Submitted:

08 April 2025

Posted:

11 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Database

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Rumen Parameters

3.2. Digestibility

3.3. Blood Parameters

4. Discussion

4.1. Rumen Parameters

4.2. Digestibility

4.3. Blood Parameters

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duffield, T.F.; Merrill, J.K.; Bagg, R.N. Meta-analysis of the effects of monensin in beef cattle on feed efficiency, body weight gain, and dry matter intake. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 90, 4583–4592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Union. Regulation (EC) No 124/2009. 2009. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32009R0124&from=EL.

- Martin, S.A.; Streeter, M.N. Effect of malate on in vitro mixed ruminal microorganism fermentation. J. Anim. Sci. 1995, 73, 2141–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carro, M.D.; Ranilla, M.J. Effect of the addition of malate on in vitro rumen fermentation of cereal grains. Br. J. Nutr. 2003, 89, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, C.; Benedito, J.L.; Pereira, V.; Méndez, J.; Vazquez, P.; López-Alonso, M.; Hernández, J. Effects of malate supplementation on acid-base balance and productive performance in growing/finishing bull calves fed a high-grain diet. Arch. Anim. Nutr. 2007, 62, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, L.; Huber, J.T.; Krummrey, J.D.; Allison, L.; Cook, R.M. Influence of adding malic acid to dairy cattle rations on milk production, rumen volatile acids, digestibility, and nitrogen utilization. J. Dairy Sci. 1982, 65(7), 1170–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khampa, S.; Wanapat, M.; Wachirapakorn, C.; Nontaso, N.; Wattiaux, M.; Rowlison, P. Effect of levels of sodium DL-malate supplementation on ruminal fermentation efficiency of concentrates containing high levels of cassava chip in dairy steers. Anim. Biosci. 2006, 19, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, C.; Yang, W.; Dong, Q.; Dong, K.; Huang, Y.; He, D. Effects of malic acid on rumen fermentation, urinary excretion of purine derivatives and feed digestibility in steers. Animal 2009, 3, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, S.A.; Streeter, M.N.; Nisbet, D.J.; Hill, G.M.; Williams, S.E. Effects of DL-malate on ruminal metabolism and performance of cattle fed a high-concentrate diet. J. Anim. Sci. 1999, 77, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Zaiat, H.M.; Kholif, A.E.; Mohamed, D.A.; Matloup, O.H.; Anele, U.Y.; Sallam, S.M.A. Enhancing lactational performance of Holstein dairy cows under commercial production: Malic acid as an option. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, C.; Benedito, J.L.; Pereira, V.; Vázquez, P.; López Alonso, M.; Méndez, J.; Hernández, J. Malic acid supplementation in growing/finishing feedlot bull calves: Influence of chemical form on blood acid–base balance and productive performance. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2007, 135, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, C.; Medel, P.; Fuentetaja, A.; Carro, M.D. Effect of malate form (acid or disodium/calcium salt) supplementation on performance, ruminal parameters and blood metabolites of feedlot cattle. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2012, 176, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, J.; Sampson, M.; Salzwedel, D.M.; Cogo, E.; Foerster, V.; Lefebvre, C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 75, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DerSimonian, R.; Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials revisited. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2015, 45, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J. P., & Thompson, S. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ, 327(7414), 557–560. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Beauchemin, K. A. (2018). Invited review: Current perspectives on eating and rumination activity in dairy cows. Journal of Dairy Science, 101(6), 4762–4784. [CrossRef]

- Callaway, T. R., Martin, S. A., Wampler, J. L., Hill, N. S., & Hill, G. M. (1997). Malate content of forage varieties commonly fed to cattle. Journal of Dairy Science, 80(8), 1651–1655. [CrossRef]

- Evans, J. D., & Martin, S. A. (1997). Factors affecting lactate and malate utilization by Selenomonas ruminantium. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 63(12), 4853–4858. [CrossRef]

- Callaway, T. R., & Martin, S. A. (1996). Effects of organic acid and monensin treatment on in vitro mixed ruminal microorganism fermentation of cracked corn. Journal of Animal Science, 74(8), 1982–1989. [CrossRef]

- Bach, A., Calsamiglia, S., & Stern, M. D. (2005). Nitrogen metabolism in the rumen. Journal of Dairy Science, 88, E9–E21. [CrossRef]

- Wanapat, M., Gunun, P., Anantasook, N., & Kang, S. (2014). Changes of rumen pH, fermentation and microbial population as influenced by different ratios of roughage (rice straw) to concentrate in dairy steers. The Journal of Agricultural Science, 152(4), 675–685. [CrossRef]

- Kozloski, G. V., Trevisan, L. M., Bonnecarrère, L. M., Härter, C. J., Fiorentini, G., Galvani, D. B., & Pires, C. C. (2006). Níveis de fibra em detergente neutro na dieta de cordeiros: Consumo, digestibilidade e fermentação ruminal. Arquivo Brasileiro de Medicina Veterinária e Zootecnia, 58(5), 893–900. [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, J., Ellis, J. L., Kebreab, E., Strathe, A. B., López, S., France, J., & Bannink, A. (2012). Ruminal pH regulation and nutritional consequences of low pH. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 172(1–2), 22–33. [CrossRef]

- Morvan, B., Rieu-Lesme, F., Fonty, G., & Gouet, P. (1996). In vitro interactions between rumen H2-producing cellulolytic microorganisms and H2-utilizing acetogenic and sulfate-reducing bacteria. Anaerobe, 2(3), 175–180. [CrossRef]

- Papatsiros, V., Katsoulos, P., Koutoulis, K., Karatzia, M., Dedousi, A., & Christodoulopoulos, G. (2013). Alternatives to antibiotics for farm animals. CAB Reviews: Perspectives in Agriculture, Veterinary Science, Nutrition and Natural Resources, 8. [CrossRef]

- Øverland, M., Granli, T., Kjos, N. P., Fjetland, O., Steien, S. H., & Stokstad, M. (2000). Effect of dietary formates on growth performance, carcass traits, sensory quality, intestinal microflora, and stomach alterations in growing-finishing pigs. Journal of Animal Science, 78(7), 1875–1884. [CrossRef]

- Hua, D., Hendriks, W. H., Xiong, B., & Pellikaan, W. F. (2022). Starch and cellulose degradation in the rumen and applications of metagenomics on ruminal microorganisms. Animals, 12(21), 3020. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Shi, H. T., Wang, Y. C., Li, S. L., Cao, Z. J., Yang, H. J., & Wang, Y. J. (2020). Carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism and oxidative status in Holstein heifers precision-fed diets with different forage to concentrate ratios. Animal, 14(11), 2315–2325. [CrossRef]

- Huntington, G. B., & Archibeque, S. L. (1999). Practical aspects of urea and ammonia metabolism in ruminants. In Proceedings of the American Society of Animal Science (pp. 1–11).

- Adewuyi, A. A., Gruys, E., & van Eerdenburg, F. J. C. M. (2005). Non esterified fatty acids (NEFA) in dairy cattle: A review. Veterinary Quarterly, 27(3), 117–126. [CrossRef]

- Sniffen, C. J., Ballard, C. S., Carter, M. P., Cotanch, K. W., Dann, H. M., Grant, R. J., Mandebvu, P., Suekawa, M., & Martin, S. A. (2006). Effects of malic acid on microbial efficiency and metabolism in continuous culture of rumen contents and on performance of mid-lactation dairy cows. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 127(1–2), 13–31. [CrossRef]

- Devant, M., Bach, A., & García, J. A. (2007). Effect of malate supplementation to dairy cows on rumen fermentation and milk production in early lactation. Journal of Applied Animal Research, 31(2), 169–172. [CrossRef]

- Foley, P. A., Kenny, D. A., Lovett, D. K., Callan, J. J., Boland, T. M., & O’Mara, F. P. (2009). Effect of dl-malic acid supplementation on feed intake, methane emissions, and performance of lactating dairy cows at pasture. Journal of Dairy Science, 92(7), 3258–3264. [CrossRef]

- Wang, c., Liu, Q., Yang, W. Z., Dong, Q., Yang, X. M., He, D. C., Dong, K. H., & Huang, Y. X. (2009). Effects of malic acid on feed intake, milk yield, milk components and metabolites in early lactation Holstein dairy cows. Livestock Science, 124(1–3), 182–188. [CrossRef]

- Hernández, J., Castillo, C., Méndez, J., Pereira, V., Vázquez, P., López Alonso, M., Vilariño, O., & Benedito, J. L. (2011). The influence of chemical form on the effects of supplementary malate on serum metabolites and enzymes in finishing bull calves. Livestock Science, 137(1–3), 260–263. [CrossRef]

- Vyas, D., Beauchemin, K. A., & Koenig, K. M. (2015). Using organic acids to control subacute ruminal acidosis and fermentation in feedlot cattle fed a high-grain diet. Journal of Animal Science, 93(8), 3950–3958.

- Malekkhahi, M., Tahmasbi, A. M., Naserian, A. A., Danesh-Mesgaran, M., Kleen, J. L., AlZahal, O., & Ghaffari, M. H. (2016). Effects of supplementation of active dried yeast and malate during sub-acute ruminal acidosis on rumen fermentation, microbial population, selected blood metabolites, and milk production in dairy cows. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 213, 29–43. [CrossRef]

| Author | Form | Main Cereal | Main forrage | Dose (g/day) | CP (%) | NDF (%) | ADF (%) | Starch (%) | EE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kung Jr. et al. 1982 A | Acid | Corn | Corn silage | 70.00 | 11.18 | 24.71 | 13.95 | 35.77 | 1.99 |

| Kung Jr. et al. 1982 B | Acid | Corn | Corn silage | 105.00 | 11.18 | 24.71 | 13.95 | 35.77 | 1.99 |

| Kung Jr. et al. 1982 C | Acid | Corn | Corn silage | 140.00 | 11.18 | 24.71 | 13.95 | 35.77 | 1.99 |

| Kung Jr. et al. 1982 D | Acid | Corn | Corn silage | 42.00 | 8.76 | 25.54 | 13.76 | 46.78 | 2.77 |

| Kung Jr. et al. 1982 E | Acid | Corn | Corn silage | 84.00 | 8.76 | 25.54 | 13.76 | 46.78 | 2.77 |

| Martin et al. 1999 A | Saltt | Corn | Cottonseed hulls | 27.00 | 11.39 | 19.10 | 9.93 | 49.60 | 2.95 |

| Martin et al. 1999 B | Saltt | Corn | Cottonseed hulls | 54.00 | 11.39 | 19.10 | 9.93 | 49.60 | 2.95 |

| Martin et al. 1999 C | Saltt | Corn | Cottonseed hulls | 80.00 | 11.39 | 19.10 | 9.93 | 49.60 | 2.95 |

| Sniffen et al. 2006 | Saltt | Corn | Corn silage | 50.00 | 18.20 | 31.80 | 21.40 | 29.40 | 2.70 |

| Khampa et al. 2006 A | Saltt | Cassava | Rice straw | 9.00 | 8.61 | 41.14 | 23.86 | 34.90 | 3.51 |

| Khampa et al. 2006 B | Saltt | Cassava | Rice straw | 18.00 | 8.61 | 41.14 | 23.86 | 34.90 | 3.51 |

| Khampa et al. 2006 C | Saltt | Cassava | Rice straw | 27.00 | 8.61 | 41.14 | 23.86 | 34.90 | 3.51 |

| Devant et al. 2007 | Saltt | - | - | 84.00 | 14.31 | 32.84 | 16.93 | 30.16 | 3.16 |

| Foley et al. 2009 A | Acid | Barley | Silage | 34.00 | 15.60 | 23.10 | 13.80 | 28.10 | 2.50 |

| Foley et al. 2009 B | Acid | Barley | Silage | 65.40 | 15.60 | 23.10 | 13.80 | 28.10 | 2.50 |

| Foley et al. 2009 C | Acid | Barley | Silage | 32.38 | 15.57 | 23.09 | 13.82 | 28.12 | 2.47 |

| Foley et al. 2009 D | Acid | Barley | Silage | 64.85 | 15.57 | 23.09 | 13.82 | 28.12 | 2.47 |

| Foley et al. 2009 E | Acid | Barley | Silage | 98.25 | 15.57 | 23.09 | 13.82 | 28.12 | 2.47 |

| Wang et al. 2009 A | Acid | Corn | Corn silage | 70.00 | 16.50 | 42.40 | 27.10 | 31.70 | 1.50 |

| Wang et al. 2009 B | Acid | Corn | Corn silage | 140.00 | 16.50 | 42.40 | 27.10 | 31.70 | 1.50 |

| Wang et al. 2009 C | Acid | Corn | Corn silage | 210.00 | 16.50 | 42.40 | 27.10 | 31.70 | 1.50 |

| Liu et al. 2009 A | Acid | Corn | Corn straw | 70.20 | 8.29 | 55.82 | 21.85 | 14.78 | 1.72 |

| Liu et al. 2009 B | Acid | Corn | Corn straw | 140.40 | 8.29 | 55.82 | 21.85 | 14.78 | 1.72 |

| Liu et al. 2009 C | Acid | Corn | Corn straw | 210.60 | 8.29 | 55.82 | 21.85 | 14.78 | 1.72 |

| Hernández et al. 2011 A | Salt | Barley | Barley straw | 30.80 | 13.83 | 37.30 | 16.62 | 28.51 | 3.87 |

| Hernández et al. 2011 B | Acid | Barley | Barley straw | 26.80 | 13.83 | 37.30 | 16.62 | 28.51 | 3.87 |

| Hernández et al. 2011 C | Salt | Barley | Barley straw | 28.40 | 13.83 | 37.30 | 16.62 | 28.51 | 3.87 |

| Carrasco et al. 2012 A | Acid | Barley | Barley straw | 9.38 | 16.61 | 21.59 | 8.35 | 37.04 | 9.76 |

| Carrasco et al. 2012 B | Salt | Barley | Barley straw | 9.12 | 16.61 | 21.59 | 8.35 | 37.04 | 9.76 |

| Vyas et al. 2015 A | Acid | Barley | Barley silage | 89.00 | 9.74 | 16.86 | 6.57 | 45.32 | 1.57 |

| Vyas et al. 2015 B | Acid | Barley | Barley silage | 177.00 | 9.74 | 16.86 | 6.57 | 45.32 | 1.57 |

| Malekkhahi et al. 2016 A | Salt | Corn | Corn silage | 80.00 | 17.69 | 27.64 | 16.66 | 29.90 | 2.23 |

| Malekkhahi et al. 2016 B | Salt | Corn | Corn silage | 80.00 | 20.93 | 32.50 | 18.25 | 45.53 | 2.74 |

| El-Zaiat et al. 2019 | Acid | Corn | Corn silage | 30.00 | 17.16 | 32.29 | 19.06 | 36.70 | 5.60 |

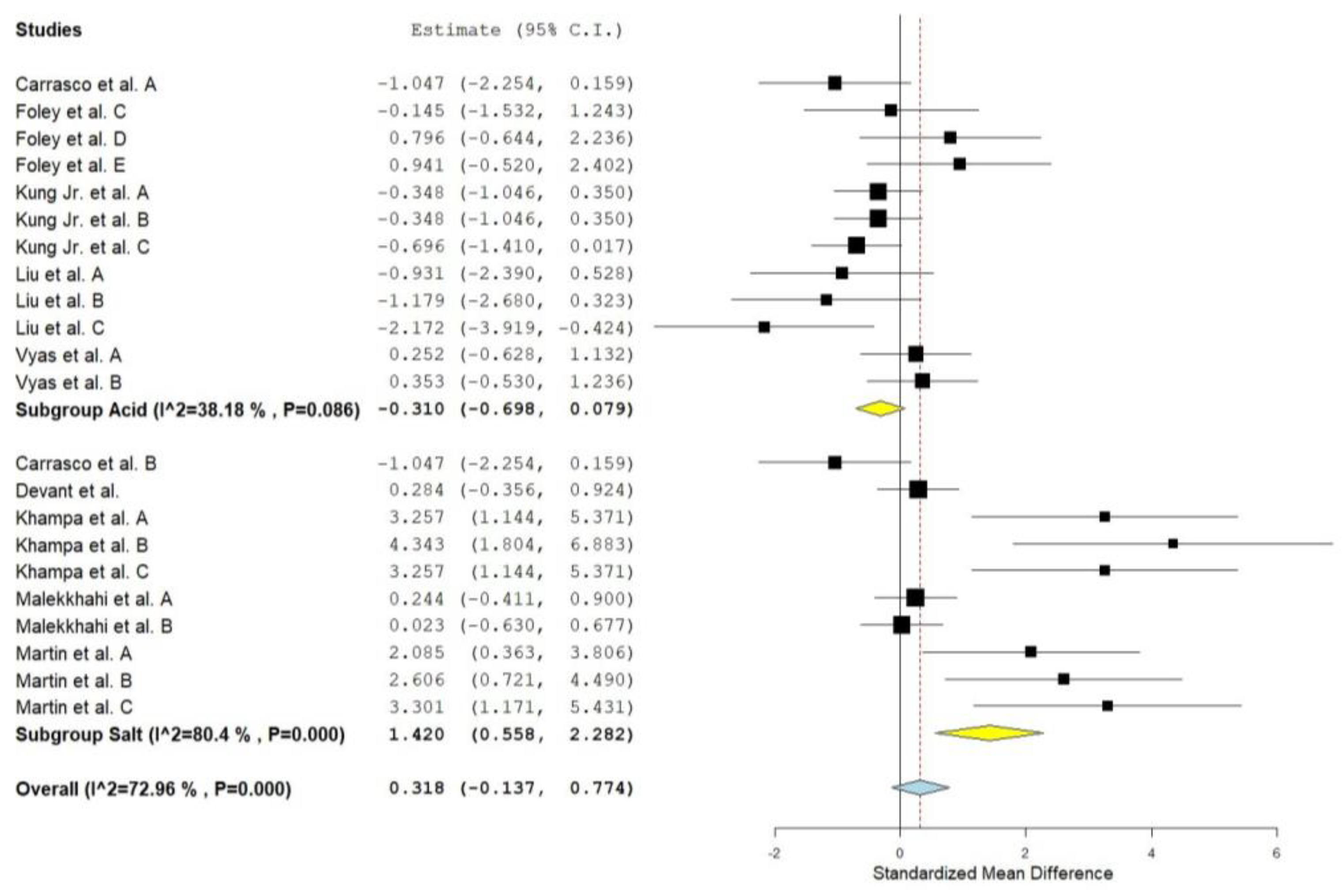

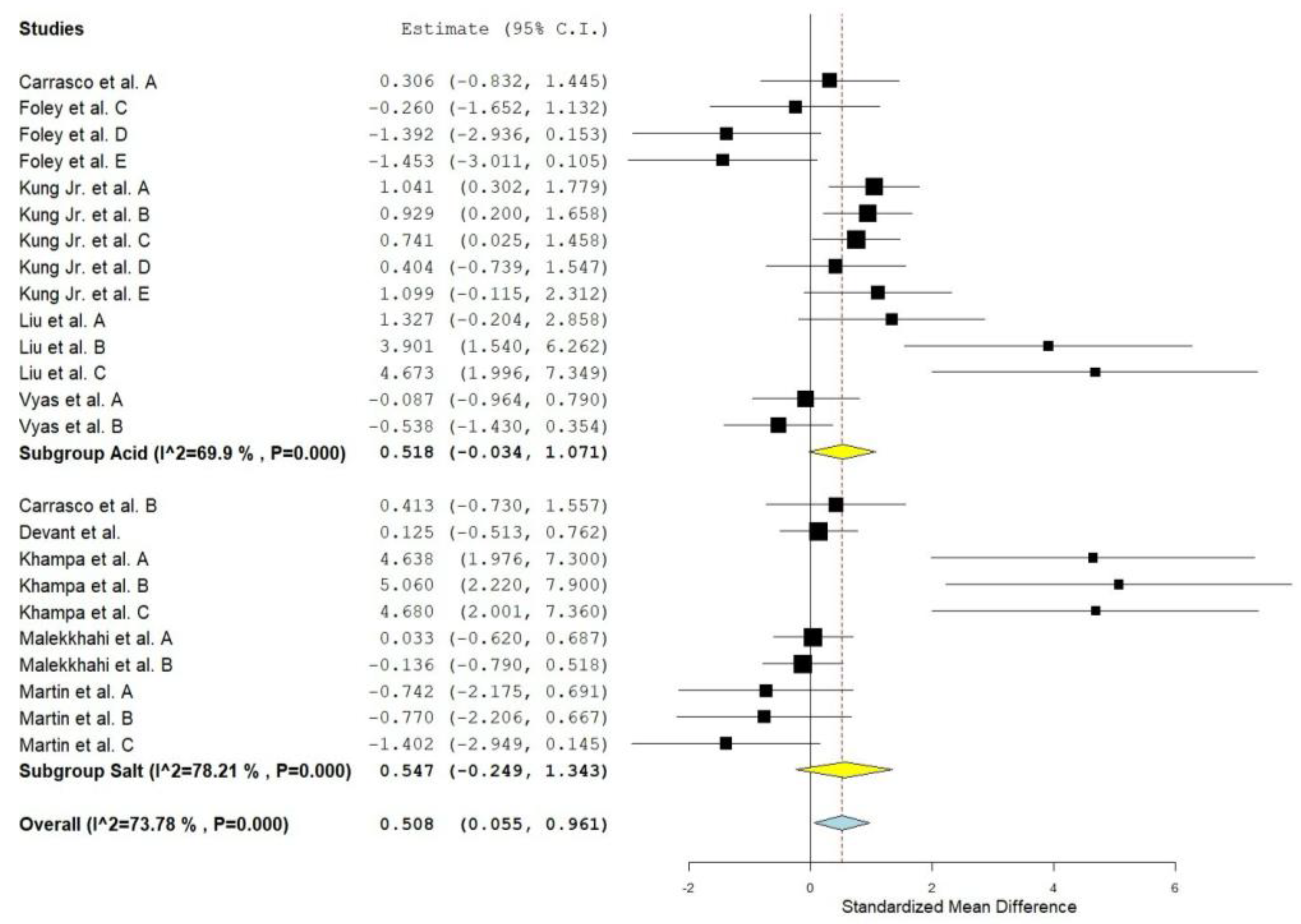

| Variable | Form | n | ES(CI) | ES p-value | I2 | Het p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | Salt | 11 | 1.420 (0.558; 2.282) | 0.00 | 80.40 | <0.01 |

| Acid | 12 | -0.310 (-0.698; 0.079) | 0.12 | 38.18 | 0.09 | |

| Overall | 23 | 0.310 (-0.137; 0.774) | 0.17 | 72.95 | <0.01 | |

| Acetate | Salt | 11 | -0.592 (-1.381; 0.196) | 0.14 | 72.26 | <0.01 |

| Acid | 14 | 0.167 (-0.386; 0.720) | 0.55 | 78.08 | <0.01 | |

| Overall | 25 | -0.120 (-0.584; 0.345) | 0.61 | 76.34 | <0.01 | |

| Butyrate | Salt | 11 | -0.356 (-1.040; 0.328) | 0.31 | 72.84 | <0.01 |

| Acid | 14 | -0.058 (-0.717; 0.601) | 0.86 | 78.39 | <0.01 | |

| Overall | 25 | -0.178 (-0.653; 0.297) | 0.46 | 76.69 | <0.01 | |

| Propionate | Salt | 11 | 0.756 (-0.075; 1.588) | 0.08 | 80.10 | <0.01 |

| Acid | 14 | 0.472 (0.066; 0.879) | 0.02 | 48.17 | 0.02 | |

| Overall | 25 | 0.560 (0.160; 0.959) | 0.01 | 67.31 | <0.01 | |

| Lactate | Salt | 6 | 0.337 (-0.517; 1.191) | 0.44 | 67.60 | 0.01 |

| Acid | 6 | -0.621 (-1.512; 0.270) | 0.17 | 74.94 | <0.01 | |

| Overall | 12 | -0.113 (-0.711; 0.485) | 0.71 | 70.76 | <0.01 | |

| ACT:PRP | Salt | 9 | -1.327 (-2.683; 0.030) | 0.06 | 82.04 | <0.01 |

| Acid | 6 | -1.109 (-2.470; 0.252) | 0.11 | 83.70 | <0.01 | |

| Overall | 15 | -1.130 (-2.028; -0.232) | 0.01 | 81.68 | <0.01 | |

| NH3N | Salt | 8 | 0.161 (-0.170; 0.492) | 0.34 | 0.99 | 0.42 |

| Acid | 12 | -0.089 (-0.560; 0.381) | 0.71 | 47.12 | 0.04 | |

| Overall | 20 | 0.079 (-0.227; 0.385) | 0.61 | 36.62 | 0.05 | |

| Total VFA | Salt | 11 | 0.547 (-0.249; 1.343) | 0.18 | 78.21 | <0.01 |

| Acid | 14 | 0.518 (-0.034; 1.071) | 0.07 | 69.90 | <0.01 | |

| Overall | 25 | 0.508 (0.055; 0.961) | 0.03 | 73.78 | <0.01 |

| Trait | Form | Std | ES(CI) | p-value | I2 | Het p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood parameters | ||||||

| Glucose | Salt | 7 | 0.163 (-0.132; 0.457) | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.88 |

| Acid | 9 | 0.173 (-0.034; 0.379) | 0.10 | 0.49 | 0.43 | |

| Overall | 16 | 0.170 (0.002; 0.338) | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.78 | |

| Urea | Salt | 7 | 0.028 (-0.385; 0.441) | 0.89 | 45.12 | 0.11 |

| Acid | 8 | -0.109 (-0.413; 0.194) | 0.48 | 53.35 | 0.04 | |

| Overall | 15 | -0.033 (-0.279; 0.212) | 0.79 | 47.24 | 0.03 | |

| Lactate | Salt | 7 | -0.060 (-0.956; 0.836) | 0.90 | 82.63 | <0.01 |

| Acid | 2 | -1.661 (-2.690; -0.361) | 0.01 | 57.23 | 0.13 | |

| Overall | 9 | -0.490 (-1.316; 0.337) | 0.25 | 83.31 | <0.01 | |

| NEFA | Salt | 2 | -0.024 (-0.597; 0.550) | 0.94 | 0.00 | 0.94 |

| Acid | 7 | -0.626 (-1.065; -0.187) | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.47 | |

| Overall | 9 | -0.404 (-0.759; -0.049) | 0.03 | 3.56 | 0.40 | |

| ß-hidroxibutirato | Salt | 2 | 0.532 (-0.769; 1.832) | 0.42 | 78.81 | 0.03 |

| Acid | 7 | -0.260 (-1.172; 0.652) | 0.58 | 75.68 | 0.01 | |

| Overall | 9 | -0.018 (-0.742; 0.706) | 0.96 | 75.20 | <0.01 | |

| Digestibility | ||||||

| Dry matter | Salt | 5 | -0.084 (-0.575; 0.407) | 0.74 | 0.00 | 0.95 |

| Acid | 8 | 0.940 (0.229; 1.651) | 0.01 | 73.01 | 0.01 | |

| Overall | 13 | 0.547 (0.027; 1.067) | 0.04 | 78.74 | <0.01 | |

| Organic matter | Salt | 4 | 0.056 (-0.435; 0.546) | 0.82 | 0.00 | 0.99 |

| Acid | 5 | 0.694 (-0.217; 1.604) | 0.14 | 53.15 | 0.07 | |

| Overall | 9 | 0.308 (-0.148; 0.764) | 0.19 | 21.24 | 0.25 | |

| Protein | Salt | 5 | 1.168 (0.217; 2.118) | 0.02 | 52.70 | 0.10 |

| Acid | 8 | 0.215 (-0.197; 0.627) | 0.31 | 0.00 | 0.97 | |

| Overall | 13 | 0.422 (0.099; 0.745) | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.47 | |

| NDF | Salt | 5 | 1.537 (0.277; 2.797) | 0.02 | 77.39 | 0.00 |

| Acid | 6 | -0.085 (-0.576; 0.406) | 0.73 | 0.00 | 0.94 | |

| Overall | 11 | 0.699 (-0.007; 1.406) | 0.05 | 67.29 | 0.01 | |

| ADF | Salt | 4 | 0.547 (0.042; 1.051) | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.45 |

| Acid | 8 | 0.654 (-0.078; 1.387) | 0.08 | 60.62 | 0.01 | |

| Overall | 12 | 0.635 (0.148; 1.121) | 0.01 | 46.49 | 0.03 |

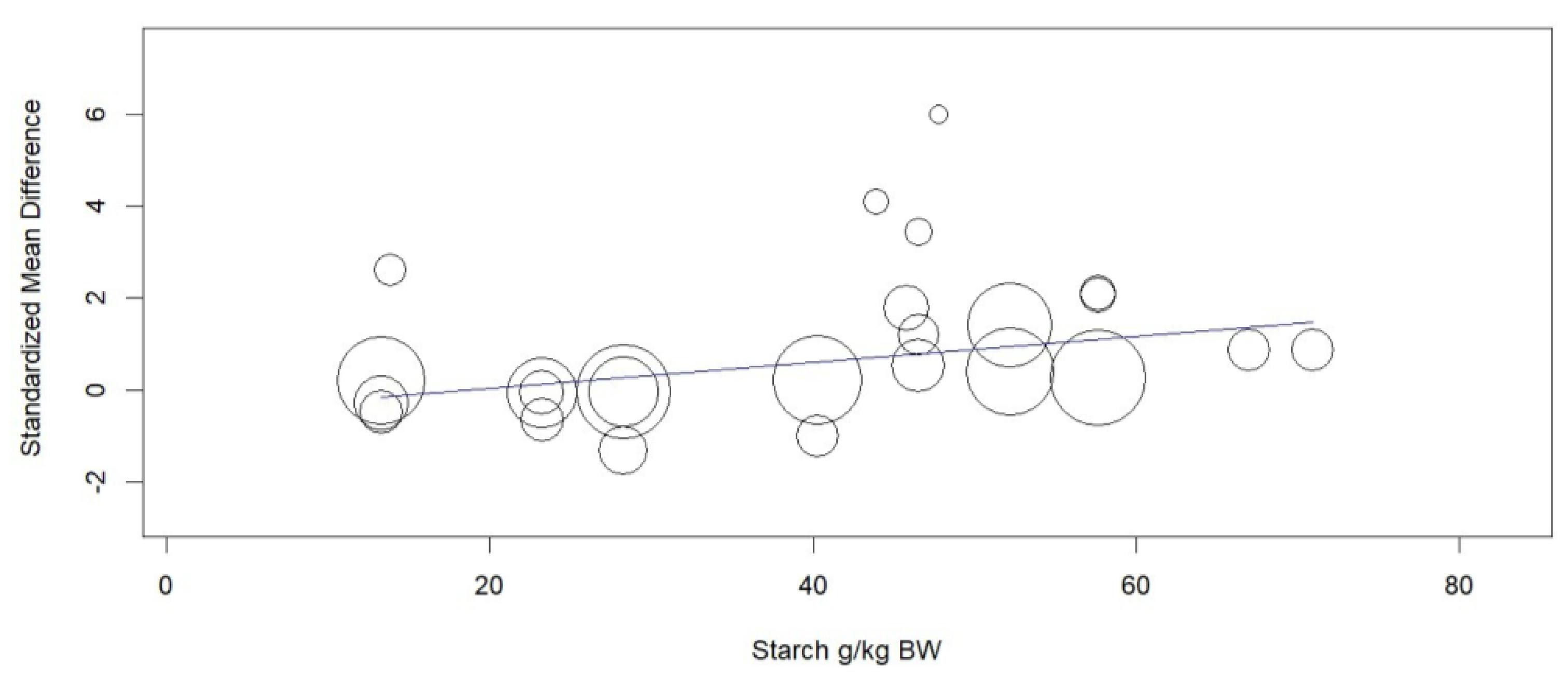

| Variables | Covariables, g/kg BW | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDF | ADF | Starch | Organic acid | |

| Rumen parameters | ||||

| pH | 2.063 -0.051x* | 0.908 -0.142 | 0.584 -0.004x | 0.343+ 0.548x |

| Acetate | 0.126 -0.008x | 0.464 -0.173x | -1.726 +0.039x** | -0.455+ 2.690x |

| Butyrate | -1.475 +0.038x | -1.155 +0.252x | -0.649 +0.009x | -1.121 +7.116x |

| Propionate | 0.239 +0.009x | 0.357 +0.055x | -0.518+0.028x** | 0.871 -2.894x |

| Lactate | 1.250 -0.041x* | 0.684 -0.242x | -1.462 +0.031xT | -0.547 +3.758x |

| Acetate:propionate | 1.887 -0.118x* | 3.057 -1.463x** | -7.483 +0.156x** | -3.000 +10.725x |

| NH3N | 1.337 -0.033x** | 0.854 -0.176x | -0.032 +0.002x | 0.262 -1.384x |

| Total VFA | -0.034 +0.019x | 0.632-0.013x | -1.033+0.042x* | 1.258 -5.318x |

| Blood parameters | ||||

| Urea | -0.074 +0.001x | -0.053 +0.005x | 0.370 -0.007x | 0.007 -0.190x |

| Digestibility | ||||

| Dry matter | -0.374 +0.023xT | 0.418 +0.021x | 0.673 -0.004x | 1.067 -6.511x |

| Protein | 0.613 -0.004x | 0.336 +0.016x | 0.483 -0.002x | 0.560 -1.665x |

| NDF | 0.135 +0.013x | 1.309 -0.171xT | 1.375 -0.025x* | 1.530 -13.733xT |

| ADF | 0.550 -0.002x | 0.695 -0.039x | 1.167 -0.016x | 0.795 -3.606x |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).