1. Introduction and Research Hypothesis

The concept of national character has long captivated psychologists (Hofstede, 1980), sociologists (Schwartz, 2009), and anthropologists (House et al., 2004). Historically, thinkers such as Montesquieu (1748/1989), Kant (1798/1978), and early 20th-century anthropologists (Kretschmer, 1925/1926) explored how collective personality traits influence societal behaviours. In contemporary psychology, data-driven frameworks like the Five-Factor Model (Big Five) (McCrae & Costa, 1987), Hofstede’s cultural dimensions (Hofstede, Hofstede, & Minkov, 2010), and Kretschmer’s typology (Kretschmer, 1925/1926) provide various perspectives for examining differences in cultural and psychological outcomes.

National character refers to the enduring traits or tendencies observed in individuals within a society. It is closely tied to temperament, shaped by inherited predispositions and cultural influences. Understanding the interplay between cultural identity and socio-psychological constructs in our increasingly globalised world is crucial for navigating intercultural interactions.

The Body Image and Schema Test (BIST) (Anzieu, 1989) evaluates individuals’ perceptions of their physical appearance and subconscious body awareness. It assesses the emotional, cognitive, and functional dimensions affected by personal and cultural factors. The central hypothesis of this study posits that the cultural dimensions of national character—particularly concerning body schema and image—correlate with Hofstede’s notions of national identity (Hofstede, 1980). Furthermore, the psychodynamic dimensions of BIST may offer greater insights into the traits outlined in both the Big Five model (McCrae & Costa, 1987) and Kretschmer’s theories (Kretschmer, 1925/1926). A more complete presentation of the BIST theoretical framework and a full description of the meaning of BIST Factors and Items is available in the repository Open Science Framework link

https://osf.io/yt8pm/?view_only=cd9392c4f9994862bf40cd10fffb9ef4.

2. Theoretical Frameworks

The psychological character, defined as the enduring patterns of thoughts, emotions, and behaviours that shape an individual’s identity, is closely linked to body image and schema. Theoretical frameworks, empirical research, and interdisciplinary studies support this relationship (Anzieu, 1989). Embodiment theory (Merleau-Ponty, 1945/1962) suggests that psychological experiences and identity are inseparable from the physical body; the body is not merely a vessel for the mind but an active participant in shaping thoughts, emotions, and behaviours.

Body image refers to how individuals perceive, feel, and think about their physical appearance. Psychological traits such as self-esteem, confidence, and self-worth significantly influence this perception. In contrast, body schema represents the unconscious, sensory-motor map of the body, which affects how one navigates and interacts with their environment. Body image and body schema are distinct yet interconnected concepts within psychology, neuroscience, and cultural studies. Understanding their differences is crucial for exploring their roles in identity, behaviour, and cross-cultural influences (Rocha, P. 2024). Body image involves conscious perceptions, thoughts, and feelings about one’s appearance, incorporating emotional, cognitive, and social dimensions shaped by personal experiences and societal norms. On the other hand, body schema relates to the unconscious, dynamic representation of the body’s position, movement, and structure, relying on sensorimotor processes influenced by proprioceptive, tactile, and visual inputs. Body image is a psychological and emotional construct, while body schema is a sensory-motor construct.

Body image is heavily influenced by cultural values and societal ideals of beauty, impacted by media, social interactions, and norms surrounding individualist societies versus collectivist cultures. Body schema is generally considered universally similar due to shared human neurobiological processes. Still, cultural variations in physical activities—such as walking barefoot in rural areas versus wearing shoes in urban settings—may subtly affect proprioceptive input without drastically altering body schema.

The Body Image and Schema Test (BIST) is an assessment tool designed to evaluate individuals’ perceptions, attitudes, and representations of their body image and body schema. The test differentiates between body image, the subjective perception and emotional attitudes individuals hold about their physical appearance, which can be influenced by psychological, social, and cultural factors, and the body schema, the unconscious, sensorimotor representation of the body used for movement and spatial orientation, rooted in neurological and proprioceptive processes. The BIST focuses on identity’s personal and embodied dimensions (Giannotta, A. P., 2022), revealing how individuals negotiate body perceptions within cultural contexts.

Grounded in psychodynamic theoretical frameworks, the BIST draws upon psychological constructs such as drive energy, self-perception, relational and bonding dynamics, body image, and embodiment. The internal organisation of the BIST includes multiple subscales (seven factors) and items (25) that have been developed to capture both explicit and implicit body-related processes. The BIST consists of 25 strings of four pictures each. The authors have selected pictures as body-dynamic symbols. A more comprehensive description of the Body Image and Schema Test is available in Open Science Framework

https://osf.io/yt8pm/?view_only=cd9392c4f9994862bf40cd10fffb9ef4.

The BIST generates data that support both individual-level diagnostics and population-level research. At the individual level, it can identify maladaptive body perceptions or attitudes that may underlie disorders such as body dysmorphic disorder, eating disorders, or anxiety. At the research level, it facilitates studies on cultural, developmental, or clinical variations in body image. Data analysis typically includes descriptive statistics, factor analysis, and correlation with external variables, allowing integration with broader psychological constructs and interventions.

In psycho-social research, Hofstede identified six dimensions to explain cultural variations (Hofstede, Hofstede, & Minkov, 2010): Power Distance (PDI), which refers to the acceptance of unequal power structures; Individualism vs. Collectivism (IDV), the degree of interdependence among members of society; Masculinity vs. Femininity (MAS), the preference for competitiveness compared to care and quality of life; Uncertainty Avoidance (UAI), which is the tolerance for ambiguity and risk; Long-Term vs. Short-Term Orientation (LTO), focusing on future versus present rewards; and Indulgence vs. Restraint (IVR), the extent of societal permissiveness. Hofstede’s framework (Beugelsdijk, S., Kostova, T., & Roth, K., 2017) provides insights into societal values but does not account for individual dynamics. For example, Mediterranean cultures score high on Uncertainty Avoidance, which, as the research will show, has some relation to symbolic body schema constructs in the Body Image and Symbolic Theory (BIST) context. Indian cultures, characterised by a Long-Term Orientation, demonstrate disciplined body regulation, as reflected in BIST’s findings on energy constructs.

Kretschmer’s Typology (Kretschmer, 1925/1926) suggests that body constitution correlates with psychological tendencies: Asthenic (thin builds are linked to introverted, sensitive, and schizoid traits); Athletic (muscular builds are balanced yet rigid, indicating schizothymic tendencies); and Pyknic (rounded builds are sociable, emotional, and display cyclothymic traits). BIST complements this typology by identifying psychomotor and energy dynamics associated with different body types. For instance, Mediterranean cultures align with pyknic tendencies, displaying high relational energy and symbolic focus. North Africans, exhibiting assertive energy, reflect athletic traits, while the balanced energy of Indians aligns with introspective asthenic traits. However, Kretschmer’s direct connection to mental disorders is less relevant in the broader cultural framework offered by BIST.

The Big Five model (McCrae & Costa, 1987) describes stable individual traits: Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, and Openness to Experience. Extraversion relates to sociability and energy; Agreeableness is characterized by warmth and empathy; Conscientiousness involves discipline and goal orientation; Neuroticism denotes emotional instability; and Openness refers to creativity and intellectual engagement. BIST overlaps with trait theory by linking these traits to psychodynamic constructs. For instance, Extraversion in BIST can be seen in high expelling energy that aligns with sociability (e.g., observed in North Africans); Agreeableness corresponds with relational constructs reflecting warmth (e.g., seen in Latin Americans); and Neuroticism correlates with high ego sensitivity that indicates emotional reactivity (e.g., prevalent in Mediterranean cultures).

It can be noted here that BIST focuses on embodied psychodynamics, whereas Hofstede abstracts societal values. Kretschmer’s rigid typology lacks the flexibility inherent in BIST’s cultural and symbolic integration. Trait theory, too, omits cultural and symbolic dimensions, which limits its applicability in cross-cultural contexts.

Integrating BIST with the three theoretical frameworks of Hofstede (2010), Kretschmer (1926), and Trait Theory (McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr., 1987), makes it clear that BIST’s psychodynamic approach complements these theories by emphasising embodiment. The psychodynamic meaning of BIST constructs, such as the Internal Body Model and Ego Skin Factors, symbolises the interaction between the body and cultural narratives, shaping personality and national character.

For these reasons, a test like BIST, which integrates psychodynamic and bodily constructs, can bridge between Hofstede’s societal analysis, Kretschmer’s typology, and trait theory. Its emphasis on embodiment provides nuanced insights into national character and temperament, enriching cross-cultural psychological studies.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants/Sample

Table 1 presents the sample for this study. The research utilised stratified participants from four global regions: Mediterranean (n = 1164), Latin American (n = 743), North African (n = 2081), and Indian (n = 1312). This diverse sample was collected through Amazon Mechanical Turk.

3.2. Procedure

Data collection involved the Body Image Schema Test (BIST), a standardised psychometric instrument that captures self-reported perceptions of body functionality, idealisation, and coherence. The BIST consists of 25 items, each with four pictures, from which participants select the one that resonates most with them.

3.3. Objectives

The primary goal was to assess the relationship between cultural dimensions and BIST factors, while secondary objectives included identifying patterns in national character across contexts like sports and hobbies. This study hypothesises that traditional concepts of “character” and “temperament” reflect cultural values that influence body schema, exploring whether cultural pressures also affect subconscious self-representation.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

SPSS version 29 was used, with multivariate analysis of variance, assessing differences across cultural groups and significant correlations among BIST variables. Data are in Z-Point format. Chat GPT was used to help identify information within statistical tables.

4. Results

The findings are organised into two main areas: 1) differences in body schema and body image across four cultures, and 2) variations in body-related activities, such as sports, hobbies, and dance, among different nationalities.

4.1. Body Image and Schema Test Differences Across Four Main World Cultures

Statistical analyses have revealed significant body image and schemas differences across Mediterranean, Latin American, North African, and Indian cultures. Results from a multivariate test conducted in SPSS indicated significant multivariate effects among the four cultural groups, as shown by Pillai’s Trace (F = 9.628, p < 0.001). Wilks’ Lambda (F = 9.737, p < 0.001) further confirms the existence of statistically significant differences among these groups, while Hotelling’s Trace (F = 9.846, p < 0.001) reinforces the multivariate discrepancies observed.

Roy’s Largest Root (F = 17.943, p < 0.001) highlights the most substantial effects in one of the dependent variables. The differences indicated by Roy’s Largest Root about the four cultural families likely stem from one or more of the following dependent variables based on their significant univariate results:

1. Drive Energy Constructs, in particular, Item Hold (F = 31.110, p < 0.001): Cultural differences in energy retention are pronounced, with participants from Latin America emphasising retention more than participants from other regions.

2. Ego Skin Factors, particularly Item Ego Sensitivity (F = 33.509, p < 0.001): Significant differences in sensitivity to external stimuli are particularly notable among Mediterranean and North African participants.

3. Psychomotor Development, particularly Item Postural Attitude (F = 15.645, p < 0.001): Noteworthy differences in physical posture development are observed, with Indian participants displaying distinct patterns.

4. Relational Constructs, Item Fusion/Separation (F = 13.443, p < 0.001): There are substantial cultural differences in relational dynamics, particularly in separation, driven mainly by Mediterranean and North African influences.

5. Super Factors Internal Body Model (F = 25.996, p < 0.001): This variable represents significant cultural differences in perceptions of the internal body, especially between Mediterranean and North African participants.

Due to their high F-values and strong significance, these variables, particularly Ego Sensitivity and Internal Body Model, are strong candidates for driving the effects identified by Roy’s Largest Root. The Univariate Analysis of Dependent Variables finds many BIST items and factors statistically significantly different.

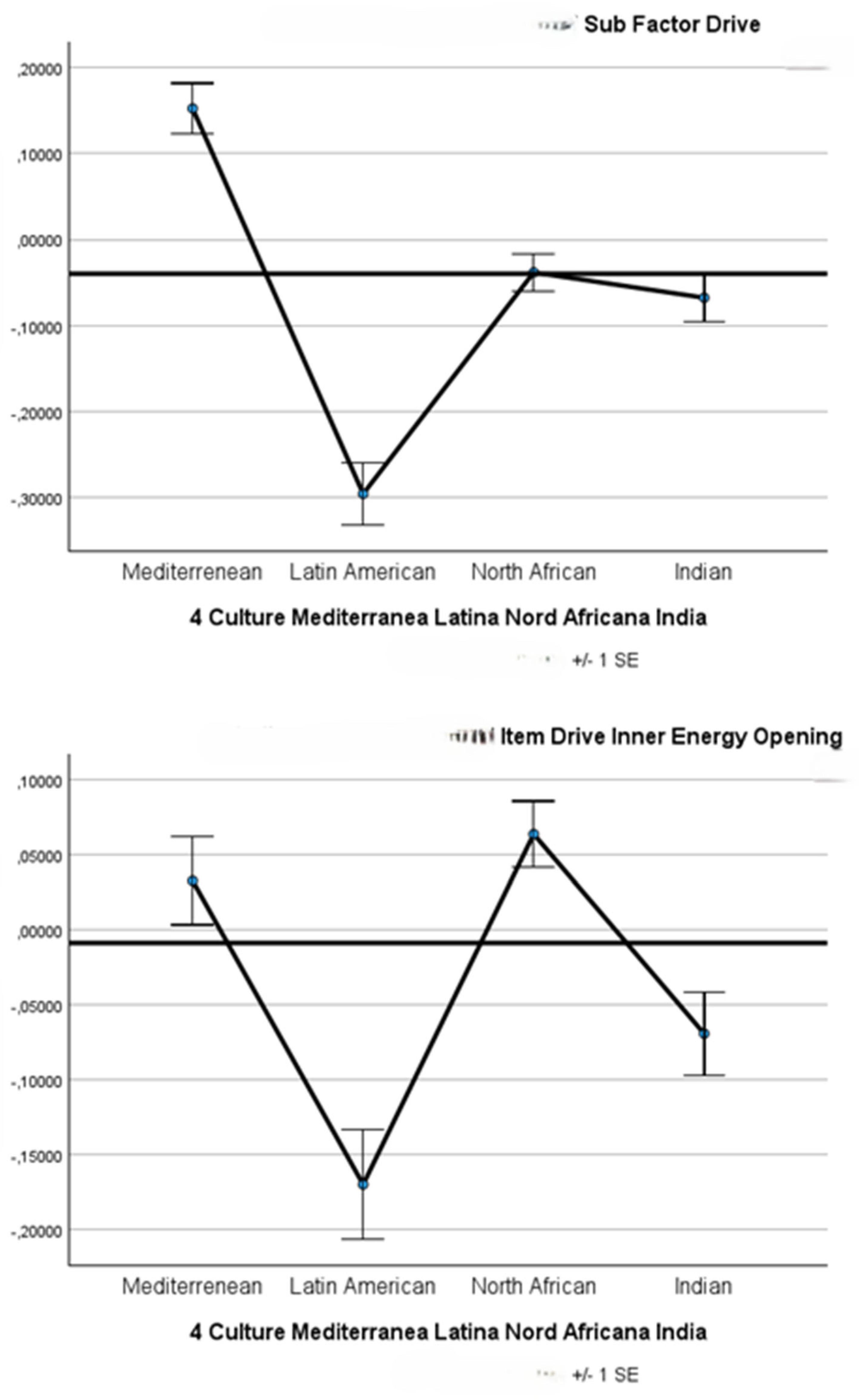

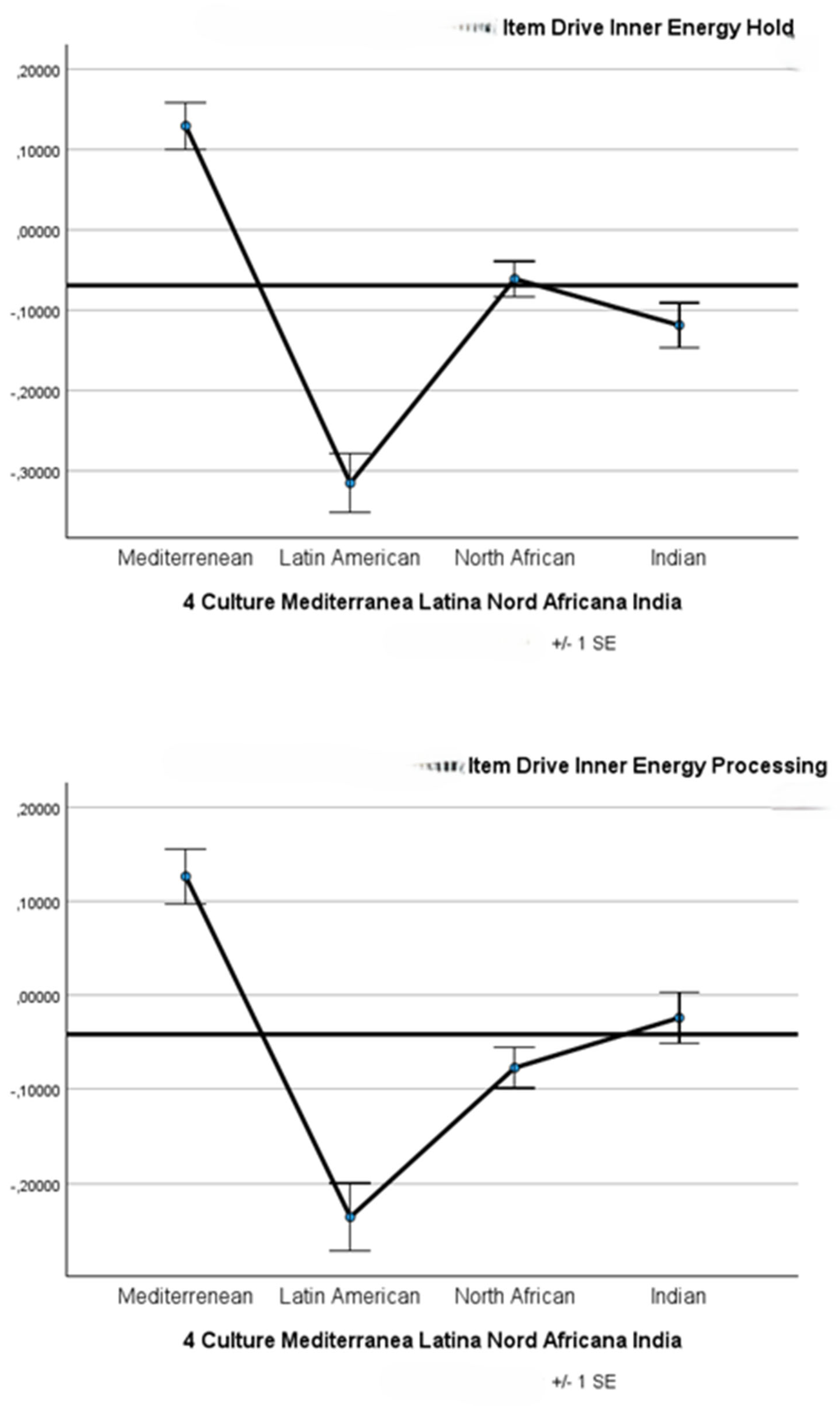

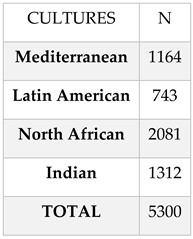

Drive Sub Factor

This factor is closely linked to “self-confidence”, reflecting an individual’s trust in their body. It also represents the ability to exchange with the external environment, similar to how we breathe air or assimilate food. The more intense this exchange with the outside world, the stronger the body’s vital energy becomes, making it more reliable. Additionally, this sub-factor extends the physical exchange to the psyche, symbolising the body’s capacity to process mental content.

Statistics and graphs indicate that Latin Americans tend to be less “impulsive” compared to those from Mediterranean cultures. This may seem counterintuitive, but in this context, the Drive Sub Factor represents the fundamental regulatory functions of the body, such as breathing, digestion, and assimilation, which are governed by the autonomic nervous system. In this framework, countries in the Mediterranean region exhibit very high “burst” responses, while Latin America appears to function more calmly within the autonomic nervous system. Indians and North Africans fall around the average in this regard.

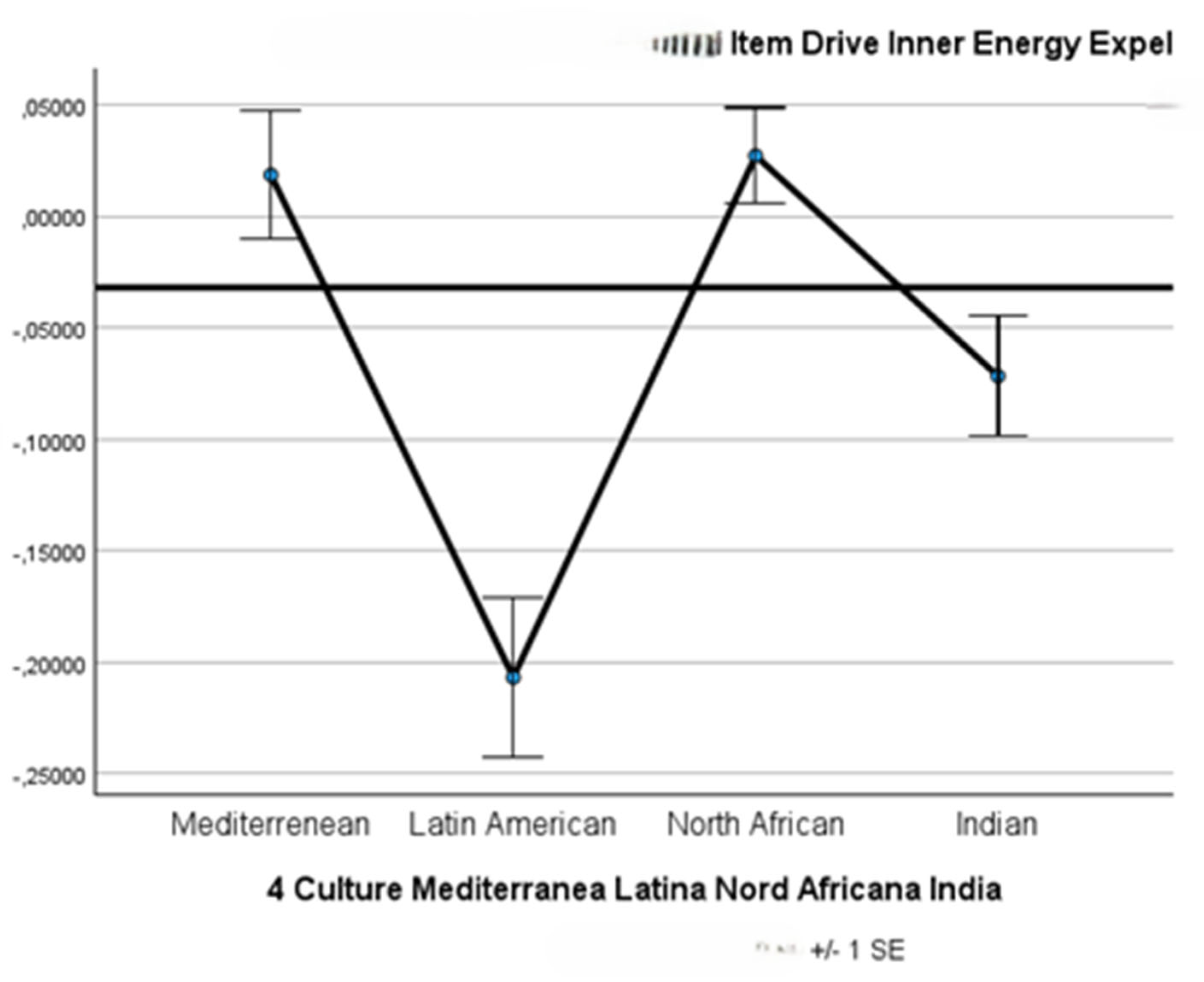

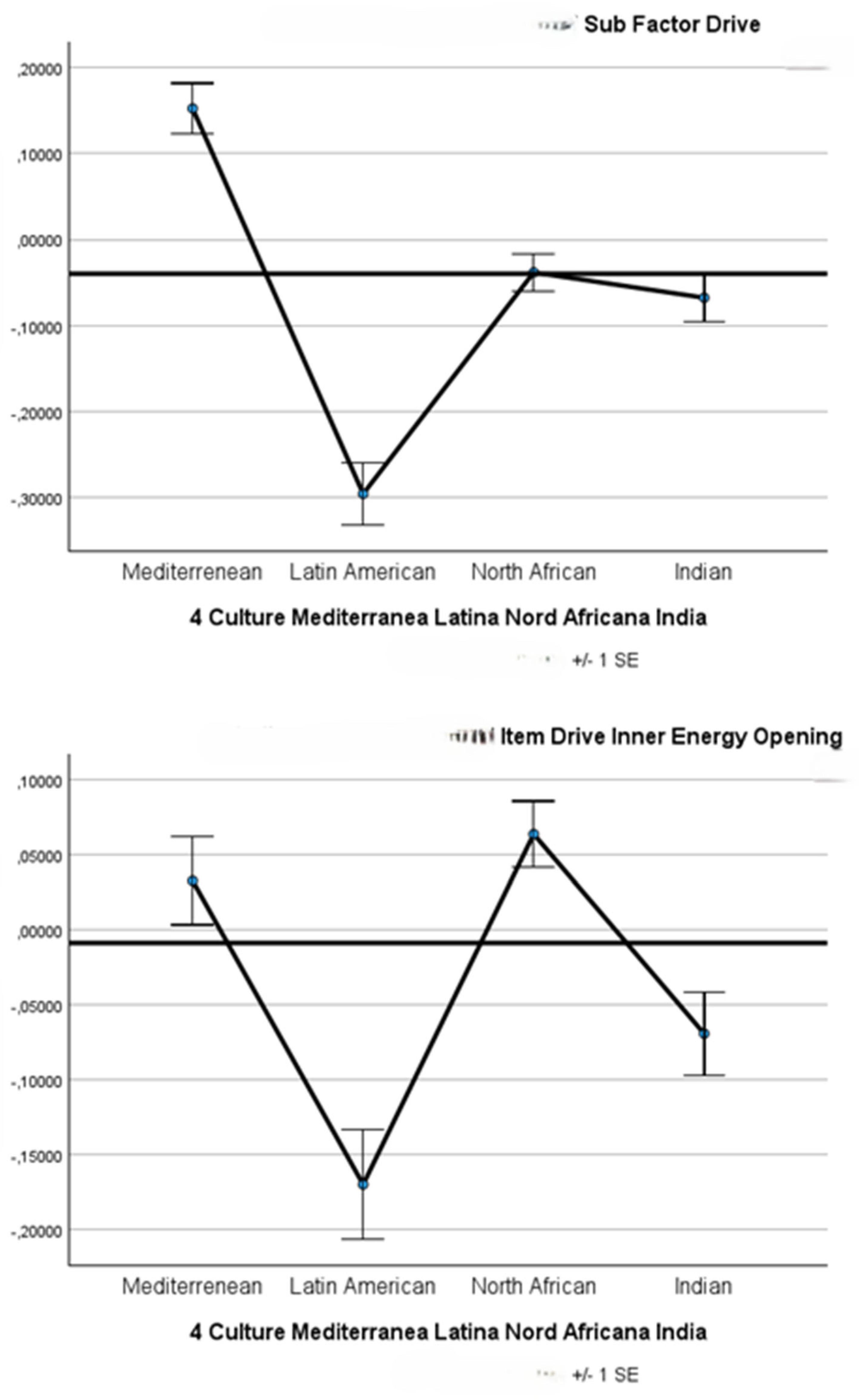

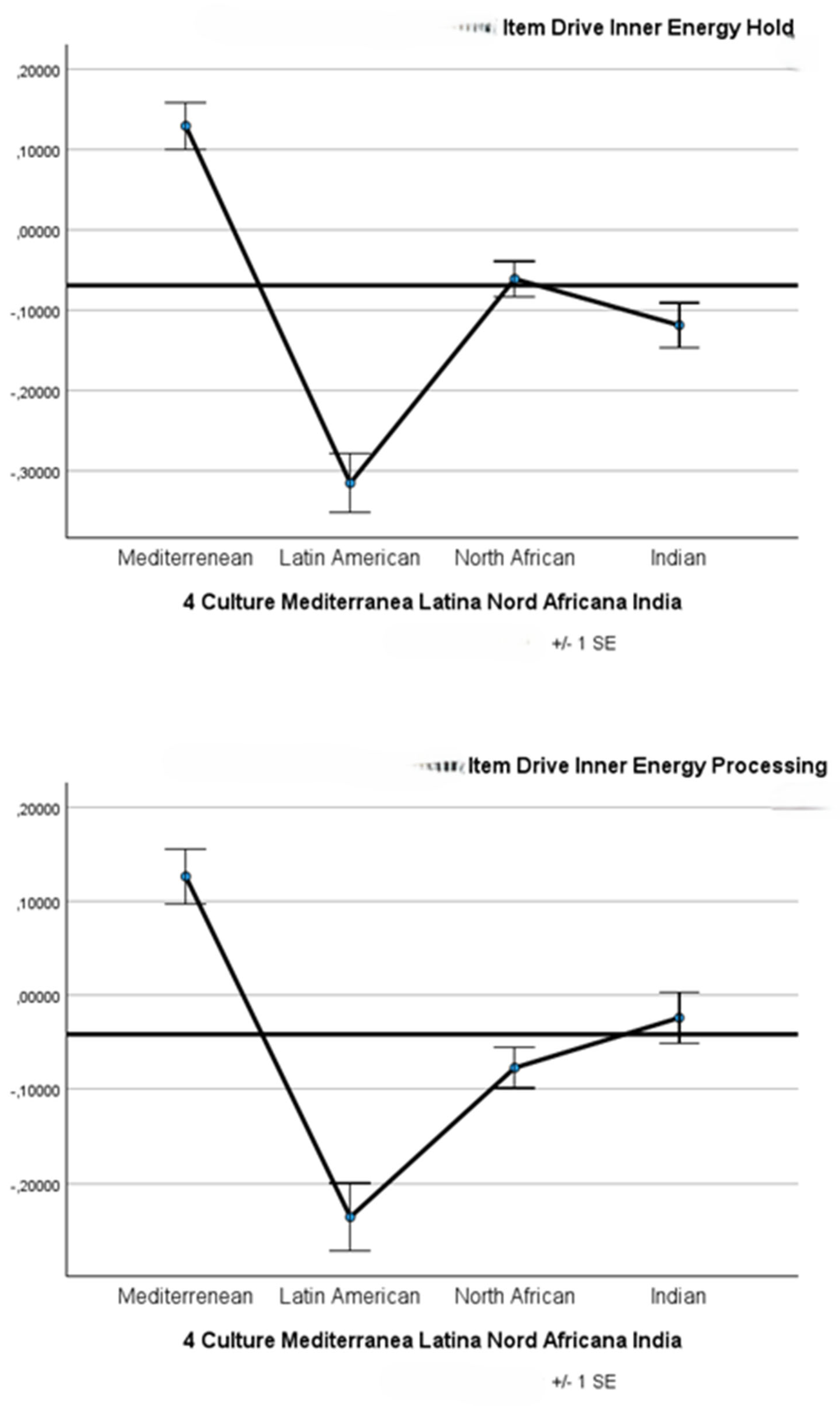

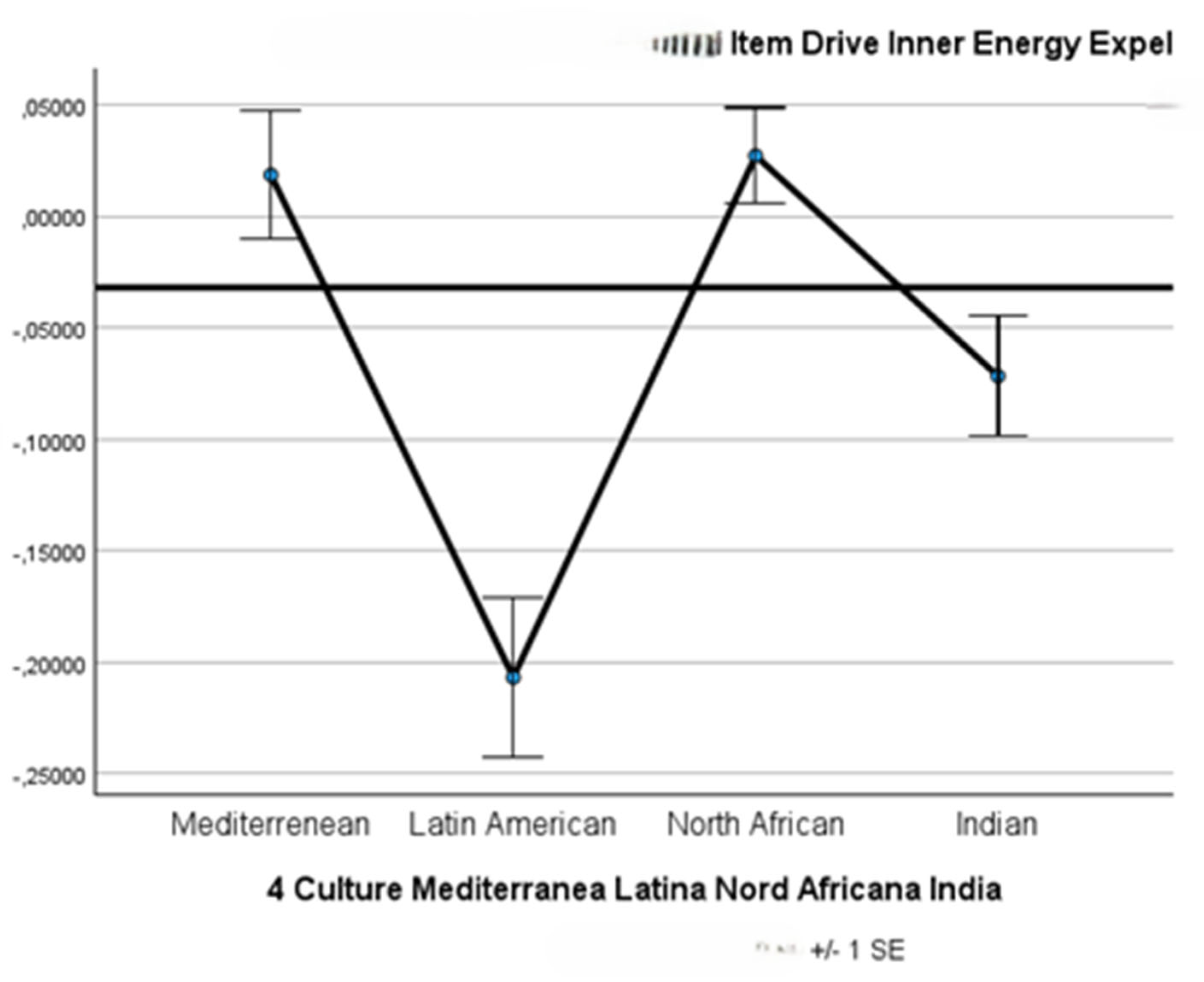

Drive Energy Constructs reveals the following items as statistically significant: Opening (F = 12.308, p = 0.000; Africans have a high ability to energetically “open”); Hold (F = 31.110, p = 0.000: Mediterranean excel in retaining energy); Processing (F = 21.852, p = 0.000; Mediterranean demonstrate significant effects on individuals’ internal energy processes, while Latin Americans show lower effects); Expel (F = 12.107, p = 0.000; Mediterranean and North Africans release energy above average, while Latin Americans are significantly below average).

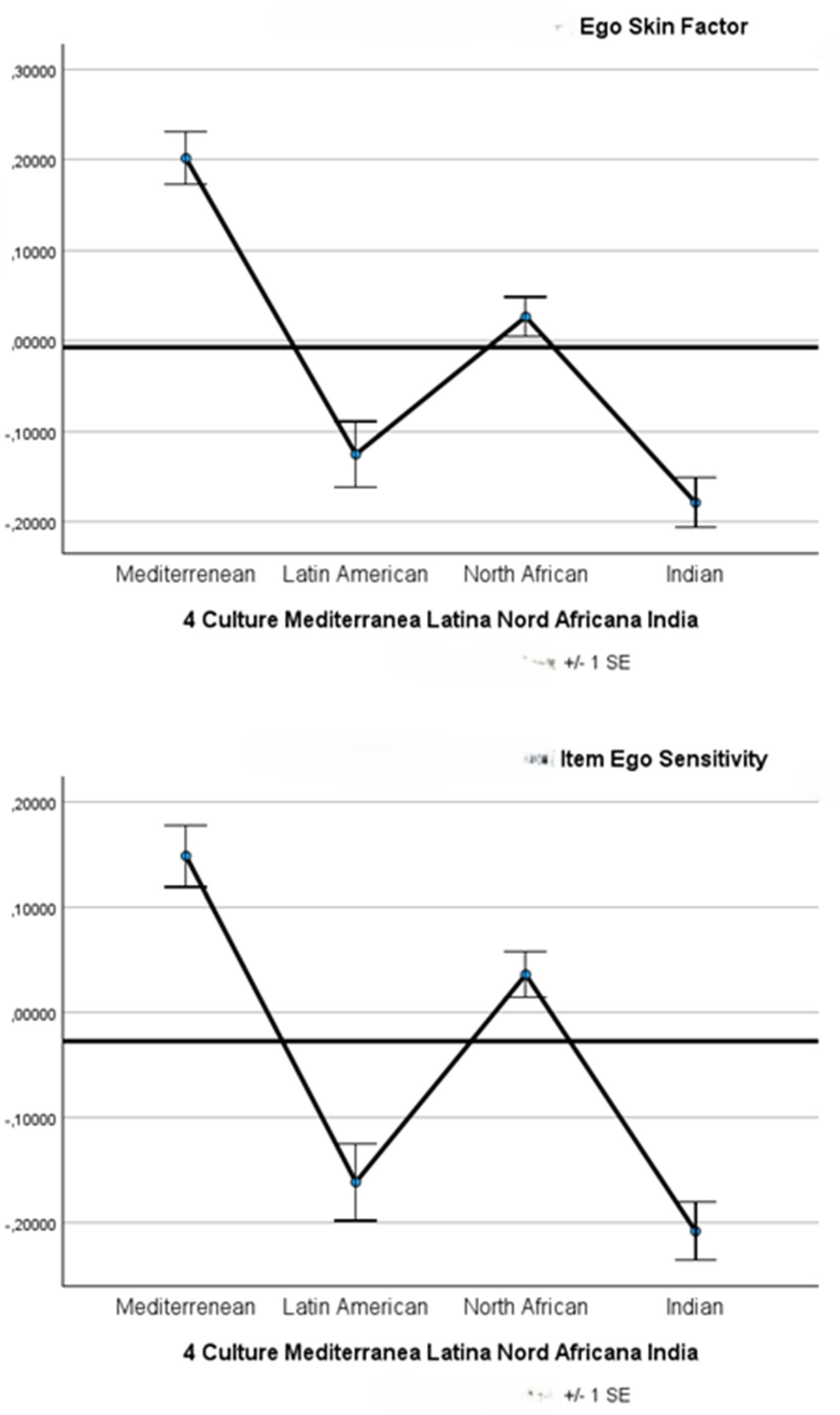

Ego Skin Factors

This factor addresses exteroceptive sensitivity, encompassing touch, epidermal sensoriality, and self-exposure as forms of self-communication. Besides its communicative value, epidermal sensitivity carries significant erotic meaning (Montemurro, B., & Hughes, E., 2024). The skin serves as an “eroteme” (Fornari, 1976) due to its reactions to emotional states—consider the phenomenon of “goosebumps.” Additionally, skin reactions can elicit excitement when observed by others. This factor symbolically interprets the Skin Ego (Anzieu, 1989) because the ego typically interfaces between the internal and external worlds, managing a controlled exchange with the latter. As an epidermal membrane, the skin also serves protective functions by establishing a boundary for the individual.

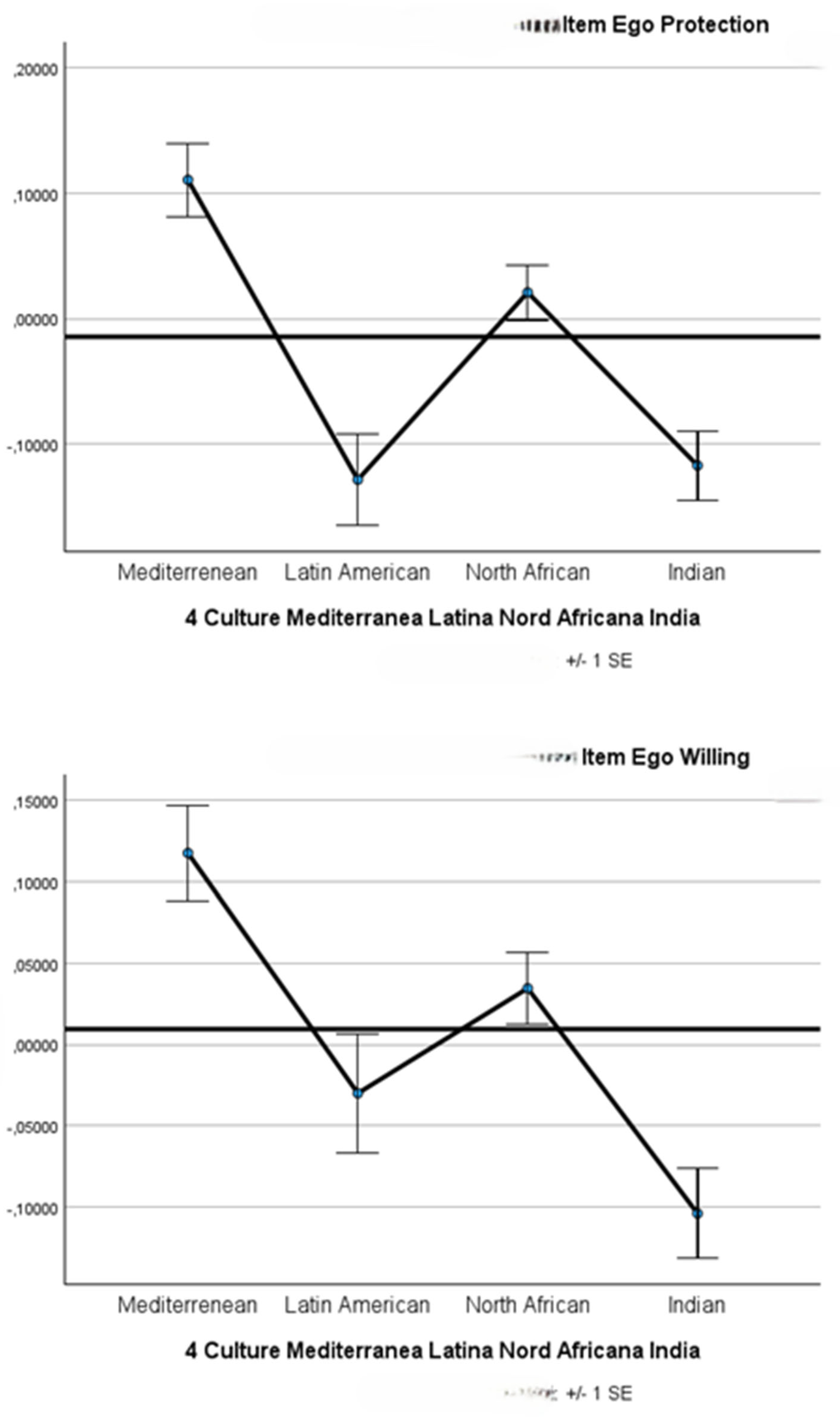

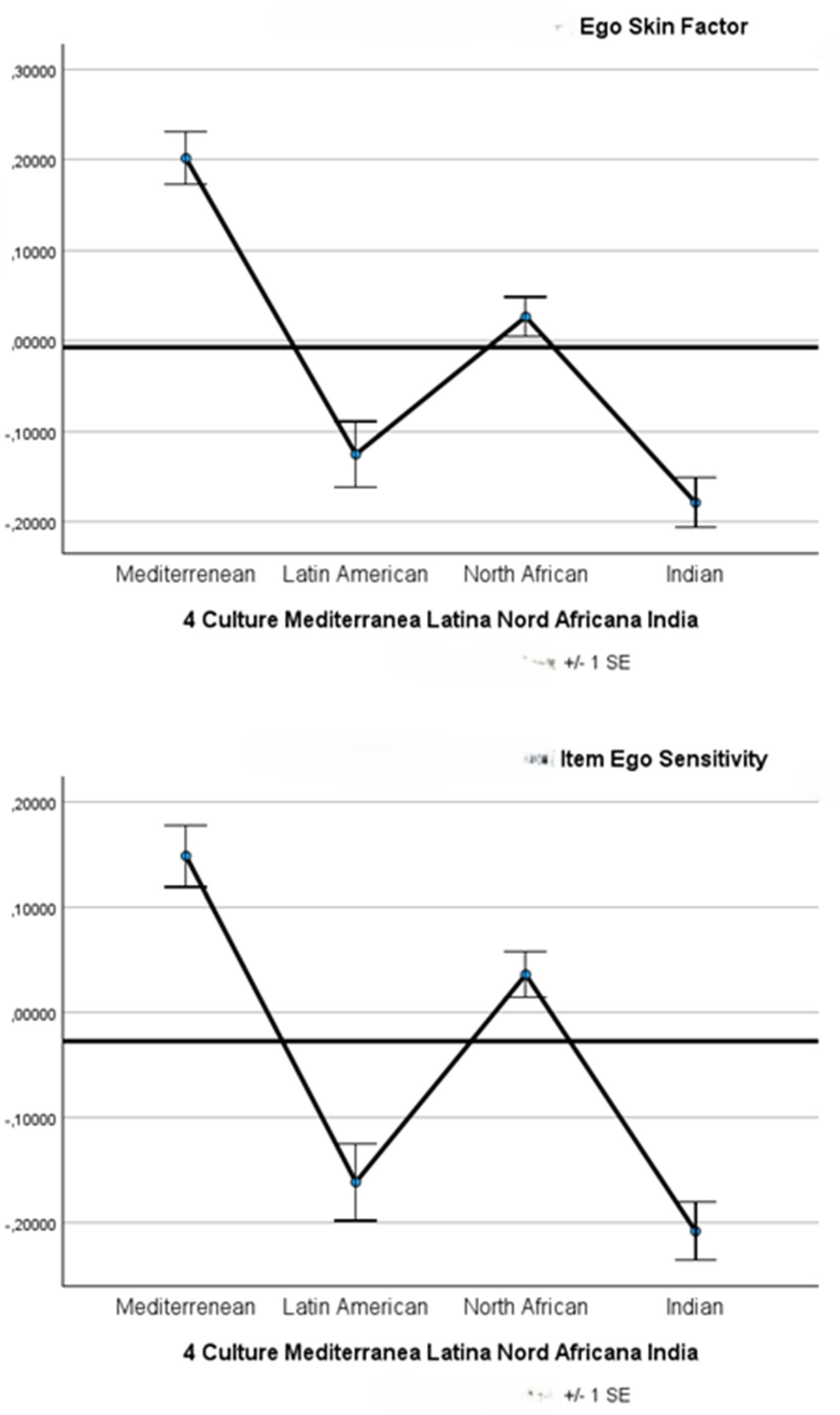

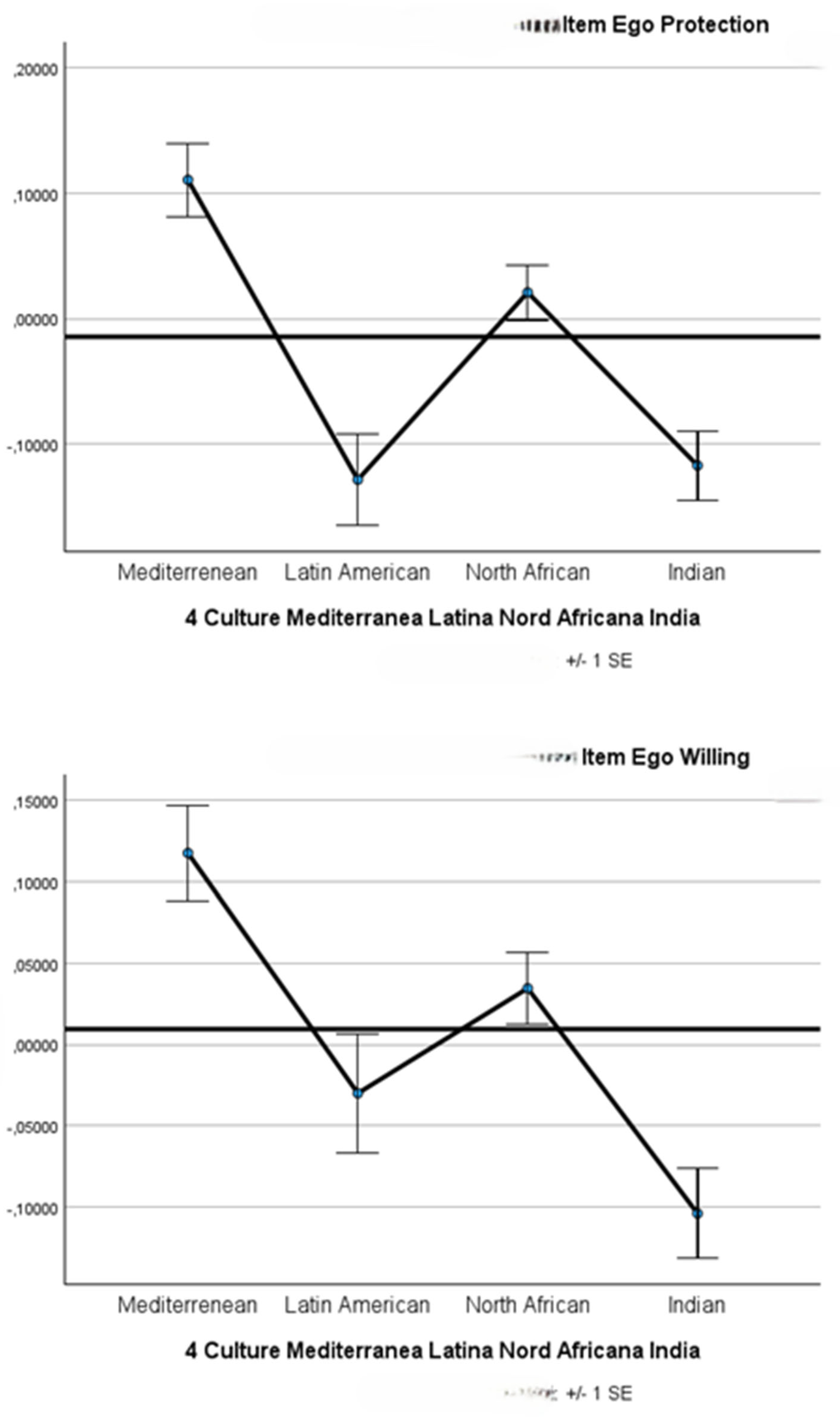

Statistical analysis reveals notable differences in the Ego Skin Factor items across four cultures. Indians tend to score lower on all three items: Ego Sensitivity (F = 33.509, p = 0.000), indicating that sensitivity to external stimuli is less pronounced among Indians and Latin Americans compared to Mediterranean and North African groups; Ego Protection (F = 14.816, p = 0.000), where again, Latin Americans and Indians exhibit more protective responses related to the ego; and Self-Willing (F = 10.951, p = 0.000). In terms of intentional actions, Indians display what could be described as a defensive ego, while those from Mediterranean cultures tend to express a more assertive ego.

The Libidinal Energy factor

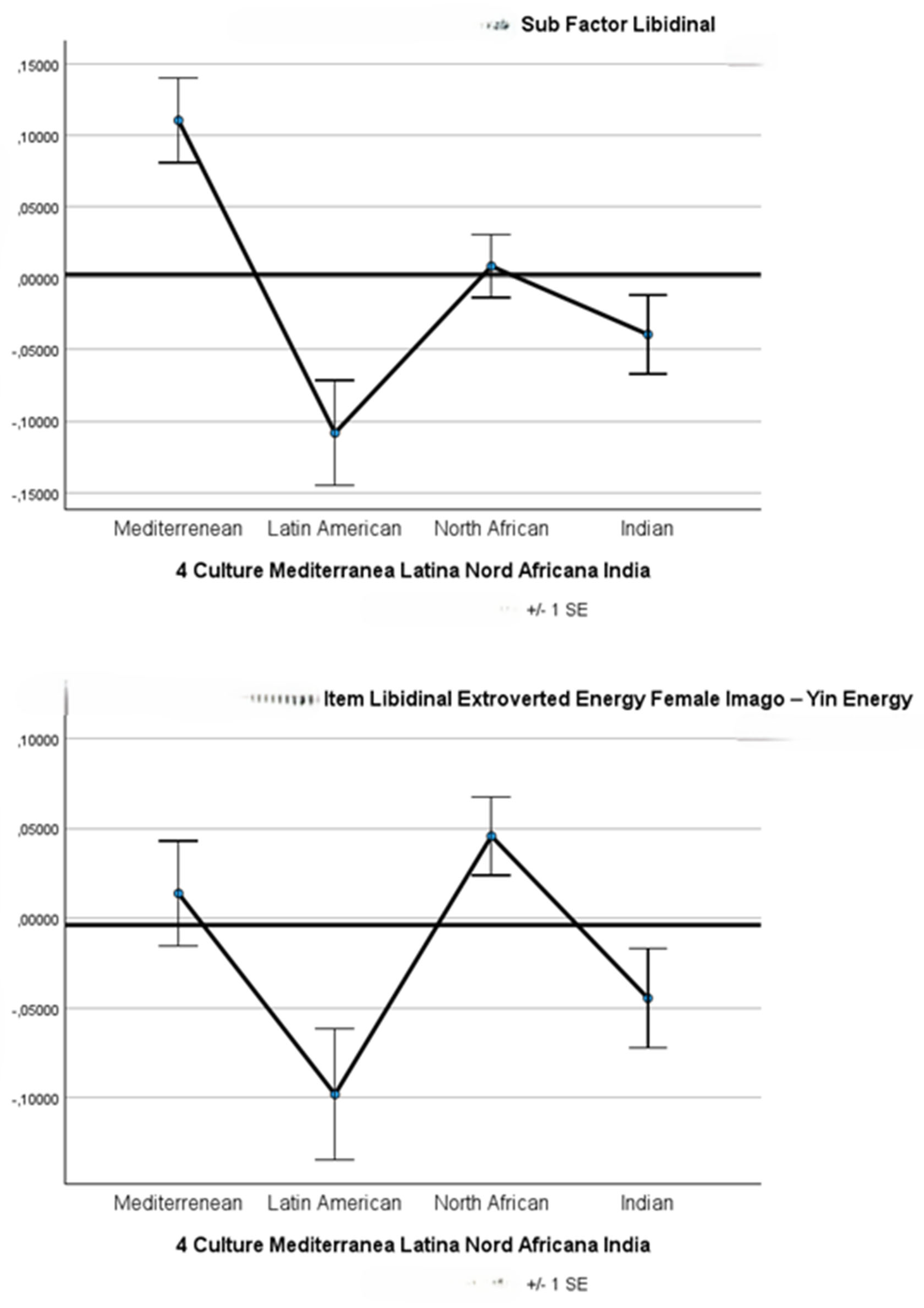

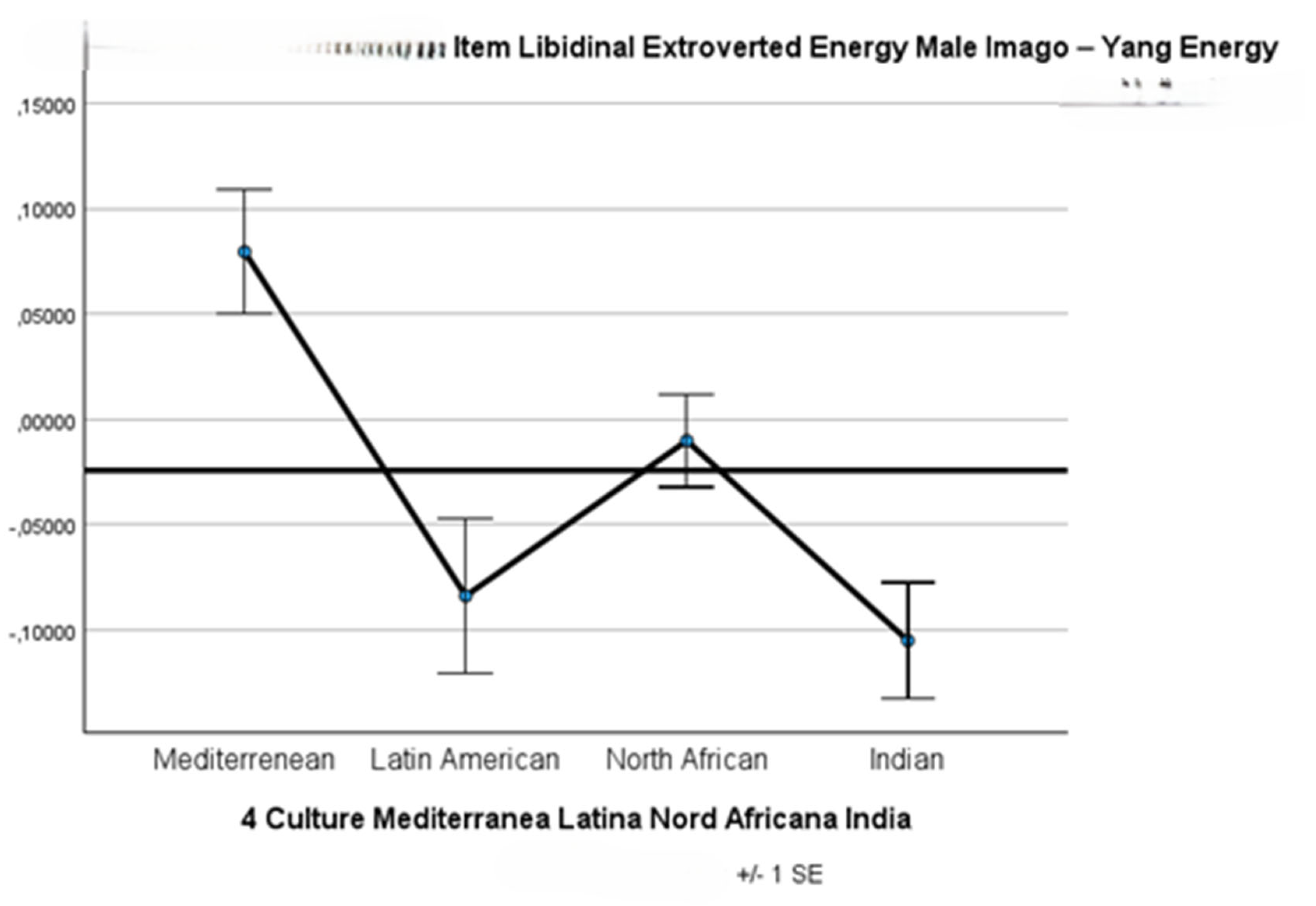

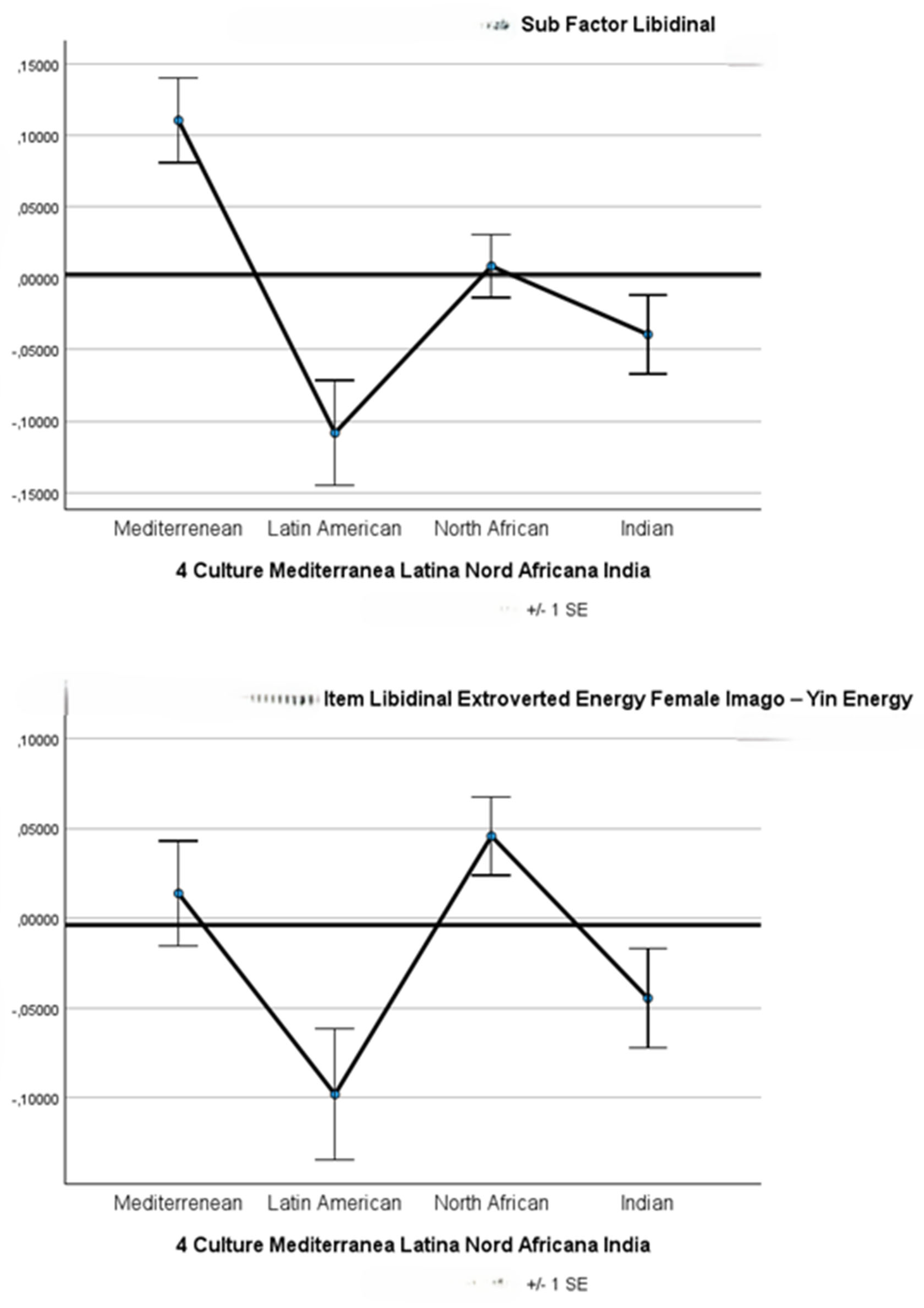

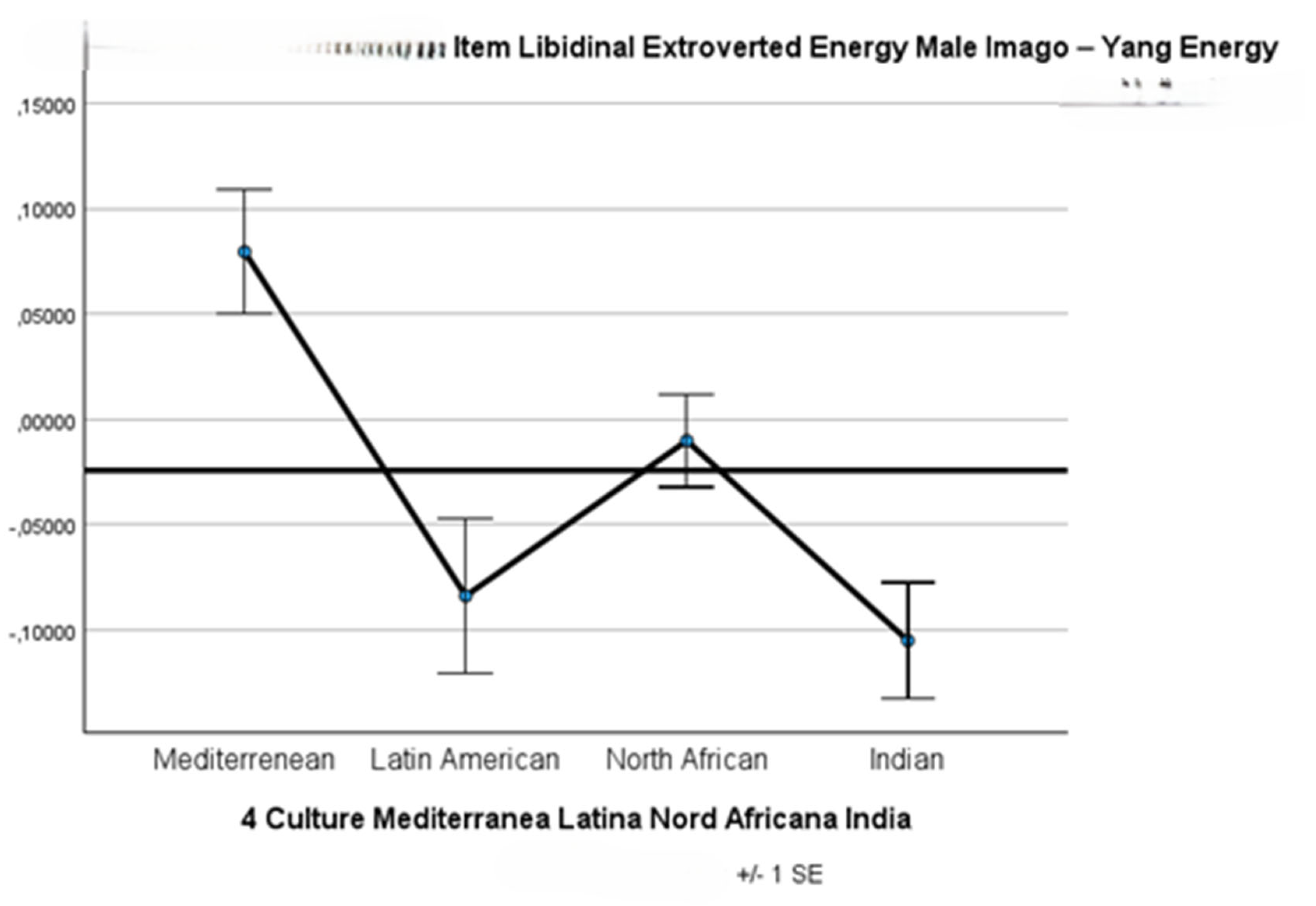

The Libidinal Energy factor indicates a strong predominance of Mediterranean influence. In the area of “Female Energy”, North Africans exhibit a significant cultural variance, displaying a higher expression of “yin” energy (F = 7.995, p = 0.000) when compared to the Mediterranean. For “Male Energy”, the differences are also significant but less pronounced, with Mediterranean individuals showing higher levels of “yang” energy (F = 5.394, p = 0.001).

The Psychomotor Development factor

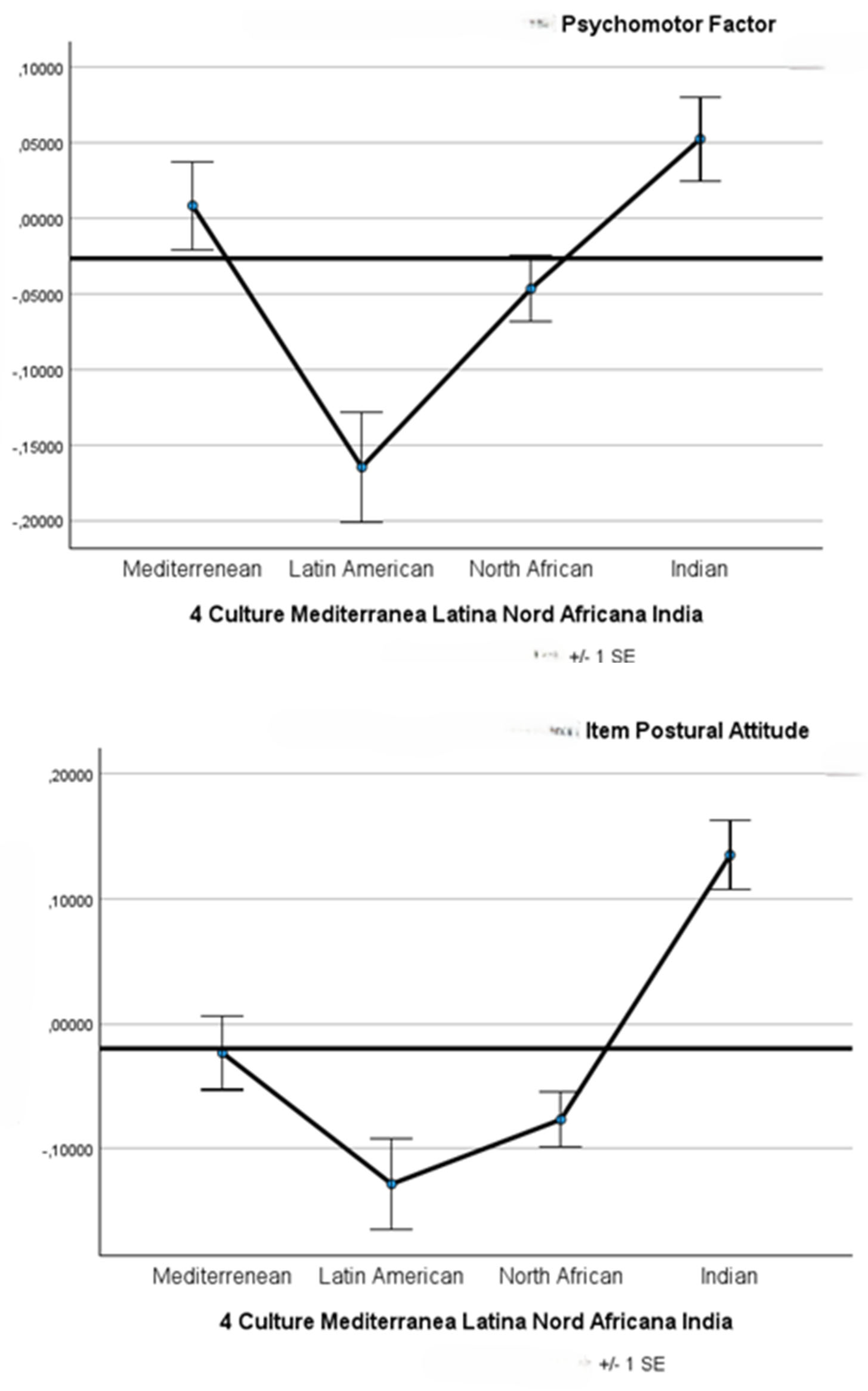

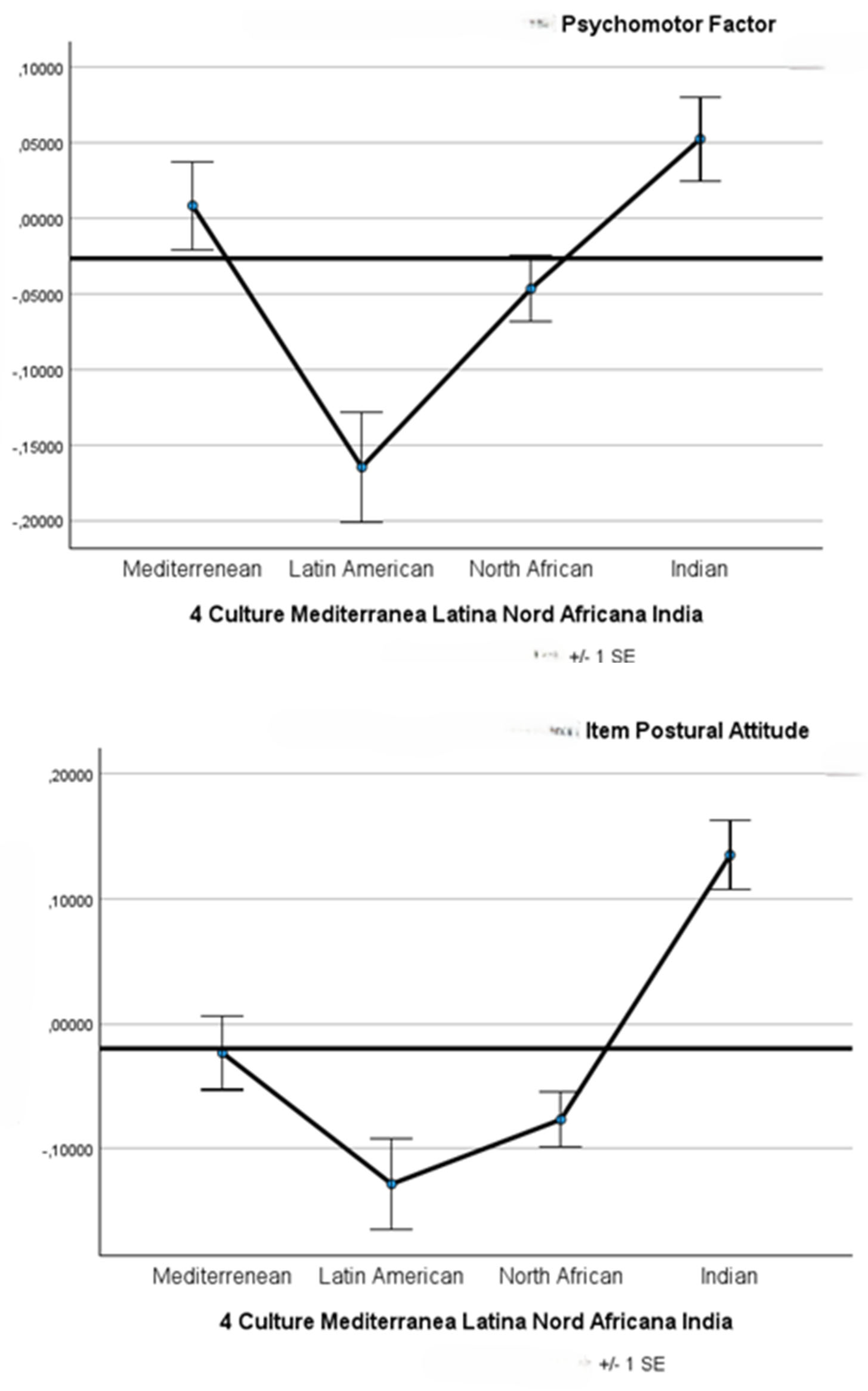

The Psychomotor Factor indicates that Indians are the highest performers, particularly in tonic-postural development. This aspect encompasses the progression of postures from the fetal position to prone and supine positions, reflecting body horizontality.

The Psychomotor Factor also outlines the stages of psychomotor development, including postures based on the horizontal and vertical axes of the body in space and the relationship with objects and others. Key elements of this factor include static and dynamic proprioception, the quality of preferred objects, and the relational horizon. It explores four fundamental phases of psychomotor development: in addition to tonic-postural development, it examines postural-kinetic skills, cognitive development shaped by interaction with cultural artefacts, and the development of social skills.

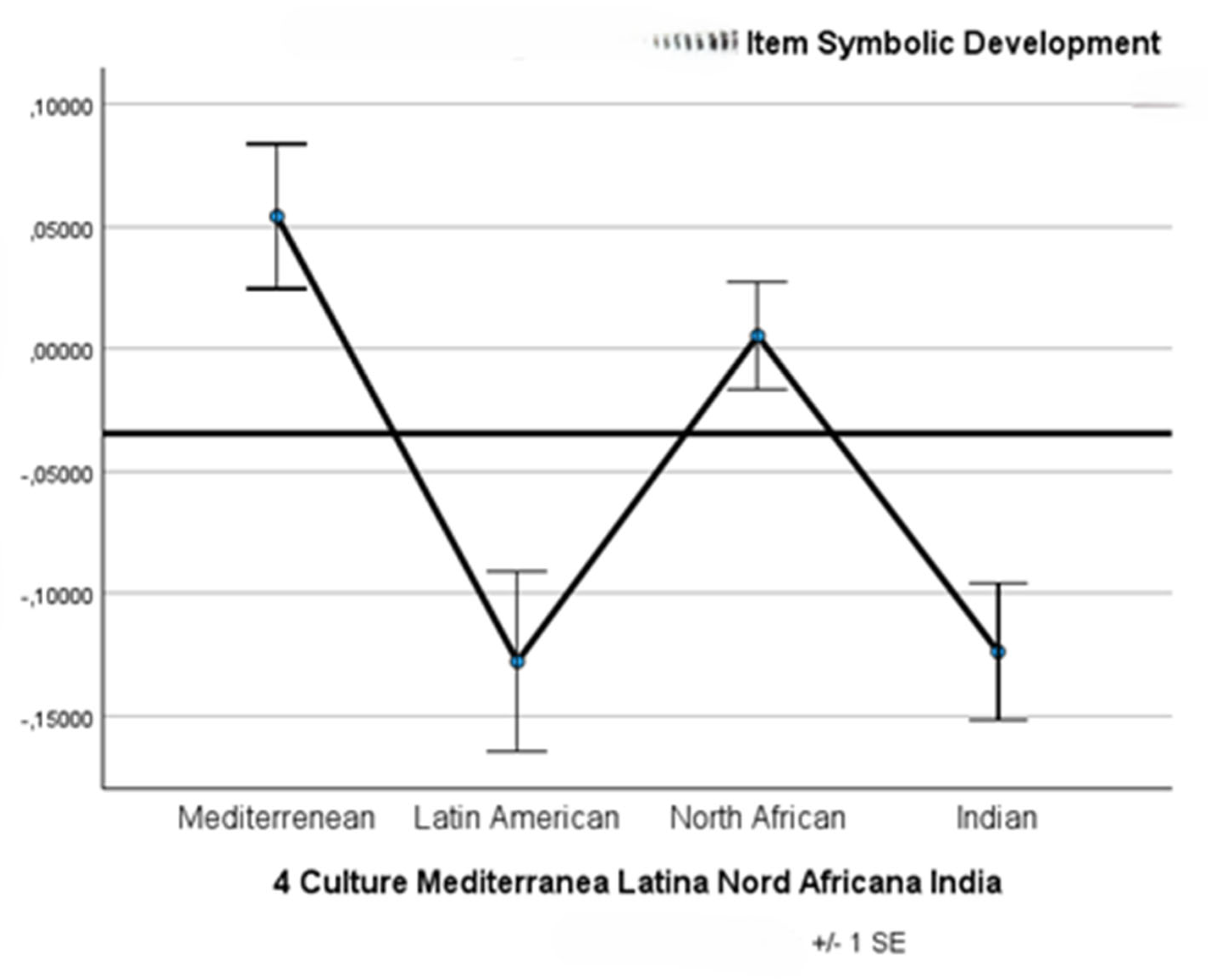

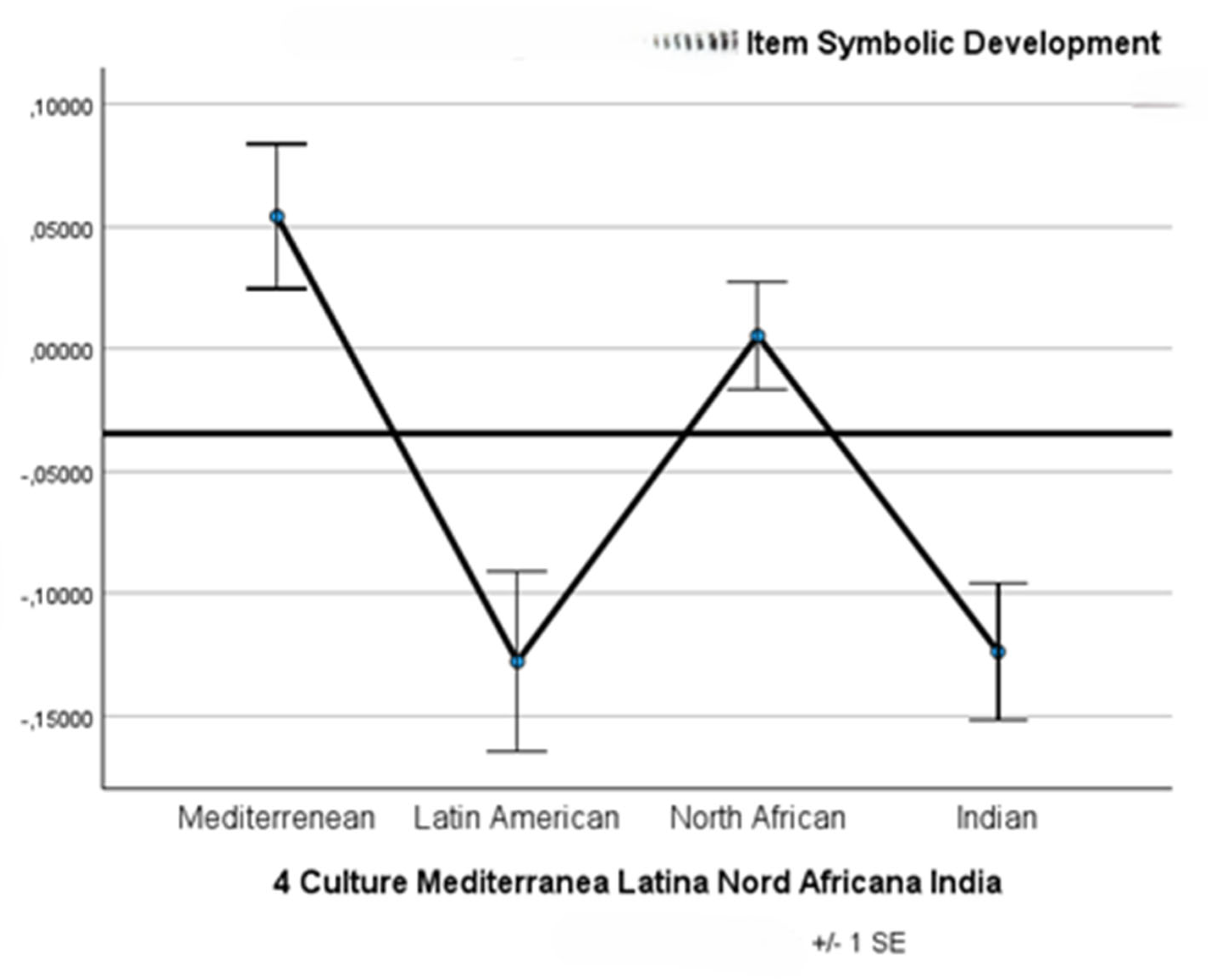

The Postural Attitude item (F = 15.645, p = 0.000) reveals a significant difference between Indians and other subjects, indicating that Indians tend to show more evolved postural development leaning towards openness. In contrast, the Symbolic Development item (F = 9.659, p = 0.000) suggests that both Indians and Latin Americans perform below the average in their ability to develop symbolic faculties.

Summarising data

The Multivariate effects discussed here indicate strong cultural differences across all dependent variables, with Ego Sensitivity and Internal Body Models being the most influential. Univariate findings across all categories highlight the significance of Drive Energy Constructs and Ego Skin Factors, emphasising the impact of cultural traditions on psychological and psychomotor development.

In the Mediterranean, there appears to be a notable emphasis on symbolic development in Psychomotor Development (F = 9.659, p = 0.000). Relational Constructs receive significant attention regarding fusion/separation dynamics (F = 13.443, p = 0.000), while the Internal Body Model demonstrates strong integration of mind-body awareness in internal body perception (F = 25.996, p = 0.000).

Latin America has more balanced expressions of female energy (F = 7.995, p = 0.000) and male energy (F = 5.394, p = 0.001) within the Libidinal Energy Factor. Fusion and separation dynamics in Relational Constructs are nuanced, possibly due to communitarian values that emphasise extended family and group harmony. Additionally, the variance in low biorhythms of internal energy in Processing Energy items is unexpectedly significant (F = 21.852, p = 0.000).

North Africans show an average emphasis on holding energy in Drive Energy Constructs (F = 31.110, p = 0.000), while Expelling energy reveals significant variation linked to expressions of aggressiveness (F = 12.107, p = 0.000). Ego Skin Factors for North Africans reveal heightened Ego Sensitivity (F = 33.509, p = 0.000), indicating increased awareness and responsiveness to external stimuli, likely rooted in environmental and social adaptability. Ego protection (F = 14.816, p = 0.000) is average, reflecting weak self-defence mechanisms.

In Drive Energy Constructs, the results for Indians are more balanced than those of the other three nationalities, with all four items falling around the average line. Opening Energy (F = 12.308, p = 0.000) and Processing Energy (F = 21.852, p = 0.000) may reflect cultural practices focused on energy flow, such as yoga, meditation, introspection, and mental discipline. Ego Skin Factors also emphasise Self-willing (F = 10.951, p = 0.000), focusing on intentional actions. The Internal Body Model and Drive, Libidinal, and Bonding Sub Factors show variations in internal body perceptions (F = 25.996, p = 0.000), likely influenced by holistic health systems.

Significant cultural differences were observed in nearly all variables, particularly in Psychomotor Development, Bonding/Relationship, and Drive Energy Constructs. Factors such as Ego Sensitivity and Ego Protection demonstrated high statistical significance, highlighting cultural influences on self-perception and boundary management.

Variables like Self-assertiveness and Self-concept Complexity did not show significant differences. In the BIST model, these items belong to the Body Image theoretical framework. The main differences between cultures within the Body Schema framework may suggest that societal factors shape body organisation at a deep level. The BIST findings underscore profound cultural differences in body schema and related constructs across Mediterranean, Latin American, North African, and Indian cultures. These variations likely reflect the interplay of cultural norms, embodied practices, and psychological constructs in shaping individual perceptions and behaviours.

4.2. The effect size of Sports, Hobbies and Dance/General activities on National Character as seen by BIST

The questionnaire collected information on sports, hobbies, dance, and other activities. Correlating this data with Body Image and Schema Tests for each sample group revealed cultural differences in the impact of these activities.

In the Mediterranean, sports have a minor role with weak correlations to psychomotor and self-image factors. They focus more on symbolic development and relational constructs, like “Ego Protection.” Hobbies show limited influence on psychomotor and relational constructs, indicating a lower cultural emphasis than sports.

In Latin America, significant correlations exist between sports and body image, reflecting social and aesthetic norms in constructs such as “Fusion/Separation.” Hobbies and dance are minimally relevant for psychomotor development, with only slight involvement in relational constructs.

North Africa emphasises energy retention (“Hold”) and relational dynamics in sports, while dance has minimal effects.

In India, strong relationships were found between sports, psychomotor factors, and self-perception. Indians excel in symbolic and psychomotor development, with a moderate emphasis on dance aligning with social roles. Hobbies have weak but notable effects on self-perception.

Overall, the strongest correlations with Body Schema are in India and North Africa, while the Mediterranean shows the weakest impact of sports on psychomotor and symbolic development.

Dance is significant in Latin America and India’s relational and symbolic constructs but has less impact in the Mediterranean and North Africa. Hobbies generally have limited influence across cultures, making them secondary to more active pursuits like sports and dance.

Hobbies show minimal effect on body image, schema, and psychomotor constructs, with sports playing a more dominant role. The BIST results suggest that while sports and dance influence body image and schema differently across cultures, relational and psychomotor constructs are more prominent.

In team sports, Mediterranean influences positively affect body image and relational constructs but have minimal impacts on psychomotor factors. In Latin America, there is a negative correlation between body image and relational constructs. North Africans show improved psychomotor skills and motivation but struggle with relational constructs, indicating individualism. Indians have slight positive effects on psychomotor factors and self-perception, but these are weaker than in other cultures.

Resistance sports impact BIST differently by region. The Mediterranean shows improved self-perception related to strength and endurance, while Latin America moderately correlates with body image and cultural ideals. North Africans link psychomotor and motivational constructs to these sports but adopt an individual-focused perspective regarding relational constructs. In India, effects are mostly symbolic, with minimal impact from relational constructs.

Playing music has varying impacts on BIST. In the Mediterranean, correlations with relational constructs are weak, and no significant relationships exist with body image. Latin America shows slightly stronger relational correlations and a significant negative correlation with body image. North Africans demonstrate negligible effects, while Indians show marginal correlations with self-perception. The strongest impacts are in Latin America, where relational and body image constructs are most affected.

The influence of painting and drawing on BIST is limited across all cultures, with some stronger self-perception connections in India. Singing has minimal to weak effects on BIST in all cultures.

Walking and trekking impact BIST variably. The Mediterranean shows weak correlations, while Latin America has moderate relational impacts. North Africans emphasise psychomotor skills and motivation, whereas Indians exhibit minimal correlations with body image and psychomotor factors.

4.3. Key Conclusions

The Body Image and Schema Test (BIST) reveals significant cultural differences in psychodynamic and body-related constructs across Mediterranean, Latin American, North African, and Indian cultures. Key findings highlight cultural variations in Drive Energy Constructs: Mediterranean demonstrate a strong capacity for Holding Energy, indicative of symbolic retention. North Africans and the Mediterranean exhibit a higher level of Expelling Energy, associated with assertiveness, while Latin Americans display a calmer energy dynamic.

Regarding Ego Skin Factors, Mediterranean and North African groups show greater Ego Sensitivity, suggesting they are more responsive to external stimuli. Conversely, Indian and Latin American participants exhibit more protective ego traits. Regarding Psychomotor Development, Indians score highest in Postural Attitude, which signals an advanced level of physical and symbolic balance rooted in their cultural practices.

Relational Constructs indicate that Mediterranean and North African cultures emphasise Fusion/Separation, reflecting relational dynamics grounded in collectivism and family ties. Additionally, in the areas of Symbolic and Relational constructs, the Mediterranean region prioritises Symbolic Development, focusing on artistic and symbolic expressions of relationships. Indian culture, on the other hand, integrates a holistic self-perception through balanced Internal Body Models.

The influence of sports and dance on psychomotor and relational constructs varies across cultures, with the most profound impact observed in India and Latin America. Hobbies have a minimal overall effect.

5. Discussion

The Body Image and Schema Test (BIST) operates within a psychodynamic framework, highlighting how cultural and physical environments influence the Internal Body Model and shape embodied Self-Perception. This framework reflects the integration of mind and body in self-perception. Notably, constructs related to Energy Dynamics, such as Holding and Expelling Energy, symbolise unconscious processes of energy regulation and emotional expression, thereby linking psychodynamics with bodily practices.

Regarding Relational Dynamics, the Fusion/Separation construct encapsulates the psychodynamic interplay between individuality and relational attachment, underscoring the cultural variability in boundary management (the “personal inner space”). Furthermore, the focus on Symbolic Development within BIST bridges physical embodiment with cultural narratives, emphasising the significance of symbols in constructing psychological meaning.

The BIST framework offers a psychodynamic perspective on personality that complements and extends Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, Kretchmer’s typology, and trait theory. While there are overlaps in relational and energy constructs, BIST’s emphasis on embodiment and cultural specificity reveals deeper layers of personality. Its constructs enhance our understanding by integrating the symbolic, physical, and cultural aspects of self-perception and behaviour, making it a distinctive tool for cross-cultural psychological exploration.

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions of Power Distance (Hofstede, 1980) indicate that Mediterranean and North African cultures are more sensitive to hierarchy and boundaries. In BIST, these may correspond to Ego Sensitivity and Protection, aligning with Hofstede’s findings on high power distance. In contrast, Indian and Latin American cultures show a more balanced approach. The individualism-collectivism dimension highlights the Mediterranean focus on relational dynamics. In BIST, this dimension could be represented by the Fusion/Separation items, aligning with collectivist tendencies, while North African individuality in relational constructs partially contradicts Hofstede’s collectivist categorisation. BIST’s emphasis on symbolic and energy regulation in Mediterranean cultures mirrors Hofstede’s high Uncertainty Avoidance (Javidan, M., House, R. J., Dorfman, P. W., Hanges, P. J., & Sully de Luque, M., 2006).

Both Hofstede’s and BIST highlight relational and boundary-related constructs, demonstrating how cultural norms shape self-perception and decision-making. Some differences arise because Hofstede abstracts cultural dimensions, while BIST provides psychodynamic insights into embodied practices (Tung, R. L., & Verbeke, A., 2010; Venaik, S., & Brewer, P., 2010).

A comparison of BIST with Kretschmer’s Typology (Kretschmer, 1925/1926) reveals that Asthenic Types are most common among Indian participants, whose disciplined energy regulation (balanced Holding and Processing) aligns with Kretschmer’s description of introspective Asthenic types. Pyknic Types are more frequently found in Mediterranean participants, whose symbolic focus and relational closeness correspond to sociability and emotionality. North Africans exhibit high expelling energy, reflecting Kretschmer’s athletic type, characterised by assertiveness and physicality. Both models connect physicality with psychological traits. BIST’s energy constructs complement Kretschmer’s body-constitution theory. However, it is crucial to note some differences: BIST incorporates symbolic and relational dimensions absent in Kretschmer’s typology, which directly links body types to mental disorders, a connection BIST does not make.

When comparing BIST with Trait Theory, the trait of Extraversion (McCrae & Costa, 1987) seems to align with BIST. High expelling energy, particularly in North African cultures, contrasts with Mediterranean symbolic development, which may reflect openness. Mediterranean and Latin American cultures’ relational constructs (Fusion/Separation) parallel the Agreeableness trait. Neuroticism could pair with elevated Ego Sensitivity in Mediterranean and North African cultures. Traits such as Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism correspond to BIST constructs like energy dynamics and relational openness. However, differences between the two models are evident: Trait Theory is abstract and generalised, whereas BIST is grounded in embodied psychodynamics. BIST integrates cultural and symbolic factors, enriching trait-based personality profiling.

In conclusion, this exploration of how a test based on embodied theory and psychodynamic theory, the Body Image and Schema Test, can trace a profile of the national character it is possible to say that its focus on embodiment and relational energy provided nuanced insights into national character and temperament, enhancing cross-cultural psychological studies.

It is essential to emphasise that BIST items-variables such as Self-assertiveness and Self-concept complexity did not show significant differences. In the BIST model, these items are related to Body Image. The primary differences between cultures are found in the BIST factors and items concerning the Body Schema framework. This indicates that cultural factors significantly differentiate body organisation at a fundamental level while they do not significantly impact the Self-image that individuals exhibit with BIST tool.

Cultural differences in body schema and related constructs across Mediterranean, Latin American, North African, and Indian cultures, as established by BIST, likely reflect the complex interplay of cultural norms, embodied practices, and psychological constructs in shaping individual perceptions and behaviours.

In summary, cultures appear to influence body schema significantly but have less impact on individuals’ body image within those cultures, or, at list, not appreciable by the Body Image and Schema Test.

While the study offers valuable insights, it has several limitations. The reliance on self-reported data may introduce biases, and although the sample is diverse, it does not capture intranational variations. Future research should address these issues by utilising larger, more detailed datasets and incorporating neurocognitive tools to enhance the understanding of embodied identity.

Several areas require further exploration, including neurocognitive insights investigating how cultural values are neurologically encoded and influence embodied identity and behaviour. Longitudinal studies should examine how cultural dimensions and embodied identity evolve, particularly in an increasingly globalised world. Additionally, research should consider intranational variability by looking into subnational and regional differences and the role of cultural narratives in shaping body schema and identity.

At this point, it should be clear that this research emphasises the need to integrate cultural dimensions with embodied identity to better understand national character and socio-psychological differences. The findings lay a foundation for addressing cross-cultural challenges in various fields, from health interventions to bio-political (Foucault, 2003) policies, and highlight the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration to explore the complexities of identity in a globalised context.

Post Scriptum

Results of the four national characteristics found with BIST, authors asked to Chat GPT 4o to write a narrative description of the Mediterraneans, Latin Americans, North Africans and Indians. Here is the result.

As a journalist, write discursively about the four national profiles, like a woman/man of each nationality.

1. The Mediterranean Persona: The Charismatic Storyteller

Picture a Mediterranean man or woman: assertive, passionate, and deeply connected to their community. This person moves with a natural poise, their posture hinting at a strong inner foundation. Their energy radiates a fiery intensity, especially in moments of action or creativity. Symbolism is at the heart of their personality—they value traditions, stories, and the unspoken bonds that tie families and communities together. They thrive on relationships, balancing closeness and independence with an innate ability to adapt. Sensitive to their environment, they pick up on nuances others might miss, embodying a blend of vitality and depth that makes them magnetic.

2. The Latin American Persona: The Harmonious Connector

Imagine a Latin American woman or man—calm, grounded, and radiating warmth. Their demeanour exudes balance, whether in their measured gestures or their interactions. This person cherishes their bonds with family and friends, valuing collective harmony over individual assertion. Their energy flows gently, never rushed, yet steady enough to sustain them through challenges. While less focused on abstract symbolism, they shine in practical, heartfelt connections. Protective of their personal space, they carefully manage boundaries, revealing a thoughtful nature. Their essence is one of connection—anchored by community and enlivened by an ever-present sense of togetherness.

3. The North African Persona: The Dynamic Negotiator

Visualise a North African individual—assertive, adaptable, and vibrant. Their energy pulses with intensity, and their movements convey a readiness to act. Nevertheless, within this dynamism lies a deep sensitivity to the world around them. They respond to life with a heightened awareness, balancing assertiveness with an acute understanding of the nuances in their environment. Family and community are central to their identity, yet they maintain a strong sense of individuality, navigating relationships with a deft touch. Their spirit is grounded and bold, embodying a culture that values resilience and adaptability, infused with a keen sense of self-expression.

4. The Indian Persona: The Mindful Achiever

Picture an Indian man or woman—composed, intentional, and deeply reflective. Their presence is calm yet focused, hinting at an inner discipline shaped by tradition and personal growth. Their movements are deliberate, their posture upright, reflecting a physical and symbolic balance. This person approaches life with thoughtfulness, often seeking harmony between their inner world and external demands. Relationships are built on cooperation and mutual respect, emphasising helping others thrive. Their energy is neither impulsive nor subdued—it flows purposefully, channelled through practices like meditation or mindfulness. The Indian persona symbolises introspection, discipline, and a profound connection to self and community.

Statements and Declarations

Competing interests

The author did not receive support from any organisation for the submitted work.

The author has no competing interests to declare relevant to this article’s content.

The author certifies that he has no affiliations with or involvement in any organisation or entity with any financial or non-financial interest in this manuscript’s subject matter or materials.

The author has no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article.

Data availability

Ethical approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study were approved by the Human Research Ethics committee of the University of Bergamo: «MINUTES N. 03/2023 OF THE ETHICS COMMITTEE SESSION OF 03/15/2023. On 15 March 2023, at 10.30, the Committee for Research Integrity and Ethics of the University of Bergamo met electronically as required by Article 6 Paragraph 3 Regulation for the functioning of the Committee for Research Integrity and Ethics (DR rep. 388/2016 prot. 81201/I/3 of 07/18/2016).»

Informed consent

Informed consent from all individual participants included in the study has been reached. According to Art. 13 of EU Regulation 2016/679 and the single country applicable legislation, with particular reference to the Italian Legislative Decree 196/2004 integrated with Decree 101/2018, data collected for the present research guarantee respect for personal privacy sample rights in all senses.

References

- Anzieu, D. (1989). The Skin Ego (C. Turner, Trans.). Yale University Press. (Original work published 1985).

- Beugelsdijk, S., Kostova, T., & Roth, K. (2017). An overview of Hofstede-inspired country-level culture research in international business since 2006. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(1), 30-47. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-016-0038-8. An overview of Hofstede-inspired country-level culture research in international business since 2006. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(1), 30-47. [CrossRef]

- Fornari, F. (1976). Psychoanalysis of War. Indiana University Press.

- Foucault, M. (2003). Society Must Be Defended: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975-1976 (D. Macey, Trans.). Picador.

- Giannotta, A. P. (2022). Corpo funzionale e corpo senziente. La tesi forte del carattere incarnato della mente in fenomenologia. Rivista Internazionale di Filosofia e Psicologia, 13(1), 41-56. [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Sage Publications.

- Hofstede, G. (2010). The GLOBE debate: Back to relevance. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(8), 1339-1346. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2010.31. GLOBE debate: Back to relevance. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(8), 1339-1346. [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Javidan, M., House, R. J., Dorfman, P. W., Hanges, P. J., & Sully de Luque, M. (2006). Conceptualizing and measuring cultures and their consequences: A comparative review of GLOBE’s and Hofstede’s approaches. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(6), 897-914. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400234. Conceptualizing and measuring cultures and their consequences: A comparative review of GLOBE's and Hofstede's approaches. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(6), 897-914. [CrossRef]

- Kant, I. (1978). Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View (H. H. Rudnick, Trans.). Southern Illinois University Press. (Original work published 1798).

- Kretschmer, E. (1926). Physique and Character (W. J. H. Sprott, Trans.). Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd. (Original work published 1925).

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1987). Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 81–90. [CrossRef]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of Perception (C. Smith, Trans.). Routledge & Kegan Paul. (Original work published 1945).

- Montemurro, B., & Hughes, E. (2024). Erotic capital and erotic dividends. Sexualities. https://doi.org/10.1177/13634607241239111. Erotic capital and erotic dividends. [CrossRef]

- Montesquieu, C. de S. (1989). The Spirit of the Laws (A. M. Cohler, B. C. Miller, & H. S. Stone, Trans.). Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1748).

- Rocha, P. (2024). Cultural correlates of personality: A global perspective with insights from 22 nations. Cross-Cultural Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/10693971241264363 Correlates of personality: A global perspective with insights from 22 nations. Cross-Cultural Research. [CrossRef]

- Tung, R. L., & Verbeke, A. (2010). Beyond Hofstede and GLOBE: Improving the quality of cross-cultural research. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(8), 1259-1274. [CrossRef]

- Venaik, S., & Brewer, P. (2010). Avoiding uncertainty in Hofstede and GLOBE. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(8), 1294-1315. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).