Submitted:

08 October 2025

Posted:

09 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

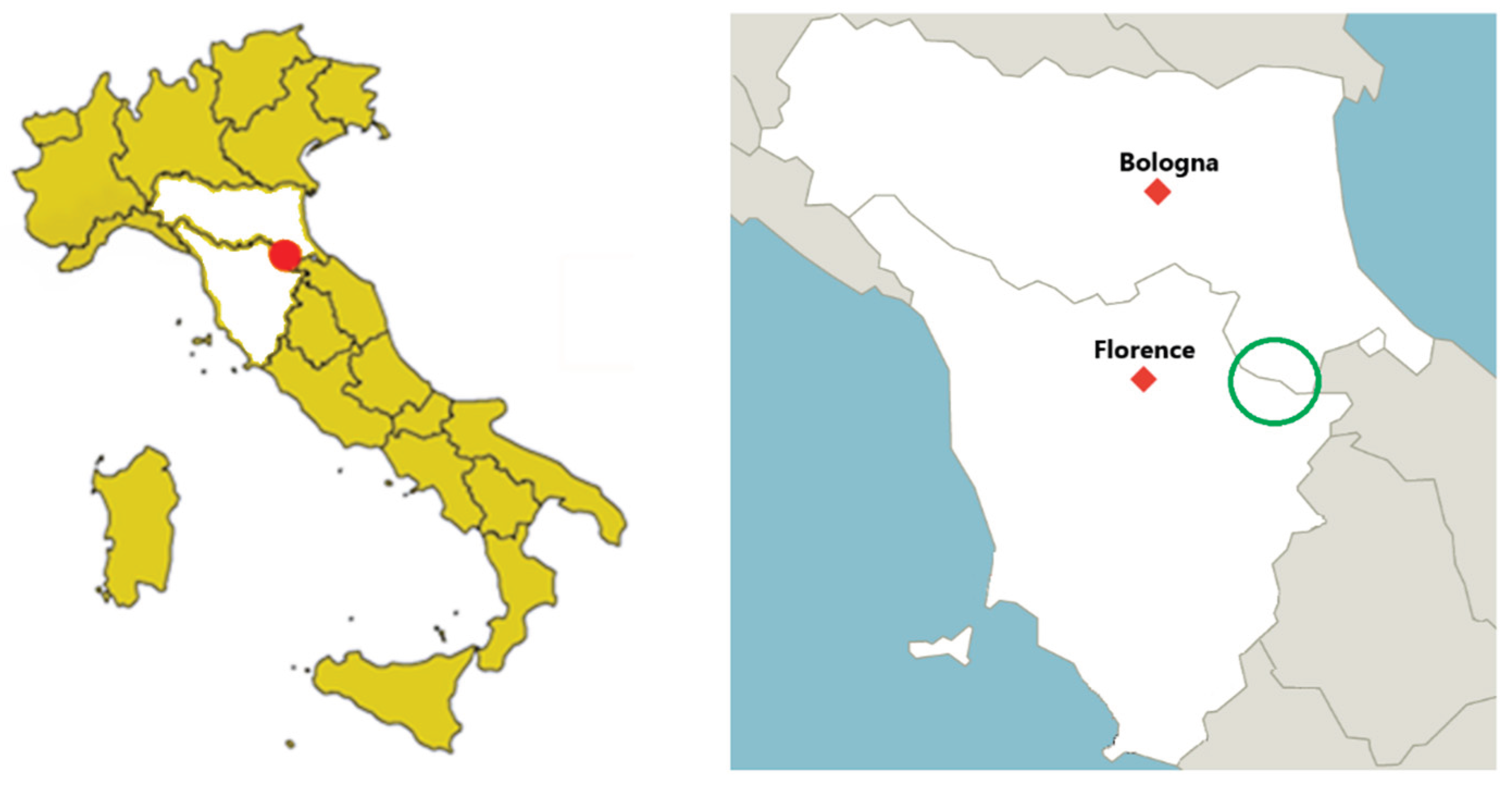

2.1. Foreste Casentinesi National Park (PNFC)

2.2. Sampling

2.3. Sample Processing and PCR

2.3.1. PCR Screening

2.4. Metagenomics Analysis

2.5. Bioinformatics

3. Results

3.1. Sample Collection and Pool Preparation

3.2. PCR Results

3.2.1. GenBank Submission and BLAST Analysis

3.3. Metagenomic Analysis

3.3.1. In-depth Bioinformatic Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Canine parvovirus (CPV) |

| Canine adenovirus type 1 (CAdV-1) |

| Canine distemper virus (CDV) |

| Bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) |

| Bovine papillomavirus (BopV) |

| Canine circovirus (CCoV) |

| Torque teno viruses (TTV1 and TTV2) |

| Adenovirus (AdV) |

| Rodent Adenovirus (RAdV) |

| Mastadenovirus (MAdV) |

| Postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome (PMWS) |

| Rodent Mastadenovirus (RMAdV) |

| Squirrel adenovirus (SqAdv) |

| Canine astrovirus (CAsV) |

| Bokaviru (BoV) |

| Kobuvirus (KoV) |

| Canine Kobuvirus (CaKoV) |

| Capreolus capreolus astrovirus (CcAstV) |

| Wet Mink Syndrome (WMS) |

| Lutrine adenovirus (LAdV-1) |

| Picobirnavirus (PBV) |

| Porcine circovirus (PCV) |

| Parco Nazionale Foreste Casentinesi (PNFC) |

Appendix A

| [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14] | AdV | PV | BoV | CV | TTV | V | AstV | CoV | PeV | BoPV | MoV | References |

| Roe deer | AdV spp. * | - | BoV spp. * | - | - | KoV spp. * | AstV spp. * | CoV spp. * | BVDV | BopV spp. * | - | [48,83,84,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161] |

| Fallow deer | AdV spp. * | - | BoV spp. * | - | - | KoV spp. * | AstV spp. * | CoV spp. * | BVDV | BopV spp. * | - | |

| Red deer | AdV spp. * | - | BoV spp. * | - | - | KoV spp. * | AstV spp. * | CoV spp. * | BVDV | BopV spp. * | - | |

| Red fox |

CAdV 1,2 AdV spp. * |

CPV FPV |

CBoV 1,2,3 BoV spp. * |

CCV | - | KoV spp. * | AstV spp. * | CoV spp. * | - | - | CDV | [54,55,67,87,114,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171] |

| Wolf |

CAdV 1,2 AdV spp. * |

CPV FPV |

LBoV CBoV 1,2,3 BoV spp. * |

CCV | - | KoV spp. * | AstV spp. * | CoV spp. * | - | - | CDV | [57,153,162,163,164,166,170,171,172,173] |

| Badger |

CAdV 1,2 AdV spp. * |

CPV FPV |

BoV spp. * | - | TTV 1,2 | KoV spp. * | AstV spp. * | CoV spp. * | - | - | CDV | [54,162,166,167,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183] |

| Small mustelids |

CAdV 1,2 AdV spp. * |

CPV FPV |

BoV spp. * | - | TTV 1,2 | KoV spp. * | AstV spp. * | CoV spp. * | - | - | CDV | |

| Porcupine | AdV spp. * | - | BoV spp. * | - | - | KoV spp. * | AstV spp* | CoV spp. * | - | - | - | [45,87,177,184,185,186,187] |

References

- Daszak, P.; Cunningham, A.A.; Hyatt, A.D. Emerging Infectious Diseases of Wildlife-- Threats to Biodiversity and Human Health. Science 2000, 287, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, R. Drivers of Disease Emergence and Spread: Is Wildlife to Blame? Onderstepoort J Vet Res 2014, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, M.N.F. The Concept of One Health Applied to the Problem of Zoonotic Diseases. Reviews in Medical Virology 2022, 32, e2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcês, A.; Pires, I. Secrets of the Astute Red Fox (Vulpes Vulpes, Linnaeus, 1758): An Inside-Ecosystem Secret Agent Serving One Health. Environments 2021, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wobeser, G.A. Disease in Wild Animals; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007; Vol. 315, pp. 445–461. ISBN 978-3-540-48974-0. [Google Scholar]

- Breed, D.; Meyer, L.C.R.; Steyl, J.C.A.; Goddard, A.; Burroughs, R.; Kohn, T.A. Conserving Wildlife in a Changing World: Understanding Capture Myopathy—a Malignant Outcome of Stress during Capture and Translocation. Conservation Physiology 2019, 7, coz027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arumugam, R.; Uli, J.E.; Annavi, G. A Review of the Application of Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) in Wild Terrestrial Vertebrate Research. ARRB 2019, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodewes, R.; Ruiz-Gonzalez, A.; Schapendonk, C.M.E.; Van Den Brand, J.M.A.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Smits, S.L. Viral Metagenomic Analysis of Feces of Wild Small Carnivores. Virology Journal 2014, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, W.; He, B.; Jiang, T.; Li, Y.; Xia, L.; Feng, Y.; Fan, Q.; Tu, C. [Metagenomic analysis of bat virome in several Chinese regions]. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao 2013, 29, 586–600. [Google Scholar]

- Blomström, A.-L.; Ståhl, K.; Masembe, C.; Okoth, E.; Okurut, A.R.; Atmnedi, P.; Kemp, S.; Bishop, R.; Belák, S.; Berg, M. Viral Metagenomic Analysis of Bushpigs (Potamochoerus Larvatus) in Uganda Identifies Novel Variants of Porcine Parvovirus 4 and Torque Teno Sus Virus 1 and 2. Virol J 2012, 9, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodewes, R.; van der Giessen, J.; Haagmans, B.L.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Smits, S.L. Identification of Multiple Novel Viruses, Including a Parvovirus and a Hepevirus, in Feces of Red Foxes. Journal of Virology 2013, 87, 7758–7764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, G.; Nemes, C.; Boros, Á.; Kapusinszky, B.; Delwart, E.; Pankovics, P. Astrovirus in Wild Boars (Sus Scrofa) in Hungary. Arch Virol 2012, 157, 1143–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, C.A.; Altizer, S. Urbanization and the Ecology of Wildlife Diseases. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2007, 22, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abade Dos Santos, F.A.; Pinto, A.; Burgoyne, T.; Dalton, K.P.; Carvalho, C.L.; Ramilo, D.W.; Carneiro, C.; Carvalho, T.; Peleteiro, M.C.; Parra, F.; et al. Spillover Events of Rabbit Haemorrhagic Disease Virus 2 (Recombinant GI.4P-GI.2) from Lagomorpha to Eurasian Badger. Transbounding Emerging Dis 2022, 69, 1030–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrish, C.R.; Holmes, E.C.; Morens, D.M.; Park, E.-C.; Burke, D.S.; Calisher, C.H.; Laughlin, C.A.; Saif, L.J.; Daszak, P. Cross-Species Virus Transmission and the Emergence of New Epidemic Diseases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2008, 72, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.M.; Sauer, E.L.; Santiago, O.; Spencer, S.; Rohr, J.R. Divergent Impacts of Warming Weather on Wildlife Disease Risk across Climates. Science 2020, 370, eabb1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, G.; Stout, A. Coronaviruses in Wild Canids: A Review of the Literature. Qeios 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, A.B.; Kohler, D.J.; Fox, K.A.; Brown, J.D.; Gerhold, R.W.; Shearn-Bochsler, V.I.; Dubovi, E.J.; Parrish, C.R.; Holmes, E.C. Frequent Cross-Species Transmission of Parvoviruses among Diverse Carnivore Hosts. J Virol 2013, 87, 2342–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallknecht, D.E. Impediments to Wildlife Disease Surveillance, Research, and Diagnostics. In Wildlife and Emerging Zoonotic Diseases: The Biology, Circumstances and Consequences of Cross-Species Transmission; Childs, J.E., Mackenzie, J.S., Richt, J.A., Eds.; Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007; ISBN 978-3-540-70961-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ochola, G.O.; Li, B.; Obanda, V.; Ommeh, S.; Ochieng, H.; Yang, X.-L.; Onyuok, S.O.; Shi, Z.-L.; Agwanda, B.; Hu, B. Discovery of Novel DNA Viruses in Small Mammals from Kenya. Virologica Sinica 2022, 37, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennehy, J.J. Evolutionary Ecology of Virus Emergence. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2017, 1389, 124–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellehan, J.F.X.; Johnson, A.J.; Harrach, B.; Benkö, M.; Pessier, A.P.; Johnson, C.M.; Garner, M.M.; Childress, A.; Jacobson, E.R. Detection and Analysis of Six Lizard Adenoviruses by Consensus Primer PCR Provides Further Evidence of a Reptilian Origin for the Atadenoviruses. Journal of Virology 2004, 78, 13366–13369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.L.; Huang, G.; Qiu, W.; Zhong, Z.H.; Xia, X.Z.; Yin, Z. Detection and Differentiation of CAV-1 and CAV-2 by Polymerase Chain Reaction. Veterinary research communications 2001, 25, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatzberg, S.J.; Haley, N.J.; Barr, S.C.; Parrish, C.; Steingold, S.; Summers, B.A.; Delahunta, A.; Kornegay, J.N.; Sharp, N.J.H. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Amplification of Parvoviral DNA from the Brains of Dogs and Cats with Cerebellar Hypoplasia. Wiley Online Library 2003, 17, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiana, L.A.; Lanave, G.; Desario, C.; Berjaoui, S.; Alfano, F.; Puglia, I.; Fusco, G.; Colaianni, M.L.; Vincifori, G.; Camarda, A.; et al. Circulation of Diverse Protoparvoviruses in Wild Carnivores, Italy. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases 2021, 68, 2489–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.K.P.; Woo, P.C.Y.; Yeung, H.C.; Teng, J.L.L.; Wu, Y.; Bai, R.; Fan, R.Y.Y.; Chan, K.H.; Yuen, K.Y. Identification and Characterization of Bocaviruses in Cats and Dogs Reveals a Novel Feline Bocavirus and a Novel Genetic Group of Canine Bocavirus. Journal of General Virology 2012, 93, 1573–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, A.; Mehta, N.; Dubovi, E.J.; Simmonds, P.; Govindasamy, L.; Medina, J.L.; Street, C.; Shields, S.; Ian Lipkin, W. Characterization of Novel Canine Bocaviruses and Their Association with Respiratory Disease. The Journal of General Virology 2012, 93, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Pesavento, P.A.; Leutenegger, C.M.; Estrada, M.; Coffey, L.L.; Naccache, S.N.; Samayoa, E.; Chiu, C.; Qiu, J.; Wang, C.; et al. A Novel Bocavirus in Canine Liver. Virology Journal 2013, 10, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição-Neto, N.; Godinho, R.; Álvares, F.; Yinda, C.K.; Deboutte, W.; Zeller, M.; Laenen, L.; Heylen, E.; Roque, S.; Petrucci-Fonseca, F.; et al. Viral Gut Metagenomics of Sympatric Wild and Domestic Canids, and Monitoring of Viruses: Insights from an Endangered Wolf Population. Ecology and Evolution 2017, 7, 4135–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboni, A.; Urbani, L.; Delogu, M.; Musto, C.; Fontana, M.C.; Merialdi, G.; Lucifora, G.; Terrusi, A.; Dondi, F.; Battilani, M. Integrated Use of Molecular Techniques to Detect and Genetically Characterise Dna Viruses in Italian Wolves (Canis Lupus Italicus). Animals 2021, 11, 2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segalés, J.; Martínez-Guinó, L.; Cortey, M.; Navarro, N.; Huerta, E.; Sibila, M.; Pujols, J.; Kekarainen, T. Retrospective Study on Swine Torque Teno Virus Genogroups 1 and 2 Infection from 1985 to 2005 in Spain. Veterinary Microbiology 2009, 134, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuter, G.; Boldizsár, Á.; Pankovics, P. Complete Nucleotide and Amino Acid Sequences and Genetic Organization of Porcine Kobuvirus, a Member of a New Species in the Genus Kobuvirus, Family Picornaviridae. Archives of Virology 2009, 154, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.K.W.; Poon, L.L.M.; Guan, Y.; Peiris, J.S.M. Novel Astroviruses in Insectivorous Bats. Journal of Virology 2008, 82, 9107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.K.W.; Leung, C.Y.H.; Gilbert, M.; Joyner, P.H.; Ng, E.M.; Tse, T.M.; Guan, Y.; Peiris, J.S.M.; Poon, L.L.M. Avian Coronavirus in Wild Aquatic Birds. Journal of Virology 2011, 85, 12815–12820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilček, S.; Herring, A.J.; Herring, J.A.; Nettleton, P.F.; Lowings, J.P.; Paton, D.J. Pestiviruses Isolated from Pigs, Cattle and Sheep Can Be Allocated into at Least Three Genogroups Using Polymerase Chain Reaction and Restriction Endonuclease Analysis. Archives of Virology 1994, 136, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- László, Z.; Pankovics, P.; Reuter, G.; Cságola, A.; Bálint, Á.; Albert, M.; Boros, Á. Multiple Types of Novel Enteric Bopiviruses (Picornaviridae) with the Possibility of Interspecies Transmission Identified from Cloven-Hoofed Domestic Livestock (Ovine, Caprine and Bovine) in Hungary. Viruses 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokili, J.L.; Rohwer, F.; Dutilh, B.E. Metagenomics and Future Perspectives in Virus Discovery. Current Opinion in Virology 2012, 2, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes, G.R.; Kim, J.P. Sequence-Independent, Single-Primer Amplification (SISPA) of Complex DNA Populations. Molecular and Cellular Probes 1991, 5, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrzastek, K.; Lee, D.; Smith, D.; Sharma, P.; Suarez, D.L.; Pantin-Jackwood, M.; Kapczynski, D.R. Use of Sequence-Independent, Single-Primer-Amplification (SISPA) for Rapid Detection, Identification, and Characterization of Avian RNA Viruses. Virology 2017, 509, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacini, M.I.; Forzan, M.; Sgorbini, M.; Cingottini, D.; Mazzei, M. Metagenomic Analysis of the Fecal Virome in Wild Mammals Hospitalized in Pisa, Italy. Veterinary Sciences 2025, 12, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarchese, V.; Fruci, P.; Palombieri, A.; Di Profio, F.; Robetto, S.; Ercolini, C.; Orusa, R.; Marsilio, F.; Martella, V.; Di Martino, B. Molecular Identification and Characterization of a Genotype 3 Hepatitis E Virus (HEV) Strain Detected in a Wolf Faecal Sample, Italy. Animals 2021, 11, 3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shan, T.; Wang, C.; Côté, C.; Kolman, J.; Onions, D.; Gulland, F.M.D.; Delwart, E. The Fecal Viral Flora of California Sea Lions. J Virol 2011, 85, 9909–9917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergner, L.M.; Orton, R.J.; Da Silva Filipe, A.; Shaw, A.E.; Becker, D.J.; Tello, C.; Biek, R.; Streicker, D.G. Using Noninvasive Metagenomics to Characterize Viral Communities from Wildlife. Molecular Ecology Resources 2019, 19, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Brand, J.M.A.; van Leeuwen, M.; Schapendonk, C.M.; Simon, J.H.; Haagmans, B.L.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Smits, S.L. Metagenomic Analysis of the Viral Flora of Pine Marten and European Badger Feces. Journal of Virology 2012, 86, 2360–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.G.; Kapusinszky, B.; Wang, C.; Rose, R.K.; Lipton, H.L.; Delwart, E.L. The Fecal Viral Flora of Wild Rodents. PLoS Pathog 2011, 7, e1002218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Martínez, L.A.; Loza-Rubio, E.; Mosqueda, J.; González-Garay, M.L.; García-Espinosa, G. Fecal Virome Composition of Migratory Wild Duck Species. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, Y.; Xu, J.; Duan, Z. A Novel Cardiovirus Species Identified in Feces of Wild Himalayan Marmots. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2022, 103, 105347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huaman, J.L.; Pacioni, C.; Sarker, S.; Doyle, M.; Forsyth, D.M.; Pople, A.; Carvalho, T.G.; Helbig, K.J. Novel Picornavirus Detected in Wild Deer: Identification, Genomic Characterisation, and Prevalence in Australia. Viruses 2021, 13, 2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutjes, S.A.; Lodder-Verschoor, F.; Lodder, W.J.; Van Der Giessen, J.; Reesink, H.; Bouwknegt, M.; De Roda Husman, A.M. Seroprevalence and Molecular Detection of Hepatitis E Virus in Wild Boar and Red Deer in The Netherlands. Journal of Virological Methods 2010, 168, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vibin, J.; Chamings, A.; Collier, F.; Klaassen, M.; Nelson, T.M.; Alexandersen, S. Metagenomics Detection and Characterisation of Viruses in Faecal Samples from Australian Wild Birds. Sci Rep 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Liu, D.; Wang, Y.; Qu, F.; He, Y.; Sun, Z.; Shen, Q.; Li, W.; Fu, X.; Deng, X.; et al. Bufavirus Protoparvovirus in Feces of Wild Rats in China. Virus Genes 2016, 52, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ao, Y.; Xu, J.; Duan, Z. A Novel Cardiovirus Species Identified in Feces of Wild Himalayan Marmots. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2022, 103, 105347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuter, G.; Boros, Á.; Földvári, G.; Szekeres, S.; Mátics, R.; Kapusinszky, B.; Delwart, E.; Pankovics, P. Dicipivirus (Family Picornaviridae) in Wild Northern White-Breasted Hedgehog (Erinaceus Roumanicus). Arch Virol 2018, 163, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodewes, R.; Ruiz-Gonzalez, A.; Schapendonk, C.M.; Van Den Brand, J.M.; Osterhaus, A.D.; Smits, S.L. Viral Metagenomic Analysis of Feces of Wild Small Carnivores. Virol J 2014, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodewes, R.; Van Der Giessen, J.; Haagmans, B.L.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Smits, S.L. Identification of Multiple Novel Viruses, Including a Parvovirus and a Hepevirus, in Feces of Red Foxes. J Virol 2013, 87, 7758–7764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Brand, J.M.A.; Van Leeuwen, M.; Schapendonk, C.M.; Simon, J.H.; Haagmans, B.L.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Smits, S.L. Metagenomic Analysis of the Viral Flora of Pine Marten and European Badger Feces. J Virol 2012, 86, 2360–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinello, F.; Galuppo, F.; Ostanello, F.; Guberti, V.; Prosperi, S. Detection of Canine Parvovirus in Wolves from Italy. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 1997, 33, 628–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olarte-Castillo, X.A.; Heeger, F.; Mazzoni, C.J.; Greenwood, A.D.; Fyumagwa, R.; Moehlman, P.D.; Hofer, H.; East, M.L. Molecular Characterization of Canine Kobuvirus in Wild Carnivores and the Domestic Dog in Africa. Virology 2015, 477, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannwitz, G.; Wolf, C.; Harder, T. Active Surveillance for Avian Influenza Virus Infection in Wild Birds by Analysis of Avian Fecal Samples from the Environment. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 2009, 45, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, P.W.; Fleming, P.A. Big City Life: Carnivores in Urban Environments. Journal of Zoology 2012, 287, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcês, A.; Pires, I. Secrets of the Astute Red Fox (Vulpes Vulpes, Linnaeus, 1758): An Inside-Ecosystem Secret Agent Serving One Health. Environments 2021, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsolini, S.; Burrini, L.; Focardi, S.; Lovari, S. How Can We Use the Red Fox as a Bioindicator of Organochlorines? Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2000, 39, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalisińska, E.; Palczewska-Komsa, M. Teeth of the Red Fox Vulpes Vulpes (L., 1758) as a Bioindicator in Studies on Fluoride Pollution. Acta Theriol 2011, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, S.S.; Urdahl, A.M.; Madslien, K.; Sunde, M.; Nesse, L.L.; Slettemeås, J.S.; Norström, M. What Does the Fox Say? Monitoring Antimicrobial Resistance in the Environment Using Wild Red Foxes as an Indicator. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.J.; Ashley, W.; Gil-Fernandez, M.; Newsome, T.M.; Di Giallonardo, F.; Ortiz-Baez, A.S.; Mahar, J.E.; Towerton, A.L.; Gillings, M.; Holmes, E.C.; et al. Red Fox Viromes in Urban and Rural Landscapes. Virus Evolution 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.I.; Blanton, J.D.; Gilbert, A.; Castrodale, L.; Hueffer, K.; Slate, D.; Rupprecht, C.E. A Conceptual Model for the Impact of Climate Change on Fox Rabies in Alaska, 1980–2010. Zoonoses and Public Health 2014, 61, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martella, V.; Pratelli, A.; Cirone, F.; Zizzo, N.; Decaro, N.; Tinelli, A.; Foti, M.; Buonavoglia, C. Detection and Genetic Characterization of Canine Distemper Virus (CDV) from Free-Ranging Red Foxes in Italy. Molecular and Cellular Probes 2002, 16, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martella, V.; Bianchi, A.; Bertoletti, I.; Pedrotti, L.; Gugiatti, A.; Catella, A.; Cordioli, P.; Lucente, M.S.; Elia, G.; Buonavoglia, C. Canine Distemper Epizootic among Red Foxes, Italy, 2009. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010, 16, 2007–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianco, A.; Zecchin, B.; Fusaro, A.; Schivo, A.; Ormelli, S.; Bregoli, M.; Citterio, C.V.; Obber, F.; Dellamaria, D.; Trevisiol, K.; et al. Two Waves of Canine Distemper Virus Showing Different Spatio-Temporal Dynamics in Alpine Wildlife (2006–2018). Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2020, 84, 104359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasio, A.D.; Irico, L.; Caruso, C.; Miceli, I.; Robetto, S.; Peletto, S.; Varello, K.; Giorda, F.; Mignone, W.; Rubinetti, F.; et al. CANINE DISTEMPER VIRUS AS AN EMERGING MULTIHOST PATHOGEN IN WILD CARNIVORES IN NORTHWEST ITALY. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 2019, 55, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trogu, T.; Canziani, S.; Salvato, S.; Bianchi, A.; Bertoletti, I.; Gibelli, L.R.; Alborali, G.L.; Barbieri, I.; Gaffuri, A.; Sala, G.; et al. Canine Distemper Outbreaks in Wild Carnivores in Northern Italy. Viruses 2021, 13, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouvellet, P.; Donnelly, C.A.; De Nardi, M.; Rhodes, C.J.; De Benedictis, P.; Citterio, C.; Obber, F.; Lorenzetto, M.; Pozza, M.D.; Cauchemez, S.; et al. Rabies and Canine Distemper Virus Epidemics in the Red Fox Population of Northern Italy (2006–2010). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monne, I.; Fusaro, A.; Valastro, V.; Citterio, C.; Pozza, M.D.; Obber, F.; Trevisiol, K.; Cova, M.; De Benedictis, P.; Bregoli, M.; et al. A Distinct CDV Genotype Causing a Major Epidemic in Alpine Wildlife. Veterinary Microbiology 2011, 150, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrogi, C.; Ragagli, C.; Decaro, N.; Ferroglio, E.; Mencucci, M.; Apollonio, M.; Mannelli, A. Health Survey on the Wolf Population in Tuscany, Italy. Hystrix 2019, 30, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Francesco, C.E.; Smoglica, C.; Paoletti, B.; Angelucci, S.; Innocenti, M.; Antonucci, A.; Di Domenico, G.; Marsilio, F. Detection of Selected Pathogens in Apennine Wolf (Canis Lupus Italicus) by a Non-Invasive GPS-Based Telemetry Sampling of Two Packs from Majella National Park, Italy. Eur J Wildl Res 2019, 65, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Arcangeli, S.; Balboni, A.; Kaehler, E.; Urbani, L.; Verin, R.; Battilani, M. Genomic Characterization of Canine Circovirus Detected in Red Foxes (Vulpes Vulpes) from Italy Using a New Real-Time PCR Assay. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 2020, 56, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzo, G.; Menandro, M.L.; Tucciarone, C.M.; Barbierato, G.; Crovato, L.; Mondin, A.; Libanora, M.; Obber, F.; Orusa, R.; Robetto, S.; et al. Canine Circovirus in Foxes from Northern Italy: Where Did It All Begin? Pathogens 2021, 10, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccaria, G.; Malatesta, D.; Scipioni, G.; Di Felice, E.; Campolo, M.; Casaccia, C.; Savini, G.; Di Sabatino, D.; Lorusso, A. Circovirus in Domestic and Wild Carnivores: An Important Opportunistic Agent? Virology 2016, 490, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci, S.; Bartolini, S.; Morandi, F.; Cuteri, V.; Preziuso, S. Genotyping of Pestivirus A (Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus 1) Detected in Faeces and in Other Specimens of Domestic and Wild Ruminants at the Wildlife-Livestock Interface. Veterinary Microbiology 2019, 235, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olde Riekerink, R.G.M.; Dominici, A.; Barkema, H.W.; De Smit, A.J. Seroprevalence of Pestivirus in Four Species of Alpine Wild Ungulates in the High Valley of Susa, Italy. Veterinary Microbiology 2005, 108, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citterio, C.V.; Luzzago, C.; Sala, M.; Sironi, G.; Gatti, P.; Gaffuri, A.; Lanfranchi, P. Serological Study of a Population of Alpine Chamois ( Rupkapra Rrupkapra ) Affected by an Outbreak of Respiratory Disease. Veterinary Record 2003, 153, 592–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffuri, A.; Giacometti, M.; Tranquillo, V.M.; Magnino, S.; Cordioli, P.; Lanfranchi, P. Serosurvey of Roe Deer, Chamois and Domestic Sheep in the Central Italian Alps. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 2006, 42, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, S.L.; Van Leeuwen, M.; Kuiken, T.; Hammer, A.S.; Simon, J.H.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E. Identification and Characterization of Deer Astroviruses. Journal of General Virology 2010, 91, 2719–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamnikar-Ciglenecki, U.; Civnik, V.; Kirbis, A.; Kuhar, U. A Molecular Survey, Whole Genome Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis of Astroviruses from Roe Deer. BMC Vet Res 2020, 16, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzipori, S.; Menzies, J.; Gray, E. Detection of Astrovirus in the Faeces of Red Deer. Veterinary Record 1981, 108, 286–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Shen, H.; Zheng, Y.; Schumacher, L.; Li, G. Astrovirus in White-Tailed Deer, United States, 2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Chmura, A.A.; Li, J.; Zhu, G.; Desmond, J.S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Epstein, J.H.; Daszak, P.; Shi, Z. Detection of Diverse Novel Astroviruses from Small Mammals in China. Journal of General Virology 2014, 95, 2442–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, S.L.; Raj, V.S.; Oduber, M.D.; Schapendonk, C.M.E.; Bodewes, R.; Provacia, L.; Stittelaar, K.J.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Haagmans, B.L. Metagenomic Analysis of the Ferret Fecal Viral Flora. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e71595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubczak, A.; Kowalczyk, M.; Mazurkiewicz, I.; Kondracki, M. Detection of Mink Astrovirus in Poland and Further Phylogenetic Comparison with Other European and Canadian Astroviruses. Virus Genes 2021, 57, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolores, G.-W.; Caroline, B.; Hans, H.D.; Englund, L.; Anne, S.H.; Hedlund, K.-O.; Carl Hård Af, S.; Nilsson, K.; Nowotny, N.; Puurula, V.; et al. Investigations into Shaking Mink Syndrome: An Encephalomyelitis of Unknown Cause in Farmed Mink ( Mustela Vison ) Kits in Scandinavia. J VET Diagn Invest 2004, 16, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomström, A.-L.; Widén, F.; Hammer, A.-S.; Belák, S.; Berg, M. Detection of a Novel Astrovirus in Brain Tissue of Mink Suffering from Shaking Mink Syndrome by Use of Viral Metagenomics. J Clin Microbiol 2010, 48, 4392–4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, B.; Di Profio, F.; Melegari, I.; Robetto, S.; Di Felice, E.; Orusa, R.; Marsilio, F. Molecular Evidence of Kobuviruses in Free-Ranging Red Foxes (Vulpes Vulpes). Archives of Virology 2014, 159, 1803–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melegari, I.; Sarchese, V.; Di Profio, F.; Robetto, S.; Carella, E.; Bermudez Sanchez, S.; Orusa, R.; Martella, V.; Marsilio, F.; Di Martino, B. First Molecular Identification of Kobuviruses in Wolves (Canis Lupus) in Italy. Archives of Virology 2018, 163, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, G.; Egyed, L. Bovine Kobuvirus in Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 822–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, G.; Boros, Á.; Pankovics, P. Kobuviruses – a Comprehensive Review. Reviews in Medical Virology 2011, 21, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, B.; Di Profio, F.; Melegari, I.; Di Felice, E.; Robetto, S.; Guidetti, C.; Orusa, R.; Martella, V.; Marsilio, F. Molecular Detection of Kobuviruses in European Roe Deer (Capreolus Capreolus) in Italy. Arch Virol 2015, 160, 2083–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melegari, I.; Di Profio, F.; Sarchese, V.; Martella, V.; Marsilio, F.; Di Martino, B. First Molecular Evidence of Kobuviruses in Goats in Italy. Arch Virol 2016, 161, 3245–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bartolo, I.; Angeloni, G.; Tofani, S.; Monini, M.; Ruggeri, F.M. Infection of Farmed Pigs with Porcine Kobuviruses in Italy. Arch Virol 2015, 160, 1533–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, B.; Di Profio, F.; Di Felice, E.; Ceci, C.; Pistilli, M.G.; Marsilio, F. Molecular Detection of Bovine Kobuviruses in Italy. Arch Virol 2012, 157, 2393–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abi, K.; Zhang, Q.; Jing, Z.Z.; Tang, C. First Detection and Molecular Characteristics of Caprine Kobuvirus in Goats in China. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2020, 85, 104566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, T.; Ito, M.; Kabashima, Y.; Tsuzuki, H.; Fujiura, A.; Sakae, K. Isolation and Characterization of a New Species of Kobuvirus Associated with Cattle. Journal of General Virology 2003, 84, 3069–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Martino, B.; Di Felice, E.; Ceci, C.; Di Profio, F.; Marsilio, F. Canine Kobuviruses in Diarrhoeic Dogs in Italy. Veterinary Microbiology 2013, 166, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernike, K.; Wylezich, C.; Höper, D.; Schneider, J.; Lurz, P.W.W.; Meredith, A.; Milne, E.; Beer, M.; Ulrich, R.G. Widespread Occurrence of Squirrel Adenovirus 1 in Red and Grey Squirrels in Scotland Detected by a Novel Real-Time PCR Assay. Virus Research 2018, 257, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everest, D.J.; Shuttleworth, C.M.; Stidworthy, M.F.; Grierson, S.S.; Duff, J.P.; Kenward, R.E. Adenovirus: An Emerging Factor in Red Squirrel S Ciurus Vulgaris Conservation. Mammal Review 2014, 44, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Jiménez, D.; Graham, D.; Couper, D.; Benkö, M.; Schöniger, S.; Gurnell, J.; Sainsbury, A.W. EPIZOOTIOLOGY AND PATHOLOGIC FINDINGS ASSOCIATED WITH A NEWLY DESCRIBED ADENOVIRUS IN THE RED SQUIRREL, SCIURUS VULGARIS. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 2011, 47, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeo, C.; Ferrari, N.; Rossi, C.; Everest, D.J.; Grierson, S.S.; Lanfranchi, P.; Martinoli, A.; Saino, N.; Wauters, L.A.; Hauffe, H.C. Ljungan Virus and an Adenovirus in Italian Squirrel Populations. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 2014, 50, 409–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côrte-Real, J.V.; Lopes, A.M.; Rebelo, H.; Paulo Lopes, J.; Amorim, F.; Pita, R.; Correia, J.; Melo, P.; Beja, P.; José Esteves, P.; et al. Adenovirus Emergence in a Red Squirrel ( Sciurus Vulgaris ) in Iberian Peninsula. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020, 67, 2300–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everest, D.J.; Shuttleworth, C.M.; Grierson, S.S.; Dastjerdi, A.; Stidworthy, M.F.; Duff, J.P.; Higgins, R.J.; Mill, A.; Chantrey, J. The Implications of Significant Adenovirus Infection in UK Captive Red Squirrel (Sciurus Vulgaris) Collections: How Histological Screening Can Aid Applied Conservation Management. Mammalian Biology 2018, 88, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.; Gregory, W.F.; Turnbull, D.; Rocchi, M.; Meredith, A.L.; Philbey, A.W.; Sharp, C.P. Novel Adenoviruses Detected in British Mustelids, Including a Unique Aviadenovirus in the Tissues of Pine Martens (Martes Martes). Journal of Medical Microbiology 2017, 66, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, B.; Duchamp, C.; Möstl, K.; Diehl, P.A.; Betschart, B. Comparative Survey of Canine Parvovirus, Canine Distemper Virus and Canine Enteric Coronavirus Infection in Free-Ranging Wolves of Central Italy and South-Eastern France. European Journal of Wildlife Research 2014, 60, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, G.M.; Santos, N.; Grøndahl-Rosado, R.; Fonseca, F.P.; Tavares, L.; Neto, I.; Cartaxeiro, C.; Duarte, A. Unveiling Patterns of Viral Pathogen Infection in Free-Ranging Carnivores of Northern Portugal Using a Complementary Methodological Approach. Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 2020, 69, 101432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfano, F.; Dowgier, G.; Valentino, M.P.; Galiero, G.; Tinelli, A.; Decaro, N.; Fusco, G. Identification of Pantropic Canine Coronavirus in a Wolf (Canis Lupus Italicus) in Italy. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 2019, 55, 504–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, M.D.; Henriques, A.M.; Barros, S.C.; Fagulha, T.; Mendonça, P.; Carvalho, P.; Monteiro, M.; Fevereiro, M.; Basto, M.P.; Rosalino, L.M.; et al. Snapshot of Viral Infections in Wild Carnivores Reveals Ubiquity of Parvovirus and Susceptibility of Egyptian Mongoose to Feline Panleukopenia Virus. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, B.; Di Profio, F.; Melegari, I.; Robetto, S.; Di Felice, E.; Orusa, R.; Marsilio, F. Molecular Evidence of Kobuviruses in Free-Ranging Red Foxes (Vulpes Vulpes). Arch Virol 2014, 159, 1803–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, G.; Lu, C.; Wen, H. Detection of Canine Coronaviruses Genotype I and II in Raised Canidae Animals in China. Berliner und Munchener Tierarztliche Wochenschrift 2006, 119, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Calatayud, O.; Esperón, F.; Velarde, R.; Oleaga, Á.; Llaneza, L.; Ribas, A.; Negre, N.; de la Torre, A.; Rodríguez, A.; Millán, J. Genetic Characterization of Carnivore Parvoviruses in Spanish Wildlife Reveals Domestic Dog and Cat-Related Sequences. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases 2020, 67, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truyen, U.; Müller, T.; Heidrich, R.; Tackmann, K.; Carmichael, L.E. Survey on Viral Pathogens in Wild Red Foxes ( Vulpes Vulpes ) in Germany with Emphasis on Parvoviruses and Analysis of a DNA Sequence from a Red Fox Parvovirus. Epidemiol. Infect. 1998, 121, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amoroso, M.G.; Di Concilio, D.; D’Alessio, N.; Veneziano, V.; Galiero, G.; Fusco, G. Canine Parvovirus and Pseudorabies Virus Coinfection as a Cause of Death in a Wolf ( Canis Lupus ) from Southern Italy. Veterinary Medicine & Sci 2020, 6, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canuti, M.; Todd, M.; Monteiro, P.; Van Osch, K.; Weir, R.; Schwantje, H.; Britton, A.P.; Lang, A.S. Ecology and Infection Dynamics of Multi-Host Amdoparvoviral and Protoparvoviral Carnivore Pathogens. Pathogens 2020, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoelzer, K.; Parrish, C.R. The Emergence of Parvoviruses of Carnivores. Vet. Res. 2010, 41, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobrino, R.; Arnal, M.C.; Luco, D.F.; Gortázar, C. Prevalence of Antibodies against Canine Distemper Virus and Canine Parvovirus among Foxes and Wolves from Spain. Veterinary Microbiology 2008, 126, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N.; Desario, C.; Parisi, A.; Martella, V.; Lorusso, A.; Miccolupo, A.; Mari, V.; Colaianni, M.L.; Cavalli, A.; Di Trani, L.; et al. Genetic Analysis of Canine Parvovirus Type 2c. Virology 2009, 385, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N.; Desario, C.; Miccolupo, A.; Campolo, M.; Parisi, A.; Martella, V.; Amorisco, F.; Lucente, M.S.; Lavazza, A.; Buonavoglia, C. Genetic Analysis of Feline Panleukopenia Viruses from Cats with Gastroenteritis. Journal of General Virology 2008, 89, 2290–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackelton, L.A.; Parrish, C.R.; Truyen, U.; Holmes, E.C. High Rate of Viral Evolution Associated with the Emergence of Carnivore Parvovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005, 102, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lojkić, I.; Biđin, M.; Prpić, J.; Šimić, I.; Krešić, N.; Bedeković, T. Faecal Virome of Red Foxes from Peri-Urban Areas. Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 2016, 45, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battilani, M.; Scagliarini, A.; Tisato, E.; Turilli, C.; Jacoboni, I.; Casadio, R.; Prosperi, S. Analysis of Canine Parvovirus Sequences from Wolves and Dogs Isolated in Italy. Journal of General Virology 2001, 82, 1555–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berns, K.I.; Giraud, C. Biology of Adeno-Associated Virus. In Adeno-Associated Virus. In Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Vectors in Gene Therapy; Berns, K.I., Giraud, C., Eds.; Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1996; Vol. 218, pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-3-642-80209-6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F.; Sun, H.; Wang, Y. Porcine Bocavirus: Achievements in the Past Five Years. Viruses 2014, 6, 4946–4960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Fan, Z.; Jiang, L.; Lin, Y.; Fu, X.; Shen, Q.; Sun, Z.; Wang, X.; et al. A Novel Bocavirus from Domestic Mink, China. Virus Genes 2016, 52, 887–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manteufel, J.; Truyen, U. Animal Bocaviruses: A Brief Review. Intervirology 2008, 51, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, J.; Yi, S.; Wang, H.; Dong, G.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, Y.; Dong, H.; Wang, K.; Hu, G. Complete Genome Sequence Analysis of Canine Bocavirus 1 Identified for the First Time in Domestic Cats. Arch Virol 2019, 164, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfankuche, V.M.; Bodewes, R.; Hahn, K.; Puff, C.; Beineke, A.; Habierski, A.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Baumgärtner, W. Porcine Bocavirus Infection Associated with Encephalomyelitis in a Pig, Germany1. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22, 1310–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canuti, M.; Fry, K.; Cluff, H.D.; Mira, F.; Fenton, H.; Lang, A.S. Co-circulation of Five Species of Dog Parvoviruses and Canine Adenovirus Type 1 among Gray Wolves ( Canis Lupus ) in Northern Canada. Transbounding Emerging Dis 2022, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, B.; Masachessi, G.; Mladenova, Z. Animal Picobirnavirus. VirusDis. 2014, 25, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masachessi, G.; Martínez, L.C.; Giordano, M.O.; Barril, P.A.; Isa, B.M.; Ferreyra, L.; Villareal, D.; Carello, M.; Asis, C.; Nates, S.V. Picobirnavirus (PBV) Natural Hosts in Captivity and Virus Excretion Pattern in Infected Animals. Arch Virol 2007, 152, 989–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, L.C.; Masachessi, G.; Carruyo, G.; Ferreyra, L.J.; Barril, P.A.; Isa, M.B.; Giordano, M.O.; Ludert, J.E.; Nates, S.V. Picobirnavirus Causes Persistent Infection in Pigs. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2010, 10, 984–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits, S.L.; Poon, L.L.M.; Van Leeuwen, M.; Lau, P.-N.; Perera, H.K.K.; Peiris, J.S.M.; Simon, J.H.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E. Genogroup I and II Picobirnaviruses in Respiratory Tracts of Pigs. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 2328–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Kataoka, M.; Doan, Y.H.; Oi, T.; Furuya, T.; Oba, M.; Mizutani, T.; Oka, T.; Li, T.-C.; Nagai, M. Isolation and Characterization of Mammalian Orthoreovirus Type 3 from a Fecal Sample from a Wild Boar in Japan. Arch Virol 2021, 166, 1671–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, G.M.; McNeilly, F.; Kennedy, S.; Daft, B.; Ellis, J.A.; Haines, D.M.; Meehan, B.M.; Adair, B.M. Isolation of Porcine Circovirus-like Viruses from Pigs with a Wasting Disease in the USA and Europe. J VET Diagn Invest 1998, 10, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, L.; He, K.; Yu, Z.; Mao, A.; Ni, Y.; Zhang, X.; Guo, R.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; et al. Complete Genome Sequence of a Novel Porcine Circovirus-Like Agent. J Virol 2012, 86, 639–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, T.; Li, L.; Simmonds, P.; Wang, C.; Moeser, A.; Delwart, E. The Fecal Virome of Pigs on a High-Density Farm. J Virol 2011, 85, 11697–11708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacini, M.I.; Forzan, M.; Cilia, G.; Bertelloni, F.; Fratini, F.; Mazzei, M. Detection and Characterization of Viral Pathogens Associated with Reproductive Failure in Wild Boars in Central Italy. Animals 2021, 11, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, A.M.R.; Zlotowski, P.; Rozza, D.B.; Borba, M.R.; Leal, J.D.S.; Cruz, C.E.F.D.; Driemeier, D. Postweaning Multisystemic Wasting Syndrome in Farmed Wild Boars (Sus Scrofa) in Rio Grande Do Sul. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2006, 26, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Hou, C.; Wang, Z.; Meng, P.; Chen, H.; Cao, H. First Complete Genomic Sequence Analysis of Porcine Circovirus Type 4 (PCV4) in Wild Boars. Veterinary Microbiology 2022, 273, 109547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzo, G.; Tucciarone, C.M.; Drigo, M.; Cecchinato, M.; Martini, M.; Mondin, A.; Menandro, M.L. First Report of Wild Boar Susceptibility to Porcine Circovirus Type 3: High Prevalence in the Colli Euganei Regional Park (Italy) in the Absence of Clinical Signs. Transbound Emerg Dis 2018, 65, 957–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, J.; Segalés, J.; Höfle, U.; Balasch, M.; Plana-Durán, J.; Domingo, M.; Gortázar, C. Epidemiological Study on Porcine Circovirus Type 2 (PCV2) Infection in the European Wild Boar ( Sus Scrofa ). Vet. Res. 2004, 35, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cságola, A.; Kecskeméti, S.; Kardos, G.; Kiss, I.; Tuboly, T. Genetic Characterization of Type 2 Porcine Circoviruses Detected in Hungarian Wild Boars. Arch Virol 2006, 151, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Lu, L.; Du, J.; Yang, L.; Ren, X.; Liu, B.; Jiang, J.; Yang, J.; Dong, J.; Sun, L.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Rodent and Small Mammal Viromes to Better Understand the Wildlife Origin of Emerging Infectious Diseases. Microbiome 2018, 6, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarošová, V.; Hrazdilová, K.; Filipejová, Z.; Schánilec, P.; Celer, V. Whole Genome Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis of Feline Anelloviruses. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2015, 32, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraberger, S.; Serieys, L.Ek.; Richet, C.; Fountain-Jones, N.M.; Baele, G.; Bishop, J.M.; Nehring, M.; Ivan, J.S.; Newkirk, E.S.; Squires, J.R.; et al. Complex Evolutionary History of Felid Anelloviruses. Virology 2021, 562, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacini, M.I.; Mazzei, M.; Sgorbini, M.; D’Alfonso, R.; Papini, R.A. A One-Year Retrospective Analysis of Viral and Parasitological Agents in Wildlife Animals Admitted to a First Aid Hospital. Animals 2023, 13, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsson, O.E.; Belák, S.; Granberg, F. The Effect of Preprocessing by Sequence-Independent, Single-Primer Amplification (SISPA) on Metagenomic Detection of Viruses. Biosecurity and Bioterrorism: Biodefense Strategy, Practice, and Science 2013, 11, S227–S234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melegari, I.; Sarchese, V.; Di Profio, F.; Robetto, S.; Carella, E.; Bermudez Sanchez, S.; Orusa, R.; Martella, V.; Marsilio, F.; Di Martino, B. First Molecular Identification of Kobuviruses in Wolves (Canis Lupus) in Italy. Arch Virol 2018, 163, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsunemitsu, H.; el-Kanawati, Z.R.; Smith, D.R.; Reed, H.H.; Saif, L.J. Isolation of Coronaviruses Antigenically Indistinguishable from Bovine Coronavirus from Wild Ruminants with Diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol 1995, 33, 3264–3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olde Riekerink, R.G.M.; Dominici, A.; Barkema, H.W.; De Smit, A.J. Seroprevalence of Pestivirus in Four Species of Alpine Wild Ungulates in the High Valley of Susa, Italy. Veterinary Microbiology 2005, 108, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palombieri, A.; Fruci, P.; Di Profio, F.; Sarchese, V.; Robetto, S.; Martella, V.; Di Martino, B. Detection and Characterization of Bopiviruses in Domestic and Wild Ruminants. Transbounding Emerging Dis 2022, 69, 3972–3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, L.W.; Hanley, R.S.; Chiu, P.H.; Lehmkuhl, H.D.; Nordhausen, R.W.; Stillian, M.H.; Swift, P.K. Lesions and Transmission of Experimental Adenovirus Hemorrhagic Disease in Black-Tailed Deer Fawns. Vet Pathol 1999, 36, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridpath, J.F.; Neill, J.D.; Palmer, M.V.; Bauermann, F.V.; Falkenberg, S.M.; Wolff, P.L. Isolation and Characterization of a Novel Cervid Adenovirus from White-Tailed Deer ( Odocoileus Virginianus ) Fawns in a Captive Herd. Virus Research 2017, 238, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastjerdi, A.; Jeckel, S.; Davies, H.; Irving, J.; Longue, C.; Plummer, C.; Vidovszky, M.Z.; Harrach, B.; Chantrey, J.; Martineau, H.; et al. Novel Adenovirus Associated with Necrotizing Bronchiolitis in a Captive Reindeer ( Rangifer Tarandus). Transbounding Emerging Dis 2022, 69, 3097–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Wang, H.; Yang, S.; Shen, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhou, T.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, W. Identification and Characterization of a Novel Bocaparvovirus in Tufted Deer (Elaphodus Cephalophus) in China. Arch Virol 2022, 167, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casaubon, J.; Vogt, H.-R.; Stalder, H.; Hug, C.; Ryser-Degiorgis, M.-P. Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus in Free-Ranging Wild Ruminants in Switzerland: Low Prevalence of Infection despite Regular Interactions with Domestic Livestock. BMC Vet Res 2012, 8, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiana, L.A.; Lanave, G.; Desario, C.; Berjaoui, S.; Alfano, F.; Puglia, I.; Fusco, G.; Colaianni, M.L.; Vincifori, G.; Camarda, A.; et al. Circulation of Diverse Protoparvoviruses in Wild Carnivores, Italy. Transbound Emerg Dis 2021, 68, 2489–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conceição-Neto, N.; Godinho, R.; Álvares, F.; Yinda, C.K.; Deboutte, W.; Zeller, M.; Laenen, L.; Heylen, E.; Roque, S.; Petrucci-Fonseca, F.; et al. Viral Gut Metagenomics of Sympatric Wild and Domestic Canids, and Monitoring of Viruses: Insights from an Endangered Wolf Population. Ecology and Evolution 2017, 7, 4135–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olarte-Castillo, X.A.; Heeger, F.; Mazzoni, C.J.; Greenwood, A.D.; Fyumagwa, R.; Moehlman, P.D.; Hofer, H.; East, M.L. Molecular Characterization of Canine Kobuvirus in Wild Carnivores and the Domestic Dog in Africa. Virology 2015, 477, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balboni, A.; Verin, R.; Morandi, F.; Poli, A.; Prosperi, S.; Battilani, M. Molecular Epidemiology of Canine Adenovirus Type 1 and Type 2 in Free-Ranging Red Foxes (Vulpes Vulpes) in Italy. Veterinary Microbiology 2013, 162, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calatayud, O.; Esperón, F.; Velarde, R.; Oleaga, Á.; Llaneza, L.; Ribas, A.; Negre, N.; Torre, A.; Rodríguez, A.; Millán, J. Genetic Characterization of Carnivore Parvoviruses in Spanish Wildlife Reveals Domestic Dog and Cat-related Sequences. Transbound Emerg Dis 2020, 67, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, G.M.; Santos, N.; Grøndahl-Rosado, R.; Fonseca, F.P.; Tavares, L.; Neto, I.; Cartaxeiro, C.; Duarte, A. Unveiling Patterns of Viral Pathogen Infection in Free-Ranging Carnivores of Northern Portugal Using a Complementary Methodological Approach. Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 2020, 69, 101432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.; Abbondati, E.; Cox, A.L.; Mitchell, G.B.B.; Pizzi, R.; Sharp, C.P.; Philbey, A.W. Infectious Canine Hepatitis in Red Foxes ( Vulpes Vulpes ) in Wildlife Rescue Centres in the UK. Veterinary Record 2016, 178, 421–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verin, R.; Forzan, M.; Schulze, C.; Rocchigiani, G.; Balboni, A.; Poli, A.; Mazzei, M. Multicentric Molecular and Pathologic Study on Canine Adenovirus Type 1 in Red Foxes (Vulpes Vulpes) in Three European Countries. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 2019, 55, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åkerstedt, J.; Lillehaug, A.; Larsen, I.-L.; Eide, N.E.; Arnemo, J.M.; Handeland, K. SEROSURVEY FOR CANINE DISTEMPER VIRUS, CANINE ADENOVIRUS, LEPTOSPIRA INTERROGANS, AND TOXOPLASMA GONDII IN FREE-RANGING CANIDS IN SCANDINAVIA AND SVALBARD. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 2010, 46, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, G.; Stout, A. Coronaviruses in Wild Canids: A Review of the Literature 2022.

- Molnar, B.; Duchamp, C.; Möstl, K.; Diehl, P.-A.; Betschart, B. Comparative Survey of Canine Parvovirus, Canine Distemper Virus and Canine Enteric Coronavirus Infection in Free-Ranging Wolves of Central Italy and South-Eastern France. Eur J Wildl Res 2014, 60, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán, J.; López-Bao, J.V.; García, E.J.; Oleaga, Á.; Llaneza, L.; Palacios, V.; De La Torre, A.; Rodríguez, A.; Dubovi, E.J.; Esperón, F. Patterns of Exposure of Iberian Wolves (Canis Lupus) to Canine Viruses in Human-Dominated Landscapes. EcoHealth 2016, 13, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Brand, J.M.A.; Van Leeuwen, M.; Schapendonk, C.M.; Simon, J.H.; Haagmans, B.L.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Smits, S.L. Metagenomic Analysis of the Viral Flora of Pine Marten and European Badger Feces. J Virol 2012, 86, 2360–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, S.L.; Raj, V.S.; Oduber, M.D.; Schapendonk, C.M.E.; Bodewes, R.; Provacia, L.; Stittelaar, K.J.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Haagmans, B.L. Metagenomic Analysis of the Ferret Fecal Viral Flora. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stout, A.E.; Guo, Q.; Millet, J.K.; De Matos, R.; Whittaker, G.R. Coronaviruses Associated with the Superfamily Musteloidea. mBio 2021, 12, e02873–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourque, L.; Nielsen, O.; Jager, M.; Ojkic, D.; Provost, C.; Gagnon, C.A.; Lockerbie, B.; Snyman, H.; Stevens, B.; Needle, D.; et al. IN SITU HYBRIDIZATION AND VIRUS CHARACTERIZATION OF SKUNK ADENOVIRUS IN NORTH AMERICAN WILDLIFE REVEALS MULTISYSTEMIC INFECTIONS IN A BROAD RANGE OF HOSTS. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 2022, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sabatino, D.; Di Francesco, G.; Zaccaria, G.; Malatesta, D.; Brugnola, L.; Marcacci, M.; Portanti, O.; De Massis, F.; Savini, G.; Teodori, L.; et al. Lethal Distemper in Badgers ( Meles Meles ) Following Epidemic in Dogs and Wolves. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2016, 46, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, J.M.; Ullman, K.; Struve, T.; Agger, J.F.; Hammer, A.S.; Leijon, M.; Jensen, H.E. Investigation of the Viral and Bacterial Microbiota in Intestinal Samples from Mink (Neovison Vison) with Pre-Weaning Diarrhea Syndrome Using next Generation Sequencing. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.H.; Burek Huntington, K.; Miller, M. Mustelids. In Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals; Elsevier, 2018; pp. 287–304. ISBN 978-0-12-805306-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lempp, C.; Jungwirth, N.; Grilo, M.L.; Reckendorf, A.; Ulrich, A.; Van Neer, A.; Bodewes, R.; Pfankuche, V.M.; Bauer, C.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; et al. Pathological Findings in the Red Fox (Vulpes Vulpes), Stone Marten (Martes Foina) and Raccoon Dog (Nyctereutes Procyonoides), with Special Emphasis on Infectious and Zoonotic Agents in Northern Germany. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.; Gregory, W.F.; Turnbull, D.; Rocchi, M.; Meredith, A.L.; Philbey, A.W.; Sharp, C.P. Novel Adenoviruses Detected in British Mustelids, Including a Unique Aviadenovirus in the Tissues of Pine Martens (Martes Martes). Journal of Medical Microbiology 2017, 66, 1177–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N.Y.; Lee, M.C.; Kurkure, N.V.; Cho, H.S. Canine Adenovirus Type 1 Infection of a Eurasian River Otter ( Lutra Lutra ). Vet Pathol 2007, 44, 536–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; He, W.; Fu, J.; Li, Y.; He, H.; Chen, Q. Epidemiological Evidence for Fecal-Oral Transmission of Murine Kobuvirus. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 865605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wernike, K.; Wylezich, C.; Höper, D.; Schneider, J.; Lurz, P.W.W.; Meredith, A.; Milne, E.; Beer, M.; Ulrich, R.G. Widespread Occurrence of Squirrel Adenovirus 1 in Red and Grey Squirrels in Scotland Detected by a Novel Real-Time PCR Assay. Virus Research 2018, 257, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balik, S.; Bunting, E.; Dubovi, E.; Renshaw, R.; Childs-Sanford, S. DETECTION OF SKUNK ADENOVIRUS 1 IN TWO NORTH AMERICAN PORCUPINES (ERETHIZON DORSATUM) WITH RESPIRATORY DISEASE. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 2020, 50, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, W.-T.; Hou, X.; Zhao, J.; Sun, J.; He, H.; Si, W.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Z.; Yan, Z.; Xing, G.; et al. Virome Characterization of Game Animals in China Reveals a Spectrum of Emerging Pathogens. Cell 2022, 185, 1117–1129.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 5’-3’PRIMER FORWARD | 5’-3’ PRIMER REVERSE | REFERENCE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adenovirus spp* | 1° round: TNMGNGGNGGNMGNTGYTAYCC 2° round: GTDGCRAANSHNCCRTABARNGMRT |

1° round: GTDGCRAANSHNCCRTABARNGMRTT 2° round: CCANCCBCDRTTRTGNARNGTRA |

[22] |

| CAdV 1,2 | CGCGCTGAACATTACTACCTTGTC | CCTAGAGCACTTCGTGTCCGCTT | [23] |

| CPV | ACAAGATAAAAGACGTGGTGTAACTCAA | CAACCTCAGCTGGTCTCATAATAGT | [24] |

| FPV/CPV | ACAAGATAAAAGACGTGGTGTAACTCAA | CAACCTCAGCTGGTCTCATAATAGT | [25] |

| Bocavirus spp* | GCCAGCACNGGNAARACMAA | CATNAGNCAYTCYTCCCACCA | [26] |

| CBov 1 | 1° round: CARTGGTAYGCTCCMATYTTTAA 2° round: TGGTAYGCTCCMATYTTTAAYGG |

1° round: TGGCTCCCGTCACAAAAKATRTG 2° round: GCTCCCGTCACAAAAKATRTGAAC |

[27] |

| CBoV 2 | AGGTCGGCCACTGGCTGT | CAGCTTAACGGCATTCACTA | [26] |

| CBoV 3 | 1° round: CAGATTTGGGGGTCCTGCAT 2° round: ATGCCGTCACCAATCCACAT |

1° round: GCACTGTCTGCGCTGAAAAA 2° round: AGCTTGTGGTGGACAGTAGC |

[28] |

| LBoV | AGACCAGATGCTCCACATGG | TGCCTGCCACGGATTGTACC | [29] |

| Canine CV | CTGAAAGATAAAGGCCTCTCGCT | AGGGGGGTGAACAGGTAAACG | [30] |

| TTV1 | CGGGTTCAGGAGGCTCAAT | GCCATTCGGAACTGCACTTACT | [31] |

| TTV2 | TCATGACAGGGTTCACCGGA | CGTCTGCGCACTTACTTATATACTCTA | [31] |

| Kobuvirus spp* | TGGAYTACAAGTGTTTTGATGC | ATGTTGTTRATGATGGTGTTGA | [32] |

| Astrovirus spp* | 1° round a: GARTTYGATTGGRCKCGKTAYGA 1° round b: GARTTYGATTGGRCKAGGTAYGA 2° round a: CGKTAYGATGGKACKATHCC 2° round b: AGGTAYGATGGKACKATHCC |

GGYTTKACCCACATNCCRAA | [33] |

| Coronavirus spp.* | 1° round: GGKTGGGAYTAYCCKAARTG *--2° round: GGTTGGGACTATCCTAAGTGTGA |

1° round: TGYTGTSWRCARAAYTCRTG 2° round: CCATCATCAGATAGAATCATCAT |

[34] |

| BVDV | ATGCCCWTAGTAGGACTAGCA | TCAACTCCATGTGCCATGTAC | [35] |

| Bopivirus spp* | CTGRGCAAGTTCACCAACAA | GTCCATGACAGGGTGAATCA | [36] |

| CDV | ACTTCCGCGATCTCCACTGG | GCTCCACTGCATCTGTATGG | [29] |

| Virus | Host | Genbank | Reference sequence |

Per. Ident | E value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPV | Red Fox | CPV/fox/169/IT OQ079554 |

Canine parvovirus 2c MF177262.1 |

84,83% | 6e-31 |

| CCoV | Red Fox | CCoV/fox/208/IT OQ079555 |

Canine coronavirus ON834692.1 |

100.00% | 0.0 |

| AdV | Small mustelids |

RAdV/mustelidae/878/IT OQ079556 |

Rodent adenovirus KY369960.1 |

75.91% | 1e-49 |

| Small mustelids |

RAdV/mustelidae/888/IT OQ079557 |

Rodent adenovirus KY369960.1 |

74.74% | 1e-42 | |

| AstV | Red Fox | Mastv/fox/46/IT OQ079558 |

Bovine astrovirus MW373720.1 |

90.82% | 7e-155 |

| Porcupine | Mastv/porcupine/484/IT OQ079559 |

Mamastrovirus 3 MH399894.1 |

91,27% | 2e-156 | |

| Cervo | Mastv/reddeer/707/IT OQ079560 |

Murine astrovirus JQ408746.1 |

88.49% | 9e-128 | |

| Small mustelids |

Mastv/mustelidae/883/IT OQ079561 |

Murine astrovirus JQ408746.1 |

87.95% | 3e-81 | |

| Red Deer | Mastv/redeer/885/IT OQ079562 |

Murine astrovirus JQ408746.1 |

88.56% | 7e-129 | |

| Wolf | CAsV/wolf/481/IT OQ079564 |

Canine astrovirus OQ198039 |

88.80% | 3e-133 | |

| BoV | Red Fox | BoV/fox/171/IT OQ079563 |

Bocaparvovirus carnivoran5 PP592987 |

88.55% | 3-e83 |

| KoV | Wolf | Kov/wolf/525/IT OQ079565 |

Porcine kobuvirus MH184668.1 |

93.30% | 8e-88 |

| Red Fox | Kov/fox/88/IT OQ079566 |

Fox kobuvirus KF781172.1 |

92.49% | 5e-63 |

| Pool Number | N° of sequences |

Classified sequences * (%) |

Unclassified sequences * (%) |

Bacteria sequences * (%) |

Viral sequences * (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.86 x 107 | 21 | 79 | 76 | 2 |

| 2 | 1.79 x 107 | 29 | 72 | 92 | 1 |

| 3 | 2.17 x 107 | 26 | 74 | 89 | 0.7 |

| 4 | 2.18 x 107 | 59 | 41 | 98 | 0.4 |

| Pool number | Genbank | Ref- Seq | n° Reads | n° nucleotide |

Pairwise Identity | e Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PX314117 |

Porcine picobirnavirus MW978536.1 |

213 | 467 | 100% | 0.0 |

| PX314118 |

Rodent circovirus KY370041.1 |

7 | 480 | 89.97% | 1e-145 | |

| PX314119 |

Anelloviridae sp. MF346362.1 |

2 | 427 | 99,77% | 0.0 | |

| 2 | PX314120 |

Fox adeno-associated virus KC878874 |

28 | 1288 | 100% | 0.0 |

| PX314121 PX314122 PX314123 |

Red squirrel adenovirus -1 NC_035207 |

27 | 2129 | 69.66% 88.58% 100 |

1e-24 1e-1770 |

|

| PX314124 |

Pigeon adenovirus NC024474 |

17 | 319 | 100% | 2e-104 | |

| PX314125 PX314126 PX314127 |

Torqueteno felis virus MT538010 |

25 | 779 | 92.21% 98.06% 70.71% |

4e-51 7e-67 2e-30 |

|

| 3 | PX314128 PX314129 |

Porcine circo-like virus JF713717 |

31 | 1759 | 90.90% 98.15% |

0.0 0.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).