1. Introduction

Aviation’s climate impact stems from both CO

2 and non-CO

2 effects, including soot, aerosols, water vapor, NO

x emissions, and contrail-induced cirrus clouds [

1,

2,

3]. Currently, aviation contributes 3.5% to anthropogenic radiative forcing, with non-CO2 effects accounting for approximately two-thirds of this impact [

1,

2,

3]. Despite the pandemic, air travel demand is projected to double over the next two decades (2024–2043) [

4], significantly exacerbating aviation’s climate footprint. While advancements in aircraft technology and low-carbon fuels could address 80% of the measures needed for carbon-neutral growth [

5,

6], achieving this goal requires a comprehensive understanding of life cycle emissions.

Life cycle emissions from aviation fuels encompass both operational and production phases, with the former contributing ~70% of total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions for Jet-A fuel [

7]. Current regulatory and technological efforts primarily focus on operational emissions, but a holistic approach is essential to evaluate the sustainability of alternative fuels. Tools like the GREET model [

8] enable comprehensive life cycle assessments, revealing that not all alternative fuel pathways have low embodied GHG emissions. For instance, while liquid hydrogen (LH

2) offers zero operational emissions and higher energy density than Jet-A, its life cycle GHG emissions can be 3 times as that of conventional Jet-A fuel, when derived from coal.

Decarbonizing long-haul aviation remains a significant challenge [

6,

9]. Presently, 100% synthetic paraffin kerosene (SPK) is not permitted for use in the existing aircraft fleet. Approved drop-in fuels for civil aviation use include up to a 50% blend of alcohol-to-jet (ATJ), Fischer-Tropsch (FT), and hydro-processed renewable or hydro-processed esters and fatty acids (HRJ or HEFA) SPK pathways, as well as a 10% blend of sugar-to-jet (STJ) SPK pathway [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Among the alternatives, LH

2 and 100% SPK are the only viable options for long-range, large twin-aisle (LTA) aircraft, whether tube-wing or blended wing body designs [

6,

14,

15,

16]. However, existing studies on SPK and LH

2 often focus solely on operational impacts, neglecting embodied emissions from fuel production [

17,

18]. A holistic evaluation framework is therefore critical to identify sustainable fuel pathways and assess their life cycle performance.

This study adopts a life cycle approach to evaluate fuel feedstock and production pathways for LH

2 and 100% SPK, aiming to enable climate-neutral long-range flights for LTA aircraft. By integrating operational and embodied emissions, this work contributes to the development of a methodological framework for sustainable aviation, addressing gaps identified in recent reviews [

19,

20,

21]. The analysis focuses on combustion-based LTA aircraft, providing insights into the potential of LH

2 and 100% SPK as alternatives to conventional Jet-A fuel.

Numerous studies have conducted life cycle or well-to-wake (WTWa) emissions analyses for SPK and LH

2 fuels across various aircraft range applications. These include fossil fuel-based SPK [

22], bio-jet fuel e.g., [

23,

24,

25,

26], power-to-liquid (PtL) or electro-fuel e.g., [

27,

28], and LH

2 (e.g., [

29,

30]. However, none of these studies comprehensively examine the combination of feedstocks and manufacturing pathways required to achieve climate-neutral long-range flights for LTA aircraft powered by LH

2 and 100% SPK (bio-jet and PtL fuels). Additionally, many of these analyses exclude non-CO

2 emissions in their WTWa assessments, limiting their applicability to sustainable aviation goals.

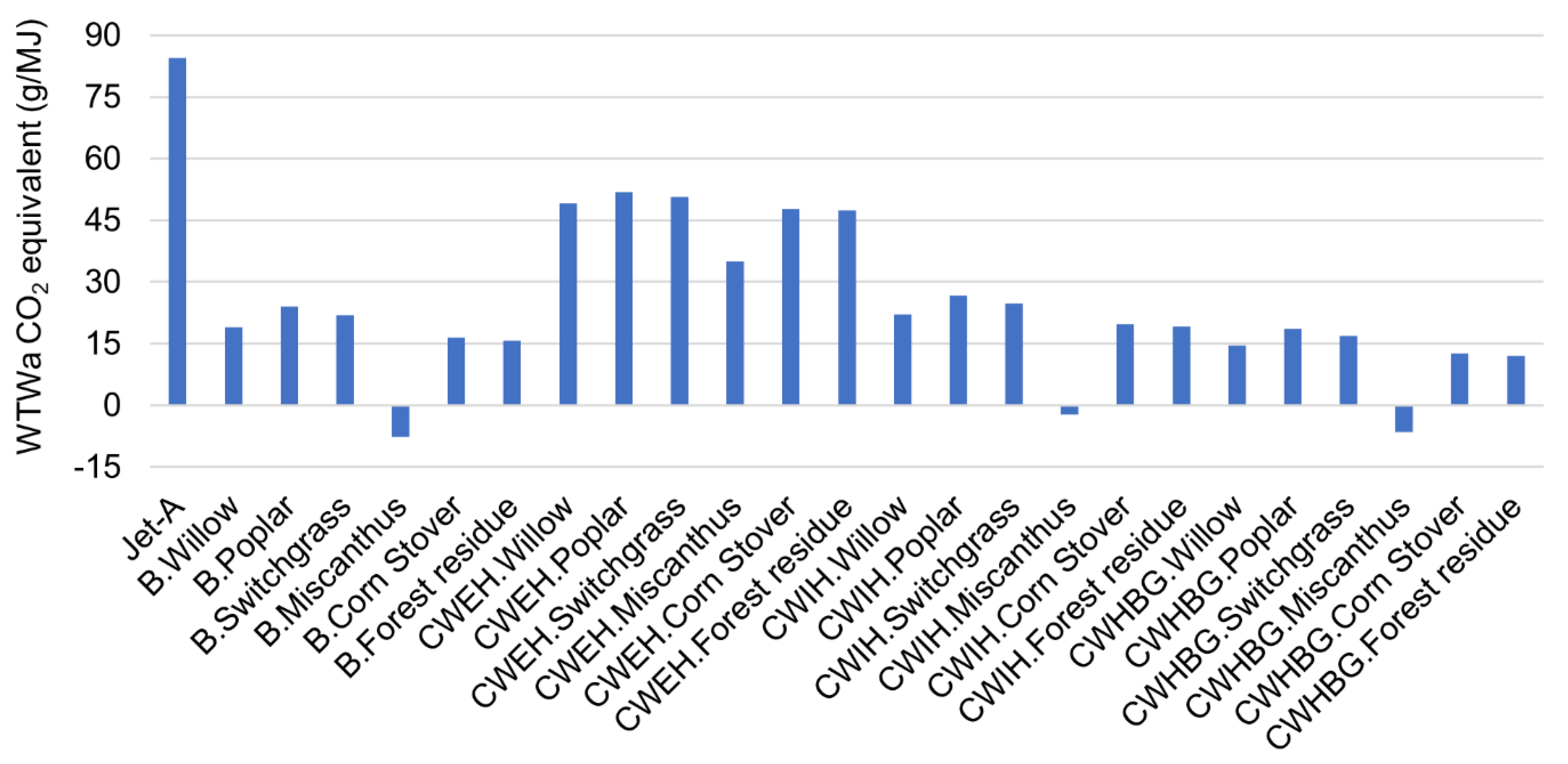

Key findings from recent reviews highlight the potential of alternative fuels to reduce WTWa GHG emissions. For instance, Lau et al. [

31] report that HEFA and alcohol-to-jet (ATJ) bio-jet fuels can reduce WTWa GHG emissions by 19–42% and 20–65%, respectively. Braun et al. [

25] find that Fischer-Tropsch (FT) SPK fuel derived from miscanthus, agricultural residues, and municipal solid waste can achieve up to 100% reduction in WTWa GHG emissions, with regional variations exceeding 125%. Ansell [

32] notes that bio-jet fuel and renewable hydrogen can reduce WTWa CO

2 emissions by 68% and ~80%, respectively, assuming a fully renewable grid. However, these studies do not account for non-CO

2 emissions, which are critical for a holistic assessment of aviation’s climate impact.

Afonso et al. [

23] and Song et al. [

33] demonstrate that bio-jet fuels can reduce WTWa GHG emissions by up to 80% (including non-CO

2 emissions) and 41–89% (excluding non-CO

2 emissions), depending on feedstock and production pathways. Despite these advancements, existing research often focuses on limited or selective feedstocks, leaving gaps in understanding the full potential of alternative fuels for decarbonizing long-haul aviation.

For further details on manufacturing pathways, fuel properties, operability issues, and other aspects of alternative fuels, readers are directed to comprehensive reviews by Su-ungkavatin et al. [

34]), Cabrera and Sousa [

35], Ansell [

32], and Braun et al. [

25]. A detailed review of selected studies is also provided in Supplementary Information (SI) file SI §1.

Kolosz et al. [

22] compare WTWa performance metrics for blended/drop-in SPK fuels, including fossil fuel-based SPK (derived from coal, oil sands, oil shale, and natural gas) and bio-jet fuels (first, second, and third generation). Similarly, Wei et al. [

36], Pavlenko et al. [

37], and De Jong et al. [

24] assess WTWa emissions for bio-jet fuels but focus on limited biomass feedstocks. Studies by the International Civil Aviation Organization [

38] and Prussi et al. [

39] explore bio-jet fuels using feedstocks listed in the CORSIA database, while Van Der Sman et al. [

40] review WTWa emissions for SPK fuels (bio-jet and PtL) within the EU region. Saad et al. [

41] estimate a ~50% reduction in WTWa emissions for PtL and bio-jet fuels but limit their analysis to Switzerland. Notably, none of these studies account for non-CO

2 emissions from aircraft operations in their WTWa analyses.

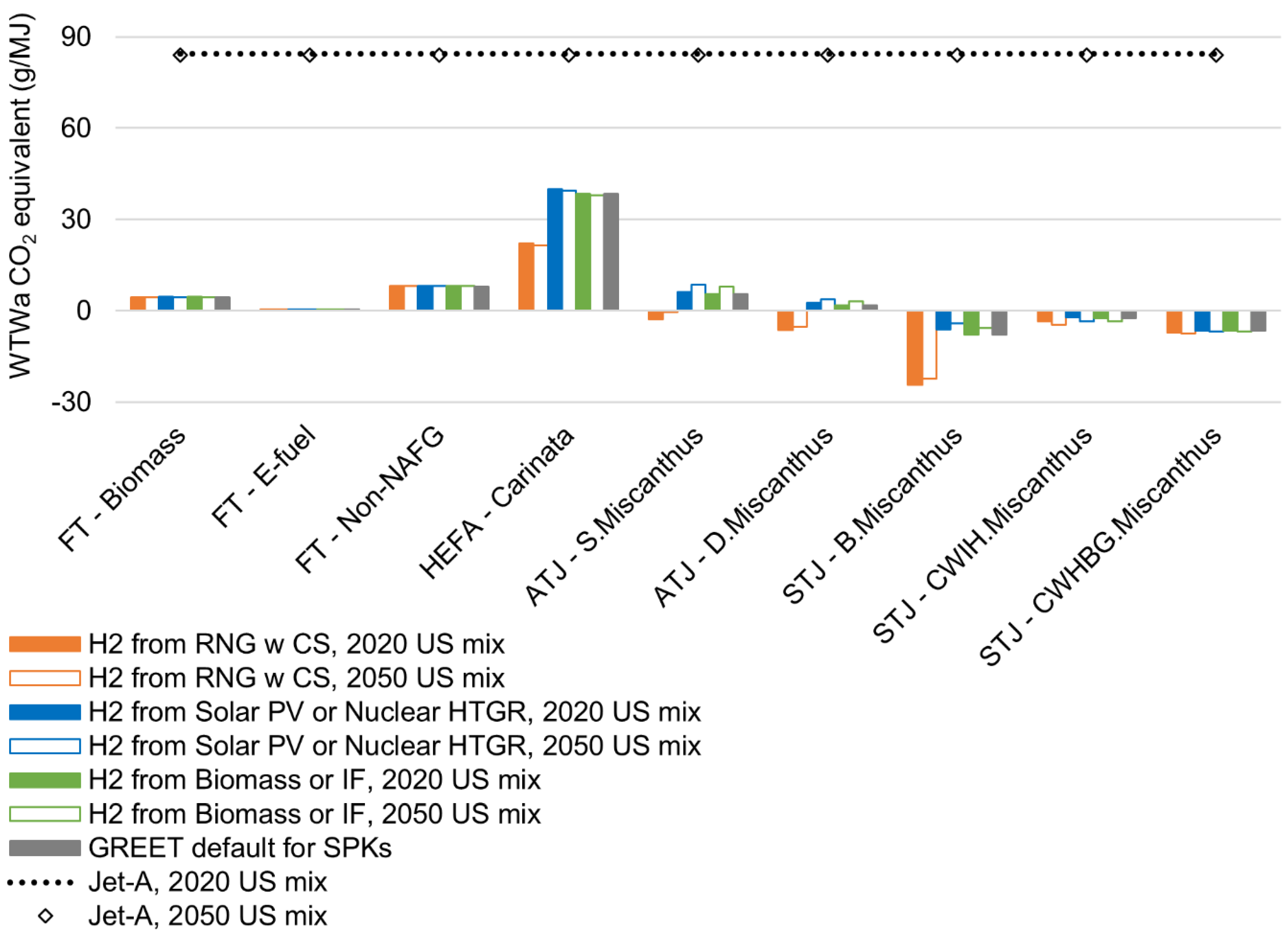

Grim et al. [

42] report that PtL fuels can reduce WTWa GHG emissions by 66–94% (excluding non-CO

2 effects). In the study by Grim et al., the wide range of 66–94% reduction is attributable to the variability in the sourcing of (carbon) feedstock (direct air capture or point based carbon sourcing). while Sacchi et al. [

43] find reductions of 65–100% (including non-CO

2 effects) for PtL derived from direct air capture and carbon storage. Micheli et al. [

44] and Papantoni et al. [

45] highlight the role of renewable energy in PtL production, with Micheli et al. [

44] reporting WTWa GHG reductions of 27.6–46.2% (with non-CO

2 effects) and 52.6–88.9% (without non-CO

2 effects) for PtL produced using wind power in Germany. Papantoni et al. [

45] observe reductions of 32% (solar) and 42% (wind) when non-CO

2 emissions are included. Klenner et al. [

46] find that PtL and LH

2 produced using wind power in Norway reduce WTWa GHG emissions by 48% and 44%, respectively, for short flights (<200 km), with higher reductions (52% for PtL and 54% for LH

2) for longer flights. VanLandingham [

47] and VanLandingham and Hall [

48] report WTWa GHG reductions of 43% (PtL) and 61% (LH

2) for a Boeing 737, while Prashanth et al. [

49] estimate reductions of 84–93% (PtL) and 91–98% (LH

2) depending on the renewable energy source (solar or wind). Studies by the German Environment Agency (2016) and Schmidt et al. [

28] project near-100% WTWa GHG reductions for PtL in Germany’s future energy mix. However, these analyses are often limited to specific energy landscapes or feedstocks, and the life cycle GHG performance of PtL and LH

2 depends heavily on CO

2 sourcing (direct air capture vs. point sources) and the electricity mix used in production.

Delbecq et al. [

27] evaluate the WTWa performance of bio-jet fuel, PtL, and hydrogen at the aviation system level for a small aircraft. However, the individual WTWa GHG reduction potential of each fuel remains unclear, and the feedstock sourcing for bio-jet fuel is unspecified, while PtL and hydrogen are limited to renewable energy. Fantuzzi et al. [

50] assess alternative aviation fuels but focus on limited feedstocks/pathways for bio-jet fuel (HEFA and ATJ), PtL, and hydrogen (steam methane reformation [SMR] and electrolysis), achieving up to 70% WTWa GHG savings (excluding non-CO

2 emissions). Their analysis is restricted to the UK energy landscape. [

51] provide a detailed evaluation of alternative fuels, including bio-jet fuel (ATJ, HEFA, FT), PtL (using direct air capture), and hydrogen (electrolysis with renewable power), considering non-CO

2 emissions. They project an 89–94% reduction in WTWa GHG emissions by 2050, accounting for efficiency improvements and contrail avoidance, despite a 2–3x increase in demand. However, their study examines limited feedstocks for each fuel.

Quante et al. [

52] report WTWa GHG reductions (excluding non-CO

2 emissions) of 85% (FT SPK), 100% (PtL), 54% (HEFA SPK), 62% (ATJ SPK), 61% (STJ SPK), and 80% (hydrogen), though specific bio-jet fuel feedstocks are unspecified. Penke et al. [

53] find WTWa GHG reductions (excluding non-CO

2 emissions) of 77% (PtL), 30% (HEFA from soy oil), and 95% (renewable hydrogen). Kossarev et al. [

54,

55] focus on renewable hydrogen, algae-based HEFA, and hydrogenated vegetable oil, achieving WTWa GHG reductions (including non-CO

2 emissions) of 59.5%, 35.8%, and 112%, respectively. These studies are limited to specific energy landscapes or feedstocks, restricting their broader applicability.

Studies on hydrogen as an aviation fuel [

56,

57,

58] frequently exclude non-CO

2 emissions, a critical oversight. Similar limitations are found in other prior studies [

30,

50,

52,

59,

60]. Additionally, many studies [

56,

57,

61] limit feedstock/pathway selection to renewable power, neglecting other potential sources. These similar limitations are observed in other previous literature [

30,

58,

62,

63]. The impact of aircraft use-phase energy consumption and emissions on WTWa performance is significant, yet studies often fail to account for the poor volumetric energy density of LH

2, which penalizes aircraft energy performance.

Koroneos et al. [

61] examine LH

2 for an A320-type aircraft, considering realistic design effects, but their analysis is outdated and limited in LH

2 production methods. Mukhopadhaya and Rutherford [

30] project ~100% WTWa GHG reductions (excluding non-CO

2 emissions) for PtL and LH

2 from renewable electrolysis. Tveitan [

57] reports a 58% WTWa GHG reduction (excluding non-CO

2 emissions) for green hydrogen, while Chan et al. [

58] find that green hydrogen and bio-jet fuel (feedstock unspecified) can achieve up to 88% WTWa GHG reductions. However, these studies often omit non-CO

2 emissions, limiting their comprehensiveness.

Miller [

64] and Miller et al. [

65] expand on previous studies by evaluating a broader range of feedstocks and pathways for LH

2 and bio-jet fuels, incorporating contrail-cirrus effects in their WTWa analysis. However, their work excludes PtL or electro-fuels and the STJ pathway, and their results are limited to smaller, shorter-range aircraft, unlike the LTA aircraft focus of this study. The FlyZero report [

66] addresses performance penalties from cryogenic tank installation and includes non-CO

2 emissions in its WTWa analysis of LH

2, PtL, and bio-jet SPK fuels for small to mid-size aircraft. Nevertheless, it examines only a limited number of feedstocks and manufacturing pathways for these fuels.

A critical gap in the existing literature is the lack of comprehensive WTWa analyses that include non-CO

2 emissions and explore diverse feedstock and manufacturing pathway combinations for achieving climate-neutral long-range flights using LH

2 and 100% SPK (bio-jet and PtL fuels). While studies such as Afonso et al. (2023), Ansell (2023), and others provide valuable insights, they often focus on specific energy landscapes, limited feedstocks, or exclude non-CO

2 effects. Furthermore, none of these studies consider fuel production routes that integrate carbon capture and storage (CCS), except for Fantuzzi et al. [

50], who demonstrate that CCS in SMR-based LH

2 production can reduce WTWa GHG emissions by 60% (median value). Pavlenko and Searle [

67] highlight hydrogen’s critical role in SPK fuel production, emphasizing that green hydrogen can significantly reduce WTWa GHG emissions. However, the sensitivity of hydrogen production to SPK life cycle emissions remains unexplored.

According to the International Air Transport Association [

68], achieving net-zero CO

2 emissions by 2050 will require a combination of strategies: sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) contributing 65%, new aircraft technologies (e.g., electric and hydrogen) 13%, operational efficiencies 3%, and offsets/carbon capture 19%. Carbon removal is identified as a key strategy, yet its integration into fuel production pathways is underexplored. Additionally, none of the reviewed studies estimate the energy demand for long-haul aviation in 2050 or assess whether this demand can be met entirely with 100% SPK (or SAF) and/or LH

2.

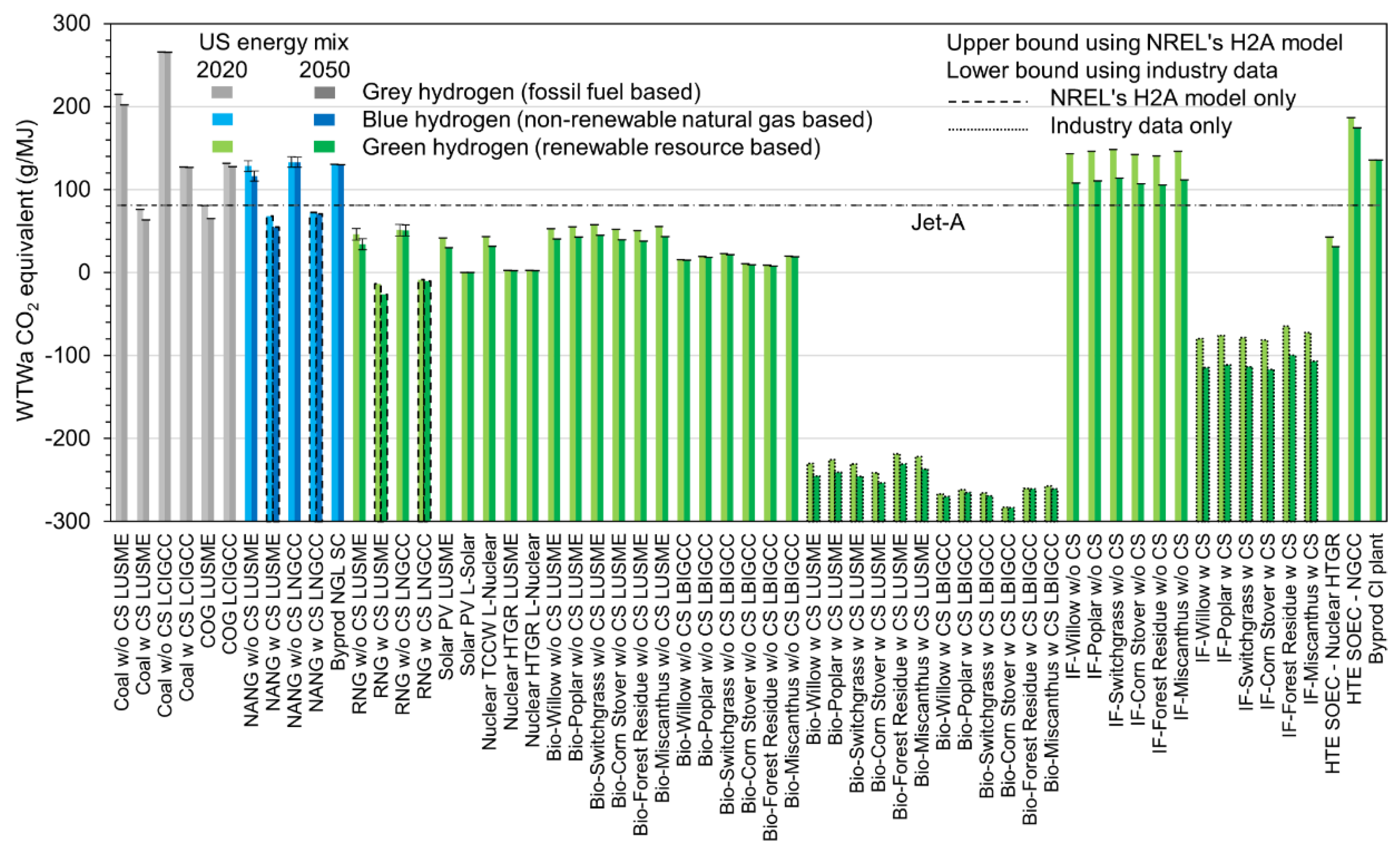

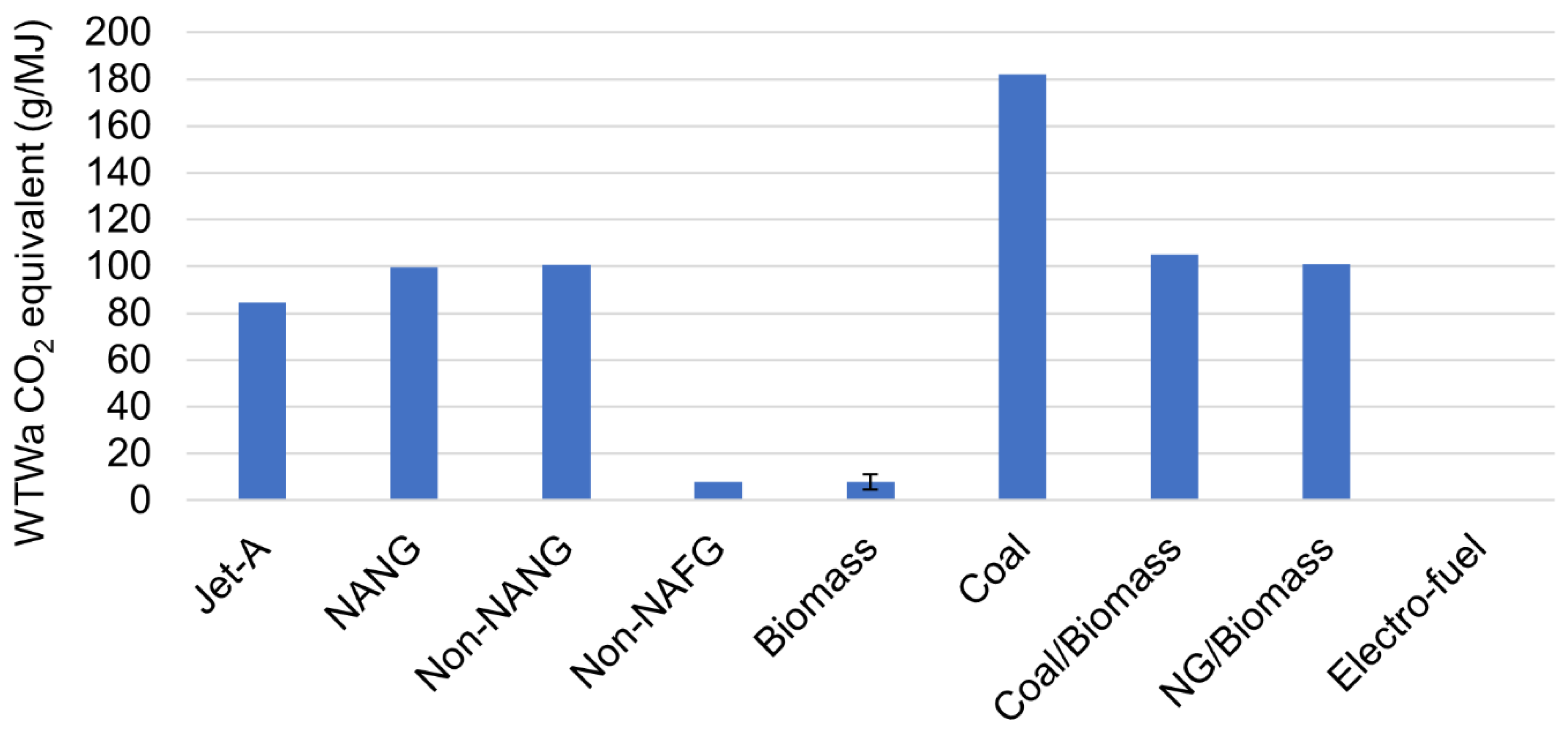

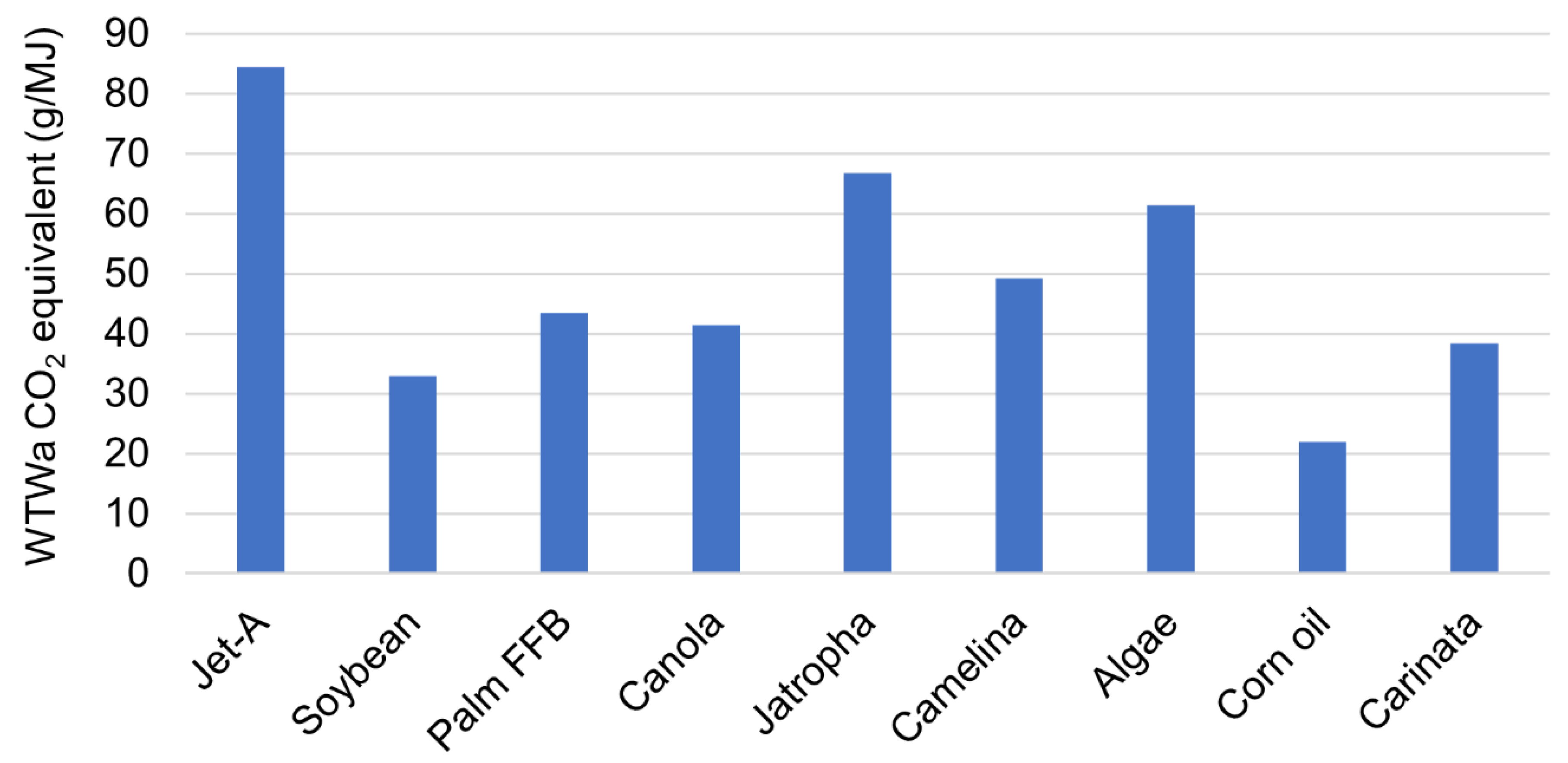

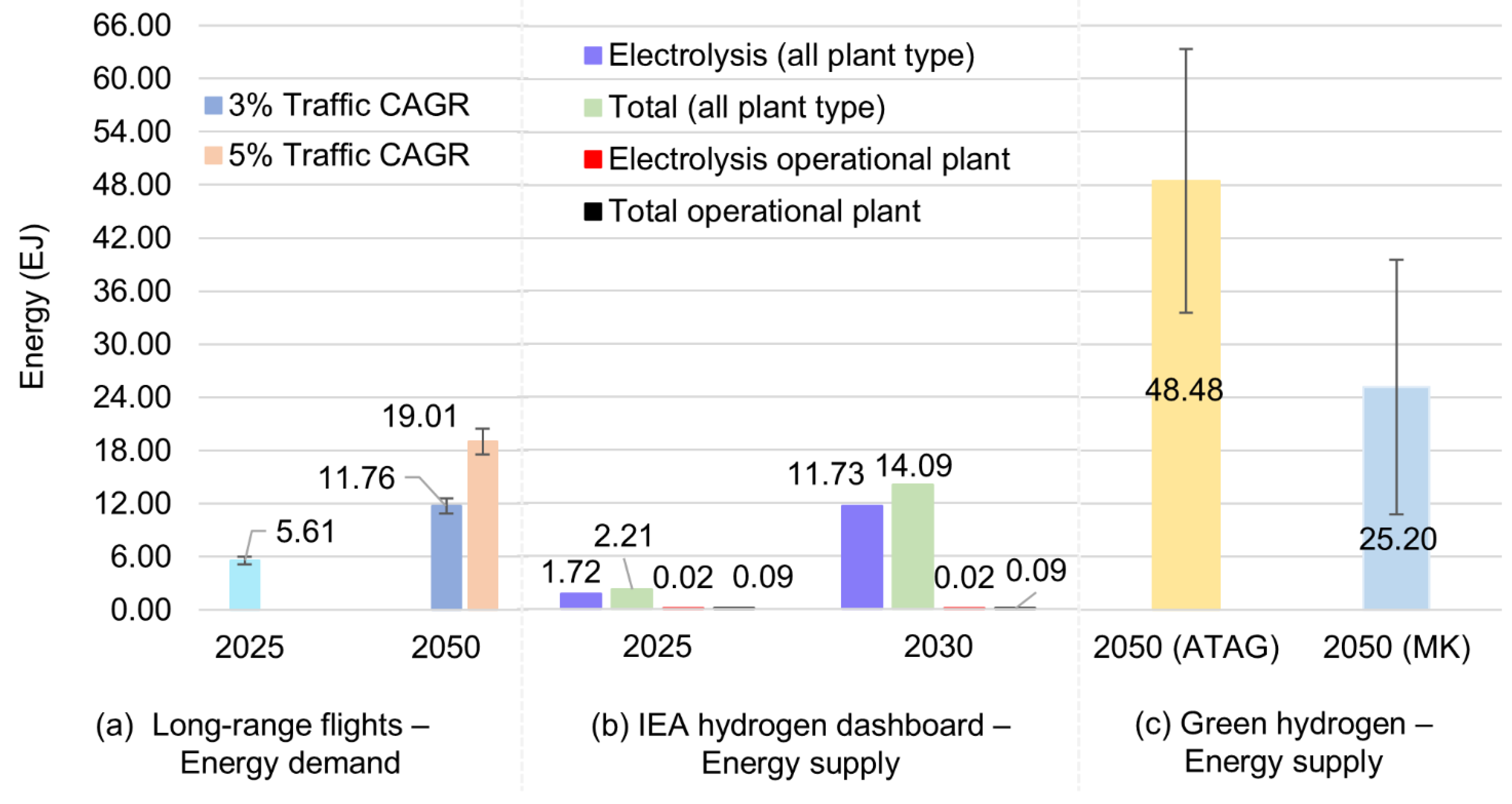

The limitations in existing literature motivate this study, which aims to address critical gaps in understanding the life cycle or WTWa GHG performance of long-range LTA aircraft powered by LH2 and 100% SPK, including bio-jet and PtL fuels. This work evaluates over 100 feedstocks and manufacturing pathways, some incorporating CCS, while accounting for non-CO2 emissions. Additionally, it investigates the sensitivity of hydrogen sourcing to SPK production, biomass sourcing for hydrogen pathways, and the impact of energy mix transitions (2020 vs. 2050). The study also estimates future (2050) energy demand and supply for long-haul aviation using 100% SPK (or SAF) and LH2, providing novel contributions to the field.

In the authors’ previous work [

15,

16], the engine and operational energy performance of a 2030+ (N+2 timeframe) blended wing body (BWB) LTA aircraft powered by LH

2 and 100% SPK was conducted while incorporating penalties from cryogenic tank installation for LH

2. These prior studies based on conceptual design/low order modelling enable estimation of use-phase GHG emissions in the present work, which, combined with manufacturing-phase emissions, facilitates comprehensive WTWa or life cycle emissions analysis. Because the prior studies were conducted using low order modelling, the use phase emission estimation in this work is of low fidelity level. Over 100 production pathways for LH

2, PtL, and bio-jet SPK are examined, including those employing CCS. The primary objectives of this work are:

Develop a database of energy, emissions, and materials inventory for alternative fuels produced via various pathways.

Assess sensitivities of hydrogen sourcing to SPK production and biomass sourcing for hydrogen pathways.

Evaluate aircraft operational-phase emissions, including non-CO2 effects.

Estimate future energy demand and supply (2050) for 100% SPK (or SAF) and LH2 in long-haul aviation.

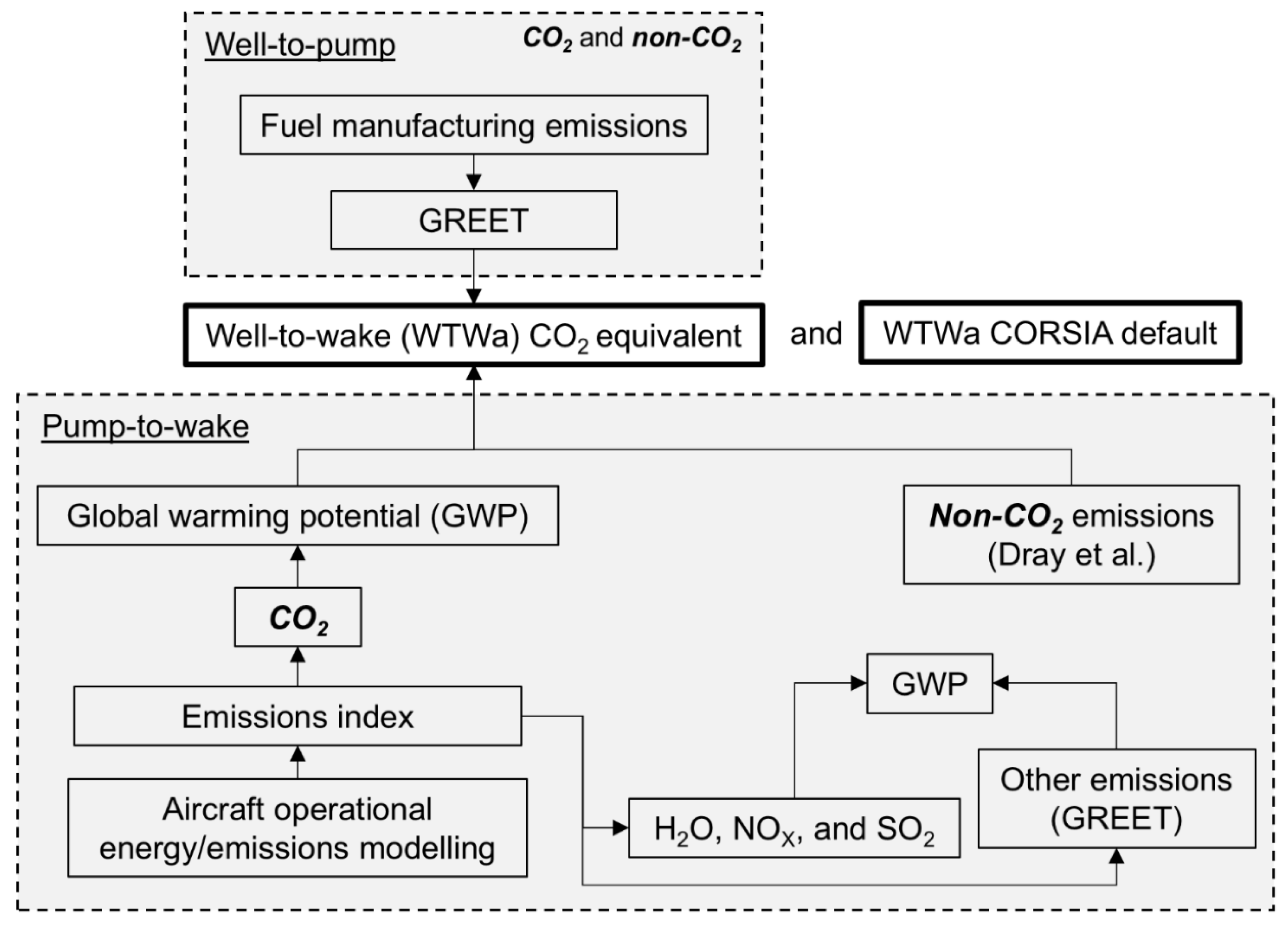

In addition to quantifying CO

2-equivalent emissions, this study evaluates unintended effects of LH

2 and 100% SPK use, such as fossil fuel consumption, water use, and other emissions. The GREET model [

8], CORSIA default values, and literature are used to create an inventory of manufacturing-phase CO

2-equivalent emissions for over 100 fuel production pathways. Use-phase emissions are modeled for a 2030+ BWB aircraft powered by LH

2 and 100% SPK, incorporating non-CO

2 emissions from literature to estimate WTWa CO

2-equivalent emissions. Further details are provided in the Supplementary Information (SI) document.

4. Conclusions

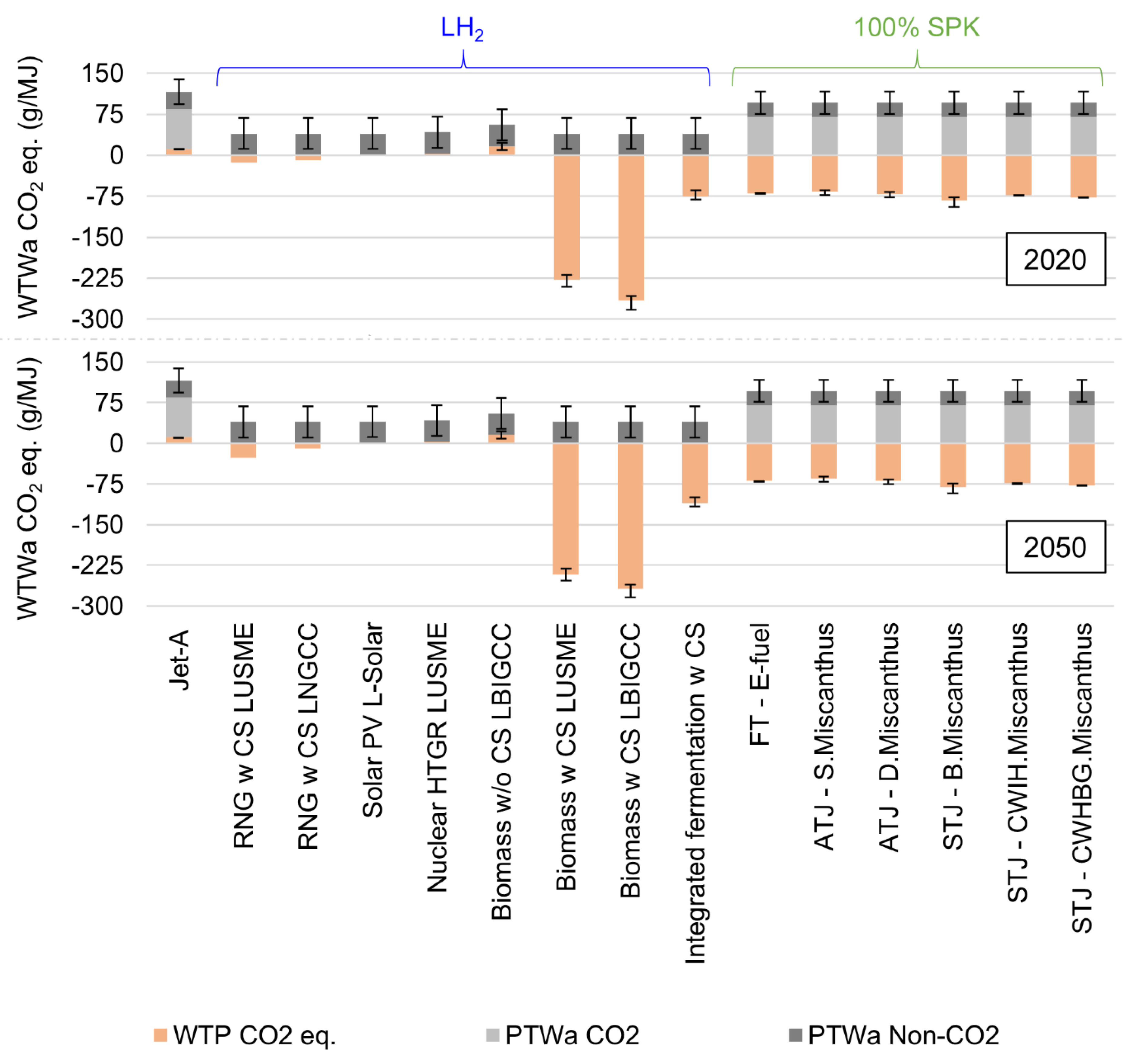

Liquid hydrogen and 100% synthetic paraffin kerosene could serve as alternatives to Jet-A for long-haul aviation, provided they are produced from feedstocks and/or processes that ensure zero life cycle well-to-wake emissions. In this work, the life cycle or well-to-wake performance is evaluated for long-range large twin aisle aircraft powered by liquid hydrogen and 100% synthetic paraffin kerosene or SAF (separately) manufactured from different feedstocks and/or pathways. The GREET model is used for making a database of fuel manufacturing phase emissions for liquid hydrogen and 100% synthetic paraffin kerosene (bio-jet and power-to-liquid fuel), and the use-phase emissions are quantified separately in this work. In this work, the sensitivity of hydrogen sourcing to SPK production, and of biomass sourcing for some hydrogen production pathways, are addressed. Similarly, this work addresses the sensitivity of energy mix to alternative fuel production.

After examining over 100 different ways in total for producing liquid hydrogen and 100% synthetic paraffin kerosene, it is observed that liquid hydrogen fuel can enable net zero or negative well-to-wake CO2 equivalent emissions for long-range (blended wing body aircraft) flight of 300 passengers where liquid hydrogen fuel is produced from Biomass (liquefication is done using US electricity mix and manufacturing unit employing carbon sequestration) (260.8% – 266.1% reduction), Biomass (liquefication is done using electricity from biomass integrated gasification combined cycle and manufacturing unit employing carbon sequestration) (296.2% – 302.6% reduction), and/or integrated fermentation with carbon sequestration (96.2% – 150.7% reduction). This aligns with the decarbonization strategies of the International Air Transport Association of use of alternative fuel and carbon capture. Also, it is found that non-CO2 emissions are significant to the net well-to-wake CO2 equivalent emissions, and operational strategies need to be employed for reducing contrail formation. It is to be noted that the quantification of non-CO2 effects (such as contrails) from hydrogen aircraft in literature is relatively at a nascent stage and more research work is required. The well-to-wake CO2 equivalent emissions of 100% synthetic paraffin kerosene long-range (blended wing body aircraft) flight of 300 passengers can be reduced (on an average) by 70% – 85% (depending on SAF manufacturing pathways), using miscanthus as a feedstock, compared to Jet-A. It is to be noted that there could be a significant variability in the life cycle emissions for any given fuel and the manufacturing pathway, especially due to the carbon intensity of the sourced feedstock.

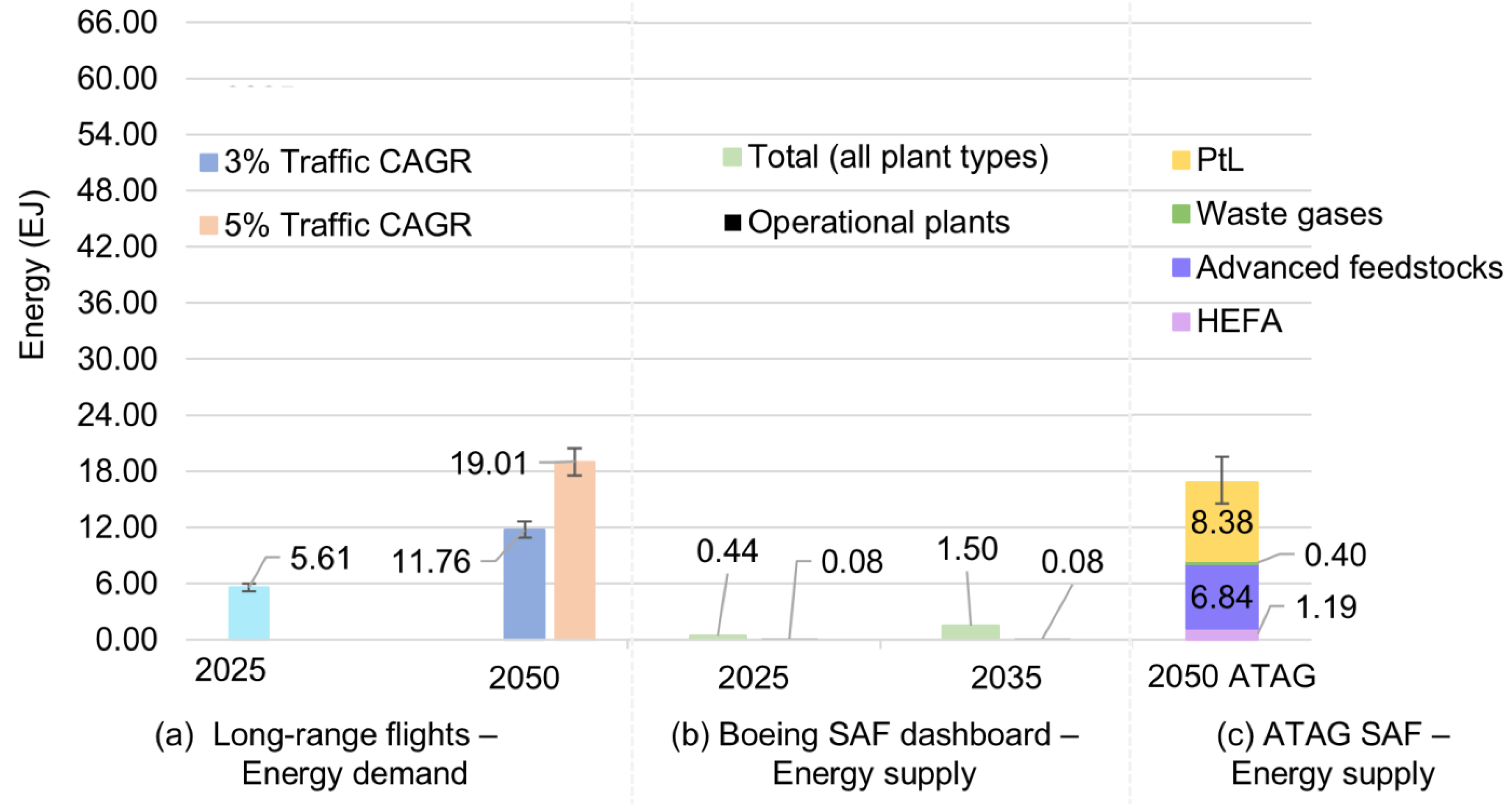

Based on the high-level analysis in this work, the projected SAF and hydrogen supply in 2050 can meet the energy demand of long-haul aviation with the current air traffic CAGR of 4%, assuming all flights are powered solely by one of these two fuels. However, if the air traffic CAGR increases to 5% and other sectors also compete for energy, production capacities, especially for hydrogen, will need to be scaled up. Alternatively, a mix of SAF and hydrogen could be used for long-haul flights, ensuring the energy supply meets the demand while also satisfying the needs of other sectors. In any case, achieving climate-neutral long-haul aviation will require boosting the production capacities of SAF and hydrogen beyond current projections.

The perspective used to select three feedstock and/or pathways for liquid hydrogen fuel identified in this work, only take into consideration the well-to-wake CO2 equivalent emissions. However, for commercial aviation the fuel cost and the resulting direct operating cost (inclusive of carbon tax exemption) are significant aspects which also needs to be accounted for identifying fuel manufacturing pathways for both liquid hydrogen and 100% synthetic paraffin kerosene, which are not considered in this work. The fossil-fuel based energy consumption in fuel manufacturing phase should be reduced by increasing the share of renewables in the energy mix and improving the energy efficiency of the fuel manufacturing process and supply chain, for making SAF and/or liquid hydrogen an environmentally and socially benign aviation fuels. This work will inform: (i) research and development investments aimed at increasing production capacities for identified fuel manufacturing processes; (ii) assessments of fuel costs; and (iii) the formulation of aviation policies. Lastly, the success of liquid hydrogen powered aviation requires appropriate airport infrastructure, aircraft design, air-traffic or operations management, safety, and fuel supply chain/manufacturing capacity and energy efficiency, to meet the required fuel demand, fuel cost and direct operating cost, and policy.

More information:

First author’s other research work can be found in [

6,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

26,

94,

95,

96,

97,

98,

99,

100,

101,

102,

103,

104,

105,

106,

107,

108,

109,

110,

111,

112,

113,

114,

115,

116,

117,

118].