Submitted:

09 September 2024

Posted:

09 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Turmeric Starch and Experimental Diet

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Cecal Organic Acid Analysis

2.4. Analysis of Cecal Mucin Content

2.5. Analysis of Cecal Immunoglobulin A (IgA) Content

2.6. Analysis of Cecal Ammonia-Nitrogen Content

2.7. Fecal Starch Content

2.8. Cecal Bacterial DNA Extraction, Next-Generation Sequencing, and Analysis of Microbiota

2.9. Analysis of Alkaline Phosphatase Activity

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Zoometric Parameters

3.2. Cecal Parameters in Rats

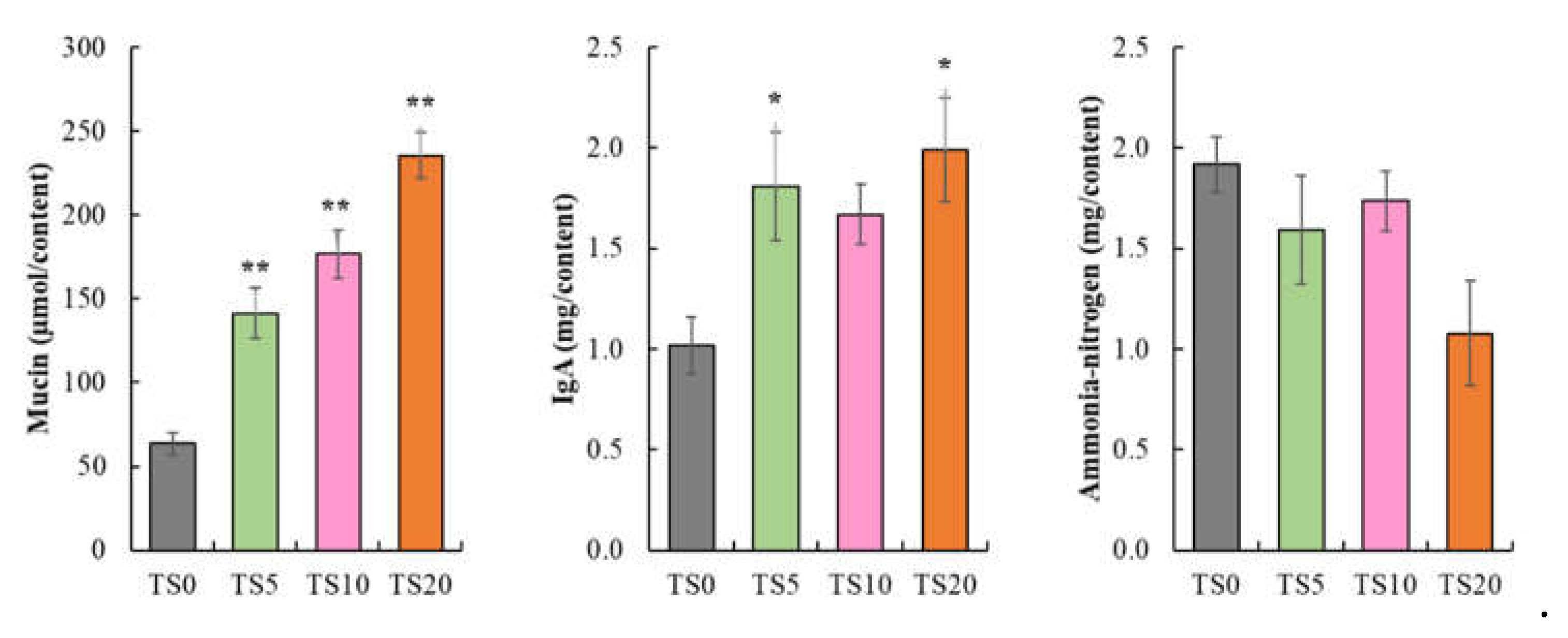

3.3. Cecal Mucin, IgA, and Ammonia Nitrogen

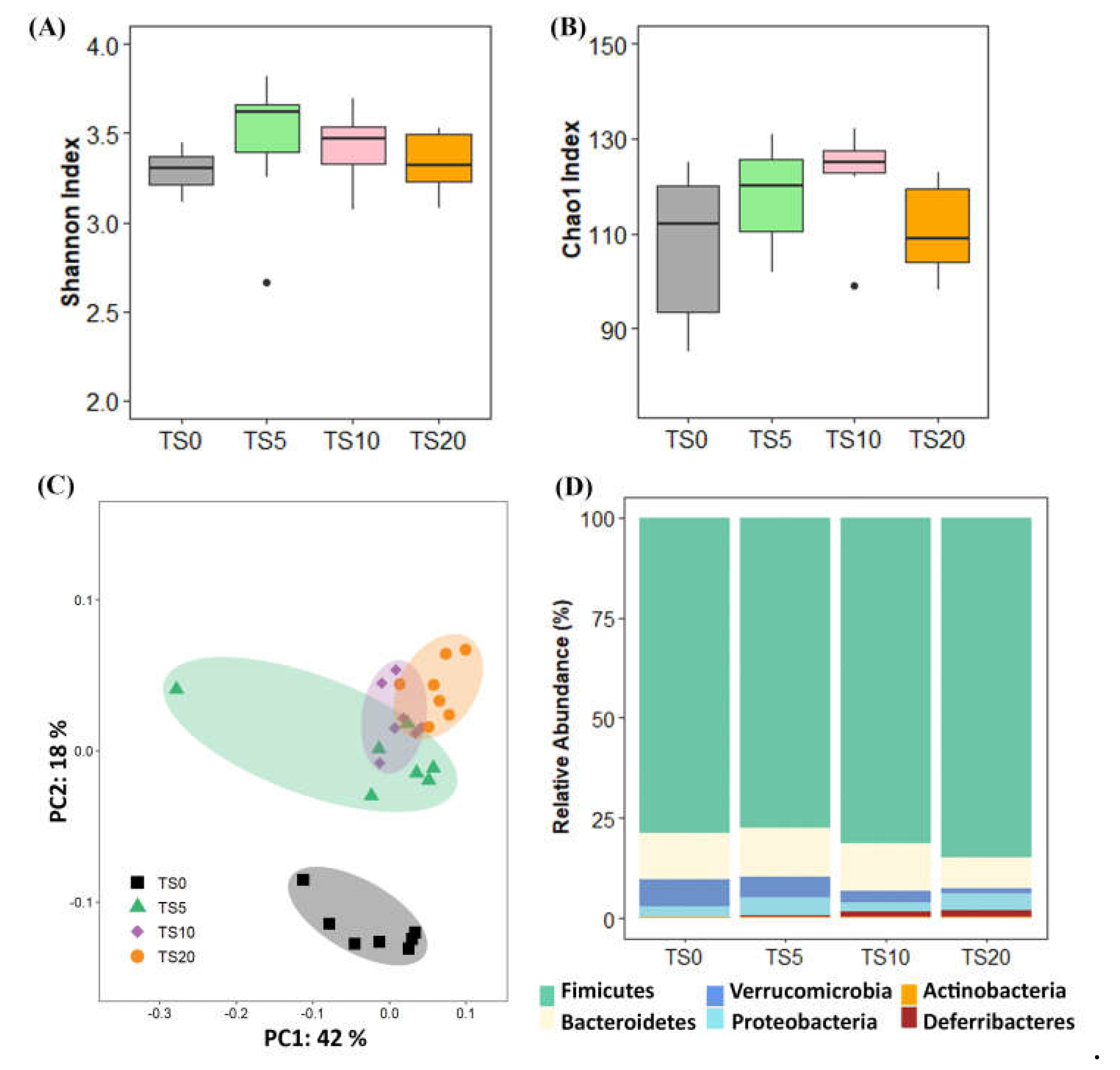

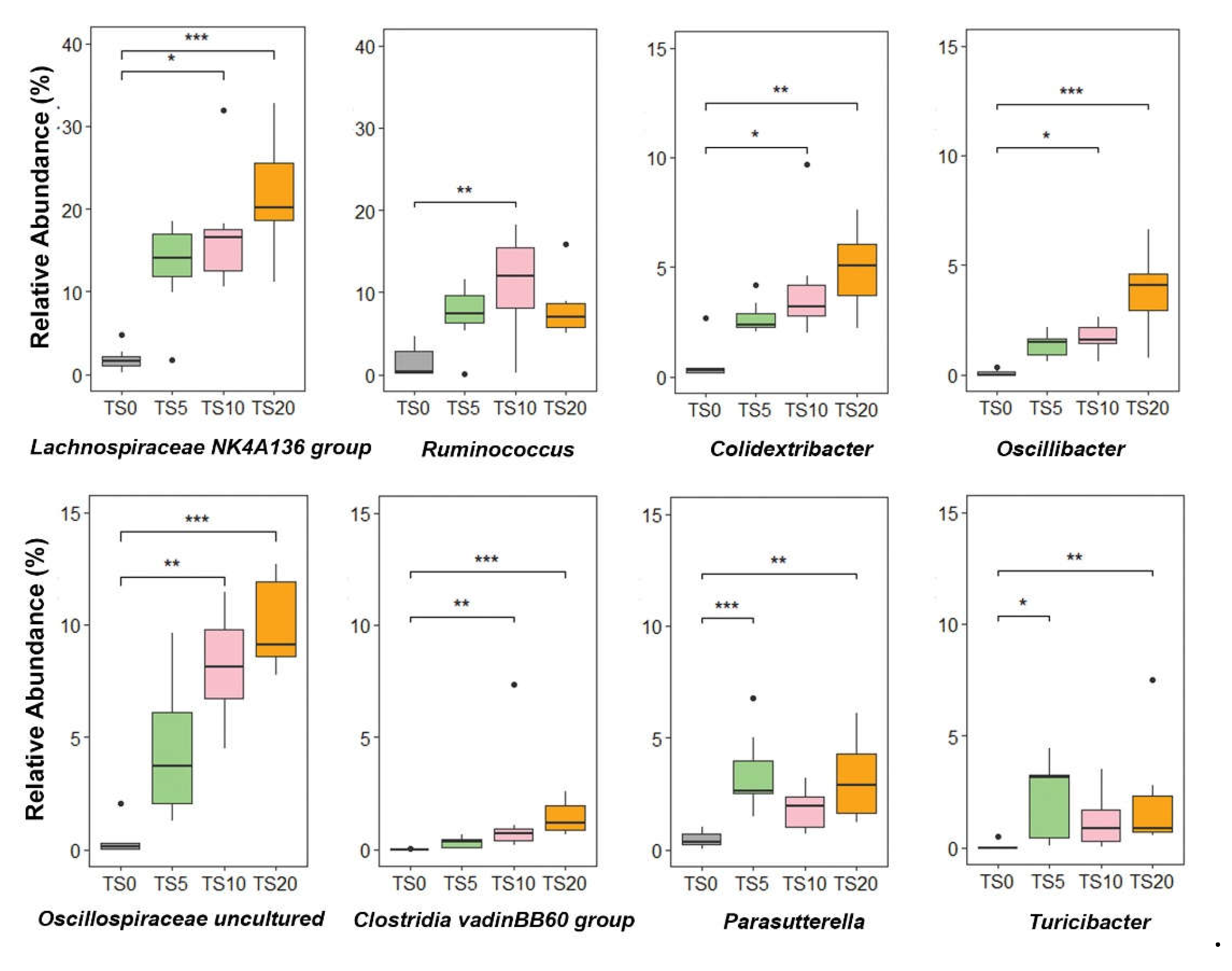

3.4. Microbial Diversity and Abundance

3.5. Intestinal Alkaline Phosphatase Activity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kocaadam, B.; Şanlier, N. Curcumin, an active component of turmeric (Curcuma longa), and its effects on health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 2889–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.H.; Kim, A.Y.; Pyun, C.W.; Fukushima, M.; Han, K.H. Turmeric (Curcuma longa) whole powder reduces accumulation of visceral fat mass and increases hepatic oxidative stress in rats fed a high-fat diet. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2014, 23, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.H.; Lee, C.H.; Kinoshita, M.; Oh, C.H.; Shimada, K.; Fukushima, M. Spent turmeric reduces fat mass in rats fed a high-fat diet. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 1814–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, P.V.; Vo, T.N.D. Structure, physicochemical characteristics, and functional properties of starches isolated from yellow (Curcuma longa) and black (Curcuma caesia) turmeric rhizomes. Starch/Stärke 2016, 69, 1600285. [CrossRef]

- Han, K.H.; Jibiki, T.; Fukushima, M. Effect of hydrothermal treatment of depigmented turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) on cecal fermentation in rats. Starch/Stärke 2020 72, 1900221. [CrossRef]

- Noda, T.; Takigawa, S.; Matsuura-Endo, C.; Suzuki, T.; Hashimoto, N.; Kottearachchi, N.S.; Yamauchi, H.; Zaidul, I.S.M. Factors affecting the digestibility of raw and gelatinized potato starches. Food Chem. 2008, 110, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makki, K.; Deehan, E.C.; Walter, J.; Bäckhed, F. The impact of dietary fiber on gut microbiota in host health and disease. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, Y.; Katayama, T. Consumption of non-digestible oligosaccharides elevates colonic alkaline phosphatase activity by up-regulating the expression of IAP-I, with increased mucins and microbial fermentation in rats fed a high-fat diet. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 121, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, M.T.; Kabisch, S.; Pfeiffer, H.F.A.; Weickert, O.M. The health benefits of dietary fibre. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.H.; Azuma, S.; Fukushima, M. In vitro fermentation of spent turmeric powder with a mixed culture of pig fecal bacteria. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 2446–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelpolage, S.; Nakata, K.; Shinbayashi, Y.; Murayama, D.; Tani, M.; Yamauchi, H.; Koaze, H. Comparison of pasting and thermal properties of starches isolated from four processing type potato varieties cultivated in two locations in Hokkaido. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2016, 22, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranhotra, G.S.; Gelroth, J.A.; Glaser, B.K. Energy value of resistant starch. J. Food Sci. 1996, 61, 453–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilua, A.; Han, K.H.; Fukushima, M. Effect of polyphenols isolated from purple sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas cv. Ayamurasaki) on the microbiota and the biomarker of colonic fermentation in rats fed with cellulose or inulin. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 10182–10192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelpolage, S.W.; Goto, Y.; Nagata, R.; Fukuma, N.; Furuta, T.; Mizu, M.; Han, K.H.; Fukushima, M. Colonic fermentation of water soluble fiber fraction extracted from sugarcane (Sacchurum officinarum L.) bagasse in murine models. Food Chem. 2019, 292, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovee-Oudenhoven, I.M.; Termont, D.S.; Heidt, P.J.; Van, D.R. Increasing the intestinal resistance of rats to the invasive pathogen Salmonella enteritidis: additive effects of dietary lactulose and calcium. Gut 1997, 40, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, R.S.; Wetmore, R.F. Fluorometric assay of O-linked glycoproteins by reaction with 2-cyanoacetamide. Anal. Biochem. 1987, 163, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Kuczynski, J.; Stombaugh, J.; Bittinger, K.; Bushman, F.D.; Costello, E.K.; Fierer, N.; Pena, A.G.; Goodrich, J.K.; Gordon, J.I.; et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, Y.; Katayama, T. The effects of different high-fat (lard, soybean oil, corn oil or olive oil) diets supplemented with fructo-oligosaccharides on colonic alkaline phosphatase activity in rats. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 60, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgings, A.J. Resistant starch and energy balance: impact on weight loss and maintenance. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 54, 1158–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harazaki, T.; Inoue, S.; Imai, C.; Mochizuki, K.; Goda, T. Resistant starch improves insulin resistance and reduces adipose tissue weight and CD11c expression in rat OLETF adipose tissue. Nutrition 2014, 30, 590–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishida, T.; Nogami, H.; Himeno, S.; Ebihara, K. Heat moisture treatment of high amylose cornstarch increases its resistant starch content but not its physiologic effects in rats. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 2716–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, K.S.; Hartigh, L.J.D. Gut microbial-derived short chain fatty acids: impact on adipose tissue physiology. Nutrients 2023, 15, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, G.; Sleeth, M.L.; Sahuri-Arisoylu, M.; Lizarbe, B.; Cerdan, S.; Brody, L.; Anastasovska, J.; Ghourab, S.; Hankir, M.; Zhang, S.; et al. The short-chain fatty acid acetate reduces appetite via a central homeostatic mechanism. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.; Vadder, D.F.; Datchary, K.P.; Backhed, F. From dietary fiber to host physiology: short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, S.; Macfarlane, T.G. Regulation of short-chain fatty acid production. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2003, 62, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firrman, J.; Liu, L.; Mahalak, K.; Tanes, C.; Bittinger, K.; Tu, V.; Bobokalonov, J.; Mattei, L.; Zhang, H.; Abbeele, V.P. The impact of environmental pH on the gut microbiota community structure and short chain fatty acid production. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2022, 98, fiac038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carboni, A.D.; Weisstaub, A.; Ferrero, C.; Zuleta, A.; Puppo, M.C. Impact of lentil-wheat bread on calcium metabolism, cecal and serum parameters in growing Wistar rats. Food Biosci. 2022, 48, 101805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malairaj, S.; Veeraperumal, S.; Yao, W.; Subramanian, M.; Tan, K.; Zhong, S.; Cheong, K.L. Porphyran from Porphyra haitanensis enhances intestinal barrier function and regulates gut microbiota composition. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragavan, M.L.; Hemalatha, S. The functional roles of short chain fatty acids as postbiotics in human gut: future perspectives. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 33, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haroun, E.; Kumar, P.A.; Saba, L.; Kassab, J.; Ghimire, K.; Dutta, D.; Lim, S.H. Intestinal barrier functions in hematologic and oncologic diseases. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, A.; Vogelzang, A.; Maruya, M.; Miyajima, M.; Murata, M.; Son, A.; Kuwahara, T.; Tsuruyama, T.; Yamada, S.; Matsuura, M.; et al. IgA regulates the composition and metabolic function of gut microbiota by promoting symbiosis between bacteria. J. Exp. Med. 2018, 215, 2019–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Sun, M.; Chen, F.; Cao, A.T.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, X.; Xiao, Y.; Yao, S.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Microbiota metabolite short-chain fatty acid acetate promotes intestinal IgA response to microbiota which is mediated by GPR43. Mucosal Immunol. 2017, 10, 946–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrong, M.O.; Vince, A. Urea and ammonia metabolism in the human large intestine. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 1984, 43, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, F.; Liu, S.; Han, S.; Chen, B. Effects of ammonia on growth performance, lipid metabolism and cecal microbial community of rabbits. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0252065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliphant, K.; Allen-Vercoe, E. Macronutrient metabolism by the human gut microbiome: major fermentation by-products and their impact on host health. Microbiome 2019, 7, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Zhang, B.; Du, A.-Q.; Zhou, Z.-Y.; Lu, D.-Z.; Zhu, Z.-H.; Ke, S.-Z.; Wang, S.-J.; Yu, Y.-L.; Chen, J.-W.; et al. Saccharina japonica fucan suppresses high fat diet-induced obesity and enriches fucoidan-degrading gut bacteria. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 290, 119411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-R.; Chou, T.-S.; Huang, C.-Y.; Hsiao, J.-K. A potential probiotic- Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group: Evidence from the restoration of the dietary pattern from a high-fat diet. Research Square 2020, (submitted).

- Lu, C.-L.; Li, H.-X.; Zhu, X.-Y.; Luo, Z.-S.; Rao, S.- Q.; Yang, Z.-Q. Regulatory effect of intracellular polysaccharides from Antrodia cinnamomea on the intestinal microbiota of mice with antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 2022, 14, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandhyala, S.M.; Talukdar, R.; Subramanyam, C.; Vuyyuru, H.; Sasikala, M.; Reddy, D.N. Role of the normal gut microbiota. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 8787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gophna, U.; Konikoff, T.; Nielsen, H.B. Oscillospira and related bacteria–From metagenomic species to metabolic features. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Cai, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Sheng, Q.; Hua, H.; Zhou, X. Role of gut microbiota in the development and treatment of colorectal cancer. Digestion 2019, 100, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Yang, Y.; Lin, X.; Chen, P.; Ye, L.; Zeng, L.; Ye, Q.; Yang, X.; Ceng, J.; Shan, J.; et al. Qiweibaizhu decoction treats diarrheal juvenile rats by modulating the gut microbiota, short-chain fatty acids, and the mucus barrier. J. Evidence-Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2021, 8873294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Ju, T.; Bhardwaj, T.; Korver, D.R.; Willing, B.P. Week-old chicks with high Bacteroides abundance have increased short-chain fatty acids and reduced markers of gut inflammation. Microbiol. Spectrum 2023, 11, e03616–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosshard, P.P.; Zbinden, R.; Altwegg, M. Turicibacter sanguinis gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel anaerobic, Gram-positive bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002, 52, 1263–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goseki-Sone, M.; Orimo, H.; Iimura, T.; Miyazaki, H.; Oda, K.; Shibata, H.; Yanagishita, M.; Takagi, Y.; Watanabe, H.; Shimada, T.; et al. Expression of the mutant (1735T-DEL) tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase gene from hypophosphatasia patients. J. Bone. Miner. Res. 1998, 13, 1827–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, G.M.; Ismael, S.; Morais, J.; Araújo, J.R.; Faria, A.; Calhau, C.; Marques, C. Intestinal alkaline phosphatase: a review of this enzyme role in the intestinal barrier function. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.S.; Wang, J.; Yannie, J.P.; Ghosh, S. Intestinal barrier dysfunction, LPS translocation, and disease development. J. Endocr. Soc. 2020, 4, bvz039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | g per 100 g |

|---|---|

| Moisture | 9.74 |

| Protein | 1.43 |

| Lipid | 0.25 |

| Ash | 1.27 |

| Total starch | 68.8 |

| Resistant starch | 61.8 |

| Digestible starch | 6.96 |

| Phosphorus (ppm) | 4972 |

| Energy (kcal per 100 g) | 233.57 |

| Ingredients (g per kg diet) | TS0 | TS5 | TS10 | TS20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casein | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 |

| L-Cystine | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Soybean oil | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| Mineral mix (AIN-93G-MX) | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 |

| Vitamin mix (AIN-93VX) | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Choline bitartrate | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Sucrose | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 3-Butylhydroquinone | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.014 |

| Cellulose | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Alpha-cornstarch | 129.5 | 129.5 | 129.5 | 129.5 |

| Cornstarch | 400 | 350 | 300 | 200 |

| Turmeric starch | 0 | 50 | 100 | 200 |

| Energy (kcal per kg diet) | 3804 | 3730 | 3657 | 3509 |

| TS0 | TS5 | TS10 | TS20 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final body weight (g) | 240 | ± | 5 | 229 | ± | 2 | 232 | ± | 3 | 233 | ± | 5 |

| Body weight gain (g/2 wk) | 58.8 | ± | 2.1 | 48.4 | ± | 1.9 | 51.9 | ± | 1.9 | 52.4 | ± | 6.6 |

| Feed intake (g/2 wk) | 202 | ± | 3 | 193 | ± | 2 | 199 | ± | 2 | 200 | ± | 4 |

| Perirenal + epididymal fat (g) | 7.82 | ± | 0.89 | 5.32 | ± | 0.25*** | 5.56 | ± | 0.23*** | 4.84 | ± | 0.24*** |

| Dry feces (g/2 d) | 2.08 | ± | 0.06 | 3.62 | ± | 0.23*** | 4.72 | ± | 0.14*** | 6.94 | ± | 0.35*** |

| Starch excretion (%) | 0.04 | ± | 0.00 | 4.28 | ± | 0.56** | 8.95 | ± | 0.23*** | 23.0 | ± | 1.4*** |

| TS0 | TS5 | TS10 | TS20 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic acid (µmol/content) | ||||||||||||

| Acetate | 258 | ± | 20 | 408 | ± | 60* | 451 | ± | 37** | 545 | ± | 27*** |

| Propionate | 35.7 | ± | 5.7 | 40.2 | ± | 5.0 | 41.5 | ± | 3.6 | 46.9 | ± | 4.1 |

| n-Butyrate | 21.3 | ± | 5.2 | 27.7 | ± | 4.4 | 28.5 | ± | 6.6 | 27.1 | ± | 5.3 |

| Total-SCFA | 315 | ± | 28 | 476 | ± | 67* | 521 | ± | 41** | 619 | ± | 32*** |

| Succinate | 25.0 | ± | 9.4 | 7.86 | ± | 2.07 | 4.67 | ± | 2.04* | 5.62 | ± | 1.84* |

| Lactate | 2.41 | ± | 1.63 | 11.8 | ± | 3.0 | 13.6 | ± | 367* | 12.9 | ± | 2.2* |

| Cecal pH | 7.77 | ± | 0.04 | 7.40 | ± | 0.09* | 7.25 | ± | 0.05*** | 7.12 | ± | 0.05*** |

| Cecal tissue (g) | 0.68 | ± | 0.01 | 0.93 | ± | 0.07** | 1.07 | ± | 0.07*** | 1.11 | ± | 0.04*** |

| Cecal digesta (g) | 2.41 | ± | 0.25 | 3.54 | ± | 0.39* | 3.70 | ± | 0.28* | 4.71 | ± | 0.22*** |

| TS0 | TS5 | TS10 | TS20 | |||||||||

| Duodenum | 301 | ± | 56 | 1168 | ± | 195* | 831 | ± | 180 | 900 | ± | 279 |

| Jejunum | 155 | ± | 14 | 119 | ± | 30 | 75.3 | ± | 28.4*** | 100 | ± | 23** |

| Ileum | 127 | ± | 15 | 76.3 | ± | 8.1* | 73.1 | ± | 12.3* | 61.7 | ± | 12.8** |

| Cecum | 37.7 | ± | 4.4 | 39.2 | ± | 4.6 | 37.1 | ± | 4.8 | 48.0 | ± | 5.6 |

| Colon | 51.3 | ± | 8.4 | 55.9 | ± | 21.9 | 51.1 | ± | 9.1 | 11.9 | ± | 3.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).