1. Introduction

Global travel has nearly reached its pre-pandemic level. Over 300 million individuals travelled overseas in the first quarter of 2025, according to UN Tourism projections, which is roughly 5 % more than in the same period in 2024 [

1]. However, the numerical rebound has revived familiar urban strains: crowded streets, over-burdened public services, housing shortages, cultural displacement and harm to local ecosystems.

Europe illustrates both the scale and the uneven geography of recovery. Roughly 756 million international arrivals were recorded across the continent in 2024 [

2], topping the previous record. France (100 million), Spain (85 million) and Italy (57 million) still receive the most visitors, yet the sharpest growth is in Southern and Southeastern Europe, Türkiye’s arrivals having risen 247 % between 2020 and 2023 to reach 55 million, while Greece logged a 344 % leap from 7.4 million to 32.7 million [

2]. Headlines reflect the tension: Venice has made its €5 day-ticket permanent [

3]; Barcelona residents have protested crowds with water pistols; Athens now limits the Acropolis to 20 000 visitors a day.

Istanbul and Athens have become new focal points of overtourism in the eastern Mediterranean. Both cities are seeing crowded buses and metros, rents driven up by short-term lets and faster wear on historic sites. Rapid growth risks outpacing the very systems that keep daily life running. Overtourism, therefore, is now viewed as a threat to economic stability, social cohesion, environmental quality, governance capacity and technological infrastructure [

4,

5]. Resident pushbacks in Venice, Barcelona and Amsterdam have already spurred calls for urgent action [

6].

Since the Brundtland Report (1987), sustainability in tourism has usually been framed around three pillars—economic, socio-cultural and environmental—popularly known as the 3P framework (Profit, People, Planet) [

7,

8]. Recent research argues that political and technological factors must be added to build a fuller picture [

9,

10]. Empirical studies that put residents at the center, especially on these two newer dimensions, remain scarce [

9,

11], and the political and technological issues have yet to be fully built into holistic models [

5].

These discussions align with the broader framework of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [

12,

13]. Tourism already appears in SDG 8.9 (sustainable jobs and local culture) and SDG 12.b (impact tracking), yet the five-dimensional model used here connects with other goals as well: economic (SDG 8), environmental (SDGs 12 and 13), socio-cultural (SDG 11), political (SDG 16) and technological (SDG 9). Looking at how people in Athens and Istanbul view these dimensions offers practical city-level insights to close local SDG gaps before 2030.

Among tourism’s four main stakeholder groups—tourists, businesses, public authorities and residents—residents feel visitor pressure most directly. Earlier work has stressed tourist dissatisfaction with crowding, [

14] firms’ trade-offs between short-term profit and long-term viability [

10] and government regulation [

6]. Residents’ own sustainability perceptions, encompassing economic, socio-cultural, environmental, political and technological facets, are still under-explored.

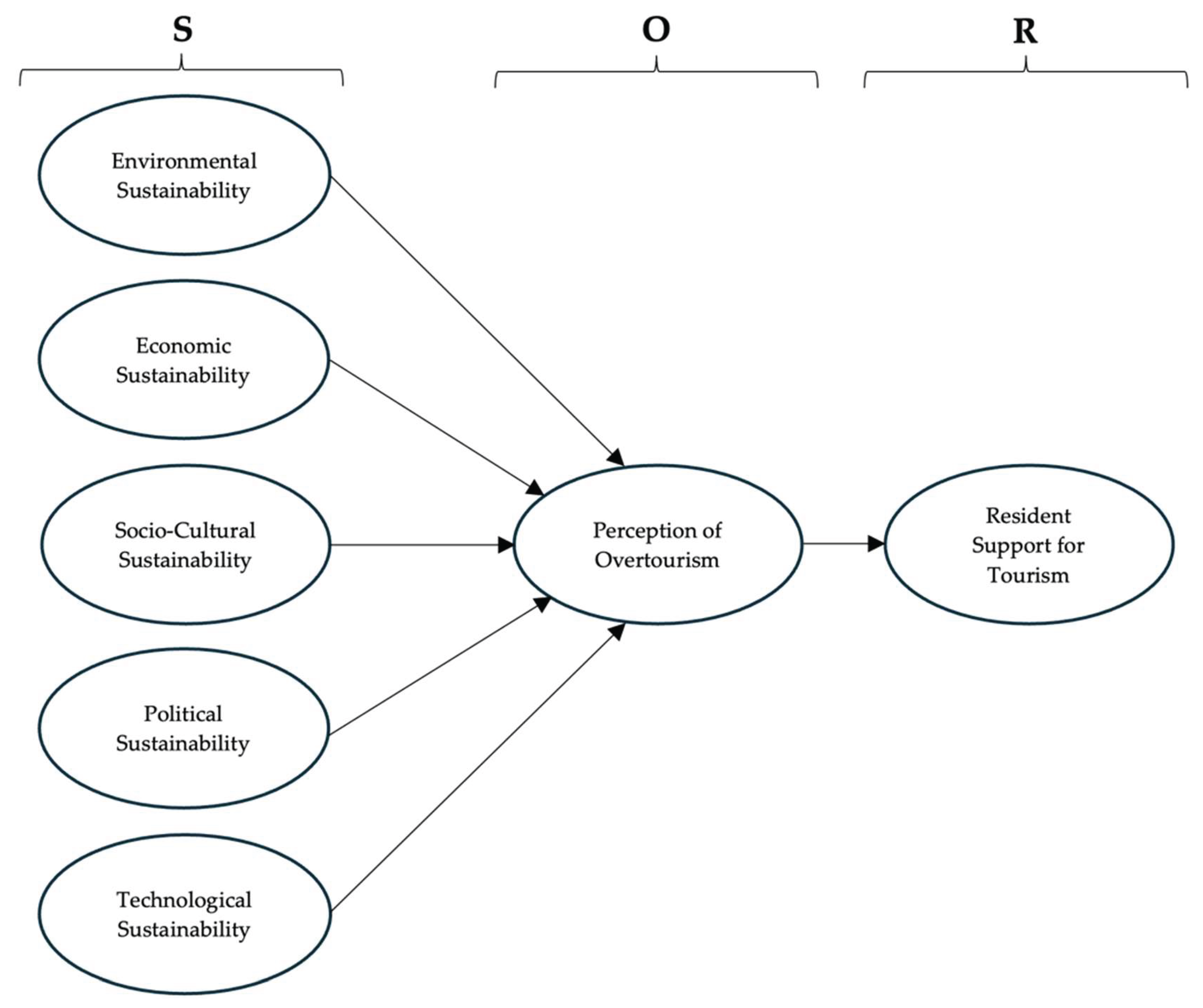

This research therefore sets three goals: to examine how overtourism shapes resident perceptions in all five sustainability dimensions; to test how these perceptions relate to Resident Support for Tourism (RST); and to compare Istanbul and Athens to explain how their differing cultural and governance contexts influence the perception–support link. The study applies the well-known Stimulus Organism Response (S-O-R) model: five external stimuli—environmental, economic, socio-cultural, political and technological—are expected to shape the organism, defined here as residents’ perception of overtourism, which in turn drives the response, namely RST.

By extending sustainability analysis beyond the classic 3P framework and placing residents at the center, this research seeks to give a clearer, context-sensitive view of overtourism in two fast-changing Mediterranean cities. The findings aim to guide more balanced policies that safeguard urban life while preserving tourism’s economic benefits.

2. Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Understanding Overtourism

Overtourism does not present itself in a uniform way [

15]. Its effects often depend on where it occurs and under what conditions. In some cities, it appears in the form of overcrowded streets or environmental degradation. In others, it brings more subtle changes—such as shifts in local identity or disruptions to everyday routines. The term overtourism has only recently gained clearer academic definition. A bibliometric review indicates that the phenomenon is highly place-specific, influenced by factors such as infrastructure, governance, and social context [

16].

Still, the term is not without problems. One study argues that using the term “overtourism” too loosely may obscure underlying structural issues such as gentrification, rising housing costs, and inadequate public services. Based on comparative research in thirteen European cities, the authors suggest using the term "visitor pressure" to more accurately describe the strain tourism places on shared urban resources. Their analysis also highlights how simplified narratives around overtourism can hinder the development of effective policy responses [

17].

Importantly, overtourism is not just about the number of tourists. The issue is often identified when there is a mismatch between tourist flows and a destination’s ecological, social, or perceptual capacity [

18,

19]. Disruptions occur when tourism begins to interfere with daily life or weakens local attachment to place. A range of case studies supports this interpretation. In Bali, it has been reported that perceived crowding often occurs before actual physical saturation is reached [

20]. Their research shows that psychological thresholds may serve as early indicators of overtourism. Together, these findings point to the need for metrics that incorporate perception and lived experience, alongside physical data.

Wider systemic factors have amplified these trends [

21,

22]. The proliferation of budget airlines, short-term rental platforms, and algorithmic promotion systems has intensified the flow of visitors. In a study, it is argued that urban landscapes have been transformed by such mechanisms—blurring distinctions between resident and tourist, public and commercial, and domestic and commodified [

23] Even smaller towns with heritage protections are not exempt from these pressures. Visitor-to-resident ratios exceeding 1:700 have been documented in Èze, Kotor, and Dubrovnik [

24]. In such cases, preserving visual authenticity does not necessarily ensure the sustainability of community life, as infrastructure strain, demographic shifts, and spatial fragmentation often follow.

Policy responses have been limited in scope and effectiveness. This has been attributed to fragmented governance, dependence on tourism-based revenue, and political inertia [

25]. For example, in cities like Venice and Dubrovnik, cruise ship saturation and housing commodification have displaced residents and degraded urban environments [

26].

This pattern is not confined to Europe. In Sri Lanka, projections suggest that popular sites such as Yala National Park and Sigiriya may face ecological collapse by 2027 if no regulatory action is taken [

27]. Similarly, a 70% increase in post-pandemic tourism—largely driven by social media—has been observed in Banyumas Regency, Indonesia, leading to infrastructural and ecological strain within a short period [

28].

Quantitative research supports the persistence of overtourism. A longitudinal study of 28 European cities between 2014 and 2023 identified recurring stress markers such as high rates of overnight stays and increased inbound air traffic [

29]. The findings confirm that overtourism dynamics quickly reemerged following the COVID-19 disruption, highlighting the structural and self-reinforcing nature of the phenomenon.

2.2. Sustainability in Tourism

The conventional sustainability framework in tourism research is structured around three dimensions: economic, socio-cultural, and environmental. While this 3D model has been widely adopted as a baseline, recent studies increasingly argue that it no longer captures the complexity of modern tourism systems. In particular, technological and political factors have emerged as critical influences on tourism dynamics, prompting calls to expand the framework to a five-dimensional (5D) model.

Recent contributions emphasize the role of technological tools in enhancing tourism governance. For instance, Wijayawardhana [

27] demonstrates that machine learning techniques can anticipate high-pressure zones in tourist destinations, providing an opportunity for proactive intervention. Similarly, Antonio and Alamsyah [

20] integrate sentiment analysis with spatial modeling to support decentralized, real-time responses to tourism congestion. These approaches highlight how digital systems can inform more responsive planning processes. Changes in institutional practices reflect the broader shift in sustainability thinking. Destination Management Organizations (DMOs) in Europe are no longer limited to promotional functions; their roles increasingly include managing tourist flows, safeguarding resident interests, and supporting long-term, data-informed strategies [

30]. Affordable wireless monitoring technologies have been identified as tools that can assist these efforts by enabling local authorities to monitor crowding in real time without compromising privacy [

31]. Additional methods have also been proposed. An overtourism index has been developed that integrates governance indicators with digital infrastructure data [

19], while other work has explored how sensory marketing—via spatial design or multisensory cues—may help redirect tourist movement [

32]. These approaches suggest that behavioral nudges, rather than enforcement alone, could play an effective role in managing visitor density.

Despite advancements, technology alone does not address all underlying issues. Some studies caution that without addressing the deeper policy structures driving overtourism—particularly those centered on growth and economic dependency—technological solutions may remain superficial [

33]. From this perspective, sustainability requires not only improved tools but also a fundamental rethinking of tourism’s role and purpose. Others advocate for approaches that integrate digital tools with local participation, emphasizing spatial dispersion, adaptive governance, continuous monitoring, and a strong commitment to community priorities and long-term stability [

26].

Examples at the local level offer further clarity. In Darjeeling, homestay tourism has been described as following four guiding principles: reduce, reuse, recycle, and regulate [

34]. This approach helps alleviate pressure on formal infrastructure while generating local income, illustrating how grassroots solutions can complement broader policy frameworks.

That said, consistency across sustainability areas remains uneven. Analyses based on coupling–coordination models show that while some environmental and social goals align, links to infrastructure or economic planning are often weak. This suggests that even as the 5D model expands sustainability thinking, its real-world impact will depend on governance capacity and the ability to integrate across sectors.

2.3. Residents’ Perception and Support

Residents’ perceptions play a central role in determining the long-term sustainability of tourism. Yet, many analytical models tend to present these perceptions as straightforward reflections of economic gain or loss. However, one study challenges this view, suggesting that local attitudes are shaped by emotional responses, socio-technical changes, and broader structural forces, and that perceptions reflect how tourism is interpreted and experienced over time [

35].

This complexity is evident in several high-traffic destinations. For example, a gap has been identified between what tourists value—such as ease of transport and access to iconic landmarks—and what residents prioritize, including affordable housing and support for small businesses [

36]. The disconnect suggests that tourism policy often favors visitor convenience over community needs. Moreover, emotional well-being also shapes how tourism is received [

37]. In Germany’s Allgäu region, Steber and Mayer [

38] note that proximity tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted local routines and had a negative effect on residents’ overall life satisfaction. Residents responded with behavioral adjustments such as spatial avoidance but also expressed dissatisfaction with governance structures that failed to regulate influxes. In some cases, cultural boundaries become central to resident-tourist dynamics. In Mexico, it has been reported that while local communities express pride in their cultural traditions during the Day of the Dead, discomfort emerges when sacred spaces are disrespected by visitors [

39]. The decision to hold a second, more private alumbrada reflects a form of symbolic defense and emotional resilience.

However, not all responses are negative. In Cameron Highlands, Malaysia, tourism has been associated with perceived benefits such as increased employment and improved services, although concerns about ecological degradation remain [

40]. Similarly, sentiment analysis conducted in high-density tourism zones has identified overlapping emotional responses, including appreciation for economic opportunities alongside frustration over cultural displacement [

19].

These findings suggest that perception-based metrics offer important insights for planning and policy. When local sentiments are treated not as secondary to economic or environmental indicators but as equally vital, tourism governance becomes more adaptive. Therefore, resident responses—whether supportive, ambivalent, or resistant—must be understood not only as reactions to visitor presence, but also as reflections of broader questions of inclusion, identity, and control over space.

2.4. Theoretical Framework: Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR)

The Stimulus–Organism–Response (S-O-R) framework, originally developed in environmental psychology, offers a useful framework for examining how tourism-related stressors influence human behavior. Specifically, it suggests that external pressures—like crowding or environmental degradation—are filtered through individual or collective psychological responses, which then lead to specific actions or attitudes.

In this study, the S-O-R framework [

41] is adopted to explore how residents’ perceptions on sustainability in its five dimensions, prompted by tourism development, influence support for tourism in the context of overtourism. This framework argues that external stimuli activate internal processes—conscious and unconscious—such that individuals experience and perceive stimuli and thus are moved to act. It has been widely used in disciplines such as consumer behavior, organizational culture, and leadership studies [

42].

This sequential mechanism of stimuli (S) provoking internal emotional and cognitive responses in an organism (O and then resulting in internal states that lead to behavioral responses (R), has been instrumental in tourism research. For instance, in the Cameron Highlands, rising tourist numbers have been linked to ecological strain and changes in social cohesion. Residents have been observed adjusting their behaviors to maintain a sense of balance in daily life—an example corresponding to the organism stage of the S-O-R framework [

40].

Furthermore, perceptions and emotions mediate how external stimuli are interpreted. Resident responses are shaped not only by physical changes in the environment, but also by how those changes are perceived and experienced emotionally [

18]. While the study does not explicitly reference the S-O-R model, its findings are consistent with the model’s core assumptions.

Beyond the individual level, the S-O-R framework has also been applied to community and institutional responses. In rural Germany, local communities have exhibited both avoidance behaviors and civic engagement in response to pandemic-related tourism [

38]. Similarly, urban gardens in Tokyo introduced interventions such as visitor flow adjustments as adaptive responses to tourism pressure [

43]. These actions can be understood as organismic responses. A predictive perspective is demonstrated through the use of graph-based forecasting to detect early stress signals [

44]. Although computational in nature, this model reflects the logic of the S-O-R framework by identifying inputs, processing them through dynamic systems, and anticipating resulting responses.

This study advances the S-O-R model by treating the five domains of sustainability (environmental, economic, socio-cultural, political, and technological) as distinct stimuli that influences how residents perceive overtourism (Organism). These perceptions then shape Resident Support for Tourism (Response). Thus, stimulus refers to the sustainability dimensions; organism refers to residents’ psychological responses—cognitive (e.g., perceived risk, loss of control) and emotional (e.g., exhaustion, discomfort); and response reflects behavioral intentions toward tourism. The model is supported by studies such as Erul and Woosnam [

45] which found that emotional support and perceived control explained a substantial portion of support for tourism.

This framework captures the complexity of how overtourism is experienced and acted upon and offers a valuable basis for understanding resident behavior in rapidly changing urban tourism contexts.

2.5. Comparative Urban Contexts: Relevance of Istanbul and Athens as Contrasting Case Studies

Although overtourism has been extensively studied in Western European cities like Venice and Barcelona [

18], comparative research across less centralized or non-Western urban contexts remains limited. In this regard, Athens and Istanbul offer a compelling basis for analysis. Although Athens and Istanbul are geographically close, they differ markedly in how their urban spaces are structured and governed. As Bouchon and Rauscher [

23] note, overtourism is not simply a function of visitor numbers. The way cities are designed, managed, and represented in tourism discourse all influence how they absorb or resist tourism-related pressures.

Emotional strain can also emerge at the neighborhood level, as shown through sentiment-based analysis, which indicates that socio-cultural tensions may persist even when visitor numbers remain stable [

19]. Similarly, a comparative study of eleven historic cities highlights that densely built heritage areas are subject to particularly high levels of stress due to their physical limitations and symbolic prominence within tourism narratives, making them especially vulnerable [

46].

Athens and Istanbul reflect these dynamics in distinct ways. Both cities are under significant tourism pressure, but their governance models differ. Athens relies on a centralized heritage management approach, while Istanbul operates within a more fragmented, multi-layered system. These differences shape how each city handles tourist flows and formulates responses to overtourism.

Predictive tools may offer support where administrative structures vary. Wijayawardhana [

27] introduces a forecasting method based on political and economic indicators that can anticipate spikes in tourism demand. Though the model was not developed for a specific city, it could be adapted to suit the contexts of both Athens and Istanbul, allowing local decision-makers to respond more proactively. Crete, on the other hand, presents a different scenario. According to Vourdoubas [

47] the island has extremely high tourism density, particularly along its northern coast. Unlike Athens and Istanbul, which benefit from spatial and institutional diversity, Crete depends heavily on a narrow tourism economy. This combination of concentrated pressure and limited flexibility increases its exposure to environmental and infrastructural strain.

In parallel, governance responses to overtourism are increasingly shaped at the supranational level. Peloponnisios [

48] notes that the European Commission has begun to act as a policy entrepreneur—framing overtourism within broader sustainability goals and promoting coordination through digital and environmental regulatory instruments.

2.6. Hypotheses Development

2.6.1. Environmental Sustainability

Environmental sustainability refers to the extent to which tourism activities are perceived to align with environmental protection efforts, such as conserving natural resources and managing waste. Residents’ perceptions of overtourism are influenced by how well tourism is seen to align with these efforts. When tourism is viewed as environmentally responsible, it is more likely that overtourism will be perceived less negatively. Residents have been found to primarily attribute overtourism to environmental degradation caused by excessive tourist presence [

49]. Environmental stress has likewise been highlighted as a primary concern in overtourism literature [

4]. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H1: Perceived environmental sustainability has an effect on residents’ perceptions of overtourism.

2.6.2. Economic Sustainability

Economic sustainability in tourism refers to the extent to which tourism activities foster the local economy by creating jobs, enhancing infrastructure, and maintaining price stability. Residents are essential in promoting sustainable tourism, serving as cultural ambassadors and the primary community through which tourism is experienced [

50]. They play a critical role in the tourism sector, as their perceptions shape tourism's sustainability outlook. Their support is essential for the success and long-term sustainability of any tourism development [

51,

52]. When tourism contributes directly to the local economy, creates jobs, and enhances infrastructure without causing inflation, residents generally perceive tourism more favorably, considering economic benefits closely associated with favorable views on tourism according to empirical research [

53]. A plethora of studies verify the favorable attitudes towards additional tourism development being interlinked to personal and perceived benefits of tourism [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58]. It has been evident there is a negative correlation of residents’ perceptions of overtourism in Brazilian coastal destinations to the economic benefits and quality of public services [

59]. This stands as a testament to the evident positive benefits of employment by investment and consumption in the tourism sector [

60]. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H2: Perceived economic sustainability has an effect on residents’ perceptions of overtourism.

2.6.3. Socio-Cultural Sustainability

Mitigation of overtourism resentment can be achieved through tourism that promotes the local culture preservation, mutual understanding, and the avoidance of cultural commodification. It has been evident that a community's contentment with tourism growth is determined by the way in which residents view the economic, environmental, and socio-cultural advantages [

61]. Residents exhibit a more favorable response to tourism when it is in harmony with and bolsters local cultural identity [

62]. Caro-Carretero and Monroy-Rodríguez [

63] discovered that residents appreciated the contribution of tourism to cultural preservation yet emphasized the necessity of balancing development with the needs of the community. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H3: Perceived socio-cultural sustainability has an effect on residents’ perceptions of overtourism.

2.6.4. Political Sustainability

The implementation of effective governance with tools such as inclusive policies, regulations, and mitigation strategies seems to mitigate the perceived harms of overtourism. Overtourism’s perceived harms may be reduced when effective governance—such as inclusive policies, regulations, and mitigation strategies—is implemented. In contrast, more negative perceptions tend to be shaped when political mechanisms are viewed as weak or ineffective by residents. The behavior of tourists is the primary correlation of how overtourism is perceived by residents but not the sole parameter. It is important to notice, however, that the performance of local government management in destinations also affects how overtourism is perceived. When the governance of tourism is taken as inclusive, responsive, and well-coordinated, the negative feelings against overtourism will tend to diminish. In particular, positive government management practices evaluations have been observed as foiling the adverse impact of overtourism on the perception of the residents [

10]. This illustrates that the issue of political sustainability, which is promoted through transparent decision-based processes, policy responsiveness, and local participation, can be beneficial in moderating the concerns of communities facing excessive tourism pressure. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H4: Perceived political sustainability has an effect on residents’ perceptions of overtourism.

2.6.5. Technological Sustainability

Technology and ICT, with smart tourism tools, can ease overtourism pressure. Technologically progressive destinations may be perceived as more resilient [

5]. The use of smart tourism technologies has been examined for their potential to enhance visitor experiences and improve operational efficiency [

64]. It has also been suggested that such technologies play a pivotal role in promoting sustainable practices by helping to mitigate environmental and cultural heritage impacts [

65]. Smart tourism utilizes information and communication technologies (ICTs) to improve the effectiveness, sustainability, and overall experience of tourism for both tourists and locals [

66]. As Shafiee [

67] outlines, smart destinations incorporate IoT for monitoring and managing tourist flows, as well as mobile apps for delivering real-time information and personalized recommendations. By leveraging data from sensors, social media, and mobile devices, smart destinations can gain insights into tourist behavior and preferences. This data-driven approach enables destinations to optimize their offerings, manage crowds effectively, and improve visitor satisfaction. The adoption of smart tourism technologies seems to be able to improve the tourist experience as well as the performance of destination management systems. As Accessibility and interactivity have been identified as key factors influencing smart technology–enhanced tourist experiences, both of which are significantly associated with visitor satisfaction. In addition, smart technologies have been shown to positively influence word of mouth, revisiting intention, and willingness to pay a premium [

68]. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H5: Perceived technological sustainability has an effect on residents’ perceptions of overtourism.

2.6.6. Residents’ Perception and Support for Tourism

Residents’ responses to tourism depend on how they view the effects of overtourism in their daily lives. According to S-O-R framework, negative internal evaluations influence how external conditions impact behavioral intentions, such as support for tourism development. When residents see tourism as overwhelming, damaging to their quality of life, or poorly managed, they are less willing to support tourism initiatives. Negative perceptions of overtourism have been associated with a decline in how residents view their town’s livability, leading to stronger support for tourism restrictions, particularly during peak seasons [

10]. Additionally, high levels of tourist seasonality have been linked to lasting lifestyle changes, affecting residents’ access to services and overall well-being [

69]. Such disruptions may impair psychological coping mechanisms and reduce local support for ongoing tourism development. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H6: Residents’ perceptions of overtourism have an effect on their support for tourism.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

The study focused on permanent residents of Istanbul and Athens who were at least 18 years old and had lived continuously in their respective cities for a minimum of one year as of May 2025. An a priori power analysis conducted with G*Power 3.1.9.7 indicated that, assuming a medium effect size (f² = 0.15), α = .05, and statistical power of 90 %, a minimum of 123 valid surveys per city was required [

70,

71,

72]. Therefore, the sample size is 136 in Istanbul and 149 in Athens.

Data was collected via an online questionnaire hosted on Google Forms. The survey link was shared only with individuals who met the screening criteria—continuous residence in the focal city for the previous 12 months and no employment in, or ownership of, a business that earns direct income from tourism. Dissemination channels included local neighborhood forums, social-media groups, and university e-mail lists, resulting in a convenience sample of adult residents from both cities.

3.2. Measurement Tools

The scale items used in this study were adapted from instruments with established validity in literature. Items measuring the five sustainability dimensions—environmental, economic, socio-cultural, political, and technological—were sourced from previous work [

5]. Perceptions of overtourism were measured using items based on existing scales [

10], and residents’ support for tourism was assessed using established items from earlier studies [

73]. Measurement tools are presented in

Table 1.

All items were administered to participants in both Istanbul and Athens using a five-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). The scale was translated into Turkish and Greek through a forward–backward translation procedure, and conceptual equivalence was confirmed by subject-matter experts during the translation process.

3.3. Data Analysis

The structural equation model was estimated to be using SmartPLS 4.1.1.4. The reliability and validity of the measurement model were verified with Composite Reliability, AVE, and HTMT criteria [

74]; then, structural path coefficients were obtained using the bootstrap method with 5,000 replications [

71,

75]. For intercity comparisons, measurement equivalence was tested with the MICOM procedure and path coefficients in Istanbul and Athens groups were compared with the help of Permutation/PLS-MGA [

76].

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

A total of 285 people participated in the study, 136 from Istanbul and 149 from Athens. In the case of Istanbul, 60% of participants identified as male, 39% as female and 1% chose not to disclose their gender. The average age of participants in Istanbul was 29.3 years, ranging from 18 to 69 years. The average length of residence in the city was approximately 18.9 years. By comparison, the Athens sample consisted of 56% male and 42% female respondents, with 2% choosing not to state their gender. The average age of participants in Athens was slightly higher at 32.3 years, ranging from 17 to 65 years. On average, participants had lived in Athens for 14.3 years. These demographic distributions suggest that both samples are predominantly composed of long-term residents and include a balanced mix of age and gender, thus ensuring sufficient diversity for comparative analysis across contexts.

4.2. Evaluation of the Measurement Model

In line with the PLS-SEM procedure, the evaluation of the reflective measurement model was carried out through tests of indicator reliability, internal consistency, convergent validity and discriminant validity. The results are presented in

Table 2.

As seen in

Table 2, all constructs in both samples exceeded the thresholds for internal consistency and convergent validity. In particular, all Composite Reliability (CR) scores were well above the recommended minimum of 0.70, while Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values exceeded the threshold of 0.50, indicating that the constructs explained a sufficient proportion of the variance of their indicators. In addition, Cronbach's Alpha values were consistently high, further confirming the internal consistency of the constructs.

4.3. Discriminant Validity

HTMT (Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio) was used to assess discriminant validity.

Table 3 and

Table 4 present the HTMT values in pairs for the Istanbul and Athens samples, respectively.

All HTMT values in both city samples were below the conservative threshold of 0.85. This confirms that the constructs show sufficient discriminant validity and makes sure that each latent variable is empirically distinct from the others in the model.

4.4. Measurement Invariance of Composite Models (MICOM)

To assess whether the latent constructs were measured equivalently between the two groups (Istanbul and Athens), the Measurement Invariance of Composite Models (MICOM) procedure was applied, following the structured three-step approach that evaluates (1) configural invariance, (2) compositional invariance, and (3) equality of means and variances [

76].

Structural invariance refers to the equivalence of the underlying model structure across groups. Structural invariance is established because the same measurement model, indicator specification and estimation settings are used for both samples. This means that both groups share a common conceptual and operational foundation.

Compositional invariance assesses whether the composite scores of latent variables occur similarly across groups. This was tested using the permutation algorithm (5,000 resamplings). As shown in

Table 5, five of the seven constructs showed compositional invariance (p > 0.05). However, ECS and RST failed to meet this criterion because their correlation values were below the critical 5% quantile, and their p-values were statistically significant (p < 0.05). This suggests that these two constructs may be perceived or interpreted differently across groups at the compositional level.

The last step tested whether the latent variable scores differed significantly in their means or variances across groups.

Table 6 shows the results. Only ECS and OVP showed no significant difference, indicating partial invariance. All other constructs showed statistically significant differences in means, variances or both, indicating a lack of scalar invariance.

According to

Table 6, the results show that while construct invariance was achieved for most constructs and compositional invariance was confirmed, full measurement invariance was not established due to differences in the ECS and RST components and differences in the scalar level in the various constructs. However, in line with previous literature the presence of partial measurement invariance allows for careful conduct of Multiple Group Analysis (MGA), especially when construct and partial compositional invariance are verified.

4.5. Multigroup Analysis (MGA)

Following the MICOM procedure, although full measurement invariance cannot be achieved, the establishment of configural and partial compositional invariance allows the application of Multiple Group Analysis (MGA). MGA was used to examine whether structural relationships differed significantly between the Istanbul and Athens samples. The PLS-MGA approach [

75] was used, which compares path coefficients between groups based on nonparametric resampling.

Table 7 shows multigroup comparison of structural path coefficients.

Among the structural relationships tested, the path between Environmental Sustainability (ENS) and Perception of Overtourism (OVP) showed a statistically significant difference between the two groups (p_MGA = 0.002). Interestingly, the relationship was negative in Istanbul and positive in Athens, indicating that environmental concerns are perceived and linked to overtourism in significantly different ways in the two cities. No statistically significant differences were found for the remaining structural pathways. Although some relationships (ECS → OVP and SCS → OVP) appeared stronger in Athens than in Istanbul, the differences were not statistically significant at the 5% level according to the MGA test.

5. Discussion, Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Key Findings

The empirical results underscore that residents’ perceptions of overtourism are intricately shaped by how they evaluate sustainability across five dimensions. In line with the S-O-R framework, the five sustainability dimensions act as external stimuli (S) that influence cognitive evaluations (O), which then affect behavioral intentions, specifically resident support for tourism (R).

In Athens, perceptions of strength in environmental, socio-cultural, and economic sustainability were associated with heightened sensitivity to overtourism. This finding supports the H1 that positive sustainability appraisals do not necessarily mitigate overtourism stress; rather, they can amplify it by raising expectations and awareness. For instance, the positive association between environmental sustainability and overtourism perception (β = 0.298) suggests that residents may interpret visible environmental interventions—such as heritage conservation or urban greening—not as solutions, but as indicators of increased tourist activity and pressure [

19,

49]. Conversely, in Istanbul, environmental sustainability exhibited a negative relationship with overtourism perception (β = –0.249), implying that green infrastructure and environmental management may effectively buffer resident concerns.

Economic sustainability (H2) was also a significant predictor of overtourism perception in Athens (β = 0.231), likely reflecting the salience of rising living costs, housing displacement, and perceived inequity in tourism’s economic distribution [

59]. For Istanbul, this relationship was not statistically supported, possibly due to the more dispersed tourism economy and broader labor absorption across sectors.

Socio-cultural sustainability (H3) followed a similar pattern. Its significant path in Athens (β = 0.198) suggests that perceived erosion of local culture, identity, and everyday life may amplify resident dissatisfaction, as also reported by Caro-Carretero and Monroy-Rodríguez [

63]. The non-significant effect in Istanbul could reflect the city’s polycentric urban structure and pluralistic cultural identity, which may dilute perceived cultural disruption.

Political sustainability (H4) and technological (H5) sustainability dimensions were not statistically significant predictors of overtourism perception in either city. While these domains are prominently featured in sustainability and smart tourism literature [

19,

33], their limited perceptual salience suggests they may lack visibility or resonance with residents lived experiences—an important consideration for destination planners and policymakers.

Finally, overtourism perception had a significant and negative impact on residents’ support for tourism development in Athens (H6; β = –0.229), consistent with prior applications of the S-O-R model, which posit that negative affective evaluations reduce behavioral support [

45]. In Istanbul, this relationship was negative but not statistically significant (β = –0.101), possibly indicating a higher threshold of tolerance, greater economic dependency, or differing expectations of tourism’s role in the urban fabric [

40].

Collectively, these findings validate the explanatory capacity of the S-O-R framework while emphasizing its contextual sensitivity. The varying strength and directionality of relationships across cities highlight how residents’ responses are filtered through localized perceptions of governance, infrastructure, and cultural resilience. While environmental factors emerge as salient in both cases, albeit with contrasting interpretations, political and technological sustainability remain under-activated constructs, pointing to gaps in public communication or engagement. These divergences underscore the need for perception-sensitive tourism planning, tailored not only to objective sustainability indicators but also to how these indicators are interpreted and internalized by local communities.

5.2. Contribution to Theory

This study makes significant theoretical contributions by extending the S-O-R into the domain of overtourism and urban sustainability. While S-O-R has been widely applied in tourism and consumer behavior research to explain how external stimuli shapes internal states and behavioral outcomes [

41,

45], its application to overtourism has largely centered on tourist experiences. Recent study shifts the analytical focus toward residents, offering a multidimensional, context-sensitive perspective.

By conceptualizing five sustainability dimensions as distinct external stimuli, this research advances a more granular understanding of how residents process tourism-related pressures. It moves beyond linear cause-effect reasoning and responds to recent scholarly calls for models that account for place-based variability and perceptual complexity [

35,

77].

The findings also refine the conceptualization of the organism component in S-O-R theory. Rather than treating it as a static affective response, this study demonstrates that resident perception is shaped by collective urban experience, local governance structures, and cultural expectations. The differential directionality of environmental sustainability’s influence in Athens and Istanbul reinforces the notion that perception is not a passive intermediary but a dynamic, city-specific construct—responsive to governance visibility, urban form, and symbolic interpretations of place.

Additionally, this research is among the first to formally incorporate political and technological sustainability within the S-O-R stimulus layer in overtourism modeling. Although these two dimensions did not yield statistically significant paths, their inclusion reflects a necessary evolution in sustainability scholarship. As highlighted in recent frameworks [

18,

46], governance capacity and digital infrastructure are increasingly central to the long-term resilience of tourism systems. The lack of perceptual salience found here may stem from their limited public visibility or developmental immaturity—issues which future research should investigate more closely.

Empirical support for the S-O-R framework was further reinforced through the observed negative link between overtourism perception and residents’ support for tourism in Athens. This confirms that internal evaluations, shaped by multidimensional sustainability perceptions, meaningfully influence behavioral intentions. The variation in model strength between cities also illustrates that such processes are deeply embedded in urban morphology, socio-political histories, and resident expectations—underscoring the flexibility and transferability of the SOR model when integrated with contextual sustainability thinking.

5.3. Contextual Insights: Reflections on the city-specific dynamics of Athens vs. Istanbul

The comparative analysis of Athens and Istanbul reveals that overtourism arises not solely from tourist volume but through spatial, governance, and socio-historical dynamics. In Athens, perceptions are shaped by environmental, economic, and socio-cultural concerns within a centralized planning regime and dense urban form, concentrating tourism pressure in residential zones—paralleling cases like Venice and Dubrovnik [

25,

46]. Istanbul, by contrast, exhibits weaker associations between sustainability and overtourism, likely due to its polycentric layout and dispersed tourism infrastructure. The lack of significant RST effects suggests either muted discontent or distinct socio-political framing. Environmental sustainability diverges notably: in Athens, it intensifies crowding perception; in Istanbul, it signals institutional responsiveness [

19,

39]. Both cities show weak links to political and technological sustainability, reflecting an institutional visibility gap. Tools like predictive analytics or emotional mapping [

27,

31] remain underleveraged. Effective governance must integrate perceptual and spatial dimensions within local contexts.

5.4. Practical Implications

The findings highlight that overtourism perceptions are shaped differently across urban contexts, necessitating destination-specific strategies. In Athens, the significant influence of environmental, economic, and socio-cultural sustainability perceptions suggests an urgent need for interventions tailored to dense heritage areas. Policymakers may prioritize:

Community-based heritage conservation, ensuring that preservation efforts do not displace residents or commodify local identity.

Green infrastructure projects that not only manage environmental impacts but also improve quality of life for residents.

Affordable housing policies and anti-displacement mechanisms that mitigate economic externalities of tourism [

24,

46].

In contrast, Istanbul’s more fragmented and polycentric urban structure calls for a different approach. Although overtourism perception is lower, this may mask latent tensions. Proactive strategies should include improved infrastructure planning, visitor dispersal, and public communication mechanisms that elevate resident awareness and engagement before pressures intensify. Furthermore, across both cities, findings indicate that overtourism perception alone can erode resident support, even when sustainability metrics are moderately positive. As such, building resident trust and fostering a sense of ownership and co-management are critical components of long-term destination resilience.

The study’s non-significant findings regarding technological and political sustainability dimensions reveal both a challenge and an opportunity. While academic models emphasize their relevance [

19,

33], these tools often remain invisible or under-communicated to the general public. To address this, tourism planners and Destination Management Organizations (DMOs) should:

Enhance the visibility of smart tools, such as geospatial crowd monitoring, predictive analytics, and mobile-based feedback systems.

Publicly communicate their role, impact, and limitations in shaping tourism governance.

Integrate citizen participation in the design and evaluation of digital governance systems [

30,

31].

In sum, this study validates the theoretical utility of both the S-O-R paradigm and a five-dimensional sustainability framework in overtourism research. It demonstrates how resident responses are mediated through layered perceptual mechanisms and confirms that sustainability is not monolithic, but hierarchically and situationally interpreted. These insights offer a replicable yet adaptable theoretical model for future studies investigating overtourism dynamics in diverse urban contexts.

5.5. Theoretical and Managerial Contributions

From the managerial implications perspective, the results suggest that DMOs and policymakers should consider residents not as passive recipients of tourism impacts but to the contrary as active actors whose perceptions are able to shape the success or failure of tourism strategies. In particular, investing in smart tourism technologies, inclusive governance and tangible socio-economic benefits can assist in diminishing overtourism tension while promoting local support.

The comparative design reveals the context-dependent nature of overtourism perception, challenging universal or one-dimensional narratives and emphasizing the need for place-sensitive modeling.

6.6. Limitations

Despite the considerable contributions received, the present study has several limitations. First, we need to consider that the sampling methodology relied on convenience sampling and online questionnaire distribution, which may limit the representativeness of the participant pool and introduce potential selection bias. Furthermore, the research employed a cross-sectional design with data being collected at one point in time. This limits the opportunity for making causal inferences and captures the development of resident perceptions. Finally, the contextual scope of the study was limited to Athens and Istanbul, two eastern Mediterranean cities. Therefore, the results cannot be directly attributed to other countries, especially those with differing cultural, political or socio-economic settings.

6.7. Future Directions

There are various possible directions that future research could explore and that are likely to enhance the current results. Longitudinal research with monitoring on how resident’s perceptions and attitudes evolve over time would allow further assessment to the dynamic relationships outlined in the S-O-R framework and may assist in the identification of potential tipping points. In addition, the contextual expansion would be a future direction recommendation, with model testing in a more diversified set of urban and rural destinations (e.g. with varying levels of tourism intensity, infrastructure and governance complexity) for generalization increase. On the qualitative augmentation perspective, the use of methods such as in-depth interviews, focus groups, ethnographic observation, or emotional mapping may reveal more subtle dynamics underpinning residents’ perceptions of overtourism. Finally, future research could address the mediational role of variables such as media consumption, digital literacy or political interest, for the formation of residents’ perceptions towards tourism, in relation to the residential population, especially in increasingly digitized tourism environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.V., Ş.O., and B.Y.; methodology, B.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, E.V., Ş.O., and B.Y.; writing—review and editing, E.V., Ş.O., and B.Y.; project administration, B.Y.; funding acquisition, E.V., Ş.O., and B.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Türkiye and approved by the Institutional Review Board of BETADER Science and Advisory Board (Reference Number 250625-001 and date of approval 10/04/2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- UN Tourism. International tourist arrivals grew 5 % in Q1 2025 (World Tourism Barometer). Madrid: UN Tourism; 2025 May 21.

- Statista Research Department. International tourist arrivals in Europe 2006–2024. Hamburg: Statista; 2025 Jun 10 [cited 2025 Jun 26]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/273598/international-tourist-arrivals-in-europe/.

- Ndrevataj M. Cultural sustainability for sustainable cities development: notes from UNESCO and Venice City. In: Ndrevataj M, editor. The Sustainable Organization. Cham: Springer; 2025. p. 219–35.

- Capocchi A, Vallone C, Pierotti M, Amaduzzi A. Overtourism: a literature review to assess implications and future perspectives. Sustainability. 2019;11(12):3303. [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh SM, Chee SY, Salee A. Scale development for measuring sustainability of urban destinations from the perspectives of residents, tourists, businesses and government. J Sustain Tour. 2024. Epub ahead of print.

- Goodwin H. Overtourism: lessons for a better future. London: Responsible Tourism Publishing; 2019.

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our common future. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1987.

- Placet M, Anderson R, Fowler KM. Strategies for sustainability. Res Technol Manag. 2005;48(5):32–41. [CrossRef]

- Koens K, Postma A, Papp B. Is overtourism overused? Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context. Sustainability. 2018;10(12):4384. [CrossRef]

- García-Buades ME, García-Sastre MA, Alemany-Hormaeche M. Effects of overtourism on residents’ perceptions in Alcúdia, Spain. J Outdoor Recreat Tour. 2022;39:100499. [CrossRef]

- Seraphin H, Sheeran P, Pilato M. Over-tourism and the fall of Venice as a destination. J Destin Markag Manag. 2018;9:374–6. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations; 2015.

- Figueiredo N, Abrantes JL, Costa S. Mapping the sustainable development in health tourism: A systematic literature review. Sustainability. 2024;16(5):1901. [CrossRef]

- Buitrago J, Yñiguez R. Measuring overtourism: a systematic review of quantitative indicators. Tourism Manag. 2021;88:104398. [CrossRef]

- Mihalič T, Žabkar V, Cvelbar LK. A hotel sustainability business model: Evidence from Slovenia. J Sustain Tour. 2020;28(6):824–46. [CrossRef]

- Santos-Rojo C, Llopis-Amorós M, García-García JM. Overtourism and sustainability: A bibliometric study (2018–2021). Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2023;188:122285. [CrossRef]

- Koens K, Postma A, Papp B. Is overtourism overused? Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context. Sustainability. 2018;10(12):4384. [CrossRef]

- Alsharif AH, Mohd Isa S, Md Salleh NZ, Abd Aziz N, Abdul Murad SM. Exploring the nexus of over-tourism: Causes, consequences, and mitigation strategies. J Tourism Serv. 2025;16(30):99–142. [CrossRef]

- Tai K, Liao M, Liu X. Exploring the convergence of cyber–physical space: Multidimensional modeling of overtourism interactions. Trans GIS. 2024;28(7):2425–44.

- Antonio RS, Alamsyah A. Analyzing overtourism dynamics in Bali: A data-driven approach using geospatial analysis and text classification. In: Proc 2024 Beyond Technology Summit on Informatics Int Conf (BTS-I2C). IEEE; 2024. p. 544–9. [CrossRef]

- Seabra C, Reis P, Abrantes JL. The influence of terrorism in tourism arrivals: A longitudinal approach in a Mediterranean country. Ann Tour Res. 2020;80:102811. [CrossRef]

- Drápela E. Creating strategies to mitigate the adverse effects of overtourism in rural destinations: Experience from the Czech Republic. Sustainability. 2023;15:16958. [CrossRef]

- Bouchon F, Rauscher M. Cities and tourism, a love and hate story; towards a conceptual framework for urban overtourism management. Int J Tour Cities. 2019;5(4):598–619. [CrossRef]

- Danilović Hristić N, Pantić M, Stefanović N. Tourism as an opportunity or the danger of saturation for the historical coastal towns. Sustainability. 2024;16(10):4080. [CrossRef]

- Butler RW, Dodds R. Overcoming overtourism: A review of failure. Tourism Rev. 2022;77(1):35–53. [CrossRef]

- Gowreesunkar V, Séraphin H. What smart and sustainable strategies could be used to reduce the impact of overtourism? Worldw Hosp Tour Themes. 2019;11(5):484–91. [CrossRef]

- Wijayawardhana AJ. Forecasting future tourism demand to popular tourist attractions to assess overtourism: A machine learning modeling approach. In: Proc 10th Int Conf Eng Emerg Technol (ICEET). IEEE; 2024.

- Yamin M, Mahayasa DPS, Satyawan DS, Nurudin A. Revenge tourism in Banyumas Regency: Examining the interrelationship among social media, overtourism, and post-COVID-19 impacts. Smart Tourism. 2024;4(2):Article 2408. [CrossRef]

- Nădăși L, Kovács S, Szőllős-Tóth A. The extent of overtourism in some European locations using multi-criteria decision-making methods between 2014 and 2023. Int J Tour Cities. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Eckert C, Zacher D, Pechlaner H, Namberger P, Schmude J. Strategies and measures directed towards overtourism: A perspective of European DMOs. Int J Tour Cities. 2019;5(4):639–55. [CrossRef]

- Mestre dos Santos T, Neto Marinheiro R, Brito e Abreu F. Wireless crowd detection for smart overtourism mitigation. In: Kornyshova E, et al., editors. Smart life and smart life engineering. Cham: Springer; 2025. p. 237–58. [CrossRef]

- Handler I, Leung R. Can sensory marketing be used to address overtourism? Evidence from religious attractions in Kyoto, Japan. Tour Cult Commun. 2024;24(4):1–24. [CrossRef]

- Milano C, Novelli M, Russo AP. Anti-tourism activism and the inconvenient truths about mass tourism, touristification and overtourism. Tour Geogr. 2024;26(8):1313–37. [CrossRef]

- Dutta S, Mukhopadhyay D. Homestay-tourism – A viable alternative to the perils of overtourism in the Darjeeling hills of West Bengal, India. Environ Conserv J. 2024;25(2):516–31. [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh SM, Seyfi S. Residents’ perceptions and attitudes toward tourism development: A perspective article. Tour Rev. 2021;76(1):51–7. [CrossRef]

- Venice E, UNESCO R, Municipality V. Managing cultural destinations: The case of Venice. UNWTO Reports. 2024.

- Seabra C, Dolnicar S, Abrantes JL, Kastenholz E. Heterogeneity in risk and safety perceptions of international tourists. Tour Manag. 2013;36:502–10. [CrossRef]

- Steber F, Mayer M. Overtourism perception among residents in a rural proximity destination during the COVID-19 pandemic – The writing on the wall for a sustainability transition of tourism? Z Für Tourwiss. 2024;16(3):228–60. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Aguirre DP, Alvarado-Sizzo I, Moury-Fernandes BG. Intangible cultural heritage versus tourism: Residents’ reactions to temporal overtourism during the Day of the Dead in Mixquic, Mexico. J Herit Tour. 2025;20(2):235–59. [CrossRef]

- Saufi SAM, Azinuddin M, Mat Som AP, Hanafiah MH. Overtourism impacts on Cameron Highlands community’s quality of life: The intervening effect of community resilience. Tour Plan Dev. 2025;22(2):228–35. [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian A, Russell JA. An approach to environmental psychology. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press; 1974.

- Hochreiter V, Benedetto C, Loesch M. The Stimulus–Organism–Response (S–O–R) paradigm as a guiding principle in environmental psychology: Comparison of its usage in consumer behavior and organizational culture and leadership theory. J Entrep Bus Dev. 2023;3(1):7–16. [CrossRef]

- Shimoyamada S. Horticultural overtourism in Tokyo: Coopetition for successful enticement of visitors from over- to less crowded gardens. Sustainability. 2024;16(21):9444. [CrossRef]

- Kong X, Huang Z, Shen G, Lin H, Lv M. Urban overtourism detection based on graph temporal convolutional networks. IEEE Trans Comput Soc Syst. 2024;11(1):442–54. [CrossRef]

- Erul E, Woosnam KM. Explaining residents’ behavioral support for tourism through two theoretical frameworks. J Travel Res. 2021;61(2):362–77. [CrossRef]

- Żemła M. European historic cities and overtourism – Conflicts and development paths in the light of systematic literature review. Int J Tour Cities. 2024;10(1):353–72. [CrossRef]

- Vourdoubas J. Evaluation of overtourism in the island of Crete, Greece. Eur J Appl Sci Eng Technol. 2024;2(6):21–32. [CrossRef]

- Peloponnisios M. The European Commission as a policy entrepreneur in addressing overtourism. HAPSc Policy Briefs Ser. 2024;5(2):71–80. [CrossRef]

- Szromek AR, Hysa B, Karasek A. The perception of overtourism from the perspective of different generations. Sustainability. 2019;11(24):7151. [CrossRef]

- González C, Camargo BA, González AM, Avila JA. Tourism-phobia and urban conflicts in heritage cities: A case study of Barcelona, Spain. Urban Stud. 2018;55(14):3119–36. [CrossRef]

- Vagena A. Overtourism: Definition and impact. Academia Letters. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bimonte S, Punzo LF. Tourist development and host–guest interaction: An economic exchange theory. Ann Tour Res. 2016;58:128–39. [CrossRef]

- Lankford SV, Howard DR. Developing a tourism impact attitude scale. Ann Tour Res. 1994;21(1):121–39. [CrossRef]

- Perdue RR, Long PT, Allen L. Resident support for tourism development. Ann Tour Res. 1990;17(4):586–99. [CrossRef]

- Pizam A. Tourism impacts: The social costs to the destination community as perceived by its residents. J Travel Res. 1978;16(4):8–12.

- Ryan C, Montgomery D. The attitudes of Bakewell residents to tourism and issues in community responsive tourism. Tour Manag. 1994;15(5):358–69. [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Sánchez A, Porras-Bueno N, Plaza-Mejía MÁ. Explaining residents’ attitudes to tourism: Is a universal model possible? Ann Tour Res. 2011;38(2):460–80. [CrossRef]

- Muler González V, Coromina Soler L, Galí Espelt N. Overtourism: Residents’ perceptions of tourism impact as an indicator of resident social carrying capacity – A case study of a Spanish heritage town. Tour Rev. 2018;73(3):321–34. [CrossRef]

- Pereira TB, de Andrade MM. Overtourism: Residents’ perceived impacts of tourism saturation. Tour Anal. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen PC, Schinckus C, Chong FHL, Nguyen BQ, Tran DLT. Tourism and contribution to employment: Global evidence. J Econ Dev. 2024;27(4):22–37. [CrossRef]

- Homsud N, Promsaard S. The effects of residents’ image and perceived tourism impact to residence satisfaction and support: A case study of Hua-Hin Prachubkirikhan. In: Proc WEI Int Acad Conf. 2015; Rome, Italy. p. 190–9.

- Andereck KL, Vogt CA. The relationship between residents’ attitudes toward tourism and tourism development options. J Travel Res. 2000;39(1):27–36. [CrossRef]

- Caro-Carretero R, Monroy-Rodríguez S. Residents’ perceptions of tourism and sustainable tourism management: Planning to prevent future problems in destination management—The case of Cáceres, Spain. Cogent Soc Sci. 2025;11(1):2447398.

- Buhalis D, Amaranggana A. Smart tourism destinations. In: Tussyadiah I, Inversini A, editors. Information and communication technologies in tourism 2015. Cham: Springer; 2015. p. 553–64.

- Leong WY, Leong YZ, Leong WS. Smart tourism in ASEAN: Leveraging technology for sustainable development and enhanced visitor experiences. Int J Soc Sci Art Innov. 2024;4(3):19–31. [CrossRef]

- Makkad SB. Leveraging smart tourism: Enhancing visitor experiences through technological integration. Int J Tour Technol. 2024;10(1):45–59.

- Shafiee MM. Navigating overtourism destinations: Leveraging smart tourism solutions for sustainable travel experience. Smart Tourism. 2024;5(2):2841. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Sotiriadis M, Shen S. Investigating the impact of smart tourism technologies on tourists’ experiences. Sustainability. 2022;14(5):3048. [CrossRef]

- Zmyślony P, Kowalczyk-Anioł J, Dembińska M. Deconstructing the overtourism-related social conflicts. Sustainability. 2020;12(4):1695. [CrossRef]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41(4):1149–60. [CrossRef]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988.

- Yaprak B, Cengiz E. Do consumers really care about social media marketing activities? Evidence from Netflix’s Turkish and German followers in social media. Ege Acad Rev. 2023;23(3):441–56. [CrossRef]

- Munanura IE, Kline JD. Residents’ support for tourism: The role of tourism impact attitudes, forest value orientations, and quality of life in Oregon, United States. Tour Plan Dev. 2023;20(4):566–82.

- Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res. 1981;18(1):39–50. [CrossRef]

- Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev. 2019;31(1):2–24. [CrossRef]

- Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. Int Mark Rev. 2016;33(3):405–31. [CrossRef]

- Hristov I, Appolloni A, Chirico A. The adoption of key performance indicators for sustainability: A five-dimensional framework. Bus Strateg Environ. 2022;31(7):3216–32. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).