Submitted:

03 July 2024

Posted:

04 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

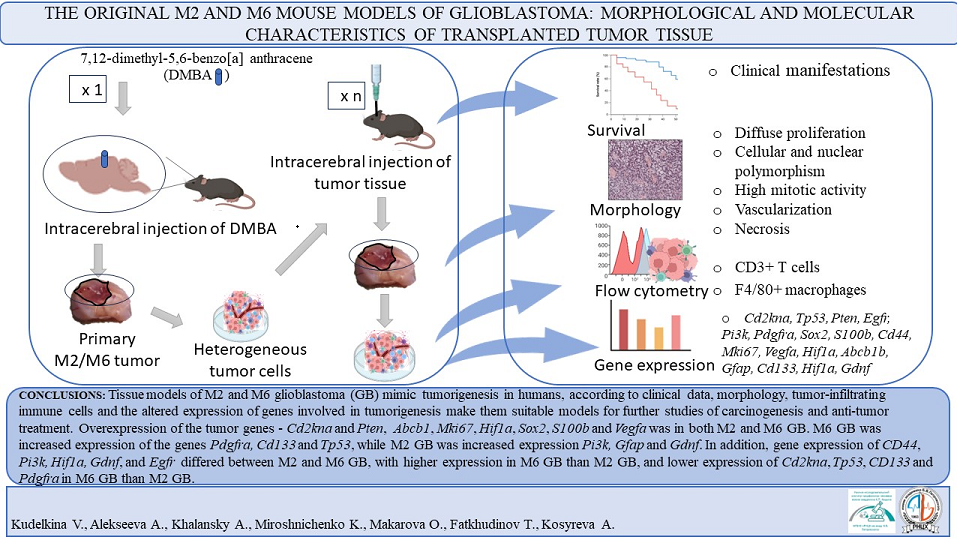

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| Cd44 | AGAAGGGACAACTGCTTCGG | TTGGAGCTGCAGTAGGCTG |

| Cdkn2a | TGGTCACTGTGAGGATTCAGC | TGCCCATCATCATCACCTGG |

| Pi3k | CCGCTCAGGGAGAGGAGTA | CCACTCTCAGCTTCACCTCC |

| S100b | GATGTCCGAGCTGGAGAAGG | CCTGCTCCTTGATTTCCTCCA |

| Tp53 | TTCTCCGAAGACTGGATGACTG | CTGCTCCTTGATTTCCTCCA |

| Mki67 | CCTGCCTGTTTGGAAGGAGT | AAGGAGCGGTCAATGATGGTT |

| Pten | GGACCAGAGACAAAAAGGGAGT | CCTTTAGCTGGCAGACCACA |

| Vegfa | TCCACCATGCCAAGTGGTC | AGATGTCCACCAGGGTCTCA |

| Hif1a | GATGTCCGAGCTGGAGAAGG | CTGTCTAGACCACCGGCATC |

| Cd133 | GGAGCAGTACACCAACACCA | GTCTGTTTGATGGCTGTCGC |

| Sox2 | AGGAAAGGGTTCTTGCTGGG | GGTCTTGCCAGTACTTGCTCT |

| Pdgfra | GTGCTAGCGCGGAACCT | CATAGCTCCTGAGACCCGC |

| Gdnf | GACCGGATCCGAGGTGC | GAGGGAGTGGTCTTCAGCG |

| Mgmt | GACCGGATCCGAGGTGC | GAGGGAGTGGTCTTCAGCG |

| Abcb1 | CTCTTGAAGCCGTAAGAGGCT | AACTCCATCACCACCTCACG |

| Gfap | GGCTGCGTATAGACAGGAGG | CCAGGCTGGTTTCTCGGAT |

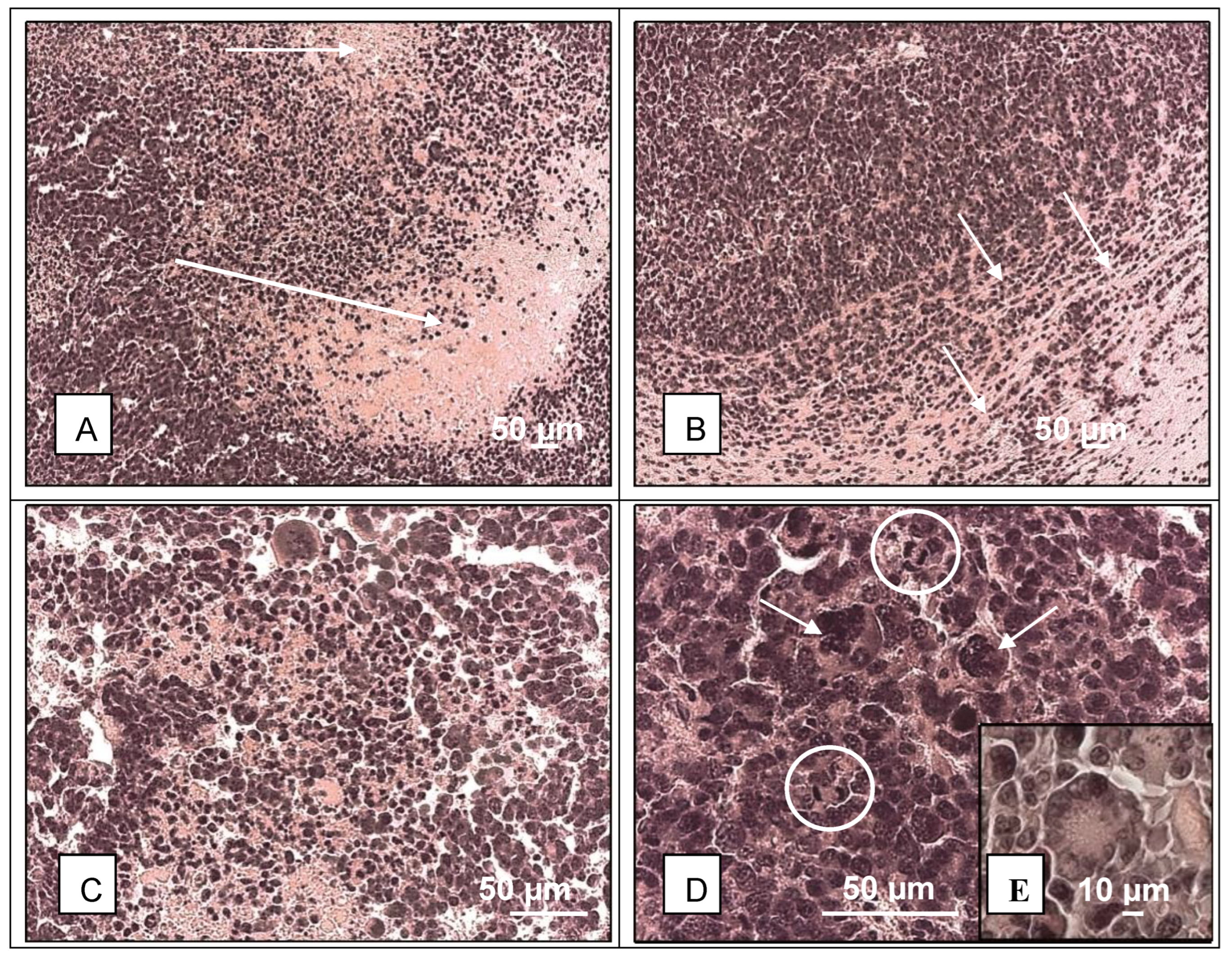

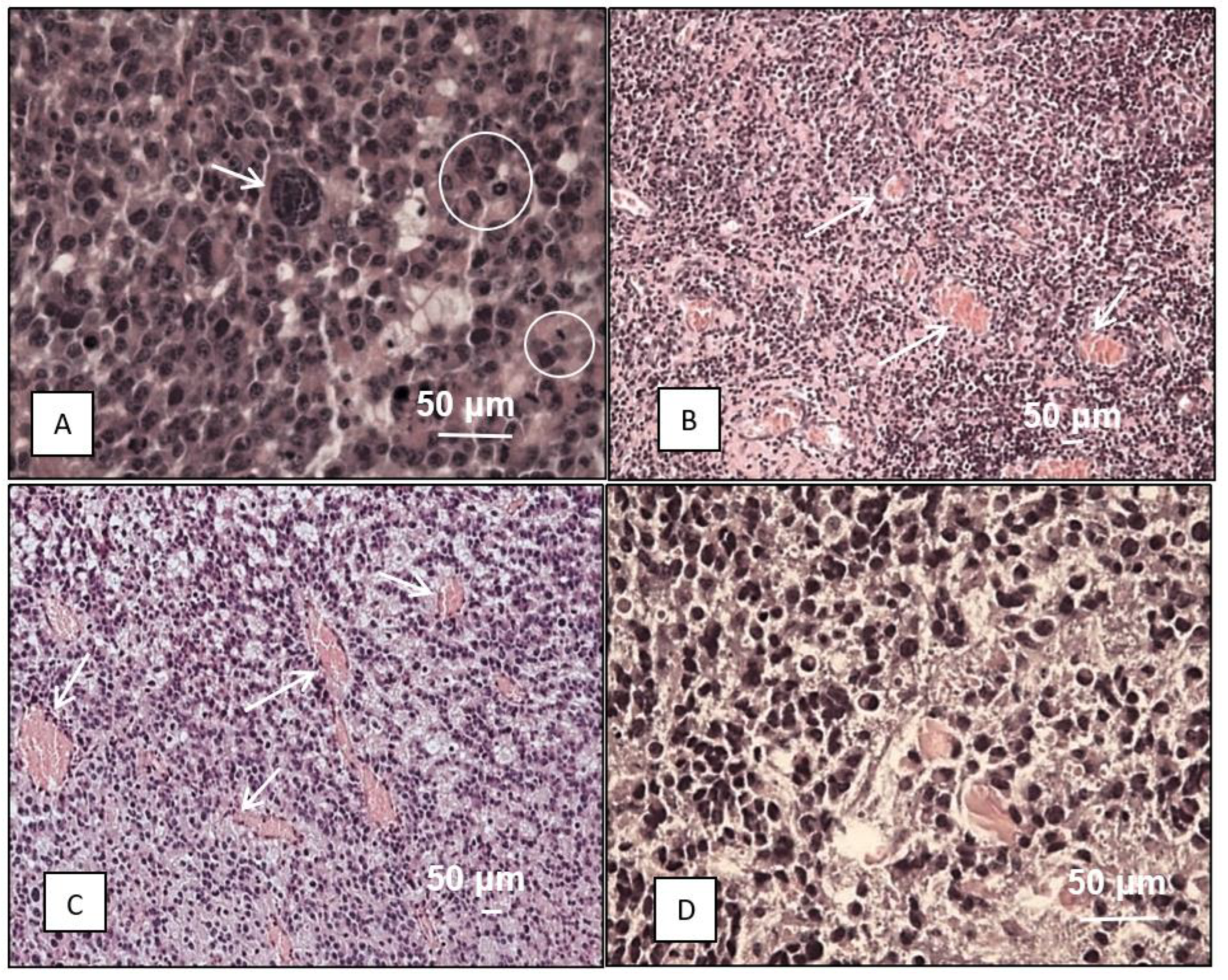

3. Results and Discussion

| Gene | Function | Brain tissue (n=6) | М2 GB tissue (n=6) |

М6 GB tissue (n=6) |

Statistical significance: |

Human GB, References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd44 | Cell adhesion, neurotrophic factor | 9 (4; 32) |

7 (6; 11) |

39 (36; 55) |

0.002*** | ↑[40] |

| S100b | 126 (49; 897) |

9155 (6851; 1429) |

1742 (1204; 3406) |

0.000*; 0.041** | ↑[41] | |

| Pi3k | Angiogenesis, differentiation, transcription | 45 (35; 70) |

105 (87; 155) |

301 (229; 900) |

0.000**; 0.007*** | ↑[42] |

| Vegfa | 51 (36; 423) |

2109 (1242; 4244) |

8269 (8; 11877) |

0.033*; 0.015** | ↑[43] | |

| Cdkn2a | Cell cycle, apoptosis, transcription, lipid metabolism, neurogenesis | 19 (3; 38) |

68721 (43328; 84452) |

10496 (9155; 15291) |

0.000*; 0.047**; 0.010*** | ↓[44] |

| Tp53 | 1141 (770; 1458) |

93397 (5336; 22744) |

40 (25; 201) |

0.004*; 0.000*** | - [45] | |

| Mki67 | 9 (2; 16) |

4410 (1972; 7018) |

747 (539; 1285) |

0.000*; 0.032** | - [46] | |

| Pten | 424 (272; 1011) |

5301 (2633; 6966) |

6736 (4548; 16931) |

0.000*; 0.000** | ↓[47] | |

| Hif1a | Transcription | 245 (133; 375) |

2269 (1402; 2725) |

5876 (4951; 7018 |

0.006*; 0.000**; 0.046*** | ↑[48] |

| Sox2 | 1029 (358; 2219) |

5876 (3967; 7018) |

12060 (10322; 17055) |

0.009*; 0.000** | ↓[49] | |

| Cd133 | Differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis | 82 (35; 88) |

168 (137; 218) |

36 (25; 42) |

0.020*; 0.000*** | - [50] |

| Pdgfra | Growth factor, chemotaxis | 71 (30; 296) |

505 (276; 773) |

43 (29; 68) |

0.009*; 0.000*** | ↑[51] |

| Gdnf | Growth factor | 3 (2; 5) |

16 (9; 26) |

1065 (586; 1376) |

0.000**; 0.001*** | ↑[52] |

| Mgmt | DNA damage/repair | 23 (2; 96) |

30 (9; 73) |

31 (16; 47) |

> 0.05 | ↑[53] |

| Abcb1 | Cellular transport | 33 (27; 53) |

302 (245; 426) |

596 (523; 968) |

0.002*; 0.000** | - [54] |

| Gfap | Glioma-associated | 281 (35; 1554) |

2702 (1051; 5301) |

6736 (4548; 12104) |

0.05*; 0.000** | ↑[55] |

| Egfr | Proliferation | 14 (5; 26) |

1 (0.4; 1) |

27 (5; 110) |

0.011*** | ↑ [56] |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu: W.; Klockow, J.L.; Zhang, M.; Lafortune, F.; Chang, E.; Jin, L.; Wu, Y.; Daldrup-Link, H.E. Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM): An overview of current therapies and mechanisms of resistance. Pharmacological research 2021, 171, 105780. [CrossRef]

- McInnes, E.F. Background lesions in laboratory animals. A Color Atlas. Book. Elsevier Ltd., USA. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Lampreht Tratar, U.; Horvat, S.; Cemazar, M. Transgenic Mouse Models in Cancer Research. Frontiers in oncology 2018, 8, 268. [CrossRef]

- Ireson, C.R.; Alavijeh, M.S.; Palmer, A.M.; Fowler, E.R.; Jones, H.J. The role of mouse tumour models in the discovery and development of anticancer drugs. British journal of cancer 2019, 121, 2, 101–108. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, U.; Barth, R.F.; Otani, Y.; McCormack, R.; Kaur, B. Rat and Mouse Brain Tumor Models for Experimental Neuro-Oncology Research. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology 2022, 81(5), 312–329. [CrossRef]

- Haddad, A.F.; Young, J.S.; Amara, D.; Berger, M.S.; Raleigh, D.R.; Aghi, M.K.; Butowski, N.A. Mouse models of glioblastoma for the evaluation of novel therapeutic strategies. Neuro-oncology advances 2021, 3, 1, vdab100. [CrossRef]

- Lowenstein, P.R.; Castro, M.G. Uncertainty in the translation of preclinical experiments to clinical trials. Why do most phase III clinical trials fail? Current gene therapy 2009, 9, 5, 368–374. [CrossRef]

- Fogel, D.B. Factors associated with clinical trials that fail and opportunities for improving the likelihood of success: A review. Contemporary clinical trials communications 2018, 11, 156–164. [CrossRef]

- Mirzayans, R.; Murray, D. What Are the Reasons for Continuing Failures in Cancer Therapy? Are Misleading/Inappropriate Preclinical Assays to Be Blamed? Might Some Modern Therapies Cause More Harm than Benefit? International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23, 21, 13217. [CrossRef]

- Arutyunyan, I.V.; Soboleva, A.G.; Kovtunov, E.A.; Kosyreva, A.M.; Kudelkina, V.V.; Alekseeva, A.I.; Elchaninov, A.V.; Jumaniyazova, E.D.; Goldshtein, D.V.; Bolshakova, G.B.; Fatkhudinov, T.K. Gene Expression Profile of 3D Spheroids in Comparison with 2D Cell Cultures and Tissue Strains of Diffuse High-Grade Gliomas. Bulletin of experimental biology and medicine 2023, 175, 4, 576–584. [CrossRef]

- Neuroscience for medicine and psychology: abstracts of reports XIX international interdisciplinary congress. Sudak, Russia, 2023, 34-35. [CrossRef]

- Paster, E.V.; Villines, K.A.; Hickman, D.L. Endpoints for mouse abdominal tumor models: refinement of current criteria. Comparative medicine 2009, 59, 3, 234–241.

- Fedoseeva, V.V.; Khalansky, A.S.; Mkhitarov, V.A.; Tsvetkov, I.S.; Malinovskaya, Y.A.; et al. Anti-tumor activity of doxorubicin-loaded poly(lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles in the experimental glioblastoma. Klini. i Eksperimental. Morfolog 2017, 2, 22, 65–71. http://www.stm-journal.ru/en/numbers/2018/4/1485/pdf.

- Pfaffl, M.W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic acids research 2001, 29(9), e45. [CrossRef]

- Vandesompele, J.; De Preter, K.; Pattyn, F.; Poppe, B.; Van Roy, N.; De Paepe, A.; Speleman, F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome biology 2002, 3(7). [CrossRef]

- Goldman, O.; Adler, L.N.; Hajaj, E.; Croese, T.; Darzi, N.; Galai, S.; Tishler, H.; Ariav, Y.; Lavie, D.; Fellus-Alyagor, L.; Oren, R.; Kuznetsov, Y.; David, E.; Jaschek, R.; Stossel, C.; Singer, O.; Malitsky, S.; Barak, R.; Seger, R.; Erez, N.; Erez, A. Early Infiltration of Innate Immune Cells to the Liver Depletes HNF4α and Promotes Extrahepatic Carcinogenesis. Cancer discovery 2023, 13, 7, 1616–1635. [CrossRef]

- Law, M.L. Cancer cachexia: Pathophysiology and association with cancer-related pain. Frontiers in pain research (Lausanne, Switzerland) 2022, 3, 971295. [CrossRef]

- Olson, B.; Diba, P.; Korzun, T.; Marks, D.L. Neural Mechanisms of Cancer Cachexia. Cancers 2021, 13, 16, 3990. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Jina, H.; Rathore, P.; Wong, E.L.; Mancuso, P.; Lalak, N.; Hayden, L.; Haghighi, K. A Case Report of Priapism with unusual presentation and clinical course. Urology case reports 2017, 12, 70–72. [CrossRef]

- Shelton, L.M.; Mukherjee, P.; Huysentruyt, L.C.; Urits, I.; Rosenberg, J.A.; Seyfried, T.N. A novel pre-clinical in vivo mouse model for malignant brain tumor growth and invasion. Journal of neuro-oncology 2010, 99(2), 165–176. [CrossRef]

- Cui, P.; Shao, W.; Huang, C.; Wu, C.J.; Jiang, B.; Lin, D. Metabolic derangements of skeletal muscle from a murine model of glioma cachexia. Skeletal muscle 2019, 9(1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, R.Q.; Lima, L.G.; Gonçalves, N.P.; DE Souza, M.R.; Leal, A.C.; Demasi, M.A.; Sogayar, M.C.; Carneiro-Lobo, T.C. Hypoxia regulates the expression of tissue factor pathway signaling elements in a rat glioma model. Oncology letters 2016, 12(1), 315–322. [CrossRef]

- Onizuka, H.; Masui, K.; Komori, T. Diffuse gliomas to date and beyond 2016 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. International journal of clinical oncology 2020, 25(6), 997–1003. [CrossRef]

- Himes, B.T.; Geiger, P. A.; Ayasoufi, K.; Bhargav, A.G.; Brown, D.A.; Parney, I.F. Immunosuppression in Glioblastoma: Current Understanding and Therapeutic Implications. Frontiers in oncology 2021, 11, 770561. [CrossRef]

- Alghamri, M.S.; McClellan, B.L.; Hartlage, C.S.; Haase, S.; Faisal, S.M.; Thalla, R.; Dabaja, A.; Banerjee, K.; Carney, S.V.; Mujeeb, A.A.; Olin, M.R.; Moon, J.J.; Schwendeman, A.; Lowenstein, P.; Castro, M.G. Targeting Neuroinflammation in Brain Cancer: Uncovering Mechanisms, Pharmacological Targets, and Neuropharmaceutical Developments. Frontiers in pharmacology 2021, 12, 680021. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.K.; Miletic, H.; Hossain, J.A. Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Gliomas-Basic Insights and Treatment Opportunities. Cancers 2022, 14, 5, 1319. [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, P.B.; Mathivet, T.; Alt, S.; Giese, W.; Riva, M.; Balcer, M.; Gerhardt, H. Long-lived tumor-associated macrophages in glioma. Neuro-oncology advances 2020, 2(1), vdaa127. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.F.; Camacho, A.H.D.S.; Spohr, T.C.L.S.E. Secondary glioblastoma metastasis outside the central nervous system in a young HIV-infected patient. Therapeutic advances in medical oncology 2020, 12, 1758835920923432. [CrossRef]

- Chongsathidkiet, P.; Jackson, C.; Koyama, S.; Loebel, F.; Cui, X.; Farber, S.H.; Woroniecka, K.; Elsamadicy, A.A.; Dechant, C.A.; Kemeny, H.R.; Sanchez-Perez, L.; Cheema, T.A.; Souders, N.C.; Herndon, J.E.; Coumans, J.V.; Everitt, J.I.; Nahed, B.V.; Sampson, J.H.; Gunn, M.D.; Martuza, R.L.; Fecci, P.E. Sequestration of T cells in bone marrow in the setting of glioblastoma and other intracranial tumors. Nature medicine 2018, 24(9), 1459–1468. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, V.E.; Lynes, J.P.; Walbridge, S.; Wang, X.; Edwards, N.A.; Nwankwo, A.K.; Sur, H.P.; Dominah, G.A.; Obungu, A.; Adamstein, N.; Dagur, P.K.; Maric, D.; Munasinghe, J.; Heiss, J.D.; Nduom, E.K. GL261 luciferase-expressing cells elicit an anti-tumor immune response: an evaluation of murine glioma models. Scientific reports 2020, 10(1), 11003, . [CrossRef]

- Akkari, L.; Bowman, R.L.; Tessier, J.; Klemm, F.; Handgraaf, S.M.; de Groot, M.; Quail, D.F.; Tillard, L.; Gadiot, J.; Huse, J.T.; Brandsma, D.; Westerga, J.; Watts, C.; Joyce, J.A. Dynamic changes in glioma macrophage populations after radiotherapy reveal CSF-1R inhibition as a strategy to overcome resistance. Science translational medicine 2020, 12(552), eaaw7843. [CrossRef]

- Maire, C.L.; Mohme, M.; Bockmayr, M.; Fita, K.D.; Riecken, K.; Börnigen, D.; Alawi, M.; Failla, A.; Kolbe, K.; Zapf, S.; Holz, M.; Neumann, K.; Dührsen, L.; Lange, T.; Fehse, B.; Westphal, M.; Lamszus, K. Glioma escape signature and clonal development under immune pressure. The Journal of clinical investigation 2020, 130(10), 5257–5271. [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.E.; Hibbard, J.C.; Alizadeh, D.; Blanchard, M.S.; Natri, H.M.; Wang, D.; Ostberg, J.R.; Aguilar, B.; Wagner, J.R.; Paul, J.A.; Starr, R., Wong, R.A.; Chen, W.; Shulkin, N.; Aftabizadeh, M.; Filippov, A.; Chaudhry, A.; Ressler, J.A.; Kilpatrick, J.; Myers-McNamara, P.; Badie, B. Locoregional delivery of IL-13Rα2-targeting CAR-T cells in recurrent high-grade glioma: a phase 1 trial. Nature medicine 2024, 30(4), 1001–1012. [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, N.; Bouchè, V.; Aldegheri, G.; Rocca, A.; D'Angelo, A.; Giudici, F.; Bottin, C.; Donofrio, C.A.; Pinamonti, M.; Ferrari, B.; Panni, S.; Cominetti, M.; Aliaga, J.; Ungari, M.; Fioravanti, A.; Zanconati, F.; Generali, D. Analysis of PD-L1 and CD3 Expression in Glioblastoma Patients and Correlation with Outcome: A Single Center Report. Biomedicines 2023, 11(2), 311. [CrossRef]

- van Hooren, L.; Handgraaf, S.M.; Kloosterman, D.J.; Karimi, E.; van Mil, L.W.H.G.; Gassama, A.A.; Solsona, B.G.; de Groot, M.H.P.; Brandsma, D.; Quail, D.F.; Walsh, L.A.; Borst, G.R.; Akkari, L. CD103+ regulatory T cells underlie resistance to radio-immunotherapy and impair CD8+T cell activation in glioblastoma. Nature cancer 2023, 4(5), 665–681. [CrossRef]

- Musca, B.; Russo, M.G.; Tushe, A.; Magri, S.; Battaggia, G.; Pinton, L.; Bonaudo, C.; Della Puppa, A.; Mandruzzato, S. The immune cell landscape of glioblastoma patients highlights a myeloid-enriched and immune suppressed microenvironment compared to metastatic brain tumors. Frontiers in immunology 2023, 14, 1236824. [CrossRef]

- Enríquez Pérez, J.; Kopecky, J.; Visse, E.; Darabi, A.; Siesjö, P. Convection-enhanced delivery of temozolomide and whole cell tumor immunizations in GL261 and KR158 experimental mouse gliomas. BMC cancer 2020, 20(1), 7. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.C.; Hong, J.H.; Hsueh, C.; Chiang, C.S. Tumor-secreted SDF-1 promotes glioma invasiveness and TAM tropism toward hypoxia in a murine astrocytoma model. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology 2012, 92(1), 151–162. [CrossRef]

- Kamran, N.; Kadiyala, P.; Saxena, M.; Candolfi, M.; Li, Y.; Moreno-Ayala, M.A.; Raja, N.; Shah, D.; Lowenstein, P.R.; Castro, M.G. Immunosuppressive Myeloid Cells' Blockade in the Glioma Microenvironment Enhances the Efficacy of Immune-Stimulatory Gene Therapy. Molecular therapy: the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy 2017, 25(1), 232–248. [CrossRef]

- Inoue, A.; Ohnishi, T.; Nishikawa, M.; Watanabe, H.; Kusakabe, K.; Taniwaki, M.; Yano, H.; Ohtsuka, Y.; Matsumoto, S.; Suehiro, S.; et al. Identification of CD44 as a Reliable Biomarker for Glioblastoma Invasion: Based on Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Spectroscopic Analysis of 5-Aminolevulinic Acid Fluorescence. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2369. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.J.; Lv, P.; Lou, Y. Alarm Signal S100-Related Signature Is Correlated with Tumor Microenvironment and Predicts Prognosis in Glioma. Disease markers 2022, 4968555. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Zuo, F.X.; Cai, H.Q.; Qian, H.P.; Wan, J.H. Identifying Differential Expression Genes and Prognostic Signature Based on Subventricular Zone Involved Glioblastoma. Frontiers in genetics 2022, 13, 912227. [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Xu, S.; Zhong, Y.; Tu, T.; Xu, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, B.; Yang, F. High gene expression levels of VEGFA and CXCL8 in the peritumoral brain zone are associated with the recurrence of glioblastoma: A bioinformatics analysis. Oncology letters 2019, 18(6), 6171–6179. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Lv, G.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, B. Downregulation of CDKN2A and suppression of cyclin D1 gene expressions in malignant gliomas. Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research: CR 2011, 30(1), 76. [CrossRef]

- Shiraishi, S.; Tada, K.; Nakamura, H.; Makino, K.; Kochi, M.; Saya, H.; Kuratsu, J.; Ushio, Y. Influence of p53 mutations on prognosis of patients with glioblastoma. Cancer 2002, 95(2), 249–257. [CrossRef]

- Dahlrot, R.H.; Bangsø, J.A.; Petersen, J.K.; Rosager, A.M.; Sørensen, M.D.; Reifenberger, G.; Hansen, S.; Kristensen, B.W. Prognostic role of Ki-67 in glioblastomas excluding contribution from non-neoplastic cells. Scientific reports 2021, 11(1), 17918. [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, M.; Etemad, S.; Rezaei, S.; Ziaolhagh, S.; Rajabi, R.; Rahmanian, P.; Abdi, S.; Koohpar, Z.K.; Rafiei, R.; Raei, B.; Ahmadi, F.; Salimimoghadam, S.; Aref, A.R.; Zandieh, M.A.; Entezari, M.; Taheriazam, A.; Hushmandi, K. Progress in targeting PTEN/PI3K/Akt axis in glioblastoma therapy: Revisiting molecular interactions. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie 2023, 158, 114204. [CrossRef]

- Sfifou, F.; Hakkou, E.M.; Bouaiti, E.A.; Slaoui, M.; Errihani, H.; Al Bouzidi, A.; Abouqal, R.; El Ouahabi, A.; Cherradi, N. Correlation of immunohistochemical expression of HIF-1alpha and IDH1 with clinicopathological and therapeutic data of moroccan glioblastoma and survival analysis. Annals of medicine and surgery 2021, 69, 102731. [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Ren, X.; Hu; C.; Tan, Y.; Shui, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, L.; Peng, J.; Wei, Q. Glioma SOX2 expression decreased after adjuvant therapy. BMC cancer 2019, 19(1), 1087. [CrossRef]

- Abdoli Shadbad, M.; Nejadi Orang, F.; Baradaran, B. CD133 significance in glioblastoma development: in silico and in vitro study. European journal of medical research 2024, 29(1), 154. [CrossRef]

- Farsi, Z.; Allahyari Fard, N. The identification of key genes and pathways in glioblastoma by bioinformatics analysis. Molecular & cellular oncology 2023, 10(1), 2246657. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, M.; Luo, W.; Xue, Y. GDNF regulates lipid metabolism and glioma growth through RET/ERK/HIF-1/SREBP-1. International journal of oncology 2022, 61(3), 109. [CrossRef]

- Szylberg, M.; Sokal, P.; Śledzińska, P.; Bebyn, M.; Krajewski, S.; Szylberg, Ł.; Szylberg, A.; Szylberg, T.; Krystkiewicz, K.; Birski, M.; Harat, M.; Włodarski, R.; Furtak, J. MGMT Promoter Methylation as a Prognostic Factor in Primary Glioblastoma: A Single-Institution Observational Study. Biomedicines 2022, 10(8), 2030. [CrossRef]

- Roy, L.O.; Lemelin, M.; Blanchette, M.; Poirier, M.B.; Aldakhil, S.; Fortin, D. Expression of ABCB1, ABCC1 and 3 and ABCG2 in glioblastoma and their relevance in relation to clinical survival surrogates. Journal of neuro-oncology 2022, 160(3), 601–609. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadipour, Y.; Gembruch, O.; Pierscianek, D.; Sure, U.; Jabbarli, R. Does the expression of glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP) stain in glioblastoma tissue have a prognostic impact on survival? Neuro-Chirurgie 2020, 66(3), 150–154. [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, A.; Manem, V.S.K.; Yeaney, G.; Lathia, J.D.; Ahluwalia, M.S. EGFR Pathway Expression Persists in Recurrent Glioblastoma Independent of Amplification Status. Cancers 2023, 15(3), 670. [CrossRef]

- Nasti, T.H.; Cochran, J.B.; Tsuruta, Y.; Yusuf, N.; McKay, K.M.; Athar, M.; Timares, L.; Elmets, C.A. A murine model for the development of melanocytic nevi and their progression to melanoma. Molecular carcinogenesis 2016, 55, 5, 646–658. [CrossRef]

- Todorova, V.K.; Kaufmann, Y.; Luo, S.; Klimberg, V.S. Modulation of p53 and c-myc in DMBA-induced mammary tumors by oral glutamine. Nutrition and cancer 2006, 54, 2, 263–273. [CrossRef]

- Fidianingsih, I.; Aryandono, T.; Widyarini, S.; Herwiyanti, S. Profile of Histopathological Type and Molecular Subtypes of Mammary Cancer of DMBA-induced Rat and its Relevancy to Human Breast Cancer. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences 2022, 10, A, 71–78. [CrossRef]

- Robbins, D.; Wittwer, J.A.; Codarin, S.; Circu, M.L.; Aw, T.Y.; Huang, T.T.; Van Remmen, H.; Richardson, A.; Wang, D.B.; Witt, S.N.; Klein, R. L.; Zhao, Y. Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 is downregulated during early skin tumorigenesis which can be inhibited by overexpression of manganese superoxide dismutase. Cancer science 2012, 103, 8, 1429–1433. [CrossRef]

- Mallick, S. Evidence based practice in Neuro-oncology ISBN 978-981-16-2658-6 ISBN 978-981-16-2659-3. Springer Nature 2021, Singapore. Pte Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Marker, D.F.; Agnihotri, S.; Amankulor, N.; Murdoch, G.H.; Pearce, T.M. The dominant TP53 hotspot mutation in IDH -mutant astrocytoma, R273C, has distinctive pathologic features and sex-specific prognostic implications. Neuro-oncology advances 2021, 4, 1, vdab182. [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.; Pongor, L.; Su, Y.T.; Xi, L.; Raffeld, M.; Quezado, M.; Trepel, J.; Aldape, K.; Pommier, Y.; Wu, J. MGMT Status as a Clinical Biomarker in Glioblastoma. Trends in cancer 2020, 6(5), 380–391. [CrossRef]

- Ohtsuki, S.; Kamoi, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Hori, S.; Terasaki, T. Correlation of induction of ATP binding cassette transporter A5 (ABCA5) and ABCB1 mRNAs with differentiation state of human colon tumor. Biological & pharmaceutical bulletin 2007, 30, 6, 1144–1146. [CrossRef]

- Oda, Y.; Saito, T.; Tateishi, N.; Ohishi, Y.; Tamiya, S.; Yamamoto, H.; Yokoyama, R.; Uchiumi, T.; Iwamoto, Y.; Kuwano, M.; Tsuneyoshi, M. ATP-binding cassette superfamily transporter gene expression in human soft tissue sarcomas. International journal of cancer 2005, 114(6), 854–862. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Khan, H.; Aschner, M.; Mirzae, H.; Küpeli Akkol, E.; Capasso, R. Anticancer Potential of Furanocoumarins: Mechanistic and Therapeutic Aspects. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21, 16, 5622. [CrossRef]

- Robey, R.W.; Massey, P.R.; Amiri-Kordestani, L.; Bates, S.E. ABC transporters: unvalidated therapeutic targets in cancer and the CNS. Anti-cancer agents in medicinal chemistry 2010, 10(8), 625–633. [CrossRef]

- Amiri-Kordestani, L.; Basseville, A.; Kurdziel, K.; Fojo, A. T.; Bates, S.E. Targeting MDR in breast and lung cancer: discriminating its potential importance from the failure of drug resistance reversal studies. Drug resistance updates: reviews and commentaries in antimicrobial and anticancer chemotherapy 2012, 15, 1-2, 50–61. [CrossRef]

- Uhlén, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallström, B.M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Sivertsson, Å.; Kampf, C.; Sjöstedt, E.; Asplund, A.; Olsson, I.; Edlund, K.; Lundberg, E.; Navani, S.; Szigyarto, C.A.; Odeberg, J.; Djureinovic, D.; Takanen, J.O.; Hober, S.; Alm, T.; Pontén, F. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2015, 347, 6220, 1260419. [CrossRef]

- Suba, Z. Rosetta Stone for Cancer Cure: Comparison of the Anticancer Capacity of Endogenous Estrogens, Synthetic Estrogens and Antiestrogens. Oncology reviews 2023, 17, 10708. [CrossRef]

- Padovan, M.; Maccari, M.; Bosio, A.; De Toni, C.; Vizzaccaro, S.; Cestonaro, I.; Corrà, M.; Caccese, M.; Cerretti, G.; Zagonel, V.; Lombardi, G. Actionable molecular alterations in newly diagnosed and recurrent IDH1/2 wild-type glioblastoma patients and therapeutic implications: a large mono-institutional experience using extensive next-generation sequencing analysis. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 2023, 191, 112959. [CrossRef]

- Huszno, J.; Grzybowska, E. TP53 mutations and SNPs as prognostic and predictive factors in patients with breast cancer. Oncology letters 2018, 16, 1, 34–40. [CrossRef]

- Robertson, L.B.; Armstrong, G.N.; Olver, B.D.; Lloyd, A.L.; Shete, S.; Lau, C.; Claus, E.B.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.; Lai, R.; Il'yasova, D.; Schildkraut, J.; Bernstein, J.L.; Olson, S.H.; Jenkins, R.B.; Yang, P.; Rynearson, A.L.; Wrensch, M.; McCoy, L.; Wienkce, J.K.; McCarthy, B.; Houlston, R.S. Survey of familial glioma and role of germline p16INK4A/p14ARF and p53 mutation. Familial cancer 2010, 9, 3, 413–421. [CrossRef]

- Maltzman, W.; Czyzyk, L. UV irradiation stimulates levels of p53 cellular tumor antigen in nontransformed mouse cells. Molecular and cellular biology 1984, 4, 9, 1689–1694. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.K.; Park, S.; Pentek, C.; Liebman, S.W. Tumor suppressor protein p53 expressed in yeast can remain diffuse, form a prion, or form unstable liquid-like droplets. iScience 2020, 24, 1, 102000. [CrossRef]

- Navalkar, A.; Ghosh, S.; Pandey, S.; Paul, A.; Datta, D.; Maji, S.K. Prion-like p53 Amyloids in Cancer. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 2, 146–155. [CrossRef]

- Levine, A.J.; Puzio-Kuter, A.M.; Chan, C.S.; Hainaut, P. The Role of the p53 Protein in Stem-Cell Biology and Epigenetic Regulation. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine 2016, 6(9), a026153. [CrossRef]

- Hill, K.A.; Sommer, S.S. p53 as a mutagen test in breast cancer. Environmental and molecular mutagenesis 2002, 39, 2-3, 216–227. [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, S.; Paskeh, M.D.A.; Entezari, M.; Mirmazloomi, S.R.; Hassanpoor, A.; Aboutalebi, M.; Rezaei, S.; Hejazi, E.S.; Kakavand, A.; Heidari, H.; Salimimoghadam, S.; Taheriazam, A.; Hashemi, M.; Samarghandian, S. SOX2 function in cancers: Association with growth, invasion, stemness and therapy response. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie 2022, 156, 113860. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Huang, S.; Chen, S.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, H. SOX2 promotes chemoresistance, cancer stem cells properties, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition by β-catenin and Beclin1/autophagy signaling in colorectal cancer. Cell death & disease 2021, 12, 5, 449. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xiong, X.; Sun, Y. Functional characterization of SOX2 as an anticancer target. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2020, 5, 135. [CrossRef]

- Abatti, L.E.; Lado-Fernández, P.; Huynh, L.; Collado, M.; Hoffman, M. M.; Mitchell, J.A. Epigenetic reprogramming of a distal developmental enhancer cluster drives SOX2 overexpression in breast and lung adenocarcinoma. Nucleic acids research 2023, 51, 19, 10109–10131. [CrossRef]

- Bao, L.; Li, X.; Lin, Z. PTEN overexpression promotes glioblastoma death through triggering mitochondrial division and inactivating the Akt pathway. Journal of receptor and signal transduction research 2019, 39, 3, 215–225. [CrossRef]

- Yokoi, A.; Minami, M.; Hashimura, M.; Oguri, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Hasegawa, Y.; Nakagawa, M.; Ishibashi, Y.; Ito, T.; Ohhigata, K.; Harada, Y.; Fukagawa, N.; Saegusa, M. PTEN overexpression and nuclear β-catenin stabilization promote morular differentiation through induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cell-like properties in endometrial carcinoma. Cell communication and signaling: CCS 2022, 20, 1, 181. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, J.; Su, Y.; Hou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Sun, S.; Fu, H. Overexpression of PTEN may increase the effect of pemetrexed on A549 cells via inhibition of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and carbohydrate metabolism. Molecular medicine reports 2019, 20, 4, 3793–3801. [CrossRef]

- Romagosa, C.; Simonetti, S.; López-Vicente, L.; Mazo, A.; Leonart, M.E.; Castellvi, J.; Ramon y Cajal, S. p16(Ink4a) overexpression in cancer: a tumor suppressor gene associated with senescence and high-grade tumors. Oncogene 2011, 30, 18, 2087–2097. [CrossRef]

- Yehia, L.; Keel, E.; Eng, C. The Clinical Spectrum of PTEN Mutations. Annual review of medicine 2020, 71, 103–116. [CrossRef]

- Cabrita, R.; Mitra, S.; Sanna, A.; Ekedahl, H.; Lövgren, K.; Olsson, H.; Ingvar, C.; Isaksson, K.; Lauss, M.; Carneiro, A.; Jönsson, G. The Role of PTEN Loss in Immune Escape, Melanoma Prognosis and Therapy Response. Cancers 2020, 12, 3, 742. [CrossRef]

- Pentheroudakis, G.; Mavroeidis, L.; Papadopoulou, K.; Koliou, G.A.; Bamia, C.; Chatzopoulos, K.; Samantas, E.; Mauri, D.; Efstratiou, I.; Pectasides, D.; Makatsoris, T.; Bafaloukos, D.; Papakostas, P.; Papatsibas, G.; Bombolaki, I.; Chrisafi, S.; Kourea, H.P.; Petraki, K.; Kafiri, G.; Fountzilas, G.; Kotoula, V. Angiogenic and Antiangiogenic VEGFA Splice Variants in Colorectal Cancer: Prospective Retrospective Cohort Study in Patients Treated With Irinotecan-Based Chemotherapy and Bevacizumab. Clinical colorectal cancer 2019, 18, 4, e370–e384. [CrossRef]

- GDNF glial cell derived neurotrophic factor https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/2668 (available 26.05.24).

- Vora, P.; Venugopal, C.; Salim, S.K.; Tatari, N.; Bakhshinyan, D.; Singh, M.; Seyfrid, M.; Upreti, D.; Rentas, S.; Wong, N.; Williams, R.; Qazi, M.A.; Chokshi, C.; Ding, A.; Subapanditha, M.; Savage, N.; Mahendram, S.; Ford, E.; Adile, A.A.; McKenna, D.; Singh, S. The Rational Development of CD133-Targeting Immunotherapies for Glioblastoma. Cell stem cell 2020, 26, 6, 832–844.e6. [CrossRef]

- Irollo, E.; Pirozzi, G. CD133: to be or not to be, is this the real question?.American journal of translational research 2013, 5, 6, 563–581.

- Razmara, M.; Heldin, CH.; Lennartsson, J. Platelet-derived growth factor-induced Akt phosphorylation requires mTOR/Rictor and phospholipase C-γ1, whereas S6 phosphorylation depends on mTOR/Raptor and phospholipase D. Cell Commun Signal 2013, 11, 3. [CrossRef]

- Ostendorp, T.; Diez, J.; Heizmann, C.W.; Fritz, G. The crystal structures of human S100B in the zinc- and calcium-loaded state at three pH values reveal zinc ligand swapping. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2011, 1813, 5, 1083–1091. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Mao, X.; Ye, L.; Cheng, H.; Dai, X. The Role of the S100 Protein Family in Glioma. Journal of Cancer 2022, 13, 10, 3022–3030. [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Stephen, C.W.; Luciani, M.G.; Fåhraeus, R. p53 Stability and activity is regulated by Mdm2-mediated induction of alternative p53 translation products. Nature cell biology 2002, 4, 6, 462–467. [CrossRef]

- Marcel, V.; Perrier, S.; Aoubala, M.; Ageorges, S.; Groves, M.J.; Diot, A.; Fernandes, K.; Tauro, S.; Bourdon, J.C. Δ160p53 is a novel N-terminal p53 isoform encoded by Δ133p53 transcript. FEBS letters 2010, 584, 21, 4463–4468. [CrossRef]

- Pienkowski, T., Kowalczyk, T., Cysewski, D., Kretowski, A., Ciborowski, M. Glioma and post-translational modifications: A complex relationship. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Reviews on cancer 2023, 1878(6), 189009. [CrossRef]

- Perl, K.; Ushakov, K.; Pozniak, Y.; Yizhar-Barnea, O.; Bhonker, Y.; Shivatzki, S.; Geiger, T.; Avraham, K.B.; Shamir, R. Reduced changes in protein compared to mRNA levels across non-proliferating tissues. BMC genomics 2017, 18, 1, 305. [CrossRef]

- Plante I. Dimethylbenz(a)anthracene-induced mammary tumorigenesis in mice. Methods in cell biology 2021, 163, 21–44. [CrossRef]

- Avtsyn A.P. Staroe i novoe v uchenii o predglome [Old and new concepts in the teaching on preglioma]. Arkhiv patologii 1972, 34(11), 3–11.

- Kucheryavenko, A.S.; Chernomyrdin, N.V.; Gavdush, A.A.; Alekseeva, A.I.; Nikitin, P.V.; Dolganova, I.N.; Karalkin, P.A.; Khalansky, A.S.; Spektor, I.E.; Skorobogatiy, M.; Tuchin, V.V.; Zaytsev, K.I. tissue heterogeneity. Biomedical optics express 2021, 12(8), 5272–5289. [CrossRef]

- Dolganova, I.N.; Aleksandrova, P.V.; Nikitin, P.V.; Alekseeva, A.I.; Chernomyrdin, N.V.; Musina, G.R.; Beshplav, S.T.; Reshetov, I.V.; Potapov, A.A.; Kurlov, V.N.; Tuchin, V.V.; Zaytsev, K.I. Capability of physically reasonable OCT-based differentiation between intact brain tissues, human brain gliomas of different WHO. grades, and glioma model 101.8 from rats. Biomedical optics express 2020, 11(11), 6780–6798. [CrossRef]

- Kiseleva, E.B.; Yashin, K.S.; Moiseev, A.A.; Timofeeva, L.B.; Kudelkina, V.V.; Alekseeva, A.I.; Meshkova, S.V.; Polozova, A.V.; Gelikonov, G.V.; Zagaynova, E.V.; Gladkova, N.D. Optical coefficients as tools for increasing the optical coherence tomography contrast for normal brain visualization and glioblastoma detection. Neurophotonics 2019, 6(3), 035003. [CrossRef]

- Maksimenko, O.; Malinovskaya, J.; Shipulo, E.; Osipova, N.; Razzhivina, V.; Arantseva, D.; Yarovaya, O.; Mostovaya, U.; Khalansky, A.; Fedoseeva, V.; Alekseeva, A.; Vanchugova, L.; Gorshkova, M.; Kovalenko, E.; Balabanyan, V.; Melnikov, P.; Baklaushev, V.; Chekhonin, V.; Kreuter, J.; Gelperina, S. International journal of pharmaceutics 2019, 572, 118733. [CrossRef]

- Dzhalilova, D.S.; Zolotova, N.A.; Mkhitarov, V.A.; Kosyreva, A.M.; Tsvetkov, I.S.; Khalansky, A.S.; Alekseeva, A.I.; Fatkhudinov, T.H.; Makarova, O.V. Morphological and molecular-biological features of glioblastoma progression in tolerant and susceptible to hypoxia Wistar rats. Scientific reports 2023, 13(1), 12694. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).