Submitted:

18 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

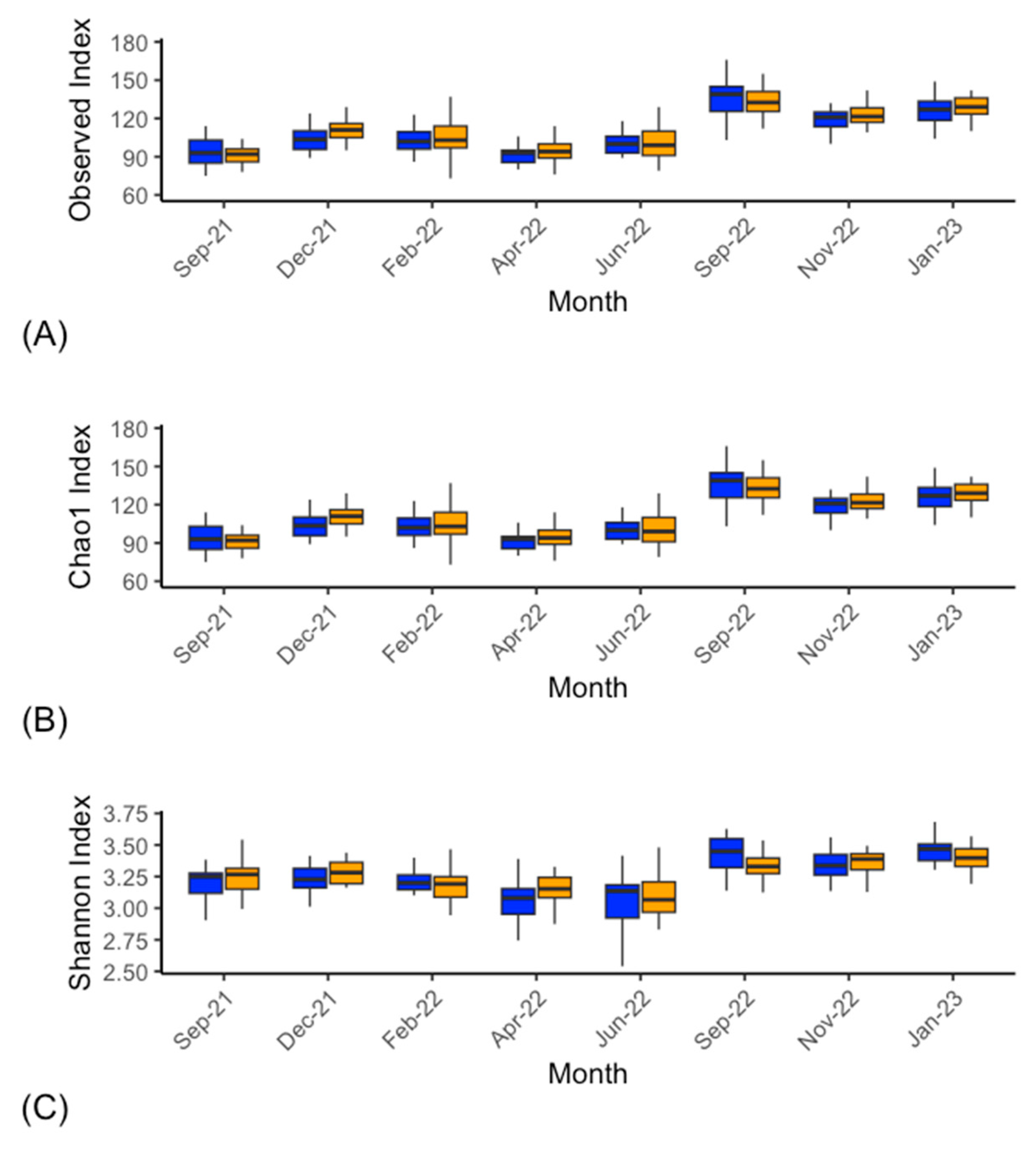

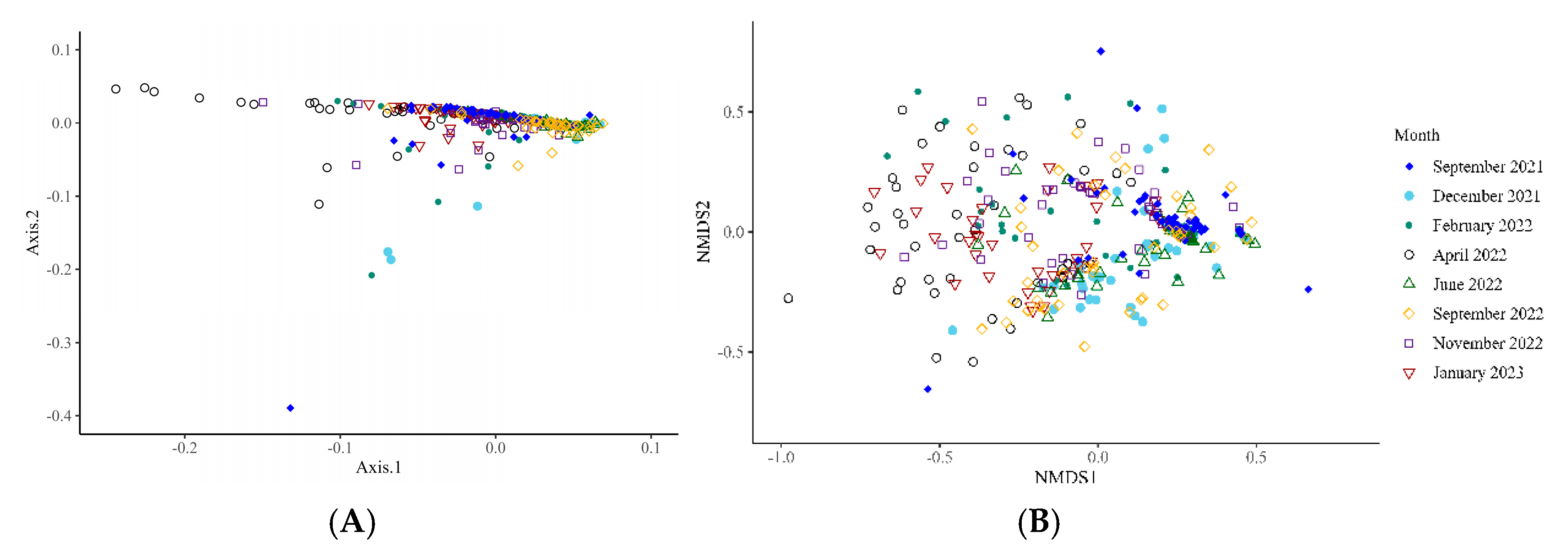

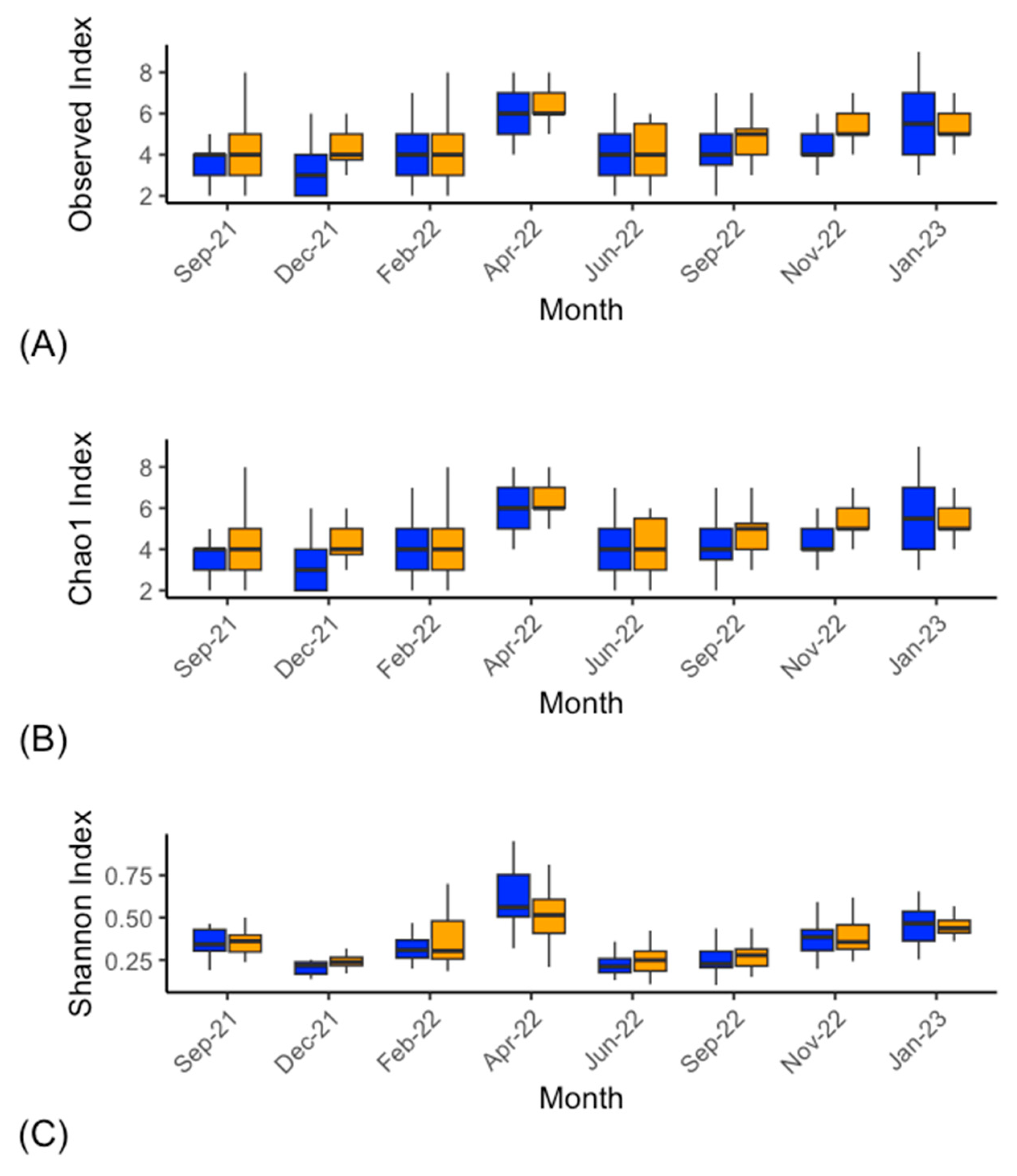

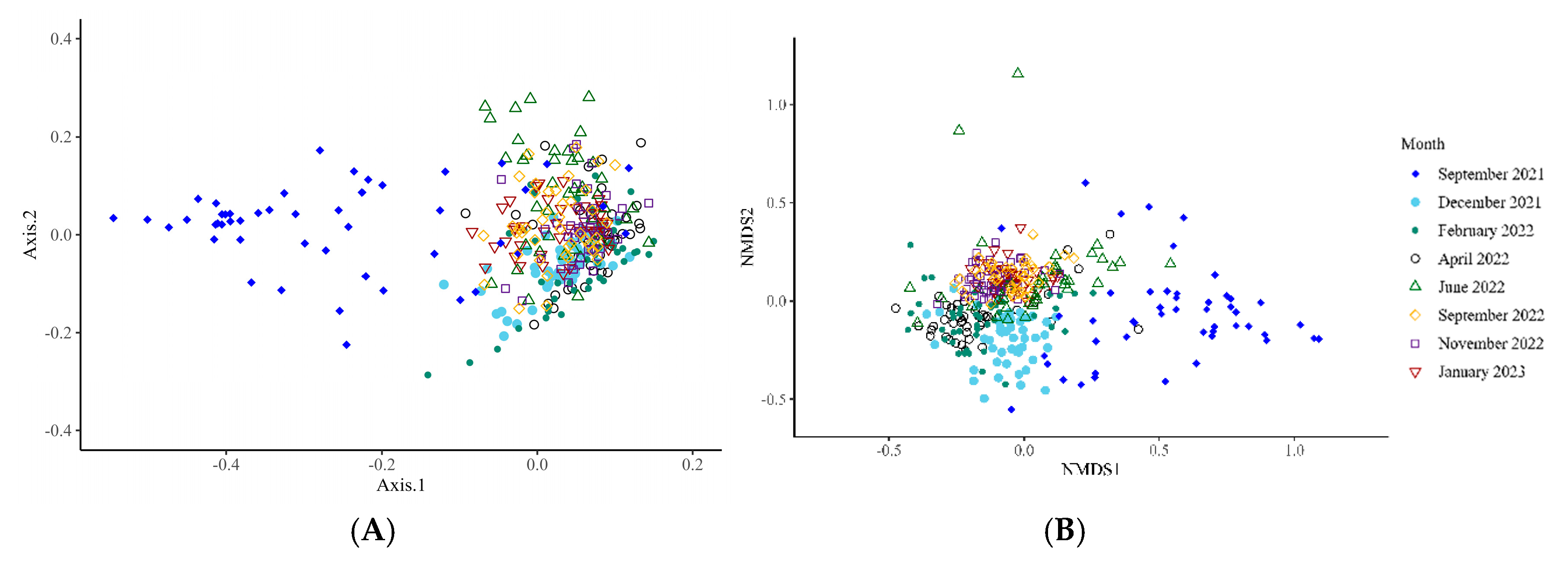

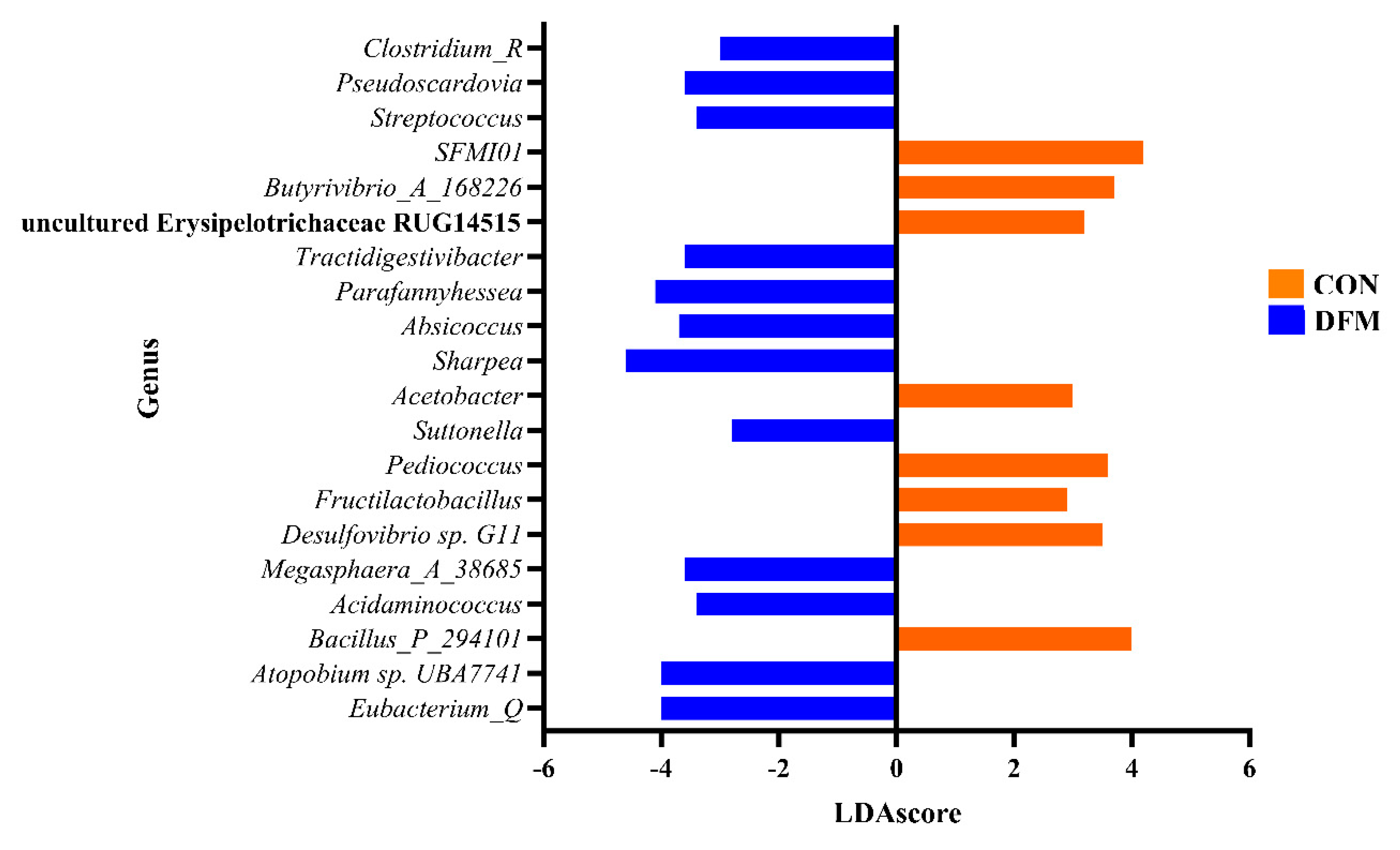

The current study examined the effects of lactobacilli-based direct-fed microbial (DFM) supplementation on the microbiota composition and diversity in ruminal fluid samples collected from dairy cows. Over 18 months (September 2021 through January 2023), the rumen bacterial and archaeal communities of fifty cows, supplemented with the DFM (DFM; n = 25) or serving as un-supplemented controls (CON; n = 25), were examined using 16S rRNA gene amplification and sequence analysis of DNA extracted from ruminal samples. Microbial diversity was assessed through alpha- and beta-diversity metrics (p<0.05). Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) analysis was performed to identify taxa driving the changes seen in the microbiota between experimental groups and temporally within each group (p<0.05). Bacillota and Bacteroidota were the major bacterial phyla, while Methanobacteriaceae was the predominant archaeal family. Bacterial genera such as Eubacterium_Q, Atopobium sp. UBA7741, and Sharpea were significantly more abundant in the DFM group, while Bacillus_P_294101 and SFMI01 had higher abundance in the CON group. The results also indicated significant temporal variations in ruminal microbial diversity, with specific taxa exhibiting different abundances between the DFM and CON groups. This study provides insights into how DFM feed additives can modulate the ruminal microbiota in dairy cows, revealing specific microbial shifts in response to supplementation.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Location, Study Herd, and Study Animals

Sample Collection

Quality Control and Sequence Read Counts

DNA Extraction and PCR

Statistical and Bioinformatic Analysis

3. Results

Bacterial Microbiota

Archaeal Microbiota

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Samtiya, M.; Soni, K.; Chawla, S.; Poonia, A.; Sehgal, S.; Dhewa, T. Key anti-nutrients of millet and their reduction strategies: An overview. Acta Scientific NUTRITIONAL HEALTH (ISSN: 2582-1423) 2021, 5.

- Anil Kumar, P.; Salem, A.Z.; Kumar, S.; Dagar, S.S.; W Griffith, G.; Puniya, M.; R Ravella, S.; Kumar, N.; Dhewa, T.; Kumar, R. Role of live microbial feed supplements with reference to anaerobic fungi in ruminant productivity: A review. 2015.

- Bickhart, D.; Weimer, P. Symposium review: Host–rumen microbe interactions may be leveraged to improve the productivity of dairy cows. Journal of dairy science 2018, 101, 7680-7689. [CrossRef]

- Deusch, S.; Camarinha-Silva, A.; Conrad, J.; Beifuss, U.; Rodehutscord, M.; Seifert, J. A structural and functional elucidation of the rumen microbiome influenced by various diets and microenvironments. Frontiers in microbiology 2017, 8, 1605. [CrossRef]

- Elghandour, M.M.; Salem, A.Z.; Castañeda, J.S.M.; Camacho, L.M.; Kholif, A.E.; Chagoyán, J.C.V. Direct-fed microbes: A tool for improving the utilization of low quality roughages in ruminants. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2015, 14, 526-533. [CrossRef]

- Chaucheyras-Durand, F.; Durand, H. Probiotics in animal nutrition and health. Beneficial microbes 2010, 1, 3-9. [CrossRef]

- Zeineldin, M.; Barakat, R.; Elolimy, A.; Salem, A.Z.; Elghandour, M.M.; Monroy, J.C. Synergetic action between the rumen microbiota and bovine health. Microbial pathogenesis 2018, 124, 106-115. [CrossRef]

- Ogunade, I.M.; McCoun, M.; Idowu, M.D.; Peters, S.O. Comparative effects of two multispecies direct-fed microbial products on energy status, nutrient digestibility, and ruminal fermentation, bacterial community, and metabolome of beef steers. Journal of Animal Science 2020, 98, skaa201. [CrossRef]

- Rinninella, E.; Raoul, P.; Cintoni, M.; Franceschi, F.; Miggiano, G.A.D.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M.C. What is the healthy gut microbiota composition? A changing ecosystem across age, environment, diet, and diseases. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 14.

- Flint, H.J.; Duncan, S.H.; Scott, K.P.; Louis, P. Links between diet, gut microbiota composition and gut metabolism. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 2015, 74, 13-22. [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.R.; Myhill, L.J.; Stolzenbach, S.; Nejsum, P.; Mejer, H.; Nielsen, D.S.; Thamsborg, S.M. Emerging interactions between diet, gastrointestinal helminth infection, and the gut microbiota in livestock. BMC Veterinary Research 2021, 17, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Ban, Y.; Guan, L.L. Implication and challenges of direct-fed microbial supplementation to improve ruminant production and health. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology 2021, 12, 109. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, M.B. In-Vivo Assessment of a Direct-Fed Microbial on Lactation Performances, Blood Biomarkers, Ruminal Fermentation and Microbial Abundance in Transition to Mid-Lactation Holstein Cows; South Dakota State University: 2023.

- Ramirez-Garzon, O.; Al-Alawneh, J.I.; Barber, D.; Liu, H.; Soust, M. The Effect of a Direct Fed Microbial on Liveweight and Milk Production in Dairy Cattle. Animals 2024, 14, 1092. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Tomita, J.; Nishioka, K.; Hisada, T.; Nishijima, M. Development of a prokaryotic universal primer for simultaneous analysis of Bacteria and Archaea using next-generation sequencing. PloS one 2014, 9, e105592. [CrossRef]

- Gohl, D.M.; Vangay, P.; Garbe, J.; MacLean, A.; Hauge, A.; Becker, A.; Gould, T.J.; Clayton, J.B.; Johnson, T.J.; Hunter, R. Systematic improvement of amplicon marker gene methods for increased accuracy in microbiome studies. Nature biotechnology 2016, 34, 942-949. [CrossRef]

- Bahram, M.; Anslan, S.; Hildebrand, F.; Bork, P.; Tedersoo, L. Newly designed 16S rRNA metabarcoding primers amplify diverse and novel archaeal taxa from the environment. Environmental microbiology reports 2019, 11, 487-494. [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nature methods 2016, 13, 581-583. [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nature biotechnology 2019, 37, 852-857. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, D.; Jiang, Y.; Balaban, M.; Cantrell, K.; Zhu, Q.; Gonzalez, A.; Morton, J.T.; Nicolaou, G.; Parks, D.H.; Karst, S.M. Greengenes2 unifies microbial data in a single reference tree. Nature biotechnology 2023, 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Dhariwal, R.; Henriquez, M.A.; Hiebert, C.; McCartney, C.A.; Randhawa, H.S. Mapping of major Fusarium head blight resistance from Canadian wheat cv. AAC Tenacious. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 4497. [CrossRef]

- Chao, A. Nonparametric estimation of the number of classes in a population. Scandinavian Journal of statistics 1984, 265-270.

- Simpson, G.G.; Simpson, L. The meaning of evolution: a study of the history of life and of its significance for man; Yale University Press: 1949; Vol. 23.

- Weaver, W. The mathematical theory of communication; University of Illinois Press: 1963.

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: a review and recent developments. Philosophical transactions of the royal society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2016, 374, 20150202. [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, G.B. An introduction to nonmetric multidimensional scaling. American Journal of Political Science 1975, 343-390. [CrossRef]

- Bates, D. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using S4 classes. R package version 0.999375-33. http://CRAN. R-project. org/package= lme4 2010.

- Bates, D.M. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using S4 classes. (No Title) 2007.

- Team, R.C. RA language and environment for statistical computing, R Foundation for Statistical. Computing 2020.

- Dill-McFarland, K.A.; Weimer, P.J.; Pauli, J.N.; Peery, M.Z.; Suen, G. Diet specialization selects for an unusual and simplified gut microbiota in two-and three-toed sloths. Environmental Microbiology 2016, 18, 1391-1402. [CrossRef]

- Flint, H.J.; Duncan, S. Bacteroides and prevotella. In Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology: Second Edition, Elsevier Inc.: 2014; pp. 203-208.

- Henderson, G.; Cox, F.; Ganesh, S.; Jonker, A.; Young, W.; Janssen, P.H. Rumen microbial community composition varies with diet and host, but a core microbiome is found across a wide geographical range. Scientific reports 2015, 5, 14567. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhan, S.; Liu, X.; Lin, Q.; Jiang, J.; Li, X. Divergence of Fecal Microbiota and Their Associations With Host Phylogeny in Cervinae. Frontiers in Microbiology 2018, 9, doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.01823. [CrossRef]

- Shade, A.; Gregory Caporaso, J.; Handelsman, J.; Knight, R.; Fierer, N. A meta-analysis of changes in bacterial and archaeal communities with time. The ISME journal 2013, 7, 1493-1506. [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, K.E. The Effect of Supplementing Native Rumen Microbes on Milk Production of Dairy Cattle; Michigan State University: 2022.

- O'Hara, E.; Neves, A.L.; Song, Y.; Guan, L.L. The role of the gut microbiome in cattle production and health: driver or passenger? Annual review of animal biosciences 2020, 8, 199-220. [CrossRef]

- Bartenslager, A. Investigating microbiomes and developing direct-fed microbials to improve cattle health. 2020.

- Dankwa, A.; Humagain, U.; Ishaq, S.; Yeoman, C.; Clark, S.; Beitz, D.; Testroet, E. Bacterial communities in the rumen and feces of lactating Holstein dairy cows are not affected when fed reduced-fat dried distillers’ grains with solubles. Animal 2021, 15, 100281.

- Alawneh, J.I.; Ramay, H.; Olchowy, T.; Allavena, R.; Soust, M.; Jassim, R.A. Effect of a Lactobacilli-Based Direct-Fed Microbial Product on Gut Microbiota and Gastrointestinal Morphological Changes. Animals 2024, 14, 693. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tsai, T.; Wei, X.; Zuo, B.; Davis, E.; Rehberger, T.; Hernandez, S.; Jochems, E.J.; Maxwell, C.V.; Zhao, J. Effect of Lactylate and Bacillus subtilis on growth performance, peripheral blood cell profile, and gut microbiota of nursery pigs. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 803. [CrossRef]

- Pitta, D.; Pinchak, W.; Dowd, S.; Dorton, K.; Yoon, I.; Min, B.; Fulford, J.; Wickersham, T.; Malinowski, D. Longitudinal shifts in bacterial diversity and fermentation pattern in the rumen of steers grazing wheat pasture. Anaerobe 2014, 30, 11-17. [CrossRef]

- Kalebich, C.C.; Cardoso, F.C. Effects of direct-fed microbials on feed intake, milk yield, milk composition, feed conversion, and health condition of dairy cows. In Nutrients in Dairy and their Implications on Health and Disease, Elsevier: 2017; pp. 111-121.

- Davies, S.J.; Esposito, G.; Villot, C.; Chevaux, E.; Raffrenato, E. An Evaluation of Nutritional and Therapeutic Factors Affecting Pre-Weaned Calf Health and Welfare, and Direct-Fed Microbials as a Potential Alternative for Promoting Performance—A Review. Dairy 2022, 3, 648-667. [CrossRef]

- Oyebade, A.O. Effects of Bacterial Direct-Fed Microbial Supplementation on Rumen Fermentation, Rumen and Plasma Metabolome, and Performance of Lactating Dairy Cows. University of Florida, 2021.

- Zeng, H.; Guo, C.; Sun, D.; Seddik, H.-e.; Mao, S. The ruminal microbiome and metabolome alterations associated with diet-induced milk fat depression in dairy cows. Metabolites 2019, 9, 154. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Ji, S.; Yan, H.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Z.; Li, S. The day-to-day stability of the ruminal and fecal microbiota in lactating dairy cows. Microbiologyopen 2020, 9, e990. [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.B.; Rychlik, J.L. Factors that alter rumen microbial ecology. Science 2001, 292, 1119-1122. [CrossRef]

- Janssen, P.H.; Kirs, M. Structure of the archaeal community of the rumen. Applied and environmental microbiology 2008, 74, 3619-3625. [CrossRef]

- Malik, P.K.; Trivedi, S.; Kolte, A.P.; Sejian, V.; Bhatta, R.; Rahman, H. Diversity of rumen microbiota using metagenome sequencing and methane yield in Indian sheep fed on straw and concentrate diet. Saudi J Biol Sci 2022, 29, 103345, doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2022.103345. [CrossRef]

- Hook, S.E.; Wright, A.-D.G.; McBride, B.W. Methanogens: methane producers of the rumen and mitigation strategies. Archaea 2010, 2010, 945785. [CrossRef]

- Morgavi, D.; Forano, E.; Martin, C.; Newbold, C.J. Microbial ecosystem and methanogenesis in ruminants. animal 2010, 4, 1024-1036. [CrossRef]

- Noel, S.J.; Olijhoek, D.W.; Mclean, F.; Løvendahl, P.; Lund, P.; Højberg, O. Rumen and fecal microbial community structure of Holstein and Jersey dairy cows as affected by breed, diet, and residual feed intake. Animals 2019, 9, 498. [CrossRef]

- Kibegwa, F.M.; Bett, R.C.; Gachuiri, C.K.; Machuka, E.; Stomeo, F.; Mujibi, F.D. Diversity and functional analysis of rumen and fecal microbial communities associated.

| BacF | 16S | GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT |

| BacR | 16S | TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG |

| ArchF | 16S | TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGYGCASCAGKCGMGAAW |

| ArchR | 16S | GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGHGCYTTCGCCACHGGTRG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).