1. Introduction

Professional education aims to train individuals who possess knowledge and can develop essential, technical, and socio-emotional skills to succeed in the job market. Concomitant to this, the organizational environment seeks agents of change who support a new vision to advance the company's integral performance through environmental, social, and governmental factors (

Boiral et al., 2014).

Given these purposes and perspectives, there is a recurring concern regarding the sustainable development of organizations, the preservation of environmental resources, and the commitment to present-day human beings without compromising the needs of future generations (

Romão et al., 2023). A common mistake is equating sustainable development with environmental concerns (Agne et al., 2021).

The contrast of interpretations prolongs adaptation to new routines and organizational business model transformation (

Roome & Louche, 2016). The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) postulate challenges to address these gaps. The SDGs present emerging sustainability concepts and frameworks, distributed across 169 goals, that address social, economic, and environmental challenges (

Khoshnava et al., 2019). The 2030 Agenda incorporates a set of seventeen interconnected objectives, which are a global agenda for sustainable development.

This research focuses on SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption) with particular emphasis. The critical interdependence between education, sustainable consumption, and production practices informs the choice to focus on these two SDGs. While SDG 4 aims to ensure inclusive, equitable, and quality education, promoting lifelong learning opportunities for all, SDG 12 focuses on the urgent need to ensure sustainable patterns of consumption and production, addressing the efficient use of natural resources and reducing waste and environmental degradation (

Hoernig & Junior, 2021). By emphasizing these two objectives, the research provides an integrated approach that recognizes education as a catalyst for behavioral change and sustainable practices.

Given the above, the research problem is: Which actions can be implemented to promote sustainable organizational development through success stories, failure factors, and awareness of the agents involved? This investigation is expected to contribute to achieving the goals of the 2030 Agenda by spreading knowledge on topics related to sustainable development and promoting practices that support organizational sustainability.

In this sense, the research aims to analyze the actions that can promote sustainable organizational development through success stories, failure factors, and awareness of the agents involved.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Agenda 2030

The foundations for the 2030 Agenda were laid. The document “Transforming Our World”, adopted at the UN General Assembly in 2015, was created collectively to find a more sustainable and resilient path until 2030 (Delgado et al., 2020). The 2030 Agenda is a global action plan that encompasses 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which are further broken down into 169 specific goals focused on eradicating poverty and promoting a dignified life for all (

Tuholske et al., 2021).

The SDGs present a set of aspirations and priorities that address urgent challenges for all countries (UN, 2015). Meeting the challenges aims to maintain the quality of life for future generations and achieve these goals from 2015 to 2030. According to this assumption, combined with the publication of the UN's objectives and targets in 2015 (

Tuholske et al., 2021), the 17 SDGs highlight latent themes on the planet, such as water, food, gender equality, energy, education, and health, among others.

Narrowing down the understanding of the organization of the SDGs, it is noted that they encompass three elements: economy, society, and environment (

Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2021) and configure interconnections and interdependencies (

Oliveira, 2021) between people, planet, prosperity, peace, and partnership. In planet interconnection, the commitment aims to protect the planet from human degradation (

Rosati & Faria, 2019) and is mainly related to SDGs 6, 7, 13, 14, and 15. The commitment to prosperity interconnection ensures alignment between economic, social, and technological development and growth, without harming nature (

Oliveira, 2021); this aligns closely with objectives 8, 9, 11, and 12. Peace fosters a fairer and more inclusive society (

Alkhayer et al., 2022), aligning with approaches highlighted in SDGs 5, 10, and 16. The partnership primarily involves a global alliance (

Junges et al., 2020) in Objective 17.

The SDGs are interconnected and must be addressed systemically (Van Der Waal et al., 2020). It means that the objectives are interconnected, and one depends on the development of the other; achieving one goal can impact the achievement of the other.

2.2. Sustainable Development in Organizations

Sustainable development can be conceptualized as a management process that aims to generate long-term well-being and ensure lasting value, considering social, environmental, and economic factors (

Suriyankietkaew & Avery, 2016). Given this definition, many organizations, including several leading companies in their segments, have accepted sustainability, but gaps and needs remain.

Although there is an awareness of assuming positions of sustainable responsibility with long-term results and everyone's satisfaction, some investors still seek to earn increasing profits in a short period, generating tensions that detract from the macro context (

Klettner et al., 2014). This synchrony of social responsibility and development requires organizations to undergo an analytical filter, necessitating conscious management that assesses risks and identifies adaptation routes involving incremental changes to maintain well-being, economic gains, and a natural support system (

Nicolletti et al., 2020).

In practice, it is often necessary to clarify how to utilize natural resources, consume energy and water, reduce resource consumption, and plan industrial operations to minimize environmental impacts and mitigate losses (

Agwu & Bessant, 2021). Over the years, the scope of sustainable development in organizations has evolved. The previously segregated focus on financial health, profits, and revenue was expanded to encompass two additional pillars. These pillars encompass social relationships, clientele, and suppliers, as well as the value we aim to deliver to the community.

These dimensions constitute the triple bottom line, guiding value creation for stakeholders.

Fauzi et al. (

2010) mention the triple bottom line by conceptualizing its dimensions as people, planet, and profitability. By applying measures that create a favorable working environment, minimizing ecological damage without ignoring community development (

Okanga & Groenewald, 2017). This triple result aims to achieve economic, social, and environmental benefits, all while improving the quality of human life (

Agwu & Bessant, 2021).

The organizational environment is well-suited for promoting interactive and participatory learning experiences, fostering strategic thinking to address economic, social, and environmental challenges (

Palma & Pedrozo, 2019). This is because society is responsible for the productive construction of the planetary system, encompassing the animal, vegetable, and mineral kingdoms (

Huerta et al., 2021).

2.3. Education for Sustainable Development

In the context of vocational training, sustainability education must connect learning with practical action in industrial environments. From these processes, individual habits and behaviors that point to a path of transformation must be targeted.

Education, generation, and use of knowledge become essential tools for interactive processes in which everyone learns and acts not as passive recipients but as active agents supporting systematic changes for future challenges. Sustainable development in this context mobilizes principles and values, displacing personal beliefs and values.

This assumption is highlighted most prominently in SDG 4, as it signals concern about the beginning of students' careers, equal educational access in search of eliminating the disparity of wealth between students and substantially for the deployment of skills, technical and professional competencies young people and adults towards employment, decent work and entrepreneurship, through quality education (UNDP, 2022).

The Global Goals do not intend to provide immediate solutions to existing problems, but instead aim to encourage sustainable solutions to all global challenges. The year 2020 marked the beginning of the so-called Decade of Action, aimed at achieving the goals outlined in the 2030 Agenda, by mobilizing everyone, everywhere, to strive for urgency and ambition in transforming ideas into solutions (ONU Brasil, 2021). Sachs (1993) explored aspects in his studies on the dimensions of sustainability that reaffirm the importance of human awareness in the current planetary context.

3. Method

This research was developed using a qualitative approach with depth to address specific issues, providing a level of reality that cannot be quantified. Based on the exploratory nature, this definition understands that the investigation will focus on understanding organizational social processes and interactions (

Yin, 2015). Another classification of the study is action research, which enables the collection of socially relevant data by being conceived and carried out in response to a collective problem.

3.1. Study Area and Agents Involved

In line with Yin (2015), it was decided that this study should consider two companies that comprise the representative cases of the approaches under analysis. It involved collaborating with a professional training center and a company in the industrial sector in southern Brazil. The company has been operating since 2001, manufacturing winches, ratchets, and pulleys for use in poultry, agricultural, road, and nautical applications. The work presents innovative solutions for various segments, mainly in the poultry and agricultural markets. The factory is located in a city in the state of RS. The Professional Training Center is a private, non-profit institution of public interest. Its main objective is to support 281 industrial areas by training human resources and providing technical and technological services.

3.2. Data Collection Instrument and Procedures

To collect information, a semi-structured interview guide and a research protocol were prepared (

Yin, 2015). Subsequently, interviews, observations, and focus groups were conducted to enhance the security and reliability of the work (Gibbs, 2009). These techniques enabled in-depth investigation, interaction in the inquiry, and appropriation of the perspectives of the interviewed subjects, a frequently used approach in qualitative research that allows flexibility during the study.

Another instrument that contributed to data collection was direct, non-participant observation, with no interference in the context (

Yin, 2015). This technique enables the collection of in-depth information about reality, often combined with other methods, such as interviews, and involves the researcher's use of their senses to examine facts or phenomena of interest.

The focus group helped to understand the different perceptions and attitudes regarding a fact or practice. It is considered a group interview, although not in the sense of a process where questions from the researcher and answers from participants’ alternate. It is based on the tendency to form opinions and attitudes when interacting with others (

Iervolino & Pelicioni, 2001).

3.3. Procedures

The script was evaluated and validated by two

experts, professors of the Master's Program in Administration, to give credibility and validity to the study (

Yin, 2015). It is, therefore, assumed that this approach will detect flaws in the construction and divergences in interpretation on issues that affect the scope of the results (

Yin, 2015). Hybrid interviews were scheduled in advance, taking into account the participant's shift and available time.

They were recorded in audio, with the prior authorization of the respondents, and later transcribed to preserve aspects that are often lost during the transition from conversations (Gibbs, 2009).

Another point to be highlighted by Gibbs (2009) is that transcription raises issues of precision, fidelity, and interpretation. After these transcriptions (39 pages), the

recordings were deleted from all electronic devices (computer, recorder). Based on the above, the triangulation of procedures - interviews, observation, and focus groups - allowed various sources of evidence to validate, strengthen, and corroborate research results, increase reliability, and overcome limitations arising from a single technique (

Yin, 2015).

3.4. Data Analysis Technique

The content analysis technique was used (

Bardin, 2016). This technique involves discovering the essence of meaning that comprises communication through three stages: pre-analysis, exploration of the material, treatment, inference, and interpretation of results. Bardin (2016) argues that this technique seeks to go beyond the appearances of the data, enabling the researcher to search for the latent, the non-apparent, and the previously unexplored potential retained by any messages, especially those arising from interviews and observations. From this perspective, information was compiled using coding, enumeration, categories, and frequency to present the results (

Bardin, 2016). Thus, it was possible to have in-depth and latent discussions of this research's findings. It is worth noting that the categories for this study were scored

a posteriori to data collection.

4. Results

In order to understand the interviewees' perceptions of sustainable development and society's participation in sustainable actions, three categories were listed:

sustainability, economic development, and awareness. These categories were a posteriori, based on the analysis of the collected reports. Regarding organizational sustainable development, in the sustainability category, 42 reports focused on the environmental context. Regarding economic development, 16 reports were highlighted. It was recognized that sustainability is necessary, but it requires economic investment. In this sense, sustainable development is not directly accessible to people, and responsibility is often transferred to public or private authorities.

Table 2.

Content analysis of environmental, social, and economic dimensions.

Table 2.

Content analysis of environmental, social, and economic dimensions.

| Categories |

Subcategories |

Context Unit |

Enumeration |

Frequency |

|

| Environmental |

Success Stories |

“...we have our mug to drink our coffee...” |

28 |

45.90% |

|

| "The barrels are used for tables, stools, and pallets as sofas..." |

|

| Failure Factors |

“...also a PET bottle for water, for the student...” |

|

|

|

| “...collective action for society to adopt outdoor gyms...” |

|

| 19 |

52.78% |

|

| Social |

Success Stories |

"Inside the classroom, for students to be aware of the correct waste disposal..." |

22 |

36.06% |

|

| "We participate in clothing campaigns and contribute to the community..." |

|

| Failure Factors |

"Charitable campaigns, among others, that certainly help many people..." |

12 |

33.33% |

|

| Voluntary actions that we can do, right, to help the municipality...” |

|

| Economic |

Success Stories |

“...printing of documents is very few, certificates and communications are all sent by the digital secretariat”. |

11 |

18.04% |

|

| "To form a class, there is a minimum amount; I think that goes a long way regarding financial sustainability, right?" |

|

| |

Failure Factors |

"...here we sell courses on solar panels, but we do not have one here, for example." |

5 |

13.88% |

|

| "Reusing rainwater... LED lamps, of course, involve an investment issue." |

|

The alignment between sustainable development and economic growth guarantees an interconnection of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The desire to achieve this balance without harming nature and promoting a fairer and more inclusive society is evident in the 52.78% collection frequency rate.

Table 3 presents the interviewees' reports, organized by environmental, economic, and social dimensions. It expresses the connection between economic dimension, awareness, and sustainability categories. It is noted that awareness-raising actions are understood as a social characteristic, resulting in 60.61% of.

Reports.

On the other hand, 90% of the responses consider that the economic dimension is decisive for sustainable development.

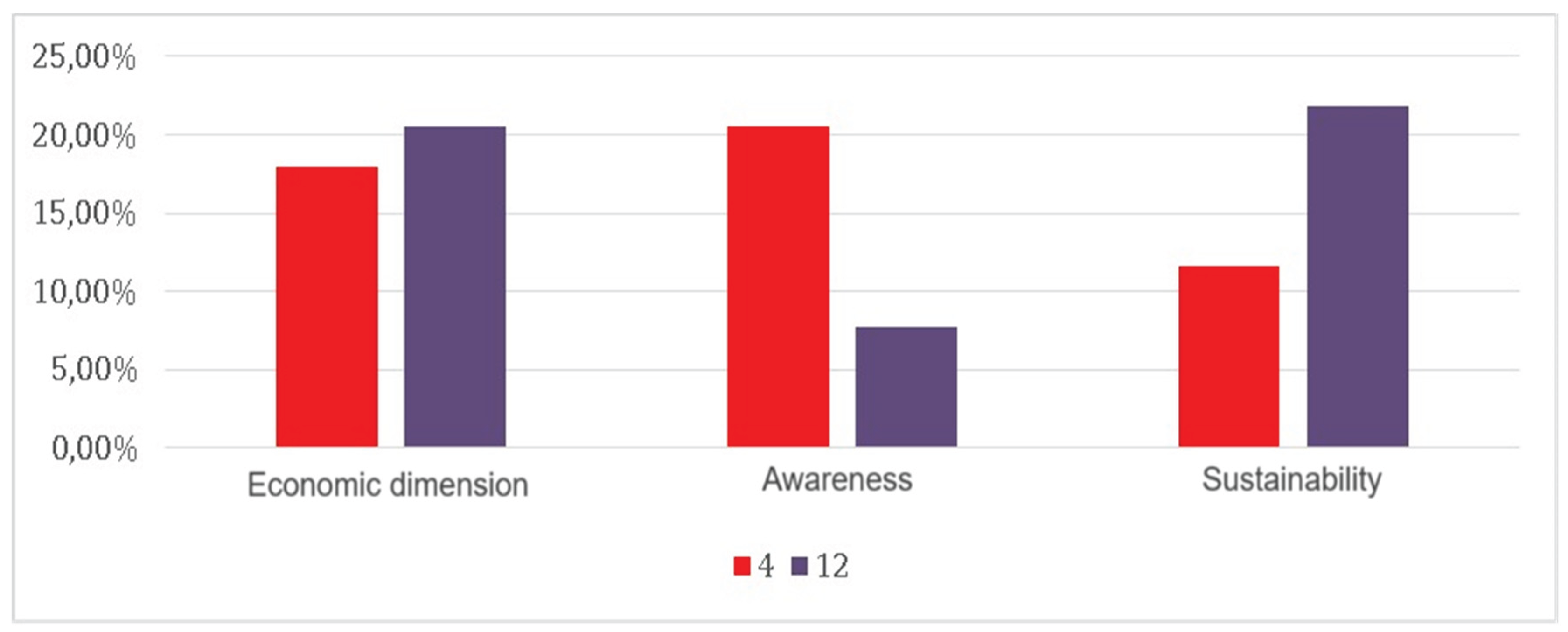

Based on the understanding that the 2030 Agenda is a global action plan that brings together 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs),

Figure 4 considers SDG 4—Quality Education (red) and SDG 12—Responsible Consumption (mustard) and indicates how interviewees interpret and construct concepts, aiming for a dignified life for everyone and future generations (

Tuholske et al., 2021).

Following the research, the participating organizations, the company, and the school community were challenged to propose solutions for SDGs 4 and 12. The solution emerged when students and instructors identified that recyclers often burn cables to remove the plastic and use the copper. This action causes the incineration of the plastic covering on electrical cords and wires outdoors to recover copper, generating emissions that are harmful to the environment.

Using the wire stripper, the Vocational Training Center will deliver scraps of stripped cables and wires for recycling. This equipment is being used in classes on the Industrial and Building Electrician courses, deepening knowledge about responsible production and consumption in an equitable, inclusive, and quality education environment (Leal Filho et al., 2021). A schedule of dates, themes, and activities was developed for the company. The actions brought students closer to the actual demands of the industry and strengthened their link with the job market. This research proposal addresses the monitoring and encouragement of young people to begin their professional careers through the development of the SDGs.

Quality education and equal access to skills development and technical competencies eliminate wealth disparity (PNUD, 2022). The Professional Training Center partnered with a biofuel-producing company on a project aimed at qualifying raw material suppliers for biofuel production. This initiative is aligned with ESG principles and aims to contribute to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), with a specific focus on SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production).

The proposal helped to structure ESG guidelines and pillars, promoting organizational sustainable development in the environmental dimension (legal requirements, environmental management system, sound environmental practices, and educational awareness), social dimension (legal requirements, occupational health and safety system, social practices and initiatives); governance dimension (organizational management, governance practices, and educational awareness). Recognizing success stories and failure factors generated opportunities to integrate the SDGs and the goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development into organizations.

Sustainable Development into organizations. In addition to this work, the City Hall, through the Department of Environment, adopted the initiative developed by students in the industrial learning courses in Mechanics and Electricity. The action aimed to promote and encourage the proper disposal of household waste, including cooking oil and batteries. When delivering domestic waste to the Vocational Training Center, the community received a tree seedling donated by the city hall, encouraging collection. The partnerships facilitated the implementation of measurable sustainability practices aligned with SDG 12. The study demonstrates that practical projects and partnerships enhance youth engagement and foster implementation of SDGs 4 and 12. By achieving this purpose, it was possible to generate knowledge and contribute to the local and global social, economic, and environmental growth of communities, addressing future challenges.

5. Discussion

This research aimed to promote corporate sustainability by identifying success stories and failure factors related to SDGs 4 and 12. The findings demonstrate that vocational education and industrial collaboration can contribute meaningfully to the 2030 Agenda. Effective implementation of sustainability initiatives requires both financial investment and continued human engagement.

The collected data indicate progress across environmental, social, and governance dimensions. While managers and professionals showed commitment to sustainability practices, the involvement of young participants was particularly relevant. Their integration into company processes revealed the potential of education to foster awareness and incorporate SDG principles into daily operations.

However, 44% of the interviewees provided vague responses about sustainable development, reinforcing the need for targeted training to strengthen understanding of the SDGs and align ongoing efforts with specific indicators. Additionally, 90% of participants emphasized the importance of financial support for the success of sustainability actions.

The predominance of environmental aspects (80%) in the responses suggests that social and governance dimensions remain underexplored. Future initiatives should promote greater integration among the three pillars, highlighting the role of the circular economy and conscious consumption.

Expanding the scope of SDGs analyzed in similar contexts may reveal new applications and challenges. Although political and multicultural factors were not addressed in this study, they are relevant for the adoption and scaling of sustainability practices. The collaboration between vocational education and industry demonstrates a replicable model for enhancing SDG implementation and advancing inclusive, long-term sustainable development.

References

- Afolaranmi, A. O., and A. A. Amodu. 2022. Critical Review of Sustainable Peace, Mediative Dialogue and Social Media. Critical Review 5, 3: 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agne Tybusch, F. B., and P. Silva. 2021. Desenvolvimento sustentável versus bem-viver: a necessidade de buscar meios alternativos de vida. Opinión Jurídica 20, 43: 615–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agwu, U. J., and J. Bessant. 2021. Sustainable business models: A systematic review of approaches and challenges in manufacturing. Revista de Administração Contemporânea 25, 3: 200–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhayer, J., N. Gupta, and C. M. Gupta. 2022. Role of ADR methods in environmental conflicts in the light of sustainable development. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 1084, 1: 12057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardin, L. 2016. Análise de Conteúdo, 3ª ed. Lisboa, Portugal: Edições 70. [Google Scholar]

- Boiral, O., C. Baron, and O. Gunnlaugson. 2014. Environmental leadership and consciousness development: A case study among Canadian SMEs. Journal of Business Ethics 123, 3: 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junges, V., S. G. Telocken, and S. A. P. de Campos. 2020. Ação Coletiva como Forma de Ampliar a Educação para a Sustentabilidade: Uma Discussão à luz da Agenda 2030. Revista de Administração IMED 10, 1: 106–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, H., G. Svensson, and A. Rahman. 2010. "Triple bottom line" as "Sustainable corporate performance": A proposition for the future. Sustainability 2, 5: 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grainger-Brown, J., and S. Malekpour. 2019. Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals: A review of strategic tools and frameworks available to organisations. Sustainability 11, 5: 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, R., and L. L. Price. 2019. Consumer journeys: developing consumer-based strategy. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 47, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoernig, A. M., and B. A. H. Junior. 2021. A sustentabilidade ambiental efetivada através da gestão educacional. Revista Angolana de Ciências 3, 2: 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, J. M., R. Cayumil Montecino, and M. Sánchez Medina. 2021. Una aproximación termodinámica para la comprensión de la economía circular aplicada al ámbito minero-metalúrgico. Revista de Medio Ambiente y Mineria 6, 1: 26–32. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.bo/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2519-53522021000100003&lng=es&tlng=es.

- Iervolino, S. A., and M. C. F. Pelicioni. 2001. A utilização do grupo focal como metodologia qualitativa na promoção da saúde. Revista Escola de Enfermagem da USP 35, 2: 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshnava, S. M., R. Rostami, R. M. Zin, D. Štreimikienė, A. Yousefpour, W. Strielkowski, and A. Mardani. 2019. Aligning the criteria of green economy (GE) and sustainable development goals (SDGs) to implement sustainable development. Sustainability 11, 17: 4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klettner, A., T. Clarke, and M. Boersma. 2014. The governance of corporate sustainability: Empirical insights into the development, leadership, and implementation of responsible business strategy. Journal of Business Ethics 122, 1: 145–165. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42921423. [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W., C. Shiel, A. Paço, M. Mifsud, L. V. Ávila, L. L. Brandli, and S. Caeiro. 2019. Sustainable Development Goals and sustainability teaching at universities: Falling behind or getting ahead of the pack? Journal of Cleaner Production 232, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, T. da S., and F. J. P. Abílio. 2022. A Educação Ambiental na formação inicial de professores/as: Contribuições da Pedagogia Crítica. Práxis Educativa 17, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, L. F., and M. P. D. Griebeler. 2022. Uma análise qualitativa sobre concepções da sustentabilidade ambiental. Revista Livre de Sustentabilidade e Empreendedorismo 7, 1: 117–139. Available online: http://www.relise.eco.br/index.php/relise/article/view/463.

- Nicolletti, M., G. Alem, P. Fillippi, L. F. Bismarchi, and M. Blazek. 2020. Atuação empresarial para sustentabilidade e resiliência no contexto da Covid-19. Rev. Adm. Empres. 60, 6: 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okanga, B., and D. Groenewald. 2017. Leveraging effects of triple bottom line business model on the building and construction small and medium-sized enterprises' market performance. Acta Commercii 17, 1: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M. V. X. de. 2021. O Direito ao Desenvolvimento e os Objetivos de Desenvolvimento Sustentável (ODS). O princípio da interdependência como parâmetro para a criação e manutenção das políticas públicas. Revista de la Secretaría del Tribunal Permanente de Revisión 9, 17: 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organização das Nações Unidas. 2015. Transformando Nosso Mundo: A Agenda 2030 para o Desenvolvimento Sustentável. Available online: https://nacoesunidas.org/pos2015/agenda2030/.

- Palma, L. C., and E. A. Pedrozo. 2019. Transformation for sustainability and its promoting elements in educational institutions: A case study in an institution focused on transformative learning. Revista Organizações & Sociedade 26, 89: 359–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M. T. 2021. The pedagogical practice of sustainability for transdisciplinarity in professional and technological education (PTE). Revista Brasileira de Educação 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2022. Programa das Nações Unidas para o Desenvolvimento - PNUD. Available online: https://www.br.undp.org/content/brazil/pt/home/about-us.html.

- Romão, B. J. P., D. D. Siqueira, R. P. de Barros Camara, and S. B. Paiva. 2023. Responsabilidade Social Corporativa e os Objetivos do Desenvolvimento Sustentável à Luz da Teoria da Legitimidade. ConTexto-Contabilidade em Texto 23, 54: 97–114. Available online: https://seer.ufrgs.br/index.php/ConTexto/article/view/130081.

- Roome, N., and C. Louche. 2016. Journeying toward business models for sustainability: A conceptual model found inside the black box of organisational transformation. Organization & Environment 29, 1: 11–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, F., and L. G. D. Faria. 2019. Business contribution to the Sustainable Development Agenda: Organizational factors related to early adoption of SDG reporting. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 26, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hernández, M. I., J. L. Vázquez-Burguete, M. P. García-Miguélez, and A. Lanero-Carrizo. 2021. Internal Corporate Social Responsibility for Sustainability. Sustainability 13, 7920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, I. 1993. Estratégias de transição para o século XXI. São Paulo: Nobel. [Google Scholar]

- Suriyankietkaew, S., and G. C. Avery. 2016. Sustainable Leadership Practices Driving Financial Performance: Empirical evidence from Thai SMEs. Sustainability 8, 4: 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuholske, C., A. E. Gaughan, A. Sorichetta, A. de Sherbinin, A. Bucherie, C. Hultquist, F. Stevens, A. Kruczkiewicz, C. Huyck, and G. Yetman. 2021. Implications for Tracking SDG Indicator Metrics with Gridded Population Data. Sustainability 13, 7329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Waal, J. W., T. Thijssens, and K. Maas. 2021. The innovative contribution of multinational enterprises to the Sustainable Development Goals. Journal of Cleaner Production 285, 125319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. 2015. Estudo de caso: planejamento e métodos. Porto Alegre: Bookman. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).