1. Introduction

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs) are rare and highly aggressive sarcomas of Schwann cell lineage, accounting for 5–10% of all soft tissue sarcomas [

1]. Their estimated incidence is 1.46 cases per million individuals, most frequently affecting young to middle-aged adults and strongly associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) [

2,

3]. Despite advances in genetic and molecular profiling, MPNSTs remain therapeutically challenging, with limited response to surgery, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy. Infiltrative growth, perineural extension, and leptomeningeal dissemination contribute to the poor prognosis, and in intracranial or unresectable cases, median survival often falls below five months [

4]. These clinical features underscore the urgent need to better understand the cellular and microanatomical mechanisms that support MPNST invasion.

One underexplored aspect of MPNST biology is the role of perivascular (Virchow–Robin) spaces (PVS). These fluid-filled extensions of the subarachnoid space accompany penetrating vessels into the brain parenchyma, forming dynamic conduits for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), interstitial fluid exchange and immune surveillance [

5]. Beyond their physiological roles in glymphatic clearance and neuroinflammation [

6], PVS serve as permissive routes for tumor cell migration, with the structural continuity between leptomeninges, vasculature, and perivascular astrocytic endfeet creating specialized microenvironments that malignant cells can exploit.

The tumor microenvironment (TME) plays a pivotal role in MPNST progression. It includes Schwann cells, fibroblasts, endothelial and perineural cells, mast cells, extracellular matrix proteins, and a diverse immune infiltrate [

7]. Among these, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are predominant immune cell population, often polarizing toward immunosuppressive and pro-tumoral phenotypes that enhance invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis [

8,

9]. In parallel a subset of tumor cells with stem-like properties, the so-called cancer stem-like cells (CSLCs), arise from neural crest–derived Schwann cell precursors, contribute to tumor heterogeneity, therapeutic resistance, and recurrence [

10]. In MPNSTs, these CSLCs express canonical stemness-associated markers such as Prominin-1 (CD133), Octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (Oct4), and nestin [

11,

12].

Nestin, a class VI intermediate filament protein, plays a pivotal role in the biology of MPNSTs [

13]. While normally expressed in neural progenitor cells, nestin is markedly upregulated in these tumors, paralleling its association with malignancy in other brain neoplasms such as gliomas and supporting its function as a marker of aggressive behavior [

14]. This protein facilitates the establishment of the perivascular niche, promotes tumor cell proliferation, and enhances resistance to hypoxic stress through HIF-1α–mediated signaling pathways [

15,

16,

17]. Notably, nestin-positive cancer stem-like cells (nestin

+ CSLCs) frequently cluster around blood vessels, suggesting that perivascular regions may serve as reservoirs of stemness and sites that foster invasive potential [

18,

19]. Complementing this observation, butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE), an enzyme associated with neurogenesis and oncogenic transformation [

20,

21,

22], has also been implicated in tumor biology. In our previous work, BuChE expression was detected in perivascular tumor aggregates in a glioma rat model, suggesting its potential role as a histochemical marker of these niches [

23].

Despite significant progress in defining the molecular landscape of MPNSTs, including mutations in NF1, TP53, and ERBB2 [

2,

3], the cellular pathways underpinning intracranial dissemination remain poorly understood [

24]. Animal models provide essential platforms to dissect these mechanisms. Prenatal exposure to N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) in rodents recapitulates human MPNST histopathology, genetic alterations, and invasive behavior, enabling systematic analysis of tumor–microenvironment interactions [

25,

26].

In this study, we investigate the spatial interplay between nestin⁺ CSLCs, TAMs, and reactive astrocytes in perivascular compartments of ENU-induced rat MPNST. Using histological, immunohistochemical, and lectin-based approaches, we demonstrate that CSLCs exploit PVS for directional invasion, while TAMs and astrocytes define a permissive glial–immune microenvironment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

In accordance with the 3Rs principles (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) [

27], a subgroup of 74 rats from a previous study [

28] was re-analyzed. In that study, six pregnant Sprague–Dawley rats received a single intraperitoneal injection of N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU; 80 mg/kg, Sigma-Aldrich, Ref. E2129) on gestational day 15. Their 74 offspring were raised for 6–9 months under standard housing conditions (22 ± 1 °C, 55 ± 5% humidity, 12:12 h light/dark cycle) with food and water provided ad libitum. All procedures complied with EU Directive 2010/63/EU and Spanish legislation (RD 53/2013) and were approved by the UPV/EHU Animal Ethics Committee (Ref. CEEA/82b/2010/LAFUENTESANCHEZ).

2.2. Tumor Screening and Tissue Processing

MPNSTs were identified by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI; 4.7 T BIOSPEC BMT 47/40, Bruker) at ICTS BioImagen Complutense (BioImac). Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane (4% for induction, 2% for maintenance) and administered gadolinium-DTPA (1.5 mL/kg, i.v.) prior to acquisition of T1-weighted coronal and sagittal sequences (TR/TE = 700/15 ms). Image analysis was performed using Fiji software (ImageJ v2.14.0, NIH).

After tumor detection, rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital (60 mg/kg, i.p.) and transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). Brains and trigeminal nerves were extracted and post-fixed overnight in the same fixative, then either paraffin-embedded or cryoprotected in 30% sucrose. Coronal sections (4 µm for paraffin, 60 µm for cryosections) were obtained using a Leica HM325 rotary microtome and an HM430 freezing microtome, respectively.

2.3. Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed for histopathological evaluation of MPNSTs, including spindle cell morphology, mitotic figures, necrosis, hemorrhage, and microvascular proliferation.

Immunophenotypic characterization was conducted using the avidin–biotin complex method (Elite Vectastain ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories) with antibodies against Ki-67, EMA, SYP, S-100, NF, EGFR, and TP53 (

Table 1). Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), astrocytes, and cancer stem-like cells (CSLCs) were labeled with Iba-1, GFAP, and nestin antibodies. Paraffin sections (4 µm) were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and subjected to antigen retrieval (citrate or trypsin), followed by incubation with primary antibodies, biotinylated secondary antibodies, and ABC-peroxidase. Immunoreactivity was visualized with diaminobenzidine (DAB) and counterstained with hematoxylin. Negative controls omitted the primary antibodies.

Double immunofluorescence was performed to analyze perivascular dissemination and associated cellular components. Microvasculature was visualized using Lycopersicon esculentum lectin conjugated to FITC (LEA-FITC; 1:100, Sigma-Aldrich). Sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with a cocktail of primary antibodies (Iba-1, GFAP, and nestin), followed by Alexa Fluor–conjugated secondary antibodies (Alexa 488, 568, and 647; 1:400, Invitrogen). Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258. Images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM800 confocal microscope (SGIker Microscopy Facility, UPV/EHU, Leioa, Spain) and analyzed with ImageJ v2.14.0 (NIH) using standardized calibration and processing workflows.

2.4. Histochemistry

Free-floating coronal sections (60 µm) were processed for butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE) histochemistry as previously described [

29]. Briefly, sections were preincubated for 20 min with BW284C51 (0.05 M) to inhibit acetylcholinesterase activity and incubated overnight at room temperature in a reaction mixture containing butyrylthiocholine iodide (1 mg/mL), sodium citrate (5%, 0.1 M), copper sulfate (10%, 30 mM), BW284C51 (10%, 0.05 mM), potassium ferricyanide (10%, 5 mM), and Tris-maleate buffer (65%, 0.1 M, pH 6.0). The following day, sections were rinsed, mounted on gelatin-coated slides, dehydrated in graded ethanol, cleared in xylene, and coverslipped with mounting medium.

2.5. Labelling Index Quantification

In 25 representative MPNST samples (see

supplementary Table S1), tumor proliferative activity and TAM density were quantified using Ki-67 and Iba-1 immunolabeling indices (LI). Positive cells were counted as a percentage of 400 tumor cells within the areas showing the highest immunoreactivity, using a field size of 62,500 µm² at ×400 magnification. Only isolated immune-positive cells not associated with vascular structures were included. All quantifications were performed by a single blind observer to minimize variability.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 29.0 (IBM, Spain). Normality and variance homogeneity were assessed with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Levene’s tests. Group differences were evaluated using one-way ANOVA with appropriate post hoc tests, and Student’s t-test for pairwise comparisons. Correlations between tumor proliferation and TAM density were examined using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Data are presented as mean ± SD, and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Imaging and Histopathological Features of Basal and Convexity ENU-Induced MPNSTs

Among 74 ENU-exposed rats (36 females, 38 males), 33.7% developed MPNSTs, with a slight male predominance (M: F 1.3:1) and peak incidence at 6–7 months (

Table 2). MRI revealed enhancing tumors arising from the trigeminal (Gasserian) nerve root, extending along the meningeal sheath and disseminating through subarachnoid and perivascular spaces toward cortical convexities, interhemispheric fissure, and penetrating vessels, causing cortical compression and midline shift (

Figure 1A,B).

Histologically, 17 of 25 analyzed tumors showed basal brain dissemination, characterized by high cellularity, marked pleomorphism, frequent mitoses, hemorrhage and occasionally entrapping Schwann cells (

Figure 1C and

Figure 2A,B). Basal tumors exhibited focal S-100 expression (

Figure 1E and

Figure 2C), strong synaptophysin (

Figure 2D), moderate Ki-67 labeling (

Figure 2E), and scattered p53-positive nuclei (

Figure 2F).

In contrast, eight convexity tumors extended into the interhemispheric fissure and Virchow–Robin spaces, displaying lower cellularity, spindle-shape morphology, rare mitoses, nuclear palisading, and dilated vessels (

Figure 1D and

Figure 2G,L), with diffuse S100 staining (

Figure 1F and

Figure 2J). moderate Ki-67 labeling (

Figure 2K), and low p53 positivity (

Figure 2L). Nestin was consistently expressed in both regions (

Figure 1G,H), whereas GFAP, NF, EMA, EGFR, and NSE were negative. Overall proliferative activity, assessed by Ki-67, was 16.3% ± 8.6%, higher in basal tumors (18.5% ± 8.9%) than in convexity lesions (13.2% ± 7.02%) but not statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Clinically, tumor growth resulted in obstructive hydrocephalus, brainstem and cranial nerve involvement, and extensive leptomeningeal spread, contributing to elevated intracranial pressure and global brain distortion.

3.2. BuChE Expression Highlights Perivascular and Leptomeningeal Invasion

In ENU-induced MPNSTs, BuChE histochemistry revealed markedly elevated enzymatic activity, highlighting regions enriched in nestin⁺ cancer stem-like cells (CSLCs) compared to adjacent brain parenchyma. Coronal sections demonstrated extensive infiltration of BuChE⁺ tumor cells originating at the brain base and advancing along the subarachnoid space and meningeal sheath toward the interhemispheric fissure, with contralateral dissemination evident (

Figure 3A). At higher magnification, dense clusters of BuChE⁺ cells occupied perivascular spaces surrounding penetrating cortical vessels (

Figure 3B), while fibrillar aggregates in leptomeningeal compartments formed elongated, finger-like projections consistent with directional, stem cell–driven invasion (

Figure 3C). These observations indicate that CSLCs actively mediate intracranial perivascular and leptomeningeal dissemination, exploiting anatomical corridors as invasive niches.

3.3. Perivascular Infiltration of Nestin⁺ Cancer Stem-Like Cells and Glial–Immune Interactions

Iba-1 immunohistochemistry revealed abundant tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) within the subarachnoid space of ENU-induced MPNSTs, with a mean labeling index of 14.4 ± 5.8%. TAM density was higher in basal tumors (16.5 ± 5.8%) than in cortical lesions (11.0 ± 4.4%), although this difference was not statistically significant (

p > 0.05). TAM density positively correlated with proliferative activity (Ki-67 labeling index;

r = 0.574,

p = 0.003, Pearson’s correlation), suggesting a functional association with tumor growth (

Figure S1). Morphological analysis revealed location-specific heterogeneity: amoeboid TAMs predominated within tumor cores, intermediate forms were observed along arachnoid and pia mater, and ramified microglia indicative of a resting state were present in adjacent non-tumoral parenchyma (

Figure 4). This functional specialization emphasizes the role of TAMs in modulating CSLC-mediated invasion within perivascular and leptomeningeal niches.

Confocal microscopy further demonstrated that nestin⁺ CSLCs accumulated along vascular walls and formed perivascular aggregates, which were closely bordered by GFAP⁺ reactive astrocytes at the glia limitans and enriched with short-ramified Iba-1⁺ TAMs intermingled with hyperreactive astrocytic processes (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6A,B). In deeper cortical regions, CSLCs concentrated at perivascular invasive fronts, creating a coordinated glial–immune interface that delineated the advancing tumor edge. Individual nestin

+ CSLCs occasionally breached the astrocytic barrier, infiltrating adjacent parenchyma while remaining partially enclosed within a dual protective layer composed of inner GFAP⁺ astrocytes and outer Iba-1⁺ TAMs (

Figure 6C,D).

Collectively, these findings highlight that CSLCs mediate intracranial perivascular and leptomeningeal dissemination, orchestrating a dynamic interplay with TAMs and reactive astrocytes that promotes directional invasion, local immune modulation, and niche conditioning. This CSLC–TAM–astrocyte crosstalk establishes a permissive microenvironment that mirrors pre-metastatic niches described in other CNS malignancies and underscores the potential of targeting these cellular interactions to limit MPNST progression.

4. Discussion

In ENU-induced rat model of intracranial malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs), perivascular (Virchow–Robin) and leptomeningeal compartments emerge as preferential routes for tumor dissemination from the trigeminal root into the brain. These anatomical corridors represent permissive niches enriched in nestin⁺ cancer stem-like cells (CSLCs) and Iba-1⁺ tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), forming a coordinated microenvironment that promotes invasion and tumor progression.

Tumor proliferation was significantly higher at the primary trigeminal root site compared with distant cortical lesions, underscoring the influence of local tissue architecture and microenvironmental cues on growth dynamics. Histologically, neoplastic cells infiltrated Virchow–Robin spaces and subarachnoid routes, occasionally breaching the glia limitans to colonize adjacent parenchyma, a pattern reminiscent of leptomeningeal dissemination observed in high-grade gliomas, ependymomas, and metastatic carcinomas [

30,

31]. Impaired cerebrospinal fluid dynamics within these compartments may exacerbate interstitial fluid accumulation, neuroinflammation, peritumoral edema, and immune evasion, suggesting that glymphatic dysfunction contributes to tumor spread [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36].

A distinctive feature of this model is the consistent presence of nestin⁺ CSLCs within perivascular and leptomeningeal niches, often arranged in chain-like patterns suggestive of collective migration. Their close association with vascular structures underscores the relevance of endothelial–stem cell interactions in maintaining stemness and directing invasion [

37,

38]

The interplay between immune and stem-like components appears central to this process. TAMs were abundant across primary and disseminated ENU-MPNST sites, displaying marked morphological heterogeneity, from amoeboid forms in tumor cores to transitional phenotypes at invasion fronts. TAM density correlated positively with the Ki-67 proliferation index, suggesting an active role in promoting tumor expansion. Dissemination along perivascular routes was also associated with overexpression of butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE). Although BuChE has been implicated in tumorigenesis in several malignancies [

21,

22,

39,

40], its role in MPNSTs remains largely unexplored. The present findings indicate that BuChE may enhance CSLC motility and modulate perivascular niche dynamics through TAM–astrocyte activation. In other malignancies, such as gliomas and non-small cell lung carcinoma, dysregulation in cholinergic metabolism polarizes TAMs toward immunosuppressive and proangiogenic phenotypes [

41,

42]. Consistently, Wang et al. (2025) demonstrated that BuChE regulates neuroinflammation and tumor immunosuppression via astrocyte and microglial activation [

41].

At invasion fronts, nestin⁺ CSLC clusters were frequently surrounded by reactive astrocytes and TAMs, resembling the pre-metastatic niches described in gliomas and brain metastases [

43]. These reactive glial and immune cells contribute to glia limitans disruption and extracellular matrix remodeling through cytokines (CCL2, IL-6, CSF1), metalloproteases (MMP2, MMP7, MMP9), and growth factors (VEGF, PDGF, EGF) [

44]. Following disruption of the glia limitans, nestin

+ CSLCs infiltrate the parenchyma and acquire invasive capacity, while PD-L1 expression facilitates local immune evasion [

45,

46]. Transcriptomic analyses of human MPNSTs support these findings, showing activation of STAT3, Sonic Hedgehog (SHH), and Wnt/β-catenin pathways [

47].

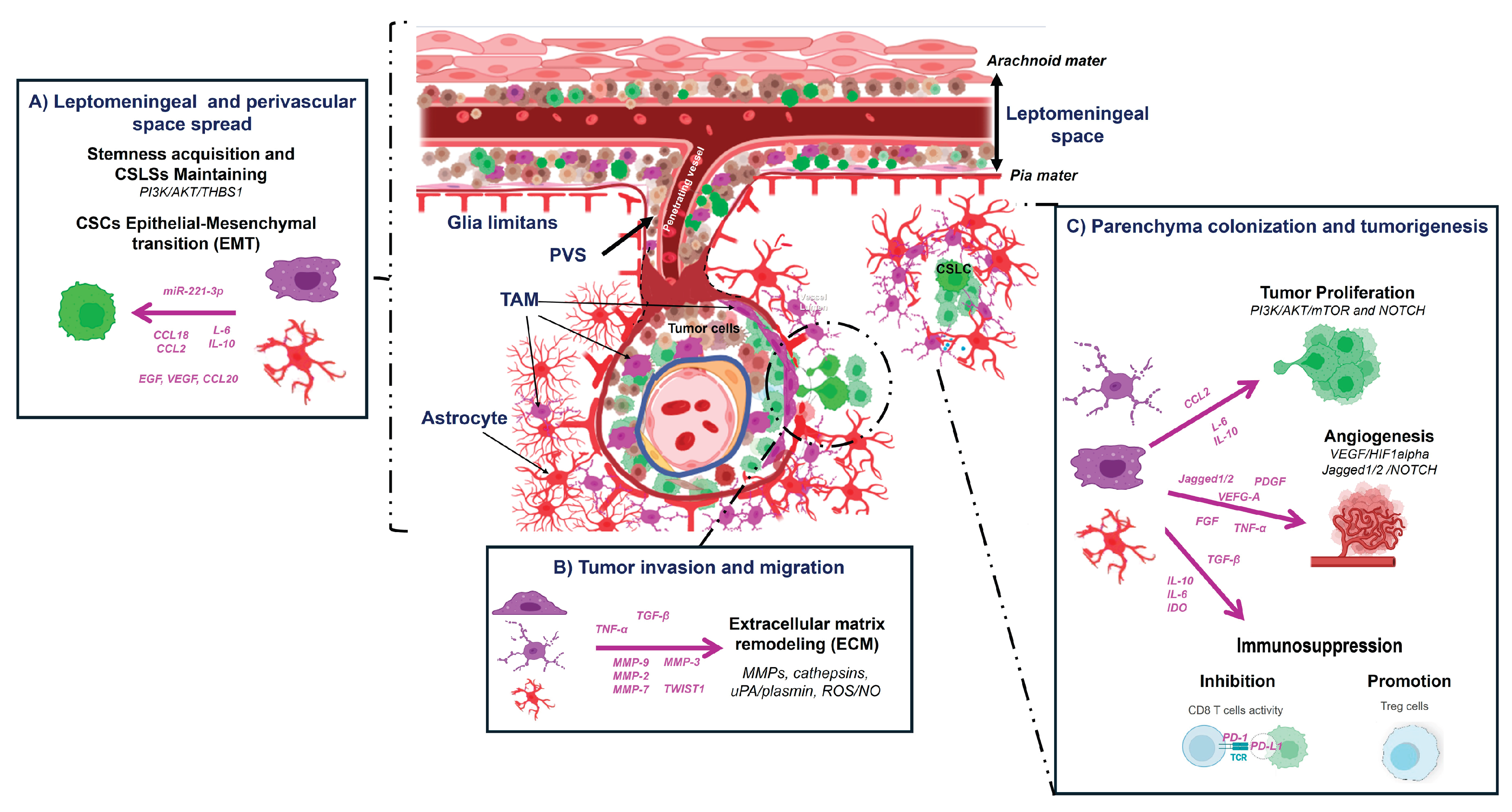

Together, these results support a model in which perivascular and leptomeningeal compartments act as permissive microenvironments for MPNST dissemination, where nestin⁺/BuChE⁺ CSLCs, TAMs, and reactive astrocytes interact to create a pro-invasive, immunomodulatory niche. The morphological heterogeneity of TAMs likely reflects functional specialization, with TAM-derived exosomes, cytokines, and metabolic cues likely orchestrating CSLC seeding and expansion [

48]. As summarized in

Figure 7, we propose a mechanistic framework for the CSLCs-TAM-astrocyte axis driving intracranial dissemination in ENU-induced MPNSTs

Limitations

Limitations of this study include: (i) absence of functional assays directly testing CSLC behavior; (ii) TAM characterization limited to Iba1 without polarization markers (e.g., CD206, iNOS) [

49]; (iii) indirect inference of glymphatic involvement; and (iv) the unvalidated role of BuChE in human MPNSTs. Despite these constraints, the ENU model faithfully recapitulates key features of intracranial MPNST invasion and provides a robust platform for investigating tumor–microenvironment interactions.

5. Conclusions

Leptomeningeal and perivascular spaces represent critical anatomical routes for intracranial MPNST dissemination. The coordinated interplay among nestin⁺/BuChE⁺ CSLCs, TAMs, and reactive astrocytes establishes a permissive niche that promotes invasion and immune evasion. These findings provide a mechanistic framework for developing targeted therapeutic strategies aimed at disrupting the CSLC–TAM–astrocyte axis to limit tumor progression and improve outcomes in this aggressive disease.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: Graphical representation of Ki-67 and Iba-1 labeling indices (LI) according to the anatomical region of MPNST dissemination; Table S1: Dataset of 25 ENU-induced MPNST samples selected for quantitative analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B. and J.V.L.; Methodology, S.B. and N.O.; Software, S.B. and L.Z.; Validation, S.B., L.Z., and J.V.L.; Formal analysis, A.C. and J.V.L.; Investigation, S.B.; Resources, S.B.; Data curation, S.B.; Writing—original draft, S.B.; Writing—review and editing, A.C. and J.V.L.; Supervision, A.C. and A.M.; Project administration, A.M.; Funding acquisition, A.M. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (PID2021-126434OB-I00) and Basque Government (IT1706-22, 2022333034, 2023333012 and 2024333005) and Recovery and Resilience Facility—NextGenerationEU (INVESTIGO program).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee for Animal Research of the University of the Basque Country (Ref. CEEA/82b/2010/LAFUENTESANCHEZ).

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Encarnación Fernández-Valle and David Castejón Ferrer from ICTS Bioimagen Complutense (BIOIMAC) for their support with MRI analysis, and Aitor Jauregi for technical assistance with immunohistochemical studies. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| BuChE |

Butyrylcholinesterase |

| CNS |

Central nervous system |

| CFS |

Cerebrospinal fluid |

| CSLC |

Cancer stem-like cell |

| ECM |

Extracellular matrix |

| EGFR |

Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| EMA |

Epithelial membrane antigen |

| ENU |

N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea |

| GFAP |

Glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| Iba-1 |

Ionized calcium-binding adaptor protein- |

| Ki-67 |

Nuclear proliferation marker |

| LEA |

Lycopersicon esculentum lectin |

| LI |

Labelling index |

| MMPs |

Matrix metalloproteinases |

| MPNST |

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| NF |

Neurofilament protein |

| NF1 |

Neurofibromatosis type 1 |

| NSE |

Neuron-specific enolase |

| PVS |

Perivascular (Virchow-Robin) space |

| SYP |

Synaptophysin |

| S100 |

Small acidic EF-hand calcium-binding proteins 100 |

| TAM |

Tumor-associated macrophage |

| TME |

Tumor microenvironment |

| TP53 |

Tumor suppressor p53 |

References

- Bates, J.E.; Peterson, C.R.; Dhakal, S.; Giampoli, E.J.; Constine, L.S. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST): a SEER analysis of incidence across the age spectrum and therapeutic interventions in the pediatric population. Pediatr. Blood. Cancer. 2014, 61, 1955–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFemina, J.; Qin, L.X.; Moraco, N.H.; Antonescu, C.R.; Morland, B.; Jia, X.; Li, R.; Torres, K.E.; Hunt, K.K.; et al. Oncologic outcomes of sporadic, neurofibromatosis-associated, and radiation-induced malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 20, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magallón-Lorenz, M.; Terribas, E.; Ortega-Bertran, S.; Creus-Bachiller, E.; Fernández, M.; Requena, G.; Rosas, I.; Mazuelas, H.; Uriarte-Arrazola, I.; Negro, A.; Lausová, T.; et al. Deep genomic analysis of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor cell lines challenges current malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor diagnosis. iScience. 2023, 26, 106096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Stewart, D.R.; Reilly, K.M.; Viskochil, D.; Miettinen, M.M.; Widemann, B.C. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors state of the science: leveraging clinical and biological insights into effective therapies. Sarcoma. 2017, 2017, 7429697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardlaw, J.M.; Benveniste, H.; Nedergaard, M.; Zlokovic, B.V.; Mestre, H.; Lee, H.; Douba, L.; Brown, R.; Ramirez, J.; MacIntosh, B.J. Perivascular spaces in the brain: anatomy, physiology and pathology. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2020, 16, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ineichen, B.V.; Okar, S.V.; Proulx, S.T.; Engelhardt, B.; Lassmann, H.; Reich, D.S. Perivascular spaces and their role in neuroinflammation. Neuron. 2022, 110, 3566–3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dancsok, A.R.; Gao, D.; Lee, A.F.; Steigen, S.E.; Blay, J.Y.; Thomas, D.M.; Maki, R.G.; Nielsen, T.O.; Demicco, E.G. Tumor-associated macrophages and macrophage-related immune checkpoint expression in sarcomas. Oncoimmunology. 2020, 9, 1747340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, R.; Ren, W.; Ya, G.; Wang, B.; He, J.; Ren, S.; Jiang, L.; Zhao, S. Role of chemokines in the crosstalk between tumor and tumor-associated macrophages. Clin. Exp. Med. 2023, 23, 1359–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.Q.; Du, W.L.; Cai, M.H.; Yao, J.Y.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Mou, X.Z. The roles of tumor-associated macrophages in tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. Cell Immunol. 2020, 353, 104119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Xie, X.P.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Sait, S.F.; Iyer, S.V.; Chen, Y.J.; Brown, R.; Laks, D.R.; Chipman, M.E.; Shern, J.F.; Parada, L.F. Stem-like cells drive NF1-associated MPNST functional heterogeneity and tumor progression. Cell Stem Cell. 2021, 28, 1397–1410.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyra, M.; Kluwe, L.; Hagel, C.; Nguyen, R.; Panse, J.; Kurtz, A.; Mautner, V.F.; Rabkin, S.D.; Demestre, M. Cancer stem cell-like cells derived from malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. PLoS One. 2011, 6, e21099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.M.N.; Zhang, F.; Rao, R.; Adam, M.; Pollard, K.; Szabo, S.; Liu, X.; Belcher, K.A.; Luo, Z.; Ogurek, S.; Reilly, C.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, L.; Rubin, J.; Chang, L.S.; Xin, M.; Yu, J.; Suva, M.; Pratilas, C.A.; Potter, S.; Lu, Q.R. Single-cell multiomics identifies clinically relevant mesenchymal stem-like cells and key regulators for MPNST malignancy. Sci Adv. 2022, 8, eabo5442, Epub 2022 Nov 2. PMID: 36322658; PMCID: PMC9629745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shimada S, Tsuzuki T, Kuroda M, Nagasaka T, Hara K, Takahashi E, Hayakawa S, Ono K, Maeda N, Mori N, Illei PB. Nestin expression as a new marker in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Pathol Int. 2007, 57, 60–67, PMID: 17300669. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Luo, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, P.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; et al. Expression of nestin is associated with prognosis in glioma patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Neurobiol. 2015, 52, 1034–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulnes S, Bermúdez G, Lafuente JV. Association of Notch-1, osteopontin and stem-like cells in ENU-glioma malignant process. Oncotarget. 2018, 9, 31330–31341. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukushima, S.; Endo, M.; Matsumoto, Y.; Fukushi, J.I.; Matsunobu, T.; Kawaguchi, K.I.; Setsu, N.; IIda, K.; Yokoyama, N.; Nakagawa, M.; Yahiro, K.; Oda, Y.; Iwamoto, Y.; Nakashima, Y. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha is a poor prognostic factor and potential therapeutic target in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. PLoS One. 2018, 13, e0194508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng ZQ, Chen JT, Zheng MC, Yang LJ, Wang JM, Liu QL, Chen LF, Ye ZC, Lin JM, Lin ZX. Nestin+/CD31+ cells in the hypoxic perivascular niche regulate glioblastoma chemoresistance by upregulating JAG1 and DLL4. Neuro Oncol. 2021, 23, 905–919, PMID: 33249476; PMCID: PMC8168822. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- García-Blanco A, Bulnes S, Pomposo I, Carrasco A, Lafuente JV. Nestin+ cells forming spheroid aggregates resembling tumorspheres in experimental ENU-induced gliomas. Histol. Histopathol. 2016, 31, 1347–1356. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, C., Poppleton, H., Kocak M, Hogg TL, Fuller C, Hamner B, Oh EY, Gaber MW, Finklestein D, Allen M, Frank A, Bayazitov IT, Zakharenko SS, Gajjar A, Davidoff A, Gilbertson RJ. A perivascular niche for brain tumor stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2007, 11, 69–82, PMID: 17222791. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mack A, Robitzki A. The key role of butyrylcholinesterase during neurogenesis and neural disorders: an antisense-5’butyrylcholinesterase-DNA study. Prog Neurobiol. 2000, 60, 607–628. [CrossRef]

- Vidal, CJ. Expression of cholinesterases in brain and non-brain tumours. Chem Biol Interact. 2005, 157-158, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar A, Sharma S, Ghosh A, et al. Butyrylcholinesterase as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target in breast and brain cancers. J Neurochem. 2017, 143, 18–28. [CrossRef]

- Bulnes S, Bengoetxea H, Ortuzar N, et al. Endogenous experimental glioma model, links between glial stem cells and angiogenesis. In Glioma. Exploring its biology and practical relevance; Ghosh, A, Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, 2011; pp. 405–428, Chapter 18; ISBN 978-953-307-379. [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff, J.M.; Kourea, H.P.; Louis, D.N.; and Scheithauer, B.W. (2000) Tumours of cranial and peripheral nerves. In Pathology and genetics of tumours: of the nervous system. Kleihues,P., and Cavenee,W.K. (eds). IARC, International Agency for research on cancer, pp. 163–174.

- Koelsch, B.; van den Berg, L.; Grabellus, F.; Fischer, C., Kutritz, A., Kindler-Röhrborn, A. Chemically induced rat Schwann cell neoplasia as a model for early-stage human peripheral nerve sheath tumors: phenotypic characteristics and dysregulated gene expression. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013, 72, 404–415. [CrossRef]

- Kindler-Röhrborn, A.; Kölsch, B.U.; Fischer, C.; Held, S.; Rajewsky, M.F. Ethylnitrosourea-induced development of malignant schwannomas in the rat: two distinct loci on chromosome 10 involved in tumor susceptibility and oncogenesis. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, W.M.S.; Burch, R.L. The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique; Methuen & Co.: London, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Bulnes, S.; Murueta-Goyena, A.; Lafuente, J.V. Differential exposure to N-ethyl N-nitrosourea during pregnancy is relevant to the induction of glioma and PNSTs in the brain. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2021, 86, 106998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulnes S, Bilbao J, Lafuente JV. Microvascular adaptive changes in experimental endogenous brain gliomas. Histol. Histopathol. 2009, 24, 693–706. [CrossRef]

- Cocito, C.; Martin, B.; Giantini-Larsen, A.M.; Valcarce-Aspegren, M.; Souweidane, M.M.; Szalontay, L.; Dahmane, N.; Greenfield, J.P. Leptomeningeal dissemination in pediatric brain tumors. Neoplasia. 2023, 39, 100898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy-O’Reilly, M.A.; Lanman, T.; Ruiz, A.; Rogawski, D.; Stocksdale, B.; Nagpal, S. Diagnostic and therapeutic updates in leptomeningeal disease. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2023, 25, 937–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remsik, J. and Boire, A. The path to leptomeningeal metastasis. Rev. Cancer. 2024, 24, 448–460. [CrossRef]

- Iliff, J.J.; Wang, M.; Liao, Y.; Plogg, B.A.; Peng, W.; Gundersen, G.A.; Benveniste, H.; Vates, G.E.; Deane, R.; Goldman, S.A.; Nagelhus, E.A.; Nedergaard, M. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid β. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 147ra111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freret, M. E and Boire, A. The anatomic basis of leptomeningeal metastasis. J. Exp. Med. 2024, 221, e20212121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang W, Sun W, Li C, Zhou J, Long C, Li H, Xu D, Xu H. Glymphatic system dysfunction and cerebrospinal fluid retention in gliomas: evidence from perivascular space diffusion and volumetric analysis. Cancer Imaging. 2025, 25, 51. [CrossRef]

- Toh, C.H.; Siow, T.Y.; Castillo, M. Peritumoral brain edema in metastases may be related to glymphatic dysfunction. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 725354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, D.; Meissner, N.; Kleff, V.; Jastrow, H.; Yamaguchi, M.; Ergün, S.; Jendrossek, V. Nestin(+) tissue-resident multipotent stem cells contribute to tumor progression by differentiating into pericytes and smooth muscle cells resulting in blood vessel remodeling. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Guo, Z.; Li, G.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, B.; Wang, J.; Li, X. Cancer stem cells and their niche in cancer progression and therapy. Cancer Cell. In. 2023, 23, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuol, N.; Godlewski, J.; Kmiec, Z.; Vogrin, S.; Fraser, S.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Nurgali, K. Cholinergic signaling influences the expression of immune checkpoint inhibitors, PD-L1 and PD-L2, and tumor hallmarks in human colorectal cancer tissues and cell lines. BMC Cancer. 2023, 23, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfitzinger, P.L.; Fangmann, L.; Wang, K.; Demir, E.; Gürlevik, E.; Fleischmann-Mundt, B.; Brooks, J.; D’Haese, J.G.; Teller, S.; Hecker, A.; Jesinghaus, M.; Jäger, C.; Ren, L.; Istvanffy, R.; Kühnel, F.; Friess, H.; Ceyhan, G.O.; Demir, I.E. Indirect cholinergic activation slows down pancreatic cancer growth and tumor-associated inflammation. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 39, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Lu, Z.; Duan, Y.; He, S.; Lyu, W.; Liao, Q.; Li, Q.; Chen, X.; Li, H. Experimental Evaluation of QY-69: A Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitor with Anti-Glioblastoma Efficacy. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B., Li, G.; Gulizeba, H.; Liu, H.; Sima, X.; Zhou, T.; Huang, Y. Choline metabolism reprogramming mediates an immunosuppressive microenvironment in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) by promoting tumor-associated macrophage functional polarization and endothelial cell proliferation. J Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 442. [CrossRef]

- Zhou T, Yan Y, Lin M, Zeng C, Mao X, Zhu Y, Han J, Li DD, Zhang J. Astrocyte involvement in brain metastasis: from biological mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2025, 60. [CrossRef]

- Verona, F.; Di Bella, S.; Schirano, R.; Manfredi, C.; Angeloro, F.; Bozzari, G.; Todaro, M.; Giannini, G.; Stassi, G.; Veschi, V. Cancer stem cells and tumor-associated macrophages as mates in tumor progression: mechanisms of crosstalk and advanced bioinformatic tools to dissect their phenotypes and interaction. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1529847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Chen, Q.; Chen, M.; Guo, S.; Hou, P.; Zou, Y.; Wang, J.; He, B.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, L.; Luo, L. Interaction of glioma-associated microglia/macrophages and anti-PD1 immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2023, 72, 1685–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basak, U.; Sarkar, T.; Mukherjee, S., Chakraborty, S.; Dutta, A.; Dutta, S.; Nayak, D.; Kaushik, S.; Das, T.; Sa, G. Tumor-associated macrophages: an effective player of the tumor microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1295257. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Wang, S.; Shen, Q.; Zhou, X. The role of STAT3 in leading the crosstalk between human cancers and the immune system. Cancer Lett. 2018, 415, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Xu, L.; Chen, Q.; Zou, C.; Huang, J.; Zhang, L. Crosstalk between exosomes and tumor-associated macrophages in hepatocellular carcinoma: implication for cancer progression and therapy. Front Immunol. 2025, 16, 1512480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisi, L.; Ciotti, G.M.; Braun, D.; Kalinin, S.; Currò, D.; Dello Russo, C.; Coli, A.; Mangiola, A.; Anile, C.; Feinstein, D.L.; Navarra, P. Expression of iNOS, CD163 and ARG-1 taken as M1 and M2 markers of microglial polarization in human glioblastoma and the surrounding normal parenchyma. Neurosci. Lett. 2017, 645, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Anatomical and Histological Characterization of ENU-Induced MPNSTs. T1-weighted MRI showing sagittal (A) and coronal (B) sections of a rat head with an ENU-induced MPNST extending from the Gasserian ganglion sheath toward the cortical convexity, producing cortical compression and midline shift. H&E staining reveals tumor spreading at the brain base (C) and within the interhemispheric subarachnoid space (D). S-100 immunolabeling shows focal positivity near the parenchyma (black arrow) (E) and diffuse strong expression at the cortical convexity (F). Nestin immunoreactivity intense in both regions of dissemination sites (G,H). Scale bar: 100 μm.

Figure 1.

Anatomical and Histological Characterization of ENU-Induced MPNSTs. T1-weighted MRI showing sagittal (A) and coronal (B) sections of a rat head with an ENU-induced MPNST extending from the Gasserian ganglion sheath toward the cortical convexity, producing cortical compression and midline shift. H&E staining reveals tumor spreading at the brain base (C) and within the interhemispheric subarachnoid space (D). S-100 immunolabeling shows focal positivity near the parenchyma (black arrow) (E) and diffuse strong expression at the cortical convexity (F). Nestin immunoreactivity intense in both regions of dissemination sites (G,H). Scale bar: 100 μm.

Figure 2.

Immunophenotypic profile of ENU-induced MPNST. Basal tumors arising from the Gasserian ganglion sheath exhibit hemorrhage, high cellularity (A), marked nuclear atypia, and entrapped Schwann cells (B). Immunohistochemistry shows focal S-100 expression (C), strong synaptophysin immunoreactivity (D), moderate Ki-67 labelling (E), and scattered p53-positive nuclei (F). Convexity tumors display spindle-shaped, hyperchromatic cells (G), compact fascicular architecture (H), and hyalinized vessels (I), with diffuse S-100 (J), moderate Ki-67 (K), and low p53 expression (L). Scale bar: 50 µm.

Figure 2.

Immunophenotypic profile of ENU-induced MPNST. Basal tumors arising from the Gasserian ganglion sheath exhibit hemorrhage, high cellularity (A), marked nuclear atypia, and entrapped Schwann cells (B). Immunohistochemistry shows focal S-100 expression (C), strong synaptophysin immunoreactivity (D), moderate Ki-67 labelling (E), and scattered p53-positive nuclei (F). Convexity tumors display spindle-shaped, hyperchromatic cells (G), compact fascicular architecture (H), and hyalinized vessels (I), with diffuse S-100 (J), moderate Ki-67 (K), and low p53 expression (L). Scale bar: 50 µm.

Figure 3.

Leptomeningeal dissemination showed by Butyrylcholinesterase staining. A coronal rat brain section showing intense BuChE staining delineating ENU-MPNST spread through interconnected subarachnoid and perivascular spaces (A). Tumor dissemination extends from the basal leptomeninges (1), laterally along the meningeal sheath (2), and reaches the interhemispheric fissure (3). (B) Tumor dissemination toward the parenchyma occurs via perivascular spaces surrounding penetrating vessels. (C) Fibrillar BuChE⁺ cell clusters are seen in leptomeningeal compartments. Scale bar: 50 µm.

Figure 3.

Leptomeningeal dissemination showed by Butyrylcholinesterase staining. A coronal rat brain section showing intense BuChE staining delineating ENU-MPNST spread through interconnected subarachnoid and perivascular spaces (A). Tumor dissemination extends from the basal leptomeninges (1), laterally along the meningeal sheath (2), and reaches the interhemispheric fissure (3). (B) Tumor dissemination toward the parenchyma occurs via perivascular spaces surrounding penetrating vessels. (C) Fibrillar BuChE⁺ cell clusters are seen in leptomeningeal compartments. Scale bar: 50 µm.

Figure 4.

Morphological heterogeneity of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). H&E staining of an MPNST with leptomeningeal dissemination (A) shows abundant Iba-1⁺ TAMs. (B) Distinct TAM morphologies are observed depending on location (highlighted in rectangles): intermediate forms within the arachnoid (C) and pia mater (D), amoeboid forms in the tumor core (E), and ramified microglia reflecting a resting state in adjacent non-tumoral parenchyma (F). Scale bar: 50 μm.

Figure 4.

Morphological heterogeneity of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). H&E staining of an MPNST with leptomeningeal dissemination (A) shows abundant Iba-1⁺ TAMs. (B) Distinct TAM morphologies are observed depending on location (highlighted in rectangles): intermediate forms within the arachnoid (C) and pia mater (D), amoeboid forms in the tumor core (E), and ramified microglia reflecting a resting state in adjacent non-tumoral parenchyma (F). Scale bar: 50 μm.

Figure 5.

Perivascular dissemination of ENU-induced MPNSTs. (A,B) Confocal immunofluorescence showing penetrating microvessels (white arrows) labeled with LEA-FITC (green and active glial reaction (GFAP, red) with Iba-1⁺ TAMs (purple) at the tumor–brain interface; nuclei counterstained with Hoechst (blue). (C) Perivascular space (PVS) histology demonstrates strong BuChE immunoreactivity at the invasion front. nestin⁺ CSLCs display diverse morphologies: small round clusters (black arrow), elongated perivascular cells (white arrow), and astrocyte-like cells at the tumor margin (red arrow). The spatial arrangement emphasizes the interplay between CSLCs, TAMs, and astrocytes within invasion-permissive niches. Scale bars: A–B, 100 µm; C, 50 µm. Abbreviations: CP, cerebral parenchyma; T, tumor; L, vessel lumen; gl, glia limitans.

Figure 5.

Perivascular dissemination of ENU-induced MPNSTs. (A,B) Confocal immunofluorescence showing penetrating microvessels (white arrows) labeled with LEA-FITC (green and active glial reaction (GFAP, red) with Iba-1⁺ TAMs (purple) at the tumor–brain interface; nuclei counterstained with Hoechst (blue). (C) Perivascular space (PVS) histology demonstrates strong BuChE immunoreactivity at the invasion front. nestin⁺ CSLCs display diverse morphologies: small round clusters (black arrow), elongated perivascular cells (white arrow), and astrocyte-like cells at the tumor margin (red arrow). The spatial arrangement emphasizes the interplay between CSLCs, TAMs, and astrocytes within invasion-permissive niches. Scale bars: A–B, 100 µm; C, 50 µm. Abbreviations: CP, cerebral parenchyma; T, tumor; L, vessel lumen; gl, glia limitans.

Figure 6.

CSLC–Glial–Immune Interactions at the Invasive Front of MPNSTs. Confocal immunofluorescence images illustrate the coordinated interplay between nestin⁺ CSLCs (green), GFAP⁺ reactive astrocytes (red), and Iba-1⁺ tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs, purple) during tumor progression. (A,B) At the primary tumor margin, abundant penetrating microvessels (LEA, white) are surrounded by a dense network of reactive astrocytes and ramified TAMs, with Nestin⁺ CSLCs aligned along vascular walls and within perivascular niches. (C) In deeper cortical regions, CSLCs accumulate at the perivascular invasive front, interacting with GFAP⁺ astrocytic processes and TAMs to breach the glial barrier. (D) Individual Nestin⁺ tumor cells infiltrate the adjacent parenchyma, enclosed by a dual protective glial–immune barrier: an inner layer of GFAP⁺ astrocytes and an outer ring of Iba-1⁺ TAMs. Scale bar: 20 µm.

Figure 6.

CSLC–Glial–Immune Interactions at the Invasive Front of MPNSTs. Confocal immunofluorescence images illustrate the coordinated interplay between nestin⁺ CSLCs (green), GFAP⁺ reactive astrocytes (red), and Iba-1⁺ tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs, purple) during tumor progression. (A,B) At the primary tumor margin, abundant penetrating microvessels (LEA, white) are surrounded by a dense network of reactive astrocytes and ramified TAMs, with Nestin⁺ CSLCs aligned along vascular walls and within perivascular niches. (C) In deeper cortical regions, CSLCs accumulate at the perivascular invasive front, interacting with GFAP⁺ astrocytic processes and TAMs to breach the glial barrier. (D) Individual Nestin⁺ tumor cells infiltrate the adjacent parenchyma, enclosed by a dual protective glial–immune barrier: an inner layer of GFAP⁺ astrocytes and an outer ring of Iba-1⁺ TAMs. Scale bar: 20 µm.

Figure 7.

Proposed mechanisms of intracranial dissemination in ENU-induced MPNSTs. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and astrocytes support cancer stem-like cells (CSLCs) and drive ENU-MPNST dissemination via three interconnected mechanisms: (

A) Leptomeningeal and perivascular spread. Enhancement of CSLC stemness and mesenchymal plasticity through cytokine secretion (CCL2, IL-6, IL-10), activation of PI3K/AKT and NOTCH pathways, release of growth factors (EGF, FGF), and exosomal delivery of miR-221-3p. (

B) Tumor invasion and migration. Remodeling of the extracellular matrix (ECM) via MMPs, cathepsins, uPA/plasmin, ROS/NO, and exosomal proteases, promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) through EGF, VEGF, and CCL20 signaling. (

C) Parenchyma colonization and tumorigenesis. Tumor proliferation is enhanced through PI3K/AKT/mTOR and NOTCH pathways activation, while angiogenesis is induced via VEGF/HIF1α and Jagged1/2–NOTCH signaling. The release of VEGF, PDGF, TGF-β, FGF, TNF-α, and MMPs sustains vascular remodeling and metastatic growth. In parallel, secretion of immunosuppressive mediators (IDO, IL-10, IL-6, TGF-β) inhibits CD8⁺ T-cell activity and promotes Treg expansion, generating an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment.

Abbreviations: TAMs, tumor-associated macrophages; CSLCs, cancer stem-like cells; ENU-MPNST, N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea-induced malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor; PVS, perivascular space; CCL2, C-C motif chemokine ligand 2; IL, interleukin; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase; AKT, protein kinase B; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin; EGF, epidermal growth factor; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; miR-221-3p, microRNA-221-3p; ECM, extracellular matrix; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; uPA, urokinase-type plasminogen activator; ROS, reactive oxygen species; NO, nitric oxide; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; HIF1α, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α; EMT, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; CCL20, C-C motif chemokine ligand 20; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; IDO, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; Tregs, regulatory T cells. Adapted from Verona et al. [

44] and Basak et al. [

46]. Created with BioRender.com.

Figure 7.

Proposed mechanisms of intracranial dissemination in ENU-induced MPNSTs. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and astrocytes support cancer stem-like cells (CSLCs) and drive ENU-MPNST dissemination via three interconnected mechanisms: (

A) Leptomeningeal and perivascular spread. Enhancement of CSLC stemness and mesenchymal plasticity through cytokine secretion (CCL2, IL-6, IL-10), activation of PI3K/AKT and NOTCH pathways, release of growth factors (EGF, FGF), and exosomal delivery of miR-221-3p. (

B) Tumor invasion and migration. Remodeling of the extracellular matrix (ECM) via MMPs, cathepsins, uPA/plasmin, ROS/NO, and exosomal proteases, promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) through EGF, VEGF, and CCL20 signaling. (

C) Parenchyma colonization and tumorigenesis. Tumor proliferation is enhanced through PI3K/AKT/mTOR and NOTCH pathways activation, while angiogenesis is induced via VEGF/HIF1α and Jagged1/2–NOTCH signaling. The release of VEGF, PDGF, TGF-β, FGF, TNF-α, and MMPs sustains vascular remodeling and metastatic growth. In parallel, secretion of immunosuppressive mediators (IDO, IL-10, IL-6, TGF-β) inhibits CD8⁺ T-cell activity and promotes Treg expansion, generating an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment.

Abbreviations: TAMs, tumor-associated macrophages; CSLCs, cancer stem-like cells; ENU-MPNST, N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea-induced malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor; PVS, perivascular space; CCL2, C-C motif chemokine ligand 2; IL, interleukin; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase; AKT, protein kinase B; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin; EGF, epidermal growth factor; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; miR-221-3p, microRNA-221-3p; ECM, extracellular matrix; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; uPA, urokinase-type plasminogen activator; ROS, reactive oxygen species; NO, nitric oxide; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; HIF1α, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α; EMT, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; CCL20, C-C motif chemokine ligand 20; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; IDO, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; Tregs, regulatory T cells. Adapted from Verona et al. [

44] and Basak et al. [

46]. Created with BioRender.com.

Table 1.

Primary and secondary antibodies used for immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunofluorescence assay (IF).

Table 1.

Primary and secondary antibodies used for immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunofluorescence assay (IF).

| Antibodies |

Target protein |

Dilution / Clone |

Catalogue No. |

Supplier |

| Primary antibodies |

|

|

|

|

| Nestin |

Neuroepithelial stem cell protein |

1:75, mAb (mouse) |

sc-33677 |

Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

| GFAP |

Glial fibrillary acidic protein |

1:200, pAb (rabbit) |

Z0334 |

Dako |

| GFAP |

Glial fibrillary acidic protein |

1:200, pAb (goat) |

Ab7260 |

Abcam |

| Ki-67 (MIB-5) |

Nuclear proliferation marker |

1:75, mAb (mouse) |

M7248 |

Agilent Technologies |

| Iba-1 |

Ionized calcium-binding adaptor protein-1 |

1:500, pAb (rabbit) |

019-19741 |

Fujifilm Wako |

| EMA |

Epithelial membrane antigen |

1:100, pAb (rabbit) |

ab19898 |

Abcam |

| SYP |

Synaptophysin |

1:75, mAb (mouse) |

IR776 |

Dako |

| S100 |

Schwann cell marker |

1:100, mAb (mouse) |

MA1-26621 |

Thermo Fisher Scientific |

| NF |

Neurofilament protein |

1:100, mAb (mouse) |

AB1991 |

Chemicon International |

| EGFR |

Epidermal growth factor receptor |

1:150, mAb (mouse) |

M7239 |

Dako |

| TP53 |

Tumor suppressor p53 |

1:75, mAb (mouse) |

pAb240 |

Dako |

| Secondary antibodies |

|

|

|

|

| Alexa Fluor 647 |

Donkey anti-rabbit IgG |

1:200 |

A31573 |

Invitrogen |

| Alexa Fluor 488 |

Donkey anti-mouse IgG |

1:200 |

A21202 |

Invitrogen |

| Alexa Fluor 568 |

Donkey anti-goat IgG |

1:200 |

A11057 |

Invitrogen |

Table 2.

Chronology of MPNST detection in Sprague Dawley rats after ENU prenatal exposure.

Table 2.

Chronology of MPNST detection in Sprague Dawley rats after ENU prenatal exposure.

| Age (months) |

Total Rats (M/F) |

MPNST Cases (N) |

MPNST % |

MPNST Cases (M/F) |

MPNST % (M/F) |

| 6 |

29 (14/15) |

12 |

41.37 |

7/5 |

50/33.3 |

| 7 |

15(6/9) |

7 |

46.66 |

3/4 |

50/44.4 |

| 8 |

12(8/4) |

4 |

33.3 |

3/1 |

37.5/25 |

| 9 |

18(8/10) |

2 |

11.11 |

1/1 |

12.5/10 |

| Total |

74(36/38) |

25 |

33.7 |

14/11 |

38/28.9 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).