1. Introduction

Female students around the world continue to face significant difficulties due to body image dissatisfaction in academic settings (Bake, 2018). Body image dissatisfaction is a subjective assessment of a person’s looks and emotions. It can be described as a multidimensional construct that describes internal, subjective representations of physical appearance and bodily experience, attitude toward the body in general, and size, form, and beauty in particular (Firdevs & Sevil, 2015; Tykya & Wood-Barcalow, 2015). In the 1930’s the term body image was first introduced, and the main description was that the body of an individual not only affects their physical attributes, but also contributes to their general well-being (Grogan, 2016). Forney and Ward (2016) pointed that university students are particularly vulnerable to body dissatisfaction, but there is also a substantial correlation between eating habits and body dissatisfaction. A substantial risk factor for disordered eating behaviours, such as restricted eating, dieting, binge eating, and bulimia nervosa, has been identified in university students who are not satisfied with their bodies.

Students who view their bodies negatively in relation to culturally regarded features may experience low self-esteem, a sense of inferiority, and a lack of life satisfaction. They are more likely to experience eating disorders, depression, and anxiety (Makwana, Parkin & Farmer, 2018). When levels of unhappiness are at their peak, this may seriously hinder social, academic, and/or occupational functioning. Since, good and thinness are currently associated with attractiveness, society values them while fiercely rejecting their opponent, fat. Studies reveal that women have tried to alter their bodies to conform to these norms, despite the fact that the ideal of female beauty varies depending on esthetical standards that are chosen at each time (Mamabolo, 2019; Sharpe, Tiggemann & Mattiske, 2014; Marcus & Harper, 2014).

In South Africa, Puoane (2014) shows evidence of conflicting studies reported on the increasing number of urban South African female students preoccupied with the urge to be skinny and are heavily impacted by social media. Fifty-six percent (56%) of women acknowledged that social media culture has a detrimental impact on body image and the pressure to be flawless, and forty- two percent (42%) of women claimed that social media made them feel worse and less confident in their own bodies (Lipson et al., 2017). Another study by Meier and Grey (2014) looked at how exposure to appearance and Facebook photo activities are related to problems with adolescent girls’ body image. They discovered a substantial correlation between increased appearance exposure on social media and weight dissatisfaction, a striving for thinness, internalizing the ideal and self-objectification.

In the Limpopo province, several studies concluded that compared to men, women are more likely to view themselves as not fitting ideals of weight. Most often, this is seen in young adult females (Prevos, 2016; Mchiza, Parker. & Makoae, 2015; Tshililo, Netshikweta, Tshitengano & Nemathaga, 2016). In addition to actual weight, eating disorders and weight loss behaviours are significantly influenced by perceived weight status (Cheung, Lam & Bibby, 2017).

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design

The study is qualitative in nature, and the methodology allowed the researcher to learn in-depth details about the subject under investigation and speak with the participants in order to gather rich data by recording feelings, emotions, and other subjective perceptions and values throughout the research process (Bryman, 2016).

2.2. Population and Sample

Convenience sampling were used, as the researcher was looking for any female student at the University of Venda. This sampling technique involved non-random sampling, which entails including members of the target population who meet certain practical requirements for inclusion in the study, such as accessibility, geographic closeness, availability at a specific time, or desire to participate (Etikan, 2016). Convenience sampling is generally considered easy to employ and is less time consuming. The researcher recruited any female student enrolled at the University of Venda who was willing and had given consent to participate in the study. The sample size in this study was 10.

- (a)

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

- (b)

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

Male students enrolled at the University of Venda.

Students who are not enrolled in the University of Venda.

University of Venda students who are above 25 years.

2.3. Data Collection

Prior to data collection, the researcher obtained ethical clearance from the University of Venda Research. Thereafter, students were identified on campus and were asked to be participants in the study. They were given consent forms to sign by the researcher, and only after obtaining the students informed consent, they voluntarily participated in the study. Participants were allowed to choose their preferred and comfortable settings for interviews around campus. The interviews lasted from 15-45 minutes depending on the participant’s information. All of the interviews were conducted in English. The interviews were conducted in various settings at the University of Venda campus such as the cafeteria, on a bench, under a tree and student’s residences, as some of the participants felt comfortable to participate in the study at their own private accommodation.

As part of the resources of data collection, the researcher made use of field notes. Written notes included all information obtained during the course of the interviews, including non-verbal communication cues, information shared by participants and emotions expressed. The cellular phone was used to record participants because it was not easy for the researcher to note down all the observations and shared information during the course of the interview. The recordings enabled the researcher to not get distracted by writing down all the information shared but instead, the focus was on interacting with the participants. There were some participants who were however, not comfortable with being audio recorded regardless of being assured of confidentiality. Therefore, the researcher ensured that there was excellent balance in taking notes, asking questions and listening.

2.4. Ethical Consideration

The researcher obtained ethical clearance from the University Higher Degrees Committee (The research Ethics Social Sciences committee, RESSC) before data collection process (Ethical no FHS/22/PSYCH/09/1909, date of approval, August 2022). Consent was obtained from the participants who agree to be part of the study verbally and through signed consent forms. Confidentiality was maintained by not disclosing participant’s real names. The participants’ names were coded as participant 1, participant 2, participant 3 etc. to protect their identities. The information provided by participants was stored in the personal laptop with password and all physical records and equipment were actively guarded and kept in locations that could be locked. The researcher conducted a debriefing session after data collection process and did not identify any emotional or psychological harm. Arrangements were made with student counselling at the University of Venda had there been any emotional or psychological harm was identified during debriefing process.

2.5. Data Analysis

Thematic content was used to analyze data. According to LoBiondo-Wood and Haber (2014), Thematic Content Analysis is a technique for using themes from the collected data to find, analyze, and report trends. The transcribed data were described in rich detail meaning that researchers familiarized themselves with the data searching for meaning, ideas and identifying possible patterns, generating initial codes, and considering participants’ experiences and the significance of emotional content, potential themes were developed, refined and further interpreted, were various themes and subthemes emerged during the analysis which increased the understanding of the phenomenon.

2.6. Trustworthiness of the Study

Trustworthiness or rigor of a study (credibility, dependability, conformability, and transferability) were used to refers to the degree of confidence in data, interpretation, and methods used to ensure the quality of a study (Pilot & Beck, 2014)

3. Results

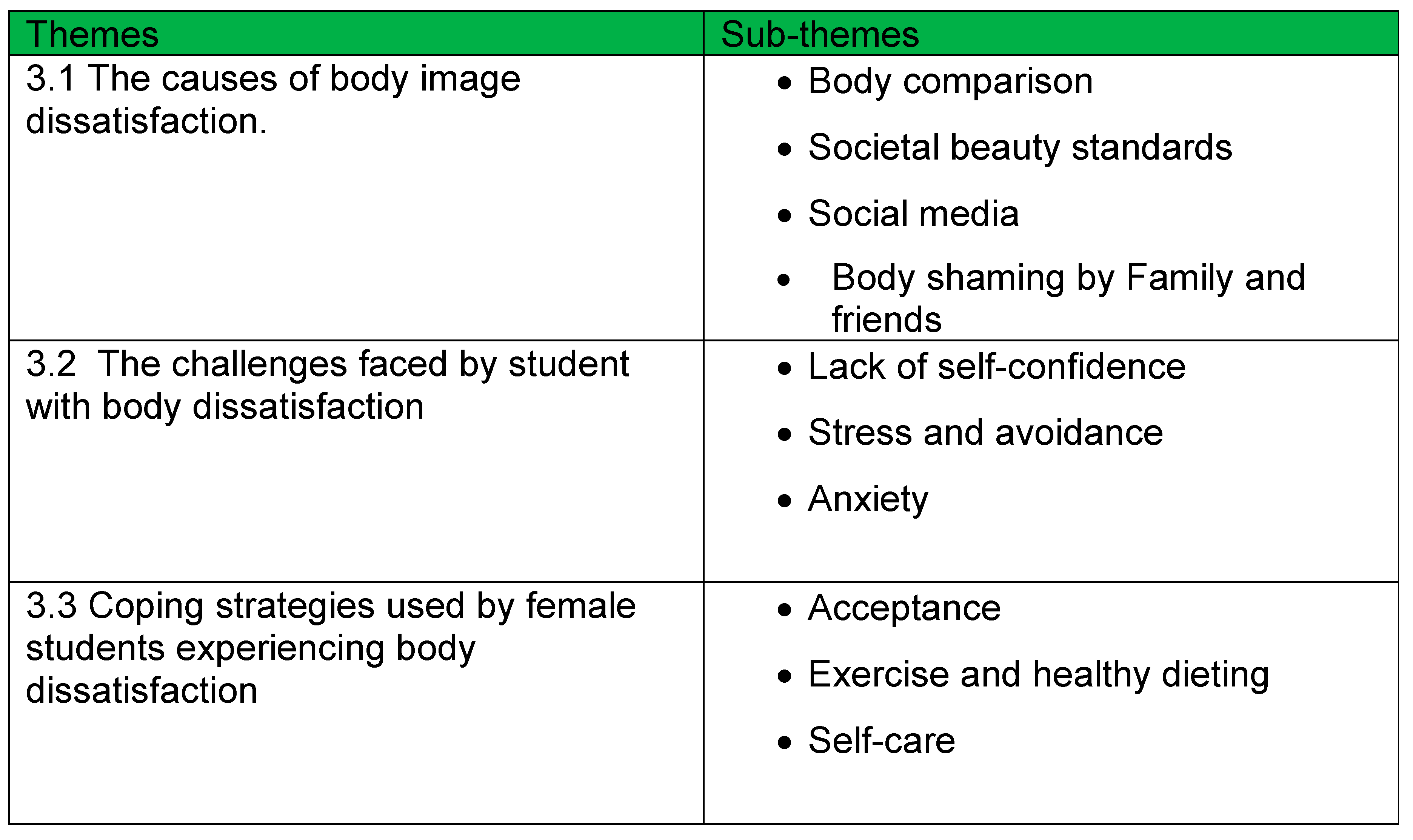

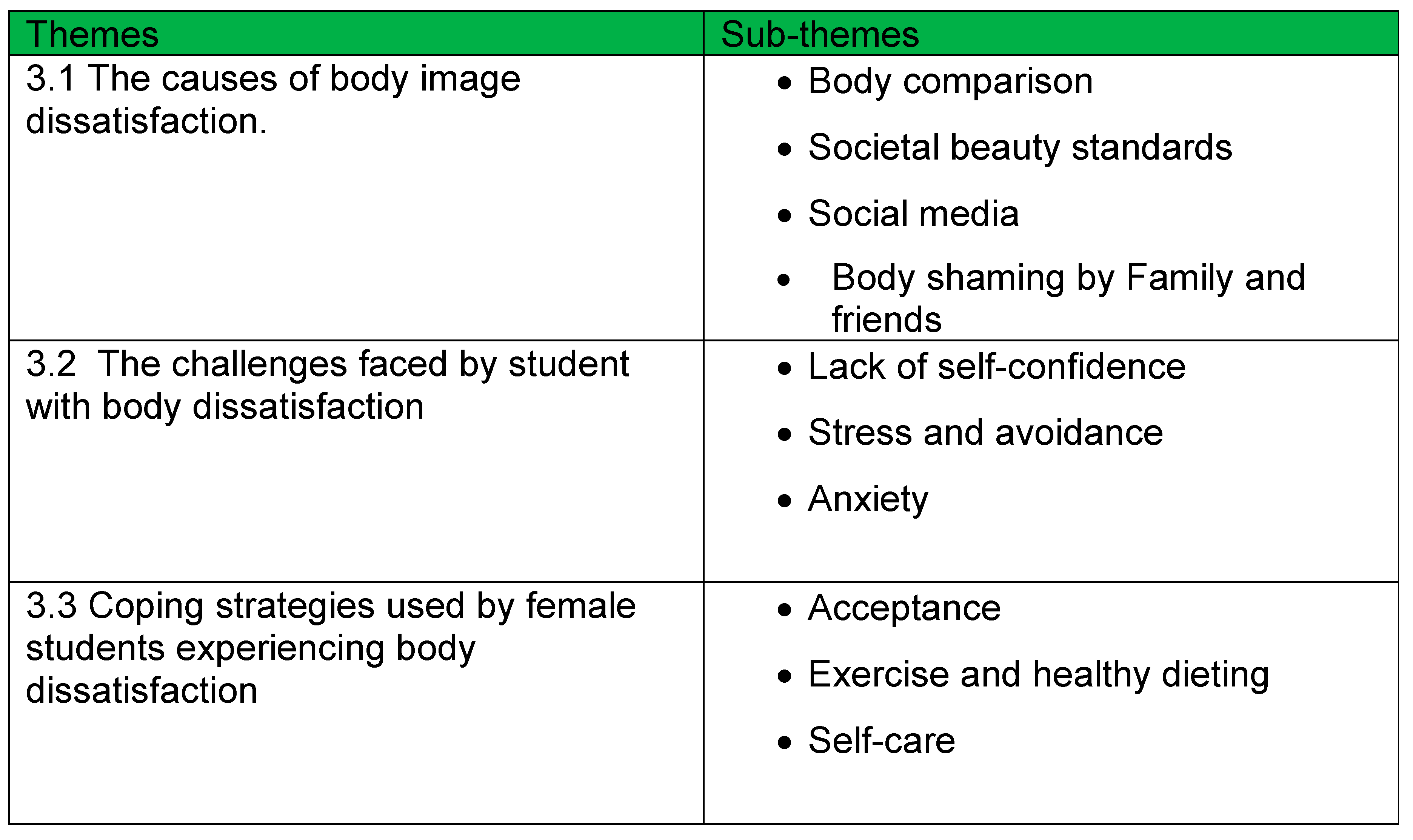

The themes that emerged in the study are summarized in the table below:

3.1. Causes of Body Image Dissatisfaction

3.1.1. Body Comparison

The findings revealed that body comparison was one of the major factors leading to body image dissatisfaction among female students who compared themselves with their friends or other females around them. This is validated by the following statements:

“Umm , mostly it has to be comparison, well, comparing yourself to your friends or any other close people around you. You may find that I have a friend who is thin looking and has great skin tone and at some point I would want to look like that and end up being dissatisfied with how I look’’ (Participant 1).

“I have always admired thick, curvy women and wished to grow into that, but my body responds differently. I gained a bit of weight, but the weight accommodated part of the body I didn’t want to gain’’ (Participant 5).

“If I see certain lady with a beautiful body, am going to compare myself with that person and am going to feel less beautiful if that has a flat tummy and I do not have a flat tummy’’ (Participant 8).

3.1.2. Societal Beauty Standards

Societal beauty standards emerged as one of the leading factors to female student’s body image dissatisfaction. The students indicated that the societal beauty standard put a lot of pressure on them when it comes to its definition of beauty. According to the participant’s society beauty standards, it means being slender, tall, have a flat tummy and be light in complexion. These are the unrealistic beauty standards that set by the society. This is substantiated by the following statements:

“Society places certain standards to beauty and when people do not meet those standards they are then not considered as beautiful which led people to have a negative body image’’ (Participant 2).

“Societal standards, I mean the society has made us believe that if you do not have a smooth body without bodily hair, flat stomach, big bum and light complexion, you are not beautiful enough, magazines books make it even worse as we see models that are structured in a way that society conforms too’’ (Participant 8).

“In modern days it is believed that thinner is better and thicker is ugly and since I am thick it is more evident when am wearing pants. The way in which the society or people around me look at me when I’m in a dress is more judgemental than when am in pants and that just makes me anxious and have less self-confidence’’ (Participant 3).

3.1.3. Social Media

The participants reported that social media is one of the leading factors to body image dissatisfaction among female students. The participants indicated the perfect body pictures they see on Facebook or Instagram contribute to their body image dissatisfaction. This is validated by the following statements:

“Social media, the pressure of posting the perfect picture and acquiring likes on your Facebook or Instagram may make a person to start questioning their appearances, especially when they are not getting enough likes’’ (Participant 3).

“Social media plays a huge part in a negative body image as models or actresses are seen as perfect slender, tall, no pimples just flawless, which creates this standard of what beautiful should look like’’ (Participant 7).

“On social media, people’s posts are always perfect, and the comments also contribute, when you post your picture and you find that the comments are so negative, and people on social media can be really mean when they want so that can affect a person in a very negative manner’’ (Participant 9).

3.1.4. Body Shaming by Family and Friends

The participants reported that friends and family members are among the leading factors to body image dissatisfaction. They indicated that hurtful comments made by family and friends about their body image affect them more. This statement is validated by the following comments:

“The people around me, more especially family and friends as they are the ones who know me since young age, they are the ones who remind me how skinny I used to be and that now I am just obese. All these facts make one feel less appreciated and have a negative body image, especially when such comments come from a close friend and family member they are more believable and hurtful’’ (Participant 3).

“My dissatisfaction with height was triggered by family members and friends who would not let me forget how short I am and how my younger sister is taller than me, even if it was done as a joke to me it became something I wanted to change about myself’’ (Participant 4).

“I became obsessed with my body after a friend told me that I was losing weight. I had not realised it yet but after she mentioned it I went to the mirror and was not happy with what I saw’’ (Participant 6).

3.2. Challenges Faced by Students with Body Image Dissatisfaction

3.2.1. Lack of Self-Confidence

The students reported that body image dissatisfaction affected their self-confidence due to being body shamed when comparing themselves with others. This was validated by the following statements:

“My challenge was feeling uncomfortable in my own clothes when I am in public. Always feeling like someone is judging me whenever I am walking which also diminishes my self-confidence. As a student I tend to feel uncomfortable when I have to do a presentation in front of my classmates. I feel like as I am standing in front of them they are judging how I look, and they can see right through me or something. It became very difficult to participant in group presentations or anything that will draw attention to myself’’’ (Participant 2).

“Bullying can negatively affect body image because individual may start believing what the bully says, those who are in larger bodies or those in smaller bodies tend to get bullied more often because of their appearances, I lost confidence in myself, always had this mind-set of looking perfect so no one would have anything negative to say. Sometimes, I would point out my flaws first before anyone else does, so as to avoid someone else doing it’’ (Participant 7).

“I didn’t want to go out, I always wanted to cover myself up because I felt like people will comment about my body. I think sometimes I wouldn’t want to be around people, because they would comment about my body. I sometimes didn’t want to attend classes because, I felt uncomfortable’’ (Participant 10).

3.2.2. Stress and Avoidance

The student reported stress and avoidance as a challenge they faced going through body image dissatisfaction. This is unveiled from the statements below:

“Well, there were days where I didn’t feel good about myself, I felt less confident in my own body, I would avoid attending classes because I didn’t look good and it really affected my studies and mental health, as it became stressful and exhausting’’ (Participant 1).

“I would sometimes avoid social interactions with other people because of fear of being judged. I would also restrict myself from doing activities when am with friends’’ (Participant 2).

‘’I didn’t feel like going out, I always wanted to cover myself up when I had to go out because I felt like people would judge me. I think sometimes I wouldn’t want to be around people because I thought they would comment about my body’’ (participant 10)

3.2.3. Anxiety

The participants reported that they experienced anxiety because of body image dissatisfaction, as they would experience continuous uneasiness and warry about their appearance. This is validated by the statements below

“I developed chronic stress and anxiety, I was always stressing and worrying, thinking that maybe I might be infected with HIV, as people were always surprised when I entered a room, I would feel like an alien or something. In my mind I thought the weight loss was an indication that I was infected by HIV. I was always worrying and had the fear of conducting an HIV test. I was not ready to face that, as my mind was already convinced I am sick, or something is actually wrong with me’’ (Participant 6).

“I didn’t feel like going out, I always wanted to cover myself up when I had to go out because I felt like people would judge me, I think sometimes I wouldn’t want to be around people, because I thought they would comment about my body. I sometimes didn’t want to attend classes because I felt uncomfortable, for me all these brought anxiety and most of the time I felt lonely, uneasy and sad’’ (Participant 10).

3.3. Coping Strategies Used by Female Students Experiencing Body Image Dissatisfaction

3.3.1. Acceptance

The majority of the participants suggested acceptance as the first step to coping with body image dissatisfaction, because without acknowledging that body image dissatisfaction is an issue for you, there is no way one can start coping or dealing with it. This is revealed by the following statements below:

“Accepting the way, I am and how I generally look, I begin regaining my confidence by falling in love with parts of my body that I did not like and also learning that people are unique and will never have the same body, skin and personality features. Love and accept yourself entirely, it worked for me, am sure if others tried, it might work for them as well and stop comparing yourselves to other peers it only makes things worse’’ (Participant 1).

“I live by the mantra love and appreciate yourself. Nobody can love you unconditionally than yourself. If you do not love yourself then you will never experience unconditional love. It’s okay to be thin, fat, short, or tall because that shows the beauty of creation. Our differences prove the intelligence of the almighty’’ (Participant 4).

‘’Acceptance is the key, accept what you can’t change, and your life will be a lot better. Stop entertaining other people’s comments about yourself. Focus on the positive rather than the negative and just accept yourself for who you are’’ (Participant 8).

3.3.2. Self-Care

The students revealed that listening to motivational video’s helped them cope with body image dissatisfaction. The statements below are evidence:

“Listening to motivational posts helps encourage one to be confident in their own body. I would watch the videos every day in the morning before I get ready for the day and at night before I sleep. These videos help me overcome negative body thoughts, they help me build my self-esteem and also teach me ways to stop obsessing over my body’’ (Participant 2).

“Affirm that your body is perfect just the way it is. Walk with your head high with pride and confidence in yourself as a person not a size. Replace the time you spend criticising your appearance with more positive satisfying pursuits. Accept that beauty is not just skin deep, it reflects your whole self so love and enjoy the person inside you and always remember to take care of yourself’’ (Participant 7).

“I used to watch videos on social media about thin girls and I would see other ladies who are of my boy size confidently speaking about their journey to accepting who they are, that actually motivated me. Accept and appreciate your own body. Take steps to care for your body and appearances in ways that feels healthy and fulfilling’’ (Participant 9).

3.3.3. Exercise and Healthy Dieting

The participants recommended exercising and having a healthy diet as a coping strategy students can use to deal with body image dissatisfactions. This is validated by the statements below:

“Exercise but do not do it because of pressure to achieve a certain body type, do it for fitness and mental health’’ (Participant 1).

“I have been doing certain activities to help lose weight such as exercising and maintaining a healthy balance diet’’ (Participant 2).

“Do not be hard on yourself, exercise and eat healthy, do not overdo it, just trust the process. The progress may be slow, and you might get tempted to test your limits and try harder, but you will only hurt yourself physically and emotional so trust the process no matter how slow it is. Accept the things you can’t change about yourself, and you will be fine’’ (Participant 5)

“Exercise if you feel like you want to lose some weight or be fit, just do not put too much pressure on yourself’’ (Participant 8).

4. Discussion

The current study found that body comparison is one of the major contributing factors leading to body image dissatisfaction among female students in universities. These findings are congruent with Laker and Waller (2019) who indicated that female students are more prone than male students to regularly compare themselves to others by evaluating their body type and weight in contrast to others. Lin and Soby (2016) found that female students who participate in comparisons are more likely to exhibit behaviours related to the drive for thinness and restrict their diets. Additionally, this study found that societal beauty standards are one of the causes of body image dissatisfaction among female students. According to the participant’s society beauty standards, means being slender, tall, have a flat tummy and be light in complexion, these are the unrealistic beauty standards. These findings are in consonance with Chiodo (2015) who states that the belief that physical attractiveness covers the most important attributes for women and that all women must take a positive action to achieve and maintain this attractiveness has been socially constructed as the ideal for feminine beauty. From an early age, girls are exposed to images of this ideal, and this consistent exposure lasts far into adulthood (GU, 2017). To appear immaculate and faultless, advertising convey the ideal of beauty (GU, 2017) as slender standard of beauty, frequently exhibiting flawless (or even unattainable) proportions, fair skin, and thick, luxurious hair. As a result, society is influenced by these images because individuals have started to accept them as normal and feel compelled to imitate the women in advertisements (GU, 2017). The present study found that one of the main causes of female students’ discontent with their bodies is social media. Similarly, Global Wed Index (2016) found that due to the necessity of social networking websites, 94% of young adults who use the internet actively utilize at least one account on these platforms, with an estimated daily usage time of 1.97 hours. Young adults utilize their social media presence to manage and edit how they present themselves to their peer networks. Expression of identity and peer acceptance appear to be more important and valuable than ever. Similarly, Holland and Tiggemann (2016) found that social media images that are beautiful and perfect can exacerbate issues with body image. Furthermore, participants indicated that the perfect body pictures they see on Facebook or Instagram contribute to their body image dissatisfaction. These findings are supported by Holland and Tiggemann (2016) who found that body image dissatisfaction is a social media phenomenon that can be linked to how much time a person spends on a platform. Research revealed that Facebook usage frequency among university students was positively correlated with body image issues (Fardouly & Vartanian, 2015). A recent study found that because Instagram has more picture-focused content than Facebook, spending seven minutes on Instagram had a larger negative impact on undergraduate females’ body image (Engel et al, 2020).

This study also revealed that friends and family members are some of the main causes of negative body image. Neumark-Seztainer et al. (2010) reported that when it comes to young people’s body image, the home and family environment play a significant role; both overt comments about weight and covert parental modelling may be harmful to teenagers. Consistent with the current study, family members’ negative interactions with one’s body, such as criticism, teasing, and involvement in diet, have been linked to the emergence of body image dissatisfaction (Hardit & Hannum, 2012). Bailey and Ricciardelli (2010) concluded that young women who hear negative comments about their weight tend to compare themselves negatively to others and are more likely to experience body image issues. The participants further indicated that hurtful comments made by family members and friends about their body image affects them more. These findings are supported by Christopher and Chukkali (2013) who found that peers and family members were the main target audiences for teasing, and it had an impact on how people felt about their bodies. Moreover, this study show that body image dissatisfaction affected participants self-confidence due to being body shamed when comparing themselves with others. In support of the present study Fortes, Cipriani, Coelho, Paes and Ferreira (2014) state that teenagers who lack confidence may experience feelings of worthlessness and failure and may be more likely to be unsatisfied with their weight, physical appearance and body shape. A negative body image frequently leads to diminishing self-esteem, lack of confidence, and an obsessive obsession with dieting behaviours (Good Therapy, 2015).

5. Conclusions

Body image is a person’s perception of their physical appearance and feelings that accompany it. Young female university students often worry about how they look. These worries frequently centre on the person’s weight, skin, form, or size of a particular bodily part. Many things, including society, social media, family, and friends, can affect how a person thinks about her body. This study showed that one of the main factors contributing to negative body image among university students is the practice of body comparison. Generally speaking, young people find it simpler to compare to the polished, idealized, and flawlessly presented image on social media because they may lack the social media literacy to recognize that what they are seeing is not a genuine reflection of reality or the way a person is truly feeling. Additionally, the extensive use of filters, digital modification, and the choice of the ideal video all contribute to presenting the reality that someone wants others to see; social media is a highlight reel and is never an accurate representation of every facet of someone’s life.

6. Limitations and Recommendations of the Study

The study lacked racial diversity, hence it was predominately made up of African participants and was not racially representative. Additionally, the results were dominated by participants from Christian religious affiliation which might have affected the results. Future studies on body dissatisfaction should consider diversity in terms of race and religiosity to yield rich knowledge of the phenomenon from different perspectives. Additionally, future studies may further pursue the same topic among homosexual students. Moreover, studying body image dissatisfaction among male university students may contribute significantly to the body of knowledge, as earlier studies have dwelled much on the fact that body dissatisfaction does not only affect girls, but boys are also affected.

The study was conducted using a small sample in relation to the number of female students enrolled in the University of Venda and the participants in the study were only female students. Hence, the findings cannot be generalised to all students or extended to wider population. Future research may take into account employing a bigger sample size or investigating students’ body dissatisfaction in various contexts or environments. Perhaps such a study can assess how students in urban and rural settings perceive body image dissatisfaction by comparing two institutes of higher learning in those two environments.

Author Contributions

A.F was involved in data collection and article write-up, CM was involved in article write-up, V.B. was involved in the protocol development and data analysis.

Acknowledgement

The authors appreciate all the students who took part in this study.

References

- Alfano, C.A.; Beidel, D.C. Social anxiety in adolescents and young adults: Translating developmental science into practice; American psychological Association: 2014. [CrossRef]

- Alleva, J.M.; Diedrichs, P.C.; Halliwell, E.; Martijn, C.; Stuijfzand, B.G.; Treneman-Evans, G.; Rumsey, N. A randomised-controlled trial investigating potential underlying mechanisms of a functionality-based approach to improving women’s body image. Body Image 2018, 25, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babbie, E.; Mouton, J. The Practise of Social Research; Oxford University Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bake, N. Focusing on college students’ Instagram use and body image. (Master of Science in Psychology), University of Rhode Island. 2018. Available online: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/theses/1243.

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chiodo, S. Ethical topicality of the ideal beauty. Leb. Aesthet. Philos. Exp. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, S.M.B.; Chukkali, S. Gender Differences: Perception of Teasing and Body Image among Youth Adults. Indian J. Health Wellbeing 2013, 4, 487–490. [Google Scholar]

- Compas, B.E.; Jaser, S.S.; Dunbar, J.P.; Watson, K.H.; Bettis, A.H.; Gruhn, M.A.; Williams, E.K. Coping and emotion regulation from childhood to early adulthood: Points of convergence and divergence. Aust. J. Psychol. 2013, 66, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, J.W. Research design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Method Research Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Duchesne, A.P.; Dion, J.; Lalande, D.; Begin, C.; Emond, C.; Lalande, G.; McDuff, P. Body dissatisfaction and psychological distress in adolescents: Is self-esteem a mediator? J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 1563–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engeln, R.; Loach, R.; Imundo, M.N.; Zola, A. Compared to Facebook, Instagram use causes more appearance comparison and lower body satisfaction in college women. Body Image 2020, 34, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, P.; Penelo, E.; Raich, R. Prevention programme for eating disturbances in adolescents. Is their effect on body image maintained at 30 months later? Body Image 2012, 10, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardouly, J.; Vartanian, L.R. Negative comparisons about one’s appearance mediate the relationship between Facebook usage and body image concerns. Body Image 2015, 12, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieldsted, P. 27 Body Positivity Quotes to Help You Embrace Your Body. Paigefieldsted.com. 2019.

- Firdevs, S.; Sevil, S. The impact of body image and self-esteem on Turkish adolescents’ subjective well-being. J. Psychol. Res. 2015, 5, 536–551. [Google Scholar]

- Forney, K.J.; Ward, R.M. Examining the moderating role of social norms between body dissatisfaction and disordered eating in college students. Eat. Behav. 2013, 14, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortes, L.D.; Cipriani, F.M.; Coelho, F.D.; Paes, S.T.; Ferreira, M.E. Does self-esteem affect body dissatisfaction levels in female adolescents? Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 2014, 32, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Web Index. Global Web Index Social report on the latest trends in social networking 1-11. 2016. Available online: http://insight.globalwebindex.net/social (accessed on 19 July 2017).

- Good Therapy. Goodtherapyorg. 2015. Available online: http://www.goodtherapy.org/learn-about-therapy/issues/body-image (accessed on 19 July 2017).

- Grossbard, J.R.; Neighbors, C.; Larimer, M.E. Perceived norms for thinness and muscularity among college students: What do men and women really want? Eat. Behav. 2011, 12, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grogan, S. Body image: Understanding body dissatisfaction in men, women and children; Taylor & Francis group; CRS Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- GU, A. The Representation of ideal Beauty in Advertising-A Longitudinal study of No. 7. 2017.

- Hardit, S.K.; Hannum, J.W. Attachment, the tripartite influence model, and the development of body dissatisfaction. Body Image 2012, 9, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmqvist, K.; Frisén, A. Body dissatisfaction across cultures: Findings and research problems. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2010, 18, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, G.; Tiggemann, M. A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image 2016, 17, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivezaj, V.; Saules, K.K.; Hoodin, F.; Alschuler, K.; Angalella, N.E.; Collings, A.S.; Wiedemann, A.A. The relationship between binge eating and weight status on depression, anxiety, and body image among a diverse college sample; A focus on bi/multiracial women. Eating Behav. 2010, 11, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemigisha, E.; Nyakato, V.N.; Bruce, K.; Ruzaaza, G.N.; Mlahagwa, W.; Nisiima, A.B.; Coene, G.; Leye, E.; Michielsen, K. Adolescents sexual wellbeing in Southwestern Uganda: A cross-sectional assessment of body image, self-esteem and gender equitable norms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 14, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laker, V.; Waller, G. The development of a body comparison measure: The CoSS. Eat. Weight. Disord. - Stud. Anorexia, Bulim. Obes. 2019, 25, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levnson, C.A.; Rodebought, T.L. Negative social-evaluative fears produce social anxiety, food intake and body dissatisfaction: Evidence of similar mechanisms through different pathways. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 3, 744–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Soby, M.E. Appearance comparisons styles and eating disordered symptoms in women. Eat. Behav. 2016, 23, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipson, S.K.; Jones, J.M.; Taylor, C.B.; Wilfley, D.E.; Eichen, D.M.; Fitzsimmons-Craft, E.E.; Eisenberg, D. Understanding and promoting treatment-seeking for eating disorders and body image concerns on college campuses through online screening, prevention and intervention. Eat. Behav. 2017, 25, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makwana, B.; Lee, Y.; Parkin, S.; Farmer, L. Selfie-esteem: The relationship between body dissatisfaction and social media in adolescent and young women. 2018.

- Mamabolo, M.P. Self-objectification, cultural, identity, body dissatisfaction, and health-related behaviours among female African university students, Mini-Dissertation. 2019.

- Marcus, R.; Harper, C.; Gender justice and social Norms-Processes of change for Adolescent Girls. London: Overseas Development Institute. 2014. Available online: www.odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/8831.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2014).

- Meier, E.P.; Gray, J. Facebook Photo Activity Associated with Body Image Disturbance in Adolescent Girls. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2014, 17, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, T.D.; Jensen, C.D.; Steele, R.G. Weight-related Criticism and Self-perceptions among Preadolescents. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2010, 36, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Bauer, K.W.; Friend, S.; Hannan, P.J.; Story, M.; Berge, J.M. Family weight talk and dieting: How much do they matter for body dissatisfaction and disordered eating behaviours in adolescent girls? J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2010, 47, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otakpor, A.N.; Ehimigbai, M. Body image perception and mental health of in-school adolescents in Bernini City. Niger. Postgrad. Med. J. 2016, 23, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, T.M.; Micklesfield, L.K.; Kahn, K.; Tollman, S.M.; Pettifor, J.M.; Norris, S.A. Body image satisfaction, Eating Attitudes and Perceptions of Female Body Sihouettes in Rural South African Adolescents. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevos, P. Differences in body image between men and women. Psychology 1A; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Puoane, T.R.; Fourie, J.M.; Tsolekile, L.; Nel, J.H.; Temple, N.J. What Do Black South African Adolescent Girls Think About Their Body Size? J. Hunger. Environ. Nutr. 2013, 8, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Råberg, M.; Kumar, B.; Holmboe-Ottesen, G.; Wandel, M. Overweight and weight dissatisfaction related to socio-economic position, integration and dietary indicators among South Asian immigrants in Oslo. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 13, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciardelli, L.A.; Yager, Z. Adolescence and society series. Adolescence and body image: From development to preventing dissatisfaction; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, G.; Tiggemann, M.; Mattiske, J. The role of media and peer influences in Australian women's attitudes towards cosmetic surgery. Body Image 2014, 11, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stalker, C.A.; Horton, S.; Cait, C. Single session therapy in walk-in counselling clinics: A pilot study of who attends and how they fare afterwards. J. Syst. Ther. 2012, 3, 38–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, D.Y.; Lu, B.D. Self-acceptance; concepts, measures and influences. Psychol. Res. 2017, 6, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshililo, R.A.; Netshikweta, L.M.; Tshitangano, G.T.; Nemathaga, H.L. Factors influencing weight control practices amongst the adolescent girls in Vhembe District of Limpopo Province, South Africa. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2016, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylka, T.L.; Wood-Barcalow, N.L. What is and what is not positive body image? Conceptual foundations and construct definition. Body Image 2015, 14, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.P. College Students’ Body Image and Interpersonal Disturbance: The Mediating Role of Self-Acceptance. Master’s Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, J.B.; Butler-Ajibade, P.; Robinson, S.A. Considering an affect regulation framework for examining the association between body dissatisfaction and positive body image in Black older adolescent females: Does body mass index matter? Body Image 2014, 11, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acknowledgement of Consulting Reviewers. Body Image 2014, 11, 188–189. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.B. A Research on the Relationship between Self-Acceptance and Social Anxiety: The Mediating Effect of Self-Esteem. Master’s Thesis, Human Normal University, Changsha, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhung, W.L. Mediating role of college students’ self-esteem between social anxiety and self-acceptance. Chin. J. Sch. Health 2016, 37, 1354–1357. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).