1. Introduction

Lipids are fundamental organic molecules that constitute the backbone of neural cell membranes. They not only provide cell membranes with suitable environment, fluidity, and ion permeability,

but also play crucial roles in signal transduction processes and regulation of energy metabolism [

1]

. Among various lipids, phospholipids and sphingolipids contribute to the lipid asymmetry, whereas cholesterol and sphingolipids form lipid microdomains or lipid rafts. Lipid rafts float within the membrane, and certain groups of proteins unite within these rafts. A large number of signaling molecules are concentrated within rafts, which function as signaling centers capable of facilitating efficient and specific signal transduction pathways [

2]. Metabolism of lipids not only affects many cellular processes critical for maintaining normal neural cell function and homeostasis, but can also act as energy storage depot (triglycerides). Fatty acids are essential components of phospholipids and sphingolipids. They also serve as an important energy source through mitochondria-mediated beta-oxidation and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) [

3]. In addition, they may also major determinants of physicochemical properties of membrane and modulators of cellular signaling pathways [

3,

4]. Collective evidence suggests that intricate interactions among phospholipids, sphingolipids, cholesterol and proteins provide neural membranes with delicate, dynamic, and stable shape responsible for numerous cell membrane activities. Low levels of phospholipid-, sphingolipid-, and cholesterol-derived lipid metabolites are necessary for normal cellular functions such as inflammation, gene expression, growth arrest, differentiation, and adhesion. However, high levels of phospholipid-, sphingolipid-, and cholesterol-derived lipid metabolites may cause induction of inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis. Among these processes, inflammation is modulated not only by arachidonic acid (ARA, 20:4n-6) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3)-derived metabolites [

5,

6], but also by cross-cross-talk among phospholipid, sphingolipid and cholesterol-derived metabolites. The purpose of this review article is to describe the proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects of lipid metabolites to a broader audience with the hope that this discussion would jumpstart more studies on cross-talk among lipid metabolites leading to modulation of inflammation and induction of lipo-toxicity.

2. Inflammation

Inflammation is a protective mechanism, which is characterized by the activation of immune (neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes) and non-immune cells at the injury or infection site. Onset of inflammation results in restoration of homeostasis in body systems after injuries or infections [

7,

8]. The main generators of inflammation in the visceral tissues are macrophages and infiltrating immune cells. In the brain and spinal cord, inflammation is mediated by the mild and short-term activation of microglia and astrocytes. Mild and short-term activation of microglia and astrocytes usually produce neuroprotective effects and ameliorates early symptoms of neurodegeneration. Mild and short-term activation of microglia and astrocytes promote the release of low levels of cytokines, which help in maintaining synaptic plasticity, modulating neuronal excitability, and stimulating toll-like receptors (TLRs), a family of pattern recognition receptors that recognize microbial pathogens and respond by activating the innate immune system. These processes support neurogenesis and neurite outgrowth. In contrast, long-term activation of microglia and astroglia contribute to the overexpression of cytokines leading to neurodegeneration. Long-term activation of microglia and astroglia also results in marked alterations in the regulation of p53 protein and transcription factor NF-κB. These processes are crucial for shifting the regenerative effects into detrimental effects during inflammatory reactions. At the molecular level, the long-term inflammatory reaction is characterized by the release of prostaglandins (PGs), leukotrienes (LTs), thromboxane (TX), and nitric oxide (NO) by resident cells in the injured/infected tissue (i.e., tissue macrophages, dendritic cells, lymphocytes, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and mast cells). This leads to a noticeable increase in cerebral blood flow and accumulation of circulating leukocytes [

9] at the injury or infection site. Additionally, increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 (IL-1) and interleukin-6 (IL-6)) secreted from activated immune cells enhance the vascular permeability of leukocytes through raising the levels of leukocyte adhesion molecules on endothelial cells [

10,

11]. It is reported that prolonged presence of inflammation at the injury site may lead to serious problems, including impaired proteolysis, apoptosis, and epigenetic modifications [

12,

13]. The current knowledge of inflammatory signaling has been gained not only from studying members of the IL-1 and TNF receptor families, but also from the Toll-like microbial pattern recognition receptors (TLRs) [

10,

13] (

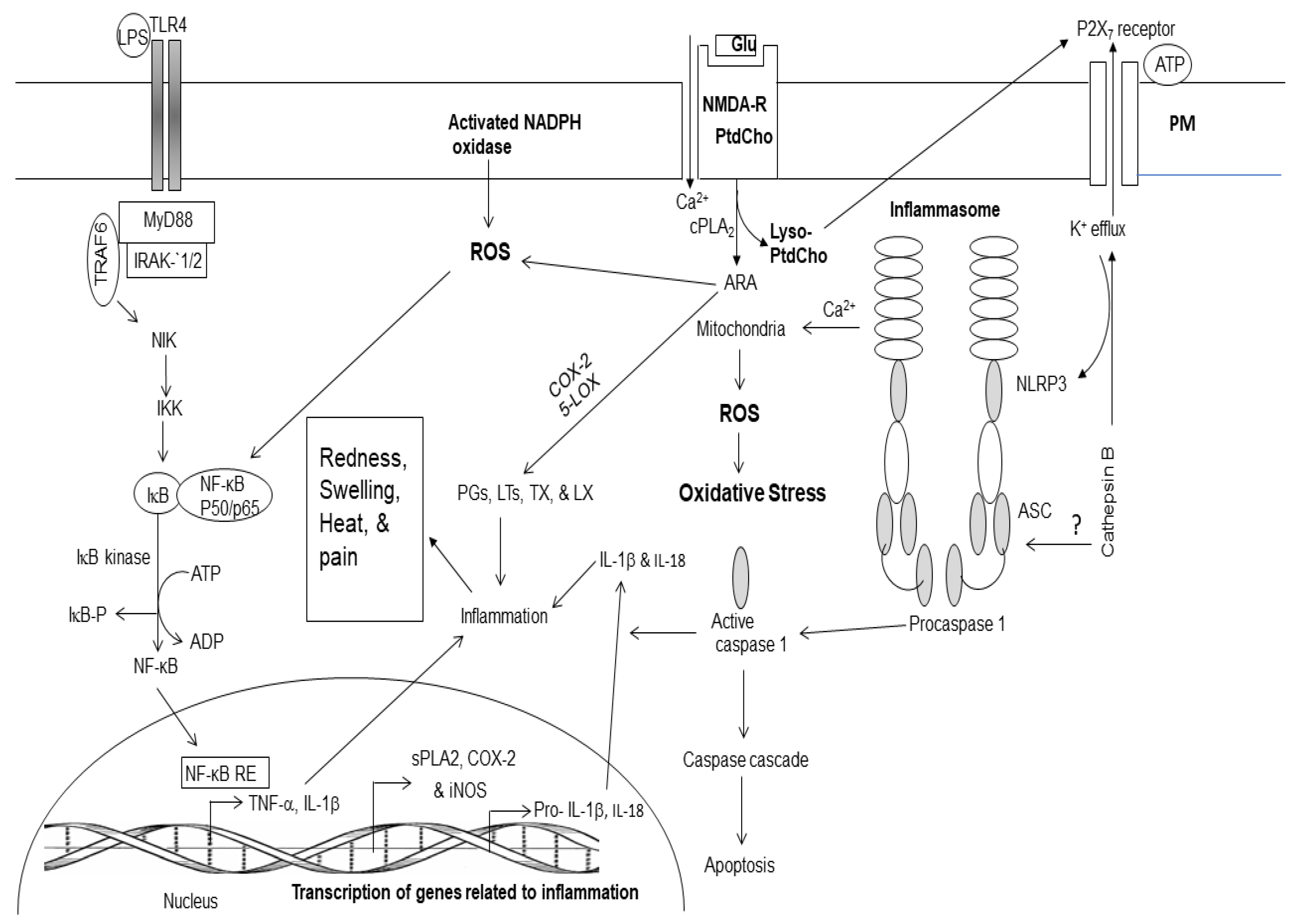

Figure 1). TLRs are ubiquitously expressed in macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells (DCs), natural killer (NK) cells, mast cells, eosinophils, and basophils. These cells are instrumental in mounting innate immune responses against invading pathogens and tissue injury. In the presence of high levels of inflammatory metabolites (PGs, LTs, and TX) at the injury or infection site is associated with the onset of inflammation (redness, swelling, heat, and pain) and loss of cell function.

Detailed investigations have indicated that the inflammation is also supported by oligomeric protein complexes known as inflammasomes (

Figure 1) [

14]. Inflammasomes reside in cytoplasm and act as platforms for the induction of inflammatory signaling. Inflammasomes are made up of several proteins, including NLRP3, NLRC4, AIM2 and NLRP6. Activation of the inflammasome during infection or injury results in a neuroprotective or detrimental effects in the brain. Thus, interactions of NLRP3 inflammasome with mitochondria in the presence of Ca

2+ facilitates the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS). It is not known whether interactions between NLRP3 and mitochondria are for surveying the mitochondrial integrity and sensing mitochondrial damage, or whether mitochondria simply serve as a physical platform for inflammasome assembly [

15]. Recognition of injury and stress signals by inflammasomes do not regulate transcription of immune response genes, but activate caspase-1, a proteolytic enzyme that cleaves and activates the secreted pro-cytokines interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and interleukin-18 (IL-18), and interleukin-33 (IL-33) into IL-1β, IL-18, and IL-33 [

10,

15]. In addition, TLR-mediated increased expression of above cytokines, autophagy and epigenetic factors have also been reported to modulate intensity of inflammation [

16] (

Figure 1).

Two types of inflammations have been reported to occur in humans and animals: (a) acute inflammation develops rapidly with the experience of pain, whereas (b) chronic inflammation develops slowly without the experience of pain. The onset of acute inflammation occurs in neurotraumatic diseases such as stroke, traumatic brain and spinal cord injuries. In contrast, chronic inflammation develops slowly in neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease) (

Table 1) [

17]. Chronic inflammation differs from acute inflammation in the threshold of pain perception. As a result, the immune system continues to attack at the cellular level. Chronic inflammation lingers for years causing continued insult to the brain tissue, ultimately reaching the threshold of detection [

18]. Chronic inflammation disrupts hormonal signaling networks in the brain and induces deficits in long-term potentiation (LTP), the major neuronal substrate for learning and memory. Induction of inflammation is closely interlinked with oxidative stress, a process that overwhelms the antioxidant defenses of the cells through the generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS) [

19]. This may be either due to an overproduction of ROS and RNS or to a failure of cell buffering mechanisms. It is difficult to establish the temporal sequence of their relationship.

The onset of inflammation is followed by a process called resolution, a turning off mechanism by cells to limit tissue injury [

20]. Resolution not only results in reduction of numbers of immune cells at the core of the injury site, clearance of apoptotic cells, and debris by increased phagocytic activity, but also in the induction of recently identified new molecules that activate tissue regeneration in the brain tissue. Levels of ARA and DHA-derived lipid metabolites in brain and visceral tissues are partly regulated by diet. At the molecular level, the resolution of inflammation is orchestrated by DHA-derived-bioactive lipid metabolites called resolvins (Rvs), neuroprotectins (NPDs), and maresins (MaR). NPD1 has been reported to play endogenous neuroprotective role by inhibiting apoptotic DNA damage, up-regulating anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and BclxL, and down-regulating pro-apoptotic Bax and Bad expression [

20,

21,

22].

Enzymatic metabolites of DHA metabolism not only downregulate proinflammatory cytokines but also produce anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-thrombotic, anti-arrhythmic, hypo-lipidemic, and vasodilatory effects [

23,

24]. Accumulating evidence supports the view that levels of ARA and DHA, and their lipid metabolites not only orchestrate and control the onset of inflammation and oxidative stress, but also cooperate in maintaining appropriate downstream actions and responses [

17,

23,

24,

25].

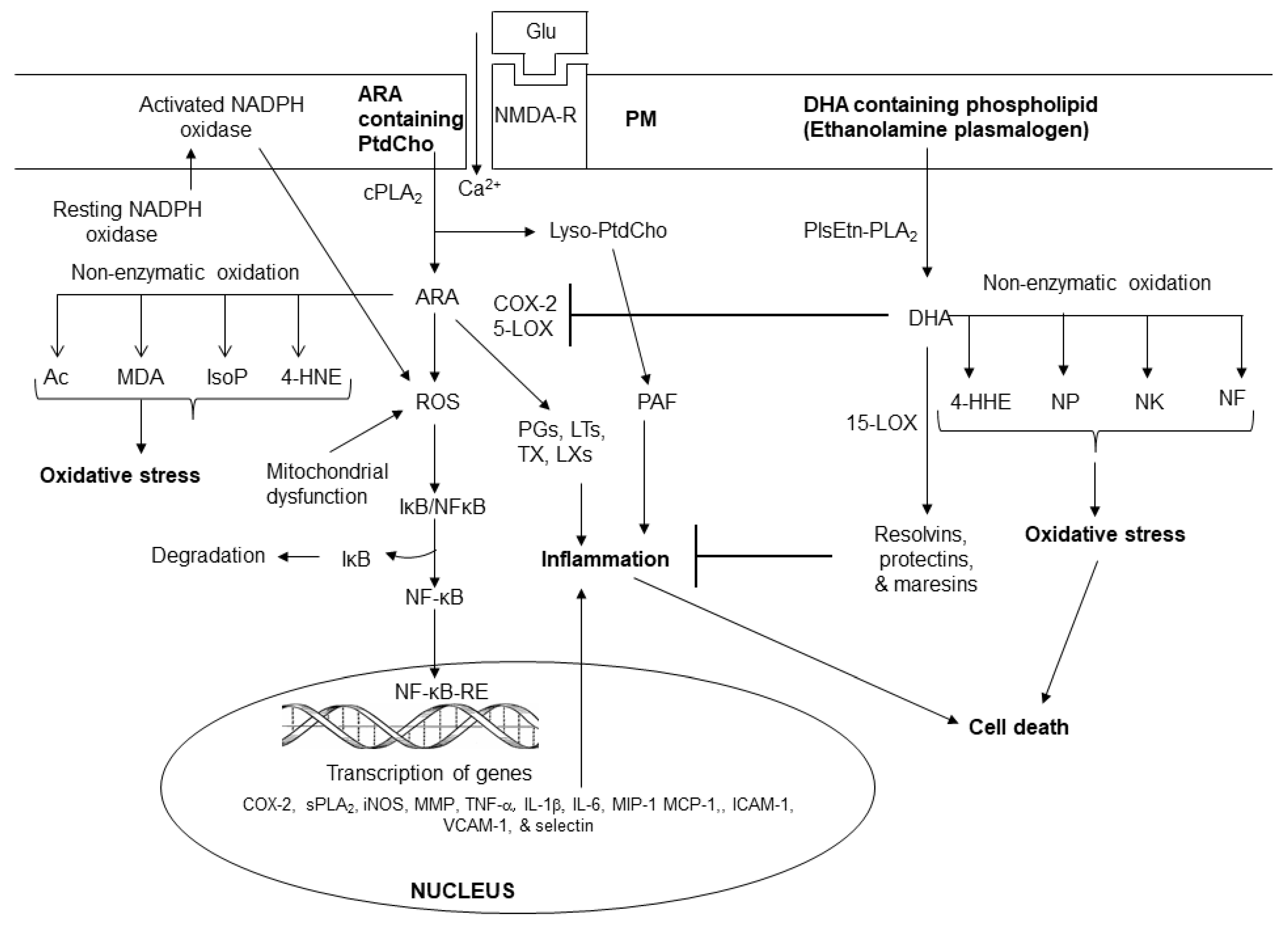

2.1. Phospholipid Metabolites in Inflammation

In response to cell stimulation or injury, phospholipids release polyunsaturated free fatty acids ARA or DHA from the sn-2 position of glycerol moiety through the action of phospholipase A

2 (PLA

2) [

1,

17,

23]. Enzymatic mediators of ARA metabolism are called as eicosanoids. They include PGs, LTs, TXs, and LXs (

Figure 2). These metabolites not only play important roles in internal and external communication, but also modulate inflammation through the upregulation of the expression of proinflammatory cytokines [

17,

24,

25]. Eicosanoids also modulate other cellular responses such as the growth arrest, differentiation, adhesion, migration, and apoptosis [

23]. Furthermore, eicosanoids also contribute to vascular function by regulating cerebral blood flow, angiogenesis, and pain [

24,

25]. Collective evidence suggests that inflammation involves several converging mechanisms responsible for sensing, transducing, amplifying, and turning off mechanisms that involve the participation of various eicosanoids [

24,

25]. Non-enzymically oxidation of ARA results in the production of 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), isoprostanes (IsoP), isoketals (IsoK), and isofurans (IsoF). These metabolites produce pro-oxidant, pro-thrombotic, pro-aggregatory, and pro-inflammatory effects.

(Figure 2).

Plasma membrane (PM); N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDA-R); glutamate (Glu); phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho); lyso-phosphatidylcholine (Lyso-PtdCho); cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2); plasmalogen-selective PLA2 (PlsEtn-PLA2); platelet activating factor (PAF); arachidonic acid (ARA); cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2); 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX); prostaglandins (PGs); leukotrienes (LTs); thromboxane (TXs); reactive oxygen species (ROS); 4-hydroxynonel (4-HNE); isoprostane (IsoP), acrolein (AC); malondialdehyde (MDA); nuclear factor kappaB (NF-κB); nuclear factor kappaB response element (NF-κB-RE); inhibitory subunit of NFκB (IκB); tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α); interleukin-1β (IL-1β); matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs); neuroprostane (NP); neurofuran (NF); neuroketal (NK); 4-hydroxyhexenal (4-HHE); Resolvin D.

The non-enzymatic lipid metabolites of DHA metabolism include 4-hydroxyhexanal (4-HHE), neuroprostanes (NPs), neuroketals (NKs), and neurofurans (NFs) (

Figure 2).

Enzymatic metabolites of DHA metabolism not only downregulate proinflammatory cytokines but also produce anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-thrombotic, anti-arrhythmic, hypo-lipidemic, and vasodilatory effects [

24,

25]. Accumulating evidence suggests that ARA and DHA-derived lipid metabolites compete with each other and regulate induction and regulation of inflammation by controlling the duration and magnitude of acute inflammation, oxidative stress as well as the return of the injury site to homeostasis [

17,

24,

25]. Level of ARA and DHA-derived lipid metabolites in brain and visceral tissues are partly regulated by diet. Collective evidence suggests that levels of ARA and DHA, and their lipid metabolites not only orchestrate and control the onset of inflammation and oxidative stress, but also regulate the action of lipid-dependent enzymes to execute appropriate downstream actions and responses [

17,

24,

25].

Lyso-phosphatidylcholine, the other product of PLA

2 catalyzed reaction either reacylated through acylation/ de-acylation cycle into native glycerophospholipids or converted into platelet activating factor (PAF; 1-O-alkyl-2-acetyl-

sn-glycerophosphocholine), which is a proinflammatory lipid molecule [

2]. It exerts its inflammatory effects by activating the PAF receptors that consequently activate leukocytes, stimulate platelet aggregation, and induce the release of cytokines and expression of cell adhesion molecules [

2]. It is reported that PAF is also involved in allergic reactions, and circulatory system disturbances such as atherosclerosis [

2].

2.2. Markers for Inflammation

Cytokines, chemokines, eicosanoids and platelet activating factor (PAF) are major biomarkers for inflammation. Levels of these biomarkers are increased in body tissues and fluids during inflammation [

17,

24]. These metabolites act on neural and non-neural cells directly as well as through eicosanoid receptors. Four types of eicosanoid receptors (EP

1, EP

2, EP

3, and EP

4) have been cloned [

25]. These receptors are G protein-coupled receptors, which evoke cellular responses through distinct intracellular mechanisms. Some prostaglandins, PGE

1, PGE

2 and PGD

2, are inflammatory [

26], whereas others PGs are anti-inflammatory such as PGD

2 and prostaglandin J

2 [

27]. High levels of eicosanoids contribute to the development of cytotoxicity, vasogenic edema, and cellular damage through the participation of NF-κB, isoforms of PLA

2, PLC, PKC and cytokines [

17,

24].

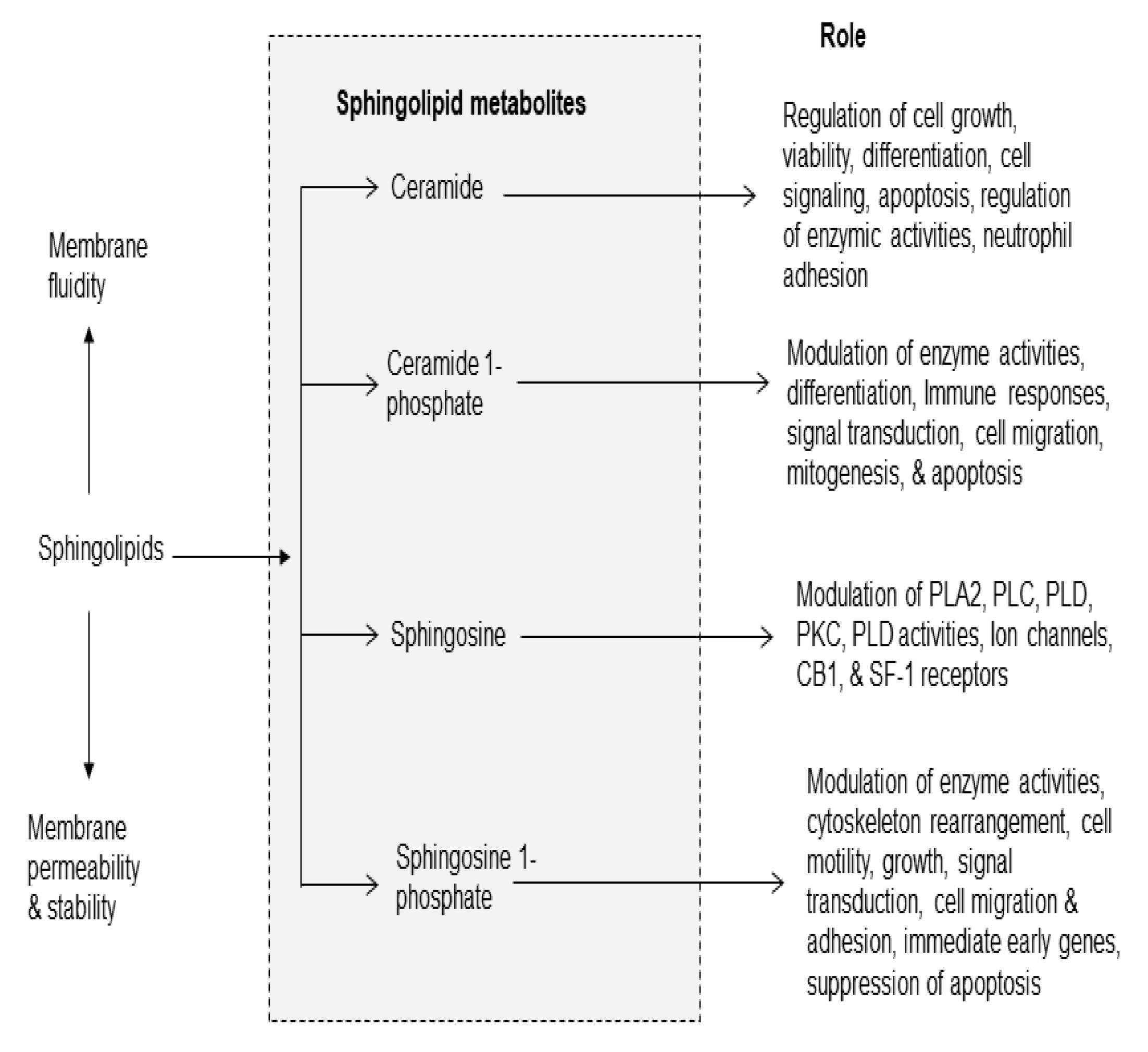

2.3. Sphingolipid Metabolites in Inflammation

Sphingolipids form a broad class of amphiphatic lipids with diverse functions. Sphingolipids consist of sphingomyelin, ceramide, ceramide 1-phosphate (C 1-P), sphingosine, and sphingosine1-phosphate (S1P). They can be rapidly converted into each other. Among above mentioned metabolites sphingolipids, ceramide, C 1-P) and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) have received the greatest attention (

Figure 3). In addition to serving as a precursor to complex sphingolipids, ceramide also regulates vital cellular functions, such as cell growth, viability, differentiation, proliferation, migration and angiogenesis, apoptosis, inflammation, regulation of enzyme activities, neutrophil adhesion to the vessel wall, and vascular tone [

28]. Several studies have indicated that ceramide, C 1-P, and S1P an important role in inflammation [

29].

Sphingomyelin is hydrolyzed by enzyme called sphingomyelinases (SMases). These enzymes are abundantly present in the brain and visceral tissues. They catalyze the hydrolysis of sphingomyelin into ceramide and phosphorylcholine [

30]. These enzymes are a major, rapid source of ceramide and S1P production not only in response to receptor stimulation, but also in pathological conditions such as oxidative stress and inflammation. Stimulation of TNF-α receptor results in activation of acid and neutral SMases and sphingosine kinases (SK). Activation of these enzymes contribute to the generation of ceramide and C1-P, S1P, and subsequent activation of the pro-inflammatory transcription factor, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) [

31]. Under normal conditions, NF-κB/ Iκ-Bα complex (inhibitory form) is present in the cytoplasm. During oxidative stress and pathological conditions, NF-κB/ Iκ-Bα complex breaks down and free NF-κB migrates to the nucleus, where it interacts with NF-κB response element (NF-κB-RE). The binding of NF-κB to NF-κB-RE promotes the expression of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6) and chemokine [

30] and free IκBα is degraded by the ubiquitin proteasome system. Cytokines and chemokines act via specific receptors, which are expressed on the neural and non-neural cell membranes of their target cells. Their action involves a complex network linked to feedback loops and cascade through the activation of protein kinases and PLA

2. At low levels, cytokines and chemokines are required for cell metabolism and survival under normal, but at higher levels an imbalance among cytokines and chemokines is detrimental to cells. The activation of NF-κB is also coupled with the stimulation of PLA

2, cyclooxygenases (COXs) and lipoxygenases (LOXs) and generation of PG, LTs, and TX [

2].

Often inflammatory responses are temporary only occurring locally, and activated to protect from the invasion of pathogens or injury and to promote repair of tissue damage. However, when uncontrolled or inappropriate, acute inflammation can lead to persistent chronic inflammation, causing the development of autoimmune or circulatory system diseases, neurological disorders (Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease) and metabolic diseases, including type 2 diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disease, and even cancer; if the inflammatory response is left unchecked, many inflammatory mediators are released into the blood, causing sepsis, which can lead to death [

24,

32]. It is suggested that timely resolution of inflammation is crucial for preventing severe and chronic inflammation in neurodegenerative diseases [

24,

32].

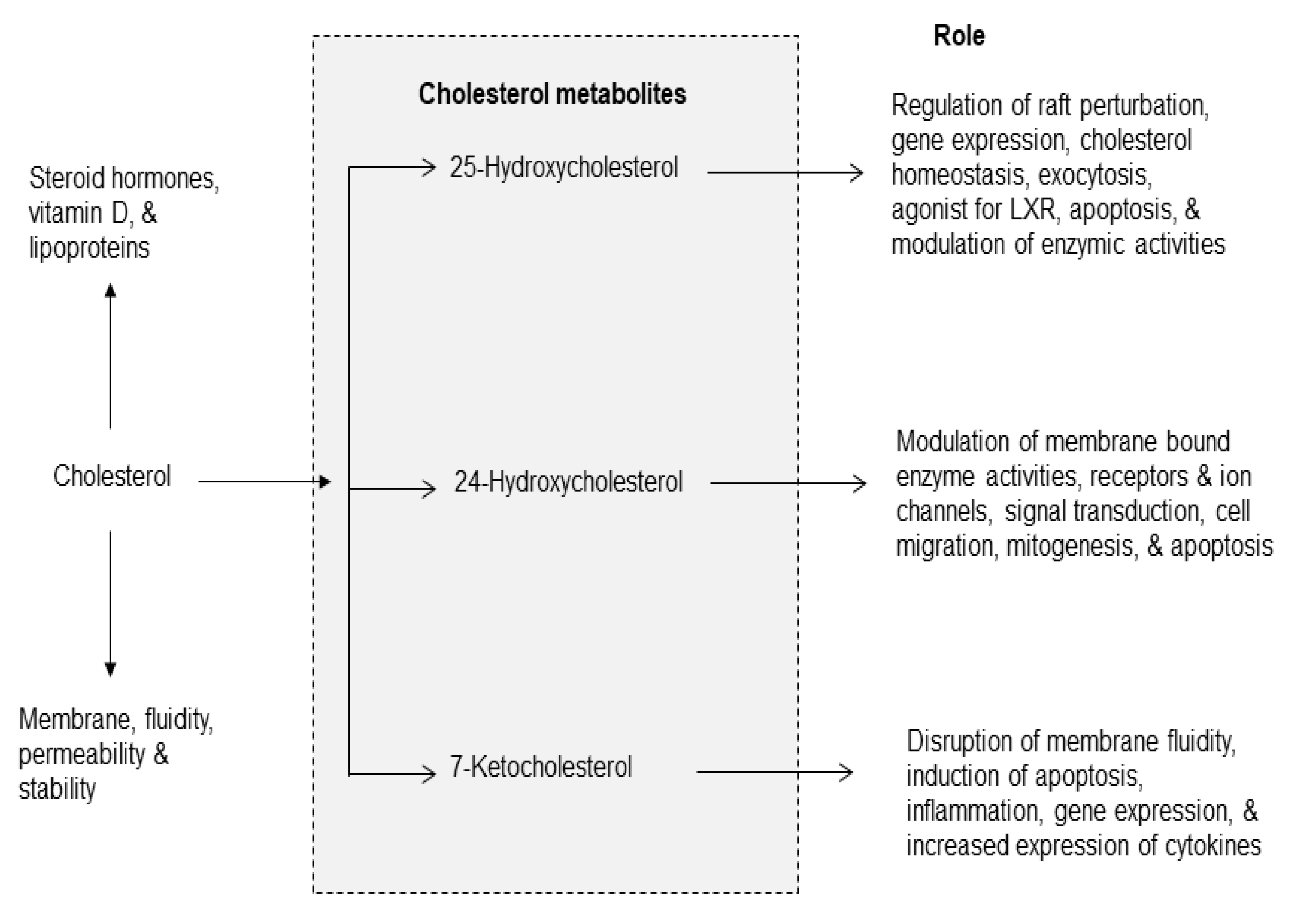

2.4. Cholesterol Metabolites in Inflammation

Cholesterol is an essential component of the mammalian cell membranes [

2,

33]. It not only contributes to membrane fluidity and permeability, but also major component of lipid rafts, which are platforms for signal transduction processes [

2]. In brain, about 70% of cholesterol is present in myelin sheath, where it is involved in synaptogenesis, maintenance, turnover, and stabilization of synapses [

34]. Cholesterol has many other biological functions, such as the synthesis of vitamin D, steroid hormones (e.g., cortisol, aldosterone, and adrenal androgens), and sex hormones (e.g., testosterone, estrogens, and progesterone). Cholesterol cannot cross the blood–brain barrier, and thus the brain synthesizes and metabolizes its own pool of cholesterol. The primary metabolic enzymes for brain cholesterol are cholesterol hydroxylases (CH24H), which metabolize cholesterol into 24

S-hydroxycholesterol (24HC), and 25-hydroxycholesterol (25HC) (

Figure 4) [

34,

35]. Dysregulation of CH24H and 24HC can affect neuronal excitability through a range of mechanisms. 24HC is a positive allosteric modulator of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. These receptors are coupled with the increase in glutamate release and stimulation of PLA

2 resulting in degradation of phospholipid in neural membranes [

17,

35,

36]. Among cholesterol metabolites, 7-KC is a pro-inflammatory oxysterol usually associated with oxidized lipoprotein deposits present in aged retinas [

37]. Increased levels of 7-KC are also found in the tissues, plasma, and/or cerebrospinal fluid of patients with cardiovascular diseases, eye diseases, and neurodegenerative diseases [

32,

38]. ARA also interacts with 7-KC in the presence of Acyl-CoA cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT) to form the 7KC-ARA complex [

39].

This complex is closely associated with various pathological processes, including cardiovascular diseases and age-related macular degeneration. It is proposed that 7-KC-mediated inflammatory responses in endothelial cells elevates the risk of cardiovascular diseases, Alzheimer’s, disease and age-related macular degeneration [

39,

40,

41]. In addition, treatment of murine neuronal N2a cells with 7-KC not only results in overproduction of ROS, but alterations in plasma membrane, and drop of transmembrane mitochondrial potential (ΔΨm) leads to cell death. Unesterified 7-KC is also known to disrupt membrane fluidity promotes inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis.

During oxidative stress, production of ROS contributes to inflammation in two ways: (a) interactions of ROS with NF-κB/IκB complex in the cytoplasm producing free NF-κB, which migrates to the nucleus, where it binds with NF-κB response element and promotes the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules [

17,

41] and (b) in macrophages 7-KC activates the immune sensor TLR4, which also promotes the translocation of free NF-κB to the nucleus promoting the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines [

17,

41]. Levels of oxysterols (including 7-KC) can be regulated through several mechanisms of cholesterol clearance. ATP-binding cassette (ABC) efflux pumps play important roles in exporting oxysterols from cells in various tissues, and the expression of these transporters is one mechanism by which intracellular oxysterol levels can be regulated [

39].

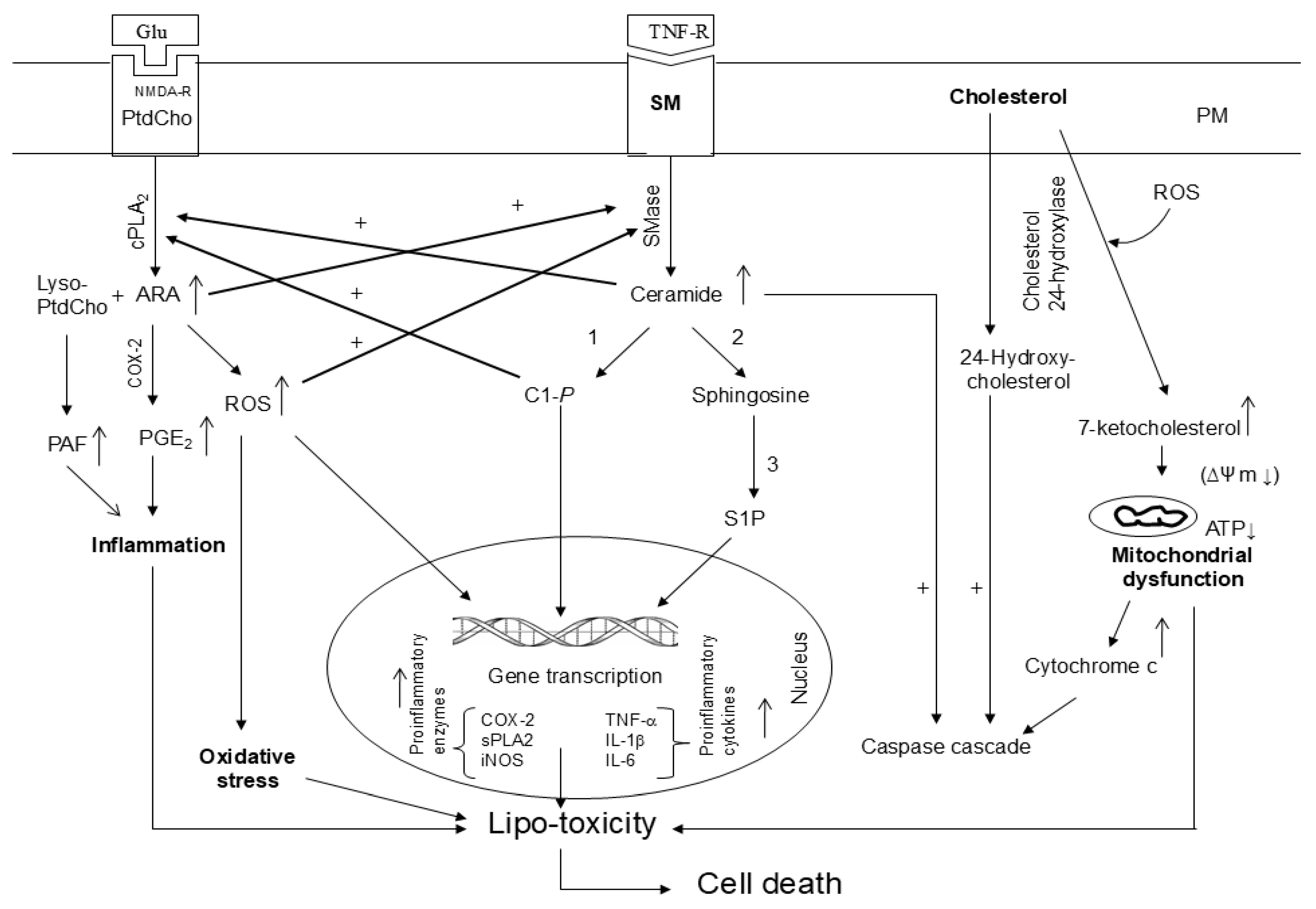

3. Cross-Talk Among Phospholipid, Sphingolipid, Cholesterol Metabolites in Inflammation

In visceral tissues and brain, the metabolism of phospholipid, sphingolipid, and cholesterol is interrelated and interconnected. Many cellular stimuli (neurotransmitters, cytokines, and growth factors) modulate more than one enzyme of phospholipid, sphingolipid, and cholesterol metabolism at the same time. Thus, sphingolipid metabolism metabolites (ceramide, C 1-P, and S1P) stimulate cPLA

2 activity and metabolites of phospholipid metabolism (arachidonate and ROS) stimulate SMases suggesting a cross-talk between metabolites of phospholipid and sphingolipid metabolism [

42,

43] (

Figure 5). The significance of cross-talk between phospholipid and sphingolipid metabolites and normal cellular processes lies in their levels, exposure time, and crucial roles of lipid metabolites not only in maintaining overall cellular health, but also influencing the onset of metabolic and neurological disorders. Thus, cross-talk between different lipid families commonly occurs during phospholipid and sphingolipid metabolism and lipid metabolites act as signaling molecules, influencing cellular functions and impacting processes like energy production, inflammatory cell signaling, and even progression of metabolic and neurological disorders [

17,

40]. In addition,

7-KC produces mitochondrial dysfunction not only by triggering oxidative stress and inflammation, but also impairing fatty acid oxidation, which, in turn, can contribute to fatty acid oxidation, lipid accumulation, and lipo-toxicity [

44]

. Furthermore, 7-KC has been reported to produce an excessive mitophagy (intracellular degradation of damaged mitochondria) by means of autophagy [

45]

. It is reported that mitochondrial dysfunction is closely associated with the onset and progression of many chronic diseases involving inflammatory response through NF-κB and inflammasome activation. Damaged mitochondria can also play an important role in inflammasome activation by releasing danger-associated molecular patterns (

DAMPs) such as ROS, mtDNA, and ATP [

46]

. These DAMPs can trigger pro-inflammatory signaling pathways, such as the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β and IL-18 [

47,

48]

. Impaired mitochondrial function can disrupt cellular metabolism and bioenergetics, further enhancing the inflammatory responses. Collective evidence suggests that dysregulation of the balance between sphingolipids, phospholipids, and cholesterol metabolites may result in “lipo-toxicity”, a term coined by Unger 17 years ago to describe the toxic effects of excessive free fatty acids on pancreatic beta cell survival [

49]. The term has never been formally defined but has been used variably to describe cellular injury and death caused by free fatty acids, their metabolites, increase in ceramide/sphingosine pools, and 7-KC mediated mitochondrial dysfunction in non-neural tissues [

50,

51,

52,

53]. The molecular mechanisms underlying lipo-toxicity may include high levels of lipid metabolites, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired autophagy, and onset of inflammation [

50]. The induction of these processes may result in cellular dysfunction and death in diverse tissues including brain, kidney, and heart [

51,

52,

53].

Plasma membrane (PM); Plasma membrane (PM); N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDA-R); glutamate (Glu); phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho); cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2); arachidonic acid (ARA); sphingomyelin (SM); cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2); prostaglandin E2 (PGE2); ceramide 1-phosphate (C 1-P); sphingosine 1 phosphate (S 1 P); reactive oxygen species (ROS); tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α); interleukin-1beta (IL-1β); ceramide and C 1-P stimulates cPLA2; ARA metabolites and ROS stimulate sphingomyelinases (SMases); Hydroxycholesterols and 7-ketocholesterol stimulate caspase cascade and promote mitochondrial; 1. ceramide kinase; 2. ceramidase; 3. sphingosine kinase; and (+) indicate stimulation.

Under physiological conditions, homeostasis between phospholipid sphingolipid, and cholesterol-derived metabolites is based not only signaling network, but also optimal levels of lipid metabolites. However, under pathological conditions, marked increases in levels of phospholipid sphingolipid, and cholesterol-derived metabolites may disturb the signaling networks, and result in loss of communication among lipid metabolites. This process not only threatens the integrity of cellular lipid homeostasis, but also facilitates cell death [

25,

44]. The severity of the lipo-toxic insult can be modulated by the specific cellular genetic vulnerability and toxicity induced by lipid metabolites.

4. Conclusion

The generation of phospholipid, sphingolipid, and cholesterol-derived lipid metabolites is necessary for normal cellular function. ARA-derived lipid metabolites (PGs, LTs, TXs, and LXs) produce inflammation. In contrast, DHA-derived lipid metabolites block inflammation not only by promoting potent anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution effects, but also by enhancing clearance of apoptotic cells and debris from inflamed tissues. Sphingolipid-derived lipid metabolites include ceramide, C 1-P, and S 1 P. These mediators are involved in the modulation of signal transduction processes associated with apoptosis, inflammation, oxidative stress, and cell growth. The cross-talk among phospholipid, sphingolipid, and cholesterol-derived lipid metabolites modulates the intensity of inflammation and oxidative stress. These processes may contribute to lipo-toxicity and cell death.