Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Results

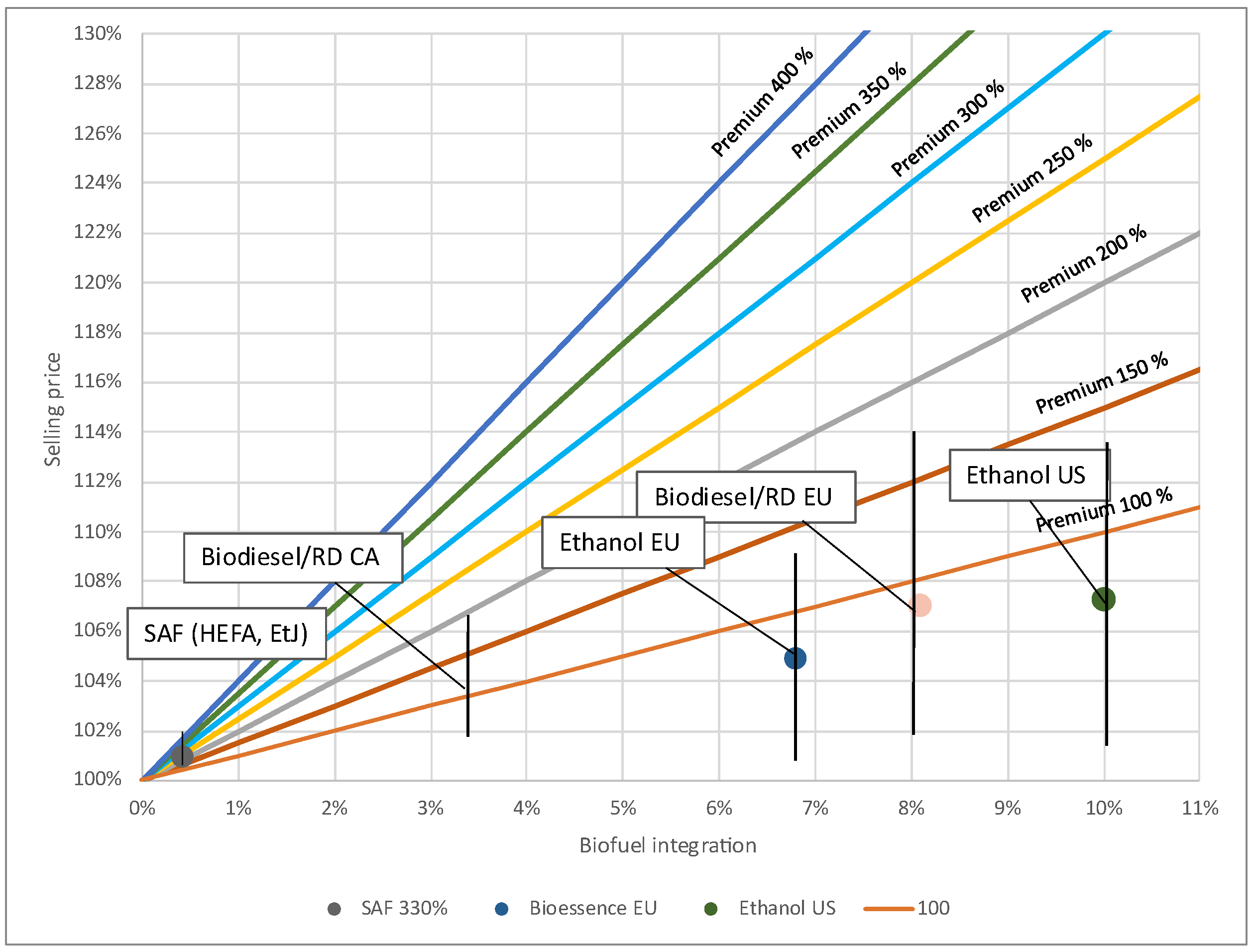

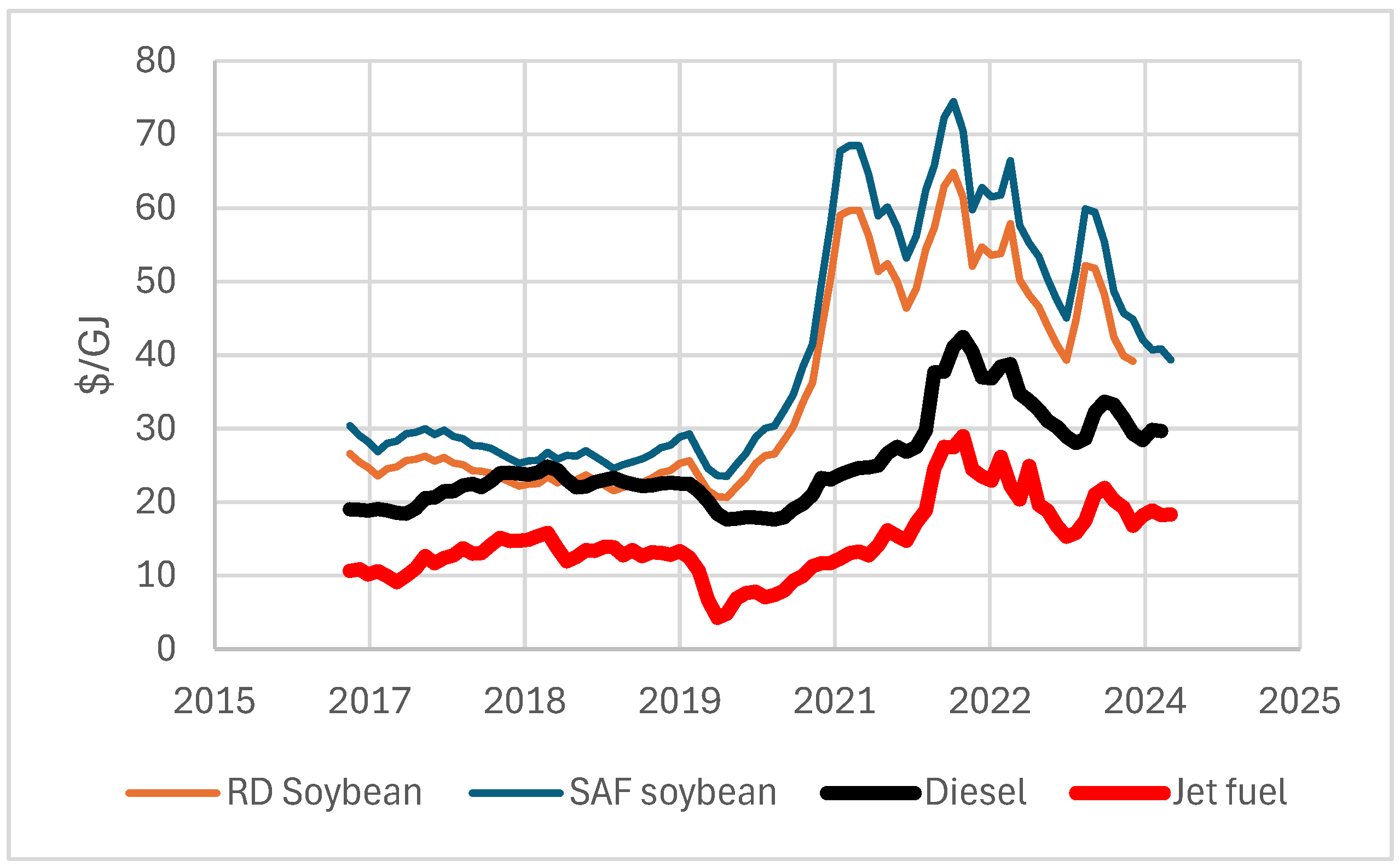

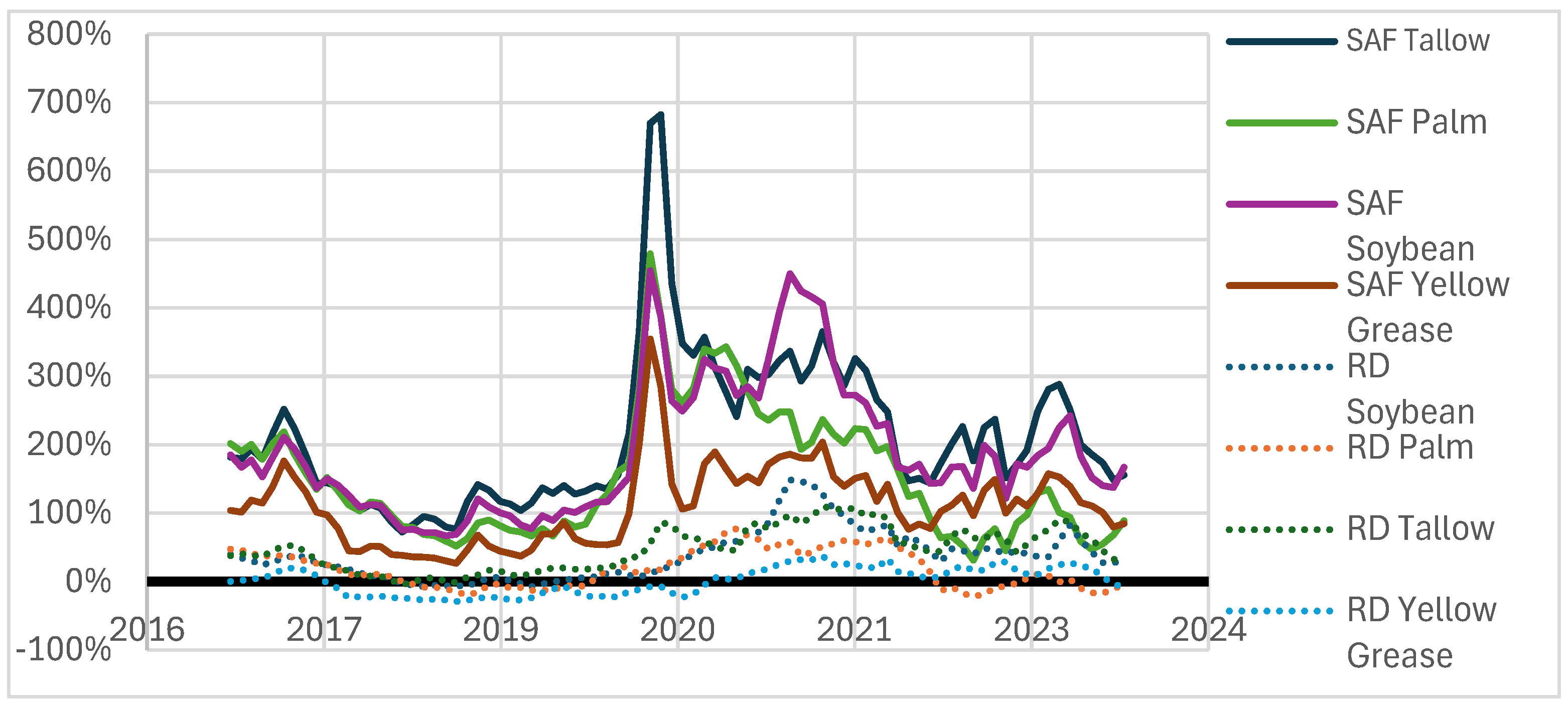

3.1. The HEFA-tJ Fuel Market Is Attractive Despite Prohibitive Production Costs

3.2. HEFA-Road Has Higher Yield and Selectivity than HEFA-tJ

3.3. Resource Costs for HEFA-tJ Are Much Higher than Conventional Jet and Diesel Fuel Costs, Implying Low Production Cost Reduction Potential

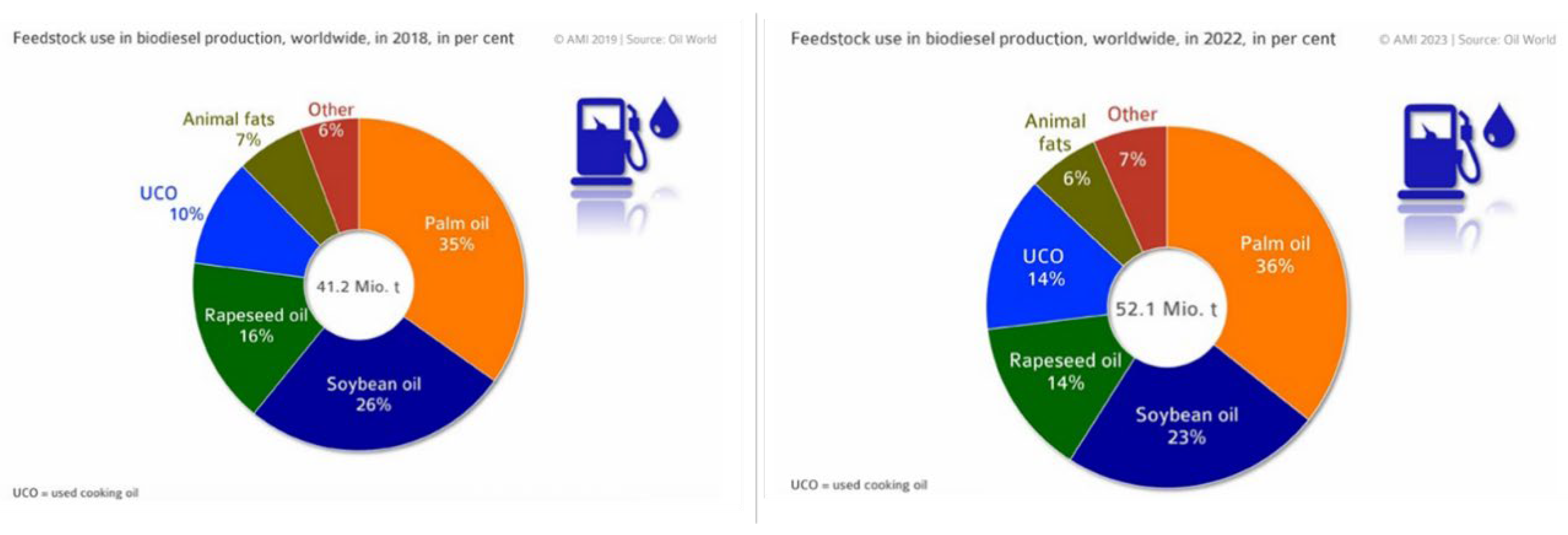

3.4. Used Cooking Oil (UCO) and Animal Fats (Tallow) Are the Only Resources with a Significant Commercial Deployment that Can Lead to More than 65% Reduction in Carbon Intensity Compared to Conventional Fuel

3.4.1. iLUC Heated Debates

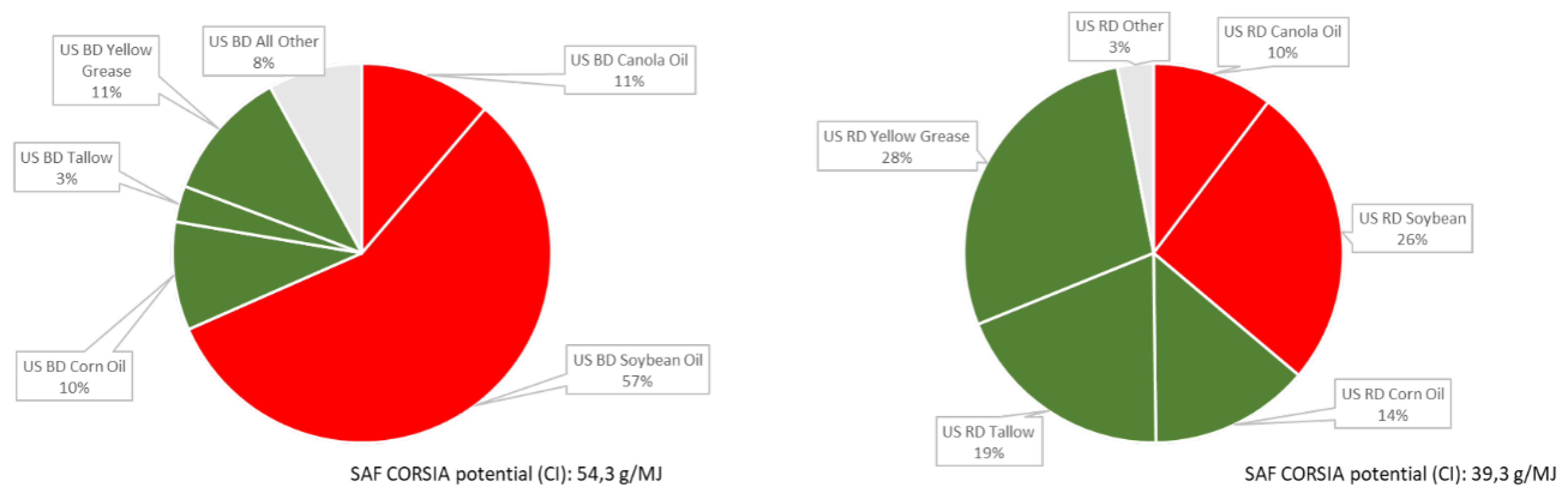

3.4.2. Market Share Importance in Carbon Intensity Evaluation

3.5. UCO and Tallow World Availability Cannot Cover Actual HEFA Road Usage

3.6. Other Resources Used in Commercial Deployments for the HEFA Pathway Have Mitigated Environmental Impacts

3.6.1. Reducing HEFA-tJ Pathway Carbon Intensity with Other Resources

3.6.2. Uncertainties About the Positive Environmental Impact of Animal Fat and Low LUC/iLUC Feedstocks

3.7. Considerable Efforts Are Being Deployed to Reduce Palm Oil’s Carbon Intensity

3.8. Shifting Production from HEFA-Road to HEFA-tJ Can Potentially Reduce the Environmental Benefits of Fuel Production From Vegetable Oils

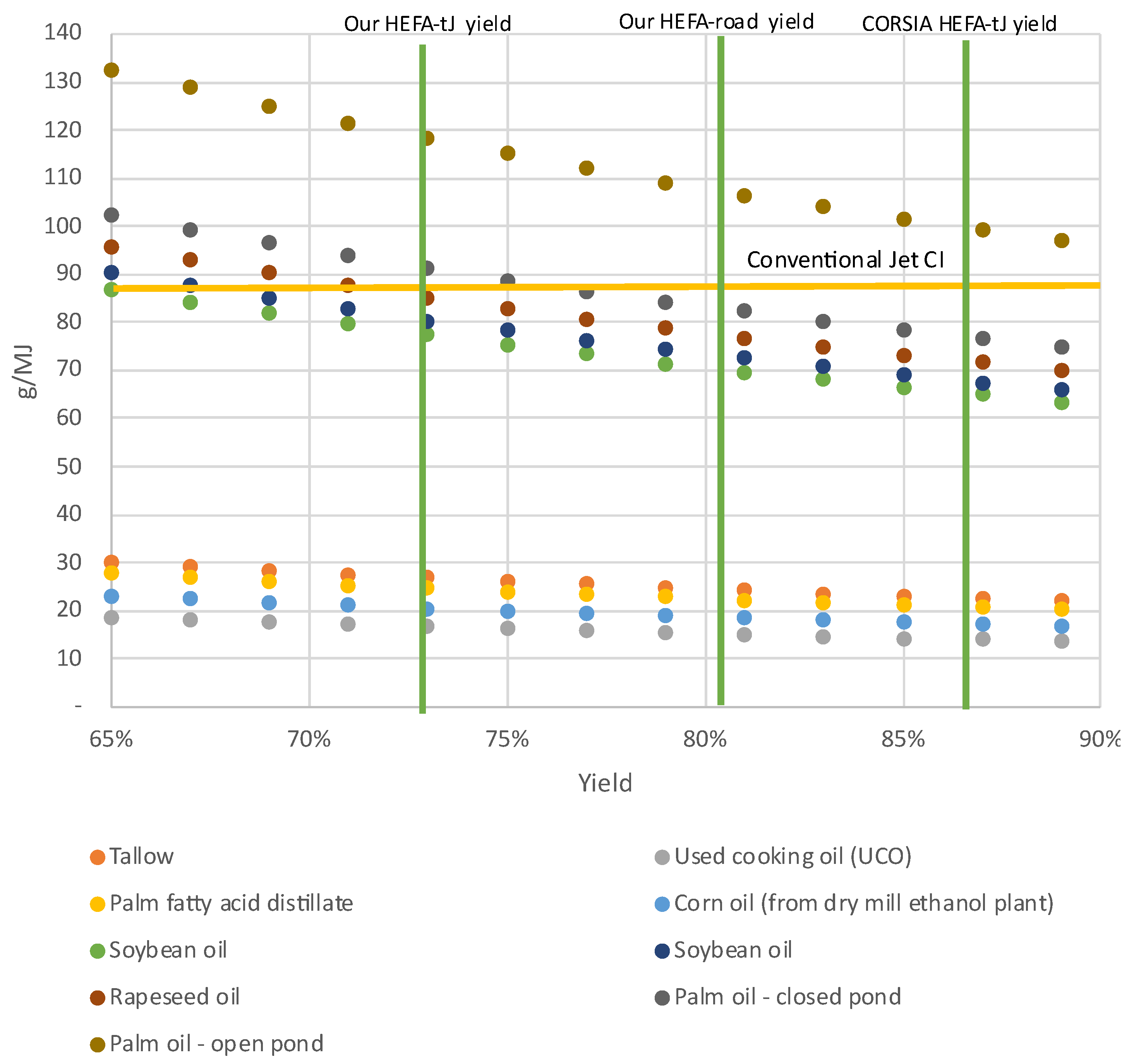

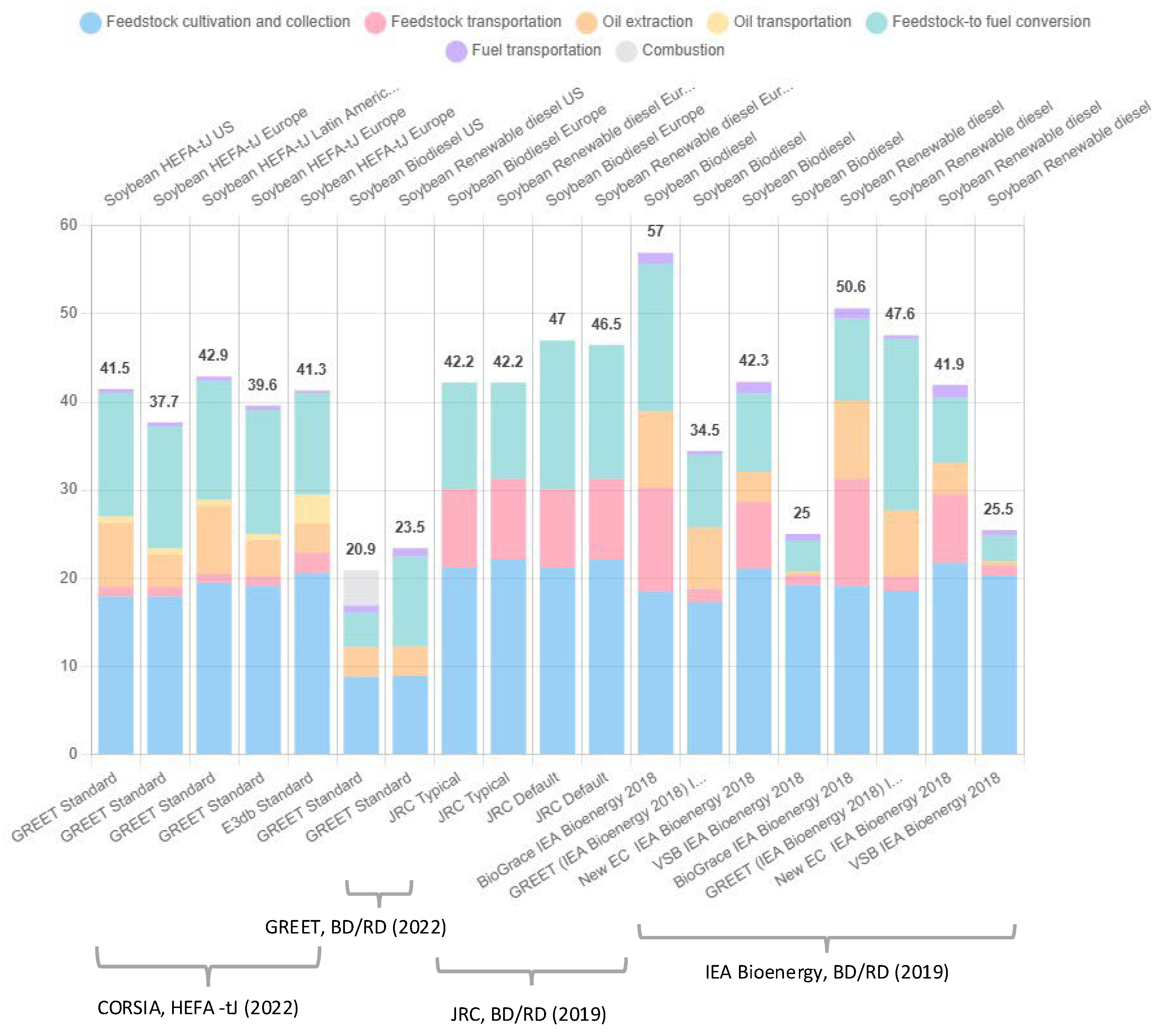

3.8.1. Yield Impacts on Carbon Intensity

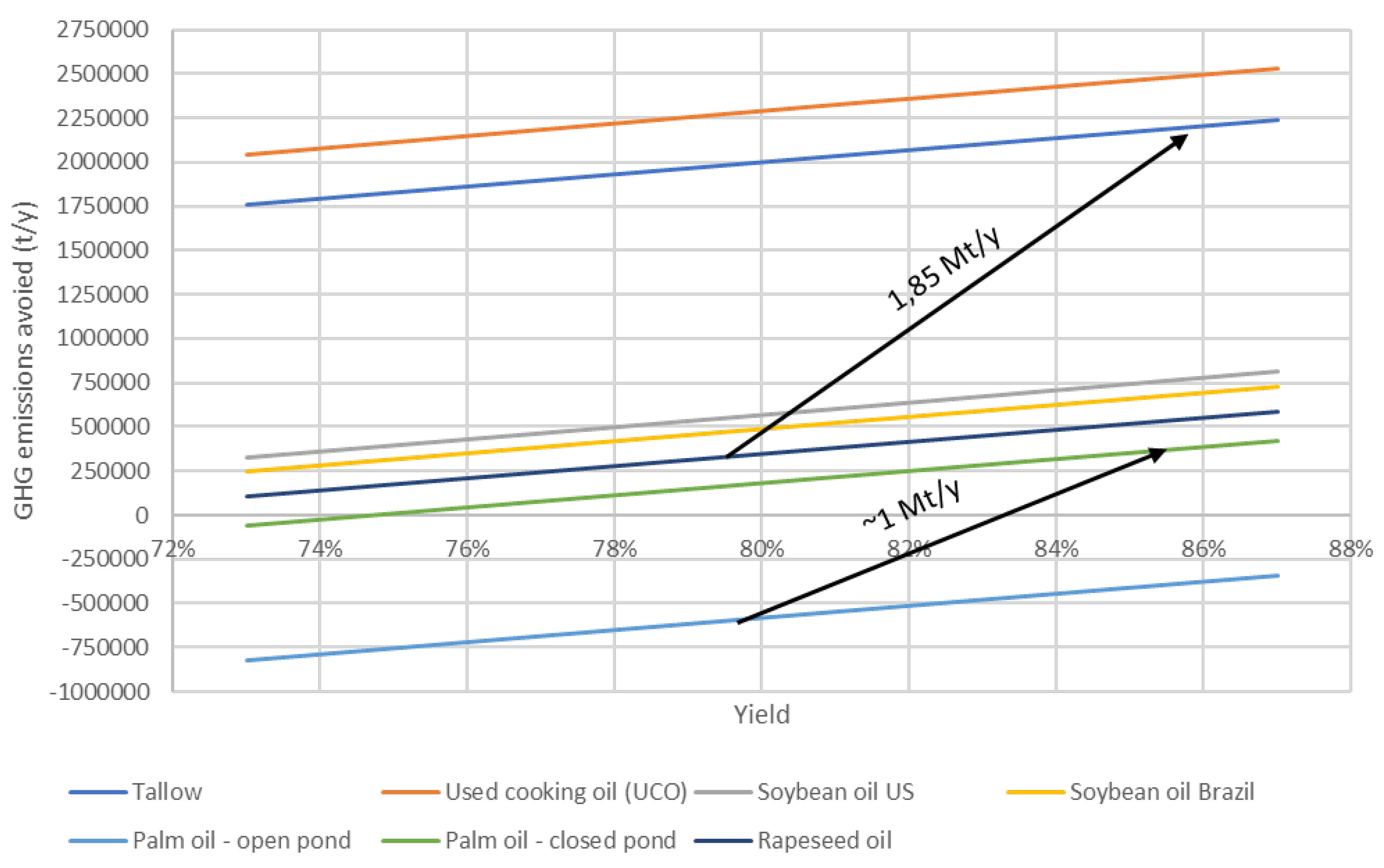

3.8.2. Yield Effects on GHG Reduction

3.9. Reducing Palm Oil Production’s Environmental Impact by Capturing Methane from Effluent Treatment Is a Less Capital-Intensive and More Efficient Way to Reduce Global GHG Emissions than Producing HEFA-tJ

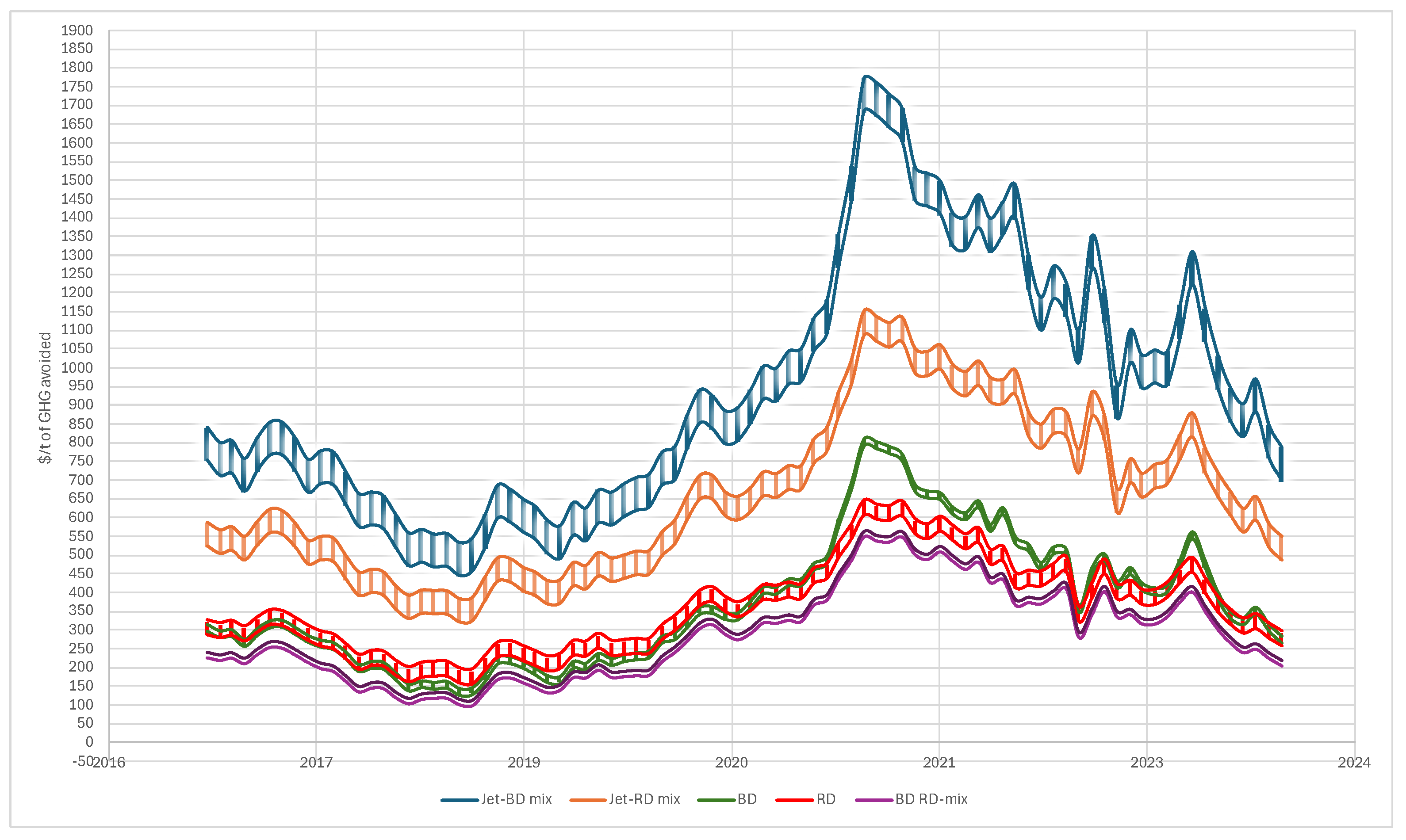

3.10. Social Costs of Reducing GHG Emissions with Vegetable Oil and Animal Fat Products Are Important

3.10.1. Economic Model for Social Cost Estimation

3.10.2. Carbon Intensity Model for GHG Reduction and Social Cost Estimation

3.10.3. Social Costs of the Different Pathways

4. Discussion: The Role of Different Actors in Maximizing the Climate Offsets of the SAF Production

4.1. Lawmakers and Aviation Industries

4.2. Takeaway for R&D and R&D Investors

4.3. Takeaway for LCA Developers

4.4. Takeaway for the Industry

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BD | Biodiesel (fatty acid methyl ester, FAME) |

| BETO | USDOE, Bioenergy Technology Office |

| CI | Carbon intensity |

| CORSIA | Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation |

| EIA | U.S. Energy Information Administration |

| HEFA-tJ | Hydrotreated ester and fatty acid pathway to jet |

| HEFA-road | Hydrotreated ester and fatty acid pathway to renewable diesel (RD) |

| FOG | Fats, oils and greases |

| IATA | International Air Transport Association |

| ILUC | Indirect land use changes |

| JRC | Joint Research Center |

| Mt | Million tonnes |

| NREL SOI | National Renewable Energy Laboratory State of Industry |

| PFAD | Palm fatty acid distillate |

| RD | Renewable diesel, also called HVO (hydrogenated vegetable oil) |

| SAF | Sustainable aviation fuels |

| TCI | Total Capital Investment |

| UCO | Used Cooking Oil |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

| USDOE | United States Department of Energy |

References

- Watson, M. J.; Machado, P. G.; da Silva, A. V.; Saltar, Y.; Ribeiro, C. O.; Nascimento, C. A. O.; Dowling, A. W. Sustainable Aviation Fuel Technologies, Costs, Emissions, Policies, and Markets: A Critical Review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 449, 141472. [CrossRef]

- Calderon, R., O.; Tao, L.; Abdullah, Z. Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) State-of-Industry Report: State of SAF Production Process; NREL, 2024. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy24osti/87802.pdf.

- Nigam, S.; Singer, D. Pathway to SAF—Europe Edition; 2024.

- BETO. SAF Grand Challenge Roadmap Flight Plan for Sustainable Aviation Fuel; 2022. https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2022-09/beto-saf-gc-roadmap-report-sept-2022.pdf.

- European Commission. REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on ensuring a level playing field for sustainable air transport, 2021.

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency. Current landscape and future of SAF industry | EASA Eco. https://www.easa.europa.eu/eco/eaer/topics/sustainable-aviation-fuels/current-landscape-future-saf-industry (accessed 2024-06-09).

- IATA. Developing Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF). https://www.iata.org/en/programs/sustainability/sustainable-aviation-fuels/ (accessed 2024-08-13).

- Neste. Rotterdam refinery | Neste. https://www.neste.com/about-neste/how-we-operate/production/rotterdam-refinery (accessed 2024-08-13).

- World Energy Paramount. Advanced Alternatives: World Energy Paramount Renewable Fuels Project, 2022. https://laedc.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/LAEDC_AlpineReport_FINAL_rvs-06.20.2022.pdf.

- ReFuelEU. “Ajustement à l’objectif 55”: accroître l’utilisation de carburants plus écologiques dans les secteurs aérien et maritime. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/fr/infographics/fit-for-55-refueleu-and-fueleu/ (accessed 2024-06-09).

- Calderon, R., O.; Tao, L.; Abdullah, Z.; Talmadge, M.; Milbrandt, A.; Smolinski, S.; Moriarty, K.; Bhatt, A.; Zhang, Y.; Ravi, V.; Skangos, C.; Davis, R.; Payne, C. Sustainable Aviation Fuel State-of-Industry Report: Hydroprocessed Esters and Fatty Acids Pathway, 2024.

- Bardon, P.; Massol, O. Decarbonizing Aviation with Sustainable Aviation Fuels: Myths and Realities of the Roadmaps to Net Zero by 2050. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2025, 211, 115279. [CrossRef]

- Braun, M.; Grimme, W.; Oesingmann, K. Pathway to Net Zero: Reviewing Sustainable Aviation Fuels, Environmental Impacts and Pricing. Journal of Air Transport Management 2024, 117, 102580. [CrossRef]

- Doliente, S. S.; Narayan, A.; Tapia, J. F. D.; Samsatli, N. J.; Zhao, Y.; Samsatli, S. Bio-Aviation Fuel: A Comprehensive Review and Analysis of the Supply Chain Components. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Liu, W.; Chen, X.; Yang, Q.; Li, J.; Chen, H. Renewable Bio-Jet Fuel Production for Aviation: A Review. Fuel 2019, 254, 115599. [CrossRef]

- Ng, K. S.; Farooq, D.; Yang, A. Global Biorenewable Development Strategies for Sustainable Aviation Fuel Production. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 150, 111502. [CrossRef]

- Perkins, J. Dozens of Ethanol Plants Remain Idle in Early 2021. Successful Farming. https://www.agriculture.com/news/business/dozens-of-ethanol-plants-idle-production-in-early-2021 (accessed 2025-02-12).

- CORSIA. CORSIA SUPPORTING DOCUMENT v5, CORSIA Eligible Fuels—Life Cycle Assessment Methodology; v5; 2022; p 203.

- Pearlson, M.; Wollersheim, C.; Hileman, J. A Techno-Economic Review of Hydroprocessed Renewable Esters and Fatty Acids for Jet Fuel Production. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining 2013, 7 (1), 89–96. [CrossRef]

- Zech, K. M.; Dietrich, S.; Reichmuth, M.; Weindorf, W.; Müller-Langer, F. Techno-Economic Assessment of a Renewable Bio-Jet-Fuel Production Using Power-to-Gas. Applied Energy 2018, 231, 997–1006. [CrossRef]

- Bardon, P.; Massol, O.; Thomas, A. Greening Aviation with Sustainable Aviation Fuels: Insights from Decarbonization Scenarios. Journal of Environmental Management 2025, 374, 123943. [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Humpe, A. Net-Zero Aviation: Time for a New Business Model? Journal of Air Transport Management 2023, 107, 102353. [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Humpe, A. Net-Zero Aviation: Transition Barriers and Radical Climate Policy Design Implications. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 912, 169107. [CrossRef]

- Dray, L.; Schäfer, A. W. Cost and Emissions Pathways towards Net-Zero Climate Impacts in Aviation. Nature Climate Change 2022, 12 (10), 956–962. [CrossRef]

- Bioenergy Technology Office. State of Technology, 2020; DOE, 2021; p 168.

- Hamberg, K.; Leslie, M.; Walter, C.; Stratton, T.; Markham, D.; Tang, M.; Weatherbed, L. Scaling Solutions, Accelerating the Commercialization of Made-in-Canada Clean Technology, 2023.

- Dyk, S. V.; Saddler, J. Progress in the Commercialization of Biojet / Sustainable Aviation Fuels: Technologies, Potential and Challenges | Bioenergy; IEA Bioenergy Task 39, 2021. https://www.ieabioenergy.com/blog/publications/progress-in-the-commercialization-of-biojet-sustainable-aviation-fuels-technologies-potential-and-challenges/ (accessed 2024-04-25).

- IEA. Ethanol and gasoline prices 2019 to April 2022—Charts—Data & Statistics. IEA. https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/ethanol-and-gasoline-prices-2019-to-april-2022 (accessed 2024-04-27).

- EIA. U.S. Energy Information Administration—EIA—Independent Statistics and Analysis. https://www.eia.gov/state/search/?sid=AL#?1=682&2=182&r=false (accessed 2025-02-01).

- Mauler, L.; Dahrendorf, L.; Duffner, F.; Winter, M.; Leker, J. Cost-Effective Technology Choice in a Decarbonized and Diversified Long-Haul Truck Transportation Sector: A U.S. Case Study. Journal of Energy Storage 2022, 46, 103891. [CrossRef]

- Jadun, Paige, Colin McMillan, Daniel Steinberg, Matteo Muratori, Laura Vimmerstedt, and Trieu Mai. 2017. Electrification Futures Study: End-Use Electric Technology Cost and Performance Projections through 2050. Golden, CO: National Renewable Energy Laboratory. NREL/TP-6A20-70485. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy18osti/70485.pdf.

- Ledna, C.; Muratori, M.; Yip, A.; Jadun, P.; Hoehne, C.; Podkaminer, K. Assessing Total Cost of Driving Competitiveness of Zero-Emission Trucks. iScience 2024, 27 (4). [CrossRef]

- Link, S.; Stephan, A.; Speth, D.; Plötz, P. Rapidly Declining Costs of Truck Batteries and Fuel Cells Enable Large-Scale Road Freight Electrification. Nat Energy 2024, 9 (8), 1032–1039. [CrossRef]

- Noll, B.; del Val, S.; Schmidt, T. S.; Steffen, B. Analyzing the Competitiveness of Low-Carbon Drive-Technologies in Road-Freight: A Total Cost of Ownership Analysis in Europe. Applied Energy 2022, 306, 118079. [CrossRef]

- Argonne National Laboratory. Hydrogen Delivery Infrastructure Analysis. https://hdsam.es.anl.gov/index.php (accessed 2025-02-17).

- Elgowainy, A. Economic and Environmental Perspectives of Hydrogen Infrastructure Deployment Options, 2019.

- HDSAM. Hydrogen Delivery Scenario Analysis Model. https://hdsam.es.anl.gov/index.php?content=hdsam (accessed 2025-02-19).

- Connelly, E., Penev, M., Elgowainy, A., Hunter, C. Current Status of Hydrogen Liquefaction Costs. DOE Hydrogen and Fuel Cells Program Record 19001. https://www.hydrogen.energy.gov/docs/hydrogenprogramlibraries/pdfs/19001_hydrogen_liquefaction_costs.pdf?sfvrsn=378c2204_1.

- Ragon, P.-L.; Kelly, S.; Egerstrom, N.; Brito, J.; Sharpe, B.; Allcock, C.; Minjares, R.; Rodriguez, F. Near-term infrastructure deployment to support zero-emission medium- and heavy-duty vehicles in the United States. International Council on Clean Transportation. https://theicct.org/publication/infrastructure-deployment-mhdv-may23/ (accessed 2025-02-19).

- Burnham, A.; Gohlke, D.; Rush, L.; Stephens, T.; Zhou, Y.; Delucchi, M. A.; Birky, A.; Hunter, C.; Lin, Z.; Ou, S.; Xie, F.; Proctor, C.; Wiryadinata, S.; Liu, N.; Boloor, M. Comprehensive Total Cost of Ownership Quantification for Vehicles with Different Size Classes and Powertrains; ANL/ESD-21/4; Argonne National Lab. (ANL), Argonne, IL (United States), 2021. [CrossRef]

- Aryanpur, V.; Rogan, F. Decarbonising Road Freight Transport: The Role of Zero-Emission Trucks and Intangible Costs. Sci Rep 2024, 14 (1), 2113. [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Milbrandt, A.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.-C. Techno-Economic and Resource Analysis of Hydroprocessed Renewable Jet Fuel. Biotechnology for Biofuels 2017, 10 (1), 261. [CrossRef]

- Marker, T. L. Opportunities for Biorenewables in Oil Refineries. 2005. [CrossRef]

- Cross, D. SHELL’S POWERING PROGRESS STRATEGY, 2022. https://www.gti.energy/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/01-tcbiomass2022-Keynote-Presentation-Darren-Cross.pdf.

- Digital Refining. Neste Oil adds NExBTL renewable naphtha suitable for producing bioplastics. https://www.digitalrefining.com/news/1001438/neste-oil-adds-nexbtl-renewable-naphtha-suitable-for-producing-bioplastics (accessed 2024-04-09).

- Oki, N. Japan’s Mitsui Chemicals adds new bio-petchem products | Latest Market News. https://www.argusmedia.com/en/news-and-insights/latest-market-news/2508701-japan-s-mitsui-chemicals-adds-new-bio-petchem-products (accessed 2024-04-09).

- Chang-Won, L. SK Geo Centric delivers first shipment of renewable benzene to Covestro. Aju Press. https://www.ajupress.com/view/20220620135800806 (accessed 2024-04-09).

- Kotrba, R. Total converting Grandpuits refinery to produce renewable diesel, SAF, bioplastics, solar power. BiobasedDieselDaily. https://www.biobased-diesel.com/post/total-investing-500-million-euros-converting-grandpuits-refinery-to-produce-hvo-saf-bioplastics (accessed 2024-04-09).

- Honeywell. Honeywell Introduces New Technology To Produce Key Feedstock For Plastics. https://www.honeywell.com/us/en/press/2022/02/honeywell-introduces-new-technology-to-produce-key-feedstock-for-plastics (accessed 2024-04-09).

- Zhao, Z., Jiang, J., Wang, F. An economic analysis of twenty light olefin production pathways, Journal of Energy Chemistry, Volume 56, 2021, Pages 193-202, ISSN 2095-4956. [CrossRef]

- Neste. Borealis producing certified renewable polypropylene from Neste’s renewable propane at own facilities in Belgium. https://www.neste.com/news/borealis-producing-certified-renewable-polypropylene-from-neste-s-renewable-propane-at-own-facilities-in-belgium (accessed 2024-04-09).

- Neste. Neste delivers first batch of 100% renewable propane to European market. https://www.neste.com/news/neste-delivers-first-batch-of-100-renewable-propane-to-european-market (accessed 2024-04-09).

- Quantum Commodity Intelligence. https://www.qcintel.com/ (accessed 2024-04-25).

- EIA. U.S. Gulf Coast Kerosene-Type Jet Fuel Spot Price FOB (Dollars per Gallon). https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=PET&s=EER_EPJK_PF4_RGC_DPG&f=M (accessed 2024-08-12).

- USDA. US Bioenergy Statistics, 2024. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/u-s-bioenergy-statistics/.

- Hofstrand, D. Tracking Biodiesel Profitability | Ag Decision Maker, 2024. https://www.extension.iastate.edu/agdm/energy/html/d1-15.html (accessed 2024-08-05).

- Carlson, N. A.; Talmadge, M. S.; Singh, A.; Tao, L.; Davis, R. Economic Impact and Risk Analysis of Integrating Sustainable Aviation Fuels into Refineries. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- DOE Alternative Fuels Data Center. Alternative Fuels Data Center: Fuel Properties Comparison. https://afdc.energy.gov/fuels/properties (accessed 2024-08-12).

- Prussi, M.; Lee, U.; Wang, M.; Malina, R.; Valin, H.; Taheripour, F.; Velarde, C.; Staples, M. D.; Lonza, L.; Hileman, J. I. CORSIA: The First Internationally Adopted Approach to Calculate Life-Cycle GHG Emissions for Aviation Fuels. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 150, 111398. [CrossRef]

- Unnasch, S. Review of EPA Workshop on Biofuel Greenhouse Gas Modeling, 2022.

- Taheripour, F.; Mueller, S.; Emery, I.; Karami, O.; Sajedinia, E.; Zhuang, Q.; Wang, M. Biofuels Induced Land Use Change Emissions: The Role of Implemented Land Use Emission Factors. Sustainability 2024, 16 (7), 2729. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Michael. « Opportunities for Lowering GHG Emissions of Corn Ethanol », 2022. https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2022-03/02-beto-gen-1-wksp-wang.pdf.

- NAIDU, L.; MOORTHY, R.; HUDA, M. I. M. THE ENVIRONMENTAL AND HEALTH SUSTAINABILITY CHALLENGES OF MALAYSIAN PALM OIL IN THE EUROPEAN UNION—Journal of Oil Palm Research. http://jopr.mpob.gov.my/the-environmental-and-health-sustainability-challenges-of-malaysian-palm-oil-in-the-european-union/ (accessed 2024-07-27).

- Schroeder, K. Waiting for Takeoff | Ethanol Producer Magazine. https://ethanolproducer.com/articles/waiting-for-takeoff (accessed 2024-08-05).

- O’Malley, J.; Pavlenko, N. Drawbacks of Adopting a “Similar” LCA Methodology for U.S. Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF). https://theicct.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/ID-16-Briefing-letter-v3.pdf.

- IEA BioEnergy. IEA Bioenergy Webinar—Understanding Indirect Land-Use Change (ILUC) and Why Reality is a Special Case—Bioenergy. https://www.ieabioenergy.com/blog/publications/iea-bioenergy-webinar-understanding-indirect-land-use-change-iLUC-and-why-reality-is-a-special-case/ (accessed 2024-08-13).

- UFOP. UFOP Report On Global Market Supply 2019-2020, 2020 . https://www.ufop.de/files/1115/7953/1340/WEB_UFOP_Global_Supply_Report_A5_EN_19_20.pdf.

- UFOP. UFOP Report On Global Market Supply 2023-2024, 2024 https://www.ufop.de/files/8217/0548/9837/UFOP-2116_Report_Global_Market_Supply_A5_EN_23_24_160124.pdf.

- Xu, H.; Ou, L.; Li, Y.; Hawkins, T. R.; Wang, M. Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Biodiesel and Renewable Diesel Production in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56 (12), 7512–7521. [CrossRef]

- Gerveni, M.; Hubbs, T.; Irving, S. FAME Biodiesel, Renewable Diesel and Biomass-Based Diesel Feedstock Volume Estimates, 2024.

- Lange, T. Presentation_Thorsten-Lange_2021-04-14_Neste-SAF.Pdf, 2021. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/232175/Presentation_Thorsten-Lange_2021-04-14_Neste-SAF.pdf (accessed 2022-11-03).

- World Economic Forum. Clean Skies for Tomorrow: Sustainable Aviation Fuels as a Pathway to Net-Zero Aviation; 2020. https://www.weforum.org/publications/clean-skies-for-tomorrow-sustainable-aviation-fuels-as-a-pathway-to-net-zero-aviation/ (accessed 2024-04-26).

- Schmidt, J.; De Rosa, M. Certified Palm Oil Reduces Greenhouse Gas Emissions Compared to Non-Certified. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 277, 124045. [CrossRef]

- Alcock, T. D.; Salt, D. E.; Wilson, P.; Ramsden, S. J. More Sustainable Vegetable Oil: Balancing Productivity with Carbon Storage Opportunities. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 829, 154539. [CrossRef]

- Yeoh, M. L.; Goh, C. S. Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil Production from Palm Oil Mill Effluents: Status, Opportunities and Challenges. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining 2022, 16 (5), 1153–1158. [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Roser, M. Palm Oil. Our World in Data 2024.

- Neste. Neste sets ambitious PFAD targets : 100 % traceable in 2020 https://www.neste.com/news/neste-sets-ambitious-pfad-targets-100-traceable-in-2020 (accessed 2024-08-13).

- Taheripour, F.; Sajedinia, E.; Karami, O. Oilseed Cover Crops for Sustainable Aviation Fuels Production and Reduction in Greenhouse Gas Emissions Through Land Use Savings. Frontiers in Energy Research 2022, 9.

- Goldman, E., M.J. Weisse, N. Harris, and M. Schneider. 2020. “Estimating the Role of Seven Commodities in Agriculture-Linked Deforestation: Oil Palm, Soy, Cattle, Wood Fiber, Cocoa, Coffee, and Rubber.” Technical Note. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. Available online at: wri.org/publication/estimating-the-role-of-sevencommodities-in-agriculture-linked-deforestation.

- Trase. Brazil beef—Supply chain—Explore the data—Trase. trase.earth. https://trase.earth/explore/supply-chain/brazil/beef (accessed 2024-10-14).

- Steinfeld, Henning, Pierre Gerber, T. Wassenaar, V. Castel, Mauricio Rosales, et C. de Haan. « Livestock’s long shadow », 2006. https://www.fao.org/4/a0701e/a0701e00.htm.

- Freitas, G.; Veloso, T.; Chipman, K. US Edged Out by Brazil Beef Fat Destined for Biofuels. Energy Connects. (accessed 2024-10-03).

- Gaveau, D. L. A.; Locatelli, B.; Salim, M. A.; Husnayaen; Manurung, T.; Descals, A.; Angelsen, A.; Meijaard, E.; Sheil, D. Slowing Deforestation in Indonesia Follows Declining Oil Palm Expansion and Lower Oil Prices. PLOS ONE 2022, 17 (3), e0266178. [CrossRef]

- RSPO. Impact Update 2023, RSPO; 2023. https://rspo.org/wp-content/uploads/Impact-Update-2023_.pdf.

- Loh. Biogas Capturing Facilities in Palm Oil Mills: Current Status and Way Forward—PALM OIL ENGINEERING BULLETIN. http://poeb.mpob.gov.my/biogas-capturing-facilities-in-palm-oil-mills-current-status-and-way-forward/ (accessed 2024-03-26).

- Environment Protection Department (EPD), et Sabah. « GUIDELINE ON WASTE MANAGEMENT(EFFLUENT AND SOLID WASTES) FOR PALM OIL MILLS IN SABAH », 2022.

- Lee, U.; Kwon, H.; Wu, M.; Wang, M. Retrospective Analysis of the U.S. Corn Ethanol Industry for 2005–2019: Implications for Greenhouse Gas Emission Reductions. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining 2021, 15 (5), 1318–1331. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R.; Padella, M.; Giuntoli, J.; Koeble, R.; O’, C. A. P.; Bulgheroni, C.; Marelli, L. Definition of input data to assess GHG default emissions from biofuels in EU legislation: Version 1c—July 2017. JRC Publications Repository. [CrossRef]

- IEA BioEnergy. Comparison of Biofuel Life Cycle Analysis Tools—Phase 2, Part 1: FAME and HVO/HEFA; 2018. https://www.ieabioenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Task-39-CTBE-biofuels-LCA-comparison-Final-Report-Phase-2-Part-1-February-11-2019.pdf.

- Staples, M. D.; Malina, R.; Barrett, S. R. H. The Limits of Bioenergy for Mitigating Global Life-Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Fossil Fuels. Nat Energy 2017, 2 (2), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Staples, M. D.; Malina, R.; Suresh, P.; Hileman, J. I.; Barrett, S. R. H. Aviation CO2 Emissions Reductions from the Use of Alternative Jet Fuels. Energy Policy 2018, 114, 342–354. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, C. C. N.; Angelkorte, G.; Rochedo, P. R. R.; Szklo, A. The Role of Biomaterials for the Energy Transition from the Lens of a National Integrated Assessment Model. Climatic Change 2021, 167 (3), 57. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, C. C. N.; Zotin, M. Z.; Rochedo, P. R. R.; Szklo, A. Achieving Negative Emissions in Plastics Life Cycles through the Conversion of Biomass Feedstock. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining 2021, 15 (2), 430–453. [CrossRef]

- Air Liquide, 2022. Profits without subsidies ? https://engineering.airliquide.com/sites/engineering/files/2022-07/air_liquide_biodiesel_final.pdf (accessed 2024-10-12).

- Dutta, Abhijit, Asad Sahir, et Eric Tan. « Process Design and Economics for the Conversion of Lignocellulosic Biomass to Hydrocarbon Fuels: Thermochemical Research Pathways with In Situ and Ex Situ Upgrading of Fast Pyrolysis Vapors », s. d., 275.

- Swanson, R. M., A. Platon, J. A. Satrio, R. C. Brown, et D. D. Hsu. « Techno-Economic Analysis of Biofuels Production Based on Gasification », 1 novembre 2010. [CrossRef]

- Irwin, Scott. « Biodiesel Prices and Profits…Again ». Farmdoc Daily 14, no 49 (11 mars 2024). https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2024/03/biodiesel-prices-and-profits-again.html.

- EA Energy. Will more wind and solar PV capacity lead to more generation curtailment?—Renewable Energy Market Update—June 2023—Analysis. IEA. https://www.iea.org/reports/renewable-energy-market-update-june-2023/will-more-wind-and-solar-pv-capacity-lead-to-more-generation-curtailment (accessed 2024-08-05).

- Ritchie, H., Rosado, P. and Roser, M. (2023)—“Energy”. Data adapted from Ember, Energy Institute. “Data Page: Carbon intensity of electricity generation”, part of the following publication: Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/carbon-intensity-electricity [online resource].

| Pearlson et al., 2013 | Zech et al., 2018 | |||

| HEFA-tJ | HEFA-road | HEFA-tJ | HEFA-road | |

| Jet fuels | 49.4 | 12.8 | 45.4 | 12 |

| Diesel fuels | 23.3 | 68.1 | 8 | 66 |

| Naphtha | 7 | 1.8 | 27 | 4 |

| Refinery gas | 10.2 | 5.8 | 7.2 | 3 |

| Yield without conversion losses | 88 | 90 | 86 | 88 |

| Yield with conversion losses | 79 | 86 | 73 | 84 |

| Region | Feedstock | Core LCA Value | iLUC LCA | Total (g/MJ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global | Tallow | 49.4 | 0 | 22.5 |

| Global | Used cooking oil | 23.3 | 13.9 | |

| Global | Palm fatty Acid Distillate | 7 | 20.7 | |

| Global | Corn oil | 10.2 | 17.2 | |

| USA | Soybean oil | 40.4 | 24.5 | 64.9 |

| Brazil | Soybean oil | 40.4 | 27 | 67.4 |

| EU | Rapeseed oil | 47.4 | 24.1 | 71.5 |

| Malaysia and Indonesia | Palm oil—closed pond | 37.4 | 39.1 | 76.5 |

| Malaysia and Indonesia | Palm oil—open pond | 60 | 39.1 | 99.1 |

| Reference | Plant type | Data type | Capacity kt/y feedstock | TCI ($/t feedstock) | TCI (2024) |

| Zech. H. et al., 2018 | HEFA-tJ | Literature | 500 260 116-378 1470 |

396 | 550 |

| Tao. L, et al., 2017 | HEFA-tJ | Literature | 1346 | 1 869 | |

| Pearlson, M. et al., 2013 | HEFA-tJ | Literature | 293-619 | 440-937 | |

| Neste | HEFA-tJ | Announcement | 1337 | ||

| World Energy Paramount (CA) | HEFA-tJ | Announcement | 1500 | 1337 | |

| TotalEnergy Grandpuits | HEFA-tJ | Announcement | 470 | ~1168 | |

| Holstrand, D., 2024 | BD | TEA | 106 | 493 | |

| AirLiquide 2022 | BD | Announcement | 50-350 | 315-475 | |

| Our estimates | HEFA-tJ | No SMR included | >1000 | 1200-1600 | |

| Our estimates | RD | No SMR included | 700 | 1080-1440 | |

| Our estimates | BD | 110 | 500-650 |

| Simplified economic model hypothesis | ||

| Study period (SP) | 15 | |

| Depreciation | TCI/SP | |

| RI | 7% | %TCI |

| Taxes | 2% | %TCI |

| Maintenance | 5% | %TCI |

| Resource cost hypotheses (by ton of feedstock) | ||

| Methanol cost | 441 | $/t |

| NG cost | 335 | $/t |

| H2 cost | 2000 | $/t |

| Electricity cost | 0.08 | $/kWh |

| Resource usage hypothesis for different pathways (by ton of feedstock) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| BD | Methanol | 105 | kg/t |

| NG | 46 | kg/t | |

| Electricity | 179 | kWh/t | |

| RD | H2 | 29,8 | kg/t |

| Electricity | 66 | kWh/t | |

| HEFA-tJ | H2 | 35.7 | kg/t |

| Electricity | 66 | kWh/t | |

| CI g/MJ | CI reduction | MJ/kg fuel | g/kg of GHG avoided by feedstock | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEFA-tJ BD mix | 54.29 | 39 % | 40.5 | 1 111 |

| HEFA-tJ RD mix | 38.23 | 57 % | 40.5 | 1 624 |

| BD mix | 43.31 | 52 % | 37.37 | 1 725 |

| RD mix | 31.12 | 66 % | 43.2 | 2 236 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).