1. Introduction

Reversine is a small synthetic purine analog that has gained attention for its dual role in cellular dedifferentiation and inhibition of mitotic kinases [

1]. Initially identified as an agent capable of inducing dedifferentiation of committed cells into multipotent progenitor-like cells [

1], reversine has since been recognized for its inhibitory effects on aurora kinases, particularly aurora A and B, which are crucial regulators of mitosis [

2]. By targeting these kinases, reversine disrupts mitotic progression, leading to cytokinesis failure, polyploidization, and suppression of tumor cell proliferation [

3].

Aurora kinases, including

AURKA and

AURKB, are serine/threonine kinases that regulate chromosome segregation and cytokinesis during cell division [

4]. Overexpression of these kinases has been implicated in some cancers, including hematological malignancies [

5,

6,

7]. In chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), the

BCR-ABL oncoprotein upregulates

AURKA and

AURKB via the Akt signaling pathway, promoting leukemogenesis [

8]. Elevated expression of these kinases has been correlated with poor prognosis and resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), which are the standard treatment for CML [

9].

Several studies have demonstrated that reversine inhibits leukemia cell proliferation by targeting aurora kinases. Research on acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells found that reversine significantly reduced colony formation and induced apoptosis, while displaying lower toxicity toward healthy donor cells compared to other aurora kinase inhibitors such as VX-680 [

2,

9]. Additionally, reversine has been found to cause mitotic defects and polyploidization, resulting in the suppression of glioblastoma cells and other tumors [

10,

11]. Studies have also reported that reversine inhibits the proliferation of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) cells, supporting its potential as an anti-leukemic agent [

2,

12]. This selective cytotoxicity suggests that reversine may be a promising candidate for leukemia therapy, including in CML, where dysregulation of aurora kinases plays a role in disease progression [

13,

14].

Three-dimensional (3D) telomere analysis, performed using TeloView® software, enables quantitative assessment of the 3D telomere architecture by evaluating parameters such as telomere number, length, signal intensity, spatial distribution, and the presence of telomere aggregates [

15,

16]. In CML, abnormalities in telomere dynamics have been correlated with disease progression, with increased telomere aggregates and nuclear volume alterations being observed in advanced phases of the disease [

17]. Studies have shown that as CML progresses from the chronic phase to the blast crisis, there is a shift in telomere organization, which may be linked to genomic instability and resistance to therapy [

18].

Although direct studies on reversine’s impact on 3D telomere architecture in CML cells remain unknown, its role as an aurora kinase inhibitor suggests a potential influence on telomere maintenance. Aurora kinases regulate mitotic progression and chromosome segregation, both of which are crucial for telomere stability [

19,

20]. The inhibition of aurora kinases by reversine has been associated with mitotic defects, aneuploidy, and altered nuclear architecture, which could indirectly affect telomere integrity [

20].

In this newly conducted study, we proposed that reversine influences mitotic progression not only by inducing telomere dysfunction but also via its dedifferentiation action, which may promote a more plastic, progenitor-like state in cells. To explore this, we evaluated—for the first time—the effects of reversine on MEG-01 and K-562 chronic myeloid leukemia cells by analyzing changes in their 3D telomere architecture using TeloView® software before and after treatment. Furthermore, we examined the modulation of aurora kinase gene expression to assess reversine’s potential in restoring genomic stability.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

For this study, MEG-01 and K-562 cells, obtained from ATCC, were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. The cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO₂. To investigate the effects of reversine (Cayman Chemical: Based in Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA), a selective aurora kinase inhibitor, the compound was dissolved in DMSO to prepare a 10mM stock solution. Working concentrations of 5µM, 10µM, 20µM and 30µM were freshly prepared, and cells were treated for 24, 48 and 72 hours, with control groups receiving an equivalent amount of DMSO (<0.1% v/v).

2.2. Cytotoxicity Assessment and Cell Viability Analysis

To assess cytotoxicity, the viability of MEG-01 and K-562 cells was determined using the trypan blue exclusion assay and the MTT assay (Promega Corporation, Madison, USA). For the trypan blue assay, treated and control cells were stained with 0.4% trypan blue solution and counted using a hemocytometer. The MTT assay was performed by incubating the cells with MTT reagent (0.5 mg/mL) for four hours at 37°C, followed by the addition of DMSO to solubilize formazan crystals. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) was determined using non-linear regression analysis in GraphPad Prism 8 software.

2.3. Quantitative Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization (Q-FISH)

For evaluation of telomere architecture before and after reversine treatment, the cells were harvested and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Fixed cells were then placed onto poly-L-lysine-coated coverslips, and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (0.1 µg/mL) before being mounted with an antifade reagent. Telomere staining was performed using Cy3-labeled telomeric peptide nucleic acid (PNA) probes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham - Massachusetts, EUA), following a standard quantitative Fluorescence in situ Hybridization (Q-FISH) protocol. The hybridization process involved denaturation at 82°C for three minutes, followed by incubation at 30°C for two hours. Post-hybridization washes were carried out using SSC buffer and PBS to remove non-specific binding.

D Image Acquisition and Processing

Interphase nuclei from each sample were analyzed using an AxioImager M1 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) equipped with an AxioCam HRm charge-coupled device and a 63x oil objective lens (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Acquisition times were 500 milliseconds (ms) for Cy3 (telomeres) and 5 ms for DAPI (nuclei). Sixty z-stacks were captured at a sampling distance of x,y: 102 nm and z: 200 nm for each stack slice. Images were deconvolved and converted to TIFF files for 3D analysis using TeloView

® (Telo Genomics Corp., Toronto ON, Canada) software [

15,

16].

2.4. TeloView® Analysis and Statistics

To compare telomere architecture among treated samples, the TeloView

® software, proprietary to Telo Genomics, Toronto, Canada, was used [

15,

16]. TeloView

® measures six distinct parameters: (1) telomere length based on signal intensity, (2) the number of telomere signals per nucleus, (3) the number of telomeric aggregates (clusters of telomeres that cannot be resolved further at an optical resolution limit of 200 nm), (4) nuclear volume, (5)

a/c ratio (a spatial feature assessing cell cycle progression and proliferation), and (6) the spatial distribution of telomeres within the nuclear space, which reflects gene expression. Telomere dynamics were analyzed across cell cycle stages (G0/G1, S, and G2). Graphical representations were generated for subgroups of treated cells, illustrating telomere signal intensity, aggregate frequency, and signal distribution per cell. Telomeric parameters were compared among subgroups using analysis of variance, and their distributions were analyzed using chi-square tests. Average cell parameters were compared using nested factorial analysis of variance, accounting for both patient and cellular variations. A significant level of 0.05 was used for all tests.

2.5. Aurora Kinase mRNA Analysis

To investigate the modulation of AURKA and AURKB expression levels, after and before reversine treatment, quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed. Total RNA was extracted from treated and control cells using TRIzol® reagent, and RNA purity was confirmed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (260/280 ratio > 1.8). cDNA synthesis was carried out using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit. qPCR analysis was conducted using SYBR® Green Master Mix on an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System. Specific primers for AURKA (Hs00269212_m1) and AURKB (Hs00177782_m1) were used, with GAPDH as an endogenous control. The reaction conditions included an initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute. The relative expression levels of AURKA and AURKB were determined using the ΔΔCt method, with control samples serving as the reference group.

Statistical analysis of all experiments was performed using GraphPad Prism 8. Differences between control and treated groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc tests for multiple comparisons. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

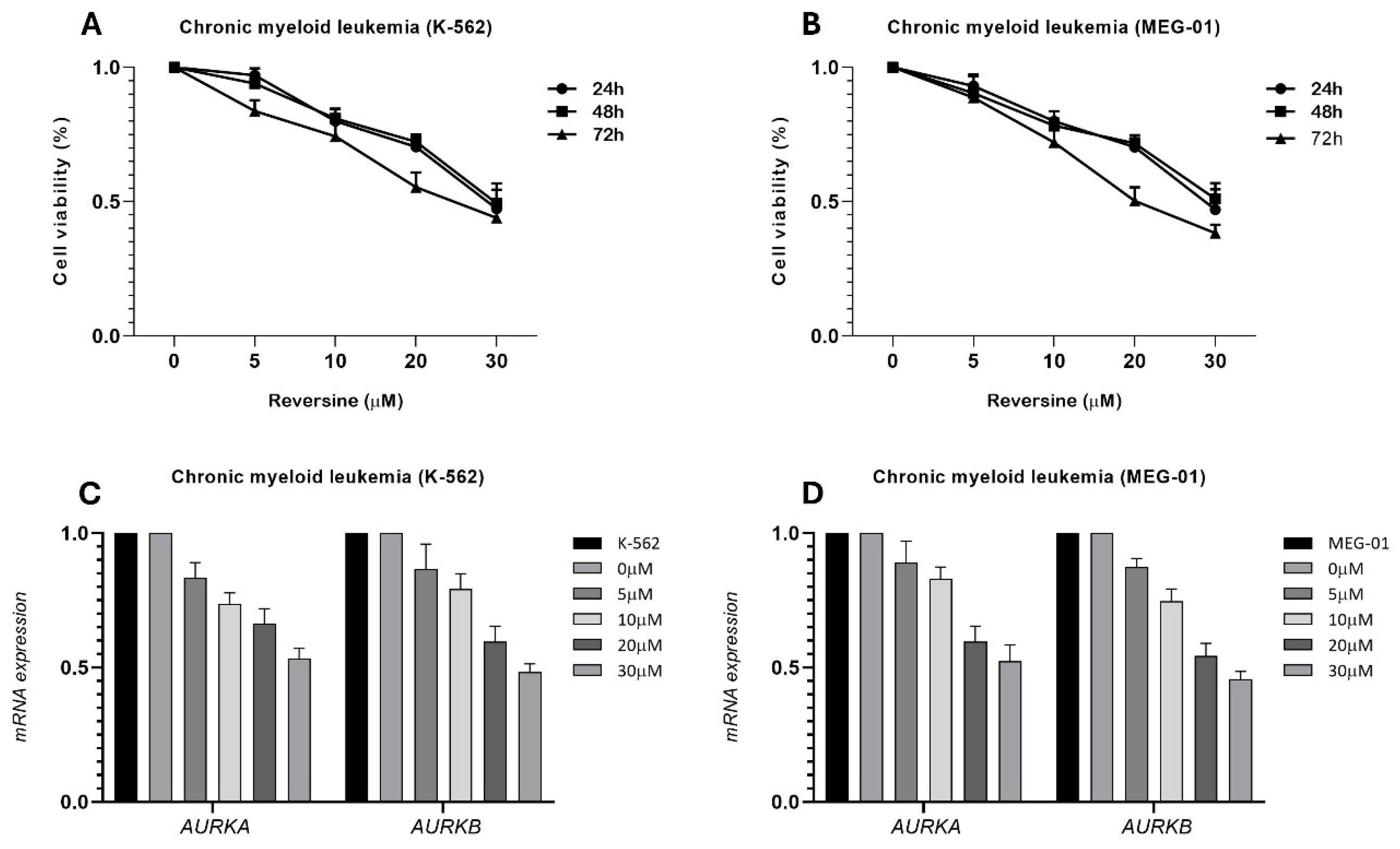

Our data demonstrate the effect of reversine on cell viability and gene expression in two chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) cell lines, K-562 and MEG-1, as expected, and in accordance with various studies published [

9,

10,

11]. The MTT assay results (

Figure 1A,B) reveal a dose- and time-dependent decrease in cell viability upon treatment with reversine. Across all tested concentrations (0, 5, 10, 20, and 30 μM), both cell lines exhibited a progressive reduction in viability, with the most pronounced effect observed at the highest concentration (30 μM). The inhibitory effect became more evident with increased exposure time, suggesting that reversine’s impact on cell viability intensifies over prolonged incubation periods. Notably, statistical analysis using ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-test confirmed a highly significant effect (p<0.0001), indicating strong reproducibility across independent experiments.

Additionally, qPCR analysis (

Figure 1C,D) assessed the relative expression levels of

AURKA and

AURKB mRNA after 24 hours of reversine treatment. The results indicate a concentration-dependent downregulation of both genes compared to the DMSO-treated control, which served as the calibrator. The decline in

AURKA and

AURKB expression suggests that reversine interferes with the transcriptional regulation of these mitotic kinases, which are known to be crucial regulators of cell cycle progression and survival in leukemia cells. This finding aligns with previous studies highlighting the role of

AURKA and

AURKB in maintaining proliferative capacity in cancer cells, supporting the hypothesis that reversine exerts its cytotoxic effects, at least in part, by disrupting their expression.

Together, this data provides strong evidence that reversine effectively impairs CML cell viability while modulating key mitotic regulators. The dose- and time-dependent trends observed in both assays underscore the potential of reversine as a targeted therapeutic agent against leukemia cells. The consistency between cell viability reduction and gene expression downregulation suggests a mechanistic link between reversine’s action and the inhibition of AURKA and AURKB, further reinforcing its potential as an anticancer agent.

For 3D telomere archtecture of CML cell lines (K-562 and MEG-01) we determined the IC₅₀ to ensure the preservation of viable cells, and phenotypic changes induced by reversine treatment. The IC₅₀ concentration was established at 28.8 µM for K-562 cells and 28.7 µM for MEG-01 cells. The assessment of telomere organization and structural parameters was conducted using TeloView® software [

15,

16], which enables a comprehensive evaluation of nuclear telomere distributions, aggregates, signal intensity, and nuclear volume in three-dimensional nuclear space. By employing TeloView®, it was possible to quantify key telomere features such as the total number of telomeres, telomere clustering (aggregates), intensity variations,

a/c ratio, and nuclear volume, providing a detailed depiction of how reversine alters nuclear architecture (

Table 1).

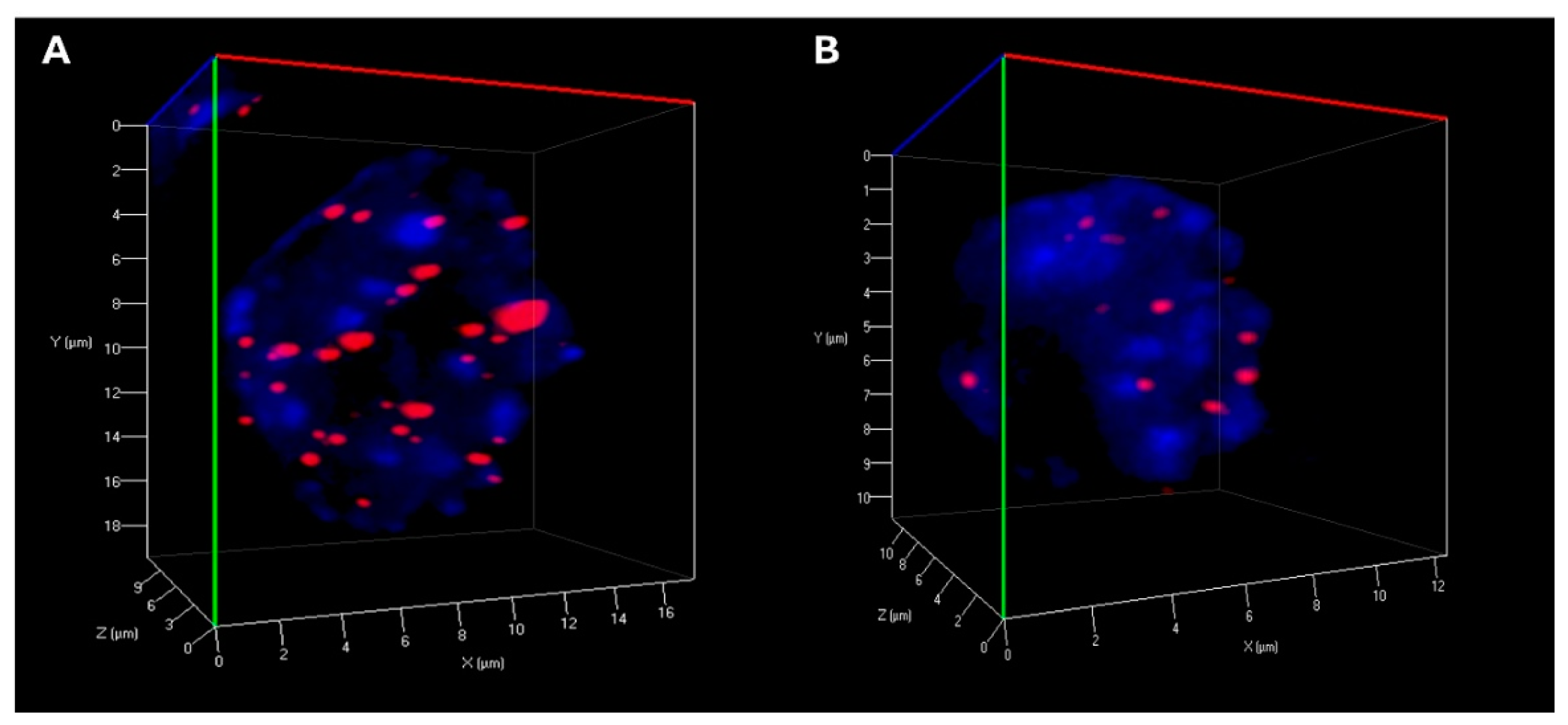

Statistical analysis revealed significant alterations in telomere organization following reversine exposure in CML cells. The total number of telomeres was markedly reduced, suggesting telomere reorganization, potentially reflecting decreased chromosomal instability. The number of telomere aggregates was also significantly lower in treated cells, indicating a disruption of telomere clustering, which may be linked to impaired chromatin architecture and genome stability (

Table 1) (

Figure 2). Furthermore, telomere signal intensity decreased significantly after reversine treatment, which could be indicative of telomere attrition, decompaction, or a reduction in telomeric DNA content (

Table 1). Moreover, the

a/c ratio, a critical parameter reflecting the spatial organization of telomeres and nuclear shape, exhibited significant modifications, suggesting a profound impact of reversine on nuclear integrity. Additionally, nuclear volume was markedly reduced in both K-562 and MEG-01 cells, reinforcing the hypothesis that reversine induces nuclear condensation and structural reorganization (

Table 1).

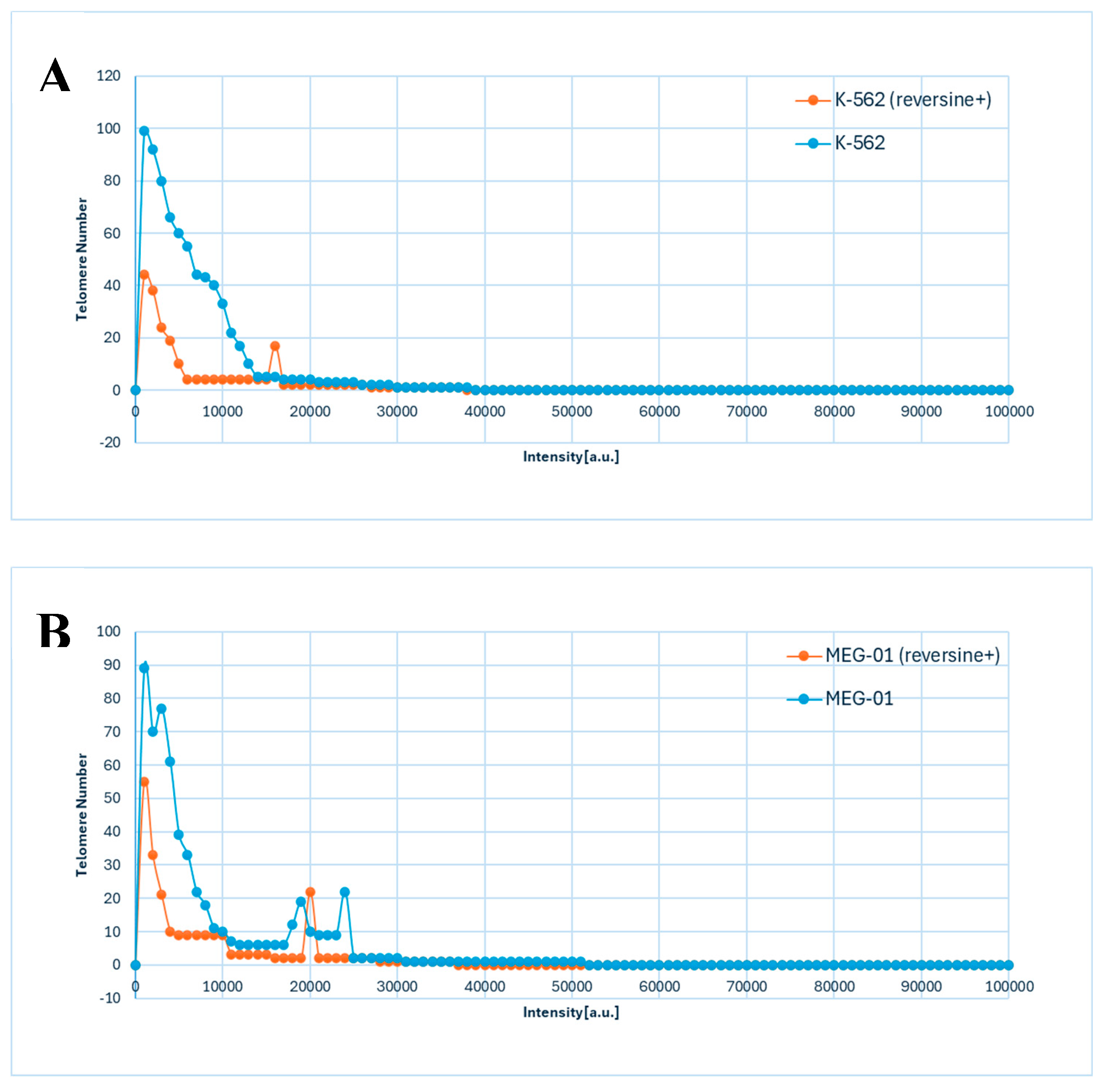

The data presented in

Figure 3A,B illustrated the distribution of telomere intensity, a parameter correlating with telomere length, in CML cells under distinct experimental conditions. The analysis included two CML cell lines, K-562 and MEG-01, each assessed in both untreated and reversine-treated states.

The graphical representation demonstrated a three-dimensional telomere profiling approach, capturing variations in telomere length distribution across the different conditions (

Figure 3A,B). In untreated cells, the telomere intensity distribution exhibited a characteristic pattern, indicative of a heterogeneous population with varying telomere lengths (

Figure 3A,B). Upon reversine treatment, shifts in this distribution were observed, suggesting an influence on telomere integrity or regulatory mechanisms governing telomere length maintenance.

Given the critical role of telomeres in genomic stability and cellular replicative capacity, the observed differences between treated and untreated cells provided insights into the molecular effects of reversine on telomere dynamics in CML. The distinct telomere distribution profiles between the K-562 and MEG-01 cell lines further implied intrinsic differences in telomere maintenance pathways, potentially linked to variations in cellular responses to therapeutic agents.

Utilizing three-dimensional telomere analysis via the TeloView® platform allowed for a more precise evaluation of telomere organization within the nuclear architecture. This detailed analysis not only linked reversine treatment to the inhibition of mitotic progression but also highlighted its role in inducing dedifferentiation. This advanced methodological approach allowed for the assessment of spatial distribution alongside telomere length heterogeneity, facilitating a comprehensive understanding of the impact of reversine on telomere biology in CML cells. These findings may have implications for therapeutic strategies targeting telomere-associated mechanisms in leukemia.

4. Discussion

The data presented in this study provide compelling evidence that reversine, a known aurora kinase inhibitor, significantly impacts the three-dimensional (3D) telomere architecture in CML cell lines, specifically K-562 and MEG-01. The observed alterations in telomere dynamics upon reversine treatment suggest a potential mechanism by which reversine exerts its antileukemic effects [

21,

22,

23].

Telomeres, the protective caps at the ends of chromosomes, play a crucial role in maintaining genomic stability. In CML, telomere dysfunction has been associated with disease progression and poor prognosis [

18]. Studies have demonstrated that as CML advances from the chronic phase to the blast crisis, there is a notable shortening of telomere length, which correlates with increased genomic instability [

24]. The current findings align with these observations, as reversine treatment resulted in significant changes in telomere length and organization, potentially reflecting a shift toward a less aggressive cellular phenotype [

15].

These findings align with reversine’s established dual role as both a cell dedifferentiation agent and a selective anticancer compound [

2,

24]. The literature suggests that reversine facilitates dedifferentiation by reprogramming lineage-committed cells into progenitor-like states, which involves chromatin remodeling and changes in nuclear organization [

22,

24]. The observed alterations in telomere structure in CML cells are consistent with this mechanism, as dedifferentiation is frequently associated with telomere instability and nuclear remodeling [

25,

26]. However, in cancer cells, this dedifferentiation process can also induce mitotic defects, chromosomal missegregation, and cell cycle perturbations, leading to apoptosis or cell cycle arrest [

16].

Interestingly, while dedifferentiation is often associated with increased cellular plasticity, reversine may contribute to telomere and chromatin stability in CML cells. This suggests the possibility of a reduced cytotoxic impact on surviving cells rather than necessarily driving a shift toward a less differentiated state. Additionally, the notable reduction in nuclear volume observed in this study could imply that reversine influences nuclear compaction, a phenomenon that is frequently linked to apoptosis or chromatin condensation resulting from mitotic arrest [

26]. Aurora kinases, particularly

AURKA and

AURKB, are pivotal regulators of mitosis and have been implicated in the pathogenesis of various malignancies, including CML [

12]. Overexpression of these kinases has been linked to enhanced tumor cell proliferation and survival [

13]. Reversine's inhibitory effect on Aurora kinases may disrupt mitotic progression, leading to mitotic defects and subsequent apoptosis in leukemic cells [

2,

7]. This mechanism is supported by studies showing that Aurora kinase inhibition can induce mitotic catastrophe and cell death in cancer cells [

8].

The significant decrease in telomere aggregates observed in this study suggests that reversine prevents telomere clustering, a feature typically associated with chromosomal integrity [

27]. Given the role of telomeres in genomic stability, the disruption of telomere clustering may contribute to mitotic defects and cellular stress, leading to a shift toward apoptosis rather than proliferation [

28].

To comprehensively analyze the effects of reversine on telomere dynamics, we utilized TeloView® software [

16,

17], an advanced imaging and analytical tool that enables high-throughput 3D telomere analysis. TeloView® quantitatively assesses telomere organization within interphase nuclei, measuring parameters such as total telomere number, telomere signal intensity, aggregate formation (clustering of telomeres),

a/c ratio (a measure of chromatin and cell cycle distribution), and nuclear volume. In cancer research, TeloView® has been instrumental in identifying telomeric signatures associated with genomic instability, disease progression, and response to therapy [

15,

16,

17,

18]. The present study demonstrated significant changes in telomere architecture after reversine treatment, as observed through a marked reduction in telomere aggregates, a decrease in overall telomere signal intensity, and alterations in nuclear volume, suggesting a potential role of reversine in modulating chromatin structure and telomere stability.

The clinical implications of these findings are significant. Targeting telomere dynamics and aurora kinase activity presents a promising therapeutic strategy in CML. Telomerase inhibitors have already shown potential in the treatment of myeloid malignancies [

29,

30,

31], and the addition of aurora kinase inhibitors like reversine could enhance therapeutic efficacy by simultaneously disrupting multiple pathways critical for leukemic cell survival [

32]. Moreover, the ability of reversine to induce changes in 3D telomere architecture may serve as a biomarker for treatment response, aiding in the stratification of patients and the optimization of therapeutic regimens.

In conclusion, this study underscores the multifaceted role of reversine in modulating telomere dynamics and Aurora kinase activity in CML cells. The integration of TeloView® for 3D telomere analysis provided valuable insights into the structural and functional changes induced by reversine, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic agent in the management of CML.