Submitted:

14 October 2024

Posted:

15 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Patients and Samples

Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS)

Whole Transcriptome Sequencing (WTS)

DEG Selection

Measuring the Length of Telomeres

Statistical Analysis

Results

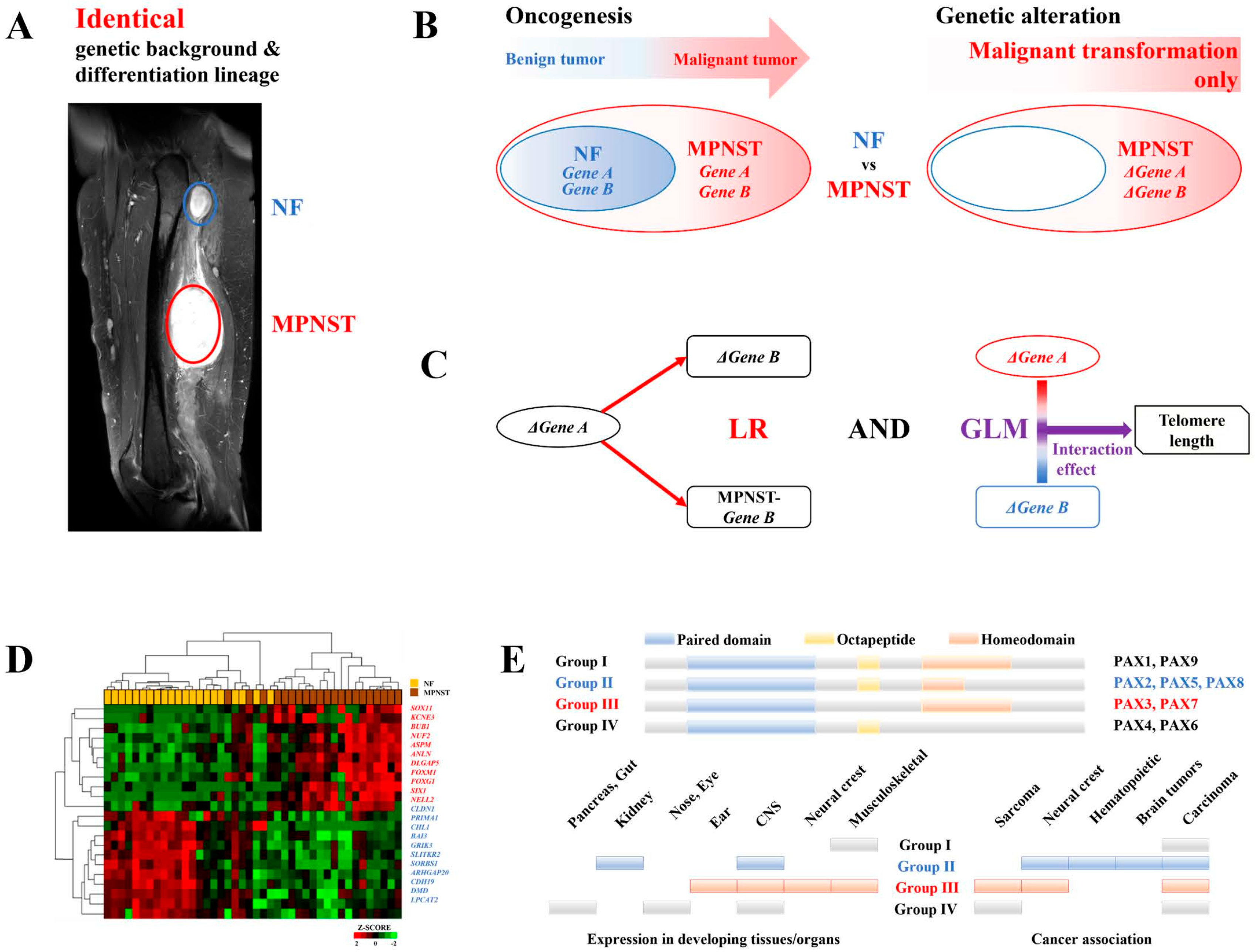

Differentially Expressed Genes during MPNST Malignant Transformation

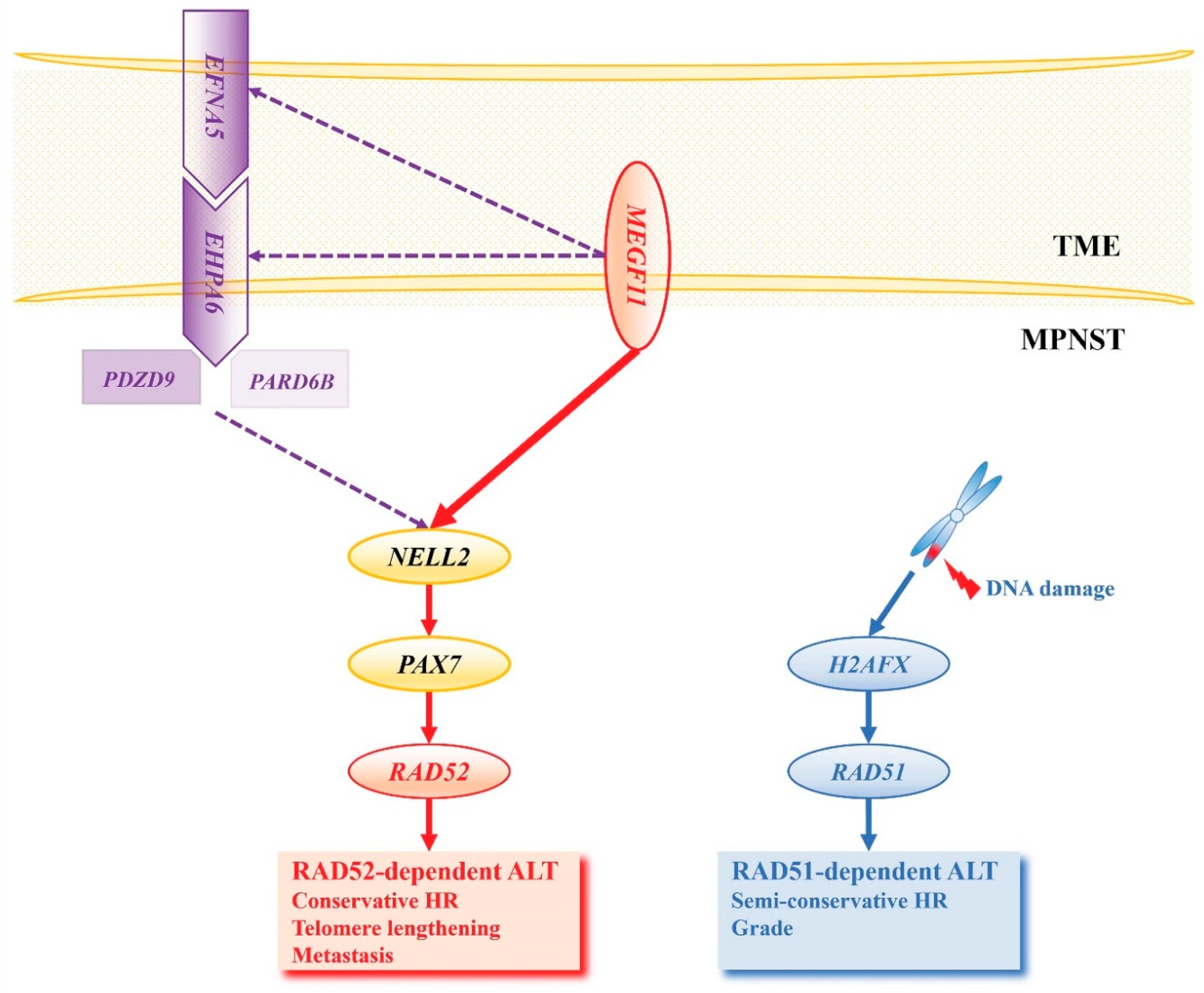

NELL2 Activates PAX7

PAX7 Activates RAD52-Dependent ALT and H2AFX Activates RAD51-Dependent ALT

MEGF11 Activates the NELL2-PAX7 Transcriptional Cascade

Ephrin Signaling Activates the NELL2-PAX7 Transcriptional Cascade in an MEGF11-Dependent Manner

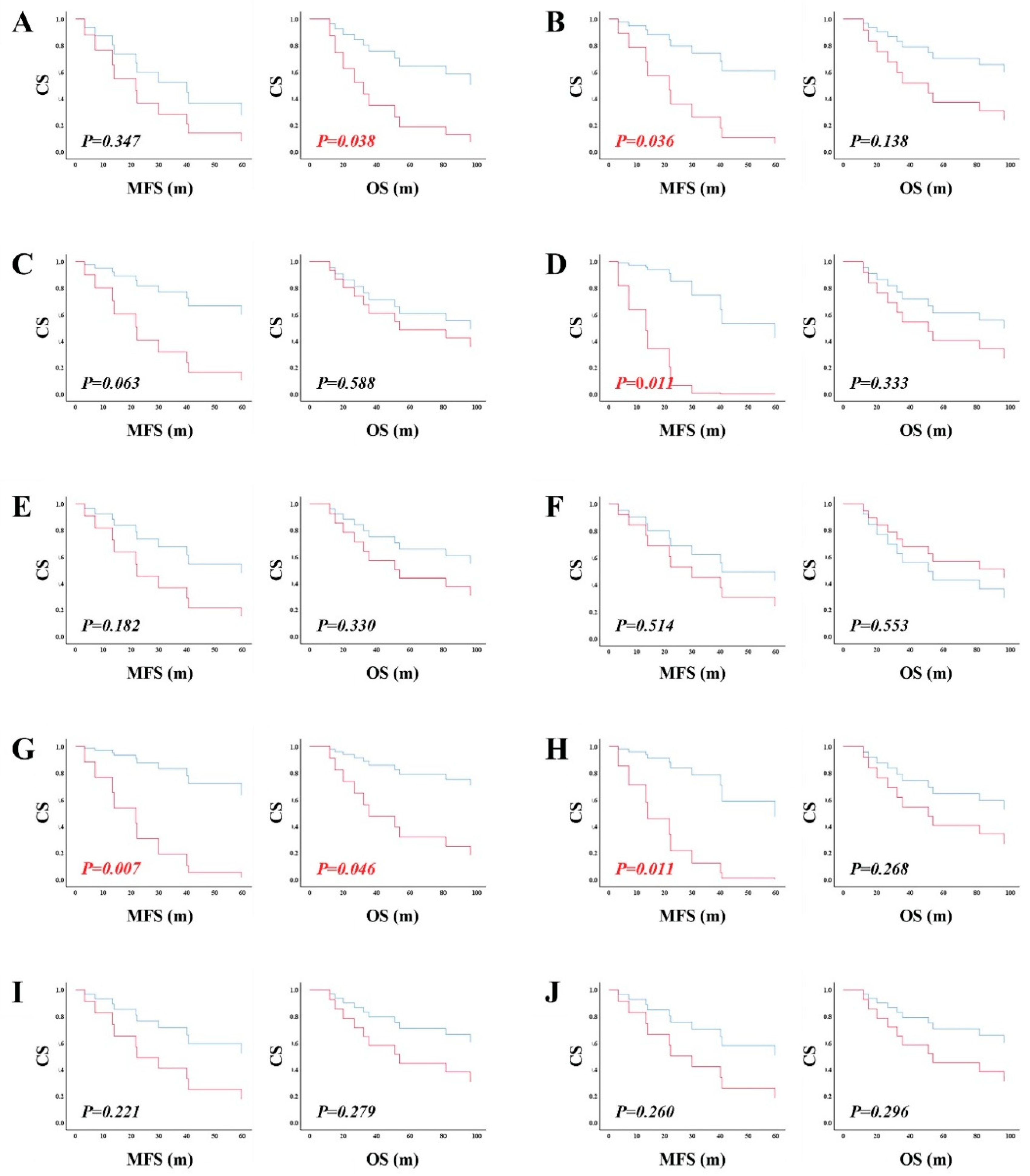

Biological and Clinical Manifestations of RAD51 and RAD52-Dependent ALT

Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Watson, J. D. Origin of Concatemeric T7DNA. Nature New Biology 239, 197-201 (1972). [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, R., Okazaki, T., Sakabe, K., Sugimoto, K. & Sugino, A. Mechanism of DNA chain growth. I. Possible discontinuity and unusual secondary structure of newly synthesized chains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 59, 598-605 (1968). [CrossRef]

- Hayflick, L. & Moorhead, P. S. The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res 25, 585-621 (1961). [CrossRef]

- Harley, C. B., Futcher, A. B. & Greider, C. W. Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts. Nature 345, 458-460 (1990). [CrossRef]

- Trojani, M. et al. Soft-tissue sarcomas of adults; study of pathological prognostic variables and definition of a histopathological grading system. Int J Cancer 33, 37-42 (1984). [CrossRef]

- Guillou, L. et al. Comparative study of the National Cancer Institute and French Federation of Cancer Centers Sarcoma Group grading systems in a population of 410 adult patients with soft tissue sarcoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology 15, 350-362 (1997). [CrossRef]

- Greider, C. W. & Blackburn, E. H. Identification of a specific telomere terminal transferase activity in tetrahymena extracts. Cell 43, 405-413 (1985). [CrossRef]

- Greider, C. W. & Blackburn, E. H. A telomeric sequence in the RNA of Tetrahymena telomerase required for telomere repeat synthesis. Nature 337, 331-337 (1989). [CrossRef]

- Chakravarti, D., Labella, K. A. & Depinho, R. A. Telomeres: history, health, and hallmarks of aging. Cell 184, 306-322 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Ghanim, G. E. et al. Structure of human telomerase holoenzyme with bound telomeric DNA. Nature 593, 449-453 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Cesare, A. J. & Reddel, R. R. Alternative lengthening of telomeres: models, mechanisms and implications. Nat Rev Genet 11, 319-330 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Shay, J. W. & Wright, W. E. Telomeres and telomerase: three decades of progress. Nat Rev Genet 20, 299-309 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Conomos, D., Pickett, H. A. & Reddel, R. R. Alternative lengthening of telomeres: remodeling the telomere architecture. 3 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Kramara, J., Osia, B. & Malkova, A. Break-Induced Replication: The Where, The Why, and The How. Trends in Genetics 34, 518-531 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Min, J., Wright, W. E. & Shay, J. W. Alternative Lengthening of Telomeres Mediated by Mitotic DNA Synthesis Engages Break-Induced Replication Processes. Mol Cell Biol 37 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. M., Yadav, T., Ouyang, J., Lan, L. & Zou, L. Alternative Lengthening of Telomeres through Two Distinct Break-Induced Replication Pathways. Cell Rep 26, 955-968.e953 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Summers, M. A. et al. Skeletal muscle and motor deficits in Neurofibromatosis Type 1. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 15, 161-170 (2015).

- Friedman, J. M. Epidemiology of neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Med Genet 89, 1-6 (1999).

- Venturini, L. et al. Telomere maintenance mechanisms in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: expression and prognostic relevance. Neuro-Oncology 14, 736-744 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, F. J. et al. Telomere alterations in neurofibromatosis type 1-associated solid tumors. Acta Neuropathologica Communications 7 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Cho, N. W., Dilley, R. L., Lampson, M. A. & Greenberg, R. A. Interchromosomal homology searches drive directional ALT telomere movement and synapsis. Cell 159, 108-121 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Bhowmick, R., Minocherhomji, S. & Hickson, I. D. RAD52 Facilitates Mitotic DNA Synthesis Following Replication Stress. Mol Cell 64, 1117-1126 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Sotiriou, S. K. et al. Mammalian RAD52 Functions in Break-Induced Replication Repair of Collapsed DNA Replication Forks. Mol Cell 64, 1127-1134 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Hoang, S. M. & O’Sullivan, R. J. Alternative Lengthening of Telomeres: Building Bridges To Connect Chromosome Ends. Trends in Cancer 6, 247-260 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Sobinoff, A. P. & Pickett, H. A. Alternative Lengthening of Telomeres: DNA Repair Pathways Converge. Trends in Genetics 33, 921-932 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Quail, D. F. & Joyce, J. A. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med 19, 1423-1437 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N. M. & Simon, M. C. The tumor microenvironment. Curr Biol 30, R921-r925 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Bader, J. E., Voss, K. & Rathmell, J. C. Targeting Metabolism to Improve the Tumor Microenvironment for Cancer Immunotherapy. Mol Cell 78, 1019-1033 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Li, F. et al. The BUB3-BUB1 Complex Promotes Telomere DNA Replication. Molecular Cell 70, 395-407.e394 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Pak, J. S. et al. NELL2-Robo3 complex structure reveals mechanisms of receptor activation for axon guidance. Nature Communications 11 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Jayabal, P. et al. NELL2-cdc42 signaling regulates BAF complexes and Ewing sarcoma cell growth. Cell Reports 36, 109254 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Li, M., Zhang, L., Chen, Y. & Zhang, S. m6A demethylase FTO induces NELL2 expression by inhibiting E2F1 m6A modification leading to metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer. Molecular Therapy - Oncolytics 21, 367-376 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. H. et al. Neural Epidermal Growth Factor-Like Like Protein 2 (NELL2) Promotes Aggregation of Embryonic Carcinoma P19 Cells by Inducing N-Cadherin Expression. PLoS ONE 9, e85898 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Kalathil, D., John, S. & Nair, A. S. FOXM1 and Cancer: Faulty Cellular Signaling Derails Homeostasis. Front Oncol 10, 626836 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Yu, J. et al. Array-Based Comparative Genomic Hybridization Identifies CDK4 and FOXM1 Alterations as Independent Predictors of Survival in Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor. Clinical Cancer Research 17, 1924-1934 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. et al. SOX11: friend or foe in tumor prevention and carcinogenesis? Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology 11, 175883591985344 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J. M. R. et al. PRIMA-1 Reactivates Mutant p53 by Covalent Binding to the Core Domain. Cancer Cell 15, 376-388 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Mlakar, V. et al. PRIMA-1MET-induced neuroblastoma cell death is modulated by p53 and mycn through glutathione level. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 38 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Jones, L., Naidoo, M., Machado, L. R. & Anthony, K. The Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene and cancer. Cellular Oncology 44, 19-32 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. & Cheng, B. MicroRNA miR-3646 promotes malignancy of lung adenocarcinoma cells by suppressing sorbin and SH3 domain-containing protein 1 via the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase signaling pathway. Bioengineered 13, 4869-4884 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Dahl, E., Koseki, H. & Balling, R. Pax genes and organogenesis. Bioessays 19, 755-765 (1997). [CrossRef]

- Li, C. G. & Eccles, M. R. PAX Genes in Cancer; Friends or Foes? Front Genet 3, 6 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Robson, E. J., He, S. J. & Eccles, M. R. A PANorama of PAX genes in cancer and development. Nat Rev Cancer 6, 52-62 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, M. & Relaix, F. The role of Pax genes in the development of tissues and organs: Pax3 and Pax7 regulate muscle progenitor cell functions. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 23, 645-673 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Kay, J. N., Chu, M. W. & Sanes, J. R. MEGF10 and MEGF11 mediate homotypic interactions required for mosaic spacing of retinal neurons. Nature 483, 465-469 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Chiu, J. H. et al. MEGF11 is related to tumour recurrence in triple negative breast cancer via chemokine upregulation. Sci Rep 10, 8060 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. P. et al. Overexpression of multiple epidermal growth factor like domains 11 rescues anoikis survival through tumor cells-platelet interaction in triple negative breast Cancer cells. Life Sci 299, 120541 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Osman, Y. et al. Functional multigenic variations associated with hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Lab Hematol 43, 1472-1482 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, A. L. et al. Comprehensive DNA methylation analysis of benign and malignant adrenocortical tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 51, 949-960 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Cicek, M. S. et al. Colorectal cancer linkage on chromosomes 4q21, 8q13, 12q24, and 15q22. PLoS One 7, e38175 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X., Larsson, C. & Xu, D. Mechanisms underlying the activation of TERT transcription and telomerase activity in human cancer: old actors and new players. Oncogene 38, 6172-6183 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Nersisyan, L., Simonyan, A., Binder, H. & Arakelyan, A. Telomere Maintenance Pathway Activity Analysis Enables Tissue- and Gene-Level Inferences. Front Genet 12, 662464 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Nersisyan, L. & Arakelyan, A. A transcriptome and literature guided algorithm for reconstruction of pathways to assess activity of telomere maintenance mechanisms (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 2017).

- Dyer, M. A., Qadeer, Z. A., Valle-Garcia, D. & Bernstein, E. ATRX and DAXX: Mechanisms and Mutations. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 7, a026567 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Potts, P. R. & Yu, H. The SMC5/6 complex maintains telomere length in ALT cancer cells through SUMOylation of telomere-binding proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14, 581-590 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Braun, D. M., Chung, I., Kepper, N., Deeg, K. I. & Rippe, K. TelNet - a database for human and yeast genes involved in telomere maintenance. BMC Genetics 19 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Feuerbach, L. et al. TelomereHunter - in silico estimation of telomere content and composition from cancer genomes. BMC Bioinformatics 20, 272 (2019). [CrossRef]

| NF | MPNST | P | |||

| Patient demographics | |||||

|

Age at diagnosis of MPNST (years, mean±SD)(Min-Max) |

36.55±14.58 (16–71) | - | |||

|

Sex n(%) |

male | 10(50.0) | - | ||

| female | 10(50.0) | - | |||

|

AJCC stage1 n(%) |

I | - | 4(20.0) | - | |

| II & IIIA | 10(50.0) | ||||

|

IIIB & IV (Metastatic) |

6(30.0) | ||||

|

Survival n(%) |

OS2 | - | 7(35.0) | - | |

| DOD | 10(50.0) | ||||

| DOC | 3(15.0) | ||||

|

Metastasis n(%) |

free | - | 4(28.6) | ||

| positive | 10(71.4) | ||||

| Tumor characteristics | |||||

| Size (cm, mean±SD) 3 | 5.31±5.57 | 7.44±3.49 | 0.430 | ||

|

MPNST histologic grade (FNCLCC) n(%) |

1 | - | 4(20.0) | - | |

| 2 | 6(30.0) | ||||

| 3 | 10(50.0) | ||||

|

Location4 n(%) |

visceral | 0(0) | 2(10.0) | 0.625 | |

| axial | 5(25.0) | 5(25.0) | |||

| extremity | 15(75.0) | 13(65.0) | |||

| Telomere length 5 (mean±SD) | 999.96±423.69 | 727.32±490.75 | 0.043 | ||

| NELL2 | PAX7 | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR | GLM | LR | GLM | ||||||||||||||

| Δ | MPNST | Δtelomere | MPNST-telomere | Δ | MPNST | Δtelomere | MPNST-telomere | ||||||||||

| β (95% CI) |

P | β (95% CI) |

P | β (95% CI) |

P | β (95% CI) |

P | β (95% CI) |

P | β (95% CI) |

P | β (95% CI) |

P | β (95% CI) |

P | ||

| TME | MEGF11 | 0.799 (0.393 to 1.206) |

0.001 | 0.648 (0.330 to 0.967) |

0.000 | 44.551 (19.987 to 69.115) |

0.000 | 45.525 (23.556 to 67.493) |

0.000 | 0.381 (0.188 to 0.575) |

0.001 | 0.383 (0.189 to 0.576) |

0.001 | 89.521 (30.653 to 148.388) |

0.003 | 98.580 (49.698 to 147.462) |

0.000 |

| EFNA5 | 0.106 (-0.421 to 0.633) |

0.676 | 0.283 (-0.115 to 0.681) |

0.152 | 45.446 (17.997 to 72.895) |

0.001 | 38.900 (16.027 to 61.773) |

0.001 | 0.201 (-0.031 to 0.433) |

0.085 | 0.203 (-0.029 to 0.435) |

0.083 | 97.010 (44.392 to 149.628) |

0.000 | 89.744 (48.726 to 130.963) |

0.000 | |

| RTK | EPHA6 | 0.918 (0.217 to 1.620) |

0.013 | 0.808 (0.275 to 1.341) |

0.005 | 57.328 (16.651 to 98.005) |

0.006 | 59.188 (21.406 to 96.970) |

0.002 | 0.499 (0.186 to 0.812) |

0.004 | 0.500 (0.187 to 0.813) |

0.004 | 106.112 (16.647 to 195.577) |

0.020 | 99.886 (15.346 to 184.425) |

0.021 |

| EPHB6 | 0.661 (-0.059 to 1.381) |

0.070 | 0.532 (-0.040 to 1.105) |

0.067 | 89.325 (44.439 to 134.211) |

0.000 | 81.525 (49.131 to 113.918) |

0.000 | 0.439 (0.131 to 0.747) |

0.003 | 0.441 (0.134 to 0.749) |

0.007 | 150.532 (70.277 to 230.787) |

0.000 | 122.220 (57.010 to 17.430) |

0.000 | |

|

PZD proteins |

PARD6B | 0.952 (0.105 to 1.799) |

0.030 | 0.551 (0.077 to 1.025) |

0.025 | 55.943 (13.061 to 98.824) |

0.011 | 68.916 (37.840 to 99.993) |

0.000 | 0.483 (0.088 to 0.878) |

0.019 | 0.485 (0.090 to 0.881) |

0.019 | 187.099 (75.124 to 299.075) |

0.000 | 214.738 (139.247 to 290.230) |

0.000 |

| PDZD9 | 0.919 (0.081 to 1.757) |

0.033 | 0.758 (0.097 to 1.419) |

0.027 | 96.366 (47.433 to 145.300) |

0.000 | 96.710 (67.185 to 126.235) |

0.000 | 0.539 (0.172 to 0.907) |

0.006 | 0.543 (0.175 to 0.910) |

0.006 | 192.099 (107.854 to 276.344) |

0.000 | 175.126 (117.298 to 232.954) |

0.000 | |

| ΔNELL2 | MPNST-NELL2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (95% CI) |

P | B (95% CI) |

P | |||

| Simple analysis | MEGF11 | 0.799 (0.393 to 1.205) |

0.001 | 0.648 (0.330 to 0.967) |

0.000 | |

| EPHA6 | 0.918 (0.217 to 1.620) |

0.013 | 0.808 (0.275 to 1.341) |

0.005 | ||

| PARD6B | 0.952 (0.105 to 1.799) |

0.003 | 55.943 (13.061 to 98.824) |

0.011 | ||

| PDZD9 | 0.919 (0.081 to 1.757) |

0.033 | 0.758 (0.097 to 1.419) |

0.027 | ||

| Multiple analysis | MEGF11 | MEGF11 | 1.059 (0.219 to 1.899) |

0.016 | 0.705 (0.038 to 1.373) |

0.039 |

| EPHA6 | -0.440 (-1.677 to 0.798) |

0.464 | -0.097 (-1.080 to 0.886) |

0.838 | ||

| MEGF11 | 0.697 (0.217 to 1.117) |

0..007 | 0.657 (0.273 to 1.041) |

0.002 | ||

| PARD6B | 0.338 (-0.482 to 1.158) |

0.396 | -0.029 (-0.685 to 0.626) |

0.926 | ||

| MEGF11 | 1.053 (0.346 to 1.760) |

0.006 | 0.836 (0.280 to 1.391) |

0.006 | ||

| PDZD9 | -0.523 (-1.712 to 0.666) |

0.666 | -0.386 (-1.319 to 0.547) |

0.395 | ||

| EHPA6 | EPHA6 | 0.665 (-0.255 to 1.585) |

0.145 | 0.853 (0.138 to 1.567) |

0.022 | |

| PARD6B | 0.460 (-0.605 to 1.526) |

0.375 | -0.081 (-0.909 to 0.746) |

0.839 | ||

| EHPA6 | 0.735 (-0.403 to 1.873) |

0.191 | 0.731 (-0.136 to 1.599) |

0.093 | ||

| PDZD9 | 0.270 (-1.028 to 1.568) |

0.666 | 0.113 (-0.877 to 1.102) |

0.813 | ||

| PARD6B | PARD6B | 0.619 (-0.415 to 1.652) |

0.224 | 0.154 (-0.694 to 1.002) |

0.706 | |

| PDZD9 | 0.566 (-0.451 to 1.583) |

0.257 | 0.670 (-0.165 to 1.504) |

0.109 | ||

| Telomere length1 | MPNST grade2 | Metastasis3 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δtelomere | MPNST-telomere | Simple analysis | Multiple analysis | Simple analysis | Multiple analysis | ||||||||

| B (95% CI) |

P | B (95% CI) |

P | OR (95% CI) |

P | OR (95% CI) |

P | HR (95% CI) |

P | HR (95% CI) |

P | ||

| Telomere length | Δtelomere | - | - | - | - | 1.250 (0.205 to 7.615) |

0.809 | 1.987 (0.552 to 7.151) |

0.293 | - | - | ||

| MPNST-telomere | - | - | - | - | 1.000 (0.998 to 1.002) |

0.822 | 1.001 (0.999 to 1.002) |

0.427 | - | - | |||

| TME-NELL2-PAX7 cascades | MEGF11 | -0.045 (-0.144 to 0.054) |

0.351 | 46.390 (-48.090 to 140.869) |

0.315 | 1.174 (0.807 to 1.706) |

0.402 | 1.161 (0.920 to 1.464) |

0.208 | ||||

| EHPA6 | -0.069 (-0.216 to 0.078) |

0.334 | 54.320 (-87.270 to 195.911) |

0.429 | 1.355 (0.768 to 2.393) |

0.295 | 1.212 (0.881 to 1.667) |

0.237 | |||||

| PARD6B | 25.699 (-157.424 to 208.822) |

0.771 | 64.970 (-96.681 to 226.621) |

0.408 | 1.317 (0.698 to 2.487) |

0.395 | 1.372 (0.835 to 2.254) |

0.212 | |||||

| PDZD9 | -0.037 (-0.205 to 0.130) |

0.644 | 137.892 (-7.571 to 283.355) |

0.062 | 2.389 (0.839 to 6.797) |

0.103 | 1.394 (0.889 to 2.187) |

0.148 | |||||

| NELL2 | -0.021 (-0.108 to 0.067) |

0.622 | 18.480 (-65.203 to 102.164) |

0.647 | 0.979 (0.718 to 1.333) |

0.891 | 1.174 (0.918 to 1.501) |

0.202 | |||||

| PAX7 | -0.066 (-0.050 to 0.118) |

0.459 | 78.778 (-95.795 to 253.351) |

0.354 | 1.498 (0.740 to 3.033) |

0.262 | 2.369 (1.269 to 4.423) |

0.007 | 2.132 (1.046 to 4.343) |

0.037 | |||

| RAD52 | 0.016 (-0.098 to 0.130) |

0.768 | 114.894 (22.996 to 206.793) |

0.017 | 1.318 (0.829 to 2.097) |

0.243 | 1.471 (1.059 to 2.043) |

0.021 | 1.174 (0.793 to 1.738) |

0.424 | |||

| DNA damage signal | H2AFX | -0.013 (-0.151 to 0.125) |

0.844 | -5.346 (-137.516 to 126.824) |

0.933 | 2.064 (1.007 to 4.229) |

0.048 | 1.714 (0.806 to 3.647) |

0.162 | 1.226 (0.809 to 1.857) |

0.337 | ||

| RAD51 | -0.054 (-0.145 to 0.037) |

0.225 | 19.255 (-71.309 to 109.818) |

0.659 | 1.529 (0.968 to 2.416) |

0.069 | 1.309 (0.757 to 2.266) |

0.336 | 1.312 (0.947 to 1.818) |

0.102 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).