Plain language summary: Neuropathological studies revealed that the molecule amyloid-β causes inflammation in the brain of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, involving the immune cells called macrophages. Current therapies of Alzheimer’s disease with the monoclonal antibodies Aducanumab or Lecanemab bind to but do not clear amyloid-β from the brain and do not inhibit the inflammation. This study shows that the molecule called TPPU, which inhibits soluble epoxide hydrolase, together with certain polyunsaturated fatty acid molecules, protect AD macrophages against inflammation and thus may clear amyloid-β from the brain. Another soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitor called EC5026 is more suitable for human therapy than TPPU and should be tested in a clinical trial in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. These experimental drugs complement other approaches for degradation of amyloid-β.

1. Introduction

Aducanumab and Lecanemab are therapeutic monoclonal antibodies to amyloid-β 1-42 (Aβ) that increase the clearance of soluble and insoluble Aβ in the brain of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients and may, although controversially, slow AD progression [

1,

2,

3]. These anti-Aβ monoclonal antibody therapies are associated with amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIAs), characterized by brain edema and/or hemorrhagic strok,e [

3,

4,

5], which are caused by Aβ-induced myeloid (monocyte/macrophage (MM)) vasculitis [

6] and blood-brain barrier (BBB) damage. Therefore, effective and safe therapy of AD remains an unresolved problem.

To resolve a more generally safe approach AD therapy, we have reviewed existing therapeutic studies and investigated novel approaches. We demonstrate that monocyte/macrophages (MMs) are critical in brain clearance of Aβ but fail to clear Aβ in AD patients. Fortunately, the defects in transcriptome, glycome and functions of AD patients’ MMs are known from previous studies and illuminate four possible approaches to effective therapy of AD through biochemical modulation of sGAS, NFκB, IRF3, and EP4 signaling, as follows:

1) cGAMP- STING synthase (cGAS) pathway is activated in AD and other diseases by cytosolic DNA, which activates STING and induces pro-inflammatory signaling by the transcription factors NFκB and IRF3 [

7,

8,

9]. cGAS signaling is important in neurological diseases (Parkinson’s disease (PD), AD [

10], amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [

11]), heart failure, chronic inflammatory diseases (pancreatitis), and cancer. The cGAMP-STING signaling is blocked by the STING inhibitor H-151 [

7].

2) Aβ induces inflammation and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in macrophages through NFκB and IRF3 signaling, which are inhibited by the bioactive signaling molecules epoxides of fatty acids (EpFAs) [

12]. EpFAs are formed by cytochrome P-450 enzymes from polyunsaturated ω-3- and ω-6 fatty acids (PUFAs). EpFAs regulate macrophage inflammation but are destroyed by the soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) [

13]. The sEH enzyme is inhibited by the sEH inhibitors (sEHI) TPPU and EC5026.

3) The signaling through prostaglandin EP2 receptor 4 (EP4) decreases energy, neuronal plasticity and memory in a mouse model of ageing and likely in AD. Blockade of peripheral myeloid EP4 signaling is sufficient to restore cognition in aged mice. [

14].

Thus, three approaches are potentially therapeutic in AD: a) inhibition of cGAS by a STING inhibitor (e.g. H-151); b) blockade of sEH by an sEH inhibitor (sEHI), such as TPPU (not approved for human studies) or EC5026 (approved for human studies), c) inhibition of inflammatory signaling by an inhibitor of the prostaglandin receptor EP4 (EP2R4) [

14] or, possibly, EP2 (EP2R2) [

12].

In this study, we clarify the critical role of monocyte/macrophages (MMs) in the immunopathology of AD patients, including the patients on monoclonal antibody therapy (

Section 3.1), analyze the defects in macrophage Aβ clearance and transcriptome (

Sections 3.2 and 3.3), and show possible repair of these defects using the epoxides of polyunsaturated fatty acids (EpFAs), the inhibitors of soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEHIs) (e.g. TPPU) and the cGAS-STING pathway (the STING inhibitor H-151) (

Sections 3.4 and 3.5). These therapeutic approaches increase Aβ degradation in macrophages and inhibit the inflammatory vasculitis, and are potential approaches to therapy of AD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

We examined the effects of epoxy fatty acids (EpFAs) on the transcriptome of peripheral blood macrophages generated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of two AD patients (patient #1, age 68 years, male gender; mini-mental state examination (MMSE) 21 points; and patient #2, age 71 years, male gender; MMSE 26 points).

2.2. Macrophage Culture and Treatments

We isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) by Ficoll-Hypaque technique and cultured them in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (IMDM) containing 10% autologous serum for 1 to 2 weeks until CD68+ macrophages developed. We added the compounds in a DMSO solution at the final concentration 1 μM EpFAs, 100 nM TPPU, or H151 (100 ng/ml). We confirmed macrophage type by staining with anti-CD68 antibody (monoclonal antibody against human macrosialin in human monocytes, macrophages, and myeloid cells; clone KP1, DAKO, Inc) and macrophage phenotype as pro- inflammatory in most patients by high staining with anti-CD80 and low staining with anti-CD163.

2.3. RNA Sequencing and Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from macrophage cultures using Quick RNA Miniprep kit (Zymo Research, Inc.). Final libraries were generated from total RNA using KAPA mRNA Hyper kit, and quantified and sequenced on NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina, Inc). After removing low-quality reads, the data were aligned to the human genome GCHr38 using STAR (v2.6) and count data were normalized using DESQ2’s median of ratios method. We compared the effects of EpFAs in normalized counts of macrophage samples and performed a supervised graphical analysis of individual genes of interest, according to the previous method [

15].

2.4. Chemicals

The methyl esters of EpFAs and the sEH inhibitor TPPU were prepared in the laboratory of B. Hammock [

16], according to the previously described synthesis methods [

17,

18]. Lipophilic fatty acid epoxides and the enzyme inhibitors were added in DMSO (less than 1 percent final volume, and DMSO was used as a control.

3. Results

3.1. Monocyte/Macrophages (MMs) Transport Amyloid-Β To Vessels Causing Vasculitis, Which Underlies Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities (ARIAs) and Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy (CAA)

According to the Aβ hypothesis, the deposition of amyloid-β

1-42 (Aβ) in plaques, neurons, and blood vessels in the brain is the cause of AD neuropathology [

19]. AD brain contains oligomeric and soluble Aβ in neurons and apoptotic macrophages, and fibrillar Aβ in plaques and blood vessels [

20]. The deposition of Aβ has a “biochemical phase” with Aβ aggregation, phosphorylation of tau, and cell-to-cell propagation of Aβ and p-tau, a “cellular phase” with the participation of “microglia” and astrocytes [

21]. Aβ deposition is followed by the” inflammatory response phase” with vasculitis caused by blood-borne MMs, which transport Aβ from plaques to vessels [

20].

3.3. Defects of Macrophage Transcriptome Underlie Macrophage Failure Of Brain Clearance

As inflammatory macrophages are pathogenic in chronic inflammatory disorders, increasing Aβ degradation and inhibiting inflammation are therapeutic mechanisms against AD. The anti-amyloid antibody chimeric antigen receptor epitope-expressing macrophages (CAR-Ms) have been shown to degrade Aβ [

26]. Macrophages of AD patients are defective in uptake of fibrillar and soluble Aβ, and in degradation of intracellular Aβ [

20]; and they display a pro-inflammatory phenotype with increased endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and defective phagocytosis of Aβ [27).

The functional defects of AD macrophages are related to the down-regulation of the transcripts of several pathways: a) OX-PHOS energy enzymes; b) the enzymes degrading Aβ, i.e. membrane metalloendopeptidase (MMSE), insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE), angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE); and c) the enzymes in the ubiquitin-proteasome system E1, E2, and E3; and to the up-regulation of inflammatory cytokines [

15].

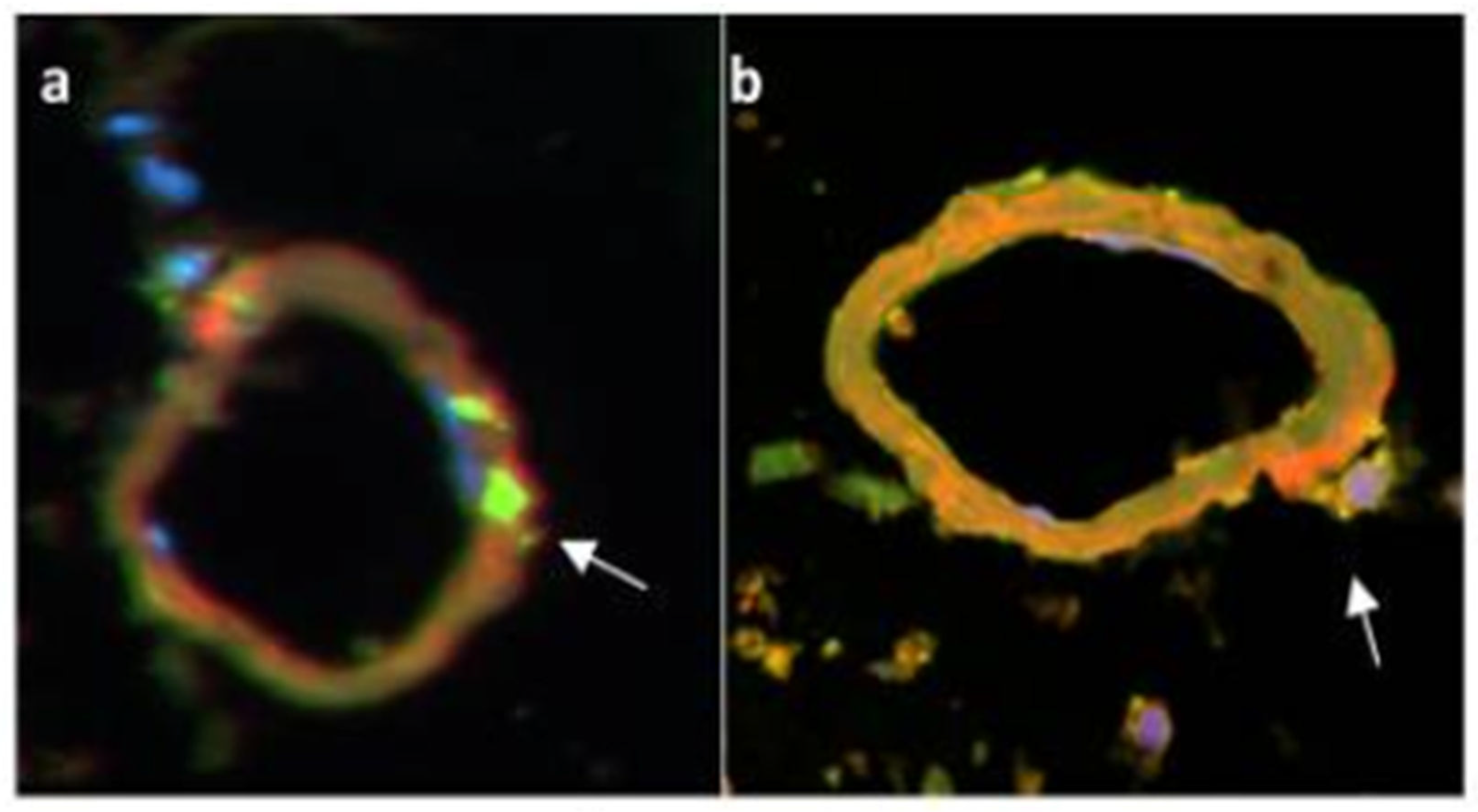

3.2. Amyloid-β Degradation in the AD brain Fails Due to the Transcriptomic Defects in AD Patients’ Monocyte/Macrophages

MMs are critical for brain clearance of Aβ in health but AD patients’ macrophages fail in degradation. In the AD brain [

15,

22], MMs are attracted by chemokines to Aβ plaques, exit vessels (green/CD68) [

22] (

Figure 1a), invade Aβ plaques, upload but do not degrade Aβ (yellow) [

20], return to vessels, undergo apoptosis and release Aβ (red) into vessels (Figure 1b), causing CAA and BBB damage resulting in a failure of brain nutrition and protection [

15,

20,

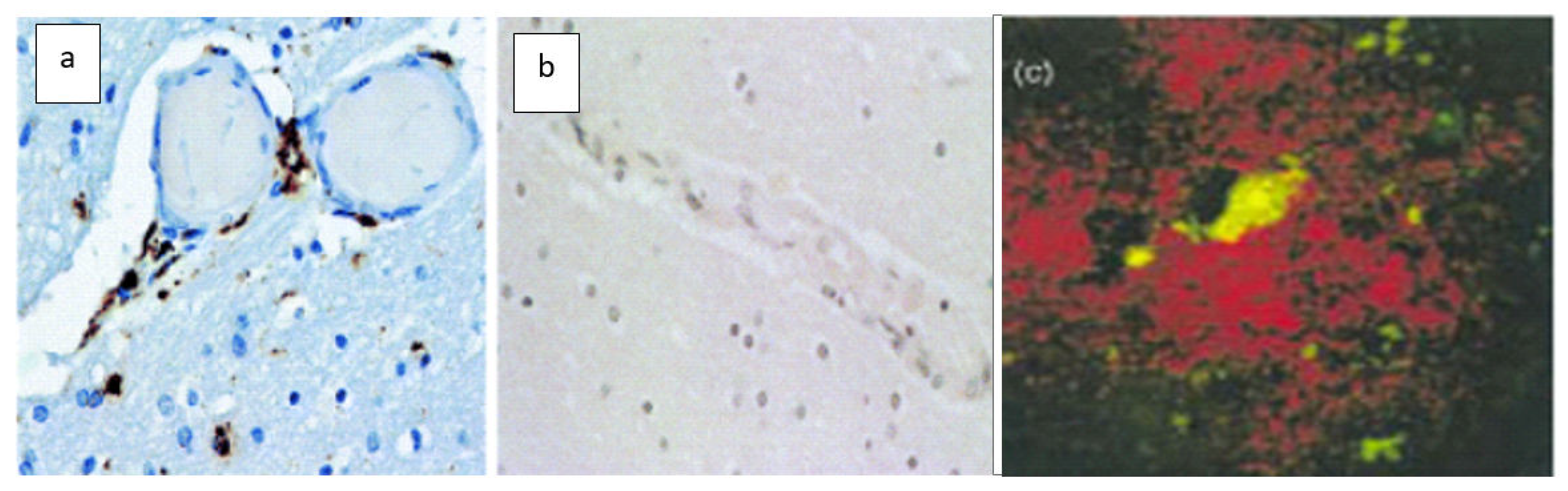

22]. MMs are blocked from brain emigration at the blood-brain barrier (BBB) by gross distention with Aβ. The brain tissues of AD patients show macrophages in perivascular spaces (

Figure 2a) and Aβ plaques (

Figure 2c), in comparison, the brain tissues of a patient with epilepsy do not show perivascular macrophages (

Figure 2b) [

22]. MMs also attach and upload Aβ from neurons [

20].

The anti-amyloid-β monoclonal antibodies Aducanumab and Lecanemab increase macrophage clearance of Aβ plaques and macrophage transport of Aβ to vessels but do not increase Aβ degradation, leading to vasculitis, CAA and ARIAs. In a patient treated by Lecanemab, the neuropathology showed histiocytic (macrophage-lineage) vasculitis [

6]. Anatomical studies in mice, rats, and primates show microglia engulfing Aβ fibrils [

23]. In the human brain with AD [

20,

22], and in the brain of a patient treated with monoclonal Aβ antibody Lecanemab [

6], the infiltrating cells are blood-derived CD68+ myelomonocytic cells. The plaques are infiltrated by CD68

+ Aβ

+ (yellow) macrophages ingesting Aβ (red), whereas the microglia surrounding the plaques are negative for Aβ (CD68

+ Aβ

- (green))

(Figure 2c). The AD brain contains insoluble Aβ in the plaques and soluble Aβ in vessels. Thus, both cellular and humoral mechanisms are necessary for brain clearance: soluble Aβ is cleared by intramural periarterial drainage (IPAD) and drainage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) into cervical lymph nodes; insoluble Aβ is cleared by macrophages. However, the intramural route is likely obstructed by Aβ released by apoptotic macrophages, as well as by immune complexes after monoclonal antibody immunotherapy and the complexes with anti-Aβ autoantibodies [

24,

25].

3.4. Epoxides of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (EpFAs) Repair the Macrophage Transcriptome in Energy Enzymes, Aβ degradation Enzymes, and Cytokines

Clinical use of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in AD therapy with preference for ω-3 over ω-6 PUFAs in seafood has a long history [

28]. The clinical effects of PUFAs against cognitive decline extend beyond the benefits of cholinesterase inhibitors [

29]. To clarify the beneficial mechanisms of PUFAs, we investigated whether the mechanisms arise in part through the epoxide metabolites of PUFAs (EpFAs). EpFAs are lipid mediators [

30], which act

in vivo by modulating the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress pathway to reduce inflammation and nociceptive pathophysiology toward homeostasis. The epoxides of ω-3 fatty acids are anti-inflammatory and more stable than those of ω-6 fatty acids.

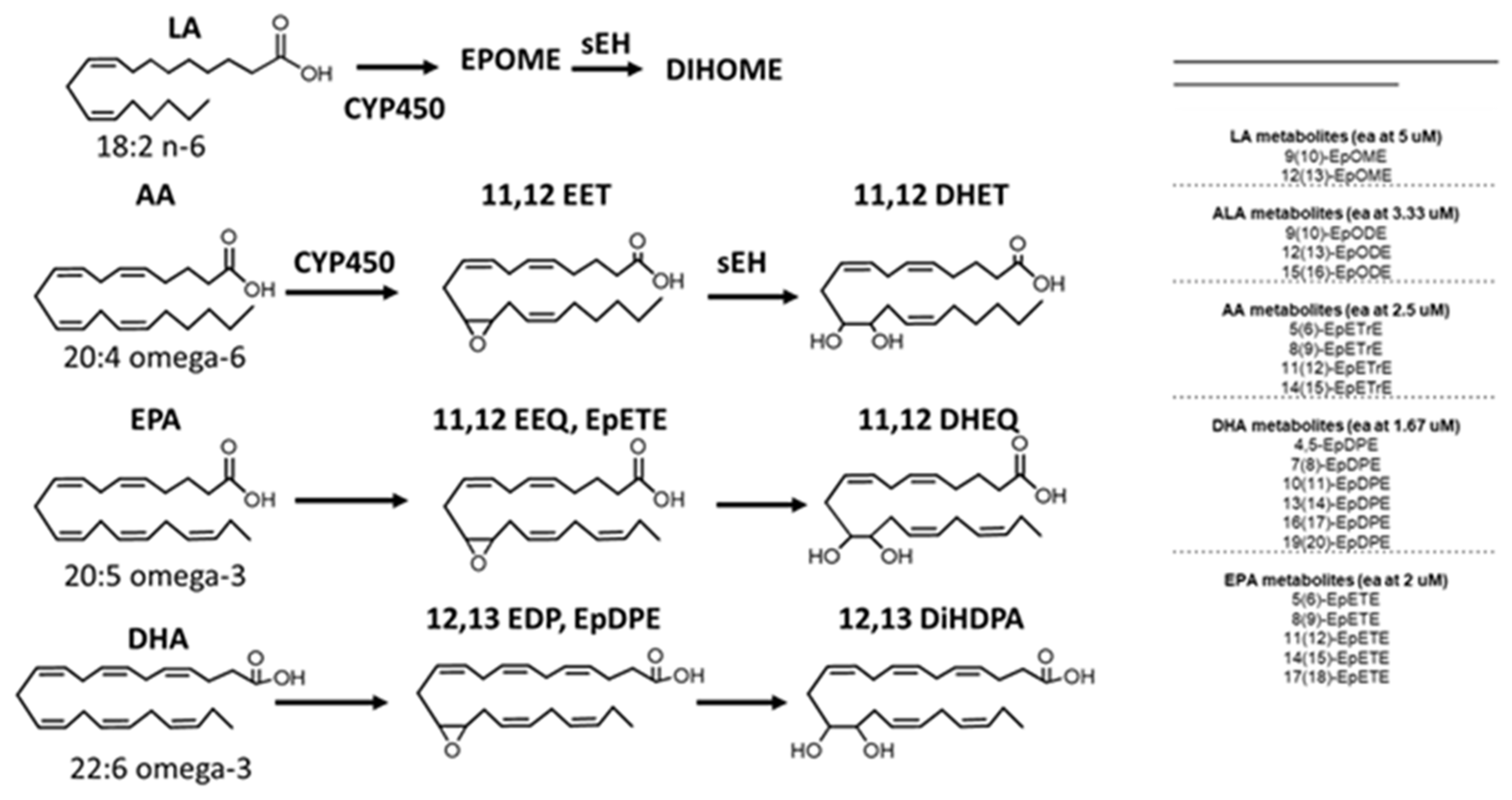

In vivo, ω-3 fatty acid supplementation may alone modulate ER stress [

31,

32]. The epoxides of a) arachidonic acid (ARA) called EETs, b) the ω-3 fatty acid eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) called epoxyeicosatetraenoic acids (EEQs), and c) epoxydocosapentaenoic acids (EDPs) from the ω-3 fatty acid DHA are metabolized by the soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) to more polar and usually inactive diols [

30,

33] (

Figure 3).

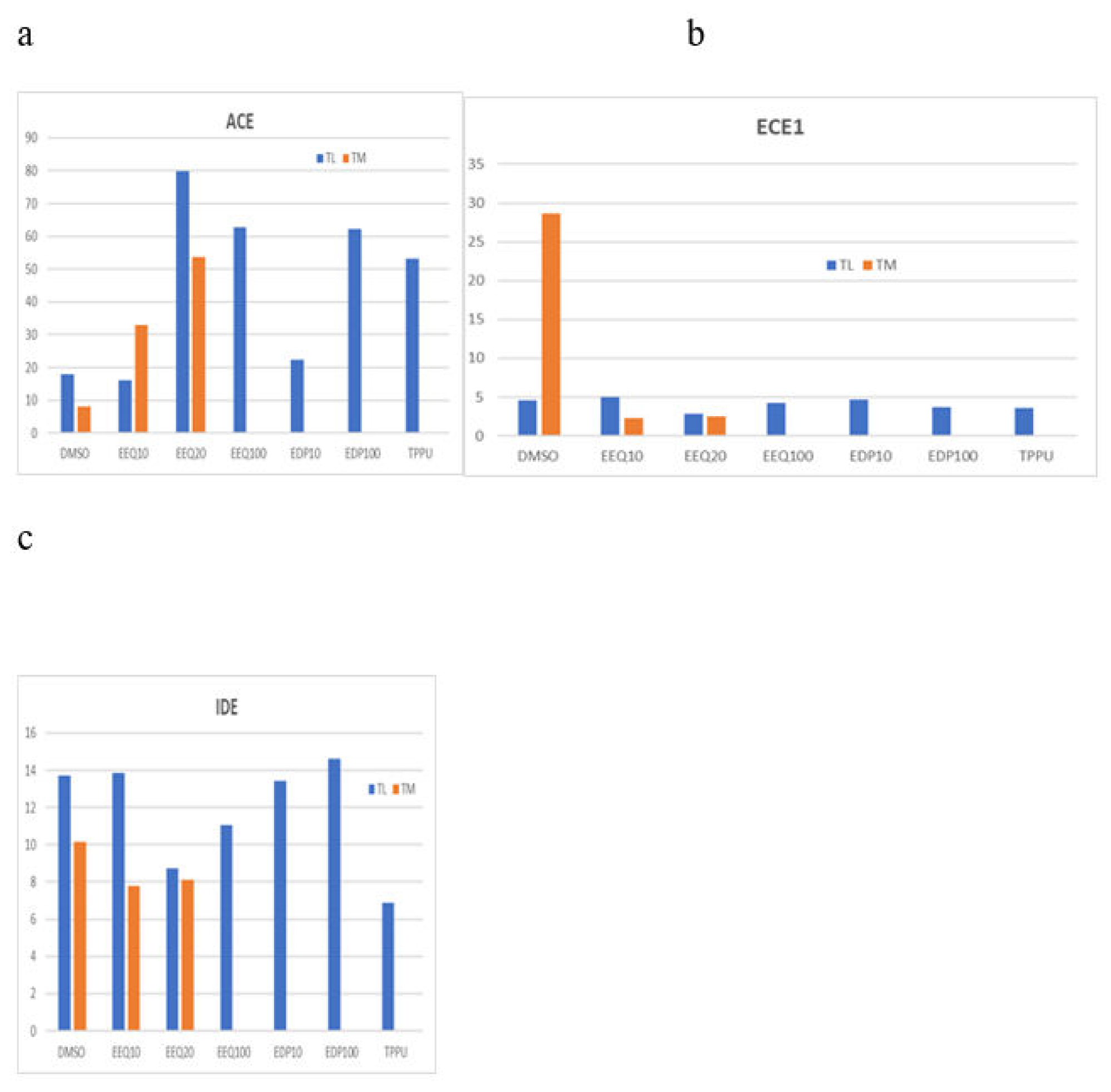

We treated macrophages from two AD patients using the EpFAs and analyzed the transcriptome. The epoxides EEQ, EDP, as well as the sEH inhibitor TPPU, strongly increased the transcripts of the Aβ-degrading enzyme

ACE (Figure 4a). The epoxides EEQ, and EDP, regulated the transcripts of granzyme B and inflammatory cytokines

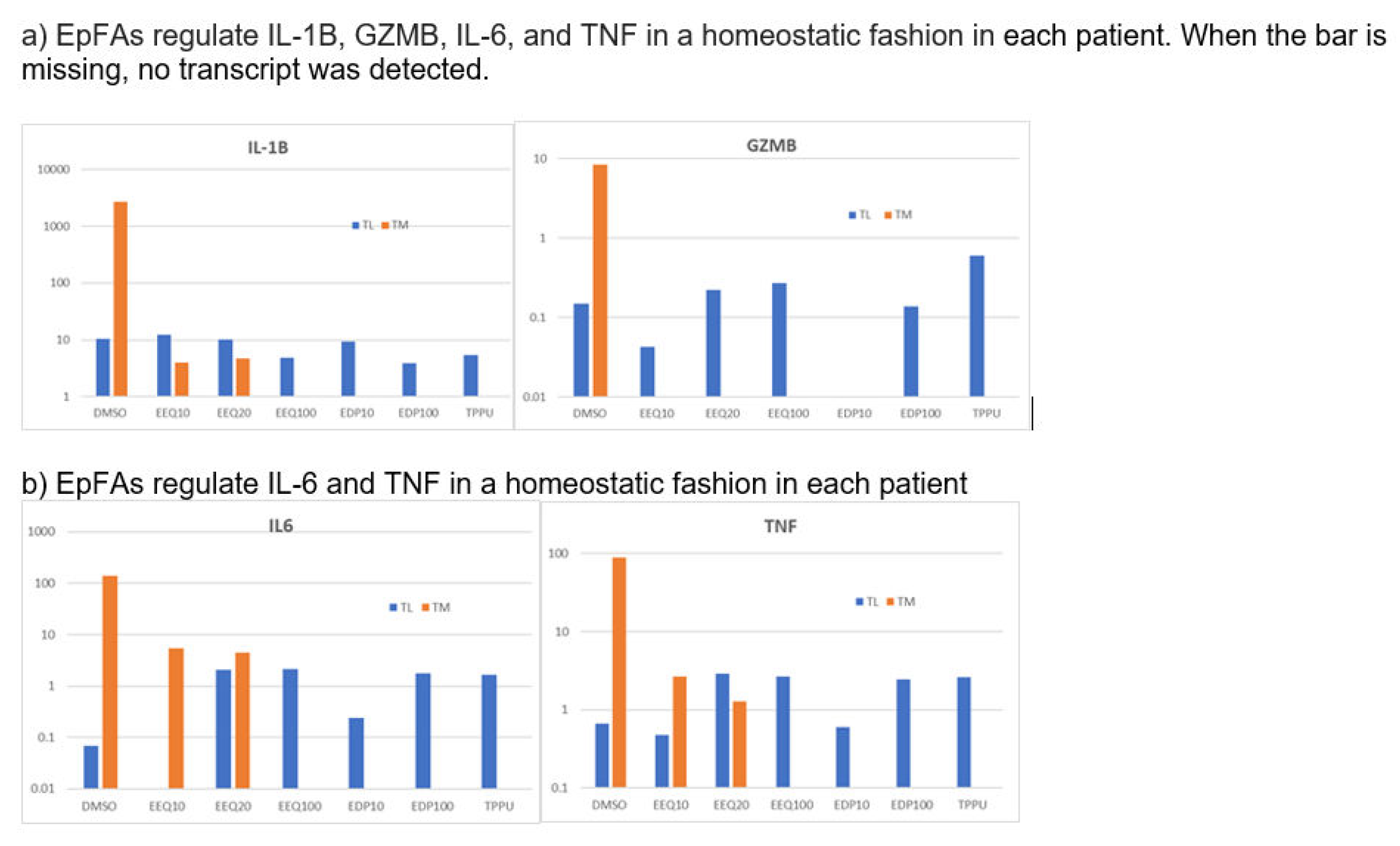

IL1B, IL-23A, IL-6, and TNF in a homeostatic fashion (down-regulated high transcripts and up-regulated low transcripts) (

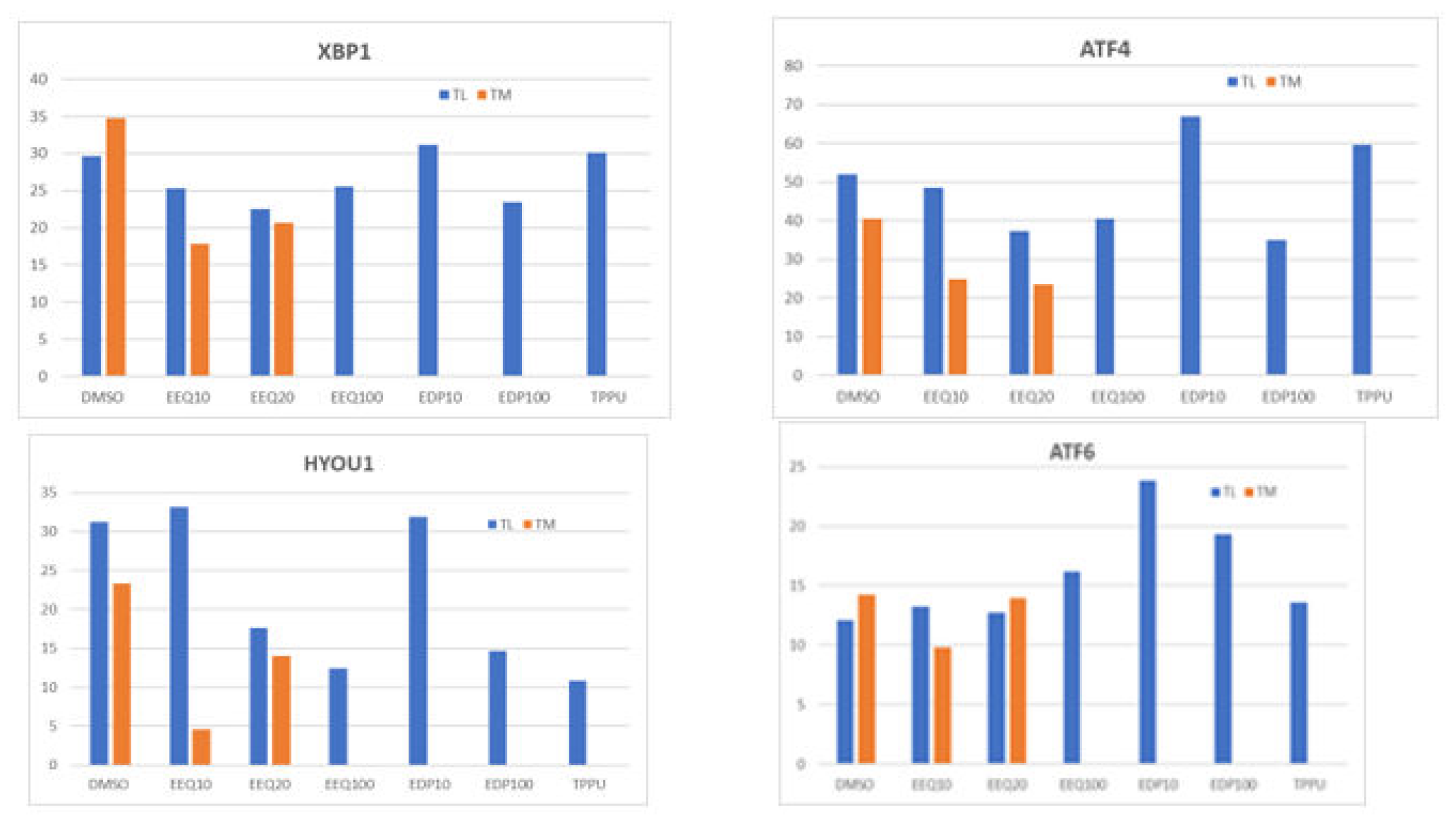

Figure 5). The regioisomeric epoxides EDP up-regulated ATF4 and ATF6, which activate unfolded protein response (UPR) in folding enzymes, chaperones and endoplasmic reticulum associated degradation of denatured proteins (ERAD) (

Figure 6).

3.5. EPFAs together With The Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase Inhibitor TPPU or the STING inhibitor Increase Uptake and Degradation of FITC-Amyloid-β in AD Macrophages

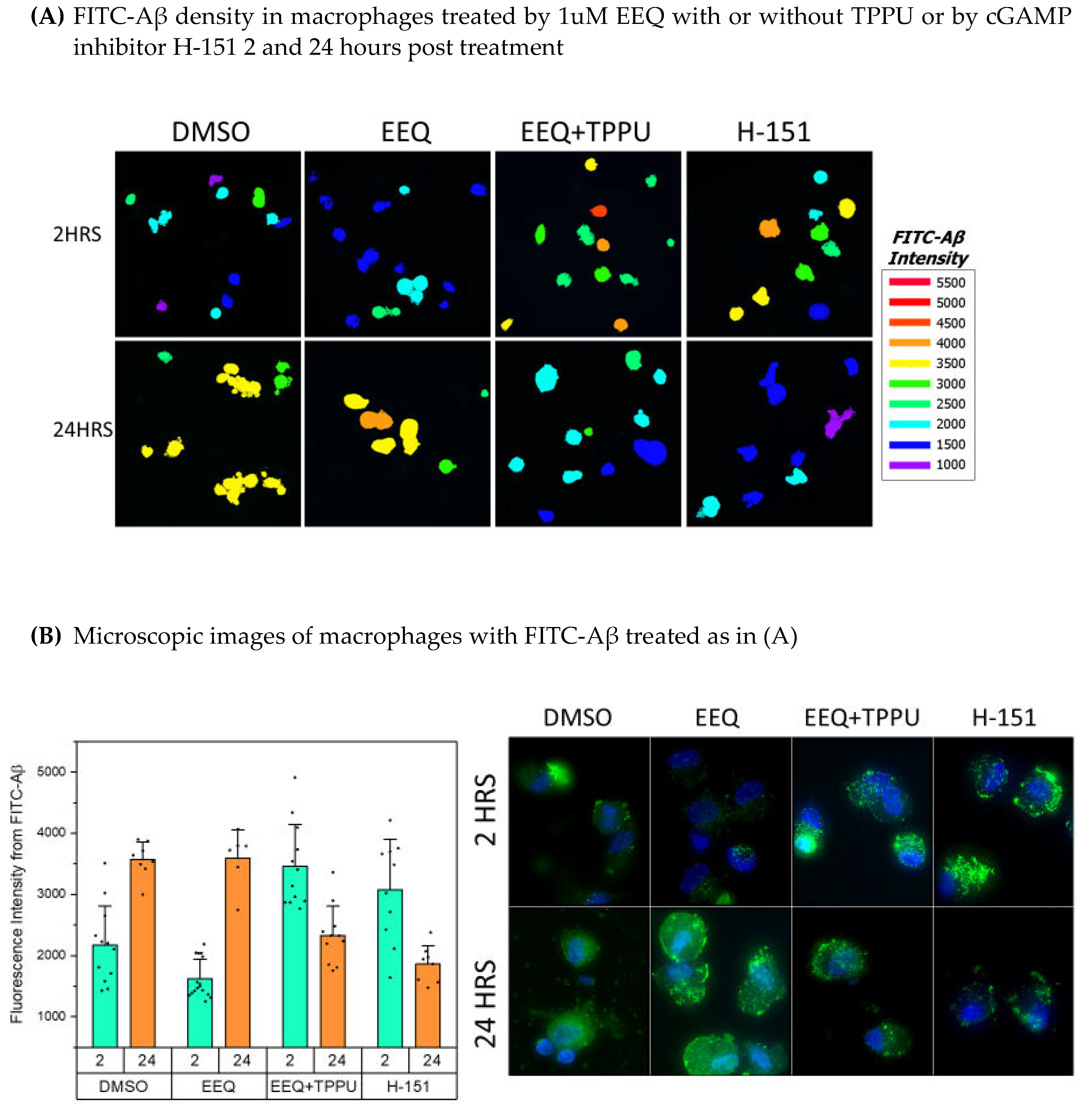

We tested the effects on macrophage uptake of FITC-Aβ of 2-hour and 24-hour treatments with EpFAs together with the sEH inhibitor TPPU or the cGAMP/STING inhibitor H151 and showed the effects according to the mean difference at 2 hours and 24-hours. The 2-hour Aβ upload in macrophages was significantly (P< 0.0000) increased (in descending order) by a) H-151, and b) EEQ + TPPU vs. DMSO. The 24-hr residual Aβ was significantly decreased by a) EEQ +TPPU, and b) H-151 vs. DMSO (Figure 7).

3.6. Aβ is Transferred From Plaques To Vessels Despite Aducanumab therapy In the Yale study [34], the Figure 2 Shows Overall Reduction of Aβ in the Brain Of A Patient Treated By Aducanumab vs. The Brain of An Untreated Patient, But Also The Presence Of Amyloid Angiopathy In Both The Treated And The Untreated Brain. When Adjusted for the Higher Magnification In The Figure 2a vs. Figure 2b, the Deposits Are Comparable In Both Brains. These results Are Consistent With Transfer Of Aβ From The Plaques To Vessels Despite Aducanumab Therapy and the Need for Aβ degradation.

4. Discussion

4.1. Polyunsaturated fatty Acids Protect The Brain By Increasing The Epoxides Of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (EpFAs), which Inhibit Macrophage Mechanisms Of Vascular Complications. A soluble epoxide Hydrolase Inhibitor Is Mandatory To Protect Against EpFA Degradation By Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase

In our previous study, a nutritional supplementation program delivering ω-3 fatty acids DHA and EPA together with anti-oxidants in the commercial Smartfish

R drink protected the cognition of patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) against mental decline beyond that provided by cholinesterase inhibitors [

35] but the patients continued to decline, showing that omega-3 supplementation alone is not a curative approach [

36].

PUFA supplementation increases the blood EpFAs in multiple studies [

37]. Here, we demonstrate that EpFAs, especially EEQ and EDP derived from ω-3 fatty acids, modulate the transcriptome and increase the clearance of Aβ by macrophages. EEQ upregulates in macrophages the Aβ degrading enzyme ACE and energy molecules [

10] and regulates the inflammatory cytokines and markers of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in homeostatic fashion. The 2-hour up-loading of FITC-Aβ in macrophages is accelerated by EEQ with TPPU or by H-151 and the degradation of FITC-Aβ is strongly increased at 24 hours by these molecules (

Figure 7).

EpFAs up regulate the transcripts of enzymes involved in cellular energetics, which are necessary for phagocytosis and migration of macrophages [

31]. The effects of these EpFA mechanisms are therapeutic by a) increasing Aβ degradation, which alleviates Aβ transport into vessels, CAA, and damage to the BBB, and b) decreasing inflammatory cytokines, which inhibits vasculitis. The ω-3 positions of PUFAs are more rapidly epoxidized by cytochrome P450 enzymes than other regioisomers of either ω-3 or ω-6 PUFAs and the omega 3 epoxides are the most resistant regioisomers to hydrolysis by the sEH.

4.2. Practical Use Of The Molecular Inhibitors And Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids In Therapy of AD

Several studies have indicated that sEHIs used along offer promise in the treatment of a number of chronic neurological diseases [

38,

39,

40,

41]. Following their discovery in the 1970’s and early characterization, the first clinical targets were cardiovascular pathologies. sEHIs alone, presumably by increasing EpFAs, reduce vascular inflammation, atherosclerosis, and hypertension, which may protect cerebral vasculature from AD-associated damage. Our study suggests that, in addition to these vascular effects, the sEHI inhibitor TPPU in synergy with EpFAs has a direct positive AD effect on the disease through increased uptake of Aβ at 2 hours and completed degradation of Aβ at 24 hours. This is also produced by the STING inhibitor H-151. In an ageing mouse model, the restoration of cellular bioenergetics through inhibition of the prostaglandin E

2 receptor 4 (EP4) signaling in myeloid cells restored cognition [

14]. Therefore, the combined inhibition of both sEH and EP4 in macrophages of AD patients should be tested in a future clinical trial, as has been examined in cancer [

42].

The use of sEHIs could be therapeutically valuable on their own or as a supplement to an omega-3 diet (e.g. EO3 drink). EC5026, a compound similar to TPPU, is in human safety trials on escalating oral doses from 1 mg per day [

43]. In addition, the effects of the STING inhibitor H-151 were comparable to sEHI effects and could be additive or synergistic. The recommendations of the best therapy will be guided further by field experience, yet these three agents (TPPU or EC5026, H-151, and the prostaglandin EP4 inhibitor ONO), offer promise of reducing the adverse effects of monoclonal antibody therapies and directly improving AD therapy.

Author Contributions

Milan Fiala designed the study, performed the bulk of experiments, and wrote the manuscript; Sung Hee Hwang prepared epoxy fatty acids and sEH inhibitors in the laboratory of B. Hammock; Bruce Hammock provided intellectual content; Julian Whitelegge provided intellectual content; K. Paul provided intellectual content; Karolina Kaczor-Urbanowicz and Andrzej Urbanowicz performed RNA sequencing of macrophages treated by EpFAs by processing the final libraries and aligning the data to the human genome GCHr38 and analysis of treated and untreated samples. S. Kesari followed the patients and provided intellectual content. Haley Marks and Brian Jeong provided microscopic imaging of macrophage cultures in Figure 7.

Data availability

The data on the EpFA effects on the transcriptome in two patients are available from the authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jeffrey Gornbein, PhD for the statistical analysis of the immunofluorescence results in Figure 7. We thank Haley Marks and Brian Jeong for microscopic images of macrophage cultures in Figure 7. Partial support for this work was provided by NIH – NIEHS (RIVER Award) R35 ES030443-01, NIH-NINDS U54 NS127758 (Counter Act Program), and NIH – NIEHS (Superfund Award) P42 ES004699.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jeffrey Gornbein, PhD for the statistical analysis of the immunofluorescence results in Figure 7.

Conflict of interests

Bruce D. Hammock and Sung Hee Hwang are developing the EC5026 inhibitor of soluble epoxide hydrolase for therapy of Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases.

Support

Partial support for this work was provided by NIH – NIEHS (RIVER Award) R35 ES030443-01, NIH-NINDS U54 NS127758 (Counter Act Program), and NIH – NIEHS (Superfund Award) P42 ES004699.

References

- Sevigny, J., Chiao, P., Bussiere, T., Weinreb, P. H., Williams, L., Maier, M., Dunstan, R., Salloway, S., Chen, T., Ling, Y., O'Gorman, J., Qian, F., Arastu, M., Li, M., Chollate, S., Brennan, M. S., Quintero-Monzon, O., Scannevin, R. H., Arnold, H. M., Engber, T., Rhodes, K., Ferrero, J., Hang, Y., Mikulskis, A., Grimm, J., Hock, C., Nitsch, R. M., and Sandrock, A. (2016) The antibody aducanumab reduces Abeta plaques in Alzheimer's disease. Nature 537, 50-56.

- Wojtunik-Kulesza, K., Rudkowska, M., and Orzel-Sajdlowska, A. (2023) Aducanumab-Hope or Disappointment for Alzheimer's Disease. International journal of molecular sciences 24.

- Salloway, S., Chalkias, S., Barkhof, F., Burkett, P., Barakos, J., Purcell, D., Suhy, J., Forrestal, F., Tian, Y., Umans, K., Wang, G., Singhal, P., Budd Haeberlein, S., and Smirnakis, K. (2022) Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities in 2 Phase 3 Studies Evaluating Aducanumab in Patients With Early Alzheimer Disease. JAMA neurology 79, 13-21.

- Couzin-Frankel, J. (2023) Alzheimer's drug approval gets a mixed reception. Science 379, 126-127.

- van Dyck, C. H., Swanson, C. J., Aisen, P., Bateman, R. J., Chen, C., Gee, M., Kanekiyo, M., Li, D., Reyderman, L., Cohen, S., Froelich, L., Katayama, S., Sabbagh, M., Vellas, B., Watson, D., Dhadda, S., Irizarry, M., Kramer, L. D., and Iwatsubo, T. (2023) Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer's Disease. N Engl J Med 388, 9-21.

- Reish, N. J., Jamshidi, P., Stamm, B., Flanagan, M. E., Sugg, E., Tang, M., Donohue, K. L., McCord, M., Krumpelman, C., Mesulam, M. M., Castellani, R., and Chou, S. H. (2023) Multiple Cerebral Hemorrhages in a Patient Receiving Lecanemab and Treated with t-PA for Stroke. N Engl J Med 388, 478-479.

- Decout, A., Katz, J. D., Venkatraman, S., and Ablasser, A. (2021) The cGAS-STING pathway as a therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 21, 548-569.

- Chauvin, S. D., Stinson, W. A., Platt, D. J., Poddar, S., and Miner, J. J. (2023) Regulation of cGAS and STING signaling during inflammation and infection. J Biol Chem 299, 104866.

- Gulen, M. F., Samson, N., Keller, A., Schwabenland, M., Liu, C., Gluck, S., Thacker, V. V., Favre, L., Mangeat, B., Kroese, L. J., Krimpenfort, P., Prinz, M., and Ablasser, A. (2023) cGAS-STING drives ageing-related inflammation and neurodegeneration. Nature 620, 374-380.

- Ablasser, A., and Chen, Z. J. (2019) cGAS in action: Expanding roles in immunity and inflammation. Science 363.

- Yu, C. H., Davidson, S., Harapas, C. R., Hilton, J. B., Mlodzianoski, M. J., Laohamonthonkul, P., Louis, C., Low, R. R. J., Moecking, J., De Nardo, D., Balka, K. R., Calleja, D. J., Moghaddas, F., Ni, E., McLean, C. A., Samson, A. L., Tyebji, S., Tonkin, C. J., Bye, C. R., Turner, B. J., Pepin, G., Gantier, M. P., Rogers, K. L., McArthur, K., Crouch, P. J., and Masters, S. L. (2020) TDP-43 Triggers Mitochondrial DNA Release via mPTP to Activate cGAS/STING in ALS. Cell 183, 636-649 e618.

- Matsumoto, N., Singh, N., Lee, K. S., Barnych, B., Morisseau, C., and Hammock, B. D. (2022) The epoxy fatty acid pathway enhances cAMP in mammalian cells through multiple mechanisms. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 162, 106662.

- Fiala, M., Kooij, G., Wagner, K., Hammock, B., and Pellegrini, M. (2017) Modulation of innate immunity of patients with Alzheimer's disease by omega-3 fatty acids. FASEB J 31, 3229-3239.

- Minhas, P. S., Latif-Hernandez, A., McReynolds, M. R., Durairaj, A. S., Wang, Q., Rubin, A., Joshi, A. U., He, J. Q., Gauba, E., Liu, L., Wang, C., Linde, M., Sugiura, Y., Moon, P. K., Majeti, R., Suematsu, M., Mochly-Rosen, D., Weissman, I. L., Longo, F. M., Rabinowitz, J. D., and Andreasson, K. I. (2021) Restoring metabolism of myeloid cells reverses cognitive decline in ageing. Nature 590, 122-128.

- Dover, M., Moseley, T., Biskaduros, A., Paulchakrabarti, M., Hwang, S. H., Hammock, B., Choudhury, B., Kaczor-Urbanowicz, K. E., Urbanowicz, A., Morselli, M., Dang, J., Pellegrini, M., Paul, K., Bentolila, L. A., and Fiala, M. (2023) Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Mend Macrophage Transcriptome, Glycome, and Phenotype in the Patients with Neurodegenerative Diseases, Including Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis 91, 245-261.

- Hwang, S. H., Wagner, K., Xu, J., Yang, J., Li, X., Cao, Z., Morisseau, C., Lee, K. S., and Hammock, B. D. (2017) Chemical synthesis and biological evaluation of omega-hydroxy polyunsaturated fatty acids. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 27, 620-625.

- Falck, J. R., Yadagiri, P., and Capdevila, J. (1990) Synthesis of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids and heteroatom analogs. Methods Enzymol 187, 357-364.

- Rose, T. E., Morisseau, C., Liu, J. Y., Inceoglu, B., Jones, P. D., Sanborn, J. R., and Hammock, B. D. (2010) 1-Aryl-3-(1-acylpiperidin-4-yl)urea inhibitors of human and murine soluble epoxide hydrolase: structure-activity relationships, pharmacokinetics, and reduction of inflammatory pain. J Med Chem 53, 7067-7075.

- Hardy, J., and Selkoe, D. J. (2002) The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297, 353-356.

- Avagyan, H., Goldenson, B., Tse, E., Masoumi, A., Porter, V., Wiedau-Pazos, M., Sayre, J., Ong, R., Mahanian, M., Koo, P., Bae, S., Micic, M., Liu, P. T., Rosenthal, M. J., and Fiala, M. (2009) Immune blood biomarkers of Alzheimer disease patients. J Neuroimmunol 210, 67-72.

- De Strooper, B., and Karran, E. (2016) The Cellular Phase of Alzheimer's Disease. Cell 164, 603-615.

- Fiala, M. (2015) Curcumin and omega-3 fatty acids enhance NK cell-induced apoptosis of pancreatic cancer cells but curcumin inhibits interferon-gamma production: benefits of omega-3 with curcumin against cancer. Molecules 20, 3020-3026.

- Heneka, M. T., Carson, M. J., El Khoury, J., Landreth, G. E., Brosseron, F., Feinstein, D. L., Jacobs, A. H., Wyss-Coray, T., Vitorica, J., Ransohoff, R. M., Herrup, K., Frautschy, S. A., Finsen, B., Brown, G. C., Verkhratsky, A., Yamanaka, K., Koistinaho, J., Latz, E., Halle, A., Petzold, G. C., Town, T., Morgan, D., Shinohara, M. L., Perry, V. H., Holmes, C., Bazan, N. G., Brooks, D. J., Hunot, S., Joseph, B., Deigendesch, N., Garaschuk, O., Boddeke, E., Dinarello, C. A., Breitner, J. C., Cole, G. M., Golenbock, D. T., and Kummer, M. P. (2015) Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol 14, 388-405.

- Kelly, L., Brown, C., Michalik, D., Hawkes, C. A., Aldea, R., Agarwal, N., Salib, R., Alzetani, A., Ethell, D. W., Counts, S. E., de Leon, M., Fossati, S., Koronyo-Hamaoui, M., Piazza, F., Rich, S. A., Wolters, F. J., Snyder, H., Ismail, O., Elahi, F., Proulx, S. T., Verma, A., Wunderlich, H., Haack, M., Dodart, J. C., Mazer, N., and Carare, R. O. (2023) Clearance of interstitial fluid (ISF) and CSF (CLIC) group-part of Vascular Professional Interest Area (PIA), updates in 2022-2023. Cerebrovascular disease and the failure of elimination of Amyloid-beta from the brain and retina with age and Alzheimer's disease: Opportunities for therapy. Alzheimers Dement.

- Adhikari, U. K., Khan, R., Mikhael, M., Balez, R., David, M. A., Mahns, D., Hardy, J., and Tayebi, M. (2023) Therapeutic anti-amyloid beta antibodies cause neuronal disturbances. Alzheimers Dement 19, 2479-2496.

- Taylor, X., Clark, I. M., Fitzgerald, G. J., Oluoch, H., Hole, J. T., DeMattos, R. B., Wang, Y., and Pan, F. (2023) Amyloid-beta (Abeta) immunotherapy induced microhemorrhages are associated with activated perivascular macrophages and peripheral monocyte recruitment in Alzheimer's disease mice. Mol Neurodegener 18, 59.

- Famenini, S., Rigali, E. A., Olivera-Perez, H. M., Dang, J., Chang, M. T., Halder, R., Rao, R. V., Pellegrini, M., Porter, V., Bredesen, D., and Fiala, M. (2017) Increased intermediate M1-M2 macrophage polarization and improved cognition in mild cognitive impairment patients on omega-3 supplementation. FASEB J 31, 148-160.

- Freund-Levi, Y., Eriksdotter-Jonhagen, M., Cederholm, T., Basun, H., Faxen-Irving, G., Garlind, A., Vedin, I., Vessby, B., Wahlund, L. O., and Palmblad, J. (2006) Omega-3 fatty acid treatment in 174 patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease: OmegAD study: a randomized double-blind trial. Arch Neurol 63, 1402-1408.

- Fiala, M., Carro, E., Ringman, J., and Atwood, C. S. (2005) Insulin-like growth factor-I and luteinizing hormone modulate amyloid-beta phagocytosis by Alzheimer's disease macrophages. In Experimental Biology 2005, San Diego.

- Spector, A. A., and Norris, A. W. (2007) Action of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids on cellular function. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292, C996-1012.

- Olivera-Perez, H. M., Lam, L., Dang, J., Jiang, W., Rodriguez, F., Rigali, E., Weitzman, S., Porter, V., Rubbi, L., Morselli, M., Pellegrini, M., and Fiala, M. (2017) Omega-3 fatty acids increase the unfolded protein response and improve amyloid-beta phagocytosis by macrophages of patients with mild cognitive impairment. FASEB J 31, 4359-4369.

- Morisseau, C., Kodani, S. D., Kamita, S. G., Yang, J., Lee, K. S. S., and Hammock, B. D. (2021) Relative Importance of Soluble and Microsomal Epoxide Hydrolases for the Hydrolysis of Epoxy-Fatty Acids in Human Tissues. International journal of molecular sciences 22.

- Wagner, K. M., Gomes, A., McReynolds, C. B., and Hammock, B. D. (2020) Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase Regulation of Lipid Mediators Limits Pain. Neurotherapeutics 17, 900-916.

- Plowey, E. D., Bussiere, T., Rajagovindan, R., Sebalusky, J., Hamann, S., von Hehn, C., Castrillo-Viguera, C., Sandrock, A., Budd Haeberlein, S., van Dyck, C. H., and Huttner, A. (2022) Alzheimer disease neuropathology in a patient previously treated with aducanumab. Acta Neuropathol 144, 143-153.

- Fiala, M. Re-balancing of inflammation and abeta immunity as a therapeutic for Alzheimer's disease-view from the bedside. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 9, 192-196.

- Fiala, M., Restrepo, L., and Pellegrini, M. (2018) Immunotherapy of Mild Cognitive Impairment by omega-3 Supplementation: Why Are Amyloid-beta Antibodies and omega-3 Not Working in Clinical Trials? J Alzheimers Dis 62, 1013-1022.

- Lopez-Vicario, C., Alcaraz-Quiles, J., Garcia-Alonso, V., Rius, B., Hwang, S. H., Titos, E., Lopategi, A., Hammock, B. D., Arroyo, V., and Claria, J. (2015) Inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase modulates inflammation and autophagy in obese adipose tissue and liver: role for omega-3 epoxides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 536-541.

- Ren, Q., Ma, M., Ishima, T., Morisseau, C., Yang, J., Wagner, K. M., Zhang, J. C., Yang, C., Yao, W., Dong, C., Han, M., Hammock, B. D., and Hashimoto, K. (2016) Gene deficiency and pharmacological inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase confers resilience to repeated social defeat stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, E1944-1952.

- Ren, Q., Ma, M., Yang, J., Nonaka, R., Yamaguchi, A., Ishikawa, K. I., Kobayashi, K., Murayama, S., Hwang, S. H., Saiki, S., Akamatsu, W., Hattori, N., Hammock, B. D., and Hashimoto, K. (2018) Soluble epoxide hydrolase plays a key role in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, E5815-E5823.

- Ghosh, A., Comerota, M. M., Wan, D., Chen, F., Propson, N. E., Hwang, S. H., Hammock, B. D., and Zheng, H. (2020) An epoxide hydrolase inhibitor reduces neuroinflammation in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Sci Transl Med 12.

- Shan, J., and Hashimoto, K. (2022) Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase as a Therapeutic Target for Neuropsychiatric Disorders. International journal of molecular sciences 23.

- Deng, J., Yang, H., Haak, V. M., Yang, J., Kipper, F. C., Barksdale, C., Hwang, S. H., Gartung, A., Bielenberg, D. R., Subbian, S., Ho, K. K., Ye, X., Fan, D., Sun, Y., Hammock, B. D., and Panigrahy, D. (2021) Eicosanoid regulation of debris-stimulated metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118.

- Hammock, B. D., McReynolds, C. B., Wagner, K., Buckpitt, A., Cortes-Puch, I., Croston, G., Lee, K. S. S., Yang, J., Schmidt, W. K., and Hwang, S. H. (2021) Movement to the Clinic of Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase Inhibitor EC5026 as an Analgesic for Neuropathic Pain and for Use as a Nonaddictive Opioid Alternative. J Med Chem 64, 1856-1872.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).