1. Introduction

During the 20th century the urbanization lead the creation of a new kind of cities, known as compact cities [

1]. Compact cities and eco-cities are among the most promoted models of sustainable urban design and represent key approaches in sustainable urbanism [

2]. Compact cities are defined by extensive areas of buildings and paved surfaces, leaving limited space for greenery [

3].

This could pose a significant problem for city residents, as they would lose the valuable ecosystem services that trees and green spaces offer. As defined by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment [

4,

5], ecosystem services are the multiple benefits provided by ecosystems to mankind, and the same document divides them into four categories [

6]:

Supply services, covering products obtainable from ecosystems;

Regulatory services, which are the benefits obtained by active processes in different ecosystems;

Cultural services, covering all non-material benefits obtained by ecosystems;

Life support services, which are the services necessary for the production of all other ecosystem services.

In the urban context, the benefits refer to supply services are not so many, while the benefits related to regulatory, cultural and life support services have a predominant role. An example is the mitigation of the Urban Heat Island UHI effect by the vegetation, which dissipates energy through evapotranspiration and acts as a thermal insulator for buildings when present on green roofs and facades [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Another significant benefit of urban greenery is its ability to mitigate air pollution through two primary mechanisms. First, it involves the storage of carbon within plant biomass [

11]. Second, vegetation, particularly trees, acts as a natural filter by capturing particulate matter from the air [

12]. Vegetation also plays a crucial role in improving rainwater management through a threefold process, particularly in the case of trees [

13]: rainwater is partially intercepted by the canopy, partially flows along the stems/trunks of various species, and partially infiltrates into the ground, avoiding the formation of intense runoff, which is significantly exacerbated in urban areas by impervious soil [

14]. In addition, the presence of green areas in urbanised environments makes it possible to satisfy the important recreational and social need by making cities more liveable and raising the population’s awareness of environmental issues [

15]. In fact, although the available literature on this topic is still limited, recent studies indicate that exposure to green spaces significantly enhances individuals’ psychophysical well-being [

16]. This conclusion is supported by the evaluation of physiological indicators such as brain activity in the prefrontal cortex, heart rate, blood pressure, levels of adrenaline and noradrenaline in urine, as well as various psychological indices [

17,

18,

19].

The planning and management of these natural areas in the city is becoming increasingly important, not only for the maintenance of the above-mentioned services, but also for the protection of biodiversity and for their active role in the establishment of ecological networks. As reported by [

20], ecological networks in urban and rural areas are crucial, as they provide the only means to establish ecological corridors, promote connectivity, and enable the movement of wildlife in these fragmented landscapes. In this regard, [

21] also argue that urbanization, in addition to being a threat to global biodiversity, can surprisingly also be crucial for the conservation of some species, especially through management, conservation and planning of urban green spaces.

The presence of vegetation in urban areas, while offering numerous benefits to residents, also brings certain drawbacks or ecosystem disservices (EDS). EDS are often grouped into categories that highlight their negative effects [

22]. These include health-related issues (e.g., disease spread, allergens), economic and financial costs (e.g., soil degradation, damage to infrastructure), safety and security challenges (e.g., storm damage, perceived crime, and wildlife conflicts), as well as aesthetic impacts (e.g., obstructed views, undesirable flora). EDS associated with trees may have the most significant impact [

23,

24] and include the production of pollen and other substances that can trigger allergies, such as exacerbating respiratory problems in sensitive [

25], falling fruits and branches [

26], the conflict with urban infrastructure (e.g. trees can block traffic signs, streetlights, and views, reducing visibility and safety), the intrusion and outcropping of roots that can break sidewalks, roads and building foundations, and the risk of uprooting and crashing, especially in high winds. The latter occurrences are often aggravated by various stresses, particularly abiotic factors, to which city trees are frequently exposed. These include soils compaction and paving over the root zone that reduce gas exchange and rainwater infiltration, planting in soils poor in organic matter, high temperatures, pollution, and incorrect management activities, especially pruning (

Figure 1). In this regard, appropriate tree pruning minimizes interference with structures, enhances wind tolerance, and decreases the likelihood of branch failures that could endanger people or property. Conversely, improper pruning techniques not only compromise a tree’s aesthetic appeal but also create extensive wounds that heal slowly [

27]. These wounds can become entry points for harmful pathogens, such as parasitic fungi. Some fungi, like

Fomes fomentarius, may undermine the tree’s structural integrity, while others, such as

Armillaria species, can diminish its overall vitality [

28].

The annual ISTAT (Italian Institute of Statistics) reports contain data on felled trees in Italy’s provincial capitals that are particularly useful for quantifying the impact of disruptions caused by falling branches or entire trees. In the latest published report referring to data from 2021, for example, it is reported that 27,960 trees were felled in that year, with 21,580 (approximately 77% of the total) removed due to the risk of falling. The 2023 Statistical Yearbook of the Italian Fire Brigade (

https://www.vigilfuoco.it/chi-siamo/le-statistiche/annuari-delle-statistiche-ufficiali-del-corpo-nazionale-dei-vigili-del-fuoco) reveals that securing unstable trees ranks fifth among the most frequent type of technical rescue operation. In particular, nationwide interventions required for dangerous trees show a steadily increasing trend over the ten-year period from 2014 to 2023, with the exception of the period 2020/2021. The number of interventions rose from about 3,500 in 2014 to almost 68,000 in 2023, with an increase of more than 35% from 2022 to 2023. These statistics underscore the growing significance of tree-related hazards in urban environments, highlighting the urgent need for improved urban forestry management strategies and risk assessment protocols to ensure public safety while preserving the valuable ecosystem services provided by urban trees.

A study was conducted to analyse weather-related tree falls in urban areas. The aim was to identifying and analysing the weather factors that most influence tree falls, in order to define practical guidelines for managing the risk of damage to people and property.

2. Materials and Methods

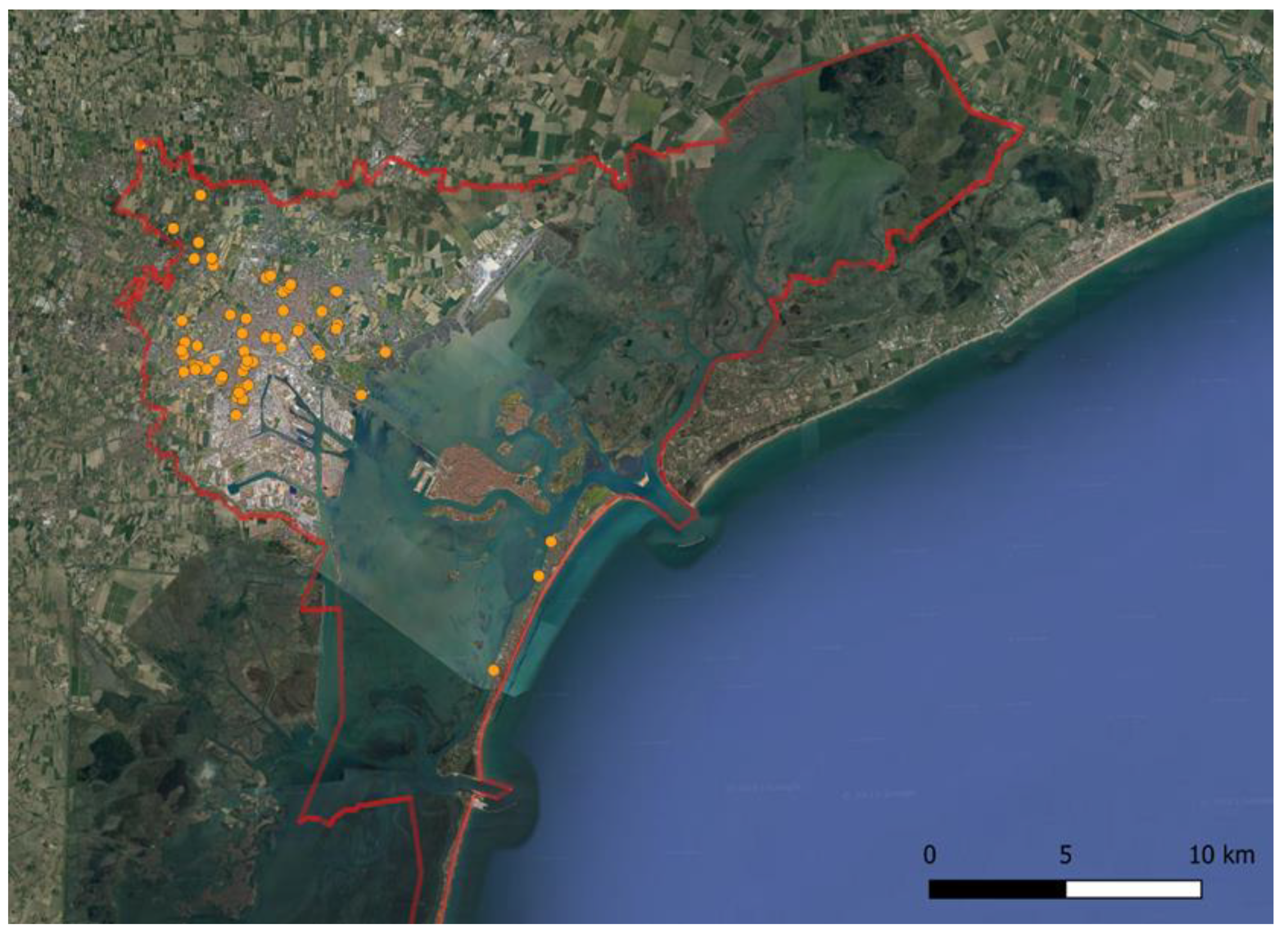

The metropolitan City of Venice, located in the north-eastern Italy, was chosen as a case study (45°26′23″N 12°19′55″E). Venice’s unique history, artistic heritage, and urban landscape led to its designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The City of Venice has approximately 260,000 inhabitants, unevenly distributed across an area of 415.9 km² (including the lagoon area).

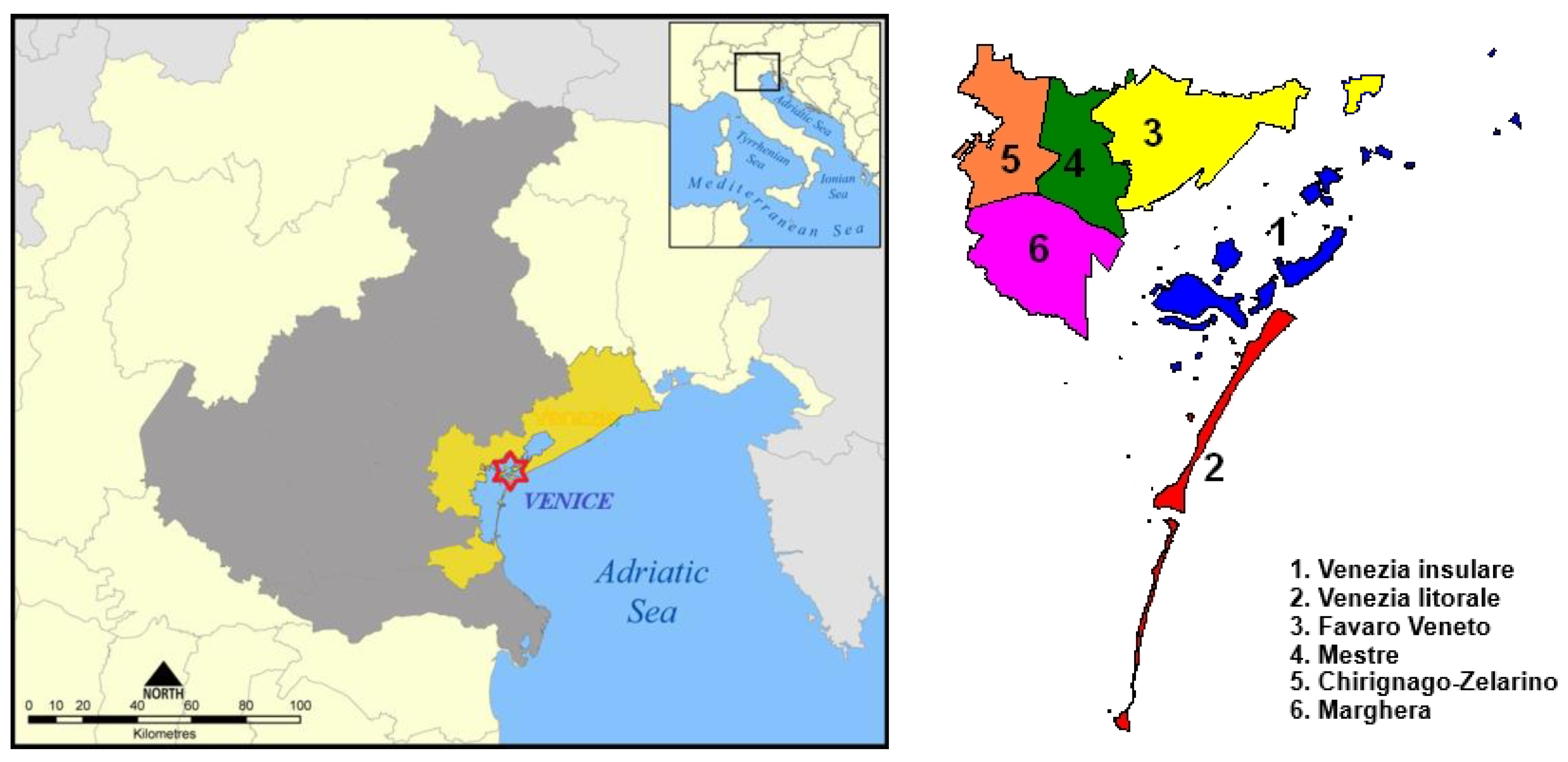

The City of Venice is divided into six municipalities, established to represent local communities, address their needs, and foster development across the metropolitan area. The six municipalities are: 1. Venezia insulare, 2. Venezia litorale, 3. Favaro Veneto, 4. Mestre, 5, Chirignago-Zelarino, 6. Marghera (

Figure 2). This subdivision also plays a role in organising the work required for the management of green areas. This territorial division was used for the various comparisons useful analysing weather-related tree falls.

Beyond the six municipalities, a separate category designated as ’0’ has been established for school grounds, which are managed independently.

The study was conducted over a four-year period from 2019 to 2022. During this time, all tree falls resulting from extreme weather events were documented. For each event, relevant meteorological data along with dendrometric and taxonomic information of the affected trees were collected. Data collection was conducted in partnership with Consorzio Zorzetto, a social consortium operating in various sectors, including public green space management. This consortium coordinates multiple cooperatives responsible for maintaining green areas across the City of Venice.

Weather data were obtained from the database available on the website of ARPAV (Agenzia Regionale per la Prevenzione e protezione Ambientale del Veneto), the regional agency for environmental protection and prevention in Veneto, which collects weather data from the network of stations distributed throughout the territory. Specifically, in the City of Venice there are two weather stations located one in mainland and one in Venezia insulare. The following meteorological parameters were collected:

Rainfall: recorded on the day of tree failure and the preceding four days,

Average wind speed and Wind direction: recorded on the day of tree failure,

Maximum gust speed: recorded on the day of tree failure and the two preceding days.

This comprehensive set of weather data allowed for a detailed analysis of the meteorological conditions associated with tree failures.

Several weather data were also collected for the days preceding each tree failure to assess any persistent effects over time. The study examined 106 weather events in total. Data on fallen trees were obtained from the management software GreenSpaces (R3GIS, Italy), an integrated and geo-referenced platform used by Consorzio Zorzetto.

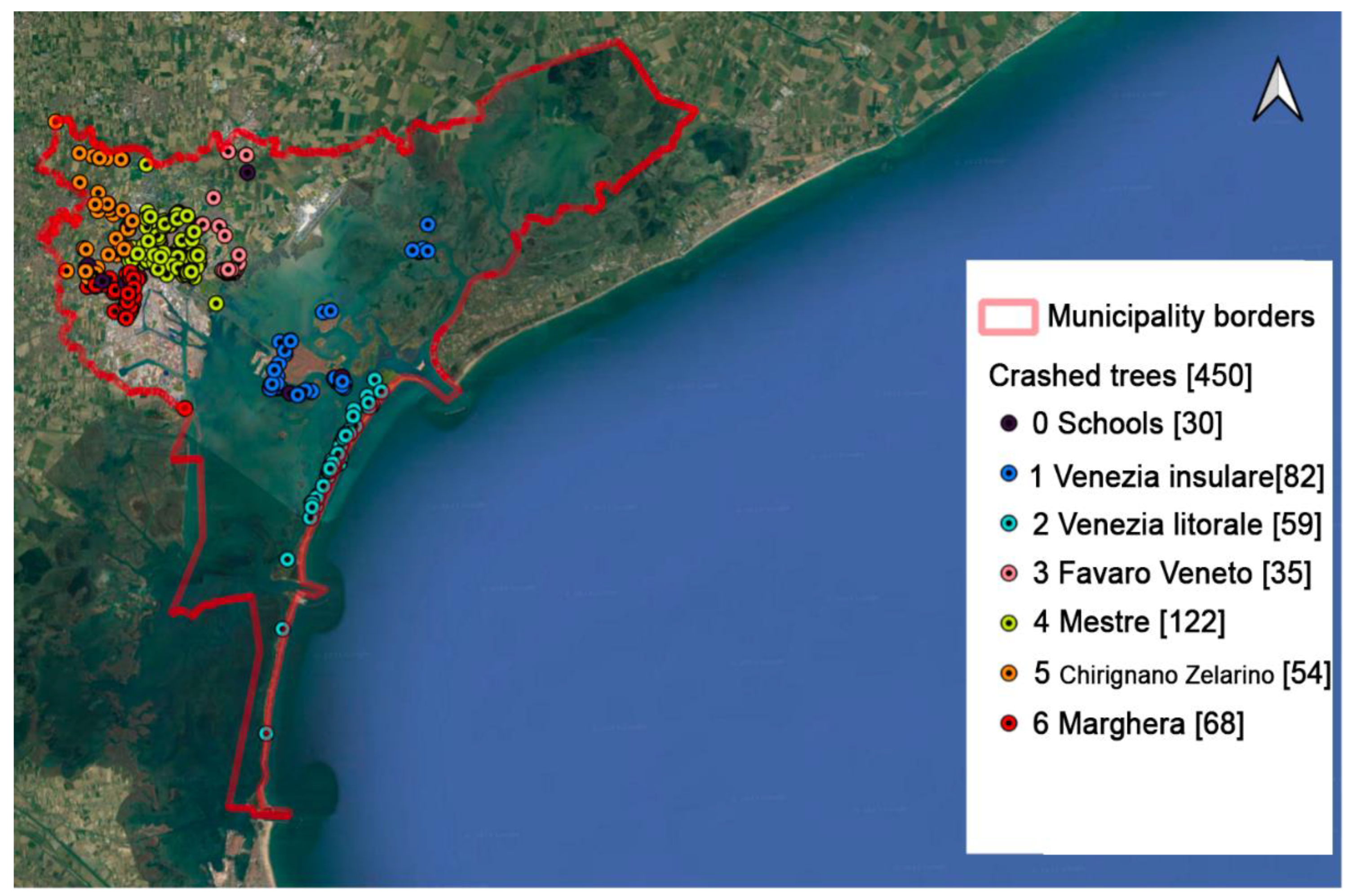

Over the four-year study period, 450 fallen trees were recorded and analyzed (

Figure 3). This dataset includes all trees that either broke or were completely uprooted during extreme weather events within the timeframe. It’s important to note that trees fallen in private areas were unfortunately excluded from this study, as they could not be accounted for by the tree data collection survey. For each tree in the dataset, the following information was collected based on the GreenSpaces database:

Tree ID

zone number (from 0 to 6, derives from internal subdivision of the territory)

location code and location name

gender, species and variety

growth site

physiological phase (as classified by Raimbault and Tanguy [

29])

date of felling

height class (m) and diameter at breast height DBH (cm)

social position (e.g., in groups, isolated, or as street trees)

coordinates

A significant portion of the data analysis focused on evaluating the distribution of tree failures across various factors. The primary factor considered was time, examining the distribution of failures over the four-year study period. This analysis helped identify the seasons and the months when tree failures were most prevalent.

Subsequently, the study examined the relationship between tree failures and weather conditions, particularly wind gust intensity and cumulative rainfall. For wind intensity, four classes were established (0-5, 5-10, 10-15, >15 m/s). Weather events were categorized according to these intensity classes, and the number of fallen trees was recorded for each event.

To enable meaningful comparisons, the average number of fallen trees per event was calculated for each intensity class. This was done by dividing the total number of fallen trees in each class by the number of events in that class. This approach was crucial for accurately assessing the relationship between wind gust intensity and tree failure rates.

The same work was carried out with cumulative rainfall, for which four classes were created (0-20, 20-40, 40-60, >60 mm).

Weather events were categorized into six classes, each with a 5°C temperature range, to assess the potential influence of temperature on tree failures.

The distribution of tree failures was evaluated across municipalities to identify the most affected areas. This was done by calculating the number of failures per hectare, obtained by dividing the number of failures in each municipality by its surface area.

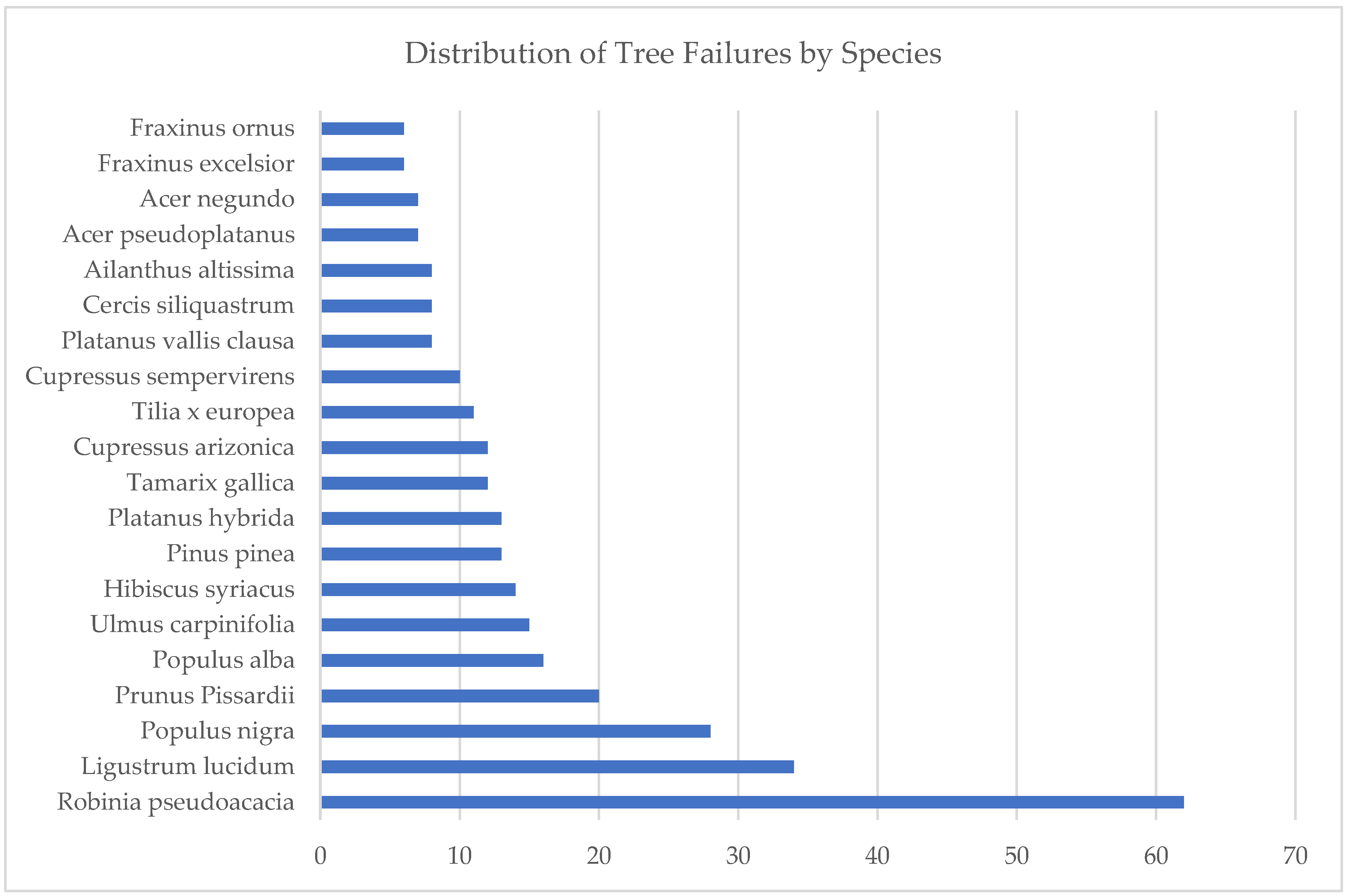

Species-specific vulnerability was analyzed by examining the distribution of failures among different tree species.

To understand which areas of the City of Venice are most susceptible to tree failures, the distribution was assessed according to growth site and social position. This analysis aimed to identify the most suitable areas for planting specific tree species. An additional analysis evaluated the distribution of tree failures according to physiological stage, with the goal of defining the optimal structure for urban tree populations. These analyses collectively provide insights into the spatial, species-specific, and age-related patterns of tree failures, informing future urban forestry management strategies.

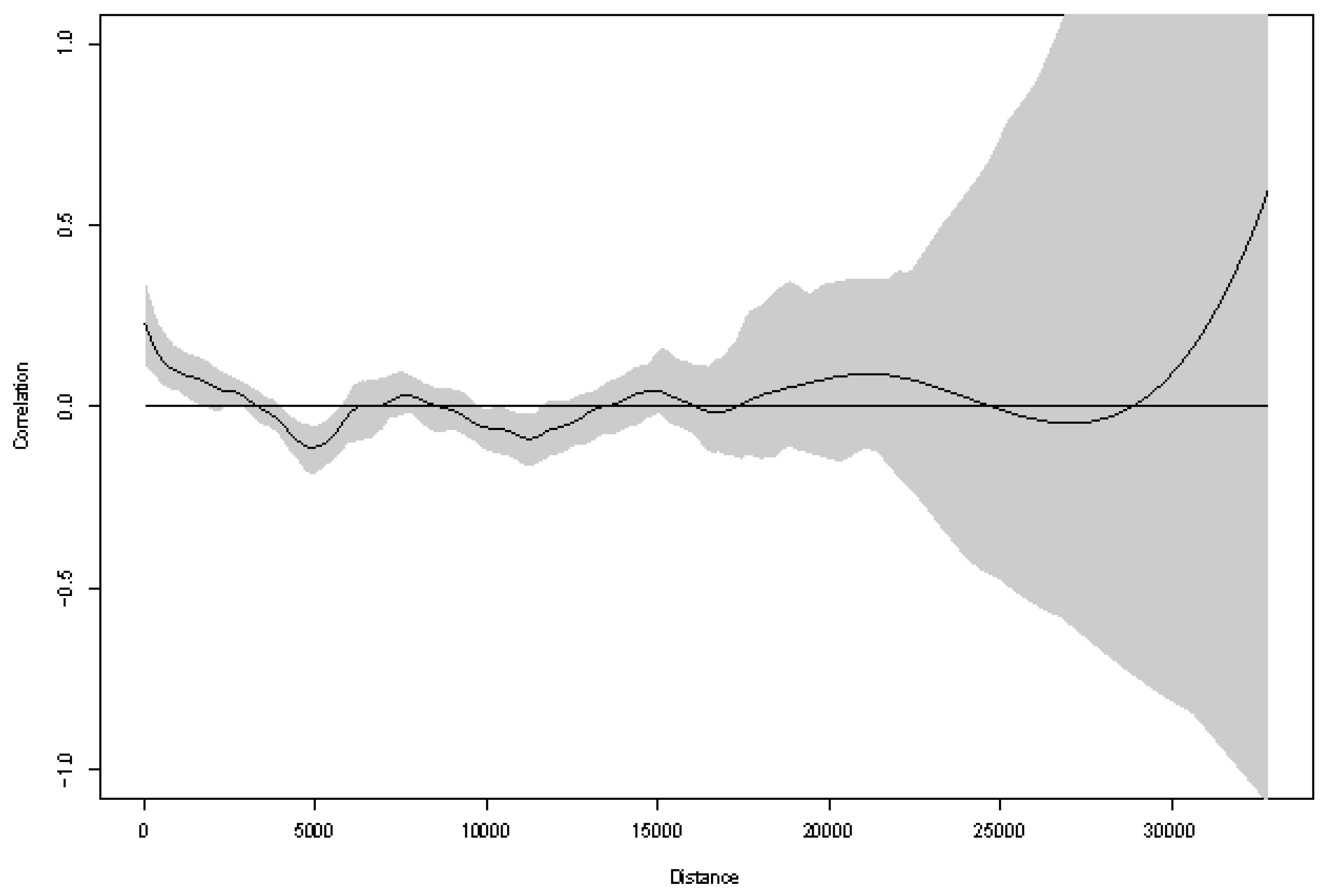

The next step involved analyzing the spatial autocorrelation among fallen trees. This analysis required both geographical data and a spatial weights matrix, which was constructed using the X and Y coordinates extracted from the database of fallen trees. The analysis was conducted using R version 4.1.2 [

30], incorporating the date of tree failures as the variable of interest in conjunction with the created matrix.

This spatial autocorrelation analysis aimed to identify any significant patterns or clusters in the distribution of tree failures across the study area, potentially revealing localized risk factors or environmental conditions contributing to tree instability. The matrix of spatial weights was produced using the

knearneigh() function of the “spdep” package [

31]. In addition, the

knn2nb() function was used to perform Moran’s I test. The spatial autocorrelation analysis was performed with the function

moran.test() considering the date of the events.

3. Results

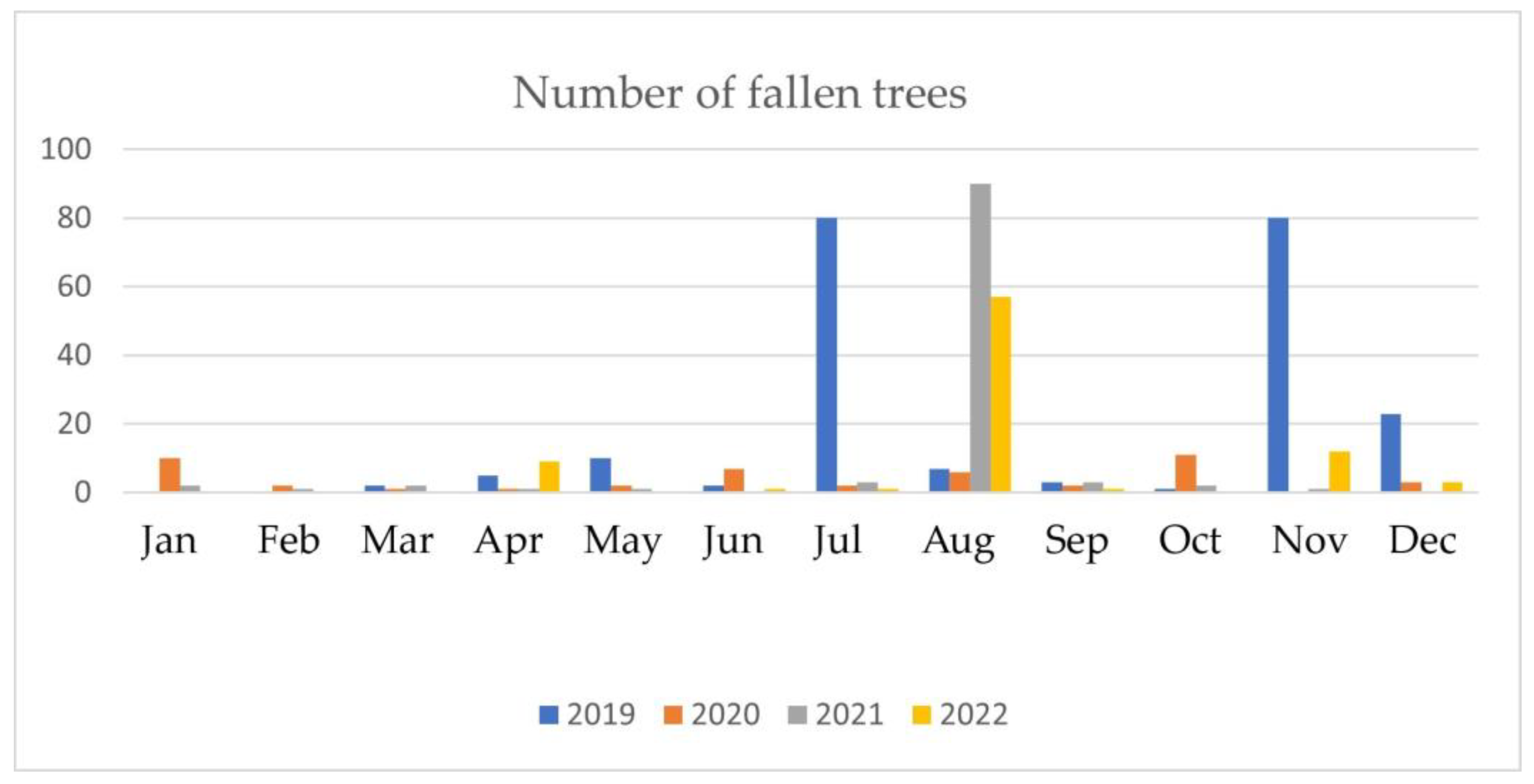

The evaluation of the distribution of tree failures during the four years under review provides the results visible in

Figure 4. As we can observe, the majority of the falls occurred during the summer months, particularly July and August, with the only exception of an abnormal extreme weather event that occurred in November 2019. The most significant event occurred on the night between August 16 and 17, 2021, when 83 trees were felled. Although the precipitation in those days had been relatively low (34 mm), high wind gusts were recorded with a peak of 26.8 m/s, a value close to that of a Category 12 hurricane on the Beaufort Wind Scale (speed of 32.5 m/s). The event on the night of November 12, 2019, occurred during a period of intense precipitation (more than 150 mm in a few days) but also with a maximum gust of 22.9 m/s, which was also the peak value for the year.

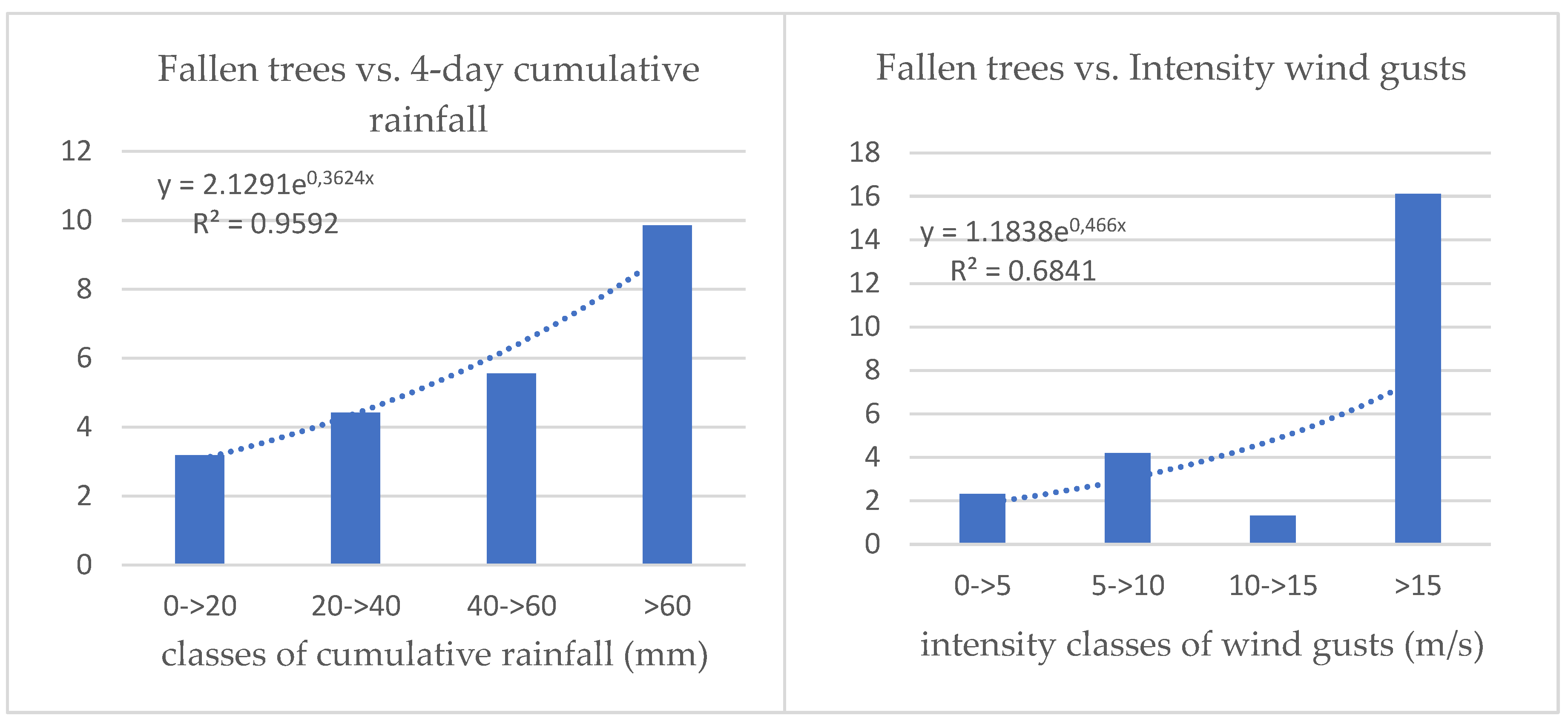

Moving on to consider the distribution of the tree failures in relation to the environmental factors that characterised the weather events considered, it is easy to observe how the average number of fallen plants per event increases as the intensity of the wind gusts and the intensity of cumulative rainfall increase (

Figure 5). This observation, despite being empirically logical, is validated by the linear regressions performed in both graphs and expressed with exponential functions, whose R

2 values of 0.6841 and 0.9592, respectively, indicate good representativeness.

Table 1 presents the distribution of fallen trees across municipalities affected by the storm. For each municipality, it shows the total number of fallen trees and the density of fallen trees per square kilometer. The density was calculated by dividing the total number of fallen trees in each municipality by its respective area. The municipalities most affected were Venezia insulare, Venezia litorale and Mestre.

Figure 6 illustrates the distribution of tree failures among different species following the storm event. Out of 74 recorded species, this graph focuses on the 20 most frequently affected. The data provides insight into which tree species were most susceptible to falling or damage during the severe weather conditions, helping to inform future urban forestry and risk management strategies.

No significant trends were observed in the distribution of trees related to their social location, growth site conditions (e.g., permeable or impermeable pavement, grassed ground, or containers), or physiological stages.

The spatial autocorrelation test performed among the fallen trees shows that they are not distributed in random order (with k=1; Moran’s I= 0.35349; p<0.001). There is a clear positive spatial autocorrelation in tree fall dates within approximately 1,500 meters, as shown in

Figure 7. In contrast, a negative autocorrelation is observed at around 5,000 meters.

4. Discussion

Multiple factors contribute to the hazards associated with tree collapse. These include senescence, imbalance between aerial and underground systems, physical damage to roots and trunks, and infestation by insects and fungi [

32]. Collectively, these factors can lead to structural failure in trees. The risk of tree fall may further increase when combined with adverse weather conditions [

33].

The prevalence of severe thunderstorms in the area of the City of Venice during summer months can be attributed to the presence of warm, humid air. This atmospheric condition triggers strong vertical air movements, leading to the formation of cumulonimbus clouds, which are characteristic of thunderstorms. In contrast, differing from the observations in Venice, a similar study conducted in Lisbon, Portugal, found that most tree falls occurred during autumn and winter [

34]. However, it should be noted that this period is precisely characterized by increased activity of Atlantic disturbances, which bring storms, strong winds, and heavy rainfall to the Iberian Peninsula [

35].

A study conducted in São Paulo, Brazil [

36] revealed that tree fall is significantly influenced by climatic factors, particularly precipitation, wind gusts, and temperature. In this region, tree fall is predominantly a seasonal event, occurring mainly during the wet season. The researchers found that wind gusts have a delayed effect, ranging from days to weeks, which leads to cumulative structural damage in trees. Similarly, rainfall exhibits a delayed impact of 4-16 days during wet seasons, primarily affecting soil stability. These findings suggest that climate conditions can have both immediate and long-term consequences on tree fall through two main mechanisms: accumulated structural damage to the trees themselves and alterations in soil anchorage. This research highlights the complex interplay between climate variables and urban forestry, emphasizing the need for proactive management strategies in cities with similar climatic conditions.

The municipalities most affected in terms of fallen trees per hectare were ’Venezia insulare’, ’Venezia littorale’, and ’Mestre’. The high number of fallen trees in Mestre can be attributed to its large tree stock, making it a probabilistic issue. For the two Venice municipalities, the high number of fallen trees can be explained by their exposure to strong wind gusts from the northeast and southeast. In fact, in Venice the predominant winds are the Bora, a cold and dry wind blowing from the northeast, typically more frequent during autumn and winter, and the Scirocco, a warm and humid wind coming from the southeast, more common in spring and summer [

37]. Trees along the littoral in these areas lacked protection against these wind directions.

The spatial autocorrelation test results reveal a positive autocorrelation in the graph segment from 0 to approximately 1,500 meters (

Figure 7). This finding indicates that during an extreme weather event, trees exhibit a higher likelihood of falling in close proximity to one another within a 1,500-meter radius. For instance, examining the extreme event of August 17, 2021, which resulted in the fall of 83 trees in a single day, we can observe—using the map in

Figure 8—that the fallen trees are predominantly concentrated in the municipalities of Mestre and Marghera. They tend to cluster in groups within a radius of approximately 1 km, with the sole exception being three trees that fell in the Venezia Litoranea municipality.

The evaluation of the distribution of failure in relation to species established that the five most affected species were:

Robinia pseudoacacia, Populus alba, Populus nigra, Ligustrum lucidum, and

Prunus cersasifera var. Pissardii (

Figure 6). Among these species, some are pioneer, which implies that they have a taproot apparatus that should guarantee their stabilization, but the data obtained do not support this principle. This may be due to the fact that trees in urban areas are subjected to numerous stresses, particularly related to soil conditions. In fact, urban soils generally derive from the accumulation of debris, landfill materials and excavation remain, which leads to the creation of soils with little organic substance and poor structure, which therefore tend to create a surface crust that causes a reduction in aeration and drainage, as well as a poor water retention capacity [

38,

39]. All these conditions are amplified by soil compaction, typical of city soils, due to the vehicular and pedestrian traffic that populates urban areas. In addition to this, there is also the numerous works to which the soil is frequently subjected in the city, for the construction of infrastructures, for the passage of underground utilities or for the construction digs.

While no statistically significant trend emerged from the data, the analysis of tree fall distribution in relation to social location revealed noteworthy patterns. The majority of affected trees were concentrated in two primary areas: roadside rows and associated groups typically found in parks. These locations are characterized by high volumes of vehicular and pedestrian traffic, raising significant safety concerns for both people and property. This finding underscores the importance of targeted maintenance and risk assessment strategies in these high-traffic urban areas to mitigate potential hazards associated with tree falls [

40].

The analysis of fallen trees in relation to their physiological phase takes into account the age of the plant at the time of its fall. It emerges that most of the fallen trees belong to the young/adult classes, which roughly correspond to the average age of the individual. This can be attributed to the fact that young trees retain elastic properties that allow them to absorb forces exerted by the winds [

41]. In contrast, mature and senescent trees are largely absent in urban areas due to the continuous environmental stresses they face, which ultimately compromise their longevity.

Despite our efforts, a comprehensive analysis of the propensity to failure class couldn’t be completed due to significant data inconsistencies and gaps in the available information. This analysis would have yielded crucial insights for developing targeted tree management and maintenance strategies [

33]. The absence of this vital information hinders our ability to optimize urban forestry practices and implement proactive risk mitigation measures. Future efforts should prioritize improving data collection and management processes to enable more robust analyses and informed decision-making in urban tree care.

Our findings for the case study area indicate that tree felling incidents are predominantly concentrated during the summer season. To address this local issue, we recommend implementing strategic felling plans that prioritize the removal of highly vulnerable specimens, such as severely decaying trees, before the onset of summer. This proactive approach would eliminate easy targets for wind-induced falls. The strategy should be part of a comprehensive tree management program. Such a program should encompass best practices including:

Careful selection of high-quality nursery stock

Proper tree planting techniques

Appropriate maintenance of mature trees

Strict adherence to Tree Protection Zone (TPZ) guidelines [

42].

By combining targeted pre-summer felling with these long-term management practices, we can significantly enhance the resilience and safety of urban forest.

5. Conclusions

Our conclusions regarding meteorological factors are logical: as the intensity of wind gusts and cumulative rainfall increases, so does the number of tree falls. While the unpredictability of these factors makes it challenging to provide practical advice, we can focus on increasing public awareness about the risks associated with falling trees during severe weather events. This approach can help improve safety measures and preparedness in urban areas prone to such incidents.

The importance of species selection in urban environments is well-established today. Trees in these settings must be resilient to the various stresses inherent to urban ecosystems. However, selecting resistant species may not always be sufficient. The soil in urban areas often undergoes significant alterations and may have poor physical and chemical properties. These factors can compromise the intrinsic resistance of even carefully chosen tree species, potentially diminishing their ability to withstand environmental stresses.

The implications of these findings are important for urban planning and management. By strategically implementing this knowledge, we can:

Dramatically enhance the sustainability of our cities

Create more liveable urban spaces that are both beautiful and safe

Maximize the myriad benefits that urban green spaces provide, including improved air quality, reduced heat island effects, and enhanced biodiversity

Significantly mitigate the potential ecosystem disservices associated with urban trees, such as property damage or injury from falling trees.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.B.; methodology, M.B. and L.B.; validation, M.B. and L.B..; formal analysis, M.B. and L.B.; investigation, M.B.; data curation, M.B. and L.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B. and L.B.; writing—review and editing, L.B.; visualization, M.B. and L.B.; supervision, L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

“This research received no external funding”.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Thomas Campagnaro for his expert assistance with the spatial autocorrelation analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

References

- Jim, C.Y. Green-space preservation and allocation for sustainable greening of compact cities. Cities 2004, 21(4), 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibri, S.E. Data-driven smart sustainable cities of the future: An evidence synthesis approach to a comprehensive state-of-the-art literature review. Sustainable Futures 2021, 3, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches, P.; Lemes de Oliveira, F.; Celani, G. Green and compact: A spatial planning model for knowledge-based urban development in peri-urban areas. Sustainability 2021, 13(23), 13365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, S.R.; DeFries, R.; Dietz, T.; Mooney, H.A.; Polasky, S.; Reid, W.V.; Scholes, R.J. Millennium ecosystem assessment: research needs. Science 2006, 314, 257–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wei, H.; Dong, X.; Wang, X.C.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, Y. Integrating land use, ecosystem service, and human well-being: A systematic review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis. Island Press: Washington, DC, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Susca, T.; Gaffin, S.R.; Dell’Osso, G.R. Positive effects of vegetation: Urban heat island and green roofs. Environmental pollution 2011, 159, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besir, A.B.; Cuce, E. Green roofs and facades: A comprehensive review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 82, 915–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Brown, R.D. Urban heat island (UHI) intensity and magnitude estimations: A systematic literature review. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 779, 146389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudorova, N.V.; Belan, B.D. The Energy Model of Urban Heat Island. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, E.; Roth, M.; Norford, L.; Molina, L.T. Does urban vegetation enhance carbon sequestration? Landscape and urban planning 2016, 148, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, A.; Mudu, P. How can vegetation protect us from air pollution? A critical review on green spaces’ mitigation abilities for air-borne particles from a public health perspective-with implications for urban planning. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 796, 148605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrini, F.; Fini, A.; Mori, J.; Gori, A. Role of vegetation as a mitigating factor in the urban context. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Lee, D.K. Planning strategy for the reduction of runoff using urban green space. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: The challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landscape and urban planning 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Riveros, R.; Altamirano, A.; De La Barrera, F.; Rozas-Vásquez, D.; Vieli, L.; Meli, P. Linking public urban green spaces and human well-being: A systematic review. Urban forestry & urban greening 2021, 61, 127105. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Park, B.J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Ohira, T.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Effect of forest bathing on physiological and psychological responses in young Japanese male subjects. Public health 2011, 125, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, B.; Zeng, C.; Xie, S.; Li, D.; Lin, W.; Li, N.; Jiang, M.; Shiliang, L.; Chen, Q. Benefits of a three-day bamboo forest therapy session on the psychophysiology and immune system responses of male college students. International journal of environmental research and public health 2019, 16, 4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, P.; Malik, V.; Harper, R.W.; Jiménez, J.M. Air pollution, human health and the benefits of trees: A biomolecular and physiologic perspective. Arboricultural Journal 2021, 43, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatieva, M.; Stewart, G.H.; Meurk, C. Planning and design of ecological networks in urban areas. Landscape and ecological engineering 2011, 7, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, M.F.; Lepczyk, C.A.; Evans, K.L.; Goddard, M.A.; Lerman, S.B.; MacIvor, J.S.; Nilon, C.H.; Vargo, T. Biodiversity in the city: key challenges for urban green space management. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2017, 15, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanis, S.A.W.; Piontek, E.; Xu, S. Perceptions of Ecosystem Services and Disservices in Urban Greenspaces: Insights from a Shrinking City. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2025, 128675. [Google Scholar]

- Von Döhren, P.; Haase, D. Ecosystem disservices research: A review of the state of the art with a focus on cities. Ecological indicators 2015, 52, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, P.; Simpeh, E.K.; Mensah, H.; Akoto, D.A.; Weber, N. Perception of the services and disservices from urban forest and trees in the Garden City of West Africa. Trees, Forests and People 2024, 16, 100550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariñanos, P.; Casares-Porcel, M. Urban green zones and related pollen allergy: A review. Some guidelines for designing spaces with low allergy impact. Landscape and urban planning 2011, 101, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, J.R.; Escobedo, F.J.; Khachatryan, H.; Adams, D.C. Consumer demand for urban forest ecosystem services and disservices: Examining trade-offs using choice experiments and best-worst scaling. Ecosystem services 2018, 29, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiley, E.T.; Kane, B. The effects of pruning type on wind loading of Acer rubrum. Journal of Arboriculture 2006, 32, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Suchocka, M.; Swoczyna, T.; Kosno-Jończy, J.; Kalaji, H.M. Impact of heavy pruning on development and photosynthesis of Tilia cordata Mill. trees. PloS One 2021, 16, e0256465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimbault, P.; Tanguy, M. La gestion des arbres d’ornement. 1re partie: Une méthode d’analyse et de diagnostic de la partie aérienne. Revue forestière française 1993, 45, 97–117. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; URL https://www.R-project.org/.

- Bivand, R.; Altman, M.; Anselin, L.; Assunção, R.; Berke, O.; Bernat, A.; Blanchet, G. Package ‘spdep’. Spatial dependence: Weighting schemes, statistics, R package version, 1–1. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mattheck, C.; Breloer, H. The body language of trees: a handbook for failure analysis; HMSO Publications Centre: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Koeser, A.K.; Hauer, R.J.; Klein, R.W.; Miesbauer, J.W. Assessment of likelihood of failure using limited visual, basic, and advanced assessment techniques. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2017, 24, 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, F.H.; Petean, F.C.D.S.; Correia, E.L.T.; Lopes, A.M.S. A Proximity-Based Approach for the Identification of Fallen Species of Street Trees during Strong Wind Events in Lisbon. Land 2024, 13, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.; Belo-Pereira, M.; Fonseca, A.; Santos, J.A. Studies on Heavy Precipitation in Portugal: A Systematic Review. Climate 2024, 12, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locosselli, G.M.; Miyahara, A.A.L.; Cerqueira, P.; Buckeridge, M.S. Climate drivers of tree fall on the streets of São Paulo, Brazil. Trees 2021, 35, 1807–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuffo, D. Microclimate for Cultural Heritage: Measurement, Risk Assessment, Conservation, Restoration, and Maintenance of Indoor and Outdoor Monuments, 3rd ed.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Scharenbroch, B.C.; Lloyd, J.E.; Johnson-Maynard, J.L. Distinguishing urban soils with physical, chemical, and biological properties. Pedobiologia 2005, 49, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavao-Zuckerman, M.A. The nature of urban soils and their role in ecological restoration in cities. Restoration Ecology 2008, 16(4), 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, T.; Wancel, D.; Stępień, G; Smuga-Kogut, M.; Szostak, M.; Całka, B. Risk of Tree Fall on High-Traffic Roads: A Case Study of the S6 in Poland. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 4479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, J.; Stokes, A. Plant biomechanics in an ecological context. American Journal of Botany 2006, 93, 1546–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, A.R.; Koeser, A.K.; Morgenroth, J. A test of tree protection zones: Responses of Quercus virginiana Mill trees to root severance treatments. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2019, 38, 54–63. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).