Submitted:

08 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Experimental Design and Crop Management

2.3. Plant Sampling and Nutrient Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Maize Grain Yields and Plant Agronomic Traits

3.2. Nutrient Concentrations in Maize Grains

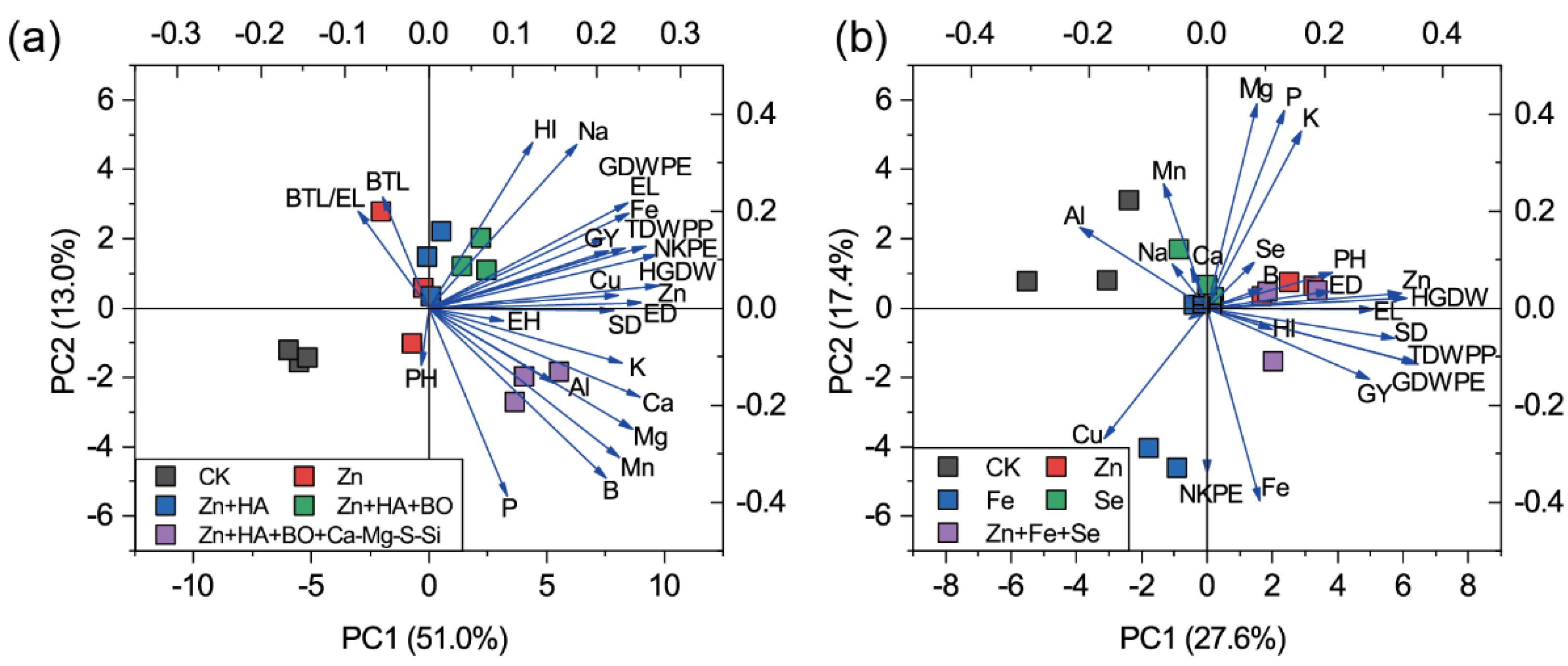

3.3. Principle Component Analysis (PCA) of Maize Yield and Nutritional Traits as Affected by Soil and Foliar Treatments

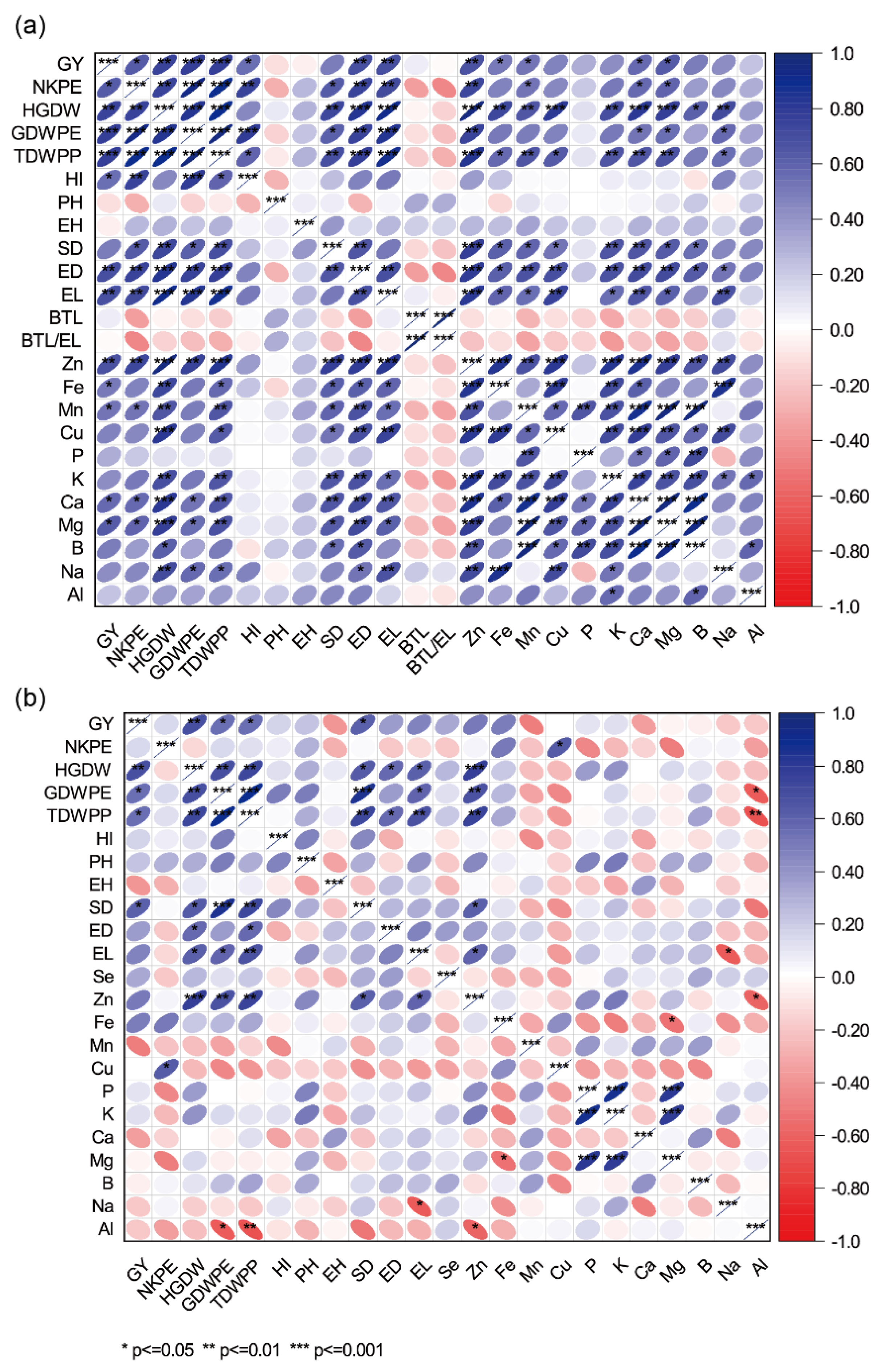

3.4. Relationships among Maize Yield and Nutritional Traits as Affected by Soil and Foliar Treatments

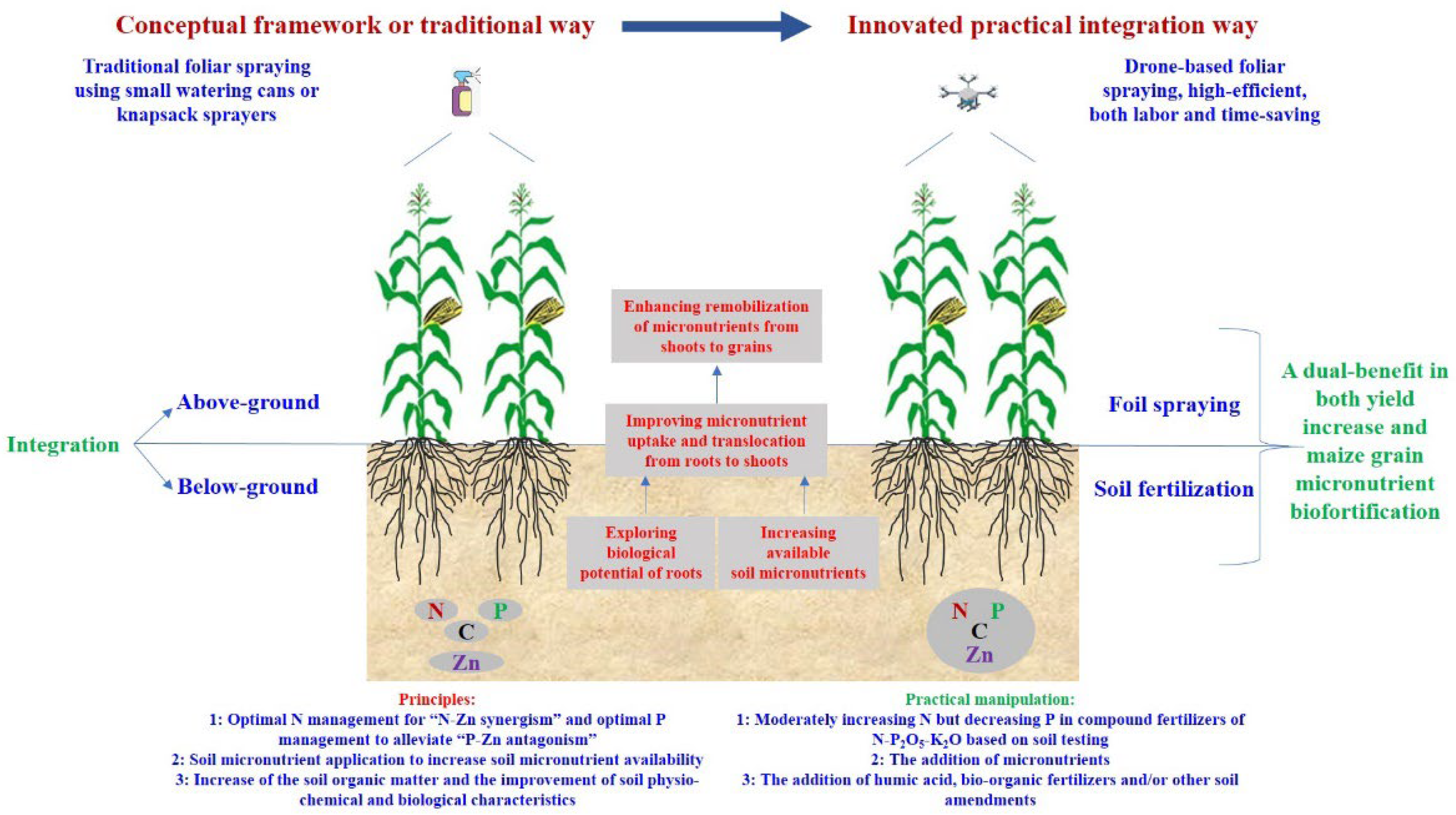

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nuss, E.T.; Tanumihardjo, S.A. Maize: a paramount staple crop in the context of global nutrition. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. F. 2010, 9, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilman, D.; Balzer, C.; Hill, J.; Befort, B.L. Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 20260–20264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodirsky, B.L.; Dietrich, J.P.; Martinelli, E.; Stenstad, A.; Pradhan, P.; Gabrysch, S.; Mishra, A.; Weindl, I.; Mouël, C.L.; Rolinski, S.; Baumstark, L.; Wang, X.; Waid, J.L.; Lotze-Campen, H.; Popp, A. The ongoing nutrition transition thwarts long-term targets for food security, public health and environmental protection. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, B.; Bausch, N.S.; Dinterman, C.; How David Hula grows 600-bushel-plus corn. SuccessfulFarming 2024, CROP NWES. Available online: https://www.agriculture.com/how-david-hula-grows-600-bushel-plus-corn-7526082#:~:text=David%20Hula%20is%20no%20stranger%20to (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Gerber, J.S.; Ray, D.K.; Makowski, D.; Butler, E.E.; Mueller, N.D.; West, P.C.; Johnson, J.A.; Polasky, S.; Samberg, L.H.; Siebert, S.; Sloat, L. Global spatially explicit yield gap time trends reveal regions at risk of future crop yield stagnation. Nat. Food 2024, 5, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202312/t20231211_1945417.html (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Luo, N.; Meng, Q.; Feng, P.; Qu, Z.; Yu, Y.; Liu, D.L.; Müller, C.; Wang, P. China can be self-sufficient in maize production by 2030 with optimal crop management. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, R.L.; West, K.P.; Black, R.E. The epidemiology of global micronutrient deficiencies. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 2, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rengel, Z.; Cakmak, I.; White, P.J. Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Plants, 4th ed.; Academic Press, Elsevier, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Sun, S.-K.; Gao, A.; Huang, X.-Y.; Wirtz, M.; Hell, R.; Zhao, F.-J. Biofortifying multiple micronutrients and decreasing arsenic accumulation in rice grain simultaneously by expressing a mutant allele of OAS-TL gene. New Phytol. 2024, 244, 2382–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.W.; Wang, Z.H.; Mao, H.; Zhao, H.B.; Huang, D.L. Increasing Se concentration in maize grain with soil- or foliar-applied selenite on the Loess Plateau in China. Field Crop. Res. 2013, 150, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Jiménez, E.; Plaza, C.; Saiz, H.; Manzano, R.; Flagmeier, M.; Maestre, F.T. Aridity and reduced soil micronutrient availability in global drylands. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.Y.; Kong, W.; Wang, L.; Xue, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, C.; Yang, S.; Li, C. Foliar Zn spraying simultaneously improved concentrations and bioavailability of Zn and Fe in maize grains irrespective of foliar sucrose supply. Agronomy 2019, 9, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Z.-F.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Ji, C.; Wang, Y.-L.; Huang, X.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Yang, J.; Song, T.; Wu, J.-C.; Guo, L.-X.; Liu, C.-B.; Han, M.-L.; Wu, Y.-R.; Yan, J.; Chao, D.-Y. A genome-wide association study identifies a transporter for zinc uploading to maize kernels. EMBO rep. 2022, 24, e55542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, P.; Du, Q.; Chen, H.; Guo, Z.; Wang, Z.; Tang, J.; Li, W. Biofortification of iron content by regulating a NAC transcription factor in maize. Science 2023, 382, 1159–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welch, R.M.; Graham, R.D.; Cakmak, I. Linking Agricultural Production Practices to Improving Human Nutrition and Health. ICN2 Second International Conference on Nutrition better nutrition better lives, Rome, Italy, November 13-15, 2013. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-as574e.pdf.

- Beal, T.; Massiot, E.; Arsenault, J.E.; Smith, M.R.; Hijmans, R.J. Global trends in dietary micronutrient supplies and estimated prevalence of inadequate intakes. PloS One 2017, 12, e0175554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, I.; Kutman, U.B. Agronomic biofortification of cereals with zinc: a review. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2018, 69, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gashu, D.; Nalivata, P.C.; Amede, T.; Ander, E.L.; Bailey, E.H.; Botoman, L.; Chagumaira, C.; Gameda, S.; Haefele, S.M.; Hailu, K.; Joy, E.J.M.; Kalimbira, A.A.; Kumssa, D.B.; Lark, R.M.; Ligowe, I.S.; McGrath, S.P.; Milne, A.E.; Mossa, A.W.; Munthali, M.; Towett, E.K.; Walsh, M.G.; Wilson, L.; Young, S.D.; Broadley, M.R. The nutritional quality of cereals varies geospatially in Ethiopia and Malawi. Nature 2021, 594, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fears, R.; ter Meulen, V.; von Braun, J. Global food and nutrition security needs more and new science. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaba2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024 – Financing to end hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition in all its forms. Rome, Italy, 2024.

- Bänziger, M.; Long, J. The potential for increasing the iron and zinc density of maize through plant-breeding. Food Nutr. Bull. 2000, 21, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.K.; Bänziger, M.; Smith, M.E. Diallel analysis of grain iron and zinc density in southern African-adapted maize inbreds. Crop Sci. 2004, 44, 2019–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.-F.; Li, X.-J.; Yan, W.; Miao, Q.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Huang, M.; Sun, J.-B.; Qi, S.-J.; Ding, Z.-H.; Cui, Z.-L. Biofortification of different maize cultivars with zinc, iron and selenium by foliar fertilizer applications. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1144514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brkić, I.; Šimić, D.; Zdunić, Z.; Jambrović, A.; Ledenčan, T.; Kovačević, V.; Kadar, I. Genotypic variability of micronutrient element concentrations in maize kernels. Cereal Res. Commun. 2004, 32, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Chen, Y.H.; Chen, X.C.; Chen, Y.L.; Yang, L.; Wang, L.F.; Qin, Y.S.; Li, M.S.; Chen, F.J.; Mi, G.H.; Gu, R.L.; Yuan, L.X. Grain mineral accumulation changes in Chinese maize cultivars released in different decades and the responses to nitrogen fertilizer. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 10, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shewry, P.R.; Pellny, T.K.; Lovegrove, A. Is modern wheat bad for health? Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewry, P.R.; Hassall, K.L.; Grausgruber, H.; Andersson, A.A.M.; Lampi, A.-M.; Piironen, V.; Rakszegi, M.; Ward, J.L.; Lovegrove, A. Do modern types of wheat have lower quality for human health? Nutr. Bull. 2020, 45, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, H.; Wang, L.; Qiao, Y.; Kong, W.; Xue, Y.; Wang, Z.; Kong, L.; Xue, Y.; Sizmur, T. Elucidating the source-sink relationships of zinc biofortification in wheat grains: a review. Food Energy Secur. 2020, 9, e243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.Y.; Li, X.J.; Qiao, Y.T.; Xue, Y.H.; Yan, W.; Ma, L.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Kong, L.A.; Xue, Y.F.; Cui, Z.L.; van der Werf, W. Dissecting the relationship between yield and mineral nutriome of wheat grains in double cropping as affected by preceding crops and nitrogen application. Field Crop. Res. 2023, 293, 108845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.E.; Sands, D.C. The breeder’s dilemma—yield or nutrition? Nat. Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 1078–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhao, Q.; Yuan, N.; Li, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, Y.; Kong, L.; Wang, Z.; Xia, H. Appropriate soil fertilization or drone-based foliar Zn spraying can simultaneously improve yield and micronutrient (particularly for Zn) nutritional quality of wheat grains. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orabi, A.A.; Mashadi, H.; Abdallah, A.; Morsy, M. Effect of zinc and phosphorus on the grain yield of corn (Zea mays L.) grown on a calcareous soil. Plant Soil 1981, 63, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Jahiruddin, M.; Islam, M.R.; Mian, M.H. The requirement of zinc for improvement of crop yield and mineral nutrition in the maize-mungbean-rice system. Plant Soil 2008, 306, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, S.; Rahmatullah, A.M.; Ahmad, R. Zinc partitioning in maize grain after soil fertilization with zinc sulfate. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2010, 12, 299–302. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.W.; Mao, H.; Zhao, H.B.; Huang, D.L.; Wang, Z.H. Different increases in maize and wheat grain zinc concentrations caused by soil and foliar applications of zinc in Loess Plateau, China. Field Crop. Res. 2012, 135, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.-F.; Yue, S.-C.; Liu, D.-Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, X.-P.; Zou, C.-Q. Dynamic zinc accumulation and contributions of pre- and/or post-silking zinc uptake to grain zinc of maize as affected by nitrogen supply. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Liu, D.; Zou, C.; Chen, X. Quantitative evaluation of the grain zinc in cereal crops caused by phosphorus fertilization. A meta-analysis. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 41, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Cao, W.; Chen, X.; Stomph, T.J.; Zou, C. Global analysis of nitrogen fertilization effects on grain zinc and iron of major cereal crops. Glob. Food Secur. 2022, 33, 100631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Wu, P.; Ling, H.; Xu, G.; Xu, F.; Zhang, Q. Plant nutriomics in China: an overview. Ann. Bot. 2006, 98, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posma, J.M.; Garcia-Perez, I.; Frost, G.; Aljuraiban, G.S.; Chan, Q.; Van Horn, L.; Daviglus, M.; Stamler, J.; Holmes, E.; Elliott, P.; Nicholson, J.K. Nutriome–metabolome relationships provide insights into dietary intake and metabolism. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, H.Y.; Li, X.J.; Qiao, Y.T.; Xue, Y.H.; Yan, W.; Xue, Y.F.; Cui, Z.L.; Silva, J.V.; van der Werf, W. Diversification of wheat-maize double cropping with legume intercrops improves nitrogen-use efficiency: Evidence at crop and cropping system levels. Field Crop. Res. 2024, 307, 109262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, I.; Kalayci, M.; Kaya, Y.; Torun, A.A.; Aydin, N.; Wang, Y.; Arisoy, Z.; Erdem, H.; Yazici, A.; Gokmen, O.; Ozturk, L.; Horst, W.J. Biofortification and localization of zinc in wheat grain. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 9092–9102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, I.; Pfeiffer, W.H.; McClafferty, B. Biofortification of durum wheat with zinc and iron. Cereal Chem. 2010, 87, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloway, B.J. Soil factors associated with zinc deficiency in crops and humans. Environ. Geochem. Health 2009, 31, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, I. Role of zinc in protecting plant cells from reactive oxygen species. New Phytol. 2000, 146, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karim, M.R.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Zhao, R.R.; Chen, X.P.; Zhang, F.S.; Zou, C.Q. Alleviation of drought stress in winter wheat by late foliar application of zinc, boron, and manganese. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2012, 175, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, A.U.; Ahmad, A.U.H.; Ullah, S. Influence of zinc application through seed treatment and foliar spray on growth, productivity and grain quality of hybrid maize. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2014, 24, 1494–1503. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C.; EI-Sawah, A.M.; Ali, D.F.I.; Alhaj Hamoud, Y.; Shaghaleh, H.; Sheteiwy, M.S. The integration of bio and organic fertilizers improve plant growth, grain yield, quality and metabolism of hybrid maize (Zea mays L.). Agronomy 2020, 10, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampong, K.; Thilakaranthna, M.S.; Gorim, L.Y. Understanding the role of humic acids on crop performance and soil health. Front. Agron. 2022, 4, 848621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud Odah, M.; Makki Naser, K. Effect of humic acid and levels of zinc and boron on chemical behavior of zinc in calcareous soil. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 6, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.-F.; Zhang, H.; Liu, K.-C.; Xia, H.-Y.; Gao, Y.-B.; Wang, Q.-C.; Wen, L.-Y.; Kong, W.-L.; Zhang, H.-H.; Fu, X.-Q.; Qi, S.-J.; Li, Z.-X. Analysis of major elements in grain of the popularized maize varieties in Huanghuaihai Plain. J. Maize Sci. 2017, 25, 56–62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Qiao, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Xue, Y.; Xia, H. Effects of foliar spraying of excessive selenium on yields and contents of selenium and mineral elements of maize. J. Nuclear Agric. Sci. 2021, 35, 2841–2849. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bouis, H.E.; Welch, R.M. Biofortification-a sustainable agricultural strategy for reducing micronutrient malnutrition in the global south. Crop Sci. 2010, 50, S20–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouis, H.E.; Hotz, C.; McClafferty, B.; Meenakshi, J.V.; Pfeiffer, W.H. Biofortification: a new tool to reduce micronutrient malnutrition. Food Nutr. Bull. 2011, 32, S31–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangoulis, J.C.R.; Knez, M. Biofortification of major crop plants with iron and zinc - achievements and future directions. Plant Soil 2022, 474, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experimental Treatment | Site | Geographic Coordinates | Soil Type |

pH (2.5:1 Water: Soil Ratio) |

Organic Matter (g/kg) |

Total Nitrogen (g/kg) |

Olsen-P (mg/kg) |

Exchangeable K (mg/kg) |

DTPA-Extractable Zn (mg/kg) |

| Soil fertilization | Laoling | 117°0’E, 37°41’N | Calcareous alluvial soil | 8.5 | 13.7 | 1.2 | 29.1 | 133.5 | 0.8 |

| Foliar spraying | Binzhou | 117°50’E, 37°19’N | Calcareous alluvial soil | 8.4 | 15.5 | 1.1 | 21.8 | 108.7 | 0.7 |

| Treatment | Fertilizer broadcast and rotary tillage (0-20 cm) prior to maize planting | Seed and fertilizer sown together |

| Control (CK) | Rotary tillage with no fertilizer | A controlled-release formulated fertilizer (N-P2O5-K2O: 28-5-7, 600 kg/ha) |

| Zn | ZnSO4·H2O (30 kg/ha) | A controlled-release formulated fertilizer (N-P2O5-K2O: 28-5-7, 600 kg/ha) |

| Zn+humic acid (Zn+HA) | ZnSO4·H2O (30 kg/ha) + humic acid (organic matter: 85%, 750 kg/ha) | A controlled-release formulated fertilizer (N-P2O5-K2O: 28-5-7, 600 kg/ha) |

| Zn+humic acid+bio-organic fertilizers (Zn+HA+BO) | ZnSO4·H2O (30 kg/ha) + humic acid (organic matter: 85%, 750 kg/ha) + a bio-organic fertilizer with an effective count of viable bacterial ≥ 200 million cfu/g and an organic matter content ≥ 60% (1500 kg/ha) | A controlled-release formulated fertilizer (N-P2O5-K2O: 28-5-7, 600 kg/ha) |

| Zn+humic acid+bio-organic+Ca-Mg-S-Si complex fertilizers (Zn+HA+BO+Ca-Mg-S-Si) | ZnSO4·H2O (30 kg/ha) + humic acid (organic matter: 85%, 750 kg/ha) + a bio-organic fertilizer with an effective count of viable bacterial ≥ 200 million cfu/g and an organic matter content ≥ 60% (1500 kg/ha) + a calcium (Ca)-magnesium (Mg)-sulfur (S)-silicon (Si) fertilizer (CaO: 25.0%, MgO: 8.0%, S: 8.0%, SiO2: 10.0%, Zn: 0.7%, B: 0.5%, Mo: 0.05%, functional sub-stance: 0.05%, 300 kg/ha) | A controlled-release formulated fertilizer (N-P2O5-K2O: 28-5-7, 600 kg/ha) |

| Experiment | Treatment | GY (t/ha) | NKPE | HGDW (g) | GDWPE (g) | TDWPP (g) | HI | PH (cm) | EH (cm) | SD (mm) | ED (mm) | EL (cm) | BTL (cm) | BTL/EL (%) |

| Soil fertilization |

CK | 11.3b 1 | 544.3b | 31.4d | 179.1b | 332.9b | 0.54b | 265.3a | 93.3a | 30.7b | 49.3b | 16.7b | 1.0a | 6.0a |

| Zn | 12.8ab | 629.7a | 34.2c | 239.8a | 405.2a | 0.59a | 264.2a | 96.8a | 32.2ab | 51.3a | 19.4a | 1.1a | 5.4a | |

| Zn+HA | 13.2a | 617.0a | 35.3b | 232.3a | 408.0a | 0.57ab | 262.0a | 97.7a | 32.2ab | 51.9a | 20.1a | 1.1a | 5.6a | |

| Zn+HA+BO | 12.7ab | 628.7a | 36.3ab | 236.5a | 408.5a | 0.58a | 264.2a | 97.0a | 33.1a | 52.4a | 20.1a | 0.9a | 4.4a | |

| Zn+HA+BO+Ca-Mg-S-Si | 13.9a | 636.7a | 37.0a | 239.1a | 423.7a | 0.56ab | 267.7a | 99.0a | 33.5a | 53.2a | 20.4a | 0.9a | 4.4a | |

| Drone-based foliar spraying |

CK | 11.5b | 602.0a | 30.3d | 178.3b | 339.2c | 0.53a | 248.2a | 110.7a | 28.9c | 50.5c | 16.6b | - | - |

| Zn | 13.6a | 589.7a | 33.3a | 203.5a | 376.3ab | 0.54a | 256.5a | 110.8a | 32.0a | 51.5bc | 17.8a | - | - | |

| Fe | 13.2a | 633.0a | 31.2c | 193.2a | 361.7b | 0.53a | 248.8a | 110.5a | 30.2b | 51.6bc | 17.4ab | - | - | |

| Se | 13.4a | 570.0a | 32.2b | 192.7a | 362.8b | 0.53a | 244.0a | 109.7a | 31.2ab | 52.4ab | 17.0ab | - | - | |

| Zn+Fe+Se | 13.9a | 629.3a | 33.1a | 200.6a | 381.9a | 0.53a | 255.0a | 109.2a | 31.5a | 53.7a | 17.3ab | - | - |

| Experiment | Treatment | Se (µg/kg) | Zn (mg/kg) | Fe (mg/kg) | Mn (mg/kg) | Cu (mg/kg) | P (g/kg) | K (g/kg) | Ca (mg/kg) | Mg (g/kg) | B (mg/kg) | Na (mg/kg) | Al (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil fertilization |

CK | - | 9.9c 1 | 16.8c | 2.4c | 1.4b | 2.5b | 3.6b | 66.5d | 0.9c | 1.1b | 3.0d | 5.8a |

| Zn | - | 14.0b | 16.9c | 2.9b | 1.4b | 2.4b | 3.8b | 77.1d | 1.0b | 1.2b | 5.9cd | 6.4a | |

| Zn+HA | - | 15.4b | 20.4b | 2.84b | 3.3a | 2.2b | 3.8b | 92.1c | 1.0b | 1.2b | 10.1b | 5.8a | |

| Zn+HA+BO | - | 20.0a | 23.7a | 2.78bc | 3.4a | 2.3b | 4.4a | 107.2b | 1.0b | 1.3b | 15.2a | 6.9a | |

| Zn+HA+BO+Ca-Mg-S-Si | - | 20.8a | 21.3b | 3.9a | 3.5a | 2.9a | 4.5a | 152.4a | 1.3a | 2.1a | 8.6bc | 7.6a | |

| Drone-based foliar spraying |

CK | 93.7c | 18.2b | 20.4c | 5.1a | 3.1a | 3.4a | 6.7a | 194.4a | 1.2a | 3.2a | 31.5a | 7.7a |

| Zn | 73.7c | 31.2a | 23.9b | 4.3a | 2.9a | 3.6a | 6.9a | 202.3a | 1.2a | 3.1a | 25.1ab | 6.5a | |

| Fe | 60.8c | 19.0b | 30.3a | 4.1a | 3.2a | 2.9b | 5.6b | 175.6a | 1.0a | 3.3a | 20.1b | 6.7a | |

| Se | 803.1a | 19.4b | 21.1bc | 4.1a | 2.9a | 3.3ab | 6.6a | 229.9a | 1.1a | 3.4a | 26.5ab | 7.8a | |

| Zn+Fe+Se | 468.1b | 28.9a | 27.5a | 4.4a | 3.1a | 3.5a | 7.0a | 146.4a | 1.1a | 3.4a | 29.1ab | 6.2a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).