The samples were then stored at −80 °C until processed for SARS-CoV-2 analyses.

2.2. Viral Detection and Molecular Analyses

Lymph node and lung tissue were homogenized as reported [

7,

8] and fetuses were processed in the same way. Total RNA was purified [

7] using the NZY Total RNA (NZYtech; Portugal) Isolation kit, following the protocol outlined by the manufacturer. For viral detection, we carried out a home-devised two-step RT-PCR procedure [

7] as modified in [

8]. Briefly, isolated RNA was firstly retrotranscribed to cDNA using the NZY First-Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (from NZYtech; Portugal) and then, detection was based on a separate 40-cycle qPCR amplification carried out as reported [

8] for the region of interest. Because of the large number of samples, detection was based on amplification of a single highly conserved region of the nucleocapsid (N) gene of the virus [

20]. Primers 5′GCAGTCAAGCCTCTTCTCGT3′ and 5’TTGCTCTCAAGCTGGTTCAA3' were used for qPCR amplification of nucleotides 28,701-28,951 of the viral genome (from here on, numbering corresponds to the Wuhan-1 viral genome sequence, GenBank NC_045512.2). Positivity was confirmed by separate qPCR amplifications of a region of the gene for the surface glycoprotein, S (bases 22,113-22,231; forward primer, 5′GGACCTTGAAGGAAAACAGG3′; reverse one 5’TGGCAAATCTACCAATGGTTC3’) or of the ORF10 gene and flanking regions (bases 29,511-29,698; forward primer, 5′ATTGCAACAATCCATGAGCA3′; reverse primer 5’GGCTCTTTCAAGTCCTCCCTA3’). qPCR procedures were performed exactly as in [

8]. The correctness of these amplifications was supported by electrophoretic sizing of the qPCR product (illustrated in

Figure 2) and by identification (Sanger sequencing) of the fragment produced in the amplification.

2.3. Sanger Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analyses

Following RT-PCR amplifications, the amplified DNA fragments were Sanger sequenced by a core sequencing service (Genomic Department, Centro de Investigación Príncipe Felipe, Valencia, Spain) using an automated ABI Prism 3730 instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States) and with the forward amplification primer serving as the sequencing primer. To find related SARS-CoV-2 sequences stored in the GenBank database, all sequences were run with BLASTN. The nucleotide and encoded amino acid sequences were aligned with the consensus SARS-CoV-2 sequence (GenBank NC_045512.2) using BioEdit ver. 7.2.5 software, which was also utilized for analysis and for determining the degree of identity of the recovered sequences [

8]. For phylogenetic analyses, distance matrices were calculated, and tree topology was inferred by the maximum likelihood method based on p-distances (bootstrap on 2,000 replicates, generated with a random seed) using the MEGA11 software [

21].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Animals Trapped

Sixty dark brown American mink were caught in three culling campaigns for controlling the invasive feral population of these foreign mustelids, the first in mid-November 2020, the second in March 2021, and the third one in early May 2022. Eight animals were trapped in the Mijares river, of which four/one/three were trapped in the 1st/2nd/3rd campaigns, respectively (

Table 1). The other fifty-two animals were trapped in the Palancia river course, of which twenty-nine/fourteen/nine were trapped in the 1st/2nd/3rd campaigns, respectively (

Table 1). In our previous pilot study [

7] on thirteen animals from both rivers, five animals (three and two from the Mijares and Palancia rivers, respectively) had been trapped in the last two months of 2020, and eight animals (three and five from the Mijares and Palancia river, respectively) in January 2021, respectively. Therefore, adding together the pilot and present studies, seventy-three feral mink have been tested for SARS-CoV2 in these two rivers (

Figure 1), of which forty-six represented a relatively early period of the COVID-19 pandemic, encompassing the end of 2020 and the first month of 2021.

3.2. The Body Weights of the Animals Provide Insight into the Local Population of Feral Mink

Although the American mink represents an already long-lasting invasive endemism in the courses of the Mijares and Palancia rivers, to the best of our knowledge no detailed study about this localized feral population of American mink has been published. The body weights of the present 60 animals were recorded (

Table 1), providing some information on this population. As is characteristic for this species [

22], body weights were larger for males (n=32) than for females (n=28) (

Figure 3A; male median and mean weights ~350 g higher than for females). Top weights of males and females were <1500 g and <1200 g, respectively (

Figure 3A), typical for wild mink but much lower than those for presently farmed mink (see for example [

22]), as expected for a feral self-sustained community.

Interestingly, the mean weight of males (

Figure 3B) increased in each culling campaign relatively to the previous one. Although only three males were culled in the third campain, preventing statistical significance for weights in this campaign relative to the prior ones, the mean weight was the highest for all groups, with little dispersion (1359 ± 82 g). In contrast, the mean weight for females appeared not to increase in the three culling campaigns (

Figure 3B). To try to understand why, we analyzed the frequency distribution by weight of the animals (

Figure 3C–F). Females trapped in mid-November 2020 (16 individuals) showed a trimodal pattern of frequency distribution on the basis of weight (

Figure 3C). The three Gaussian bells, from lower to higher weights (respective means±SD, 616±53 g, 780±31 g and 1150±21 g), comprised 61%, 27% and 12 % of the trapped females. The component of lowest weight and major abundance in terms of number of animals of this trimodal profile most likely represents inmature juveniles that were born on the same year, being culled at an age at which young minks set out to find their own territories

https://www.havahart.com/minks-facts). This explanation is supported by the shift of this first component towards higher body weights in the 9 females trapped in May 2022 (3rd campaign,

Figure 3D), a month in which essentially all the surviving newborns from the previous year must have reached maturity. Actually, if the three pregnant females trapped in May are removed (since pregnancy should cause a transient increase in weight in part due to the multiple gestation sacs with fetuses, see

Figure 3G), the frequency distribution fits a broad Gaussian bell (instead of the bimodal distribution shown) with a mean value of 790±110 g (curve not shown), a mean value that is very similar to the mean weight of the second Gaussian bell for the animals trapped in mid-November of 2020. This shift towards higher weights is also observed in the male cohorts when examining their frequency distribution for weight in the first and second culling campaigns, with 65% of the animals weighting <1 kg in mid-November 2020, while in the March campaign only 18% of the trapped males were of <1 kg. All this suggests that the majority of animals in the population were born the same year, in line with the conclusion of a Danish study [

22] that established that population turnover for American mink living in the wild was very fast because of low long-term survival rates.

The main conclusion of these observations is that the feral population in this Eastern Spanish localization shares the same life cycle that has been studied in other locations in Europe or North-America [

22];

https://www.havahart.com/minks-facts), in which new kits are born in late spring or early summer, they search for their individual territory in the fall after they are born, and they become mature at ≥12 months. Further support for this conclusion stems from the fact that pregnant females (animals 49, 52 and 54,

Table 1) were only found in the May culling, in line with the stablished time of delivery for this species in late spring or early summer. Pregnant females (

Figure 3A; dots marked in blue) fall at the higher end of the female weight distribution, likely due, as already mentioned, to the gestational contents and to physiological effects of pregnancy.

3.3. Four SARS-CoV-2-Positive Animals Were Detected Among the Sixty Animals Trapped

In the studies shown here we first obtained total RNA from four samples (nasal and rectal swabs and lung and mediastinal lymph node tissues) from each animal, except in the case of the three pregnant females, in whom, in addition, one fetus was also processed per pregnancy. The RNA was immediately retrotranscribed to cDNA, storing it at -20ºC. Then, when all the cDNAs had been produced, we carried out parallel qPCR assays for the N gene in one type of sample at a time, utilizing for fluorescent detection SYBR green. Of the 243 samples submitted to N gene-focused qPCR, only 6 samples belonging to four animals (animals 16, 29, 40 and 56) yielded a positive result. The positivity was not based only on the fluorescent output in the qPCR assay, but also relied on the observation by agarose gel electrophoresis of a product of the expected size (illustrative example in

Figure 2, bottom left panel), and on subsequent Sanger sequencing confirmation of the correctness of the site that was amplified. This result was confirmed for the six positive samples by repeating the RNA extraction, retrotranscription and N-gene focused analysis of the newly prepared cDNA sample. Then, the cDNAs that were positive for the N-gene, in parallel with a random selection of a few N gene-negative samples, were subjected to another two qPCRs focused on the S and ORF10 viral genes. As expected for the presence of the entire viral genome in the N gene-positive samples, these same samples were those positive for the S and ORF10 genes, using the same criteria as for the N gene, consisting in a positive qPCR result, the observation of a product of appropriate electrophoretic size (

Figure 2) and a Sanger sequence of the product that confirmed the identity of the amplified region..

In summary (

Table 2), from the 60 animals tested, only the already mentioned four ones (animals16, 29, 40 and 56) were positive, two of them (animals16 and 40) exhibiting positivity in the nasal swab samples, and the other two (animals 29 and 56) in the rectal swab sample, with no animal yielding positivity in the samples from both swabs. Only for one animal with a positive rectal swab sample (animal 29) the lung and mediastinal lymph node were positive. No animal was positive only for these internal tissues. The pregnant females were SARS-CoV-2-negative, and the three fetuses tested (one per dam) were negative, too. The two animals (animals16 and 40) for which the nasal swab was positive exhibited low viral loads, with positivity by qPCR manifesting only after Ct 29 for all three genetic regions examined. The animal with highest viral load, judged from the somewhat decreased Ct values for positivity in the qPCR assays, was animal 29, the one in which lung and mediastinal lymph node were positive. Even in this case, the positivity was observed after Ct 20 of the qPCR, supporting that the viral load was not very high.

Overall, the results are indicative of low prevalence of the virus among these 60 feral animals, and low viral load in those animals that hosted the virus. This aligns with the results of our prior pilot study [

7]. The necropsies of the animals, which were agnostic concerning viral infection, did not record particular lesions in the animals proven later on to be infected, suggesting that the infections were subclinical. Furthermore, the body weight of the infected animals did not stand out as particularly low (

Figure 3) relative to the bulk of the animals of the same sex.

While the total number of males and females in the 60-animal cohort was similar (28/32 females/males), three of the four infected animals identified presently were females. After pooling the results of the present study with those of our prior pilot study (total n=73; 33 females and 40 males; from now on we will refer in this section to the 73 pooled pilot and present studies) the proportion of infected females remained higher than that of infected males (12.1% and 5.0%, respectively). This difference was not statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test), although it could be real if it reflects a higher exposition to contagion of the females than of males because of extra food-searching exploration needed to satisfy the nutritional demand of the immature kits.

The distribution of the positive animals in terms of time of culling closely parallels the total number of animals trapped, since in the period defined by the first two campaigns of the present study and of the pilot study (end of 2020 and beginning of 2021), 61 animals were trapped and 5 were found to be infected (8.2%), while in the third campaign, which took place in 2022, only 12 animals were trapped and 1 animal (8.3%) was found infected. In turn, the proportions of infected animals found in the Palancia and Mijares rivers was, respectively, 6.8% and 14.3% of the animals trapped in the corresponding river, an apparently substantial difference which, nevertheless, is not statistically significant by application of Fisher’s exact test. When focusing on the animals trapped in the Palancia river, 3 of the 4 infected animals found in that river were trapped in the last 10 km of its high course, in the counties of the municipalities of Segorbe and Soneja (

Figure 1). This concentration of positive animals grossly parallels the number of mink trapped in these sites, which accounted for 49% of all the trappings made in this river. The same can be said for the Mijares river, where the sites of trapping of the two positive animals were localized within 8 km of high course of the river, the same area that concentrated 64% of all the mink trapped in this river.

3.4. Partial Gene Sequencing Reveals Common Traits with the B.1.177 and Alpha Variants of SARS-CoV-2

Although we used short stretches of Sanger sequencing just for confirmation of the region that had been amplified with each primer pair (see Materials and Methods), thus using only unidirectional sequencing utilizing a single sequencing primer (the forward one of the amplification) per amplicon, the quality of the sequences for a large part of the three amplicons was high enough for identification of sequence variants. This was the case (

Figure 4) for nucleotides 22,150-22,252 of the S gene (encompassing from the last base of codon 196 to the last base of codon 223 of the S gene coding sequence); nucleotides 28,734-28,951 for the N gene (encompassing from the 2nd base of codon 154 to the last nucleotide of codon 226 of the N gene coding sequence); and nucleotides 29,572-29,698 in the ORF10 gene region (encompassing from the second base of codon 5 till the last codon of this gene coding sequence, plus 24 downstream flanking bases of non-coding sequence

Figure 4). Although these regions were quite short, they revealed some differential sequence traits of interest. The sequences were identical (summarized in

Table 2) for the three positive samples (rectal swab, lung tissue and a mediastinal lymph node) of animal 29, supporting viral variant homogeneity within the same animal, not favoring the possibility of prolonged infection with the opportunity for separate local evolution of the virus in different tissular foci.

The partial sequences of the S and ORF10 genes were identical in all four animals, while the N gene partial sequence differed in two animals (animals16 and 40) from that in the other two positive animals (animals 29 and 56) (

Table 2 and

Figure 4). The S partial sequence was the shortest among the three regions sequenced (just 82 nucleotides) but it included codon 222, a site of early variation in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, where the amino acid change (relative to the Wuhan-1 sequence) A222V emerged in Spain and spread through Europe in the summer of 2020 [

23]. Our four positive animals had identical partial S gene sequences, which were identical, too, to the Wuhan-1 sequence, and thus, they did not encode the A222V change in the S protein. This change appears to favor subtle changes in the dynamic behavior of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of homotrimeric S protein in the human receptor binding-competent "up" conformation [

24]. Phylogenetic evidence strongly suggests that this change has emerged independently in several occasions and in different genetic backgrounds throughout the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic [

24], suggesting that it may enhance infectivity in humans, facilitating its establishment. This might not be the case for mink, in view of the absence of this change in our four positive feral animals, and also since among approximately 700 SARS-CoV-2 sequences obtained in Denmark from farmed mink from June till November-December of 2020, this change was only found in one infected animal [

25].

Unlike the partial sequence of S gene, the partial sequences of ORF10 gene and the N gene presented in our four animals showed differences relative to the canonical Wuhan-1 sequence. The variation in the ORF10 gene, identical for our four animals, was the base change 29645G>T (coding sequence, ORF10:88 G>T), causative of the amino acid substitution ORF10:V30L. The isolates from animals 16 and 40 presented in the N gene partial sequence the non-synonymous substitution 28932C>T (coding sequence N:659C>T) causative of the amino acid substitution N:A220V, whereas the isolates replacement 28881-28883GGG>AAC (N coding sequence, N:608-610GGG>AAC), encoding the double amino acid substitution in adjacent residues of the N protein, R203K/G204R. All these changes have been reported previously in viral isolates from humans. The amino acid changes N:A220V and ORF10:V30L, present in the viruses from animals 16 and 40, are characteristic of the B.1.177 viral variant, which was of high incidence in Spain during the end of 2020 and the winter of 2021 [

23]. In agreement with this, phylogenetic analyses show (

Figure 5B and C) that our partial sequences for the N and ORF10 genes from the isolates of animals 16 and 40 cluster with the B.1.177 variant. However, these viral isolates lack the A222V substitution in the S protein that also characterizes the B.1.177 variant [

23], what is reflected in the close clustering of the partial S gene sequences of our animals with the S gene of the reference Wuhan-1 genome (

Figure 5A) rather than with the S gene sequences of B.1.177 or of other viral variants. These S sequences also clustered with those from farmed mink in the Netherlands (GenBank Accession Numbers OM758316.1), Denmark [19, 25], and Italy (MT919525.1; [

26]), what would be

Expected if the S:A222V replacement were not fit for SARS-CoV-2 infection in mink, possibly related to differences in the ACE2 receptors of mink and humans. Not surprisingly, animals 16 and 40 were trapped in geographically close places in the same river (Palancia), supporting that they were infected with the same viral variant, which may have persisted in these locations at the two times of capture (mid-November 2020 and mid-March 2021).

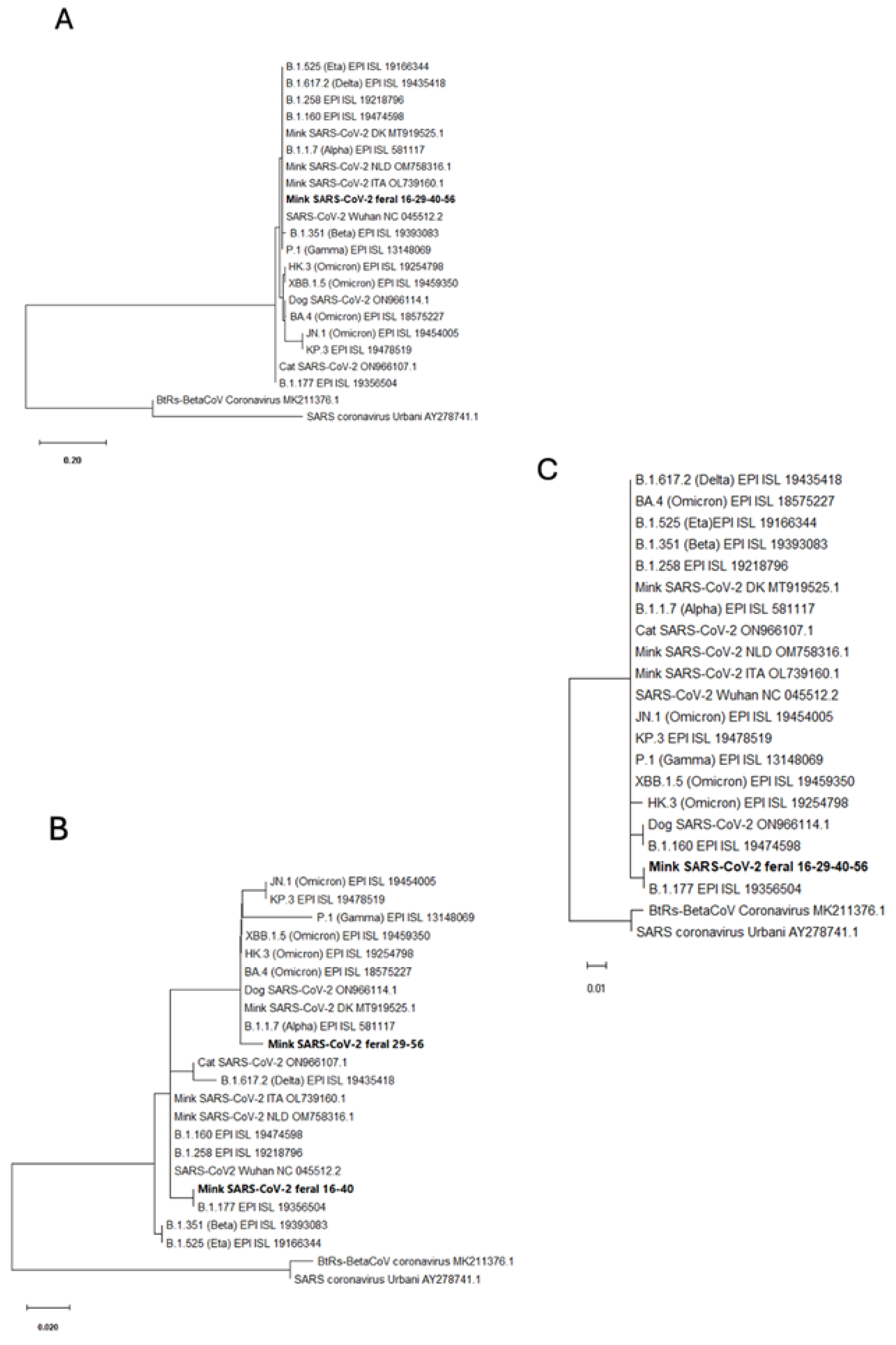

Figure 5. Molecular phylogenetic analyses based on partial gene sequences. These analyses used the regions defined by the consensus genome coordinates (GenBank accession number NC_045512.2) for nucleotides (A) 22,160-22,239 (corresponding to partial S gene sequence); (B) 28,871–28,964 (partial N gene sequence); and (C) 29,556–29,704 (partial ORF10 gene sequence). Our mink SARS-CoV-2 sequences are highlighted in bold type including at the end the appropriate GenBank Accession Numbers. Other sequences aligned have either Gisaid identifiers (EPI sequences) or GenBank identifiers (last group of characters in the row, when they have two initial capital letters followed by a six-digit number, in some cases followed by .1 or .2). DK, NLD and ITA correspond to Denmark, Netherlands and Italy. The trees are drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured according to the number of substitutions per site (see scale bars). The evolutionary history was inferred using the maximum likelihood method based on the Tamura–Nei model. In each case, the tree with the highest log likelihood is shown. Initial trees for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying the neighbor-join and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the maximum composite likelihood (MCL) approach and selecting the topology with superior log likelihood values.

The 3-nucleotide replacement 28881-28883GGG>AAC identified in the N gene of our positive animals 29 and 56, is typically associated with the Alpha (B.1.1.7) variant of SARS-CoV-2 [

27], as shown by the clustering with this variant of the isolates from these animals in the phylogenetic tree of the N gene partial sequence (

Figure 5-B). The Alpha variant surfaced in the UK in the late summer or early fall of 2020 [

28], some time earlier that animal 29 was trapped, whereas animal 56 was trapped in May 2022, two months later than the declaration by the World Health Organization that the Alpha variant was extinct among humans. Thus, the origin and persistence of this isolated sequence trait among those traits typical of the Alpha variant in this relatively remote population of feral mink deserves further study. This is supported, too, by the fact that animals 29 and 56 were trapped not only at dates separated in time by 18 months but also in independent river courses and in locations that are quite apart from those in which the viral isolates of the B.1.177 lineage were identified in the other two mink found positive in the present study.

3.5. Final Considerations

The present data revealing modest numbers of infected individuals in a relatively large cohort of animals culled in periods of high COVID-19 prevalence in the human population, are reassuring concerning the infectability in the wild of this highly susceptible species to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Such information is important, given the existing concerns about spread of the virus among animals and potential risks to wildlife [

29], particularly since infected mustelids have been pointed [

14] as having potential for panzootic spread of SARS-CoV-2. If this potential is real, our study makes difficult to attribute such potential to American mink living in the wild, possibly because of their living habits of low sociability and strict territoriality. Other traits of American mink such as their life cycle, seasonality of mating, age to maturity and high turnover in the wild also appear to be retained by the feral invasive animals living in our temperate Mediterranean area, judged from our observations of weights of the animals in this cohort.

In summary, the extensive (for a feral population) study carried out now supports the conclusion of our previous pilot study [

7] that feral mink living in the wild can become infected, but it strongly suggests limited infection rates in the wild. This is in stark contrast to the situation encountered in mink farms [

17], where mink-to-mink transmission is highly efficient, facilitated by the closeness to humans and by the physical proximity between animals that is typical in farm settings. Furthermore, it also differs from observations with more social animals living in the wild, such as white-tailed deer in North America. Feng et al., [

12] reported evidence suggesting enzootic transmission within the deer population, allowing the virus to persist over time, while such intraspecies transmission may be more limited in feral or wild mink, which are less likely to encounter other mink or humans than deer living near urban or suburban areas.

We previously hypothesized for mink and for wild otter that SARS-CoV-2 contaminated waters may be the original source of the virus in those animals that are infected. SARS-CoV-2 has been shown to persist in environmental matrices such as water, soil, and air, which can lead to animal infections [

15]. Viral RNA has also been detected in the stools of COVID-19 patients, suggesting the plausibility of fecal-oral transmission [

30]. Furthermore, the presence of the virus in wastewater has been widely documented in countries including the Netherlands, France, Spain, the USA, and Australia [

15,

31,

32]. Barberá-Riera et al.[

29] detected SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater in Castellón (the province in which our animals live) and recovered the genome sequence of the dominant viral variant at the time of their study, (B.1.177), whose sequence is similar to the one in some of our trapped feral mink. However, the low infection prevalence observed among the feral mink suggest that oral-fecal transmission via residual waters is not an efficient pathway for SARS-CoV-2 spread. These results align with broader observations that waterborne transmission, while plausible, may not sustain high transmission rates in wildlife due to factors such as low viral loads in the environment or limited exposure opportunities [

15,

31]. Phylogenetic analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 sequences obtained from feral mink confirmed alignment of partial sequences with well-documented variants found in humans including the B.1.177 and Alpha variants. Yet, the absence of the A222V variant in the S protein is hard to explain without having to resort to the hypothesis of viral adaptation to animal species in which this reemerging mutation is not favorable for viral infectivity.

The distribution of positive samples across different anatomical sites in our study raises important questions about the stage and nature of SARS-CoV-2 infections in feral mink. In individuals 16 and 40, the only positive sample was from the nasal swab, which may indicate early stages of infection. During this phase, viral loads tend to be concentrated in the upper respiratory tract, as the virus primarily targets cells in the nasopharynx or in the nasal mucosa [

33]. Nasal swabs have been demonstrated to reliably detect high viral loads during this initial phase, before the virus disseminates to other parts of the body [

12,

34,

35]. In contrast, individual 29 tested positive in the lung, mediastinal lymph node, and rectal swab, suggesting a more advanced stage of infection, potentially reflecting systemic viremia. The detection of the virus in multiple tissue sites implies viral spread beyond the initial entry point, possibly through the tracheobronchial tree or systemic circulation [

33,

36]. Finally, individual 56 tested positive only in the rectal swab, which may suggest a late infectious phase characterized by fecal shedding of viral RNA. This pattern aligns with observations that fecal shedding of SARS-CoV-2 RNA can persist for extended periods, often after respiratory swabs test negative [

30,

31].

While our phylogenetic analysis provides valuable insights, we cannot draw further conclusions about potential variants due to the limitations of our sequencing approach. Unfortunately, we were unable to perform next-generation sequencing (NGS) on our samples due to high cycle threshold (Ct) values, which were on average above 30. NGS typically requires a higher viral load for reliable sequencing, and the low viral load in our samples limited our ability to extract sufficient data for deeper genomic analysis. Despite these limitations, the combination of the observed mutations and low viral load supports our suggestion that the life cycle of SARS-CoV-2 transmission among feral mink is not of major concern at this time. Despite this conclusion, continuous monitoring and genetic sequencing are essential to assess potential wildlife adaptation of the virus, supporting the One Health approach to managing zoonotic risks across human, animal, and environmental health sectors.

4. Conclusions

This study expands our understanding of SARS-CoV-2 circulation in free-living feral American mink and demonstrates that, although infection is possible, its prevalence in the wild appears to be low. The detection of viral variants previously circulating in humans, along with the absence of clinical signs and the lack of evidence for vertical transmission, suggests that feral mink may not play a significant role in maintaining or spreading the virus under natural conditions.Nevertheless, the presence of viral RNA in individuals sampled across time and space highlights the potential for sporadic spillover or limited intraspecies transmission. These findings reinforce the need for continued wildlife surveillance and genetic monitoring to detect changes in virus behavior or adaptation in animal reservoirs. As part of a broader One Health strategy, such efforts are essential for early warning and risk assessment of emerging zoonotic threats at the human–animal–environment interface.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and development of this study and agree to be accountable for its content. Francesca Suita and Miguel Padilla-Blanco designed and conducted the experimental work, led the data analysis, and were primarily responsible for writing the manuscript. Jordi Aguiló-Gisbert, Teresa Lorenzo-Bermejo, Beatriz Ballester, Jesús Cardells, and Elisa Maiques provided critical revisions and contributed to the refinement of the manuscript. Víctor Lizana contributed to the development of maps and figures and participated in the manuscript revision. Vicente Rubio led the major rewriting process, contributed to figure design, formatting, and overall manuscript revision. Consuelo Rubio-Guerri contributed to writing, revision, and formatting of the manuscript. .

Funding

This research received external funding to VR, CRG, and EM from the Spanish Agencia Estatal de Investigación (Plan Estatal de I+D+i) (PID2020-120322RB-C21).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated and analyzed during this study have been deposited in GenBank. The accession numbers for the sequences are: S region: PQ461249 N gene region mutation C28932T: PQ461250 N gene region mutation GGG28881-28883AAC: PQ519871 ORF10 region: PQ461251 Additional data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

All the authors acknowledge and thank their respective Institutes and Universities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SARS-CoV-2 |

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

References

- Hempel S (2018) The atlas of disease: Mapping deadly epidemics and contagion from the plague to the zika virus. White Lion Publishing, London.

- Zhou P, Yang X, Wang X, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, Si H, Zhu Y, Li B, Huang C, et al. (2020) A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 579(7798):270–273. [CrossRef]

- González-Candelas F, Shaw MA, Phan T, Kulkarni-Kale U, Paraskevis D, Luciani F, Kimura H, Sironi M (2021) One year into the pandemic: Short-term evolution of SARS-CoV-2 and emergence of new lineages. Infect Genet Evol 92:104869.

- Bonotti M, Zech ST (2021) The Human, Economic, Social, and Political Costs of COVID-19. In: Bonotti M, Zech ST (eds) Recovering Civility during COVID-19. Springer, Singapore, pp 1–36.

- Nerpel A, Käsbohrer A, Walzer C, Desvars-Larrive A (2023) Data on SARS-CoV-2 events in animals: Mind the gap! One Health 17:100653.

- Jahid MJ, Bowman AS, Nolting JM (2024) SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks on mink farms-A review of current knowledge on virus infection, spread, spillover, and containment. Viruses 16(1):81.

- Aguiló-Gisbert J, Padilla-Blanco M, Lizana V, Maiques E, Muñoz-Baquero M, Chillida-Martínez E, Cardells J, Rubio-Guerri C (2021) First description of SARS-CoV-2 infection in two feral American mink (Neovison vison) caught in the wild. Animals 11(5):1422.

- Padilla-Blanco M, Aguiló-Gisbert J, Rubio V, Lizana V, Chillida-Martínez E, Cardells J, Maiques E, Rubio-Guerri C (2022) The finding of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in a wild Eurasian river otter (Lutra lutra) highlights the need for viral surveillance in wild mustelids. Front Vet Sci 9:826991.

- Meekins DA, Gaudreault NN, Richt JA (2021) Natural and experimental SARS-CoV-2 infection in domestic and wild animals. Viruses 13(10):1993.

- McAloose D, Laverack M, Wang L, Killian ML, Caserta LC, Yuan F, Mitchell PK, Queen K, Mauldin MR, Cronk BD et al. (2020) From people to Panthera: Natural SARS-CoV-2 infection in tigers and lions at the Bronx Zoo. mBio 11(5):e02220-20.

- Nagy A, Stará M, Vodička R, Černíková L, Jiřincová H, Křivda V, Sedlák K (2022) Reverse-zoonotic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 lineage alpha (B.1.1.7) to great apes and exotic felids in a zoo in the Czech Republic. Arch Virol 167(8):1681–1685.

- Feng A, Bevins S, Chandler J, DeLiberto TJ, Ghai R, Lantz K, Lenoch J, Retchless A, Shriner S, Tang CY, et al. (2023) Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in free-ranging white-tailed deer in the United States. Nat Commun 14(1):4078.

- Gómez JC, Cano-Terriza D, Segalés J, Vergara-Alert J, Zorrilla I, Del Rey T, Paniagua J, Gonzálvez M, Fernández-Bastit L, Nájera F, et al. (2024) Exposure to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in the endangered Iberian lynx (Lynx pardinus). Vet Microbiol 290:110001. [CrossRef]

- Manes C, Gollakner R, Capua I (2020) Could mustelids spur COVID-19 into a panzootic? Vet Ital 56(2):65–66.

- Fang R, Yang X, Guo Y, Peng B, Dong R, Li S, Xu S (2023) SARS-CoV-2 infection in animals: Patterns, transmission routes, and drivers. Eco Environ Health 3(1):45-54.

- Fenollar F, Mediannikov O, Maurin M, Devaux C, Colson P, Levasseur A, Fournier PE, Raoult D (2021) Mink, SARS-CoV-2, and the human-animal interface. Front Microbiol 12:663815.

- Boklund A, Hammer AS, Quaade ML, Rasmussen TB, Lohse L, Strandbygaard B, Jørgensen CS, Olesen AS, Hjerpe FB, Petersen HH, et al. (2021) SARS-CoV-2 in Danish mink farms: Course of the epidemic and a descriptive analysis of the outbreaks in 2020. Animals (Basel) 11(1):164.

- Bayarri-Olmos R, Rosbjerg A, Johnsen LB, Helgstrand C, Bak-Thomsen T, Garred P, Skjoedt MO (2021) The SARS-CoV-2 Y453F mink variant displays a pronounced increase in ACE-2 affinity but does not challenge antibody neutralization. J Biol Chem 296:100536.

- Hammer AS, Quaade ML, Rasmussen TB, Fonager J, Rasmussen M, Mundbjerg K, Lohse L, Strandbygaard B, Jørgensen CS, Alfaro-Núñez A et al. (2021) SARS-CoV-2 transmission between mink (Neovison vison) and humans, Denmark. Emerg Infect Dis 27(2):547-551.

- Dip SD, Sarkar SL, Setu MAA, Das PK, Pramanik MHA, Alam ASMRU, Al-Emran HM, Hossain MA, Jahid IK (2023) Evaluation of RT-PCR assays for detection of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. Sci Rep 13(1):2342.

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S (2021) MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol Biol Evol 38(7):3022-3027. [CrossRef]

- Pagh S, Pertoldi C, Petersen HH, Jensen TH, Hansen MS, Madsen S, Kraft DCE, Iversen N, Roslev P, Chriel M (2019) Methods for the identification of farm escapees in feral mink (Neovison vison) populations. PLoS One 14(11):e0224559.

- Hodcroft EB, Zuber M, Nadeau S, Vaughan TG, Crawford KHD, Althaus CL, Reichmuth ML, Bowen JE, Walls AC, Corti D et al. (2021) Spread of a SARS-CoV-2 variant through Europe in the summer of 2020. Nature. 595(7869):707-712.

- Ginex T, Marco-Marín C, Wieczór M, Mata CP, Krieger J, Ruiz-Rodriguez P, López-Redondo ML, Francés-Gómez C, Melero R, Sánchez-Sorzano CÓ et al. (2022) The structural role of SARS-CoV-2 genetic background in the emergence and success of spike mutations: The case of the spike A222V mutation. PLoS Pathog 18(7):e1010631.

- Rasmussen TB, Qvesel AG, Pedersen AG, Olesen AS, Fonager J, Rasmussen M, Sieber RN, Stegger M, Calvo-Artavia FF, Goedknegt MJF, et al. (2024) Emergence and spread of SARS-CoV-2 variants from farmed mink to humans and back during the epidemic in Denmark, June–November 2020. PLoS Pathog 20(7):e1012039.

- Moreno A, Lelli D, Trogu T, Lavazza A, Barbieri I, Boniotti M, Pezzoni G, Salogni C, Giovannini S, Alborali G, Bellini et al. (2022) SARS-CoV-2 in a mink farm in Italy: Case description, molecular and serological diagnosis by comparing different tests. Viruses 14(8):1738.

- Mistry P, Barmania F, Mellet J, Peta K, Strydom A, Viljoen IM, James W, Gordon S, Pepper MS (2022) SARS-CoV-2 variants, vaccines, and host immunity. Front Immunol 12:809244.

- Volz E, Mishra S, Chand M, Barrett JC, Johnson R, Geidelberg L, Hinsley WR, Laydon DJ, Dabrera G, O'Toole Á, et al.( 2021) Assessing transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 in England. Nature. 593(7858):266-269. [CrossRef]

- Murphy HL, Ly H (2021) Understanding the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) exposure in companion, captive, wild, and farmed animals. Virulence 12(1):2777-2786.

- Heneghan CJ, Spencer EA, Brassey J, Plüddemann A, Onakpoya IJ, Evans DH, Conly JM, Jefferson T (2021) SARS-CoV-2 and the role of orofecal transmission: a systematic review. F1000Res 10:231.

- Barberá-Riera M, de Llanos R, Barneo-Muñoz M, Bijlsma L, Celma A, Iñaki C, Gomila B, González-Candelas F, Goterris-Cerisuelo R, Martínez-García F, et al. (2023) Wastewater monitoring of a community COVID-19 outbreak in a Spanish municipality. J Environ Expo Assess 2(4):16.

- La Rosa G, Iaconelli M, Mancini P, Bonanno Ferraro G, Veneri C, Bonadonna L, Lucentini L, Suffredini E (2020) First detection of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewaters in Italy. Sci Total Environ 736:139652.

- Lamers MM, Haagmans BL (2022) SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 20(5):270-284.

- Hanson KE, Caliendo AM, Arias CA, Englund JA, Lee MJ, Loeb M, Patel R, El Alayli A, Kalot MA, Falck-Ytter Y, et al. (2024) Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines on the Diagnosis of COVID-19 (June 2020). Clin Infect Dis 78(7):e106–e132.

- Shuai L, Zhong G, Yuan Q, Wen Z, Wang C, He X, Liu R, Wang J, Zhao Q, Liu Y, et al. (2020) Replication, pathogenicity, and transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in minks. Natl Sci Rev 8(3):nwaa291.

- Jacobs JL, Bain W, Naqvi A, Staines B, Castanha PMS, Yang H, Boltz VF, Barratt-Boyes S, Marques ETA, Mitchell SL, et al. (2022) Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 viremia is associated with coronavirus disease 2019 severity and predicts clinical outcomes. Clin Infect Dis 74(9):1525-1533. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Study area and places where the animals were trapped. (A) Places where the present 60 animals were trapped are shown as white-filled circles except when a SARS-CoV-2-positive animal (identified by its number, referring to the leftmost column of

Table 1) was trapped, in which case the circle is filled in red. Rivers are shown in blue, and the locations of the closest farms of American mink are indicated with triangles (red-lined and grey-filled). The inset shows the Valencian Community (in black) within the Iberian peninsula. An arrow from the main panel shows what part of the Valencian Community is shown in this panel. The small inset within the inset shows the Iberian peninsula (in black) in the Mediterranean. (B and C) Places (in blue) in which animals were trapped and analyzed in the present study in the upper courses of the Palancia (B) and Mijares (C) rivers. The data given are for 73 animals, resulting from the pooling of the present 60 animals with the 13 animals tested in our previous pilot study (see the main text). The sites are located according to their UM coordinates (Northern hemisphere; earth surface section 30). For orientation, the municipalities to which the trapping sites belong are also located (black symbols and names), giving the same geometric shape to the municipality and its trapping sites. The size of the blue symbols increases with the number of animals trapped at a given site. In (B) this value goes from 1 to 8, and symbols have been represented in sizes 1 pt to 8 pt of GraphPad Prism, while in (C) the smaller symbols represent one trapped animal and the larger one two trapped animals. Sites where one animal was found to carry the SARS-CoV-2 virus are marked with red sword crosses, giving the date of trapping (encased in rectangles for the present report, giving outside the box the number of the animal). The sites where a pregnant female was found are marked in green, giving the animal number (

Table 1) and the word “(pregnant)”. The black lines in both panels link urban nuclei along the corresponding river, which in both cases flows from left to right. Thus, each one symbolizes a river course. In the Mijares river (C), its part after the village of Fanzara has been plotted according to the river coordinates to show the distance of the river course from the center of the city of Onda (~25,000 inhabitants).

Figure 1.

Study area and places where the animals were trapped. (A) Places where the present 60 animals were trapped are shown as white-filled circles except when a SARS-CoV-2-positive animal (identified by its number, referring to the leftmost column of

Table 1) was trapped, in which case the circle is filled in red. Rivers are shown in blue, and the locations of the closest farms of American mink are indicated with triangles (red-lined and grey-filled). The inset shows the Valencian Community (in black) within the Iberian peninsula. An arrow from the main panel shows what part of the Valencian Community is shown in this panel. The small inset within the inset shows the Iberian peninsula (in black) in the Mediterranean. (B and C) Places (in blue) in which animals were trapped and analyzed in the present study in the upper courses of the Palancia (B) and Mijares (C) rivers. The data given are for 73 animals, resulting from the pooling of the present 60 animals with the 13 animals tested in our previous pilot study (see the main text). The sites are located according to their UM coordinates (Northern hemisphere; earth surface section 30). For orientation, the municipalities to which the trapping sites belong are also located (black symbols and names), giving the same geometric shape to the municipality and its trapping sites. The size of the blue symbols increases with the number of animals trapped at a given site. In (B) this value goes from 1 to 8, and symbols have been represented in sizes 1 pt to 8 pt of GraphPad Prism, while in (C) the smaller symbols represent one trapped animal and the larger one two trapped animals. Sites where one animal was found to carry the SARS-CoV-2 virus are marked with red sword crosses, giving the date of trapping (encased in rectangles for the present report, giving outside the box the number of the animal). The sites where a pregnant female was found are marked in green, giving the animal number (

Table 1) and the word “(pregnant)”. The black lines in both panels link urban nuclei along the corresponding river, which in both cases flows from left to right. Thus, each one symbolizes a river course. In the Mijares river (C), its part after the village of Fanzara has been plotted according to the river coordinates to show the distance of the river course from the center of the city of Onda (~25,000 inhabitants).

Figure 2.

Illustrative agarose gel electrophoresis (top, 1% agarose; bottom, 2% agarose) of amplified products obtained by qPCR using for the indicated regions the primers given in the Materials and Methods, and, as templates, the cDNA retrotranscribed from the RNA isolated from the indicated samples. The positive control is a well-characterized retrotranscribed sample from a viral isolate of a human patient (not described here). The negative control used water as template.

Figure 2.

Illustrative agarose gel electrophoresis (top, 1% agarose; bottom, 2% agarose) of amplified products obtained by qPCR using for the indicated regions the primers given in the Materials and Methods, and, as templates, the cDNA retrotranscribed from the RNA isolated from the indicated samples. The positive control is a well-characterized retrotranscribed sample from a viral isolate of a human patient (not described here). The negative control used water as template.

Figure 3.

Body weights of the 60 feral mink studied here and images of a pregnancy in the May campaign. (A) Box and whishkers representation of the distribution of body weights among the 28 females and 32 males studied. The black and green lines that cross the box are, respectively, the median (females, 727 g; males, 1086 g) and mean (females 753±167 g; males 1125±190 g; the standard deviations are not shown in the figure). The bottom and top edges of the box define the first (Q1) and third (Q3) quartiles, and the whishkers give the total span of the measurements. The space between the blue transversal lines that cross the whishkers correspond to 1.5 times the range between Q1 and Q3 (interquartile range, IQR; for females, 642.5–808.5= 166 g; for males, 991–1308= 317 g) centered around the median. The dots represent individual animals, being red for SARS-CoV-2 positive animals, and blue for pregnant females. The p value shown indicates significative difference between the mean body weight for females and males with the probability level indicated (Student’s t-test). (B) Mean ± SD for body weight according to the sex and trapping campaigns. The number of animals for each bar is shown above it. Note that two groups had only 3 animals each. The **** and ** above the horizontal lines over the bars correspond to significant diffeences (Student’s t-test) between the corresponding means to respective p values of <0.0001 and 0.0063, respectively . The red and blue asteriks denote the number of, respectively, SARS-CoV-2 positive animals and pregnant females (diagnosed at necropsy), in the corresponding groups. (C-F) Plots of frequency distributions of the most populated groups defined by sex and campaign. The class intervals are defined in the labelling of the axes. Note the fitting to bimodal and even trimodal (C) distributions. The blue lines are the fitting of the data to Gaussian or sum of Gaussian bells (GraphPad plus software). In the bars in which one animal was SARS-CoV-2 positive, this individual is colored grey. In addition, pregnant females are indicated (D) in darker reddish color of their corresponding bars. (G) Pregnancy with 6 gestation sacs obtained at necropsy from the uterus of one of the three pregnant females. The inset shows detail of one of these sacs, opened to show the fetus, held in the gloved hand of the pathologist.

Figure 3.

Body weights of the 60 feral mink studied here and images of a pregnancy in the May campaign. (A) Box and whishkers representation of the distribution of body weights among the 28 females and 32 males studied. The black and green lines that cross the box are, respectively, the median (females, 727 g; males, 1086 g) and mean (females 753±167 g; males 1125±190 g; the standard deviations are not shown in the figure). The bottom and top edges of the box define the first (Q1) and third (Q3) quartiles, and the whishkers give the total span of the measurements. The space between the blue transversal lines that cross the whishkers correspond to 1.5 times the range between Q1 and Q3 (interquartile range, IQR; for females, 642.5–808.5= 166 g; for males, 991–1308= 317 g) centered around the median. The dots represent individual animals, being red for SARS-CoV-2 positive animals, and blue for pregnant females. The p value shown indicates significative difference between the mean body weight for females and males with the probability level indicated (Student’s t-test). (B) Mean ± SD for body weight according to the sex and trapping campaigns. The number of animals for each bar is shown above it. Note that two groups had only 3 animals each. The **** and ** above the horizontal lines over the bars correspond to significant diffeences (Student’s t-test) between the corresponding means to respective p values of <0.0001 and 0.0063, respectively . The red and blue asteriks denote the number of, respectively, SARS-CoV-2 positive animals and pregnant females (diagnosed at necropsy), in the corresponding groups. (C-F) Plots of frequency distributions of the most populated groups defined by sex and campaign. The class intervals are defined in the labelling of the axes. Note the fitting to bimodal and even trimodal (C) distributions. The blue lines are the fitting of the data to Gaussian or sum of Gaussian bells (GraphPad plus software). In the bars in which one animal was SARS-CoV-2 positive, this individual is colored grey. In addition, pregnant females are indicated (D) in darker reddish color of their corresponding bars. (G) Pregnancy with 6 gestation sacs obtained at necropsy from the uterus of one of the three pregnant females. The inset shows detail of one of these sacs, opened to show the fetus, held in the gloved hand of the pathologist.

Figure 4.

Alignment of the sequences obtained from SARS-CoV-2-positive mink, for the regions amplified in the qPCR reactions for the S, N and ORF10 gene regions. Wu1 refers to the consensus Wuhan- 1 sequence (GenBank NC_045512.2). Nucleotide numbering (above the sequence) is that for the Wuhan-1 consensus genome. The four sequences aligned with the Wuhan-1 genomic sequences are those for the positive animals (identified by the animal numbering as in

Table 1). In animal 29 only one sequence is given per gene despite our sequencing of cDNA obtained from swab, lymph node and lung tissue, since these viral sequences were identical. In the case of ORF10 the non-coding 3’flanking sequence determined is shown in low case and is numbered preceded by a + sign, also giving the number of the last base of the coding sequence. In the sequencing of the N gene there were a few bases showing ambiguity in the sequence. In these cases an M denotes A or C, and an N indicates the possibility of any base at that position. Sequence replacements with respect to the reference sequence are shown in red. Codon numbers are given below the aligned sequences; for clarity odd or even codon numbers are omitted. Amino acid residues are shown below the codon numbers in single-letter notation. Amino acids in red below the corresponding amino acid encoded by the Wuhan-1 consensus sequence (in black) give the amino acid substitutions encoded by the aligned sequences,with bases in red at the encoding codons.

Figure 4.

Alignment of the sequences obtained from SARS-CoV-2-positive mink, for the regions amplified in the qPCR reactions for the S, N and ORF10 gene regions. Wu1 refers to the consensus Wuhan- 1 sequence (GenBank NC_045512.2). Nucleotide numbering (above the sequence) is that for the Wuhan-1 consensus genome. The four sequences aligned with the Wuhan-1 genomic sequences are those for the positive animals (identified by the animal numbering as in

Table 1). In animal 29 only one sequence is given per gene despite our sequencing of cDNA obtained from swab, lymph node and lung tissue, since these viral sequences were identical. In the case of ORF10 the non-coding 3’flanking sequence determined is shown in low case and is numbered preceded by a + sign, also giving the number of the last base of the coding sequence. In the sequencing of the N gene there were a few bases showing ambiguity in the sequence. In these cases an M denotes A or C, and an N indicates the possibility of any base at that position. Sequence replacements with respect to the reference sequence are shown in red. Codon numbers are given below the aligned sequences; for clarity odd or even codon numbers are omitted. Amino acid residues are shown below the codon numbers in single-letter notation. Amino acids in red below the corresponding amino acid encoded by the Wuhan-1 consensus sequence (in black) give the amino acid substitutions encoded by the aligned sequences,with bases in red at the encoding codons.

Figure 5.

Molecular phylogenetic analyses based on partial gene sequences. These analyses used the regions defined by the consensus genome coordinates (GenBank accession number NC_045512.2) for nucleotides (A) 22,160-22,239 (corresponding to partial S gene sequence); (B) 28,871–28,964 (partial N gene sequence); and (C) 29,556–29,704 (partial ORF10 gene sequence). Our mink SARS-CoV-2 sequences are highlighted in bold type including at the end the appropriate GenBank Accession Numbers. Other sequences aligned have either Gisaid identifiers (EPI sequences) or GenBank identifiers (last group of characters in the row, when they have two initial capital letters followed by a six-digit number, in some cases followed by .1 or .2). DK, NLD and ITA correspond to Denmark, Netherlands and Italy. The trees are drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured according to the number of substitutions per site (see scale bars). The evolutionary history was inferred using the maximum likelihood method based on the Tamura–Nei model. In each case, the tree with the highest log likelihood is shown. Initial trees for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying the neighbor-join and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the maximum composite likelihood (MCL) approach and selecting the topology with superior log likelihood values.

Figure 5.

Molecular phylogenetic analyses based on partial gene sequences. These analyses used the regions defined by the consensus genome coordinates (GenBank accession number NC_045512.2) for nucleotides (A) 22,160-22,239 (corresponding to partial S gene sequence); (B) 28,871–28,964 (partial N gene sequence); and (C) 29,556–29,704 (partial ORF10 gene sequence). Our mink SARS-CoV-2 sequences are highlighted in bold type including at the end the appropriate GenBank Accession Numbers. Other sequences aligned have either Gisaid identifiers (EPI sequences) or GenBank identifiers (last group of characters in the row, when they have two initial capital letters followed by a six-digit number, in some cases followed by .1 or .2). DK, NLD and ITA correspond to Denmark, Netherlands and Italy. The trees are drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured according to the number of substitutions per site (see scale bars). The evolutionary history was inferred using the maximum likelihood method based on the Tamura–Nei model. In each case, the tree with the highest log likelihood is shown. Initial trees for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying the neighbor-join and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the maximum composite likelihood (MCL) approach and selecting the topology with superior log likelihood values.

Table 1.

Information on the mink studied here and on their trapping points. The coordinates given are those for the Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) system of the GPS location of the site at which each animal was trapped, for Sector 30 of the Northern hemisphere of the Earth surface. M, male; F, female. Bold type has been used to identify the animals animals that tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Table 1.

Information on the mink studied here and on their trapping points. The coordinates given are those for the Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) system of the GPS location of the site at which each animal was trapped, for Sector 30 of the Northern hemisphere of the Earth surface. M, male; F, female. Bold type has been used to identify the animals animals that tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

| Animal |

ID |

Trapping date |

Riverbed |

Belongs to |

Coordinates |

Weight (g) |

Sex |

| E: |

N: |

| 1 |

4618 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Navajas |

712,550 |

4,417,756 |

630 |

F |

| 2 |

4619 |

17/11/2020 |

Mijares |

Onda |

737,126 |

4,429,832 |

944 |

M |

| 3 |

4620 |

17/11/2020 |

Mijares |

Toga |

725,070 |

4,435,212 |

771 |

F |

| 4 |

4621 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Segorbe |

717,603 |

4,412,528 |

1010 |

M |

| 5 |

4622 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Soneja |

720,334 |

4,411,080 |

1109 |

F |

| 6 |

4623 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Soneja |

719,168 |

4,411,224 |

1412 |

M |

| 7 |

4624 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Soneja |

721,249 |

4,410,329 |

700 |

F |

| 8 |

4625 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Vall de Almonacid |

717,559 |

4,420,103 |

590 |

F |

| 9 |

4626 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Segorbe |

716,595 |

4,413,536 |

989 |

M |

| 10 |

4627 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Segorbe |

716,102 |

4,414,547 |

926 |

M |

| 11 |

4628 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Segorbe |

716,595 |

4,413,436 |

1098 |

M |

| 12 |

4629 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Segorbe |

716,102 |

4,414,547 |

787 |

F |

| 13 |

4630 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Jérica |

709,496 |

4,419,036 |

1083 |

M |

| 14 |

4631 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Navajas |

713,317 |

4,417,348 |

1201 |

M |

| 15 |

4632 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Navajas |

712,550 |

4,417,756 |

877 |

M |

| 16 |

4633 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Segorbe |

717,603 |

4,412,528 |

757 |

F |

| 17 |

4634 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Jérica |

709,496 |

4,419,036 |

1179 |

F |

| 18 |

4635 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Navajas |

712,550 |

4,417,756 |

993 |

M |

| 19 |

4636 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Navajas |

712,550 |

4,417,756 |

493 |

F |

| 20 |

4637 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Soneja |

720,334 |

4,411,080 |

646 |

F |

| 21 |

4638 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Jérica |

709,496 |

4,419,036 |

1089 |

M |

| 22 |

4639 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Segorbe |

716,595 |

4,413,436 |

1074 |

M |

| 23 |

4640 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Jérica |

708,547 |

4,419,355 |

1040 |

M |

| 24 |

4641 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Segorbe |

717,603 |

4,412,528 |

680 |

F |

| 25 |

4642 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Soneja |

719,168 |

4,411,224 |

728 |

M |

| 26 |

4643 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Viver |

705,722 |

4,420,834 |

598 |

F |

| 27 |

4644 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Jérica |

706,960 |

4,421,281 |

592 |

F |

| 28 |

4645 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Segorbe |

717,603 |

4,412,528 |

996 |

M |

| 29 |

4646 |

17/11/2020 |

Mijares |

Vallat |

727,495 |

4,434,312 |

736 |

F |

| 30 |

4647 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Jérica |

709,496 |

4,419,036 |

988 |

M |

| 31 |

4648 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Viver |

705,122 |

4,420,834 |

999 |

M |

| 32 |

4649 |

17/11/2020 |

Palancia |

Jérica |

706,960 |

4,421,281 |

639 |

F |

| 33 |

4650 |

17/11/2020 |

Mijares |

Espadilla |

726,089 |

4,434,535 |

847 |

F |

| 34 |

323 |

11/03/2021 |

Palancia |

Navajas |

712,550 |

4,417,756 |

916 |

M |

| 35 |

324 |

11/03/2021 |

Palancia |

Soneja |

720,334 |

4,411,080 |

1073 |

M |

| 36 |

325 |

11/03/2021 |

Palancia |

Segorbe |

716,102 |

4,414,547 |

1305 |

M |

| 37 |

326 |

11/03/2021 |

Palancia |

Jérica |

709,496 |

4,419,036 |

1432 |

M |

| 38 |

327 |

11/03/2021 |

Palancia |

Soneja |

720,334 |

4,411,080 |

1418 |

M |

| 39 |

328 |

11/03/2021 |

Palancia |

Navajas |

713,317 |

4,417,348 |

633 |

F |

| 40 |

329 |

11/03/2021 |

Palancia |

Soneja |

720,334 |

4,411,080 |

1102 |

M |

| 41 |

330 |

11/03/2021 |

Palancia |

Navajas |

712,550 |

4,417,756 |

777 |

F |

| 42 |

331 |

11/03/2021 |

Palancia |

Viver |

704,779 |

4,419,830 |

1229 |

M |

| 43 |

332 |

11/03/2021 |

Palancia |

Segorbe |

716.595 |

4,413,436 |

873 |

M |

| 44 |

333 |

11/03/2021 |

Mijares |

Toga |

724,069 |

4,435,762 |

1311 |

M |

| 45 |

334 |

11/03/2021 |

Palancia |

Soneja |

719,168 |

4,411,224 |

1164 |

M |

| 46 |

335 |

11/03/2021 |

Palancia |

Soneja |

720,334 |

4,411,080 |

1340 |

M |

| 47 |

336 |

11/03/2021 |

Palancia |

Jérica |

706,960 |

4,421,281 |

680 |

F |

| 48 |

337 |

11/03/2021 |

Palancia |

Navajas |

713,317 |

4,417,348 |

1311 |

M |

| 49a

|

1000 |

03/05/2022 |

Palancia |

Gaibiel |

715,043b

|

4,423,390b

|

985 |

F |

| 50 |

1007 |

03/05/2022 |

Palancia |

Jérica |

706,960 |

4,421,281 |

765 |

F |

| 51 |

1008 |

03/05/2022 |

Palancia |

Segorbe |

717,603 |

4,412,528 |

867 |

F |

| 52a

|

1009 |

03/05/2022 |

Palancia |

Jérica |

706,960 |

4,421,281 |

830 |

F |

| 53 |

1010 |

03/05/2022 |

Palancia |

Jérica |

709,496 |

4,419,036 |

1421 |

M |

| 54a

|

1013 |

03/05/2022 |

Palancia |

Jérica |

709,496 |

4,419,036 |

897 |

F |

| 55 |

1014 |

03/05/2022 |

Palancia |

Jérica |

709,496 |

4,419,036 |

1389 |

M |

| 56 |

1022 |

03/05/2022 |

Palancia |

Teresa |

700,530 |

4,419,107 |

702 |

F |

| 57 |

1023 |

03/05/2022 |

Mijares |

Montanejos |

712,777 |

4,439,177 |

773 |

F |

| 58 |

1024 |

03/05/2022 |

Mijares |

Toga |

724,069 |

4,435,762 |

1266 |

M |

| 59 |

1025 |

03/05/2022 |

Palancia |

Segorbe |

714,680 |

4,416,113 |

718 |

F |

| 60 |

1026 |

03/05/2022 |

Mijares |

Toga |

725,070 |

4,435,212 |

711 |

F |

Table 2.

Animals and samples that were positive for SARS-CoV-2 by qPCR, and changes identified in the sequenced regions.

Table 2.

Animals and samples that were positive for SARS-CoV-2 by qPCR, and changes identified in the sequenced regions.

| Positive animala

|

Sample |

qPCR results as Ct values

Change in the coding sequence of the gene

Change in the amino acid sequence of the proteinb

|

|

Sc

|

N |

ORF10 |

| 16 |

Swab (nasal) |

31.3 |

32.1

N:659C > T

N: A220V |

29.1

ORF10: 88G>T

ORF10: V30L |

| 29 |

Swab (rectal) |

29.4 |

32.3

N: 608-610 GGG > AAC

N: R203K/G204R |

20.2

ORF10: 88G>T

ORF10: V30L |

| Lymph node (mediastinal) |

30.9 |

32.1

N: 608-610 GGG > AAC

N: R203K/G204R |

22.8

ORF10: 88G>T

ORF10: V30L |

| Lung tissue |

30.9 |

32.1

N: 608-610 GGG > AAC

N: R203K/G204R |

21.3

ORF10: 88G>T

ORF10: V30L |

| 40 |

Swab (nasal) |

32.9 |

32.7

N:659C > T

N: A220V |

29.3

ORF10: 88G>T

ORF10: V30L |

| 56 |

Swab (rectal) |

29.0 |

34.4

N: 608-610 GGG > AAC

N: R203K/G204R |

24.9

ORF10: 88G>T

ORF10: V30L |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).