1. Introduction

Genetic selection, together with improved management of non-genetic factors in dairy farming, has transformed the phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of the Holstein cow, especially since the mid-1960s, leading to dramatic increases in milk yield as well as other traits [

1,

2,

3]. Compared to extensive investigations that examined the influences of non-genetic factors, including health, nutrition, and husbandry on milk components [

4,

5,

6,

7], the impacts of long-term genetic selection were rarely explored due to limited availability of experimental models. Moreover, the existing comparisons on this topic through historical records are often confounded by the non-genetic factors [

6,

8]. In 1964, as part of a regional research effort on genetic selection, Dr. Charles Young initiated a breeding project at the University of Minnesota, that produced a static, unselected Holstein (UH) genotype and a contemporary Holsteins (CH) genotype that continually reflected changes in US selection practices [

9,

10,

11,

12]. The milk yield of UH cows has remained largely unchanged and thereof represents the status of the US Holstein population in the early 1960s. In contrast, the milk yield of CH cows is on par with the current US Holsteins and the difference between multiparous UH and CH cows in milk yield has already surpassed 4,500 kg/305 d lactation [

3,

12]. Many features of UH and CH cows, including reproduction, endocrine, metabolic health, have been compared [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Although an initial evaluation of the fatty acids in milk from UH and CH cows has been reported [

13], a more comprehensive evaluation of their milk lipids during the dynamic transition period is warranted.

Dairy products from cow milk play a significant role in human nutrition [

14,

15]. Lipid content is a major determinator of the value and nutritional properties of cow milk. As the dominant lipid species, triacylglycerols (TAGs) in milk contain both

de novo fatty acids that are synthesized from short-chain carboxylic acids (mainly acetate and 3-hydroxybutyric acid) within the mammary gland and preformed fatty acids that are absorbed from the blood stream [

6]. Preformed fatty acids originate from multiple sources, including dietary lipids, lipogenesis in the liver and adipose tissue, and rumen fermentation, such as odd-chain (C15 and C17) fatty acids produced by rumen microbes [

16]. Because of the structural diversity of milk fatty acids (more than 400) and the availability of 3 hydroxyl groups in the glycerol backbone of TAGs for the esterification reaction with fatty acids, milk fat is more complex than many other natural fats [

6,

17]. Examining the composition of milk fatty acids and the factors that affect the contribution of individual fatty acids to fat synthesis continues to be a topic of interest in dairy research [

18,

19,

20]. For example, associations between genetic polymorphisms and presence of predominant milk fatty acids could help develop breeding programs designed to alter the fatty acid content of milk [

21]

Lipidomics has become a robust and versatile platform for phenotyping milk samples from different species, physiological status, and physical conditions [

19,

22,

23,

24]. In this study, the comprehensive liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS)-based lipidomic analysis, covering individual TAGs, fatty acids, and short-chain carboxylic acids, was conducted to compare milk samples from UH and CH cows in the first 9 weeks of lactation. Since these lipid metabolites in milk are the products of many essential metabolic processes, differences between UH and CH cows are expected to reveal the consequences of genetic and metabolic alterations from 60 years of selection.

2. Materials and Methods

Chemicals and reagents. LC-MS-grade water, acetonitrile (ACN), and isopropanol (IPA) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Houston, TX); 2-hydrazinoquinoline (HQ) and triphenylphosphine (TPP) from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA); 2,2’-dipyridyl disulfide (DPDS) from MP Biomedicals (Santa Ana, CA); n-butanol, short-chain carboxylic acids, carnitine and acylcarnitines from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO); fatty acid standards from Nu-Chek-Prep (Elysian, MN); 1,2-13C2-palmitic acid from CDN Isotopes (Pointe-Claire, QC, Canada).

Animals, experimental design, and sample collection. Multiparous UH and CH cows (n = 12/genotype) were housed together for at least 5 weeks prior to parturition and fed the same pre- and postpartum diets throughout the study. Diets were formulated as TMR designed to meet the nutritional needs of contemporary Holsteins [

25] and cows were fed once daily. Cows were milked at approximately 12-h intervals and daily milk yields determined from recorded milk weights. Milk samples for nutrient and lipidomic analyses were collected at every Tuesday night milking during the first 9 weeks of lactation with aliquots either stored at -80°C until subsequent processing for metabolite analysis or preserved with dichromate and submitted (Minnesota Dairy Herd Improvement Association Laboratory; Zumbrota, MN) for determination of macronutrient (protein, lactose, and fat) content using infrared spectroscopy. Energy balance of the cows was determined according to NRC (2001) [

25] as described by Carriquiry et al. (2009) [

26]. Animals were observed daily for health abnormalities and treated when warranted. Animal care and experimental procedures were approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (1207B17664, approval date 07-18-2012).

LC-MS analysis of milk lipids. To solubilize the neutral lipids, whole milk was vortexed at room temperature for 5 sec before 5 µL of this homogenized milk was mixed with 245 µL of n-butanol and vortexed for another 5 sec. This vortexed mixture was centrifuged at 18,000×g for 10 min to remove proteins and precipitates. The supernatant was transferred to a HPLC vial for the LC-MS analysis. To conduct the LC-MS analysis, 5 µL of aliquot of the supernatant was injected in to an Acquity ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) system (Waters, Milford, MA) and components separated by a BEH C8 column (Waters) using a mobile phase gradient, A: H

2O:ACN=60:40 (v/v) containing 0.1% formic acid (v/v) and 10 mM ammonium acetate and B: IPA:H

2O=90:10 (v/v) containing 0.1% formic acid (v/v) and 10 mM ammonium acetate. The UPLC eluant was introduced into a Xevo-G2-S quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (QTOFMS, Waters) for accurate mass measurement and ion counting. Capillary voltage and cone voltage for electrospray ionization were set at 3 kV and 30 V for positive-mode detection, respectively. Source temperature and desolvation temperature were set at 120°C and 350°C, respectively. Nitrogen was used as the cone gas (50 L/h) and the desolvation gas (600 L/h) and argon as collision gas. For accurate mass measurement, the mass spectrometer was calibrated with sodium formate solution with mass-to-charge ratio (

m/z) of 50–1000 and monitored by the intermittent injection of the lock mass leucine enkephalin ([M + H]

+ =

m/z 556.2771 and ([M − H]

− =

m/z 554.2615) in real time. Mass chromatograms and mass spectral data were acquired and processed by MassLynx

TM software (Waters) in centroided format. Additional structural information was obtained from tandem MS (MSMS) fragmentation with collision energies ranging from 15 to 40 eV [

27].

LC-MS analysis of milk fatty acids. Milk lipids were hydrolyzed to release free fatty acid using a modified alkaline hydrolysis method [

28]. Briefly, 5 µL of milk sample was mixed with 200 µL of methanol containing 200 µM 1,2-

13C

2-palmitic acid as the internal standard, and then hydrolyzed by adding 35 µL of 40% potassium hydroxide (w/v). The mixture was incubated at 60 °C for 30 min and then neutralized by 60 µL of 2.5 M HCl and 200 µL of phosphate buffer (75 mM, pH=7). After a 10-min centrifugation at 18,000 × g, the supernatant containing free fatty acids was collected and further derivatized for LC-MS analysis. To derivatize free fatty acids, 2 µL of sample or fatty acid standard was mixed with 100 µL of freshly prepared master reaction solution containing 1 mM DPDS, 1 mM TPP, and 1 mM HQ in ACN. The mixture was incubated at 60 °C for 30 min and chilled on ice for 10 min. The reaction was terminated by mixing with 100 µL of H

2O. After a 10-min centrifugation at 18,000×g, the supernatant was transferred into an HPLC vial. For LC-MS analysis, 5 µL of HQ-derivatized sample was injected into an Acquity ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) system (Waters, Milford, MA) and separated by a BEH C18 column (Waters) using a gradient ranging from water to 95% aqueous ACN containing 0.1% formic acid over a 10-min run.

LC-MS analysis of milk short-chain carboxylic acids. Milk samples were derivatized by HQ, without hydrolysis, for the LC-MS analysis of short-chain carboxylic acids [

29]. The derivatization procedure, LC gradient, and the MS parameters are the same as the ones used for the LC-MS analysis of free fatty acids, except the mobile phase, which contained A: H

2O containing 0.05% acetic acid (v/v) and 2 mM ammonium acetate and B: H

2O:ACN=5:95 (v/v) containing 0.05% acetic acid (v/v) and 2 mM ammonium acetate.

Marker identification through multivariate data analysis. Chromatographic and spectral data from LC-MS analysis of milk samples were visualized in 2-D plots using MZmine software [

30], and deconvoluted by MarkerLynx

TM software (Waters). A multivariate data matrix containing information on sample identity, ion identity [retention time (RT) and

m/z], and ion abundance was generated through centroiding, deisotoping, filtering, peak recognition, and integration. The intensity of each ion was calculated by normalizing the single ion counts (SIC) versus the total ion counts (TIC) in the whole chromatogram. The processed data matrix was further exported into SIMCA-P+

TM software (Umetrics, Kinnelon, NJ), transformed by

Pareto scaling and analyzed by principal components analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA). Major latent variables in the data matrix were described in a scores scatter plot of defined multivariate model. Potential metabolite markers of genetic selection for high milk yield were identified by analyzing ions contributing to the separation of sample groups in an S-loadings plot of OPLS-DA model. After

Z score transformation, the concentrations or relative abundances of identified metabolite markers in examined samples were presented in the heat maps generated by the R program (

http://www.R-project.org), and correlations among these metabolite markers defined by hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA).

Marker characterization and quantification. The chemical identities of metabolite markers were determined by accurate mass measurement, elemental composition analysis, database search, MSMS fragmentation, and comparisons with authentic standards if available. Database searches were performed using Human Metabolome Database (HMDB), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), and Lipid Maps databases. Individual metabolite concentrations were determined by calculating the ratio between the peak area of metabolite and the peak area of internal standard and fitting with a standard curve using QuanLynxTM software (Waters).

Statistical analysis. Cows were blocked (1 per genotype) by actual calving date (< 21 d interval within any block). Effects of genotype, week of lactation and their interactions on milk yield and component concentration profiles were analyzed by repeated measures using PRO MIXED procedure of SAS with week of lactation as the repeated effect. Experimental values are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and considered to differ when P < 0.05.

3. Results

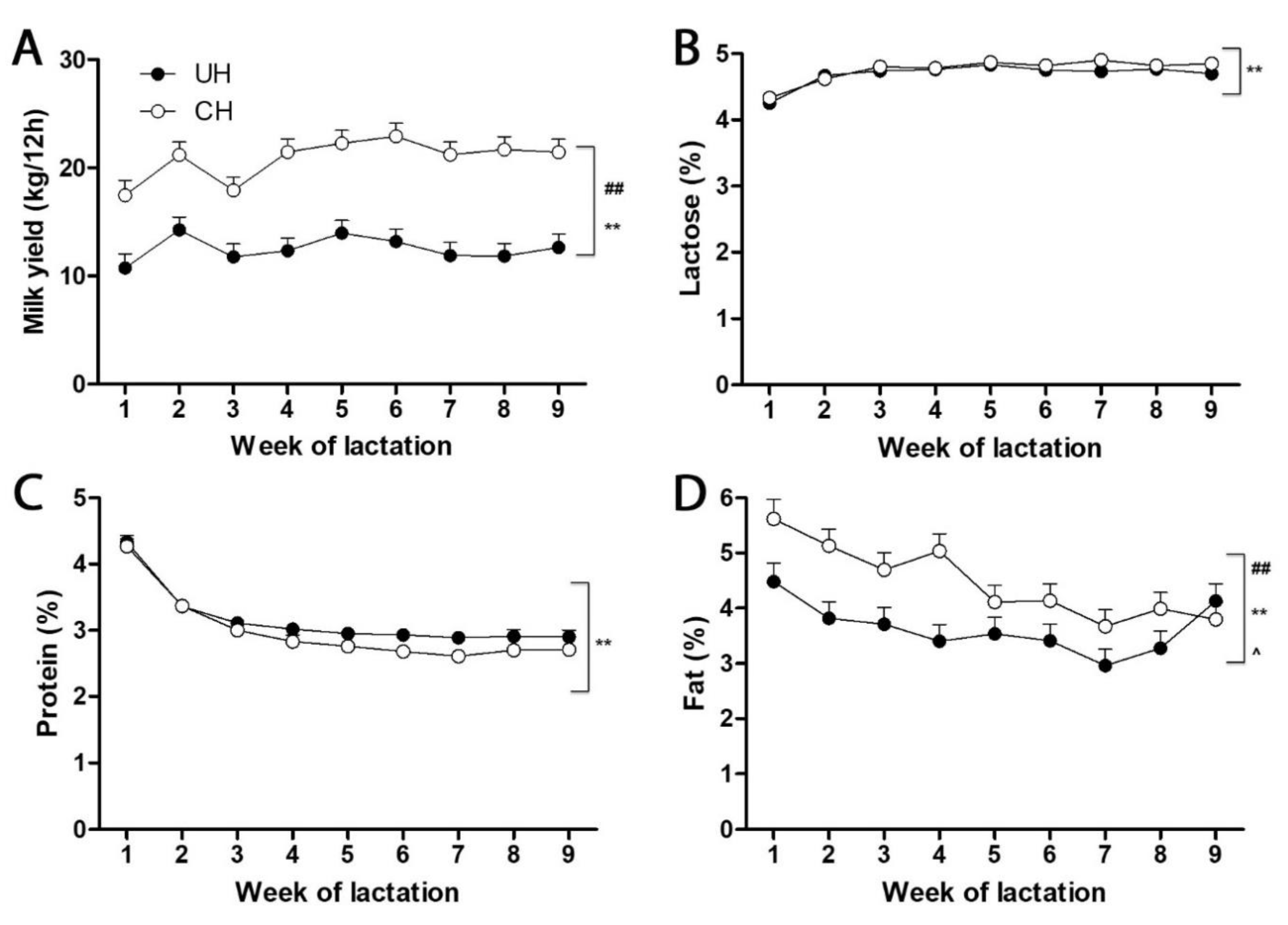

Milk yield, milk macronutrient content, and energy balance of the cows. During weeks 1 to 9 of lactation, CH cows produced more milk than UH cows (

Figure 1A). This difference in milk yield is consistent with the status of postpartum energy balance in two genetic lines, i.e., the energy balance at week 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 of lactation was -4.47, -2.71, -0.68, 1.28, 1.16, 1.36, 2.93, 2.05 and 3.98 Mcal net energy of per day (NE

L/d), respectively, for UH cows, while -14.8, -11.8, -8.76, -6.95, -6.29, -5.92, -4.17, -4.55, and -2.33 Mcal NE

L/d, respectively, for CH cows. Among the macronutrients in milk, the concentrations of lactose and protein were comparable between UH and CH milk (

Figure 1B-C). In contrast, CH milk contained more fat than UH milk (

Figure 1D). Therefore, genotype and energy status affected the fat and lipid content of cow milk more than its lactose or protein contents. Time-dependent alterations in milk yield, lactose, protein, and fat occurred in UH and CH cows (

Figure 1A-D). Moreover, a genotype-time interaction was observed for milk fat content as the difference between UH and CH milk fat in week 1 gradually decreased during the first 9 weeks of lactation (

Figure 1D).

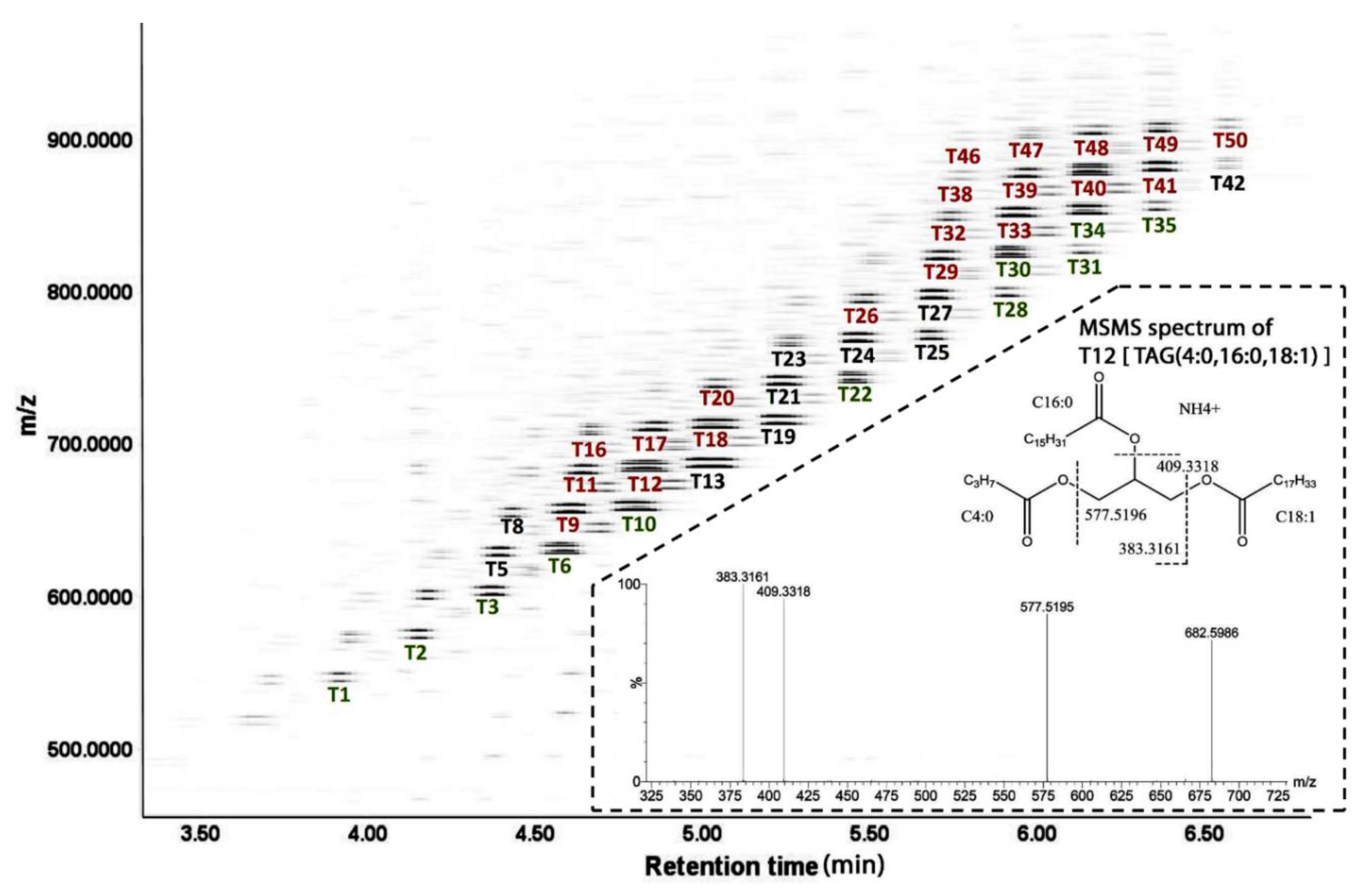

TAGs in UH and CH milk. The LC-MS-based lipidomic analysis of UH and CH milk detected hundreds of TAG species with different molecular weights, unsaturation levels, and abundances (

Figure 2). As exemplified by the MSMS spectrum of T12 [TAG (4:0, 16:0, 18:1)] in the insert of

Figure 2, the fatty acid composition of 50 major TAG species were determined based on the product ions from MSMS fragmentation (

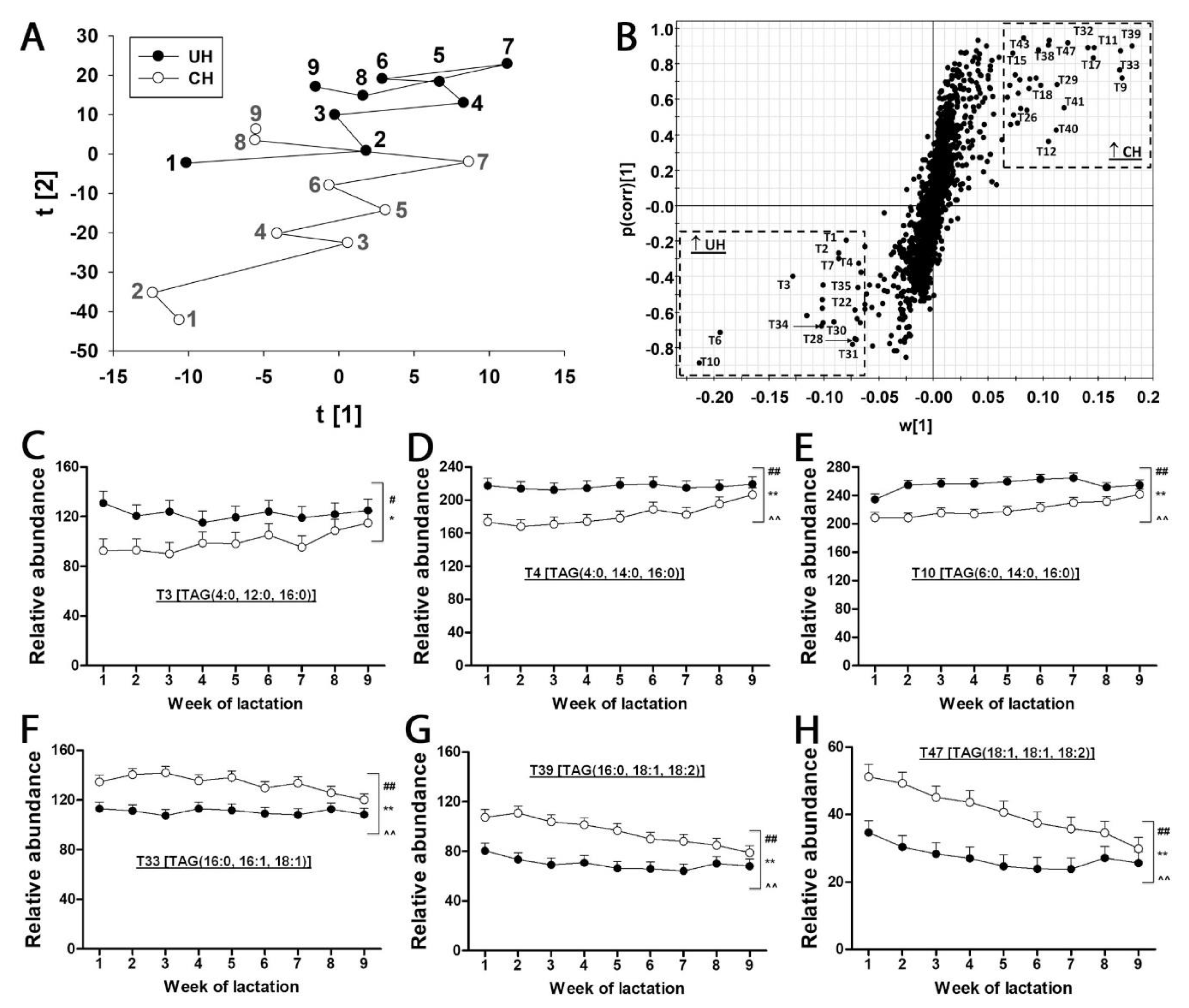

Table 1). The composition of milk lipids was defined by a PCA model, in which the distribution patterns of weekly samples reflect the differences between UH and CH milk and the kinetics of their compositional changes during the first 9 weeks of lactation (

Figure 3A). As indicated by the distances between weekly CH and UH means in the model, the differences between UH and CH in the first three weeks of lactation were much greater than the differences at week 9 of lactation (

Figure 3A). Moreover, the distances between week 1 and week 9 in the model indicate that the composition of CH milk underwent more dramatic changes than that of UH milk (

Figure 3A). The TAG markers positively associated with CH or UH milk were identified in the loadings S-plot of an OPLS-DA model (

Figure 3B and

Table 1). Interestingly, all identified TAG markers of UH cows contain at least two fatty acids with their aliphatic tails no longer than 16 (≤ 16) carbons (

Figure 3C-E and

Table 1), while all identified TAG markers of CH cows contain at least two fatty acids with their aliphatic tails no shorter than 16 (≥ 16) carbons (

Figure 3F-H and

Table 1). Furthermore, the relative abundances of these markers became more comparable between two genotypes at week 9 of lactation (

Figure 3C-H), which is consistent with the pattern of sample distribution in the PCA model (

Figure 3A). In addition to genotype-dependent differences in the relative abundances and fatty acid composition of milk TAGs, time (week of lactation) and genotype-time interactions also impacted the relative abundance of these identified TAG markers (

Figure 3C-H).

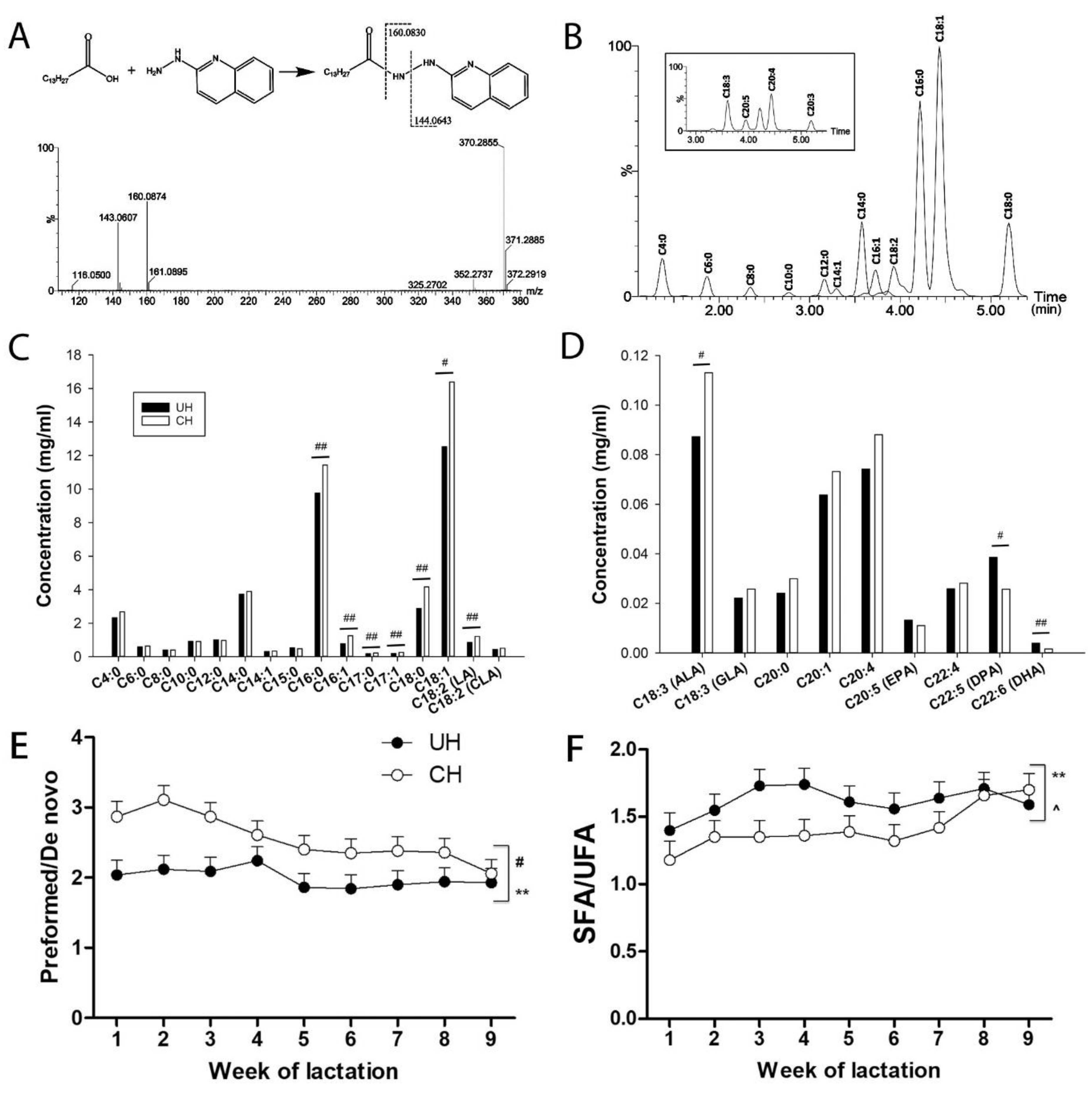

Fatty acid compositions of UH and CH milk. To further characterize the genotype-dependent difference in the fatty acid composition of milk TAGs, the concentrations of fatty acids in hydrolyzed milk were determined by the LC-MS analysis of their hydrazide derivatives formed by the reactions with 2-hydrazinoquinoline (HQ), as shown by the MSMS spectrum of myristic acid (

Figure 4A). Using this method, 27 fatty acids with aliphatic chains ranging from 4 to 22 carbons (C4-C22) in milk were detected and quantified (

Figure 4B and

Table S1). The results from calculating the average concentrations of individual fatty acids in all 9 weeks of lactation showed that CH milk had higher concentrations of C16-18 fatty acids, except conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) and γ-linolenic acid (GLA), than UH milk (

Figure 4C-D and

Figure S1G-K), while the concentrations of C4-14 fatty acids were comparable between these genotypes (

Figure 4C and

Figure S1A-F). The average concentrations of docosapentaenoic acid (DPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), two ω-3 fatty acids, were lower in CH milk than that in UH milk, even though the concentration of α-linolenic acid (ALA), their precursor, was greater in CH milk (

Figure 4D). The total fatty acid concentration was greater in CH milk than in UH milk (

Figure S2L), which is consistent with the fat contents in these milk samples (

Figure 1D). Interestingly, when these fatty acid concentrations were converted to their relative abundance (%) in the total sum of measured fatty acids, several of the C8 to C14 fatty acids, including caprylic acid (C8:0), lauric acid (C12:0), and myristic acid (C14:0), had greater relative abundances in UH than in CH milk (

Figure S1A-F) while the abundances of most C16 to C18 fatty acids, except palmitoleic acid (C16:1) and linoleic acid (C18:2), were comparable between UH and CH milk (

Figure S1G-L). The ratio of preformed

versus de novo FA, defined by (C17-C22)/(C4-C14), was relatively stable in UH milk but gradually decreased in CH milk (

Figure 4E). Moreover, the ratio of saturated fatty acids (SFA)

versus unsaturated fatty acids (UFA) were impacted by time and a genotype-time interaction, but not by genotype alone (

Figure 4F).

Short-chain carboxylic acids in UH and CH milk. Short-chain carboxylic acids are precursors in

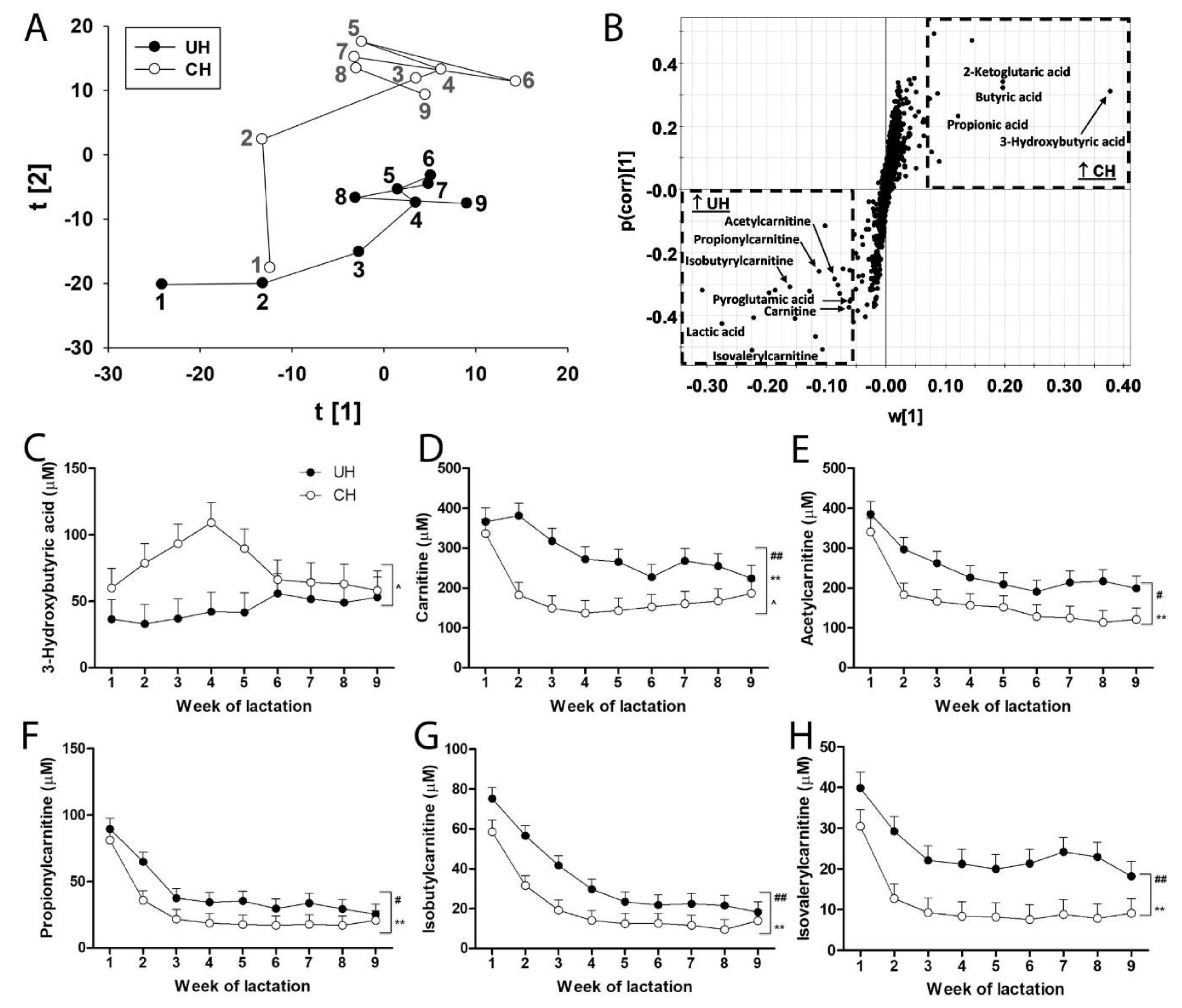

de novo fatty acid synthesis as well as metabolites in fatty acid oxidation and transport. Their profiles in UH and CH milk during the first 9 weeks of lactation were defined by LC-MS analysis and multivariate modeling. The distribution of weekly UH and CH samples in the scores plot of a PCA model revealed genotype-dependent differences and time-dependent changes in short-chain carboxylic acids, especially during the first 3 weeks of lactation (

Figure 5A). Further analysis of the short-chain carboxylic acids contributing to the genotype-dependent separation in the loading S-plot of the OPLS-DA model identified butyric acid, propionic acid, 3-hydroxybutyric acid and 2-ketoglutaric acid as markers that were positively associated with CH milk and carnitine, acetylcarnitine, propionylcarnitine, isobutyrylcarnitine, isovalerylcarnitine, pyroglutamic acid and lactic acid as markers that were positively associated with UH milk (

Figure 5B).

There was an interaction between genotype and time on concentrations of 3-hydroxybutyric acid (

Figure 5C), carnitine (

Figure 5D) and butyric acid (

Figure S3A). These interactions were mainly due to the occurrence of transient (N = 4 cows) and persistent (N = 2 cows) subclinical ketosis (milk 3-hydroxybutyric acid > 100 µM) in individual CH cows (

Figure S2). Removing the 2 cows with persistent subclinical ketosis from the analysis (data not shown) eliminated the genotype-time interaction on the concentration of 3-hydroxybutyric acid, carnitine and butyric acid but did not alter the effects of genotype or week on carnitine. Removing these 2 cows also did not alter the effects of genotype or time on the concentrations of any of the 4 carnitine metabolites (

Figure 5D-H). The UH milk consistently contained more of these carnitine metabolites than CH milk. Concentrations of these carnitine metabolites decreased from week 1 through 4 in milk from UH and CH cows and remained relatively stable thereafter (

Figure 5D-H). Concentrations of lactic acid, the other marker we identified as positively associated with UH milk, were greater in UH than in CH milk (

Figure S3B).

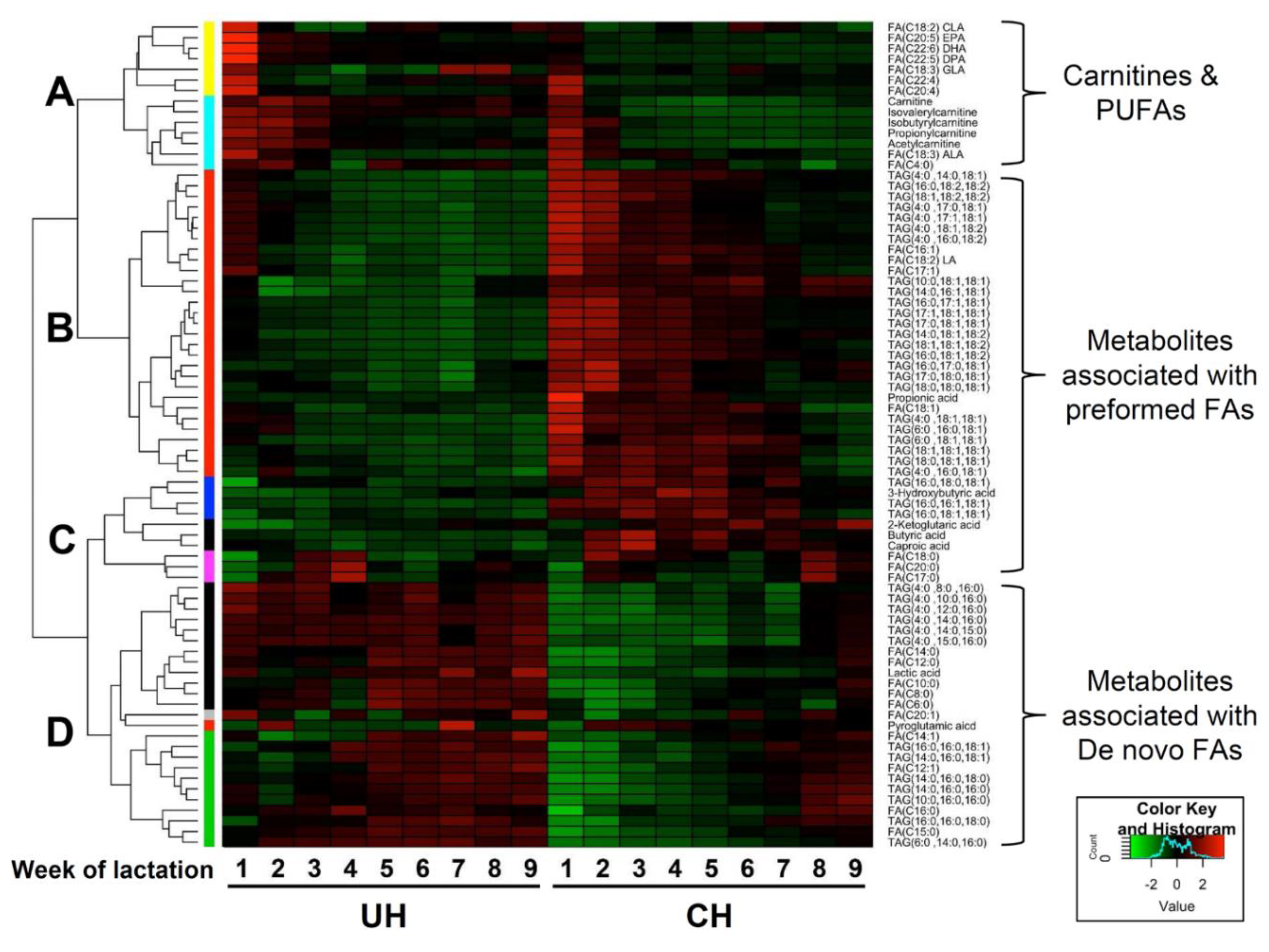

Clustering analysis of UH and CH milk lipidomes. The hierarchical clustering analysis based on the relative abundances of identified TAGs, FAs, and short-chain carboxylic acids during the first 9 weeks of lactation produced a heat map with 4 major clusters (

Figure 6). Cluster A contains metabolites that were more abundant in UH milk and that also gradually decreased in both CH and UH milk during the first 9 weeks of lactation. Cluster A included carnitines and PUFAs. Clusters B and C contain the metabolites that were more abundant in CH milk. These clusters were mainly comprised of preformed fatty acids, the TAGs with at least two preformed fatty acids, and free SCFAs from rumen fermentation. Cluster D contains the metabolites that were more abundant in UH milk and did not decrease as lactation progressed, including

de novo fatty acids, TAGs with at least two

de novo fatty acids, and lactic acid.

4. Discussion

Continuous selection efforts for greater milk yield have led to significant changes in the genome and metabolic system of dairy cattle as well as the milk they produce [

1,

3,

12,

13]. Milk synthesis utilizes end products from anabolic and catabolic metabolism in multiple organs and tissues of dairy cows, including mammary gland, liver, adipose, and rumen. Therefore, alterations in these metabolic processes are expected to impact the volume of milk produced by a cow as well as its compositional profile. The results from this lipidomic study on genetic selection match this expectation since dramatic changes in milk lipid composition were observed in UH and CH cows during the transition across parturition and early lactation, which is the most dynamic interval of metabolic alterations for a cow. Moreover, the magnitude of compositional changes was greater in CH than in UH milk, reflecting the consequences of genetic selection. The primary drivers of these time-dependent changes and genotype-dependent differences are likely associated with differences in energy status and metabolic adaptations in CH and UH cows. The observed differences between UH and CH cows in TAGs, fatty acids, carnitines and other short-chain carboxylic acids are discussed based on their potential causes and significances as follows.

TAGs and fatty acids: The Minnesota breeding program was designed to increase milk yield by the CH cows while maintaining a relatively static milk yield by the UH cows [

9]. Besides this difference in milk yield between the UH and CH cows [

12,

13], the differences in major milk components, especially TAGs, were also observed in the current study. As the most abundant and energy-intensive constituent in milk, the TAGs in early-lactation milk can reflect the metabolic alterations associated with negative energy balance in this transition period [

31]. In the current study, this association is reflected by the fact that the CH cows experienced a more negative energy balance and had a greater increase in milk TAGs during early lactation than the UH cows. Moreover, early lactation milk underwent time-dependent changes in TAG profile due to the compositional changes in their fatty acids, especially in CH milk. Interestingly, by week 9 of lactation, the TAG profile and fatty acid composition of CH and UH milk became much more comparable, indicating similar metabolic status between them after the transition phase.

Among the fatty acids in milk TAGs, C4-C14 fatty acids mainly originate from

de novo fatty acid synthesis in the mammary gland, C17-C22 fatty acids from preformed fatty acids in blood lipids, and C16 fatty acids from both sources [

6,

7]. A prominent observation on milk fatty acids in the current study is the greater concentrations of preformed fatty acids in CH milk than those in UH milk (

Figure 4C), especially during the first 6 weeks of lactation (

Figure S1I-K). This phenomenon can be attributed to the prolonged interval of negative energy balance for greater milk yield in CH cows, which led to more mobilization of preformed fatty acids from other tissues and organs. In contrast, the concentrations of

de novo fatty acids were much more comparable between CH and UH milk (

Figure S1A-F), making preformed fatty acids, not

de novo fatty acids, as the main contributors to the different TAG profiles between UH and CH milk. This altered balance between preformed and

de novo fatty acids decreased the relative abundances of

de novo fatty acids in CH milk (

Figure 4E,

Figure S1), even though the absolute concentrations of

de novo fatty acids were still largely comparable between UH and CH milk (

Figure S1).

Transition cows experience physiological challenges posed by calving, the onset of lactation, and the associated interval of negative energy balance [

31]. Significant adjustments in body metabolism are required to accommodate the immediate postpartum increase in metabolic demand for milk production while the cow slowly increases her feed intake from the reduction that occurs prior to calving. The greater elevation of preformed fatty acids in CH milk are consistent with the CH cows having a greater metabolic demand than UH cows to mobilize fatty acids from body tissue to meet their greater energy needs and greater demand for substrates for milk TAG synthesis. Although fatty acids from tissue lipolysis generally provide a minor proportion of the fatty acids used for milk lipid biosynthesis, during negative energy balance mobilized fatty acids provide the majority of the fatty acids for milk lipid biosynthesis [

7]. Indeed, in a separate study on blood lipids, we observed that the concentrations of plasma non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) in CH cows were greater than those in UH cows through week 7 of lactation (data not shown). Further characterization of plasma lipid profiles will likely provide additional insights on the relationships between blood lipids and milk TAGs in UH and CH cows.

Carnitines and other short-chain carboxylic acids: Carnitine is a facilitator for the transfer of long-chain fatty acids into the mitochondria for β-oxidation as well as for the transport of short and medium chain fatty acids from peroxisomes to mitochondria [

32,

33]. The presence of carnitine and acylcarnitines in cow milk have been reported previously [

34,

35,

36]. The current study defined their kinetic profile in the early-lactation milk of UH and CH cow, showing that their concentrations in both UH and CH milk decreased dramatically in early lactation, and at the same time, UH milk consistently had more carnitine metabolites than CH milk (

Figure 5D-H). Since carnitine is only synthesized in the kidney, liver and brain, but in the mammary gland [

33], the carnitine content of UH and CH milk depend on the biosynthesis in these organs as well as active uptake from the circulation. Therefore, reduced biosynthesis, decreased uptake into mammary gland, and increased utilization could jointly or individually contribute to the decreased carnitine content in early postpartum UH and CH milk. In fact, postpartum decreases in milk carnitine have been documented [

35,

37] and attributed to periparturient alterations in hepatic synthesis of carnitine [

37,

38]. As for the reduced concentrations of carnitines in CH milk relative to UH milk, this difference between UH and CH cows could also be attributed to differential impacts of these factors in carnitine metabolism. For example, the more severe and longer interval of negative energy balance experienced by the CH cows most likely increased the use of carnitine for the metabolism and transport of mobilized NEFA, leading to reduced carnitine concentrations in CH milk.

Short-chain fatty acids and ketone bodies are both end products of fatty acid oxidation and substrates for fatty acid synthesis. In mammary epithelial cells, acetic acid and 3-hydroxybutyric acid are used for

de novo synthesis of fatty acids [

7]. Our results indicated greater increases of 3-hydroxybutyrate and butyric acid in CH milk. More specifically, dramatic elevation of 3-hydroxybutyrate occurred in half of the CH cows during the first 5 weeks of lactation, indicating transient or persistent subclinical ketosis. Interestingly, total carnitine concentrations in milk have been reported to be greater in ketotic cows than normal cows [

35]. In contrast, the 2 CH cows with persistent subclinical ketosis in the current study had the lowest milk carnitine concentrations (data not shown) of the CH cows. Further investigations might be needed to define the reasons for this discrepancy.