Submitted:

17 June 2025

Posted:

19 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. City-Owned Street Trees in Mississauga

2.2. Dry Deposition Velocity by Tree

2.3. Satellite Estimates and Field Validation of Leaf Area Index

2.4. Ambient PM2.5 Surrounding Individual Trees

2.5. Area of Deposition

2.6. Quantifying Dry Deposition of PM2.5

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

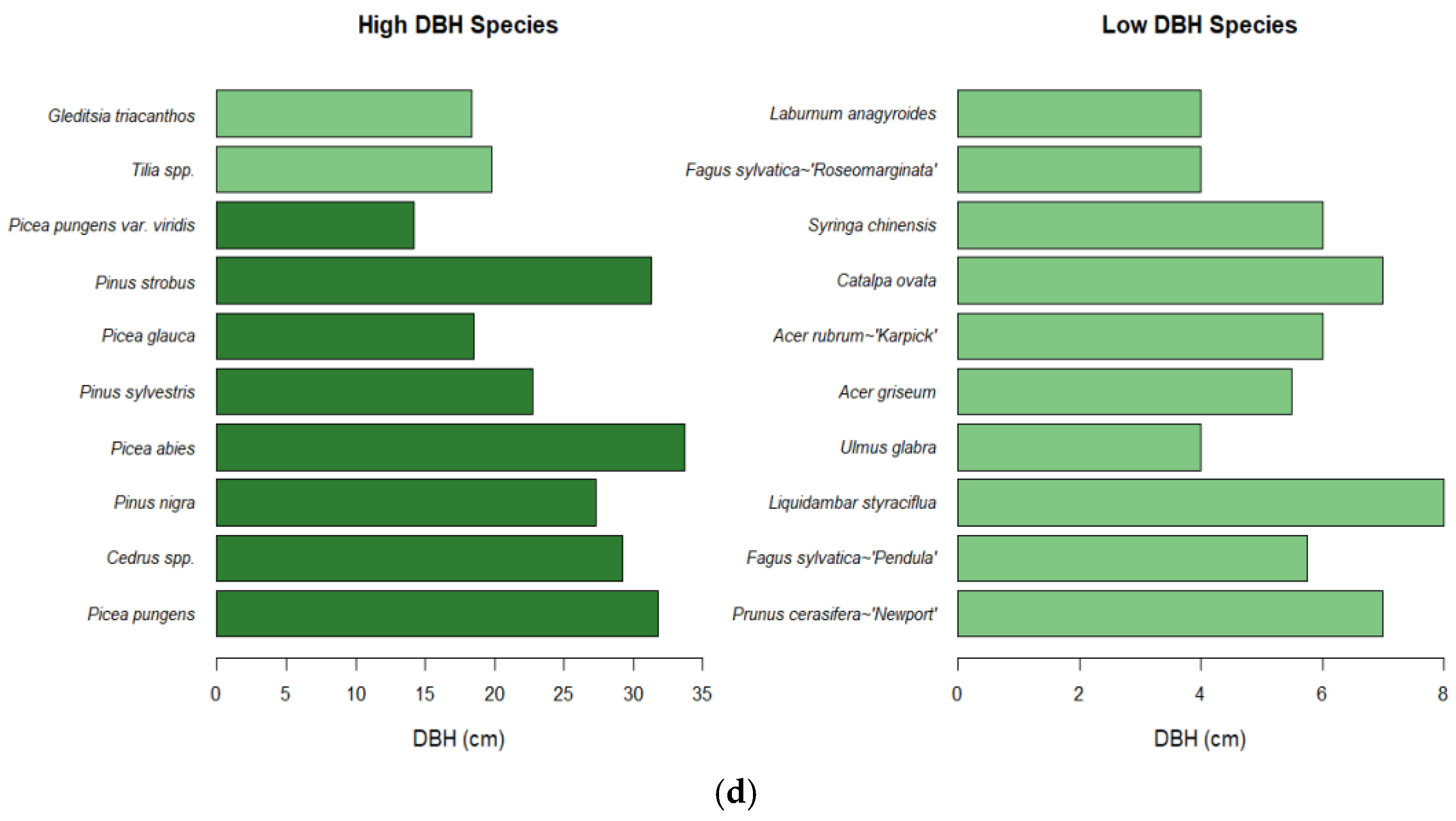

3.2. Characteristics of Species with the Lowest Deposition

3.3. Species-Specific Deposition Rates

4. Discussions

4.1. Advancing Approaches to Quantify PM2.5 Deposition by City-Owned Street Trees

4.2. Species-Specific Contribution to PM2.5 Mitigation

4.3. Refining the Theoretical Framework for Ecosystem Services by City-Owned Street Trees

4.4. Practical Implications Through a Data-Driven Framework for Species Selection to Maximize PM2.5 Removal

4.5. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PM2.5 | fine particulate matter |

Appendix A

| (a) Deciduous species | |||||||||||

| Wind Speed (m/s) | Q. petraea | A.glutinosa | F.excelsior | A.pseudo-platanus | E.globulus | F.nitida | A. campestre | S. intermedia | P. trichocarpa*deltoide | ||

| 1 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | ||||||||

| 2 | |||||||||||

| 3 | 0.831 | 0.125 | 0.178 | 0.042 | 0.018 | 0.041 | 0.08 | 0.39 | 0.12 | ||

| 4 | |||||||||||

| 5 | |||||||||||

| 6 | 1.757 | 0.173 | 0.383 | 0.197 | 0.029 | 0.098 | |||||

| 7 | |||||||||||

| 8 | 0.46 | 1.82 | 1.05 | ||||||||

| 9 | 3.134 | 0.798 | 0.725 | 0.344 | 0.082 | 0.234 | |||||

| 10 | 0.57 | 2.11 | 1.18 | ||||||||

| Local Wind Speed - 5 (m/s) | 1.5233 | 0.2233 | 0.3377 | 0.1438 | 0.0325 | 0.0923 | 0.2532 | 0.9684 | 0.5242 | ||

| Taxonomy Order | Fagales | Fagales | Lamiales | Sapindales | Myrtales | Fagales | Sapindales | Rosales | Malpighiales | ||

| (b) Coniferous species | |||||||||||

| Wind Speed (m/s) | P.menziesii | C. leylandii | P.nigra var. maritima | ||||||||

| 1 | 0.08 | 0.13 | |||||||||

| 3 | 1.269 | 0.76 | 1.15 | ||||||||

| 6 | 1.604 | ||||||||||

| 8 | 8.24 | 19.24 | |||||||||

| 9 | 6.04 | ||||||||||

| 10 | 12.2 | 28.05 | |||||||||

| Local Wind Speed - 5 (m/s) | 2.176 | 4.408 | 9.944 | ||||||||

| Taxonomy Order | Pinales | Pinales | Pinales | ||||||||

| Scientific Name | Amount of PM2.5 Deposited Per Species (g) | Percent of Total Deposition Per Species | Number of Trees Per Species | Percent of Total Trees | Amount of PM2.5 Deposition Per Tree (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Picea pungens | 18,329,696.25 | 65.94 | 10,248 | 5.11 | 1,788.61 |

| Pinus nigra | 3,286,017.20 | 11.82 | 5,004 | 2.5 | 656.68 |

| Picea abies | 1,498,729.79 | 5.39 | 1,535 | 0.77 | 976.37 |

| Pinus sylvestris | 598,184.67 | 2.15 | 1,389 | 0.69 | 430.66 |

| Picea glauca | 535,588.58 | 1.93 | 2,322 | 1.16 | 230.66 |

| Pinus strobus | 507,412.59 | 1.83 | 702 | 0.35 | 722.81 |

| Picea pungens | 420,318.48 | 1.51 | 2,632 | 1.31 | 159.7 |

| Tilia | 337,173.70 | 1.21 | 12,324 | 6.14 | 27.36 |

| Quercus rubra | 247,104.14 | 0.89 | 3,285 | 1.64 | 75.22 |

| Acer platanoides | 236,688.78 | 0.85 | 35,690 | 17.8 | 6.63 |

| Gleditsia triacanthos | 217,805.87 | 0.78 | 16,919 | 8.44 | 12.87 |

| Malus spp. | 162,528.17 | 0.58 | 10,194 | 5.08 | 15.94 |

| Acer saccharinum | 136,967.24 | 0.49 | 6,721 | 3.35 | 20.38 |

| Quercus alba | 96,708.94 | 0.35 | 475 | 0.24 | 203.6 |

| Thuja occidentalis | 91,621.79 | 0.33 | 2,297 | 1.15 | 39.89 |

| Quercus robur | 83,126.91 | 0.3 | 2,305 | 1.15 | 36.06 |

| Quercus macrocarpa | 52,721.08 | 0.19 | 945 | 0.47 | 55.79 |

| Pinus banksiana | 46,369.54 | 0.17 | 77 | 0.04 | 602.2 |

| Abies balsamea | 44,277.47 | 0.16 | 173 | 0.09 | 255.94 |

| Fraxinus pennsylvanica | 43,834.76 | 0.16 | 2,302 | 1.15 | 19.04 |

| Abies concolor | 38,099.93 | 0.14 | 107 | 0.05 | 356.07 |

| Acer x freemanii | 38,098.50 | 0.14 | 7,701 | 3.84 | 4.95 |

| Pinus resinosa | 32,889.82 | 0.12 | 52 | 0.03 | 632.5 |

| Ulmus pumila | 32,449.36 | 0.12 | 602 | 0.3 | 53.9 |

| Juglans nigra | 31,841.21 | 0.11 | 301 | 0.15 | 105.78 |

| Quercus palustris | 30,294.18 | 0.11 | 342 | 0.17 | 88.58 |

| Larix laricina | 26,265.33 | 0.09 | 56 | 0.03 | 469.02 |

| Picea pungens | 24,994.77 | 0.09 | 230 | 0.11 | 108.67 |

| Juniperus spp. | 23,592.92 | 0.08 | 909 | 0.45 | 25.95 |

| Acer saccharum | 23,409.34 | 0.08 | 3,140 | 1.57 | 7.46 |

| Ulmus parvifolia | 21,786.39 | 0.08 | 641 | 0.32 | 33.99 |

| Picea spp. | 21,124.67 | 0.08 | 94 | 0.05 | 224.73 |

| Prunus virginiana | 19,665.87 | 0.07 | 1,764 | 0.88 | 11.15 |

| Tsuga canadensis | 19,208.66 | 0.07 | 71 | 0.04 | 270.54 |

| Abies alba | 16,125.71 | 0.06 | 31 | 0.02 | 520.18 |

| Ulmus americana | 15,040.47 | 0.05 | 269 | 0.13 | 55.91 |

| Acer rubrum | 15,008.68 | 0.05 | 2,832 | 1.41 | 5.3 |

| Robinia pseudoacacia | 14,655.46 | 0.05 | 409 | 0.2 | 35.83 |

| Fraxinus excelsior | 14,280.96 | 0.05 | 517 | 0.26 | 27.62 |

| Tilia americana | 14,215.56 | 0.05 | 237 | 0.12 | 59.98 |

| Pyrus calleryana | 13,255.19 | 0.05 | 1,640 | 0.82 | 8.08 |

| Amelanchier spp. | 12,540.76 | 0.05 | 1,595 | 0.8 | 7.86 |

| Fraxinus americana | 12,520.53 | 0.05 | 770 | 0.38 | 16.26 |

| Cedrus spp. | 12,172.07 | 0.04 | 227 | 0.11 | 53.62 |

| Elaeagnus angustifolia | 12,142.45 | 0.04 | 1,313 | 0.65 | 9.25 |

| Pseudotsuga menziesii | 12,025.56 | 0.04 | 121 | 0.06 | 99.38 |

| Acer negundo | 10,276.75 | 0.04 | 825 | 0.41 | 12.46 |

| Acer platanoides | 9,203.41 | 0.03 | 5,109 | 2.55 | 1.8 |

| Quercus robur | 9,182.39 | 0.03 | 691 | 0.34 | 13.29 |

| Ulmus japonica | 9,111.90 | 0.03 | 2,375 | 1.18 | 3.84 |

| Syringa reticulata | 9,094.94 | 0.03 | 8,171 | 4.07 | 1.11 |

| Fraxinus spp. | 9,057.36 | 0.03 | 354 | 0.18 | 25.59 |

| Fagus grandifolia | 8,766.34 | 0.03 | 92 | 0.05 | 95.29 |

| Picea omorika | 8,474.30 | 0.03 | 91 | 0.05 | 93.12 |

| Celtis occidentalis | 8,085.00 | 0.03 | 2,052 | 1.02 | 3.94 |

| Taxus baccata | 7,982.61 | 0.03 | 201 | 0.1 | 39.71 |

| Betula papyrifera | 7,730.41 | 0.03 | 975 | 0.49 | 7.93 |

| Quercus bicolor | 7,543.18 | 0.03 | 287 | 0.14 | 26.28 |

| Catalpa speciosa | 6,725.03 | 0.02 | 285 | 0.14 | 23.6 |

| Prunus serotina | 6,500.96 | 0.02 | 114 | 0.06 | 57.03 |

| Tilia cordata | 5,856.49 | 0.02 | 2,376 | 1.18 | 2.46 |

| Carya ovata | 5,760.87 | 0.02 | 101 | 0.05 | 57.04 |

| Gleditsia triacanthos | 5,749.53 | 0.02 | 5,624 | 2.8 | 1.02 |

| Morus alba | 5,507.57 | 0.02 | 175 | 0.09 | 31.47 |

| Crataegus spp. | 5,032.34 | 0.02 | 365 | 0.18 | 13.79 |

| Morus spp. | 5,021.93 | 0.02 | 222 | 0.11 | 22.62 |

| Gleditsia triacanthos | 4,647.39 | 0.02 | 20 | 0.01 | 232.37 |

| Tilia cordata | 4,535.28 | 0.02 | 396 | 0.2 | 11.45 |

| Morus alba | 4,334.31 | 0.02 | 797 | 0.4 | 5.44 |

| Pyrus calleryana | 4,167.76 | 0.01 | 2,343 | 1.17 | 1.78 |

| Quercus velutina | 4,147.67 | 0.01 | 8 | 0 | 518.46 |

| Acer x freemanii | 4,116.27 | 0.01 | 4,101 | 2.04 | 1 |

| Juniperus virginiana | 3,836.54 | 0.01 | 56 | 0.03 | 68.51 |

| Aesculus hippocastanum | 3,535.56 | 0.01 | 499 | 0.25 | 7.09 |

| Malus domestica | 3,346.36 | 0.01 | 140 | 0.07 | 23.9 |

| Juglans cinerea | 3,340.43 | 0.01 | 20 | 0.01 | 167.02 |

| Acer campestre | 3,274.84 | 0.01 | 761 | 0.38 | 4.3 |

| Sorbus aucuparia | 3,178.79 | 0.01 | 250 | 0.12 | 12.72 |

| Ulmus spp. | 3,036.67 | 0.01 | 151 | 0.08 | 20.11 |

| Taxus cuspidata | 2,811.78 | 0.01 | 29 | 0.01 | 96.96 |

| Platanus x acerifolia | 2,766.47 | 0.01 | 718 | 0.36 | 3.85 |

| Chamaecyparis nootkatensis | 2,693.46 | 0.01 | 77 | 0.04 | 34.98 |

| Zelkova serrata | 2,679.52 | 0.01 | 167 | 0.08 | 16.05 |

| Quercus spp. | 2,500.69 | 0.01 | 61 | 0.03 | 40.99 |

| Acer rubrum | 2,442.91 | 0.01 | 2,972 | 1.48 | 0.82 |

| Prunus virginiana | 2,392.57 | 0.01 | 111 | 0.06 | 21.55 |

| Sorbus x commixta | 2,390.01 | 0.01 | 62 | 0.03 | 38.55 |

| Fagus sylvatica | 2,319.14 | 0.01 | 30 | 0.01 | 77.3 |

| Malus spp. | 2,267.17 | 0.01 | 284 | 0.14 | 7.98 |

| Prunus spp. | 2,242.82 | 0.01 | 210 | 0.1 | 10.68 |

| Fagus sylvatica | 1,891.18 | 0.01 | 21 | 0.01 | 90.06 |

| Ulmus americana | 1,881.98 | 0.01 | 45 | 0.02 | 41.82 |

| Fraxinus nigra | 1,846.73 | 0.01 | 107 | 0.05 | 17.26 |

| Tilia americana | 1,814.58 | 0.01 | 863 | 0.43 | 2.1 |

| Morus alba | 1,704.02 | 0.01 | 117 | 0.06 | 14.56 |

| Ailanthus altissima | 1,619.61 | 0.01 | 32 | 0.02 | 50.61 |

| Salix babylonica | 1,576.23 | 0.01 | 55 | 0.03 | 28.66 |

| Larix decidua | 1,565.15 | 0.01 | 8 | 0 | 195.64 |

| Acer platanoides | 1,512.53 | 0.01 | 475 | 0.24 | 3.18 |

| Malus domestica | 1,475.51 | 0.01 | 67 | 0.03 | 22.02 |

| Populus tremuloides | 1,357.07 | 0 | 135 | 0.07 | 10.05 |

| Pinus rigida | 1,201.38 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 400.46 |

| Catalpa bignonioides | 1,175.48 | 0 | 219 | 0.11 | 5.37 |

| Acer platanoides | 1,128.10 | 0 | 162 | 0.08 | 6.96 |

| Gymnocladus dioicus | 1,086.12 | 0 | 971 | 0.48 | 1.12 |

| Picea spp. | 1,082.34 | 0 | 16 | 0.01 | 67.65 |

| Juglans spp. | 1,070.46 | 0 | 21 | 0.01 | 50.97 |

| Pinus spp. | 1,070.43 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 133.8 |

| Prunus spp. | 885.09 | 0 | 52 | 0.03 | 17.02 |

| Acer ginnala | 861.38 | 0 | 484 | 0.24 | 1.78 |

| Populus deltoides | 859.63 | 0 | 26 | 0.01 | 33.06 |

| Carya cordiformis | 776.45 | 0 | 15 | 0.01 | 51.76 |

| Gleditsia triacanthos | 770.51 | 0 | 274 | 0.14 | 2.81 |

| Populus spp. | 767.95 | 0 | 83 | 0.04 | 9.25 |

| Acer platanoides | 706.59 | 0 | 1,234 | 0.62 | 0.57 |

| Cladrastis kentukea | 674.07 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 337.03 |

| Malus x hybrida | 673.1 | 0 | 389 | 0.19 | 1.73 |

| Magnolia x soulangeana | 646.3 | 0 | 126 | 0.06 | 5.13 |

| Ulmus thomasii | 634.21 | 0 | 20 | 0.01 | 31.71 |

| Metasequoia glyptostroboides | 594.51 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 74.31 |

| Robinia pseudoacacia | 585.75 | 0 | 46 | 0.02 | 12.73 |

| Juglans regia | 566.86 | 0 | 23 | 0.01 | 24.65 |

| Pinus mugo | 557.18 | 0 | 27 | 0.01 | 20.64 |

| Phellodendron amurense | 548.89 | 0 | 17 | 0.01 | 32.29 |

| Acer rubrum | 531.56 | 0 | 878 | 0.44 | 0.61 |

| Quercus montana | 521.97 | 0 | 49 | 0.02 | 10.65 |

| Prunus pensylvanica | 512.14 | 0 | 47 | 0.02 | 10.9 |

| Chamaecyparis obtusa | 511.66 | 0 | 22 | 0.01 | 23.26 |

| Populus x canadensis | 437.66 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 218.83 |

| Liriodendron tulipifera | 427.33 | 0 | 211 | 0.11 | 2.03 |

| Crataegus viridis | 424.53 | 0 | 69 | 0.03 | 6.15 |

| Acer platanoides | 414.51 | 0 | 298 | 0.15 | 1.39 |

| Fagus sylvatica | 400.92 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 50.12 |

| Malus x hybrida | 392.28 | 0 | 199 | 0.1 | 1.97 |

| Gleditsia triacanthos | 370.48 | 0 | 84 | 0.04 | 4.41 |

| Quercus robur | 367.1 | 0 | 34 | 0.02 | 10.8 |

| Ginkgo biloba | 332.02 | 0 | 789 | 0.39 | 0.42 |

| Ginkgo biloba | 326.05 | 0 | 208 | 0.1 | 1.57 |

| Sassafras albidum | 324.03 | 0 | 13 | 0.01 | 24.93 |

| Taxus canadensis | 315.52 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 315.52 |

| Sorbus americana | 313.25 | 0 | 30 | 0.01 | 10.44 |

| Syringa vulgaris | 300.88 | 0 | 305 | 0.15 | 0.99 |

| Populus grandidentata | 275.93 | 0 | 15 | 0.01 | 18.4 |

| Salix alba | 273.09 | 0 | 20 | 0.01 | 13.65 |

| Ulmus x vegeta | 254.05 | 0 | 133 | 0.07 | 1.91 |

| Aesculus carnea | 249.07 | 0 | 76 | 0.04 | 3.28 |

| Acer x freemanii | 233.96 | 0 | 223 | 0.11 | 1.05 |

| Betula alleghaniensis | 210.44 | 0 | 11 | 0.01 | 19.13 |

| Salix nigra | 210.37 | 0 | 12 | 0.01 | 17.53 |

| Fraxinus pensylvanica | 205.19 | 0 | 12 | 0.01 | 17.1 |

| Ulmus procera | 202.23 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 28.89 |

| Platanus x acerifolia | 183.92 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 20.44 |

| Rhus typhina | 178.03 | 0 | 200 | 0.1 | 0.89 |

| Acer x freemanii | 170.95 | 0 | 72 | 0.04 | 2.37 |

| Salix spp. | 165.31 | 0 | 46 | 0.02 | 3.59 |

| Populus alba | 153.13 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 19.14 |

| Carpinus caroliniana | 143.01 | 0 | 27 | 0.01 | 5.3 |

| Fagus sylvatica | 140.8 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 17.6 |

| Ulmus americana | 135.53 | 0 | 35 | 0.02 | 3.87 |

| Populus nigra | 124.86 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 15.61 |

| Acer spp. | 111.82 | 0 | 65 | 0.03 | 1.72 |

| Aesculus glabra | 103.01 | 0 | 167 | 0.08 | 0.62 |

| Fagus grandifolia | 102.82 | 0 | 33 | 0.02 | 3.12 |

| Acer rubrum | 99.45 | 0 | 26 | 0.01 | 3.83 |

| Tilia americana | 98.39 | 0 | 63 | 0.03 | 1.56 |

| Carpinus betulus | 92.99 | 0 | 107 | 0.05 | 0.87 |

| Fraxinus americana | 92.4 | 0 | 49 | 0.02 | 1.89 |

| Acer rubrum | 91.2 | 0 | 212 | 0.11 | 0.43 |

| Prunus cerasifera | 89.06 | 0 | 18 | 0.01 | 4.95 |

| Acer tataricum | 88.68 | 0 | 131 | 0.07 | 0.68 |

| Pyrus calleryana | 87.83 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 21.96 |

| Acer rubrum | 87.57 | 0 | 211 | 0.11 | 0.42 |

| Betula pendula | 82.9 | 0 | 23 | 0.01 | 3.6 |

| Salix fragilis | 80.83 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 16.17 |

| Ulmus scabra | 80.77 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 80.77 |

| Corylus colurna | 72.29 | 0 | 37 | 0.02 | 1.95 |

| Salix alba | 71.45 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 7.15 |

| Alnus glutinosa | 70.07 | 0 | 25 | 0.01 | 2.8 |

| Syringa vulgaris | 67.35 | 0 | 119 | 0.06 | 0.57 |

| Castanea dentata | 66.79 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 16.7 |

| Abies fraseri | 63.02 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 63.02 |

| Ulmus americana | 60.19 | 0 | 38 | 0.02 | 1.58 |

| Carpinus caroliniana | 59.03 | 0 | 12 | 0.01 | 4.92 |

| Acer palmatum | 57.1 | 0 | 65 | 0.03 | 0.88 |

| Salix matsudana | 56.51 | 0 | 14 | 0.01 | 4.04 |

| Ulmus americana | 53.87 | 0 | 42 | 0.02 | 1.28 |

| Acer pseudoplatanus | 53.05 | 0 | 24 | 0.01 | 2.21 |

| Zelkova serrata | 50.39 | 0 | 29 | 0.01 | 1.74 |

| Acer nigrum | 48.62 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 6.08 |

| Tilia americana | 43.12 | 0 | 29 | 0.01 | 1.49 |

| Cornus florida | 42.53 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 4.25 |

| Phellodendron amurense | 39.46 | 0 | 53 | 0.03 | 0.74 |

| Cercidiphyllum japonicum | 38.72 | 0 | 11 | 0.01 | 3.52 |

| Prunus serrulata | 32.48 | 0 | 11 | 0.01 | 2.95 |

| Acer saccharum | 32.29 | 0 | 26 | 0.01 | 1.24 |

| Fraxinus americana | 27.9 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 27.9 |

| Betula nigra | 26.51 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 2.95 |

| Salix discolor | 26.13 | 0 | 13 | 0.01 | 2.01 |

| Crataegus laevigata | 24.76 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 12.38 |

| Prunus glandulosa | 23.15 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 23.15 |

| Styphnolobium japonicum | 22.99 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 3.83 |

| Betula pendula | 22.47 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 3.75 |

| Cercis canadensis | 20.91 | 0 | 11 | 0.01 | 1.9 |

| Cotinus coggygria | 20.16 | 0 | 27 | 0.01 | 0.75 |

| Quercus imbricaria | 17.82 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 1.98 |

| Syringa patula | 17.14 | 0 | 38 | 0.02 | 0.45 |

| Quercus palustris | 16.73 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 3.35 |

| Fagus sylvatica | 15.1 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 2.52 |

| Syringa meyeri | 13.71 | 0 | 24 | 0.01 | 0.57 |

| Fraxinus americana | 12.68 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 2.11 |

| Morus rubra | 11.63 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 11.63 |

| Prunus pumila | 9.89 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 1.98 |

| Fagus sylvatica | 8.78 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2.2 |

| Populus balsamifera | 8.18 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 1.36 |

| Corylus americana | 7.84 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7.84 |

| Spiraea japonica | 7.73 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7.73 |

| Cornus racemosa | 7.61 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3.81 |

| Acer platanoides | 7.48 | 0 | 19 | 0.01 | 0.39 |

| Crataegus monogyna | 6.44 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6.44 |

| Acer saccharinum | 6.19 | 0 | 11 | 0.01 | 0.56 |

| Syringa vulgaris | 6.15 | 0 | 16 | 0.01 | 0.38 |

| Caragana arborescens | 6.08 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3.04 |

| Syringa vulgaris | 5.68 | 0 | 11 | 0.01 | 0.52 |

| Acer platanoides | 5.57 | 0 | 12 | 0.01 | 0.46 |

| Fraxinus quadrangulata | 5.07 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5.07 |

| Fraxinus americana | 5.07 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5.07 |

| Fraxinus americana | 4.3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4.3 |

| Platanus x acerifolia | 4.07 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0.45 |

| Malus x hybrida | 3.45 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1.72 |

| Acer x freemanii | 3.04 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0.51 |

| Ulmus americana | 2.82 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1.41 |

| Fagus sylvatica | 2.56 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1.28 |

| Syringa reticulata | 2.45 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0.82 |

| Prunus cerasifera | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Euonymus alatus | 1.93 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1.93 |

| Cornus sericea | 1.55 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1.55 |

| Viburnum trilobum | 1.36 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0.45 |

| Liquidambar styraciflua | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Magnolia stellata | 0.9 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.9 |

| Ulmus glabra | 0.88 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.88 |

| Acer griseum | 0.87 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.44 |

| Acer x freemanii | 0.86 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.43 |

| Catalpa bignonioides | 0.7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.7 |

| Syringa chinensis | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.49 |

| Laburnum anagyroides | 0.31 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.31 |

| City-Owned Tree Species | Matched Species | Approach for Matching (Order Match or Leaf Shape Match) |

|---|---|---|

| Ulmus 'Accolade' | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Fagus grandifolia | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Castanea dentata | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Ulmus americana | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Corylus americana | Alnus glutinosa | Order Match |

| Carpinus caroliniana | Alnus glutinosa | Order Match |

| Sorbus americana | Sorbus intermedia | Order Match |

| Phellodendron amurense | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Acer ginnala | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Malus domestica | Sorbus intermedia | Order Match |

| Malus spp. | Sorbus intermedia | Order Match |

| Acer rubrum 'Armstrong' | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Fraxinus spp. | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Pinus nigra | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Acer × freemanii | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Fraxinus americana 'Autumn Purple' | Fraxinus excelsior L. | Order Match |

| Abies balsamea | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Populus balsamifera | Alnus glutinosa | Shape Match |

| Tilia americana | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Carya cordiformis | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Fraxinus nigra | Acer campestre | Leaf Shape |

| Prunus serotina | Sorbus intermedia | Order Match |

| Robinia pseudoacacia | Populus trichocarpa × deltoides | Order Match |

| Robinia pseudoacacia 'Purple Robe' | Populus trichocarpa × deltoides | Order Match |

| Acer nigrum | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Quercus velutina | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Juglans nigra | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Salix nigra | Populus trichocarpa × deltoides | Order Match |

| Platanus × acerifolia 'Bloodgood' | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Fraxinus quadrangulata | Fraxinus excelsior L. | Order Match |

| Pyrus calleryana 'Bradford' | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Rhamnus cathartica | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Quercus macrocarpa | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Euonymus alatus | Populus trichocarpa × deltoides | Shape Match |

| Juglans cinerea | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Taxus canadensis | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Populus × canadensis | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Pyrus calleryana 'Chanticleer' | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Prunus avium | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Quercus montana | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Catalpa ovata | Fraxinus excelsior L. | Shape Match |

| Ulmus parvifolia | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Syringa × chinensis | Fraxinus excelsior L. | Shape Match |

| Prunus virginiana | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Acer platanoides 'Cleveland' | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Picea pungens | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Acer platanoides 'Columnare' | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Acer platanoides 'Columnare' | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Acer platanoides 'Columnare' | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Malus domestica | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Syringa vulgaris | Fraxinus excelsior L. | Shape Match |

| Salix alba | Populus trichocarpa × deltoides | Shape Match |

| Taxus baccata | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Zelkova serrata | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Fagus sylvatica 'Purpurea' | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Phellodendron amurense | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Salix matsudana 'Tortuosa' | Populus trichocarpa × deltoides | Shape Match |

| Populus deltoides | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Salix × fragilis | Populus trichocarpa × deltoides | Shape Match |

| Acer platanoides 'Crimson King' | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Acer platanoides 'Deborah' | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Pseudotsuga menziesii | Pseudotsuga menziesii | Order Match |

| Picea glauca 'Conica' | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Tsuga canadensis | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Juniperus virginiana | Cupressus × leylandii | Shape Match |

| Thuja occidentalis | Cupressus × leylandii | Shape Match |

| Ulmus 'Morton Stalwart' | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Ulmus 'Prospector' | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Ulmus spp. | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Acer platanoides 'Emerald Queen' | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Fraxinus americana 'Empire' | Fraxinus excelsior L. | Shape Match |

| Ulmus procera | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Crataegus laevigata | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Quercus robur | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Quercus robur 'Columnar' | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Quercus robur 'Fastigiata' | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Juglans regia | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Alnus glutinosa | Alnus glutinosa | Order Match |

| Fraxinus excelsior | Fraxinus excelsior L. | Order Match |

| Fagus sylvatica | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Betula pendula | Alnus glutinosa | Order Match |

| Carpinus betulus | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Larix decidua | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Sorbus aucuparia | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Chamaecyparis spp. | Cupressus × leylandii | Shape Match |

| Carpinus betulus 'Fastigiata' | Alnus glutinosa | Order Match |

| Prunus triloba | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Prunus serrulata | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Malus spp. | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Cornus florida | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Abies fraseri | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Acer × freemanii 'Marmo' | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Ginkgo biloba | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Ginkgo biloba | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Syringa vulgaris 'Glenleven' | Fraxinus excelsior L. | Shape Match |

| Tilia × flavescens 'Glenleven' | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Acer platanoides 'Globosum' | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Spiraea × bumalda 'Goldflame' | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Fraxinus pennsylvanica | Fraxinus excelsior L. | Order Match |

| Zelkova serrata 'Green Vase' | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Tilia cordata 'Greenspire' | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Cornus racemosa | Populus trichocarpa × deltoides | Shape Match |

| Acer platanoides 'Drummondii' | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Crataegus spp. | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Acer campestre | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Viburnum opulus | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Ulmus 'Homestead' | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Gleditsia triacanthos | Populus trichocarpa × deltoides | Shape Match |

| Aesculus hippocastanum | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Ostrya virginiana | Alnus glutinosa | Order Match |

| Syringa reticulata 'Ivory Silk' | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Pinus banksiana | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Syringa × prestoniae 'James McFarlane' | Fraxinus excelsior L. | Shape Match |

| Cercidiphyllum japonicum | Alnus glutinosa | Order Match |

| Acer palmatum | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Taxus cuspidata | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Juniperus spp. | Cupressus × leylandii | Shape Match |

| Acer platanoides 'Karpick' | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Gymnocladus dioicus | Populus trichocarpa × deltoides | Shape Match |

| Syringa meyeri | Fraxinus excelsior L. | Shape Match |

| Prunus serrulata 'Kanzan' | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Laburnum anagyroides | Fraxinus excelsior L. | Shape Match |

| Populus grandidentata | Alnus glutinosa | Order Match |

| Acer × freemanii 'Legacy' | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Tilia spp. | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Tilia cordata | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Populus nigra 'Italica' | Alnus glutinosa | Order Match |

| Platanus × acerifolia | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Acer negundo | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Fraxinus americana 'Manitou' | Fraxinus excelsior L. | Order Match |

| Acer spp. | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Metasequoia glyptostroboides | Cupressus × leylandii | Shape Match |

| Syringa 'Minuet' | Fraxinus excelsior L. | Shape Match |

| Cedrus spp. | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Pinus spp. | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Populus spp. | Alnus glutinosa | Order Match |

| Juglans spp. | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Salix spp. | Populus trichocarpa × deltoides | Shape Match |

| Syringa pubescens subsp. patula 'Miss Kim' | Fraxinus excelsior L. | Shape Match |

| Catalpa bignonioides 'Nana' | Fraxinus excelsior L. | Shape Match |

| Morus alba 'Pendula' | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Pinus mugo | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Morus spp. | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Carpinus caroliniana | Alnus glutinosa | Order Match |

| Celtis occidentalis | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Prunus cerasifera 'Newport' | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Catalpa speciosa | Fraxinus excelsior L. | Order Match |

| Acer platanoides | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Acer platanoides 'Schwedleri' | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Picea abies | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Acer truncatum × platanoides 'Norwegian Sunset' | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Quercus spp. | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Sorbus hybrida | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Aesculus glabra | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Pyrus calleryana | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Acer griseum | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Acer platanoides 'Park Royal' | Order Match | |

| Fraxinus pennsylvanica 'Patmore' | Fraxinus excelsior L. | Shape Match |

| Crataegus laevigata 'Paul's Scarlet' | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Caragana arborescens | Populus trichocarpa × deltoides | Shape Match |

| Prunus pensylvanica | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Quercus palustris | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Ulmus 'Pioneer' | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Pinus rigida | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Malus 'Profusion' | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Fagus sylvatica 'Purpurea' | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Prunus cerasifera 'Nigra' | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Prunus × cistena | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Salix discolor | Populus trichocarpa × deltoides | Shape Match |

| Fagus sylvatica 'Fastigiata' | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Fraxinus pennsylvanica | Fraxinus excelsior L. | Order Match |

| Cercis canadensis | Alnus glutinosa | Order Match |

| Acer rubrum | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Morus rubra | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Acer platanoides 'Reitenbachii' | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Quercus rubra | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Cornus sericea | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Pinus resinosa | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Malus 'Red Splendor' | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Tilia americana 'Redman' | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Tilia americana 'Redmond') | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Betula nigra | Alnus glutinosa | Order Match |

| Ulmus thomasii | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Acer platanoides 'Royal Red' | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Malus 'Royalty' | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Aesculus × carnea 'Briotii' | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Elaeagnus angustifolia | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Sassafras albidum | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Magnolia × soulangiana | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Prunus virginiana 'Schubert' | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Ulmus glabra | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Pinus sylvestris | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Acer platanoides 'Crimson King' | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Picea omorika | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Amelanchier spp. | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Robinia pseudoacacia 'Shademaster' | Populus trichocarpa × deltoides | Shape Match |

| Carya ovata | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Quercus imbricaria | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Ulmus pumila | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Abies alba | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Acer saccharinum | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Acer saccharinum 'Silver Queen' | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Gleditsia triacanthos 'Skycole' | Populus trichocarpa × deltoides | Shape Match |

| Cotinus coggygria | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Picea spp. | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Rhus typhina | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Magnolia stellata | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Acer saccharum | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Gleditsia triacanthos var. inermis 'Sunburst' | Populus trichocarpa × deltoides | Shape Match |

| Quercus shumardii | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Quercus bicolor | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Liquidambar styraciflua | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Acer pseudoplatanus | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Platanus occidentalis | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Larix laricina | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Acer tataricum | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Syringa reticulata | Fraxinus excelsior L. | Shape Match |

| Ailanthus altissima | Populus trichocarpa × deltoides | Shape Match |

| Styrax japonicus | Populus trichocarpa × deltoides | Shape Match |

| Populus tremuloides | Alnus glutinosa | Order Match |

| Fagus sylvatica 'Tricolor' | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Ulmus 'Morton Glossy' | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Liriodendron tulipifera | Acer campestre | Order Match |

| Corylus colurna | Alnus glutinosa | Order Match |

| Fagus sylvatica 'Pendula' | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Betula pendula 'Youngii' | Alnus glutinosa | Order Match |

| Chamaecyparis pisifera 'Filifera Pendula' | Cupressus × leylandii | Shape Match |

| Morus alba 'Pendula' | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Salix babylonica | Populus trichocarpa × deltoides | Shape Match |

| Fraxinus americana | Fraxinus excelsior L. | Order Match |

| Fraxinus americana 'Kleinburg' | Fraxinus excelsior L. | Order Match |

| Betula papyrifera | Alnus glutinosa | Order Match |

| Ulmus americana | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Abies concolor | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Morus alba | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Quercus alba | Quercus petraea | Order Match |

| Pinus strobus | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Populus alba | Alnus glutinosa | Order Match |

| Picea glauca | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

| Salix alba | Populus trichocarpa × deltoides | Shape Match |

| Ulmus glabra | Sorbus intermedia | Shape Match |

| Betula alleghaniensis | Alnus glutinosa | Order Match |

| Cladrastis kentukea | Pinus nigra | Order Match |

References

- Pourali, M., Townsend, C., Kross, A., Guindon, A., & Jaeger, J. A. G. (2022). Urban sprawl in Canada: Values in all 33 Census Metropolitan Areas and corresponding 469 Census Subdivisions between 1991 and 2011. Data in Brief, 41, 107941. [CrossRef]

- Chettry, V. (2023). A Critical Review of Urban Sprawl Studies. Journal of Geovisualization and Spatial Analysis, 7(2), 28. [CrossRef]

- Murray, A. T., Davis, R., Stimson, R. J., & Ferreira, L. (1998). Public Transportation Access. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 3(5), 319–328. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Lyu, J., Zeng, Y., Sun, N., Liu, C., & Yin, S. (2021). Individual effects of trichomes and leaf morphology on PM2.5 dry deposition velocity: A variable-control approach using species from the same family or genus. Environmental Pollution, 272, 116385. [CrossRef]

- Xie, C., Guo, J., Yan, L., Jiang, R., Liang, A., & Che, S. (2022). The influence of plant morphological structure characteristics on PM2.5 retention of leaves under different wind speeds. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 71, 127556. [CrossRef]

- Wathanavasin, W., Banjongjit, A., Phannajit, J., Eiam-Ong, S., & Susantitaphong, P. (2024). Association of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) exposure and chronic kidney disease outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 1048. [CrossRef]

- Fan, J., Li, S., Fan, C., Bai, Z., & Yang, K. (2016). The impact of PM2.5 on asthma emergency department visits: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 23(1), 843–850. [CrossRef]

- Maji, K. J., Dikshit, A. K., Arora, M., & Deshpande, A. (2018). Estimating premature mortality attributable to PM2.5 exposure and benefit of air pollution control policies in China for 2020. Science of The Total Environment, 612, 683–693. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, T., Querol, X., Alastuey, A., Ballester, F., & Gibbons, W. (2007). Airborne particulate matter and premature deaths in urban Europe: The new WHO guidelines and the challenge ahead as illustrated by Spain. European Journal of Epidemiology, 22(1), 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Al-Kindi, S. G., Brook, R. D., Biswal, S., & Rajagopalan, S. (2020). Environmental determinants of cardiovascular disease: Lessons learned from air pollution. Nature Reviews Cardiology, 17(10), 656–672. [CrossRef]

- Ng, C. F. S., Hashizume, M., Obase, Y., Doi, M., Tamura, K., Tomari, S., Kawano, T., Fukushima, C., Matsuse, H., Chung, Y., Kim, Y., Kunimitsu, K., Kohno, S., & Mukae, H. (2019). Associations of chemical composition and sources of PM2.5 with lung function of severe asthmatic adults in a low air pollution environment of urban Nagasaki, Japan. Environmental Pollution, 252, 599–606. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z., Wang, S., Xing, J., Chang, X., Ding, D., & Zheng, H. (2020). Regional transport in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region and its changes during 2014–2017: The impacts of meteorology and emission reduction. Science of The Total Environment, 737, 139792. [CrossRef]

- Hasheminassab, S., Daher, N., Ostro, B. D., & Sioutas, C. (2014). Long-term source apportionment of ambient fine particulate matter (PM2.5) in the Los Angeles Basin: A focus on emissions reduction from vehicular sources. Environmental Pollution, 193, 54–64. [CrossRef]

- Guttikunda, S. K., Goel, R., & Pant, P. (2014). Nature of air pollution, emission sources, and management in the Indian cities. Atmospheric Environment, 95, 501–510. [CrossRef]

- Sofia, D., Gioiella, F., Lotrecchiano, N., & Giuliano, A. (2020). Mitigation strategies for reducing air pollution. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 27(16), 19226–19235. [CrossRef]

- Jayasooriya, V. M., Ng, A. W. M., Muthukumaran, S., & Perera, B. J. C. (2017). Green infrastructure practices for improvement of urban air quality. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 21, 34–47. [CrossRef]

- Muresan, A. N., Sebastiani, A., Gaglio, M., Fano, E. A., & Manes, F. (2022). Assessment of air pollutants removal by green infrastructure and urban and peri-urban forests management for a greening plan in the Municipality of Ferrara (Po river plain, Italy). Ecological Indicators, 135, 108554. [CrossRef]

- Shen, J., Peng, Z., & Wang, Y. (2023). From GI, UGI to UAGI: Ecosystem service types and indicators of green infrastructure in response to ecological risks and human needs in global metropolitan areas. Cities, 134, 104176. [CrossRef]

- Wang, A., Wang, J., Zhang, R., & Cao, S.-J. (2024). Mitigating urban heat and air pollution considering green and transportation infrastructure. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 184, 104079. [CrossRef]

- Beckett, K. P., Freer-Smith, P. H., & Taylor, G. (2000). Particulate pollution capture by urban trees: Effect of species and windspeed. Global Change Biology, 6(8), 995–1003. [CrossRef]

- Beckett, K. P., Freer-Smith, P., & Taylor, G. (2000). Effective Tree Species for Local Airquality Management. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry, 26(1), 12–19. [CrossRef]

- Freer-Smith, P. H., Beckett, K. P., & Taylor, G. (2005). Deposition velocities to Sorbus aria, Acer campestre, Populus deltoides × trichocarpa ‘Beaupré’, Pinus nigra and × Cupressocyparis leylandii for coarse, fine and ultra-fine particles in the urban environment. Environmental Pollution, 133(1), 157–167. [CrossRef]

- Freer-Smith, P. H., El-Khatib, A. A., & Taylor, G. (2004). Capture of Particulate Pollution by Trees: A Comparison of Species Typical of Semi-Arid Areas (Ficus Nitida and Eucalyptus Globulus) with European and North American Species. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution, 155(1), 173–187. [CrossRef]

- Barwise, Y., & Kumar, P. (2020). Designing vegetation barriers for urban air pollution abatement: A practical review for appropriate plant species selection. Npj Climate and Atmospheric Science, 3(1), 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D., Yan, J., Sun, N., Sun, W., Zhang, W., Long, Y., & Yin, S. (2024). Selective capture of PM2.5 by urban trees: The role of leaf wax composition and physiological traits in air quality enhancement. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 478, 135428. [CrossRef]

- Gaglio, M., Pace, R., Muresan, A. N., Grote, R., Castaldelli, G., Calfapietra, C., & Fano, E. A. (2022). Species-specific efficiency in PM2.5 removal by urban trees: From leaf measurements to improved modeling estimates. Science of The Total Environment, 844, 157131. [CrossRef]

- Sæbø, A., Popek, R., Nawrot, B., Hanslin, H. M., Gawronska, H., & Gawronski, S. W. (2012). Plant species differences in particulate matter accumulation on leaf surfaces. Science of The Total Environment, 427–428, 347–354. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Lyu, J., Han, Y., Sun, N., Sun, W., Li, J., Liu, C., & Yin, S. (2020). Effects of the leaf functional traits of coniferous and broadleaved trees in subtropical monsoon regions on PM2.5 dry deposition velocities. Environmental Pollution, 265, 114845. [CrossRef]

- Dzierżanowski, K., Popek, R., Gawrońska, H., Sæbø, A., & Gawroński, S. W. (2011). Deposition of Particulate Matter of Different Size Fractions on Leaf Surfaces and in Waxes of Urban Forest Species. International Journal of Phytoremediation, 13(10), 1037–1046. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D., Yin, S., Zhang, X., Lyu, J., Zhang, Y., Zhu, Y., & Yan, J. (2022). A high-resolution study of PM2.5 accumulation inside leaves in leaf stomata compared with non-stomatal areas using three-dimensional X-ray microscopy. Science of The Total Environment, 852, 158543. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Liu, C., Zhang, L., Zou, R., & Zhang, Z. (2017). Variation in Tree Species Ability to Capture and Retain Airborne Fine Particulate Matter (PM2.5). Scientific Reports, 7(1), 3206. [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.-K., Song, H.-J., Jo, J.-W., Bang, S.-W., Park, B.-H., Kim, H.-H., Kim, K.-J., Jeong, N.-R., Kim, J.-H., & Kim, H.-J. (2021). Morphological and Chemical Evaluations of Leaf Surface on Particulate Matter2.5 (PM2.5) Removal in a Botanical Plant-Based Biofilter System. Plants, 10(12), Article 12. [CrossRef]

- Hirabayashi, S. (2022). I-Tree Eco Biogenic Emissions Model Descriptions.

- Wesely, M. L., & Hicks, B. B. (2000). A review of the current status of knowledge on dry deposition. Atmospheric Environment, 34(12), 2261–2282. [CrossRef]

- Pace, R., Guidolotti, G., Baldacchini, C., Pallozzi, E., Grote, R., Nowak, D. J., & Calfapietra, C. (2021). Comparing i-Tree Eco Estimates of Particulate Matter Deposition with Leaf and Canopy Measurements in an Urban Mediterranean Holm Oak Forest. Environmental Science & Technology, 55(10), 6613–6622. [CrossRef]

- Riondato, E., Pilla, F., Sarkar Basu, A., & Basu, B. (2020). Investigating the effect of trees on urban quality in Dublin by combining air monitoring with i-Tree Eco model. Sustainable Cities and Society, 61, 102356. [CrossRef]

- Roy, A., Mandal, M., Das, S., Popek, R., Rakwal, R., Agrawal, G. K., Awasthi, A., & Sarkar, A. (2024). The cellular consequences of particulate matter pollutants in plants: Safeguarding the harmonious integration of structure and function. Science of The Total Environment, 914, 169763. [CrossRef]

- Soares, A. L., Rego, F. C., McPherson, E. G., Simpson, J. R., Peper, P. J., & Xiao, Q. (2011). Benefits and costs of street trees in Lisbon, Portugal. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 10(2), 69–78. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X., Yang, X., Qi, J., Feng, C., & Liang, S. (2021). Effects of economic structural transition on PM2.5-Related Human Health Impacts in China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 298, 126793. [CrossRef]

- Rasoolzadeh, R., Mobarghaee Dinan, N., Esmaeilzadeh, H., Rashidi, Y., & Sadeghi, S. M. M. (2024). Assessment of air pollution removal by urban trees based on the i-Tree Eco Model: The case of Tehran, Iran. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 20(6), 2142–2152. [CrossRef]

- Ayturan, Z. C., Kongoli, C., & Kunt, F. (2024). Investigation of the effects of tree species on air quality using i-Tree software: A case study in California. Annals of Forest Research, 67(2), Article 2. [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D. J., Hirabayashi, S., Bodine, A., & Hoehn, R. (2013). Modeled PM2.5 removal by trees in ten U.S. cities and associated health effects. Environmental Pollution, 178, 395–402. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K., Jeon, J., Jung, H., Kim, T. K., Hong, J., Jeon, G.-S., & Kim, H. S. (2022). PM2.5 reduction capacities and their relation to morphological and physiological traits in 13 landscaping tree species. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 70, 127526. [CrossRef]

- García de Jalón, S., González del Tánago, M., & García de Jalón, D. (2019). A new approach for assessing natural patterns of flow variability and hydrological alterations: The case of the Spanish rivers. Journal of Environmental Management, 233, 200–210. [CrossRef]

- Climate Data (2024). Climate Mississauga (Ontario, Canada): Temperature, climate graph, climate table for Mississauga. Retrieved May 3, 2025, from https://en.climate-data.org/north-america/canada/ontario/mississauga-1676/.

- City of Mississauga. (2019). City-owned tree inventory. Retrieved October 30, 2023, from https://data.mississauga.ca/datasets/mississauga::city-owned-tree-inventory/about.

- Wang, R., Chen, J. M., Luo, X., Black, A., & Arain, A. (2019). Seasonality of leaf area index and photosynthetic capacity for better estimation of carbon and water fluxes in evergreen conifer forests. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 279, 107708. [CrossRef]

- Miller, P. (1768). The gardener’s dictionary (8th ed.). Printed for the author.

- Wróblewska, K., & Jeong, B. R. (2021). Effectiveness of plants and green infrastructure utilization in ambient particulate matter removal. Environmental Sciences Europe, 33(1), 110. [CrossRef]

- Janhäll, S. (2015). Review on urban vegetation and particle air pollution – Deposition and dispersion. Atmospheric Environment, 105, 130–137. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. M., & Black, T. A. (1991). Measuring leaf area index of plant canopies with branch architecture. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 57(1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., Yang, X., Heskel, M., Sun, S., & Tang, J. (2017). Seasonal variations of leaf and canopy properties tracked by ground-based NDVI imagery in a temperate forest. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 1267. [CrossRef]

- Feng, R., Zhang, Y., Yu, W., Hu, W., Wu, J., Ji, R., Wang, H., & Zhao, X. (2013). Analysis of the relationship between the spectral characteristics of maize canopy and leaf area index under drought stress. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 33(6), 301–307. [CrossRef]

- Planet. (2023). Planet Explorer dataset. Retrieved October 30, 2023, from https://www.planet.com/explorer.

- Gao, Z., Chen, Y., Zhang, Z., Duan, T., Chen, J., & Li, A. (2024). Continuous Leaf Area Index (LAI) Observation in Forests: Validation, Application, and Improvement of LAI-NOS. Forests, 15(5), Article 5. [CrossRef]

- Leblanc, S. G., & Chen, J. M. (2001). A practical scheme for correcting multiple scattering effects on optical LAI measurements. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 110(2), 125–139. [CrossRef]

- van Donkelaar, A., Hammer, M. S., Bindle, L., Brauer, M., Brook, J. R., Garay, M. J., Hsu, N. C., Kalashnikova, O. V., Kahn, R. A., Lee, C., Levy, R. C., Lyapustin, A., Sayer, A. M., & Martin, R. V. (2021). Monthly Global Estimates of Fine Particulate Matter and Their Uncertainty. Environmental Science & Technology, 55(22), 15287–15300. [CrossRef]

- Shimano, K. (1997). Analysis of the Relationship between DBH and Crown Projection Area Using a New Model. Journal of Forest Research, 2(4), 237–242. [CrossRef]

- Selmi, W., Weber, C., Rivière, E., Blond, N., Mehdi, L., & Nowak, D. (2016). Air pollution removal by trees in public green spaces in Strasbourg city, France. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 17, 192–201. [CrossRef]

- Morani, A., Nowak, D. J., Hirabayashi, S., & Calfapietra, C. (2011). How to select the best tree planting locations to enhance air pollution removal in the MillionTreesNYC initiative. Environmental Pollution, 159(5), 1040–1047. [CrossRef]

- Escobedo, F. J., & Nowak, D. J. (2009). Spatial heterogeneity and air pollution removal by an urban forest. Landscape and Urban Planning, 90(3), 102–110. [CrossRef]

- Tallis, M., Taylor, G., Sinnett, D., & Freer-Smith, P. (2011). Estimating the removal of atmospheric particulate pollution by the urban tree canopy of London, under current and future environments. Landscape and Urban Planning, 103(2), 129–138. [CrossRef]

- Baró, F., Chaparro, L., Gómez-Baggethun, E., Langemeyer, J., Nowak, D. J., & Terradas, J. (2014). Contribution of Ecosystem Services to Air Quality and Climate Change Mitigation Policies: The Case of Urban Forests in Barcelona, Spain. (2016). In Urban Forests. Apple Academic Press.

- Xing, Y., & Brimblecombe, P. (2020). Trees and parks as “the lungs of cities.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 48, 126552. [CrossRef]

- Su, T.-H., Lin, C.-S., Lu, S.-Y., Lin, J.-C., Wang, H.-H., & Liu, C.-P. (2022). Effect of air quality improvement by urban parks on mitigating PM2.5 and its associated heavy metals: A mobile-monitoring field study. Journal of Environmental Management, 323, 116283. [CrossRef]

- Tan, X., & Shibata, S. (2022). Factors influencing street tree health in constrained planting spaces: Evidence from Kyoto City, Japan. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 67, 127416. [CrossRef]

- Roman, L. A., & Eisenman, T. S. (2022). Drivers of street tree species selection: The case of London planetrees in Philadelphia. In The Politics of Street Trees. Routledge.

- Lin, X., Chamecki, M., & Yu, X. (2020). Aerodynamic and deposition effects of street trees on PM2.5 concentration: From street to neighborhood scale. Building and Environment, 185, 107291. [CrossRef]

- Roman, Lara A., Tenley M. Conway, Theodore S. Eisenman, Andrew K. Koeser, Camilo Ordóñez Barona, Dexter H. Locke, G. Darrel Jenerette, Johan Östberg, and Jess Vogt. 2021. “Beyond ‘Trees Are Good’: Disservices, Management Costs, and Tradeoffs in Urban Forestry.” Ambio 50 (3): 615–30. [CrossRef]

- Pataki, D. E., Alberti, M., Cadenasso, M. L., Felson, A. J., McDonnell, M. J., Pincetl, S., Pouyat, R. V., Setälä, H., & Whitlow, T. H. (2021). The Benefits and Limits of Urban Tree Planting for Environmental and Human Health. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 9, 603757. [CrossRef]

- de Guzman, E. B., Escobedo, F. J., & O’Leary, R. (2022). A socio-ecological approach to align tree stewardship programs with public health benefits in marginalized neighborhoods in Los Angeles, USA. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, 4. [CrossRef]

- Gregory, K., & Ajibade, I. (2024). Participatory mapping of tree equity, preferences, and environmental justice in Portland, Oregon. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 97, 128374. [CrossRef]

- Russo, A., & Cirella, G. T. (2024). Urban Ecosystem Services in a Rapidly Urbanizing World: Scaling up Nature’s Benefits from Single Trees to Thriving Urban Forests. Land, 13(6), Article 6. [CrossRef]

- Salmond, J. A., Tadaki, M., Vardoulakis, S., Arbuthnott, K., Coutts, A., Demuzere, M., Dirks, K. N., Heaviside, C., Lim, S., Macintyre, H., McInnes, R. N., & Wheeler, B. W. (2016). Health and climate-related ecosystem services provided by street trees in the urban environment. Environmental Health, 15(1), S36. [CrossRef]

- Livesley, S. J., McPherson, E. G., & Calfapietra, C. (2016). The Urban Forest and Ecosystem Services: Impacts on Urban Water, Heat, and Pollution Cycles at the Tree, Street, and City Scale. Journal of Environmental Quality, 45(1), 119–124. [CrossRef]

- Erisman, J. W., & Draaijers, G. (2003). Deposition to forests in Europe: Most important factors influencing dry deposition and models used for generalisation. Environmental Pollution, 124(3), 379–388. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., Davies, C., Veal, C., Xu, C., Zhang, X., & Yu, F. (2024). Review on the Application of Nature-Based Solutions in Urban Forest Planning and Sustainable Management. Forests, 15(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Askariyeh, M. H., Venugopal, M., Khreis, H., Birt, A., & Zietsman, J. (2020). Near-Road Traffic-Related Air Pollution: Resuspended PM2.5 from Highways and Arterials. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(8), Article 8. [CrossRef]

| Scientific Name |

Amount of PM2.5 Deposited Per Species (g) |

Percent of Total Deposition Per Species |

Number of Trees Per Species |

Percent of Total Trees |

Amount of PM2.5 Deposition Per Tree (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Picea pungens | 18,329,696 | 65.94 | 10,248 | 5.11 | 1,788 |

| Pinus nigra | 3,286,017 | 11.82 | 5,004 | 2.5 | 656 |

| Picea abies | 1,498,729 | 5.39 | 1,535 | 0.77 | 976 |

| Pinus sylvestris | 598,184 | 2.15 | 1,389 | 0.69 | 430 |

| Picea glauca | 535,588 | 1.93 | 2,322 | 1.16 | 230 |

| Pinus strobus | 507,412 | 1.83 | 702 | 0.35 | 722 |

| Picea pungens | 420,318 | 1.51 | 2,632 | 1.31 | 159 |

| Tilia | 337,173 | 1.21 | 12,324 | 6.14 | 27 |

| Quercus rubra | 247,104 | 0.89 | 3,285 | 1.64 | 75 |

| Acer platanoides | 236,688 | 0.85 | 35,690 | 17.8 | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).