1. Introduction

Institutional and stakeholder theories are essential considering the efforts of organizations to moderate the effects of their activities on the society. Institutional theory proposes that improving environmental performance requires adopting practices shaped by social, environmental, and organizational factors [

1,

2]. The growing importance on EE pinpoints the adverse effects of organizational activities, encouraging moral behavior and boosting perceived environmental performance (PEP) as an ethical issue [

3]. Frighteningly, over six million people die yearly from air pollution, with more than one million deaths linked to harmful chemicals [

4]. The United States, known as one of the top ten nations with pollution-related deaths, sees the EPA urging organizations to account for toxic chemical releases and pollution prevention efforts to enhance PEP [

5].

Furthermore, Helliwell

et al. (2020) highlight the importance of environmental ethics for organizational success. Meanwhile, firms are restructuring to enhance accountability and environmental performance, but existing models fail to address personal adoption [

7]. The spurring of this study is as a result of increasing significance of organizational commitment and environmental ethics in attaining sustainable performance is what this study. This study builds on the findings of Tsinopoulos et al. (2018) by proposing that stakeholder pressure and organizational environmental awareness, both of which may be impacted by environmental, which in returns influence how environmental performance is viewed. Additionally, Trizotto et al. (2024) point out that innovation climate awareness is a significant moderating element in the relationship between environmental ethics and perceived environmental performance. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to shed light on how these components interact to improve organizational performance and sustainability.

The following are some ways that this study contributes to the existing literature regarding both institutional and stakeholders’ theory: First, this study highlights the indirect pathways through which EA and SP influence PEP by means of LC and EE. Secondly, this study focuses on Nigeria's manufacturing industry, which has received little attention in the field of environmental studies. Third, in revealing the innovative climate's negligible function within this framework, which may be ascribed to a number of organizational and environmental contingencies. First, it is possible that in some settings, particularly in developing economies like Nigeria, innovation climate is not sufficiently developed or prioritized in organizational culture. This could be due to a variety of factors, including limited resources, less emphasis on cutting-edge technology, and a lack of strong institutional support for fostering an innovation-driven environment [

8].

More so, in such environments, firms may be more focused on meeting immediate operational needs rather than fostering an atmosphere conducive to innovation, which could weaken the moderating effect of IC on the relationship between EE and PEP. Third, the study challenges some existing assumptions and offers new perspectives on the factors that truly drive environmental performance in manufacturing industries. The study challenges some existing assumptions in the literature and offers new perspectives on the factors that genuinely influence environmental performance in manufacturing industries. By highlighting the limited role of innovation climate in this context, it encourages a reevaluation of how environmental performance is driven by organizational factors, particularly in developing economies where innovation may not be as deeply ingrained in business practices.

The succeeding sections are organized as follows: Section II thoroughly assesses pertinent literature. Section III provides a thorough description of the research methodology and data sources. Section IV provides the empirical findings and analysis, while Section V summarizes the study's outcome and offers policy implications and recommendations.

2. Literature Review

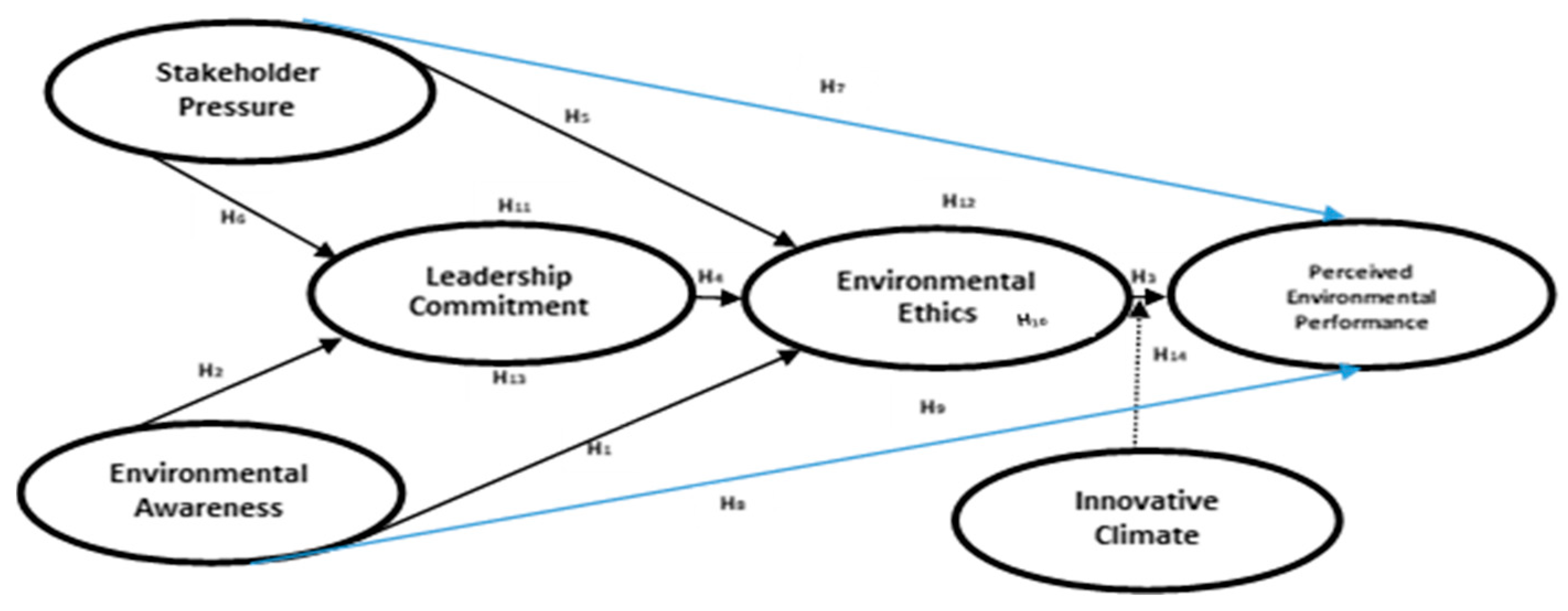

In the research framework as shown in

Figure 1, stakeholder pressure (SP) and environmental awareness (EA) influence leadership commitment (LC), and together, these three variables impact environmental ethics (EE) as well as perceived environmental performance (PEP) of an organization, with innovative climate (IC) moderating EE on PEP by using stakeholder and institutional theories to understand how firms adopt environmentally friendly practices [

3].

2.1. Theoretical Framework

Institutional theory illustrates how organizational norms, expectations of the public, and regulatory necessities influence the commitment of the leadership to environmental activities [

9,

10]. Freeman (2010) affirms that organizations should take stakeholder interest into account in addition to their desires when environmental ethics are in line with personal principles which could surge employee happiness as well as engagement.

2.2. Stakeholder Pressure (SP)

Stakeholder theory claims that organizations must satisfy the demands of all parties interested in the success of a business including the sustainable practices used to meet the expectations of various stakeholders and maintain competitiveness [

12]. Therefore, stakeholder pressure can be defined as the impact that different stakeholders have on an organization to adopt particular practices or behaviors [

13]. Businesses are frequently compelled by stakeholder pressure to address regional environmental concerns [

14].

2.3. Environmental Awareness (EA)

EA can be defined as the awareness of a range of environmental challenges, including pollution, resource depletion, and climate change, as well as being dedicated to implementing actions and policies that lessen these problems [

15]. Kohler

et al. (2022) use meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy of environmental programs. But drawing on UNESCO's 2022 report, Zancajo

et al. (2021) emphasize the significance of media and education in raising global EA.

2.4. Leadership Commitment (LC)

Leadership commitment to environmental ethics refers to the dedication of organizational leaders to integrate environmental considerations into their strategic decisions, policies, and practices. It entails actively promoting sustainability and moral environmental behavior within the company, going beyond simple adherence to environmental laws (Muttakin and Khan, 2023). Aguinis

et al., (2024) investigate how this commitment influences corporate culture and improves CSR outcomes. According to research, a culture of responsibility and better perceived environmental performance are facilitated by leadership commitment [

18,

19].

2.5. Environmental Ethics (EE)

EE can be described as the study of how human activity affects the environment and what defines moral behavior toward it [

20]. It is the study of moral relationships between humans and the natural world. Ferris and Fineman (2024) broaden the scope of ethical considerations by including ecosystems and animals. Robinson

et al. (2022) include environmental, social, and economic factors into a paradigm for moral sustainability while Schroeder (2023) promotes an ecocentric viewpoint that puts inherent of nature worth ahead of human-centric viewpoints. More so, individual duties in minimizing environmental hazards are evaluated by Keller

et al. (2023). Thompson (2020) investigates how environmental ethics might be incorporated into the creation of policies. In his analysis of environmental justice, Pellow (2023) focuses on how underprivileged populations are exposed to pollution and how resources are distributed. Above all, these authors highlight how crucial it is to include moral values into sustainable activities in order to create a better future.

2.6. Perceived Environmental Performance (PEP)

PEP is the subjective evaluation of a business's sustainability and environmental effect by internal and external stakeholders [

26]. Delmas and Burbano (2011) examine the detrimental impacts of greenwashing and how it skews stakeholders' perceptions of environmental performance. Their research highlights how stakeholder perceptions have a big influence on business reputation and behavior highlighting how crucial it is to match perceived and actual environmental performance in order to preserve trust and reputation.

2.7. Innovative Climate (IC)

According to Poveda-Pareja et al. (2024), IC is one that encourages innovation, experimentation, and fresh concepts, especially in relation to environmental sustainability. According to research by Erkmen et al. (2020) IC plays a part in improving environmental performance by fostering leadership commitment and moral behavior, which leads to sustainable results. To tackle difficult problems, this environment encourages critical problem-solving and creative thinking.

2.8. Emipirical Literature Review

Liu et al. (2019) and Ak and Kutlu (2017) found out in their study that environmental ethics are positively impacted by more environmental awareness in a range of cultural contexts. In Zibo, China, Wang et al. (2016) looked at 972 participants from both urban and rural locations. They found a high correlation between leadership commitment and environmental consciousness. Wu et al. (2024) confirmed this in the production of medical equipment. More so, Singh et al., (2019) studied 364 managers in the UAE, using SEM to show that environmental ethics positively influences perceived environmental performance. Xie et al. (2024) confirmed this relationship in Chinese manufacturing firms. Also, Mishra and Tikoria (2021) studied 537 doctors in Rajasthan, India, using SEM, finding leadership commitment positively impacts environmental ethics. Zhang and Zhang (2016) confirmed this in 502 insurance agents in China leading to the following hypotheses:

H1: EA positively influence organizational EE.

H2: EA positively influence LC as regards environmental sensitivity.

H3: EE positively influence PEP.

H4: LC positively influence EE.

Furthermore, Rui & Lu (2021) studied 278 enterprises in the Yangtze River Delta, using regression analysis, revealing stakeholder pressure significantly influences environmental ethics. D’Souza et al. (2022) confirmed this in 286 social businesses in Bangladesh. Tian et al. (2015) conducted two studies in China, finding a positive relationship between stakeholder pressure and leadership commitment. Yong et al. (2022) confirmed this in 112 Malaysian manufacturing firms using PLS modeling. Alt et al. (2015) examined 170 firms across Europe, finding stakeholder pressure positively influences perceived environmental performance. Graham (2020) confirmed this in 149 U.K. food industry companies, using hierarchical regression analysis. Xie et al. (2024) evaluated 410 managers in China and discovered that environmental awareness positively influences perceived environmental performance. Alzghoul et al. (2023) confirmed this by using 287 individuals in Jordanian pharmaceutical companies which led to the following hypotheses:

H5: SP has significant positive influence on EE.

H6: SP has significant positive influence on LC.

H7: SP has significant positive influence on PEP.

H8: EA has significant positive influence on PEP.

In addition, Saifulina et al. (2022) studied 331 bank employees across Kazakhstan, Ecuador, and China, finding EE mediates the relationship between EA and PEP. De Araujo (2014) similarly highlighted this mediating role. Also, Zailani et al., (2014) considered 252 Malaysian transportation companies, using SEM to examine EE as a mediator between LC and PEP, highlighting its significant influence on environmental performance. In the meantime, Mansour et al., (2022) discovered that the relationship between EE and SP is mediated by LC, highlighting the fact that LC guarantees that external pressures result in moral environmental behavior. Using stepwise regression, Rui and Lu (2021) examined 278 businesses in the Yangtze River Delta and discovered that Stakeholder Pressure affects Environmental Ethics, which in turn improves PEP. Furthermore, LC is identified by Wu et al. (2024) and Wang (2019) as a critical mediator that converts EA into effective EE. LC integrate sustainability into organizational culture and strategies, which leads to the development of the following hypotheses:

H9: EE mediate the relationship between EA and PEP.

H10: LC mediate the relationship between SP and EE.

H11: EE mediate the relationship between LC and PEP.

H12: EE mediate the relationship between SP and PEP.

H13: LC mediate the relationship between EA and organizational EE.

Finally, khtar et al. (2024) and Enbaia et al. (2024) claim that an innovative climate, characterized by a culture fostering creativity and the adoption of new technologies, enhances the effect of environmental ethics on perceived environmental performance.This led to the following hypothesis.

H14: IC moderates the effects of organizational EE on PEP.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

This study employs a total population sampling technique by using structured questionnaires to collect quantitative data from 421 manufacturing companies in Lagos State, Nigeria. The participants of the study comprise managers of those manufacturing companies in Lagos state. Any organization whose managers declined to complete the questionnaire for any reason was excluded from the study. The responses gathered from the questionnaires were collated and analyzed using SPSS version 26 and SmartPLS 4.

There are 421 manufacturing companies in Lagos State, Nigeria

1. This study focused on the entire population of manufacturing companies in Lagos State, resulting in the distribution of 421 questionnaires. Of these, 386 were returned and deemed usable, yielding a response rate of approximately 91.7%. Participants in this study included managers from manufacturing companies in Lagos State, recognized as the Centre of Excellence.

Due to constraints such as time and cost, the study employed non-probability sampling techniques, specifically convenience sampling, for data collection. Non-probability sampling can effectively estimate population characteristics [

44]. This research utilized a quantitative approach, employing structured questionnaires as the primary data collection instrument. The study design aims to objectively examine the formulated hypotheses that elucidate the relationships among the study variables, while also generalizing the findings to a larger population [

45].

3.2. Items of Measurements

This study utilizes six constructs, each measured by a different number of items, referred to as indicators. These items were designed using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 to 5, where "1" represents "strongly disagree" and "5" signifies "strongly agree," as detailed in Appendix 1.

Lee et al., (2018) created four measures (SP1 to SP4) to measure stakeholder pressure. Five items were also used to evaluate environmental awareness (EA1 to EA5) created by Gadenne et al. (2009) with five items used to measure perceived environmental performance (PEP1 to PEP5) adopted from Paillé et al., (2014). Specifically, five items were used to measure environmental ethics (EE1 to EE5), developed by Rui and Lu (2021). Leadership commitment was assessed with three items (LC1 to LC3) created by Banerjee et al. (2003). And, four items (IC1 to IC4) developed by Popa et al. (2017) were used to measure innovative climate.

4. Results

Measurement models and structural equation modeling, were examined using SmartPLS 4 alongside with data cleaning and descriptive analysis using SPSS version 26 to examine the developed hypotheses.

4.1. Demographic Study

The demographic composition of this is based on 386 participants out of 421 questionnaires distributed to the target population which were found valid, yielding a 91.69% rate of return.

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the managers who participated in the survey, representing their respective organizations. The findings indicate that a majority of participants were female, comprising 54.65% of the sample. Additionally, most respondents fell within the age bracket of 25 to 40 years, accounting for 76.2%. The data also reveal that the majority of the companies represented were privately owned, constituting 77.7% of the sample.

Furthermore, nearly half of the managers (47.4%) reported having less than four years of tenure in their positions, and most participants identified as married, representing 53.1% of the respondents.

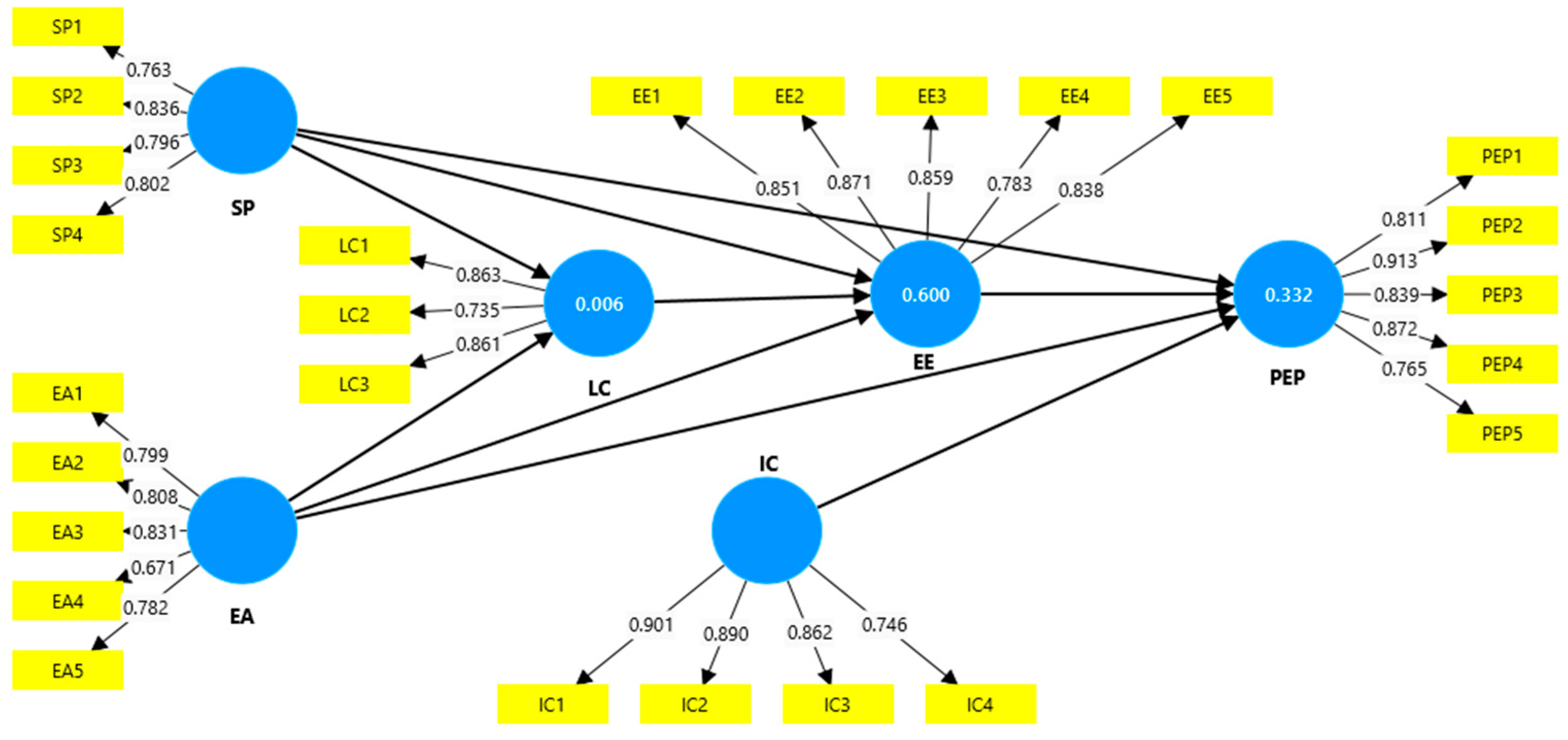

4.2. Measurement Model

The constructs of the study were examined by evaluating the measurement model (

Figure 2) to confirm the reliability and validity of the studied variables before proceeding to the structural model.

According to

Table 2, all factor loadings exceed 0.7, indicating that each indicator effectively represents its underlying construct (Vinzi et al., 2010). However, the factor loading for environmental awareness (EA4, 0.671) falls below 0.7 but remains above the minimum satisfactory threshold of 0.50 [

52]. As noted by Latif et al. (2020), many social science studies report factor loadings below 0.70, suggesting that rather than routinely deleting indicators, it is essential to assess the impact of such actions on composite reliability and convergent validity. Sarstedt et al. (2022) indicate that items with factor loadings between 0.40 and 0.70 may be eliminated only if it enhances these metrics.

In this study, removing EA4, which has an outer loading of 0.671, would likely not have significantly improved average variance extracted or composite reliability, as all other indicators already met acceptable thresholds. Consequently, no observed variables were deleted for further analysis. Additionally,

Table 2 shows the consistency of constructs, with reliability tests using Cronbach's alpha, rho_a (average inter-item correlation), and composite reliability (rho_c) all exceeding the acceptable threshold of 0.70 [

54].

To further ensure robust analysis, multicollinearity among variables was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF). As shown in

Table 2, all VIF values are below 5, indicating no multicollinearity issues (Jr et al., 2018). Furthermore,

Table 3 reveals that the Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio of correlations is below the acceptable threshold of 0.85 [

56] and below 0.90, thus confirming the establishment of discriminant validity.

The square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) was assessed against the correlations among the constructs using the Fornell-Larcker criterion, as presented in

Table 4. The results indicate that the square root of AVE for each construct is higher than its correlations with other constructs, whether examined vertically or horizontally in the table. This confirms that the constructs in this study exhibit discriminant validity, indicating that each construct is distinct and there is no overlap among them.

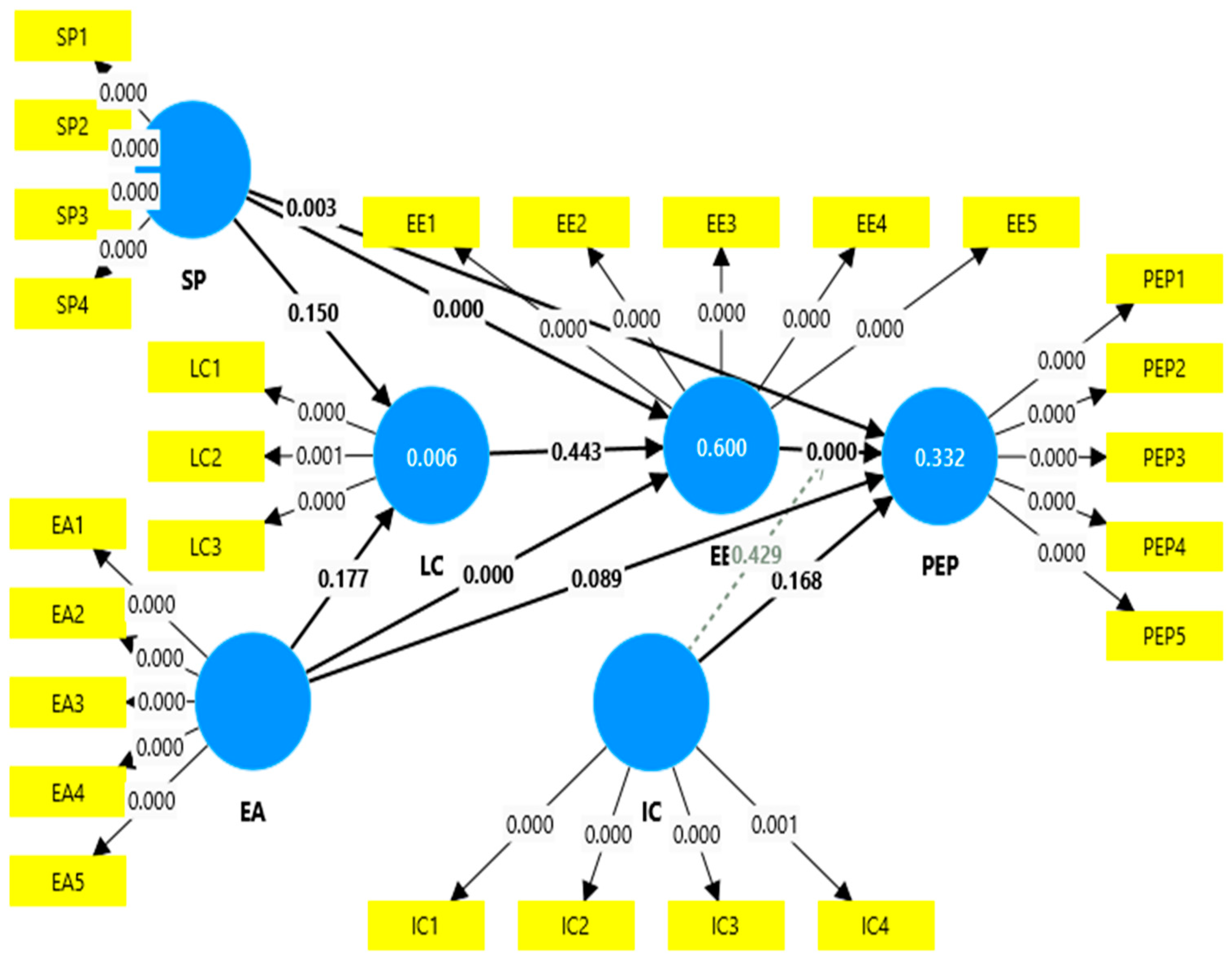

4.3. Structural Model

The hypothesized paths in the theoretical model are illustrated using a structural model, as shown in

Figure 2. To assess this model, three key conditions will be evaluated: path significance, R

2, and Q

2.

Table 5 demonstrates that all R

2 values exceed this threshold, indicating predictions, except for leadership commitment (LC), which is below 0.1. This indicates that the two independent variables SP and EA do not significantly predict LC. Conversely, the R

2 for EE is 0.600, meaning 60% of the variance in EE is explained by SP and EA. For PEP, the R

2 is 0.332, indicating that 33.2% of the variance in PEP is explained by EE and SP, with their p-values being less than 0.05, as shown in

Figure 3.

Furthermore, Q

2 establishes the predictive relevance of the dependent variables.

Table 5 shows that Q

2 values are above 0 for most variables, indicating predictive significance, except for leadership commitment (LC), which is below 0. Environmental ethics EE has a Q

2 of 0.598, and perceived environmental performance (PEP) has a Q

2 of 0.265, both demonstrating predictive relevance. Assessing the model's goodness of fit also leads to examining the proposed hypotheses to confirm relationship relevance.

Hypothesis 1 (H

1) examines whether environmental awareness (EA) positively influences organizational environmental ethics (EE).

Table 5 indicates that EA does have a positive effect on EE, with a beta weight of 0.49, exceeding the 0.10 threshold, indicating predictive ability [

57]. The t-statistic of 11.204 is greater than 1.645, confirming significance in this one-tailed test, and the p-value is 0.000, which is less than 0.05 [

58]. Thus, H

1 is supported.

Similarly, the results show that EE positively influences perceived environmental performance (PEP), with β = 0.543, t = 14.586, and p = 0.003 < 0.05, supporting H3. Additionally, EE is moderately influenced by stakeholder pressure (SP), as indicated by β = 0.371, t = 9.396, and p = 0.000 < 0.05, thus supporting H5. Furthermore, SP has a weak positive influence on PEP (β = 0.185, t = 2.784, p = 0.000 < 0.05), supporting H7.

Conversely, the study reveals that EA does not positively influence leadership commitment (LC), as shown by β = 0.093, t = 0.903, and p = 0.176, which is greater than 0.05, indicating that H2 is not supported. Similarly, LC does not influence EE, with β = 0.004, t = 0.126, and p = 0.450, leading to the conclusion that H4 is not supported. Additionally, LC is not influenced by SP, with p = 0.147 > 0.05, meaning H6 is also unsupported. Lastly, hypothesis eight (H8), stating that EA has a significant positive influence on PEP, is not supported either (β = 0.107, t = 1.281, p = 0.100 > 0.05).

4.4. Mediation Analysis

To examine the mediating roles of environmental ethics (EE) and leadership commitment (LC), a mediation analysis was conducted.

Table 6 shows that EE mediates the relationship between environmental awareness (EA) and perceived environmental performance (PEP) (H

9: β = 0.159, t = 4.631, p = 0.000). Since EA does not directly influence PEP (as shown in

Table 4.5), EE has a full mediation effect on this relationship, thus supporting H

9.

Additionally, EE also mediates the relationship between sustainability practices (SP) and PEP (H12: β = 0.130, t = 4.702, p = 0.000). Since SP directly influences PEP, EE demonstrates a partial mediation effect, supporting H12.

Conversely, LC does not mediate the relationship between SP and EE (H10: β = 0.000, t = 0.106, p = 0.458), indicating that H10 is not supported. Similarly, LC does not mediate the relationship between EA and EE (H13: β = 0.000, t = 0.104, p = 0.459), so H13 is also unsupported. Lastly, EE does not mediate the relationship between LC and PEP (H11: β = 0.002, t = 0.142, p = 0.444), meaning H11 is not supported either.

4.5. Moderation Analysis

Table 7 indicates that the variable environmental ethics (EE) is not moderated by innovative climate (IC) in its relationship with perceived environmental performance (PEP). This conclusion is based on the p-value of 0.429, which exceeds the threshold of 0.05, and the path coefficient, which is less than 0.1. Additionally, the t-statistic is below 1.645. Consequently, hypothesis H

14 is not supported.

5. Discussion

The results of this study indicate that environmental ethics (EE) and stakeholder pressure (SP) significantly influence perceived environmental performance (PEP), thereby supporting hypotheses three and seven (H3 and H7). This aligns with the findings of Xie et al. (2024), who reported that both EE and SP positively impact green product and process innovation, which in turn affects PEP. Conversely, environmental awareness (EA) did not influence PEP, contradicting the claims made by the authors.

While EE enhances PEP, the moderating effect of innovation climate (IC) was not significant, failing to support hypothesis fourteen (H

14). In comparison, [

29] proposed that IC lessens the effect of EE on PEP which is otherwise in the case of this study where IC does not moderate the impact of EE on PEP. Additionally, the study discovered that EA and SP both predict EE, hence confirming hypotheses 1 and 5 (H

1 and H

5). This supports the claims made by [

42] and [

59] that SP and EA have a good impact on organizational EE. The rejection of hypothesis four (H

4) and a difference from resulted from the fact that leadership commitment (LC) had no effect on EE.

Additionally, the study found that neither EA nor SP affected LC, which does not support hypotheses two and six (H2 and H6), contradicting Su et al. (2021) and Brown & Treviño, (2006). Furthermore, EE was found to mediate the relationships between both EA and PEP, and SP and PEP, supporting hypotheses nine and twelve (H9 and H12). This is in line with Gadenne et al. (2009) and Rui & Lu (2021). However, LC did not mediate the relationships between SP and EE, or EA and EE, rejecting hypotheses ten and thirteen (H10 and H13). Finally, the study indicated that EE does not mediate the relationship between LC and PEP, failing to support hypothesis eleven (H11) in the context of manufacturing companies in Lagos State, Nigeria.

6. Conclusions

The conclusions drawn from this study have implications for both practitioners and academics. The findings indicate that EA predicts EE but does not predict LC. Additionally, PEP is predicted by EE and SP, while EA does not have a predictive effect on PEP. It is noteworthy that LC does not predict EE, and SP does not predict LC; however, SP does predict EE. The study further establishes that EE mediates the relationship between EA and PEP, as well as the influence of SP on PEP, but does not mediate the relationship between LC and PEP. Moreover, LC does not mediate the relationship between SP and EE, nor between EA and EE. The results also indicate that innovative climate (IC) does not moderate the influence of EE on PEP.

Empirically, previous research in the field of environmental ethics has often proposed a link between these variables but provided limited empirical support. This study contributes evidence regarding the effects of EA on EE and the influence of EE and SP on PEP. Both academics and practitioners are now increasingly aware of the potential consequences of EE.

6.1. Managerial Recommendations

As a result of this study, managers may cultivate a culture that is driven by sustainability and make environmental ethics a fundamental value that is in line with the organization's long-term objectives. Furthermore, by putting sustainability first, businesses may establish a reputation as conscientious citizens and draw in investors and customers who care about the environment and corporate social responsibility (CSR). Managers must make sure that all stakeholders understand the company's commitment to sustainability.

6.2. Practical Policy Recommendations

There should be policies that encourage cooperation across stakeholders, such as communities, suppliers, and consumers. In addition, policies that encourage sustainability in all aspects of an organization's operations should be put in place, with an emphasis on waste reduction, energy conservation, and ethical material procurement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, visualization, Oluwaleke Micheal Awonaike.; supervision, Tarik Atan.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AVE |

Average Variance Extracted |

| CSR |

Corporate Social Responsibility |

| EA |

Environmental Awareness |

| EE |

Environmental Ethics |

| EPA |

Environmental Protection Agency |

| IC |

Innovative climate |

| LC |

Leadership Commitment |

| PEP |

Perceived Environmental Performance |

| PLS-SEM |

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling |

| SP |

Stakeholder Pressure |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| UAE |

United Arab Emirates |

| UNESCO |

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| VIF |

Variance Inflation Factor |

References

- Alessa, N.; Akparep, J.Y.; Sulemana, I.; Agyemang, A.O. Does stakeholder pressure influence firms environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure? Evidence from Ghana. Cogent Bus Manag 2024, 11, 2303790. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23311975.2024.2303790. [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations: Ideas and Interests; SAGE, 2008; 281p. [Google Scholar]

- Tsinopoulos, C.; Sousa, C.M.P.; Yan, J. Process Innovation: Open Innovation and the Moderating Role of the Motivation to Achieve Legitimacy. J Prod Innov Manag 2018, 35, 27–48. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jpim.12374. [CrossRef]

- Fuller, R.; Landrigan, P.J.; Balakrishnan, K.; Bathan, G.; Bose-O’Reilly, S.; Brauer, M. , et al. Pollution and health: a progress update. Lancet Planet Health 2022, 6, e535–47. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(22)00090-0/fulltext?ref=drilledpodcast.com. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epa, U. United States environmental protection agency. Qual Assur Guid Doc-Model Qual Assur Proj Plan PM. Ambient Air 2001, 2, 12. Available online: https://extapps.dec.ny.gov/data/DecDocs/C915279/Work%20Plan.BCP.C915279.2017-11-13.RI_Work_Plan-FINAL-Appendix_B5-USEPA_Compliance_Order-September_2011.pdf.

- Helliwell, J.F.; Layard, R.; Sachs, J.; De Neve, J.E. World happiness report 2020. 2020 [cited 2024 Dec 4]. Available online: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/hw_happiness/1/.

- Elliot, S.; Webster, J. Editorial: Special issue on empirical research on information systems addressing the challenges of environmental sustainability: an imperative for urgent action. Inf Syst J 2017, 27, 367–378. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/isj.12150. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.N.; Chang, J.Y. Innovation implementation in the public sector: An integration of institutional and collective dynamics. J Appl Psychol. 2009, 94, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, R.; Meyer, R.E.; Lawrence, T.B.; Oliver, C. The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism; 2017; pp. 1–928. Available online: https://www.torrossa.com/en/resources/an/5018766.

- Ren, S.; Tang, G.; EJackson, S. Green human resource management research in emergence: A review and future directions. 2018, 35, pp. 769–803. Available online: https://idp.springer.com/authorize/casa?redirect_uri=https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10490-017-9532-1&casa_token=d03SK7QfvToAAAAA:qw-hfEBRrY_NZRBXthB0X-LczPKghJis-lpVurazkflYOZO_9uWi0mC7Pn6j6AmRg78eHGpNUboqf559uw.

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press, 2010; 294p. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, G.; Sulemana, I.; Agyemang, A.O. Examining the impact of stakeholders’ pressures on sustainability practices Management Decision; Emerald Publishing Limited, 2025; Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/MD-06-2023-1008/full/html?casa_token=d2_eraqdNpkAAAAA:x3jnU8mnvua92r1mU1l63ZvPI5uoyDmsZHsCTgHW0jioHJvJqs05PsdAYCxDWNZ81pZ0VoghRcYhu5CbYRN3oz72Sxyo11-y8Vm6ciE71bz_ZpJCW1wu[cited 2025 Feb 9].

- Haleem, F.; Farooq, S.; Cheng, Y.; Waehrens, B.V. Sustainable management practices and stakeholder pressure: A systematic literature review. 2022, 14, 1967. Available online: https://www.mdpi. 2022, 14, 1967. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/14/4/1967.

- Shahzad, M.; Qu, Y.; Ur Rehman, S.; Ding, X.; Razzaq, A. Impact of stakeholders’ pressure on green management practices of manufacturing organizations under the mediation of organizational motives. J Environ Plan Manag 2023, 66, 2171–2194. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09640568.2022.2062567. [CrossRef]

- Ojo, A.O.; Fauzi, M.A. Environmental awareness and leadership commitment as determinants of IT professionals engagement in Green IT practices for environmental performance. 2020, 294, 298–307. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352550920302918?casa_token=ruSVYXi53lkAAAAA:5ziWb8nwUAALjTypI17cGV9ICeGODi7jHWCZQcKFEh8fYtGPA_yz7afUj6eJJakHmBPeCvJU-FY. [CrossRef]

- Kohler, I.V.; Kämpfen, F.; Ciancio, A.; Mwera, J.; Mwapasa, V.; Kohler, H.P. Curtailing Covid-19 on a dollar-a-day in Malawi: Role of community leadership for shaping public health and economic responses to the pandemic. World Dev 2022, 151, 105753. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X21003685. [CrossRef]

- Zancajo, A.; Fontdevila, C.; Verger, A.; Bonal, X. Regulating public-private partnerships, governing non-state schools: an equity perspective: Background paper for UNESCO Global Education Monitoring Report; UNESCO, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Muttakin, M.B.; Khan, A. CEO tenure, board monitoring and competitive corporate culture: how do they influence integrated reporting? J Account Lit 2023. ahead-of-print. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/jal-02-2023-0030/full/html. [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Rupp, D.E.; Glavas, A. Corporate social responsibility and individual behaviour. Nat Hum Behav 2024, 8, 219–227. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-023-01802-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, R.; Engen, S.; Selvaag, S. Testing visitor management strategies to reduce human waste in a highly visited national park in Norway. Facilitating a new environmental norm for visitors to Lofotodden National Park 53. Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA); 2023. [cited 2024 Nov 21]. 1125. Available online: https://brage.nina.no/nina-xmlui/handle/11250/3108279.

- Ferris, G.; Fineman, M.A. Vulnerability and the Organisation of Academic Labour; Taylor & Francis, 2024; 165p. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, A.; Corcoran, C.; Waldo, J. New Risks in Ransomware: Supply Chain Attacks and Cryptocurrency. Sci Technol Public Policy Program Rep 2022. Available online: https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/37373233.

- Schroeder, K. The ‘Surplus’ of Siem Reap: A Comparative Study of Cambodia’s Urban Recyclers. Stud Theses 2015-Present 2023. Available online: https://research.library.fordham.edu/environ_2015/158.

- Thompson, P.B. Ethics and Environmental Risk Assessment. In Food and Agricultural Biotechnology in Ethical Perspective; Thompson, P.B., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 137–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellow, D.N. Chapter 6: Environmental justice. In 2023 [cited 2024 Nov 21]. Available online: https://www.elgaronline.com/edcollchap/book/9781800881136/book-part-9781800881136-14.xml.

- Sullivan, R.; Gouldson, A. The Governance of Corporate Responses to Climate Change: An International Comparison. Bus Strategy Environ 2017, 26, 413–425. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/bse.1925. [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Burbano, V.C. The Drivers of Greenwashing. Calif Manage Rev 2011, 54, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poveda-Pareja, E.; Marco-Lajara, B.; Úbeda-García, M.; Manresa-Marhuenda, E. Innovation as a driving force for the creation of sustainable value derived from CSR: An integrated perspective. Eur Res Manag Bus Econ 2024, 30, 100241. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2444883424000019. [CrossRef]

- Erkmen, T.; Günsel, A.; Altındağ, E. The Role of Innovative Climate in the Relationship between Sustainable IT Capability and Firm Performance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4058. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/10/4058. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Cheng, Z.; Chen, M. Effects of environmental education on environmental ethics and literacy based on virtual reality technology. Electron Libr 2019, 37, 860–877. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/EL-12-2018-0250/full/html. [CrossRef]

- Ak, O.; Kutlu, B. Comparing 2D and 3D game-based learning environments in terms of learning gains and student perceptions. Br J Educ Technol 2017, 48, 129–144. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/bjet.12346. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, M.; Yang, X.; Yuan, X. Public awareness and willingness to pay for tackling smog pollution in China: a case study. 2016, 112, 1627–1634. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652615005284?casa_token=k5j3ltIYTS8AAAAA:6_2l6vbSQuRGUXEtidaCjw3dOw9yEG7gE7JTOJB2s6wZumSz_81fMS1K31uUjidj0873QSMdXRM. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Xie, S.; Wang, S.; Zhou, A.; Abruquah, L.A.; Chen, Z. Effects of environmental awareness training and environmental commitment on firm’s green innovation performance: Empirical insights from medical equipment suppliers. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0297960. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0297960. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.K.; Chen, J.; Del Giudice, M.; El-Kassar, A.N. Environmental ethics, environmental performance, and competitive advantage: Role of environmental training. Technol Forecast Soc Change 2019, 146, 203–211. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0040162518307352. [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Abbass, K.; Li, D. Advancing eco-excellence: Integrating stakeholders’ pressures, environmental awareness, and ethics for green innovation and performance. J Environ Manage 2024, 352, 120027. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301479724000136. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, B.; Tikoria, J. Impact of ethical leadership on organizational climate and its subsequent influence on job commitment: a study in hospital context. J Manag Dev 2021, 40, 438–452. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/jmd-08-2020-0245/full/html. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhang, J. Chinese insurance agents in “bad barrels”: a multilevel analysis of the relationship between ethical leadership, ethical climate and business ethical sensitivity. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 2078. Available online: http://springerplus.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40064-016-3764-2. [CrossRef]

- Saifulina, N.; Carballo-Penela, A.; Ruzo-Sanmartín, E. Effects of personal environmental awareness and environmental concern on employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior: a mediation analysis in emerging countries. Balt J Manag 2022, 18, 1–18. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/bjm-05-2022-0195/full/html. [CrossRef]

- de Araujo, F. Do I Look Good In Green?: A Conceptual Framework Integrating Employee Green Behavior, Impression Management, and Social Norms. Amaz Organ E Sustentabilidade 2014, 3, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zailani, S.; Iranmanesh, M.; Nikbin, D.; Jumadi, H.B. Determinants and environmental outcome of green technology innovation adoption in the transportation industry in Malaysia. Asian J Technol Innov 2014, 22, 286–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M.; Aman, N.; Al-Ghazali, B.M.; Shah, S.H.A. Perceived corporate social responsibility, ethical leadership, and moral reflectiveness impact on pro-environmental behavior among employees of small and medium enterprises: A double-mediation model. Front Psychol 2022, 13. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.967859/full. [CrossRef]

- Rui, Z.; Lu, Y. Stakeholder pressure, corporate environmental ethics and green innovation. Asian J Technol Innov 2021, 29, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H. How organizational green culture influences green performance and competitive advantage: The mediating role of green innovation. J Manuf Technol Manag 2019, 30, 666–683. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/jmtm-09-2018-0314/full/html. [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K. Marketing research : an applied prientation Pearson; 2020 [cited 2024 Nov 21]. Available online: https://thuvienso.hoasen.edu.vn/handle/123456789/12586.

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Homburg, C., Klarmann, M., Vomberg, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 587–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Kim, Y.M.; Kim, Y.E. Antecedents of Adopting Corporate Environmental Responsibility and Green Practices. J Bus Ethics 2018, 148, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadenne, D.L.; Kennedy, J.; McKeiver, C. An Empirical Study of Environmental Awareness and Practices in SMEs. J Bus Ethics 2009, 84, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Chen, Y.; Boiral, O.; Jin, J. The Impact of Human Resource Management on Environmental Performance: An Employee-Level Study. J Bus Ethics 2014, 121, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.B.; Iyer, E.S.; Kashyap, R.K. Corporate Environmentalism: Antecedents and Influence of Industry Type. J Mark 2003, 67, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, S.; Soto-Acosta, P.; Martinez-Conesa, I. Antecedents, moderators, and outcomes of innovation climate and open innovation: An empirical study in SMEs. Technol Forecast Soc Change 2017, 118, 134–142. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0040162517301658. [CrossRef]

- Esposito Vinzi, V.; Chin, W.W.; Henseler, J.; Wang, H. , editors. Handbook of Partial Least Squares: Concepts, Methods and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, 2010; Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-540-32827-8.

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate data analysis. englewood cliff. N J USA. 1998, 5, 207–2019. [Google Scholar]

- Latif, K.F.; Sajjad, A.; Bashir, R.; Shaukat, M.B.; Khan, M.B.; Sahibzada, U.F. Revisiting the relationship between corporate social responsibility and organizational performance: The mediating role of team outcomes. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 2020, 27, 1630–1641. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/csr.1911. [CrossRef]

- Wasko, M.M.; Faraj, S. Why Should I Share? Examining Social Capital and Knowledge Contribution in Electronic Networks of Practice. MIS Q 2005, 29, 35–57. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25148667. [CrossRef]

- Jr, J.F.H.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; 24 May; p. 2018.

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: updated guidelines on which method to use. Int J Multivar Data Anal 2017, 1, 107–123. Available online: https://www.inderscienceonline.com/doi/abs/10.1504/IJMDA.2017.087624. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: New York, 2011; 432p. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, K.; Fatima, T.; Naveed, M. The Impact of Transformational Leadership on Nurses’ Organizational Commitment: A Multiple Mediation Model. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ 2020, 10, 262–275. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2254-9625/10/1/21. [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Lin, W.; Wu, J.; Zheng, Q.; Chen, X.; Jiang, X. Ethical Leadership and Knowledge Sharing: The Effects of Positive Reciprocity and Moral Efficacy. Sage Open 2021, 11, 21582440211021823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K. Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadersh Q 2006, 17, 595–616. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S104898430600110X. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).