Submitted:

09 April 2025

Posted:

10 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preliminaries of the Algebra of Quaternions

- i)

- p∗(q∗s) = (p∗q)∗s; ∀ p, q, s∈4 (2)

- ii)

- The element 1 = (1,0,0,0) ∈ 4 is such that: 1∗p=p∗1=p, ∀p∈4. This element is known as the neutral element of the multiplication in 4.

- iii)

- iii) ∀p∈4, p ≠ (0,0,0,0); p’∈4 such that p∗p’ = 1. The element p’ is called the multiplicative inverse of the quaternion p.

- iv)

- iv) The operation ∗:4×4®4 is not commutative. This is:

- v)

- p∗q ≠ q∗p

- vi)

- The following distributive properties are satisfied:

- 1)

- (11)

- 2)

- 3)

2.2. Parametric Representation of Rotations of a Rigid Body

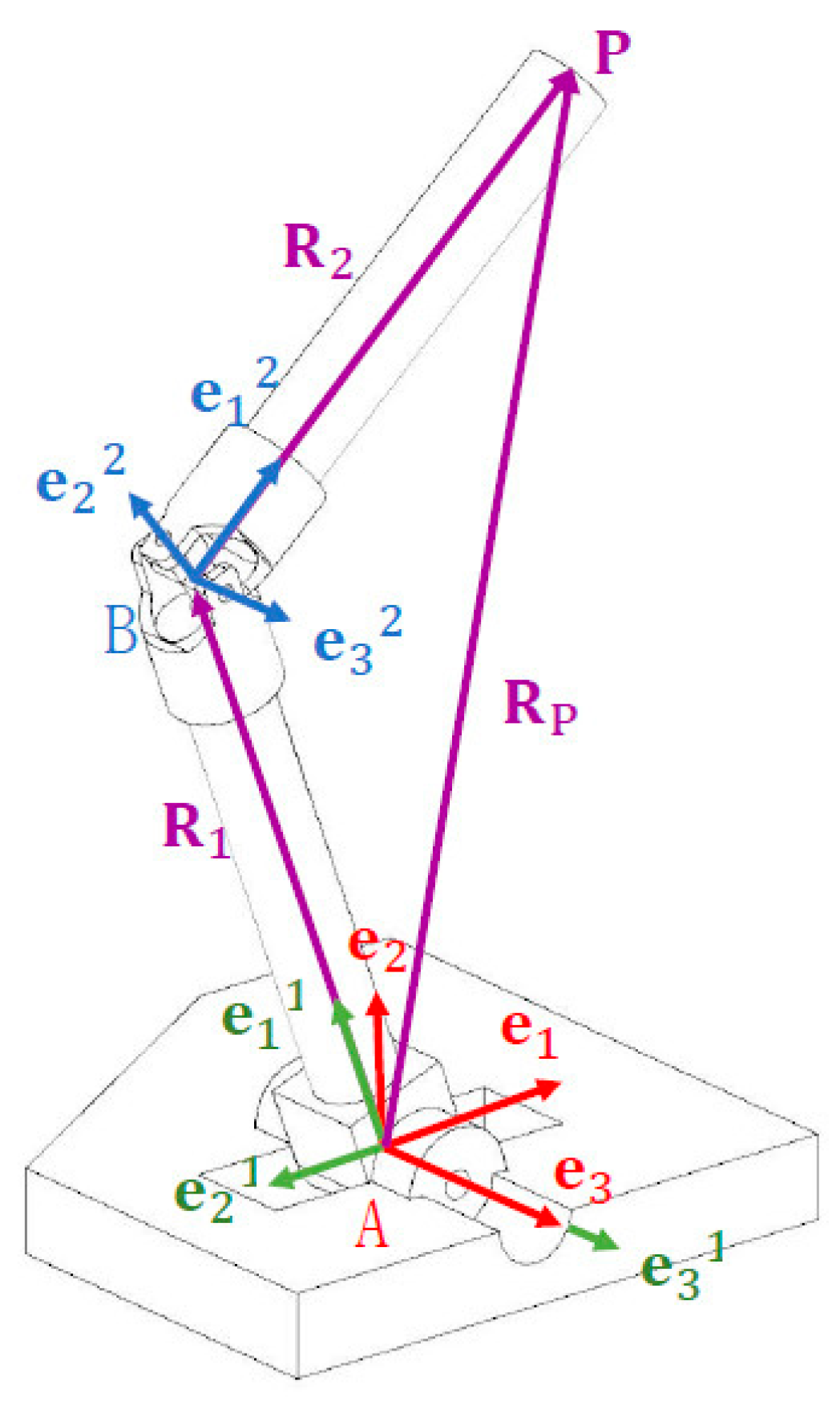

2.3. Kinematic Modeling of Coupled Bodies

2.3.1. Isomorphism of the Vectors of 3 to the Vector Space Q

2.3.2. Rotation of a Cartesian Frame of Reference

2.3.3. Configuration of Coupled Bodies

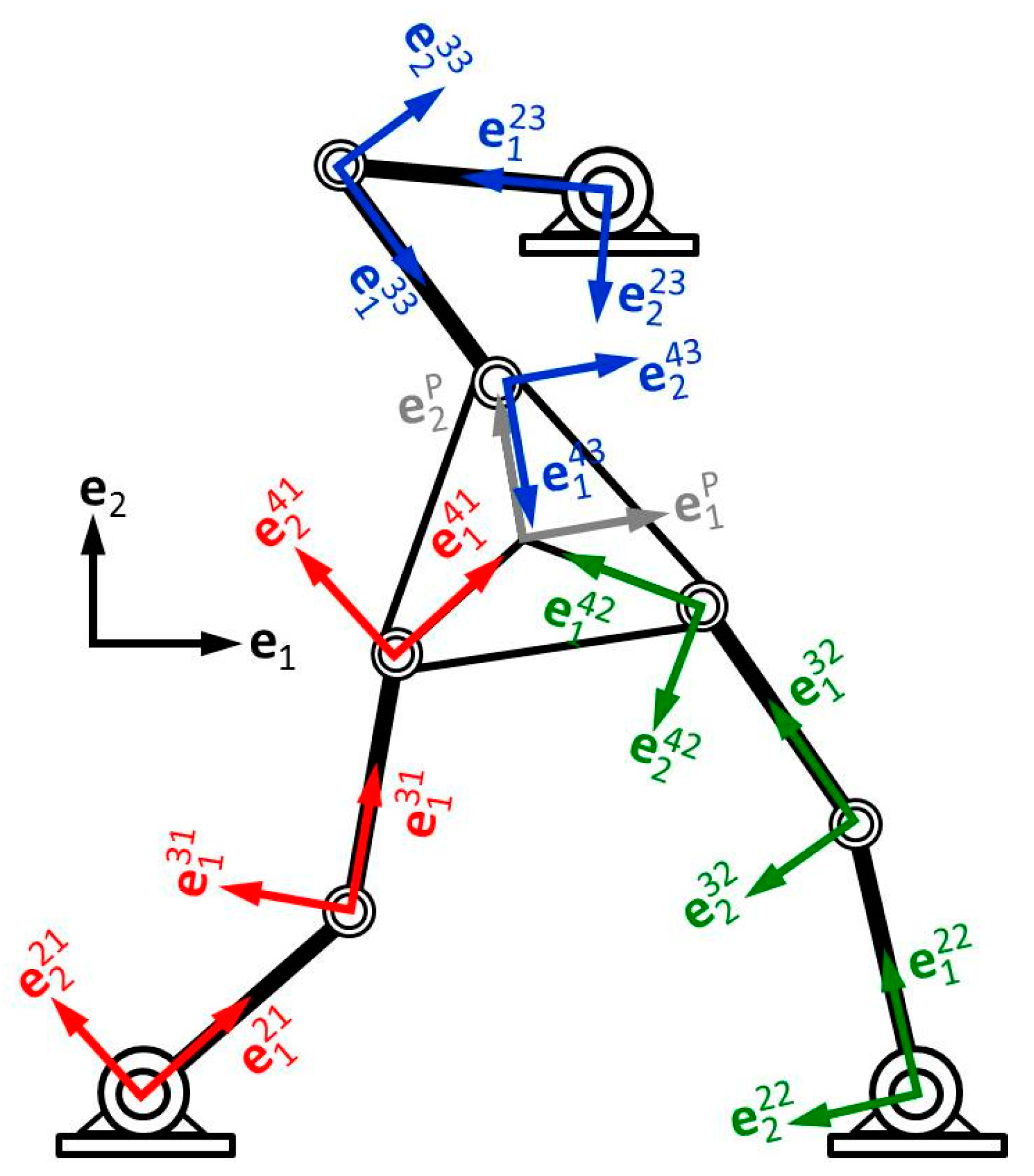

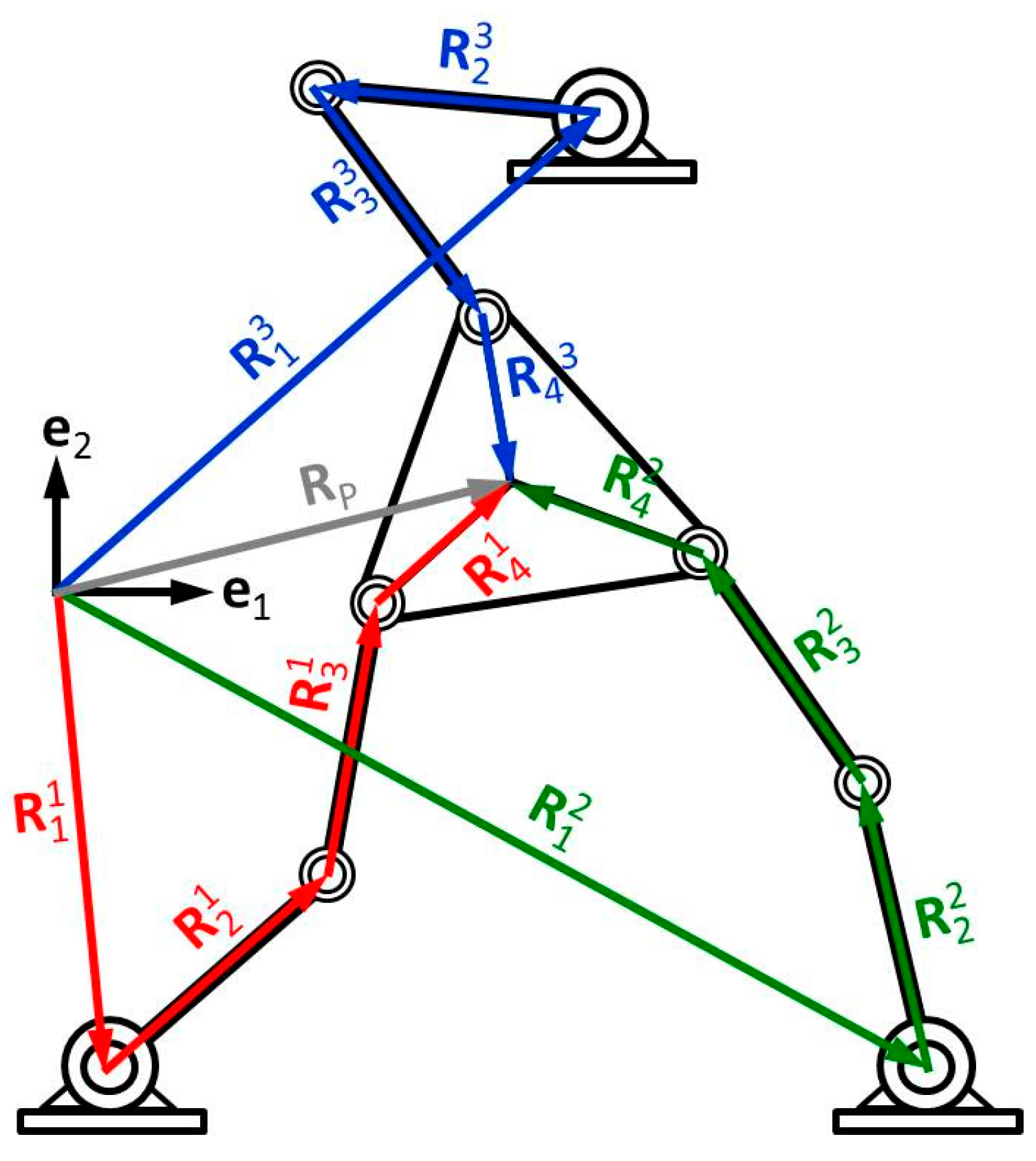

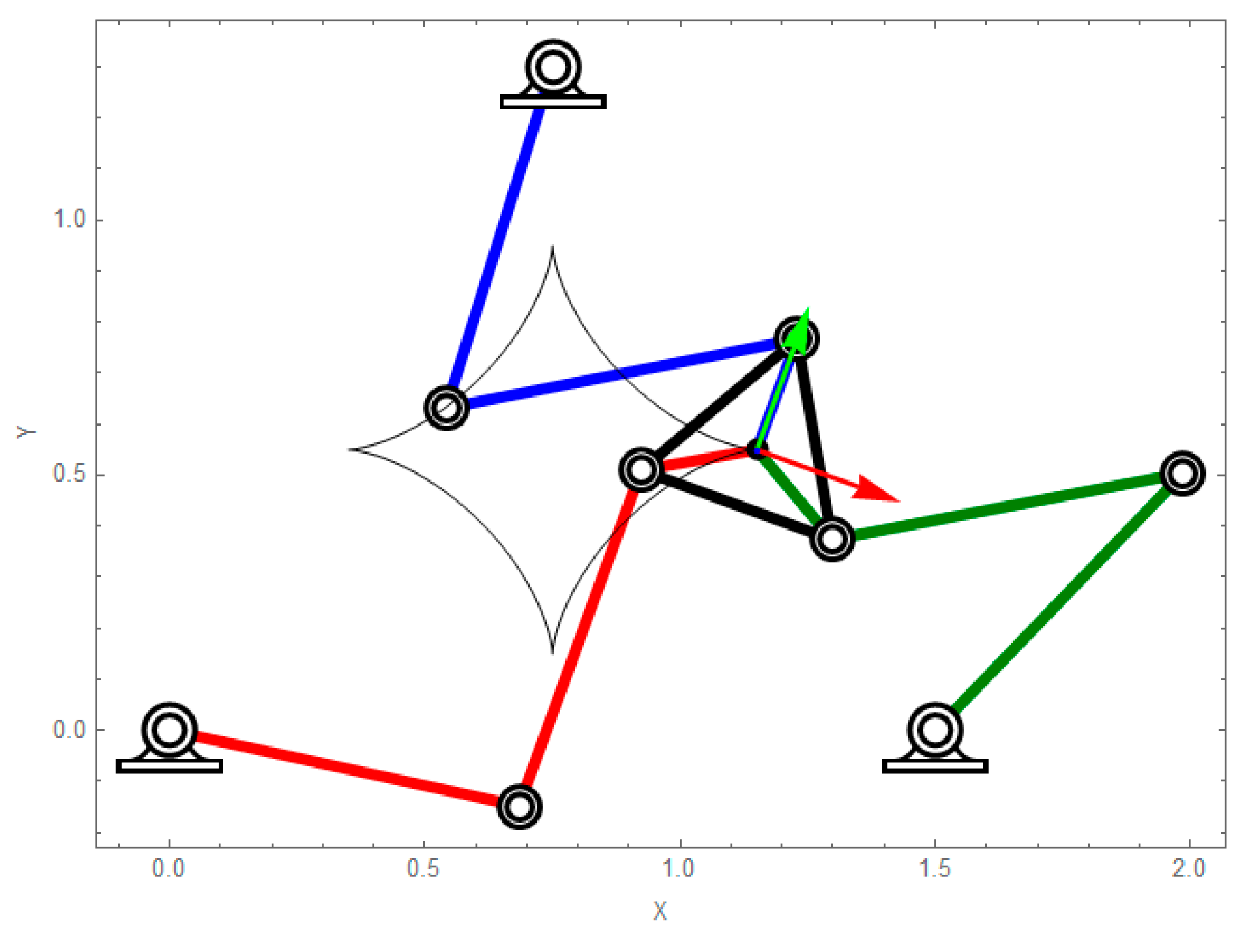

2.4. Modeling of a RRR Planar Parallel Robot

2.4.1. Loop Equations

2.4.2. Platform Orientation Equation

2.4.3. Formulation of the Inverse Kinematic Problem of the RRR Planar Parallel Robot

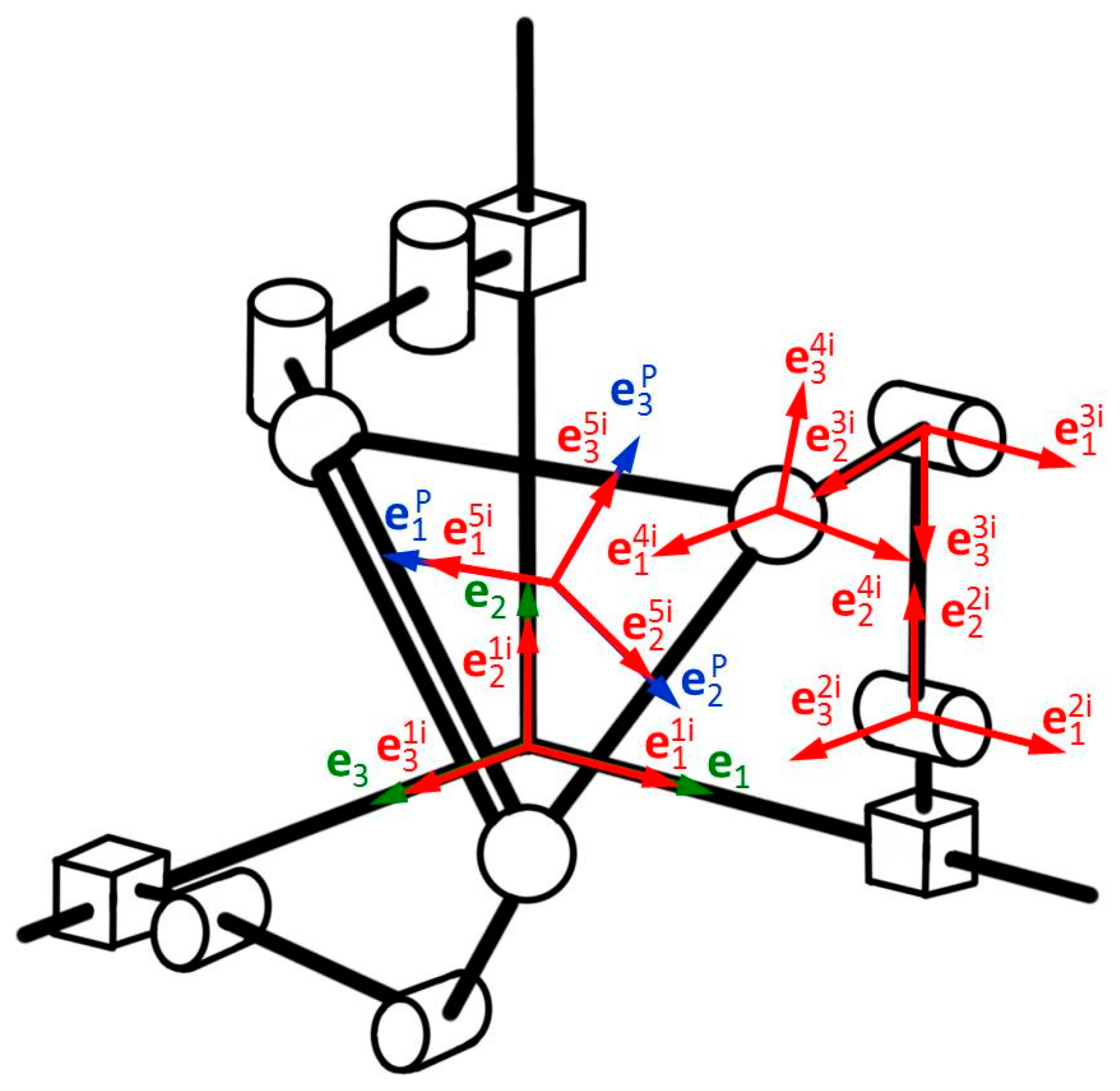

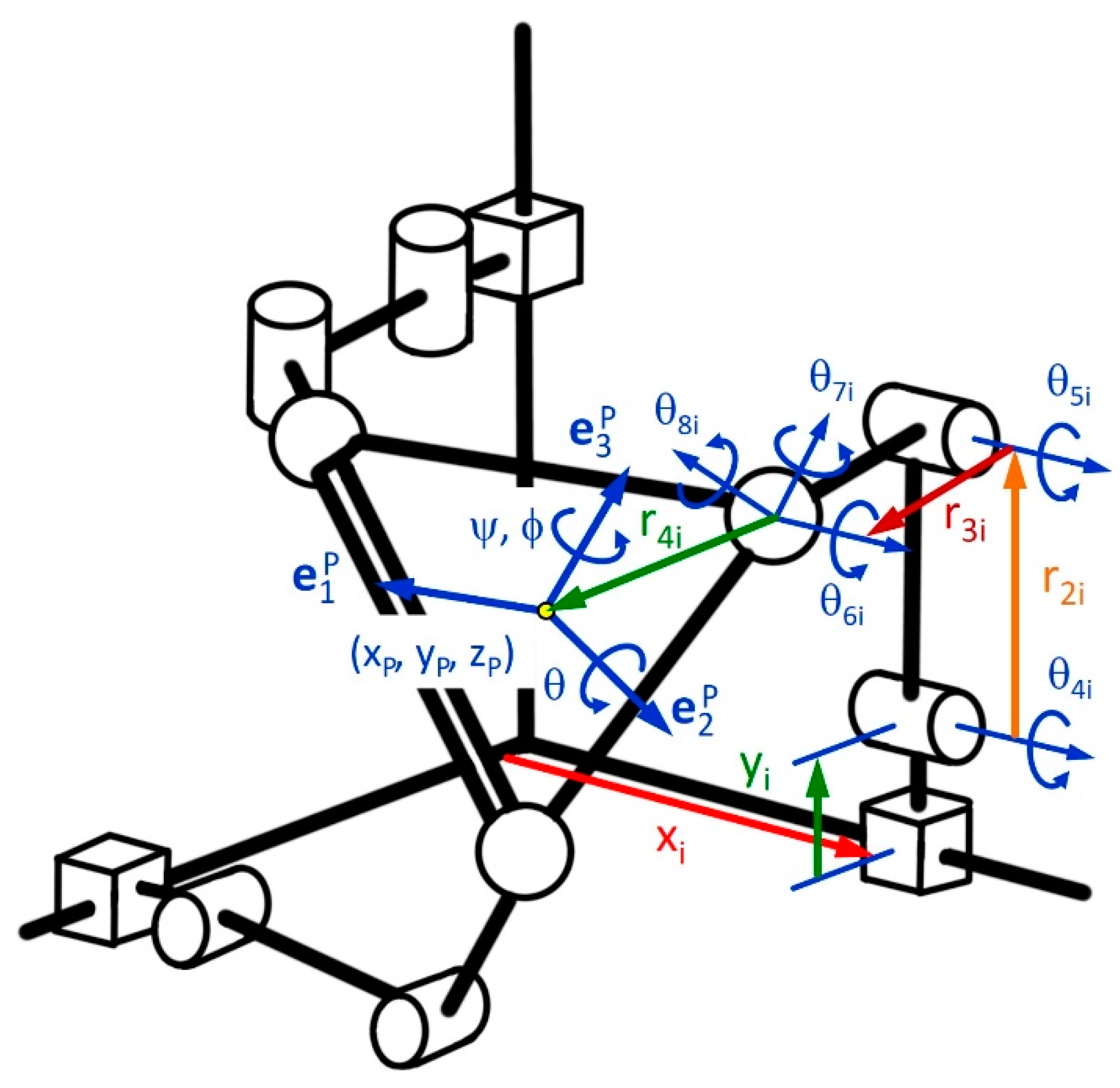

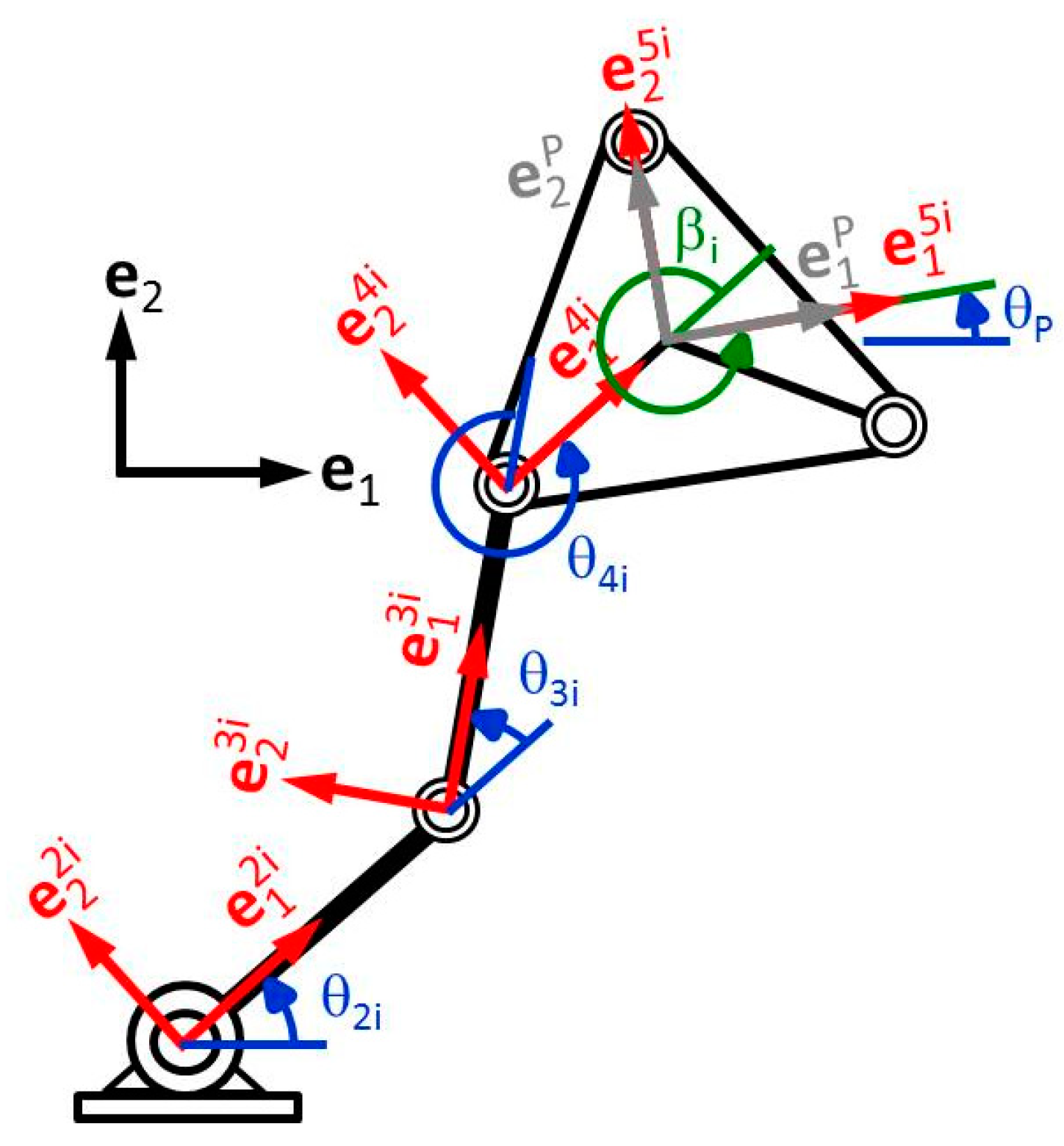

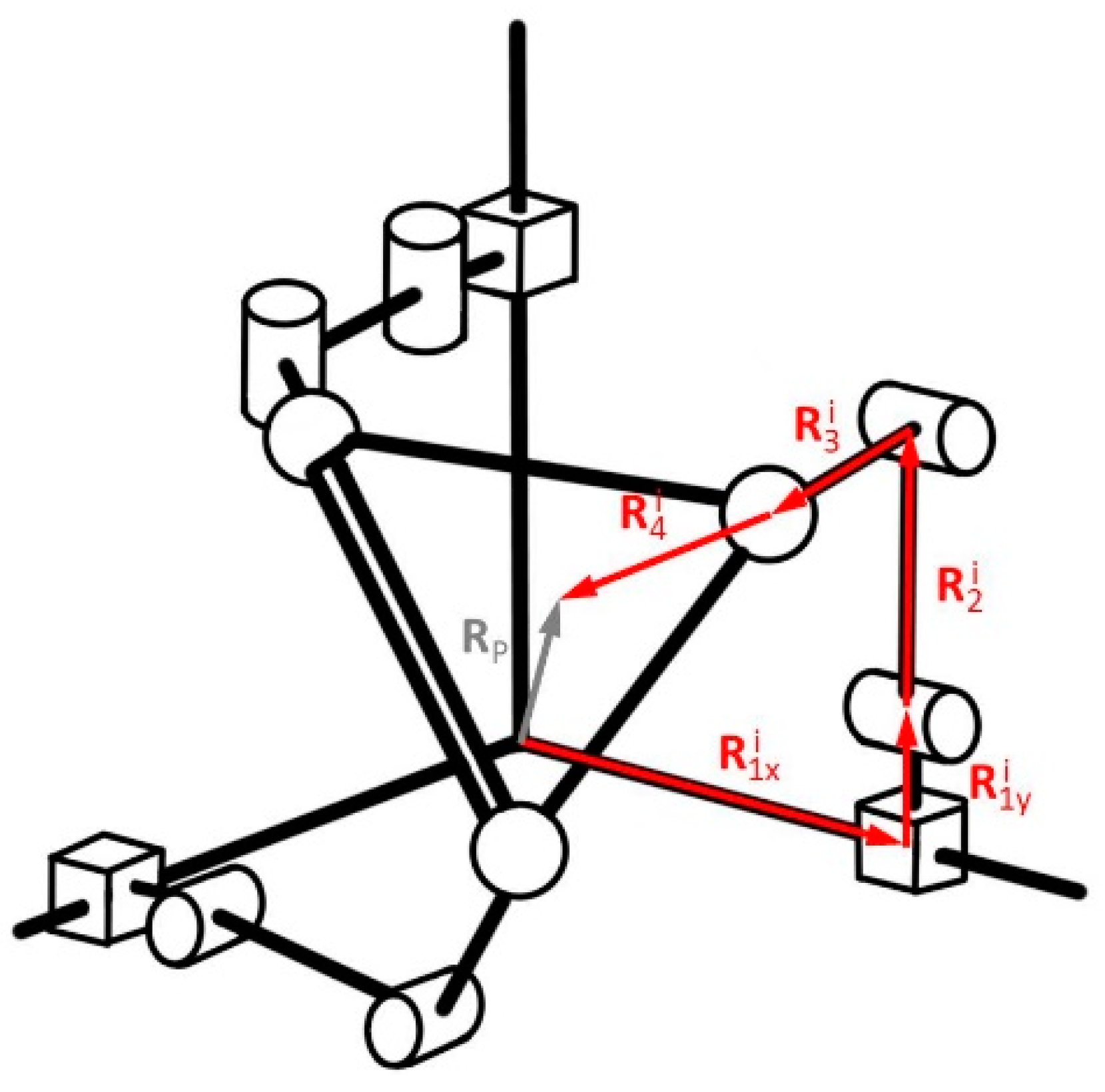

2.5. Modeling of a PRRS Spatial Parallel Robot

2.5.1. Loop Equations

2.5.2. Equation of Platform Orientation

2.5.3. Formulation of the PRRS-Type Inverse Problem

2.6. Numerical Experimentation

3. Results

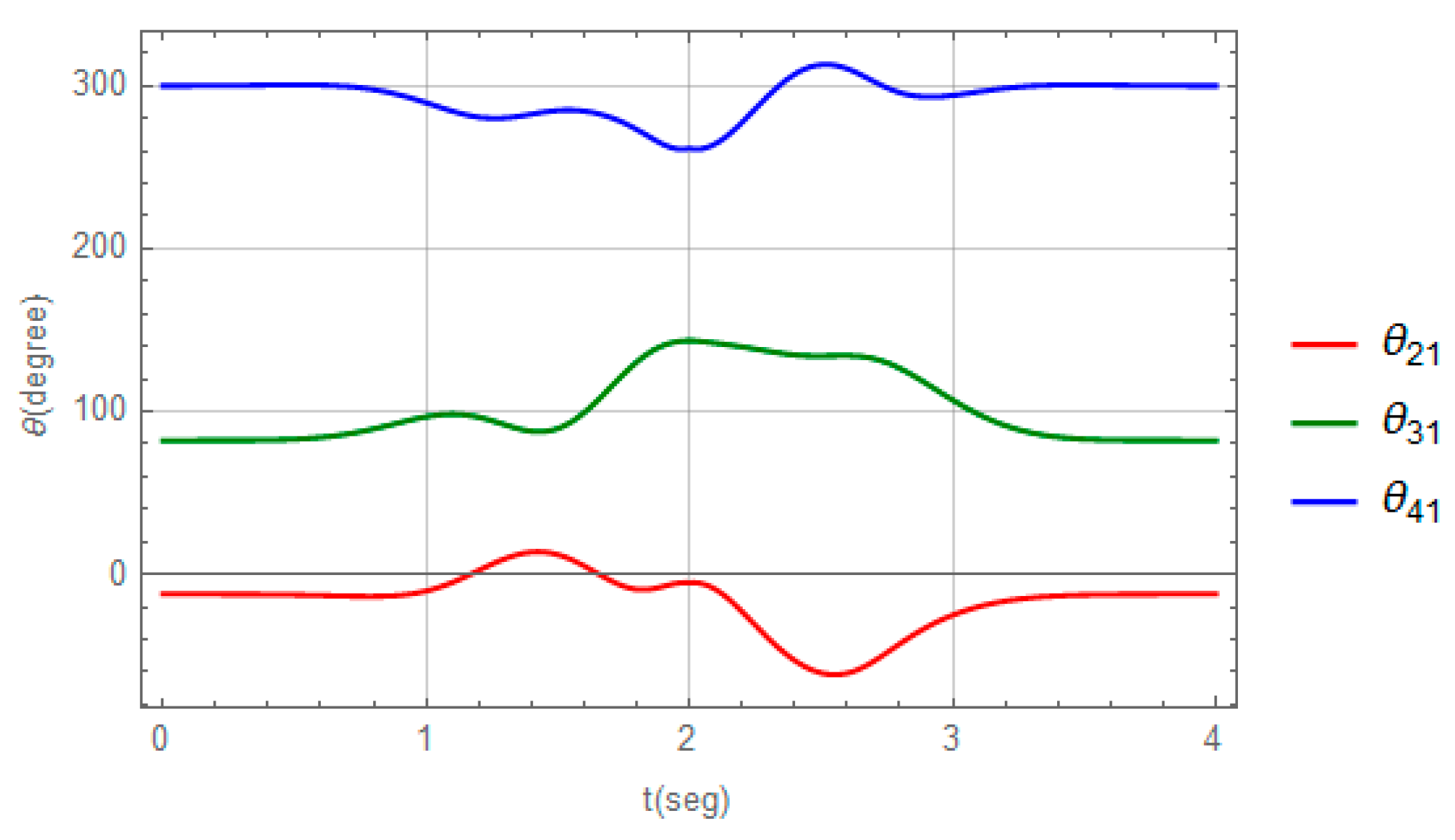

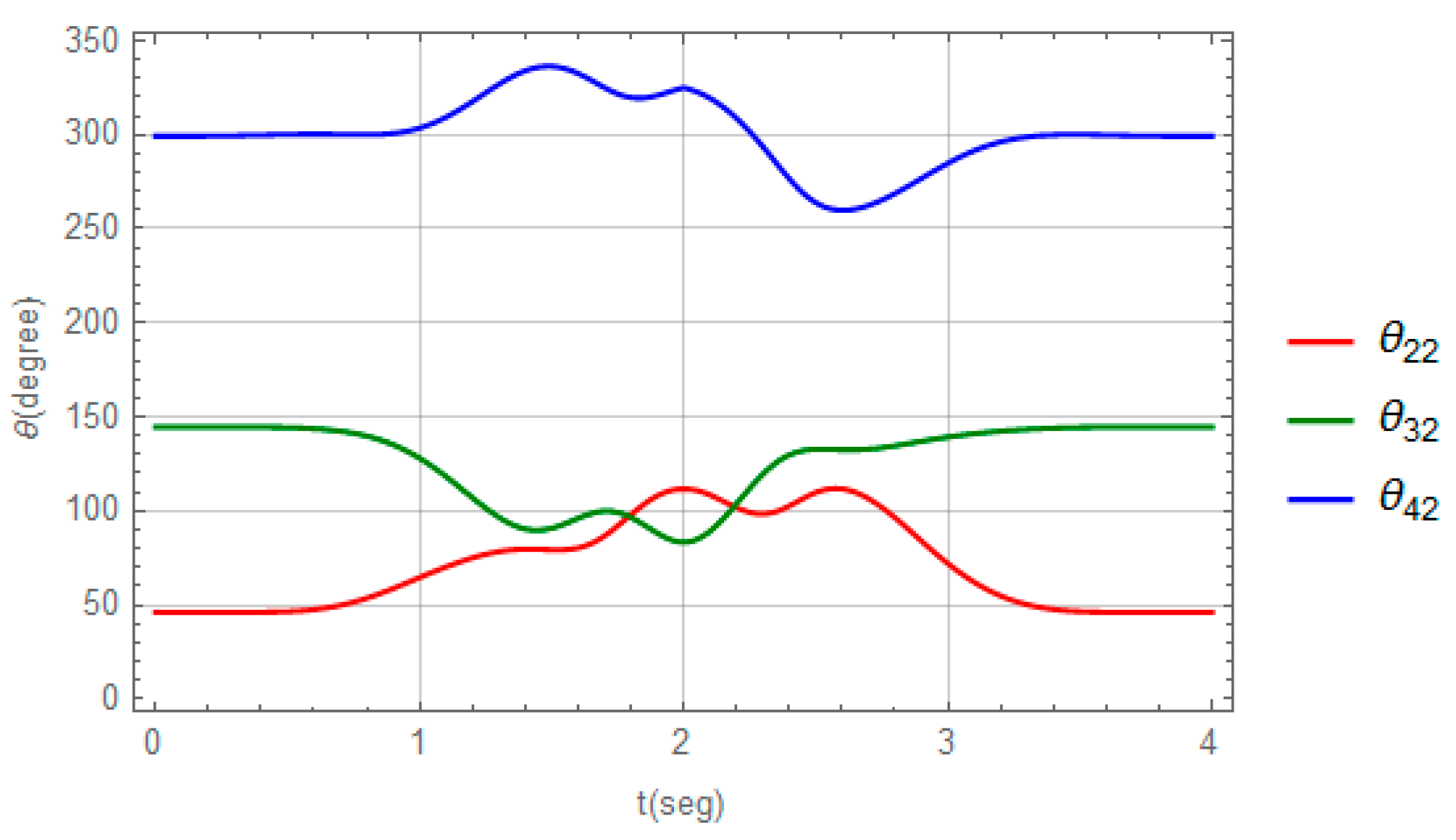

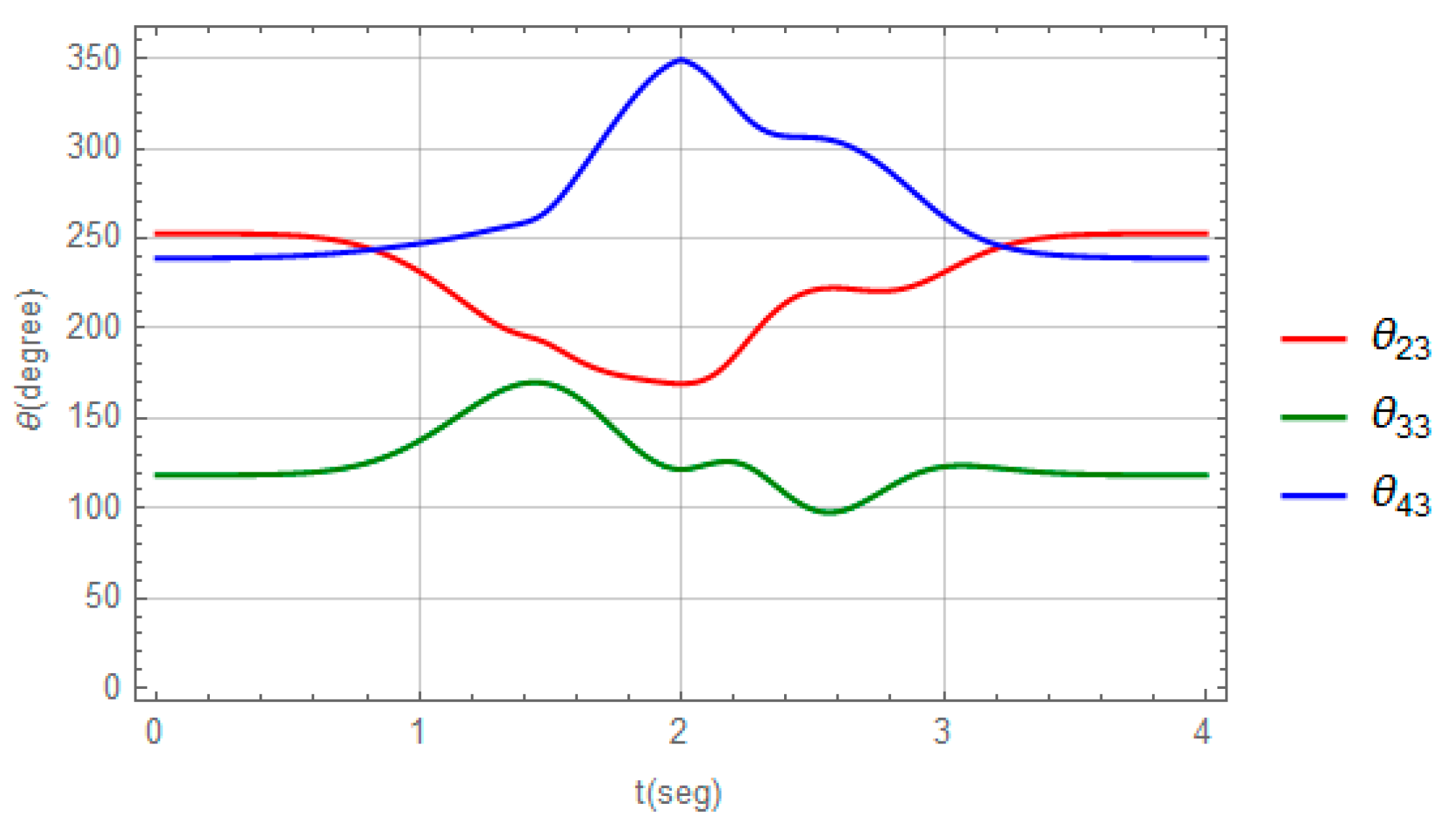

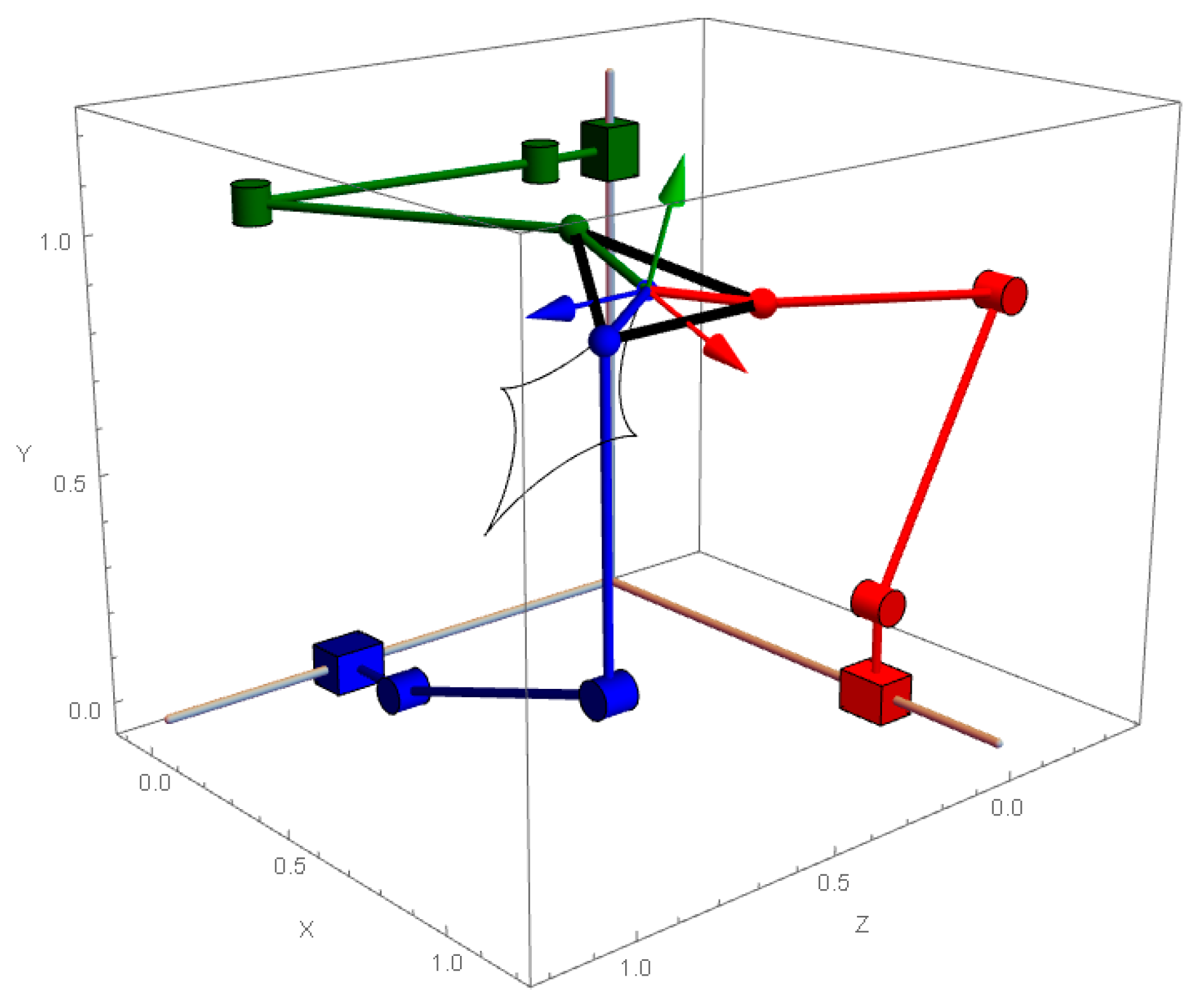

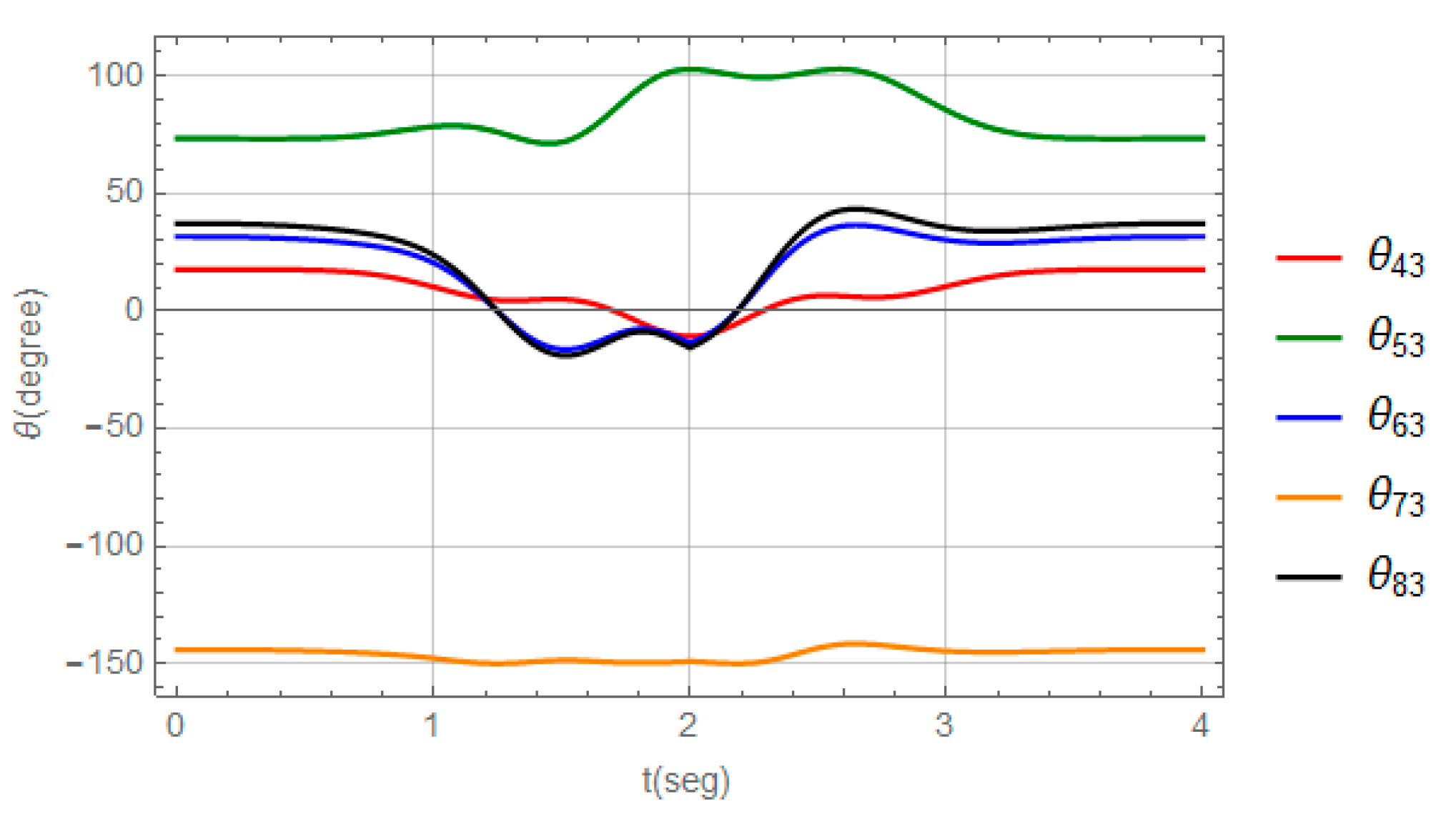

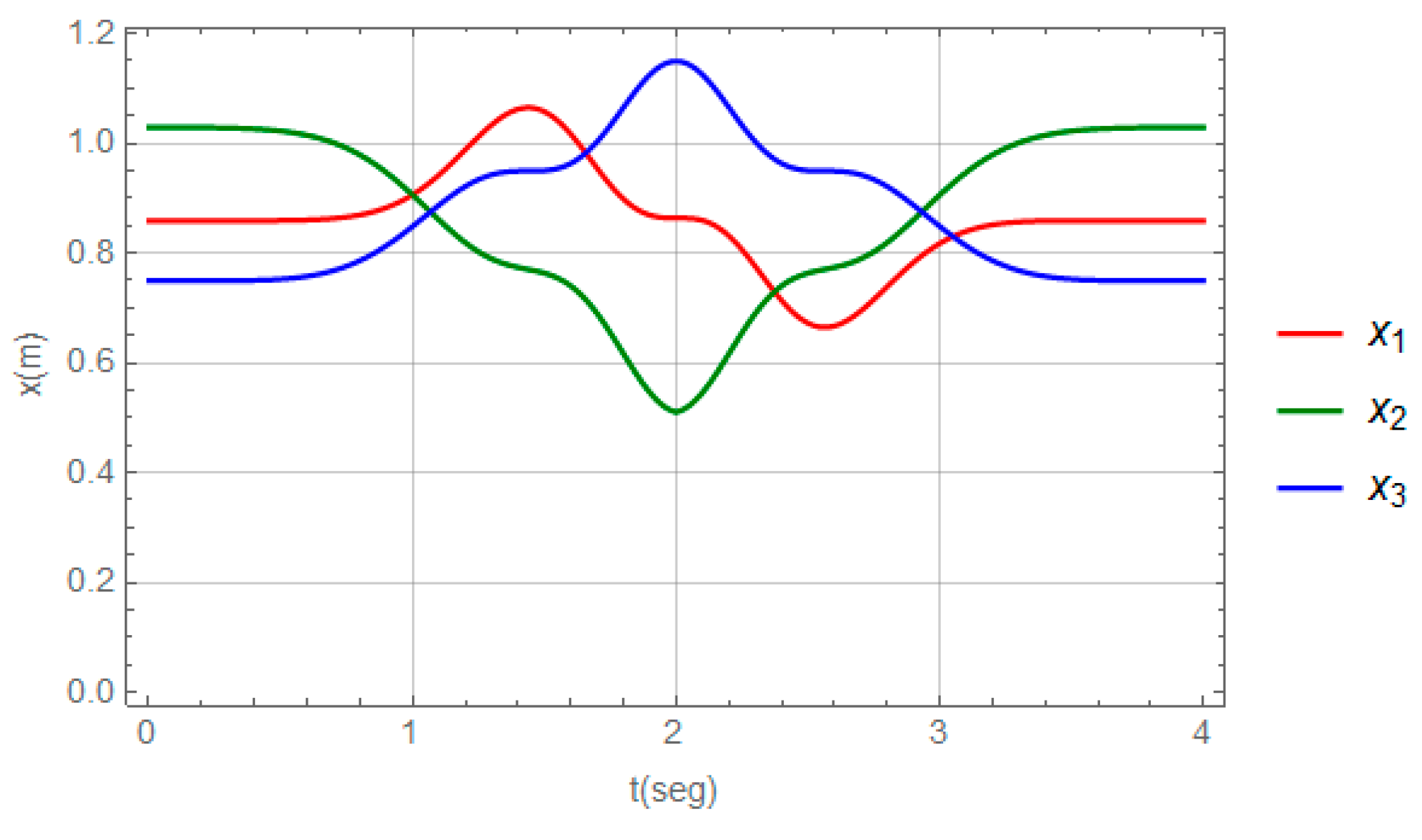

3.1. Numerical Model and Solution for the RRR Parallel Robot

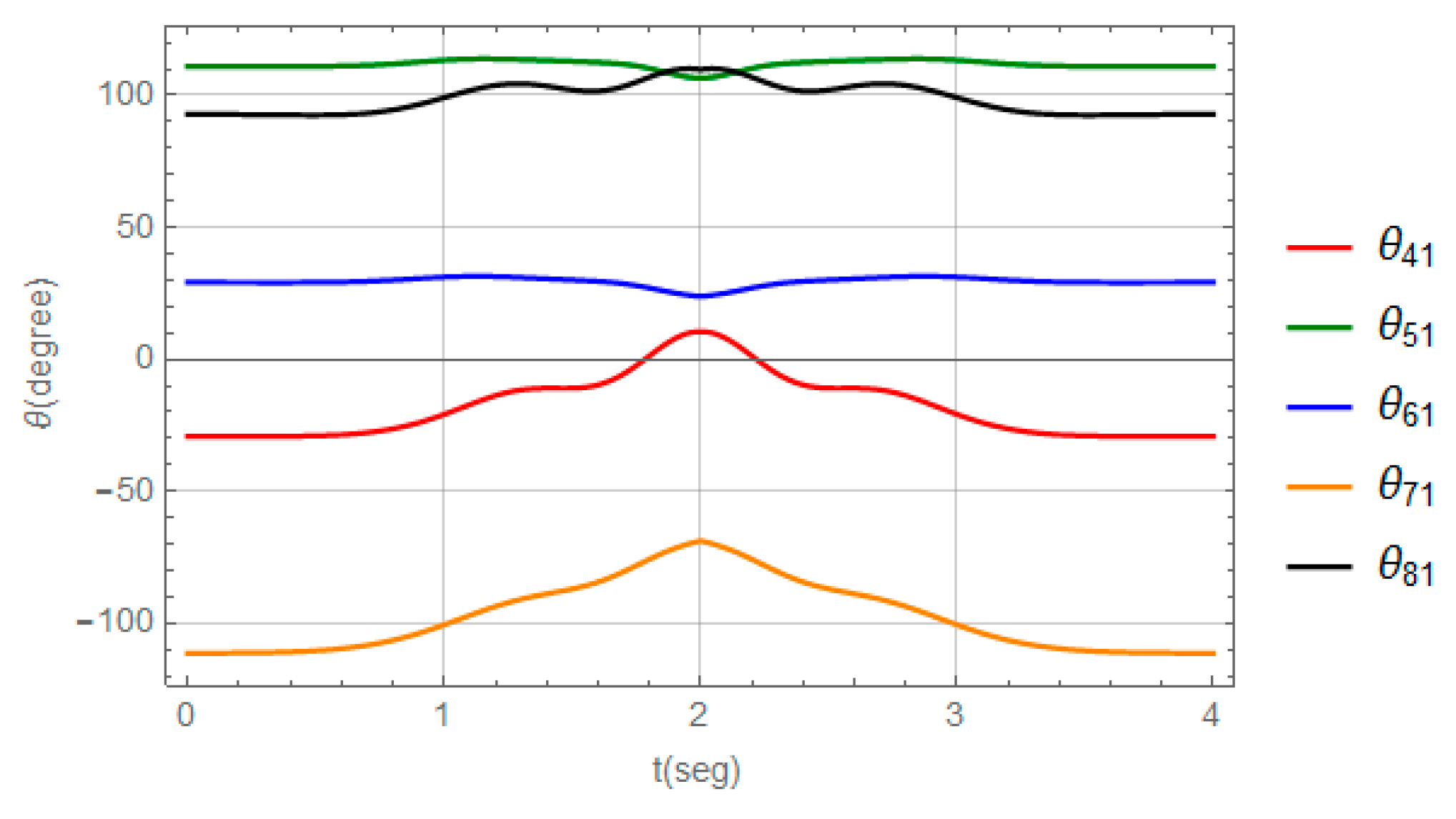

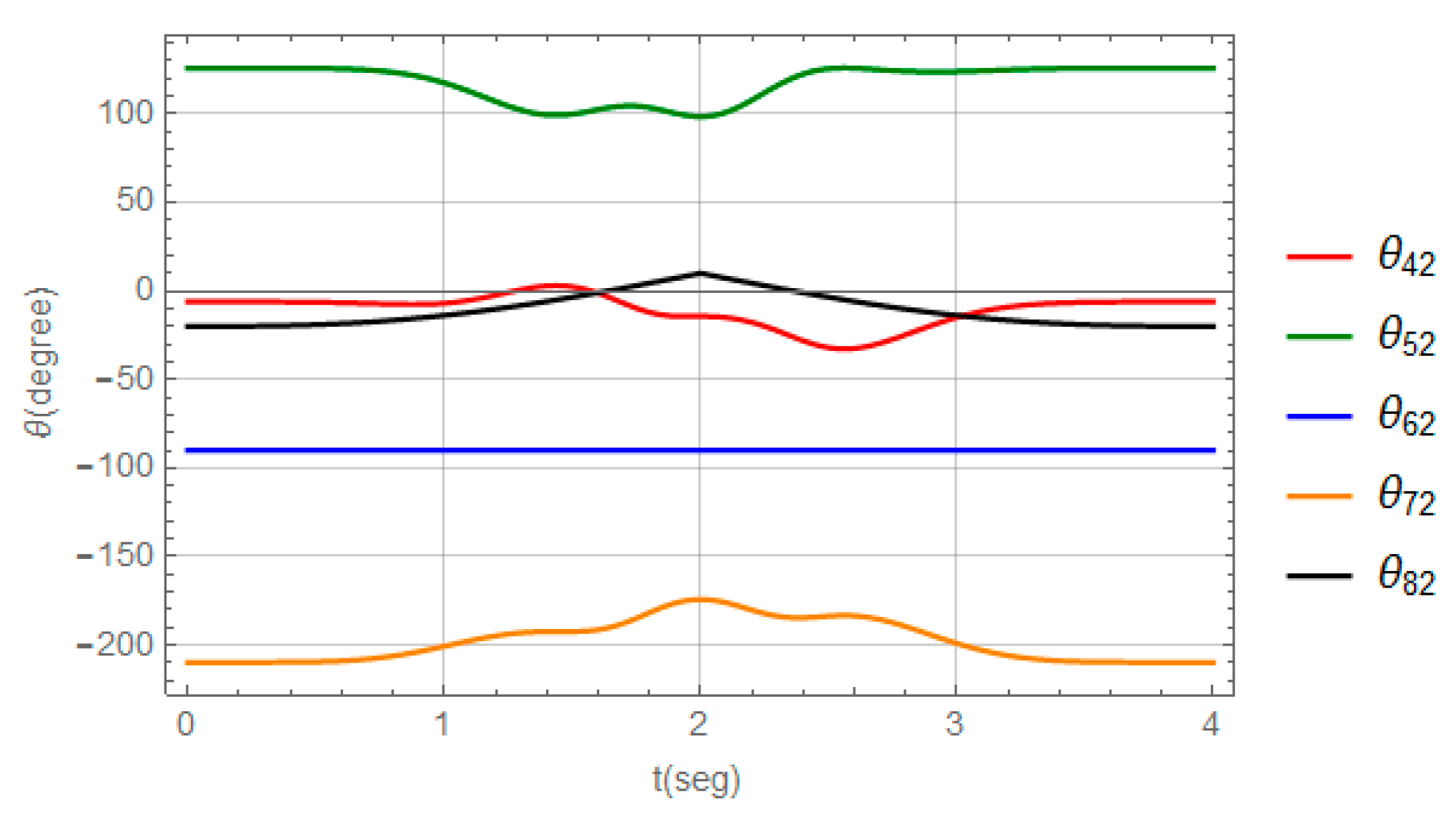

3.2. Numerical Model and Solution for the PRRS Parallel Robot

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The methodology proposed in this work and the application of unitary quaternions in the modeling process made it possible to build in a systematic and functional way the mathematical models that define the inverse kinematic problem of a flat RRR-type robot and a PRRS-type space robot.

- The mathematical models generated by the application of the methodology to each robot had the following characteristics: 1) the inverse kinematic problem associated with the RRR robot moving in the plane generated a system of 21 nonlinear equations with 18 unknowns of the polynomial type, and 2) the inverse kinematic problem associated with the PRRS robot moving in space generated a system of 36 nonlinear equations with 33 unknowns of the polynomial type for each kinematic chain.

- To solve the mathematical models generated from the inverse kinematic problem approach in both robots, two linear and angular trajectories were used, and the Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno numerical method was used to calculate the parameters of the quaternions that define the rotations and displacements of each joint. The BFGS optimization method was used due to the high number of equations and unknowns related to the mathematical models of both robots and the advantage offered by formal calculation packages such as Mathematica V12 that has such method programmed.

- The systematization of unitary quaternions developed by Reyes [25] and applied by Jiménez et al. [24] in the modeling of a PUMA robot, has allowed the construction of kinematic models of parallel robots using the binary operations of addition and multiplication between quaternions. Thus, it was possible to model open and closed kinematic chains in a systematic way, which increases the scope of the theory developed by [25].

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PUMA | Programmable Universal Manipulation Arm |

| DOF | Degree of Freedom |

| BFGS | Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno |

| RRR | Rotational, Rotational, Rotational |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

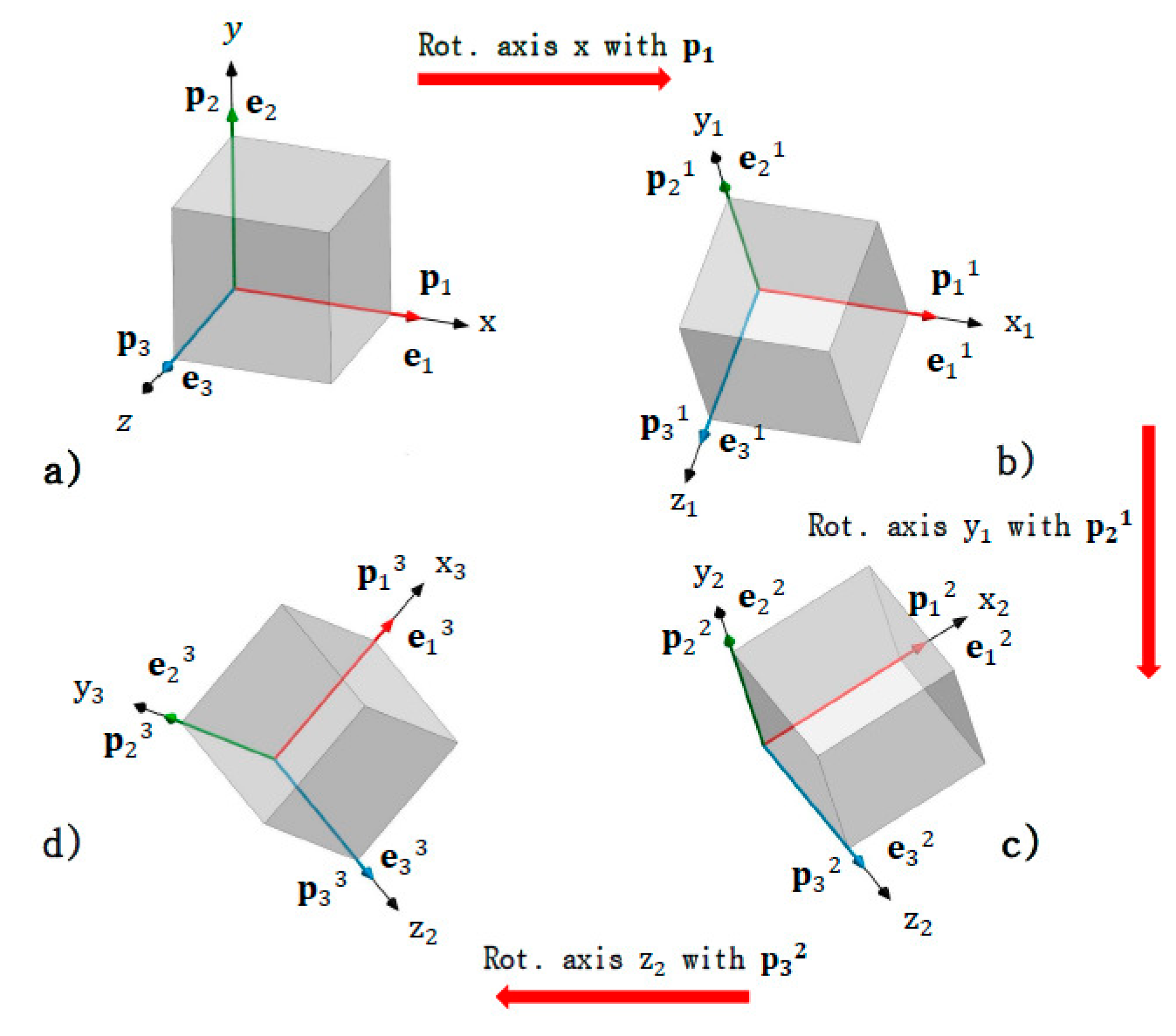

- 1)

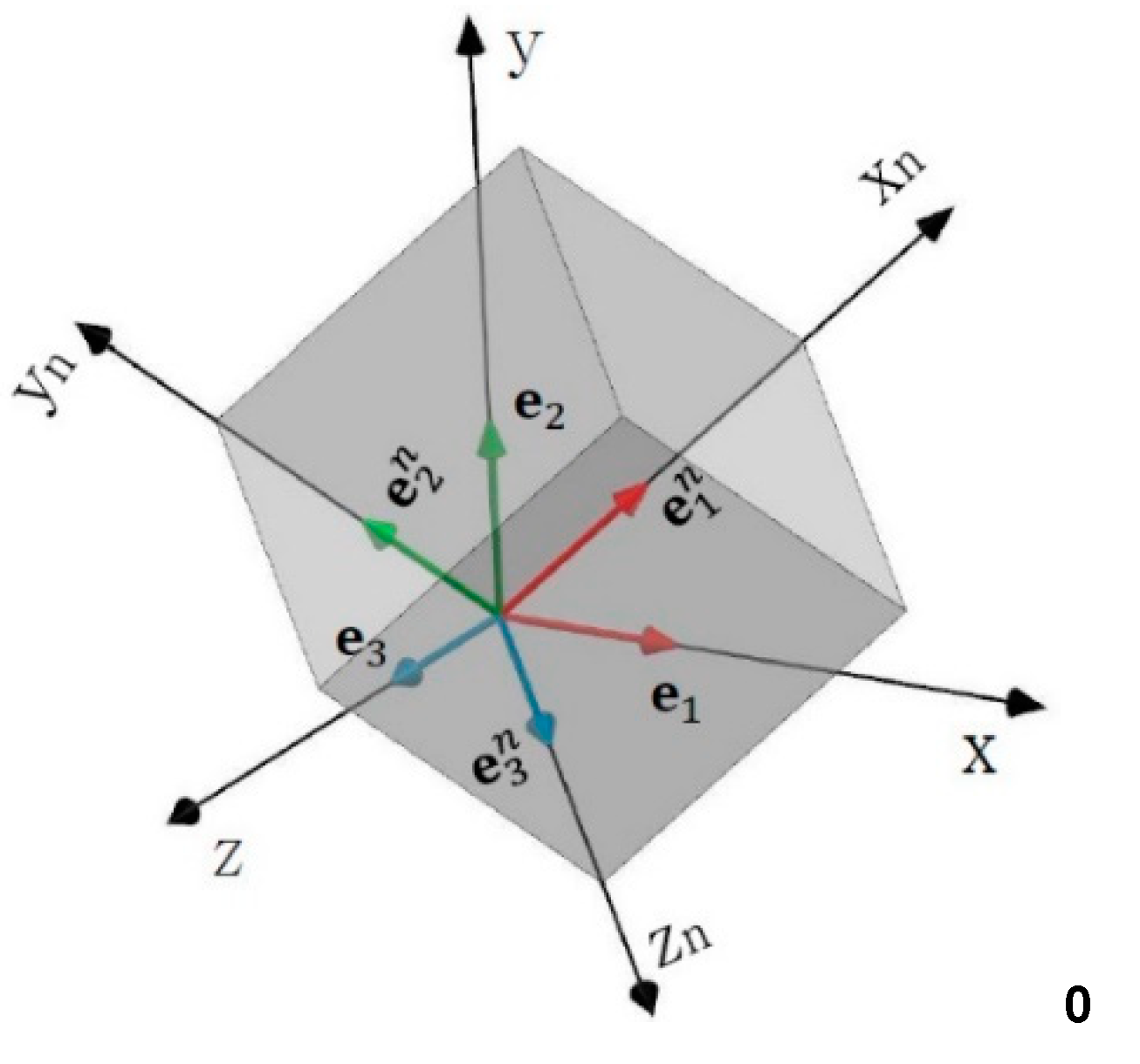

- Quaternions p1, p2, p3, are associated to the axes x, y, z, respectively, which will rotate with the body as shown in Figure A.a.

- 2)

- The rotation in the x-axis is produced using the quaternion p1. The ej1 basis elements and the quaternions experience the rotation shown in Figure A.b.

- 3)

- Subsequently, the rotation in the y1 axis is produced using the quaternion p21 (previously rotated). The ej2 basis elements and the quaternions undergo the rotation shown in the Figure. A.c.

- 4)

- Finally, the rotation in the z2 axis is produced using the quaternion p32 (previously rotated). The ej3 basis elements and the quaternions undergo the rotation shown in Figure A.d.

References

- Pott, A.; Hiller, M. Kinematic Modeling, Linearization and First-Order Error Analysis, In: Parallel Manipulators, towards New Applications, 1st ed. Ed. Huapeng Wu., Ed. Intechopen, Croatia, 2008; pp. 155-174. [CrossRef]

- Merlet, J.; Gosselin, C. Parallel Mechanisms and Robots. In: Springer Handbook of Robotics, 1st Ed., Siciliano, B.; Khatib, O., Eds. Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg, 2008, pp. 269-285.

- Himam, S. ; Satish.; G.; Subba, N.V. Relative Kinematic Analysis of Serial and Parallel Manipulators, IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 2018, 455, 012040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olarra, A.; Axinte, D.; Uriarte, L.; Bueno, R. Machining with the WalkingHex: A walking parallel kinematic machine tool for in situ operations, CIRP Annals, 2017, 66: 361-364. [CrossRef]

- Baptiste, J. On the Improvements of a Cable-Driven Parallel Robot for Achieving Additive Manufacturing for Construction. In: Cable-Driven Parallel Robots. Mechanisms and Machine Science, Gosselin C., Cardou P., Bruckmann T., Pott A. (eds), vol 53. Springer, Cham. 2018, pp 353–363. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Shu, T.; Wen, X.; Tian, W. Dynamic Visual Servoing of A 6-RSS Parallel Robot Based on Optical CMM. J Intell Robot Syst 2021, 102, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersoy, O.; Yildirim, M. C.; Ahmad, A.; Yirmibesoglu, O. D.; Koroglu, N.; Bebek, O. Design and Kinematics of a 5-DOF Parallel Robot for Beating Heart Surgery, 2019 IEEE 4th International Conference on Advanced Robotics and Mechatronics (ICARM), Toyonaka, Japan, September, 2019, pp. 274-279. [CrossRef]

- Vaida, C.; Birlescus, I.; Pisla, A.; Ionut, U.; Tarnita, D.; Carbone, J. Systematic Design of a Parallel Robotic System for Lower Limb Rehabilitation, IEEE Access, 2020; 8: 34522-34537. [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Yue, F. Design and Analysis for a Three-Rotational-DOF Flight Simulator of Fighter-Aircraft. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2018, 31, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zheng, k.; Chen, Y.; Xu, M.; Wang, D. DOF and kinematics analysis of a 3-UPU parallel mechanism for telescope secondary mirror support, Proc. SPIE 12069, AOPC 2021: Novel Technologies and Instruments for Astronomical Multi-Band Observations, 120690C. Beijing, China, November. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sholanov, K.S. Kinematics of One-Loop Parallel Manipulators. In: Parallel Manipulators of Robots. Mechanisms and Machine Science, vol 92. Springer, Cham. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Han, H.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Han, K.; Li, Y. Acceleration analysis of 6-RR-RP-RR parallel manipulator with offset hinges by means of a hybrid method. Mech. Mach. Theory, 2022; 169: 104661. [CrossRef]

- Hamdoun, O.; El Bakkali, L.; Zahra, F. Analysis and Optimum Kinematic Design of a Parallel Robot, Procedia Engineering, 2017; 181: 214-220.

- Yao, S.; Li, H. ; Zeng. Vision-based adaptive control of a 3-RRR parallel positioning system. Sci. China Technol. Sci, 2018; 61: 1253–1264. [CrossRef]

- Baron, N.; Philippides, A.; Rojas, N. A Geometric Method of Singularity Avoidance for Kinematically Redundant Planar Parallel Robots. In: Advances in Robot Kinematics. ARK 2018. Springer Proceedings in Advanced Robotics, Lenarcic, J.; Parenti, V. (eds), vol 8. Springer, Cham. 2019, pp. 187-194. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Xie, F.; Liu, X.; Takeda, Y. Screw Theory-Based Motion/Force Transmissibility Analysis of High-Speed Parallel Robots with Articulated Platforms. J. Mechanisms Robotics, 2020; 12: 041011. [CrossRef]

- Chai, X.; Wang, M.; Xu, L.; Ye, W. Dynamic Modeling and Analysis of a 2PRU-UPR Parallel Robot Based on Screw Theory, IEEE Access, 2020; 8: 78868-78878. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, E.; Servín de la Mora, D.; Servín de la Mora, R.; Ochoa, F.; Acosta, M.; Luna, G. Modeling in Two Configurations of a 5R 2-DoF Planar Parallel Mechanism and Solution to the Inverse Kinematic Modeling Using Artificial Neural Network, IEEE Access, 2021; 9: 68583-68594. [CrossRef]

- Thiruvengadam, S.; Tan, J.S. ; Miller., K.A. Generalised Quaternion and Clifford Algebra Based Mathematical Methodology to Effect Multi-stage Reassembling Transformations in Parallel Robots”. Adv. Appl. Clifford Algebras, 2021, 31, 39. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Li, Q.; Jiang, X. Dynamic rotational trajectory planning of a cable-driven parallel robot for passing through singular orientations, Mech. Mach. Theory, 2021; 158: 104223. April. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Noppeney, V.; Boaventura, T.; Siqueira, A. Task-space impedance control of a parallel Delta robot using dual quaternions and a neural network. J Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2021; 43: 440. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Kong, X.; Yu, J. Operation mode analysis of lower-mobility parallel mechanisms based on dual quaternions, Mechanism and Machine Theory, 2019, 152: 103577. [CrossRef]

- Dantam, N. Robust and efficient forward, differential, and inverse kinematics using dual quaternions, Int. J Rob. Res, 2020, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, E.; Servín de la Mora, D.; Reyes, L.; Servín de la Mora, R.; Melendez, J.; López, A. A. Modeling of Inverse Kinematic of 3-DoF Robot, Using Unit Quaternions and Artificial Neural Network”, Robotica; 2021; 39: 1230-1250. [CrossRef]

- Reyes, R. Quaternions: Une Representation Parametrique Systematique Des Rotation Finies. Partie I: Le Cadre Theorique,” In: Rapport de Recherche 1303 INRIA Rocquencourt France. 1990.

- Reyes. R. Quaternions: Une Representation Parametrique Systematique Des Rotation Finies. Partie II: Quelques Application, In: Rapport de Recherche 1454 INRIA Rocquencourt France. 1991.

- Murray, A.; Pierrot, F.; Dauchez, P.; McCarthy, J. A planar quaternion approach to the kinematic synthesis of a parallel manipulator, Robotica, 1997, 15(4): 361-365. [CrossRef]

- Ruggiu, M.; Kong, X. Reconfiguration Analysis of a 3-DOF Parallel Mechanism. Robotics,. 2019, 8: 66.. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, H.; Liu, H.; Chen, B.; Yao, J.; Wang, Y. Forward kinematics for 6-UPS parallel robot using extra displacement sensor. Journal of Advanced Mechanical Design, Systems, and Manufacturing, 2018, 12(7): 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Birlescu, I.; Husty, M.; Vaida, C.; Gherman, B.; Tucan, P.; Pisla, D. Joint-Space Characterization of a Medical Parallel Robot Based on a Dual Quaternion Representation of SE(3). Mathematics, 2020, 8: 1086. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Kong, X.; Yu, J. Operation mode analysis of lower-mobility parallel mechanisms based on dual quaternions. Mech. Mach. Theory, 2019, 142, 103577. [CrossRef]

- Nigatu, H.; Kim, D. Optimization of 3-DoF Manipulators’ Parasitic Motion with the Instantaneous Restriction Space-Based Analytic Coupling Relation. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Parhi, D. Dynamic walking of multi-humanoid robots using BFGS Quasi-Newton method aided Artificial potential field approach for uneven terrain, Soft Comput, 2022: 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Sun, L. , Wang, Z.; Chen, G. A speedup method for solving the inverse kinematics problem of robotic manipulators. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst.. 2022: 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Haibo, Q.; Yuefa, F.; Sheng, G. Theory of Degrees of Freedom for Parallel Mechanisms with Three Spherical Joints and Its Applications, Chin. J. Mech. Eng., 2015, 28 (4): 737-746.

- Abdelrahman, S.; Nada, M.; Salem, A.; Hossam, H. Modeling of Nonlinear 3-RRR Planar Parallel Manipulator: Kinematics and Dynamics Experimental Analysis, Int. J. Mech. Mechatron. Eng., 2020, 20 (5): 175-185.

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Shao, Z. Improving the kinematic performance of a planar 3-RRR parallel manipulator through actuation mode conversion, Mech. Mach. Theory, 2018, 130: 86-108.

- Lianchao, S. , Wei, L. Optimization Design by Genetic Algorithm Controller for Trajectory Control of a 3-RRR Parallel Robot, Algorithms,. 2018, 11, (1): 7.. [CrossRef]

- Sayed, A.S.; Azar, A. T.; Ibrahim, Z.F.; Ibrahim, H.A.; Mohamed, N. A.; Ammar, H.H. Deep Learning Based Kinematic Modeling of 3-RRR Parallel Manipulator. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Vision (AICV2020). AICV 2020. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, Hassanien A.E.; Azar A.; Gaber T.; Oliva D.; Tolba F. (eds), vol 1153. Springer, Cham. 2020, pp. 308-321. [CrossRef]

- Al, A.; Aldair, A.A.; Chatwin, C. Control of a 3-RRR Planar Parallel Robot Using Fractional Order PID Controller. Int. J. Autom. Comput. 2020, 17: 822–836. [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Arakelian, V. Partial Shaking Force Balancing of 3-RRR Parallel Manipulators by Optimal Acceleration Control of the Total Center of Mass. In: Multibody Dynamics 2019. ECCOMAS 2019. Computational Methods in Applied Sciences, Kecskeméthy A.; Geu, F. (eds), vol 53. Springer, Cham. 2019, pp. 375-382. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Chen, K.; Gao, H. ; Xiao, P; Wang, L. Small-angle perturbation method for moving platform orientation to avoid singularity of asymmetrical 3-RRR planner parallel manipulator. J Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng, 2019, 41, 538. [CrossRef]

- Hoang, N. Q.; Vuong, V.D. Inverse Kinematics and Dynamics of a 3RRR Planar Parallel Manipulator in the Presence of Singularities. In: Advances in Asian Mechanism and Machine Science. ASIAN MMS 2021. Mechanisms and Machine Science, Khang, N.V.; Hoang, N.Q.; Ceccarelli M. (eds), vol 113. Springer, Cham. 2021, pp. 228-237. [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.S.; Root, R.R.; Sandgren, E. A Dependable Method for Solving Matrix Loop Equations for The General Three-Dimensional Mechanism, J. Eng. Ind., 1977: 547-550.

- Fischer, I. S.; Paul, R.N. Kinematic Displacement Analysis of a Double-Cardan-Joint Driveline. ASME. J. Mech. Des, 1991, 113(3): 263–271.

- Wolfram Mathematica ® Tutorial Collection Unconstrained Optimization, United States of America, 2008.

- Chen, Z.; Hung, J.C. Application of Quaternion in Robot Control, IFAC Proceedings Volumes, 1987; 20: 259-263. 20. [CrossRef]

- Gouasmi, M.; Ouali, M.; Brahim, F. Robot Kinematics Using Dual Quaternions, Int. J. Robot. Autom., 2021; 1: 13-30.

- Valverde, A.; Tsiotras, P. Spacecraft Robot Kinematics Using Dual Quaternions. Robotics, 2018, 7, 64. [CrossRef]

- Adorno, B. V.; Marques, M. DQ Robotics: A Library for Robot Modeling and Control. IEEE robot. autom. mag., 2020, 28, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Yu, M.; Chen, F. Inverse Kinematic Solution of 6-DOF Robot-Arm Based on Dual Quaternions and Axis Invariant Methods. Arab. J. Sci. Eng., 2022. 47: 15915–15930. [CrossRef]

- Lechuga, L.; Macias, E.; Martínez, G.; Zamora, J.; Bayro, B. Iterative inverse kinematics for robot manipulators using quaternion algebra and conformal geometric algebra. Meccanica, 2022, 57, 1413–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, C. H.; Radcliffe, C.W. Kinematics and Mechanism Design. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY, 1978.

- Merlet, J. Les Robots Parallèles. Traité des Nouvelles Technologies - série Robotique. Hermès, Paris, 1990.

- Shigley, J. E. Elementos de Maquinaria. Mecanismos. McGraw Hill, México, 1995.

- Davidon, W.C. Variable metric method for minimization, A.E.C. Research and Development Rept. ANL-5990. 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Mamat, M.; Dauda, M.K.; Mohamed, M.A.; Waziri, M.Y.; Mohamad, F.S.; Abdullah, H. Derivative free Davidon-Fletcher-Powell (DFP) for solving symmetric systems of nonlinear equations, IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 332, 012030. [CrossRef]

- Shoham, M.; Li, CJ.; Hacham, Y.; Kreindler, E.; Weill, R. Neural Network Control of Robot Arms. CIRP Annals, 1992, 41(1): 407–410. [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, J.A. Implementation of Quasi-Newton Methods, Thesis, Bachelor's Degree in Applied Mathematics, Faculty of Mathematical-Physical Sciences. Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. México, 2019.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).