Submitted:

26 September 2025

Posted:

29 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review, Conceptual Model and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Structural Barriers in Community-Based Tourism

2.2. Community Disempowerment and Local Support

2.3. Conceptual Model and Hypotheses Development

3. Materials and Methods

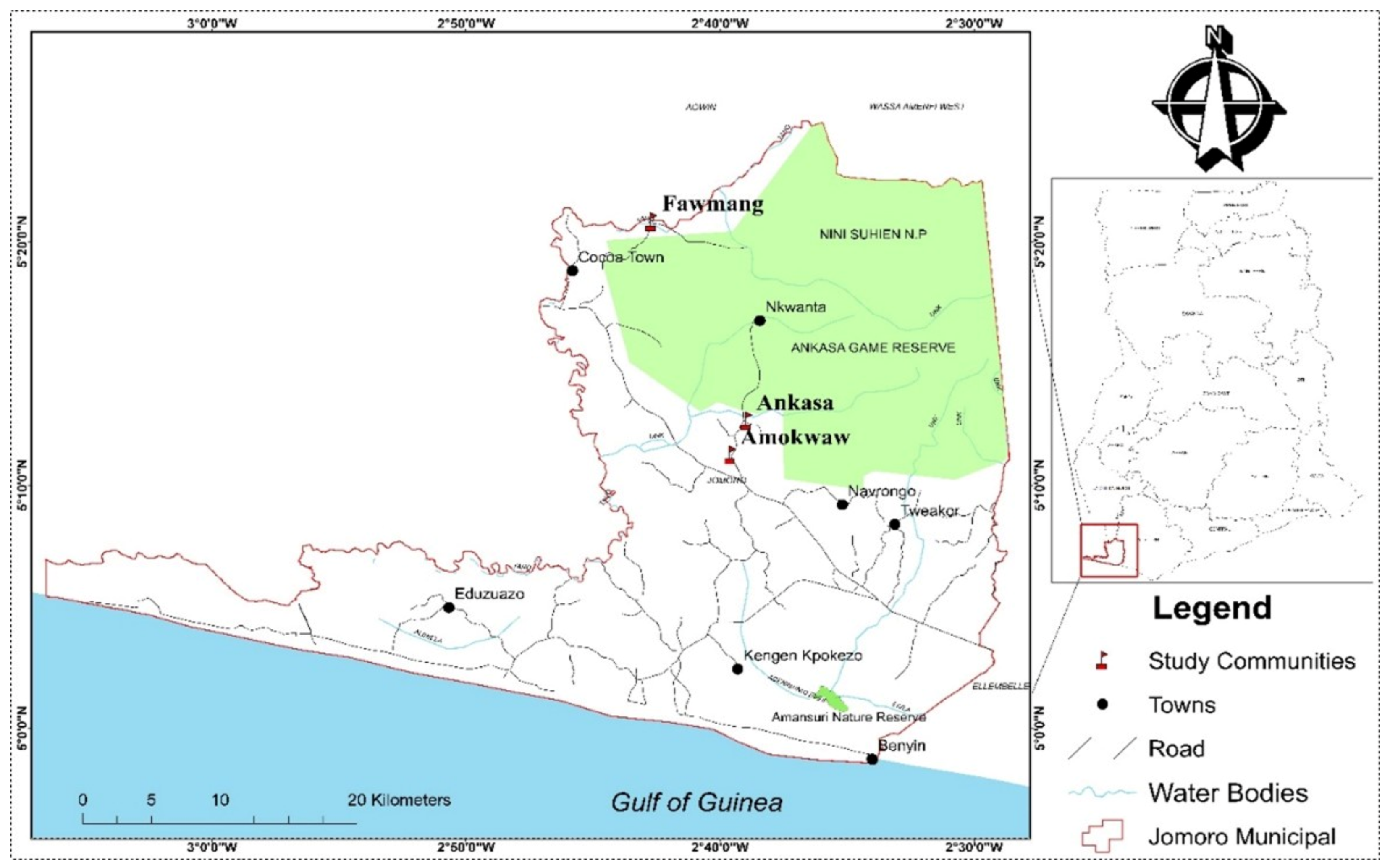

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Participants’ Profile

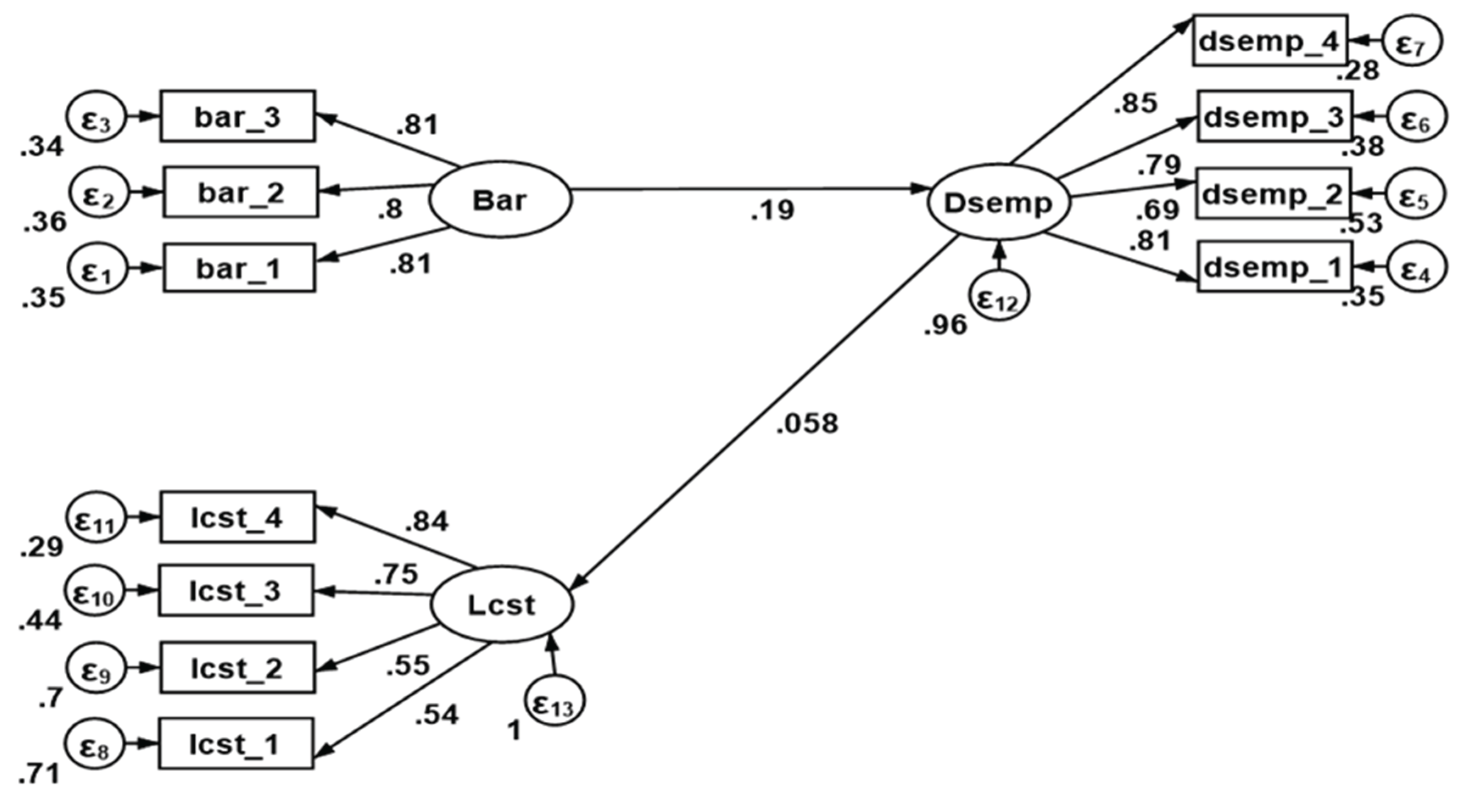

4.2. Measurement Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical and Policy Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

5.4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Timothy, D.J. Empowerment and stakeholder participation in tourism destination communities. In Tourism, Power and Space; Church, A., Coles, T., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; pp. 199–216. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.E.; Gasparatos, A. Multi-dimensional energy poverty patterns around industrial crop projects in Ghana: Enhancing the energy poverty alleviation potential of rural development strategies. Energy Policy 2020, 137, 111123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akama, J.S.; Lant, C.L.; Burnett, G.W. Conflicting attitudes toward state wildlife conservation programs in Kenya. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2011, 8, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Ali, A.; Galaski, K. Mobilizing knowledge: Determining key elements for success and pitfalls in developing community-based tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 1547–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstock, K. A critical look at community-based tourism. Community Dev. J. 2005, 40, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowforth, M.; Munt, I. Tourism and Sustainability: Development, Globalization and New Tourism in the Third World, 4th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, L.S.; Stone, T.M. Community-based tourism enterprises: Challenges and prospects for community participation; Khama Rhino Sanctuary Trust, Botswana. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 19, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.; Milne, S.; Sandiford, F. Community participation in wildlife conservation in the Ankasa Conservation Area, Ghana. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1175–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Honey, M.; Krantz, D. Global Trends in Coastal Tourism; Stanford Environmental Foundation: Stanford, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Saarinen, J.; Rogerson, C.; Hall, C.M. Destinations and communities: New geographies of tourism development in the global South. In Geographies of Tourism Development and Planning in the Global South; Saarinen, J., Rogerson, C., Hall, C.M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, C. Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 613–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S. Information and empowerment: The keys to achieving sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2006, 14, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imanaly, A.; Yang, Z. The influence of tourism revenue sharing constraints on sustainable tourism development: A study of Aksu-Jabagly nature reserve, Kazakhstan. Asian Geogr. 2021, 38, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mawutor, J.K.M.; Hajjar, R. Elite capture and community forest governance in Ghana. For. Policy Econ. 2024, 158, 103089. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Sustainable Tourism Development and Management; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, R.V. The political economy of tourism development: A critical review. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 70, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, W.M.; Hutton, J. People, parks and poverty: Political ecology and biodiversity conservation. Conserv. Soc. 2007, 5, 147–183. [Google Scholar]

- Sebele, L.S. Community-based tourism ventures, benefits and challenges: Khama Rhino Sanctuary Trust, Central District, Botswana. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bempah, I.A.; Adjei, P.O.; Agyeman, K.O. Ecotourism and local community development: The case of Ankasa Conservation Area in Ghana. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 30, 152–163. [Google Scholar]

- Zielinski, S. (2018). Factors that facilitate and inhibit community-based tourism in natural areas of developing countries. Graduate School, Seoul National University Department of Forest Sciences Forest Environmental Sciences Major.

- Eshun, G.; Asiedu, A.B. Community-based ecotourism in Ghana: Challenges and prospects. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2021, 18, 456–472. [Google Scholar]

- Asiedu, A.B. Making ecotourism more supportive of rural development in Ghana. W. Afr. J. Appl. Ecol. 2002, 3, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J.; Ashley, C. Tourism and Poverty Reduction: Pathways to Prosperity; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ap, J. Residents' perceptions on tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 665–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Rutherford, D.G. Host attitudes toward tourism: An improved structural model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doxey, G.V. A causation theory of visitor-resident irritants: Methodology and research inferences. In Proceedings of the Travel Research Association 6th Annual Conference; Travel Research Association: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 1975; pp. 195–198. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley, R. Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Byrd, E.T.; Bosley, H.E.; Dronberger, M.G. Comparisons of stakeholder perceptions of tourism impacts in rural eastern North Carolina. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Andereck, K.L.; Valentine, K.M.; Knopf, R.C.; Vogt, C.A. Residents' perceptions of community tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 1056–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangi, T.B.; Jamal, T. An integrated approach to "sustainable community-based tourism". Sustainability 2016, 8, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampiccoli, A.; Saayman, M. Community-based tourism development model and community participation. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2018, 7, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Developing a community support model for tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 964–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Power, trust, social exchange and community support. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 997–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Smith, S.L.; Ramkissoon, H. Residents' attitudes to tourism: A longitudinal study of 140 articles from 1984 to 2010. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croes, R.; Rivera, M.A. Tourism's potential to benefit the poor: A social accounting matrix model applied to Ecuador. Tour. Econ. 2017, 23, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, M.D.; Dada, Z.A.; Shah, S.A. The impact of community empowerment on sustainable tourism development and the mediation effect of local support: A structural equation modeling approach. Community Dev. 2024, 55, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imanaly Akbar & Zhaoping Yang (2021): The influence of tourism revenue sharing constraints on sustainable tourism development: a study of Aksu-Jabagly nature reserve, Kazakhstan, Asian Geographer. [CrossRef]

- Wildlife Division. (2000). Policy for collaborative community-based wildlife management. Government of Ghana.

- Scheyvens, R.; van der Van der Watt, H. Tourism, Empowerment and Sustainable Development: A New Framework for Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoako-Atta, E.E.; Dayour, F.F.; Bonye, S.Z. Community participation in the management of Wechiau Community Hippo sanctuary, Ghana. Ghana Journal of Development Studies 2020, 17, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Wu, P.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Z. Tourism development and the disempowerment of host residents: types and formative mechanisms. Tourism Geographies 2014, 16, 717–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas Yeboah (2021): Dynamics of Ecotourism Benefits Distribution, Tourism Planning & Development. [CrossRef]

- Eshun, G.; Tagoe-Darko, E. Ecotourism development in Ghana: A postcolonial analysis. Development Southern Africa 2015, 32, 392–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricky Yao Nutsugbodo & Collins Adjei Mensah (2020): Benefits and barriers to women’s participation in ecotourism development within the Kakum Conservation Area (Ghana): Implications for community planning, Community Development. [CrossRef]

- Adeyanju, S.; O'connor, A.; Addoah, T.; Bayala, E.; Djoudi, H.; Moombe, K.; Sunderland, T.; et al. Learning from community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) in Ghana and Zambia: lessons for integrated landscape approaches. International Forestry Review 2021, 23, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansah, I. K. (2018). Residents` Perception of Tourism Impact in Ankasa Conservation Area. University of Cape Coast.

- Ashiagbor, G.; Abubakar, S.K.; Inusah, S.S.; Adjapong, A.O.; Osei, G.N.; Laari, P.B. Analysis of the Impact of Agriculture and Logging on Forest Habitat Structure in the Ankasa and Bia Conservation Area of Ghana. Ecology and Evolution 2024, 14, e70712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, G.; Anning, A.K.; Belford, E.J.; Acquah, E. Plant species diversity, abundance and conservation status of the Ankasa Resource Reserve, Ghana. Trees, Forests and People 2022, 8, 100264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondirad, A.; Tolkach, D.; King, B. Stakeholder collaboration as a major factor for sustainable ecotourism development in developing countries. Tourism management 2020, 78, 104024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutra, C.; Edwards, J. Capacity building through socially responsible tourism development: A Ghanaian case study. Journal of travel research 2012, 51, 779–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Stoffelen, A.; Vanclay, F. Ethnic tourism in China: tourism-related (dis)empowerment of Miao villages in Hunan province. Tourism Geographies 2023, 25, 552–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pius Siakwah, Regis Musavengane & Llewellyn Leonard (2019): Tourism Governance and Attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals in Africa, Tourism Planning & Development. [CrossRef]

- Eshun, G.; Mensah, K. Agrotourism Niche-Market in Ghana: A MultiStakeholder Approach. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 2020, 9, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neger, C. Ecotourism in crisis: an analysis of the main obstacles for the sector's economic sustainability. Journal of Ecotourism 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumusiime, D.M.; Vedeld, P. False promise or false premise? Using tourism revenue sharing to promote conservation and poverty reduction in Uganda. Conservation and society 2012, 10, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2021). Population and Housing Census: Summary Report of Provisional Results. Accra. Ghana Statistical Service, P.O Box GP 1098, Ghana.

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social Research Methods Bryman, Oxford University Press. 5th Edition.

- Bayala, E.R.C.; Zida, M.; Asubonteng, K.O.; Ros-Tonen, M.A.; Reed, J.; Siangulube, F.S.; Sunderland, T.; et al. Assessing CREMAs’ Capacity to Govern Landscape Resources in the Western Wildlife Corridor of Northern Ghana. Environmental Management 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baruah, M. Facipulation and elite formation: Community resource management in Southwestern Ghana. Conservation and Society 2017, 15, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyare, A.K.; Holbech, L.H.; Arcilla, N. Great expectations, not-so-great performance: Participant views of community-based natural resource management in Ghana, West Africa. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability 2024, 7, 100251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- deGraft-Johnson, K.A.A.; Blay, J.; Nunoo, F.K.E.; Amankwah, C.C. (2010). Biodiversity threats assessment of the Western Region of Ghana. The integrated coastal and fisheries governance (ICFG) initiative Ghana.

- Ahmed, A.; Gasparatos, A. Reconfiguration of land politics in community resource management areas in Ghana: Insights from the Avu Lagoon CREMA. Land use policy 2020, 97, 104786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofield, T. H. (2003). Empowerment for sustainable tourism development. Emerald Group Publishing.

| Demographic Variable | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 107 | 52 |

| Female | 98 | 48 |

| Age Group | ||

| Youth (18-35) | 82 | 40 |

| Adult (36-65) | 94 | 46 |

| Aged (66- 85) | 29 | 14 |

| Educational Level | ||

| None | 12 | 6 |

| Primary | 47 | 23 |

| JHS | 121 | 59 |

| SHS | 19 | 9 |

| Tertiary | 6 | 3 |

| Primary Occupation | ||

| Farmer | 156 | 76 |

| Public service (tourism) | 2 | 1 |

| Public service (non-tourism) | 10 | 5 |

| Trader | 23 | 11 |

| Unemployed | 14 | 7 |

| Monthly Household Income | ||

| Below GHȻ 1000 | 19 | 9 |

| GHȻ 1000- GHȻ 1900 | 51 | 25 |

| GHȻ 2000- GHȻ 2900 | 88 | 43 |

| GHȻ 3000- GHȻ 3900 | 33 | 16 |

| Above GHȻ 3900 | 14 | 7 |

| Tourism's Contribution to Monthly Income | ||

| 0% | 197 | 96 |

| 1%–20% | 2 | 1 |

| 21%–60% | 4 | 2 |

| 61%–100% | 2 | 1 |

| Construct & Indicators | Loadings | Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers (Bar) | 0.847 | 0.847 | 0.648 | |

| bar_1: Governance deficiencies and opacity in tourism revenue systems | 0.808 | |||

| bar_2: Influence of dominant actors on local tourism benefits | 0.798 | |||

| bar_3: Structural economic limitations and underdeveloped industrial capacity | 0.810 | |||

| Disempowerment (Dsemp) | 0.863 | 0.865 | 0.617 | |

| dsemp_1: Tourism development excludes local residents in decision-making | 0.806 | |||

| dsemp_2: Tourism has not created viable alternative livelihood opportunities | 0.688 | |||

| dsemp_3: Revenue from tourism has not been used to improve local infrastructure | 0.790 | |||

| dsemp_4: Communities do not have the capacity for tourism management | 0.848 | |||

| Reduced Local Support (Lcst) | 0.766 | 0.819 | 0.518 | |

| lcst_1: I am not proud of the tourist site due to its little contribution to local development | 0.542 | |||

| lcst_2: I do not take part in environmental monitoring activities | 0.546 | |||

| lcst_3: I am dissatisfied with how tourism revenue is shared | 0.750 | |||

| lcst_4: I am not happy that tourists are visiting my community | 0.845 |

| Hypothesized Path | β | standard error | t-value | p-value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Barriers → Disempowerment | 0.192 | 0.079 | 2.430 | 0.015 | Supported |

| H2: Disempowerment → Reduced Local Support | 0.058 | 0.083 | 0.699 | 0.480 | Not Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).