Submitted:

07 April 2025

Posted:

07 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

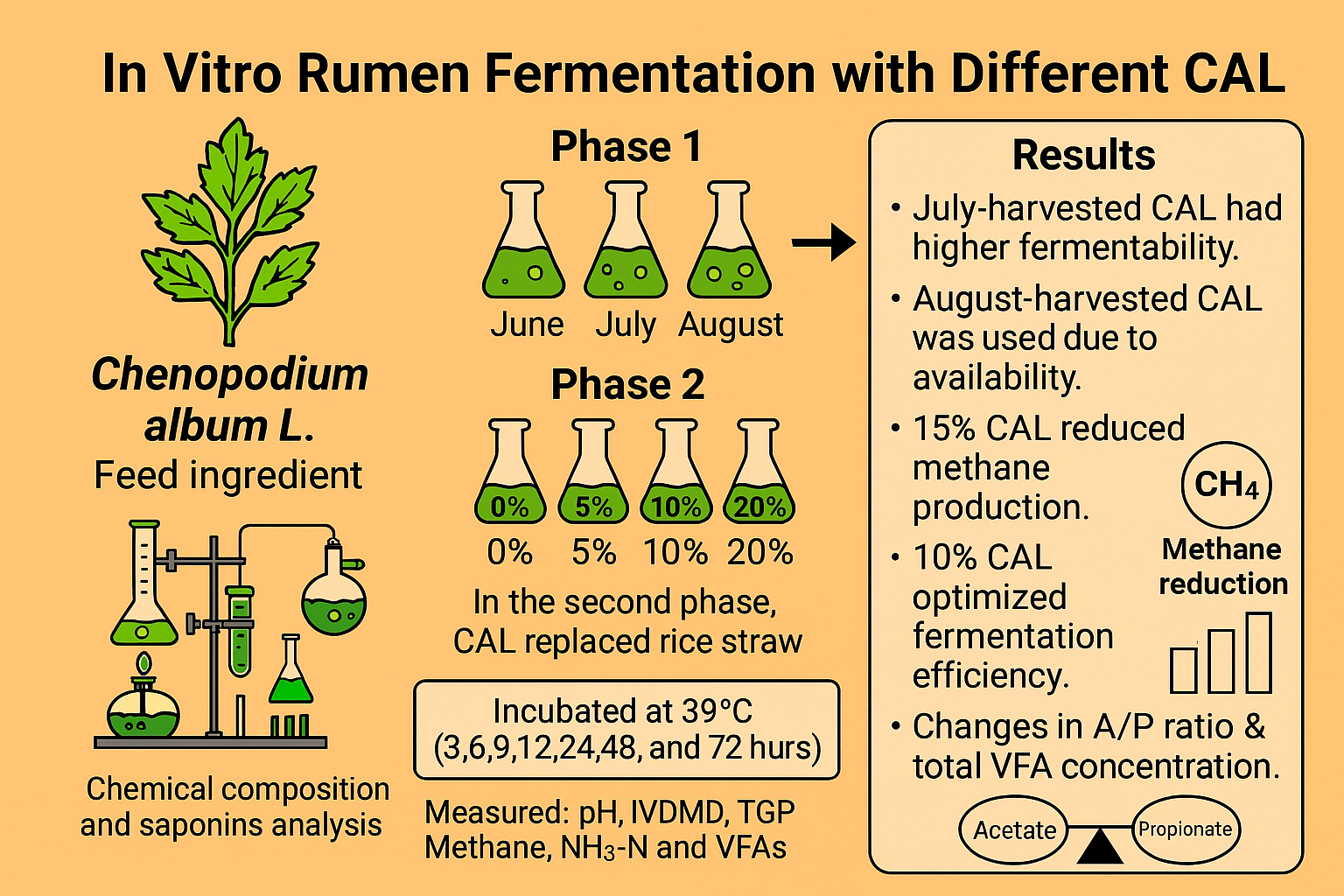

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

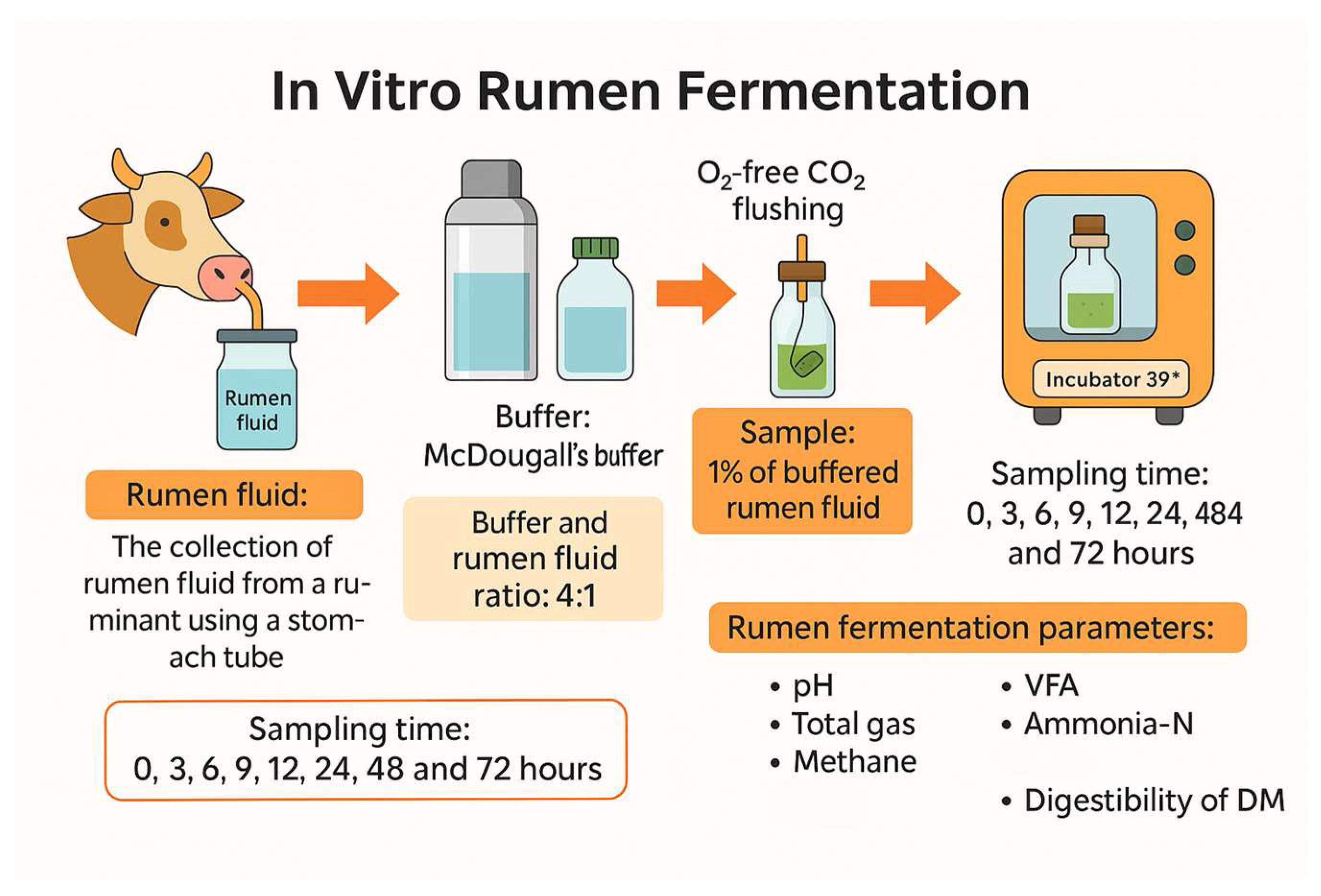

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design, Feed Preparation, and In Vitro Fermentation Procedure

2.2. Chemical Analysis and In Vitro Fermentation Measurements

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Compositions and Saponin Content of Chenopodium album L. at Different Times of Harvest

3.2. Evaluation of the Effect of Harvest Time of Chenopodium album L. on In Vitro Rumen Fermentation

3.3. Effect of Chenopodium album L. Substitution Levels on In Vitro Rumen Fermentation in Early Fattening Hanwoo

4. Discussion

4.1. Chemical Compositions and Saponin Content of Chenopodium album at Different Times of Harvest

4.2. Evaluation of the Effect of Harvest Time of Chenopodium album on In Vitro Rumen Fermentation

4.3. Effect of Chenopodium album Substitution Levels on In Vitro Rumen Fermentation in Early Fattening Hanwoo

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAL | Chenopodium Album L |

| CP | Crude Protein |

| NDF | Neutral Detergent Fiber |

| ADF | Acid Detergent Fiber |

| IVDMD | In Vitro Dry Matter Digestibility |

| A/P | Acetate to Propionate |

| VFA | Volatile Fatty Acid |

| GHG | Green House Gas |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| CH4 | Methane |

| GE | Gross Energy |

| OM | Organic Matter |

| DM | Dry matter |

| O2 | Oxygen |

| TGP | Total Gas Production |

| NH3-N | Ammonia-Nitrogen |

| EE | Ether Extract |

| CF | Crude Fiber |

| CA | Crude Ash |

| USA | United States America |

| SAS | Statistical Analysis System |

| GLM | General Linear Model |

| SEM | Standard Error of the Mean |

| CNU | Chungnam National University |

| IPET | Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, and Forestry |

| MAFRA | Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, Korea |

| KOICA | Korea International Cooperation Agency |

| HKNU | Hankyong National University |

References

- Tullo, E.; Finzi, A.; Guarino, M. Review: Environmental Impact of Livestock Farming and Precision Livestock Farming as a Mitigation Strategy. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 2751–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joos, F.; Prentice, I.C.; Sitch, S.; Meyer, R.; Hooss, G.; Plattner, G.-K.; Gerber, S.; Hasselmann, K. Global Warming Feedbacks on Terrestrial Carbon Uptake under the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Emission Scenarios. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2001, 15, 891–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, A.R.; Jouany, J.-P.; Newbold, J. Methane Production by Ruminants: Its Contribution to Global Warming. Ann Zootech 2000, 49, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.T. Cooperative Versus Competitive Efforts and Problem Solving. Rev. Educ. Res. 1995, 65, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, J.K. World Agriculture: Towards 2015/2030. An FAO Perspective. Edited by J. Bruinsma. Rome: FAO and London: Earthscan (2003), Pp. 432,£ 35.00 Paperback. ISBN 92-5-104835-5. Exp. Agric. 2004, 40, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, S.N.; Lim, K.B.; Kim, D.A. Sustainable Roughage Production in Korea-Review. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 1999, 12, 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.; Jeong, S.; Lee, M.; Seo, J.; Kam, D.K.; Kim, J.H.; Park, J.; Seo, S. Effects of Reducing Inclusion Rate of Roughages by Changing Roughage Sources and Concentrate Types on Intake, Growth, Rumen Fermentation Characteristics, and Blood Parameters of Hanwoo Growing Cattle (Bos Taurus Coreanae). Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 32, 1705–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risi, J.; Galwey, N.W.; Coaker, T.H. In Advances in Applied Biololgy. Chenopodium Grains Andes Inca Crops Mod. Agric. Acad. Landon 1984, 145–216. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.-S.; Jung, T.-H.; Shin, K.-O. Studies on the General Analysis and Antioxidant Component Analysis of Chenopodium Album Var. Centrorubrum and Biochemical Analysis of Blood of Mice Administered C. Album. Korean J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 51, 492–498. [Google Scholar]

- Gohara, A.A.; Elmazar, M.M.A. Isolation of Hypotensive Flavonoids from Chenopodium Species Growing in Egypt. Phytother. Res. Int. J. Devoted Med. Sci. Res. Plants Plant Prod. 1997, 11, 564–567. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary, S.P.; Sharma, D.K. Bioactive Constituents, Phytochemical and Pharmacological Properties of Chenopodium Album: A Miracle Weed. Int J Pharmacogn 2014, 1, 545–552. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson, R.; Hanczakowski, P.; Partap, T.; Mathew, K.S.; Atul, K.V.R. Chenopodium Album in India, a Food Crop for the Production of Leaf Protein Concentrates. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference of Leaf Protein Research, August 1985; pp. 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Choo, Y.-S.; Song, S.-D. Ecophysiological Characteristics of Chenopodiaceous Plants-An Approach through Inorganic and Organic Solutes. Korean J. Ecol. 2000, 23, 397–406. [Google Scholar]

- Khurana, S.C.; Malik, Y.S.; Pandita, M.L. Herbicidal Control of Weeds in Potato Cv. Kufri Badshah. 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee, S.K. Handbook of Medicinal Plants. No Title 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, S.; Itankar, P. Extraction, Isolation and Identification of Flavonoid from Chenopodium Album Aerial Parts. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2018, 8, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, S.-U.; Heo, B.-G.; Park, Y.-S.; Kim, D.-K.; Gorinstein, S. Total Phenolics Level, Antioxidant Activities and Cytotoxicity of Young Sprouts of Some Traditional Korean Salad Plants. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2009, 64, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, T.; Chen, D.; Zhang, N.; Si, B.; Deng, K.; Tu, Y.; Diao, Q. Effects of Tea Saponin Supplementation on Nutrient Digestibility, Methanogenesis, and Ruminal Microbial Flora in Dorper Crossbred Ewe. Animals 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, A.N.; McAllister, T.A.; Van Herk, F.H.; Cheng, K.-J.; Newbold, C.J.; Cheeke, P.R. Effect of Yucca Schidigera on Ruminal Fermentation and Nutrient Digestion in Heifers1. J. Anim. Sci. 1999, 77, 2554–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.K.; Sehgal, S. In Vitro and in Vivo Availability of Iron from Bathua (Chenopodium Album) and Spinach (Spinacia Oleracia) Leaves. J. Food Sci. Technol. -Mysore- 2002, 39, 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, R.J.; Arthaud, L.; Newbold, C.J. Influence of Yucca Shidigera Extract on Ruminal Ammonia Concentrations and Ruminal Microorganisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1994, 60, 1762–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, P.-N.; Jeong, C.-S. Anti-Gastritis and Anti-Oxidant Effects of Chenopodium Album Linne Fractions and Betaine. Biomol. Ther. 2010, 18, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Ye, W.C.; Wang, Z.T.; Matsuda, H.; Kubo, M.; But, P.P.H. Antipruritic and Antinociceptive Effects of Chenopodium Album L. in Mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 81, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoobchandani, M.; Ojeswi, B.K.; Sharma, B.; Srivastava, M.M. Chenopodium Album Prevents Progression of Cell Growth and Enhances Cell Toxicity in Human Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2009, 2, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, P.; Jeong, C.-S. Effects of Chenopodium Album Linne on Gastritis and Gastric Cancer Cell Growth. Biomol. Ther. 2011, 19, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, B.L.; Poulev, A.; Kuhn, P.; Grace, M.H.; Lila, M.A.; Raskin, I. Quinoa Seeds Leach Phytoecdysteroids and Other Compounds with Anti-Diabetic Properties. Food Chem. 2014, 163, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horio, T.; Yoshida, K.; Kikuchi, H.; Kawabata, J.; Mizutani, J. A Phenolic Amide from Roots of Chenopodium Album. Phytochemistry 1993, 33, 807–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavaud, C.; Voutquenne, L.; Bal, P.; Pouny, I. Saponins from Chenopodium Album. Fitoterapia 2000, 71, 338–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutillo, F.; D’Abrosca, B.; DellaGreca, M.; Di Marino, C.; Golino, A.; Previtera, L.; Zarrelli, A. Cinnamic Acid Amides from Chenopodium Album: Effects on Seeds Germination and Plant Growth. Phytochemistry 2003, 64, 1381–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutillo, F.; D’Abrosca, B.; DellaGreca, M.; Zarrelli, A. Chenoalbicin, a Novel Cinnamic Acid Amide Alkaloid from Chenopodium Album. Chem. Biodivers. 2004, 1, 1579–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DellaGreca, M.; Di Marino, C.; Zarrelli, A.; D’Abrosca, B. Isolation and Phytotoxicity of Apocarotenoids from Chenopodium a Lbum. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 1492–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutillo, F.; DellaGreca, M.; Gionti, M.; Previtera, L.; Zarrelli, A. Phenols and Lignans from Chenopodium Album. Phytochem. Anal. Int. J. Plant Chem. Biochem. Tech. 2006, 17, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, G.; Makkar, H.P.S. Methane Mitigation from Ruminants Using Tannins and Saponins. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2012, 44, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dębski; Bogdan i Comparison of Antioxidant Potential and Mineral Composition of Quinoa and Lamb’s Quarters Weed ( Chenopodium Album ). Probl. Hig. Epidemiol. 2018, 99, 88–93.

- Tang, W.; Guo, H.; Yin, J.; Ding, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, T.; Yang, C.; Xiong, W.; Zhong, S.; Tao, Q. Germination Ecology of Chenopodium Album L. and Implications for Weed Management. PloS One 2022, 17, e0276176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damdinsuren, G. The issue of feed preparation of some species for undesirable plants. Ph.D Dissertation, Mongolian University of Life Sciences, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Poonia, A.; Upadhayay, A. Chenopodium Album Linn: Review of Nutritive Value and Biological Properties. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 3977–3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, D.; Pal, M. Chenopodium: Seed Protein, Fractionation and Amino Acid Composition. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 1998, 49, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, A.; Shukla, S.; Ohri, D. Genetic Variability and Heritability of Selected Traits during Different Cuttings of Vegetable Chenopodium. INDIAN J. Genet. PLANT Breed. 2003, 63, 359–360. [Google Scholar]

- McDougall, E.I. Studies on Ruminant Saliva. 1. The Composition and Output of Sheep’s Saliva. Biochem. J. 1948, 43, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC INTERNATIONAL, 21st Ed. ed; AOAC International: Washington, DC, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for Dietary Fiber, Neutral Detergent Fiber, and Nonstarch Polysaccharides in Relation to Animal Nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bot, M.; Thibault, J.; Pottier, Q.; Boisard, S.; Guilet, D. An Accurate, Cost-Effective and Simple Colorimetric Method for the Quantification of Total Triterpenoid and Steroidal Saponins from Plant Materials. Food Chem. 2022, 383, 132597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuvink, J.M.W.; Spoelstra, S.F. Interactions between Substrate, Fermentation End-Products, Buffering Systems and Gas Production upon Fermentation of Different Carbohydrates by Mixed Rumen Microorganisms in Vitro. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1992, 37, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Song, J.Y.; Bae, G.S.; Lee, M.H.; Jung, S.Y.; Kim, E.J. Effects of Energy Feed Sources on Hanwoo Rumen Fermentation Characteristics and Microbial Amino Acids Composition in Vitro. Ann Anim Res Sci 2022, 33, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaney, A.L.; Marbach, E.P. Modified Reagents for Determination of Urea and Ammonia. Clin. Chem. 1962, 8, 130–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAS, S. V9. 4 User’s Guide. SAS Inst. Inc Cary NC 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, W.; Yuan, L.; Qu, X. CFD Simulation of Hydrodynamic Behaviors and Aerobic Sludge Granulation in a Stirred Tank with Lower Ratio of Height to Diameter. Biochem. Eng. J. 2018, 137, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, M.C.; Hatfield, R.D.; Kalscheur, K.F. Fermentation and Chemical Composition of High-Moisture Lucerne Leaf and Stem Silages Harvested at Different Stages of Development Using a Leaf Stripper. Grass Forage Sci. 2019, 74, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmonari, A.; Fustini, M.; Canestrari, G.; Grilli, E.; Formigoni, A. Influence of Maturity on Alfalfa Hay Nutritional Fractions and Indigestible Fiber Content. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 7729–7734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yari, M.; Valizadeh, R.; Naserian, A.A.; Jonker, A.; Azarfar, A.; Yu, P. Effects of Including Alfalfa Hay Cut in the Afternoon or Morning at Three Stages of Maturity in High Concentrate Rations on Dairy Cows Performance, Diet Digestibility and Feeding Behavior. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2014, 192, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebeid, H.M.; Kholif, A.E.; El-Bordeny, N.; Chrenkova, M.; Mlynekova, Z.; Hansen, H.H. Nutritive Value of Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa) as a Feed for Ruminants: In Sacco Degradability and in Vitro Gas Production. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 35241–35252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedapo, A.; Jimoh, F.; Afolayan, A. Comparison of the Nutritive Value and Biological Activities of the Acetone, Methanol and Water Extracts of the Leaves of Bidens Pilosa and Chenopodium Album. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2011, 68, 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, L.; Yadav, N.; Kumar, A.R.; Gupta, A.K.; Chacko, J.; Parvin, K.; Tripathi, U. Preparation of Value Added Products from Dehydrated Bathua Leaves (Chenopodium Album Linn.). 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Odhav, B.; Beekrum, S.; Akula, U.S.; Baijnath, H. Preliminary Assessment of Nutritional Value of Traditional Leafy Vegetables in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2007, 20, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiretti, P.G.; Gai, F.; Tassone, S. Fatty Acid Profile and Nutritive Value of Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa Willd.) Seeds and Plants at Different Growth Stages. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2013, 183, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolayan, A.J.; Jimoh, F.O. Nutritional Quality of Some Wild Leafy Vegetables in South Africa. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 60, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YILDIRIM, E.; DURSUN, A.; TURAN, M. Determination of the Nutrition Contents of the Wild Plants Used as Vegetables in Upper Coruh Valley. Turk. J. Bot. 2001, 25, 367–371. [Google Scholar]

- Oguntona, C.R.; Razaq, M.A.; Akintola, T.T. Pattern of Dietary Intake and Consumption of Street Foods among Nigerian Students. Nutr. Health 1998, 12, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szakiel, A.; Pączkowski, C.; Henry, M. Influence of Environmental Abiotic Factors on the Content of Saponins in Plants. Phytochem. Rev. 2011, 10, 471–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anseong Climate.

- Pecetti, L.; Tava, A.; Romani, M.; Benedetto, M.G.D.; Corsi, P. Variety and Environment Effects on the Dynamics of Saponins in Lucerne (Medicago Sativa L.). Eur. J. Agron. 2006, 25, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylwia, G.; Leszczynski, B.; Wieslaw, O. Effect of Low and High-Saponin Lines of Alfalfa on Pea Aphid. J. Insect Physiol. 2006, 52, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budan, A.; Tessier, N.; Saunier, M.; Gillmann, L.; Hamelin, J.; Chicoteau, P.; Richomme, P.; Guilet, D. Effect of Several Saponin Containing Plant Extracts on Rumen Fermentation in Vitro, Tetrahymena Pyriformis and Sheep Erythrocytes. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2013, 11, 576–582. [Google Scholar]

- Oakenfull, D. Saponins in Food—A Review. Food Chem. 1981, 7, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balde, A.T.; Vandersall, J.H.; Erdman, R.A.; Reeves, J.B.; Glenn, B.P. Effect of Stage of Maturity of Alfalfa and Orchardgrass on in Situ Dry Matter and Crude Protein Degradability and Amino Acid Composition. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1993, 44, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Christensen, D.A.; McKinnon, J.J.; Markert, J.D. Effect of Variety and Maturity Stage on Chemical Composition, Carbohydrate and Protein Subfractions, in Vitro Rumen Degradability and Energy Values of Timothy and Alfalfa. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2003, 83, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.X.; Tayo, G.O.; Tan, Z.L.; Sun, Z.H.; Wang, M.; Ren, G.P.; Han, X.F. Use of In Vitro Gas Production Technique to Investigate Interactions between Rice Straw, Wheat Straw, Maize Stover and Alfalfa or Clover. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci 2008, 21, 1278–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soest, P.J.V. Rice Straw, the Role of Silica and Treatments to Improve Quality. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2006, 130, 137–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, P.S.; Mir, Z.; Broersma, K.; Bittman, S.; Hall, J.W. Prediction of Nutrient Composition and in Vitro Dry Matter Digestibility from Physical Characteristics of Forages. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1995, 55, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, P.J. Nutritional Ecology of the Ruminant, 2nd ed.; Cornell University Press, 1994; ISBN 978-0-8014-2772-5. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, P.; Greenhalgh, J.F.D.; Morgan, C.A.; Greenhalgh, J.F.D.; Morgan, C.A.; Edwards, R.; Sinclair, L.; Wilkinson, R. Animal Nutrition, 7th ed.; 2010; ISBN 978-1-4082-0427-6. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, D.C.; Cochran, R.C.; Currie, P.O. Forage Maturity Effects on Rumen Fermentation, Fluid Flow, and Intake in Grazing Steers. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. Range Manag. Arch. 1987, 40, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muck, R.E.; Filya, I.; Contreras-Govea, F.E. Inoculant Effects on Alfalfa Silage: In Vitro Gas and Volatile Fatty Acid Production. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 5115–5125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blümmel, M.; Makkar, H.P.S.; Becker, K. In Vitro Gas Production: A Technique Revisited. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 1997, 77, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.A.; Johnson, D.E. Methane Emissions from Cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 1995, 73, 2483–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilman, D.; Foulkes, G.R.; Givens, D.I. The Rate and Extent of Cell-Wall Degradation in Vitro for 40 Silages Varying in Composition and Digestibility. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1996, 63, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topps, J.H.; Reed, W.D.C.; Elliott, R.C. The Effect of Season and of Supplementary Feeding on the Rumen Contents of African Cattle Grazing Subtropical Herbage:II. pH Values and Concentration and Proportions of Volatile Fatty Acids. J. Agric. Sci. 1965, 64, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungate, R.E. The Rumen and Its Microbes; Elsevier, 2013; ISBN 1-4832-6362-2. [Google Scholar]

- Eskeland, B.; Pfander, W.H.; Preston, R.L. Intravenous Energy Infusion in Lambs: Effects on Nitrogen Retentin, Plasma Free Amino Acids and Plasma Urea Nitrogen. Br. J. Nutr. 1974, 31, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, D.; Rouzbehan, Y.; Rezaei, J. Effect of Harvest Date and Nitrogen Fertilization Rate on the Nutritive Value of Amaranth Forage (Amaranthus Hypochondriacus). Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2012, 171, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, A.K.; Saxena, J. The Effect and Mode of Action of Saponins on the Microbial Populations and Fermentation in the Rumen and Ruminant Production. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2009, 22, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wina, E.; Muetzel, S.; Becker, K. The Impact of Saponins or Saponin-Containing Plant Materials on Ruminant ProductionA Review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 8093–8105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Song, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y. Fermentation Quality and Microbial Community of Corn Stover or Rice Straw Silage Mixed With Soybean Curd Residue. Animals 2022, 12, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunun, P.; Gunun, N.; Khejornsart, P.; Ouppamong, T.; Cherdthong, A.; Wanapat, M.; Sirilaophaisan, S.; Yuangklang, C.; Polyorach, S.; Kenchaiwong, W.; et al. Effects Of Antidesma Thwaitesianum Muell. Arg. Pomace as a Source of Plant Secondary Compounds on Digestibility, Rumen Environment, Hematology, and Milk Production in Dairy Cows. Anim. Sci. J. 2018, 90, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, A.; Pinloche, E.; Preskett, D.; Newbold, C.J. Effects and Mode of Action of Chitosan and Ivy Fruit Saponins on the Microbiome, Fermentation and Methanogenesis in the Rumen Simulation Technique. Fems Microbiol. Ecol. 2015, fiv160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Zi, X.; Zhou, H.; Lv, R.; Tang, J.; Cai, Y. Silage Fermentation and Ruminal Degradation of Cassava Foliage Prepared With Microbial Additive. Amb Express 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pk, M. Effect of Individual vs. Combined Supplementation of Tamarind Seed Husk and Soapnut on Methane Production, Feed Fermentation and Protozoal Population in Vitro. Approaches Poult. Dairy Vet. Sci. 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampapon, T.; Phesatcha, K.; Wanapat, M. Effects of Phytonutrients on Ruminal Fermentation, Digestibility, and Microorganisms in Swamp Buffaloes. Animals 2019, 9, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shokryzadan, P.; Rajion, M.A.; Goh, Y.M.; Ishak, I.; Ramlee, M.F.; Jahromi, M.F.; Ebrahimi, M. Mangosteen Peel Can Reduce Methane Production and Rumen Biohydrogenation in Vitro. South Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 46, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliana, P.; Laconi, E.B.; Jayanegara, A.; Achmadi, S.S.; Samsudin, A.A. Effect of Napier Grass Supplemented With Gliricidia Sepium, Sapindus Rarak or Hibiscus Rosa-Sinensis on in Vitro Rumen Fermentation Profiles and Methanogenesis. J. Indones. Trop. Anim. Agric. 2019, 44, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Meng, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, Z. Ferric Citrate, Nitrate, Saponin and Their Combinations Affect in Vitro Ruminal Fermentation, Production of Sulphide and Methane and Abundance of Select Microbial Populations. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 127, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kholif, A.E. A Review of Effect of Saponins on Ruminal Fermentation, Health and Performance of Ruminants. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundal, J.S.; Wadhwa, M.; Bakshi, M.P.S. Effect of Herbal Feed Additives Containing Saponins on Rumen Fermentation Pattern. Indian J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 90, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment/Feed | Ingredients (%) | Chemical compositions (% DM) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice straw | CAL | Concentrate | Dry matter | Crude protein | Ether extract | Crude ash | NDF1 | ADF2 | |

| Control (C) | 30 | 0 | 70 | 99.53 | 13.96 | 6.20 | 6.65 | 41.80 | 21.92 |

| T1 | 25 | 5 | 70 | 99.52 | 14.40 | 6.21 | 6.50 | 40.83 | 21.25 |

| T2 | 20 | 10 | 70 | 99.51 | 14.83 | 6.23 | 6.34 | 39.87 | 20.59 |

| T3 | 15 | 15 | 70 | 99.50 | 15.26 | 6.25 | 6.19 | 38.90 | 19.92 |

| T4 | 10 | 20 | 70 | 99.50 | 15.69 | 6.27 | 6.03 | 37.93 | 19.25 |

| Rice straw | 99.70 | 3.87 | 1.82 | 7.50 | 73.34 | 47.22 | |||

| CAL (August) | 99.55 | 12.49 | 2.18 | 4.57 | 54.01 | 33.87 | |||

| Concentrate | 99.45 | 18.29 | 8.07 | 6.29 | 28.28 | 11.08 | |||

| Harvested time | Moisture (%) | Crude protein | Ether extract | Crude ash | Crude fiber | NDF1 | ADF2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (% DM) | |||||||

| June | 80.83a | 18.73a | 4.92a | 4.57a | 17.36c | 43.04c | 21.69c |

| July | 79.52b | 13.24b | 1.96b | 3.71b | 18.78b | 43.95b | 27.53b |

| August | 62.50c | 12.49b | 2.18b | 4.40a | 26.09a | 54.01a | 33.87a |

| SEM3 | 0.360 | 0.360 | 0.130 | 0.130 | 0.240 | 0.220 | 0.210 |

| p-value | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.0072 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Harvest time | Saponins (%) |

|---|---|

| June | 6.597 |

| July | 6.619 |

| August | 7.047 |

| Treatment1 | |

| Control | 0.00 |

| T1 | 0.21 |

| T2 | 0.42 |

| T3 | 0.63 |

| T4 | 0.85 |

| Incubation time (h) | Treatments1 | SEM2 | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| June | July | August | |||

| pH | |||||

| 0 | 7.01a | 7.01a | 6.99b | 0.005 | 0.0370 |

| 3 | 6.77 | 6.77 | 6.79 | 0.008 | 0.1850 |

| 6 | 6.83a | 6.73b | 6.71b | 0.014 | 0.0021 |

| 9 | 6.69 | 6.68 | 6.70 | 0.006 | 0.0095 |

| 12 | 6.72a | 6.67b | 6.65b | 0.011 | 0.0102 |

| 24 | 6.65b | 6.63b | 6.67a | 0.004 | 0.0027 |

| 48 | 6.70b | 6.65c | 6.75a | 0.006 | <.0001 |

| 72 | 6.78a | 6.71b | 6.74b | 0.011 | 0.0083 |

| IVDMD (%) | |||||

| 3 | 38.09a | 37.31b | 31.92c | 0.055 | <.0001 |

| 6 | 41.06a | 38.82b | 30.87c | 0.160 | <.0001 |

| 9 | 46.50a | 41.76b | 35.76c | 0.181 | <.0001 |

| 12 | 55.32a | 45.93b | 40.49c | 0.916 | <.0001 |

| 24 | 72.87a | 68.48b | 52.35c | 0.157 | <.0001 |

| 48 | 77.64a | 73.59b | 62.00c | 0.186 | <.0001 |

| 72 | 82.62a | 72.14b | 60.99c | 0.209 | <.0001 |

| NH3-N (mg/100mL) | |||||

| 0 | 2.47a | 1.57c | 1.83b | 0.058 | <.0001 |

| 3 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.53 | 0.090 | 0.1890 |

| 6 | 3.4 | 3.47 | 3.27 | 0.079 | 0.2690 |

| 9 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 0.094 | 0.1517 |

| 12 | 2.40b | 2.60a | 2.23b | 0.050 | 0.0066 |

| 24 | 4.70a | 3.56b | 4.96a | 0.250 | 0.0153 |

| 48 | 11.00a | 11.00a | 8.97b | 0.366 | 0.0115 |

| 72 | 17.50a | 15.30b | 14.10c | 0.111 | <.0001 |

| Incubation time (h) | Treatments1 | SEM2 | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| June | July | August | |||

| TGP (mL/g DM) | |||||

| 3 | 10.59b | 12.22a | 10.22b | 0.321 | 0.0098 |

| 6 | 18.96 | 19.96 | 19.46 | 0.415 | 0.3025 |

| 9 | 24.13 | 22.18 | 21.34 | 0.925 | 0.1711 |

| 12 | 40.06b | 43.89a | 42.11ab | 0.643 | 0.0161 |

| 24 | 79.91b | 91.68a | 75.78b | 1.490 | 0.0007 |

| 48 | 104.44b | 122.60a | 81.24c | 1.668 | <.0001 |

| 72 | 119.74b | 136.52a | 107.17c | 1.518 | <.0001 |

| CH4, (mL/g DMD) | |||||

| 3 | 0.61c | 1.00a | 0.88b | 0.009 | <.0001 |

| 6 | 1.35c | 2.03b | 2.93a | 0.076 | <.0001 |

| 9 | 2.33c | 3.01b | 3.97a | 0.074 | <.0001 |

| 12 | 5.46c | 6.54b | 8.04a | 0.154 | <.0001 |

| 24 | 12.33c | 15.88b | 18.31a | 0.285 | <.0001 |

| 48 | 16.64c | 24.84a | 19.04b | 0.112 | <.0001 |

| 72 | 23.49b | 29.57a | 26.53ab | 1.074 | 0.0202 |

| Incubation time (h) | Treatment1 | SEM2 | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| June | July | August | |||

| Total VFA (mM) | |||||

| 0 | 33.01a | 33.16a | 32.20b | 0.089 | 0.0006 |

| 3 | 41.89a | 41.58ab | 41.19b | 0.129 | 0.0242 |

| 6 | 39.14a | 39.10a | 37.65b | 0.394 | 0.0414 |

| 9 | 38.77c | 43.29b | 44.28a | 0.261 | <.0001 |

| 12 | 52.46b | 60.66a | 53.10b | 0.215 | <.0001 |

| 24 | 75.06a | 73.57a | 67.55b | 0.449 | <.0001 |

| 48 | 99.28a | 99.67a | 86.93b | 0.262 | <.0001 |

| 72 | 102.65b | 103.87a | 94.82c | 0.239 | <.0001 |

| Acetate (%) | |||||

| 0 | 61.21a | 60.93a | 60.32b | 0.088 | 0.0010 |

| 3 | 62.92a | 61.45b | 61.80b | 0.146 | 0.0009 |

| 6 | 61.99 | 61.00 | 62.17 | 0.391 | 0.1527 |

| 9 | 63.74a | 62.66b | 62.24c | 0.061 | <.0001 |

| 12 | 65.15 | 65.01 | 64.86 | 0.116 | 0.2669 |

| 24 | 67.35a | 65.70b | 66.18b | 0.245 | 0.0080 |

| 48 | 66.58a | 66.50a | 65.18b | 0.097 | <.0001 |

| 72 | 66.75a | 65.87b | 65.89b | 0.073 | 0.0002 |

| Propionate (%) | |||||

| 0 | 17.69 | 17.80 | 18.14 | 0.049 | 0.0016 |

| 3 | 19.25 | 20.24 | 19.76 | 0.103 | 0.0015 |

| 6 | 18.97 | 20.18 | 18.47 | 0.151 | 0.0005 |

| 9 | 18.67b | 19.37a | 18.12c | 0.129 | 0.0014 |

| 12 | 19.31b | 19.77a | 19.27b | 0.081 | 0.0079 |

| 24 | 18.84b | 20.10a | 18.29b | 0.264 | 0.0073 |

| 48 | 18.81a | 18.52b | 18.94a | 0.078 | 0.0241 |

| 72 | 18.53a | 18.59a | 17.98b | 0.099 | 0.0090 |

| Iso-butyrate (%) | |||||

| 0 | 3.36b | 3.37b | 3.45a | 0.012 | 0.0027 |

| 3 | 2.75b | 2.77ab | 2.79a | 0.010 | 0.1106 |

| 6 | 2.96 | 2.97 | 3.05 | 0.031 | 0.1557 |

| 9 | 2.92a | 2.71b | 2.42c | 0.020 | <.0001 |

| 12 | 2.26a | 2.00b | 2.24a | 0.020 | 0.0001 |

| 24 | 1.76b | 1.81b | 1.94a | 0.014 | 0.0002 |

| 48 | 1.78b | 1.71c | 1.89a | 0.003 | <.0001 |

| 72 | 1.88a | 1.81b | 1.89a | 0.014 | 0.0142 |

| Butyrate (%) | |||||

| 0 | 11.32b | 11.50a | 11.55a | 0.025 | 0.0013 |

| 3 | 9.85b | 10.21a | 10.29a | 0.030 | <.0001 |

| 6 | 10.36 | 10.07 | 10.42 | 0.172 | 0.3739 |

| 9 | 9.16b | 9.94a | 9.19b | 0.104 | 0.0029 |

| 12 | 8.79b | 9.02a | 9.10a | 0.057 | 0.0201 |

| 24 | 8.04c | 8.30b | 9.02a | 0.043 | <.0001 |

| 48 | 8.32c | 8.93b | 9.51a | 0.101 | 0.0005 |

| 72 | 8.14b | 9.22a | 9.31a | 0.045 | <.0001 |

| Iso-valerate (%) | |||||

| 0 | 3.57b | 3.58b | 3.65a | 0.008 | 0.0011 |

| 3 | 2.97 | 3.00 | 3.01 | 0.014 | 0.1394 |

| 6 | 3.19 | 3.15 | 3.24 | 0.043 | 0.4181 |

| 9 | 3.01a | 2.89b | 2.54c | 0.024 | <.0001 |

| 12 | 2.40a | 2.21b | 2.40a | 0.009 | <.0001 |

| 24 | 2.13b | 2.11b | 2.49a | 0.028 | 0.0001 |

| 48 | 2.59b | 2.49c | 2.66a | 0.016 | 0.0008 |

| 72 | 2.88a | 2.80b | 2.92a | 0.016 | 0.0023 |

| Valerate (%) | |||||

| 0 | 2.86b | 2.83c | 2.89a | 0.005 | 0.0003 |

| 3 | 2.3 | 2.34 | 2.35 | 0.015 | 0.1207 |

| 6 | 2.54 | 2.54 | 2.65 | 0.035 | 0.0989 |

| 9 | 2.48a | 2.42b | 2.19c | 0.015 | <.0001 |

| 12 | 2.08b | 1.95c | 2.13a | 0.006 | <.0001 |

| 24 | 1.92b | 1.96b | 2.10a | 0.022 | 0.0027 |

| 48 | 1.83b | 1.83b | 1.97a | 0.006 | <.0001 |

| 72 | 1.87b | 1.90b | 1.98a | 0.011 | 0.0011 |

| A: P3 ratio | |||||

| 0 | 3.46a | 3.42a | 3.33b | 0.014 | 0.0014 |

| 3 | 3.27a | 3.04c | 3.13b | 0.023 | 0.0011 |

| 6 | 3.27a | 3.02b | 3.37a | 0.047 | 0.0051 |

| 9 | 3.41b | 3.24b | 3.24b | 0.019 | 0.0009 |

| 12 | 3.38a | 3.29b | 3.37a | 0.019 | 0.0345 |

| 24 | 3.58a | 3.27b | 3.62a | 0.063 | 0.015 |

| 48 | 3.54a | 3.59a | 3.44b | 0.018 | 0.0034 |

| 72 | 3.60ab | 3.54b | 3.66a | 0.022 | 0.0213 |

| Incubation times (h) | Treatment1 | SEM2 | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | |||

| pH | |||||||

| 3 | 6.76b | 6.78b | 6.83a | 6.82a | 6.83a | 0.010 | 0.0006 |

| 6 | 6.75c | 7.04a | 6.85b | 6.86b | 6.81bc | 0.024 | <.0001 |

| 9 | 6.67d | 6.69c | 6.74b | 6.83a | 6.72bc | 0.014 | 0.0002 |

| 12 | 6.74a | 6.63b | 6.58c | 6.59c | 6.57c | 0.009 | <.0001 |

| 24 | 6.55a | 6.53a | 6.54a | 6.53a | 6.48b | 0.013 | 0.0184 |

| 48 | 6.54a | 6.48d | 6.50c | 6.50c | 6.53b | 0.009 | <.0001 |

| 72 | 6.45 | 6.48 | 6.47 | 6.46 | 6.46 | 0.014 | 0.4068 |

| IVDMD (%) | |||||||

| 3 | 24.27bc | 28.94a | 23.57c | 25.85b | 14.71d | 0.613 | <.0001 |

| 6 | 33.42b | 37.13a | 34.57ab | 35.46ab | 27.90c | 0.938 | 0.0004 |

| 9 | 47.89a | 43.39bc | 44.74b | 48.50a | 42.03c | 0.605 | <.0001 |

| 12 | 51.38b | 54.28a | 55.67a | 54.61a | 44.43c | 0.756 | <.0001 |

| 24 | 64.26b | 65.46ab | 67.16a | 67.29a | 59.62c | 0.740 | 0.0001 |

| 48 | 76.11b | 76.70b | 78.12a | 76.54b | 71.06c | 0.382 | <.0001 |

| 72 | 80.22a | 80.90a | 80.20a | 80.89a | 73.66b | 0.480 | <.0001 |

| NH3-N (mg/100mL) | |||||||

| 0 | 1.57c | 1.51c | 1.75b | 1.95a | 1.52c | 0.048 | 0.0003 |

| 3 | 1.77c | 2.97a | 2.14b | 2.88a | 2.37b | 0.086 | <.0001 |

| 6 | 1.18c | 1.60b | 1.55b | 1.72ab | 1.86a | 0.073 | 0.0008 |

| 9 | 1.43a | 1.26b | 0.83d | 1.18b | 1.01c | 0.040 | <.0001 |

| 12 | 1.77a | 1.57c | 1.69ab | 1.66b | 1.43d | 0.024 | <.0001 |

| 24 | 1.75d | 1.88c | 1.91c | 2.45a | 2.26b | 0.038 | <.0001 |

| 48 | 7.76a | 6.09b | 7.97a | 7.55a | 7.71a | 0.150 | <.0001 |

| 72 | 14.87a | 13.91a | 9.50c | 11.29b | 14.95a | 0.415 | <.0001 |

| Incubation times (h) | Treatments1 | SEM2 | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | |||

| TGP (mL/g DM) | |||||||

| 3 | 19.14b | 18.95b | 19.27b | 19.52b | 20.22a | 0.204 | 0.0109 |

| 6 | 37.86b | 40.06a | 37.50bc | 35.44d | 35.88cd | 0.565 | 0.0013 |

| 9 | 46.57c | 50.88a | 48.92ab | 47.04bc | 50.29a | 0.674 | 0.0036 |

| 12 | 74.57a | 75.34a | 76.01a | 71.56b | 68.88b | 0.954 | 0.0017 |

| 24 | 113.33a | 113.53a | 108.38b | 107.88b | 108.82b | 0.646 | 0.0001 |

| 48 | 138.27ab | 140.32a | 137.17b | 136.30b | 136.10b | 0.761 | 0.0162 |

| 72 | 148.95a | 149.58a | 147.86ab | 146.29b | 148.05ab | 0.646 | 0.041 |

| CH4 (mL/g DMD) | |||||||

| 3 | 2.48b | 1.97c | 2.44b | 2.13bc | 3.34a | 0.141 | 0.0004 |

| 6 | 6.99b | 7.24b | 7.15b | 5.52c | 8.84a | 0.168 | <.0001 |

| 9 | 7.53d | 8.54b | 8.09c | 7.42d | 9.13a | 0.090 | <.0001 |

| 12 | 14.33b | 14.93b | 13.42c | 14.69b | 16.28a | 0.277 | 0.0004 |

| 24 | 36.09b | 35.11b | 33.05c | 32.10c | 38.63a | 0.495 | <.0001 |

| 48 | 55.84a | 54.11ab | 54.69ab | 52.70b | 55.63a | 0.720 | 0.0659 |

| 72 | 63.86a | 65.09a | 60.46bc | 59.23c | 62.67ab | 0.945 | 0.0077 |

| Incubation times (h) | Treatment1 | SEM2 | p-value | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | |||||||||

| Total VFA (mM) | |||||||||||||

| 0 | 20.52a | 20.86a | 20.29ab | 19.46b | 20.67a | 0.270 | 0.0336 | ||||||

| 3 | 34.08a | 32.37b | 32.14b | 31.85b | 33.92a | 0.455 | 0.0147 | ||||||

| 6 | 40.88c | 46.44ab | 42.35bc | 42.34bc | 50.35a | 1.343 | 0.0031 | ||||||

| 9 | 46.67c | 51.39ab | 52.38a | 47.79bc | 52.68a | 1.346 | 0.0293 | ||||||

| 12 | 63.47a | 56.75b | 59.33ab | 62.20a | 62.32a | 1.336 | 0.0301 | ||||||

| 24 | 88.52b | 85.60b | 98.28a | 86.66b | 82.66b | 3.075 | 0.0413 | ||||||

| 48 | 81.20c | 78.77c | 85.72b | 78.86c | 91.35a | 1.003 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 72 | 102.91b | 100.86b | 104.04ab | 100.17b | 109.05a | 1.776 | 0.0364 | ||||||

| Acetate (%) | |||||||||||||

| 0 | 59.50a | 59.39a | 59.38a | 59.31a | 58.69b | 0.126 | 0.0076 | ||||||

| 3 | 58.89d | 58.93d | 59.23c | 59.66b | 60.04a | 0.096 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 6 | 57.13ab | 56.65ab | 57.72a | 57.62a | 56.37b | 0.346 | 0.0786 | ||||||

| 9 | 56.50c | 57.68bc | 59.27ab | 59.41a | 58.35ab | 0.540 | 0.0182 | ||||||

| 12 | 58.04c | 59.05a | 59.12a | 58.71ab | 58.46bc | 0.153 | 0.0029 | ||||||

| 24 | 58.53a | 58.33a | 58.25ab | 57.40c | 57.52bc | 0.240 | 0.024 | ||||||

| 48 | 55.61bc | 56.26a | 55.98ab | 55.82abc | 55.45c | 0.165 | 0.0436 | ||||||

| 72 | 54.41a | 54.18ab | 53.90b | 52.58c | 52.30c | 0.154 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Propionate (%) | |||||||||||||

| 0 | 15.93b | 16.30a' | 16.00b | 15.86b | 16.19a | 0.060 | 0.002 | ||||||

| 3 | 20.31a | 19.74b | 19.54b | 19.40b | 19.62b | 0.125 | 0.004 | ||||||

| 6 | 23.60b | 24.36ab | 23.57b | 23.78b | 25.14a | 0.291 | 0.0149 | ||||||

| 9 | 24.73ab | 24.83ab | 24.40bc | 24.25c | 25.13a | 0.138 | 0.008 | ||||||

| 12 | 25.39a | 24.25c | 24.51bc | 25.08ab | 25.06ab | 0.233 | 0.035 | ||||||

| 24 | 25.76c | 25.62c | 26.36b | 27.21a | 27.51a | 0.168 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 48 | 27.75b | 26.85c | 27.90b | 27.73b | 29.54a | 0.227 | 0.0001 | ||||||

| 72 | 31.65b | 32.02b | 32.34b | 32.52ab | 33.46a | 0.326 | 0.027 | ||||||

| Iso-butyrate (%) | |||||||||||||

| 0 | 5.13b | 5.15b | 5.11b | 5.29a | 5.17b | 0.027 | 0.0057 | ||||||

| 3 | 3.33bc | 3.45ab | 3.46a | 3.47a | 3.29c | 0.041 | 0.0283 | ||||||

| 6 | 2.86a | 2.59b | 2.76ab | 2.75ab | 2.38c | 0.058 | 0.0012 | ||||||

| 9 | 2.57a | 2.32b | 2.27b | 2.35b | 2.27b | 0.058 | 0.0225 | ||||||

| 12 | 1.98b | 2.15a | 2.03b | 2.01b | 2.04b | 0.027 | 0.0134 | ||||||

| 24 | 1.55c | 1.67a | 1.46d | 1.61b | 1.61b | 0.013 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 48 | 1.87a | 1.92a | 1.80b | 1.92a | 1.67c | 0.023 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 72 | 1.62ab | 1.65a | 1.62ab | 1.68a | 1.57b | 0.019 | 0.0278 | ||||||

| Butyrate (%) | |||||||||||||

| 0 | 9.97bc | 10.34ab | 9.59c | 10.14b | 10.65a | 0.147 | 0.0051 | ||||||

| 3 | 11.07a | 11.07a | 11.03ab | 10.87bc | 10.84c | 0.058 | 0.0421 | ||||||

| 6 | 10.73ab | 10.58ab | 10.47b | 10.40b | 10.98a | 0.146 | 0.1074 | ||||||

| 9 | 10.97a | 10.22ab | 9.56b | 9.28b | 9.69b | 0.305 | 0.0209 | ||||||

| 12 | 10.22a | 9.96c | 9.78d | 9.78d | 10.09b | 0.027 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 24 | 10.26a | 10.21a | 10.01b | 9.90c | 9.69d | 0.030 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 48 | 9.81a | 9.93a | 9.73a | 9.39b | 8.94c | 0.066 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 72 | 8.04a | 7.89b | 7.49d | 7.58c | 7.59c | 0.020 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Isovalerate (%) | |||||||||||||

| 0 | 5.06c | 5.13bc | 5.05c | 5.22a | 5.17ab | 0.030 | 0.0092 | ||||||

| 3 | 3.55c | 3.72ab | 3.76a | 3.68b | 3.55c | 0.016 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 6 | 3.15a | 2.95c | 3.06b | 3.08ab | 2.84d | 0.026 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 9 | 2.92a | 2.61b | 2.54b | 2.57b | 2.51b | 0.085 | 0.0397 | ||||||

| 12 | 2.36bc | 2.46a | 2.35c | 2.29d | 2.39d | 0.011 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 24 | 1.98b | 2.07a | 1.90c | 2.01b | 2.01b | 0.013 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 48 | 2.63c | 2.71a | 2.48d | 2.67b | 2.32e | 0.012 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 72 | 2.36c | 2.36c | 2.39b | 2.42a | 2.32d | 0.007 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Valerate (%) | |||||||||||||

| 0 | 3.99d | 4.03c | 4.01cd | 4.16a | 4.07b | 0.009 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 3 | 2.71c | 2.85ab | 2.89a | 2.84b | 2.71c | 0.014 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 6 | 2.48a | 2.35b | 2.43a | 2.44a | 2.06c | 0.018 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 9 | 1.88b | 2.11a | 2.07a | 2.11a | 2.05ab | 0.056 | 0.0754 | ||||||

| 12 | 2.00d | 2.23a | 2.07c | 2.00d | 2.11b | 0.011 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 24 | 1.79d | 2.00a | 1.87c | 1.92b | 2.03a | 0.013 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 48 | 2.30c | 2.49a | 2.35b | 2.49a | 2.11d | 0.006 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 72 | 2.07c | 2.08c | 2.10c | 2.57a | 2.26b | 0.030 | <.0001 | ||||||

| A/P3 ratio | |||||||||||||

| 0 | 3.76a | 3.64c | 3.71ab | 3.71ab | 3.69b | 0.017 | 0.0064 | ||||||

| 3 | 2.90e | 2.99d | 3.03c | 3.12a | 3.06b | 0.010 | <.0001 | ||||||

| 6 | 2.42ab | 2.36b | 2.45a | 2.42ab | 2.47a | 0.025 | 0.0752 | ||||||

| 9 | 2.29b | 2.31b | 2.39ab | 2.42ab | 2.79a | 0.129 | 0.1094 | ||||||

| 12 | 2.31c | 2.44a | 2.42ab | 2.31c | 2.36bc | 0.021 | 0.0036 | ||||||

| 24 | 2.27a | 2.26a | 2.21a | 2.11b | 2.08b | 0.022 | 0.0002 | ||||||

| 48 | 2.00b | 2.07a | 2.01ab | 2.01ab | 1.87c | 0.020 | 0.0006 | ||||||

| 72 | 1.72a | 1.69a | 1.66a | 1.65a | 1.55b | 0.028 | 0.0169 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).