1. Introduction

Inflammation is as important, protective response of the body to noxious insults [

1]. The initial inflammatory response is the cellular release of pro-inflammation lipid mediators, e.g. eicosanoids such as prostaglandins and leukotrienes followed by resolution of the inflammation by lipid mediators called specialized pro-resolution mediators (SPM), e.g., resolvins, protectins, epoxins, etc [

1]. The pro-inflammation lipid mediators are derived from precursor, long chain Ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA), principally arachidonic acid (AA) whereas the pro-resolution lipid mediators are derived chiefly from Ω-3 fatty acids, principally eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) [

1].

Alcohol use during pregnancy is a significant public health problem. About 1 in 7 pregnant people in the United States reported drinking alcohol in the past 30 days from the time of the interview, and about 1 in 20 pregnant people reported binge drinking [

2]. Alcohol abuse during pregnancy is a leading cause of mental disability in children [

3]. A major brain disorder associated with maternal alcoholism is the Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) and its most severe form, the Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) [4.5]. Globally, it has been estimated that about 10% of 121women in the general population consume alcohol during pregnancy, and 1 in 67 women delivers a child with FAS [

6]. Reports have estimated that the pooled prevalence of FAS and FASD in the United States was about 2 per 1000 and 15 per 1000, respectively, among the general population [

6,

7].

The mechanism underlying FASD is still poorly understood, although unresolved inflammation likely plays a significant role. Alcohol is toxic to the brain and can initiate an inflammatory response characterized by the generation of reactive oxygen species and lipid mediators of inflammation [

8,

9,

10,

11]. The aim of our study was to assess, in a rat model, the pro-inflammation and pro-resolution brain lipid mediators in response to chronic, alcohol exposure at low (1.6 g g/kg/day) and high (2.4 g/kg/day) alcohol doses and the effect of DHA supplementation in mitigating the inflammation process of alcohol at the high dose.

2. Materials and Methods

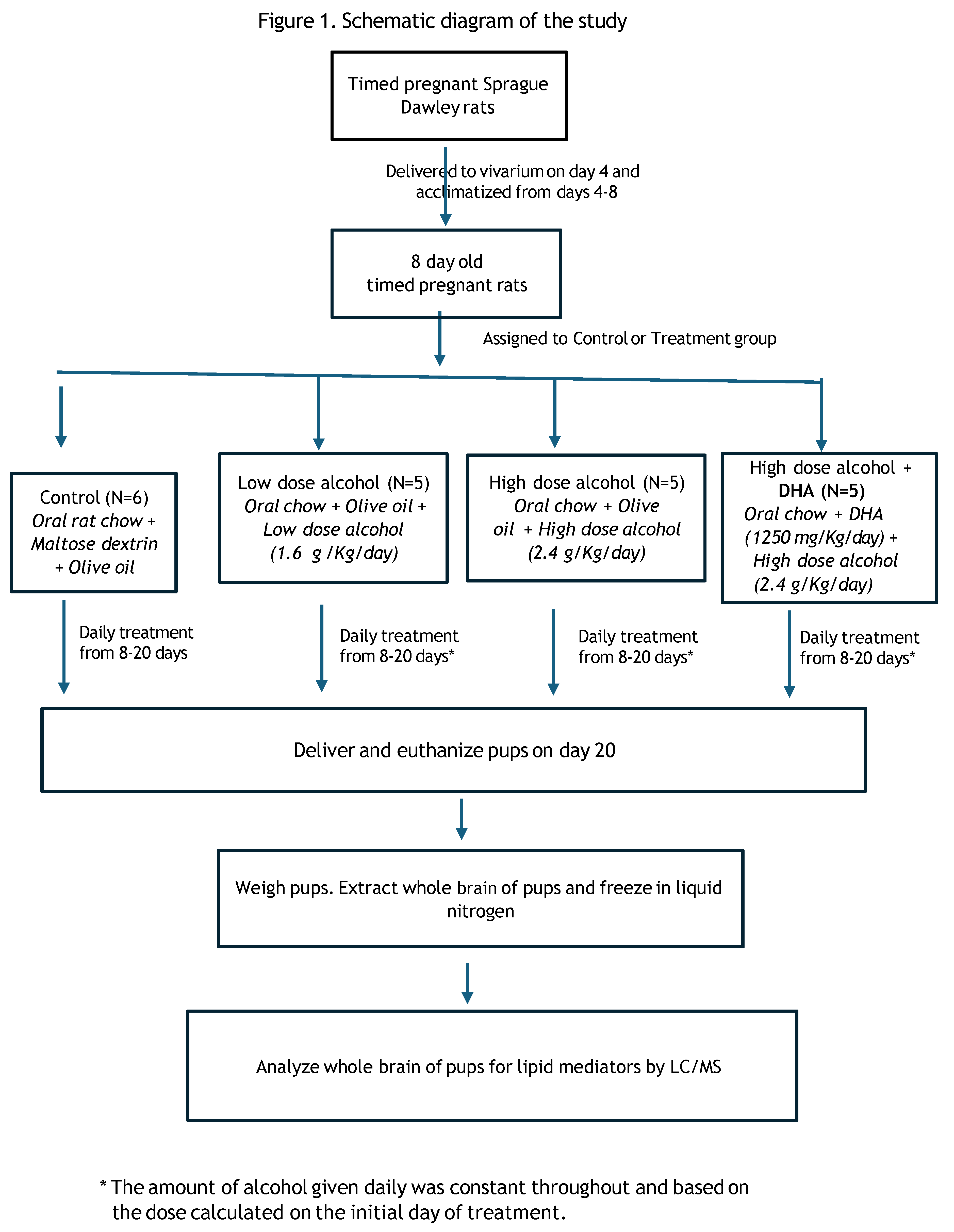

The study consisted of 4 groups of timed-pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats (dams):

1. Control (C)

2. Low dose alcohol (LD) at 1.6 g alcohol/kg/day

3. High dose alcohol (HD) at 2.4 g alcohol/kg/day

4. High dose alcohol + DHA (HD/DHA) at 2.4 g alcohol/kg/day + DHA ((1250 mg/kg/day)

The dams were obtained from Charles River Laboratories and delivered to the vivarium on gestational day (GD) 4. Each dam was randomly assigned (Research Randomizer,

www.randomizer.org) to either the Control or Treatment group. The animals were placed in individual cages and provided with standard rat chow and water ad libitum. The room was at a constant (22°C) temperature on a 16-hour dark/8-hour light cycle (lights off from 1730 to 0930 hours).

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan. (Protocol # IACUC-19-08- 1222, Wayne State University)

A flow chart diagram of the study is shown in

Figure 1.

2.1. Control Group (N=6)

The control group was given daily gavage feedings in 2 divided doses of maltose/dextrin solution and olive oil starting from GD 8 to day 20. Olive oil was given to the dams in groups 1-3 as a control for the docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) lipid that was given to group 4. The volume of olive oil was equal to the average total volume of DHA given to Group 4. Maltose/dextrin solution served as the control for the caloric load of 2.4 g/k/d alcohol. It was given to the Control group based on the caloric content of alcohol of 7 calories per gram and the caloric content of maltose/dextrin of 95 calories per 25 grams. The caloric load of olive oil was 120 calories per 15 mL and the caloric load of DHA was 123 calories per 15 mL.

The total volume of maltose/dextrin/olive oil was approximately equal to the total volume of alcohol+olive oil given to the alcohol group and given by gavage in 2 divided doses not to exceed the maximum safety limit of 10 mL/kg per gavage. Based on the initial weight of the dams, the volume of olive oil that was given by gavage was 0.8 ml per day and maltose dextrin was 1.8 mL per day.

Nine dams were initially assigned to the Control group to anticipate the possible replacement of rats in the treatment groups that resisted initial gavage feedings. Replacement of 3 dams assigned to the treatment group that resisted gavage reduced the number of dams in the Control group to 6 dams. There was no pair-fed control group. Similarly, we did not include a group given alcohol alone without lipid supplementation since data also from our previous study showed that prenatal alcohol exposure alone resulted in undesirable, adverse effects of low birth and brain weight in the fetus and low placental weight [

12].

2.2. Alcohol Groups

In the study design, the daily dose of alcohol given to the treatment group was constant and based on the initial weight of the dam at the start of treatment (day 8). The study design of a constant, daily dose of alcohol was similar to our previous study [

12] since we were concerned that varying daily alcohol doses per treatment group based on changing weight of the dams would introduce an important confounder to the alcohol effect.

2.2.1. Low Dose (LD) Alcohol at 1.6 g Alcohol/kg/Day (N=5)

The stock alcohol solution of 29.85% (volume/volume) was made by diluting 30 mL of 99.5% ethanol solution (Spectrum Chemical MFG Corporation, New Brunswick, New Jersey) with 70 mL distilled water. At the density of alcohol of 0.7892 g/mL, the stock solution contained 0.7892 g/mL of alcohol. The low alcohol dose was 1.6 g/kg/d plus olive oil (volume for volume with DHA) given daily by gavage in 2 divided doses from gestational day 8 to day 20. Based on the different initial weights of the dams, the gavage volume of 29.85% alcohol that the dams received ranged between 1.6 -1.9 ml per day and the volume of olive oil given was 0.8 mL per day.

2.2.2. High Dose (HD) Alcohol at 2.4 g Alcohol/kg/Day (N=5)

As in the low-dose alcohol group, the 29.85% stock solution of alcohol was used for the high alcohol dose of 2.4 g/kg/d given by gavage with olive oil (volume for volume with DHA) in 2 divided doses from gestational day 8 to day 20. Based on the initial weight of the dams, the gavage volume of 29.85% alcohol that the dams received in the alcohol + DHA group ranged between 2.2 – 2.5 mL per day. The volume of olive oil given was 0.8 mL per day.

We did not determine initial blood alcohol level on the dams and estimated the alcohol level based on a similar study of Bielawski [

13]. wherein at an alcohol dose of 3 g/kg alcohol, given in 2 divided doses, the peak alcohol level at 0.5 h was 53 ± mg/dL.

2.2.3. High Dose Alcohol + DHA (HD/DHA) at 2.4 g Alcohol/kg/Day + DHA at 1250 mg/kg/DAY (N= 5).

A safety study in pregnant rats showed that a DHA dose of 1250-2500 mg/kg was safe. It did not produce overt maternal toxicity, and did not result in any changes in implantation losses, resorptions, live births, sex ratios, or fetal malformation [

14]. DHA was obtained from DHASCO oil (DSM Nutritional Products, Columbia, MD) which is a triglyceride extracted from the algae

Crypthecodinium cohnii. It contains approximately 35% DHA (350 mg/mL DHA), 15% omega-6 docosapentaenoic acid (DPAn-6, 22:5n-6), and saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids. A daily dose of 1250 mg/kg of DHA from DHASCO oil was given together with a high dose alcohol of 2.4 g/kg/day in 2 divided doses from gestational day 8 to day 20. The complete composition of the DHASCO oil is provided in the Supplement 1.

Based on the initial weight of the dams, the gavage volume of 29.7% alcohol that the dams received in the alcohol + DHA group ranged between 2.2 – 2.5 mL per day. DHA was given at 0.8 mL per day.

2.2.4. Gavage Feeding

Intubation of the dams for gavage feeding was started on gestational day 8 until day 20. The feedings were administered in 2 separate gavages, two hours apart, beginning at 10 am. The gavage feedings were administered through a 3” 16-gauge, curved, stainless, steel blunted needle designed especially for this purpose (e.g. perfectum #7916 CVD). The dams were not anesthetized nor tranquilized during the gavage

feedings so as not to confound the effect of prenatal alcohol exposure on the offspring by other drugs. Anaesthetization or tranquilization was not required since the procedure was brief and tolerated when performed by well-trained technicians. The research team received formal animal training in gavage feeding from the Department of Laboratory Animal Research (DLAR) at Wayne State University. The dams were restrained by manual wrapping in a towel and the duration of restraint was short to minimize stress. Gavage feeding was not initially tolerated by some rats and required several attempts at intubations within a 24-hour period. We enlisted the help of the DLAR personnel to assist in the gavage feeding should such difficulty arise. The total number of attempts for gavage feeding did not exceed three times per day. For the dams in the treatment group that persistently resisted the initial gavage feedings, they were replaced by a total of 3 dams in the Control group that tolerated gavage feeding. This resulted in 6 dams remaining in the Control group.

The dams tolerated well the volume of given ethanol plus DHA or olive oil. At the high dose of 2.4 g alcohol/kg/day some dams were slightly intoxicated approximately 30 minutes after the alcohol feeding but regained motor ability, including normal feeding and drinking within 4 hours. They were monitored for 15 minutes after alcohol feeding to look for signs of labored breathing or distress per protocol of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Wayne State University.

2.2.5. Delivery of the Dams and Pups

The normal duration of gestation of the dams is approximately 21 days but we delivered the fetuses on GD 20 to prevent breastfeeding of the spontaneously delivered pups on GD 21. On GD 20, the dams were narcotized rapidly with C02 gas, and death was immediately induced by cutting through their chest wall with a small scissor to produce a pneumothorax. The chest cavity was then opened with the scissor, and the heart was cut to further ensure death. A laparotomy was immediately performed, and the uterine horns were exteriorized, opened and the fetuses were delivered. The placenta, umbilical cord, decidua, and fetal membranes were also harvested. The immediate cessation of uterine blood flow and oxygen delivery to the fetuses resulted in the rapid death of all the fetuses. A total of 8 pups per dam that were most proximal to the uterus were obtained, 4 from each uterine horn. The pups were immediately weighed, decapitated, and the head immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at -80 degrees C for future analysis of brain lipid mediators of inflammation.

We could not determine the sex of the pups based on the standard anogenital distance since the pups were very small and the key structures were difficult to identify. The difficulty and inaccuracy of sex determination would also have taken too much time with 160 pups to examine and would have been problematic considering that we had to sacrifice and process all the dams and pups at approximately the same time, so that alcohol exposure would be similar in the alcohol groups.

Since the brain of the pups were very small and soft, it was not possible obtain individual parts of the brain for separate analysis of lipid mediators. Instead, for each pup, we took the whole brain and analyzed it as one sample. However, we did not pool the brain of all the pups from each litter into one sample. Rather we analyzed the whole brain of each pup separately.

2.2.6. Brain Lipid Analysis

Thawed brain tissue from rat pups was used to prepare samples for liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LCMS) analysis. The pup’s head was retrieved from the deep freeze. The skull was opened to obtain the entire brain content, and the brain was weighed and thawed on ice. The thawed brain tissue was suspended in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (50 mM phosphate, 0.9% NaCl, pH 7.4) containing 10 mM butylated hydroxytoluene at a ratio of 1:9 (w/v, tissue to buffer). Zirconium beads were added to the sample and homogenized by high-frequency oscillation (PreCellys, Bertin Instruments, Rockville, Md). The homogenate was centrifuged at 1,000g for 10 min and the supernatant was collected for lipid mediator extraction and analysis as previously reported [

15,

16]. Briefly, the homogenate was supplemented with 5 ng each of stable isotope-labeled internal standards (Prostaglandin E1-d4, Resolvin D2-d5, Leukotriene B4-d4, 15-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid-d18 (HETE) and 14R,15S-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid (14,15-EpEtrE-d11) - Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and applied to StrataX Solid Phase Extraction columns

(Phenomenex, Torrance, CA). The eluates were analyzed by LCMS on a QTRAP5500 mass spectrometer following high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) separation on Luna C18(2) (2x150 mm, 3µ) column as previously described [

15,

16]. Lipid mediator concentrations were calculated against the internal standards and normalized to the protein concentration in the homogenate (ng/mg protein).

2.2.7. Statistical Analysis

We enrolled eight pups from the litter of each dam, four pups from each uterine horn. The sample size gave us a power between 90-95% to detect a medium effect size among groups at p<0.05 for statistical significance. Each lipid metabolite was an independent measure and was compared to the type of treatment for groupwise changes since the aim of the study was to compare specific lipid metabolite concentrations based on treatment groups and not between metabolites. The homogeneity of variance was determined by Levene’s test, and if homogenous, the sample means were compared by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). If the variance was nonhomogeneous, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis (or H test) line test was used for paired comparison. A p<0.05 value in the ANOVA or Kruskal Wallis tests was considered as the level of statistical significance. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Version 29.

3. Results

3.1. Birth Weight

The mean birth weight of the pups when delivered at day 20 of gestation is shown in

Table 1.

The number of fetuses reported is the number of fetuses obtained per litter and not the litter size. The mean birth weight was significantly higher in pups prenatally exposed to high-dose alcohol compared to the control group (4.10 g versus 3.06 g, p <0.05). Similarly, the mean birth weight of pups prenatally exposed to high-dose alcohol/DHA was significantly higher compared to the control group (3.54 g versus 3.06 g, p = 0.05). The mean birth weight was significantly higher in pups prenatally exposed to high-dose alcohol when compared to the high-dose alcohol/DHA (4.10 g versus 3.54 g, p = 0.02). Similarly, the mean birth weight of pups was also significantly different between LD alcohol and HD alcohol/olive oil group (3.08 g vs. 4.10 g, p = 0.05) or HD alcohol/DHA group (3.08 g vs. 3.54 g, p = 0.05). There was no significant difference in the mean birth weight of pups in the low-dose alcohol group compared to the control group (3.08 versus 3.06, p>0.05).

3.2. Dam Weights

The mean weight of the dams at gestation 8 and 20 are shown in

Table 2. There was no significant difference in the dam weight in the different treatment groups at GD 8 and 20. The alcohol dose was calculated from the initial weight of the dams.

3.3. Placental Weights

The mean placental weights from each treatment group are shown in

Table 3. The mean placental weight in the control group was significantly smaller in the control group compared to the treatment groups (ANOVA, p<0.001).

Table 3.

Mean placental weight (± SD) in Control, low dose alcohol (LD), high dose alcohol (HD) and high dose alcohol + DHA (HD/DHA). Comparison of means by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Duncan’s test.

Table 3.

Mean placental weight (± SD) in Control, low dose alcohol (LD), high dose alcohol (HD) and high dose alcohol + DHA (HD/DHA). Comparison of means by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Duncan’s test.

| Treatment Group |

N |

n |

Mean Placental Weight (g) |

SD |

95 % Confidence Interval |

| Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

| Control |

6 |

48 |

0.49 |

0.08 |

0.46 |

0.51 |

| LD |

5 |

38 |

0.59 |

0.12 |

0.55 |

0.63 |

| HD |

5 |

40 |

0.57 |

0.07 |

0.55 |

0.59 |

| HD/DHA |

4 |

32 |

0.58 |

0.10 |

0.55 |

0.61 |

| Duncan’s test a,b |

| Group |

N |

Subset for alpha = 0.05 |

| 1 |

2 |

| Control |

48 |

.485 |

|

| High dose |

40 |

|

.568 |

| DHA/alcohol |

32 |

|

.581 |

| Low dose |

38 |

|

.592 |

| Sig. |

|

1.000 |

.275 |

| Means for groups in homogeneous subsets are displayed. |

| a. Uses Harmonic Mean Sample Size = 38.685. |

| b. The group sizes are unequal. The harmonic mean of the group sizes is used. Type I error levels are not guaranteed. |

3.4. Brain Inflammation Lipid Mediators

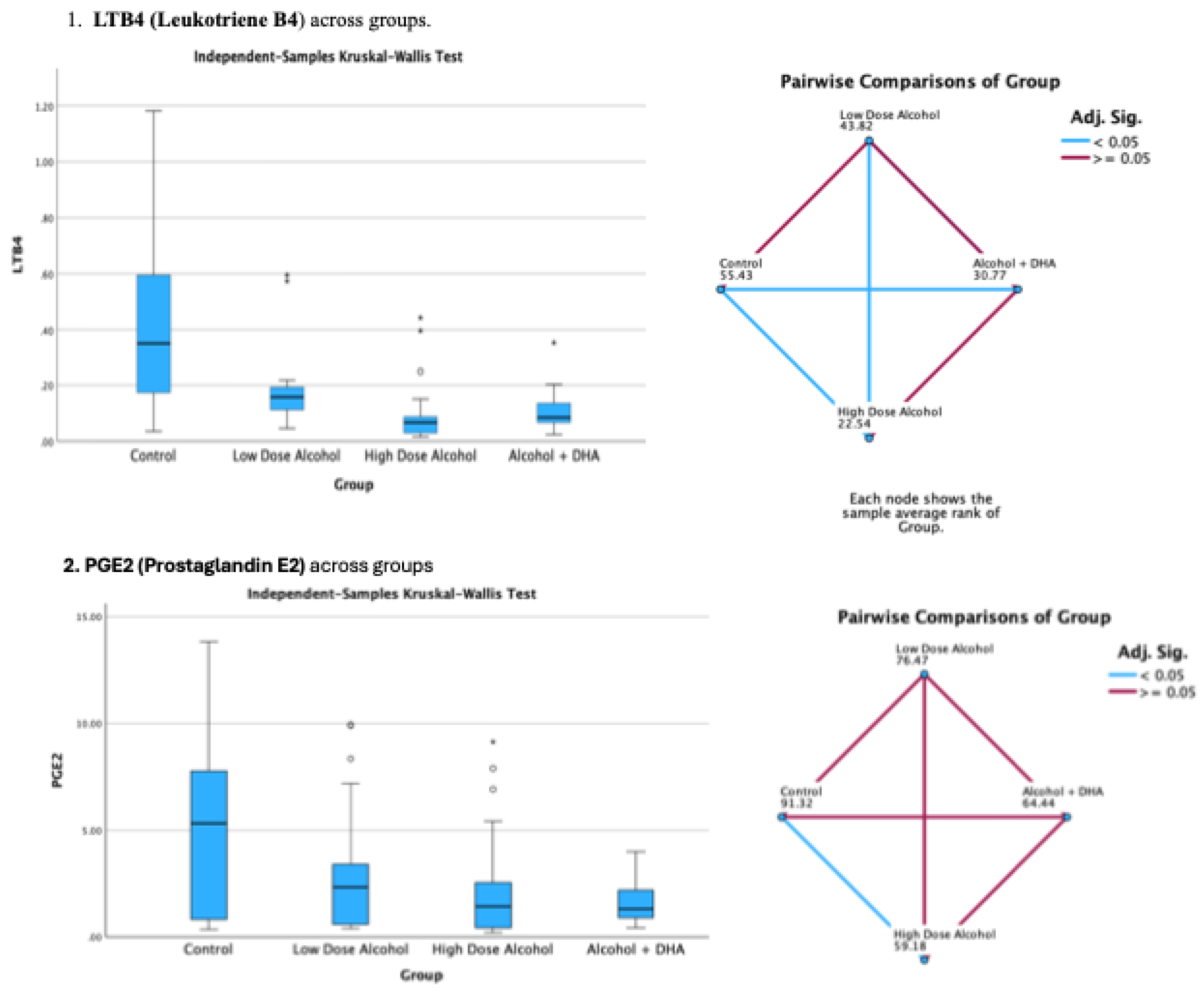

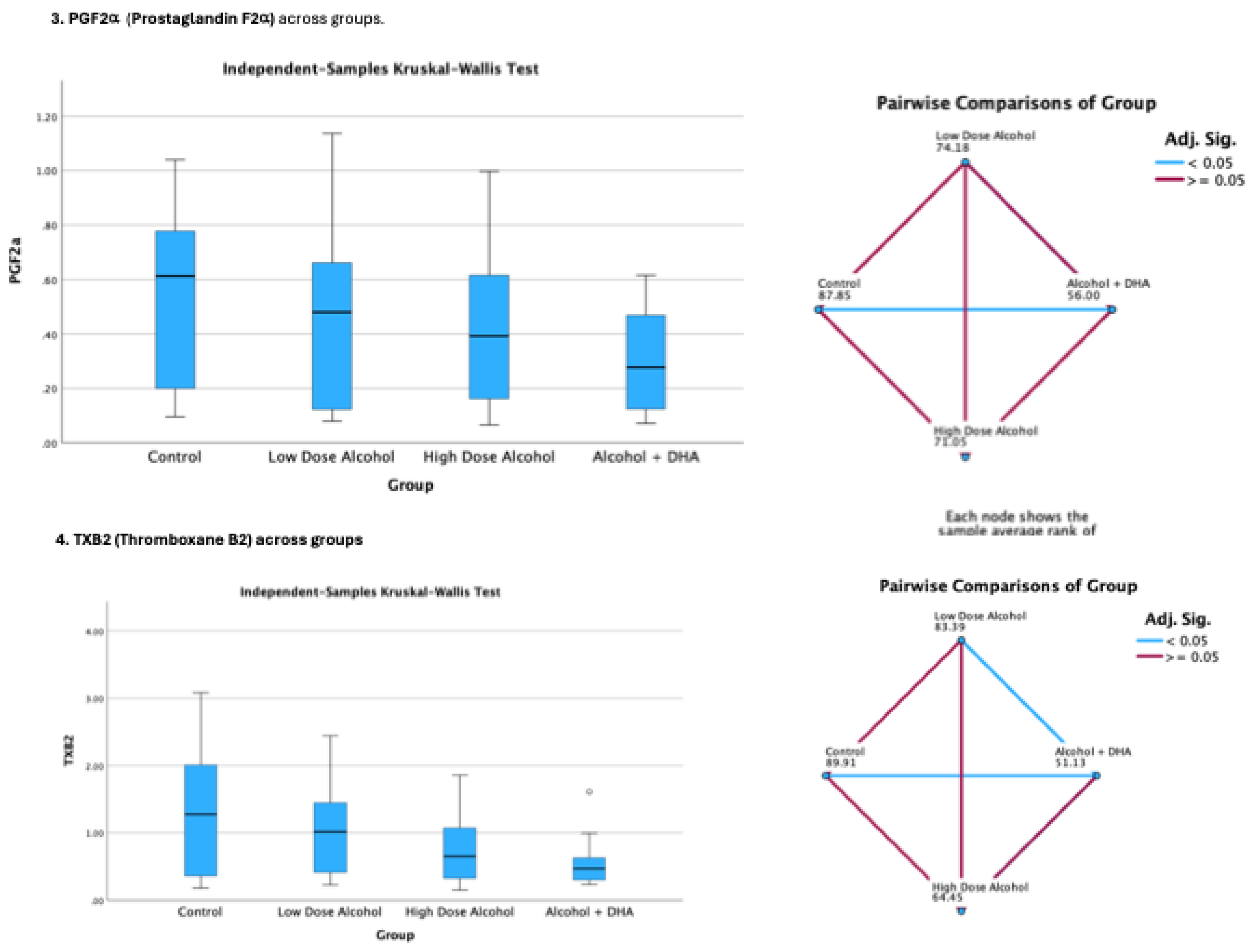

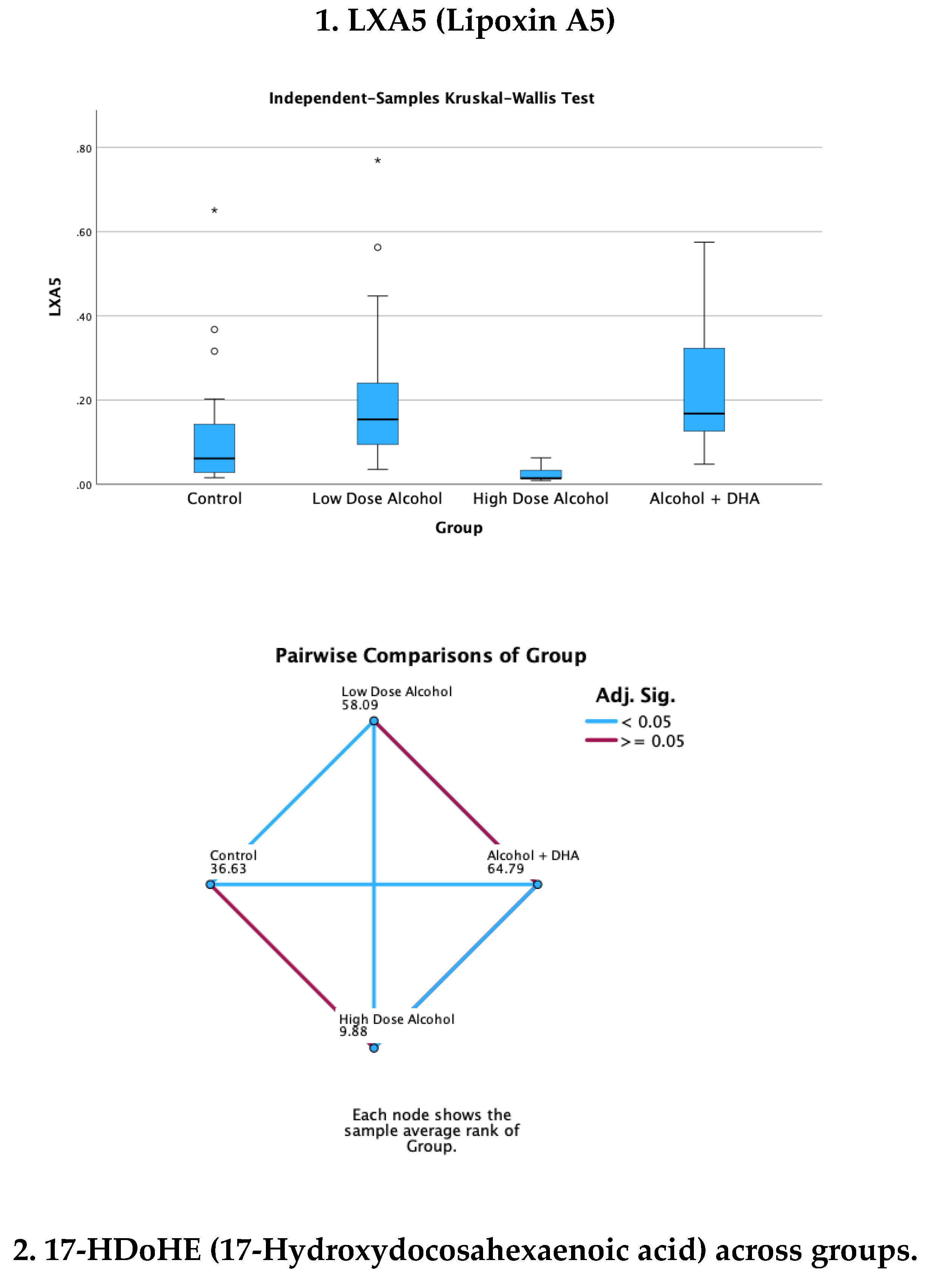

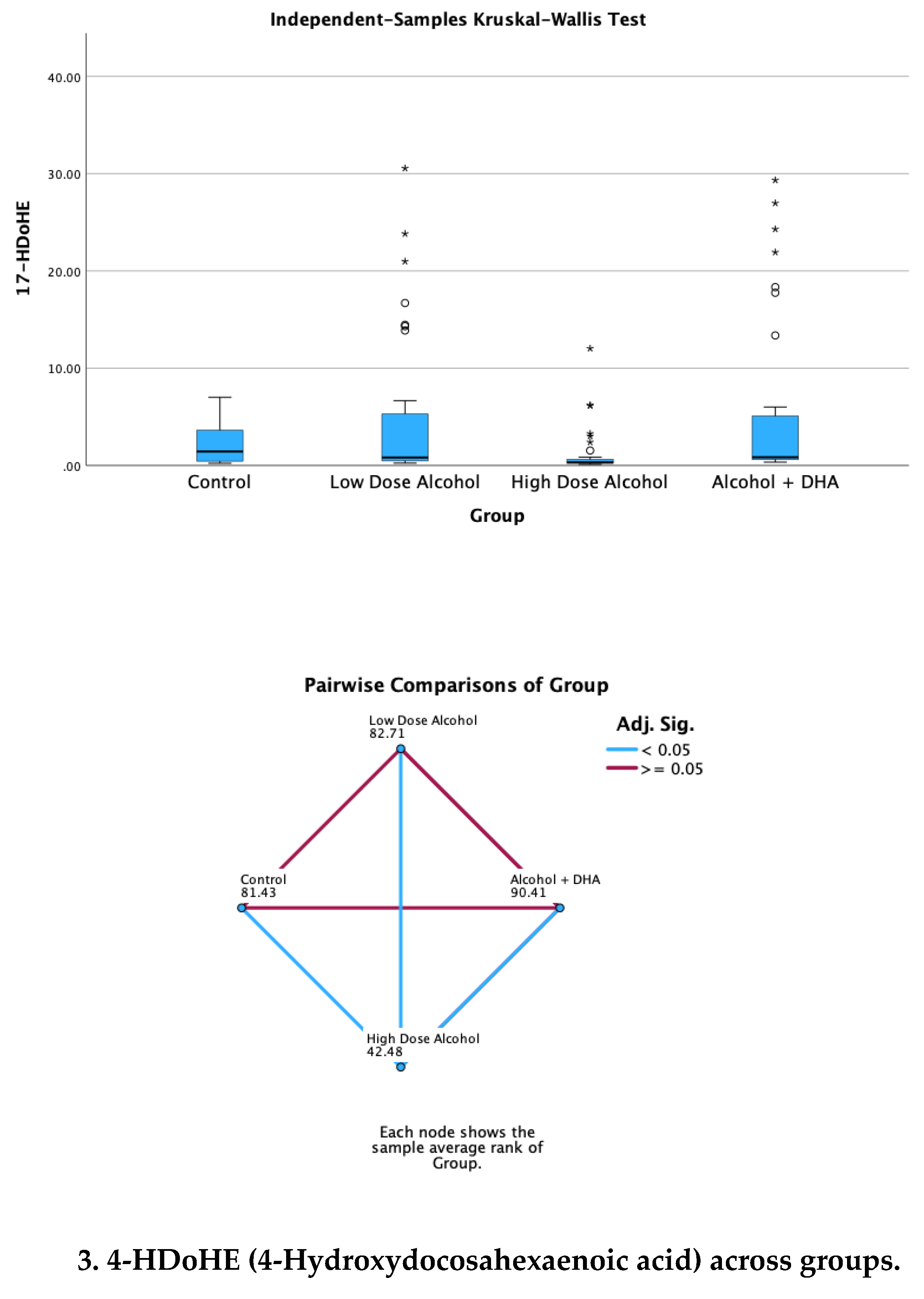

Many cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase-derived pro-inflammation and pro-resolution lipid mediators were analyzed in the pups’ brains in response to alcohol dose and DHA supplementation of the dams. The different brain lipid mediators were compared according to their treatment group and only those mediators with significant difference (p<0.05) when comparing group treatments are presented in this report. These brain lipid mediators included: 1) The pro-inflammation lipid mediators (PILM) viz., leukotriene B4 (LTB4), prostaglandinE2 (PGE2), prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α), thromboxane B2 (TXB2) and 2) The pro-resolution lipid metabolites (PRLM) viz., lipoxin A5 (LXA5), 4-Hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid (4-HDoHE), 17-Hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid (17-HDoHE) and 7R,14S-dihydroxy-docosapentaenoic acid (MaR1n-3 DPA).

The pro-inflammation lipid mediators are derived from the cyclooxygenase pathway (PGE2, PGF2alpha, and TxB2) and lipoxygenase pathway (LTB4). The pro-resolution mediators (LXA4, 4 and 17 HDoHE, and MaR1) are derived from the lipoxygenase pathway.

The mean concentrations of the brain lipid mediator were significantly skewed and their variance was non-homogenous. Thus, the Kruskal-Wallis H test was used to compare the groups based on treatment. Skewness of the data points is not uncommon for this large group of pups being tested independent of analysis technique.

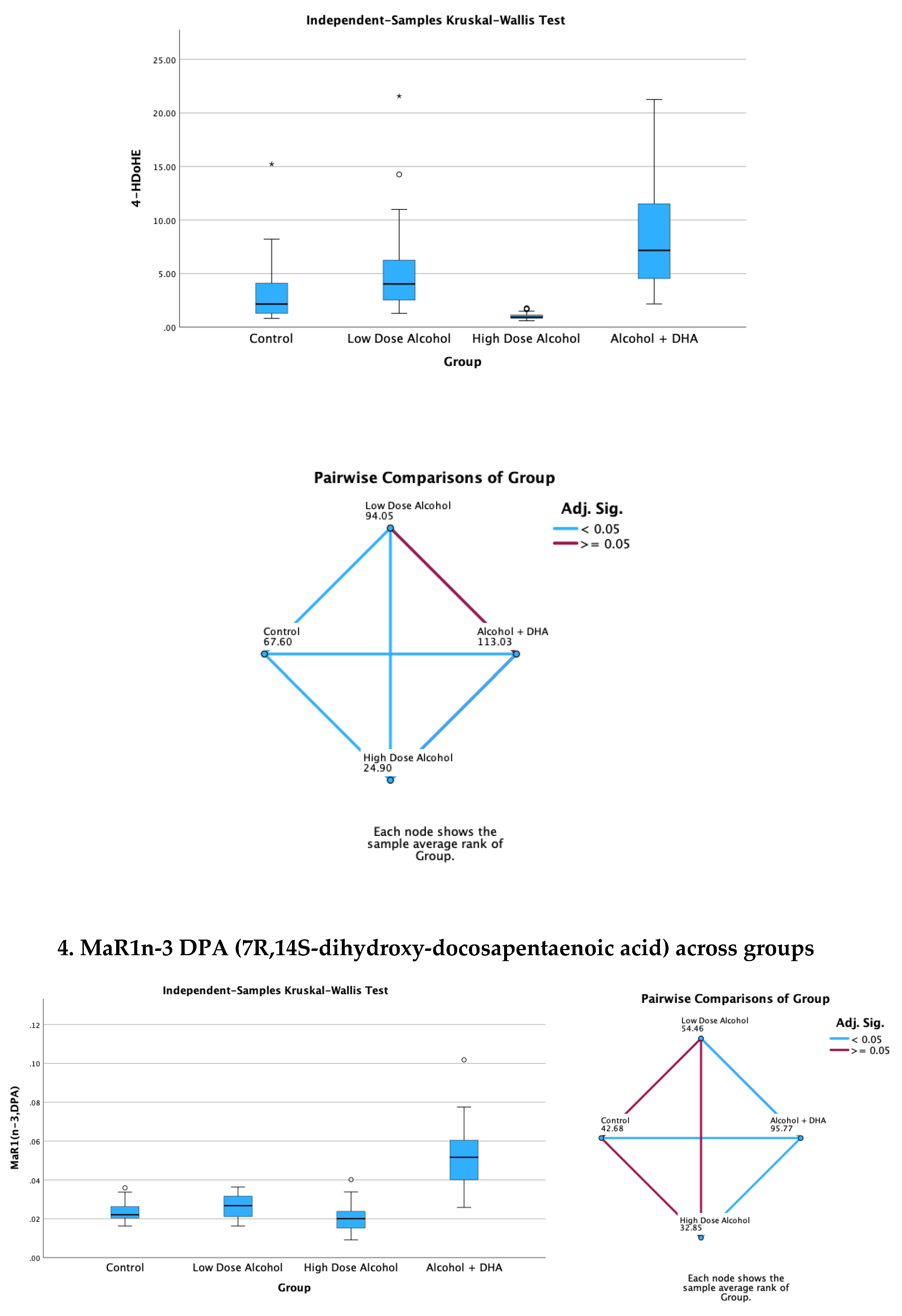

The results of the Kruskal-Wallis H test comparing median brain lipid mediator concentrations based on treatment groups are shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. Degrees of freedom was equal to 3.

(Note: DHASCO, which was the principal source of DHA in the study contains other polyunsaturated fatty acids, as shown in Supplement 1. Thus, the possible contribution of these other fatty acids cannot be excluded from the salutary effects seen by DHA alone. Although the dose of DHA given to the dams was calculated based on the actual content of DHA in DHASCO, the term “DHA” in the study refers to the combined effect of DHA plus other polyunsaturated fatty acids contained in DHASCO).

3.4.1. Pro-Inflammation Brain Lipid Mediators

The effect of alcohol with or without DHA on the pro-inflammation lipid mediators of inflammation viz., LTB4 (Leukotriene B4), PGE2 (Prostaglandin E2), PGF2a (Prostaglandin F2α) and TXB2 (Thromboxane B2) in the fetal rat brain are shown in

Figure 2. All data are in ng/mg protein of pup brain homogenates and presented as median and interquartile range.

Paired comparisons and “p” values were analyzed by the Kruskal-Wallis test with the red line in the figure indicating no significant relationship at p> 0.05 and the blue line indicating a significant relationship at p< 0.05

Figure 2.

The effect of alcohol with or without DHA on the pro-inflammation lipid mediators of inflammation viz., LTB4 (Leukotriene B4), PGE2 (Prostaglandin E2), PGF2a (Prostaglandin F2α) and TXB2 (Thromboxane B2) in the fetal rat brain. All data are in ng/mg protein of pup brain homogenates and presented as median and interquartile range. Paired comparisons and “p” values were analyzed by the Kruskal-Wallis test with the red line in the figure indicating no significant relationship at p> 0.05 and the blue.

Figure 2.

The effect of alcohol with or without DHA on the pro-inflammation lipid mediators of inflammation viz., LTB4 (Leukotriene B4), PGE2 (Prostaglandin E2), PGF2a (Prostaglandin F2α) and TXB2 (Thromboxane B2) in the fetal rat brain. All data are in ng/mg protein of pup brain homogenates and presented as median and interquartile range. Paired comparisons and “p” values were analyzed by the Kruskal-Wallis test with the red line in the figure indicating no significant relationship at p> 0.05 and the blue.

Summary of paired comparisons of pro-inflammation brain lipid mediators based on treatment:

Low dose alcohol group was not significantly lower than control in all the 4 pro-inflammation lipid mediators

High dose alcohol group was significantly lower than Control in LTB4 and PGE2 (

Figure 2)

High dose alcohol + DHA group was significantly lower than Control in LTB4, PGF2α and TXB2

High dose alcohol was significantly lower than low dose alcohol in LTB4.

High dose alcohol + DHA was not significantly different compared to high dose alcohol in any pro-inflammation lipid mediators.

3.4.2. Pro-Resolution Lipid Mediators:

The effect of alcohol with or without DHA on the pro-resolution lipid mediators, viz., LXA5 (Lipoxin A5), 17-HDoHE (17-Hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid), 4-HDoHE (4-Hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid) and MaR1n-3 DPA (7R,14S-dihydroxy-docosapentaenoic acid) in the fetal rat brain are shown in

Figure 3. All data are in ng/mg protein of pup brain homogenates and presented as median and interquartile range.

Paired comparisons and “p” values were analyzed by the Kruskal-Wallis test with the red line in the figure indicating no significant relationship at p> 0.05 and the blue line indicating a significant relationship at p< 0.05

Figure 3.

Effect of alcohol with or without DHA on the pro-resolution lipid mediators, viz., LXA5 (Lipoxin A5), 17-HDoHE (17-Hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid), 4-HDoHE (4-Hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid) and MaR1n-3 DPA (7R,14S-dihydroxy-docosapentaenoic acid) in the fetal rat brain. All data are in ng/mg protein of pup brain homogenates and presented as median and interquartile range. Paired comparisons and “p” values were analyzed by the Kruskal-Wallis test with the red line in the figure indicating no significant relationship at p> 0.05 and the blue line indicating a significant relationship at p< 0.05.

Figure 3.

Effect of alcohol with or without DHA on the pro-resolution lipid mediators, viz., LXA5 (Lipoxin A5), 17-HDoHE (17-Hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid), 4-HDoHE (4-Hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid) and MaR1n-3 DPA (7R,14S-dihydroxy-docosapentaenoic acid) in the fetal rat brain. All data are in ng/mg protein of pup brain homogenates and presented as median and interquartile range. Paired comparisons and “p” values were analyzed by the Kruskal-Wallis test with the red line in the figure indicating no significant relationship at p> 0.05 and the blue line indicating a significant relationship at p< 0.05.

Summary of paired comparisons of resolution brain lipid mediators based on treatment:

Low dose alcohol group was significantly higher than control in LAX5, and 4-HDoHE.

High dose alcohol group was significantly lower than Control in 4-HDoHE and 17-HDoHE.. Alcohol + DHA was significantly higher than Control in LXA5, MaR1n-3 DPA and 4-HDoHE.

High dose alcohol was significantly lower than low dose alcohol in LXA5, 4-HDoHE and 17-HDoHE and versus Control in 4-HDoHE and 17-HDoHE.

High dose alcohol + DHA compared to high dose alcohol alone showed significantly increased LXA5, MaR1(n-3 DPA), and two to three-fold increase in 4-HDoHE (7.163 vs 2.155 ng/mg, p<0.001) and 17-HDoHE concentrations (0.850 vs 0.317 ng/mg, p<0.001) despite the high alcohol dose.

4. Discussion

Inflammation is a major protective response of the body to noxious insults [

1].The initial inflammatory response involves specific cellular infiltrates, e.g., neutrophils, and the release of pro-inflammatory lipid mediators, such as prostaglandins, cytokines, and leukotrienes [

1]. This is soon followed by the cessation of PMN influx, clearance of debris by macrophages, and the elaboration of pro-resolving lipid mediators known as specialized pro-resolution mediators (SPM), e.g., lipoxins, resolvins, protectins, and maresins which evoke potent anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving mechanisms as well as enhance microbial clearance [

1]. SPMs include ω-6 arachidonic acid-derived lipoxins, ω-3 eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)-derived resolvins, protectins and maresins, cysteinyl-SPMs, as well as n-3 docosapentaenoic acid (DPA)-derived SPMs [

1,

17].

In a rat model, our study detected many of the cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase-derived pro-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators in the brain of rat pups chronically exposed to alcohol and DHA during gestation. These included pro-inflammatory lipid mediators such as LTB4, PGE2, PGF2α, TXB2, and pro-resolution mediators such as lipoxin LXA5, MaR1n-3DPA and resolvin precursors, 4-HDoHE and 17-HDoHE (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

The study showed no significant increase in pro-inflammatory lipid mediators concentrations in the low dose alcohol group (1.6 g/kg/day) compared to control likely that because of the low alcohol dose given and the potential salutary effect of olive oil. On the other hand, high dose alcohol (2.4 g/kg/day) without DHA supplementation showed a significant (p<0.005) decrease of the pro-inflammatory lipid mediators, LTB4, PGE2 and TXB2 and a significant decrease in the pro-resolution lipid mediators (LXB4, 4-HDoHE, and 17-HDoHE). Although the expectation is that both brain pro-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators should have increased in response to the alcohol insult, this was not observed in the study which is attributable to significant neuronal degeneration and death that occurred as a result of the prolonged alcohol toxicity. Alcohol has been shown to cause apoptotic neuronal degeneration and death through activation of caspase 3 and 9 [18.19], DNA fragmentation, nuclear disruption [

20], oxidative stress that coincide with the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β and TGF-β [

21], enhanced acetylcholinesterase activity and increased oxidative-nitrosative stress [

22].

Although high dose alcohol alone caused a significant decrease in both the pro-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators in the pups’ brain, the opposite was observed with alcohol + DHA supplementation. Despite the high alcohol dose, many of the pro-resolution lipid mediator levels were significantly increased with high alcohol dose combined with DHA. These included 1) a significant increase in LXA5 and MaR1n-3DPA, 2) a significant three-fold increase in 4-HDoHE and 3) a significant increase in 7- HDoHE concentration (

Figure 3). Thus, the ability of DHA to increase brain pro-resolution lipid mediators is compelling evidence of DHA’s salutary role in mitigating the adverse effect of high alcohol dose on the fetal brain.

Resolvin precursors, in particular, were enhanced by DHA supplementation in the alcohol exposed fetal pups. Resolvin D-series are produced from the oxidation of DHA by 15-lipooxygenase to 17-hydroperoxydocosahexaenoic acid and metabolized further into resolvin Ds. Resolvin E series are produced from EPA by acetylated cyclooxegenase-2 or cytochrome P450 [

23]. Resolvin was discovered by Serhan and his team in their search for potential endogenous bioactive compounds derived from omega-3 fatty acids [

24]. The pro-resolution and anti-inflammatory effects of resolvins are predominately achieved through specific G-protein coupled receptors [

25]. Resolvins can inhibit microglia activation and reduce the proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, iNOS, and nitric oxide, through the MAPK, NF-κB, PI3K/Akt, and caspase-3 signaling pathways [

25]. Resolvin has many actions in resolving inflammation-mediated diseases and is extensively discussed in several review articles [

23,

24,

25,

26].

In a previously published report [

27], we measured cytokine levels in the dams which showed higher pro-inflammatory cytokines (principally Interleukin-1β, Interleukin-12p70 and TNF-α) in the alcohol-exposed pregnant rats compared to Control, although the difference was not statistically significant due likely to large variance of the mean concentrations and the small sample size. However, the literature has well shown an increase in brain cytokines from alcohol insult secondary to microglia activation [

28] and as increase in the brain cytokines, TNF-α, IL-1β and TGF-β in alcohol exposed rat pups [

21].

DHA is one of the important long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA) in the body. It is a major component of the pro-resolution lipid mediators of inflammation [

17] and an essential element in the growth and development of the brain and retinal development in infants and normal brain function in adults [

29,

30]. DHA deficiencies are associated with fetal alcohol syndrome, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, cystic fibrosis, phenylketonuria, unipolar depression, aggressive hostility, and adrenoleukodystrophy [

30].

Deficiency in DHA can occur in the fetus secondary to a number of conditions. Prematurity is a significant cause since the premature infant cannot sufficiently synthesize DHA, and maternal source is necessary [

31]. LCPUFA is increasingly transferred from mother to fetus late in pregnancy, reaching peak accretion rates between 42 –75 mg/d at 35 – 40 weeks of gestational age [

32,

33]. Thus, premature delivery of the infant results in lower levels of DHA and other important PUFA due to insufficient transfer of these fatty acids from the mother. In maternal alcohol disorder, deficiency of DHA in the fetus is further aggravated since alcohol depletes DHA by esterification of DHA into FAEE (fatty acid ethyl esters), which is excreted in the urine as an ethyl ester [

34]. High alcohol intake during pregnancy has been associated with DHA deficiency in maternal plasma [

35] and consequently low placental transport of DHA to the fetus.

Prenatal alcohol exposure in developing rat brain appears to decrease PUFA concentrations of membrane phospholipids [

36,

37] and the deficiency of DHA in the fetus has been shown to result in poor cognitive and behavioral performance [

33,

38,

39,

40,

41]. As an intervention, dietary supplementation of pregnant women with n-3 PUFA appears to increase DHA levels, reduce placental oxidative stress, and enhance placental and fetal growth [

42,

43]. Postnatal omega-3 supplementation of pups exposed to prenatal alcohol also partially reduces oxidative stress and reverses long-term deficits in hippocampal synaptic plasticity [

44,

45].

Our primary aim in this study was to determine the salutary role of DHA on the brain lipid mediators of inflammation in rat pups prenatally exposed to alcohol using olive oil as the lipid control for DHA. The use of olive oil led to an unexpected finding of increased birth weight in the alcohol exposed pups [

27]. The increase in birth weight could have resulted from calories provided by alcohol and olive oil since the caloric content of olive oil is 8.5 calories per gram and 7 calories per gram in alcohol. Similarly, the salutary effect of olive oil on the pups’ birth weight was more prominent in high dose compared to low dose alcohol groups which could be due to the higher caloric load in high dose alcohol group. The pups’ birth weight was also higher in the high dose alcohol/olive oil group compared to the high dose alcohol/DHA group possibly due to potential DHA loss from DHA esterification with alcohol [

34]. It is also possible that this may be the effect of increased visceral fat biosynthesis and accumulation in response to the interaction of alcohol and high saturated fat content in olive oil [

46].

Hydroxytyrosol (HT) is a primary polyphenol in olive oil with anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties. Hydroxytyrosol has both lipophilic and hydrophilic properties, allowing it to be absorbed readily and exhibit cytoprotective properties by scavenging free radicals and limiting inflammation [

47,

48]. Maternal HT supplementation has also been linked to improved neurogenesis and cognitive function by alleviating oxidative stress and improving mitochondrial function in the hippocampi of the offspring exposed to non-alcohol-related prenatal stress [

49,

50]. Maternal HT supplementation has also been shown to enhance mean birth weight in animal studies [

49]. Thus, the potential of olive oil supplementation to increase the birth weight of infants born to alcoholic mothers is worth exploring. However, unlike DHA, olive oil in combination with alcohol in our study did not improve the concentrations of pro-resolution lipid mediators in the brain of the alcohol-exposed pups (

Figure 3) and current evidence from the literature is also insufficient to suggest any benefit of olive oil in alleviating the inflammatory effects of alcohol.

Limitations

There are some limitations in the study: 1) Information on biomarkers of degeneration, e.g., caspase 3 and 9 activation, DNA fragmentation, nuclear disruption, and pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and TGF-β, are desirable in providing additional evidence of the salutary function of DHA on the fetal brain. These biomarkers can be explored in future studies. 2) Unfortunately, we could not determine the sex of the pups because of inaccurate delineation of the anogenital distance for sex determination in very small pups. Besides, the difficult and relatively inaccurate process of sex determination would have taken an inordinate time with 160 pups to examine and would have interfered with a primary intent of the protocol that the sacrifice of all the dams and pups should be at approximately the same time so that the period of exposure to their treatments (alcohol and/or DHA) would be similar. 4) The present study of brain lipid mediators in the pups is also only the first step in determining the salutary effect of DHA in mitigating the adverse effects of alcohol on the fetal brain. An outcome study demonstrating an improvement in pups behavior is needed, as well and we are currently undertaking such a study.