1. Introduction

Montenegro’s national parks, particularly Durmitor and Skadar Lake, are among the country’s most valuable natural and cultural heritage sites. These protected areas play a crucial role in environmental conservation while also serving as key tourism destinations that contribute significantly to the national economy. Understanding how tourism interacts with these landscapes, communities, and historical legacies is essential for developing sustainable management strategies that balance conservation with economic benefits [

1,

2,

3,

4].

National Park Durmitor is the largest national park in Montenegro. It includes the Tara Canyon, the canyons of Tara’s right tributaries (Vaškovska River and Draga), Zabojsko Lake on Sinjajevina, with a narrow belt connecting it to the Crna Poda primeval forest in the Tara Canyon, the Durmitor massif, parts of the Piva Mountain, the Sušica Canyon, the source area of Bukovica, and most of Jezera Drobnjačka. The total area of the park is 39,000 hectares [

5]. This territory covers five Montenegrin municipalities: Žabljak, Pljevlja, Plužine, Šavnik, and Mojkovac. The Tara Canyon, from the confluence of the Bistrica River to Šćepan Polje, stretching 80 km, was included in the list of World Ecological Reserves in 1987, while National Park Durmitor was added to the UNESCO World Cultural and Natural Heritage List in 1980 [

6]. The depth of the Tara Canyon reaches u

p to 1,300 meters in some areas, making it the deepest canyon in Europe and the second largest in the world [

7].

N

P Durmitor exhibits an extraordinary complexity of geodiversity, featuring unique relief characteristics, significant altitude differences over short distances, massive mountain peaks, rich mountain rivers with stunning landscapes, and a large number of glacial lakes. Due to its numerous geological, geomorphological, hydrological, botanical, historical, and cultural attributes, this area is considered to have exceptional tourism potential [

8].

Evidence of prehistoric settlements within N

P Durmitor was found in caves in the Piva region, which were flooded in 1976 during the creation of an artificial lake for the Piva Hydroelectric Plant: Odmut Cave and the cave at Sastavci. Archaeological findings (ceramic artifacts, stone tools, and animal bones) from Odmut Cave belong to the pre-Mesolithic, Mesolithic, and partially Neolithic phases of settlement development. The Neolithic phase was based on the Vinča culture, while ceramic finds from the cave at Sastavci indicate the influence of the Starčevo culture [

9]. Significant archaeological remains from the Bronze Age testify to the presence of the Illyrians and other peoples in this area, such as burial sites – tumuli around Lever Tara, in Tepci and Todorov Dol. Among the archaeological remains from the Roman period, the bridge on the Bukovica River near Šavnik, also known as the Uskoci Bridge, stands out. From the medieval period, notable finds include stećci (stone tombstones) found in Novakovići, Bare Žugića, Šćepan Polje, Borkovića Katun, and other locations. There are also four significant medieval sites that, however, have not been extensively researched: the remains of the fortifications Pirlitor, Soko-Grad, Taban-Grad, and Kukulj-Grad [

6,

10].

In the area of N

P Durmitor, there are several sacral objects (churches and monasteries) that have played a significant historical and cultural role not only in this region but beyond: the Monastery of Dovolja on the right bank of the Tara River (15th century), the Monastery of St. Archangel Michael on the right bank of the Tara River (15th century), the Monastery of Podmalinsko on the right bank of the Bukovica River (15th century), the Monastery of Bijela in the canyon of the Bijela River (17th century), the Monastery of Dobrilovina on the left bank of the Tara River (17th century), and the Monastery of Piva (16th century) as the most significant [

6].

In the area of Skadar Lake National Park, there are numerous geological, geomorphological, and climatic features, but the greatest value of the lake lies in the abundance of clean water and the diversity of plant and animal life [

5]. Skadar Lake National Park covers a large part of the Podgorica-Skadar basin. The shoreline of Skadar Lake is highly indented, with numerous islands (Grmožur, Starčevo, Beška, Moračnik, Gradac, Tophala, Gorica, Gljat, etc.), bays, and capes, while the karst surroundings of the lake contain many underground cave formations, including Lipska Cave, Obodska Cave, Grbočica, Bobošuta, Ispila, and others [

6]. Skadar Lake is fed by the Morača River and its tributaries, the Crnojević River, numerous smaller rivers in the surrounding area, and sublacustrine springs [

5].

The area of Skadar Lake National Park includes biotopes of water bodies, wetland vegetation, floodplain meadows and forests, scrublands, and rocky terrains. It has been determined that 930 species of algae are present in the lake [

6]. While endemic plant species are rare in the lake itself, the surrounding areas are rich in them, with the ecosystems of the Prokletije, Rumija, and Lovćen mountains containing over 50% of the total number of Balkan endemics [

5]. Research indicates that the lake hosts 45 species of fish, classified into 17 families. Skadar Lake is also an internationally significant gathering center for ornithofauna, with 279 bird species residing in or migrating through the lake, either temporarily or permanently [

6].

On the territory of Skadar Lake National Park, multiple findings from the Mediterranean Neolithic period have been discovered. One example is Dučića Cave, located on the northern edge of the Skadar basin, above the villages of Peuta and Gornja Vrbica, where various weapons and tools were found, including a flint knife and a polished axe [

9]. The early Bronze Age saw the emergence of fortified settlements (gradine) such as Međeđa Glava and numerous tumuli. Particularly significant remains from this period include the Illyrian settlement of Meteon-Medun (late 4th century BC – early 3rd century BC), the fortress of Samobor above Skadar Lake (3rd century BC), burial sites in Momišići, and the necropolis in Gostilj. The most significant archaeological site from the Roman period is Doclea (Duklja), near present-day Podgorica, which was founded by the Romans in the 1st century AD and granted municipal status. In addition to Doclea, several other cities existed in antiquity, including Alata (Halata), Birziminium, Skadar, Gajtan, Kodra, and Gradac [

6].

From the cultural and historical heritage, several religious structures from different periods stand out: the Monastery of Prečista Krajinska, located 22 km from Virpazar, near the village of Ostros (11th century); the Kom Monastery (15th century) (Prekić, 2020, 92, 165); as well as the remains of Žabljak (15th century) and Obod (15th century). At Obod, according to historical documents, the first Cyrillic printing house of the South Slavs began operating in 1493, making it the second Cyrillic printing house in Europe after the Krakow printing house [

6]. Skadar Lake National Park extends across the municipalities of Podgorica, Cetinje, and Bar. It serves as a unique natural classroom while also representing an area with great potential for the development of sports, hunting and fishing, excursion, transit, religious, and cultural tourism.

As tourism in Montenegro continues to grow, understanding the perceptions of local communities regarding tourism development and resilience becomes critical [

11,

12,

13]. The sustainable development of these national parks depends not only on their natural and historical significance but also on the engagement of local populations. Tourism development in protected areas is often examined through the lens of sustainable tourism frameworks, which emphasize the balance between environmental conservation, economic growth, and local community involvement [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Theories such as the Community-Based Tourism (CBT) model highlight the importance of resident participation in tourism planning, suggesting that successful tourism development depends on the inclusion of local stakeholders in decision-making processes [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Applying these theoretical perspectives to the case of Skadar Lake and Durmitor National Parks will help contextualize the study’s findings within broader sustainable tourism discourse.

While previous research has extensively examined the economic and environmental impacts of tourism in protected areas [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30], limited studies have focused on how local residents perceive tourism development and their role in shaping its outcomes [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. Understanding these perceptions is essential for developing sustainable tourism models that prioritize community involvement and resilience [

36,

37,

38,

39].

This study aims to provide an in-depth analysis of how local communities perceive tourism development and resilience in Skadar Lake and Durmitor National Parks. It focuses on understanding residents’ perspectives on tourism, examining the influence of socio-demographic factors—such as gender, age, and education—on these perceptions, and assessing the broader effects of tourism development on community resilience. Furthermore, the research investigates the degree to which local residents participate in tourism-related decision-making processes. By addressing these gaps, this research aims to contribute to the growing body of literature on sustainable tourism development by providing policy recommendations that ensure inclusive and community-centered tourism strategies. The findings will serve as a valuable resource for local governments, tourism stakeholders, and conservation organizations in designing tourism models that align with the interests and well-being of local residents [

40,

41,

42,

43].

1.1. Literature Review

Many researchs examining the relationship between tourism development and nature conservation emphasize the complex challenge of achieving a balance between economic expansion and environmental preservation [

17,

25,

44,

45,

46]. It can be said that researchers have explored various sustainable tourism models, highlighting the necessity of integrating environmental protection measures into tourism policies to mitigate adverse effects [

17,

45,

46,

47,

48]. The United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) has also emphasized the role of responsible tourism, advocating for policies that promote biodiversity conservation while simultaneously fostering economic benefits for local communities [

49,

50,

51]. On the other side, different researchs conducted across different regions, including national parks in North America, Europe, and Asia, suggests that well-regulated tourism, combined with active participation of local communities in decision-making, can serve as an effective tool for conservation [

13,

17,

28,

31,

45,

46,

49,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55].

Another critical aspect addressed in the literature is the influence of governance and policy frameworks on the relationship between tourism and conservation [

56,

57,

58,

59]. Studies on protected areas in Australia and Canada reveal that collaborative governance—where government agencies, local communities, and private sector stakeholders work together—often leads to more successful conservation efforts [

60,

61,

62,

63]. On the other hand, research focusing on rapidly growing tourism markets, such as those in Southeast Asia, underscores the challenges associated with unregulated tourism expansion, including habitat destruction and over-tourism [

64,

65,

66,

67]. These findings highlight the importance of policy-driven approaches that align conservation objectives with the principles of sustainable tourism.

In Europe, studies examining tourism’s impact on protected areas emphasize the necessity of adaptive management strategies that can respond effectively to evolving environmental and social conditions [

16,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73]. Despite the considerable progress made in sustainable tourism research, scholars continue to debate the long-term feasibility of tourism in ecologically sensitive areas. While some argue that sustainable tourism can function as a conservation tool, others warn that an increase in tourist activity inevitably exerts pressure on the environment if not carefully regulated [

27,

74,

75,

76]. This ongoing discourse reinforces the importance of continuous monitoring and flexible policy adjustments to ensure that tourism development does not compromise the ecological integrity of protected areas.

Also, research on the relationshi

p between nature conservation and tourism development remains relatively limited, with only a few authors exploring this complex issue [

45,

46,

48,

77]. The perceptions of local residents regarding tourism development are influenced by various socio-demographic factors, such as age, gender, and education level [

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84]. These factors shape attitudes toward tourism’s benefits and challenges, as well as the willingness of residents to engage in decision-making processes. By analyzing these dimensions, this study aims to provide a deeper understanding of the complexities involved in tourism affirmation within national parks.

Existing research on community-based tourism highlights the significance of local participation in tourism planning as a means to enhance economic benefits while minimizing cultural and environmental disruptions [

42,

85,

86,

87]. However, in the context of Montenegro’s national parks, there is a lack of empirical data on how local communities perceive and interact with tourism development [

5,

6,

8,

10,

88]. This study seeks to bridge that gap by focusing on Durmitor and Skadar Lake National Parks.

One of the pioneering studies in this area was conducted by Nikolić [

7], who examined the interdependence between nature protection and tourism, emphasizing the role of ecological conservation as a prerequisite for the long-term development of tourism in Montenegro. Expanding on this perspective, Radović [

88] provided a concise overview of ecological protection in tourist areas, focusing on the necessary conditions for achieving sustainable and high-quality tourism development.

A more localized approach was taken in the research of Radosavović [

89], whose analyzed the role of tourism in the development of Plužine municipality. The findings revealed a three-tiered pattern of participation among local residents: some directly engage in tourism, others are indirectly involved, while a portion of the population does not participate at all. Moreover, the study highlighted both positive and negative effects of tourism on the local community, emphasizing that the local population is highly interested in tourism development and well aware of the region’s tourism potential. The study also found that residents are open to collaboration with local authorities and tourism professionals, suggesting a strong foundation for participatory tourism planning [

89].

When analyzing similar studies in neighboring countries, the research conducted in the Mura-Drava Regional Park examined the perspectives of local and regional tourism organizations on community involvement in tourism development. The results confirmed that local tourism stakeholders recognize the essential role of local residents in the development of sustainable tourism [

90].

Further supporting the significance of community engagement, a study on local support for tourism development in Istria employed regression analysis to assess key determinants influencing resident attitudes. The results indicated that residents’ perceptions and attitudes toward tourism are crucial factors shaping their level of support, regardless of socio-demographic differences. These findings underscore the importance of tourism planning that aligns with the needs and expectations of the local population [

91].

Additionally, research on resident attitudes toward tourism development in Vrbas identified notable differences based on employment status, gender, and occupation. Unemployed individuals were particularly supportive of tourism development, while young people demonstrated strong enthusiasm for tourism initiatives [

92]. The study also revealed that while residents generally support tourism development, they are often unaware of the region’s full tourism potential. Notably, the perceived negative impacts of tourism received lower ratings, suggesting that residents may not be fully aware of potential challenges associated with tourism growth [

92].

Collectively, these studies highlight the multifaceted relationship between tourism development and local community engagement. While there is a strong recognition of tourism’s economic and social benefits, there remains a gap in awareness regarding potential negative consequences. This underscores the need for inclusive tourism policies that not only capitalize on local knowledge and engagement but also address sustainability concerns and community well-being.

2. Methods

This study aims to critically assess how local populations perceive tourism development and resilience in Skadar Lake and Durmitor National Parks. Specifically, it seeks to explore residents’ attitudes toward tourism, investigate how socio-demographic factors—such as gender, age, and education—shape these perceptions, and evaluate the broader implications of tourism development on community resilience. On the other side, this study is guided by the conceptual framework of sustainable tourism and community engagement [

93,

94,

95,

96,

97], which suggests that local populations play a crucial role in shaping tourism policies and ensuring the long-term viability of tourism-based economies. By integrating socio-demographic variables into the analysis, this research aims to provide a nuanced understanding of how different groups perceive tourism development and resilience in national parks. The formulated hypotheses, therefore, seek to explore the relationships between demographic characteristics and attitudes toward tourism, as well as the extent of local involvement in tourism decision-making. Additionally, the study examines the extent to which local residents are engaged in tourism-related decision-making processes. To achieve these objectives, the research is guided by the following key questions:

What are the prevailing attitudes of local residents toward tourism development in Skadar Lake and Durmitor National Parks?

In what ways do socio-demographic characteristics influence these perceptions?

To what extent are local communities involved in decision-making processes related to tourism?

Based on the objectives of this study and the conducted multiple regression analysis, the following hypotheses have been formulated to explore the relationship between socio-demographic factors and local residents’ perceptions of tourism development, as well as their involvement in decision-making processes:

Hypothesis 1: Tourism development has a measurable impact on local communities, with socio-demographic factors such as education, gender, and age playing a key role in shaping this influence.

Hypothesis 2: Local residents are not sufficiently involved in tourism development processes, and their level of engagement is largely influenced by socio-demographic characteristics.

Hypothesis 3: Higher levels of education are positively associated with a more supportive attitude toward tourism development.

Hypothesis 4: Local communities play a crucial role in promoting tourism in Skadar Lake and Durmitor National Parks, with education being a significant factor in shaping their perceptions.

These hypotheses provide a foundation for analyzing the impact of key demographic variables on residents’ attitudes and their role in sustainable tourism development.

2.1. Study Area

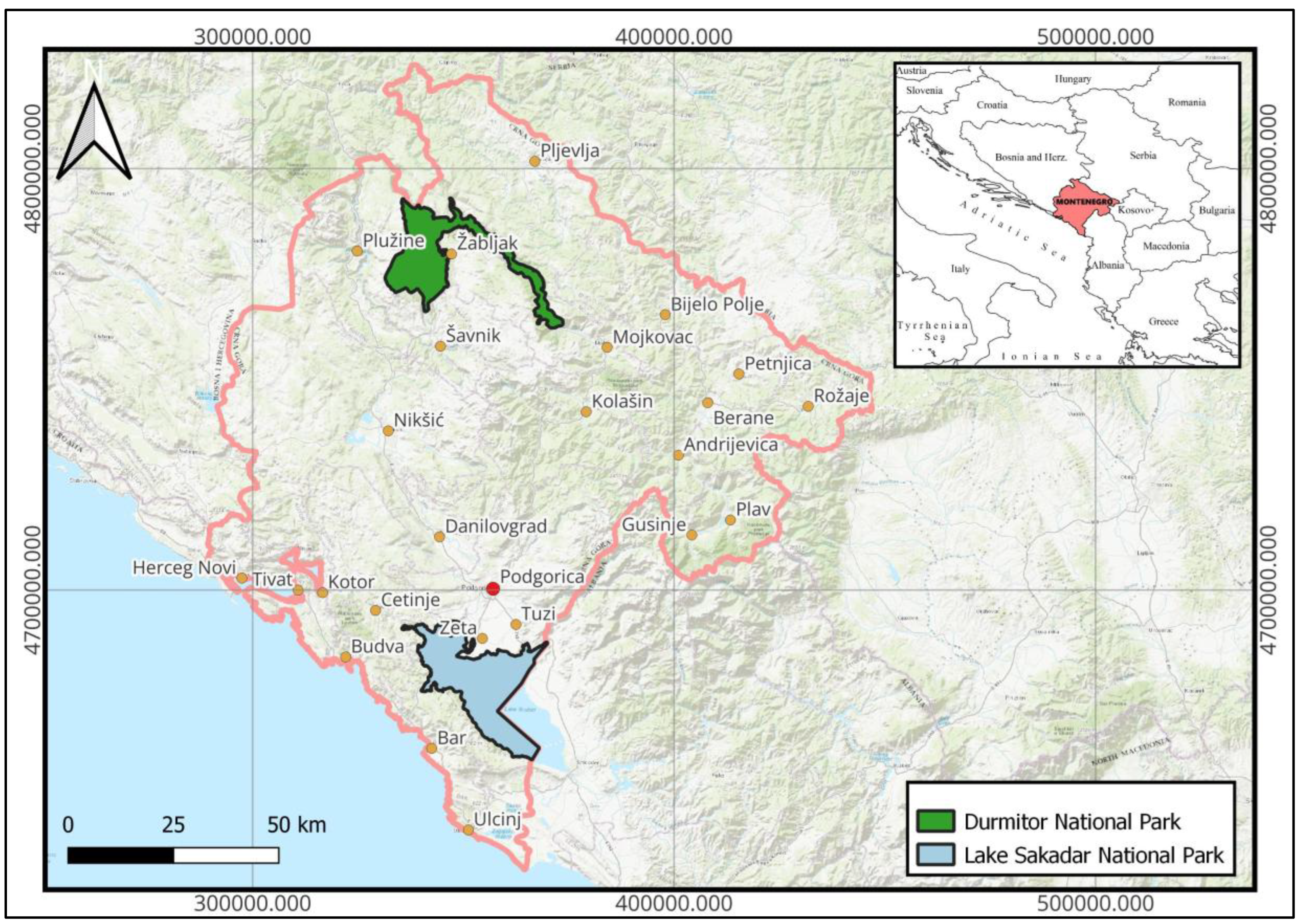

The selection of these areas (Durmitor and Skadar Lake National Parks in Montenegro) for study stems from their specific characteristics (

Figure 1). These are regions rich in natural and anthropogenic tourism values, subject to a certain degree of protection, yet still not fully developed as tourist destinations. This suggests that merely possessing well-preserved natural beauty and a rich cultural-historical heritage does not necessarily equate to developed tourism. Rather, it represents only the first ste

p in the complex process of tourism affirmation.

National Parks Durmitor and Skadar Lake exhibit noticeable differences. N

P Durmitor is the largest national park in Montenegro, located in the northern region, and is most renowned for its unique relief. Additionally, its climatic and hydrological characteristics, as well as the richness and diversity of its flora and fauna, contribute to a distinct and recognizable natural entity. In contrast, N

P Skadar Lake is situated in central Montenegro and encompasses numerous geological, geomorphological, climatic, and cultural-historical features. However, the greatest value of the park lies in its wealth of clean water and the diversity of its plant and animal life [

5].

2.2. Sample Characteristics

The study employs a structured survey methodology, with data collected from residents of communities surrounding Skadar Lake and Durmitor National Parks. A stratified random sampling technique was used to ensure a representative distribution across different age groups, genders, and education levels. The questionnaire consisted of Likert-scale items measuring perceptions of tourism development, community involvement, and socio-demographic characteristics.

Table 1 presents the distribution of the sample based on three key demographic variables: gender, age, and education. These variables are essential for understanding the characteristics of respondents and provide a foundation for a deeper analysis of their attitudes and perceptions within the study.The study included 500 respondents, of whom 217 were men (43.4%) and 283 were women (56.6%). This ratio indicates a slight predominance of female respondents, which may have implications for the analysis of gender-based differences in attitudes. Regarding age structure, the largest proportion of respondents belongs to the 26–35 age grou

p (38.2%), followed by those aged 36–45 (18.0%). The least represented groups are respondents younger than 18 years (9.2%) and those older than 56 years (8.8%). This distribution suggests that the majority of respondents are in their working-age years, which is relevant for contextualizing their perspectives. In terms of education, the highest percentage of respondents hold a higher education degree (47.4%), while 42.8% have completed secondary education, and 9.8% have only completed primary education. These findings indicate that the majority of respondents have a high level of education, which may influence their attitudes and understanding of the study topics. This demographic analysis provides essential information about the sample and offers deeper insights into the structure of the population surveyed. The higher proportion of highly educated respondents and the dominant age grou

p of 26–35 years suggest that the study findings will likely reflect the views of these groups. Additionally, the slight predominance of female respondents allows for a comparative analysis of gender-based attitudes. These demographic characteristics are crucial for the accurate interpretation of the research results.

2.3. Questionnaire Design

The process of questionnaire development involved several key steps to ensure its validity and reliability (

Appendix A). Initially, a pilot study was conducted on a small grou

p of respondents similar to the target population to identify and correct potential issues in question comprehension and instructions. Following this, the reliability of the questionnaire was assessed using statistical methods, such as Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, to ensure internal consistency within thematic sections. The validation process was also carried out to confirm that the questionnaire accurately measured the intended constructs through content and construct validity assessments. Based on these evaluations, the questionnaire was revised and finalized before being distributed to the target population for the main study. This approach ensured that the questionnaire serves as a reliable tool for collecting relevant data aligned with the research objectives.

The introductory section of the questionnaire is designed to collect basic demographic and socio-economic characteristics of respondents, allowing for a deeper analysis of data from the main research section. This part includes questions covering gender, age structure, and education level of respondents.

The first question in this section pertains to gender, where respondents choose between the options “male” or “female”. This information allows researchers to analyze gender-based differences in attitudes toward tourism. The second question addresses age structure, with categories “under 18,” “18-25,” “26-35,” “36-45,” “46-55,” and “56 and older.” These data are crucial for identifying age-related differences in perceptions of tourism and its impacts on the local community. The third question focuses on education level, with options including “primary education,” “secondary education,” and “higher education.” This information enables researchers to examine how educational background influences attitudes toward tourism, particularly its economic and cultural impact on the community. By collecting these demographic and socio-economic data, researchers can gain a more detailed understanding of how different respondent groups perceive tourism and its development in their region, as well as how these attitudes vary based on gender, age, and education level.

The main section of the questionnaire is designed to explore local residents’ attitudes toward the impact of tourism on their community, their involvement in tourism development, and their perception of tourism’s future in their area. This section is divided into several thematic units, each containing a series of statements rated on a five-point Likert scale, where 1 means “strongly disagree” and 5 means “strongly agree.”

The first thematic unit examines the impact of tourism on the local community, exploring how residents perceive changes in culture, traditions, and the environment as a result of tourism development. This section also includes questions about negative aspects of tourism, such as degradation of cultural and historical heritage and threats to biodiversity, as well as positive aspects, such as increased employment opportunities and community income growth.

The second thematic unit focuses on local residents’ involvement in tourism development. This section examines whether residents were consulted in tourism-related decision-making and to what extent they were active participants in the creation of tourism projects. Questions assess how much local residents’ suggestions were considered and whether their participation in the tourism development process was adequate.

The third thematic unit covers attitudes toward tourism promotion, exploring whether residents want their area to be recognized as a tourist destination, whether they see tourism as a potential industry for the future, and whether they would personally engage in the tourism sector.

The final thematic unit focuses on perceptions of the significance of local residents in tourism development. This section examines the extent to which respondents believe that local residents are a key component in tourism growth and whether they think that their opinions and knowledge about the local community should be respected in the planning and implementation of tourism activities. These questions emphasize the role of local expertise and knowledge in preserving authenticity and ensuring the successful development of tourism.

2.4. Analyses

In this study, various statistical methods were applied to gain a comprehensive understanding of local residents’ attitudes toward tourism development in Skadar Lake National Park and Durmitor National Park. The analyses included multiple linear regression, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and Pearson correlation, with all key assumptions for each method carefully verified. Reliability testing was conducted using Cronbach’s alpha to ensure the internal consistency of the survey items, while multiple regression analysis was applied to examine the impact of independent variables (gender, age, education) on local residents’ perceptions of tourism.

Multiple regression analysis was used to examine the effects of several independent variables, including gender, age, and education, on different aspects of tourism perception. The dependent variables included mean scores of attitudes toward tourism development, such as the impact of tourism on local residents, the involvement of local communities in tourism development, and perceptions of tourism affirmation. Before conducting the regression analysis, key assumptions were tested, including the linear relationship between independent and dependent variables, homoscedasticity, normality of residuals, and the absence of multicollinearity. These analyses helped identify the key predictors that significantly influence local residents’ attitudes.

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to examine differences in perceptions among respondents with different levels of education. This method allowed for the identification of variables that significantly differentiate groups in terms of their attitudes toward tourism. Before conducting the ANOVA test, assumptions regarding the normality of distributions and homogeneity of variances were tested to ensure the reliability of the results.

Pearson correlation was used to assess the relationship between respondents’ age and their attitudes toward various aspects of tourism development. This analysis helped identify statistically significant correlations between age and perceptions, providing insight into how age influences attitudes toward tourism. As with previous analyses, assumptions regarding the linear relationship between variables and the absence of extreme values that could affect results were carefully tested.

All these statistical analyses provided a detailed insight into local residents’ attitudes toward tourism, identifying key factors that shape these attitudes and enabling the formulation of recommendations for improving tourism development in these national parks..

3. Results

In this study, multiple regression analysis was used to examine the effects of independent variables on local residents’ perceptions of various aspects of tourism development (

Table 2). The dependent variables were the mean values of four hypotheses related to different aspects of tourism: a) tourism development has certain impacts on local residents; b) local residents are insufficiently involved in tourism development; c) local residents have a positive attitude toward tourism affirmation; d) local residents are a significant component of the tourism affirmation of N

P Skadar Lake and Durmitor. The analysis was conducted using the standard procedure of multiple regression analysis, where independent variables (gender, age, and education) were used to predict dependent variables (hypotheses). Each model was evaluated based on regression coefficients (B), standardized coefficients (

β), standard errors (SE), and other values indicating the percentage of variance explained in the dependent variables. This approach provided a detailed insight into how each predictor contributes to changes in local residents’ attitudes toward tourism.

The analyses show that for the hypothesis “Tourism development has certain impacts on local residents,” the analysis indicates that education (β = 1.056, p = 0.291) has a positive but not statistically significant impact. In contrast, gender (β = −1.858, p = 0.064) and age (β = 0.723, p = 0.470) also do not have a statistically significant impact in this model. This regression model (R² = 0.009, Adj. R² = 0.003, F = 4.41, t = 17.49, p > 0.05) explains 0.9% of the variance in the perceived impacts of tourism development on local residents.

For the hypothesis “Local residents are insufficiently involved in tourism development,” education (β = 1.693, p = 0.091) and gender (β = 1.632, p = 0.104) have a positive but not statistically significant impact, while age (β = 0.432, p = 0.665) also does not show a statistically significant impact. This regression model (R² = 0.014, Adj. R² = 0.008, F = 4.20, t = 7.20, p > 0.05) explains 1.4% of the variance in the insufficient involvement of local residents in tourism development.

In contrast, for the hypothesis “Local residents have a positive attitude toward tourism affirmation,” education (β = 2.643, p = 0.009) shows a statistically significant positive impact, while gender (β = −0.304, p = 0.761) and age (β = 0.245, p = 0.622) do not show a statistically significant impact. This regression model (R² = 0.014, Adj. R² = 0.008, F = 3.15, t = 14.46, p < 0.05) explains 1.4% of the variance in local residents’ positive attitudes toward tourism affirmation.

Finally, for the hypothesis “Local residents are a significant component of the tourism affirmation of NP Skadar Lake and Durmitor,” education (β = 2.714, p = 0.007) shows a statistically significant positive impact, while gender (β = 2.331, p = 0.022) has a positive but marginally significant impact. Age (β = −1.051, p = 0.293) does not show a statistically significant effect. This regression model (R² = 0.031, Adj. R² = 0.025, F = 3.15, t = 14.73, p < 0.05) explains 3.1% of the variance in the perception of local residents as a significant component of tourism affirmation. These results indicate that education has a consistent and statistically significant positive effect on local residents’ perceptions in some models, while gender and age are less significant factors.

The results of the Pearson correlation between age and respondents’ attitudes toward tourism, presented in

Table 3, reveal several significant findings. First, the correlation between age and the belief that “tourism development has negative impacts on local residents because it changes local culture and tradition” shows a positive and statistically significant relationshi

p (r = 0.096,

p = 0.031). This indicates that older respondents are slightly more inclined to perceive tourism as a threat to local culture and tradition.

Similarly, the belief that “tourism development changes traditional behavioral patterns among local residents” also exhibits a positive and statistically significant correlation with age (r = 0.090, p = 0.045). This suggests that older respondents are more likely to believe that tourism alters traditional behavioral patterns.

On the other hand, significant negative correlations were found for the attitudes that “tourism development stimulates investment in the local community” (r = -0.131, p = 0.003) and that “tourism development encourages infrastructure construction” (r = -0.118, p = 0.008). These results imply that older respondents are less likely to believe that tourism positively impacts investment in the community and infrastructure development.

Most of the other correlations are not statistically significant, suggesting that age does not play a major role in shaping attitudes toward most aspects of tourism among respondents. For example, the attitudes that “tourism development positively affects the preservation of cultural and historical heritage” (r = -0.066, p = 0.139) and “tourism development increases employment opportunities” (r = -0.070, p = 0.120) are not statistically significant.

In conclusion, the results suggest that older respondents generally hold slightly more critical views on the negative aspects of tourism but are less convinced of its positive effects on investment and infrastructure. However, these effects are relatively mild, as seen in the low correlation coefficient values (

Table 3).

Results of descriptive statistical analyses, presented in

Table 4, shed light on various aspects of local residents’ perceptions of the impact of tourism on their community. Descriptive statistics indicate that a majority of respondents view tourism as beneficial for economic development but express concerns over environmental degradation and limited community participation in decision-making. The average rating for the statement that tourism development has negative consequences for local residents, particularly due to changes in local culture and tradition, is M = 2.24, indicating relatively low agreement with this claim. Similarly, the statements that tourism changes traditional behavior patterns (M = 2.51) and damages the environment (M = 2.54) also have low average ratings, suggesting that local residents do not perceive tourism as highly harmful.

On the other hand, statements regarding the positive impacts of tourism have higher average ratings. For example, the perception that tourism brings greater employment opportunities has an average rating of M = 3.95, while the statement that tourism contributes to the income growth of the local community is rated at M = 3.91. Additionally, the belief that tourism stimulates infrastructure development received an average rating of M = 3.84.

It is noteworthy that statements related to local residents’ involvement in decision-making and planning of tourism activities received lower average ratings, such as “Our suggestions and opinions were considered regarding the tourism development of our local community” (M = 2.26) and “Local residents were involved in the development of the tourism project” (M = 2.26). These results suggest that local residents feel insufficiently involved in the tourism development process.

Conversely, statements regarding the importance and knowledge of the local community have high average ratings, such as “Local residents know their community best” (M = 4.05) and “The opinions of local residents must be respected” (M = 4.02). These high ratings indicate a strong perception that local knowledge is crucial for the successful development of tourism.

These results provide insights into local residents’ attitudes toward tourism, highlighting both the positive and negative aspects they perceive regarding tourism development in their community (

Table 4).

In addition to the previously described variables, several additional factors further illuminate local residents’ attitudes toward tourism. For example, the statement that the degradation of cultural and historical heritage is a consequence of tourism development received an average rating of M = 2.41, indicating that residents generally do not believe tourism has a significant negative impact on cultural heritage preservation. Similarly, the perception that tourism threatens biodiversity was rated M = 2.61, suggesting mild concern, but not to a great extent.

Local residents moderately believe that tourism development requires an intact environment and can contribute to its protection, with an average rating of M = 3.64. However, there is somewhat less satisfaction with local government support for tourism, as shown by an average rating of M = 2.9 for the statement that local government or the state provides adequate support. In terms of mutual solidarity, residents help each other in tourism-related activities (M = 3.12), while there is moderate agreement with the claim that local products are utilized in creating tourism offerings (M = 3.28).

Regarding consultations with local authorities, the statement that residents were consulted in planning activities related to tourism development received an average rating of M = 2.55, indicating partial involvement in the process. On the other hand, there is a strong desire for their community to be recognized as a tourist destination (M = 3.88) and a firm belief that tourism can bring significant benefits to the local community (M = 3.93).

Additionally, there is a moderate but significant interest among local residents in engaging in tourism-related activities (M = 3.52) and a strong belief that tourism is an industry of the future (M = 3.77). Finally, the statement that local residents receive tourism-related education obtained an average rating of M = 3.12, indicating moderate agreement, but also a need for further education and skill development in this field. These additional results complement the existing understanding of local residents’ attitudes, highlighting the complexity of perceptions related to tourism development in their community.

Further research findings indicate significant differences in local residents’ perceptions between Skadar Lake National Park and Durmitor National Park regarding the impacts of tourism. Overall, respondents from Durmitor National Park were more inclined to highlight both the positive and negative aspects of tourism compared to those from Skadar Lake National Park. For example, the belief that tourism development alters local culture and tradition (M = 2.308) and negatively affects the environment (M = 2.600) received higher ratings among respondents from Durmitor National Park than those from Skadar Lake National Park (M = 2.176 and M = 2.472, respectively). Similarly, the perception that tourism development threatens biodiversity was also more pronounced among respondents from Durmitor National Park (M = 2.656) than among those from Skadar Lake National Park (M = 2.560).

On the other hand, positive effects of tourism, such as increasing local community income (M = 4.016) and stimulating investment in the community (M = 3.928), received slightly higher ratings in Durmitor National Park than in Skadar Lake National Park (M = 3.896 and M = 3.816, respectively). However, it is noteworthy that respondents from Skadar Lake National Park demonstrated greater enthusiasm for promoting their area as a tourist destination (M = 3.880) and expressed a stronger interest in engaging in tourism-related activities (M = 3.516) compared to respondents from Durmitor National Park (M = 3.736 and M = 3.352, respectively).

Regarding the involvement of local residents in decision-making processes and support from local authorities, differences were also observed. Respondents from Skadar Lake National Park rated their participation in the planning process and the consideration of their opinions higher (M = 2.352 and M = 2.264) compared to respondents from Durmitor National Park (M = 2.208 and M = 2.176). Conversely, support from local authorities and mutual assistance in tourism were rated slightly higher in Durmitor National Park (M = 3.012 and M = 3.232) than in Skadar Lake National Park (M = 2.904 and M = 3.124).

When considering attitudes toward local residents’ knowledge and the importance of their participation in tourism development, respondents from Durmitor National Park reported slightly higher ratings, particularly regarding the recognition of local residents’ opinions (M = 4.108) and their understanding of their community’s strengths and weaknesses (M = 4.104). However, interestingly, respondents from Skadar Lake National Park rated local residents’ education in tourism higher (M = 3.120) compared to respondents from Durmitor National Park (M = 2.892).

These findings indicate complex perceptions of tourism among residents of the two national parks, where Durmitor National Park exhibits more intense attitudes, both positive and negative. On the other hand, Skadar Lake National Park demonstrates greater enthusiasm for tourism promotion and participation in tourism development processes. These differences may be related to the specific socio-economic and cultural characteristics of each region, as well as the distinct experiences and challenges faced by these two destinations (

Table 5).

Based on the results of the one-way ANOVA analysis, a statistically significant effect of education level was determined on the following variables: tourism development has negative impacts on local residents because it changes local culture and tradition (

F = 3.49,

p = 0.03); tourism development increases employment opportunities (

F = 7.04,

p = 0.00); tourism development increases local community income (

F = 5.36,

p = 0.00); tourism development stimulates investment in the local community (

F = 4.79,

p = 0.01); tourism development encourages infrastructure construction (

F = 2.99,

p = 0.05); local residents are sufficiently involved in the tourism development process (

F = 3.33,

p = 0.04); I want my community to be recognized as a tourist destination (

F = 7.29,

p = 0.00); I believe that tourism development can bring significant benefits to my local community (

F = 3.61,

p = 0.03); every local resident is equally important for tourism development (

F = 4.04,

p = 0.02); the opinions of local residents must be respected (

F = 5.87,

p = 0.00); local residents receive tourism-related education (

F = 3.41,

p = 0.03) (

Table 6).

The results of the one-way ANOVA analysis confirm that education level significantly influences various aspects of tourism perception in the local community. Respondents with different levels of education perceive the negative effects of tourism on local culture and tradition differently (F = 3.49, p = 0.03), with respondents with lower education levels (high school) reporting more negative effects (M = 2.49, SD = 1.19) compared to those with higher education levels (M = 2.12, SD = 1.03).

Similarly, the perception that tourism increases employment opportunities (F = 7.04, p = 0.00) varies significantly, with respondents with higher education levels being more optimistic (M = 4.12, SD = 1.07) compared to those with lower education levels (M = 3.55, SD = 1.19). Likewise, the perception that tourism development increases local community income (F = 5.36, p = 0.00) was stronger among those with higher education (M = 4.24, SD = 1.05) than among those with lower education (M = 3.90, SD = 0.96).

The perception that tourism stimulates investment in the local community (F = 4.79, p = 0.01) also differs, with higher-educated respondents giving higher ratings (M = 3.91, SD = 1.10) compared to those with lower education (M = 3.55, SD = 1.19). A borderline statistical significance was found in the perception that tourism development encourages infrastructure construction (F = 2.99, p = 0.05), where those with higher education reported slightly higher scores (M = 3.48, SD = 1.29) than those with lower education (M = 3.38, SD = 1.20).

The perception of local residents’ involvement in the tourism development process (F = 3.33, p = 0.04) shows that respondents with higher education feel more involved (M = 3.48, SD = 1.29) compared to those with lower education (M = 3.38, SD = 1.20). Similarly, the desire for their community to be recognized as a tourist destination (F = 7.29, p = 0.00) is significantly stronger among respondents with higher education (M = 4.24, SD = 1.05) than among those with lower education (M = 3.90, SD = 0.96).

The perception of the benefits that tourism development can bring to the local community (F = 3.61, p = 0.03) also varies with education level, with higher-educated respondents placing greater importance on this aspect (M = 4.01, SD = 1.16) than those with lower education (M = 3.65, SD = 1.17). The perception that every local resident is equally important for tourism development (F = 4.04, p = 0.02) shows that those with higher education value equality in participation more (M = 3.49, SD = 1.17).

Respondents’ opinions on the recognition of local residents’ views in the tourism development process (F = 5.87, p = 0.00) significantly differ, with higher-educated respondents emphasizing the importance of respecting these views (M = 4.12, SD = 1.08). Finally, tourism-related education (F = 3.41, p = 0.03) is considered more important by respondents with higher education levels (M = 3.14, SD = 1.31), indicating greater awareness of the importance of education in this field.

These results suggest that education level significantly influences the perception of various aspects of tourism development in the local community, with higher-educated individuals generally having more positive attitudes and a greater degree of involvement in tourism-related activities.

The results of the independent samples t-test between gender and observed variables related to tourism impacts on the local community indicate statistically significant differences between male and female respondents for multiple variables. Male respondents are more likely to agree with the statement that tourism development negatively affects local culture and tradition (M = 2.39, SD = 1.13) compared to female respondents (M = 2.13, SD = 1.02), with this difference being statistically significant (

p = 0.008). Similarly, men perceive tourism development as a greater threat to biodiversity (M = 2.78, SD = 1.21) compared to women (M = 2.47, SD = 1.13), with a statistically significant difference (

p = 0.003) (

Table 7).

On the other hand, women are more inclined to agree that tourism development stimulates infrastructure construction (M = 3.95, SD = 1.08) compared to men (M = 3.74, SD = 1.1), with a statistically significant difference (

p = 0.034). Additionally, women express stronger agreement with the statement that local residents receive tourism-related education (M = 3.11, SD = 1.37) compared to men (M = 2.87, SD = 1.26), with a significant difference (

p = 0.046). However, men show a greater desire to engage in tourism-related activities (M = 3.59, SD = 1.17) compared to women (M = 3.31, SD = 1.29), which is also statistically significant (

p = 0.014). Conversely, women are more likely to believe that tourism is the industry of the future (M = 3.88, SD = 1.12) compared to men (M = 3.59, SD = 1.12), with a statistically significant difference (

p = 0.005) (

Table 7).

Women also place greater importance on inclusivity in tourism development, as they more strongly agree that every member of the local community must be considered in the tourism development process (M = 4.03, SD = 1.13) compared to men (M = 3.75, SD = 1.08), with a statistically significant difference (

p = 0.006). They also more strongly believe that local residents’ opinions must be respected (M = 4.17, SD = 1.08) compared to men (M = 3.92, SD = 1.06), with a significant difference (

p = 0.01). Finally, women agree more with the statement that local residents know the strengths and weaknesses of their community best (M = 4.18, SD = 1.08) compared to men (M = 3.92, SD = 1.03), with a significant difference (

p = 0.007) (

Table 7).

These results highlight significant gender-based differences in the perceptions of tourism impacts on various aspects of the local community, which could have implications for tourism policies and development strategies.

4. Discussion

This study explored various sociodemographic factors, such as gender, age, and education, to gain a comprehensive understanding of the elements shaping local residents’ attitudes toward tourism. By analyzing these variables, the study provides valuable insights into how different demographic groups perceive tourism’s benefits and challenges. The findings not only highlight existing perceptions but also offer a basis for anticipating potential obstacles and opportunities for sustainable tourism development. Understanding these attitudes is crucial for policymakers and tourism planners, as it enables the creation of tailored strategies that address the specific needs and concerns of diverse population segments [

3,

98,

99,

100].

Multiple regression analysis identified education as a key determinant of tourism perception, revealing that individuals with higher levels of education tend to exhibit more enthusiasm and support for tourism development. This aligns with broader research suggesting that education fosters awareness of the multifaceted benefits tourism brings, including economic growth, infrastructure development, and cultural exchange. Educated individuals typically have better access to reliable sources of information, allowing them to develop a more nuanced understanding of tourism’s long-term advantages [

101,

102,

103,

104].

The findings align with prior research emphasizing the role of education in shaping attitudes toward tourism development [

38,

101,

103,

104]. Higher education levels appear to be associated with increased awareness of tourism’s economic benefits, whereas lower educational attainment correlates with skepticism regarding tourism’s sustainability. These insights underscore the need for targeted community engagement initiatives that address concerns about cultural preservation while promoting the economic advantages of tourism [

20,

24,

31,

53,

54,

87]. Moreover, the results highlight the necessity for policymakers to develop more inclusive tourism planning frameworks that actively involve local residents in decision-making processes [

16,

19,

21,

42,

58].

Additionally, higher education levels correlate with greater civic engagement and participation in community initiatives. Educated individuals are more likely to advocate for policies that promote sustainable tourism practices, emphasizing environmental protection, cultural preservation, and economic inclusivity. This finding underscores the importance of investing in educational programs and community awareness campaigns to ensure that tourism development aligns with the broader interests of society [

38,

102,

103,

104].

Another important consideration is the role of lifelong learning and informal education [

105,

106]. Even among individuals with lower formal education levels, exposure to tourism-related training programs or informational campaigns can significantly improve their understanding of tourism’s benefits. Therefore, initiatives such as local workshops, public seminars, and digital literacy campaigns could help bridge the knowledge gap and foster more positive attitudes toward tourism across different educational groups [

104,

107,

108,

109,

110].

Age emerged as another critical factor influencing tourism perception, with older respondents expressing more skepticism regarding its impacts. This pattern is largely driven by a deep-rooted attachment to traditional lifestyles and concerns over cultural, environmental, and social disruptions caused by tourism [

111,

112,

113,

114]. Older residents often view tourism as a double-edged sword—while it brings economic benefits, it also introduces changes that may threaten local customs, traditions, and natural landscapes. In communities with strong cultural identities, tourism can sometimes be perceived as an external force imposing change rather than an opportunity for cultural revitalization [

115,

116,

117,

118]. Many older residents fear that tourism could lead to the commodification of cultural heritage, where traditions are altered to cater to tourists rather than preserved in their authentic form. Additionally, environmental concerns, such as increased pollution, resource depletion, and overcrowding, contribute to the skepticism observed among older age groups.

To mitigate these concerns, community engagement and participatory planning approaches are essential. Encouraging older residents to take active roles in shaping tourism policies can help address their apprehensions and ensure that tourism development aligns with local values [

31,

119,

120]. For example, integrating elder community members into cultural tourism initiatives—such as heritage storytelling programs or traditional craft workshops—could turn their knowledge and experience into valuable tourism assets while fostering greater acceptance of tourism within these communities [

121,

122,

123].

The findings further indicate significant variations in tourism perceptions based on education levels. One-way ANOVA analysis demonstrated that individuals with lower education levels are less likely to recognize tourism’s economic and social benefits, which may stem from limited access to information or a narrower understanding of tourism’s broader impacts. This underscores the crucial role of targeted awareness programs in bridging the informational divide between different demographic groups. A key strategy for addressing this gap is the development of educational initiatives that focus on tourism’s practical benefits for local communities [

103,

104,

109,

110]. For instance, emphasizing how tourism contributes to local job creation, infrastructure improvements, and economic diversification could help change perceptions among individuals with lower education levels [

52,

101,

102,

105,

107]. Additionally, partnerships between tourism organizations and local schools or community centers could facilitate knowledge-sharing programs that equip residents with the skills needed to actively participate in the tourism economy [

124,

125,

126,

127].

Importantly, digital platforms and social media can serve as powerful tools for increasing awareness [

128]. Many tourism development initiatives now incorporate digital outreach efforts, such as informative videos, interactive webinars, and online training sessions, to engage wider audiences [

129,

130,

131,

132]. By leveraging these tools, policymakers can ensure that even individuals with limited formal education have access to relevant information about tourism and its potential advantages [

133,

134].

Further analysis using Pearson’s correlation revealed a significant relationship between age and tourism perceptions, with younger respondents exhibiting more optimistic views compared to their older counterparts. Younger individuals often perceive tourism as an avenue for economic mobility, employment opportunities, and exposure to new cultures and experiences [

135]. Their openness to change makes them more receptive to tourism-driven developments, including modern infrastructure projects and business investments in the sector. However, generational differences in tourism perception also highlight the need for intergenerational dialogue in tourism planning. While younger individuals are more inclined toward innovation and modernization, older generations provide valuable insights into cultural heritage preservation and sustainable practices [

136,

137,

138]. A balanced approach that incorporates both perspectives can lead to tourism policies that respect local traditions while embracing economic and technological advancements.

One potential solution is the implementation of mentorship programs where younger and older community members collaborate on tourism-related initiatives. By fostering cross-generational cooperation, communities can ensure that tourism development is both progressive and culturally sensitive, ultimately creating a more harmonious and inclusive approach to local tourism management.

A comparative analysis between NP Skadar Lake and NP Durmitor revealed distinct differences in tourism perceptions. Residents of NP Durmitor expressed stronger opinions—both positive and negative—compared to those from NP Skadar Lake. This heightened awareness is likely due to the higher intensity of tourism in NP Durmitor, which has brought both economic gains and environmental challenges. Concerns over ecosystem degradation, over-tourism, and commercialization of natural resources have led some residents to adopt a more cautious stance on tourism expansion.

In contrast, respondents from NP Skadar Lake displayed greater enthusiasm for tourism development, possibly due to the region’s lower levels of tourism activity [

5,

88]. Many residents in this area view tourism as an untapped opportunity that could drive economic growth and infrastructure improvements. Their optimism suggests that, if properly managed, tourism could play a crucial role in enhancing local livelihoods while simultaneously promoting environmental conservation efforts [

60,

108].

Given these contrasting perspectives, a tailored approach to tourism development is necessary. In NP Durmitor, stricter environmental regulations and sustainable tourism policies should be enforced to address ecological concerns. Meanwhile, in NP Skadar Lake, investment in tourism infrastructure and capacity-building programs could help harness the potential benefits of tourism while ensuring long-term sustainability.

Despite providing valuable insights, this study has several limitations. The sample may not fully capture the diversity of the local population, and self-reported survey data could introduce response biases. Additionally, perceptions of tourism change over time, influenced by economic fluctuations, policy shifts, and global events such as pandemics. Future research should consider conducting longitudinal studies to track how tourism perceptions evolve.

Furthermore, expanding the study beyond NP Skadar Lake and NP Durmitor to include other regions in Montenegro or neighboring countries would offer a broader perspective on tourism’s social and economic impacts. Incorporating qualitative methods, such as in-depth interviews with stakeholders, could also provide richer insights into the underlying motivations and concerns of local residents.