1. Introduction

Urban forests are essential components of urban infrastructure. Like other infrastructure, the services provided by urban trees can be compromised by severe and extreme weather events such as ice or wind storms (Cadaval et al., 2024). While infrastructure elements like electrical utilities can be intentionally engineered to enhance their resilience to climate challenges (Stewart, 2015), urban foresters must work with the biomechanical limits of the trees they manage when preparing for severe and extreme weather. However, research indicates that proper species selection (Duryea et al., 2007a; Duryea et al., 2007b; Salisbury et al., 2024), pruning (Duryea et al., 2007b; Klein et al., 2020), and preventing construction damage (Johnson et al., 2019) are effective strategies for reducing storm-related losses.

Many of these findings are based on research conducted through observations of actual storm events. In this work, researchers typically assess urban forests in the aftermath of severe and extreme weather to determine if trees or tree parts failed under the storm conditions, considering a range of intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors. When available, pre-storm inventory data (collected by urban tree managers or the researchers themselves) can enhance sampling designs and help assess pre-storm conditions that may no longer be evident due to tree removal or site cleanup (Bloniarz et al., 2001; Bond, 2005).

Modern urban forestry is a data-driven management process that involves tracking, analyzing, and reporting tree assets, site characteristics, and work orders (Nitoslawski et al., 2019). Recognizing the potential scientific importance of this data and the disparate nature in which it currently exists, urban forestry researchers have worked to develop data standards for general inventories (Nowak et al., 2013) as well as those specifically related to the assessment of tree growth and longevity over time (Roman et al., 2020).

The earlier effort by Nowak et al. (2013) aimed to create a comprehensive standard for all inventory data, encompassing general tree metrics such as tree taxa, trunk diameter and tree height, methods for recording tree location and site variables, as well as tree maintenance activities and defects related to risk. The more recent effort by Roman et al. (2020), while focusing on data most relevant to tracking tree condition and survival over time, addressed many of the same data inputs. Nowak et al.’s (2013) work is reflected in the International Society of Arboriculture’s Best Management Practices Tree Inventories (Bond, 2013).

Data standards ensure consistent terminology, structure, and organization of datasets, as well as guidelines for how data should be stored and used (Gal and Rubinfeld, 2019). Standardization allows data to be easily interpreted and used by others (Gal and Rubinfeld, 2019), facilitates the aggregation of datasets into large-scale models, supports both longitudinal (Roman et al., 2020) and meta-analyses, ensures that key data omissions are avoided, and helps create greater research transparency (AgMIP, 2023). Standardization also facilitates meta-analyses that will support comparisons of urban tree databases across multiple regions.

Data standards can also serve as a roadmap for scientists exploring new research areas or for practitioners seeking guidance on data collection options for storm preparation and response. For many researchers and industry professionals, severe and extreme weather such as windstorms and ice storms are relatively infrequent events (Hauer et al., 1993; Hauer et al., 2011; Hauer and Schulz, 2023). As a result, when a storm strikes a nearby community, they may lack the experience needed to make quick decisions about data collection. For researchers, this can result in post-storm assessments being conducted after cleanup efforts have already removed critical observable failures, or in rushed data collection that leads to omissions, preventing important questions from being properly articulated and addressed.

Additionally, data collection efforts that lack randomized or stratified sampling may, at best, limit the ability to generalize findings to a larger urban tree population, and at worst, result in a biased understanding of tree storm damage. Such missteps can undermine the value of data and findings derived from extensive fieldwork.Beyond research, hastily-constructed data sets can hinder the recovery efforts of local governments and lead to issues when applying for disaster relief funds.

The authors have conducted numerous pre- and post-storm assessments, which has allowed them to refine their approaches and increase efficiency in data collection. Additionally, several of us recently conducted an international, systematic literature review based on post-storm assessments (Salisbury et al., 2023). Through this effort, we observed the wide range of data researchers have collected in an attempt to predict tree failure during tropical windstorms. This combination of experience and knowledge is presented here to outline best practices and data standards for pre- and post-storm assessment research in urban forestry. These standards can be used by urban forest managers in storm preparation and response efforts, as well as by researchers when planning fieldwork. Moreover, they can help facilitate mutually beneficial partnerships between managers and researchers—creating scenarios where insights can be gleaned by those working directly on recovery from adverse weather events while also benefiting the broader industry as a whole.

2. Methods

For this paper, we examine existing efforts to standardize data collection in urban forestry and past predictors from storm assessments to develop a master list of potential variables for assessing the impacts of storms on trees. The range of data options for pre- and post-storm data collection comes from three key sources. The first is a comprehensive literature review conducted by Salisbury et al. (2023). In this work, the authors performed a systematic review of tropical cyclone pre- and post-storm assessments to determine which intrinsic (tree-related) and extrinsic (environment-related) factors predicted tree failure. The review, conducted internationally, involved searching peer-reviewed literature in English, French, Japanese, Mandarin, Portuguese, and Spanish. It followed the PRISMA-ScR guidelines (Tricco et al., 2018) and utilized the search string "forest AND (hurricane OR cyclone OR typhoon)," along with translations and synonyms in six languages. The search covered peer-reviewed research and dissertations published between 1900 and 2022 across multiple databases, with additional studies identified through backward and forward chaining (Salisbury et al. 2023).

The second source, Nowak (2010), provides guidelines for the general assessments of species composition and ecosystem services, as well as standards for assessing tree defects and maintenance issues. The final source, Roman et al. (2020) outlines procedures for collecting core field data necessary for longitudinal monitoring of urban trees.

Data collection options are arranged into three categories: metadata, pre-storm data, and post-storm data. Within each category, we outline the minimum data set requirements necessary for meaningful analysis and data sharing. Additionally, we include optional metadata, response, and predictor variables that can be considered when developing predictive models for tree failure. Each variable is accompanied by a description, the type of data it represents (e.g., binomial, continuous, nominal, ordinal), the applicable values or units, and the source (Nowak, 2010; Roman et al., 2020; Salisbury et al., 2023) from which the data is derived.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sampling Design

To avoid bias, sampling activities related to the selection of trees, plots, or both should be completed before any observations are made. If a community has an existing inventory, selecting trees or plots can be a relatively straightforward remeasurement of all trees or a random sample. If the inventoried population is manageable and resources allow, a complete reassessment of all trees is ideal. When this is not practical, sampling is appropriate. Completely random sampling may not be as effective as stratified sampling because the latter can result in more representative data (Jaenson et al. 1992). Stratification can be across neighborhoods or street sections, or proportional to land uses (e.g., residential, commercial, parks). Crews should avoid ad hoc data collection data, nor should they adjust sampling to focus only on areas most impacted by the storm. Doing so reduces bias and the potential over-reporting of storm-related failures (Edberg and Berry, 1999).

Most importantly, damaged and undamaged trees should be measured. There is a tendency to focus data collection efforts solely on failed trees (Chen 2024), but this severely limits the utility of the data. Failures may be rare or represent a large portion of the tree population, but without knowing the total number of trees (damaged and undamaged), there is no context to assess the likelihood of failure. Without understanding the likelihood of failure, it is impossible to determine which factors—such as species, specific environmental conditions (e.g., wind exposure, soil conditions, associated precipitation), or other variables—increase or decrease the potential for failure. A condition may appear to be associated with a higher likelihood of failure simply because it is more commonly observed in the sample, not because it compromises the tree's structural integrity (e.g., Koeser et al., 2023). Lastly, there is tremendous value in understanding what factors are present in trees that are strong enough to resist severe weather, as these trees may represent optimal tree selection, planting, and management practices.

3.2. Metadata

Metadata plays an essential role in science and data sharing, as it provides context about the data, such as how it was collected, processed, formatted, and organized. This information ensures that datasets are easily understandable, reproducible, and usable by other researchers, facilitating collaboration and enhancing the transparency of scientific work. Well-documented metadata helps prevent misinterpretation, enables effective data integration across studies, and improves the long-term usability of data, making it a valuable resource for future research. Metadata standards such as ISO 19115 (

https://www.fgdc.gov/metadata/iso-standards) could be used to ensure documentation that meets federal requirements in the US, but we recommend several metadata elements as a minimum metadata set when working with pre-and post storm inventory data (

Table 1).

The first two metadata elements suggested for the minimum data set in

Table 1 provide information about the inventory crews who conduct field work. First, field crew identification should include details on whether volunteers, students, or professionals gathered the data. Information such as education, training, or industry credentials (especially those related to tree risk assessment) should also be included. In addition to these descriptions, an ordinal rating of experience level (novice, intermediate, expert) allows others to gauge data quality.

Most other metadata elements suggested for the minimum data set are intended to provide details about the storm (

Table 1). They include its date, type (e.g. hurricane, tornado, ice) and severity (e.g. hurricane category level, tornado EF or F level, measured wind speed, measured ice accumulation), and the source of the storm information. Weather associated with a storm, even in the same region, is often characterized differently (Landry et al., 2021) depending on the geographic focus. Furthermore, details on storm events can be difficult to obtain, and researchers may draw from a variety of sources, including local weather stations, news outlets, weather services, and national agencies—each of which may provide slightly different estimates of storm intensity. Storm data should be reported from reputable sources close to the tree population being assessed. Depending on the size of the storm, conditions may differ dramatically, even a few kilometers apart. When available, report relevant storm variables like precipitation received, average and maximum sustained wind speeds, average and maximum gust speeds, storm duration, storm surge, flooding, and average, maximum, and minimum temperatures. To provide context for researchers in other regions, average climate across the area should be reported, both annually and for the month that the storm occurred. This presents the baseline or normative conditions experienced by the tree population. In some cases it may be appropriate to include information about precipitation immediately prior to the storm event. Areas that had received high levels of precipitation which saturated the soils may experience high levels of tree blowdown even in less severe wind events (Kamimura et al., 2012).

3.3. Response Variables

The response variables collected determine the research questions that can be asked. In some cases, researchers have the opportunity to form their hypotheses first, and then gather the most appropriate data to address those questions. Other times, researchers will be working with data previously collected during routine inventories or post-storm urban or utility forestry operations (Urban Forest Strike Teams, 2024). In this latter scenario, the available data will limit the range of possible research directions. Additionally, data quality can vary. However, using existing data sources, when available, can help conserve resources and offer a snapshot of the immediate aftermath of a storm and the associated cleanup efforts.

Dead trees present a particular challenge because it is sometimes difficult or impossible to determine the cause of mortality. Large scale damage, data gaps, and delayed mortality after a storm can increase this uncertainty (Armentano et al. 1995). Depending on the timing of the post-storm assessment, crews may encounter a standing or fallen dead tree, or find only a stump or vacant planting site. While all these scenarios can be categorized as "dead," it is often impossible to attribute urban tree mortality to a specific storm with certainty, especially if there is a time gap between the pre- and post-storm assessments and the actual storm. When trees are missing, crews might consider contacting the property owner or manager to confirm whether the tree died or failed during the storm (by knocking on the door or leaving a door hanger). For example, post-storm assessment crews followed this approach to disregard missing trees that had been removed for site development prior to Hurricane Irma (Landry et al., 2021).

While a simple assessment of whether a tree survives or not is useful, data on partial branch failure can be highly valuable from a risk assessment or utility management perspective. In these cases, damage could be evaluated using a simple ordinal rating system. For example, Roman et al. (2020) include a "Crown vigor" variable, described as "a holistic assessment of overall crown health, reflecting the proportion of the crown with foliage problems and major branch loss," with five classes ranging from healthy to dead. Additionally, other existing crown assessment techniques, typically used for evaluating condition, health, or estimating ecosystem services, could be applied to document tree damage that is not an immediate source of mortality (Bond, 2012; i-Tree, 2021).

Post-storm work orders from local urban forestry programs can serve as a proxy for graduated damage assessment, particularly if they are generated as part of a systematic evaluation. Trees that suffer little to no damage will be skipped when determining the need for care after the storm, while those with more significant damage may require pruning to remove broken branches and restore crown structure. Trees with severe crown damage, trunk failure, or root failure will be scheduled for removal. This dual-purpose approach benefits both practical management and research. With this in mind, data collection crews should seek opportunities to collaborate with local urban foresters and other urban vegetation managers to generate work orders or damage reports from post-storm assessments conducted for research.

Most post-storm research focuses on tree damage and death, and the models generated from this research can help managers predict losses in urban forest value and benefits after a storm event. From an urban tree risk perspective, post-storm tree damage is a critical response that helps inform likelihood of failure, but it does not provide a complete picture. Risk also includes the likelihood of impact and consequences of failure. To gain a better understanding of the risks posed by trees in a population, researchers must conduct surveys of property owners and managers to assess the consequences of failure to targets such as structures, utilities, vehicles, and people.

3.4. Pre-Storm Inventory Data - Minimum Data Set

In addition to the metadata listed in

Table 1, the minimum pre-storm data set includes five other variables (

Table 2). The first is the date the tree was inventoried or last updated. The second is a unique identifier of each tree that allows users to combine pre- and post-storm data sets. Additionally, location information sufficient for re-assessment should be recorded—whether this is (in order of greatest to least useful) coordinates stored in a GIS, an address or unique identifier of the planting space. Species identification, according to internationally-accepted taxonomic databases like the Royal Botanical Garden, KEW's International Plant Names Index and Plants of the World Online (POWO, 2024), should also be recorded to both aid in relocation and to identify species-specific likelihood of failure. Taxon is consistently one of the most significant predictors of failure (Salisbury et al., 2024). Lastly, trunk diameter should be recorded to aid in relocation efforts, especially when groups of a single species exist in a small area. Because the height at which trunk diameter is measured varies regionally (Magarik 2021), it should be included, as should the protocol for measuring diameter when a tree consists of multiple trunks (

Table 2).

3.5. Pre-Storm Inventory Data - Optional Data

While the minimum data set described in

Section 3.4 is sufficient for creating random or stratified samples, additional pre-storm data collection can be valuable when addressing specific questions related to risk assessment and tree biomechanics (

Table 3). Some of these variables are best collected prior to a storm if they are to be included in the analysis. These include components of visual risk assessments (i.e., qualitative safety assessments of a tree and its surroundings using industry best practices), which could be biased by the hindsight that occurs during post-storm evaluations. Additionally, aspects of tree conditions, such as opacity and quality (Bond, 2012), may be affected by the storm. While many measurements are easier to take before a storm, most can still be measured or estimated afterward, as explained in

Section 3.8.

Understandably, urban forest managers may be hesitant to make tree risk and condition assessments publicly available, as residents might be alarmed to learn that a tree near them poses an elevated risk. Moreover, public risk records could lead to future litigation if a tree identified as high-risk fails before mitigation can occur. If data will be published in a paper or posted in a repository, one strategy is to remove these risk assessment ratings; alternatively, the data can be anonymized by eliminating identifying location information (e.g., addresses, coordinates, storm names). Researchers affiliated with a university should consult with their research offices or libraries to discuss specific requirements for sharing sensitive data. These offices can also assist in creating data management and sharing plans, which may be required by funding sources to demonstrate to reviewers that these issues have been thoroughly considered.

3.6. Post Storm Assessment - Minimum Data Set

Several parameters collected during the pre-storm assessment (

Table 2 and

Table 3) are also collected during the post-storm assessment (

Table 4). First, if a pre-storm assessment was conducted, use the unique identifiers of each tree to pair pre- and post-storm data collection. If a pre-storm assessment was not conducted, the post-storm data set will require unique tree identifier numbers. Similarly, location, species, and trunk diameter are necessary for both data sets in order to ensure pre- and post-storm data are appropriately matched. Lastly, the minimum post-storm data set should include a measured response related to tree damage. This could be as simple as a binary variable (1 = damage, 0 = no damage), or more detailed information could be collected, such as the location of damage (e.g., roots, trunk, crown) and the severity of failure within the tree as described in

Section 3.3.

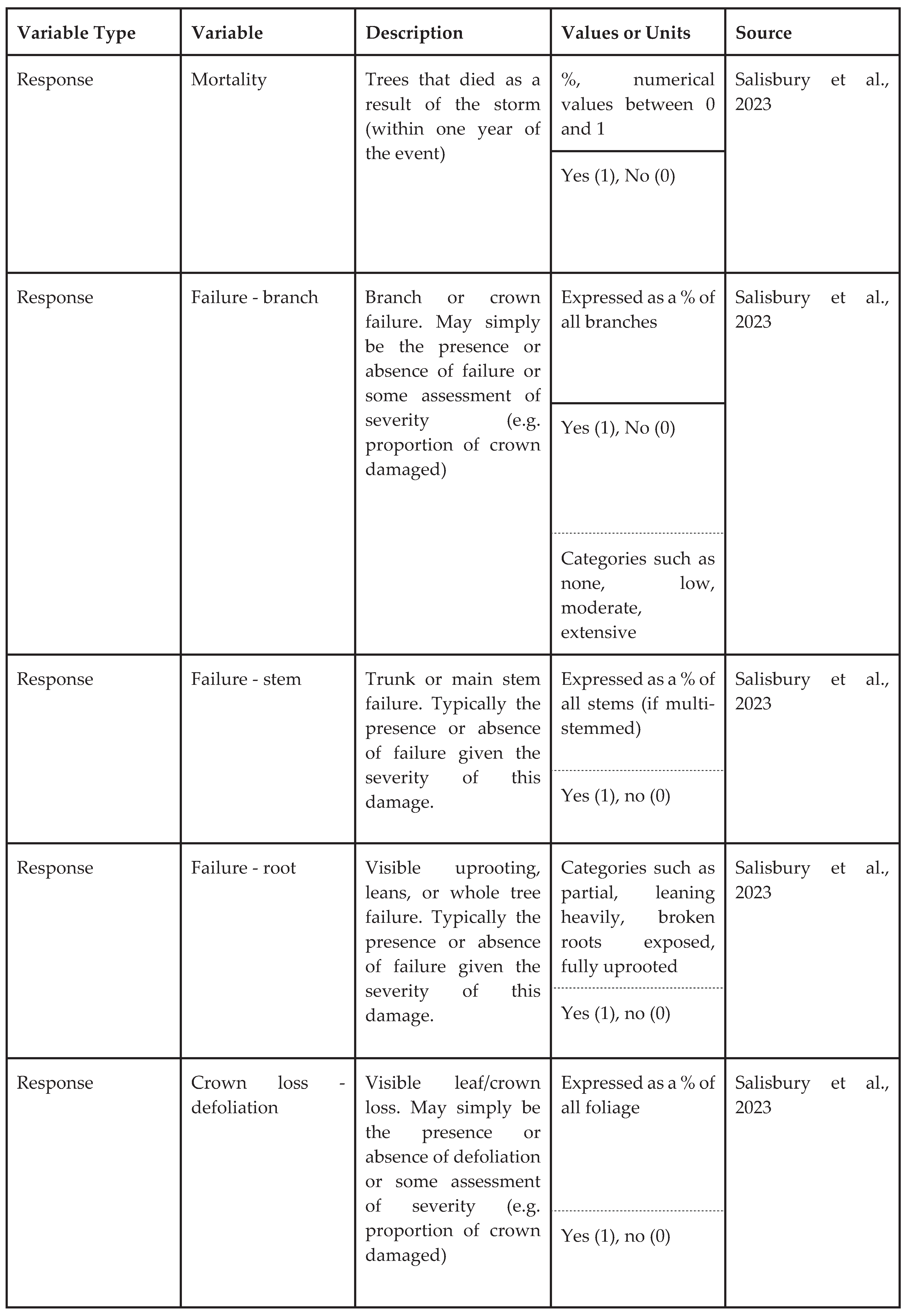

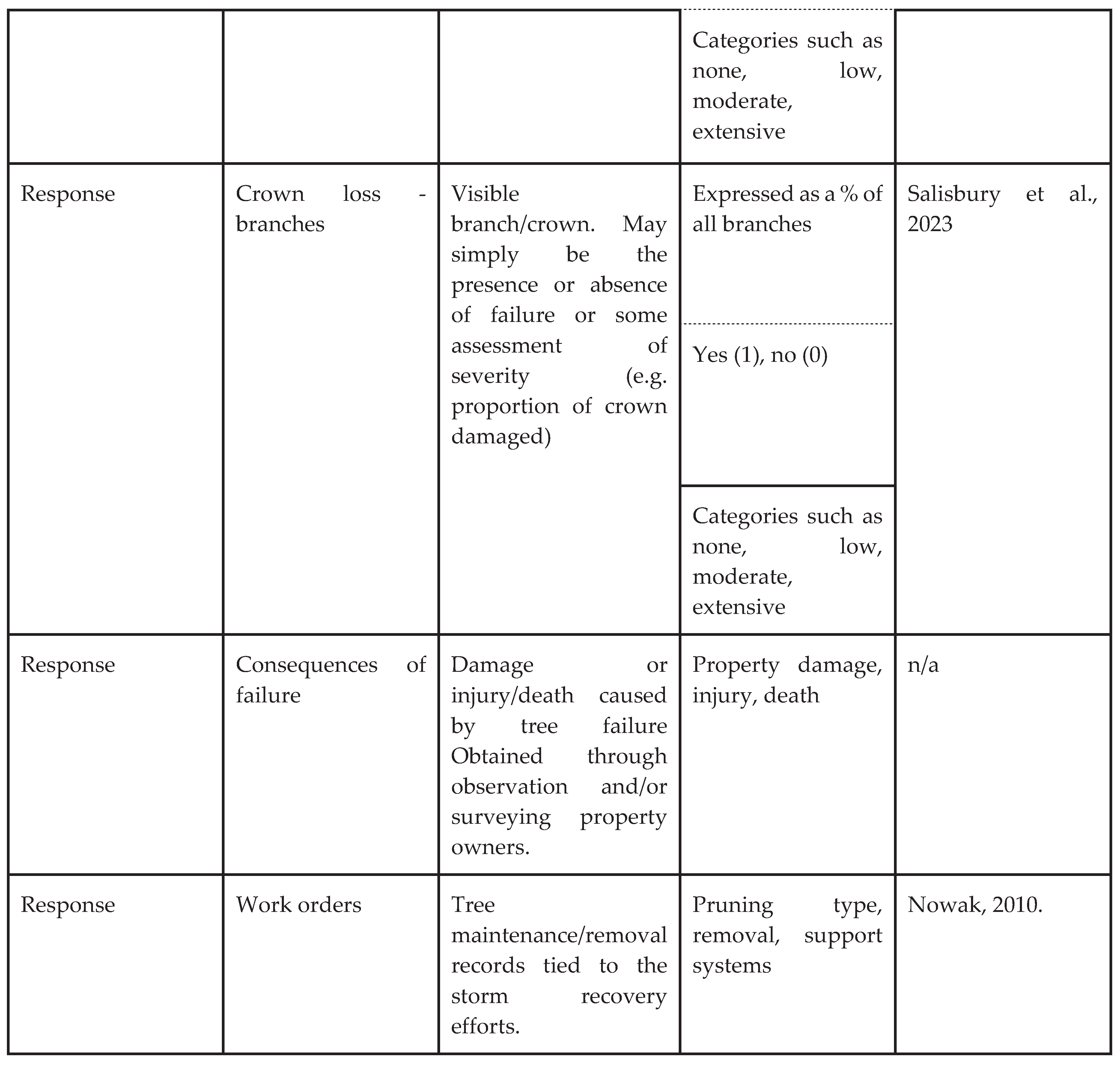

3.7. Post Storm Assessment - Optional Data Set

Optional post-storm data collection could include a wide range of response data beyond simply the presence or absence of tree damage (

Table 5). Alternatives include damage expressed as a percentage of the whole tree or the crown, ordinal rankings of damage, damage in specific tree locations (e.g., roots, trunk, crown), and tree mortality. Post-storm assessments could also evaluate property damage or injuries/deaths. Work orders from post-storm cleanup efforts can also be analyzed to gauge damage severity.

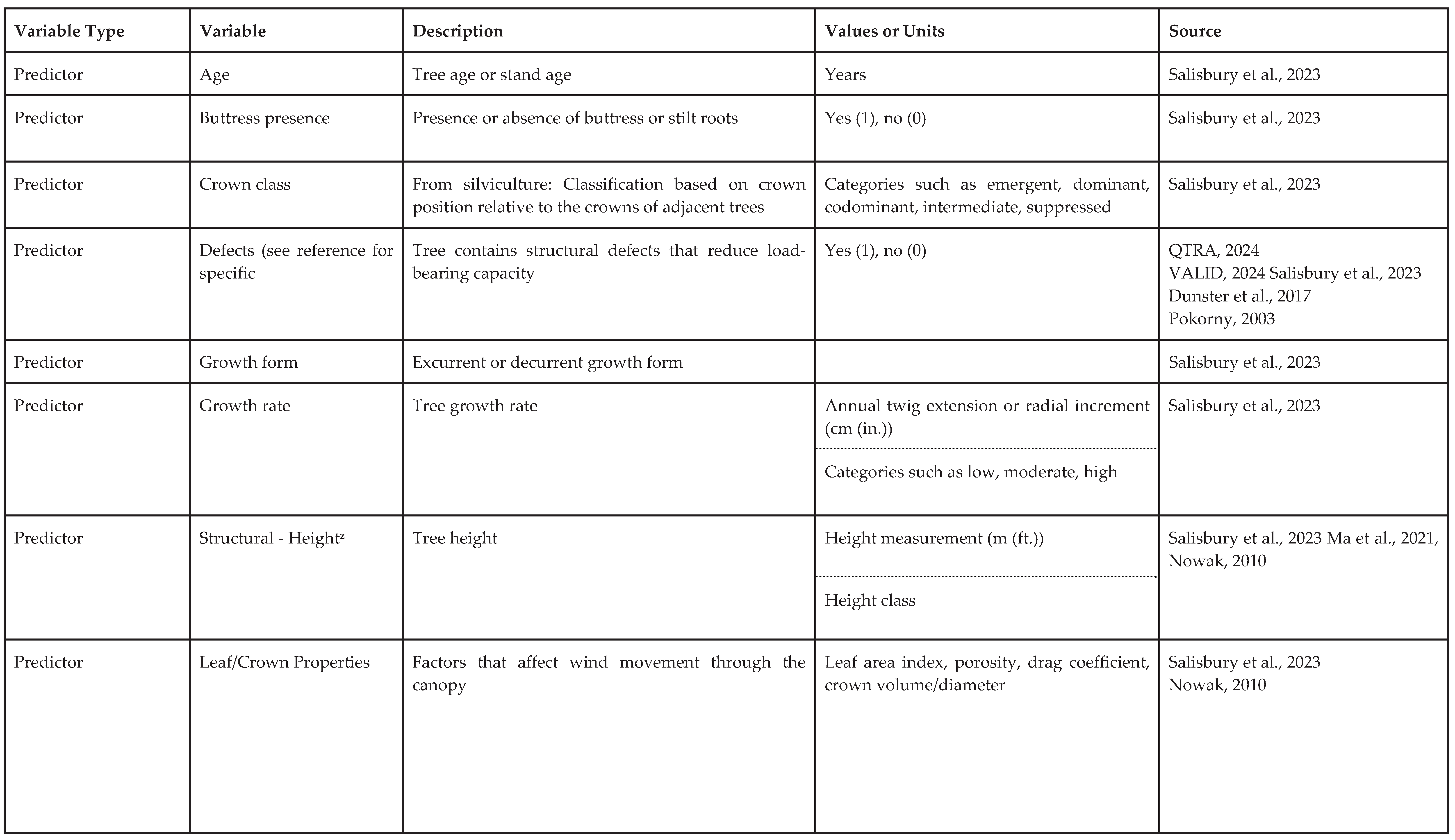

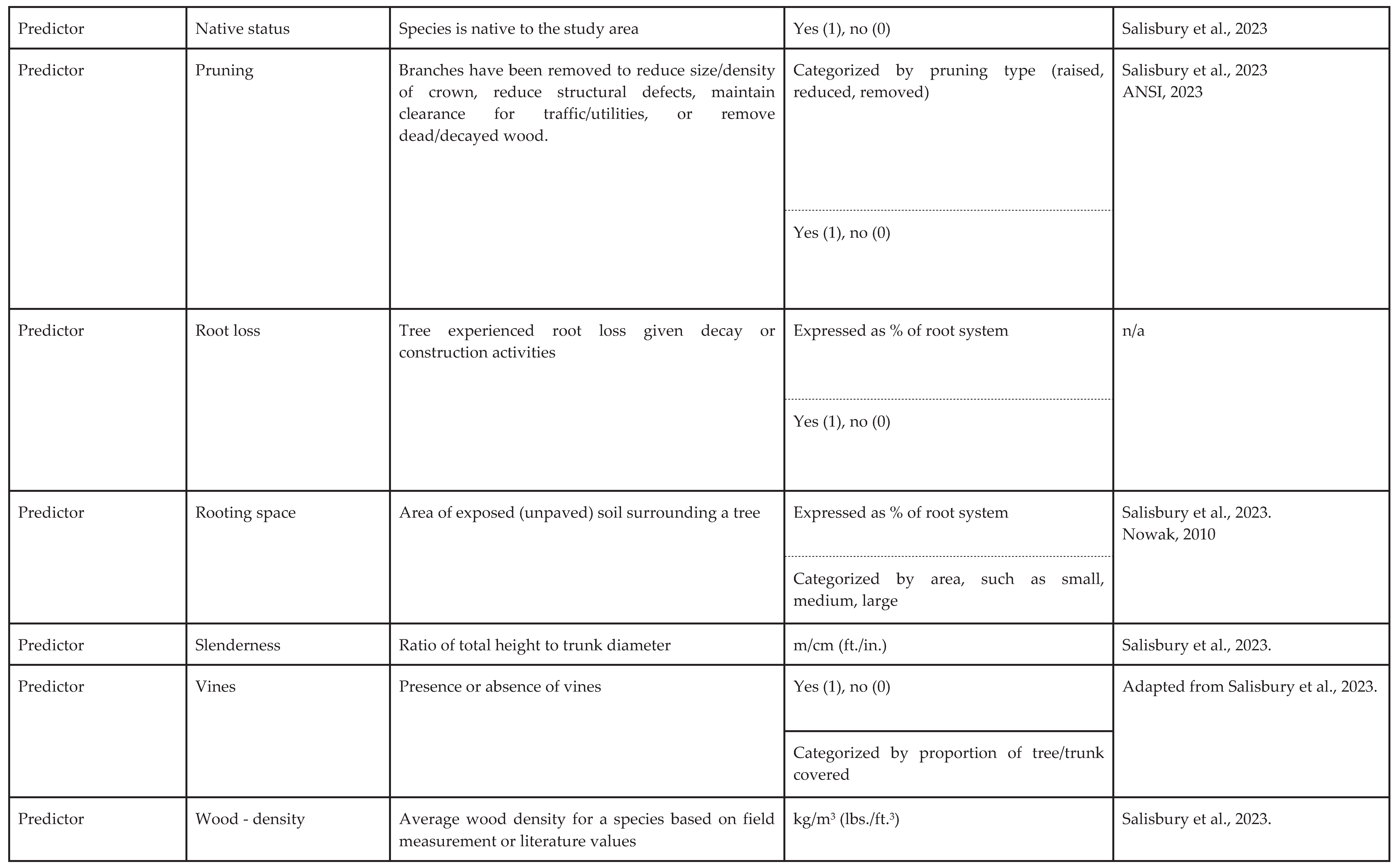

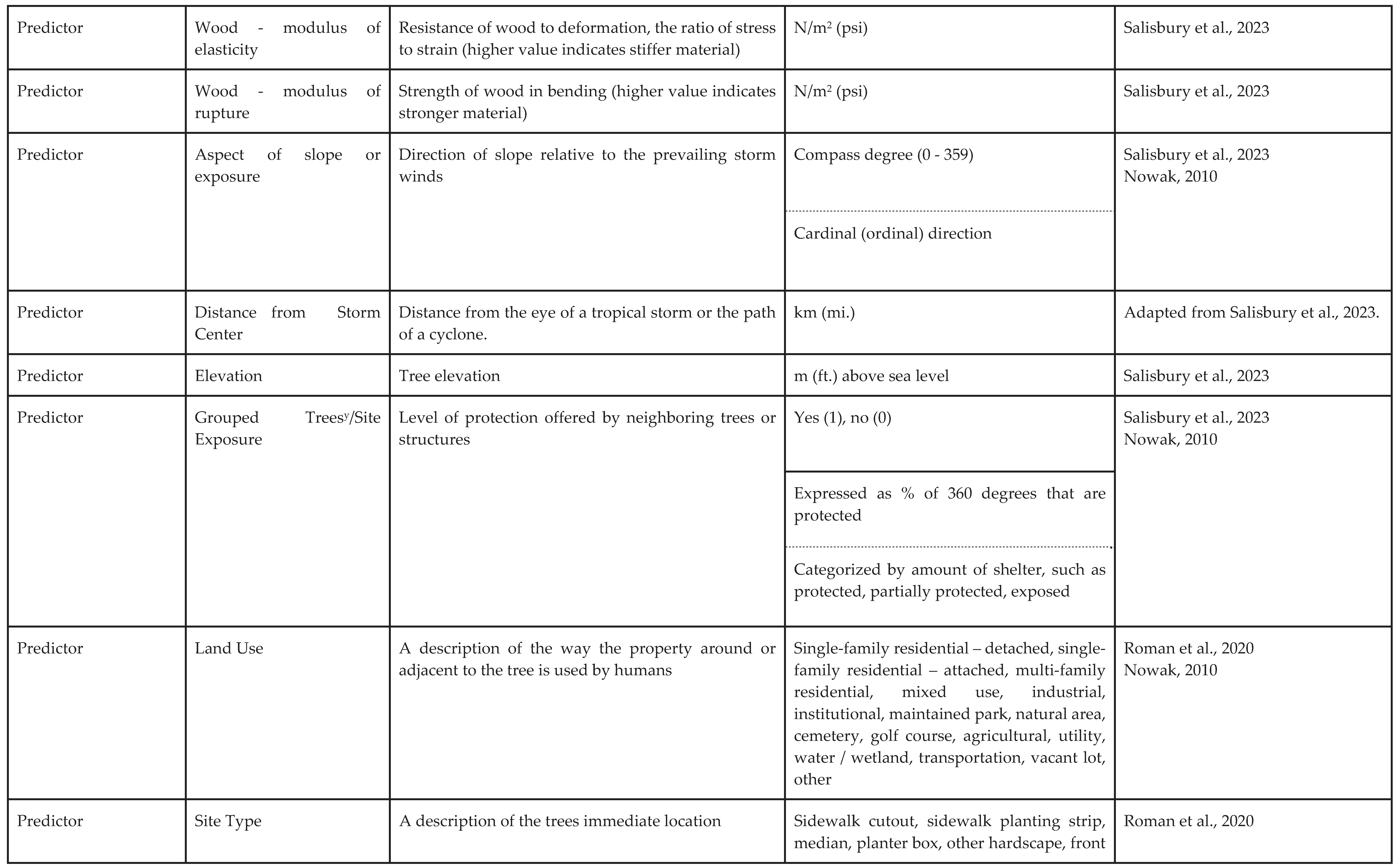

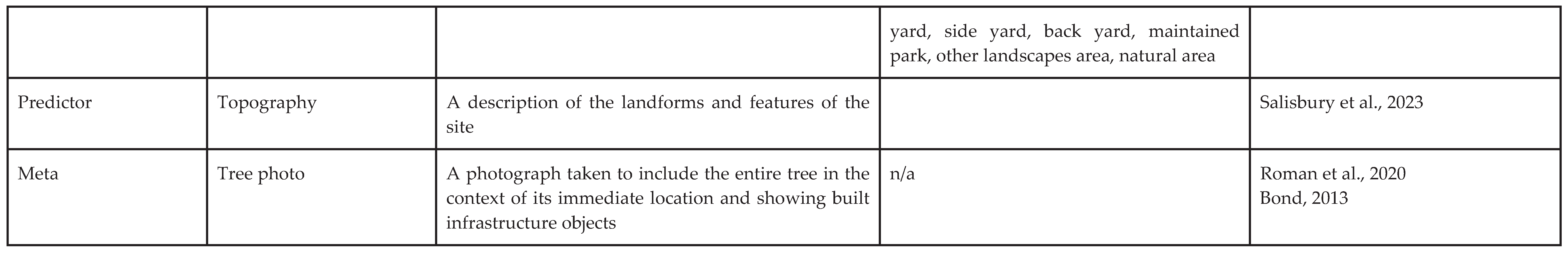

3.8. Optional Data That Can Be Collected Before or After a Storm

To study the impact of storms on trees, many optional data can be collected before or after the storm to better understand tree vulnerability and resilience (

Table 6). Tree characteristics such as age, species growth form, and species growth rate can provide insights into the developmental stage and overall health of trees (Salisbury et al., 2023). Defects such as leans or decay may indicate predispositions to failure during extreme weather events (Hickman et al., 1995; Kane, 2008; Nelson et al., 2022). Variables such as native status, wood density, and the wood’s modulus of elasticity and rupture can affect a tree's inherent strength (Francis, 2000; Duryea et al., 2007b; Uriarte et al., 2019; Nakamura, 2020). Additional structural factors like height, stem taper, and the presence of vines can influence a tree's risk of wind damage (Allen et al., 1997; Tabata et al., 2020; Torres-Martínez, 2021). Pruning history and root conditions (including root loss and available rooting space) can further impact a tree’s load-bearing capacity (Kane, 2008; Johnson et al., 2019; Klein et al., 2020).

Environmental conditions and tree site factors are also important considerations. Aspect of slope or exposure, along with site elevation and proximity to the storm center, have all been investigated to determine how environmental forces interact with individual trees or groups of trees (Salisbury et al., 2023). Grouped trees or those in protected sites might experience differing levels of damage compared to isolated trees or those in exposed sites (Duryea et al., 2007a; Duryea et al., 2007b). When considering group trees, consider the stem taper, soil drainage characteristics, height above or below the dominant canopy height, and species diversity (Mitchell, 1995). Collecting such data helps researchers assess not only the structural properties of trees but also the influence of their surroundings, ultimately informing storm preparedness and mitigation strategies.

3.9. The Future of Pre- and Post-Storm Assessment

We have presented what we consider current best practices for data collection in pre- and post-storm assessments. But we acknowledge that novel attributes and methods will likely arise as researchers and practitioners learn more and novel circumstances arise. As technologies like ground-based light detection and ranging (LiDAR; Nguyen et al. 2020) and photogrammetry (Roberts et al. 2018) become more widespread, new metrics—beyond what can be measured with traditional forestry tools—may emerge as valuable predictors of storm damage.

In an effort to create a living standard that evolves as methods advance, we have established the Urban Tree Storm Data Network (UTSDN, 2024). This network will include the published data standard, a bibliography of pre- and post-storm assessment research, a data repository for uploading storm data, and a wiki of metadata, response variables, and predictor variables (including descriptions, units, sources, etc.) used in past studies. We encourage both researchers and industry professionals to contribute their data using the standards documented here and draw from this resource as we work toward creating more resilient forests in a changing global climate.

4. Conclusion

Our work highlights the importance of developing standardized data collection methods for pre- and post-storm assessments in urban forestry. By adopting standard practices and data in community inventories and field research, scientists and practitioners can generate more reliable, comparable, and actionable information to predict tree failure and assess the health and resilience of urban forests in the face of severe and extreme weather. Consistency in data collection will improve the ability to draw meaningful conclusions from post-storm data, inform species selection and tree management practices, and ultimately contribute to more storm-resilient urban landscapes. Standardized approaches not only enhance the scientific rigor of post-storm studies but also facilitate collaboration across regions, helping cities and municipalities better prepare for and mitigate the impacts of future storms on their urban forests.

However, tree risk and condition ratings may not be publicly available to researchers. Moreover, biometric data such as stem diameter, height, and species identification may be collected in an unusable format (i.e., without units), contain errors, or utilize outdated or regionally specific taxonomic conventions. Consequently, reassessing the existing inventoried population is preferred.

References

- (AgMIP), Agricultural Model Intercomparison and Improvement Project. 2023. Agricultural Model Intercomparison and Improvement Project (AgMIP). AgMIP. Collection. [CrossRef]

- Allen BP, Pauley EF, Sharitz RR. 1997. Hurricane impacts on liana populations in an old-growth southeastern bottomland forest. The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society. 124:34–42. [CrossRef]

- ANSI. 2023. A300 Tree Care Standards. Tree Care Industry Asssociation, Inc. Manchester NH. 150 pp.

- Bond J. 2005. Final report 2003 storm damage protocol implementation (OH–03–346). <www.itreetools.org/storm/resources/2003%20SDAP%20Implementation.pdf> 20 pp.

- Bond J. 2012. Urban Tree Health: A Practical and Precise Estimation Method. Urban Forest Analytics, Geneva, NY.

- Bond J. 2013. Best Management Practices - Tree Inventories, Second Edition International Society of Arboriculture, Atlanta GA, 35 pp.

- Bloniarz DV, Ryan III HDP, Luley CJ, Bond J, Hawkins DC. 2001. An initial storm damage assessment protocol for urban and community forests. USDA Forest Service, Northeast Center for Urban and Community Forestry, University of Massachusetts, Amherst. <www.umass.edu/urbantree/icestorm/pages/StormAssessProtocol.doc >.

- Cadaval S, Clarke M, Roman LA, Conway TM, Koeser AK, Eisenman TS. 2024 Managing urban trees through storms in three United States cities. Landscape and Urban Planning. 248:105102. [CrossRef]

- Chen B. 2024. Typhoon-related tree damage and conservation implications for homestead windbreaks on the Ryukyu Archipelago: a case study of Yonaguni Island, Japan. Landscape and Ecological Engineering. 20:349–362. [CrossRef]

- Cromwell C, Giampaolo J, Hupy J, Miller Z, Chandrasekaran A. 2021. A systematic review of best practices for UAS data collection in forestry-related applications. Forests. 12(7):957. [CrossRef]

- DataCite Metadata Working Group. 2024. DataCite Metadata Schema Documentation for the Publication and Citation of Research Data and Other Research Outputs. Version 4.5. DataCite e.V. [CrossRef]

- Diaz J, Carnevale S, Millett C, Abd-Elrahman A, Britt K. 2020. Evaluating post-hurricane impacts in co-management areas: a framework for expert consensus. Natural Hazards. 103:1905-1916. [CrossRef]

- Dunster, JA, Smiley ET, Matheny N, Lilly L. 2013. Tree Risk Assessment Manual. International Society of Arboriculture. Champaign, Illinois, U.S. 194 pp.

- Duryea ML, Kampf E, Littell RC. 2007a. Hurricanes and the urban forest: I. Effects on southeastern United States coastal plain tree species. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry. 33(2):83-97. [CrossRef]

- Duryea ML, Kampf E, Littell RC, Rodríguez-Pedraza CD. 2007b. Hurricanes and the urban forest: II. Effects on tropical and subtropical tree species. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry. 33(2):98-112. [CrossRef]

- Edberg R, Berry A. 1999. Patterns of structural failures in urban trees: Coast live oak (Quercus agrifoua) Arboriculture & Urban Forestry. 25(1):48-55. [CrossRef]

- Elmqvist T, Rainey WE, Pierson ED, Cox PA. 1994. Effects of tropical cyclones Ofa and Val on the structure of a Samoan lowland rain Forest. Biotropica. 26:384–391. [CrossRef]

- Francis JK. 2000. Comparison of hurricane damage to several species of urban trees in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Journal of Arboriculture. 26:189–197. [CrossRef]

- Gal MS, Rubinfeld DL. 2019. Data standardization. New York University Law Review. 94:737.

- Hauer RJ, Wang W, Dawson JO. 1993. Ice storm damage to urban trees. Journal of Arboriculture. 19:187-187. [CrossRef]

- Hickman GW, Perry ED, Evans R. 1995. Validation of a tree failure evaluation system. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry. 21(5):233-234. [CrossRef]

- Jaenson R, Bassuk N, Schwager S. 1992. A statistical method for the accurate and rapid sampling of urban street tree populations. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry 18(4):171-183.

- Johnson G, Giblin C, Murphy R, North E, Rendahl A. 2019. Boulevard tree failures during wind loading events. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry. 45(6):259-69. [CrossRef]

- Kabir E, Guikema S, Kane B. 2018. Statistical modeling of tree failures during storms. Reliability Engineering & System Safety. 177:68-79. [CrossRef]

- Kamimura K, Kitagawa K, Saito S, Mizunaga H. 2012. Root anchorage of hinoki (Chamaecyparis obtusa (Sieb. Et Zucc.) Endl.) under the combined loading of wind and rapidly supplied water on soil: analyses based on tree-pulling experiments. European Journal of Forest Research. 131:219–227. [CrossRef]

- Kane B. 2008. Tree failure following a windstorm in Brewster, Massachusetts, USA. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 7(1):15-23. [CrossRef]

- Klein RW, Koeser AK, Kane B, Landry SM, Shields H, Lloyd S, Hansen G. 2020. Evaluating the likelihood of tree failure in Naples, Florida (United States) following Hurricane Irma. Forests. 11(5):485. [CrossRef]

- Koeser AK, Smiley ET, Hauer RJ, Kane B, Klein RW, Landry SM, Sherwood M. 2020. Can professionals gauge likelihood of failure? Insights from Tropical Storm Matthew. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 52:126701. [CrossRef]

- Koeser AK, Klein RW, Hauer RJ, Miesbauer JW, Freeman Z, Harchick C, Kane B. 2023. Defective or just different? Observed storm failure in four urban tree growth patterns. Forests. 14(5):988. [CrossRef]

- Lambert C, Landry S, Andreu MG, Koeser A, Starr G, Staudhammer C. 2022. Impact of model choice in predicting urban forest storm damage when data is uncertain. Landscape and Urban Planning. 226:104467. [CrossRef]

- Landry SM, Koeser AK, Kane B, Hilbert DR, McLean DC, Andreu M, Staudhammer CL. 2021. Urban forest response to Hurricane Irma: The role of landscape characteristics and sociodemographic context. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 61:127093. [CrossRef]

- Magarik YAS. 2021. “Roughly Speaking”: Why Do U.S. Foresters Measure DBH at 4.5 Feet? Society & Natural Resources, 34(6):725–744. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell SJ. 1995. The windthrow triangle: a relative windthrow hazard assessment procedure for forest managers. The Forestry Chronicle. 71(4):446-50. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura A. 2020. Relationship between snapping stems and modules of rupture of damaged trees by the typhoon in an urban green space. Journal of the Japanese Society of Revegetation Technology. 46:33–38. [CrossRef]

- NWS. Undated. National Weather Service Watch/Warning/Advisory Definitions. https://www.weather.gov/lwx/WarningsDefined Accessed 10-1-24.

- Nelson MF, Klein RW, Koeser AK, Landry SM, Kane B. 2022. The impact of visual defects and neighboring trees on wind-related tree failures. Forests. 22:13(7):978. [CrossRef]

- Nitoslawski SA, Galle NJ, Van Den Bosch CK, Steenberg JW. 2019. Smarter ecosystems for smarter cities? A review of trends, technologies, and turning points for smart urban forestry. Sustainable Cities and Society. 51:101770. [CrossRef]

- Nowak D. 2010. A Field Guide: Standards for Urban Forestry Data Collection (Version 2.0) https://www.unri.org/standards/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/Version-2.0-082010.pdf.

- Nguyen VT, Constant T, Kerautret B, Debled-Rennesson I, Colin F. 2020. A machine-learning approach for classifying defects on tree trunks using terrestrial LiDAR. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture. 171:105332. [CrossRef]

- Pokorny JD. 2003. Urban tree risk management: A community guide to program design and implementation. St. Paul (MN, USA): USDA Forest Service Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry. Technical Bulletin NA-TP-03-03. 204 p. https://www.fs.usda.gov/nrs/pubs/na/NA-TP-03-03.pdf.

- POWO 2024. "Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet; https://powo.science.kew.org/ Retrieved 15 October 2024.".

- QTRA. 2024. Cheshire (England, United Kingdom): Quantified Tree Risk Assessment. https://www.qtra.co.uk Accessed October 27th 2024.

- Roberts JW, Koeser AK, Abd-Elrahman AH, Hansen G, Landry SM, Wilkinson BE. Terrestrial photogrammetric stem mensuration for street trees. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 2018 Oct 1;35:66-71. [CrossRef]

- Roman LA, McPherson EG, Scharenbroch BC, Bartens J. 2013. Identifying common practices and challenges for local urban tree monitoring programs across the United States. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry. 39:292-299. [CrossRef]

- Roman LA, Scharenbroch BC, Östberg JP, Mueller LS, Henning JG, Koeser AK, Sanders JR, Betz DR, Jordan RC. 2017. Data quality in citizen science urban tree inventories. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 22:124-135. [CrossRef]

- Roman LA, van Doorn NS, McPherson EG, Scharenbroch BC, Henning JG, Mills JR, Hallett RA, Peper PJ. 2020. Urban tree monitoring: A field guide. USDA Forest Service, Northern Research Station.

- Salisbury AB, Koeser AK, Andreu MG, Chen Y, Freeman Z, Miesbauer JW, Herrera-Montes A, Kua CS, Nukina RH, Rockwell CA. 2023. Predictors of tropical cyclone-induced urban tree failure: An international scoping review. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change. 6:1168495. [CrossRef]

- Salisbury AB, Koeser AK, Andreu MG, Chen Y, Freeman Z, Miesbauer JW, Herrera-Montes A, Kua C-S, Nukina RH, Rockwell C, Shibata S, Thorn H, Wan B, Hauer RJ. 2024. Expanding a Hurricane Wind Resistance Rating System for Tree Species. Preprints. 2024041495. https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202404.1495/v1.

- Stewart DH. 1968. Data capture in forestry research. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series D (The Statistician). 18(4):377-411. [CrossRef]

- Stewart MG. Climate change risks and climate adaptation engineering for built infrastructure. Life-Cycle of Structural Systems: Design, Assessment, Maintenance and Management. 2015:89-108.

- Tabata K, Hashimoto H, Morimoto Y. 2020. Characteristics of large-scale typhoon damages to major tree species in Tadasu-no-Mori Forest, Shimogamo-Jinja shrine. Journal of the Japanese Institute of Landscape Architecture. 83:721–724. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Martínez E, Meléndez-Ackerman, EJ, Trujillo-Pinto A. 2021. Drivers of hurricane structural effects and mortality for urban trees in a community of San Juan, Puerto Rico. Acta Científica Una Revista Interdisciplinaria de Puerto Rico y el Caribe. 32:33–43.

- Urban Forest Strike Teams. 2024. Urban Forest Strike Teams. https://southernforests.org/ufst/ Accessed October 27, 2024.

- Uriarte M, Thompson J, Zimmerman JK. 2019. Hurricane María tripled stem breaks and doubled tree mortality relative to other major storms. Nature Communications 10:1–7. [CrossRef]

- UTSDN 2024. Urban Tree Storm Data Network https://www.utsdn.com/ access oct 18 2024.

- VALID 2024. Tree Risk-Benefit Management & Assessment. https://www.validtreerisk.com/ Accessed October 28 2024.

Table 1.

Recommended metadata to accompany publicly available datasets collected after a storm has damaged trees in the urban forest. These data may be recorded as variables within the dataset itself. Data should be reported in the methods section of a research paper documenting storm-related tree failures.

Table 1.

Recommended metadata to accompany publicly available datasets collected after a storm has damaged trees in the urban forest. These data may be recorded as variables within the dataset itself. Data should be reported in the methods section of a research paper documenting storm-related tree failures.

| Metadata |

Description |

Values or Units |

Source |

| Field crew identification |

Information about the individual(s)

who collected field data on the tree or plot |

Examples: job titles, relevant credentials, education/experience, etc. |

Roman et al. 2020 |

| Field crew experience level |

Categorized experience level of the most experienced individual on the field crew |

Novice, intermediate, expert |

Roman et al. 2020 |

| Location |

Information about the study site’s geographic position |

Latitude, longitude |

n/a |

| Street address |

| Date of storm |

Year, month, and day of storm event |

Calendar date |

n/a |

| Type of storm |

Categorized storm type based on conditions experienced |

Blizzard, Ice Storm, High Wind, Severe Thunderstorm, Tornado, Extreme Wind, Tropical Storm, Hurricane/Tropical Cyclone/Typhoon |

NWS undated |

| Storm severity |

Information about the storm’s intensity |

Maximum gust or sustained wind speed, precipitation |

n/a |

| Beaufort Scale, EF Scale |

| Storm Severity Source |

Source of the information regarding the storm’s intensity |

Examples: national weather agencies, local weather stations, direct measurement, etc. |

n/a |

| Other notes |

Site soil conditions, management history, past storm events, etc. |

|

Nowak, 2010 |

Table 2.

Pre-storm Inventory Data - Minimum Data Set.

Table 2.

Pre-storm Inventory Data - Minimum Data Set.

| Variable Type |

Variable |

Description |

Values or Units |

Source |

| Meta |

Date of observation |

Year, month, and day of field data collection |

Calendar date |

Roman et al., 2020 |

| Meta |

Tree record identifier |

Unique identifier that remains connected to the tree during future monitoring |

n/a |

Roman et al., 2020

Nowak, 2010 |

| Meta/Predictor |

Location |

Information about the tree’s geographic position in the landscape |

Latitude, longitude |

Roman et al. 2020

Nowak, 2010 |

| Street address |

| Predictor |

Species |

Tree species |

Genus, species, common name |

Roman et al. 2020

Nowak 2010 |

| Predictor |

Trunk diameter |

Diameter of main stem measured above ground |

cm (in.) |

Roman et al. 2020 Nowak 2010 |

| Meta |

Height to measurement of trunk diameter |

Point at which trunk diameter was measured given tree form and local conventions. |

cm (in.) or m (ft.) |

Roman et al., 2020 |

Table 3.

Pre-Storm Inventory Data - Optional Data.

Table 3.

Pre-Storm Inventory Data - Optional Data.

| Variable Type |

Variable |

Description |

Values or Units |

Source |

| Predictor |

Risk - likelihood of failure rating |

Assessed failure potential of the tree or tree part |

Varies by method |

QTRA, 2024

VALID, 2024

Salisbury et al., 2023

Dunster et al., 2017

Pokorny, 2003 |

| Predictor |

Risk - overall risk rating |

Assessed risk rating for the tree

NOTE: Includes likelihood of failure, likelihood of impact, severity of consequences |

Varies by method |

QTRA, 2024

VALID, 2024

Salisbury et al., 2023

Dunster et al., 2017

Pokorny, 2003 |

| Predictor |

Risk - observed defects |

Defects associated with greater likelihood of failure |

Examples: decay, cut root(s), split |

QTRA, 2024

VALID, 2024

Dunster et al., 2017

Nowak, 2010

Pokorny, 2003 |

| Predictor |

Risk - most significant defect |

Defect that is most likely to be associated with failure |

Examples: decay, cut root(s), split |

QTRA, 2024

VALID, 2024

Dunster et al., 2017

Nowak, 2010

Pokorny, 2003 |

| Predictor |

Tree condition/health |

A measure of how well the tree functions physiologically |

Varies by method |

Roman et al., 2020

Bond, 2012

Nowak, 2010

|

| Meta |

Notes for supervisory review |

Issues that cannot be resolved in the field; entering a note flags the tree for review by the project supervisor. |

n/a |

Roman et al., 2020 |

Table 4.

Post Storm Assessment - Minimum Data Set.

Table 4.

Post Storm Assessment - Minimum Data Set.

| Variable Type |

Variable |

Description |

Values or Units |

Source |

| Meta |

Date of observation |

Year, month, and day of field data collection |

Calendar date |

Roman et al., 2020 |

| Meta |

Tree record identifier |

Unique identifier that remains connected to the tree during future monitoring |

n/a |

Roman et al., 2020 |

| Meta/Predictor |

Location |

Information about the tree’s geographic position in the landscape |

Latitude, longitude |

Roman et al., 2020 |

| Street address |

| Predictor |

Species |

Tree species |

Genus, species, common name |

Roman et al., 2020 |

| Predictor |

Trunk diameter |

Diameter measured 1.4 m (4.5 ft.) above ground |

cm (in.) |

Roman et al., 2020 |

| Response |

Damage |

A description of the type and extent of damage to the tree |

Expressed as a % of how much the tree is impacted |

Salisbury et al., 2023 |

| Yes (1), no (0) |

| Categories such as none, low, moderate, extensive |

Table 5.

Post Storm Assessment - Optional Data.

Table 5.

Post Storm Assessment - Optional Data.

Table 6.

Additional Optional Data - can be collected pre-storm, post-storm, or both.

Table 6.

Additional Optional Data - can be collected pre-storm, post-storm, or both.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).