Submitted:

09 April 2025

Posted:

10 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

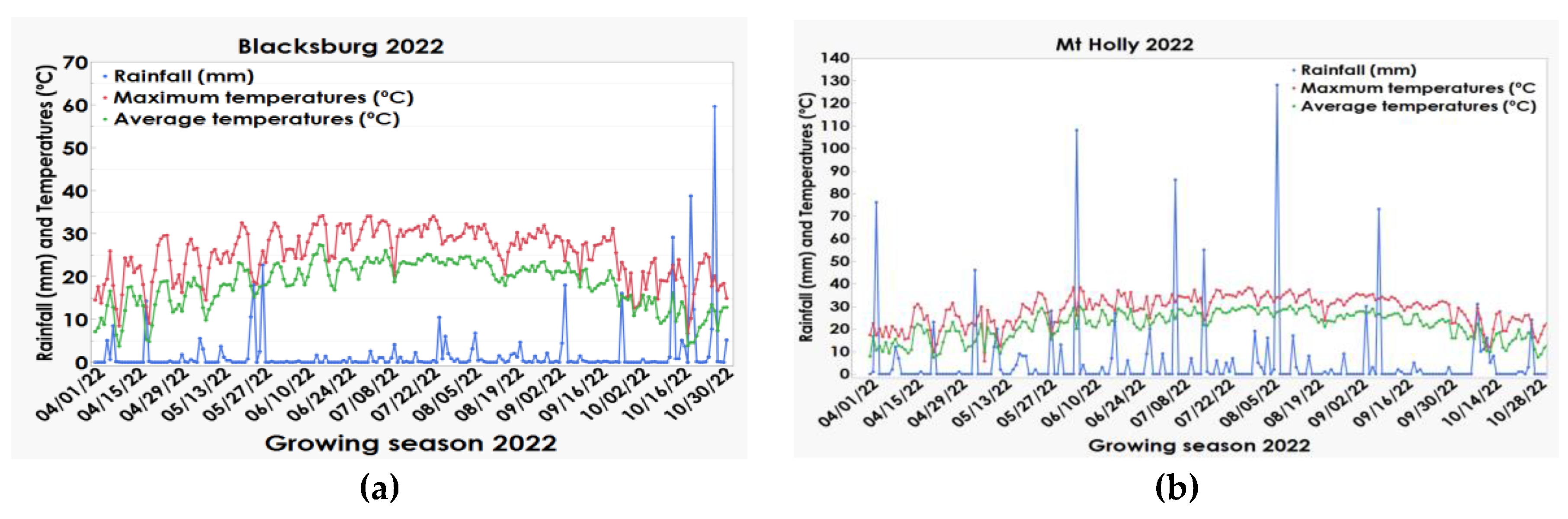

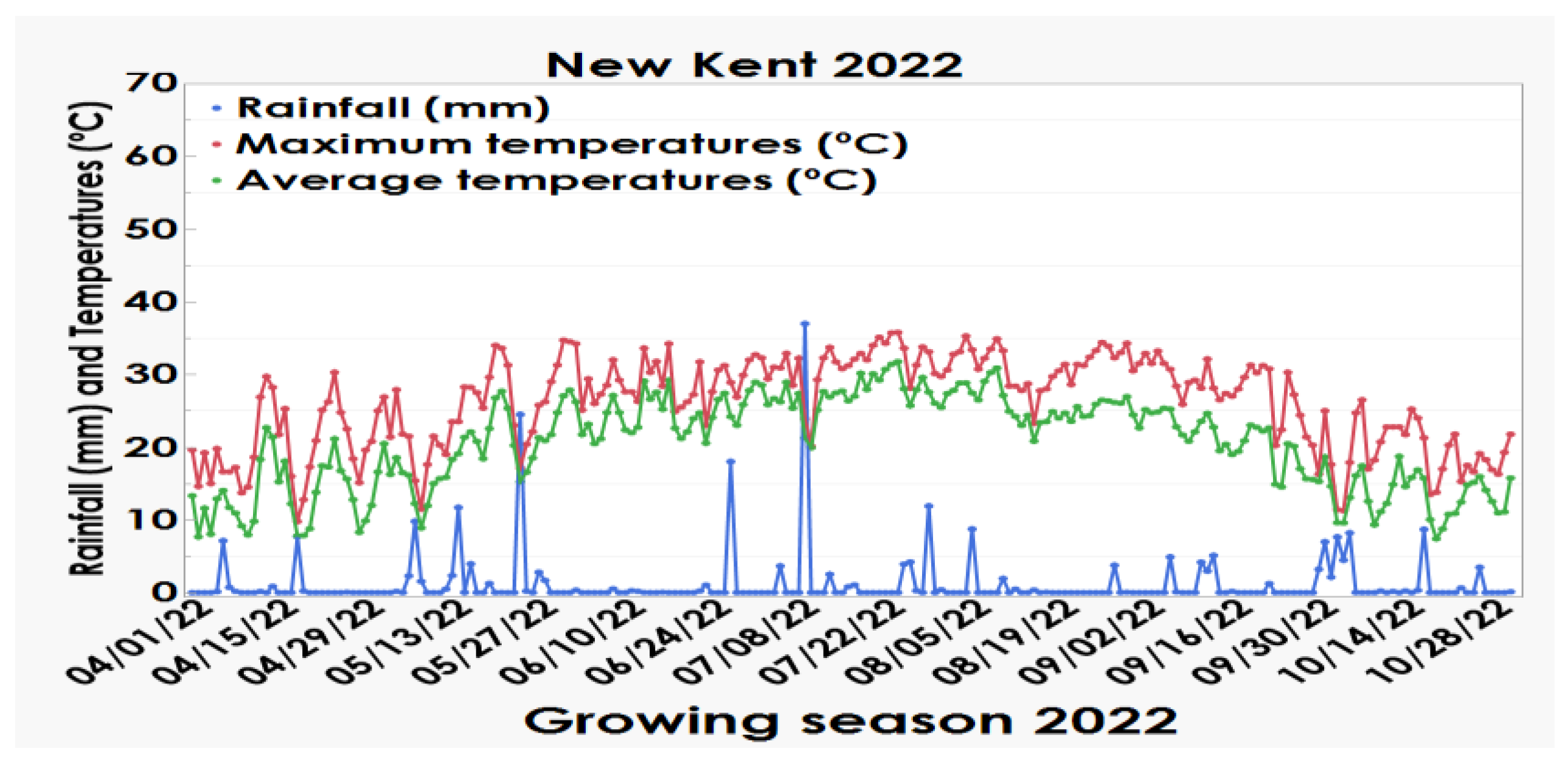

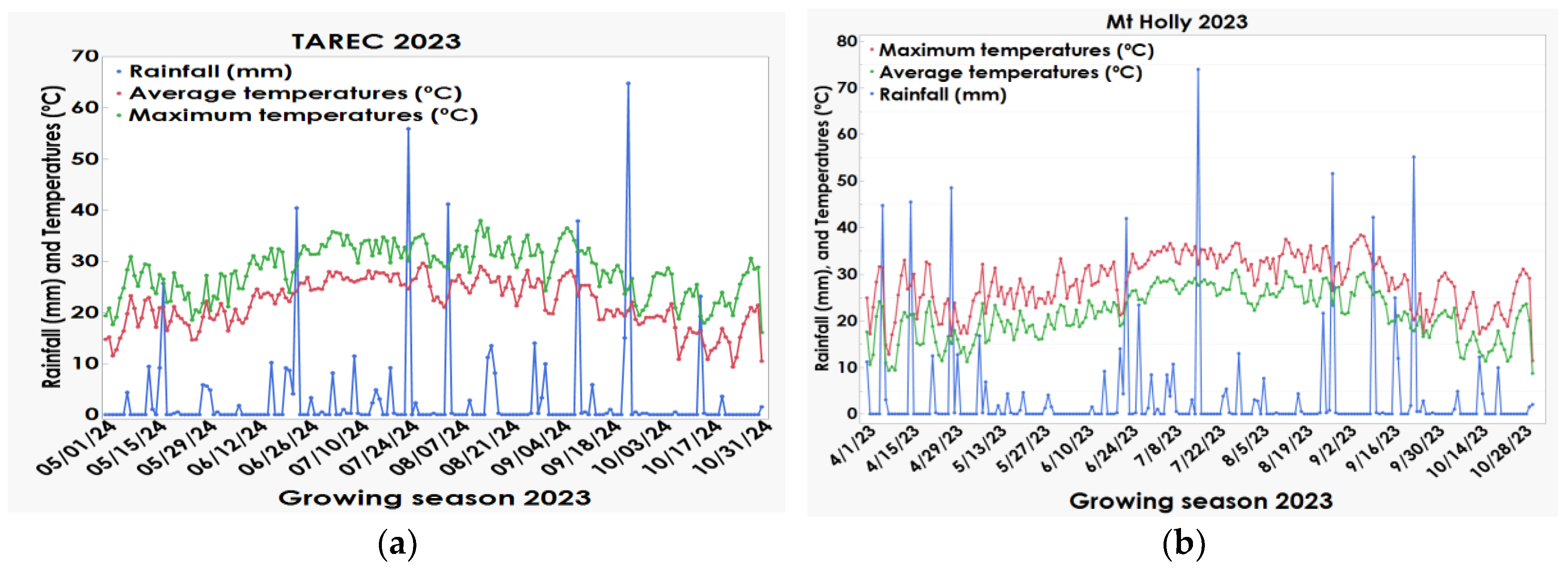

2.1. Study Site Characterization

2.2. Site Characterization

2.3. Experimental Details

2.4. Experimental Design and Treatments

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Data availability

Conflict of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACMS | Adaptive Maize Management Systems |

| CEC | Cation exchange capacity |

| VCE | Virginia Cooperative Extension |

| TAREC | Tidewater Agricultural Research and Extension Center |

References

- UNESCO. ““World Population Prospects”.” United Nations. (accessed March 4, 2025).

- D. Hemathilake and D. Gunathilake, “Agricultural productivity and food supply to meet increased demands,” in Future foods: Elsevier, 2022, pp. 539-553.

- J. A. Burney, S. J. Davis, and D. B. Lobell, “Greenhouse gas mitigation by agricultural intensification,” Proceedings of the national Academy of Sciences, vol. 107, no. 26, pp. 12052-12057, 2010. [CrossRef]

- J. Pretty and Z. P. Bharucha, “Sustainable intensification in agricultural systems,” Annals of botany, vol. 114, no. 8, pp. 1571-1596, 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. G. Cassman, “Ecological intensification of cereal production systems: yield potential, soil quality, and precision agriculture,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 96, no. 11, pp. 5952-5959, 1999.

- K. G. Cassman, A. Dobermann, and D. T. Walters, “Agroecosystems, nitrogen-use efficiency, and nitrogen management,” AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 132-140, 2002.

- J. A. Foley et al., “Solutions for a cultivated planet,” Nature, vol. 478, no. 7369, pp. 337-342, 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Ruffo, L. F. Gentry, A. S. Henninger, J. R. Seebauer, and F. E. Below, “Evaluating management factor contributions to reduce corn yield gaps,” Agronomy Journal, vol. 107, no. 2, pp. 495-505, 2015. [CrossRef]

- N. D. Mueller, J. S. Gerber, M. Johnston, D. K. Ray, N. Ramankutty, and J. A. Foley, “Closing yield gaps through nutrient and water management,” Nature, vol. 490, no. 7419, pp. 254-257, 2012. [CrossRef]

- L. S. Rathore, M. Kumar, R. T. McNider, N. Magliocca, and W. Ellenburg, “Contrasting corn acreage trends in the Midwest and Southeast: The role of yield, climate, economics, and irrigation,” Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, vol. 18, p. 101373, 2024.

- NCGA. “The 60th Annual Yield Contest.” (accessed 20, 2025).

- M. S. Reiter, W. H. Frame, and W. E. Thomason, “Consider Your Whole System: Nitrogen and Sulfur Leaching Potential in Virginia,” 2018.

- W Hunter Frame. “Excess rains and leaching of nitrogen, potassium and sulfur https://blogs.ext.vt.edu/ag-pest-advisory/files/2015/07/Excess-rains-and-leaching-of-nitrogen.pdf.” (accessed 20, 2025).

- I. A. Ciampitti and T. J. Vyn, “Physiological perspectives of changes over time in maize yield dependency on nitrogen uptake and associated nitrogen efficiencies: A review,” Field Crops Research, vol. 133, pp. 48-67, 2012. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Ransom et al., “Improving publicly available corn nitrogen rate recommendation tools with soil and weather measurements,” Agronomy Journal, vol. 113, no. 2, pp. 2068-2090, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Barker and J. Sawyer, “Variable rate nitrogen management in corn: Response in two crop rotations,” Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, vol. 72, no. 3, pp. 183-190, 2017. [CrossRef]

- W. H. Frame, “Excess rains and leaching of nitrogen, potassium and sulfur https://blogs.ext.vt.edu/ag-pest-advisory/files/2015/07/Excess-rains-and-leaching-of-nitrogen.pdf,” 2024.

- N. K. Fageria and V. C. Baligar, “Enhancing nitrogen use efficiency in crop plants,” Advances in agronomy, vol. 88, pp. 97-185, 2005. [CrossRef]

- I. Holford, “Soil phosphorus: its measurement, and its uptake by plants,” Soil Research, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 227-240, 1997.

- J. L. Kovar and N. Claassen, “Soil-root interactions and phosphorus nutrition of plants,” Phosphorus: agriculture and the environment, vol. 46, pp. 379-414, 2005.

- E. Truog, “The determination of the readily available phosphorus of soils 1,” Agronomy Journal, vol. 22, no. 10, pp. 874-882, 1930.

- A. N. Sharpley, “Dependence of runoff phosphorus on extractable soil phosphorus,” Wiley Online Library, 0047-2425, 1995.

- S. Donohue and S. Heckendorn, “Soil test recommendations for Virginia,” Virginia Cooperative Extension Service Publ, vol. 834, pp. 23-27, 1994.

- M. M. Alley, M. E. Martz, P. H. Davis, and J. Hammons, “Nitrogen and phosphorus fertilization of corn,” 2009.

- J. Camberato, S. Casteel, and K. Steinke, “Sulfur deficiency in corn, soybean, alfalfa, and wheat,” ed: Purdue University Extension. https://www. extension. purdue. edu/extmedia/AY …, 2022.

- K. Steinke, J. Rutan, and L. Thurgood, “Corn response to nitrogen at multiple sulfur rates,” Agronomy Journal, vol. 107, no. 4, pp. 1347-1354, 2015. [CrossRef]

- D. S. Mueller et al., “Corn yield loss estimates due to diseases in the United States and Ontario, Canada, from 2016 to 2019,” Plant Health Progress, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 238-247, 2020.

- J. M. Ward, E. L. Stromberg, D. C. Nowell, and F. W. Nutter Jr, “Gray leaf spot: a disease of global importance in maize production,” Plant disease, vol. 83, no. 10, pp. 884-895, 1999. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Wise et al., “Meta-analysis of yield response of foliar fungicide-treated hybrid corn in the United States and Ontario, Canada,” PLoS One, vol. 14, no. 6, p. e0217510, 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Wise and D. Mueller, “Are fungicides no longer just for fungi? An analysis of foliar fungicide use in corn,” APSnet Features. doi, vol. 10, 2011. [CrossRef]

- K. Wise, “Fungicide efficacy for control of corn diseases,” Crop Prot Network, 2018.

- T. F. Morris et al., “Strengths and limitations of nitrogen rate recommendations for corn and opportunities for improvement,” Agronomy Journal, vol. 110, no. 1, pp. 1-37, 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Ades, N. Welton, and G. Lu, “Introduction to mixed treatment comparisons,” Bristol: MRC Health Services Research Collaboration, 2007.

- A. Abaye et al., “Virginia Cooperative Extension Agronomy Handbook 2023,” 2023.

- E. Bendfeldt, “Agronomy Handbook 2023: Part VII. Soil Health Management,” 2023.

- K. T. Klasson, “A Non-iterative Approximation for Critical Value for Dunnett’s Test,” ARS USDA, Southern Re-gional Research Center. https://www. ars. usda. gov/ARSUserFiles/60540520/CriticalValuesForDunnett. pdf, 2023.

- K. Subedi and B. Ma, “Assessment of some major yield-limiting factors on maize production in a humid temperate environment,” Field crops research, vol. 110, no. 1, pp. 21-26, 2009. [CrossRef]

- D. Franzen et al., “Performance of Selected Commercially Available Asymbiotic N-fixing Products in the North Central Region. North Dakota State University,” ed, 2024.

- H. Naseem and A. Bano, “Role of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and their exopolysaccharide in drought tolerance of maize,” Journal of Plant Interactions, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 689-701, 2014. [CrossRef]

- C. Sible and F. Below, “Role of Biologicals in Enhancing Nutrient Efficiency in Corn and Soybean,” Crops & Soils, vol. 56, no. 2, pp. 13-19, 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. J. Mahoney, J. H. Klapwyk, G. A. Stewart, W. S. Jay, and D. C. Hooker, “Agronomic management strategies to reduce the yield loss associated with spring harvested corn in Ontario,” American Journal of Plant Sciences, vol. 6, no. 02, p. 372, 2015. [CrossRef]

- C. Bradley and K. Ames, “Effect of foliar fungicides on corn with simulated hail damage,” Plant Disease, vol. 94, no. 1, pp. 83-86, 2010. [CrossRef]

| Location | Year | P | K | Ca | Mg | pH† | Est CEC‡ |

| ....................... kg ha-1 ................. | 1:1 | meq/100g | |||||

| Blacksburg irrigated and non-irrigated | 2022 | 69 | 289 | 1283 | 312 | 6.1 | 6.0 |

| Mt Holly non-irrigated | 2022 | 72 | 149 | 1129 | 301 | 6.8 | 3.9 |

| New Kent irrigated | 2022 | 38 | 129 | 731 | 133 | 5.5 | 3.6 |

| New Kent non-irrigated | 2022 | 61 | 121 | 867 | 169 | 5.6 | 4.1 |

| Mt Holly irrigated | 2022 | 74 | 164 | 563 | 107 | 5.0 | 4.3 |

| Mt Holly non-irrigated | 2023 | 58 | 214 | 696 | 173 | 6.3 | 3.0 |

| Mt Holly irrigated | 2023 | 54 | 161 | 1031 | 217 | 6.3 | 3.7 |

| Suffolk irrigated and non-irrigated | 2023 | 56 | 82 | 665 | 74 | 6.6 | 1.9 |

| Treatments | +P and K | +Sidedress N | +CoRon® | +Headline® | +Biological |

| Management level | Standard management (One treatment added at a time into standard management check) | ||||

| †Standard management check | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| +P and K | ✓ | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| +Sidedress N | NO | ✓ | NO | NO | NO |

| +CoRon® | NO | NO | ✓ | NO | NO |

| +Headline® | NO | NO | NO | ✓ | NO |

| +Biological | NO | NO | NO | NO | ✓ |

| Intensive management (One treatment taken off at a time from Intensive management check) | |||||

| ‡Intensive management check | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| -P and K | NO | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| -Sidedress N | ✓ | NO | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| -CoRon® | ✓ | ✓ | NO | ✓ | ✓ |

| -Headline® | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | NO | ✓ |

| -Biological | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | NO |

| Year | --------------------------------------------2022-------------------------------------- | -----------------------------2023------------------ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Blacksburg | New Kent | Mt Holly | Mt Holly | Suffolk | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Irrigation Status | Irrigated | Non-Irrigated | Irrigated | Non-Irrigated | Irrigated | Non-Irrigated | Irrigated | Non-Irrigated | Irrigated | Non-Irrigated | ||||||||||||||||||

| Standard management compared to the †Standard management check | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Management level | ------------------------------------------------------------------- Grain yield, kg ha-1 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| +Biological | 10354 | 11111 | 19188 | 15233 | 13201 | 9750 | 15472 | 11527 | 15454 | 14238* | ||||||||||||||||||

| +CoRon® | 8755* | 7900 | 17834 | 16902 | 14194 | 9441 | 15455 | 13790 | 14262 | 10109 | ||||||||||||||||||

| +Headline® | 10113 | 7936 | 18445 | 16263 | 13847 | 9666 | 14300* | 11786 | 16122* | 11692 | ||||||||||||||||||

| +P and K | 9374 | 9729 | 16317 | 18022 | 12696 | 9845 | 14144* | 12693 | 14651 | 13659* | ||||||||||||||||||

| +Sidedress N | 8233* | 9166 | 18923 | 16855 | 13464 | 10285 | 14718* | 13245 | 14204 | 15545* | ||||||||||||||||||

| †Standard management check | 11195 | 8149 | 18202 | 15751 | 13789 | 9832 | 16624 | 14529 | 13962 | 8685 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Intensive management Compared to the ‡Intensive management check | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Management level | ------------------------------------------------------------------- Grain yield, kg ha-1 ------------------------------------------- | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| -Biological | 9207 | 11513 | 18770 | 16086 | 13665 | 10145 | 13411 | 12706 | 16226* | 12810 | ||||||||||||||||||

| -CoRon® | 10768 | 11240 | 17963 | 16675 | 13542 | 8584 | 13266 | 12711 | 15531 | 12839 | ||||||||||||||||||

| -Headline® | 10115 | 9161 | 18212 | 16398 | 12826 | 10345 | 12800 | 13093 | 15522 | 11610 | ||||||||||||||||||

| -P and K | 9461 | 7702* | 17744 | 17287 | 12488 | 9131 | 13182 | 13311 | 16337* | 12071 | ||||||||||||||||||

| -Sidedress N | 7337 | 9031 | 18743 | 15859 | 12570 | 9711 | 13186 | 13569 | 16023 | 14639* | ||||||||||||||||||

| ‡Intensive management check | 10286 | 10944 | 18138 | 18743 | 13029 | 9437 | 13373 | 13179 | 14645 | 12810 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Management level | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‡Intensive management check | 10286 | 10944 | 18138 | 18743 | 13029 | 9437 | 13373 | 13179 | 14645 | 12810 | ||||||||||||||||||

| †Standard management check | 11195 | 8149 | 18202 | 15751 | 13789 | 9832 | 16624 | 14529 | 13962 | 8685 | ||||||||||||||||||

| P-value | 0.608 | 0.051 | 0.944 | 0.004 | 0.343 | 0.694 | 0.041 | 0.233 | 0.334 | 0.357 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Irrigation impact, % | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Intensive management check | -6% | -3% | 38% | 1.5% | 14% | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard management check | 37% | 16% | 40% | 14% | 61% | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Irrigation | -----------------------------Irrigated---------------------------- | ---------------------------Non-irrigated------------------------- | |||||||||||

| Year | -----------2022----------- | ---------2023------- | -----------2022----------- | ---------2023------ | |||||||||

| Site | Blacksburg | New Kent | Mt Holly | Mt Holly | Tidewater | Avg | Blacksburg | New Kent | Mt Holly | Mt Holly | Tidewater | Avg | |

| Standard management compared to the †Standard management check, % | |||||||||||||

| +Biological | 92 | 105 | 96 | 93 | 104 | 98 | 136 | 97 | 99 | 79 | 164 | 115 | |

| +CoRon® | 78 | 98 | 103 | 93 | 102 | 95 | 97 | 107 | 96 | 95 | 116 | 102 | |

| +Headline® | 90 | 101 | 100 | 86 | 115 | 99 | 97 | 103 | 98 | 81 | 135 | 103 | |

| +P and K | 84 | 90 | 92 | 85 | 105 | 91 | 119 | 114 | 100 | 87 | 157 | 116 | |

| +Sidedress N | 74 | 104 | 98 | 89 | 102 | 93 | 112 | 107 | 105 | 91 | 179 | 119 | |

| Mean | 95 | 111 | |||||||||||

| Intensive management compared to ‡Intensive management check % | |||||||||||||

| -Biological | 90 | 98 | 105 | 100 | 111 | 101 | 105 | 86 | 108 | 96 | 120 | 103 | |

| -CoRon® | 105 | 94 | 104 | 99 | 106 | 102 | 103 | 89 | 91 | 96 | 120 | 100 | |

| -Headline® | 98 | 95 | 98 | 96 | 106 | 99 | 84 | 87 | 110 | 99 | 108 | 98 | |

| -P and K | 92 | 93 | 96 | 99 | 112 | 98 | 70 | 92 | 97 | 101 | 113 | 95 | |

| -Sidedress N | 71 | 98 | 96 | 99 | 109 | 95 | 83 | 85 | 103 | 103 | 137 | 102 | |

| Mean | 99 | 100 | |||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).