1. Introduction

Orthopedic postoperative infections are complications that occur after surgical procedures involving bones, joints, or associated soft tissues. The microbial causative agents are often patient’s own microbiota or microbes that get to the surgical site by contaminated instruments or through the environment [

1]. Orthopedic infections and their treatment are particularly problematic when biomaterials like implants or prosthetics are involved, as they provide surfaces for microbial adhesion and biofilm formation. A significant portion of orthopedic infections are caused by skin-associated microbes entering the surgical site, such as

Staphylococcus epidermidis and

S. aureus (including methicilin-resistant

S. aureus, MRSA), both known for their biofilm-forming capabilities on orthopedic implants. Additionally,

Cutibacterium acnes and

Corynebacterium amycolatum, which are part of the patient's microbiota, can cause persistent infections (especially these localized in spine area) after surgery. Gram-negative

Pseudomonas aeruginosa or fungus

Candida albicans are less frequently implicated, nevertheless they also can be isolated as etiological factor of immunocompromised orthopedic patients or when biomaterials are involved [

2,

3,

4]. Orthopedic-related infections can lead to biofilm formation, implant failure, chronic complications, and the need for revision surgery, posing a significant threat to the therapeutic success. Despite advances in surgical techniques and perioperative care, the incidence of surgical site infections (SSIs) in orthopedic procedures remains a significant issue, with rates ranging from 0.5 to 2.5%, depending on the type of surgery and patient risk factors [

5].

Antibiotic prophylaxis remains one of the key strategies in preventing these infections, with standard guidelines recommending the administration of antibiotics within 60 minutes prior to incision to ensure optimal tissue concentrations during surgery. Commonly, first-generation cephalosporins such as cefazolin are employed to target pathogens like

S. aureus and

S. epidermidis [

6]. However, the growing emergence of antibiotic-resistant organisms, including methicillin-resistant MRSA and multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria, is increasingly limiting the efficacy of conventional prophylactic regimens. Moreover, the presence of implants and biomaterials’ non-organic surfaces provides an optimal environment for biofilm formation, which further complicates treatment by reducing antibiotic penetration into these microbial communities [

7,

8]. As a result, despite the use of systemic antibiotics, infections can persist, leading to implant failure and the need for revision surgery. These challenges highlight the urgent need for alternative strategies, such as localized antiseptic delivery systems and novel antimicrobial approaches, to improve infection control [

9].

Antiseptics are chemical agents designed to kill microorganisms on living tissues, particularly to fight or to prevent the spread of infection. They possess a direct, broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity, targeting bacteria, fungi and certain types of viruses [

10]. Antiseptic agents like povidone-iodine or polyhexanide are applied to treat chronic wound infections, while alcohol-based products are used to disinfect skin before surgical procedures. In contrast, lavage solutions, also referred to as lavaseptics, are primarily used to mechanically flush out debris, blood, and contaminants (including microbial biofilm) from wounds or cavities during procedures or treatment. While lavaseptics may or may not contain antimicrobial agents, their main function is to clean the area through mechanical means (with use of appropriate surfactant agents) rather than directly kill microorganisms [

11].

However, there is some overlap between these two types of agents, as antiseptics can be used in character of lavage solutions, providing both antimicrobial activity and mechanical cleansing in surgical settings, thanks to the surfactant added to their composition. Additionally, some lavaseptics are formulated with antimicrobial properties, blurring the distinction between antiseptics and lavaseptics. This mixed situation makes it essential to clearly define the intended use of each solution—whether for its antimicrobial effects, mechanical flushing, or a combination of both—depending on the surgical context.

The use of antiseptics and lavaseptics in managing chronic wounds is a well-established procedure, with antiseptics providing both antimicrobial protection and mechanical cleansing to promote healing [

11].

However, in orthopedic surgery, infection prevention and control present a more complex challenge. The balance between achieving effective antimicrobial activity and avoiding potential harm to the patient’s tissues and cells is critical. Antiseptics, while effective at reducing microbial load, also cause cytotoxicity, damaging healthy tissues and potentially impairing healing, particularly when used around delicate tissues, such as in bone and joint surgeries [

12]. This creates an ongoing debate about the optimal use of antiseptics in orthopedic surgery. One key question is how quickly antiseptics should be rinsed out after application, as residual antiseptic could continue to interact with tissue postoperatively, causing harm potentially. Lavage solutions without antimicrobial properties may be employed to flush out antiseptics, but the exact protocol for balancing efficacy against tissue safety remains a subject of ongoing research and clinical consideration in orthopedic procedures.

Therefore, the aim of the presented investigation is to provide additional data from in vitro studies on microbial biofilm, performed on surfaces relevant to orthopedic context (metals, their alloys, soft biological scaffolds) and treated with antiseptics containing polyhexanide, povidone-iodine, and hypochlorite, as well as lavaseptics (Ringer’s solution, saline). Understanding that the balance between antimicrobial efficacy and the potential harm to patient tissues is essential for improving outcomes we conducted also the parallel line of investigation and explored the effects of antiseptic and lavage agents displayed on both human cells in vitro and in vivo, on living model organism (Galleria mellonella larvae). In no way do we seek by means of this publication to provide conclusive results—these must be verified through further experimental and clinical studies. However, this is a critically important area of research, given the rising concerns over infection control and antibiotic resistance, especially in the context of implant-related surgeries. Therefore, our objective was to identify potentially promising directions for further research contributing to the ongoing discussion of antiseptic and lavaseptic use in prevention of infections related to orthopedic surgeries.

2. Results

In the first line of investigation, the routine MIC and MBEC assessment in 96-well plates and 24 – hour exposure time was performed towards analyzed products and microorganisms (n=25 for each species). The results, presented in the form of median MIC and MBEC are shown in

Table 1. The Gram-positive cocci (

S. epidermidis and

S. aureus) were the most sensitive to PHMB and LS; both these products contain polyhexanide as active substance, but with different concentrations (PHMB contains 2.5 times more polyhexanide than LS). The cocci were not sensitive to low-concentrated hypochlorite in the applied range of concentrations (with the highest concentration of 50%). Not surprisingly, the cocci (and other tested microorganisms), were also not sensitive to the liquids that do not contain antimicrobial components (R, NaCl).

The Gram-negative P. aeruginosa displayed higher tolerance to PHMB than Gram-positive cocci, with median MIC and MBEC equal of 3,13% and 25%, respectively. The MBEC values of C. acnes and C. amycolatum were also higher than these recorded in cocci, still yet within range of concentrations applied. The iodine-containing product (B) also displayed activity towards planktonic and biofilm-forming cells in microtitrate plate setting, nevertheless the MIC/MBEC values recorded were higher (less favorable) than it was observed for PHMB-containing liquids. In any case the values of MBEC were lower than the value of MIC; the highest difference between these two values (32 times) was observed for C. acnes.

In the next experimental setting, referred to as the Biofilm Oriented Antiseptic Test (B.O.A.T.), shorter (and more clinically relevant) exposures to antiseptic/lavaseptic liquids were applied (

Table 2). Moreover, the B.O.A.T. test allows also to measure an activity of working solution (undiluted product, i.e. 100%), in contrast to the routine microtitrate plate model (

Table 1), where a maximum of 50% of solutions can be tested. The data provided by this version of B.O.A.T. is of a qualitative nature, i.e. it indicates if complete eradication of biofilm of specific strain after exposure to specific liquid occurred or not (yes/no type of result).

As shown in

Table 2, liquids that do not contain antimicrobial components (NaCl, R) did not display any antibiofilm activity in B.O.A.T. test, similarly to the low-concentrated hypochlorite product (G) and lower-concentrated polyhexanide product (LS). PHMB and B liquids did not manifest antibiofilm activity towards all

S. epidermidis,

S. aureus and

C. acnes strains in the shortest time applied of 30’. Overall, the B product acted more efficiently in the 30’ of exposure time and eradicated completely biofilm formed by 60% of

C. amycolatum strains, while any of

C. amycolatum biofilm-forming strains was completely eradicated by PHMB liquid. In 1h exposure, the PHMB liquid was more effective towards

C. albicans than B liquid, in turn both PHMB and B antiseptics were equally effective against

P. aeruginosa biofilms.

The data presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2 were obtained using static conditions for biofilm development, where polistyrene bottom of 96-well plate served as the surface of biofilm growth. In the subsequent line of investigation, the porous, elastic and mesh-like polymeric surface made of bacterial cellulose was applied to mimic the soft tissue surface.

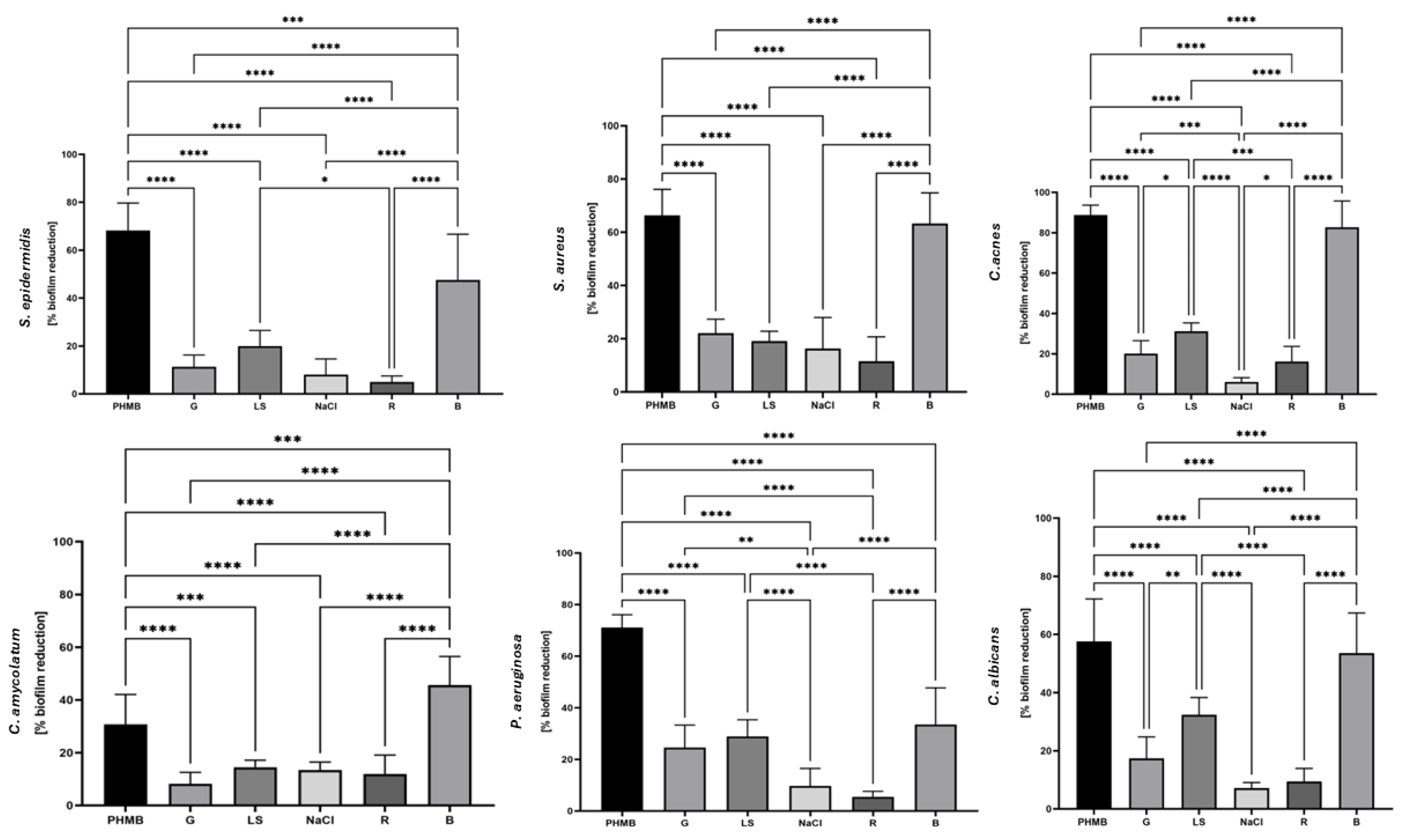

The data presented in

Figure 1 indicate that G, LS, NaCl and R products displayed low (~ 20%) ability to eradicate pathogenic biofilm, regardless of species they were applied against. The NaCl and R products contain no antimicrobial compounds, therefore observed drop in biofilm biomass was likely caused by subsequent rinsing procedures performed within test protocol, i.e. by mechanical disruptive force. Similar levels of eradication were observed when G and LS products were applied. The average level of biofilm reduction, regardless of the species applied were ~ 65% and~ 50% for PHMB or iodine-containing B product, respectively. All differences between reduction caused by PHMB and B were statistically significant (p<0.0001). The data presented in

Figure 1 are cohesive with these from

Table 1 and

Table 2 with this regard that PHMB and B product displayed significantly higher antibiofilm activity than G and LS and – unsurprisingly – than NaCl and R. In turn, results obtained by means of Bacterial Cellulose Model indicate that PHMB acted significantly stronger (p<0.0001) than B Liquid against pathogenic biofilms of

S. epidermidis,

S. aureus,

C. acnes,

C. amycolatum,

P. aeruginosa, but not

C. albicans, in contrast to results obtained by means of B.O.A.T. test (

Table 2) where B liquid performed overall better than PHMB.

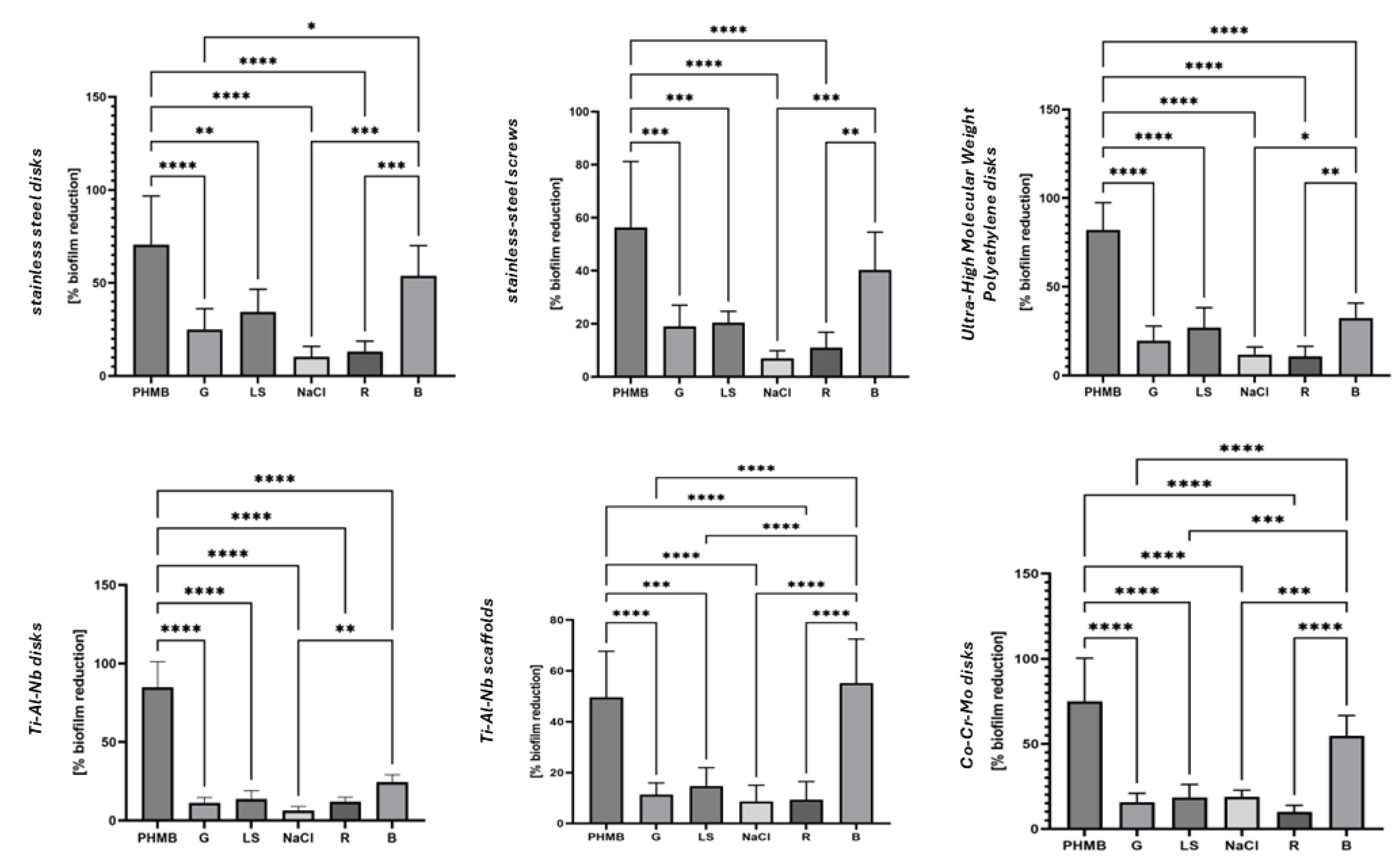

In the fourth experimental model, biofilms grown on abiotic surfaces commonly used in orthopedic implants were rinsed for a clinically relevant duration of 5 minutes. The data presented in

Figure 2 indicates that the application of rinsing force translates, to some extent, into biofilm removal even when liquids devoid of antimicrobial component (R, NaCl) are applied. Interestingly, in case of liquids containing low concentrations of antimicrobials (G, LS) the level of eradication was higher than the one observed for R, NaCl when stainless steel, UHMWP, Ti-Al-Nb disks (but not Ti-Al-Nb scaffolds) were used as surface for biofilm growth, contrary to the results obtained in Bacterial Cellulose Model (

Figure 1), where all these products displayed similar level of activity. Nevertheless, the level of biofilm eradication did not exceed 35% and 25% when LS or G were applied, respectively.

Another important observation was that the more complex was the surface (mesh, screws), the lower the eradication was observed, compared to the smooth surfaces of disks. Out of the two antiseptics (PHMB and B), recognized as the most effective in the earlier-presented datasets (

Table 1 and 2,

Figure 1), the PHMB manifested significantly higher antibiofilm activity (p<0.0001) when stainless steel disks and screws, UHMW polyethylene disks, Ti-Al-Nb disks and Co-Cr-Mo disks but not Ti-Al-Nb scaffolds served as the surface for biofilm growth.

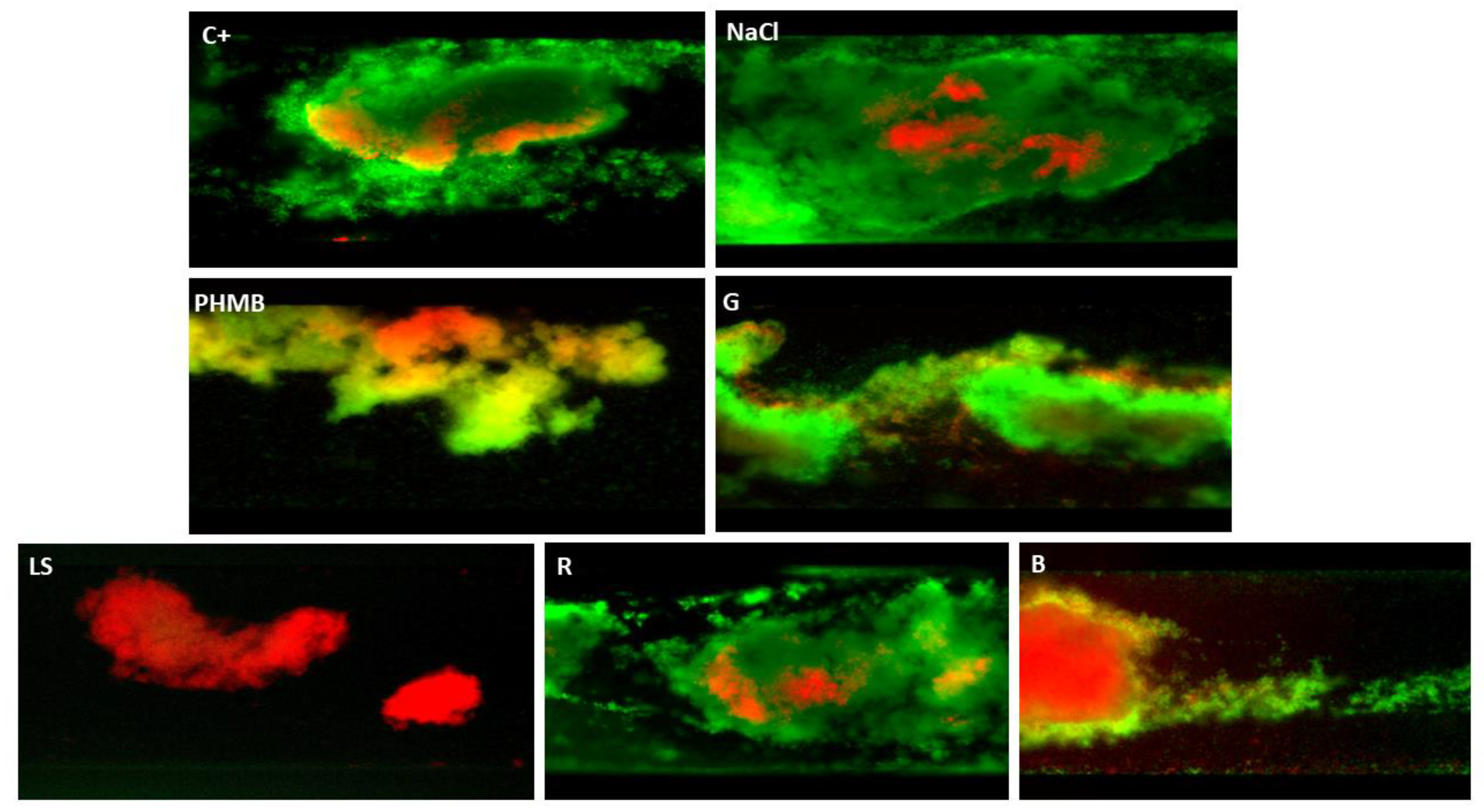

The next investigation also covered the flow conditions, however this time it was performed for biofilm formed by Gram-positive

S. aureus only (

Figure 3). This experimental line included strictly controlled microfluidic conditions and fluorescent microscopic technique in which live (intact), and dead (damaged) biofilm-forming cells are distinguished, by green or red/orange color, respectively.

Obtained results indicate no visible differences, understood as live/dead cells ratio and overall amount of biofilm biomass, after treatment with water, or NaCl, or R solution. Interestingly, low-concentrated hypochlorite (G liquid) applied in these microfluidic conditions, was able to visibly diminish the area covered with biofilm. Nevertheless, this reduction was weaker compared to the biofilms exposed to PHMB, LS and B. Regarding these three liquids, it occurred that LS, although containing a lower concentration of polyhexanide than PHMB, exhibited higher ability to remove the biofilm than the later mentioned antiseptic. In turn, the B antiseptic, although able to efficiently kill the bacteria, at the same time was unable to efficiently push biofilm out of the microcapillaries. This phenomenon was seen as clogged bulk of dead (red-dyed) cells in the capillaries (

Figure 3,

picture “B”).

This relatively higher efficacy of LS than PHMB in micro-capillary conditions may be partially translated by the performed measurements of wettability, where LS exhibited different properties than other liquids applied (Supplementary Material 1). It was found that for hydrophobic surfaces (PLLA with water contact angle of ~85°, PLLA-HAP with water contact angle of 80° and PMMA with water contact angle of ~65°), PHMB, B, G and LS moistened the surfaces better compared to water and the greatest reduction of water contact angle (30°) was observed for LS, for all the polymer-based substrates.

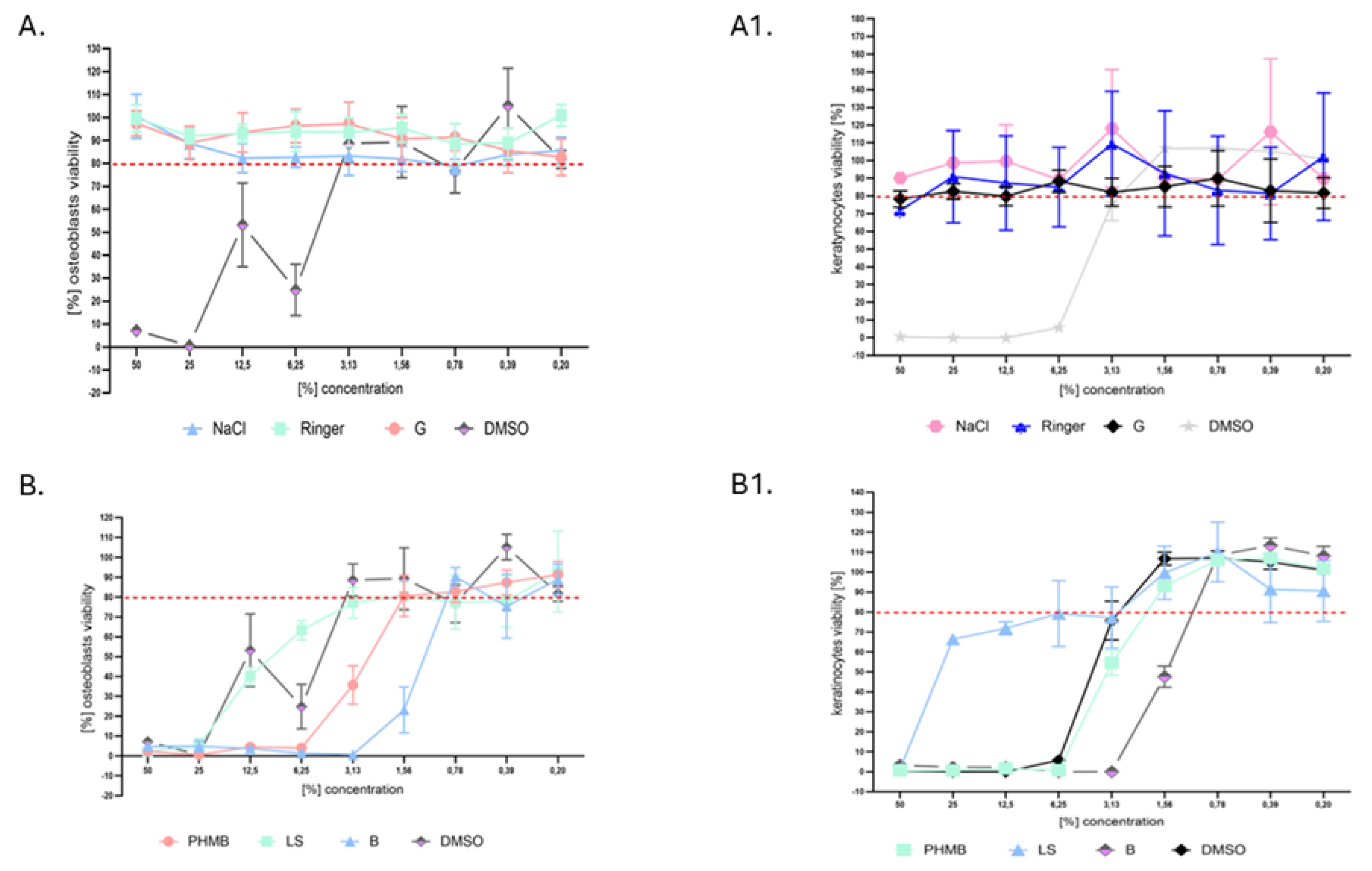

Because in orthopedic surgery, the balance between achieving effective antimicrobial activity and avoiding potential harm to the patient’s tissues and cells is critical for success treatment, in the next analysis, the cytotoxicity of investigated liquids towards osteoblasts and keratinocytes

in vitro was performed (

Figure 4).

It can be observed that not only NaCl and R solutions, that do not contain antimicrobial components, but also G liquid containing low-concentrated hypochlorite did not display significant cytotoxicity (more than 80% of cells survived exposure) towards keratinocytes and osteoblasts. The observed standard deviations of c.a. 10% from average values were result of applied methodology that includes series of rinsings and might result in random removal of cellular clusters. Regardless of the cell line tested, the same concentrations of PHMB displayed higher levels of cytotoxicity than LS; in turn both these liquids displayed lower levels of cytotoxicity in the same concentration applied than iodine-containing B antiseptic. The later mentioned liquid stopped to be cytotoxic towards both osteoblasts and keratinocytes when it was diluted 128 times, while PHMB antiseptic displayed non-cytotoxicity towards osteoblasts and keratinocytes when it was diluted 32- and 64 times, respectively. In turn, LS reached non-cytotoxic level towards osteoblasts and keratinocytes, when it was diluted 16 and 32 times, respectively (

Figure 4).

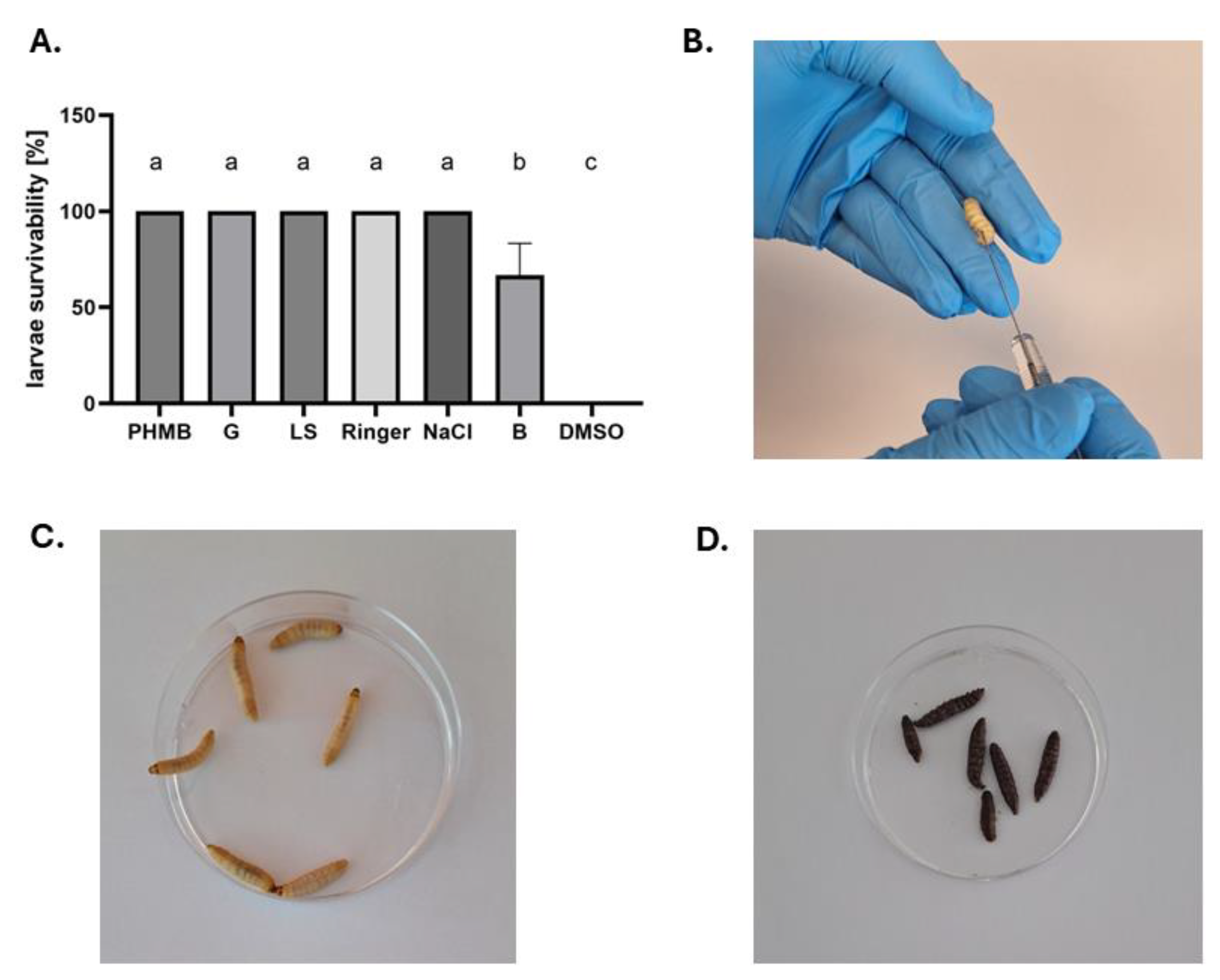

Normative cytotoxicity assays, as the one presented above, do not reflect the complexity of interactions occurring within tissues. Therefore, in the final investigation line, the cytotoxicity of tested antiseptics and lavaseptics was measured in live model organism, namely larvae of

G. mellonella (

Figure 5).

The data obtained in the

in vivo larvae model indicate that injection of liquids of weight equal 10% of larva’s body mass contributed to the significant morbidity only in case of iodine-containing B antiseptic. Any larva died, within 5-days period of observation after application of PHMB or LS liquids, contrary to the data shown in

Figure 4.

3. Discussion

The rationale behind this publication stems from the urgent clinical need to provide new data on the potential use of antiseptics and lavaseptics in perioperative and postoperative care in orthopedic surgery. Infections caused by the patient's own microbiota or microorganisms from contaminated instruments and/or introduced biomaterials can lead to the need for re-surgery and further complications, which not only significantly deteriorate the patient's health but also place a considerable burden on healthcare systems [

13,

14]. In this study, we tested locally applied solutions containing (PHMB, LS, G, B) or not containing (R, NaCl) antimicrobial components. All these liquids are successfully used in the treatment of chronic wounds. Their beneficial effects rely either solely on mechanical rinsing (R, NaCl) or on a combination of mechanical rinsing and antimicrobial activity (PHMB, LS, and B). In the case of G, which contains low concentrations of hypochlorite, its antimicrobial efficacy remains controversial, as was previously shown [

15]. Also clinical data suggest that hypochlorite needs to be applied at concentrations several hundred times higher than those found in G if it is to be effective against microbial biofilms, as recently demonstrated by Fazli and Bjarnsholt [

16].

In this study, we primarily focused on the activity of the aforementioned liquids against biofilms that, in a clinical context, develop on orthopedic biomaterials and surrounding tissues over an extended period of time. However, we recognize that perioperatively, contaminating microorganisms might also form small, adhered clusters on these surfaces, rather than fully developed, multilayer biofilm structures [

17]. Despite this,

in vitro assessments targeting such small microbial populations may lead to false-positive results, suggesting that virtually every antiseptic or lavaseptic could effectively remove microorganisms and secure the surgical site. Therefore, we adopted the approach that if the tested liquids demonstrate activity against mature biofilms, they should exhibit significantly stronger effects against smaller microbial clusters.

Building on our previous experience [

15,

18,

19], we employed a variety of experimental models in this work, incorporating both static and flow conditions, different surfaces for biofilm growth (including both biotic and abiotic ones), and varying exposure times. Additionally, aware of the major concern regarding the potential cytotoxicity of topical antimicrobial liquids towards eukaryotic cells, we also investigated this aspect using both

in vitro and

in vivo models.

The first line of investigation covered standard microtitrate plate model for assessment of antimicrobial (understood here as “anti-planktonic” and expressed by MIC value) and antibiofilm (expressed in form of MBEC value) activity of analyzed antiseptics/lavaseptics [

Table 1]. This

in vitro model is associated with significant disadvantages regarding translation of obtained results to clinical practice [

20], due to inadequate time of exposure on antimicrobials (24 hours), application of diluted antimicrobials and flat polystyrene surfaces. Nevertheless, due to the widespread historical use of this approach, its performance might be considered a necessary first step.

NaCl and R, which contain no antimicrobial components, had no effect on the microorganisms analyzed, similar to G. This lack of effect was observed for both planktonic cells and biofilms of the tested microorganisms. For all microorganisms and liquids tested, the recorded MBEC values exceeded the MIC values by several to a dozen times, clearly demonstrating the well-recognized increased tolerance of biofilms to antimicrobials [

21]. As shown in

Table 1, PHMB, and even LS (which contains 2.5 times lower concentrations of polyhexanide than PHMB), could be diluted more than the iodine-containing B and still effectively kill the tested pathogens. On the other hand, the differences between the MIC and MBEC values for the B liquid were smaller (more favorable), ranging from 2 to 8 times, compared to PHMB, where the difference between these values ranged from 4 to 16 times.

The next test, dubbed B.O.A.T. (Biofilm Oriented Antiseptic Test) allows to apply undiluted liquids in the more relevant, clinically-oriented contact times [

Table 2]. As shown, along with the exposure of biofilms on tested liquids, the percentage of eradicated biofilm-forming strains increased as well. Contrary to the results presented in

Table 1, where the PHMB liquid displayed the highest activity, in the B.O.A.T. test, B liquid was able to eradicate completely biofilms formed by all pathogens in the longest (24h) time applied, and biofilm of

P. aeruginosa in 30’ contact time, what did not occur when PHMB was applied. This difference may be translated by the fact that iodine efficacy is highly concentration-dependent, as observed in our study. At low concentrations, iodine's activity is significantly reduced, which can be attributed to several factors. First, iodine displays a non-linear dose-response relationship, meaning that only at sufficiently high concentrations can enough free iodine molecules interact with microbial components to initiate rapid cell damage. This suggests that iodine needs to exceed a critical threshold to fully exert its antimicrobial effects [

22]. Second, iodine's "activity threshold” is essential for its effectiveness. At sub-threshold levels, there may not be enough reactive iodine species to disrupt microbial cell membranes, proteins, or nucleic acids, allowing the microorganisms to potentially repair any minor damage inflicted. Moreover, iodine is susceptible to inactivation in the presence of organic material, as it rapidly reacts with proteins, lipids, and other cellular components, reducing its bioavailability and antimicrobial potency over time. This explains why iodine's antimicrobial effect can diminish rapidly after its initial application, also in clinical settings where contact with organic matter is common [

23]. Finally, in the case of biofilms, microbial cells are further protected by the extracellular matrix, which limits iodine's penetration. While high concentrations of iodine can overcome these protective mechanisms, lower concentrations are often insufficient to breach the biofilm, allowing microorganisms to survive and persist.

The remaining liquids (G, LS, R, NaCl) did not display any measurable antimicrobial activity. However, it should be noted that in this study, due to the multitude of strains and tests applied, only the qualitative version of the B.O.A.T (indicating whether complete eradication occurred or not) was conducted. A quantitative version of the B.O.A.T. could provide a more nuanced data set, showing the percentage [%] of reduction compared to the untreated control group [

19].

After completing the assessment of polystyrene-based models, the soft, tissue-like surface of bacterial cellulose (BC) was used to culture microorganisms [

Figure 2]. The rationale was that BC would mimic the tissue surrounding bone or biomaterials. Its scaffold-like structure allows microorganisms to penetrate its interior, providing additional protection against antiseptics. Interestingly, in this model, PHMB showed significantly higher (p<0.0001) efficacy than B, despite the opposite outcome observed in the previous B.O.A.T. test. This discrepancy could be due to PHMB's ability to penetrate and interact more effectively with the scaffold structure of BC, reaching deeper-embedded microorganisms. In contrast, B, which relies on iodine, may be less effective due to the physical absorption in BC, which could trap iodine within the material, limiting its contact with microorganisms [

23]. The ease of iodine absorption is the reason why antiseptics based on this element are avoided in wound treatment for patients with thyroid conditions or premature infants [

24]. In turn, G, LS, R, and NaCl displayed significantly lower activity (p<0.0001) compared to PHMB and B, with their efficacy being comparable regardless of whether the liquid contained antimicrobial components or not. This low level of eradication can once again be attributed to the rinsing procedures used in this technique rather than to the antimicrobial or lavage properties of these liquids.

The data in

Figure 2 show the level of eradication achieved when biofilms grown on orthopedic-relevant biomaterials were exposed to the tested liquids for 5 minutes. These results are the outcome of at least two factors: the antimicrobial activity itself (understood as the ability to kill microorganisms) and the rinsing force generated by the applied surfactant, as all other conditions were kept constant. The outcomes obtained were fully consistent with those from the BC model, where PHMB exhibited significantly stronger activity than B, which in turn was significantly stronger than G, LS, R, and NaCl. LS displayed antimicrobial activity at a level similar to or slightly higher than G. Therefore, emphasis should be placed also on the third factor, namely the interplay between the antimicrobial agent and the surfactant. One may hypothesize that a fast-acting antimicrobial, such as PHMB or iodine [

25], may disrupt the biofilm structure by destroying cells, which facilitates the biofilm's detachment by the surfactant. On the other hand, the surfactant, by loosening the extracellular matrix structure, may enhance the accessibility of the biocidal component to the cells [

26].

The observed reduced efficacy of antiseptics in removing biofilms from orthopedic biomaterials (stainless steel screws, Ti-Al-Nb scaffolds), compared to the discs made from the same material, can be attributed to more complex surface topographies of the earlier mentioned. These surface irregularities provide additional protection for biofilms by creating niches where microorganisms can attach, proliferate, and form more resilient biofilm structures [

27]. In contrast, metal or alloy discs typically have smoother, less complex surfaces, allowing antiseptics to interact more directly with the biofilm. To provide translational insight, the increased surface area and the complexity of orthopedic biomaterials not only shield biofilms from direct contact with antiseptics but may also reduce the effectiveness of mechanical forces during rinsing, further limiting the removal of biofilms. This indicates that the structural properties of orthopedic biomaterials play a crucial role in biofilm persistence and highlight the need for use of efficiently acting antiseptics in such applications.

At this moment, it is difficult for us to explain the results presented in

Figure 3, where LS exhibited visibly stronger activity against

S. aureus than PHMB, despite containing 2.5 times lower concentrations of polyhexanide. Some insight was provided by the wettability measurements where LS demonstrated the most extensive spreading compared to the other tested liquids. The low contact angle recorded for LS may translate into a high surface wetting ability, potentially contributing to greater removal efficiency, especially in such narrow cylindrical interiors as those in the micro-capillaries. In contrast, the bulk of red-dyed cells clogging the micro-capillary after exposure to the iodine-containing B product is most likely due to iodine’s mechanism of action, which involves rapid cell denaturation and dehydration. This process may cause the organic remnants of the cells to adhere to the micro-capillary. Overall, qualitative data from microfluidic model indicated higher efficacy of LS than PHMB and B; while these two later mentioned antiseptics acted more efficiently than G, R and NaCl.

In the initial investigation of eukaryotic cells presented in this work, a standard cytotoxicity test was conducted [

Figure 4]. This experimental setup shares several limitations with the microtiter plate assay on microorganisms described in

Figure 1, such as irrelevant exposure times and the use of flat, abiotic surfaces. Despite these drawbacks, this

in vitro cytotoxicity test remains commonly used; however, it is increasingly being replaced by more advanced assessments, such as those based on matrigel, which offer a more biologically relevant environment. Herein, we applied osteoblast cell lines due to orthopedic relevance and keratinocytes were also considered for cytotoxicity studies. Given that antimicrobial compounds may encounter both bone and surrounding soft tissues during surgery, assessing their effects on keratinocytes could offer a broader safety profile. This complements previous studies by Kramer and Severing [

28,

29], who investigated fibroblasts in this context, making keratinocytes a logical next step for evaluating potential impacts on skin tissue. The results suggest that antiseptics such as PHMB and iodine-containing antiseptic B, while effective against biofilms, display significant cytotoxicity at higher concentrations toward osteoblasts and keratinocytes

in vitro. In contrast, exposure to G, NaCl, and R did not reduce cell viability below 80%, which is considered a safe threshold. Notably, the concentrations of PHMB that were effective against planktonic bacteria were approximately 2-4 times higher than those that were non-cytotoxic to eukaryotic cells, with an even greater discrepancy observed for biofilm eradication. The iodine-containing antiseptic B exhibited even higher cytotoxicity than PHMB at antimicrobial concentrations [compare

Table 1 vs

Figure 4]. These findings underscore the importance of rinsing such antiseptics after clinical application to prevent cellular damage, although their strong biofilm-removal capacity could mitigate the risk of severe infectious complications.

The cytotoxicity test conducted

in vitro does not provide the cells with protection from the extracellular matrix or other factors present in living tissues. Therefore, in the final stage of our research, we injected antiseptics into

G. mellonella larvae [

Figure 5]. In the context of assessing the toxicity and effectiveness of antiseptics, this model is very useful because the larvae immune system exhibits certain similarities to the mammalian one, although it is much simpler [

30]. Additionally, the larvae allow for quick, cost-effective

in vivo studies, and their viability indicators, such as color changes or locomotor activity, can be easily monitored, providing valuable data on the potential effects of antiseptics. The results from the

in vivo larvae model revealed that injecting liquids amounting to 10% of the larva’s body mass caused significant morbidity only in the case of the iodine-containing antiseptic B, while no deaths were observed over a 5-day period following the application of PHMB or LS liquids. This contrasts with the

in vitro cytotoxicity data, where PHMB also appeared harmful to cells [

Figure 4]. The discrepancy can be attributed to the protective role of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and tissue-specific factors in living organisms, which are absent

in vitro conditions. ECM helps shield cells from harmful substances and modulates their interactions with antiseptics.

In vivo, PHMB’s toxicity may be mitigated by these natural defenses, resulting in less cellular damage. However, iodine-containing antiseptic B remains highly cytotoxic due to iodine’s strong oxidative properties, which can disrupt cellular components like proteins and lipids, overwhelming the ECM’s protective capacity. This explains why iodine-based antiseptic B showed significant toxicity in the larvae model, underscoring the importance of cautious clinical use, particularly the need to rinse iodine-based antiseptics to prevent damage to bone tissues, despite their strong antimicrobial effects.

This investigation explored a diverse range of experimental models to evaluate the effects of locally applied antiseptics and lavaseptics on biofilms and eukaryotic cells. One key finding presented in this manuscript is that low-concentration hypochlorite lacks significant antimicrobial activity (i.e., the ability to kill microorganisms) and should be classified as a lavaseptic by definition. Another important observation is that a solution containing 0.04% polyhexanide is less effective against biofilms (both antiseptically and lavaseptically) compared to a 0.1% polyhexanide solution (observed in 4 out of 5 experimental models). However, the 0.04% solution also exhibited lower cytotoxicity in vitro and similar cytotoxicity in vivo to its more concentrated counterpart. Notably, the 0.1% polyhexanide solution outperformed the iodine-containing antiseptic when tested on more complex biofilm surfaces, whereas the iodine-containing antiseptic was more effective in standard microdilution assays. Another translational outcome from our experiments is the observation that although in vivo tests showed that antiseptics may not be as cytotoxic as suggested by standard polystyrene-based assays, it is still recommended to rinse antiseptics off after their application on bone tissue or orthopedic materials. An open question remains regarding the optimal duration of exposure of bone and soft tissue to antiseptics and the appropriate amount of liquid required for effective rinsing.

Data from our study suggests that NaCl and Ringer's solution can be safely used for this purpose, though their application is insufficient to fully remove microorganisms from colonized surfaces.

In conclusion, this study highlights the complexity and significance of evaluating antiseptics and lavaseptics for clinical use, particularly in orthopedic surgery, where the prevention and treatment of biofilm-related infections are critical. Our findings underscore the need for a diversified experimental approach, incorporating both in vitro and in vivo models, to capture the multifaceted interactions between antimicrobial agents, biofilms, and host tissues. While in vitro tests remain essential for initial screening, they often fail to account for protective mechanisms, such as the extracellular matrix, which can mitigate cytotoxic effects. The discrepancies between our in vitro cytotoxicity results and those from the in vivo G. mellonella model further demonstrate the importance of this comprehensive approach. Key discoveries from this investigation include the identification of high concentrations of iodine-containing antiseptic B as cytotoxic, despite its strong antimicrobial action. Conversely, PHMB demonstrated lower toxicity and comparable biofilm-eradication efficacy, especially on complex surfaces. These insights suggest the need for careful consideration of antiseptic application protocols in clinical settings, including thorough rinsing to avoid tissue damage while maximizing biofilm removal.

One of the primary limitations of this study is the inherent discrepancy between in vitro and in vivo models, which may not fully replicate the complex interactions that occur in a clinical setting, particularly within human tissues. While in vitro experiments provide valuable initial insights into the antimicrobial and cytotoxic properties of antiseptics, they do not account for factors such as the extracellular matrix, immune responses, or blood flow, which can significantly influence the behavior of these agents in vivo. However, we attempted to mitigate this limitation by incorporating an in vivo model using G. mellonella larvae, which, while simpler than mammalian models, offers valuable translational data due to its similarities with the mammalian immune system.

Future research should focus on refining the use of these antiseptic agents, optimizing exposure times, and developing improved rinsing strategies. Moreover, the continued exploration of alternative models and surfaces will be crucial to better understand the real-world implications of antiseptic and lavaseptic use in surgical environments. This will guide the development of more effective infection control measures that balance antimicrobial potency with patient safety.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. The antiseptic and Lavaseptic Products Analyzed:

a) polyhexanide-containing product under brand name Preventia Surgical Irrigation Solution (Paul Hartmann AG, Heidenheim an der Brenz, Germany) containing according to manufacturer: polyhexanide (1.0g) and poloxamer, later referred to as the “PHMB”

b) hypochlorous acid / hypochlorite sodium – based product under brand name Granudacyn Wound Irrigation Solution (Molnycke, Goteburg, Sweden) containing according to manufacturer: water, sodium chloride, hypochlorous acid (0.05g), sodium hypochlorite (0.05g), later referred to as the “G”.

c) polyhexanide-based product under brand name LavaSorb, (B. Braun Medical AG, Melsungen, Germany) containing according to manufacturer: polyhexanide (0.40 g), macrogol 4000 (0.02 g), sodium chloride (8.60 g), calcium chloride dihydrate (0.33 g), potassium chloride (0.30 g), purified water up to 1 liter later referred to as the “LS”.

d) povidon-iodine-containing product under brand name Betasoidona (Hermes Artzneimittel, Pullach im Isartal, Germany), containing according to manufacturer povidone iodine (100 mg), equivalent to iodine (11 mg), excipients: glycerol, nonoxynol-9, disodium phosphate, citric acid, sodium hydroxide for pH adjustment, potassium iodate in 1 ml of solution, later referred to as the “B”.

e) 0.9% saline, (B. Braun Medical AG, Melsungen, Germany) later referred to as the “NaCl”.

f) Ringer solution, (B. Braun Medical AG, Melsungen, Germany), containing according to manufacturer: sodium chloride (8. 6g), potassium chloride (0. 3g) and calcium chloride dihydrate (0. 33g/L) in 1L of water for injections, later referred to as the “R”.

4.2. The organisms: The research was carried out on bacterial and fungal strains from Collection of The Department of Pharmaceutical Microbiology and Parasitology, Medical University of Wroclaw, Poland and reference strains from American Tissue and Cell Culture Collection ATCC (Manassas, Va, USA). The investigated group of microorganisms consisted of:

a) Staphylococcus epidermidis, (n=10), including ATCC strain number 12228

b) Staphylococcus aureus MRSA (n=10), including ATCC strain number 33591

c) Cutibacterium acnes (n=10), including ATCC strain number 11828

d) Corynebacterium amycolatum (n=10), including ATCC strain number 700207

e) Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n=10), including ATCC strain number 27853

f) Candida albicans (n=10), including ATCC strain number 10231

The clinical strains were isolated from chronic leg ulcers and long bone infections under approval of Bioethical Committee of Wroclaw Medical University, number 949/2022.

g) cellulose-forming Komagataeibacter xylinus number 53524

h) Galleria mellonella larvae, bred and cultivated in “P.U.M.A” Platform for Unique Model Application, were applied for the in vivo tests. The larvae applied in experiments were of 200±10mg weight.

4.3 The applied surfaces for biofilm development and subsequent removal, using provided antiseptic/lavaseptic products, were:

a) 16 mm diameter/2mm height disks made of medical grade polystyrene (Compamed, Dusseldorf, Germany) later referred to as the “PS”. This surface, non-applied in orthopedic setting but used commonly as a reference surface for biofilm growth in vitro [X] was applied in a character of control setting.

b) 16 mm diameter/2mm height stainless steel disks (Kamb, Warsaw, Poland), later referred to as the SSD.

c) 16 mm diameter/2mm height Co-Cr-Mo disks (Schutz Dental, Rosbach vor der Hoche, Germany), later referred to as the Co-Cr-Mo.

d) 16 mm diameter/2mm height Ti-Al-Nb disks (Kamb, Warsaw, Poland), later referred to as the Ti-Al-Nb-D.

e) 8mm diameter/8mm height Ti-Al-Nb (Kamb, Warsaw, Poland) scaffold implants, performed by Additive Manufacturing SLM processing as it was described in earlier work of ours [

31], later referred to as the Ti-Al-Nb-S.

f) 16 mm diameter/2mm height Ultra-High Molecular Weight Polyethylene disks (Enimat, Bydgoszcz, Poland), later referred to as the UHMPWE.

g) 6mmx1.8mm orthopedic stainless-steel screws, (Biomedent, Houston, TX, USA), later referred to as the SSC.

h) 16mm diameter/2mm height bacterial cellulose disks, later referred to as the

BC, obtained as we described earlier [

32]. Strain of

K. xylinus ATCC 53524 in Hestrin-Schramm medium (2% glucose (w/v; Chempur, Piekary Slaskie, Poland), 0.5% yeast extract (w/v; VWR Chemicals, Radnor, PA, USA), 0.5% bactopeptone (w/v; VWR Chemicals, Radnor, PA, USA), 0.115% citric acid (w/v; POCH, Gliwice, Poland), 0.27% Na2HPO4 (w/v; POCH, Gliwice, Poland), 0.05% MgSO4x7H2O (w/v; POCH, Gliwice, Poland), and 1% ethanol (v/v; Stanlab, Lublin Poland) was incubated for 7 days at 28°C in 24-well microtiter plates (F type, Nest Scientific Biotechnology, Wuxi, China). Next, formed BC disks were removed from the medium and cleansed using 0.1 M NaOH (Chempur, Piekary Slaskie, Poland) solution at 80°C until the BC became white. Then, the BC discs were purified using water until pH become 7 (measured by pH strips, Macherey–Nagel, Düren, Germany) and sterilized in a steam autoclave. BC discs were placed into 24-well plates (F type, Nest Scientific Biotechnology, Wuxi, China) in sterile water and incubated at 4°C until the time of further experiments.

4.4. Measurement of Minimum Biocidal Concentration (MBC) and Minimum Biofilm Eradication Concentration (MBEC) of antiseptics and lavaseptics using microtitrate plate model

a) MBC: Microbial suspensions at density 0.5 McF (McFarland turbidity scale) (Densitomat II, BioMerieux, Warsaw, Poland) in 0.9% NaCl (Stanlab, Lublin, Poland) were prepared from fresh, 24- hours cultures in appropriate culture broths (M-H for S. aureus, S. epidermidis, P. aeruginosa, C. albicans; BHI for C. acnes) All media were purchased from Graso, Jablowo, Poland. The suspensions were diluted 1000 times in appropriate media to reach ~ 105 cfu/mL and 100 μL of such suspensions were introduced into 10 wells of 96-well plate (VWR, Radnor, PA, USA). Next, serial dilutions of antiseptic/lavaseptic were added to each of well containing microbial suspension. Therefore, the highest v/v concentration of antimicrobial was 50%, while the lowest was 0,1%. The control setting bacterial/fungal growth (microbial suspension without antiseptic/lavaseptic), and sterility control (broth without suspended microbes) were provided in well number 12 and 11, respectively. The plates containing S. epidermidis, S. aureus, C. amycolatum, P. aeruginosa, C. albicans was incubated for 24 hours at 37°C under stationary conditions in aerobic conditions, while C. acnes was incubated for 24 hours/37°C in anaerobic conditions provided by anaerobic atmosphere generation container (Sigma-Aldritch, Taufkirchen, Germany). The analyses on C. acnes were performed with use of anaerobic chamber (Jacomex, Dagneux, France). The next day, the standard resazurin sodium salt solution (Acros Organics, Geel, Belgium) was applied to indicate the concentration of product, which caused stop of metabolic activity. The wells from parallel prepared plates with no resazurin solution were introduced to the 9800 µL of appropriate medium and incubated for 72h. If no turbidity change occur, the specific concentration of antiseptic/lavaseptic used was considered MBC.

b) MBEC: Microbial suspensions at density 0.5 McF (McFarland turbidity scale) (Densitomat II, BioMerieux, Warsaw, Poland) in 0.9% NaCl (Stanlab, Lublin, Poland) were prepared from fresh, 24- hours cultures in appropriate culture broths (M-H for S. aureus, S. epidermidis, P. aeruginosa, C. albicans; BHI for C. acnes) All media were purchased from Graso, Jablowo, Poland. The suspensions were diluted 1000 times in appropriate media to reach ~ 105 cfu/mL and 100 μL of such suspensions were introduced into 10 wells of 96-well plate (VWR, Radnor, PA, USA). Next, the plates were incubated for 24 hours (S. aureus, S. epidermidis, P. aeruginosa, C. albicans) or 48h (C. acnes) in the conditions as specified in MBC assessment. After incubation, and medium removal, serial dilutions of antiseptic/lavaseptics were added and plates were subjected to another 24 hrs. of incubation. Next, the medium was removed, the neutralizing agents were applied for 5 minutes, and after that the procedures related with resazurin staining and transfer to fresh media were performed as described in protocol for MBC assessment.

4.5. Measurement of activity of antiseptics/lavaseptics against biofilms using B.O.A.T. (Biofilm Oriented Antiseptic Test). The method was performed according to our earlier published work [

19]. The biofilm was established as described in point 4.4. of Material and Methods (MBEC). Next, the media were removed and 100 μL of the antiseptic/lavaseptic was added to the well with adhered biofilms. The contact time was 30’, 1h and 24h, while the incubation temperature was 37 ◦C. After exposure, the antiseptic/lavaseptic was gently removed and 100 μL of the appropriate neutralizer was introduced for 5 min at room temperature. Then, the neutralizers were removed and 100 μL of appropriate medium was added. The plates with pre-established biofilms of

S. aureus,

S. epidermidis,

P. aeruginosa,

C. albicans were incubated for 24h/37°C, while biofilm of

C. acne for 48 hrs. The survival/ eradication of biofilm was confirmed by change of turbidity, measurement of metabolic activity using tetrazolium salt assay [X] or spot-method [X]. The BOAT test was performed in 6 repeats.

4.6. The antiseptics/lavaseptic towards biofilm formed on Bacterial Cellulose Carrier was performed according to the earlier published work of our [

19]. BC carriers of 18 mm diameter were soaked in MH (BHI broth; Biomaxima, Lublin, Poland) medium overnight at 4 C. Next day, BC carriers were transferred to 24-well plates (VWR, Radnor, PA, USA). The 0.5 McF suspension of microorganisms, diluted 1000 times, was prepared in BHI medium. 1 mL of such suspension was added to each BC carrier and subjected to stationary incubation for 48 h at 37°C. Next, the suspension was removed, and the BC carriers were transferred to fresh 24-well plates. A 1 mL of undiluted antiseptic/lavaseptic agent was added to the BC containing microbial biofilm and left for 30 min at room temperature. Next, antiseptic/lavaseptic products were removed and 1 mL of neutralizer was added to each well for 5 min. Next, neutralizers were removed and 1mL of 0.1% saponine was added. The whole setting was subjected to intense vortex shaking for 1 minute. After that, the obtained suspension was subjected to the quantitative culturing on appropriate agar plates. This analysis was performed in 6 repeats. The number of cells from biofilm exposed to the presence of water, instead of antiseptic/lavaseptic products, was considered 100% of potential cellular growth in this setting.

4.7. The ability of antiseptic/lavaseptic products to flush biofilm out of orthopedic surfaces enlisted in point 4.3a-g was performed as shown in earlier work of ours [

33]. Flow conditions provided by digital peristaltic pump Ismatec Reglo (Randor, PE, USA) were used to enable microbial adhesion of 10

5 cells/mL on orthopedic surfaces for 1h, next the biofilm developed for 48h in static conditions. Next, the antiseptic/lavaseptic agents were introduced into a boxes containing the orthopedic surfaces for the applied contact time of 5’ and pace 1 mL/min. After that, the neutralizer was introduced in stationary conditions for 5’. The surfaces were introduced to the 5 mL of 0.1% saponine and subjected to the quantitative culturing on appropriate agar media. The number of cells from biofilm exposed to the presence of water, instead of antiseptic/lavaseptic products, was considered 100% of potential cellular growth in this setting. This analysis was performed in 6 repeats.

4.8. The ability of antiseptic/lavaseptic products to flush biofilm out measured by means of microfluidic system. This analysis was performed towards

C. albicans,

P. aeruginosa,

S. aureus biofilm using microfluidic BioFlux® (Fluxion, San Francisco, CA, USA) model in analogical way to the protocol presented in earlier work of ours [

18]. The microfluidic channels were flushed from inlets to outlets with TSB medium with a speed of 10 dyne/cm2 for 10 sec. Next, 0.1 mL of microbial solutions in TSB medium (OD600 = 1.0) was put into each of the outlet wells. The flow of microbe-containing solutions was turned on towards outlet to inlet wells with 5 dyne/cm2 for 5 sec. The solutions were left for 1 h of incubation in 37 °C to enable adhesion to the microcapillaries’ surface. Subsequently, 0.9 mL of TSB medium was introduced to the inlet wells, and the medium flow was turned on from inlet to outlet wells with an intensity of 0.5 dyne/cm

2/24h/37 °C. After culturing, both the inlet and outlet wells were drained. A 0.5 mL of solution being a one of the tested products with TSB medium in a 1:1 ratio was then added to the inlet wells and directed for a medium flow with a rate of 1.5 dyne/cm

2. TSB medium was used in control setting. Subsequently, inlet wells were again emptied and filled with 0.1 mL of a saline solution with 0.3 μL of SYTO9 and 0.3 μL propidium iodide (Filmtracer™ LIVE/DEAD™ Biofilm Viability Kit; ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for

S. aureus,

P. aeruginosa, and

C. albicans. These solutions were passed through microcapillaries for 1 h in the outlet direction. Photographs of microbial biofilms were taken with an inverted Carl Zeiss microscope (GmbH, Jena, Germany). The degree of biofilm development interpreted based on the microcapillaries’ coverage and the ratios of green/red fluorescence constituting information about the viability of biofilms were calculated using the ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, WA, USA).

4.9. The Wettability Measurement

In the study several synthetic materials were used, with different wettability including: microscope slide (glass), PLLA plate (Resomer L210s, Evonik, Germany) processed by injection molding (Boy XS, injection pressure 180bar, 200°C), PLLA/hydroxyapatite (30wt.% of the hydroxyapatite in the system) composite (Boy XS, injection pressure 200bar, 200°C), PMMA plate (Altuglas V920). Water contact angle (WCA) measurements were carried out using the PGX pocket goniometer (Fibro system AB, Sweden). For each material, at least 10 measurements were carried out at room temperature. As a reference, deionized water (water conductivity ~5-7 µS) was used.

4.10. The normative in vitro neutral red (NR) cytotoxicity assay towards keratinocytes and osteoblasts. The cytotoxicity test was performed towards ATCC 92022711 U2-OS osteoblasts and keratinocytes in the 96-well micro-well plate model according to the ISO 10993 standard: Biological evaluation of medical devices; Part 5: Tests for in vitro cytotoxicity; Part 12: Biological evaluation of medical devices, sample preparation, and reference materials (ISO 10993- 5:2009 and ISO/IEC 17025:2005) as we described in the earlier work of ours [

34]. The antiseptic/lavaseptic agents were introduced to the confluent cell cultures in the series of dilutions in such a manner that the highest concentration of antiseptic/lavaseptic was 50% (v/v) of working solution (undiluted product) and subjected to incubation for 24 h in 5 % CO2 at 37 ◦C. The 50% dimethylosulfate oxide (DMSO, ChemPur,Piekary Slaskie, Poland) served as control substance of known cytotoxic properties). Next, the medium was removed and 100 μL of Neutral Red (NR) solution (40 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) was introduced to the wells of the plate containing the cell lines. Subsequent incubation with NR lasted for 2 h at 37 ◦C. After this time, the NR was removed and the wells were rinsed with PBS (Phosphate Buffer Saline, Biowest) and left to dry at room temperature. 150 μL of de-stain solution containing of 50 % ethanol, 49 % deionized water, 1 % glacial acetic acid (v/v); POCH) was then introduced to each well of the plate, and vigorously shaken using microtiter plate shaker (Plate Shaker-Thermostat PST-60HL-4, Biosan) for 30 min until NR extraction. Next, the NR absorbance value was measured using a microplate spectrometric reader (Multi-scan GO, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a wavelength of 490 nm. The absorbance value of the cells not treated with the extracts was considered 100 % of possible cellular growth ( constituting positive control sample). The negative control constituted osteoblasts exposed to 50 % ethanol (POCH) for 3 min. These analyses were performed in 6 repeats.

4.12. Analysis of antiseptic /lavaseptic in vivo cytotoxicity towards G. mellonella larvae in vivo model. The larvae model was used to assess antiseptic/lavaseptic cytotoxicity in vivo. The larvae of the greater wax moth, G. mellonella, of average weight equal to 0.20±0.2 g, were selected for the experiment. The larvae were injected with 20 μL of undiluted antiseptic/lavaseptic products (constituting 10% of larvae mass) to evaluate its cytotoxicity. Exception was B antiseptic, where introduced volume was decreased to 10 μL, because the 20 μL led to the death of larvae within first 24 hours of experiment. Moreover, negative control with 20 μL of PBS (Biowest, Riverside, MO, USA) was used. The usability control was injection of 10 μL of 96% (v/v) ethanol (Stanlab, Lublin, Poland). The larvae were placed in 90 mm Petri dishes (Noex, Warsaw, Poland) and incubated at 30 ◦C/five days. Each day, the mortality of larvae was monitored. Death was defined when the larvae were nonmobile, melanized, and did not react to physical stimuli. Every antiseptic/lavaseptic product was tested in 10 larvae in two repeats giving 20 larvae/product.

4.13. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 10 (San Diego, CA, USA). Normality of distribution was verified using Shapiro–Wilk’s test. An Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was performed to assess statistical significance. For multiple comparisons, Tukey’s post hoc test was applied. A p-value threshold of less than 0.05 was set for significance in the ANOVA. For the Tukey post hoc analysis, significance levels were further categorized as p < 0.001 and p < 0.0001 for specific pairwise comparisons.