Submitted:

02 April 2025

Posted:

03 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Research Aim

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Building Intervention Categories

3.2. Selection of Publications

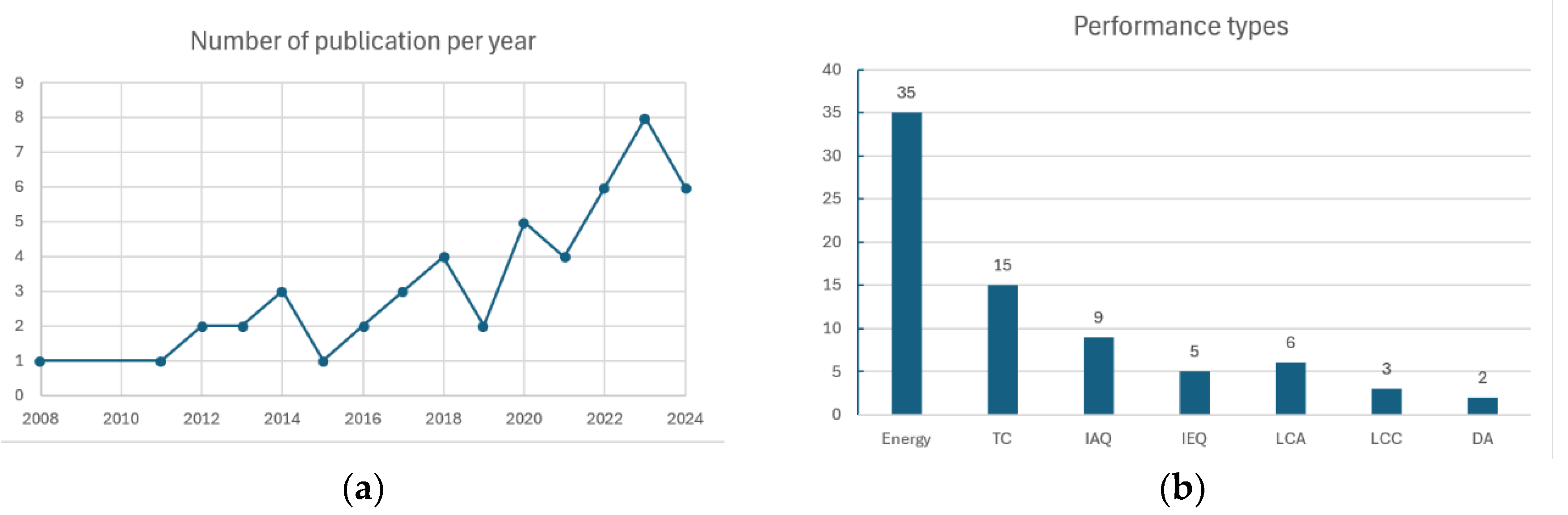

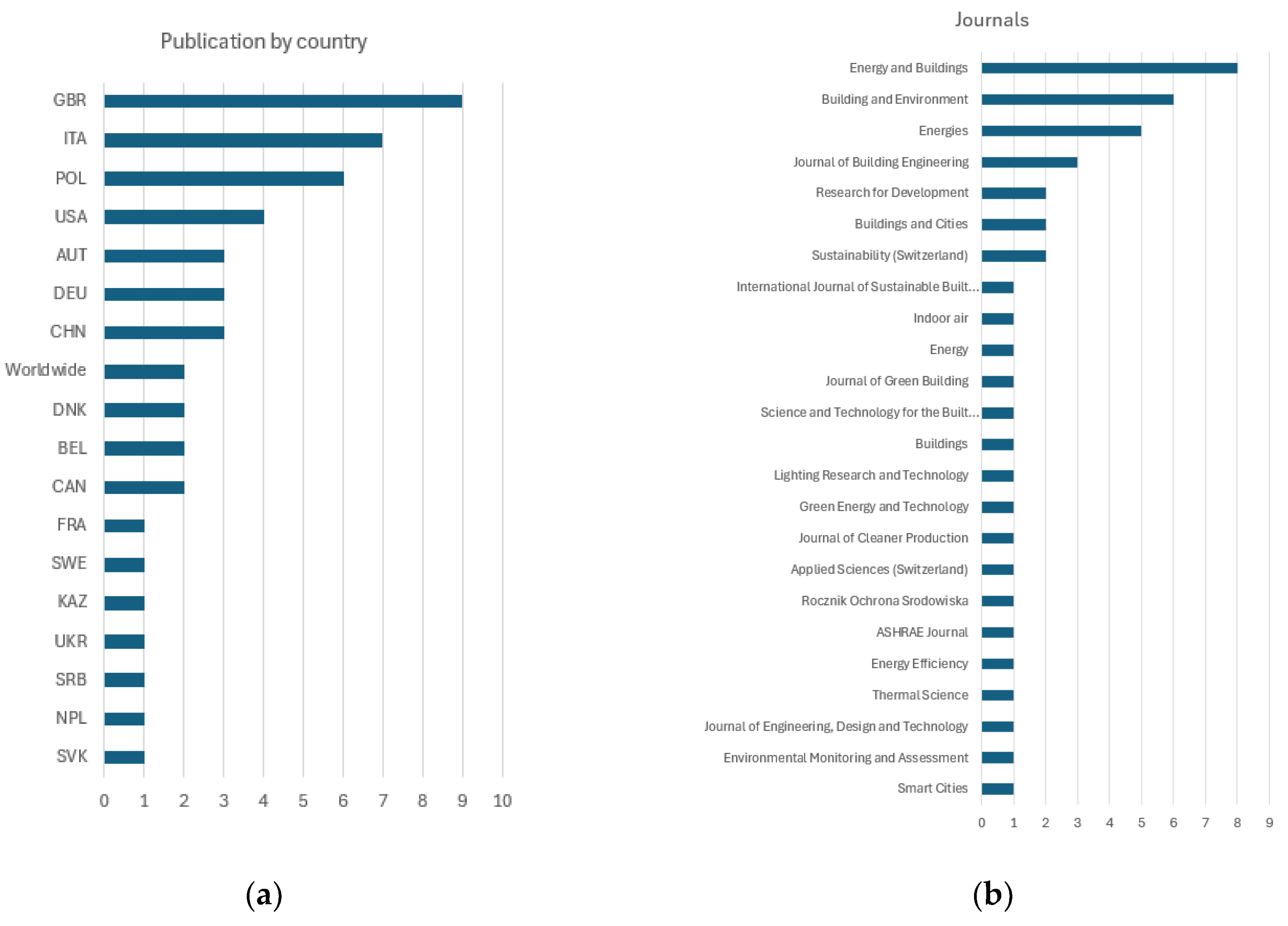

3.3. Publication Analysis

4. Results – Methods and Strategies for Intervention in Buildings

4.1. Building Envelope Refurbishment

| Building Element | Solution | Assessment Type - Refs | ||

| Calculated | Calculated, Measured | Measured | ||

| Walls | Mineral wool (15–25 cm) | [10,15,20,28,33,41,43,45,46,52,58] | [21,27,30,34,35,36,37,39,47] | [40] |

| Styrofoam (12–20 cm) | [11,22,48] | [37,53,54,55] | ||

| PIR insulation panels (10–15 cm) | [34] | [40] | ||

| Roof | Polyurethane (PUR) foam (20–30 cm) | [15,28,33,41,43,45,46,52,58] | [30,39,47,54] | |

| Mineral wool (15–25 cm) | [10,22,48] | [21,53,55] | ||

| Ground floor and foundation | XPS panels (10–15 cm) | [15,46,48] | [30,36,47,55] | |

| Thermal bridges | Elimination of thermal bridges | [28] | [30,35,36] | |

4.2. Improving a Building’s Airtightness

4.3. Window and Door Refurbishment

| Solution | Assessment Type - Refs | ||

| Calculated | Calculated, Measured | Measured | |

| Triple-glazed windows with krypton/argon (U = 0.8–1.2 W/m²K) | [22,26,41,43,45,46,52] | [35,36,37,39,47,54,55] | [40] |

| Low-E windows with reflective coating | [26,52] | [36,47,55] | |

| Anti-draught doors, thermally and acoustically sealed | [46] | [47] | |

4.4. Retrofitting of HVAC Systems (Heating, Ventilation, Air Conditioning)

4.4.1. Heating and Cooling Retrofits

| Solution | Assessment Type - Refs | ||

| Calculated | Calculated, Measured | Measured | |

| Air-to-air, air-to-water heat pumps (COP = 3.5–4.2) | [10,11,15,16,22,28,38,41,45,48,58] | [27,35,55] | [40] |

| Ground source heat pumps with horizontal or vertical collectors | [37,56] | [32] | |

| Condensing boilers, gas-powered (98% efficiency) | [48,52,57] | [27,36,37,56] | [40] |

| Biomass boilers with heat storage (3000–5000 l buffers) | [30] | ||

| Low-temperature surface heating and cooling | [15] | [34] | |

| Smart temperature controllers in every room | [28,38,41,43,46,48,58] | [25,30,34,36,37,42,50,53] | [32] |

4.4.2. Ventilation

| Ventilation Type | Solution | Assessment Type - Refs | ||

| Calculated | Calculated, Measured | Measured | ||

| Mechanical | Installation of heat recovery systems (70–90% recovery) | [11,14,20,28,33,43,45,46,52,58] | [12,27,35,36,44,47,49,50,53,54] | [18,32] |

| Introduction of HEPA and carbon filters to improve air quality | [46] | [49] | ||

| Dynamic airflow management depending on the number of people | [14,46,48] | [25,49,50] | [32] | |

| CO₂, humidity, VOC sensors for automatic ventilation adjustment | [14,16,20,26,46] | [12,25,34,36,47,49,50,54] | [32] | |

| Natural | Optimisation of window placement and opening – determining the most effective ventilation patterns for classrooms | [20] | [13,21,44] | |

| Application of seasonal ventilation strategies – different ventilation strategies in summer and winter | [24] | [13,44] | ||

| Designing windows for natural ventilation (larger ventilation openings, opening top and bottom leaves) | [21] | |||

| Use of underground ventilation ducts with constant flow temperature | [24] | [12] | ||

| CO₂ monitoring in naturally ventilated classrooms | [24] | [44] | ||

| Hybrid | Automatic window control – opening and closing windows in response to CO₂ concentration and temperature | [20] | [12,13,27] | [18] |

| Integration of mechanical ventilation with natural ventilation | [13,27] | |||

4.5. Installation of Building Energy Management Systems (BEMS)

| Solution | Assessment Type - Refs | ||

| Calculated | Calculated, Measured | Measured | |

| Central control of HVAC, heating and lighting | [11,28,31,43,46,48] | [30,34,35,37,47,50,54,55] | [32] |

| Remote monitoring of energy consumption and real-time data analysis | [11,19,28,52] | [35,50,56] | [18,32] |

| Automatic adjustment of energy consumption to the number of users | [31,43] | ||

| Integration of smart algorithms to optimise energy consumption | [20,31] | [30,55] | |

4.6. Lighting Retrofit

| Solution | Assessment Type - Refs | ||

| Calculated | Calculated, Measured | Measured | |

| Replacement of fluorescent lamps with LEDs with variable colour temperature (2700K–5000 K) | [16,19,22,31,45,52] | [23,39,42,50] | [32] |

| Installation of occupancy and daylight sensors | [16,19,31,45,52] | [39,50,54] | [32] |

| Lighting control tailored to pupils’ diurnal rhythm and required intensity | [16,19,43,48] | [23] | [32] |

| Analysis of the effect of lighting on pupils’ concentration (cortisol tests) | [42] | ||

4.7. Installation of Renewable Energy Source-Based Systems (RES)

4.8. Passive Cooling and Overheating Reduction Strategies

| Solution | Assessment Type - Refs | ||

| Calculated | Calculated, Measured | Measured | |

| Green roofs and facades – reducing ambient temperatures by 2–3 °C | [11,26] | ||

| Roofs with a high solar reflectance index (SRI) to reduce overheating | [15] | [21] | |

| Static and automatic roller blinds and sunblinds | [15,16,26] | [23,50] | [18] |

| Optimisation of night-time ventilation – automatic window opening | [15,26] | [23] | |

4.9. Optimisation of Room Layout and Indoor Environment Quality

| Solution | Assessment Type - Refs | ||

| Calculated | Calculated, Measured | Measured | |

| Rearrangement of desks for better air circulation | [18] | ||

| Adaptation of classroom layout to teaching methods that facilitate cooperation | [47] | ||

| Improving acoustic insulation of building partitions to reduce noise in classrooms. | [47,49] | ||

4.10. Dynamic Modelling and Energy Performance Analysis

| Solution | Assessment Type - Refs | ||

| Calculated | Calculated, Measured | Measured | |

| Digital simulations in dynamic modelling programmes | [16,22,33,38] | [21,25,34] | |

| Testing of various refurbishment scenarios prior to implementation | [16,20,22,48] | [13,23,37] | [40] |

| Optimisation of refurbishment strategies to maximise savings | [16] | [34] | |

4.11. Building Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) and Carbon Footprint Assessment

| Solution | Assessment Type - Refs | ||

| Calculated | Calculated, Measured | Measured | |

| Sustainable choice of low-CO₂ materials | [10] | [40] | |

| Optimisation of the balance between operational and embedded emissions | [10] | [39] | [40] |

| Analysis of the long-term environmental impact of refurbishment | [10,22] | [39] | [40] |

4.12. Financial Strategies and Analysis of Refurbishment Costs

| Solution | Assessment Type - Refs | ||

| Calculated | Calculated, Measured | Measured | |

| Simple Payback Time analysis (SPBT) – 7 to 25 years | [38] | [25,30,37,39] | |

| Use of grants and financial support programmes | [48] | [56] | |

| Comparison of energy savings before and after a refurbishment | [25,39,44] | ||

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- Maximum use of renewable energy sources – this offers the greatest carbon footprint reduction, but is highly dependent on the location of the building and requires energy storage to be fully utilised;

- Upgrading to LED lighting – it is relatively easy to achieve savings this way and the payback time is short;

- Automation and metering – depending on the needs and available resources, it is possible to scale up this intervention, using sensors and automatic systems to regulate temperature, air flow and energy consumption. It not only optimises the performance of the systems, but most importantly ensures the comfort of all users;

- Improving energy performance through technical measures to increase the insulation and airtightness of the building – this is a key aspect to significantly reduce heat loss, but one that requires significant investment and ensuring a comfortable indoor air exchange;

- The use of heat pumps, preferably with horizontal or vertical collectors – this is the most efficient way to provide heat and cooling to a building;

- Hybrid ventilation and passive cooling – this utilises the key strengths of natural and mechanical ventilation with heat recovery, as well as elements to reduce the growing problem of building overheating;

- Dynamic simulations and energy audits – in order to select the best strategies before starting any construction activity, a series of tests should be carried out on a digital model using future weather conditions, taking into account LCA-related matters and the expected payback time.

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| BIM | Building Information Modeling | LCC | Life Cycle Costing |

| BEMS | Building Energy Management System | LED | Light Emitting Diode |

| BIPV | Building Integrated Photovoltaic | LEED | Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design |

| BREEAM | Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method | PBT | Payback time |

| DA | Daylight Assessment | PCM | Phase Change Material |

| HVAC | Heating Ventilation and Air-Conditioning | PVT | Photovoltaic Thermal |

| IAQ | Indoor Air Quality | RES | Renewable Energy Source |

| IEQ | Indoor Environmental Quality | TC | Thermal Comfort |

| IoT | Internet of Things | VIP | Vacuum Insulation Panel |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

References

- Y. Schwartz, R. Raslan, and D. Mumovic, “The life cycle carbon footprint of refurbished and new buildings – A systematic review of case studies,” 2018, Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- P. Office of the European Union L- and L. Luxembourg, “DIRECTIVE (EU) 2024/1275 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 24 April 2024 on the energy performance of buildings (recast) (Text with EEA relevance).” [Online]. Available: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/1275/oj.

- E. Kükrer and N. Eskin, “Effect of design and operational strategies on thermal comfort and productivity in a multipurpose school building,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 44, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Schnieders, W. Feist, and L. Rongen, “Passive Houses for different climate zones,” Energy Build, vol. 105, pp. 71–87, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Loli and, C. Bertolin, “Towards zero-emission refurbishment of historic buildings: A literature review,” Buildings, vol. 8, no. 2, 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. Papadakis and D. Al Katsaprakakis, “A Review of Energy Efficiency Interventions in Public Buildings,” Sep. 01, 2023, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- M. Petticrew and H. Roberts, “Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences A PRACTICAL GUIDE.

- D. E. Ighravwe and S. A. Oke, “A multi-criteria decision-making framework for selecting a suitable maintenance strategy for public buildings using sustainability criteria,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 24, p. 100753, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. C. Tagliabue, S. Maltese, F. R. Cecconi, A. L. C. Ciribini, and E. De Angelis, “BIM-based interoperable workflow for energy improvement of school buildings over the life cycle”.

- F. Grossi, H. Ge, R. Zmeureanu, and F. Baba, “Assessing the effectiveness of building retrofits in reducing GHG emissions: A Canadian school case study,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 91, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, H. Chen, and P. Yu, “Green Campus Transformation in Smart City Development: A Study on Low-Carbon and Energy-Saving Design for the Renovation of School Buildings,” Smart Cities, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 2940–2965, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Nehr, L. Baus, H. Çınar, I. Elsen, and T. Frauenrath, “Indoor environmental quality assessment in passively ventilated classrooms in Germany and estimation of ventilation energy losses,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 97, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Nowak-Dzieszko, M. Mijakowski, and J. Müller, “Simulating the Natural Seasonal Ventilation of a Classroom in Poland Based on Measurements of the CO2 Concentration,” Energies (Basel), vol. 17, no. 18, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. Kabbara, S. Jorens, O. Seuntjens, and I. Verhaert, “Simulation-based optimization method for retrofitting HVAC ductwork design,” Energy Build, vol. 307, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Dong, Y. Schwartz, I. Korolija, and D. Mumovic, “Unintended consequences of English school stock energy-efficient retrofit on cognitive performance of children under climate change,” Build Environ, vol. 249, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Karakas et al., “A Multi-Criteria decision analysis framework to determine the optimal combination of energy efficiency and indoor air quality schemes for English school classrooms,” Energy Build, vol. 295, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Vilčeková et al., “Assessment of indoor environmental quality and seasonal well-being of students in a combined historic technical school building in Slovakia,” Environ Monit Assess, vol. 195, no. 12, pp. 1–22, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Zapata-Lancaster, M. Ionas, O. Toyinbo, and T. A. Smith, “Carbon Dioxide Concentration Levels and Thermal Comfort in Primary School Classrooms: What Pupils and Teachers Do,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 15, no. 6, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. J. Dunn, A. S. Oyegoke, S. Ajayi, R. Palliyaguru, and G. Devkar, “Challenges and benefits of LED retrofit projects: a case of SALIX financed secondary school in the UK,” Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology, vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 1883–1900, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Grassie et al., “Dynamic modelling of indoor environmental conditions for future energy retrofit scenarios across the UK school building stock,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 63, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Shrestha and H. B. Rijal, “Investigation on Summer Thermal Comfort and Passive Thermal Improvements in Naturally Ventilated Nepalese School Buildings,” Energies 2023, Vol. 16, Page 1251, vol. 16, no. 3, p. 1251, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yang, Y. Lou, C. Payne, Y. Ye, and W. Zuo, “Long-term carbon intensity reduction potential of K-12 school buildings in the United States,” Energy Build, vol. 282, p. 112802, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. M. Baba, H. Ge, R. Zmeureanu, and L. (Leon) Wang, “Optimizing overheating, lighting, and heating energy performances in Canadian school for climate change adaptation: Sensitivity analysis and multi-objective optimization methodology,” Build Environ, vol. 237, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Hayashi, J. Liu, T. Lin, K. Lan, and Y. Chen, “Air Quality and Thermal Environment of Primary School Classrooms with Sustainable Structures in Northern Shaanxi, China: A Numerical Study,” Sustainability 2022, Vol. 14, Page 12039, vol. 14, no. 19, p. 12039, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Al Assaad, A. Sengupta, and H. Breesch, “Demand-controlled ventilation in educational buildings: Energy efficient but is it resilient?,” Build Environ, vol. 226, p. 109778, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Grassie, Y. Schwartz, P. Symonds, I. Korolija, A. Mavrogianni, and D. Mumovic, “Energy retrofit and passive cooling: overheating and air quality in primary schools,” Buildings and Cities, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 204–225, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Lazović, V. M. Turanjanin, B. S. Vučićević, M. P. Jovanović, and R. D. Jovanović, “INFLUENCE OF THE BUILDING ENERGY EFFICIENCY ON INDOOR AIR TEMPERATURE The Case of a Typical School Classroom in Serbia,” Thermal Science, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 3605–3618, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Godoy-Shimizu, S. M. Hong, I. Korolija, Y. Schwartz, A. Mavrogianni, and D. Mumovic, “Pathways to improving the school stock of England towards net zero,” Buildings and Cities, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 939–963, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Bastian et al., “Retrofit with Passive House components,” Energy Effic, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 1–44, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Michalak, K. Szczotka, and J. Szymiczek, “Energy effectiveness or economic profitability? A case study of thermal modernization of a school building,” Energies (Basel), vol. 14, no. 7, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Hassan and K. El-Rayes, “Optimizing the integration of renewable energy in existing buildings,” Energy Build, vol. 238, p. 110851, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Harrelson, B. Watson, B. Turner, M. Ashrae, and A. West, “School Pushes IAQ, Energy-Efficiency Boundaries,” 2021. [Online]. Available: www.ashrae.org.

- N. Buyak, V. Deshko, and I. Bilous, “Сhanging Energy and Exergy Comfort Level after School Thermomodernization,” Rocznik Ochrona Srodowiska, vol. 23, pp. 458–469, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Jradi, “Dynamic energy modelling as an alternative approach for reducing performance gaps in retrofitted schools in Denmark,” Applied Sciences (Switzerland), vol. 10, no. 21, pp. 1–17, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Dall’O’ and L. Sarto, “Energy and environmental retrofit of existing school buildings: Potentials and limits in the large-scale planning,” Research for Development, pp. 317–326, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Zyczynska, Z. Suchorab, J. Kočí, and R. Černý, “Energy effects of retrofitting the educational facilities located in south-eastern Poland,” Energies (Basel), vol. 13, no. 10, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Re Cecconi, L. C. Tagliabue, N. Moretti, E. De Angelis, A. G. Mainini, and S. Maltese, “Energy retrofit potential evaluation: The regione lombardia school building asset,” Research for Development, pp. 305–315, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ling, H. Tong, J. Xing, and Y. Zhao, “Simulation and optimization of the operation strategy of ASHP heating system: A case study in Tianjin,” Energy Build, vol. 226, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Asdrubali, I. Ballarini, V. Corrado, L. Evangelisti, G. Grazieschi, and C. Guattari, “Energy and environmental payback times for an NZEB retrofit,” Build Environ, vol. 147, pp. 461–472, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Moncaster, F. N. Rasmussen, T. Malmqvist, A. Houlihan Wiberg, and H. Birgisdottir, “Widening understanding of low embodied impact buildings: Results and recommendations from 80 multi-national quantitative and qualitative case studies,” J Clean Prod, vol. 235, pp. 378–393, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- U. Aigerim, T. Valeriya, and S. Artem, “A case study of energy modeling of a school building in Astana city (Kazakhstan),” in Green Energy and Technology, Springer Verlag, 2018, pp. 967–984. [CrossRef]

- N. Gentile, T. Goven, T. Laike, and K. Sjoberg, “A field study of fluorescent and LED classroom lighting,” Lighting Research and Technology, vol. 50, no. 4, pp. 631–650, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Österreicher, “A methodology for integrated refurbishment actions in school buildings,” Buildings, vol. 8, no. 3, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Heebøll, P. Wargocki, and J. Toftum, “Window and door opening behavior, carbon dioxide concentration, temperature, and energy use during the heating season in classrooms with different ventilation retrofits—ASHRAE RP1624,” Sci Technol Built Environ, vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 626–637, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. Salvalai, L. E. Malighetti, L. Luchini, and S. Girola, “Analysis of different energy conservation strategies on existing school buildings in a Pre-Alpine Region,” Energy Build, vol. 145, pp. 92–106, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Hu, “ASSESSMENT OF EFFECTIVE ENERGY RETROFIT STRATEGIES AND RELATED IMPACT ON INDOOR ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY A case study of an elementary school in the State of Maryland.

- P. Giordani, A. Righi, T. D. Mora, M. Frate, F. Peron, and P. Romagnoni, “Energetic and functional upgrading of school buildings,” in Mediterranean Green Buildings and Renewable Energy: Selected Papers from the World Renewable Energy Network’s Med Green Forum, Springer International Publishing, 2017, pp. 633–642. [CrossRef]

- I. García Kerdan, R. Raslan, and P. Ruyssevelt, “An exergy-based multi-objective optimisation model for energy retrofit strategies in non-domestic buildings,” Energy, vol. 117, pp. 506–522, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Verriele et al., “The MERMAID study: indoor and outdoor average pollutant concentrations in 10 low-energy school buildings in France,” Indoor Air, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 702–713, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, J. Kuckelkorn, F. Y. Zhao, D. Liu, A. Kirschbaum, and J. L. Zhang, “Evaluation on classroom thermal comfort and energy performance of passive school building by optimizing HVAC control systems,” Build Environ, vol. 89, pp. 86–106, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- X. Dequaire, “A multiple-case study of passive house retrofits of school buildings in Austria,” Nearly Zero Energy Building Refurbishment: A Multidisciplinary Approach, vol. 9781447155232, pp. 253–278, Aug. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Bull, A. Gupta, D. Mumovic, and J. Kimpian, “Life cycle cost and carbon footprint of energy efficient refurbishments to 20th century UK school buildings,” International Journal of Sustainable Built Environment, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 1–17, 2014. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Krawczyk, “Theoretical and real effect of the school’s thermal modernization - A case study,” Energy Build, vol. 81, pp. 30–37, 2014. [CrossRef]

- G. Dall’O, E. Bruni, and A. Panza, “Improvement of the sustainability of existing school buildings according to the leadership in energy and environmental design (LEED)® protocol: A case study in Italy,” Energies (Basel), vol. 6, no. 12, pp. 6487–6507, 2013. [CrossRef]

- G. Dall’O and L. Sarto, “Potential and limits to improve energy efficiency in space heating in existing school buildings in northern Italy,” Energy Build, vol. 67, pp. 298–308, Dec. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Zimny and, K. Szczotka, “ECOLOGICAL HEATING SYSTEM OF A SCHOOL BUILDING. DESIGN, IMPLEMENTATION AND OPERATION,” Environment Protection Engineering, vol. 38, no. 2, 2012. [CrossRef]

- E. Beusker, C. Stoy, and S. N. Pollalis, “Estimation model and benchmarks for heating energy consumption of schools and sport facilities in Germany,” Build Environ, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 324–335, Mar. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Sfakianaki et al., “Energy consumption variation due to different thermal comfort categorization introduced by European standard EN 15251 for new building design and major rehabilitations,” International Journal of Ventilation, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 195–204, Sep. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Zimny and, P. Michalak, “Environment Protection Engineering THE WORK OF A HEATING SYSTEM WITH RENEWABLE ENERGY SOURCES (RES) IN SCHOOL BUILDING”.

- Y. M. Idris and M. Mae, “Anti-insulation mitigation by altering the envelope layers’ configuration,” Energy Build, vol. 141, pp. 186–204, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Lis and, N. Spodyniuk, “The quality of the microclimate in educational buildings subjected to thermal modernization”. [CrossRef]

- T. GHARE, “Factors affecting Thermal Bridges and their impact on Building Energy Performance,” 2024, Accessed: Feb. 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.politesi.polimi.it/handle/10589/227957.

- Boros, C. Tanasa, V. Stoian, and D. Dan, “Thermal studies of specific envelope solutions for an energy efficient building,” in Key Engineering Materials, Trans Tech Publications Ltd, 2015, pp. 192–197. [CrossRef]

- Prignon and, G. Van Moeseke, “Factors influencing airtightness and airtightness predictive models: A literature review,” Energy Build, vol. 146, pp. 87–97, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- “Obwieszczenie Ministra Rozwoju i Technologii z dnia 15 kwietnia 2022 r. w sprawie ogłoszenia jednolitego tekstu rozporządzenia Ministra Infrastruktury w sprawie warunków technicznych, jakim powinny odpowiadać budynki i ich usytuowanie.” Accessed: Feb. 09, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20220001225.

- C. Mørck and A. J. Paulsen, “Energy saving technology screening within the EU-project ‘school of the Future,’” in Energy Procedia, Elsevier Ltd, 2014, pp. 1482–1492. [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, S. Cammarano, and V. Savio, “Daylighting for Green schools: A resource for indoor quality and energy efficiency in educational environments,” in Energy Procedia, Elsevier Ltd, Nov. 2015, pp. 3162–3167. [CrossRef]

- D. O’connor, J. K. S. Calautit, and B. R. Hughes, “A review of heat recovery technology for passive ventilation applications,” Feb. 01, 2016, Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Rabani, V. Kalantar, and M. Rabani, “Heat transfer analysis of a Trombe wall with a projecting channel design,” Energy, vol. 134, pp. 943–950, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- G. M. Revel et al., “Cost-effective technologies to control indoor air quality and comfort in energy efficient building retrofitting,” Environ Eng Manag J, vol. 14, no. 7, pp. 1487–1494, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Morck, K. E. Thomsen, and B. E. Jorgensen, “School of the future: Deep energy renovation of the Hedegaards School in Denmark,” in Energy Procedia, Elsevier Ltd, Nov. 2015, pp. 3324–3329. [CrossRef]

- S. Katsoulis, I. Christakis, and G. Koulouras, “Energy-Efficient Data Acquisition and Control System using both LoRaWAN and Wi-Fi Communication for Smart Classrooms,” 2024 13th International Conference on Modern Circuits and Systems Technologies, MOCAST 2024 - Proceedings, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Piotr Pracki and Urszula Błaszczak, The issues of interior lighting on the example of an educational building adjustment to nZEB standard. IEEE, 2016.

- S. Akrasakis and A. G. Tsikalakis, “Corridor lighting retrofit based on occupancy and daylight sensors: implementation and energy savings compared to LED lighting,” Jul. 03, 2018, Taylor and Francis Ltd. [CrossRef]

- E. Deambrogio et al., “Increase Sustainability in Buildings Through Public Procurements: The PROLITE project for Lighting Retrofit in Schools,” in Energy Procedia, Elsevier Ltd, Mar. 2017, pp. 328–337. [CrossRef]

- J. Stewart, J. M. Counsell, and A. Al Kaykhan, “Design and specification of building integrated DC electricity networks,” FTC 2016 - Proceedings of Future Technologies Conference, pp. 1237–1240, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- V Dambhare, B. Butey, and S. V Moharil, “Solar photovoltaic technology: A review of different types of solar cells and its future trends,” p. 12053, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Yousefi Pihani, M. M. Krol, and U. T. Khan, “Optimizing Green Roof Design Parameters and Their Effects on Thermal Performance Under Current and Future Climates in the City of Toronto,” Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, vol. 239, pp. 583–596, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mohelníková, M. Novotny, and P. Mocová, “Evaluation of school building energy performance and classroom indoor environment,” May 01, 2020, MDPI AG. [CrossRef]

- G. M. Di Giuda, V. Villa, and P. Piantanida, “BIM and energy efficient retrofitting in school buildings,” in Energy Procedia, Elsevier Ltd, Nov. 2015, pp. 1045–1050. [CrossRef]

- Al Bunni and, H. Shayesteh, “Refurbishment of UK school buildings: Challenges of improving energy performance using BIM,” in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Institute of Physics Publishing, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Zimmermann, K. Kanafani, F. N. Rasmussen, C. Andersen, and H. Birgisdóttir, “LCA-Framework to evaluate circular economy strategies in existing buildings,” in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, IOP Publishing Ltd, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Oorschot, “A second life for school buildings by atelier PRO architects,” in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Institute of Physics, 2022, p. 6DUMMY. [CrossRef]

- T. D. Mora, A. Righi, F. Peron, and P. Romagnoni, “Cost-Optimal measures for renovation of existing school buildings towards nZEB,” in Energy Procedia, Elsevier Ltd, 2017, pp. 288–302. [CrossRef]

- S. Ferrari and C. Romeo, “Retrofitting under protection constraints according to the nearly Zero Energy Building (nZEB) target: The case of an Italian cultural heritage’s school building.,” in Energy Procedia, Elsevier Ltd, 2017, pp. 495–505. [CrossRef]

- Baggio, C. Tinterri, T. D. Mora, A. Righi, F. Peron, and P. Romagnoni, “Sustainability of a Historical Building Renovation Design through the Application of LEED® Rating System,” in Energy Procedia, Elsevier Ltd, 2017, pp. 382–389. [CrossRef]

- Filippi and, E. Sirombo, “Green rating of existing school facilities,” in Energy Procedia, Elsevier Ltd, Nov. 2015, pp. 3156–3161. [CrossRef]

- J. Reiss, “Energy retrofitting of school buildings to achieve plus energy and 3-litre building standards,” in Energy Procedia, Elsevier Ltd, 2014, pp. 1503–1511. [CrossRef]

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION, “COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS ‘Fit for 55’: delivering the EU’s 2030 Climate Target on the way to climate neutrality,” Brussels, 2021. Accessed: Feb. 20, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/clima/citizens/support_en.

| Refs | Location | Year | Assessment | Performance | Journals |

| [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] [22] [23] [24] [25] [26] [27] [28] [29] [30] [31] [32] [33] [34] [35] [36] [37] [38] [39] [40] [41] [42] [43] [44] [45] [46] [47] [48] [49] [50] [51] [52] [53] [54] [55] [56] [57] [58] [59] |

CAN - Montreal, Ottawa, Halifax CHN - Yezhai DEU - Würselen POL - Krakow BEL GBR GBR SVK - Košice GBR GBR GBR NPL - Kathmandu USA CAN - Montreal CHN - Yulin Ghent GBR SRB - Zaječar GBR AUT - Innsbruck POL - Trębowiec USA - Urbana USA - Arlington UKR - Kyiv DNK - Odense ITA - Lombardy POL ITA - Lombardy CHN - Tianjin ITA - Turin Worldwide KAZ SWE - Helsingborg AUT - Vienna DNK - Kopenhaga ITA - Lecco USA - Maryland ITA - Castelfranco Veneto GBR FRA - Alsace DEU - Munich AUT GBR - London POL - Białystok ITA - Lombardy ITA - Lombardy POL - Wielka Wieś DEU - Stuttgart Worldwide POL - Gródek nad Dunajcem |

2024 2024 2024 2024 2024 2024 2023 2023 2023 2023 2023 2023 2023 2023 2022 2022 2022 2022 2022 2022 2021 2021 2021 2021 2020 2020 2020 2020 2020 2019 2019 2018 2018 2018 2018 2017 2017 2017 2016 2016 2015 2014 2014 2014 2013 2013 2012 2012 2011 2008 |

Calculated Calculated Calculated, Measured Calculated, Measured Calculated Calculated Calculated Measured Measured Calculated Calculated Calculated, Measured Calculated Calculated, Measured Calculated Calculated, Measured Calculated Calculated, Measured Calculated Measured Calculated, Measured Calculated Measured Calculated Calculated, Measured Calculated, Measured Calculated, Measured Calculated, Measured Calculated Calculated, Measured Measured Calculated Calculated, Measured Calculated Calculated, Measured Calculated Calculated Calculated, Measured Calculated Calculated, Measured Calculated, Measured Calculated, Measured Calculated Calculated, Measured Calculated, Measured Calculated, Measured Calculated, Measured Calculated Calculated Calculated, Measured |

Energy, LCA Energy Energy, IAQ IAQ LCC IEQ IEQ IAQ IAQ, TC Energy, LCC IAQ, TC TC Energy, LCA Energy, TC IAQ, TC IAQ, TC IEQ TC Energy Energy, TC Energy Energy Energy, IAQ TC Energy Energy Energy Energy, LCA, TC Energy Energy, LCA LCA Energy, DA, TC Energy, DA Energy Energy, TC Energy, LCC Energy, TC Energy Energy IAQ Energy, TC Energy Energy, LCA Energy Energy, IEQ Energy, IEQ Energy Energy Energy, TC Energy |

Journal of Building Engineering Smart Cities Journal of Building Engineering Energies Energy and Buildings Building and Environment Energy and Buildings Environmental Monitoring and Assessment Sustainability (Switzerland) Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology Journal of Building Engineering Energies Energy and Buildings Building and Environment Sustainability (Switzerland) Building and Environment Buildings and Cities Thermal Science Buildings and Cities Energy Efficiency Energies Energy and Buildings ASHRAE Journal Rocznik Ochrona Środowiska Applied Sciences (Switzerland) Book chapter Energies Book chapter Energy and Buildings Building and Environment Journal of Cleaner Production Book chapter Lighting Research and Technology Buildings Science and Technology for the Built Environment Energy and Buildings Journal of Green Building Book chapter Energy Indoor air Building and Environment Book chapter International Journal of Sustainable Built Environment Energy and Buildings Energies Energy and Buildings Environment Protection Engineering Building and Environment International Journal of Ventilation Environment Protection Engineering |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).