Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

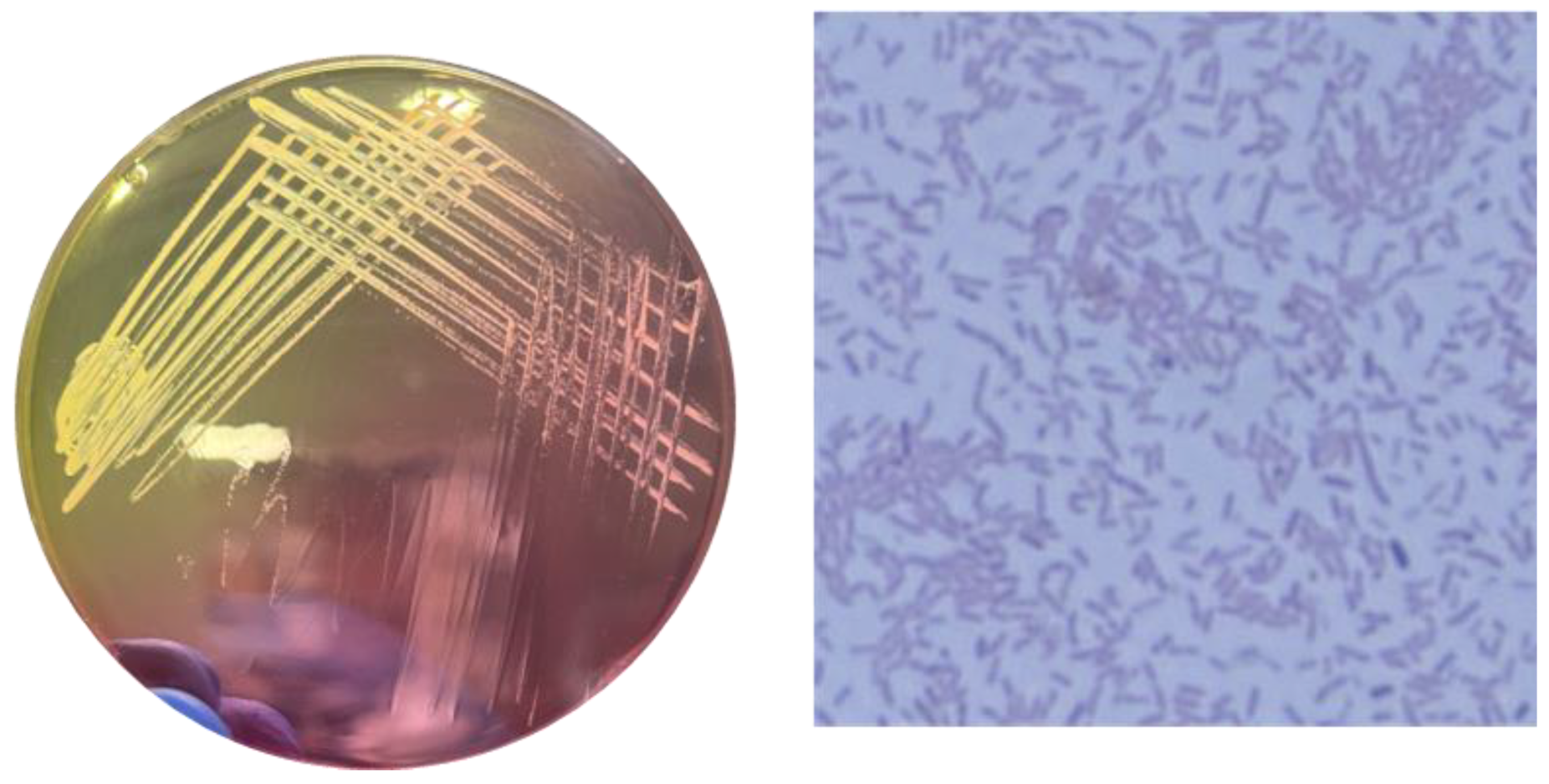

2.1. Morphological Analysis of Staphylococcus aureus

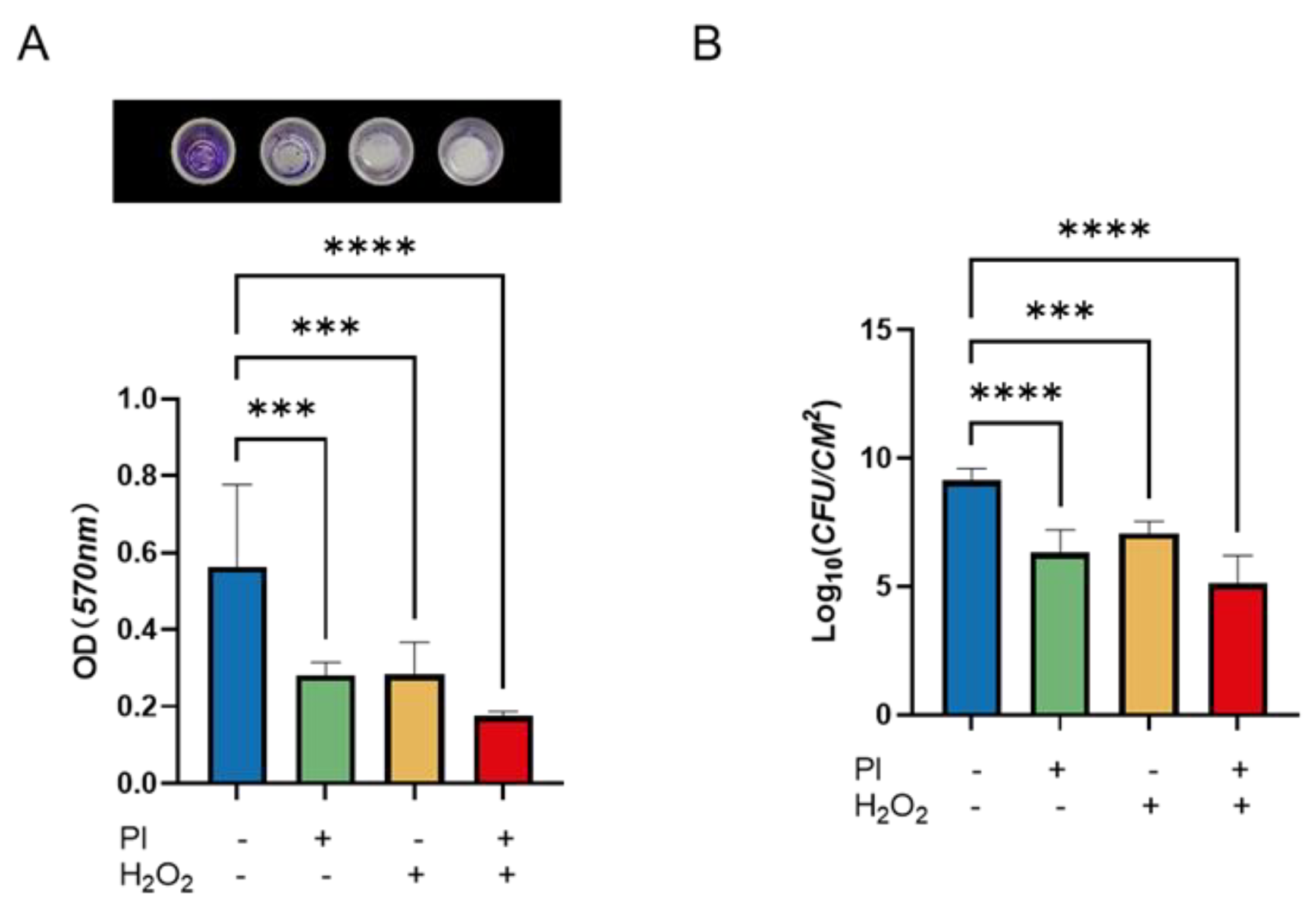

2.2. Evaluation of PVP-I and H2O2 Effectiveness on Biofilm Removal

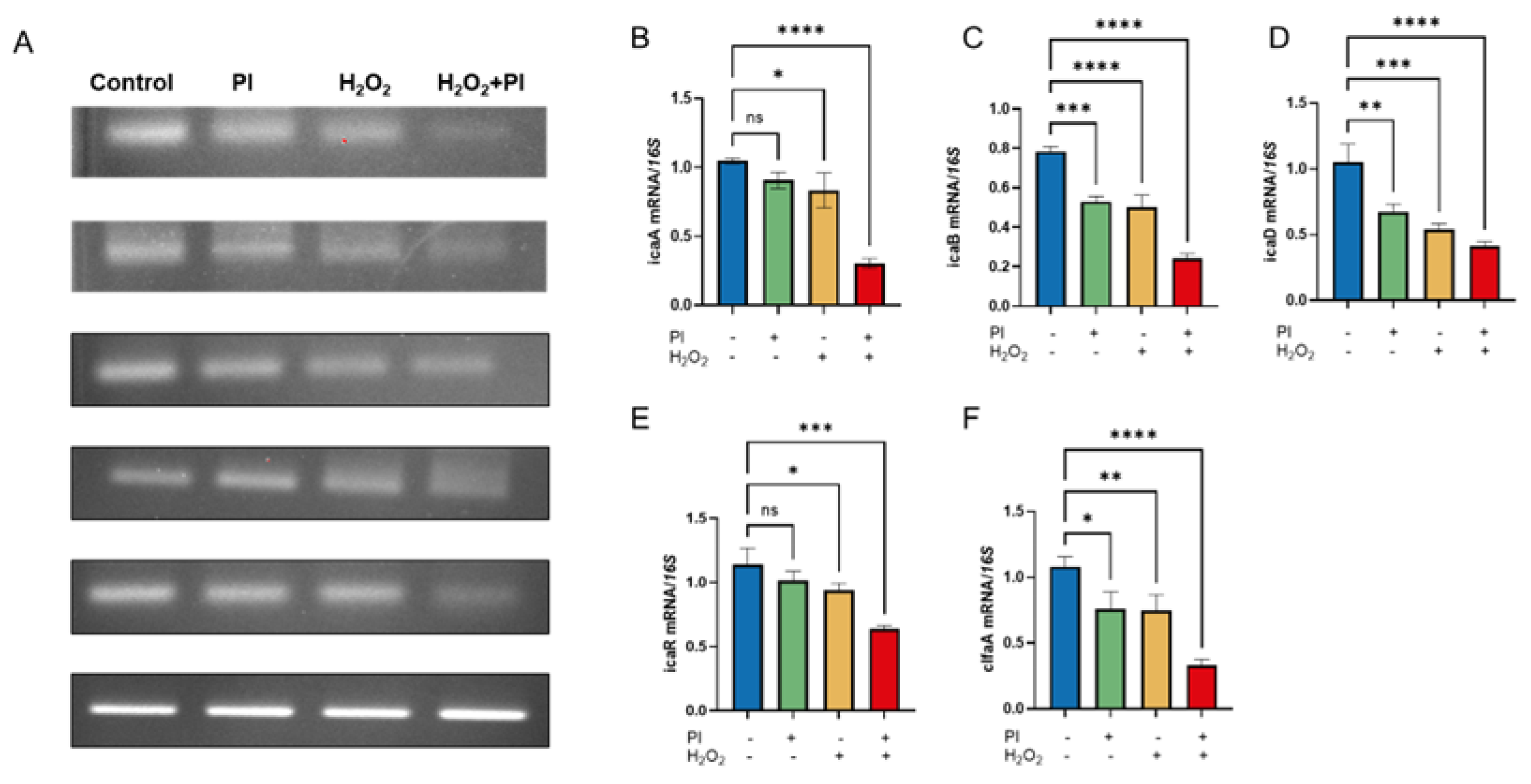

2.3. Expression of Biofilm-Associated Genes Under PVP-I and H2O2 Treatment

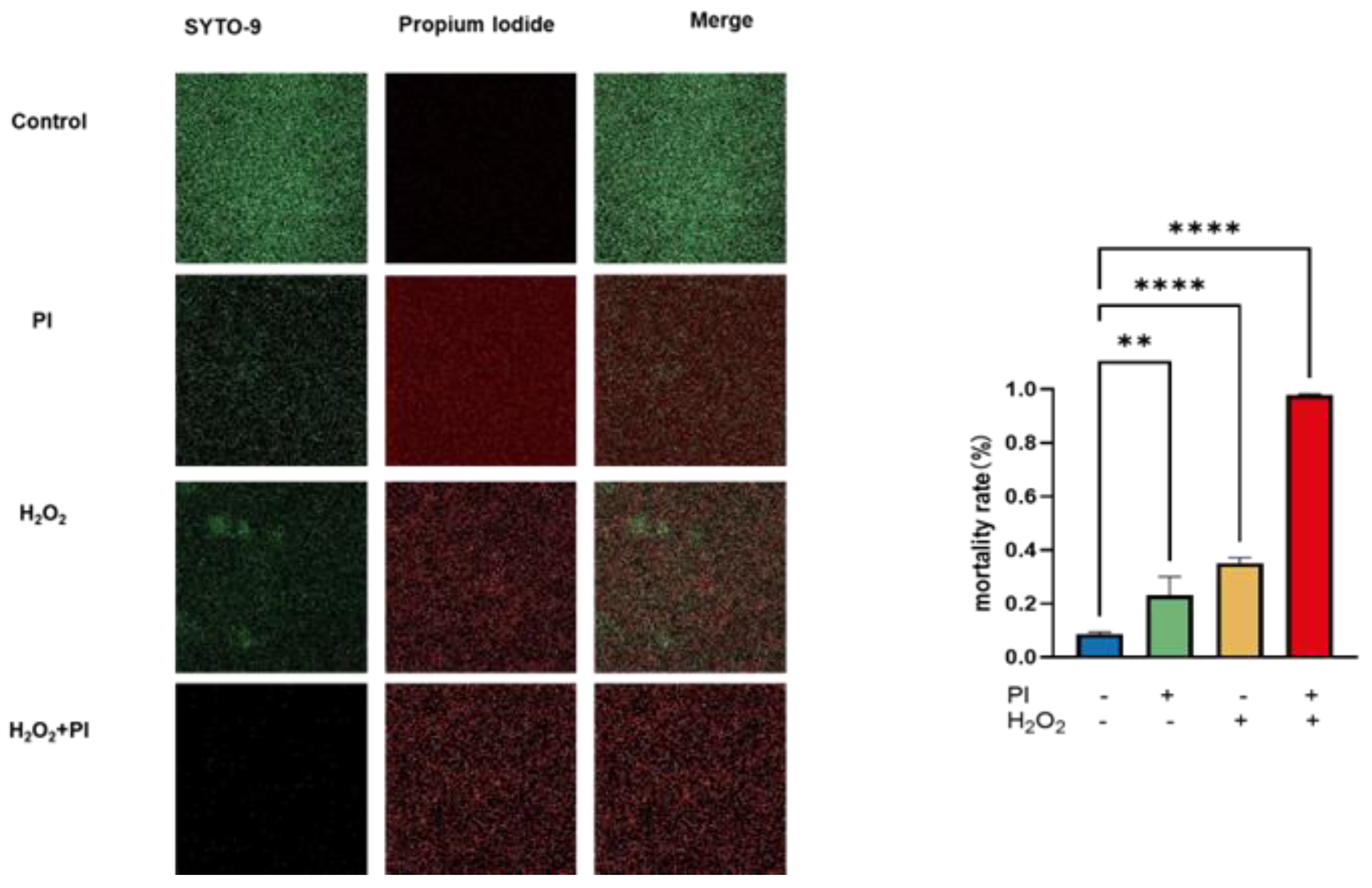

2.4. Live/Dead Assay of Biofilms Treated with PVP-I and H2O2

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strains

4.2. Biofilm Formation Assay

4.3. Treatment Procedures

4.4. Colony-Forming Unit (CFU) Enumeration

4.5. Biofilm Detection

4.6. Gene Expression Analysis (PCR)

4.7. Live/Dead Assay

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patel R. (2023). Periprosthetic Joint Infection. The New England journal of medicine, 388(3), 251–262. [CrossRef]

- Tande, A. J., & Patel, R. (2014). Prosthetic joint infection. Clinical microbiology reviews, 27(2), 302–345. [CrossRef]

- Gross, C. E., Della Valle, C. J., Rex, J. C., Traven, S. A., & Durante, E. C. (2021). Fungal Periprosthetic Joint Infection: A Review of Demographics and Management. The Journal of arthroplasty, 36(5), 1758–1764. [CrossRef]

- Pietrocola, G., Campoccia, D., Motta, C., Montanaro, L., Arciola, C. R., & Speziale, P. (2022). Colonization and Infection of Indwelling Medical Devices by Staphylococcus aureus with an Emphasis on Orthopedic Implants. International journal of molecular sciences, 23(11), 5958. [CrossRef]

- Kim, C. J., Kim, H. B., Oh, M. D., Kim, Y., Kim, A., Oh, S. H., Song, K. H., Kim, E., Cho, Y., Choi, Y., Park, J., Kim, B. N., Kim, N. J., Kim, K. H., Lee, E., Jun, J. B., Kim, Y., Kiem, S., Choi, H., Choo, E., … KIND Study group (Korea Infectious Diseases Study group) (2014). The burden of nosocomial staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection in South Korea: a prospective hospital-based nationwide study. BMC infectious diseases, 14, 590. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., Jiang, Y., Wang, W., Chen, J., & Zhu, J. (2023). The effect and mechanism of iodophors on the adhesion and virulence of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms attached to artificial joint materials. Journal of orthopaedic surgery and research, 18(1), 756. [CrossRef]

- Ruder, J. A., & Springer, B. D. (2017). Treatment of Periprosthetic Joint Infection Using Antimicrobials: Dilute Povidone-Iodine Lavage. Journal of bone and joint infection, 2(1), 10–14. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S., Singh, S. K., Chowdhury, I., & Singh, R. (2017). Understanding the Mechanism of Bacterial Biofilms Resistance to Antimicrobial Agents. The open microbiology journal, 11, 53–62. [CrossRef]

- Nadar, S., Khan, T., Patching, S. G., & Omri, A. (2022). Development of Antibiofilm Therapeutics Strategies to Overcome Antimicrobial Drug Resistance. Microorganisms, 10(2), 303. [CrossRef]

- Raval, Y. S., Mohamed, A., Song, J., Greenwood-Quaintance, K. E., Beyenal, H., & Patel, R. (2020). Hydrogen Peroxide-Generating Electrochemical Scaffold Activity against Trispecies Biofilms. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 64(4), e02332-19. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Gu, K., Wan, M., Gan, L., Chen, J., Zhao, W., Shi, H., & Li, J. (2023). Hydrogen peroxide enhanced photoinactivation of Candida albicans by a novel boron-dipyrromethene (BODIPY) derivative. Photochemical & photobiological sciences : Official journal of the European Photochemistry Association and the European Society for Photobiology, 22(7), 1695–1706. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Gu, K., Wan, M., Gan, L., Chen, J., Zhao, W., Shi, H., & Li, J. (2023). Hydrogen peroxide enhanced photoinactivation of Candida albicans by a novel boron-dipyrromethene (BODIPY) derivative. Photochemical & photobiological sciences : Official journal of the European Photochemistry Association and the European Society for Photobiology, 22(7), 1695–1706. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S. M., Lee, D. W., Park, H. J., Kwak, M. H., Park, J. M., & Choi, M. G. (2019). Hydrogen Peroxide Enhances the Antibacterial Effect of Methylene Blue-based Photodynamic Therapy on Biofilm-forming Bacteria. Photochemistry and photobiology, 95(3), 833–838. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S., Gupta, A., Upadhye, V., Singh, S. C., Sinha, R. P., & Häder, D. P. (2023). Therapeutic Strategies against Biofilm Infections. Life (Basel, Switzerland), 13(1), 172. [CrossRef]

- Shoji, M. M., & Chen, A. F. (2020). Biofilms in Periprosthetic Joint Infections: A Review of Diagnostic Modalities, Current Treatments, and Future Directions. The journal of knee surgery, 33(2), 119–131. [CrossRef]

- Wildemann, B., & Jandt, K. D. (2021). Infections @ Trauma/Orthopedic Implants: Recent Advances on Materials, Methods, and Microbes-A Mini-Review. Materials (Basel, Switzerland), 14(19), 5834. [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, F., Weber, C. D., Bell, A., Betsch, M., Maffulli, N., Poth, V., Hofmann, U. K., Hildebrand, F., & Driessen, A. (2023). Bacterial pathogens and in-hospital mortality in revision surgery for periprosthetic joint infection of the hip and knee: analysis of 346 patients. European journal of medical research, 28(1), 177. [CrossRef]

- Hoogenkamp, M. A., Mazurel, D., Deutekom-Mulder, E., & de Soet, J. J. (2023). The consistent application of hydrogen peroxide controls biofilm growth and removes Vermamoeba vermiformis from multi-kingdom in-vitro dental unit water biofilms. Biofilm, 5, 100132. [CrossRef]

- Ciofu, O., Moser, C., Jensen, P. Ø., & Høiby, N. (2022). Tolerance and resistance of microbial biofilms. Nature reviews. Microbiology, 20(10), 621–635. [CrossRef]

- Gryson, L., Meaume, S., Feldkaemper, I., & Favalli, F. (2023). Anti-biofilm Activity of Povidone-Iodine and Polyhexamethylene Biguanide: Evidence from In Vitro Tests. Current microbiology, 80(5), 161. [CrossRef]

- Taha, M., Arulanandam, R., Chen, A., Diallo, J. S., & Abdelbary, H. (2023). Combining povidone-iodine with vancomycin can be beneficial in reducing early biofilm formation of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-sensitive S. aureus on titanium surface. Journal of biomedical materials research. Part B, Applied biomaterials, 111(5), 1133–1141. [CrossRef]

- Lepelletier, D., Maillard, J. Y., Pozzetto, B., & Simon, A. (2020). Povidone Iodine: Properties, Mechanisms of Action, and Role in Infection Control and Staphylococcus aureus Decolonization. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 64(9), e00682-20. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. W., Carnicelli, J., Getya, D., Gitsov, I., Phillips, K. S., & Ren, D. (2021). Biofilm Removal by Reversible Shape Recovery of the Substrate. ACS applied materials & interfaces, 13(15), 17174–17182. [CrossRef]

- Sindi, A., Chawn, M. V. B., Hernandez, M. E., Green, K., Islam, M. K., Locher, C., & Hammer, K. (2019). Anti-biofilm effects and characterisation of the hydrogen peroxide activity of a range of Western Australian honeys compared to Manuka and multifloral honeys. Scientific reports, 9(1), 17666. [CrossRef]

- Lineback, C. B., Nkemngong, C. A., Wu, S. T., Li, X., Teska, P. J., & Oliver, H. F. (2018). Hydrogen peroxide and sodium hypochlorite disinfectants are more effective against Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms than quaternary ammonium compounds. Antimicrobial resistance and infection control, 7, 154. [CrossRef]

- Paulitsch-Fuchs, A. H., Bödendorfer, B., Wolrab, L., Eck, N., Dyer, N. P., & Lohberger, B. (2022). Effect of Cobalt-Chromium-Molybdenum Implant Surface Modifications on Biofilm Development of S. aureus and S. epidermidis. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology, 12, 837124. [CrossRef]

- Grossman, A. B., Burgin, D. J., & Rice, K. C. (2021). Quantification of Staphylococcus aureus Biofilm Formation by Crystal Violet and Confocal Microscopy. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.), 2341, 69–78. [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, K., Muhilvannan, S., & Arun Vignesh, M. (2022). Hesperidin inhibits biofilm formation, virulence and staphyloxanthin synthesis in methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus by targeting SarA and CrtM: an in vitro and in silico approach. World journal of microbiology & biotechnology, 38(3), 44. [CrossRef]

- Gajewska, J., & Chajęcka-Wierzchowska, W. (2020). Biofilm Formation Ability and Presence of Adhesion Genes among Coagulase-Negative and Coagulase-Positive Staphylococci Isolates from Raw Cow’s Milk. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland), 9(8), 654. [CrossRef]

- Oduwole, K. O., Glynn, A. A., Molony, D. C., Murray, D., Rowe, S., Holland, L. M., McCormack, D. J., & O’Gara, J. P. (2010). Anti-biofilm activity of sub-inhibitory povidone-iodine concentrations against Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of orthopaedic research : official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society, 28(9), 1252–1256. [CrossRef]

- Nourbakhsh, F., & Namvar, A. E. (2016). Detection of genes involved in biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus isolates. GMS hygiene and infection control, 11, Doc07. [CrossRef]

- Atshan, S. S., Shamsudin, M. N., Karunanidhi, A., van Belkum, A., Lung, L. T., Sekawi, Z., Nathan, J. J., Ling, K. H., Seng, J. S., Ali, A. M., Abduljaleel, S. A., & Hamat, R. A. (2013). Quantitative PCR analysis of genes expressed during biofilm development of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Infection, genetics and evolution : journal of molecular epidemiology and evolutionary genetics in infectious diseases, 18, 106–112. [CrossRef]

- Deivanayagam, C. C., Wann, E. R., Chen, W., Carson, M., Rajashankar, K. R., Höök, M., & Narayana, S. V. (2002). A novel variant of the immunoglobulin fold in surface adhesins of Staphylococcus aureus: crystal structure of the fibrinogen-binding MSCRAMM, clumping factor A. The EMBO journal, 21(24), 6660–6672. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).