Submitted:

29 November 2024

Posted:

02 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Compliance with Ethical Standards

2.2. Animal Husbandry, Housing and Diet Consideration

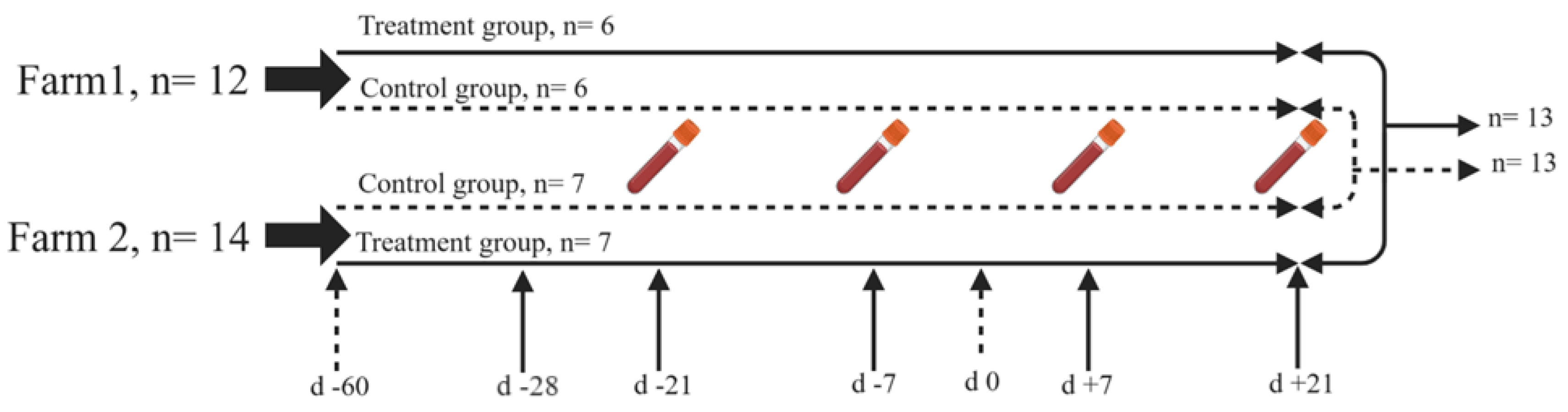

2.3. Experimental Design and Supplementation

2.4. Blood Sampling and Blood Parameter Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

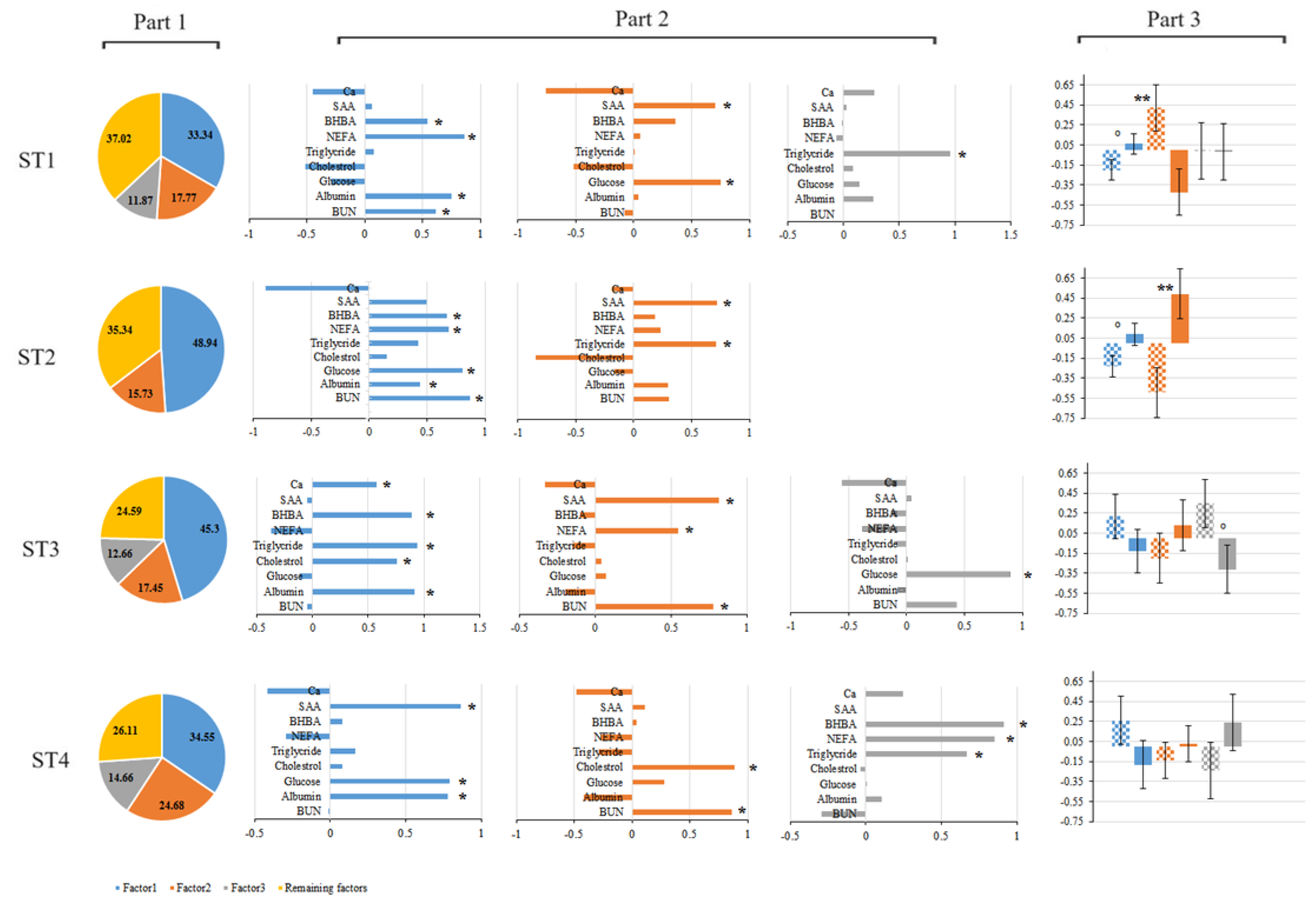

3.1. First Sampling Time (21 ± 2 d Before Calving)

3.2. Second Sampling Time (7± 2 d Before Calving)

3.3. Third Sampling Time (7 ± 2 d After Calving)

3.4. Fourth Sampling Time (21 ± 2 d After Calving)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lopreiato, V.; Mezzetti, M.; Cattaneo, L.; Ferronato, G.; Minuti, A.; Trevisi, E. Role of Nutraceuticals during the Transition Period of Dairy Cows: A Review. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 11, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezzetti, M.; Cattaneo, L.; Passamonti, M.M.; Lopreiato, V.; Minuti, A.; Trevisi, E. The Transition Period Updated: A Review of the New Insights into the Adaptation of Dairy Cows to the New Lactation. Dairy. 2021, 2, 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caixeta, L.S.; Omontese, B.O. Monitoring and Improving the Metabolic Health of Dairy Cows during the Transition Period. Animals. 2021, 11, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascottini, O.B.; Leroy, J.L.M.R.; Opsomer, G. Metabolic Stress in the Transition Period of Dairy Cows: Focusing on the Prepartum Period. Animals. 2020, 10, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronfeld, D.S. Major Metabolic Determinants of Milk Volume, Mammary Efficiency, and Spontaneous Ketosis in Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horst, E.A.; Kvidera, S.K.; Baumgard, L.H. Invited Review: The Influence of Immune Activation on Transition Cow Health and Performance—A Critical Evaluation of Traditional Dogmas. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 8380–8410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufarelli, V.; et al. The Most Important Metabolic Diseases in Dairy Cattle during the Transition Period. Animals. 2024, 14, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.A.; Pourjafar, M.; Hajimohammadi, A.; Valizadeh, R.; Naserian, A.A.; Laven, R.; Mueller, K.R. Effects of Dietary Supplementation of Bentonite and Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cell Wall on Acute-Phase Protein and Liver Function in High-Producing Dairy Cows during Transition Period. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2019, 51, 1225–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, A.; Hajimohammadi, A.; Badiei, K.; Pourjafar, M.; Naserian, A.A.; Razavi, S.A. Effect of Dietary Supplementation of Bentonite and Yeast Cell Wall on Serum Endotoxin, Inflammatory Parameters, Serum and Milk Aflatoxin in High-Producing Dairy Cows during the Transition Period. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2020, 29, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liong, M.T. Probiotics: A Critical Review of Their Potential Role as Antihypertensives, Immune Modulators, Hypocholesterolemics, and Perimenopausal Treatments. Nutr. Rev. 2007, 65, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, A.; Razavi, S.A.; Babazadeh, D.; Laven, R.; Saeed, M. Roles of Probiotics in Farm Animals: A Review. Farm Anim. Health Nutr. 2022, 1, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitta, D.W.; Kumar, S.; Vecchiarelli, B.; Shirley, D.J.; Bittinger, K.; Baker, L.D.; Thomsen, N. Temporal Dynamics in the Ruminal Microbiome of Dairy Cows during the Transition Period. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 92, 4014–4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaza-Diaz, J.; Ruiz-Ojeda, F.J.; Gil-Campos, M.; Gil, A. Mechanisms of Action of Probiotics. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, S49–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiocco, D.; Longo, A.; Arena, M.P.; Russo, P.; Spano, G.; Capozzi, V. How Probiotics Face Food Stress: They Get by with a Little Help. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 1552–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, T.H.; Elsayed, F.A.; Ahmed, M.A.; Elkholany, M.A. Effect of Using Some Feed Additives (TW-Probiotics) in Dairy Cow Rations on Production and Reproductive Performance. Egypt. J. Anim. Prod. 2014, 51, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi, S.; Hajimohammadi, A.; Mirzaei, A.; Nazifi, S. Effects of Probiotic and Yeast Extract Supplementation on Oxidative Stress, Inflammatory Response, and Growth in Weaning Saanen Kids. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2023, 55, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawley, D.N.; Maxwell, A.E. Factor Analysis as a Statistical Method. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. D Stat. 1962, 12, 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, A.; Berchtold, W. Statistische Methoden III. UTB 1189, Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel. 1982.

- SAS Institute. SAS Certified Specialist Prep Guide: Base Programming Using SAS 9.4. SAS Institute. 2019.

- Kaiser, H.F. An Index of Factorial Simplicity. Psychometrika. 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrigar, L.R.; Wegener, D.T. Understanding Statistics: Exploratory Factor Analysis; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, P. An Easy Guide to Factor Analysis; Routledge: New York, NY, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, M.C. A Review of Exploratory Factor Analysis Decisions and Overview of Current Practices: What We Are Doing and How Can We Improve? Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2016, 32, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobias, S.; Carlson, J.E. Brief Report: Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity and Chance Findings in Factor Analysis. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1969, 4, 375–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoski, K.W.; Jurs, S. An Objective Counterpart to the Visual Scree Test for Factor Analysis: The Standard Error Scree. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1996, 56, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. The Varimax Criterion for Analytic Rotation in Factor Analysis. Psychometrika. 1958, 23, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J. Best Practices in Exploratory Factor Analysis: Four Recommendations for Getting the Most from Your Analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2005, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Putman, A.K.; Brown, J.L.; Gandy, J.C.; Wisnieski, L.; Sordillo, L.M. Changes in Biomarkers of Nutrient Metabolism, Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress in Dairy Cows during the Transition into the Early Dry Period. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 9350–9359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushibiki, S.; Hodate, K.; Shingu, H.; Obara, Y.; Touno, E.; Shinoda, M.; Yokomizo, Y. Metabolic and Lactational Responses during Recombinant Bovine Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Treatment in Lactating Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2003, 86, 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friggens, N.C.; Andersen, J.B.; Larsen, T.; Aaes, O.; Dewhurst, R.J. Priming the Dairy Cow for Lactation: A Review of Dry Cow Feeding Strategies. Anim. Res. 2004, 53, 453–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascottini, O.B.; Leroy, J.L.; Opsomer, G. Metabolic Stress in the Transition Period of Dairy Cows: Focusing on the Prepartum Period. Animals. 2020, 10, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattell, R.B. The Scree Test for the Number of Factors. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1966, 1, 245–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Liu, G.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, L.; Shi, X.; Li, X. BHBA Influences Bovine Hepatic Lipid Metabolism via AMPK Signaling Pathway. J. Cell. Biochem. 2015, 116, 1070–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puppel, K.; Kuczyńska, B. Metabolic Profiles of Cow's Blood: A Review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 4321–4328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisi, E.; Zecconi, A.; Bertoni, G.; Piccinini, R. Blood and Milk Immune and Inflammatory Profiles in Periparturient Dairy Cows Showing a Different Liver Activity Index. J. Dairy Res. 2010, 77, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastani, R.R.; Lobos, N.E.; Aguerre, M.J.; Grummer, R.R.; Wattiaux, M.A. Relationships between Blood Urea Nitrogen and Energy Balance or Measures of Tissue Mobilization in Holstein Cows during the Periparturient Period. Prof. Anim. Sci. 2006, 22, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumprechtová, D.; Illek, J.; Julien, C.; Homolka, P.; Jančík, F.; Auclair, E. Effect of Live Yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) Supplementation on Rumen Fermentation and Metabolic Profile of Dairy Cows in Early Lactation. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2019, 103, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdick Sanchez, N.C.; Broadway, P.R.; Carroll, J.A. Influence of Yeast Products on Modulating Metabolism and Immunity in Cattle and Swine. Animals. 2021, 11, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razavi, S.A.; Pourjafar, M.; Hajimohammadi, A.; Valizadeh, R.; Naserian, A.A.; Laven, R.; Mueller, K.R. Effects of Dietary Supplementation of Bentonite and Yeast Cell Wall on Serum Blood Urea Nitrogen, Triglyceride, Alkaline Phosphatase, and Calcium in High-Producing Dairy Cattle during the Transition Period. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2018, 28, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, E.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S. Effects of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Culture on Ruminal Fermentation, Blood Metabolism, and Performance of High-Yield Dairy Cows. Animals. 2021, 11, 2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goff, J.P.; Horst, R.L. Physiological Changes at Parturition and Their Relationship to Metabolic Disorders. J. Dairy Sci. 1997, 80, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A.W.; Bauman, D.E. Adaptations of Glucose Metabolism during Pregnancy and Lactation. J. Mamm. Gland Biol. Neoplasia 1997, 2, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlar, C.M.; Whitehead, A.S. Serum Amyloid A, the Major Vertebrate Acute-Phase Reactant. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999, 265, 501–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, G.A.; Strachan, A.F.; Westhuyzen, D.R.; Hoppe, H.C.; Jeenah, M.S.; DeBeer, F.C. Serum Amyloid A Containing Human High-Density Lipoprotein 3. J. Biol. Chem. 1986, 261, 9644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shephard, E.G.; DeBeer, F.C.; DeBeer, M.C.; Jeenah, M.S.; Coetzee, G.A.; Van der Westhuyzen, D.R. Neutrophil Association and Degradation of Normal and Acute-Phase High-Density Lipoprotein-3. Biochem. J. 1987, 248, 919–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badolato, R.; Wang, J.M.; Murphy, W.J.; Lloyd, A.R.; Michiel, D.F.; Bausserman, L.L. Serum Amyloid A Is a Chemoattractant—Induction of Migration, Adhesion, and Tissue Infiltration of Monocytes and Polymorphonuclear Leukocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1994, 180, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaworski, E.M.; Shriver-Munsch, C.M.; Fadden, N.A.; Sanchez, W.K.; Yoon, I.; Bobe, G. Effects of Feeding Various Dosages of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Fermentation Product in Transition Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 3081–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivinski, S.E.; Meier, K.E.; Mamedova, L.K.; Saylor, B.A.; Shaffer, J.E.; Sauls-Hiesterman, J.A.; Bradford, B.J. Effect of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Fermentation Product on Oxidative Status, Inflammation, and Immune Response in Transition Dairy Cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 8850–8865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, C.A. Functional Components of the Cell Wall of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Applications for Yeast Glucan and Mannan. 2004.

- Kumprechtová, D.; Illek, J.; Julien, C.; Homolka, P.; Jančík, F.; Auclair, E. Effect of Live Yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) Supplementation on Rumen Fermentation and Metabolic Profile of Dairy Cows in Early Lactation. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2019, 103, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdick Sanchez, N.C.; Broadway, P.R.; Carroll, J.A. Influence of Yeast Products on Modulating Metabolism and Immunity in Cattle and Swine. Animals. 2021, 11, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, E.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S. Effects of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Culture on Ruminal Fermentation, Blood Metabolism, and Performance of High-Yield Dairy Cows. Animals. 2021, 11, 2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erasmus, L.J.; Robinson, P.H.; Ahmadi, A.; Hinders, R.; Garrett, J.E. Influence of Prepartum and Postpartum Supplementation of a Yeast Culture and Monensin, or Both, on Ruminal Fermentation and Performance of Multiparous Dairy Cows. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2005, 122, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Webster, T.; Hoover, W.H.; Holt, M.; Nocek, J.E. Influence of Yeast Culture on Ruminal Microbial Metabolism in Continuous Culture. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 85, 2009–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, I.K.; Stern, M.D. Effects of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Aspergillus oryzae Cultures on Ruminal Fermentation in Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1996, 79, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.; Reeves, S.; Robinson, L.E. A Dried Yeast Fermentate Prevents and Reduces Inflammation in Two Separate Experimental Immune Models. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2012, 973041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, G.S.; Hart, A.N.; Schauss, A.G. An Anti-Inflammatory Immunogen from Yeast Culture Induces Activation and Alters Chemokine Receptor Expression on Human Natural Killer Cells and B Lymphocytes In Vitro. Nutr. Res. 2007, 27, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, G.S.; Patterson, K.M.; Barnes, J.; Schauss, A.G.; Beaman, R.; Reeves, S.G.; Robinson, L.E. A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Pilot Study: Consumption of a High Metabolite Immunogen from Yeast Culture Has Beneficial Effects on Erythrocyte Health and Mucosal Immune Protection in Healthy Subjects. Open Nutr. J. 2008, 2, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, G.S.; Patterson, K.M.; Yoon, I. Nutritional Yeast Culture Has Specific Anti-Microbial Properties without Affecting Healthy Flora. Preliminary Results. J. Anim. Feed Sci. 2008, 17, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, G.S.; Patterson, K.M.; Yoon, I. Yeast Culture Has Anti-Inflammatory Effects and Specifically Activates NK Cells. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2008, 31, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ametaj, B.N.; Hosseini, A.; Odhiambo, J.F.; Iqbal, S.; Sharma, S.; Deng, Q.; Lam, T.H.; Farooq, U.; Zebeli, Q.; Dunn, S.M. Application of Acute Phase Proteins for Monitoring Inflammatory States in Cattle. In Acute Phase Proteins as Early Non-Specific Biomarkers of Human and Veterinary Diseases; Veas, F., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011; Chapter 13. Accessed Oct. 24, 2013. http://www.intechopen.com/articles/show/title/application-of-acute-phase-proteins-for-monitoring-inflammatory-states-in-cattle. [Google Scholar]

- Sabedra, D.; Ramsing, E.M.; Shriver-Munsch, C.M.; Males, J.R.; Sanchez, W.K.; Yoon, I.; Bobe, G. Haptoglobin Is a Potential Early Indicator of Postpartal Diseases. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95 (Suppl. 2), 513, (Abstr.). [Google Scholar]

- Shainkin-Kestenbaum, R.; Berlyne, G.; Zimlichman, S.; Sorin, H.R.; Nyska, M.; Danon, A. Acute Phase Protein, Serum Amyloid A, Inhibits IL-1- and TNF-Induced Fever and Hypothalamic PGE2 in Mice. Scand. J. Immunol. 1991, 34, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arredouani, M.S.; Kasran, A.; Vanoirbeek, J.A.; Berger, F.G.; Baumann, H.; Ceuppens, J.L. Haptoglobin Dampens Endotoxin-Induced Inflammatory Effects Both In Vitro and In Vivo. Immunology. 2005, 114, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farney, J.K.; Mamedova, L.K.; Coetzee, J.F.; KuKanich, B.; Sordillo, L.M.; Stoakes, S.K.; Minton, J.E.; Hollis, L.C.; Bradford, B.J. Anti-Inflammatory Salicylate Treatment Alters the Metabolic Adaptations to Lactation in Dairy Cattle. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2013, 305, R110–R117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, C.R.; Erb, H.N.; Sniffen, C.J.; Smith, R.D.; Powers, P.A.; Smith, M.C.; White, M.E.; Hillman, R.B.; Pearson, E.J. Association of Parturient Hypocalcemia with Eight Periparturient Disorders in Holstein Cows. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1983, 183, 559–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlin, W.G.; Middleton, J.R.; Spain, J.N.; Johnson, G.C.; Ellersieck, M.R.; Pithua, P. Subclinical Hypocalcemia, Plasma Biochemical Parameters, Lipid Metabolism, Postpartum Disease, and Fertility in Postparturient Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 7001–7013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cifuentes, M.; Rojas, C.V. Antilipolytic Effect of Calcium-Sensing Receptor in Human Adipocytes. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2008, 319, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsing, E.M.; Davidson, J.A.; French, P.D.; Yoon, I.; Keller, M.; Peters-Fleckenstein, H. Effect of Yeast Culture on Peripartum Intake and Milk Production of Primiparous and Multiparous Holstein Cows. Prof. Anim. Sci. 2009, 25, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, P.H.; Garrett, J.E. Effect of Yeast Culture (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) on Adaptation of Cows to Postpartum Diets and on Lactational Performance. J. Anim. Sci. 1999, 77, 988–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, H.M.; Drackley, J.K.; McCoy, G.C.; Hutjens, M.F.; Garrett, J.E. Effects of Yeast Culture (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) on Prepartum Intake and Postpartum Intake and Milk Production of Jersey Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2000, 83, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóthová, C.S.; Nagy, O.; Seidel, H.; Konvičná, J.; Farkašová, Z.; Kováč, G. Acute Phase Proteins and Variables of Protein Metabolism in Dairy Cows during the Pre-and Postpartal Period. Acta Vet. Brno. 2008, 77, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoblock, C.E.; Shi, W.; Yoon, I.; Oba, M. Effects of Supplementing a Saccharomyces cerevisiae Fermentation Product during the Periparturient Period on the Immune Response of Dairy Cows Fed Fresh Diets Differing in Starch Content. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 6199–6209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.G.; Waldern, D.E. Repeatabilities of Serum Constituents in Holstein–Friesians Affected by Feeding, Age, Lactation, and Pregnancy. J. Dairy Sci. 1981, 64, 822–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifi, H.A.; Gorji-Dooz, M.; Mohri, M.; Dalir-Naghadeh, B.; Farzaneh, N. Variations of Energy-Related Biochemical Metabolites during Transition Period in Dairy Cows. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2007, 16, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauchart, D. Lipid Absorption and Transport in Ruminants. J. Dairy Sci. 1993, 76, 3864–3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, G.A.; Sordillo, L.M. Lipid Mobilization and Inflammatory Responses during the Transition Period of Dairy Cows. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2011, 34, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Deeb, W.M.; El-Bahr, S.M. Biomarkers of Ketosis in Dairy Cows at Postparturient Period: Acute Phase Proteins and Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines. Vet. Arhiv. 2017, 87, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoblock, C.E.; Shi, W.; Yoon, I.; Oba, M. Effects of Supplementing a Saccharomyces cerevisiae Fermentation Product during the Periparturient Period on the Immune Response of Dairy Cows Fed Fresh Diets Differing in Starch Content. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 6199–6209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PCs1 | ST1 | ST2 | ST3 | ST4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalue | Proportion | Eigenvalue | Proportion | Eigenvalue | Proportion | Eigenvalue | Proportion | |

| 1 | 3.00 | 33.34% | 4.40 | 48.94% | 4.08 | 45.30% | 3.11 | 34.55% |

| 2 | 1.59 | 17.77% | 1.42 | 15.73% | 1.57 | 17.45% | 2.22 | 24.68% |

| 3 | 1.067 | 11.87% | 1.14 | 12.66% | 1.32 | 14.66% | ||

| CPV2 | 62.98% | 64.66% | 75.41% | 73.88% | ||||

| ST1 | ST2 | ST3 | ST4 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | F 1 | F 2 | F 3 | F 1 | F 2 | F 1 | F 2 | F3 | F 1 | F 2 | F 3 | |||||||

| BUN2 | 0.61 | -0.08 | -0.01 | 0.87 | 0.29 | -0.04 | 0.77 | 0.43 | -0.01 | 0.86 | -0.29 | |||||||

| Albumin | 0.75 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0.29 | 0.91 | -0.19 | -0.08 | 0.78 | 0.41 | 0.11 | |||||||

| Glucose | -0.29 | 0.75 | 0.14 | 0.80 | -0.16 | -0.11 | 0.07 | 0.89 | 0.79 | 0.28 | 0.01 | |||||||

| Cholesterol | -0.51 | -0.51 | 0.08 | 0.15 | -0.84 | 0.75 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.89 | -0.03 | |||||||

| Triglyceride | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.95 | 0.42 | 0.70 | 0.94 | -0.14 | -0.08 | 0.16 | -0.28 | 0.66 | |||||||

| NEFA3 | 0.87 | 0.06 | -0.06 | 0.68 | 0.23 | -0.36 | 0.54 | -0.38 | -0.29 | -0.27 | 0.85 | |||||||

| BHBA4 | 0.54 | 0.36 | -0.01 | 0.67 | 0.18 | 0.88 | -0.09 | -0.13 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.91 | |||||||

| SAA5 | 0.06 | 0.70 | 0.03 | 0.49 | 0.72 | -0.04 | 0.81 | 0.03 | 0.86 | 0.10 | -0.01 | |||||||

| Ca6 | -0.45 | -0.76 | 0.27 | -0.89 | -0.18 | 0.57 | -0.32 | -0.55 | -0.41 | -0.47 | 0.24 | |||||||

| Factors | ST2 1 | ST2 | ST3 | ST4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F 1 | NEFA3, Albumin, BUN4, BHBA5 | BUN, Glucose, NEFA, BHBA, Albumin | Triglyceride, Albumin, BHBA, Cholesterol, Ca7 | SAA, Glucose, Albumin |

| F 2 | Glucose, SAA6 | SAA, NEFA | SAA, BUN, NEFA | Cholesterol, BUN |

| F 3 | Triglyceride | . | Glucose | BHBA, NEFA, Triglyceride |

| Treatments | Farms | T×F9 | ||||||||||

| S. Cerevisiae | Control | P value | Farm 1 | Farm 2 | P value | P value | ||||||

| ST2 1 | ||||||||||||

| F1 (NEFA3, Alb4, BUN5, BHBA6) | -0.20 ± 0.10 | 0.06± 0.10 | 0.08 | -0.97 ± 0.11 | 0.83 ± 0.10 | < 0.05 | 0.17 | |||||

| F2 (Glucose, SAA7) | 0.42 ± 0.23 | -0.42 ± 0.23 | 0.01 | 0.004 ±0.23 | -0.003 ± 0.22 | 0.98 | 0.01 | |||||

| F3 (Triglyceride) | -0.009 ± 0.28 | -0.02 ± 0.28 | 0.97 | -0.20 ± 0.29 | 0.17 ± 0.27 | 0.37 | 0.57 | |||||

| ST2 | ||||||||||||

| F1 (BUN, Glucose, NEFA, BHBA, Alb) | -0.23 ± 0.11 | 0.09 ± 0.11 | 0.06 | -0.95 ± 0.12 | 0.81 ± 0.11 | < 0.05 | 0.64 | |||||

| F2 (SAA, Triglyceride) | -0.49 ± 0.25 | 0.49 ± 0.25 | 0.01 | -0.05 ± 0.26 | 0.04 ± 0.24 | 0.79 | 0.54 | |||||

| ST3 | ||||||||||||

| F1 (TAG, Alb, BHBA, Chol, Ca8) | 0.22 ± 0.22 | -0.13 ± 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.65 ± 0.23 | -0.56 ± 0.21 | < 0.05 | 0.61 | |||||

| F2 (SAA, BUN, NEFA) | -0.20 ± 0.25 | 0.13 ± 0.25 | 0.37 | -0.46 ± 0.26 | 0.39 ± 0.24 | 0.02 | 0.52 | |||||

| F3 (Glucose) | 0.35 ± 0.24 | -0.31 ± 0.24 | 0.06 | 0.28 ± 0.25 | -0.24 ± 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.31 | |||||

| ST4 | ||||||||||||

| F1 (SAA, Glucose, Alb) | 0.26 ± 0.24 | -0.18 ± 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.53 ± 0.25 | -0.46 ± 0.23 | < 0.05 | 0.38 | |||||

| F2 (Cholesterol, BUN) | -0.14 ± 0.18 | 0.03 ± 0.18 | 0.48 | -0.79 ± 0.19 | 0.68 ± 0.17 | < 0.05 | 0.24 | |||||

| F3 (BHBA, NEFA, Triglyceride) | -0.24 ± 0.28 | 0.24 ± 0.28 | 0.24 | -0.006 ± 0.3 | 0.005 ± 0.27 | 0.97 | 0.51 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).