Submitted:

22 April 2025

Posted:

24 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Foundation of Theory and Creation of Hypotheses

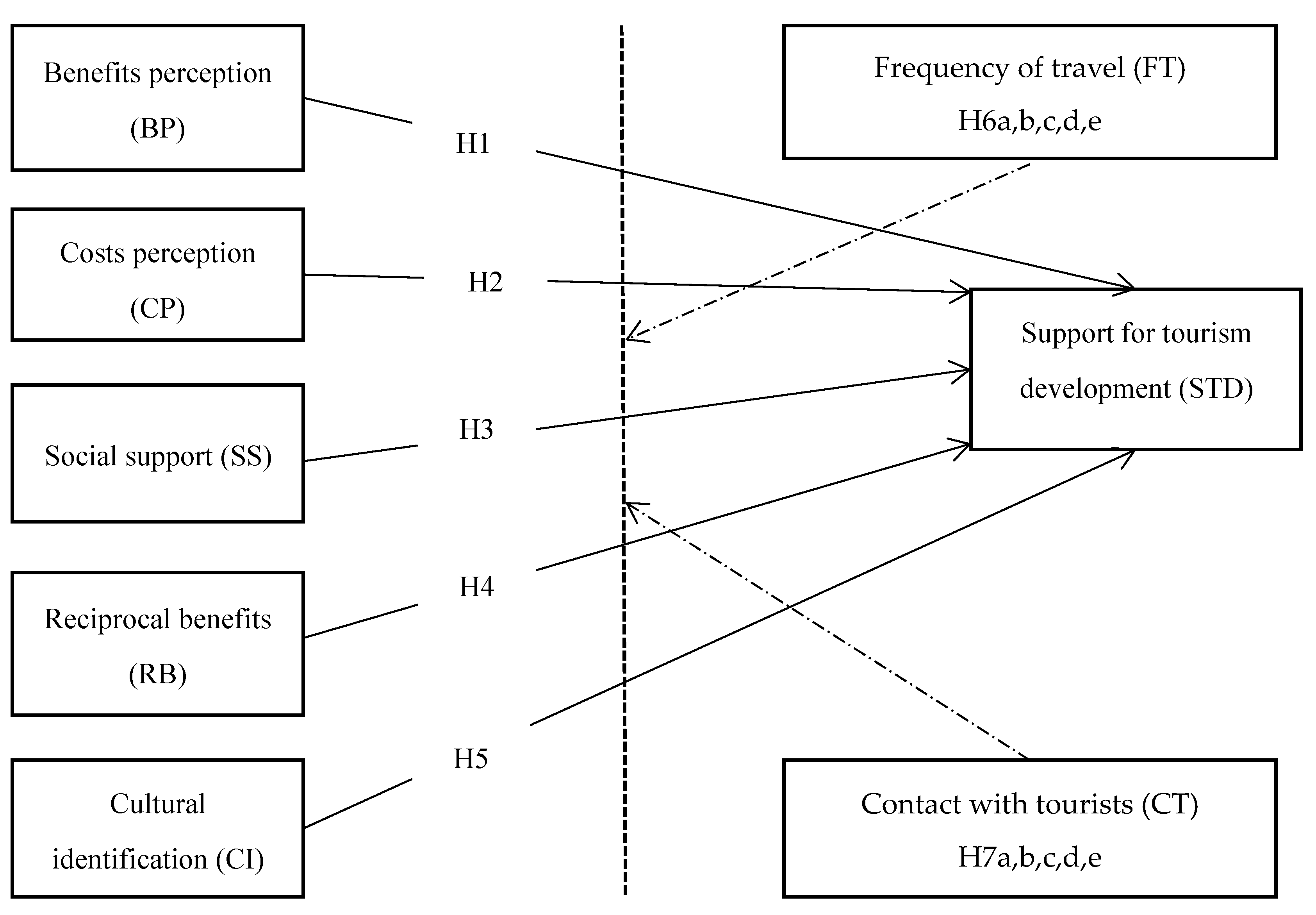

Development of Theoretical Model

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Procedure and Participants

3.2. Methodological Instrument

3.3. Data Processing and Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

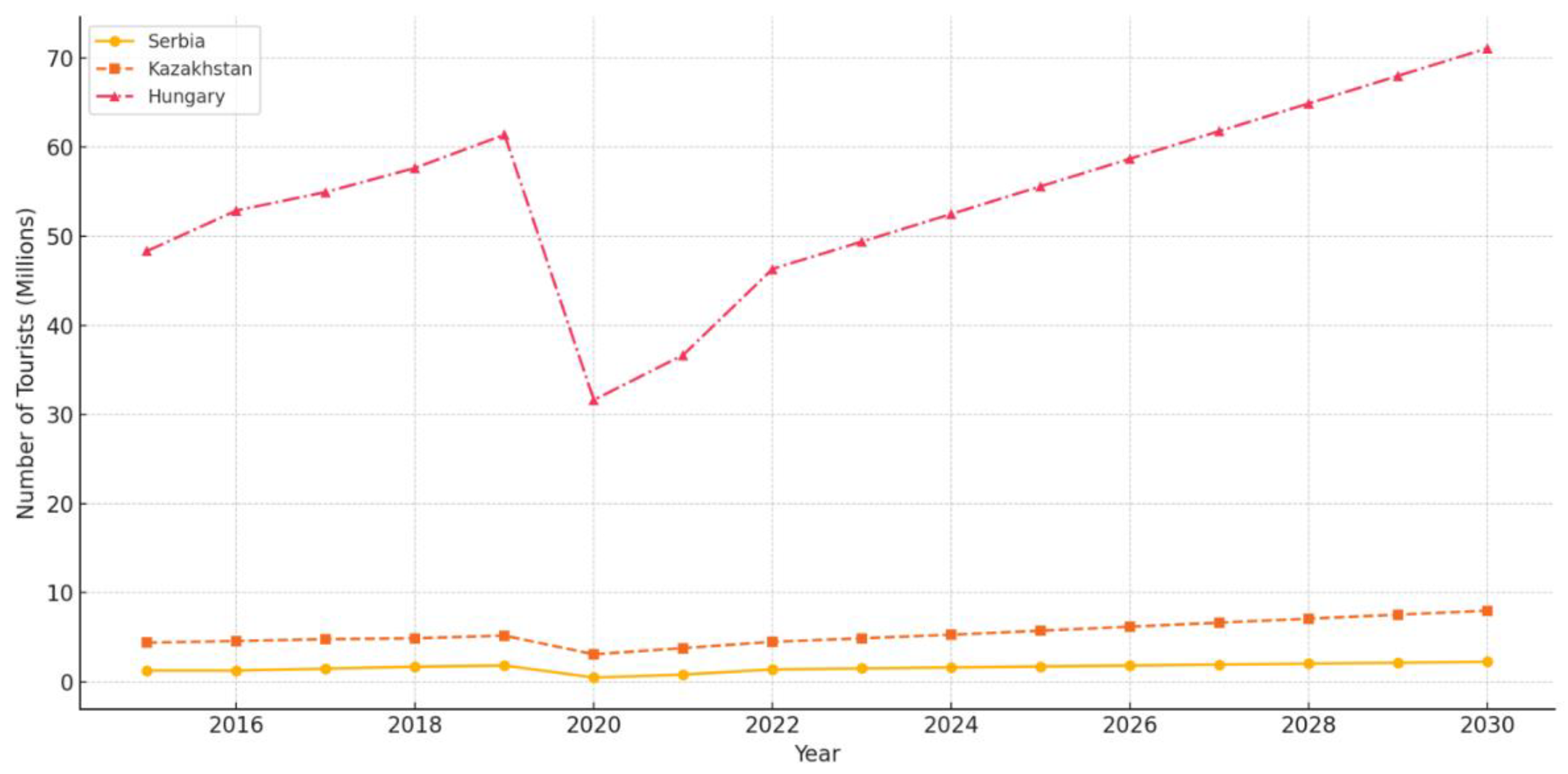

4.1. Trend Analysis and Tourism Growth Prediction

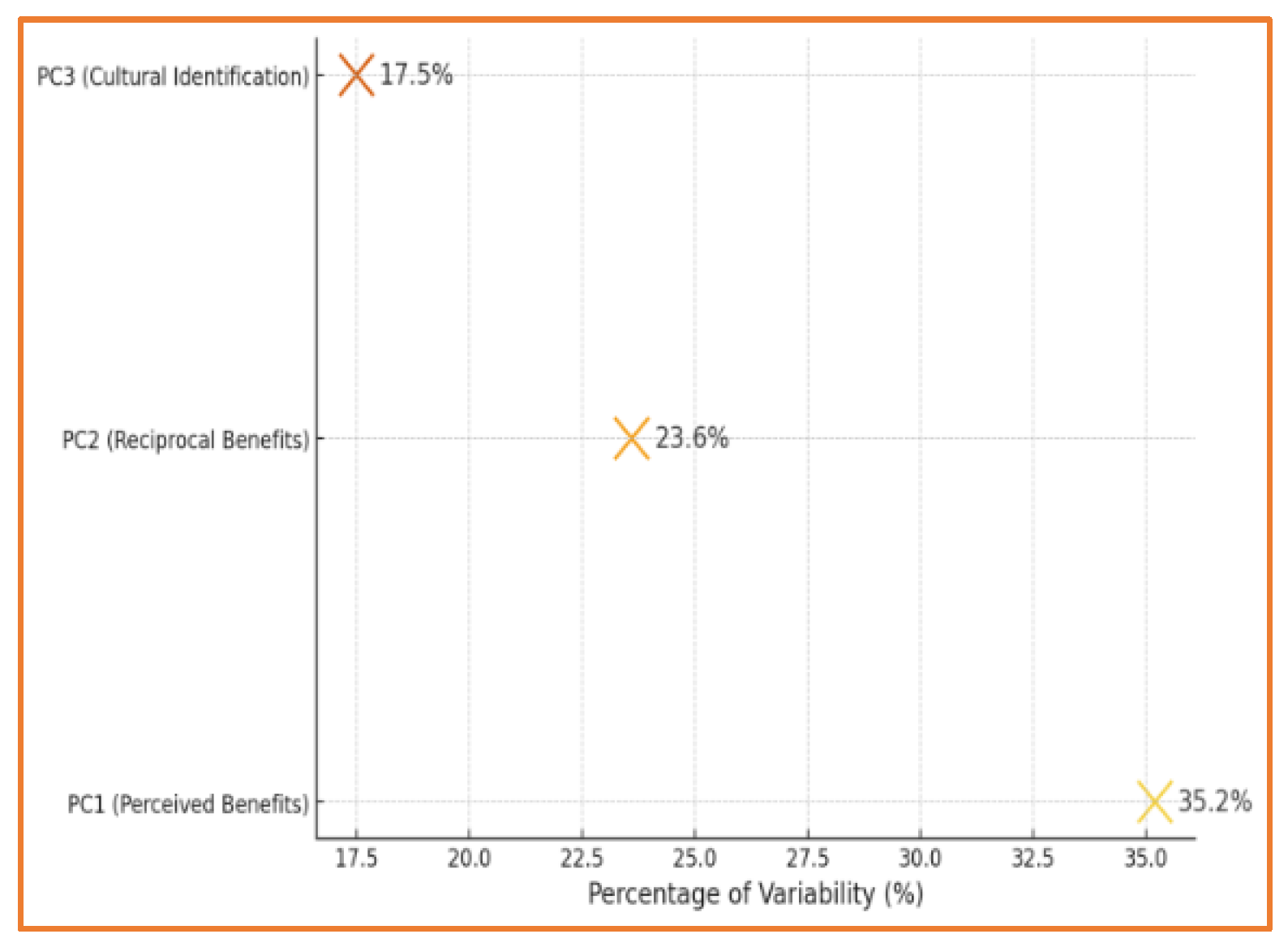

4.2. Descriptive and Factor Analysis

4.3. Correlation Analysis

4.4. SEM and MGA Analysis Findings

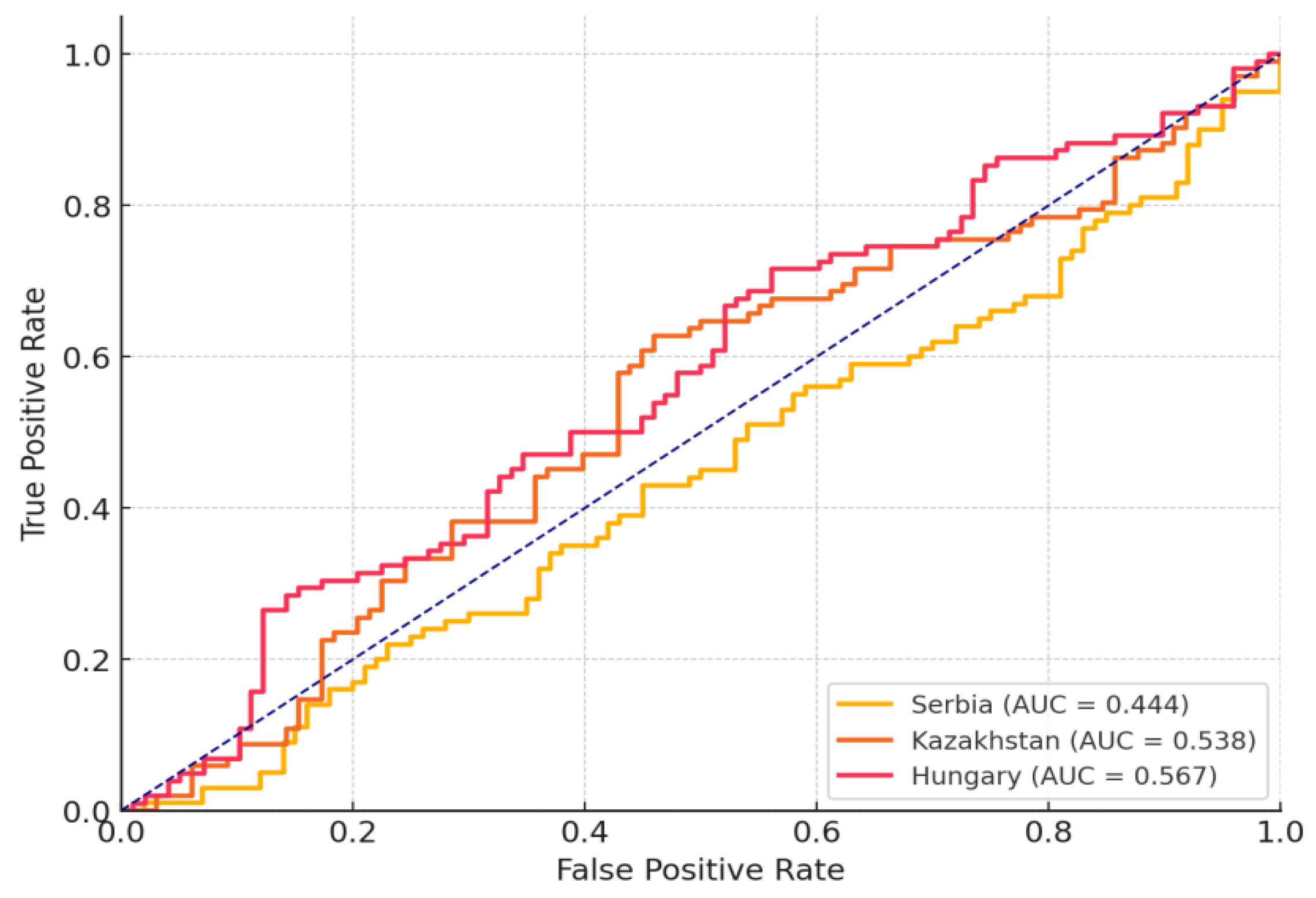

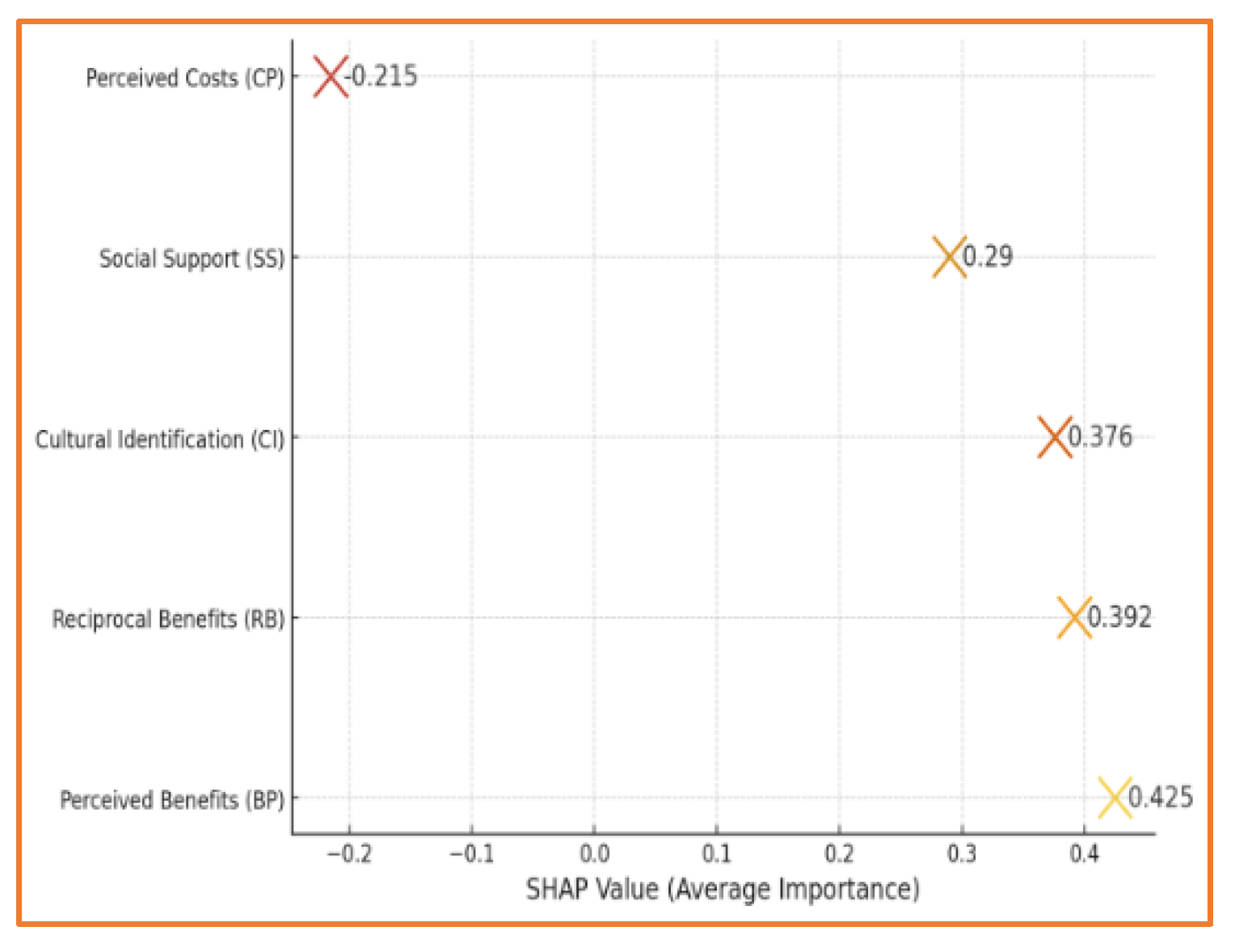

4.5. Prediction Model and Variable Importance Analysis

5. Conclusions

5.1. Conceptual and Applicable Implications

5.2. Study’s Limitations and Future Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gallegati, S.; Masiá, P.; Fanelli, E.; Danovaro, R. The Impact of Natural Capital Loss on Blue-Tourism Economy: The Red Sea Case Study. Mar. Policy 2025, 172, 106507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudarmanto, E.; Raharjo, B.B.; Kristiyanto, A.; Sulaiman, S.; Setyawati, H.; Priyono, B.; Jariono, G. A Systematic Review for the Development of Sustainable Tourism Destinations Based on Sports Tourism. Retos: nuevas tendencias en educación física, deporte y recreación 2025, 62, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernyshev, K.A.; Alov, I.N.; Li, Y.; Gajić, T. How Real Is Migration’s Contribution to the Population Change in Major Urban Agglomerations? J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijić SASA 2023, 73, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossini, L.; Falese, L.; Andrade, A.; Federici, D. Exploring the Socio-Economic Impact of Small and Medium-Sized Sports Events on Participants, Tourism and Local Communities: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Sport Tour. 2024, 28, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijatuyi, E.J.; Yessoufou, K.; Patrick, H.O. Sustainable Tourism and Green Space: Exploring How Green Spaces and Natural Attractions Contribute to Local Tourism Economies and Revenue Generation in Gauteng Province. Discover Sustainability 2025, 6, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirović, D.; Petrović, M.D.; Neto Monteiro, L.C.; Stjepanović, S. An Examination of Competitiveness of Rural Destinations from the Supply Side Perspective. J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijić SASA 2016, 66, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziekański, P.; Popławski, Ł.; Popławska, J. Interaction Between Pro-Environmental Spending and Environmental Conditions and Development. J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijić SASA 2024, 74, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Mamirkulova, G.; Al-Sulaiti, I.; Al-Sulaiti, K.I.; Dar, I.B. Mega-Infrastructure Development, Tourism Sustainability and Quality of Life Assessment at World Heritage Sites: Catering to COVID-19 Challenges. Kybernetes 2025, 54, 1993–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happ, E.; Nemes, N. The Role of Territorial Identity in the Sustainability of Tourism in Hungary. Geo J. Tour. Geosites 2025, 58, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.G.E.; Remoaldo, P.; Peluso, M.L. Human Values and Tourism Perception: A New Approach in Residents’ Perceptions. Curr. Issues Tour. 2025, 28, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, H.; Barboza, M.; Nogueira, C. Perceptions and Behaviors Concerning Tourism Degrowth and Sustainable Tourism: Latent Dimensions and Types of Tourists. Sustainability 2025, 17, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muresan, I.C.; Harun, R.; Arion, F.H.; Fatah, A.O.; Dumitras, D.E. Exploring Residents’ Perceptions of the Socio-Cultural Benefits of Tourism Development in the Mountain Area. Societies 2021, 11, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boley, B.B.; Strzelecka, M.; Woosnam, K.M. Resident Perceptions of the Economic Benefits of Tourism: Toward a Common Measure. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 1295–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, D.; Cho, H.; Woosnam, K.M. Exploring Tourists’ Perceptions of Tourism Impacts. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodaş, D.; Arıca, R.; Kafa, N.; Duman, F. Relationships Between Perceptions of Residents Toward Tourism Development, Benefits Derived from Tourism and Support to Tourism. J. Tourismology 2022, 8, 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, S.; Rasheed, M.I.; Pitafi, A.H.; Pitafi, A.; Ren, M. Road and Transport Infrastructure Development and Community Support for Tourism: The Role of Perceived Benefits, and Community Satisfaction. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 104014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M.; Draper, J.; Jiang, J.K.; Aleshinloye, K.D.; Erul, E. Applying Self-Perception Theory to Explain Residents’ Attitudes About Tourism Development Through Travel Histories. Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Ouyang, Z.; Nunkoo, R.; Wei, W. Residents’ Impact Perceptions of and Attitudes Towards Tourism Development: A Meta-Analysis. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 306–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandeparkar, K.; Maheshwari, B.; Motiani, M. Why Should I Pay More? Testing the Impact of Contextual Cues on Perception of Price Unfairness for the Price-Disadvantaged Segment in Dual Pricing. Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Lv, D.; Fu, S.; Zhu, D.; Zheng, M.; Chen, S.; Zhen, S. The Influence of Tourist Attraction Type on Product Price Perception and Neural Mechanism in Tourism Consumption: An ERP Study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 3787–3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, S.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M. Residents’ Attitudes Towards Tourism, Cost–Benefit Attitudes, and Support for Tourism: A Pre-Development Perspective. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2023, 20, 522–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.; Zheng, Z.; Tian, D.; Zhang, R.; Law, R.; Zhang, M. Resident-Tourist Value Co-Creation in the Intangible Cultural Heritage Tourism Context: The Role of Residents’ Perception of Tourism Development and Emotional Solidarity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo-Cruz, F.; Silva, L.F. What Drives Residents’ Support for Tourism Development of the Camino de Santiago? The Role of Perceived Impacts, Local Socioeconomic Context, and Overall Attitudes. Curr. Issues Tour. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Bolívar, M.P.; Sepe, F.; Nanu, L.; Roberto, F. Perceptions and Challenges of Blockchain Adoption in Tourism Industry: A Study on Trust, Privacy and Security. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2025, 16, 429–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Wang, Y.; Huang, S.; Qiao, G. Perceived Benefits and Tourist Willingness to Pay More in National Forest Parks: The Moderating Roles of Ecocentrism, Collectivism, and Power Distance. J. Vacat. Mark. 2025, 0, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Tan, Q.; Mai, H. Stress-Buffering Effects of Social Support on Tourism Employees During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Moderated Mediation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramkissoon, H. Perceived Social Impacts of Tourism and Quality-of-Life: A New Conceptual Model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 31, 442–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magno, F.; Dossena, G. Pride of Being Part of a Host Community? Medium-Term Effects of Mega-Events on Citizen Quality of Life: The Case of the World Expo 2015 in Milan. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 15, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, S.; Zhou, Z.; Lu, C.; Ramkissoon, H. Online Tourism Information and Tourist Behavior: A Structural Equation Modeling Analysis Based on a Self-Administered Survey. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Wang, Y. Social Support and Travel: Enhancing Relationships, Communication, and Understanding for Travel Companions. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munanura, I.E.; Needham, M.D.; Lindberg, K.; Kooistra, C.; Ghahramani, L. Support for Tourism: The Roles of Attitudes, Subjective Wellbeing, and Emotional Solidarity. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 31, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Cheng, N. Taking Aging Parents on Travel: A Social Support Perspective. Curr. Issues Tour. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafi, A.; Rehman, M.A.; Sharif, S.; Lodhi, R.N. The Role of Social Media Marketing and Social Support in Developing Value Co-Creation Intentions: A Couchsurfing Community Perspective. Glob. Knowl. Mem. Commun. 2025, 74, 1275–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, C.S.; Harvey, W.S.; Shaw, G. Exploring the Relevance of Social Exchange Theory in the Middle East: A Case Study of Tourism in Dubai, UAE. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2023, 25, 198–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solarin, S.A.; Ulucak, R.; Erdogan, S. Assessing the Economic Impacts of Tourism Markets and Activities Diversification: Evidence from a New Dynamic Regression Approach. J. Travel Res. 2024, 63, 2078–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudi, S.; Arasli, H.; Akadiri, S.S. New Insights into an Old Issue – Examining the Influence of Tourism on Economic Growth: Evidence from Selected Small Island Developing States. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 1280–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubaye Assaye Alamineh; Jeylan Wolyie Hussein; Yalew Endaweke Mulu; Bamlaku Taddesse. The Negative Cultural Impact of Tourism and Its Implication on Sustainable Development in Amhara Regional State. Cogent Arts Humanit. 2023, 10, 2224597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehan, Y.; Batool, M.; Hayat, N.; Hussain, D. Socio-Economic and Environmental Impacts of Tourism on Local Community in Gilgit Baltistan, Pakistan: A Local Community Perspective. J. Knowl. Econ. 2023, 14, 180–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, C.K.; Chen, H.; Lee, T.J.; Hyun, S.S.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, Y. The Impacts of Under-Tourism and Place Attachment on Residents’ Life Satisfaction. J. Vacat. Mark. 2023, 30, 694–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reivan-Ortiz, G.G.; Cong, P.T.; Wong, W.K.; Ali, A.; Thu, H.T.T.; Akhter, S. Role of Geopolitical Risk, Currency Fluctuation, and Economic Policy on Tourist Arrivals: Temporal Analysis of BRICS Economies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 78339–78352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengoz, A.; Dogru, T.; Mody, M.; Isik, C. Guiding the Path to Sustainable Tourism Development: Investigating the Role of Tour Guides within a Social Exchange Theory Paradigm. Tour. Manag. 2025, 110, 105162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, R.M.; Tasci, A.D.A.; Woosnam, K.M. Factors Explaining Resident Stakeholders’ Perception and Support for Wineries and Wine Tourism in Florida. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2023, 49, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, N.; Dhingra, S.; Sehrawat, R.; Jain, V.; Himanshu, H. Customers’ Intention to Use Virtual Reality in Tourism: A Comprehensive Analysis of Influencing Factors. Tour. Rev. 2025, 80, 742–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katyukha, D.; Yurovchyk, V.; Horiunova, K.; Melnychenko, S.; Myronov, Y. Leveraging Cultural Heritage for Sustainable Tourism Growth: Contemporary Strategies for Conservation and Promotion. OIDA Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 18, 53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Oorgaz-Agüera, F.; Puig-Cabrera, M.; Moral-Cuadra, S.; Domínguez-Valerio, C.M. Authenticity of Architecture, Place Attachment, Identity and Support for Sustainable Tourism in World Heritage Cities. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 31, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.T.; Park, J.; Li, S.; Song, H. Social Costs of Tourism During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.A.; Long, F. To Travel, or Not to Travel? The Impacts of Travel Constraints and Perceived Travel Risk on Travel Intention Among Malaysian Tourists Amid the COVID-19. J. Consum. Behav. 2022, 21, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo-Cruz, F.; Silva, L.F. What Drives Residents’ Support for Tourism Development of the Camino de Santiago? The Role of Perceived Impacts, Local Socioeconomic Context, and Overall Attitudes. Curr. Issues Tour. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Cao, K.; Muhammad Khan, N.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, F.; Hu, X. Relationship Between Perceived Value of Rural Tourism and Tourist Behavioral Intention. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2025, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordej-De Villa, Ž.; Šulc, I. Cultural Heritage, Tourism and the UN Sustainable Development Goals: The Case of Croatia. In Rethinking Sustainability Towards a Regenerative Economy; Andreucci, M.B., Marvuglia, A., Baltov, M., Hansen, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2021; Volume 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mteti, S.H.; Mpambije, C.J.; Manyerere, D.J. Unlocking Cultural Tourism: Local Community Awareness and Perceptions of Cultural Heritage Resources in Katavi Region in Southern Circuit of Tanzania. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2025, 11, 101295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, G.; Szili, G.; Huang, H. Cultural Heritage Tourism Development in Panyu District, Guangzhou: Community Perspectives on Pride and Preservation, and Concerns for the Future. J. Herit. Tour. 2022, 17, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasela, K. The Role of Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Development of Cultural Tourism. Int. J. Eco-Cult. Tour. Hosp. Plan. Dev. 2023, 6, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Q.; Zuo, Y.; Zhang, M. Intangible Cultural Heritage in Tourism: Research Review and Investigation of Future Agenda. Land 2022, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worku Tadesse, G. Heritage Resources as a Driver of Cultural Tourism Development in Ethiopia: A Review. Cogent Arts Humanit. 2022, 10, 2158623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Valeri, M.; Shekhar. Understanding the Relationship Among Factors Influencing Rural Tourism: A Hierarchical Approach. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2022, 35, 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solakis, K.; Katsoni, V.; Mahmoud, A.B.; Grigoriou, N. Factors Affecting Value Co-Creation Through Artificial Intelligence in Tourism: A General Literature Review. J. Tour. Futur. 2024, 10, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munanura, I.E.; Kline, J.D. Residents’ Support for Tourism: The Role of Tourism Impact Attitudes, Forest Value Orientations, and Quality of Life in Oregon, United States. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2023, 20, 566–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, S.; Alharthi, A. Untangling Factors Influencing Women Entrepreneurs’ Involvement in Tourism and Its Impact on Sustainable Tourism Development. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington-Gray, L. Resident Attitudes Towards Tourism in a Destination in the Stagnation Stage of the Tourism Life Cycle. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2025, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Xu, K.; Sotiriadis, M.; Wang, Y. Exploring the Factors Influencing the Adoption and Usage of Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality Applications in Tourism Education within the Context of COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Hosp. Leisure Sport Tour. Educ. 2022, 30, 100373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajehshahkoohi, M.; Davoodi, S.R.; Shaaban, K. Factors Affecting the Behavioral Intention of Tourists on the Use of Bike Sharing in Tourism Areas. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2022, 43, 100742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutmainah, I.; Yulia, I.A.; Setiawan, F.A.; Setiawan, A.S.; Nurhayati, I.; Rainanto, B.H.; Endri, E. Analysis of Factors Influencing Digital Transformation of Tourism Villages: Evidence from Bogor, Indonesia. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homans, G.C. Social Behavior: Its Elementary Forms; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich: New York, NY, USA, 1961; Available online: https://archive.org/details/socialbehaviorit0000homa (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Blau, P.M. Justice in Social Exchange. Sociol. Inq. 1964, 34, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ap, J. Residents’ Perceptions on Tourism Impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 665–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaberganov, A.; Catterall, P. Using Social Exchange Theory to Examine Residents’ Responses to Heritage Tourism: Case Studies of Samarqand and Bukhara in Uzbekistan. J. Herit. Tour. 2023, 18, 846–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Ramkissoon, H.; You, E.; Kim, M.J. Support of Residents for Sustainable Tourism Development in Nature-Based Destinations: Applying Theories of Social Exchange and Bottom-Up Spillover. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2023, 43, 100643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meira, J.V.d.S.; Hancer, M. Using the Social Exchange Theory to Explore the Employee-Organization Relationship in the Hospitality Industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 670–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, T.H.; Salem, A.E.; Abdelmoaty, M.A.; Saleh, M.I. Renewing the Ecotourism Investments’ Strategies in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Social Exchange Theory Prospects. Geo J. Tour. Geosites 2022, 45, 1661–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, C.H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.L.; Li, K.; Shang, Y. Current Challenges and Opportunities in Cultural Heritage Preservation Through Sustainable Tourism Practices. Curr. Issues Tour. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Sun, H.; Zhu, B.; Yu, X.; Niu, Y.; Kou, C.; Li, W. The Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms and Its Determinants Among Adults in Mainland China: Results From a National Household Survey. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 281, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.K.; Lee, J. Support of Marijuana Tourism in Colorado: A Residents’ Perspective Using Social Exchange Theory. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Developing a Community Support Model for Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 964–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiang, D.; Yang, Z.; Ma, S.S. Unraveling Customer Sustainable Consumption Behaviors in Sharing Economy: A Socio-Economic Approach Based on Social Exchange Theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.C. The Affecting Tourism Development Attitudes Based on the Social Exchange Theory and the Social Network Theory. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrill, R. Residents’ Attitudes Toward Tourism Development: A Literature Review with Implications for Tourism Planning. J. Plan. Lit. 2004, 18, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diedrich, A.; García-Buades, E. Local Perceptions of Tourism as Indicators of Destination Decline. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Jaafar, M.; Ramayah, T. Urban vs. Rural Destinations: Residents’ Perceptions, Community Participation and Support for Tourism Development. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; So, K.K.F.; Wirtz, J. Service Robots: Applying Social Exchange Theory to Better Understand Human–Robot Interactions. Tour. Manag. 2022, 92, 104537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pfister, R.E. Residents’ Attitudes Toward Tourism and Perceived Personal Benefits in a Rural Community. J. Travel Res. 2008, 47, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Biran, A.; Sit, J.; Szivas, E.M. Residents’ Support for Tourism Development: The Role of Residents’ Place Image and Perceived Tourism Impacts. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizal, H.; Amin, H.; Suddin, L.; Sondoh, S.L.; Chen, J.K. Relationship Quality and E-Loyalty Towards Online Travel Agency (OTA): Social Exchange Theory Perspective. J. Pengurusan 2020, 58, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Nawaz, M.R.; Ishaq, M.I.; Khan, M.M.; Ashraf, H.A. Social Exchange Theory: Systematic Review and Future Directions. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1015921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Li, J.; Mao, Z.E.; Lu, Z. Can Ethical Leadership Inspire Employee Loyalty in Hotels in China?—From the Perspective of the Social Exchange Theory. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 49, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulud, D.; Abdulazeez, A.M. A Review on Linear Regression Comprehensive in Machine Learning. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. Trends 2020, 1, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Khalili, A.; Asgharian, M. Post-Model-Selection Inference in Linear Regression Models: An Integrated Review. Stat. Surv. 2022, 16, 86–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, S.; Tripathy, A.; Tripathy, A.R. Prediction of New Active Cases of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic Using Multiple Linear Regression Model. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 1467–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maydeu-Olivares, A.; Shi, D.; Fairchild, A.J. Estimating Causal Effects in Linear Regression Models with Observational Data: The Instrumental Variables Regression Model. Psychol. Methods 2020, 25, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, W. Concept Drift Detection Based on Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test. In Artificial Intelligence in China; Liang, Q., Wang, W., Mu, J., Liu, X., Na, Z., Chen, B., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; Volume 572, pp. 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazos, T.; Poga-Kyriazou, M. Applied Psychometrics: Estimator Considerations in Commonly Encountered Conditions in CFA, SEM, and EFA Practice. Psychology 2023, 14, 799–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharum, H.; Ismail, A.; Awang, Z.; McKenna, L.; Ibrahim, R.; Mohamed, Z.; Hassan, N.H. The Study Adapted Instruments Based on Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to Validate Measurement Models of Latent Constructs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, H.; Aziz, H. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to Measure the Validity and Reliability Constructs of Historical Thinking Skills, Tpack, and Application of Historical Thinking Skills. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. Couns. 2022, 7, 608–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Podsakoff, N.P.; Williams, L.J.; Huang, C.; Yang, J. Common Method Bias: It’s Bad, It’s Complex, It’s Widespread, and It’s Not Easy to Fix. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2024, 11, 17–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, S.; Al Mamun, A.; Yang, Q.; Gao, J.; Hussain, W.M.H.W.; Shami, S.S.A.A. Modelling the Mass Adoption of Mobile Payment for E-Hailing Services Using SEM-MGA. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.; Farinordin, F.A.; Mohamad, N.I.; Lee, U.H.M.S.; Ismail, A. Psychological Empowerment Link Using Employee Performance and Organizational Commitment on the Generation Gap: PLS-MGA Analysis. Gadjah Mada Int. J. Bus. 2024, 26, 23–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngah, A.H.; Kamalrulzaman, N.I.; Mohamad, M.; Grippa, T.; Niang Gadiaga, A.; Linard, C.; Lennert, M.; Vanhuysse, S.; Kalogirou, S. Do Science and Social Science Differ? Multi-Group Analysis (MGA) of the Willingness to Continue Online Learning. Qual. Quant. 2023, 57, 2957–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleki, R.; Quoquab, F.; Mohammad, J. To Buy or Not to Buy Organic Food: Evaluating the Moderating Effect of Gender Using PLS-MGA. Int. J. Bus. Gov. Ethics 2021, 15, 106–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, H.A.; Kalakech, A.; Steiti, A. Random Forest Algorithm Overview. Babylonian J. Mach. Learn. 2024, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, G.; Li, P.; Wang, H.; Zhang, M.; Liang, X. An Improved Random Forest Based on the Classification Accuracy and Correlation Measurement of Decision Trees. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georganos, S.; Grippa, T.; Niang Gadiaga, A.; Linard, C.; Lennert, M.; Vanhuysse, S.; Kalogirou, S. Geographical Random Forests: A Spatial Extension of the Random Forest Algorithm to Address Spatial Heterogeneity in Remote Sensing and Population Modelling. Geocarto Int. 2019, 36, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Jabeur, S.; Stef, N.; Carmona, P. Bankruptcy Prediction Using the XGBoost Algorithm and Variable Importance Feature Engineering. Comput. Econ. 2023, 61, 715–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Serbia (N = 472) | Kazakhstan (N = 465) | Hungary (N = 450) | Total (N = 1387) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 217 (46.0%) | 212 (45.6%) | 204 (45.3%) | 633 (45.6%) |

| Female | 255 (54.0%) | 253 (54.4%) | 246 (54.7%) | 754 (54.4%) |

| Age | ||||

| 18-29 | 178 (37.7%) | 166 (35.7%) | 162 (36.0%) | 506 (36.5%) |

| 30-44 | 148 (31.4%) | 145 (31.2%) | 136 (30.2%) | 429 (30.9%) |

| 45-59 | 108 (22.9%) | 112 (24.1%) | 108 (24.0%) | 328 (23.6%) |

| 60+ | 38 (8.0%) | 42 (9.0%) | 44 (9.8%) | 124 (8.9%) |

| Education | ||||

| Primary education | 10 (2.1%) | 12 (2.6%) | 10 (2.2%) | 32 (2.3%) |

| Secondary education | 169 (35.8%) | 128 (27.5%) | 119 (26.4%) | 416 (30.0%) |

| Higher education | 293 (62.1%) | 325 (69.9%) | 321 (71.3%) | 939 (67.7%) |

| Employment | ||||

| Employed | 278 (58.9%) | 295 (63.4%) | 287 (63.8%) | 860 (62.0%) |

| Unemployed | 108 (22.9%) | 105 (22.6%) | 91 (20.2%) | 304 (21.9%) |

| Student | 86 (18.2%) | 65 (14.0%) | 72 (16.0%) | 223 (16.1%) |

| Income | ||||

| High | 24.5% | 30.4% | 40.5% | 31.8% |

| Medium | 50.2% | 50.2% | 46.3% | 48.9% |

| Low | 25.3% | 19.4% | 13.2% | 19.3% |

| Resident | ||||

| Urban | 65.3% | 70.5% | 78.9% | 71.5% |

| Rural | 34.7% | 29.5% | 21.1% | 28.5% |

| Frequency of travel | ||||

| More than 5 trips per year | 25.4% | 28.7% | 36.5% | 30.2% |

| 1 to 5 trips per year | 47.8%, | 48.5% | 44.2% | 46.8% |

| Less than 1 trip per year | 26.8% | 22.8% | 19.3% | 23.0% |

| Contact with tourists | ||||

| Yes | 40.2% | 52.1% | 59.3% | 50.5% |

| No | 59.8% | 47.9% | 40.7% | 49.5% |

| Construct | Theoretical Statements According to Social Exchange Theory | Adapted Statements for the Research | Relevant Authors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benefits Perception (BP) |

People will support tourism if they perceive positive economic, social, or cultural benefits. | Tourism in my area contributes to economic development. Tourism improves the quality of local infrastructure. Tourism enhances cultural promotion and preservation. |

Homans [64]; Blau [65]; Gursoy & Rutherford [18]; Nunkoo & Ramkissoon [74]; Wang & Pfister [75];Chang et al. [76] |

| Costs Perception (CP) |

If perceived costs (pollution, overcrowding, economic inequality) outweigh the benefits, opposition to tourism arises. | Tourism causes an increase in real estate prices and services. Tourism negatively impacts the natural environment. Tourism disrupts the peace and privacy of residents. |

Blau [65]; Ap [66]; Harrill [77]; Diedrich & García-Buades [78]; Rasoolimanesh et al. [79], Kim et al. [80] |

| Social Support (SS) |

Positive relationships between the community and tourists strengthen support for tourism. | Local authorities adequately manage tourism development. Communication between local residents and tourists is positive. There is solidarity and cooperation within the community due to tourism. |

Homans [64]; Nunkoo & Ramkissoon [74]; Gursoy et al. [18]; Wang & Pfister [81]; Stylidis et al. [82]; Rizal et al. [83] |

| Reciprocal Benefits (RB) |

If the community is given the opportunity to benefit from tourism, it is more likely to support its development. | Tourism provides opportunities for employment and additional income. There are economic benefits for local residents from tourism. There is an opportunity to include local products in the tourism offer. |

Homans [64]; Gursoy & Rutherford [18]; Stylidis et al. [82]; Rasoolimanesh et al. [79], Ahmad et al. [84] |

| Cultural Identification (CI) |

If local culture is affirmed through tourism, support for its development increases. | Tourism helps preserve cultural heritage. Tourists show interest in local customs and traditions. Local culture is positively promoted through tourism. |

Blau [656]; Ap [66]; Gursoy et al. [18]; Stylidis et al. [82]; Rasoolimanesh et al. [79], Wang et al. [81]; Fan et al., [85] |

| Support for tourism development (STD) | Positive perceived benefits compared to costs lead to support for tourism development. | I support the further development of tourism in my area. I am willing to promote the tourism offer of my community. Tourism in my area is sustainable and contributes to overall well-being. |

Homans [64]; Blau [65]; Gursoy & Rutherford [18]; Nunkoo & Ramkissoon [74]; Rasoolimanesh et al. [79] |

| Country | Total number of respondents | EFA (30% of total sample) |

CFA (70% of total sample) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRB | 527 | 158 | 369 | |

| KAZ | 569 | 171 | 398 | |

| HUN | 614 | 184 | 430 | |

| Year | Serbia (mil.) | Kazahstan (mil.) | Hungary (mil.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 1.281 | 6.430 | 48.345 |

| 2016 | 1.281 | 6.509 | 52.890 |

| 2017 | 1.497 | 7.701 | 54.962 |

| 2018 | 1.710 | 8.789 | 57.667 |

| 2019 | 1.847 | 8.515 | 61.397 |

| 2020 | 0.498 | 2.035 | 31.641 |

| 2021 | 0.819 | 3.100 | 36.688 |

| 2022 | 1.409 | 4.500 | 46.343 |

| 2023 | 1.519 | 4.900 | 49.403 |

| Parameters | Serbia | Kazakhstan | Hungary |

|---|---|---|---|

| R² | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.94 |

| AIC | 320.4 | 335.1 | 298.7 |

| BIC | 326.2 | 341.0 | 304.5 |

| RMSE | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| P-values | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| Durbin-Watson | 1.98 | 2.01 | 1.95 |

| Year | Serbia | Kazakhstan | Hungary |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 1.281 | 4.4 | 48.345 |

| 2016 | 1.281 | 4.6 | 52.89 |

| 2017 | 1.497 | 4.8 | 54.962 |

| 2018 | 1.71 | 4.9 | 57.667 |

| 2019 | 1.847 | 5.2 | 61.397 |

| 2020 | 0.498 | 3.1 | 31.641 |

| 2021 | 0.819 | 3.8 | 36.688 |

| 2022 | 1.409 | 4.5 | 46.343 |

| 2023 | 1.519 | 4.9 | 49.403 |

| 2024 | 1.55 | 5 | 50 |

| 2025 | 1.6 | 5.1 | 52 |

| 2026 | 1.65 | 5.2 | 54 |

| 2027 | 1.7 | 5.3 | 56 |

| 2028 | 1.75 | 5.4 | 58 |

| 2029 | 1.8 | 5.5 | 60 |

| 2030 | 1.85 | 5.6 | 62 |

| Year | Serbia Forecast | Serbia Increase 10% | Serbia Decrease 10% | Kazakhstan Forecast | Kazakhstan Increase 10% | Kazakhstan Decrease 10% | Hungary Forecast | Hungary Increase 10% | Hungary Decrease 10% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2025 | 1600 | 1760 | 1440 | 5000 | 5500 | 4500 | 50000 | 55000 | 45000 |

| 2026 | 1700 | 1870 | 1530 | 5200 | 5720 | 4680 | 52000 | 57200 | 46800 |

| 2027 | 1800 | 1980 | 1620 | 5400 | 5940 | 4860 | 54000 | 59400 | 48600 |

| 2028 | 1900 | 2090 | 1710 | 5600 | 6160 | 5040 | 56000 | 61600 | 50400 |

| 2029 | 2000 | 2200 | 1800 | 5800 | 6380 | 5220 | 58000 | 63800 | 52200 |

| 2030 | 2100 | 2310 | 1890 | 6000 | 6600 | 5400 | 60000 | 66000 | 54000 |

| Construct | Item | SRB (m) | SRB (sd) | SRB (α) | SRB (λ) | KAZ (m) | KAZ (sd) | KAZ (α) | KAZ (λ) | HUN (m) | HUN (sd) | HUN (α) | HUN (λ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | Tourism in my area contributes to economic development. | 4.312 | 0.627 | 0.829 | 0.741 | 4.198 | 0.721 | 0.872 | 0.719 | 4.407 | 0.602 | 0.883 | 0.751 |

| Tourism improves the quality of local infrastructure. | 4.158 | 0.721 | 0.806 | 0.802 | 4.011 | 0.789 | 0.812 | 0.734 | 4.478 | 0.684 | 0.844 | 0.765 | |

| Tourism enhances cultural promotion and preservation. | 4.476 | 0.602 | 0.853 | 0.752 | 4.215 | 0.733 | 0.863 | 0.787 | 4.536 | 0.671 | 0.813 | 0.769 | |

| CP | Tourism causes an increase in real estate prices and services. | 3.269 | 0.893 | 0.850 | 0.708 | 3.198 | 0.912 | 0.804 | 0.702 | 3.389 | 0.856 | 0.827 | 0.731 |

| Tourism negatively impacts the natural environment. | 3.429 | 0.756 | 0.869 | 0.684 | 3.312 | 0.781 | 0.834 | 0.689 | 3.476 | 0.792 | 0.893 | 0.711 | |

| Tourism disrupts the peace and privacy of local residents. | 3.501 | 0.804 | 0.806 | 0.793 | 3.408 | 0.841 | 0.800 | 0.761 | 3.523 | 0.822 | 0.866 | 0.755 | |

| SS | Local authorities adequately manage tourism development. | 3.972 | 0.845 | 0.837 | 0.768 | 3.882 | 0.892 | 0.856 | 0.755 | 4.014 | 0.831 | 0.884 | 0.772 |

| Communication between local residents and tourists is positive. | 4.001 | 0.674 | 0.834 | 0.798 | 4.007 | 0.667 | 0.821 | 0.794 | 4.058 | 0.689 | 0.838 | 0.812 | |

| There is solidarity and cooperation within the community due to tourism. | 4.088 | 0.737 | 0.814 | 0.752 | 4.116 | 0.704 | 0.877 | 0.777 | 4.171 | 0.723 | 0.829 | 0.789 | |

| RB | Tourism provides opportunities for employment and additional income. | 4.237 | 0.532 | 0.879 | 0.781 | 4.123 | 0.598 | 0.867 | 0.768 | 4.267 | 0.512 | 0.881 | 0.784 |

| There are economic benefits for local residents from tourism. | 4.112 | 0.678 | 0.809 | 0.731 | 4.109 | 0.654 | 0.867 | 0.751 | 4.214 | 0.645 | 0.819 | 0.772 | |

| There is an opportunity to include local products in the tourism offer. | 4.145 | 0.739 | 0.855 | 0.792 | 4.189 | 0.724 | 0.867 | 0.785 | 4.299 | 0.701 | 0.858 | 0.811 | |

| CI | Tourism helps preserve cultural heritage. | 4.265 | 0.692 | 0.862 | 0.783 | 4.142 | 0.715 | 0.870 | 0.772 | 4.381 | 0.674 | 0.878 | 0.795 |

| Tourists show interest in local customs and traditions. | 4.203 | 0.724 | 0.841 | 0.769 | 4.098 | 0.752 | 0.854 | 0.751 | 4.295 | 0.712 | 0.861 | 0.784 | |

| Local culture is positively promoted through tourism. | 4.312 | 0.676 | 0.851 | 0.788 | 4.221 | 0.702 | 0.863 | 4.312 | 0.676 | 0.851 | 0.788 | 4.221 | |

| STD | I support the further development of tourism in my area. | 4.276 | 0.609 | 0.915 | 0.824 | 4.241 | 0.632 | 0.923 | 0.817 | 4.315 | 0.611 | 0.918 | 0.828 |

| I am willing to promote the tourism offer of my community. | 4.231 | 0.621 | 0.904 | 0.837 | 4.294 | 0.617 | 0.906 | 0.839 | 4.398 | 0.603 | 0.903 | 0.841 | |

| Tourism in my area is sustainable and contributes to overall well-being. | 4.318 | 0.642 | 0.900 | 0.801 | 4.307 | 0.659 | 0.908 | 0.792 | 4.389 | 0.632 | 0.944 | 0.813 |

| Construct | m | sd | α | Eigenvalues | % Variance | Cumulative % | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serbia | ||||||||

| BP | 4.282 | 0.650 | 0.889 | 3.428 | 34.28% | 34.28% | 0.912 | 0.783 |

| CP | 3.399 | 0.822 | 0.856 | 2.945 | 29.45% | 63.73% | 0.879 | 0.701 |

| SS | 4.020 | 0.786 | 0.872 | 2.177 | 21.77% | 85.50% | 0.891 | 0.732 |

| RB | 4.187 | 0.624 | 0.879 | 1.902 | 19.02% | 94.52% | 0.874 | 0.711 |

| CI | 4.134 | 0.703 | 0.884 | 1.510 | 15.10% | 96.12% | 0.886 | 0.720 |

| STD | 4.304 | 0.621 | 0.915 | 1.305 | 13.05% | 98.23% | 0.918 | 0.750 |

| Kazakhstan | ||||||||

| BP | 4.190 | 0.621 | 0.878 | 3.601 | 36.01% | 36.01% | 0.910 | 0.741 |

| CP | 3.450 | 0.789 | 0.860 | 2.801 | 28.01% | 64.02% | 0.882 | 0.795 |

| SS | 4.030 | 0.790 | 0.874 | 2.340 | 23.40% | 87.42% | 0.893 | 0.734 |

| RB | 4.210 | 0.612 | 0.882 | 1.935 | 19.35% | 96.77% | 0.877 | 0.713 |

| CI | 4.150 | 0.702 | 0.880 | 1.710 | 17.10% | 98.87% | 0.888 | 0.742 |

| STD | 4.315 | 0.615 | 0.919 | 1.400 | 14.00% | 99.91% | 0.921 | 0.781 |

| Hungary | ||||||||

| BP | 4.312 | 0.609 | 0.890 | 3.750 | 37.50% | 37.50% | 0.916 | 0.748 |

| CP | 3.462 | 0.810 | 0.865 | 2.954 | 29.54% | 67.04% | 0.884 | 0.706 |

| SS | 4.040 | 0.772 | 0.880 | 2.400 | 24.00% | 91.04% | 0.895 | 0.755 |

| RB | 4.222 | 0.601 | 0.886 | 1.950 | 19.50% | 98.54% | 0.889 | 0.764 |

| CI | 4.210 | 0.710 | 0.892 | 1.540 | 15.40% | 98.84% | 0.894 | 0.723 |

| STD | 4.328 | 0.605 | 0.921 | 1.315 | 13.15% | 100.00% | 0.923 | 0.773 |

| Constructs | BP | CP | SS | RB | STD | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serbia | ||||||

| BP | 1.000 | 0.467 | 0.492 | 0.528 | 0.553 | 0.507 |

| CP | 0.467 | 1.000 | 0.425 | 0.413 | 0.398 | 0.374 |

| SS | 0.492 | 0.425 | 1.000 | 0.462 | 0.444 | 0.472 |

| RB | 0.528 | 0.413 | 0.462 | 1.000 | 0.535 | 0.494 |

| STD | 0.553 | 0.398 | 0.444 | 0.535 | 1.000 | 0.519 |

| CI | 0.507 | 0.374 | 0.472 | 0.494 | 0.519 | 1.000 |

| Kazakhstan | ||||||

| BP | CP | SS | RB | STD | CI | |

| BP | 1.000 | 0.455 | 0.482 | 0.520 | 0.548 | 0.504 |

| CP | 0.455 | 1.000 | 0.416 | 0.409 | 0.395 | 0.371 |

| SS | 0.482 | 0.416 | 1.000 | 0.467 | 0.455 | 0.478 |

| RB | 0.520 | 0.409 | 0.467 | 1.000 | 0.531 | 0.499 |

| STD | 0.548 | 0.395 | 0.455 | 0.531 | 1.000 | 0.512 |

| CI | 0.504 | 0.371 | 0.478 | 0.499 | 0.512 | 1.000 |

| Hungary | ||||||

| BP | CP | SS | RB | STD | CI | |

| BP | 1.000 | 0.459 | 0.497 | 0.537 | 0.562 | 0.522 |

| CP | 0.459 | 1.000 | 0.423 | 0.416 | 0.403 | 0.377 |

| SS | 0.497 | 0.423 | 1.000 | 0.475 | 0.463 | 0.480 |

| RB | 0.537 | 0.416 | 0.475 | 1.000 | 0.548 | 0.515 |

| STD | 0.562 | 0.403 | 0.463 | 0.548 | 1.000 | 0.528 |

| CI | 0.522 | 0.377 | 0.480 | 0.515 | 0.528 | 1.000 |

| Country | Construct | R² | Q² | f² | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serbia | STD | 0.718 | 0.521 | 0.467 | 0.532 | 0.124 | 0.656 |

| Kazakhstan | STD | 0.704 | 0.513 | 0.442 | 0.521 | 0.118 | 0.639 |

| Hungary | STD | 0.729 | 0.529 | 0.472 | 0.545 | 0.127 | 0.672 |

| Construct | Serbia | Kazahstan | Hungary | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | m | sd | t | p | β | m | sd | t | p | β | m | sd | t | p | |

| BP → STD | 0.371 | 4.282 | 0.650 | 8.453 | 0.000 | 0.367 | 4.282 | 0.621 | 8.342 | 0.000 | 0.372 | 4.312 | 0.650 | 8.478 | 0.000 |

| CP → STD | -0.203 | 3.399 | 0.822 | -3.249 | 0.012 | -0.215 | 3.399 | 0.789 | -3.521 | 0.010 | -0.208 | 3.462 | 0.822 | -3.410 | 0.011 |

| SS → STD | 0.338 | 4.020 | 0.786 | 6.721 | 0.000 | 0.341 | 4.020 | 0.790 | 6.725 | 0.000 | 0.347 | 4.040 | 0.786 | 6.856 | 0.000 |

| RB → STD | 0.282 | 4.187 | 0.624 | 5.104 | 0.005 | 0.276 | 4.187 | 0.612 | 5.211 | 0.004 | 0.284 | 4.222 | 0.624 | 5.318 | 0.005 |

| CI → STD | 0.297 | 4.105 | 0.699 | 5.567 | 0.002 | 0.299 | 4.105 | 0.674 | 5.761 | 0.002 | 0.305 | 4.300 | 0.699 | 5.812 | 0.002 |

| BP × Mod-FT → STD | 0.173 | 4.150 | 0.654 | 4.022 | 0.004 | 0.148 | 4.150 | 0.635 | 3.289 | 0.009 | 0.162 | 4.310 | 0.654 | 3.870 | 0.007 |

| BP × Mod-CT → STD | 0.214 | 4.220 | 0.672 | 4.261 | 0.005 | 0.191 | 4.220 | 0.671 | 3.710 | 0.012 | 0.204 | 4.320 | 0.672 | 4.134 | 0.006 |

| CP× Mod-FT → STD | -0.127 | 3.199 | 0.801 | -2.149 | 0.032 | -0.135 | 3.199 | 0.799 | -2.385 | 0.026 | -0.122 | 3.400 | 0.801 | -2.352 | 0.041 |

| CP Mod-CT → STD | -0.101 | 3.402 | 0.812 | -2.021 | 0.047 | -0.114 | 3.402 | 0.811 | -2.073 | 0.038 | -0.109 | 3.410 | 0.812 | -2.091 | 0.050 |

| SS× Mod-FT → STD | 0.187 | 4.060 | 0.772 | 4.321 | 0.003 | 0.178 | 4.060 | 0.780 | 3.953 | 0.008 | 0.196 | 4.030 | 0.772 | 4.572 | 0.004 |

| SS Mod-CT → STD | 0.201 | 4.115 | 0.784 | 4.565 | 0.004 | 0.194 | 4.115 | 0.770 | 4.120 | 0.007 | 0.209 | 4.050 | 0.784 | 4.800 | 0.005 |

| RB × Mod-FT → STD | 0.176 | 4.200 | 0.621 | 4.221 | 0.006 | 0.158 | 4.200 | 0.619 | 3.986 | 0.009 | 0.181 | 4.230 | 0.621 | 4.324 | 0.005 |

| RB × Mod-CT → STD | 0.193 | 4.250 | 0.632 | 4.521 | 0.005 | 0.183 | 4.250 | 0.625 | 4.222 | 0.007 | 0.190 | 4.270 | 0.632 | 4.511 | 0.006 |

| CI × Mod-FT → STD | 0.168 | 4.180 | 0.675 | 4.112 | 0.008 | 0.175 | 4.180 | 0.662 | 4.007 | 0.006 | 0.179 | 4.290 | 0.675 | 4.124 | 0.008 |

| CI × Mod-CT → STD | 0.202 | 4.210 | 0.681 | 4.634 | 0.004 | 0.198 | 4.210 | 0.671 | 4.512 | 0.005 | 0.194 | 4.310 | 0.681 | 4.488 | 0.004 |

| Construct | Δβ (SRB-KAZ) | Δt (SRB-KAZ) | Δp (SRB-KAZ) | Significance (SRB-KAZ) | Δβ (SRB-HUN) | Δt (SRB-HUN) | Δp (SRB-HUN) | Significance (SRB-HUN) | Q² (SRB) | Q² (KAZ) | Q² (HUN) | f² (SRB) | f² (KAZ) | f² (HUN) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP → STD | 0.004 | 2.789 | 0.006 | Significant | 0.007 | 2.901 | 0.005 | Significant | 0.282 | 0.276 | 0.298 | 0.315 | 0.309 | 0.328 |

| CP → STD | 0.012 | 2.853 | 0.005 | Significant | 0.015 | 3.012 | 0.004 | Significant | 0.198 | 0.191 | 0.204 | 0.192 | 0.186 | 0.194 |

| SS → STD | 0.008 | 2.762 | 0.007 | Significant | 0.009 | 2.801 | 0.006 | Significant | 0.310 | 0.305 | 0.318 | 0.334 | 0.328 | 0.339 |

| RB → STD | 0.017 | 2.945 | 0.004 | Significant | 0.016 | 2.910 | 0.005 | Significant | 0.241 | 0.238 | 0.249 | 0.222 | 0.218 | 0.227 |

| CI → STD | 0.019 | 2.971 | 0.004 | Significant | 0.015 | 2.923 | 0.004 | Significant | 0.289 | 0.283 | 0.295 | 0.308 | 0.302 | 0.313 |

| BP × Mod-FT → STD | 0.021 | 3.012 | 0.003 | Significant | 0.018 | 2.981 | 0.003 | Significant | 0.262 | 0.257 | 0.269 | 0.291 | 0.284 | 0.296 |

| BP × Mod-CT → STD | 0.016 | 2.902 | 0.004 | Significant | 0.014 | 2.875 | 0.005 | Significant | 0.275 | 0.270 | 0.282 | 0.294 | 0.287 | 0.298 |

| CP × Mod-FT → STD | 0.020 | 3.005 | 0.003 | Significant | 0.019 | 2.992 | 0.003 | Significant | 0.216 | 0.210 | 0.223 | 0.238 | 0.232 | 0.244 |

| CP × Mod-CT → STD | 0.018 | 2.974 | 0.004 | Significant | 0.017 | 2.951 | 0.004 | Significant | 0.203 | 0.198 | 0.209 | 0.219 | 0.214 | 0.223 |

| SS × Mod-FT → STD | 0.022 | 3.103 | 0.002 | Significant | 0.020 | 3.067 | 0.002 | Significant | 0.307 | 0.302 | 0.314 | 0.336 | 0.330 | 0.341 |

| SS × Mod-CT → STD | 0.015 | 2.865 | 0.005 | Significant | 0.014 | 2.832 | 0.005 | Significant | 0.298 | 0.292 | 0.303 | 0.318 | 0.312 | 0.325 |

| RB × Mod-FT → STD | 0.019 | 3.022 | 0.003 | Significant | 0.018 | 3.009 | 0.003 | Significant | 0.248 | 0.242 | 0.258 | 0.232 | 0.227 | 0.240 |

| RB × Mod-CT → STD | 0.020 | 3.045 | 0.002 | Significant | 0.021 | 3.078 | 0.002 | Significant | 0.256 | 0.250 | 0.265 | 0.235 | 0.230 | 0.240 |

| CI × Mod-FT → STD | 0.018 | 2.984 | 0.004 | Significant | 0.017 | 2.952 | 0.004 | Significant | 0.295 | 0.290 | 0.305 | 0.310 | 0.305 | 0.320 |

| CI × Mod-CT → STD | 0.019 | 3.012 | 0.003 | Significant | 0.020 | 3.089 | 0.002 | Significant | 0.308 | 0.302 | 0.318 | 0.328 | 0.322 | 0.340 |

| Metric | Serbia | Kazakhstan | Hungary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 0.875 | 0.868 | 0.872 |

| Precision | 0.843 | 0.839 | 0.846 |

| Recall | 0.856 | 0.850 | 0.860 |

| F1-score | 0.849 | 0.844 | 0.853 |

| AUC-ROC | 0.892 | 0.888 | 0.895 |

| Variables | Serbia (Importance) | Kazakhstan (Importance) | Hungary (Importance) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benefits Perception (BP) | 0.218 | 0.207 | 0.223 |

| Costs Perception (CP) | 0.164 | 0.157 | 0.166 |

| Social Support (SS) | 0.204 | 0.198 | 0.209 |

| Reciprocal Benefits (RB) | 0.189 | 0.186 | 0.191 |

| Cultural Identification (CI) | 0.225 | 0.223 | 0.211 |

| Actual / Predicted | Positive (STD) | Negative (STD) |

|---|---|---|

| Positive (STD) | 782 | 118 |

| Negative (STD) | 124 | 764 |

| Cluster | Sample | Dominant Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 480 | Highly positive perceptions of benefits |

| 2 | 525 | Balanced perceptions of benefits and costs |

| 3 | 382 | Negative perceptions due to high costs |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).