1. Introduction

Residents are key stakeholders in tourism destinations, playing a vital role in their evolution (Ganji et al., 2021). The residents’ support for tourism initiatives is paramount for ensuring the sustained prosperity and enduring vitality of such locales (Liang et al., 2021; Munanura et al., 2023; Qin et al., 2021). This significance is particularly pronounced in ethnic tourism villages, where residents often embody a ’dual identity’ as both custodians of tourism assets and primary attractions themselves. These residents possess firsthand knowledge of the tourism development process, experiencing both its advantages and challenges. In many ethnic tourism settings, local residents, acting as the ’living carriers’ of traditional cultural elements, actively or passively engage in the tourism evolution. Their traditions, cultural practices, warm hospitality, and daily interactions serve as major draws for tourists. Consequently, in comparison to other tourism destinations, the level of residents’ backing significantly impacts the prosperity and advancement of the local (Çelik & Rasoolimanesh, 2023; X. Li et al., 2023).

Academics have conducted pervasive research on residents’ support for tourism, frequently utilizing the Social Exchange Theory (SET) as the foundational framework to elucidate the genesis of such support (Santos et al., 2024). Within this framework, residents in tourism destinations are typically viewed as ’rational actors’ whose endorsement of tourism development is based on a careful evaluation of the ’benefit-cost’ ratio (Qin et al., 2021). However, empirical evidence has shown instances where residents exhibit support even when perceived costs (Nunkoo & Gursoy, 2016; Vargas-Sanchez et al., 2015). This discrepancy has led researchers to question the sufficiency of the SET framework and propose that factors beyond rational calculation may influence residents’ support for tourism (Qin et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020). Recent explorations infer that there might be vital determinants or mediatory mechanisms hitherto inadequately examined in comprehending the association between residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts and their ensuing support for tourism (Qi et al., 2023). These outcomes underscore the intricacy of resident support for tourism, urging the necessity to contemplate a more comprehensive selection of influences extending beyond the confines of traditional theoretical frameworks.

This study endeavors to develop a novel conceptual model by amalgamating Social Exchange Theory and Tolerance Zone Theory, introducing the element of tolerance for tourism into the established research framework of “residents’ perceived tourism impact - tourism support.” Through this endeavor, the study showcases its innovation in two primary dimensions. Firstly, it delves into the intricate process of residents’ support formation in tourist destinations, thereby broadening and enriching the conventional research paradigm of “residents’ perceived tourism impact—tourism support.” Secondly, it skillfully integrates Social Exchange Theory with Tolerance Zone Theory, thereby providing a comprehensive and insightful analysis of residents’ support for tourism, aligning with prior research appeals for theoretical integration to facilitate a thorough analysis of residents’ backing for tourism (Çelik & Rasoolimanesh, 2023; Gautam, 2023; Nugroho & Numata, 2022).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Ethnic Tourism

Smith (1977) defines ethnic tourism as tourism activities involving “exotic peoples,” encompassing visits to native homes, observing traditional dances and ceremonies, and purchasing authentic handicrafts. At the core of ethnic tourism lies culture, with ethnic villages or indigenous communities often serving as the primary settings for its manifestation (Zhang et al., 2017). Consequently, ethnic tourism is intricately linked to the active involvement of ethnic village residents.

The residents of these ethnic villages play a pivotal role in propelling ethnic tourism forward (Y. Yang et al., 2022). The rich tapestry of traditions and lifestyles exhibited by indigenous peoples acts as a major draw for tourists (Nielsen & Wilson, 2012). While extant research has delved into the consequences of ethnic or indigenous tourism development on local residents, there persists a lacuna in comprehending the attitudes and behaviors of these residents towards tourism development from their own vantage perspectives (L. Yang & Wall, 2009). Furthermore, studies specifically concentrating on minority villages or indigenous communities remain relatively scarce (Wang et al., 2020).

2.2. Resident Support for Tourism

Historically, research revolving around resident support for tourism has demonstrated a significant correlation with attitudinal aspects. Prayag et al. (2013) highlight the substantial ambiguity in the relationship between resident attitudes and support. Many studies have traditionally treated resident tourism attitudes and tourism support as interchangeable, viewing resident tourism support merely as an attitudinal variable (Dyer et al., 2007). However, scholars have progressively differentiated resident tourism support from attitudes, recognizing it as a distinct construct representing a willingness to engage or pro-tourism behavior (Liu et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2024).

The subject of residents’ support for tourism firmly remains as one of the most exhaustively investigated domains within the tourism research field, consequently attracting considerable interest from researchers (Santos et al., 2024). Perdue et al. (1990) were pioneers in examining this aspect, proposing a structural model to grasp the genesis of residents’ support for tourism, albeit lacking robust theoretical underpinnings. Subsequently, researchers have endeavored to scrutinize residents’ support for tourism from a theoretical perspective. Notably, Ap (1992) introduced social exchange theory from sociology into tourism research, shedding light on the exchange processes influencing residents’ perceived tourism impact.

The integration of social exchange theory into tourism research has been widely embraced by scholars. Expanding upon Perdue’s model and Ap’s theoretical framework, various research models have emerged to explore residents’ support for tourism. For instance, Jurowski et al. (1997) devised a path model to investigate residents’ support within the social exchange theory context. Similarly, Ng and Feng (2020) and Gursoy et al. (2017) formulated structural models based on this rationale, culminating in a substantial body of literature on residents’ support for tourism grounded in social exchange theory.

Previous studies have generally found a consensus in research on supportive behavior when destination residents perceive benefits (positive impact), with residents’ perceived benefits positively correlating with their tourism support (Gursoy et al., 2019; Santos et al., 2024). Nonetheless, inconsistent findings have been observed in research exploring the nexus between perceived costs (or negative impacts) and tourism support. Some studies denote a negative relationship between residents’ apprehension of potential drawbacks and their inclination to endorse tourism (Munanura & Kline, 2023; Nugroho & Numata, 2022). Conversely, other research suggests no substantial correlation exists between residents’ perception of such costs (negative impacts) and their endorsement of tourism (Çelik & Rasoolimanesh, 2023; Qi et al., 2023).

The contentious findings have spurred scholars to question the comprehensive explanatory power of social exchange theory (SET). This skepticism has prompted calls for a deeper understanding through theoretical integration. Notably, Nunkoo and Gursoy (2012) merged Identity Theory with SET, while the Emotional Solidarity Theory has been integrated by Erul et al. (2020), Hasani et al. (2016), Woosnam and Aleshinloye (2015), X. Li and Wan (2016) also incorporated the Theory of Place Attachment into this integrative approach. Gautam (2023) combined social exchange theory, emotional solidarity theory, and bottom-up spillover theory to explore the precursors of tourism support. Hateftabar and Rasoolimanesh (2023) endeavored to blend social exchange theory with Weber’s theory to investigate the antecedents of support for tourism. These advancements signify a shift towards theoretical integration in the examination of residents’ support for tourism, aiming to offer a more holistic analysis of its internal formation mechanisms.

3. Hypothesized Model

3.1. Tourism Impacts and Resident Support: Social Exchange Theory

Social exchange theory, as formulated by Homans (1961), posits that humans are rational beings engaging in social interactions characterized by exchanges of tangible and intangible benefits and costs. The fundamental premise of this theory is that human interactions, or exchange behaviors, are rational endeavors aimed at maximizing benefits and minimizing costs, with all human actions being motivated by the pursuit of self-interest (Gao, 2005).

Within this theoretical structure, it is postulated that residents’ backing for tourism materializes from their interpretation of its effects, which tentatively span across various dimensions - namely, economic, social, cultural, and environmental aspects (Gong et al., 2023; Teng & Chang, 2020). These impacts are commonly divided into positive and negative aspects (Maksim Godovykh et al., 2023; Nugroho & Numata, 2022). From a cost-benefit perspective, several researchers categorize the positive impacts of tourism as benefits, while viewing the negative impacts as costs. (Qi et al., 2023; Tam et al., 2023).

In accordance with the tenets of Social Exchange Theory, scholars propose that the liaisons between local inhabitants and tourism can be conceptualized as a mutual exchange of resources. When residents witness tangible benefits from tourism, their inclination towards promoting its continuous growth intensifies. On the other hand, perceiving the costs or adverse ramifications of tourism development could possibly incite them to oppose its further expansion (Gjerald, 2005).

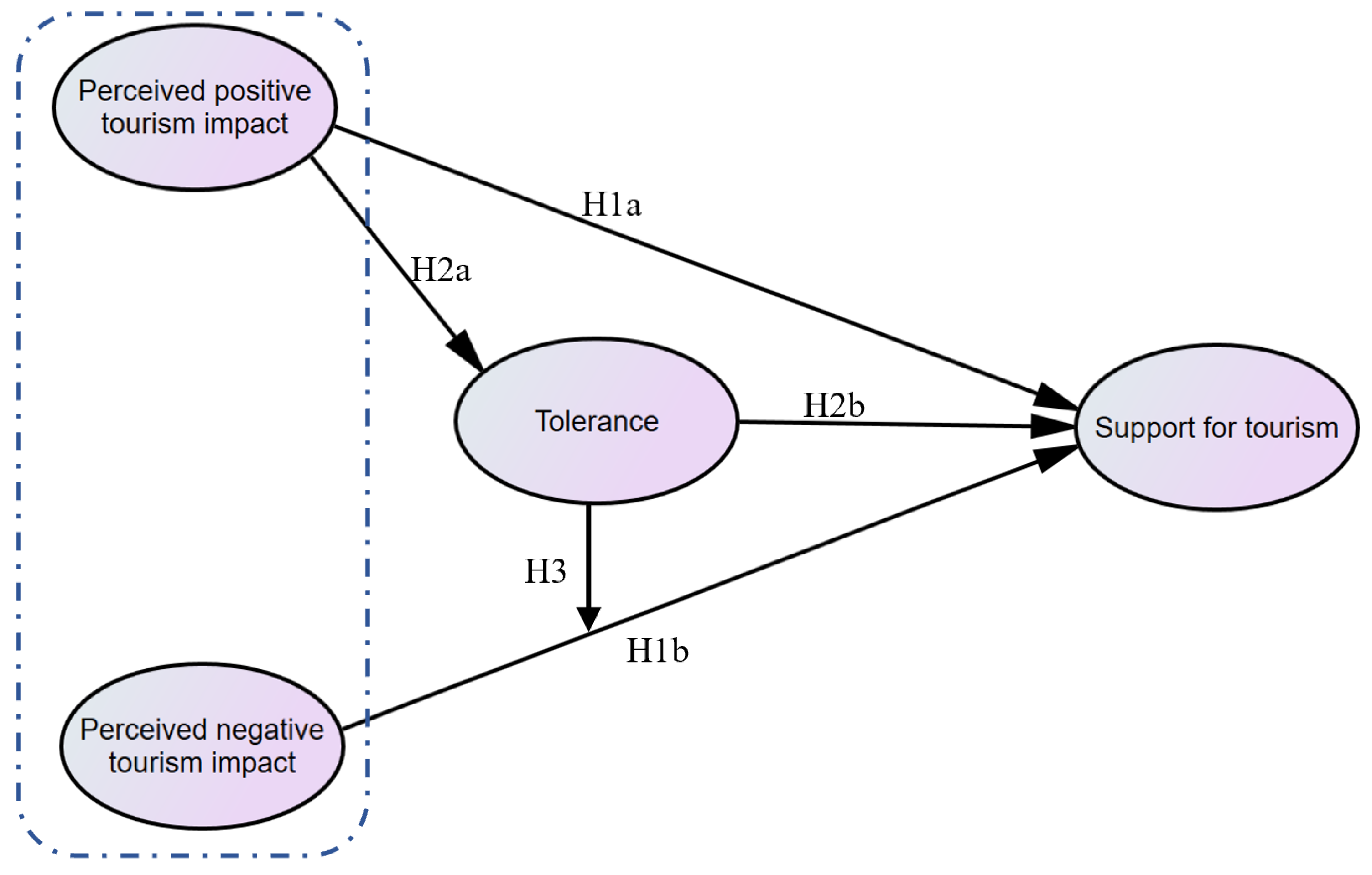

In light of the preceding analysis, this study conjectures and puts forth the following hypotheses.

H1a: There is a positive correlation between residents perceived positive tourism impact and support for tourism.

H1b: There is a negative correlation between residents perceived negative tourism impact and support for tourism.

3.2. The Role of Tolerance: Zone of Tolerance Theory

Muldoon et al. (2011) regard tolerance as the act of tolerating or putting up with something you do not like. McLain (1993, 2009) posits that the concept of tolerance and intolerance characterizes a spectrum of reactions, which extend along a continuum that stretches from outright rejection to full acceptance. Parasuraman et al. (1991) have applied this concept to the study of service management and put forward the concept of Zone of Tolerance(ZOT). The zone of tolerance refers to a psychological acceptance span of customers, within which customers find the service they receive acceptable. Customers within the tolerance zone are less sensitive to changes in service quality compared to those outside the zone.

In tourism literature, Ap and Crompton (1993) described tolerance as a slight degree of acceptance, meaning that residents accept the inconvenience or cost associated with tourism development. According to the study of Mansfeld and Ginosar (1994), they ascertained that residents of tourist destinations possess an inherent social carrying capacity threshold towards tourism development. Upon exceeding this threshold, residents begin to manifest their frustration and discontent with the existing state of tourism development. This limit is referred to as “the level of tolerance”. Stewart et al. (2006) propose that tolerance does not merely encompass the binary question of residents’ acceptance or rejection towards tourism development. It primarily involves residents’ response to adverse factors. They prompt a deeper exploration: to what degree and in what manner are residents prepared to tolerate the effects of tourism? Drawing on previous researchers’ definitions of tolerance, as well as definitions from the fields of psychology and service management, and considering the context of ethnic villages, this study defines tolerance for tourism as the reaction of destination residents to the negative effects (or adverse effects) caused by tourism development, which spans a continuous range from rejection to acceptance.

Existing studies have explored the influence of residents’ tolerance on their support for tourism, emphasizing its significance in three key aspects.

Relationship Between perceived positive tourism impact and Tolerance. Tolerance for tourism is closely linked to residents’ perceived benefits. The argument is that perceived benefits precede and enhance tolerance towards tourism. Qi et al. (2016) identified that a positive correlation exists between residents’ tolerance and their perception of positive tourism impact. Concurrently, Qi et al. (2023) reinforced this notion, uncovering a substantive positive association between perceived benefits and tolerance. This result aligns with the findings of Zajac et al. (2012), who corroborated that perceived advantages can efficaciously augment individual acceptance. Lischka et al. (2008) also recognized the perception of impacts as a critical factor in acceptance decisions.

Tolerance as a Key Factor in Supporting Tourism. Some researchers have identified residents’ tolerance as a pivotal factor in fostering support for tourism. For instance, Qiu Zhang et al. (2017) suggested that social acceptance reflects local residents’ acceptance and appreciation of tourism and its development. Qi et al. (2023) posited that tolerance could indicate the dynamic change in residents’ support for tourism. Qi et al. (2016) highlighted residents’ tolerance has the potential to bolster support for tourism, with higher tolerance levels leading to increased overall support.

Mediating Role of Tolerance. Recognizing the aforementioned aspects, some studies have examined the mediating role of tolerance (Qi et al., 2016; Qi et al., 2023). These studies have discovered that tolerance plays the role of a mediator between residents’ perceptions of tourism impact and their support for tourism. Empirical outcomes suggest that tolerance partially mediates the relationship between residents’ perceptions of positive tourism impact and their endorsement of tourism.

In view of the above analysis, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H2a: Residents perceived positive tourism impact is positively correlated with residents’ tolerance for tourism;

H2b: Residents’ tolerance for tourism is positively correlated with their support for tourism;

H2c: Residents’ tolerance for tourism plays a mediating role between residents perceived positive tourism impact and their support for tourism.

In addition, certain studies have underscored the pivotal role that tolerance plays in the relationship between residents’ perceived negative tourism impact and their endorsement of tourism (Qin et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the role of tolerance presents itself as slightly contentious. Some studies postulate that residents’ tolerance performs a mediating role between perceived negative tourism impact and support for tourism. Essentially, residents’ perception of negative tourism impact influences their support for tourism via the degree of their tolerance (Qi et al., 2023).

Contradicting the viewpoint that residents’ tolerance is molded by their recognition of tourism benefits, several studies propose that perceived positive tourism impact does not directly influence tolerance. These investigations present the argument that tolerance serves as a moderating entity in the relationship between perceived negative tourism impact and support for tourism (Qin et al., 2021). This perspective aids in demystifying the inconsistent relationship previously observed in studies between perceived negative tourism impact and support for tourism. The hypothesis advanced is that the intensity of the negative relationship between perceived negative tourism impact and support for tourism hinges on the degree of residents’ tolerance. With a substantial level of tolerance among residents, the negative correlation between their perceived negative tourism impact and support for tourism diminishes in significance. Conversely, when tolerance is below a certain threshold, this negative relationship is more pronounced. Qin et al. (2021) demonstrated that tolerance tempers the negative relationship between perceived negative tourism impact and support for tourism. Similarly, Haukeland et al. (2013) noted varying degrees of tolerance can sway the relationship between negative impacts and acceptance. In a parallel vein, Riorini and Barusman (2016) probed how tolerance moderates the relationship between satisfaction, trust, inertia, and customer loyalty. Gorla (2012) scrutinized the relationship between perceived service quality and user satisfaction, revealing this association is influenced by tolerance levels. Collectively, these studies underscore the intricate interplay between residents’ perceptions, their tolerance, and their advocacy for tourism.

Following the steps of above researchers, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H3: The residents’ tolerance for tourism acts as a moderator for the relationship between their perception of the negative impact of tourism and their support.

The above hypotheses are summarized in

Figure 1.

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Sites: Xijiang Miao Village and Zhaoxing Dong Village

To secure the representativeness of the research samples, this study strategically selects two emblematic ethnic minority villages in Guizhou Province as sample sites: Xijiang Miao Village and Zhaoxing Dong Village. Xijiang Miao Village, situated in Leishan County, Guizhou Province, China, stands as the largest Miao village globally, comprising over 1,400 households and 6,000 residents, with 99.5% belonging to the Miao ethnicity1. Referred to as the “Thousand-household Miao Village in Xijiang,” it holds profound cultural significance. On the other hand, Zhaoxing Dong Village, located in Liping County, also within Guizhou, is recognized as the oldest and largest Dong village in China, known as the “First Village in Dong Villages.” This village is home to more than 1,200 households, with over 5,000 residents, 99.5% of whom are Dong people, predominantly sharing the surname Lu2.

The selection of these two villages is underpinned by three primary rationales. Firstly, both Xijiang Miao Village and Zhaoxing Dong Village serve as exemplary instances of ethnic minority communities, showcasing robust ethnic cultural characteristics. Secondly, tourism plays a pivotal role as the primary economic driver in both locales, shaping the livelihoods and economic landscape of the residents significantly. Lastly, aligning with the tourism area life cycle concept, these two ethnic villages represent distinct stages of development, offering a diverse and comprehensive spectrum of tourist destinations for study and analysis.

4.2. Questionnaire and Measurement

The questionnaire consists of four parts, including basic information of residents, residents’ perceived tourism impact, residents’ support for tourism and tolerance for tourism. The basic information of residents mainly includes gender, age, income, education level, whether they are local residents, whether they are engaged in tourism-related work, etc. To ensure the reliability and validity of the scale as much as possible, the measurement of residents’ perceived tourism impact, residents’ support for tourism, and tolerance for tourism are conducted using mature scales from existing literature. Additionally, residents’ tolerance for tourism is adjusted based on existing relevant scales and combined with the research context of ethnic villages.

Residents’ perceived tourism impact. Drawing upon the extant body of research, this work concurs with the discoveries made by Ko and Stewart (2002), Perdue et al (1990), Vargas-Sánchez et al. (2009), Nunkoo and Gursoy(2012), and Qin et al. (2021). These studies posit that residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts can be bifurcated along positive and negative dimensions. As such, our assessment of residents’ perceived tourism impact encompasses both these dimensions. The perceived positive tourism impacts are represented by four items, while the negative aspects are captured by three items. Both categories are grounded in and emerged from the existing scholarly literature.

Residents’ support for tourism. In this research, residents’ support for tourism is interpreted as a form of endorsing behavior, signaling the degree to which residents advocate for tourism development within their own communities. The scale employed to gauge residents’ support for tourism development comprises five distinct items, drawn from the research of McGehee and Andereck (2004), Látková and Vogt (2012), and Qin et al. (2021).

Residents’ tolerance for tourism. As per Qin et al. (2021), residents’ tolerance for tourism is conceived as the spectrum of responses from inhabitants of tourism destinations towards the negative (or adverse) impact elicited by local tourism development. This spectrum ranges from outright rejection to open acceptance. Given the paucity of research on the variable of tolerance within the domain of tourism, the measurement of residents’ tolerance for tourism in this investigation primarily borrows from the work of McLain (1993, 2009) in the field of psychology and the illustrious research conducted by Qin et al. (2021) in the tourism area. In integrating the above-mentioned sources with the present research context, an initial list of five items was garnered. After soliciting the expertise of scholars in tourism research, one item was eliminated, resulting in a four-item measure to assess residents’ tolerance for tourism.

4.3. Sample and Data Collection

This study mainly focuses on residents living in Xijiang Miao Village and Zhaoxing Dong Village as the sample population. Given that the research is conducted in ethnically minority villages, local residents primarily communicate in Miao and Dong languages in their daily lives. To facilitate communication with local residents and maximize their cooperation, the researchers specifically selected four local college students proficient in both Chinese and the local ethnic languages to assist in distributing the survey questionnaires. These students were compensated for their assistance.

To ensure the efficiency of questionnaire distribution, completion, and retrieval, the four college students underwent relevant research training before the formal survey. They were briefed on the questionnaire items to enhance their understanding of the survey’s purpose and content, thus ensuring the quality of questionnaire completion while facilitating the smooth progress of the survey. Additionally, in an effort to further encourage cooperation from local residents, the researchers provided a small token of appreciation to each resident.

The survey spanned from January 26 to March 6, 2021. During this period, a total of 550 questionnaires were disseminated, with 300 distributed in Xijiang Miao Village and 250 in Zhaoxing Dong Village. Of these, 550 questionnaires were collected. After excluding those with missing key information and invalid questionnaires filled out randomly, 275 valid questionnaires were obtained from Xijiang Miao Village and 239 from Zhaoxing Dong Village. Thus, a total of 514 valid questionnaires, with an effective rate of 93.45%, were used for analysis.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Data Analysis

Table 1 presents the demographic profiles of residents in Xijiang Miao and Zhaoxing Dong villages based on a survey of 514 respondents (275 from Xijiang Miao village and 239 from Zhaoxing Dong village). The majority are male (56.2%), with females comprising 41.1%. Most respondents are aged 18 to 45 (69.6%). Educational levels are generally low, with 40.9% having junior high school education or below, 18.5% holding a bachelor’s degree (95 residents), and 1.2% (6 residents) with a master’s degree.

Income levels have shown improvement with tourism development, particularly noticeable in Xijiang Miao Village. The majority of residents now earn over 24,000 RMB annually, with 27.4% earning between 24,001–48,000 RMB and 20.4% between 48,001–72,000 RMB. This marks a significant increase from an average income of 1,700 RMB in 2007 before tourism development commenced in 2008 (T. LI, 2018). Approximately 90.5% of respondents are local residents, with over 80% having resided in the area for more than 10 years. However, only 32.5% are engaged in tourism-related occupations.

In accordance with the recommendations made by Hair et al. (2019). skewness and kurtosis were assessed to ascertain data normality. The absolute values of skewness for all the measurement items in this study oscillated between 0.35 and 1.19, while those of kurtosis varied from 0.12 to 1.53. These values fall within the recommended critical value range by Kline (2015). Hence, it is considered that the data adhere to the normality assumption.

5.2. Common Method Bias

To preclude the possibility of common method bias, the Harman single-factor test was utilized. All survey items were subjected to exploratory factor analysis without rotation, leading to the emergence of four factors that collectively explained 70.925% of the total variance. The principal factor elucidated 39.413% of the total variance, which lies below the critical threshold of 50%. This indicates that the dataset is not significantly marred by common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). By employing the Harman single-factor test and examining the variance explained by each factor, scholars can discern potential instances of common method bias and take appropriate mitigation steps. Consequently, this bolsters the validity and reliability of the study’s findings.

5.3. Reliability and Validity

The assessment of reliability hinges on the calculation of Cronbach’s α coefficient and the Composite Reliability (CR) estimate for each variable. Both Cronbach’s α and CR values ought to reach or exceed the 0.70 threshold (Ribeiro et al., 2017). The item “NEG3” from the perceived negative tourism impact had a Corrected Item-Total Correlation (CITC) value less than the recommended cutoff value of 0.5 proposed by Churchill (1979), and therefore was discarded. As shown in

Table 2, all the Cronbach’s α coefficients and CR scores exceeded the suggested baseline of 0.70. As for validity, it pertains to the structural configuration of variables and measurement items, encapsulating both convergent and discriminant validity. These forms of validity are probed using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) (Asmelash & Kumar, 2019).

The results of confirmatory factor analysis showed that χ2/df=2.576, which falls between 1 and 3. RMSEA=0.055, less than the suggested cut-off value of 0.08. Additionally, GFI=0.953, NFI=0.952, RFI=0.936, TLI=0.960, CFI=0.970, all of which are greater than the critical value of 0.9. PGFI= 0.627, PNFI=0.716, PCFI=0.730, all the values exceed the critical threshold of 0.5, suggesting that the model possesses a commendable degree of fit.

Table 2 in the study corroborates that the factor load for all items surpasses the 0.5 benchmark, and the T-value is in excess of 1.96. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) value for each construct exceeds 0.5, albeit with the exception for the construct of tolerance for tourism, which is slightly under 0.5. This suggests that the scale’s variables possess strong convergent validity, as per Fornell & Larcker (1981). Furthermore,

Table 3 indicates that the square root of the AVE for each construct outperforms its correlation coefficient with other constructs. This certifies commendable discriminant validity for all constructs, aligning with the standards set by Fornell and Larcker (1981).

5.4. Hypothesis Test

5.4.1. Main Effect

The primary effects between perceived tourism impact and residents’ support for tourism were examined via hierarchical regression analysis using SPSS 23.0. Initial evaluation was undertaken to discern the influence of control variables such as gender, age, education, and annual income. Subsequently, these control variables together with the independent variables (perceived positive tourism impact and perceived negative tourism impact) were incorporated into the regression equation. The results have been delineated in

Table 4.

Model 1 investigates the influence of control variables, encompassing gender, age, education, and income. Cumulatively, these four variables accounted for 9% of the variance in tourism support (R2=0.09, F=1.068, P>0.05), thereby suggesting that demographic factors did not significantly sway tourism support. In Model 2, the twin independent variables of perceived positive tourism impact and perceived negative tourism impact were introduced. The model’s ability to explain the variance improved to 19% (R2=0.190, F=17.454, P<0.05). The rise in explained variance from Model 1 to Model 2 was considerably noticeable (ΔR2 = 0.181, P<0.05). Essentially, upon controlling for demographic variables, the independent variables of perceived positive tourism impact and perceived negative tourism impact notably augmented the explained variance of tourism support by 18.1%. The outcome demonstrated that both perceived positive tourism impact (β=0.336, P<0.05) and perceived negative tourism impact (β=-0.129, P<0.05) could efficaciously predict tourism support. Hence, both hypotheses H1a and H1b are substantiated.

5.4.2. Mediating and Moderating Effects

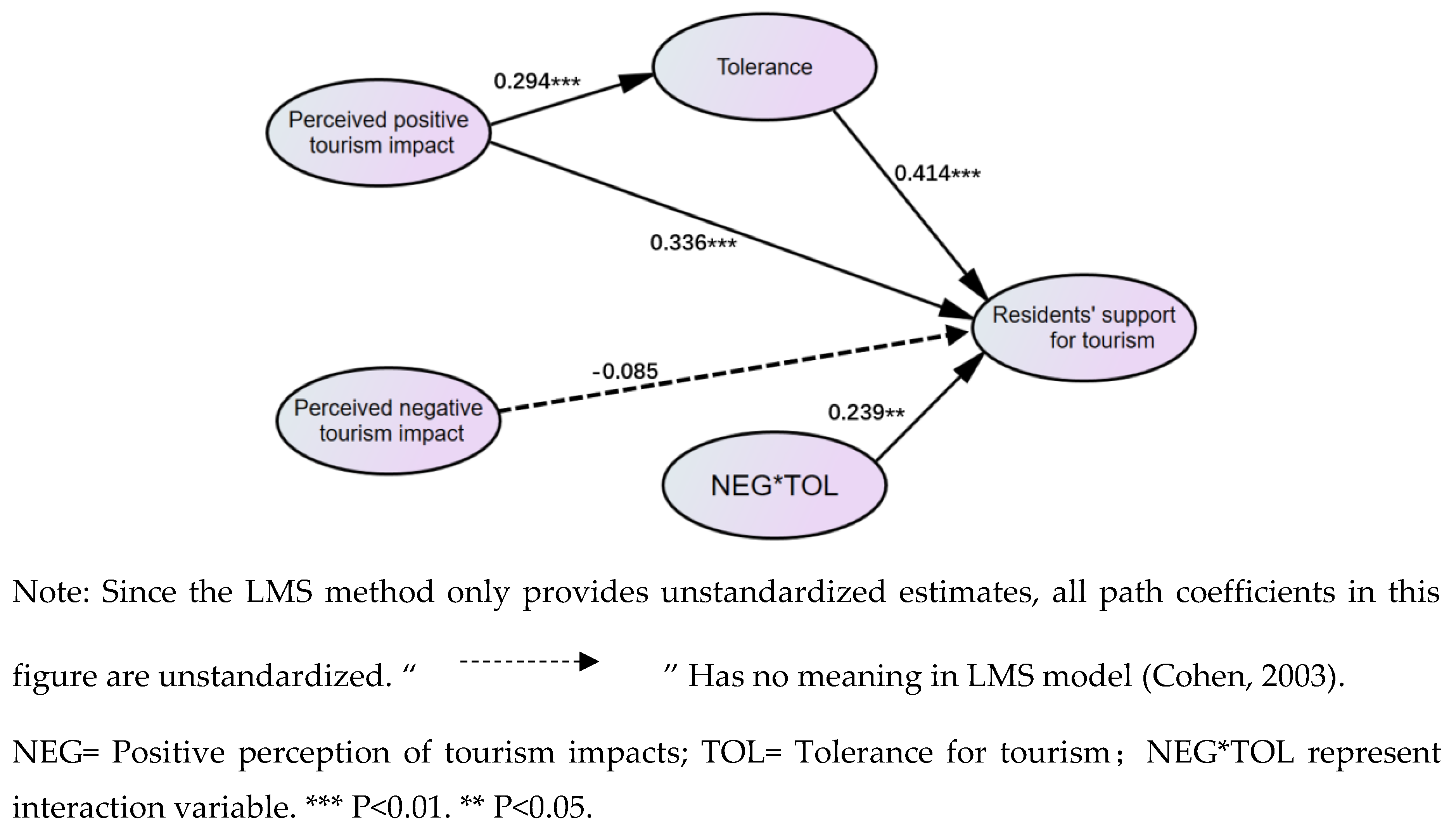

The mediating and moderating effects of tolerance for tourism were further examined using AMOS 23 statistical analysis software. To test the hypotheses, the Latent Moderated Structural Equations (LMS) method, utilizing a maximum likelihood estimation approach, was implemented. The resulting outcomes are depicted in

Figure 2. Indicative of solid model fitness, the primary fit indices of the model were found to be satisfactory. (χ2/df = 1.830, GFI=0.966, NFI=0.964, IFI=9841, RFI=0.951, TLI=0.977, CFI=0.983, PGFI= 0.620, PNFI=0.707, PCFI=0.721, and RMSEA=0.040).

Mediating effect of tolerance for tourism. The details of the LMS test are illustrated in

Figure 2, The variable of positive perception of tourism impact significantly and positively influences tolerance for tourism (β=0.294, t=4.998, P<0.05), supporting H2a. Additionally, tolerance for tourism significantly and positively affects support for tourism (β=0.414, t=7.680, P<0.05), thus supporting H2b. The present study employed the bootstrap resampling method with 5000 iterations to scrutinize the mediating role of residents’ tolerance for tourism in the relationship between their perceived positive tourism impact and their support for tourism. More precisely, it was utilized to estimate both the mediation effect value of tolerance for tourism as well as its confidence intervals in the AMOS 23 statistical software application. The findings, as outlined in

Table 5, are in line with the standards established by Baron and Kenny (1986). The results substantiate that residents’ tolerance for tourism operates as a significant mediator in the relationship between their perception of positive tourism impact and their support for tourism (β=0.122, SE=0.032, P<0.05), thereby confirming hypothesis H2c. Furthermore, the findings suggest a significant direct impact of residents perceived positive tourism impact on support for tourism (β=0.336, SE=0.107, P<0.05). This implies that tolerance for tourism serves as a partial mediator in this relationship.

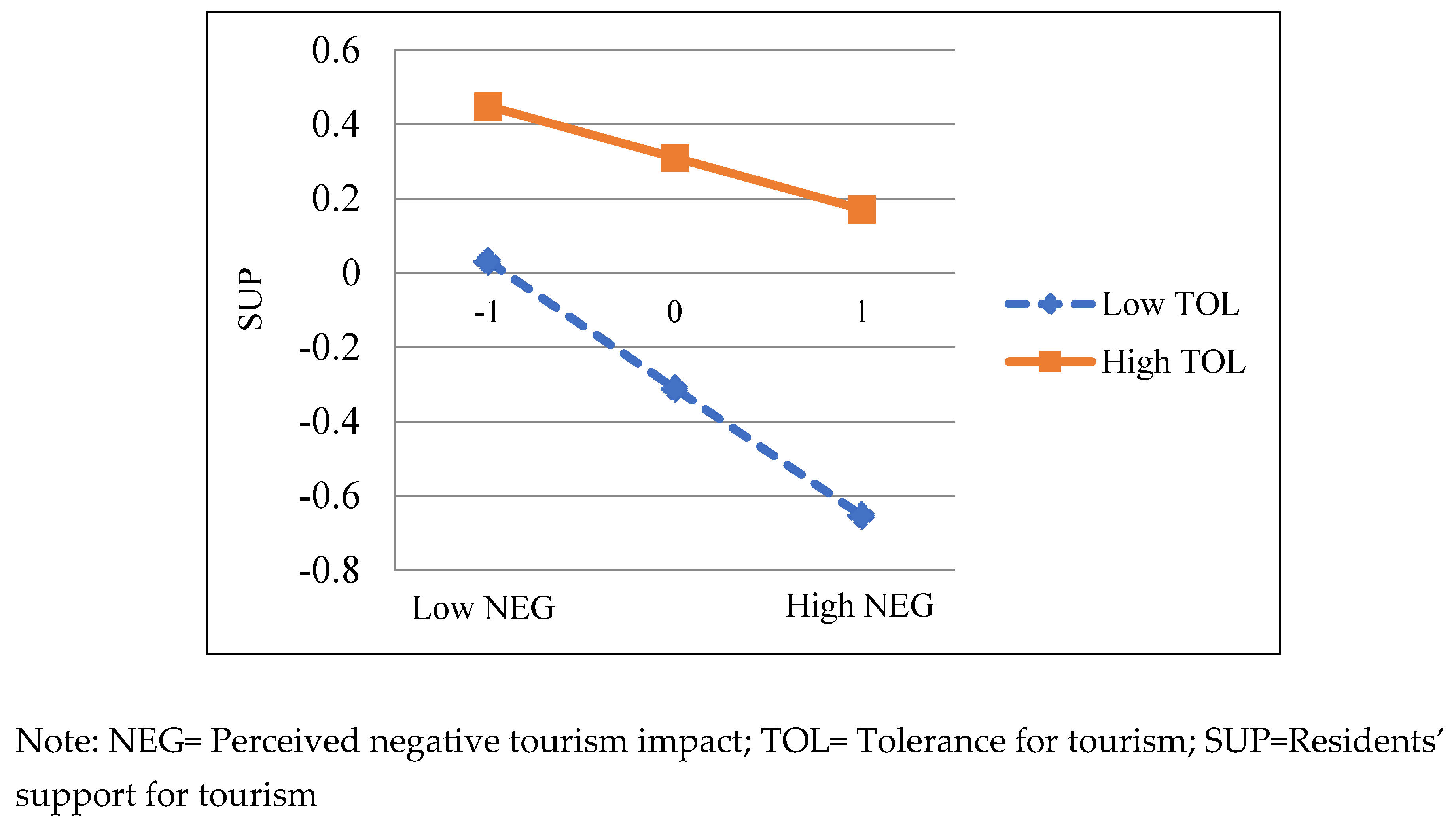

Moderating effect of tolerance for tourism. According to the results of LMS test, a significant positive effect is demonstrated by the interaction variable of NEG*TOL on support for tourism (β=0.239, t=2.549, P<0.05), thereby supporting H3. This result indicates that a significant moderation occurs in the relationship between the perceived negative tourism impact (NEG) and support for tourism (SUP) by the tolerance for tourism (TOL). To probe further into the moderating effect of tolerance for tourism, the researchers employed the SPSS PROCESS macro model 1 (Hayes, 2019) to test for the role of tolerance for tourism as a moderating variable. Following Dawson (2014) ’s recommendation, a simple slope analysis was conducted by dividing the moderating variable into low and high groups using the mean ±1 standard deviation (SD). The specifics of this simple slope test are laid out in

Table 6. The findings suggest that at low levels of tolerance, perceived negative tourism significantly bears a negative impact on tourism support (β=-0.340, t=-6.794, P<0.05, CI= [-0.439, -0.242]). Conversely, at the high tolerance level, perceived negative tourism also has a significant negative impact on tourism support (β=-0.141, t=-2.728, P<0.05, CI= [-0.242, -0.039]).

The moderation effect is also depicted in

Figure 3. Notably, when tolerance for tourism runs high, it significantly softens the negative interplay between the perceived negative tourism impact and residents’ support for tourism. Conversely, when tolerance for tourism is low, a considerable negative correlation manifests between perceived negative tourism impact and residents’ support for tourism. This suggests the adverse influence of perceived tourism impact on support for tourism progressively lessens as the tolerance for tourism escalates.

6. Conclusion and Discussion

Drawing upon the social exchange theory and the zone of tolerance theory from service marketing, this study enriches the classical paradigm of “residents’ perceived tourism impact—support for tourism” by incorporating the concept of tolerance for tourism from a process-oriented viewpoint. It suggests that tolerance for tourism serves as a conduit in shaping residents’ endorsement of tourism in ethnic villages, emphasizing a process-oriented perspective. The study samples residents residing in two representative ethnic minority villages at various stages of tourism lifecycle development, validating the research model and hypotheses. Subsequently, three pivotal research conclusions and discussions emerge from this analysis.

Firstly, grounded in social exchange theory, the equilibrium between benefits and costs directly influences an individual’s engagement in subsequent exchange behavior. This study reaffirms the positive association between residents’ perceived tourism impact and their support for tourism, corroborating findings from numerous prior studies (Çelik & Rasoolimanesh, 2023; Nugroho & Numata, 2022; Qi et al., 2023). These investigations indicate that residents perceived positive tourism impact is foundational to endorsing tourism development, underscoring a direct correlation between the two constructs.

Secondly, the study reaffirms the complex relationship between residents’ perceived negative tourism impact and their support for tourism. The findings indicate a significant inverse correlation between residents’ perceived negative tourism impact and their support for tourism. This insight aligns with conclusions drawn by an extensive body of previous research (Liu et al., 2023; Nugroho & Numata, 2022). However, the conclusion is continuously conflicting some recent researches (Qi et al., 2023; Viana-Lora et al., 2023). Consequently, this study further elucidates the intricate relationship between perceived negative tourism impact and residents’ support for tourism, within the purview of social exchange theory. It paves the way for a more in-depth exploration of the intermediary mechanisms that govern this relationship.

Thirdly, in response to the contradicting findings concerning the relationship between perceived negative tourism impact and support for tourism in existing research, and in concurrence with the sentiments expressed by various researchers (Erul et al., 2020; Qin et al., 2021), this study amalgamates the social exchange theory with the zone of tolerance theory. The aim is to dissect the process that forms resident support for tourism. It incorporates residents’ tolerance for tourism into the classic model of “perceived tourism impact – support for tourism” to provide deeper insights into the mechanisms behind supporting tourism. The results suggest that residents’ tolerance for tourism plays a crucial role in shaping their support for tourism. On one hand, tolerance for tourism reveals a partial mediating effect in the relationship between residents’ perceived positive tourism impact and their support for tourism. The findings suggest that as residents reap benefits from tourism development, their tolerance for tourism escalates, subsequently reinforcing their support for additional tourism initiatives. This result is in line with the research conducted by Qi et al. (2016) and Qi et al. (2023). On the other hand, tolerance for tourism is found to exercise a significant moderating effect on the link between residents’ perceived negative tourism impact and their support for tourism. The data infers that tolerance for tourism softens the damaging impact of residents’ perceived negative tourism repercussions, thereby fortifying their support for tourism. This inference resonates with the conclusions arrived at by Qin et al. (2021). Meanwhile, it provides a possible idea to help us explain why some of the existing studies on residents’ tourism support have concluded that negative perception is significantly correlated with tourism support(Ng & Feng, 2020; Nugroho & Numata, 2022), while others have not(Çelik & Rasoolimanesh, 2023; Qi et al., 2023).

These findings highlight the limitations of the social exchange theory, a widely employed theoretical framework in prior models investigating the relationship between residents’ perceived tourism impacts and their ensuing support for tourism. While the positive correlation between a favorable perception of tourism impacts and support for tourism is largely agreed upon, the controversy surrounding the linkage between perceived negative tourism impact and support for tourism remains unaddressed (Ribeiro et al., 2017). Consequently, this study introduces the concept of tolerance for tourism into the research model, drawing from the zone of tolerance theory, to elucidate the process of shaping resident support for tourism. By enhancing the research paradigm from residents’ “perceived tourism impact -- support for tourism,” commonly employed in previous studies, this study demonstrates the significant influence of residents’ tolerance for tourism on the relationship between the two constructs.

7. Implications and Limitations

7.1. Theoretical Implication

This study makes significant contributions to the understanding of residents’ support for tourism in several key aspects.

Enhancing the Classic Research Paradigm. By introducing a conceptual model that incorporates tolerance for tourism, this study advances the classic paradigm of “perceived tourism impact—support for tourism.” This model, grounded in both social exchange theory and the zone of tolerance theory, addresses the limitations of existing research paradigms that rely solely on residents’ perceived tourism impact. By integrating tolerance for tourism, it adds a new dimension, offering a more comprehensive framework to understand the formation of resident support for tourism.

Empirical Evidence on the Role of Tolerance. This study reaffirms, in line with the social exchange theory, the positive relationship between residents’ perceptions of positive tourism impact and their resultant support for tourism, as well as the negative relationship between perceived tourism impact and support for tourism. Concurrently though, it tackles the controversial and occasionally inconsistent negative correlation observed in previous studies between the residents’ perceptions of negative tourism consequences and their support for tourism (Nugroho & Numata, 2022; Qin et al., 2021). By introducing tolerance from service marketing as a moderating factor, the study demonstrates that residents’ tolerance significantly influences this relationship. The empirical evidence underscores that tolerance for tourism not only tempers the influence of perceived negative impact, but also partially intermediates the relationship between perceived positive impact and support for tourism. This infers that residents’ tolerance for tourism could provide insight into why some destinations maintain ongoing support in spite of the residents’ explicit cognizance of adverse tourism impacts.

Integrating Theories for a Holistic Understanding. The study goes beyond the traditional application of social exchange theory in explaining residents’ support for tourism. Recognizing the limitations and critiques of solely relying on social exchange theory, particularly in light of controversial empirical findings, the study integrates it with the zone of tolerance theory. This integration provides a more nuanced understanding of how residents’ support for tourism is shaped. It posits that residents’ support is influenced not only by their perception of tourism impacts but also by their tolerance for tourism. By incorporating the zone of tolerance theory from service marketing, the study explores the mediating and moderating effects of residents’ tolerance, offering an effective approach to comprehending the complex process of shaping resident support for tourism in ethnic villages.

7.2. Management Implication

This study offers valuable insights with significant implications for tourism management departments and destination area managers, especially those overseeing ethnic villages.

Benefits and Costs are Crucial for Residents’ Support. The study accentuates the profound influence of residents’ perceptions of positive/negative tourism impacts on their endorsement for local tourism development. As such, for the sake of securing active backing from local residents, tourism development bodies and local management agencies in ethnic villages ought to prioritize strategies aimed at augmenting the residents’ income derived from tourism. This strategy can help residents secure a steady income from tourism activities, thereby influencing their inclination to support local tourism development initiatives. Furthermore, the genuine participation and involvement of residents are crucial in attracting tourists, leading to a mutually beneficial relationship among residents, tourism developers, local managers, and tourists. Ensuring ’common prosperity’ among stakeholders is essential for fostering sustainable tourism development in ethnic villages. Therefore, tourism management agencies and developers should implement effective measures to augment residents’ income, such as creating more local employment opportunities, which can enhance their quality of life and bolster their support for tourism endeavors.

The Easing effect of Tolerance. It becomes crucial to exploit the buffering effect of residents’ tolerance for tourism on perceived negative tourism impact. This study underscores the considerable role of residents’ tolerance for tourism as a moderator, notably tempering the unfavorable relationship between perceived negative tourism impacts and the residents’ support for tourism. This finding elucidates why residents in certain tourist destinations continue to endorse local tourism development despite perceiving substantial negative impacts. The pivotal role of residents’ tolerance for tourism is evident, as higher tolerance substantially attenuates the link between perceived negative tourism impact and support for tourism. Conversely, lower tolerance exacerbates this negative relationship. Given that tourism development in ethnic villages presents both opportunities and challenges, destination management practices should aim to maximize benefits while minimizing drawbacks. The study suggests that tourism management departments and managers must acknowledge the potential adverse impacts of tourism development and proactively address them. It is vital to focus attentively on residents with low tolerance for tourism, given their heightened susceptibility to negative impacts, and potential for a rapid withdrawal of support. By understanding and managing the role of residents’ tolerance in the dynamics between perceived negative tourism effects and support for tourism, contentious issues can be lessened, thereby bolstering overall resident support for tourism. This, in turn, advances sustainable development within the destination.

7.3. Limitation and Future Research

By integrating social exchange theory and the zone of tolerance theory, this study delved into the influence mechanism of tourism support among minority village residents. While it makes significant theoretical contributions and managerial implications, there are still certain limitations due to objective constraints, which also provide direction for future research in this area.

Firstly, this study only considers residents’ perceived tourism impact in terms of two dimensions: positive and negative. Existing research suggests that these dimensions can be further subdivided based on specific aspects, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of residents’ perceived tourism impacts. Hence, future studies should adopt a more exhaustive classification approach.

Secondly, due to the limited literature on measuring tolerance for tourism in the context of tourism research, this study adapted the concept and measurement of tolerance from the field of psychology, integrating it with discussions of tolerance for tourism within tourism research. While this approach demonstrated reliability and validity in this study, its generalizability warrants further examination in future research.

Thirdly, in terms of research design, this study utilized cross-sectional data for statistical analysis to test the theoretical model and hypothesis relationships, making it challenging to conclusively establish causal relationships between variables. Therefore, future studies, if feasible, could explore the relevant research conclusions further through longitudinal study designs.

References

- Ap, J. (1992). Residents’ Perceptions of Tourism Impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 19, 665-690. [CrossRef]

- Ap, J., & Crompton, J. L. (1993). Residents’ Strategies for Responding to Tourism Impacts. Journal of Travel Research, 32(1), 47-50. [CrossRef]

- Asmelash, A. G., & Kumar, S. (2019). Assessing progress of tourism sustainability: Developing and validating sustainability indicators. Tourism Management, 71, 67-83. [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173-1182. [CrossRef]

- Çelik, S., & Rasoolimanesh, S. M. (2023). Residents’ attitudes towards tourism, cost–benefit attitudes, and support for tourism: A pre-development perspective. [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G. A. (1979). A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64-73. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J. F. (2014). Moderation in management research: What,Why, When, and How. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29(1), 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Dyer, P., Gursoy, D., Sharma, B., & Carter, J. (2007). Structural modeling of resident perceptions of tourism and associated development on the Sunshine Coast, Australia. Tourism Management, 28(2), 409-422. [CrossRef]

- Erul, E., Woosnam, K. M., & McIntosh, W. A. (2020). Considering emotional solidarity and the theory of planned behavior in explaining behavioral intentions to support tourism development. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(8), 1158-1173. [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research 18, 39-50. [CrossRef]

- Ganji, S. F. G., Johnson, L. W., & Sadeghian, S. (2021). The effect of place image and place attachment on residents perceived value and support for tourism development. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(9), 1304-1318. [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.-k. (2005). On the Theory of Coleman’s Social Capital. Journal of Beihua University (Social Sciences), 6, 13-18.

- Gautam, V. (2023). Why local residents support sustainable tourism development? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(3), 877-893. [CrossRef]

- Gjerald, O. (2005). Sociocultural Impacts of Tourism: A Case Study from Norway. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 3(1), 36-58. [CrossRef]

- Gong, J., Shapovalova, A., Lan, W., & Knight, D. W. (2023). Resident support in China’s new national parks: an extension of the Prism of Sustainability. Current Issues in Tourism, 26(11), 1731-1747. [CrossRef]

- Gorla, N. (2012). Information Systems Service Quality, Zone of Tolerance, and User Satisfaction. Journal of Organizational and End User Computing, 24(2), 50-73. [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D., Ouyang, Z., Nunkoo, R., & Wei, W. (2019). Residents’ impact perceptions of and attitudes towards tourism development: a meta-analysis. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 28(3), 306-333. [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D., Yolal, M., Ribeiro, M. A., & Panosso Netto, A. (2017). Impact of Trust on Local Residents’ Mega-Event Perceptions and Their Support. Journal of Travel Research, 56(3), 393-406. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate Data Analysis (Eighth Edition ed.). Cengage Learning, EMEA.

- Hasani, A., Moghavvemi, S., & Hamzah, A. (2016). The Impact of Emotional Solidarity on Residents’ Attitude and Tourism Development. PLoS One, 11(6), 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Hateftabar, F., & Rasoolimanesh, S. M. (2023). Crisis-driven shifts in resident pro-tourism behaviour. Current Issues in Tourism. [CrossRef]

- Haukeland, J. V., Veisten, K., Grue, B., & Vistad, O. I. (2013). Visitors’ acceptance of negative ecological impacts in national parks comparing the explanatory power of psychographic scales in a Norwegian mountain setting. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(2), 291-313. [CrossRef]

- Homans, G. C. (1961). Social behavior: Its elementary forms. Brace & World.

- Jurowski, C., Uysal, M., & Williams, D. R. (1997). A Theoretical Analysis of Host Community Resident Reactions to Tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 36(2), 3-11. [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford.

- Ko, D.-W., & Stewart, W. P. (2002). A structural equation model of residents’ attitudes for tourism development. Tourism Management 23, 521–530. [CrossRef]

- Látková, P., & Vogt, C. A. (2012). Residents’ Attitudes toward Existing and Future Tourism Development in Rural Communities. Journal of Travel Research, 51(1), 50-67. [CrossRef]

- LI, T. (2018). Report on Tourism Development of China’s Xijiao Miao Village (T.-y. Li, Ed.). Sicial sciences academic press (China).

- Li, X., Boley, B. B., & Yang, F. X. (2023). Resident empowerment and support for gaming tourism: comparisons of resident attitudes pre-and amid-Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 47(8), 1503-1529. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., & Wan, Y. K. P. (2016). Residents’ support for festivals: integration of emotional solidarity. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(4), 517-535. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z., Luo, H., & Bao, J. (2021). A longitudinal study of residents’ attitudes toward tourism development. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(23), 3309-3323. [CrossRef]

- Lischka, S. A., Riley, S. J., & Rudolph, B. A. (2008). Effects of impact perception on acceptance capacity for white-tailed deer. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 72(2), 502-509. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., An, K., & Jang, S. C. S. (2023). Behaviours not set in stone do residents still adopt pro-tourism behaviours when tourists behave in uncivilized ways. Current Issues in Tourism. [CrossRef]

- Maksim Godovykh, Hacikara, A., Baker, C., Fyall, A., & Pizam, A. (2023). Measuring the perceived impacts of tourism a scale development study. Current Issues in Tourism. [CrossRef]

- Mansfeld, Y., & Ginosar, O. (1994). Determinants of Locals’ Perceptions and Attitudes Towards Tourism Development in their Locality. Geoforum, 25(2), 227-248. [CrossRef]

- McLain, D. L. (1993). The Mstat-I: A New Measure of an Individual’S Tolerance for Ambiguity. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 53(1), 183-189. [CrossRef]

- McLain, D. L. (2009). Evidence of the properties of an ambiguity tolerance measure: the Multiple Stimulus Types Ambiguity Tolerance Scale-II (MSTAT-II). Psychol Rep, 105(3 Pt 1), 975-988. [CrossRef]

- Muldoon, R., Borgida, M., & Cuffaro, M. (2011). The conditions of tolerance. Politics, Philosophy & Economics, 11(3), 322-344. [CrossRef]

- Munanura, I. E., & Kline, J. D. (2023). Residents’ support for tourism: The role of tourism impact attitudes, forest value orientations, and quality of life in Oregon, United States. Tourism Planning & Development, 20(4), 566-582. [CrossRef]

- Munanura, I. E., Needham, M. D., Lindberg, K., Kooistra, C., & Ghahramani, L. (2023). Support for tourism: The roles of attitudes, subjective wellbeing, and emotional solidarity. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(2), 581-596. [CrossRef]

- Ng, S. L., & Feng, X. (2020). Residents’ sense of place, involvement, attitude, and support for tourism: a case study of Daming Palace, a Cultural World Heritage Site. Asian Geographer, 37(2), 189-207. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, N., & Wilson, E. (2012). From Invisible to Indigenous-Driven A Critical Typology of Research in Indigenous Tourism. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, Special Issue, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, P., & Numata, S. (2022). Resident support of community-based tourism development: Evidence from Gunung Ciremai National Park, Indonesia. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(11), 2510-2525. [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R., & Gursoy, D. (2012). Residents’ support for tourism:An Identity Perspective. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(1), 243-268. [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R., & Gursoy, D. (2016). Political trust and residents’ support for alternative and mass tourism: an improved structural model. Tourism Geographies, 19(3), 318-339. [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A., Berry, L. L., & Zeithaml, V. A. (1991). Understanding Customer Expectations of Service. Sloan Management Review, 32(3), 39-48.

- Perdue, R. R., Long, P. T., & Allen, L. (1990). Resident support for tourism development Annalsof Tourism Research, 17, 586-599. [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol, 88(5), 879-903. [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G., Hosany, S., Nunkoo, R., & Alders, T. (2013). London residents’ support for the 2012 Olympic Games: The mediating effect of overall attitude. Tourism Management, 36, 629-640. [CrossRef]

- Qi, R., So, K. K. F., Cardenas, D., Hudsonn, S., & Meng, F. (2016). The Mediating Effects of Tolerance on Residents_ Support Toward Tourism Events. Travel and Tourism Research Association: Advancing Tourism Research Globally.

- Qi, R., So, K. K. F., cárdenas, d. a., & hudson, s. (2023). The missing link in resident support for tourism events: the role of tolerance. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 47(2), 422-452. [CrossRef]

- Qin, X., Shen, H., Ye, S., & Zhou, L. (2021). Revisiting residents’ support for tourism development: The role of tolerance. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 47, 114-123. [CrossRef]

- Qiu Zhang, H., Fan, D. X. F., Tse, T. S. M., & King, B. (2017). Creating a scale for assessing socially sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(1), 61-78. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M. A., Pinto, P., Silva, J. A., & Woosnam, K. M. (2017). Residents’ attitudes and the adoption of pro-tourism behaviours: The case of developing island countries. Tourism Management, 61, 523-537. [CrossRef]

- Riorini, S. V., & Barusman, A. R. P. (2016). Zone-of-tolerance moderates satisfaction, customer trust and inertia - Customer loyalty. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309060830_Zone-of-tolerance_moderates_satisfaction_customer_trust_and_inertia_-_Customer_loyalty.

- Santos, E. R. M. d., Pereira, L. N., Pinto, P., & Boley, B. B. (2024). Imperialism, empowerment, and support for sustainable tourism Can residents become empowered through an imperialistic tourism development model. Tourism Management Perspectives, 53, 101270. [CrossRef]

- Smith, V. (1977). Hosts and guests: The anthropology of tourism. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Stewart, E. J., Kirby, V. G., & Steel, G. D. (2006). Perceptions of Antarctic tourism: A question of tolerance. Landscape Research, 31(3), 193-214. [CrossRef]

- Tam, P. S., Lei, C. K., & Zhai, T. (2023). Investigating the bidirectionality of the relationship between residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts and subjective wellbeing on support for tourism development. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(8), 852-1868. [CrossRef]

- Teng, H.-Y., & Chang, S.-T. (2020). Resident perceptions and support before and after the 2018 Taichung international Flora exposition. Sue-Ting Chang. [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Sánchez, A., Plaza-Mejía, M. d. l. Á., & Porras-Bueno, N. (2009). Understanding Residents’ Attitudes toward the Development of Industrial Tourism in a Former Mining Community. Journal of Travel Research, 47(3), 373-387. [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Sanchez, A., Valle, P. O. d., Mendes, J. d. C., & Silva, J. A. (2015). Residents’ attitude and level of destination development: An international comparison. Tourism Management, 48, 199-210. [CrossRef]

- Viana-Lora, A., Orgaz-Agüera, F., AguilarRivero, M., & Moral-Cuadra, S. (2023). Does the education level of residents influence the support for sustainable tourism. Current Issues in Tourism. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Shen, H., Ye, S., & zhou, L. (2020). Being rational and emotional: An integrated model of residents’ support of ethnic tourism development. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 44, 112-121. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Zhao, X., Fan, L., zhou, L., & Ye, S. (2024). Revisiting residents’ support through collective rationality. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 58, 298-308. [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K. M., & Aleshinloye, K. D. (2015). Residents’ Emotional Solidarity with Tourists: Explaining Perceived Impacts of a Cultural Heritage Festival. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 42(4), 587-605. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L., & Wall, G. (2009). Ethnic tourism: A framework and an application. Tourism Management, 30, 559–570. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Wang, S., Cai, Y., & Zhou, X. (2022). How and why does place identity affect residents’ spontaneous culture conservation in ethnic tourism community? A value co-creation perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(6), 1344-1363 . [CrossRef]

- Zajac, R. M., Bruskotter, J. T., Wilson, R. S., & Prange, S. (2012). Learning to Live With Black Bears: A Psychological Model of Acceptance. The Journal of Wildlife Management. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Xu, H.-g., & Xing, W. (2017). The host–guest interactions in ethnic tourism, Lijiang, China. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(7), 724-739. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).