1. Introduction

Amid growing global urgency to combat environmental degradation, particularly under the framework of Sustainable Development Goal 13 (Climate Action), institutional mechanisms have intensified efforts to compel industrial actors to adopt sustainable practices. While regulatory and normative pressures are often cited as drivers of CES, their effectiveness in influencing large manufacturing firms in developing economies remains inadequately understood. In Africa, developing economies contribute approximately 30-40% of total emissions from manufacturing [

1] after [

2], facing escalating environmental threats such as pollution, droughts and biodiversity loss [

3]. Global projections indicate a potential rise in average temperatures from 1.3C in 2024 to 2C in 2025 [

4], with developing economies disproportionately affected. Uganda for example, faces severe air pollution from industrial activities, with forecasts indicating temperature increases from 1.5C to 3.5C by 2080 linked to over a thousand premature deaths annually [

5,

6]. The country is currently ranked 23rd most polluted economies globally, with air quality levels surpassing World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines.

The nature and effectiveness of institutional pressures in shaping CES varies significantly across contexts. In developing economies, weak enforcement, limited resources and evolving governance structures often hinder the impact of regulatory mechanisms. While research shows that institutional pressures have a significant impact on sustainability practices [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], however debate remains on the precise nature and potency of these pressures and the firm culture that emerges in response [

13]. Moreover, firms interpret and respond to these pressures differently, shaped by internal capacities, stakeholder expectations and industry norms. This study investigates how institutional pressures (coercive, normative and mimetic) manifest and interact with organizational responses to shape sustainability outcomes in Uganda’s large manufacturing firms. The primary objective is to propose a framework that shows how institutional pressures and isomorphic dynamics shape CES in large manufacturing firms. By doing so, developing economies benefit from a generated framework, and it contributes to existing institutional theory. Unlike previous frameworks that conceptualize pressures as isolated forces, this study integrates institutional isomorphic practices as co-influencers of CES. This approach accounts for context-specific dynamics in developing economies where formal institutional structures are evolving.

1.2. Literature Review

1.2.1. Institutional Theory

Although this study adopts an inductive approach, it draws from institutional theory to frame its analysis. Institutional theory emphasizes how organizations conform to environmental expectations through coercive pressures, normative mandates and mimetic behavior. These are classified as institutional pressures and isomorphism [

14]. Firms adjust their operations based on certain form of pressures exerted on them [

14]. This theoretical foundation guided both data collection and interpretation, particularly in understanding how firms perceive and adapt to environmental pressures in developing economy context. The institutional theory offers lens to explore the alignment between institutional expectations and firm environmental sustainability behavior. DiMaggio and Powell distinguish these pressures into three; coercive pressures that come from regulatory authorities mandating firms to operate in a manner that legitimizes them; normative pressures that require firms to operate based on the rules and norms of the professional association, community or industry standards; and mimetic pressures that push firms to operate in a manner similar to other firms through imitation or benchmarking. In this study, such forces shape the way large manufacturing firms operate therefore they are mandated to operate legitimately in ensuring that their operations do not affect the environment; work within the confines of the professional associations/bodies like International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 14001:2015; International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB); Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and lastly benchmark with firms that are environmentally responsible. DiMagio and Powell add that these pressures influence certain practices that form institutional isomorphism, however they did not provide measures/dimensions for these isomorphisms. This may mandate firms to operate only under pressures that legitimize them like coercive pressures and may not be pressured by normative and mimetic pressures. This also supports Oliver’s assertions that there is a possibility of firms operating based on their willingness and ability to comply but not on the pressures being exerted on them [

15]. This explains why most studies describe how firms respond to one or two pressures [

16]. These failures to respond to all the three pressures and their isomorphic practices might be attributed to lack of a clear framework that outlines the form of pressures and isomorphic practices that shape CES. Also, failure to have a guiding framework necessitates the inability of a firm to think towards activities that may increase firm expenses affecting their profit margin. Therefore, firms are most likely to only respond to those pressures that legitimize them and maybe those that affect their market expansion like normative pressures that require ISO 14001:2015 certification. This leaves mimetic pressures redundant and also all isomorphic practices can be rendered non-applicable if not documented.

1.2.2. Corporate Environmental Sustainability

Corporate Environmental Sustainability reflects firms’ responsibility to report, disclose and comply with environmental standards aimed at conserving the environment (CSRD, 2022, ISSB, ISO 14001:2015). The EU CSRD, 2022 mandates approximately 50,000 EU and Non-EU multinational companies to incorporate audited environmental data into annual management reports, linking firm environmental impacts and risks to firm performance. While CSRD promotes transparency for various stakeholders, its design is primarily EU centric and may not align with the regulatory and operational environments of developing countries such as Uganda. The International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), which builds on frameworks like Global Reporting Initiatives (GRI) and Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), emphasizes the financial materiality of environmental issues by incorporating broader economic, environmental and social externalities into reporting. However, its effectiveness is limited by insufficient guidance in emerging issues like biodiversity, particularly in regions where enforcement remains weak. ISO 14001:2015 is globally recognized certification standard for firm’s environmental compliance. While it allows firms to define their own environmental indicators, this flexibility may result in the omission of full life-cycle and supply chain considerations. Collectively, these frameworks and standards promote CES by encouraging mandatory environmental reporting, accountability and transparency thereby reinforcing coercive and normative institutional pressures. Nevertheless, significant gaps remain, including the absence of clearly defined compliance metrics from regulators and professional bodies, limited benchmarking expectations and the widespread neglect of mimetic pressures in both policy and academic disclosure.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

The study examined how institutional pressures and isomorphism mechanisms shape CES of large manufacturing firms within a developing economy. A cross sectional research design was adopted, guided by an inductive, qualitative approaches aimed at developing a contextual framework [

17,

18]. The study population comprised 41 large manufacturing firms as listed in the Uganda Manufacturers Association Business Directory, (2024). Data saturation was achieved after conducting 24 interviews, including 22 interviews with firm-level participants from 22 different large manufacturing firms and 2 interviews with regulatory officials, aligning with established qualitative research standards [

19]. A Strategic purposive sampling technique was employed, targeting firms with professional environmental managers holding qualifications or certifications in environmental science or environmental management. This criterion was based on the assumption that such professionals possess the technical and practical expertise required to offer informed perspectives on environmental sustainability. All types of manufacturing firms were eligible for inclusion.

The interviews were conducted within a phenomenological framework, allowing the exploration of how qualified firm-level participants and regulators interpret and respond to institutional pressures in relation to environmental sustainability. Phenomenology emphasizes the lived experiences and meanings individuals attach to a phenomena [

19], making it suitable for capturing the nuanced ways in which actors perceive institutional influences. For instances, a regulatory mandate viewed as coercive by one firm may be perceived as a normative expectation by another. While grounded in institutional theory, this phenomenological approach enabled context-specific insights to emerge inductively from the participants’’ experiential narratives.

Table A1: Demographic Characteristics of Firm-level participants

A total of 22 interviews as indicated in table A1 (Appendix 1) were conducted with firm-level participants across 22 large manufacturing firms. Participants age ranged from 26 to 47 years, with a mean age of 36.8 indicating a predominance of mid-career environmental professionals. Their experience in environmental management roles ranged from 3 to 15 years, suggesting substantial practical expertise in coordinating environmental activities. Although referred to as “environmental managers” for consistency in this study, their official job titles varied by firm, including Environmental Health and Safety Manager, Corporate social responsibility coordinators, Standards and Compliance Officers and Environmental Managers. Despite title differences, all participants shared similar strategic and operational responsibilities, including regulatory compliance, environmental reporting and health and safety oversight. In terms of educational qualifications, 9 participants held a master’s degree, 11 had bachelor’s degree and 2 held postgraduate diplomas. Those without a primary degree in an environmental field possessed certifications in related disciplines. This reflects well-rounded blend of technical, social and managerial skills essential for both policy-level and operational aspects of CES. The firms represented operated in Uganda’s central, Eastern and Western region, contributing a valuable regional perspective. As typical in developing economies, these firms employed between 312 and 7500 staff, underscoring their potential environmental footprint. The firms engaged in the production of wide range of goods including food and beverages, pharmaceuticals, paints, plastics, cement, steel, textiles, paper products, oil, alcohol, energy drinks, soap, and personal care products. These product categories highlight the environmental significance of the study, given their potential impacts across the production process, product life cycle and supply chain.

Table A2: Demographic Characteristics of Regulatory Officials

In addition to the firm-level interviews, two interviews presented in table A2 (Appendix 2) were conducted with environmental regulatory officials, one from Ministry of Water and Environment (MWE) and other from National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA). Both participants held master’s degrees in environmental science and engineering with not less than 14 years work experience in the field of environmental monitoring and supervision. Their extensive professional backgrounds signified deep knowledge of institutional environmental mandates and provided credible insights into the role of regulatory enforcement in advancing environmental sustainability within Uganda’s governance framework.

2.2. Data Collection Tool

A pre-test of the interview guide were conducted to enhance the clarity, relevance and quality of the interview questions. Five experts in environmental regulation and sustainability drown from both academia and practice were consulted to provide feedback and suggest refinements [

20]. Their input was systematically captured using a matrix format, as shown in Tables 3 and 4, which correspond to the interview questions for firm-level participants and regulators, respectively. The matric categorized feedback into four groups: Questions Needing Modification (QNM), Questions to Be Maintained (NBM), Questions to Be Merged (NBMW) and Questions to Be Removed (NBR).

Table A3: Interview Questions Pre-Test Matrix Tool (Firm-level participants)

Follow-up discussions were held with the experts to review and clarify their feedback. These sessions led to several adjustments in the interview guide: in table A3 (

Appendix C), Questions 1 and 5 were modified; Questions 3, 4, 6, 7, and 8 were retained without changes; Questions 1 and 3 were merged due to overlap; Question 9 was identified as a repetition of Question 3; and no questions were removed from the guide.

Table A4: Interview questions pre-test matrix Tool (Regulatory officials)

Discussions with the experts concluded that only Questions 1 and 3 in table A4 (

Appendix D) were relevant and should be retained for regulatory officials, while all other questions were removed due to limited applicability.

2.3. Data Collection Process

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from Research and Ethics Committee of Uganda Management Institute following a rigorous review process. Introductory letters were secured from the Uganda Manufacturers Association, the Ministry of Trade, Industries and Cooperatives and the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research, and these were presented to the management of the participating manufacturing firms. Participants were appointed by the firm management based on the researcher’s description of the desired profile, specifically individuals responsible for environmental sustainability. Prior to each interview, participants were briefed on the study’s purpose and procedures. Participants were encouraged to share insights grounded in real-life experiences. Written informed consent was obtained from participants, and no interview were conducted without signed consent form. in accordance with the consent agreement and the study’s risk management plan, participant identities were kept confidential and personal or firm names were not disclosed. All participants consented to the publication of findings under strict anonymity. Permission was also obtained to audio-record the interviews for data accuracy and future reference. During the interviews, participants were addressed as “sir” or “madam” to preserve confidentiality. They retained the right to skip any question they found uncomfortable; however, none expressed discomfort during sessions. No participant received any form of compensation, financial or otherwise for their involvement. All interviews were conducted in English, as both the researcher and participants had formal English education from primary school through university. The Interviews lasted between 30 minutes and one hour. Each session was facilitated by two researchers, one conducted the interview while the other observed non-verbal cues for additional contextual interpretation.

Debriefing sessions were conducted following the transcription of each interview to ensure the accuracy and authenticity of participants’ views. Participants were given the opportunity to review their transcripts and make changes where necessary either by modifying statements or removing content they felt was inappropriate or misrepresentative of themselves or their firms. Only final, participant-approved data were used to inform the study objectives. The entire data collection process was reflexive, capturing only the views, experiences, beliefs, and knowledge of the participants. At no point were the researchers’ personal opinions or interpretations introduced into the data.

2.3. Data Analysis

Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis approach [

21]. Nvivo 15 qualitative software facilitated the thematic coding and organization of the data. Following an inductive approach, themes emerged directly from the participants’ narratives and were subsequently used to develop a conceptual framework illustrating how institutional pressures shape CES of large manufacturing firms within developing economy context. According to Braun & Clarke, thematic analysis is well-suited for identifying patterns within qualitative data through a systematic and rigorous process [

21]. The analysis followed six key phases: data familiarization, code generation, development of initial themes, refinement of the final themes, theme naming and definition, and the final report production [

21].

3. Results

This section presents the results that informed the development of the framework on how institutional pressures shape CES in large manufacturing firms in developing economy context. It discloses and analyzes the key emerging themes derived from the data. Through repeated reading and careful examination of the interview transcripts, it became evident that these firms are subject to multiple institutional pressures and corresponding isomorphic forces that influence their environmental practices. During the data familiarization phase, participants’ real-time perspectives are transcribed verbatim, examples of which are presented below;

Example I. Coercive pressure

“Regulators are the ones that give us the tone. They set the tone, tone, which you operate. So, whatever they tell you is what you do. Of course, they give you the minimum standard, but you always seek to do above and beyond so that in case you fall short, you already fall within the elements”

Example II: Normative pressure

“We are also partnering with different responsible bodies, like the ISO 2015, 9001-15 for environmental, for quality. So, this is an international organization, but it comes to regulate every year”

Example III: Mimetic Pressure

“Of course, you want to benchmark from the best industry players, so that you see for them how are they doing it.”

3.1. Generated Themes

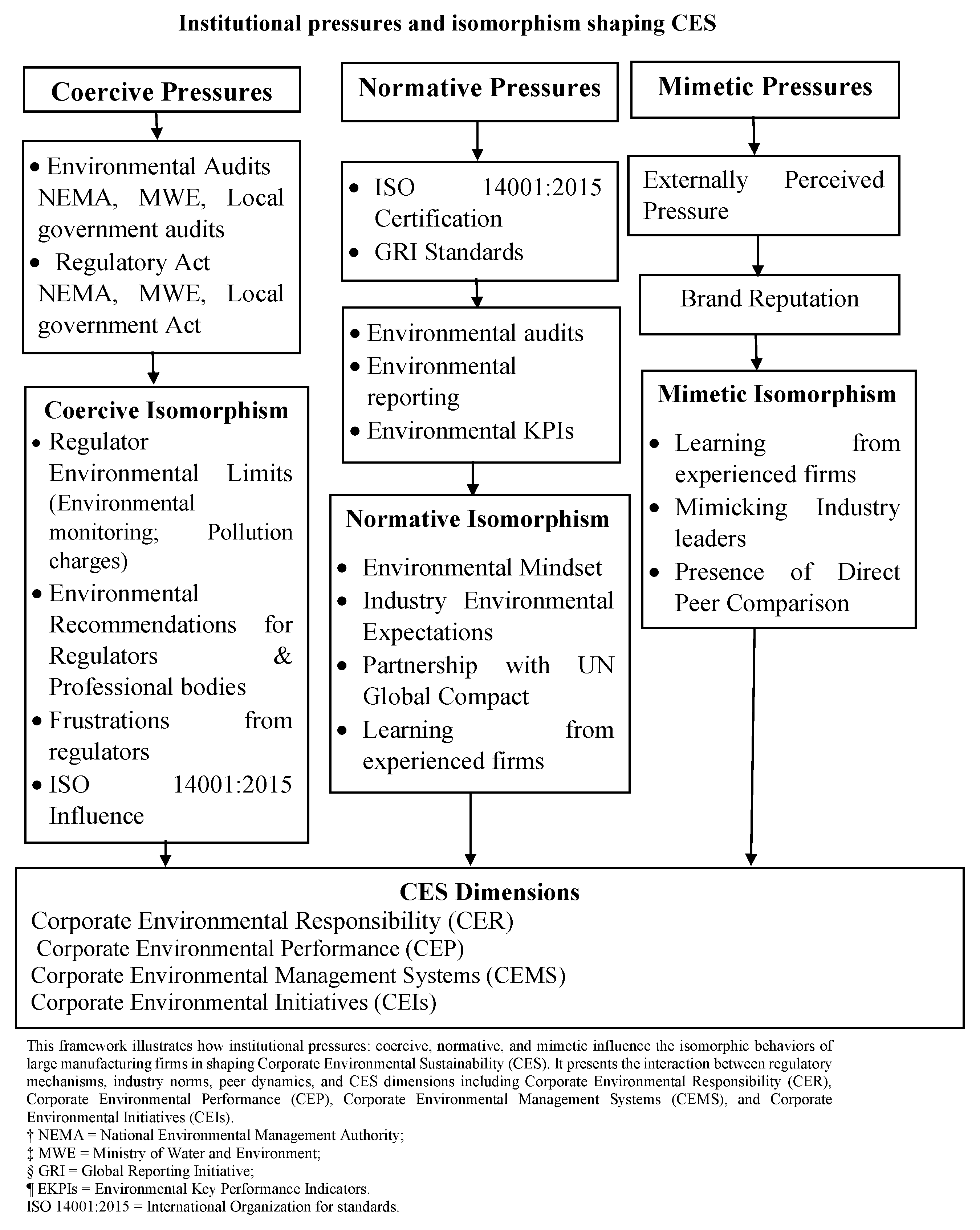

The data is grouped into six thematic groups presented in Table 5 with each theme comprising of sub-themes and representative codes. The table shows that coercive pressures arise from mandatory environmental audits (NEMA environmental audits, MWE environmental audits and local government environmental audits); regulatory laws and policies (NEMA Act, MWE Act, Uganda National Bureau of Statistics -UNBS Act, Local Government Environmental Act). Also, the table indicates that apart from coercive pressures, coercive isomorphic practices arise from ISO 14001:2015 certification and GRI standards, regulator environmental limits (Environmental Monitoring & Reporting, Pollution Charges and Fines); and environmental recommendations (Regulator recommendations, International bodies recommendations). Normative pressures also arise from ISO 140001:2015 certification (Environmental Audits, Environmental Reporting); GRI standards (Environmental Key Performance Indicators). The normative pressures feed into normative isomorphic practices and these arise from environmental mindset (Environmental Partnerships, Capacity Building and Support); industry environmental Expectations (Brand Reputation, Community Expectations); and Partnership with UN Global Compact. Mimetic pressures appear when there is externally perceived pressures a rising from brand reputation of the firm. In parallel, mimetic pressures reveal mimetic isomorphic practices as; Learning from Experienced Firms (Self-Regulation from Peer Learning, Knowledge Transfer); Mimicking Industry Leaders; and presence of Direct Peer Comparison

Table A5 (

Appendix E) presents institutional pressures coercive, normative, and mimetic with their corresponding isomorphic forces that shape CES through various mechanisms. Coercive pressures arise from regulatory audits, acts, and certifications, while normative pressures stem from professional standards, environmental expectations, and partnerships. Mimetic pressures are driven by peer learning and perceived reputational benefits. These pressures result in isomorphic behaviors among firms, influenced by environmental audits, reporting standards, regulator recommendations, and the desire to align with industry leaders.

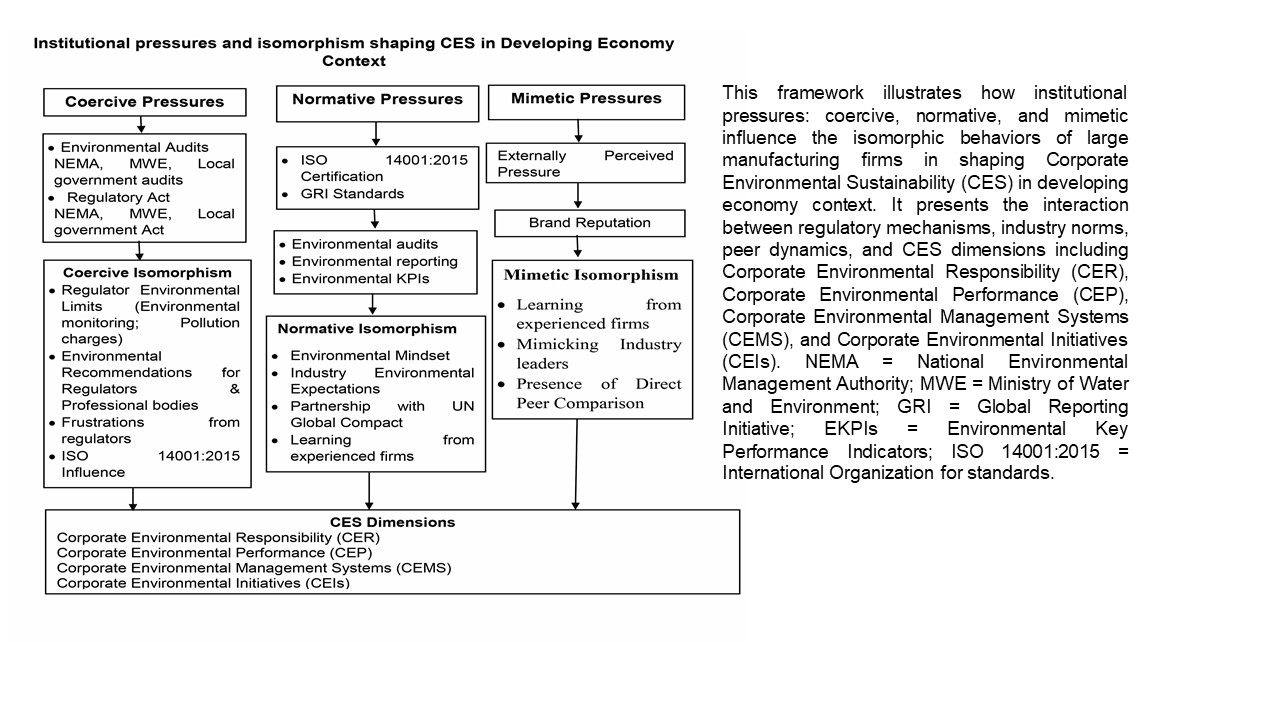

Figure A1: Proposed Framework (Institutional pressures and isomorphism shaping CES)

Figure A1(

Appendix E) illustrates how coercive, pressures and isomorphism; normative pressures and isomorphism and mimetic pressures and isomorphism shape CES.

3.1.1. Coercive Pressures and Isomorphism shape CES

The findings reveal that coercive pressures from regulators in developing economies expressed as environmental audits push large manufacturing firms to reduce on the waste generated during production. By analyzing data across all the interviews conducted, results highlight the following key themes: environmental audits from regulators and adherence to environmental regulatory Act. Large manufacturing firms perceive environmental audits and adherence to environmental Act as integral to their Corporate Environmental Performance (CEP) and Corporate Environmental Initiatives (CEIs). Practices such as establishing pollution measures, operational protocols, waste segregation, waste water treatment, water conservation, energy efficiency are as a result of meeting acceptable environmental audits and adhering to environmental regulations. For instance, participant 21 the standards and compliance officer of firm 21 emphasized that through environmental audits we make check-ups on quantities of waste generated and on the disposal of solid wastes along with treatment of wastes. Also, firms like firm 10 with participant 10 who serves as the Safety, Health and Environmental manager identified environmental regulatory Act as a force that gives the firms a tone to go beyond the minimum standards and put up measures such as investing in water treatment plant, waste segregation, pollution monitors among others. The emerging themes suggest that coercive pressures expressed in-terms of environmental audits from regulators and adhering to environmental regulatory Act are a driving force for large manufacturing firms to establish pollution measures such as air, water, dust and noise monitors; establish operational protocols that reduce firm environmental effect; manage waste through waste segregation; adopt practices such as water conservation and treatment, tree planting, resource recovery systems; and adopt technology that minimizes environmental effect and efficiently use energy.

Findings reveal coercive isomorphic practices in developing economies expressed as regulator environmental limits, environmental recommendations, frustrations from regulators, and ISO 14001:2015 influence. Large manufacturing firms in developing countries perceive these themes as forces that shape CEP and Corporate Environmental Responsibility (CER). For instance, participant 1 who serves as Environmental and Safety Manager at firm 1 states that, the firm has an effluent treatment plant which helps in treating effluent from the factory based on the parameters recommended by the regulators to avoid fines. This implies that large manufacturing firms in developing economies in addition to coercive pressures from regulators, they receive supplementary advice in-form of coercive isomorphic practices such environmental recommendations from regulators, setting pollution limits, regulators’ frustration as stated by participant 11 who serves as Environment, health and safety of firm 11 that the government just come to regulate and the next time they come to close; and influence from ISO 14001:2015.

Figure A1 presents the insights on how coercive pressures and isomorphic practices shape CEP, CER and CEIs.

3.1.2. Normative Pressures and Isomorphism Shape CES

The findings reveal that normative pressures and isomorphic practices shape the way large manufacturing firms respond to CES in developing economies. By analyzing the data, results highlight ISO 140001:2015 certification and GRI standards as frameworks that formalize professional best practices for firms to establish Corporate Environmental Management Systems (CEMS) and improve their environmental performance. These reflect industry expectations and professional standards that encourage firms in developing countries to make environmental audits, and make environmental reports to external stakeholders, indicating the extent the firm pollutes the environment and the measures to mitigate them. For instance, participant 13 who serves as the Environmental, Health and Safety of firm 13 highlight, we have to follow the standards of global reporting initiatives (GRI), however the firm can decide to either report fully or not fully. Findings further reveal the following key themes defining normative isomorphism: environmental mindset (Environmental Partnerships, Capacity Building and Support); industry environmental expectations (Brand Reputation, Community Expectations); partnership with UN Global Compact; and learning from experienced firms (Self-Regulation from Peer Learning, Knowledge Transfer). Large manufacturing firms in developing countries perceive these practices as integral in shaping CER (eco-friendly production, ecological mindfulness, proactive environmental stewardship), CEP (pollution mitigating measures) and CEIs (waste segregation, water conservation and treatment, tree planting). Participant 8 who is the Safety, Health and Environmental manager of firm 8 stated that the firm is a partner of the UN Global Compact for Sustainable Development and that the firm works within the confines of protecting the environment to maintain the partnership. The significance therefore lies in firms being environmentally responsible, improve their environmental performance and engage in environmental initiatives.

Figure A1 presents insights on how normative pressures and isomorphic practices shape CEMS, CER, CEP and CEIs.

3.1.3. Mimetic Pressures and Isomorphic Practices Shape CES

Findings from interviews conducted reveal that mimetic pressures and isomorphic practices shape the way large manufacturing firms in developing countries respond to CES. The analyzed data highlight externally perceived pressure as a force that reminds manufacturing firms of their environmental responsibility. Participant 6 who serves as Health, Safety and Environmental Manager of firm 6 explains that the firm benchmarks from other manufacturers in the industry also producing plastic, though it’s kind of like a pressure to the firm. The significance of external pressures for reputation purposes forces firms to focus on ecological production; be environmentally mindful; and firm being a proactive environmental steward. Findings further reveal mimetic isomorphism expressed in the following themes: learning from experienced firms, mimicking industry leaders and presence of direct peer comparison have an influence over a firm’s ability to become environmentally responsible and engage in environmental initiatives. This implies that when firms in developing economies learn from experienced firms, mimic industry leaders and have firms to compare themselves with, can significantly engage in ecological production, have ecological mindset, will become proactive environmental stewards, segregate waste, plant trees, conserve and treat water and adopt technology that reduces environmental effect.

Figure A1 presents insights on how mimetic pressures and isomorphic practices shape CER and CEIs.

4. Discussions

4.1. Institutional Pressures

Institutional pressures as outlined by institutional theory drive firms towards coercive, normative and mimetic pressures in acting environmentally responsible [

14]. However, this study reveals that in emerging economies these pressures are not uniformly applied or interpreted, instead regulatory mandates are experienced relationally through some form of negotiation and operational flexibility supporting Oliver’s view [

15] that compliance is shaped by willingness and contextual feasibility. This study captures lived experiences of adaptation, showcasing how firms filter industry demands through resource constraints. Mimetic pressures remain weak unless operationalized through visible peer success. These insights suggest that institutional theory must account for local realities. Without clear framework for interpreting or measuring institutional pressures along with isomorphic forces/practices, firms only prioritize only legitimizing pressures and undermining the integrative potential of institutional isomorphic forces in shaping environmental sustainability. Therefore, the proposed framework contributes to institutional theory by incorporating isomorphic practices such as regulator environmental limits, environmental recommendations, regulatory frustrations, ISO 14001:2015 influence, environmental mindset, industry environmental expectations, partnership with UN global compact, absence of peer comparison. The emergent themes are critical elements of institutional theory in the Ugandan context.

4.1.1. Coercive Pressures and Isomorphism Shape CES

The narratives from participants confirm that coercive pressures and coercive isomorphic practices shape CES particularly through environmental audits, regulatory environmental Act/regulatory requirement, regulatory environmental limits, regulatory environmental recommendations, frustrations from regulators and ISO 140001:2015 influence. These themes signified that firms become environmentally responsible (CER), improve their environmental performance (CEP) and engage in environmental initiatives (CEIs) as a result of pressures from the regulators and international bodies. The narratives reflect coercive pressures and isomorphism rooted in regulatory compliance and audit mandate aligning with Alinda et al.

, and Arinaitwe et al. who found that coercive pressures significantly influence firm environmental sustainability [

7,

8]; Vu et al. identified adherence to environmental regulations as the most essential coercive pressures affecting Environmental Cost Management Accounting (ECMA) implementation in Vietnam’s paper industry [

22]. Sun, Sulemana and Agyemang also support the findings that government pressure significantly influences sustainability practices through operationalization of coercive pressure for firms to report [

23]. Okeke’s findings in the oil and gas industry, where coercive pressures significantly enhanced sustainability and supply chain practices further supported the findings of this study that the existence of structured legal requirements is critical in shaping firms’ compliance environmental behavior [

24].

With regulatory environmental limits captured in the interviews, Rai & Asad support that economic penalties such as pollution fines are integral components of coercion that steer firms towards sustainability [

25]. Regulatory frustration was captured as stated by participant 11 who serves as Environment, health and safety of firm 11 that the government just come to regulate and the next time they come to close. This corresponds with Haldorai et al. that coercive pressures though not expressed as isomorphic force, pushes firms to exceed regulatory minimum [

26]. In regards to these coercive pressures and isomorphic frustrations, these perspectives raise concern over the enforcement model supporting punitive closures over friendly recommendations for improvement, which echoes the advisory stance of [

27].

Although scholars from previous studies found that coercive pressures through regulatory compliance affected environmental sustainability, in their study they did not look at regulatory environmental audits as another coercive pressure. Importantly, several prior studies were quantitative with predetermined questionnaire items not specific to a particular theme like environmental Act and environmental audit as identified in this study, the lack of defined themes within coercive pressures limits the capacity to unearth deeper insights that would potentially navigate through the lens of coercive pressures and isomorphic practices. Also, prior studies were too silent about the potential coercive isomorphic practices that move along with the coercive pressures. Views from participants provide action-oriented accounts of how firms in developing economies respond to coercive pressures expressed as regulatory environmental audits and regulatory environmental law. While this adds in-depth value, it also introduces a limitation when compared to a structured quantitative tool with absence of standardized metrics. The interviews of participants enhance contextual validity important in emerging economies with varied enforcement levels. Not all regulatory enforcement agencies across the globe operate in a uniform manner, the views emphasize a unique interaction with local regulators within a developing economy regulatory ecosystem compared to Vu et al.; Khurshid et al. in Asia and the rest of the developed economies [

22,

27].

4.1.2. Normative Pressures and Isomorphism Shape CES

The views of participants strongly affirm that normative pressures and isomorphic practices from professional bodies, industry players and society values shape CEMS, CER, CEP and CEIs, particularly through professional standards, ISO 140001:2015 certification, industry environmental expectations, environmental mindset, partnership with UN Global compact, and learning from experienced firms. Based on the narratives of participant 2 who serves as a Safety and Environmental Manager of firm 2, states that the industry players, government and community expect the firm to do better in conserving the environment. This reflects a collective stakeholder expectation paradigm for environmental stewardship (CER) which aligns with Li et al. that community expectations for environmental responsibility are a central normative pressure that encourages firms to adopt green practices [

28]. Similarly, Yang & Kang emphasized the role that social roles play in shaping environmental behavior especially when environmental practices are the accepted standard within an industry [

28]. For instance, participant 3 who serves as Health, Safety and Environmental Manager of firm 3 states that manufacturing firms are mandated to construct water treatment plants and these are to be monitored by the professional associations, government and the community. This indicates that expectation is not just a legal requirement that coercive pressure may mandate firms, but rather its an industry-wide socially accepted norm. this aligns with Graham who explored industry standards for environmental sustainability as a pressure expressed in a normative form [

29]. With environmental certification, Yang et al. stated that certification is an important dimension because it allows for best practices among firms as a sustainable norm and that such insight suggest that firms operate within normative framework beyond national borders [

30] as participant 8 who serves as Safety, Health and Environmental manager of firm 8 highlighted that the firm is a willing partner to the UN Global Comact for sustainable development. This is further supported by Centobelli et al. who identified global expectations as strong normative influences that propel firms to adopt sustainable practices [

31]. Also, Kian et al. in Malaysian hotels found that external recognition and reputational expectations promoted sustainability practices like food recycling and waste reduction [

32].

The insights by participant 20 who serves as the Health, safety and Environmental manager of firm 20 emphasized that the role of ISO 140001:2015 is for environmental sustainability through compliance because the firm has to comply. ISO 140001:2015 certification is not merely legal mandate but rather reflects the professionalism in operations supported by Arinaitwe et al. who found that normative pressures contributed to energy management practices among SMEs [

8]. However, being that Arinaitwe et al.

, focused on SMEs [

8], normative pressures specifically professional norms and certification requirements set by ISO 14001:2015 may not apply given the financial muscle of SMEs compared to the demands of the certification. With the GRI reporting standards as highlighted by participant 13 who serves as Environmental, Health and Safety of firm 13, GRI reporting standards require a firm to report on environmental issues supported by Okeke., who asserted that industry-wide expectations supported the integration of sustainability in supply chains [

24]. However, participant 13 adds that while GRI report standards require a firm to report on its environmental issues, it does not provide a full-scale reporting metrics rendering firms to either report fully or not fully.

With a contextual view, the study focused on large manufacturing firms in developing economies where international and professional norms are adopted voluntarily often driven by market access and expansion as well as reputational considerations. In contrast, previous studies may have focused on regions with established sustainability certification structures where industry and professional associations play significant normative role. More to that, the views of the participants indicate a mix of normative pressures along with isomorphic practices in role playing towards CES. this diverges from findings of previous researchers whose contexts where normative pressures without its isomorphic practices which renders normative pressures incomplete or under studied. In developing economies like Uganda, large manufacturing firms internalize normative pressures and isomorphic practices as aspirational goals rather than strict obligations leading to a gradual adoption instead of full integration. This explains the inconsistencies that participant 13 highlighted that some firms may report fully while others may choose not to fully report as well as some firms not in procession of ISO 14001:2015 certification. Lastly, earlier studies relied on quantitative tools with structured questions not defined by a particular theme explaining normative pressures. While this provides a generalizability space, they often oversimplify how normative pressures are perceived for instance Alinda et al.; Arinaitwe et al.; Vu et al. [

7,

8,

22] and this renders normative pressures along with isomorphic practices under studied with limitations in replicability and depth. Therefore, the use of an in-depth interview reveals how normative pressures a long with isomorphic practices are interpreted, negotiated and enacted in a dynamic environment where standards are still evolving and not clear framework that applies to the operating environment. This inductive approach enhanced contextual validity though it limits statistical generalization.

4.1.3. Mimetic Pressures and Isomorphism Forces Shape CES

The views of participants affirm that mimetic pressures shape CER and CEIs particularly through externally perceived pressure, benchmarking, learning from experienced firms, mimicking industry leaders and presence of direct peer comparison. For instance, participant 10 who serves as Safety, Health and Environmental manager of firm 10 stated, “of course one would wish to benchmark from he best industry players” which resonates with Zhu, et al. who investigated the role of mimetic pressures in promoting eco-innovation in firms and found that mimetic pressures positively influenced eco-innovation particularly when combined with environmental complexity [

33]. A study by Zibarzani et al. on adoption of Big Data analytics also confirmed the role that mimetic pressures play in achieving sustainable development goals [

34]. In contrast, Li et al. state that mimetic pressures may delay sustainability efforts as firms adopt frameworks from peers in order to meet carbon reduction targets [

28]. This supports the views of participant 17 who serves as Corporate Social Investments Coordinator of firm 17 stating “we are not the monopoly of knowledge….. probably the firm learns from other firms in the industry”.

Mimetic pressure has been measured through observable behaviors like industry adoption and investments in environmental sustainability [

35]. These correspond well with benchmarking behaviors described by participants for example the mention of advanced technologies used by competitors (participant 13) matches the findings of Hsu linking competitor reputation with firms’ willingness to imitate environmental sustainability practices to remain relevant in the industry [

36]. However, the agent-based modeling approach by Zhang et al. revealed that mimetic pressures without other pressures may not yield optimal environmental performance [

37]. This on the other hand may not be supported in a developing economy perspective as participants indicated that firms benchmark from others though its kind of like a pressure but they learn (participant 3). The reliance on mimetic pressures and isomorphic practices in developing economies may be attributed to the need for market penetration and expansion as firms end-up adopting those practices that make them publicly known for their environmental actions. Large manufacturing firms in Uganda like any other developing economy often operate in institutionally fluid environments with much political influence and interferences where environmental sustainability might be limited by such forces [

38]. Such forces may render coercive and normative pressures along with their isomorphic practices ineffective at some point giving the raise and importance of mimetic forces.

This study contributes to the literature on institutional theory and CES by providing an empirically grounded framework tailored to large manufacturing firms in developing economies. Unlike existing models predominantly developed in Global North contexts, this framework integrates contextual nuances such as weak enforcement, limited benchmarking, and reliance on peer influence. It also brings mimetic pressures often underemphasized into the center of CES discourse, expanding the theoretical applicability of isomorphism to environments with fragmented institutional ecosystems.

5. Conclusions

The findings of the study affirm that institutional pressures along with their isomorphic practices shape CES although in ways that are often underrepresented in quantitative research. Unlike traditional studies that employ predetermined questionnaire items for each pressure, the participant narratives in this study reveal how these pressures along with their isomorphic practices can be interpreted and measured in real-time, relational and adaptive ways particularly within the developing economy context. Coercive pressures along with isomorphic practices from regulatory bodies therefore are not perceived solely as only legal mandates but also as relational phenomena characterized by negotiation and operational flexibility. This further highlights the nature of these coercive pressures along with the isomorphic practices in developing economies as dynamic where firms often face fluctuating standards and flexible oversight.

The study reveals that formalized norms from normative pressures through global reporting standards, community norms and professionalism, are often supplemented by isomorphic forces/practices such as environmental mindset, industry environmental expectations, partnerships with environmental agencies, and learning from experienced firms. The contextual reality challenges the assumption that normative pressures are always shaped by professional associations, community norms or industry-wide standards. Instead in developing or poor economies where formal networks are still developing, large manufacturing firms rely heavily on firm exposure, experiential learning and adaptive understanding and interpretation of global environmental norms. The findings enhance the construct validity of normative pressures along with isomorphic forces by grounding in lived experience rather than abstract principles.

The findings also show that mimetic pressures and isomorphic forces shape CES in a developing economy. The inactiveness and interferences in coercive and normative pressures along with their isomorphic forces renders large manufacturing firms to look literally to peers and perceived leaders for environmental strategies and validation. As participants viewed that benchmarking is a form of aspirational learning and a source of indirect pressure revealing a duality often lost in quantitative studies. Therefore, this study enriches the understanding of mimetic pressure and isomorphism by portraying them not as response to uncertainty but as socially embedded practices infused with symbolic meaning.

6. Recommendations

Scholars should explore how the identified institutional pressures and isomorphic forces can be tested statistically for generalizability purposes. Future research could investigate cross-country comparisons especially for developing and developed economies to understand the variance in interpretation and response mechanisms between high-income and low-income regulatory environments.

7. Limitations and Future Research Areas

While the study offers rich qualitative insights, first its scope is limited to large manufacturing firms within a single developing economy context (Uganda), which may affect generalizability. Second, it focused on large manufacturing firms, excluding SMEs that may experience institutional pressures differently. Thirdly, although reflexivity was maintained, interpretation bias may still influence the findings. Future research should expand the scope to include SMEs, explore comparative studies across multiple developing and developed economies to assess the universality of the framework. Quantitative validation of the themes using structural equation modeling or confirmatory factor analysis is also recommended to establish metric validity. Furthermore, stakeholder voices such as communities and civil society organizations should be incorporated to enrich multi-perspective understanding of CES drivers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Kiggundu Tonny, Ntayi Joseph and Nalukenge Irene: methodology, Kiggundu Tonny and Ntayi Joseph: software, Kiggundu and Nkuutu Geofrey: validation, Ntayi Joseph, Nalukenge Irene and Nkuutu Geofrey: formal analysis, Kiggundu Tonny, Nalukenge Irene and Ntayi Joseph: investigation, Kiggundu Tonny, Mugambwa Joshua and Nandagire Muwanga Diana: resources, Kiggundu Tonny: data curation, Ntayi Joseph and Kiggundu Tonny: writing – original draft preparation , Kiggundu Tonny, Nalukenge Irene, Nkuutu Geofrey, Nandagire Muwanga Diana, Mugambwa Joshua and Ntayi Joseph: writing – review and editing, Kiggundu Tonny, Nalukenge Irene and Ntayi Jospeh: visualization, Kiggundu Tonny: supervision, Nalukenge Irene, Ntayi Joseph and Nkuutu Geofrey: project administration, Kiggundu Tonny: funding acquisition, No funding. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

“This research received no external funding”

Institutional Review Board Statement

this study was conducted in accordance to with the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST) and approved by the institutional Review Board of Uganda Management Institute (Protocol code UMIREC-2025-890 in May 2025)

Data Availability Statement

“In accordance with the consent agreement and risk management plan, firms and participants agreed to participate in the study on the condition that their data would not be disclosed to any third party. As such, sharing the data would constitute a breach of the agreement between the researchers, the participating firms, and the individual participants.”

Acknowledgements

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

Abbreviation

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CES |

Corporate Environmental Sustainability |

| CER |

Corporate Environmental Responsibility |

| CEP |

Corporate Environmental Performance |

| CEMS |

Corporate Environmental Management Systems |

| CEIs |

Corporate Environmental Initiatives |

| QNM |

Questions Needing Modification |

| NBM |

Questions Needing to Be Maintained |

| NBMW |

Questions Needing to Be Merged With others |

| NBR |

Questions Needing to Be Removed |

| MWA |

Ministry of Water and Environment |

| NEMA |

National Environmental Management Authority |

| GRI |

Global Reporting Initiative; |

| EKPIs |

Environmental Key Performance Indicators. |

| ISO 14001:2015 |

International Organization for standards. |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Demographic Characteristics of Firm-level participants.

Table A1.

Demographic Characteristics of Firm-level participants.

| Participant ID |

Age |

Company Experience |

Position |

Experience |

Number of Employees |

Location |

Company Products |

Field |

Education |

| Participant 1 |

42 |

29 |

Environmental and Safety Manager |

6 |

531 |

Central |

Pharmaceutical Products |

Environmental Science |

Masters |

| Participant 2 |

38 |

20 |

Safety and Environmental Manager |

7 |

875 |

Central |

Soft drinks, Biscuits, Water, Tomato Sauce, Plastics |

Environmental Science, Agro Forestry |

Bachelors |

| Participant 3 |

32 |

21 |

Health, Safety and Environmental Manager |

5 |

712 |

Central |

Expanded Metal, Iron sheets, Chain link, wires, bars hole sections |

Environmental Science and Management |

Bachelors |

| Participant 4 |

33 |

65 |

Safety, Health and Environmental Manager |

6 |

588 |

Eastern |

Cushioning Mats |

Environmental Impact Assessment |

Postgraduate Diploma |

| Participant 5 |

35 |

31 |

Environmental Manager |

5 |

598 |

Western |

Cement Products |

Electronics and Environmental Assessment |

Masters |

| Participant 6 |

36 |

22 |

Health, Safety and Environmental Manager |

10 |

1200 |

Central |

Soft drinks, Biscuits, Water, Confectionary, Energy drinks |

Environmental Science, Technology and Management |

Masters |

| Participant 7 |

43 |

38 |

Environmental and Safety Manager |

15 |

613 |

Central |

Milk and milk products, juice |

Environmental and National Resources |

Masters |

| Participant 8 |

45 |

19 |

Safety, Health and Environmental manager |

7 |

7500 |

Eastern |

Sugar, Rum, vodka, whiskey |

Certificate in Environmental Management |

Bachelors |

| Participant 9 |

37 |

36 |

Safety, Health and Environmental manager |

8 |

576 |

Central |

Packaging products, Plastics |

Human Resource; and Environmental Assessment |

Masters |

| Participant 10 |

28 |

27 |

Safety, Health and Environmental manager |

3 |

1001 |

Central |

Radiant, Skin guard, Tropical Essence |

Environment and Natural Resources |

Masters |

| Participant 11 |

31 |

44 |

Environment, health and safety |

6 |

7000 |

Central |

Baking fats, cooking oils, Animal feed, Soap, Water, Plastics, Detergent podwer |

Environmental Engineering and Management |

Bachelors |

| Participant 12 |

26 |

33 |

Health and Safety Manager |

3 |

1023 |

Central |

PVC, HDPE pipes, PE pipes, polyethylene pipes, polyvinyl chloride pipes |

Environmental Management |

Bachelors |

| Participant 13 |

42 |

54 |

Environmental, Health and Safety |

12 |

489 |

Central |

Plastic products |

Environmental Management |

Masters |

| Participant 14 |

47 |

67 |

Environment Assessment Manager |

12 |

1500 |

Western |

Vegetable cooking oil, cotton husks, cotton cakes, animal feeds |

Social Work and Social Administration |

Bachelors |

| Participant 15 |

38 |

19 |

Safety, Health and Environmental manager |

7 |

1080 |

Eastern |

Cooking oil, Soap |

Environmental Engineering |

Bachelor |

| Participant 16 |

37 |

17 |

Environmental, Health and Safety manager |

5 |

382 |

Central |

Colligated boxes |

Human Resources Management; and Environmental Management |

Postgraduate Diploma |

| Participant 17 |

37 |

29 |

Corporate Social Investments Coordinator |

3 |

2000 |

Central |

steel and plastics products like, water pipes, borehole pipes, conduits |

Environment and Social Impact Assessment |

Masters |

| Participant 18 |

34 |

38 |

Environment Occupation safety and Health Coordinator |

6 |

487 |

Central |

Natural mineral water, minute maid, added value dairies |

Environmental Management |

Bachelors |

| Participant 19 |

36 |

19 |

Corporate Social Responsibility Coordinator |

8 |

312 |

Eastern |

Vegetable cooking oil, Banking fats |

Sociology and Social Administration, Certificate in Environmental Assessment |

Bachelors |

| Participant 20 |

31 |

75 |

Health, safety and Environmental manager |

7 |

1032 |

Central |

Beer, spirits, cocktail |

Environmental Management and Conservation |

Masters |

| Participant 21 |

32 |

15 |

Standards and Compliance officer |

8 |

3280 |

Central |

Cotton products i.e; Fabrics, clothes, cotton yarn |

Environmental Management; Mechanical; Legal and Diversity |

Bachelors |

| Participant 22 |

28 |

73 |

Environmental Manager |

5 |

610 |

Eastern |

Beer, Castle Milk Stout, Castle Lite |

Environmental Science |

Bachelors |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Demographic Characteristics of Regulatory Officials.

Table A2.

Demographic Characteristics of Regulatory Officials.

| Participant ID |

Age |

Experience |

Years in Existence |

Education |

Field |

| MWA |

43 |

14 |

17 |

Masters |

Environmental Science |

| NEMA |

36 |

9 |

29 |

Masters |

Environmental Engineering |

Appendix C

Table A3.

Interview Questions Pre-Test Matrix Tool (Firm-level participants).

Table A3.

Interview Questions Pre-Test Matrix Tool (Firm-level participants).

| No |

Interview Question |

QNM |

NBM |

NBMW |

NBR |

| |

Do institutional pressures, shape CES? |

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

What does government, industry firms and community think the company can do better to help the environment and the community |

|

|

|

|

| 2 |

How do partnerships with NEMA and international community enhance your environmental management, particularly in tracking and reducing emissions |

|

|

|

|

| 3 |

How has adherence to international environmental regulations shaped your sustainability practices? |

|

|

|

|

| 4 |

Are you a member of the UN Global Compact? |

|

|

|

|

| 5 |

How does involvement in the UN Global Compact influence your environmental and social governance, especially concerning clean energy? |

|

|

|

|

| 6 |

Do you have ISO certificate? Which certificate do you have? |

|

|

|

|

| 7 |

What role does the ISO certificate play in sustainability? |

|

|

|

|

| 8 |

Can you provide examples of how your company has collaborated with external partners (e.g., suppliers, NGOs) to support environmental sustainability in manufacturing? |

|

|

|

|

| 9 |

How has adherence to international environmental regulations shaped the firm’s environmental sustainability practices? |

|

|

|

|

Appendix D

Table A4.

Interview questions pre-test matrix Tool (Regulatory officials).

Table A4.

Interview questions pre-test matrix Tool (Regulatory officials).

| No |

Interview Question |

QNM |

NBM |

NBMW |

NBR |

| |

Do institutional pressures, shape CES? |

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

Do you believe pressures NEMA and Ministry of Water and Environment to the company can be more active in solving environmental problems? |

|

|

|

|

| 2 |

Do partnerships with NEMA, Ministry of Water and Environment as well as the international community enhance the firm’s environmental management, particularly in tracking and reducing emissions? |

|

|

|

|

| 3 |

Can you provide examples of how companies have collaborated with NEMA and Ministry of Water and Environment or any other stakeholder to support environmental sustainability? |

|

|

|

|

| 4 |

Does involvement in the UN Global Compact influence the firm’s environmental and social governance, especially concerning clean energy? |

|

|

|

|

| 5 |

What role does the ISO 140001:2015 certificate play in sustainability? |

|

|

|

|

Appendix E

Table A5.

Generated Themes.

Table A5.

Generated Themes.

| Major Themes |

Sub-Themes |

Representative codes |

| Coercive pressures |

Environmental Audits |

Regulatory Audits

|

| Regulatory Act |

NEMA Act

MWE Act

KCCA Environmental Act |

| ISO 14001:2015 certification Requirements |

|

| GRI Standards |

| Coercive Isomorphism |

Regulator Environmental Limits |

|

| Environmental Recommendations |

|

| Frustrations from Regulators |

|

| ISO 14001:2015 Influence |

| Normative pressures |

ISO 14001:2015 certification Requirements |

Environmental Audits Environmental Reporting EKPIs |

| GRI Standards |

| Normative Isomorphism |

Environmental Mindset |

|

| Industry Environmental Expectations |

Brand Reputation Community Expectations |

| Partnership with UN Global Compact |

|

| Mimetic pressures |

Externally Perceived Pressure |

Brand Reputation |

| Mimetic Isomorphism |

Learning from Experienced Firms |

|

| Mimicking Industry Leaders |

|

| Absence of Direct Peer Comparison |

Appendix F

Figure A1.

Proposed Framework (Institutional pressures and isomorphism shaping CES).

Figure A1.

Proposed Framework (Institutional pressures and isomorphism shaping CES).

References

- Nkwetta, A.A. Ngangnchi, F. H.; Mukete, E.M. Industrialization and environmental sustainability in Africa: The moderating effects of renewable and non-renewable energy consumption. 2024, 10, e25681. [Google Scholar]

- Jayaram, K.; Kendall, A.; Somers, K.; Bouchene, L. Africa’s green manufacturing crossroads: Choices for a low-carbon industrial future. Mckinsey Sustainability. 2021.

- Global. Global South can tackle air pollution, climate change with new approaches and solidarity. 2025.

- Watts, J. Global temperatures could break heat record in next five years. Climate crisis 2025.

- Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development. (2022). Climate Risk Profile: Uganda.

- Abet, T. (2024). Researchers link over 7,000 deaths in Kampala to air pollution. Monitor ePaper.

- Alinda, K. Tumwine, S. Nalukenge, I. Kaawaase, T.K. Sserwanga, A. Ståle N. (2024). Institutional pressures and sustainability practices of manufacturing firms in Uganda. Wiley Online Library. [CrossRef]

- Arinaitwe, A.; Tukamuhabwa, B.R.; Bagire, V.; Nkurunziza, G.; Nassuna, A. “Nudging manufacturing small and medium enterprises in developing communities to energy management: Exploring the role of institutional pressure dimensions”. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy 2024, 18, 1337–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Rasheed, R.; Altay, N. “Greening manufacturing: The role of institutional pressure and collaboration in operational performance”. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management 2025, 36, 455–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzolari, T.; Genovese, A.; Brint, A.; Seuring, S. “Unlocking circularity: The interplay between institutional pressures and supply chain integration”, International Journal of Operations & Production Management 2025, 45, 517–541. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K. “Impact of leadership, TQM and supply chain capabilities on sustainable supply chain performance: Moderating role of institutional pressure”, The TQM Journal 2025, 37, 953–976. [CrossRef]

- Can, O.; Turker, D. , (2025). , “Institutional pressures and greenwashing in social responsibility: Reversing the link with hybridization capability”, Management Decision 2025, 63, 187–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.U.; Badulescu, D. Sustainability Pressures Unveiled: Navigating the Role of Organizational Sustainable Culture in Promoting Sustainability Performance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell. W.W. ’The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective reality in organizational fields’. American Sociological Review 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C. ’The collective strategy frame work: An application to competing predictions of isomorphism’. Administrative Science Quarterly 1988, 33, 543–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodstein, J.D. Institutional pressures and strategic responsiveness:614 employer involvement in work–family issues. Acad Manage J 1994, 615, 350–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative inquiry. Aldin,Chicago.

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed methods approach. Fifth Edition.

- Malmqvist, J.; Hellberg, K.; Möllås, G.; Rose, R.; Shevlin, M. Conducting the Pilot Study: A Neglected Part of the Research Process? Methodological Findings Supporting the Importance of Piloting in Qualitative Research Studies. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research In Psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.T.P.; et al. , (2025). Stakeholders’ pressures and manager awareness toward the implementation of environmental cost management accounting: Empirical evidence in Vietnam paper enterprises. Economic Sustainability and Social Equality in the Technological Era– Taylor & Francis Group, London, 978-1-032-87792-1. Open Access: www.taylorfrancis.com, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.

- Sun, G.; Sulemana, I.; Agyemang, A.O. , (2025), “Examining the impact of stakeholders’ pressures on sustainability practices”, Management Decision, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. [CrossRef]

- Okeke, A. , (2025), “Navigating institutional pressures: Assessing sustainability and supply chain management practices in the oil and gas industry of a developing economy”, International Journal of Energy Sector Management, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. [CrossRef]

- Rai, F.H.; Asad, F. Navigating Coercion: Assessing the Impact of Governmental Influence on Firms’ Eco-Friendly Practices 2025. [CrossRef]

- Haldorai, K.; et al. , (2025), “Top management commitment, institutional pressures and green supply chain practices: Pathways to sustainable performance”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. [CrossRef]

- Khurshid, A.; Hanif, M.S.; Sajid, A.; Zaki, W. Highlighting the Leadership Role of Top Management and Business Strategy Between Institutional Pressures and the Adoption of Environmental Management Accounting. International Journal of Organizational Leadership 2025, 14, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wu, T.; Zhang, P.; et al. Can institutional pressures serve as an efficacious catalyst for mitigating corporate carbon emissions? Environ Sci Pollut Res 2024, 31, 21380–21398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S. The influence of external and internal stakeholder pressures on the implementation of upstream environmental supply chain practices. Bus. Soc. 2020, 59, 351–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A. Saffer, Y.; Li. Managing stakeholder expectations in a politically polarized society: An expectation violation theory approach. J. Int. Crisis Risk Commun. Res. 2020, 3, 275–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centobelli, P. Cerchione, R.; Cerchione, E. Pursuing supply chain sustainable development goals through the adoption of green practices and enabling technologies: A cross-country analysis of LSPs. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2020, 153, 119920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kian, A.C.; Ab Aziz, N.; Joann, P.S.L.; Md Zabri, M.Z. Adopting circular food practices in Malaysian hotels: The influence of isomorphic pressures and environmental beliefs, International Journal of Hospitality Management 2025, 127, 104113, ISSN 0278-4319. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Det, a.l. Institutional Pressure and Eco-innovation: The Moderating Role of Environmental Uncertainty. Science, Technology and Society 2024, 29, 160–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibarzani Met, a.l. The impact of big data adoption on competitive advantage in achieving sustainable development goals: The moderating role of mimetic pressure. Environ Dev Sustain. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Suhaiza, H.M.Z. Tarig K, Eltayeb. Chin-Chun Hsu and Keah Choon Tan. “The impact ofexternal institutional drivers and internal strategy on environmental performance”. International Journal of Operations &Production Management 2012, 32, 721–745. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, K.-T. The advertising effects of corporate social responsibility on corporate reputation and brand equity: Evidence from the life insurance industry in Taiwan. J Bus Ethics 2012, 109, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xiong, H.; Wang, G.; et al. How institutional pressures improve environmental management performance in construction projects: An agent-based simulation approach. Environ Dev Sustain 2024, 26, 1281–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oweyegha, A. (2025). Environmental Sabotage on The Rise in Uganda As Accountability of Power Declines. Environment & Climate.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).