1. Introduction

Camelpox is an infectious viral disease that is widespread among camel populations. It is endemic in the Middle East (Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Yemen), Asia (India, Afghanistan, Pakistan), Africa (Algeria, Egypt, Kenya, Mauritania, Niger, Somalia, Morocco, Ethiopia, Oman, Sudan), and in the southern regions of the former USSR. The causative agent is the camelpox virus (CMLV), a member of the genus

Orthopoxvirus within the family

Poxviridae [

1].

Camelpox is characterized by fever and localized or generalized lesions of the skin and mucous membranes, including those of the oral cavity, as well as the respiratory and digestive tracts. Transmission occurs through direct contact with infected animals, either via skin abrasions or aerosolized particles. Infectious materials such as scabs, saliva, and secretion from infected camels can contaminate the environment, including water sources, which may act as temporary reservoirs of infection. Severe outbreaks in young and previously unexposed camels are often associated with high mortality rates [

2,

3]. Studies indicate that the frequency and severity of outbreaks increase during the rainy season, whereas milder cases are predominantly observed during the dry season. Both morbidity and mortality rates are higher in male camels than in females. In adult camels, mortality ranges from 10% to 28%, while in young animals it may reach 25-100%. Variations in the severity of clinical manifestations are thought to be related to differences among circulating CMLV strains [

2,

3,

4]. Additionally, camelpox has been described as a potential zoonosis, with three confirmed cases of human infection reported in India [

5,

6,

7].

Phylogenetic analysis has shown that among viruses of the genus

Orthopoxvirus, the CMLV is most closely related to the variola virus, the causative agent of smallpox, although both viruses infect a strictly limited range of hosts. Comparative analysis of the nucleotide sequences of the CMLV genome confirmed this close relationship, revealing a nucleotide identity of 96.6-98.6% between CMLV and Variola virus. Furthermore, a DNA distance matrix indicated a lower genetic distance between CMLV and Variola virus compared to that between CMLV and the vaccinia virus [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. The global and regional prevalence of camelpox, including in Kazakhstan, has been assessed using data from the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE). Between 2017 and 2021, ten outbreaks of camelpox were reported worldwide, occurring in India, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, several African countries, Russia. Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan [

13]. According to veterinary records from the Republic of Kazakhstan, sporadic cases of camelpox were recorded in the Mangistau and Atyrau regions in 1930, 1942-1943, 1965-1969, 1996 and 2019-2020. Statistical analysis of these data suggests a cyclical pattern of disease occurrence, with an interval of approximately 10 to 20 years [

14,

15].

Given the above, the question of camelpox virus localization during inter-epidemic periods remains highly relevant. Identifying its natural reservoir is crucial for preventing potential outbreaks and enabling the timely implementation of preventive measures.

This work represents a continuation of previously initiated study aimed at identifying the natural reservoirs of the camelpox virus. The study involved the analysis of samples collected from camels, rodents and hematophagous insects in Western Kazakhstan. Despite the absence of pronounced clinical signs, camels tested positive during the investigation. According to the literature, camelpox may occur in latent or subclinical forms, particularly among adult animals in endemic regions [

16,

17].

The collected samples were subjected to further molecular genetic analysis, including detection of viral DNA and whole-genome sequencing. Based on the obtained nucleotide sequences, phylogenetic analysis was carried out to determine the genetic relationships between the isolated strains and other known CMLV strains, and to propose potential routes of virus circulation in natural foci.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inoculation of Positive Samples into the Chorioallantoic Membrane of Chicken Embryos

Whole blood samples were initially centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes. The resulting supernatant was used to inoculate 10-day-old specific pathogen-free (SPF) chicken embryos. Inoculation was carried out under sterile conditions by administering 0.2 mL of the sample into the chorioallantoic membrane (CAM). The inoculated embryos were incubated at 37°C with a relative humidity of 60-70% for 5-7 days. Embryo viability was monitored daily.

Embryos that died within the first 24 hours post-inoculation were excluded from further analysis. Following the incubation period, the embryos were chilled at 4 °C for 24 hours. Subsequently, the eggs were opened, and the CAMs were examined for pathomorphological changes indicative of viral infection, including the presence of specific pock-like lesions.

2.2. Inoculation of the Isolated Virus into Cell Cultures

Cell cultures were infected with viral material previously isolated from the chorioallantoic membrane of chicken embryos. The material was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes, and the resulting supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm pore-size membrane filter. Subsequently, 0.2 mL of the virus-containing filtrate was inoculated onto confluent monolayers of lamb kidney and Vero cell lines.

Virus adsorption was carried out at 37°C for 60 minutes. After absorption, the inoculum was removed, the cell monolayers were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fresh growth medium was added. The infected cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 5-7 days. The cultures were monitored daily for the development of a cytopathic effect. Serial passaging was performed when necessary. Viral identification was conducted using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with primers specific for camelpox virus.

2.3. Spatial Analysis and Mapping

Spatial analysis, map construction and the application of cartographic symbols and design elements were performed using Esri ArcGIS Pro software, version 2.2. The software tools were employed to visualize sampling locations and to spatially interpret the obtained results.

2.4. Isolation of Viral DNA

Viral material obtained from infected cell cultures was first clarified by centrifugation at 2000 × g for 10 minutes to remove cellular debris. The resulting supernatant was then concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 200.000 × g for 20 minutes at 4 °C. A 200 μL aliquot of the concentrated viral suspension was used for DNA extraction using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of the extracted DNA was measured using the QubitTM DNA High Sensitivity (HS) Assay Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) on a QubitTM 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.5. Preparation of DNA Libraries for Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

For library preparation, 20 μL of viral DNA at a concentration of 100 ng/μL were used. DNA fragmentation was performed using the Ion ShearTM Plus Kit (Life Technologies, USA), followed by adapter ligation with the Ion Plus Fragment Library Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Purification steps were carried out using Agencourt AMPure XP magnetic beads (Beckman Coulter, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The resulting DNA fragments were separated by horizontal electrophoresis in a 1.5 % agarose gel (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) stained with SYBRTM Safe DNA fragments ranging from 350 to 500 base pairs were excised from the gel, visualized, and documented using the iBright TM CL1500 Imagine System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford USA). Gene Ruler TM 1 kb Plus DNA Ladder (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was used as a molecular weight marker. Gel-purified DNA fragments were extracted using the innuPREP DOUBLEpure Kit (Analytik Jena AG, Germany).

DNA libraries were amplified using components of the Ion Plus Fragment Library Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of the amplified libraries was quantified using the Ion Universal Library Quantitation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Final preparation of the libraries was carried out on the Ion Chef TM System using the Ion 510 TM, and 530TM Kit together with the Ion 530TM Chip (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

2.6. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) and Data Analysis

Whole-genome sequencing of the camelpox virus was performed using the Ion Torrent platform on the Ion GeneStudio™ S5 System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The raw sequencing data were processed using Ion Torrent Suite Software (v5.12) and exported in UBAM and FASTQ file formats. Genome assembly was carried out in the UGENE software environment (v52.1), using the genome of Camelpox virus strain 0408151v (GenBank accession no. KP768318.1) as a reference. FASTQ files served as the input data for downstream analysis. Read quality assessment was conducted using FastQC. Genome assembly was performed with the BWA-MEM algorithm. Annotation of the assembled genome was performed using the Prokka annotation pipeline (Galaxy version 1.14.6+galaxy1), which is primarily designed for prokaryotic genome annotation.

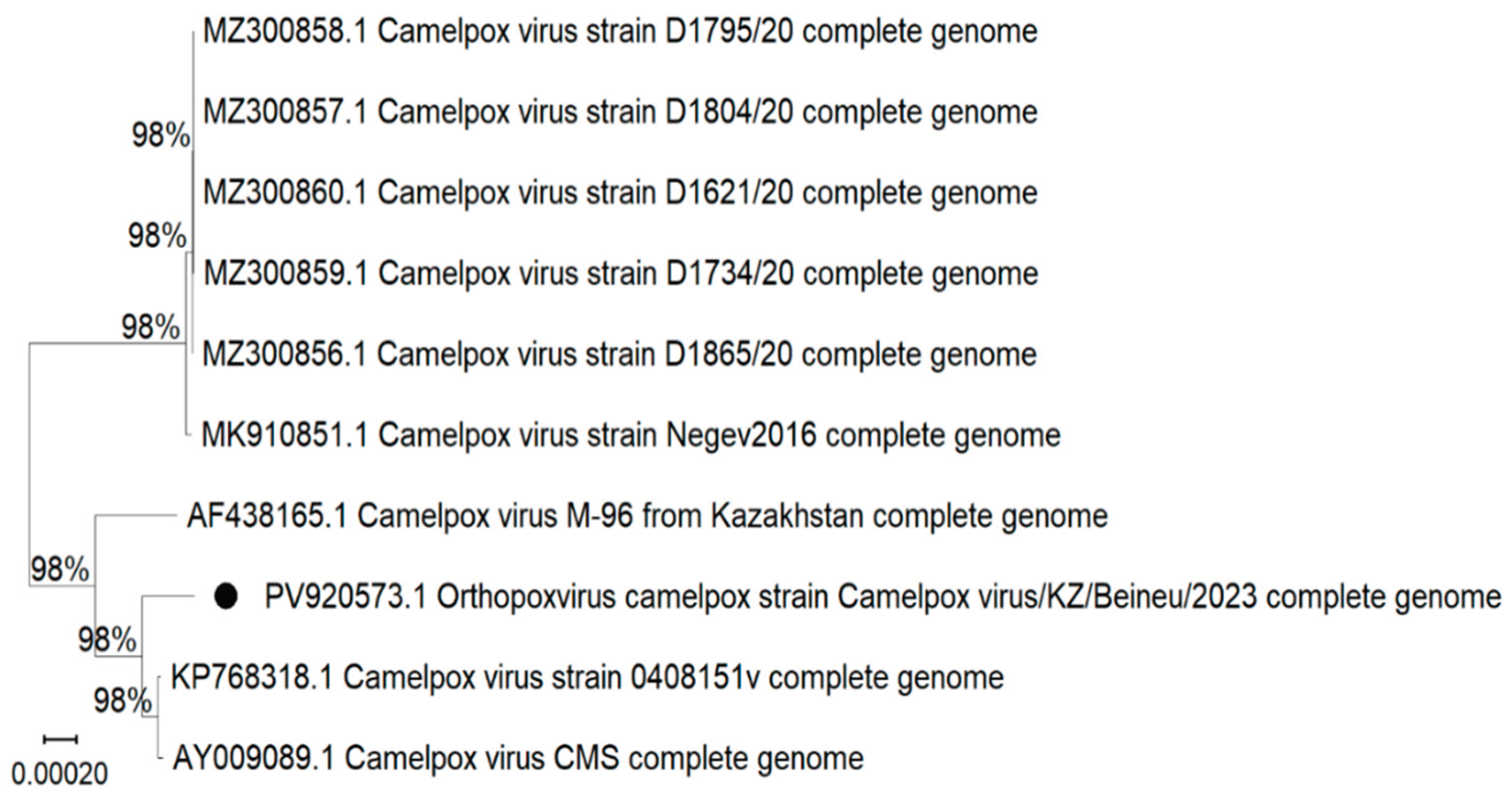

2.7. Phylogenetic Analysis

Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis were performed using MEGA software version 12. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method based on the Tamura-Nei substitution model. The robustness of the phylogenetic tree was evaluated by bootstrap analysis with 500 replicates.

3. Results

3.1. Positive Samples

According to previous studies, positive PCR results for the presence of camelpox virus were obtained exclusively from samples collected from camels. No viral genetic material was detected in samples collected from rodents and hematophagous insects. Based on the positive findings, a distribution map of CMLV in the Mangystau and Atyrau regions was generated. Although the concentration of viral material in individual samples may have been low, all PCR-positive cases were included in the spatial analysis due to their potential epizootic significance and the associated risk of virus circulation in these areas. Geographic mapping of CMLV-positive cases enables the identification of high-risk zones, facilitates monitoring of virus circulation dynamics, and supports the development of targeted strategies for epizootic surveillance and biosafety planning.

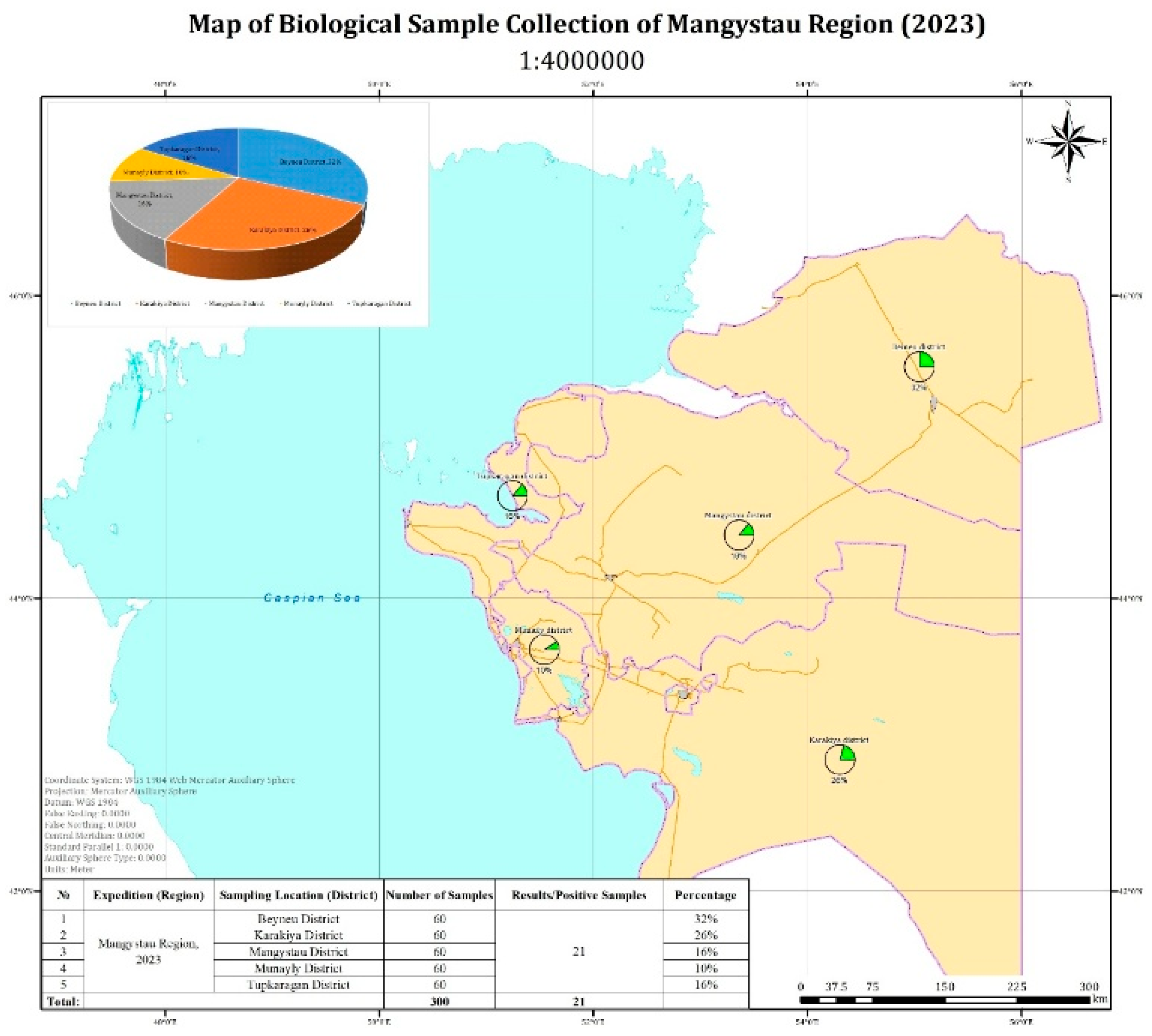

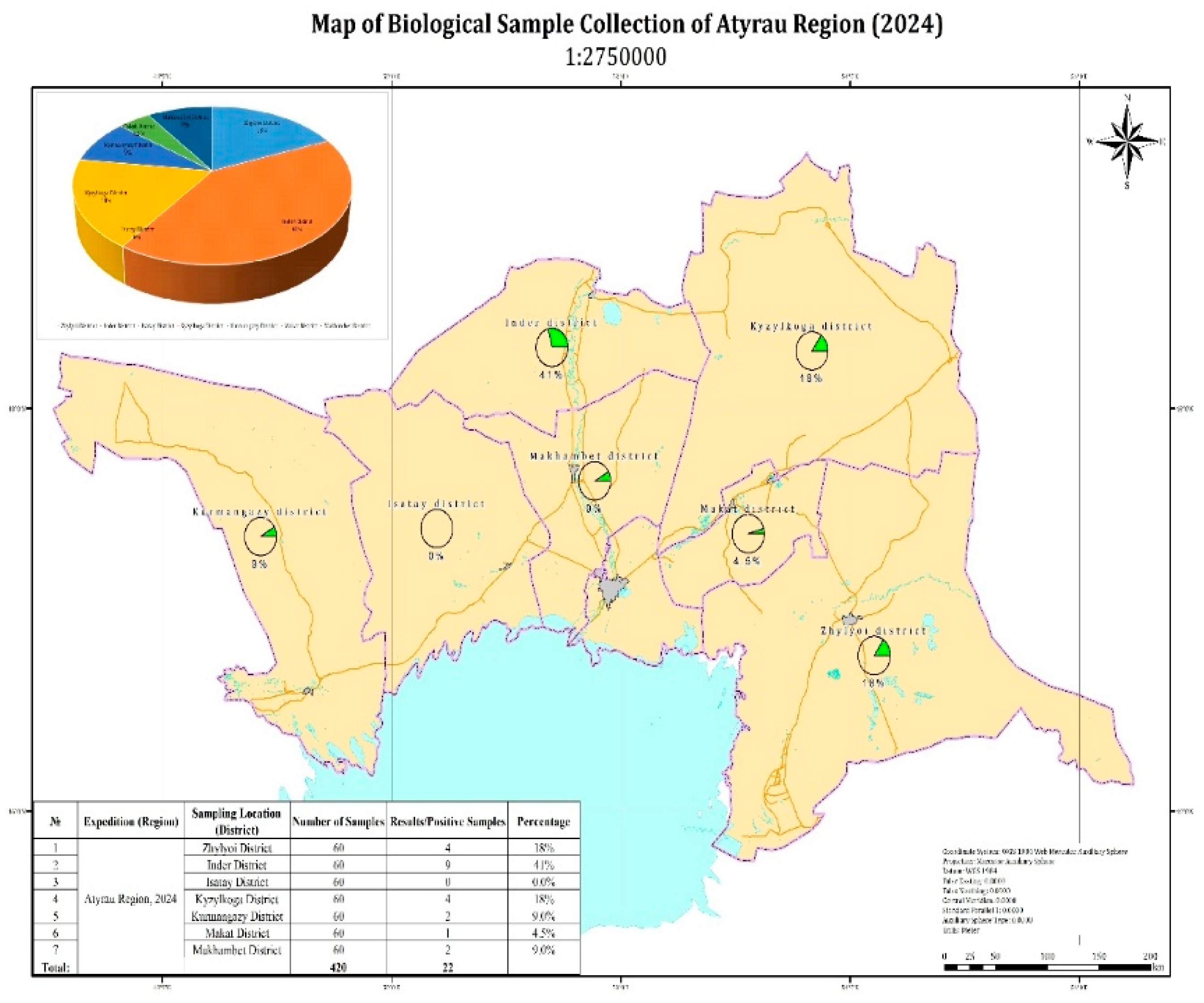

In the Mangystau region, 21 out of 300 examined camel blood samples tested positive by PCR (

Figure 1). The map illustrates the proportion of positive samples by administrative district.

In the Atyrau region, 22 out of 420 tested camel blood samples yielded positive PCR results. The highest proportions of positive samples were recorded in Beineu (32%) and Inder (41%) districts. Lower proportions were observed in Kurmangazy (9%), Makat (4.5%), and Makhambet (9%) districts. No positive samples were detected in the Isatay district (

Figure 2). It should be noted that the reported percentage values are calculated relative to the total number of positive samples, rather than the total number of samples tested, due to the relatively low number of PCR-positive cases. This approach allows for a clearer representation of the geographic distribution of virus detections. The aggregated pie chart in the upper left corner of the figure illustrates the overall distribution of positive samples by district.

3.2. Virus Isolation

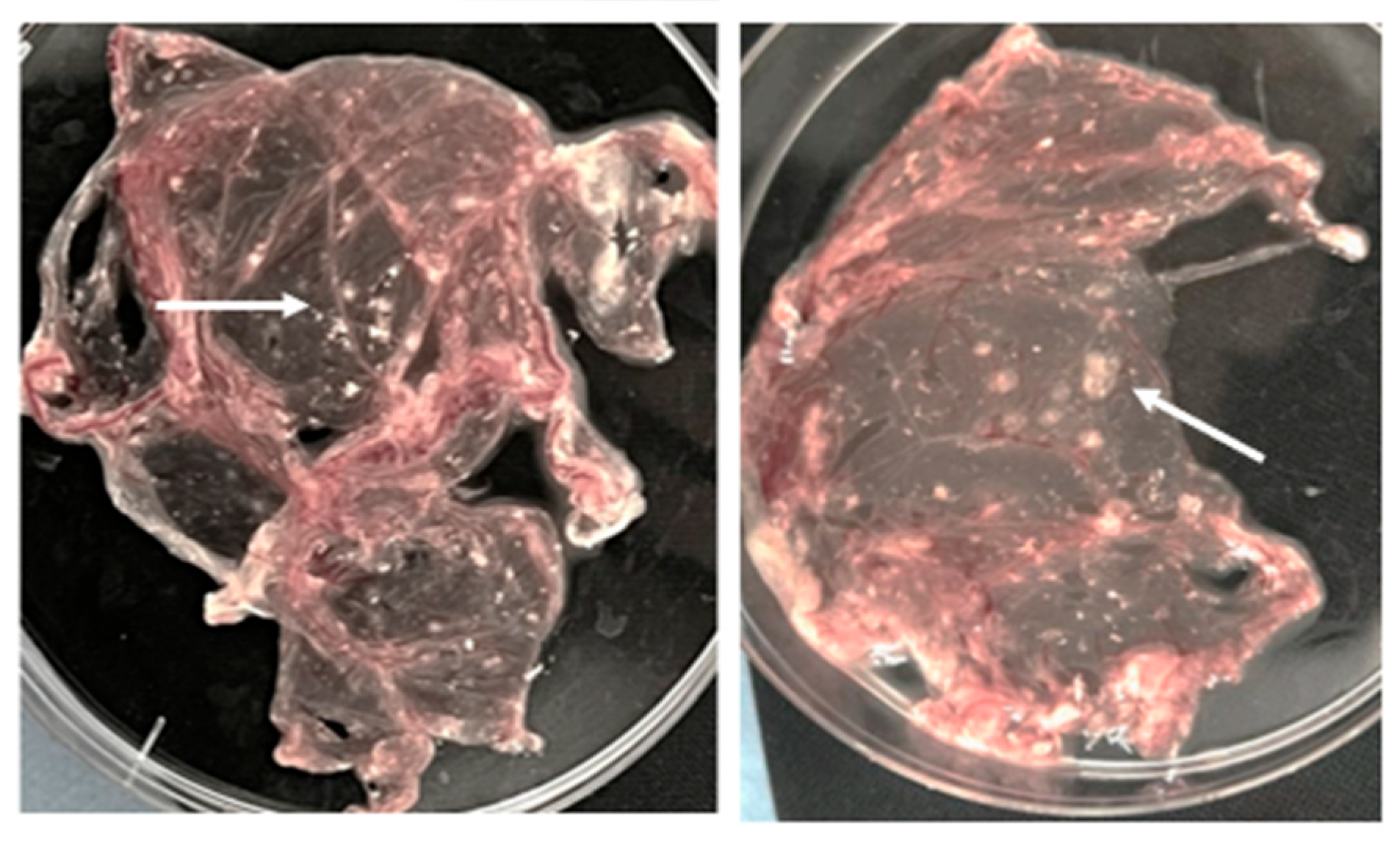

As previously noted, several PCR-positive samples were identified during monitoring. However, successful virus isolation was achieved from only a single sample-blood collected from a young camel during the 2023 expedition in the Beineu district of the Mangystau region. The inability to isolate the virus from the remaining PCR-positive samples is likely attributable to an insufficient concentration of viable virions capable of initiating replication in cell cultures.

It should be noted that the PCR method detects fragments of viral nucleic acids even at low viral titers, including non-infectious, defective, or degraded particles that are incapable of initiating an infectious process. The positive sample was inoculated into the chorioallontoic membrane (CAM) of 11-day-old chicken embryos. Signs of viral replication in the CAM were observed starting from the third passage, manifested as elevated, whitish lesions – either pinpoint or confluent – clearly demarcated from surrounding tissue and featuring characteristic central hemorrhagic inclusions (

Figure 3).

Initial virus isolation was performed in the chorioallontoic membrane of chicken embryos, after which the harvested viral material was used to infect susceptible cell cultures to facilitate virus adaptation and replication in vitro.

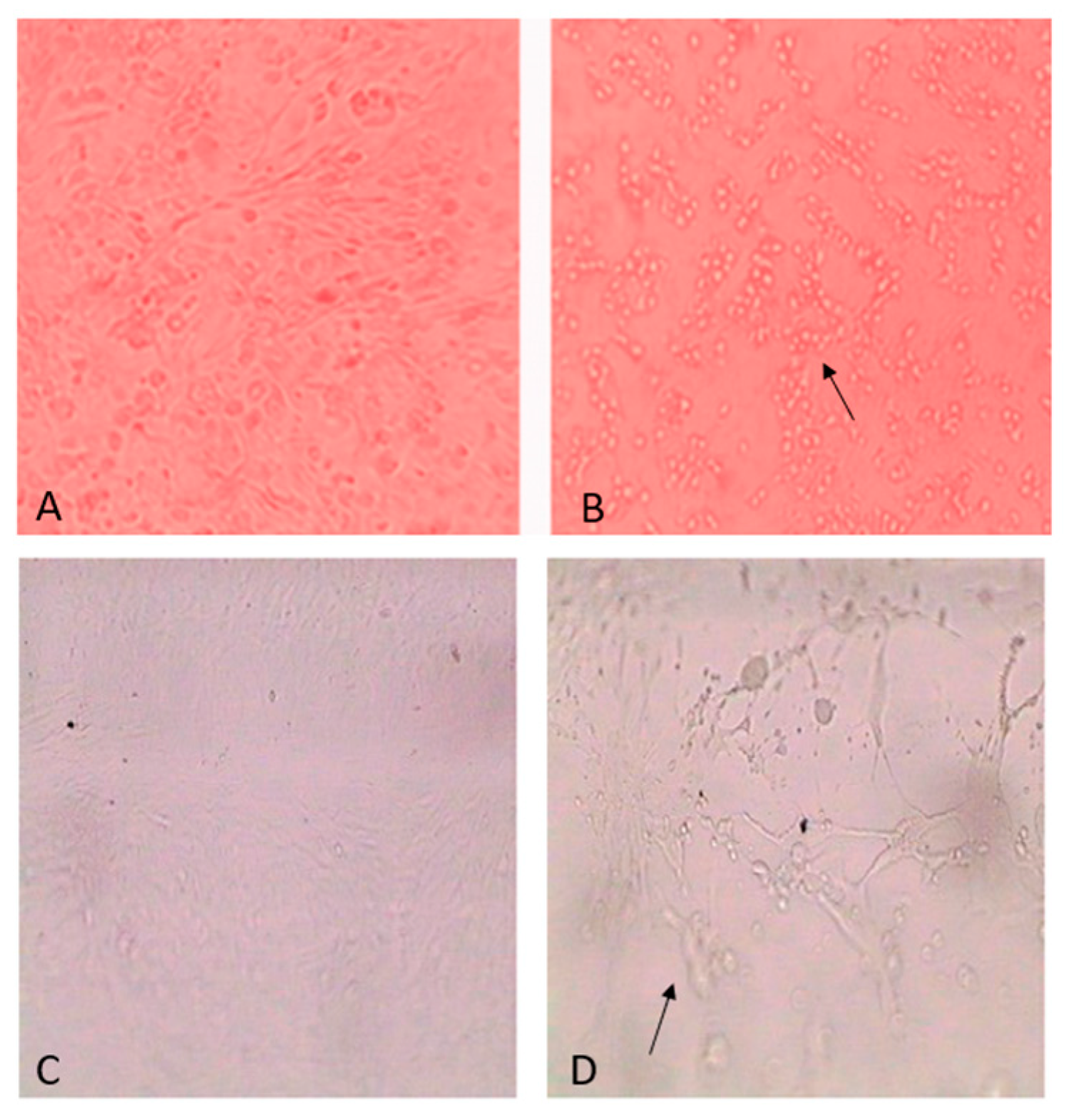

Following inoculation of the isolated virus into Vero and lamb kidney cell cultures, signs of a cytopathic effect (CPE) began to appear after 72 hours of incubation. The CPE was characterized by cell rounding, detachment from the substrate, and disruption of the cell monolayer. Viral DNA was extracted from the infected lamb kidney cell culture at the stage of pronounced CPE, indicating active viral replication in this cell line (

Figure 4).

These findings confirm the viability of the isolated virus and its ability to adapt to different cell cultures, thereby providing a foundation for further investigation, including molecular-genetic and antigenic characterization. All experiments were conducted in triplicate to ensure reproducibility and reliability of the results.

3.3. Molecular Genetic Analysis

The complete genome of the camelpox virus isolate obtained in this study (Camelpox virus/Beineu/2023) was sequenced using next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology. The genomic sequence was deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under the accession number PV920573.1. The total genome length was 202,273 base pairs (bp).

Comparative analysis of the Camelpox virus/Beineu/2023 genome with those of other members of the Orthopoxvirus genus revealed both conserved structural features and species-specific variations, which are important for understanding evolutionary relationships within the group. According to nucleotide sequence analysis performed using the BLASTN tool, the isolate showed 99.95% identity with Camelpox virus strains 0408151v (KP768318.1) and CMS (AY009089.1), as well as 99.76% identity with isolates obtained in the United Arab Emirates in 2021 (MZ300859.1, MZ300856.1, MZ300860.1, MZ300858.1, MZ300857.1) and an isolate from Israel in 2016 (MK910851.1).

Multiple sequence alignment was performed based on the assembled complete genome sequences of camelpox virus isolates. Phylogenetic analysis was carried out using MEGA software version 12, and a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Neighbor-Joining method (

Figure 5). Complete nucleotide sequences from the Genbank database were used for the analysis.

The constructed phylogenetic tree illustrates the evolutionary relationships among ten Camelpox virus isolates, which are primarily grouped according to their geographic origin. The analysis revealed that isolates from the United Arab Emirates and Israel form a distinct phylogenetic clade. In contrast, the Camelpox virus/Beineu/2023 isolate shows a high degree of genetic similarity to isolates CMS, 0408151v, and the previously described Kazakhstan strain M-96.

4. Discussion

Camelpox has a substantial economic impact in regions where camels play a vital role in agriculture. These animals are used not only as draft animals but also as sources of milk, meat, and wool. Although other types of livestock may fulfill similar functions, camels are classified as large ruminants, and the cost of a single camel often equals that of dozens of small ruminants. This makes camels particularly valuable to both farming and nomadic communities. Accordingly, the spread of infections such as camelpox poses a significant threat to livestock production and food security in affected regions. The disease has been reported in nearly all countries where camel husbandry is practiced [

18]. An analysis of epizootic data from the past decade indicates that sporadic cases have been recorded in countries such as Israel, Iraq, Eritrea, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan. Meanwhile, in eight countries – Iran, Libya, Oman, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Tunisia and Ethiopia – the disease is considered endemic, indicating stable circulation of the virus within camel populations [

14,

19].

This study presents a molecular genetic analysis of a virus isolate obtained from a clinically healthy camel during monitoring aimed at identifying potential natural reservoirs of the camelpox virus. Although no clinical signs of the disease were observed in animals from the studied regions, camelpox is known to circulate in a latent or subclinical form, particularly among adult animals in endemic areas [

16,

17,

20,

21]. Such asymptomatic infection complicates timely detection and highlights the critical importance of molecular diagnostic tools and continuous epidemiological surveillance, even in the absence of overt clinical symptoms. The results of phylogenetic analysis based on whole-genome sequences revealed clear clustering of Camelpox virus strains according to their geographic origin and time of isolation. Isolates obtained in 2020 (D1795/20, D1804/20, D1734/20, D1621/20, D1865/20) formed a distinct clade that is genetically distant from the Kazakhstan isolates. This suggests that these isolates originated from a different epizootic focus, presumably located in Saudi Arabia, and possess characteristic regional genomic features. Their high intragroup identity indicates a recent common ancestor and likely reflects a localized outbreak.

The

Negev2016 isolate, obtained in Israel, occupies a phylogenetically intermediate position between the Middle Eastern and Kazakhstan lineages. This may indicate the existence of potential transmission routes associated with animal migration or regional trade. According to whole-genome sequencing data, the

Negev2016 isolate differs from the Kazakhstan strain

M-96 by 349 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), with an overall sequence identity of 99.55% [

22].

The Camelpox strain

CMS, isolated in Iran in 1970, is a virulent reference isolate widely used in scientific research. Its genome encodes a unique v-slfn protein (encoded by the 176R gene), which is believed to modulate the host immune response without inhibiting cell proliferation [

23]. Phylogenetically, the

CMS strain is closely related to the Kazakhstan strain

M-96 and genetically distant from vaccine strains. It also shows a high degree of homology with Variola virus, with approximately 98% sequence identity in key genomic regions.

The Camelpox virus strain

0408151v is a laboratory-adapted reference isolate maintained in the National Collection of Pathogenic Viruses (NCPV, United Kingdom) [

24]. Its genome comprises 202,289 base pairs and is frequently used in research involving phylogenetic analysis and validation of diagnostic tools. Although the exact geographic origin of this strain is not reported in open-access sources, phylogenetic data suggest that it is closely related to field isolates circulating in the Middle East.

The isolate obtained in this study Camelpox virus/Beineu/2023, exhibits a high degree of genetic similarity to the M-96 strain, which was isolated in Kazakhstan more than 30 years ago. This finding confirms the long-term circulation of an endemic genetic variant of CMLV in Kazakhstan. The observed sequence identity exceeds 98%, indicating the genetic stability and evolutionary conservatism of the virus. These results suggest that the same genetic lineage of CMLV has been locally maintained with minimal evolutionary divergence. Camels themselves are likely to serve as the natural reservoir of the virus during interepizootic periods, supporting viral persistence and potential reactivation under stress-related conditions. The findings support the notion that CMLV maintains high genetic stability during natural circulation.

Nonetheless, the observed geographic clustering highlights the importance of region-specific molecular surveillance to ensure the early detection of novel variants and to prevent cross-border transmission. Additionally, phylogeographic mapping may contribute to clarifying outbreak sources and identifying epidemiological links between affected regions.

According to the literature, CMLV does not have a transmissible mechanism and spreads mainly through direct contact with infected animals, affected skin, or care items [

25,

26,

27]. However, it has been noted that during the rainy season, the incidence of the disease increases significantly [

3,

28]. This probably due to a combination of factors: crowding of animals in shelters, shared use of water sources, maceration of the skin due to high humidity, and a decrease in its barrier function [

29,

30]. An additional factor may be an increase in the number of insects and ticks, such as

Hyalomma dromedarii, which are capable of mechanically transferring the virus between animals. Also, against the background of seasonal climatic stress and weakened non-specific immunity, the susceptibility of camels to infection increases.

Consequently, the combination of epizootological data, molecular genetic analysis, and literature review suggests that camels may not only be susceptible hosts, but also serve as a natural reservoir of camelpox virus. This is supported by the detection of viral DNA in clinically healthy animals, the limited species specificity of the infection, and the genetic stability of viral isolates. Thus, the persistence of CMLV in camels and its periodic reactivation under unfavorable conditions play a key role in maintaining the long-term circulation of the virus and the cyclic nature of epizootics in endemic regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ye.B., Sh.T.; methodology, N.K., B.U., K. Zh., Zh. S., Zh.A., D.T., Sh.T.; software, K. Zh., B.U., A.U., R.A.; validation, Zh. K., A.K., Ye.B., М.М,. Sh.T.; formal analysis, Zh.A., D.M., A.K.; investigation, Zh.S., D.T., Sh.T., D.M.; resources, N.K., B.U., A.R. Sh.T.; data curation, N.K., K.Zh., A.U., R.A.; writing—original draft preparation, Sh.T., Ye.B.; writing article and editing, Ye.B., Sh.T.; visualization, Zh.A., D.T., A.K.; supervision, M.M., Ye.B.; project administration, Ye.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan within the framework of the Grant Project "Identification of possible reservoirs of camelpox virus in Western Kazakhstan", Grant number: AP19676030.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study is a continuation of an earlier study within the framework of a grant project [

16].

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are included in the manuscript or are available on request from the corresponding author. The virus genomes sequenced in this study have been deposited in GenBank using the accession numbers PV920573.1.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the staff of the Research Institute of Biological Safety Problems for scientific and technical support and provision of data used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the study’s design; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CMLV |

Camelpox Virus |

| CAM |

Chorioallontoic membrane |

| CPE |

Cytopathic effect |

| NCPV |

National Collection of Pathogenic Viruses |

| NCBI |

National Center for Biotechnology Information |

References

- OIE. Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals, Camelpox. OIE, 2012, 1175–1182. https://ru.scribd.com/document/296368273/OIE-Manual-of-Diagnostic-Tests-and-Vaccines-for-Terestrial-Animals-Vol-2-Ecvine-Leporide-Suine-Caprine.

- Wernery, U.; Kaaden, O.R. Camel pox. In Infectious Diseases in Camelids, 2nd ed.; Blackwell Science: Berlin, Germany, 2002, 176–185. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9780470699058#aboutBook-pane .

- Wernery, U.; Ulrich, A. Orthopox virus infections in dromedary camels in United Arab Emirates during winter season. J. Camel Pract. Res. 1997, 4, 51–55. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/19972213862.

- Duraffour, S.; Meyer, H.; Andrei, G.; Snoeck, R. Camelpox virus. Antiviral Res. 2011, 92, 167–186. [CrossRef]

- Kriz, B.A. Study of camelpox in Somalia. J. Comp. Pathol. 1982, 92, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Coetzer, J.A.; Tustin, R.C. Infectious Diseases of Livestock, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Infectious-diseases-of-livestock.

- Bera, B.C.; Shanmugasundaram, K.; Sanjay, B.; et al. Zoonotic cases of camelpox infection in India. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 152, 29–38. [CrossRef]

- Yousif, A.A.; Al-Naeem, A.A. Molecular Characterization of Enzootic Camelpox Virus in the Eastern Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Virol. 2011, 7, 135–146. [CrossRef]

- Afonso, C.L.; Tulman, E.R.; Lu, Z.; Zsak, L.; Sandybaev, N.T.; Kerembekova, U.Z.; et al. The genome of camelpox virus. Virology. 2002, 295, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Khalafalla, A.I.; Ali, Y.H. Observations on risk factors associated with some camel viral diseases. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference of the Association of Institutions for Tropical Veterinary Medicine (AITVM), Montpellier, France, 2007. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256942811_Observations_on_Risk_Factors_Associated_with_Viral_Diseases_of_Camels_in_Sudan.

- Bhanuprakash, V.; Balamurugan, V.; Hosamani, M.; et al. Isolation and characterization of Indian isolates of camelpox virus. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2010, 42, 1271–1275. [CrossRef]

- Gubser, C.; Smith, G.L. The sequence of camelpox virus shows it is most closely related to variola virus, the cause of smallpox. J. Gen. Virol. 2002, 83, 855–872. [CrossRef]

- OIE-WAHIS. Disease situation: Camelpox, 2020. https://wahis.oie.int/#/dashboards/country-or-disease-dashboard.

- Maikhin, K.T.; Berdikulov, M.A.; Musayeva, G.K.; Pazylov, Y.K.; Zhusambayeva, S.I.; Shaimbetova, A.K.; Sarmanov, A.M. The epizootological situation in the world and Kazakhstan on camelpox. Int. J. Humanit. Nat. Sci. 2022, 7, 158–165. (In Russian). https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/epizootologicheskaya-situatsiya-v-mire-i-kazahstane-po-ospe-verblyudov.

- Mambetaliyev, M.; Kilibayev, S.; Kenzhebaeva, M.; et al. Field Trials of Live and Inactivated Camelpox Vaccines in Kazakhstan. Vaccines. 2024, 12, 685. [CrossRef]

- Bulatov, Y.; Turyskeldy, S.; Abitayev, R.; et al. Camelpox Virus in Western Kazakhstan: Assessment of the Role of Local Fauna as Reservoirs of Infection. Viruses, 2024, 16, 1626. [CrossRef]

- Turyskeldy, Sh.S.; Kondybayeva, Zh.B.; Amanova, Zh.T.; et al. Possible reservoirs of camelpox virus. Microbiol. Virol. 2024, 2(45). [CrossRef]

- Balamurugan, V.; Venkatesan, G.; Bhanuprakash, V.; Singh, R.K. Camelpox, an emerging orthopox viral disease. Indian J. Virol. 2013, 24, 295–305. [CrossRef]

- Stovba, L.F.; Lebedev, V.N.; Chukhralia, O.V.; et al. Epidemiology of Camelpox: New Aspects. J. NBC Prot. Corps. 2023, 7, 248–260. (In Russian). [CrossRef]

- Bhanuprakash, V., Prabhu, M., Venkatesan, G., Balamurugan, V., Hosamani, M., Pathak, K. M., & Singh, R. K. Camelpox: epidemiology, diagnosis and control measures. Expert review of anti-infective therapy. 2010, 10, 1187–1201. [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, S.S.; Kumar, S.; Mehta, S.C.; et al. Camelpox: A brief review on its epidemiology, current status and challenges. Acta Trop. 2016, 158, 32–38. [CrossRef]

- Israeli, O.; Cohen-Gihon, I.; Zvi, A.; et al. Complete Genome Sequence of the First Camelpox Virus Case Diagnosed in Israel. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2019, 8. [CrossRef]

- Gubser, C.; Goodbody, R.; Ecker, A.; et al. Camelpox virus encodes a schlafen-like protein that affects orthopoxvirus virulence. J. Gen. Virol. 2007, 88, 1667–1676. [CrossRef]

- UK Health Security Agency. Culture Collections.: https://www.culturecollections.org.uk/nop/product/camelpox-virus.

- Duraffour, S.; Meyer, H.; Andrei, G.; Snoeck, R. Camelpox virus. Antiviral Res. 2011, 92, 167–186. [CrossRef]

- Diriba, A.B. Review on Camel Pox: Epidemiology, Public Health and Diagnosis. ARC J. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2019, 5, 22–33. [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, M.; Yogisharadhya, R.; Pavulraj, S.; et al. Camelpox and buffalopox: Two emerging and re-emerging orthopox viral diseases of India. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2015, 3, 527–541. [CrossRef]

- Kriz, B. A Study of Camelpox in Somalia. J. Comp. Pathol. 1982, 92, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Bhanuprakash V, Prabhu M, Venkatesan G, Balamurugan V, Hosamani M, Pathak KML, Singh RK. Camelpox: epidemiology, diagnosis and control measures. Exp. Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2010a, 8, 10, 1187-1201. [CrossRef]

- WOAH. Terrestrial Manual 2021. Chapter 3.5.1. Camelpox. 2021, 1–15. Available online: https://www.woah.org/fileadmin/Home/fr/Health_standards/tahm/3.05.01_CAMELPOX.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).